Abstract

The secretagogue 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is implicated in the pathophysiology of cholera. 5-HT released from enterochromaffin cells after cholera toxin exposure is thought to activate non-neuronally (5-HT2 dependent) and neuronally (5-HT3 dependent) mediated water and electrolyte secretion. CT-secretion can be reduced by preventing the release of 5-HT.

Enterochromaffin cells possess numerous receptors that, under basal conditions, modulate 5-HT release. These include basolateral 5-HT3 receptors, the activation of which is known to enhance 5-HT release.

Until now, 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (e.g. granisetron) have been thought to inhibit cholera toxin-induced fluid secretion by blockading 5-HT3 receptors on secretory enteric neurones. Instead we postulated that they act by inhibiting cholera toxin-induced enterochromaffin cell degranulation.

Isolated intestinal segments in anaesthetized male Wistar rats, pre-treated with granisetron 75 μg kg−1, lidoocaine 6 mg kg−1 or saline, were instilled with a supramaximal dose of cholera toxin or saline. Net fluid movement was determined by small intestinal perfusion or gravimetry and small intestinal and luminal fluid 5-HT levels were determined by HPLC with fluorimetric detection.

Intraluminal 5-HT release was proportional to the reduction in tissue 5-HT levels and to the onset of water and electrolyte secretion, suggesting that luminal 5-HT levels reflect enterochromaffin cell activity.

Both lidocaine and granisetron inhibited fluid secretion. However, granisetron alone, and proportionately, reduced 5-HT release.

The simultaneous inhibition of 5-HT release and fluid secretion by granisetron suggests that 5-HT release from enterochromaffin cells is potentiated by endogenous 5-HT3 receptors. The accentuated 5-HT release promotes cholera toxin-induced fluid secretion.

Keywords: Cholera toxin, small intestine, water transport, 5-hydroxytryptamine, granisetron

Introduction

Since it was identified as a potent intestinal secretagogue, the role of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) in disease and health has generated considerable interest (Kisloff & Moore, 1976; Donowitz et al., 1977). The enterochromaffin cell is the major source of 5-HT in the small intestine (Vialli, 1966; Erspamer, 1966). Under basal conditions of net water and electrolyte absorption the control of 5-HT release is thought to depend upon the physico-chemical characteristics of the intestinal luminal milieu (Gershon & Tamir, 1981). Microvilli that project from the apical membrane of the enterochromaffin cell continuously sample the luminal milieu, directly modulating basolateral degranulation activity (Lundberg et al., 1978; Jodal, 1990). Under these conditions a low level of enterochromaffin cell degranulation and 5-HT release is thought to occur. Racke & Schworer (1991) have additionally confirmed the presence of numerous receptors on the basolateral aspect of enterochromaffin cells. When stimulated these receptors further modify the basal release of 5-HT. Some receptors inhibit, while others enhance, 5-HT release. Cholinergic and adrenergic receptors have been identified, and more recently functioning 5-HT receptors have been recognised (Racke & Schworer, 1992; Pettersson et al., 1978). 5-HT4 receptors inhibit and 5-HT3 receptors enhance the basal release of 5-HT (Gebauer et al., 1993). Taken together these observations suggest that a range of neural and hormonal inputs modify basal enterochromaffin cell function from the basolateral aspect of the cell.

In 1983 Nilsson et al. made qualitative observations about enterochromaffin cell activity after cholera toxin exposure, based on small intestinal 5-HT fluorescence. Since 5-HT is a potent secretagogue it was proposed that cholera toxin induces small intestinal water and electrolyte secretion by inducing 5-HT release (Jodal, 1990). Highly selective 5-HT receptor antagonists have subsequently been used in vivo to support this hypothesis (Beubler & Horina, 1990; Beubler et al., 1993; Mourad et al., 1995; Turvill & Farthing, 1997). We have recently demonstrated that, of the heat labile enterotoxins, the recruitment of 5-HT in secretion is unique to cholera toxin (Turvill et al., 1998).

To date the control of enterochromaffin cell 5-HT release under stimulated conditions is largely unexplored. Since basolateral membrane 5-HT3 receptors potentiate 5-HT release from enterochromaffin cells under basal conditions and 5-HT3 receptor antagonists inhibit cholera toxin-induced small intestinal water and electrolyte secretion, we postulated that 5-HT3 receptor antagonists may inhibit secretion by preventing enterochromaffin cell degranulation rather than by blockading 5-HT3 receptors on secretory enteric neurones (Gebauer et al., 1993).

