Abstract

Phencyclidine (PCP) is widely used as an animal model of schizophrenia. The aim of this study was to better understand the role of nitric oxide (NO) in the mechanism of action of PCP and to determine whether positive NO modulators may provide a new approach to the treatment of schizophrenia.

The effects of the NO donor, sodium nitroprusside (SNP), were studied in PCP-treated rats. Following drug administration, behavioural changes and the expression of c-fos, a metabolic marker of functional pathways in the brain, were simultaneously monitored.

Acute PCP (5 mg kg−1, i.p.) treatment induced a complex behavioural syndrome, consisting of hyperlocomotion, stereotyped behaviours and ataxia. Treatment with SNP (2–6 mg kg−1, i.p.) by itself produced no effect on any behaviour studied but completely abolished PCP-induced behaviour in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

PCP had differential regional effects on c-fos expression in rat brain, suggesting regionally different patterns of neuronal activity. The most prominent immunostaining was observed in the cortical regions. Pre-treatment with SNP blocked PCP-induced c-fos expression at doses similar to those that suppress PCP-induced behavioural effects.

These results implicate the NO system in the mechanism of action of PCP. The fact that SNP abolished effects of PCP suggests that drugs targeting the glutamate-NO system may represent a novel approach to the treatment of PCP-induced psychosis and schizophrenia.

Keywords: Phencyclidine, nitric oxide, sodium nitroprusside, locomotor activity, ataxia, neuronal activity, c-fos, rat

Introduction

Schizophrenia is one of the most serious human brain diseases, yet its aetiology and pathophysiology remain largely unknown. For the past 25 years it has been widely assumed that schizophrenia results from chronic dopamine hyperactivity (Seeman et al., 1976; Meltzer & Stahl, 1976). However, dopamine antagonists are relatively ineffective in alleviating some symptoms of schizophrenia, suggesting the involvement of other neuronal systems in the pathophysiology of this disease. In addition to their limited efficacy, currently available drugs often produce severe side effects, a major source of non-compliance. There is, therefore, a need for new drugs and approaches to the treatment of this severe psychiatric disorder. Phencyclidine (PCP) has been proposed to be one of the best pharmacological models of schizophrenia because it can mimic the full spectrum of schizophrenic disorders (Toru et al., 1994; Steinpreis, 1996; Thornbert & Saklad, 1996; Jentsch et al., 1997; Moghaddam & Adams, 1998). Thus, it was felt that investigating the central action of PCP might help us both to better understand the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and to explore the efficacy of new antipsychotic drugs. In this model, the ability of a compound to antagonise specific PCP behaviours in animals would be predictive of its antipsychotic properties in humans. The mechanism of action of PCP is very complex. Although PCP interacts with various neuronal systems that are strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (Toru et al., 1994; Steinpreis, 1996; Thornberg & Saklad, 1996), its most potent effects are on the glutamatergic system. PCP blocks the actions of glutamate at the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, giving support to the hypoglutamatergic theory of schizophrenia (Toru et al., 1994; Steinpreis, 1996; Thornberg & Saklad, 1996; Tamminga, 1998). Glutamate, acting through NMDA receptors, appears to be the principal activation signal for neuronal nitric oxide (NO) production (Ignarro & Murad, 1995; Szabo, 1996). PCP therefore might be expected to decrease neuronal NO levels; restoring NO levels might reverse this effect. Consistent with this idea, PCP has been shown to directly inhibit NO synthase (NOS) activity (Osawa & Davila, 1993; Chetty et al., 1995) and to have synergistic effects with the NOS inhibitor, L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (L-NAME) (Noda et al., 1995; Bujas-Bobanovic et al., 1998b). In the light of the data it seemed of interest to test the idea that PCP might be acting via nitric oxide. For this purpose, we studied the effects of the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) on PCP-induced behavioural changes and neuronal expression of the immediate-early gene product, c-fos.

Methods

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Quebec, Canada) weighing 250–300 g were used in this study. They arrived at the animal facilities at least 5 days prior to the start of the experiments. Rats were housed in groups of two on a 12/12 h light–dark cycle (lights on at 0700 h) at 22°C. Food and water were available ad libitum during the time the animals were in their home cages.

Experimental schedule

On experimental days the animals were removed from the home cage, weighed and placed individually in a transparent acrylic arena (43×34×28 cm). They were allowed to habituate to the arena for 1 h. During the light phase (0800–1400 h), rats were injected with saline or SNP (2, 4, 6 mg kg−1) 5 min before PCP (5 mg kg−1) or saline. To exclude a potential floor effect, rats were also tested under diffuse red light during their noctural period to favour high baseline levels of locomotion. The pilot study performed from 1900 h until 0700 h showed consistent baseline levels of locomotor activity (cm moved) from 2000 till 0100 h (7527±2453, 2000–2100 h; 9442±1967, 2100–2200 h; 9709±2229, 2200–2300 h; 9460±1004, 2300–2400 h; 7232±2048, 2400–0100 h) (n=5). During the dark phase (2000–0100 h) rats were injected with saline or SNP (6 mg kg−1) 5 min before PCP (5 mg kg−1) or saline. For both conditions, the observation period started immediately after the last injection. The observer was blind to the treatment given to each animal until the experiment was concluded. The dose of PCP was chosen according to dose-response studies performed previously in our laboratory and produces maximal behavioural response. Rats were randomly allocated to treatment groups and used only once. Four animals were tested at the same time.