In order to test this hypothesis we determined the effect of the highly selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, granisetron, on luminal 5-HT release and net fluid secretion after cholera toxin exposure. Since 5-HT3 receptors are cation gated ligands, located predominantly on neurones, we also assessed the effect of the local anaesthetic, lidocaine, on cholera toxin-induced 5-HT release and net fluid secretion (Richardson & Engel, 1986). Preliminary experiments were performed to confirm that 5-HT levels in the luminal fluid accurately reflect enterochromaffin cell activity (Beubler & Horina, 1990; Beubler et al., 1989).

Methods

Effect of cholera toxin on water and electrolyte transport and tissue 5-HT levels

All experiments were carried out under project and personal license (PPL 70/3784 and PIL 70/11603) issued by The Home Office.

Habituated male adult Wistar rats, 180–220 g body weight (Tuck and Sons Ltd, Essex) fed with standard chow, were fasted for 18 h with free access to water. The rats were anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbitone (60 mg kg−1) and maintained throughout the experiments by interval intraperitoneal injections (15–30 mg kg−1) as necessary. Animals were kept at 37°C using a heat pad. A midline laparotomy was made and cannulae inserted and ligated into the proximal small intestine (5 cm distal to the duodenojejunal flexure) and into the terminal ileum (1–2 cm proximal to the ileocaecal valve) so as to isolate the whole small intestine. The isolated intestinal segment was gently flushed to clear it of residual contents and returned to the abdominal cavity, which was then closed (Rolston et al., 1987).

The prepared small intestinal segments were then exposed to cholera toxin (75 μg in 6 ml isotonic saline) or saline alone. The volumes in which the toxins were administered were just sufficient to permit complete exposure of the intestinal mucosa, without causing intestinal distension. After a period of 0, 30, 60, 120 or 180 min exposure to cholera toxin, in situ perfusion of the intestinal segment was commenced at a rate of 0.5 ml min−1 with a plasma electrolyte solution containing Na+, 140, K+, 4, Cl−, 104, HCO3−, 40 mmol l−1 to which 5 g l−1 polyethylene glycol (PEG) 4000 and 15×1010 Bq l−1 of [14C]-PEG had been added. Thirty minutes were allowed to elapse to ensure establishment of a steady state, after which the effluent from the distal cannula was collected into pre-weighed tubes during three consecutive 10 min periods. The perfusate samples were weighed and then stored at −50°C for up to 48 h prior to analysis of net water and electrolyte movement.

A short segment of small intestine was then gently lifted out of the abdominal cavity, still attached to its mesentery and a full thickness sample, which had not been stretched or manipulated, was obtained by freeze-clamping. The sample was weighed (approximately 125 mg) and stored in liquid nitrogen prior to preparation. Portions of intestinal wall cut from around the clamp were weighed and then desiccated in an oven at 80°C for 18 h, to obtain tissue wet and dry weights respectively.

Effect of granisetron and lidocaine on cholera toxin-induced intraluminal 5-HT levels and intestinal transport

In studies that required the collection of luminal fluid for the determination of 5-HT concentrations, shorter, jejunal segments were created by inserting the proximal and distal cannulae 20 cm apart.

One group of these rats was exposed for a period of 0, 30, 60, 120 or 180 min to cholera toxin (25 μg in 2 ml isotonic saline) after which the residual luminal effluent in the 20 cm jejunal segments was flushed out and a further 2 ml saline instilled. Thirty min later the fluid was obtained by gentle aspiration into cooled pre-weighed plastic tubes. The tubes were re-weighed, permitting a gravimetric assessment of net fluid transport and then stored in liquid nitrogen prior to preparation for determination of 5-HT and tryptophan levels.

The remaining rats were either pre-treated with granisetron (75 μg kg−1 i.p.), lidocaine (6 mg kg−1 in 2 ml, instilled into the segments for 15 min) or saline alone (2 ml instilled). The jejunal segments were then instilled with 25 μg cholera toxin (in 2 ml saline) or saline alone. After 30 min the clamps were released and the residual luminal contents of the segment obtained. A further 2 ml isotonic saline was then instilled into each segment. This process was repeated over a total of 180 min so that six sequential 30 min collections of luminal contents were obtained.

On completion of all experiments, rats were killed by an overdose of pentobarbitone and the perfused segment was removed, rinsed and blotted. Wet weight and dry weight, after desiccation in an oven at 100°C for 18 h, were obtained.

Cholera toxin was obtained from the Swiss Serum and Vaccine Institute, Berne. [14C]-PEG was obtained from Amersham International. Granisetron were kindly supplied by SmithKline Beecham and all other chemicals were supplied by British Drug House.

Analytical methods

[14C]-PEG concentrations in the three consecutive effluents were measured in triplicate by liquid scintillation spectroscopy in an LKB Wallac Ultra-beta 1210 scintillation counter and the mean value was expressed as μl (min g)−1 of dry intestinal weight. Positive values denote net absorption.

Chloride concentration was determined by a Corning 925 chloride analyzer and sodium by flame photometry (Instrumentation Laboratories 943). Net electrolyte movements are expressed as μmol (min g)−1.

The tissue and luminal samples were homogenized using an Ultra Turrax for 2× 15 s, in 1 ml ice cooled 10% w v−1 perchloric acid containing 2 mmol l−1 sodium EDTA (Barnes et al., 1988). The homogenate was then centrifuged at 14 000 r.p.m. for 15 min at 4°C and the supernatant was decanted and stored in eppendorf tubes at −70°C. Samples were assayed within 48 h of preparation and remained frozen until immediately prior to the analysis.

5-HT and tryptophan levels were determined by high performance liquid chromatography and fluorimetric detection using an ODS column (100×4.6 mm, Hichrom Ltd, Theale, Reading, Berkshire) (Bearcroft et al., 1995). The column was eluted with an LKB 2150 pump set at 1 ml min−1, ambient temperature. A JASCO 821FP fluorimetric detector with a xenon lamp set at ex 290 nm and em 335 nm was used. The mobile phase was a mix of degassed, acidified 100 mmol l−1 ammonium acetate and methanol. Tissue 5-HT and tryptophan are expressed in pmol mg−1 dry weight and luminal 5-HT and tryptophan release as pmol (mg h)−1 or pmol mg−1 whenever appropriate. Tryptophan served as an internal standard.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as median and interquartile range. Differences in net fluid movement and 5-HT and tryptophan levels over time were examined using the Mann-Whitney test and a non-parametric analysis of variance (Kruskal–Wallis test with inter-group analysis) as appropriate. Simple linear regression and a non-parametric test for trend (Cuzick's test) have been used where applicable. Probability values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Effect of cholera toxin on water and electrolyte transport and 5-HT levels