Behavioural analysis

Behaviour was recorded for 1 h following drug administration by a video camera placed above the arenas and connected to a video recorder. Automated behavioural analysis was conducted in 10 min intervals using the EthoVision computer-based system developed by Noldus Information Technologies (Wageningen, The Netherlands). The arena was scanned three times per second by the program, and for each scanning the position of the rat was determined. These co-ordinates were subsequently related to actual distances in the arena by a calibration of the program to the dimensions of the arena. The analysis resulted in a track record for each rat that contained a complete record of the rat's movement pattern in the arena during the observation period. The track records were then analysed for the following parameters: DISTANCE MOVED: total distance moved (cm). Distance moved measured the locomotor activity of the rat during the observation period by summing up the distance, measured in a straight line, moved between consecutive samples for each rat. Velocity: distance moved (cm) per unit time (s). VELOCITY measured the hyperactivity of the rat during the observation period by calculating the average speed of animal movement excluding stop durations. ABSOLUTE ANGULAR VELOCITY: turning rate (degrees) per unit time (s). Absolute angular velocity measured the turning rate of the rat by calculating the change in direction of animal's movement between two samples per unit time. The absolute angular velocity ranges from 0–180 degrees and it does not quantify the tendency of animal to turn in a certain direction. An angle of 0 indicates that the animal has not deviated from the direction it was heading during the previous 1 s time interval, whereas a value of 180 indicates that the animal has turned in the opposite direction during the previous 1 s time interval. For ATAXIA assessment the animals were placed on a grate that consisted of parallel rods spaced 1.5 cm apart. The number of paw protrusions was recorded for 2 min as a measure of ataxia, 30 and 60 min after PCP or saline administration.

c-fos immunocytochemistry

At 1 h following PCP injection, rats were deeply anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (>70 mg kg−1) and perfused transcardially with 60 ml of 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by 120 ml of fixative (4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4). Brains were removed, postfixed for 48 h and cut sagittaly on a Vibratome to a thickness of 50 μm. Free-floating sections were processed for c-fos immunocytochemistry. Sections were incubated for 20 min in 1% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to inactivate endogenous peroxidase activity and reduce non-specific staining. Sections were washed three times (10 min per wash) in 0.01 M PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBSX), then incubated on a rocking table with c-fos antibody for 48 h at 4°C. This polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, 1 : 20,000) has been raised in rabbit against residues 3–16 of the N-terminal region of the Fos protein. Sections were washed again three times in PBSX prior to being incubated with the biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories, 1 : 200) for at least 1 h at room temperature. Immunostaining was visualized using the standard avidin-biotin technique. After again washing three times in PBSX, the sections were incubated with the avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex (VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories) for at least 1 h, rinsed three times in PBSX and placed in the chromogen 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB, Sigma–for every DAB tablet: 20 μl glucose oxidase, 40 μl ammonium chloride and 160 μl D(+) glucose was added) for 15 min. The sections were again washed three times in PBSX, mounted on gelatinized slides and left overnight to dry. The mounted sections were then dehydrated and defatted through a graded alcohol series to xylene and were coverslipped using entellan (E. Merck, Germany). No c-fos immunoreactivity was observed when the primary antibody was omitted.

Quantification of Fos

Co-ordinates of sagittal planes and limits of the various structures analysed were defined according to the atlas of Paxinos & Watson (1998). In pilot studies sections were examined throughout the brain to determine areas with the most prominent c-fos immunostaining. On this basis, one section, at 2.4 mm lateral to the midline, was selected for counting the number of Fos positive nuclei through each of 13 activated brain areas: PIR, piriform cortex; LO, lateral orbital cortex; CL, claustrum; FR, frontal cortex; SSC, somatosensory cortex; OC, occipital cortex; RS, retrosplenial cortex; CA1-3, fields CA1-3 of Ammon's horn; CPU, caudate putamen; LD, laterodorsal thalamic nucleus; LP, lateral posterior thalamic nucleus; ZO, zonal layer superior colliculus; L5, cerebellar lobulus 5. Regions were analysed in one hemisphere. Quantification of Fos positive nuclei was performed by counting immunopositive cells plotted at either a ×4 or ×10 magnification. Sections were scanned into the computer using Adobe Photoshop 4.0 (Adobe Systems Inc. San Jose, CA, U.S.A.). Cell counts were made with the help of a computer-assisted imaging analysis system (analysis performed on a Macintosh computer using the public domain NIH Image program developed at the U.S. National Institutes of Health and available on the Internet at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/). The density slice option was used to facilitate the counting. The minimum and maximum particle size to be analysed was set to 5 and 55 pixels, respectively. The grey level range of Fos positive nuclei was calibrated for all sections through a given area, as described previously (Auger & Blaustein, 1995). Sections were carefully matched across animals under a microscope according to the morphological structures. Analyses were conducted in random order by an observer blind with respect to treatment.

Drugs

Phencyclidine hydrochloride was generously donated by Bureau of Drug Surveillance (Ottawa, Canada). Sodium nitroprusside was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Drugs were freshly dissolved in 0.9% saline before each experiment and were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) in a volume of 0.1 ml 100 g−1 body weight.

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as the mean and standard error of estimate mean value (s.e.mean) for each experimental group. The behavioural data were analysed by three factor (PCP×SNP×Time) analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures on the third factor. The c-fos data were analysed by two factor (PCP×SNP) ANOVA. For multiple group comparison post hoc analyses were completed using the Tukey test, except for the analysis of the total distance moved during the dark phase, which used a Bonferroni test, since it is more powerful when testing a small number of pairs. Differences revealed with both the ANOVAs and the post hoc tests were considered significant at P<0.05. Data analysis was done using SPSS Base 8.0 for Windows.