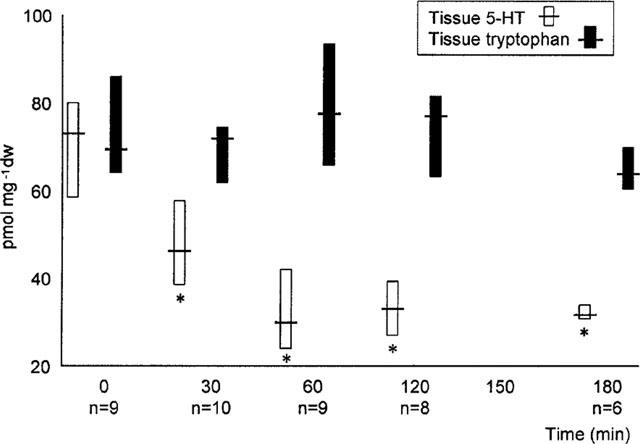

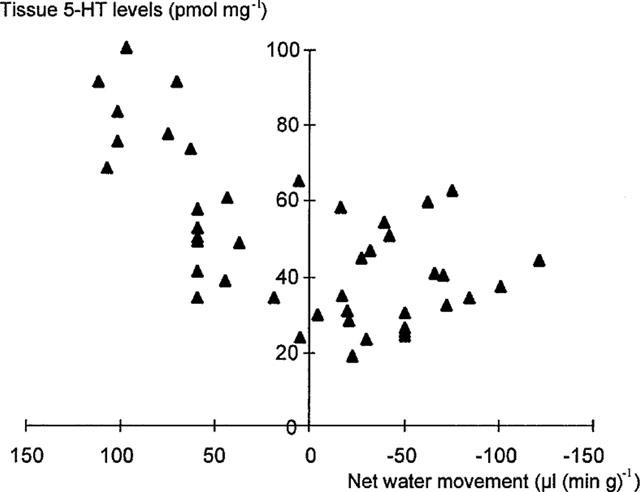

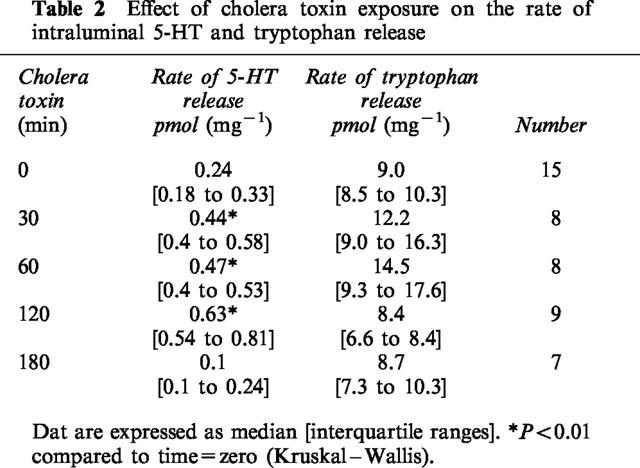

Cholera toxin exposure induced a time dependent, progressive change in small intestinal water and electrolyte movement from net absorption to net secretion. This was associated with a significant reduction in full thickness small intestinal 5-HT, but not tryptophan levels (Figure 1, Table 1). Linear regression analysis confirmed a highly significant correlation between 5-HT levels and net water movement (correlation coefficient, r=0.90; P<0.001) (Figure 2). Cholera toxin exposure also increased the rate of intraluminal 5-HT, but not tryptophan, release when compared with control (Table 2). Linear regression analysis confirmed a significant correlation between median tissue 5-HT levels and median total intraluminal 5-HT release over time (r=0.88; P<0.05). Similarly, a significant correlation was confirmed between net water movement and median total intraluminal 5-HT release (r=0.97; P<0.006).

Figure 1.

Effect of exposure to cholera toxin on tissue 5-HT and tryptophan. Data expressed in pmol mg−1 dry weight and represented as median and interquartile ranges. *P<0.01 compared to time=zero.

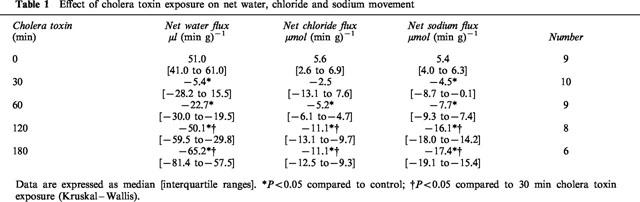

Table 1.

Effect of cholera toxin exposure on net water, chloride and sodium movement

Figure 2.

Correlation between tissue 5-HT levels and net water movement over time. Correlation coefficient, r=0.90; P<0.001).

Table 2.

Effect of cholera toxin exposure on the rate of intraluminal 5-HT and tryptophan release

Effect of granisetron and lidocaine on intestinal transport and cholera toxin-induced 5-HT levels

Intestinal transport

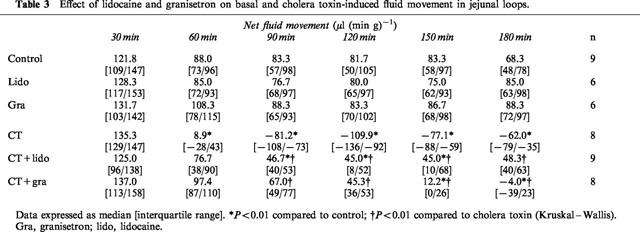

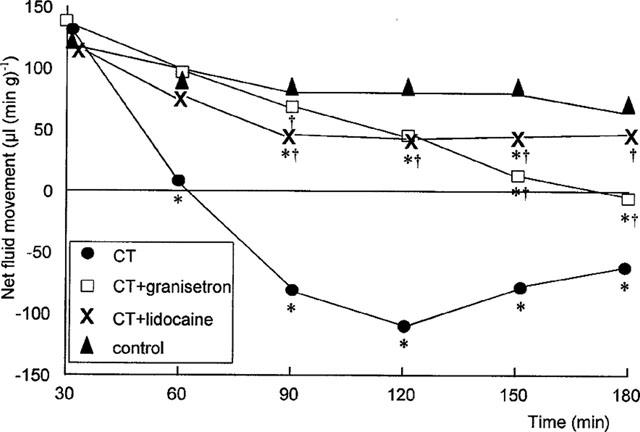

Neither lidocaine nor granisetron had any effect on basal net fluid absorption (Table 3). All rats exposed to cholera toxin alone net secreted fluid. This was prevented by pre-treatment with lidocaine throughout the experiment (Figure 3 and Table 3). Granisetron pre-treatment also significantly inhibited cholera toxin-induced secretion, although not reversing secretion to basal levels.

Table 3.

Effect of lidocaine and granisetron on basal and cholera toxin-induced fluid movement in jejunal loops.

Figure 3.

Effect of granisetron (75 μg kg−1) and lidocaine (6 mg kg−1) on cholera toxin-induced net fluid movement over time. *P<0.01 compared to control; †P<0.01 compared to cholera toxin (Kruskal–Wallis). Data expressed as medians (μl (min g−1).

5-HT release

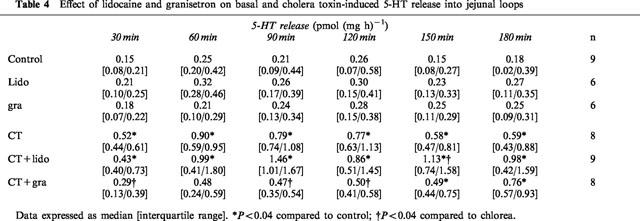

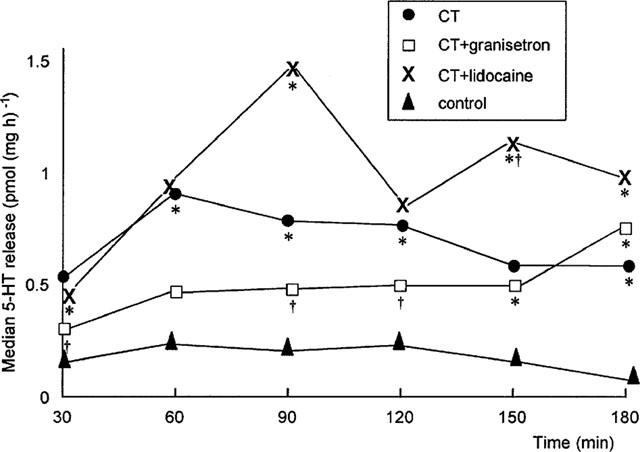

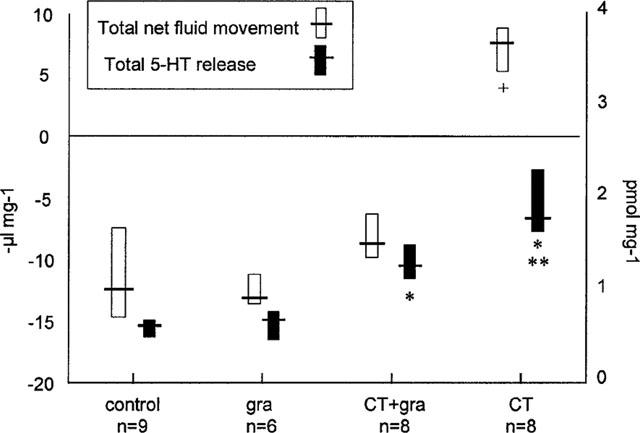

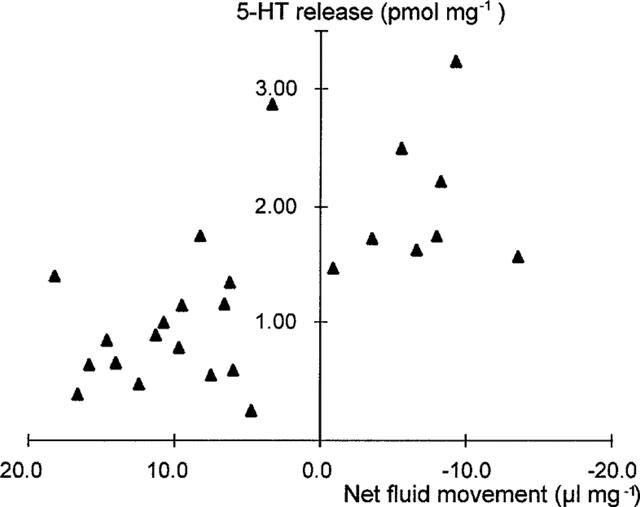

Basal levels of 5-HT release were unaffected by lidocaine or granisetron pre-treatment (Table 4). Cholera toxin exposure induced an early and sustained increase in 5-HT release compared to control (Figure 4 and Table 4). In contrast to its inhibition of net fluid secretion, lidocaine pre-treatment failed to inhibit cholera toxin-induced 5-HT release (Figure 4 and Table 4). However, pre-treatment with granisetron significantly inhibited cholera toxin-induced 5-HT release (Figures 4 and 5 and Table 4). Like its anti-secretory effect, the prevention of 5-HT release by granisetron was only partial (Figure 5). Simple linear regression therefore confirmed a highly significant correlation between net fluid movement after cholera toxin exposure and the degree of 5-HT release (r=0.67 [95% CI 0.37–0.84]; P<0.0003) (Figure 6).