Results

Behavioural data obtained during the light phase

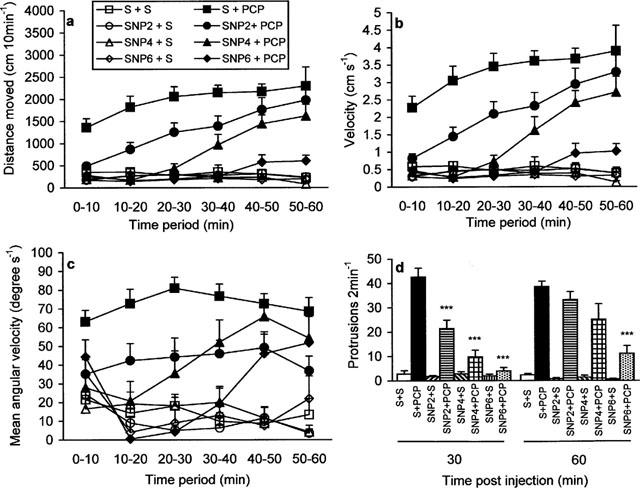

PCP (5 mg kg−1) induced a characteristic behavioural response with hyperactivity, stereotyped behaviour and ataxia. All behavioural effects reached a maximum between 20 and 30 min after injection. Treatment with SNP by itself produced no effect on any behaviour studied but completely abolished PCP-induced behaviour in a dose- and time-dependent manner. These observations were confirmed by three-factorial repeated measures ANOVA. Analysis of the hyperactivity (total distance moved and velocity) indicated a significant difference in the effects of PCP (total distance moved: F(5,195)=19.34, P<0.0001; velocity: F(5,195)=19.60, P<0.0001) and SNP (total distance moved: F(15,195)=2.43, P<0.005; velocity: F(15,195)=2.37, P<0.005) over time and a strong interaction between these three factors (PCP×SNP×Time: total distance moved: F(15,195)=3.07, P<0.0001; velocity: F(15,195)=3.06, P<0.0001). Further analysis revealed that the lowest dose of SNP (2 mg kg−1) decreased significantly PCP-induced hyperactivity during the first 40 min (P<0.0001, 0–20 min; P<0.001, 20–30 min; P<0.05, 30–40 min). SNP at the dose of 4 mg kg−1 was effective for 50 min (P<0.0001, 0–40 min; P<0.05, 40–50 min), whereas at 6 mg kg−1 produced a complete blockade of PCP-induced hyperactivity (P<0.0001, 0–60 min), (Figure 1a,b). We also observed that control-treated animals (saline+saline, SNP+saline) made large turns around the arena, being forced to turn only when encountering a wall. Their mean angular velocity was between 0 and 30 degrees s−1, (Figure 1c). PCP-treated animals made a lot of small turns around their axis, with the mean angular velocity of approximately 70 degrees. Analysis of the mean angular velocity indicated a significant difference in the effects of PCP (F(5,200)=5.83, P<0.0001) and SNP (F(15,200)=3.18, P<0.0001) over time and no interaction between these three factors (PCP×SNP×Time). However, there was a significant interaction between PCP and SNP (F(3,38)=6.66, P<0.005), which justified further analysis. The mean angular velocity of PCP-treated animals was significantly decreased following SNP treatment and animals were observed to make fewer small turns around their axis. SNP at the dose of 2 mg kg−1 was effective between 10 and 50 min (P<0.0001, 10–30 min; P<0.005, 30–40 min; P<0.05, 40–50 min), at 4 mg kg−1 during the first 40 min (P<0.05, 0–10 min; P<0.0001, 10–30 min; P<0.05, 30–40 min) while at 6 mg kg−1, it was effective at 10–50 min (P<0.0001, 10–40 min; P<0.05, 40–50 min), (Figure 1c). In the ataxia experiments ANOVA indicated a significant difference in the effects of PCP (F(1,33)=12.61, P<0.01), but not SNP, over time, although SNP×Time value was at the borderline (F(3,33)=2.67, P=0.063). However, a significant interaction between these three factors was found (PCP×SNP×Time: F(3,33)=3.22, P<0.05). Post-hoc analysis revealed that at 30 min after the injection PCP-induced ataxia was significantly reduced with SNP 2, 4 and 6 mg kg−1, while at 60 min post injection only 6 mg kg−1 was effective (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

The effect of SNP on PCP-induced behaviour during the light phase of the light/dark cycle. (a) total distance moved, (b) velocity, (c) mean angular velocity. Data are expressed as mean+s.e.mean (n=8–12 per group). Significant differences between groups are detailed in the text. (d) ataxia. Data are expressed as mean+s.e.mean (n=5–6 per group). Significant differences between groups are indicated as follows: ***P<0.0001, compared to saline+PCP (Tukey test).

Behavioural data obtained during the dark phase

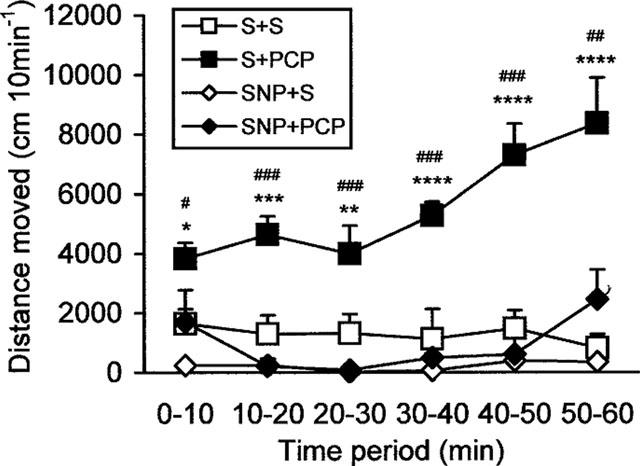

Analysis of the total distance moved indicated a significant difference in the effects of PCP (F(5,60)=4.40, P<0.005), but not SNP (F(5,60)=1.27, P=0.29), over time. Although there was no significant interaction between PCP and SNP over time (PCP×SNP×Time: F(5,60)=2.20, P=0.066), a strong interaction between PCP and SNP was found (F(1,12)=25.68, P<0.0001), which justified the post-hoc analysis. As shown in Figure 2, SNP at the dose of 6 mg kg−1 reversed PCP-induced hyperlocomotor activity at all time periods observed (P<0.05, 0–10 min; P<0.0001, 10–50 min; P<0.005, 50–60 min). Although saline-treated animals showed higher level of locomotor activity than SNP-treated animals statistical analysis of the total distance moved revealed no significant difference between these groups at any of the time points observed (P=0.15, 0–10 min; P=0.06, 10–20 min; P=0.14, 20–30 min; P=0.21, 30–40 min; P=0.27, 40–50 min; P=0.73, 50–60 min).

Figure 2.

The effect of SNP (6 mg kg−1) on PCP-induced hyperlocomotor activity during the dark phase of the light/dark cycle. Data are expressed as mean±s.e.mean (n=4 per group). Significant differences between groups are indicated as follows: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005, ****P<0.0001, compared to saline+saline; #P<0.06, ##P<0.005, ###P<0.0001, compared to SNP+PCP (Bonferroni test).

c-fos data

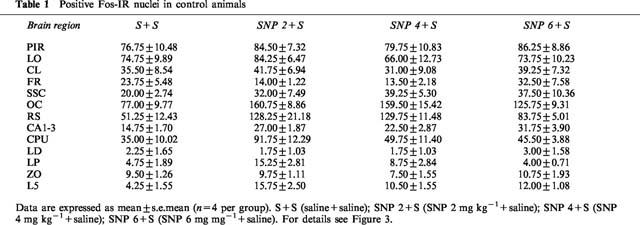

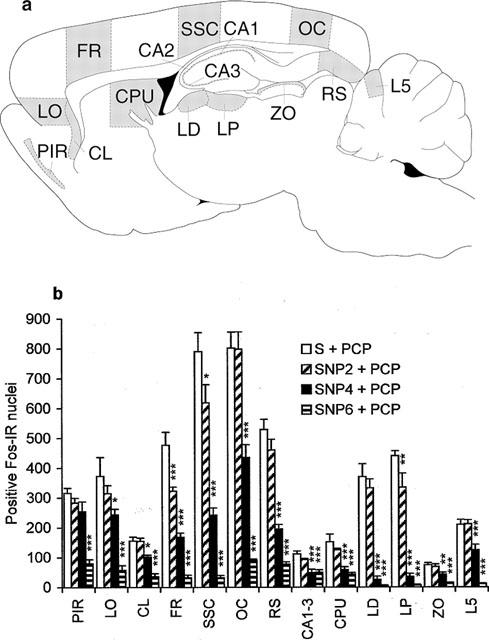

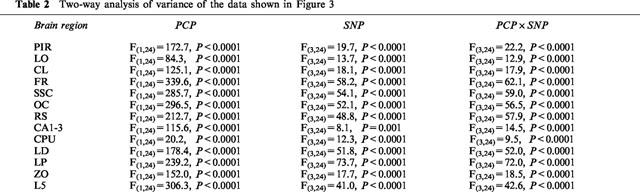

Increased expression of the protein product of the immediate-early gene c-fos is now widely recognized as a reliable technique to identify neuronal populations of metabolically activated brain regions (Sagar et al., 1988; Hughes & Dragunov, 1995; Herrera & Robertson, 1996). Saline administration induced a low-level Fos protein expression in the cortical regions, claustrum, periventricular portion of the striatum and hippocampus (Table 1). PCP induced widespread expression of c-fos in neurones in many brain regions, as compared with saline-treated animals (P<0.0001, in all the brain regions presented in Figure 3a). Moreover, PCP induced regionally different effects on c-fos expression, suggesting regionally different patterns of neuronal activity. The most prominent immunostaining was observed in the cortical neurones. PCP induced moderate c-fos expression in the thalamic nuclei, cerebellar granule cell layer, claustrum, superior colliculus and hippocampus. Rare Fos positive nuclei were observed in basal ganglia regions, although there was a moderate expression in the periventricular portion of the striatum. As shown in Figure 3b, SNP dose-dependently blocked PCP-induced c-fos expression. While 2 mg kg−1 was effective only in the frontal and somatosensory cortex and lateral posterior thalamic nucleus, 4 mg kg−1 induced a significant decrease of Fos positive neurones in all the brain regions except in piriform cortex. At 6 mg kg−1, SNP completely abolished PCP-induced neuronal activation in all the brain regions. There was no difference in c-fos expression between the groups given saline+saline, SNP (2, 4 or 6 mg kg−1)+saline (Table 1) and the group given SNP 6 mg kg−1+PCP.

Table 1.

Positive Fos-IR nuclei in control animals

Figure 3.

Neuronal activation. (a) Schematic drawing adapted from Paxinos & Watson (1998), showing brain regions activated by PCP. PIR, piriform cortex; LO, lateral orbital cortex; CL, claustrum; FR, frontal cortex; SSC, somatosensory cortex; OC, occipital cortex; RS, retrosplenial cortex; CA1-3, fields CA1-3 of Ammon's horn; CPU, caudate putamen; LD, laterodorsal thalamic nucleus; LP, lateral posterior thalamic nucleus; ZO, zonal layer superior colliculus; L5, cerebellar lobulus 5. Grey areas are chosen for quantitative analysis. (b) The effect of SNP on PCP-induced c-fos expression. Due to limited space, control groups (saline+saline, SNP 2 mg kg−1+saline, SNP 4 mg kg−1+saline, SNP 6 mg kg−1+saline) are presented in the Table 1. Data are expressed as mean+s.e.mean (n=4 per group). Two-factorial ANOVA indicated a significant effect of PCP (P<0.0001 in all the brain regions), SNP (P<0.0001 in all the brain regions except in hippocampus where P=0.001) and interaction between these two factors (PCP×SNP: P<0.0001 in all the brain regions). For details see Table 2. Significant differences between groups are indicated as follows: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.0001, compared to saline+PCP (Tukey test).

Discussion

In agreement with previous findings (Yang et al., 1991; Toru et al., 1994; Steinpreis, 1996), the present data indicate that PCP induces a complex behavioural syndrome consisting of hyperlocomotion, stereotyped behaviour and ataxia. The present study also shows that PCP induces a widespread neuronal activation, as monitored by c-fos expression. The overall distribution patterns of c-fos induced by PCP appears consistent with those of previously reported c-fos mRNA and Fos protein, induced by higher doses of PCP (10–50 mg kg−1), (Näkki et al., 1996; Sharp, 1997). These patterns are distinct from those following injection of other schizophrenomimetic dopamine agonists such as amphetamine and cocaine (Graybiel et al., 1990; Umino et al., 1995), but resemble those induced by other NMDA antagonists such as ketamine and MK-801 (Gass et al., 1993; Duncan et al., 1998). However, in addition to blocking NMDA receptors, PCP also interacts with many other neurotransmitter systems. Therefore, multiple receptors and different pathways, other than glutamatergic, may be involved in the activation of c-fos. Consistent with this notion is the observation that c-fos distribution following PCP administration does not correspond completely to the distribution of NMDA receptors (Thornberg & Saklad, 1996). For instance, moderate to very low c-fos expression was observed in the hippocampus and striatum which contain high densities of NMDA receptors. The metabolic activation induced by PCP may result from functional antagonism of inhibitory neural processes, such as blocking NMDA receptors on γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-containing neurones, thus reducing inhibitory tone in the brain. Although PCP activates many brain regions the most prominent effect was observed in the cortical regions. This is particularly interesting because the cerebral cortex has been considered to be a therapeutic target of antipsychotic drugs (Lidow et al., 1998). Recent evidence from brain imaging studies also indicated cortical involvement in positive, negative and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia (Dolan et al., 1995; Silbersweig & Stern, 1996; Andreasen, 1997; Okubo et al., 1997; Tamminga, 1999). Pre-treatment with SNP blocked both PCP-induced behavioural effects and c-fos expression. SNP-induced changes in the c-fos expression thus appear to be a reflection of biochemical events in cell bodies of neurones and appear to be related to changes in behavioural functions.

The precise mechanism by which SNP produces its dramatic effects in PCP-treated animals is not clear. SNP, in addition to the generation of NO and increase of cyclic GMP (cGMP) production, may also have a direct action at the NMDA receptor (Fujimori & Pan-Hou, 1991; Hoyt et al., 1992). SNP has also been reported to prevent the central action of NOS inhibitors in several animal models (Lin et al., 1995; Liu et al., 1997; Ingram et al., 1998a,1998b), supporting the notion that SNP has pharmacological effects on the brain NO system. Therefore, it is unlikely that the blocking effect of SNP on PCP-induced behaviour and neuronal activation found in this study can be due to a non-specific effect, secondary to vasodilating action of NO. Consistent with our results, Yamada et al. (1996) have demonstrated that S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine, which is also an NO releaser, completely reverses the behavioural effects induced by MK-801, another noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist. We also found in the present study that L-arginine (1 g kg−1), a nitric oxide precursor, does not interfere with the behavioural effects induced by PCP (behavioural observation only) nor with c-fos expression (data not shown). This could be attributed to inability of exogenous L-arginine to generate NO since it has been shown that the production of NO by the constitutive NOS isoforms is not dependent on extracellular substrate (Szabo, 1996). Moreover, it is well known that L-arginine interacts with many cellular processes including the urea cycle and polyamine pathway (Dawson & Dawson, 1996). Therefore, exogenous administration of L-arginine may preferentially lead to the synthesis of other substances rather than NO. We propose that SNP blocks the effects of PCP through the activation of the NO-guanylyl cyclase signalling pathway. This suggests that the effects of PCP are at least in part the result of a decrease in NO. SNP presumably reverses this effect by providing NO, reversing the behavioural effects of PCP and also decreasing the expression of c-fos. In agreement with this assumption, clinical studies show that treatment with antipsychotic drugs significantly increases low levels of cyclic GMP found in drug-free patients with schizophrenia (Nagao et al., 1979; Gattaz et al., 1984). Our results raise the possibility that the mechanism of action of antipsychotic drugs might be mediated, at least in part, via the NO pathway. The present results are also consistent with our previous study showing that L-NAME, a negative NO modulator, potentiates both PCP-induced behaviour and neuronal activation (Bujas-Bobanovic et al., 1998b). Thus, we confirmed the data of Noda et al. (1995) showing that NOS inhibitors enhance PCP-induced behaviours in mice. However, our results are in contrast to those of Johansson et al. (1997, 1998, 1999) suggesting that NOS inhibition blocks PCP-induced effects. There is at least one explanation for these different results. To analyse thoroughly the effects of drugs on PCP-induced behaviour it is necessary to analyse all three behaviours (locomotor activity, stereotyped behaviour, ataxia) simultaneously. However, Johansson et al. monitored only locomotor activity and stereotyped behaviour. In our previous studies we observed that ataxia, produced by high doses of PCP (Bujas-Bobanovic et al., 1998a), or by low doses of PCP in combination with L-NAME (Bujas-Bobanovic et al., 1998b), impairs the ability of animals to execute hyperlocomotor activity and stereotyped behaviours. It is also important to point out that acute injection of NOS inhibitors produces a significant decrease in the spontaneous locomotor activity, as shown by many authors (Connop et al., 1994; Sandi et al., 1995; Yamada et al., 1995; Dzoljic et al., 1997; Volke et al., 1997; Maren, 1998). Therefore, studies that rely exclusively on only locomotor activity and/or stereotyped behaviours may result in misleading conclusions. Our findings are supported by the observation that PCP is an effective inhibitor of brain NOS (Osawa & Davila, 1993; Chetty et al., 1995) and that NOS activity is significantly decreased by acute PCP treatment (Noda et al., 1996). Moreover, it has been repeatedly shown that PCP, and its analogue, MK-801, have an effect similar to that of NOS inhibitors. For example, hippocampal long-term potentiation is inhibited by NMDA antagonists and by NOS inhibitors (O'Dell et al., 1991; Schuman & Madison, 1991). These antagonists have also been found to protect against NMDA-induced neurotoxicity (Haberny et al., 1992; Dawson et al., 1993; Ayata et al., 1997). They also block NMDA-mediated convulsions (Nakamura et al., 1995), and impair learning and memory in several animal models (Ward et al., 1990; Chapman et al., 1992; Böhme et al., 1993; Hölscher & Rose, 1993; Hölscher et al., 1995; Yamada et al., 1995; Harder et al., 1998; Ingram et al., 1998a,1998b; Meyer et al., 1998; Zou et al., 1998). However, there is also evidence that inhibition of NOS does not impair learning or prevent the induction of long-term potentiation and NMDA-induced convulsions in animals (Buisson et al., 1993; Bannerman et al., 1994a,1994b).

Although extrapolation of data from rodent models to complex human syndromes such as PCP psychosis or schizophrenia may be problematic, hyperlocomotion in rodents has been generally used as a predictor of the propensity of a drug to elicit or exacerbate psychosis in humans (Castellani & Adams, 1981; Greenburg & Segal, 1985; French, 1986; Carlsson et al., 1993; Jackson et al., 1994; Ogren & Goldstein, 1994; Steinpreis et al., 1994; Krystal et al., 1995; Goldman-Rakic, 1996; Verma & Moghaddam, 1996; Mog-haddam & Adams, 1998). Therefore, the ability of a compound to antagonise PCP-induced behaviour and neuronal activation would be predictive of its antipsychotic properties in humans. There is evidence that the behavioural and biological abnormalities induced by PCP administration in humans resemble those observed in schizophrenia (Toru et al., 1994; Steinpreis, 1996; Thornberg & Saklad, 1996). If so, drugs targeting the glutamate-NO system may represent a novel approach to the treatment of schizophrenia. Indeed, these observations now provide us with a new test for the validity of the PCP model for schizophrenia. If PCP is a valid model, SNP or a related NO donor should reduce at least some of the symptoms of schizophrenia. Even if NO donors prove ineffective in schizophrenia, they may be useful in the treatment of PCP-induced psychosis.

Table 2.

Two-way analysis of variance of the data shown in Figure 3.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Murphy for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Dr B. Rusak for valuable discussion about rats' behaviour during the dark phase of the light/dark cycle. This work was supported by the grants from the Queen Elizabeth II HSC Research Fund (S.M. Dursun), the MRC of Canada (H.A. Robertson) and Canadian Psychiatric Foundation (S.M. Dursun). S.M. Dursun is a Dalhousie University Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Scholar.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CA1-3

fields CA1-3 of Ammon's horn

- cGMP

cyclic GMP

- CL

claustrum

- CPU

caudate putamen

- DAB

3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride

- FR

frontal cortex

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- L5

cerebellar lobulus 5

- LD

laterodorsal thalamic nucleus

- L-NAME

L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester

- LO

lateral orbital cortex

- LP

lateral posterior thalamic nucleus

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- OC

occipital cortex

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PBSX

PBS with 0.4% Triton X-100

- PCP

phencyclidine

- PIR

piriform cortex

- RS

retrosplenial cortex

- S

saline

- s.e.mean

standard error of estimate mean value

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

- SSC

somtosensory cortex

- ZO

zonal layer superior colliculus

References

- ANDREASEN N.C. Linking mind and brain in the study of mental illnesses: A project for a scientific psychopathology. Science. 1997;275:1586–1593. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUGER A.P., BLAUSTEIN J.D. Progesterone enhances an estradiol-induced increase in fos immunoreactivity in localized regions of female rat forebrain. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:2272–2279. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02272.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AYATA C., AYATA G., HARA H., MATTHEWS R.T., BEAL M.F., FERRANTE R.J., ENDRES M., KIM A., CHRISTIE R.H., WAEBER C., HUANG P.L., HYMAN B.T., MOSKOWITZ M.A. Mechanisms of reduced striatal NMDA excitotoxicity in type I nitric oxide synthase knock-out mice. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:6908–6917. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-06908.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANNERMAN D.M., CHAPMAN P.F., KELLY P.A.T., BUTCHER S.P., MORRIS R.G.M. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase does not impair spatial learning. J. Neurosci. 1994a;14:7404–7414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-12-07404.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANNERMAN D.M., CHAPMAN P.F., KELLY P.A.T., BUTCHER S.P., MORRIS R.G.M. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase does not prevent the induction of long-term potentiation in vivo. J. Neurosci. 1994b;14:7415–7425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-12-07415.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BÖHME G.A., BON C., LEMAIRE M., REIBAUD M., PIOT O., STUTZMANN J.M., DOBLE A., BLANCHARD J.C. Altered synaptic plasticity and memory formation in nitric oxide synthase inhibitor-treated rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:9191–9194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUISSON A., LAKHMECHE N., VERRECCHIA C., PLOTKINE M., BOULU R.G. Nitric oxide: an endogenous anticonvulsant substance. Neuroreport. 1993;4:444–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUJAS-BOBANOVIC M., DURSUN S.M., ROBERTSON H.A. The dose-dependent effects of phencyclidine on behaviour and immediate-early genes in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998a;124:70P. [Google Scholar]

- BUJAS-BOBANOVIC M., DURSUN S.M., ROBERTSON H.A. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-NAME enhances phencyclidine-induced behaviours and neural activation in rat brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998b;124:63P. [Google Scholar]

- CARLSSON A., SVENSSON A., CARLSSON M.L. Future strategies in the discovery of new antipsychotic agents: focus on dopamine-glutamate interactions New Generation of Antipsychotic Drugs: Novel Mechanisms of Action. 1993Basel: Basel; 118–129.ed. Brunello, N., Mendlewicz. J. & Racagni, G. pp [Google Scholar]

- CASTELLANI S., ADAMS P.M. Effects of dopaminergic drugs on phencyclidine-induced behavior in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1981;20:371–374. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(81)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAPMAN P.F., ATKINS C.M., ALLEN M.T., HALEY J.E., STEINMETZ J.E. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis impairs two different forms of learning. Neuroreport. 1992;3:567–570. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199207000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHETTY C.S., HUSSAIN S., SLIKKER W., ALI S.F. Effects of phencyclidine on nitric oxide synthase activity in different regions of rat brain. Res. Comm. Alco. Subst. Abuse. 1995;16:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- CONNOP B.P., ROLFE N.G., BOEGMAN R.J., JHAMANDAS K., BENINGER R.J. Potentiation of NMDA-mediated toxicity on nigrostriatal neurons by a low dose of 7-nitro indazole. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:1439–1445. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON V.L., DAWSON T.M. Nitric oxide actions in neurochemistry. Neurochem. Int. 1996;29:97–110. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(95)00149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON V.L., DAWSON T.M., BARTLEY D.A., UHL G.R., SNYDER S.H. Mechanisms of nitric oxide-induced neurotoxicity in primary brain cultures. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:2651–2661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02651.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOLAN R.J., FLETCHER P., FRITH C.D., FRISTON K.J., FRACKOWIAK R.S.J., GRASBY P.M. Dopaminergic modulation of impaired cognitive activation in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Nature. 1995;378:180–182. doi: 10.1038/378180a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUNCAN G.E., MOY S.S., KNAPP D.J., MUELLER R.A., BRESSE G.R. Metabolic mapping of the rat brain after subanesthetic doses of ketamine: potential relevance to schizophrenia. Brain Res. 1998;787:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01390-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DZOLJIC E., DE VRIES R., DZOLJIC M.R. New and potent inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase reduce motor activity in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 1997;87:209–212. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)02281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRENCH E.D. Effects of SKF 10,047, phencyclidine and other psychomotor stimulants in the rat following 6-hydroxydopamine lesion of the ventral tegmental area. Neuropharmacology. 1986;25:447–450. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(86)90241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUJIMORI H., PAN-HOU H. Effect of nitric oxide on L-3H-glutamate binding to rat brain synaptic membranes. Brain Res. 1991;554:355–357. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90217-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GASS P., HERDEGEN T., BRAVO R., KIESSLING M. Induction and suppression of immediate early genes in specific rat brain regions by the non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist MK-801. Neuroscience. 1993;53:749–759. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90621-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GATTAZ W.F., CRAMER H., BECKMANN H. Haloperidol increases the cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of cyclic GMP in schizophrenic patients. Biol. Psychiatry. 1984;19:1229–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDMAN-RAKIC P.S. Memory: recording experience in cells and circuits: diversity in memory research. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:13435–13447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAYBIEL A.M., MORATELLA R., ROBERTSON H.A. Amphetamine and cocaine induce drug-specific activation of the c-fos gene expression in striosome-matrix compartments and limbic subdivisions of the striatum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:6912–6916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREENBURG B.D., SEGAL D.S. Acute and chronic behavioural interactions between PCP and amphetamine: evidence for a dopaminergic role in some PCP-induced behaviours. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1985;23:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HABERNY K.A., POU S., ECCLES C. Potentiation of quinolinate-induced hippocampal lesions by inhibition of NO synthesis. Neurosci. Lett. 1992;146:187–190. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90074-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARDER J.A., ABOOBAKER A.A., HODGETTS T.C., RIDLEY R.M. Learning impairments induced by glutamate blockade using dizocilpine (MK-801) in monkeys. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:1013–1018. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERRERA D.G., ROBERTSON H.A. Activation of c-fos in the brain. Progress Neurob. 1996;50:83–107. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HÖLSCHER C., ROSE S.P. Inhibiting synthesis of the putative retrograde messenger nitric oxide results in amnesia in a passive avoidance task in the chick. Brain Res. 1993;619:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91611-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HÖLSCHER C., MCGLINCHEY L., ANWYL R., ROWAN M.J. 7-Nitro indazole, a selective neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibitor in vivo, impairs spatial learning in the rat. Learn. Memory. 1995;2:267–278. doi: 10.1101/lm.2.6.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOYT K.R., TANG L.H., AIZENMAN E., REYNOLDS I.J. Nitric oxide modulates NMDA-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ in cultured rat forebrain neurones. Brain Res. 1992;592:310–316. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91690-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUGHES P., DRAGUNOV M. Induction of immediate-early genes and the control of neurotransmitter-regulated gene expression within the nervous system. Pharmacol. Rev. 1995;47:133–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IGNARRO L., MURAD F. Nitric oxide: Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Therapeutic Implications. San Diego: Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- INGRAM D.K., SPANGLER E.L., KAMETANI H., MEYER R.C., LONDON E.D. Intracerebroventricular injection of Nω-nitro-L-arginine in rats impairs learning in a 14-unit T-maze. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998a;341:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01427-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INGRAM D.K., SPANGLER E.L., MEYER R.C., LONDON E.D. Learning in a 14-unit T-maze is impaired in rats following systemic treatment with N-W-nitro-L-arginine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998b;341:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01426-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JACKSON D.M., JOHANSSON C., LINDGREN L.M., BENGTSSON A. Dopamine receptor antagonists block amphetamine and phencyclidine-induced motor stimulation in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1994;48:465–471. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90554-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JENTSCH J.D., REDMOND D.E., ELSWORTH J.D., TAYLOR J.R., YOUNGREN K.D., ROTH R.H. Enduring cognitive deficits and cortical dopamine dysfunction in monkeys after long-term administration of phencyclidine. Science. 1997;277:953–955. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHANSSON C., DEVENEY A.M., REIF D., JACKSON D.M. The neuronal selective nitric oxide inhibitor AR-R 17477, blocks some effects of phencyclidine, while having no observable behavioural effect when given alone. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1999;84:226–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1999.tb01487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHANSSON C., JACKSON D.M., SVENSSON L. Nitric oxide synthase inhibition blocks phencyclidine-induced behavioural effects on prepulse inhibition and locomotor activity in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1997;131:167–173. doi: 10.1007/s002130050280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHANSSON C., MAGNUSSON O., DEVENEY A.M., JACKSON D.M., ZHANG J., ENGEL J.A., SVENSSON L. The nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, L-NAME, blocks certain phencyclidine-induced but not amphetamine-induced effects on behaviour and brain biochemistry in the rat. Prog. Neuropsyhopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 1998;22:1341–1360. [Google Scholar]

- KRYSTAL J.H., KARPER L., BANNETT A., ABI-SAAB D., SOUZA C., ABI-DARGHAM A., CHARNEY D. Modulating ketamine-induced thought disorder with lorazepam and haloperidol in humans. Schizophrenia Res. 1995;15:156. [Google Scholar]

- LIDOW M.S., WILLIAMS G.V., GOLDMAN-RAKIC P.S. The cerebral cortex: a case for common site of action of antipsychotics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:136–140. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN A.M.Y., KAO L.S., CHAI C.Y. Involvement of nitric oxide in dopaminergic neurotransmission in rat striatum–an in vivo electrochemical study. J. Neurochem. 1995;65:2043–2049. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65052043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU Q.S., JIA Y.S., JU G. Nitric oxide inhibits neuronal activity in the supraoptic nucleus of the rat hypothalamic slices. Brain Res. Bull. 1997;43:121–125. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(96)00209-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAREN S. Effects of 7-nitroindazole, a neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) inhibitor, on locomotor activity and contextual fear conditioning in rats. Brain Res. 1998;804:155–158. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00668-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MELTZER H.Y., STAHL S.M. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: a review. Schizophrenia Bull. 1976;2:19–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/2.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYER R.C., SPANGLER E.L., PATEL N., LONDON E.D., INGRAM D.K. Impaired learning in rats in a 14-unit T-maze by 7-nitroindazole, a neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, is attenuated by the nitric oxide donor, molsidomine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;341:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01428-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOGHADDAM B., ADAMS B.W. Reversal of phencyclidine effects by a group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist in rats. Science. 1998;281:1349–1352. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGAO T., OHSHIMO T., MITSUNOBU K., SATO M., OTSUKI S. Cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolites and cyclic nucleotides in chronic schizophrenic patients with tardive dyskinesia or drug-induced tremor. Biol. Psychiatry. 1979;14:509–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMURA T., YAMADA K., HASEGAWA T., NABESHIMA T. Possible involvement of nitric oxide in quinolinic acid-induced convulsion in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1995;51:309–312. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)00385-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NÄKKI R., SHARP F.R., SAGAR S.M., HONKANIEMI J. Effects of phencyclidine on immediate early gene expression in the brain. J. Neurosci. Res. 1996;45:13–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960701)45:1<13::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NODA Y., YAMADA K., FUROKAWA H., NABESHIMA T. Involvement of nitric oxide in phencyclidine-induced hyperlocomotion in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;286:291–297. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00464-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NODA Y., YAMADA K., KOMORI Y., SUGIHARA H., FURUKAWA H., NABESHIMA T. Role of nitric oxide in the development of tolerance and sensitization to behavioural effects of phencyclidine in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1579–1585. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'DELL T.J., HAWKINS R.D., KANDEL E.R., ARANCIO O. Tests of the roles of two diffusible substances in long-term potentiation: evidence for nitric oxide as a possible early retrograde messenger. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:11285–11289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OGREN S.O., GOLDSTEIN M. Phencyclidine and dizocilpine-inded hyperlocomotion are differentially mediated. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1994;11:167–177. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1380103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKUBO Y., SUHARA T., SUZUKI K., KOBAYASHI K., INOUE O., TERESAKI O., SOMEYA Y., SASSA T., SUDO Y., MATSUSHIMA E., IYO M., TATENO Y., TORU M. Decreased prefrontal dopamine D1 receptors in schizophrenia revealed by PET. Nature. 1997;385:634–636. doi: 10.1038/385634a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSAWA Y., DAVILA J.C. Phencyclidine, a psychotomimetic agent and drug of abuse, is a suicide inhibitor of brain nitric oxide synthase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1993;194:1435–1439. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAXINOS G., WATSON C. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. [Google Scholar]

- SAGAR S.M., SHARP F.R., CURRAN T. Expression of c-fos protein in the brain: metabolic mapping at the cellular level. Science. 1988;240:1328–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.3131879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANDI C., VENERO C., GUAZA C. Decreased spontaneous motor activity and startle response in nitric oxide synthase inhibitor-treated rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;277:89–97. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00068-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHUMAN E.M., MADISON D.V. A requirement for the intercellular messenger nitric oxide in long-term potentiation. Science. 1991;254:1503–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.1720572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEEMAN P., LEE T., CHAU-WONG M., WONG K. Antipsychotic drug doses and neuroleptic/dopamine receptors. Nature. 1976;261:717–719. doi: 10.1038/261717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARP J.W. Phencyclidine (PCP) acts at σ sites to induce c-fos gene expression. Brain Res. 1997;758:51–58. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SILBERSWEIG D., STERN E. Functional neuroimaging of hallucinations in schizophrenia–toward an integration of bottom-up and top-down approaches. Mol. Psychiatry. 1996;1:367–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINPREIS R.E. The behavioural and neurochemical effects of phencyclidine in humans and animals: some implications for modelling psychosis. Behav. Brain Res. 1996;74:45–55. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINPREIS R.E., SOKOLOWSKI J.D., PAPANIKOLAOU A., SALAMONE J.D. The effects of haloperidol and clozapine on PCP- and amphetamine-induced suppression of social behavior in the rat. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1994;47:579–585. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZABO C. Physiological and pathophysiological roles of nitric oxide in the central nervous system. Brain Res. Bull. 1996;41:131–141. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(96)00159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAMMINGA C.A. Schizophrenia and glutamateric transmission. Crit. Rev. Neurobiol. 1998;12:21–36. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v12.i1-2.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAMMINGA C.A. Glutamatergic aspects of schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1999;174:12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORNBERG S.A., SAKLAD S.R. Review of NMDA receptors and phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16:82–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TORU M., KURAMAJI A., ISHIMARU M. Excitatory amino acids: implications for psychiatric disorders research. Life Sci. 1994;55:1683–1699. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UMINO A., NISHIKAWA T., TAKAHASHI K. Methamphetamine-induced nuclear c-fos in rat brain regions. Neurochem. Int. 1995;26:85–90. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(94)00096-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERMA A., MOGHADDAM B. NMDA receptor antagonists impair prefrontal cortex function as assessed via spatial delayed alternation of performance in rats: modulation by dopamine. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:373–379. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00373.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VOLKE V., SOOSAAR A., KõKS S., BOURIN M., MÄNNISTÖ P.T., VASAR E. 7-Nitroindazole, a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, has anxiolytic-like properties in exploratory models of anxiety. Psychopharmacology. 1997;131:399–405. doi: 10.1007/s002130050309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARD L., MASON S.E., ABRAHAM W.C. Effects of the NMDA antagonists CPP and MK-801 on radial arm maze performance in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1990;35:785–790. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(90)90359-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMADA K., NODA Y., HASEGAWA T., KOMORI Y., NIKAI T., SUGIHARA H., NABESHIMA T. The role of nitric oxide in dizocilpine-induced impairment of spontaneous alteration behaviour in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;276:460–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMADA K., NODA Y., NAKAYAMA S., KOMORI Y., SUGIHARA H., HASEGAWA T., NABESHIMA T. Role of nitric oxide in learning and memory and in monoamine metabolism in the rat brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:852–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG Q., MOROJI T., TAKAMATSU Y., HAGINO Y., OKUWA M. The effects of intraperitoneally administered phencyclidine on the central nervous system: behavioural and neurochemical studies. Neuropeptides. 1991;19:77–90. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(91)90136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZOU L.B., YAMADA K., TANAKA T., KAMEYADA T., NABESHIMA T. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitors impair reference memory formation in a radial arm maze task in rats. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:323–330. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]