Table 4.

Effect of lidocaine and granisetron on basal and cholera toxin-induced 5-HT release into jejunal loops

Figure 4.

Effect of granisetron (75 μg kg−1) and lidocaine (6 mg kg−1) on median cholera toxin-induced intraluminal 5-HT release. *P<0.04 compared to control; †P<0.04 compared to cholera toxin (Kruskal–Wallis). Data expressed in pmol (mg h)−1.

Figure 5.

Total net fluid movement and total intraluminal 5-HT release after granisetron, with and without cholera toxin. Data expressed as −μl mg−1 and pmol mg−1 respectively and represented as median and interquartile ranges. +P<0.001 compared to control. *P<0.01 compared to control, **P<0.05 compared to cholera toxin+granisetron.

Figure 6.

Correlation between total 5-HT release and net fluid movement in rats in vivo. Correlation coefficient r=0.67 [95% CI 0.37 to 0.84]; P<0.0003.

Tryptophan levels were unaffected by cholera toxin, granisetron or lidocaine.

Discussion

The onset of cholera toxin-induced water and electrolyte secretion in the rat small intestine is accompanied by a 50% reduction in full thickness tissue 5-HT levels. Levels of tryptophan, the internal standard, are unaffected by cholera toxin exposure. It is concluded that such a substantial reduction in tissue 5-HT levels is the result of massive enterochromaffin cell degranulation that overwhelms local 5-HT re-uptake mechanisms. The released 5-HT activates pro-secretory serotonergic pathways to initiate intestinal water and electrolyte secretion (Jodal, 1990). Thereafter, the 5-HT is lost from the intestine by a combination of degradation, release into the intestinal lumen and clearance via the portal venous system and platelet uptake. The close temporal association between 5-HT release and net water secretion supports this hypothesis, as does the significant correlation between tissue 5-HT levels and net water movement.

The concentration of detectable 5-HT in the intestinal lumen is two orders of magnitude less than that detected in tissue. Nonetheless, luminal 5-HT increases and remains elevated for 2 h after exposure to cholera toxin. Furthermore, we have shown a significant correlation between tissue 5-HT levels and the total intraluminal 5-HT release after cholera toxin exposure. This observation supports the assertion by Beubler et al. that intraluminal 5-HT levels reflect enterochromaffin cell activity (Beubler & Horina, 1990; Beubler et al., 1989). By contrast, Gershon et al. (1990) found high resting levels of 5-HT release with no additional increase detected after cholera toxin exposure.

The pathophysiological significance of luminal 5-HT release remains open to speculation, however. Luminal 5-HT may simply reflect the ‘overflow' of the contents of degranulation. Alternatively, since a significant correlation between total luminal 5-HT release and net fluid secretion exists, it may contribute to the total secretory response of the host. Nanomolar rather than the picomolar concentrations of 5-HT detected here, are normally required to induce secretion (Hansen & Jaffe, 1994). However, it is likely that within the mucosal crypts, where enterochromaffin cells predominate, local levels approach nanomolar concentrations.

Pre-treatment with the local anaesthetic, lidocaine, prevents cholera toxin-induced jejunal fluid secretion but not luminal 5-HT release. This observation supports the direct action of cholera toxin on the enterochromaffin cell. Whilst the apical aspect of the enterochromaffin cell is exposed to the small intestinal lumen, the predominant location of the cell deep in the mucosal crypts renders it relatively inaccessible to cholera toxin. We had considered that cholera toxin might induce enterochromaffin cell 5-HT release indirectly, by activating a neuronal pathway that projected to the basolateral aspect of the cell. This was supported by the demonstration of cholinergic and adrenergic receptors on enterochromaffin cells and by the ability of cholera toxin to bind directly to and activate enteric neurons (Jiang et al., 1993; Racke & Schworer, 1991). In the light of our findings this now seems unlikely.

By contrast, the selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, granisetron, not only prevents cholera toxin-induced jejunal net fluid secretion but also, and in proportion, inhibits 5-HT release into the intestinal lumen. Small intestinal 5-HT3 receptors are located on enteric neurons and on the basolateral membrane of enterochromaffin cells. Since neuronal blockade with lidocaine failed to inhibit 5-HT release we conclude that the granisetron acts directly on enterochromaffin cells. Activation of these receptors under basal conditions of net water absorption enhances 5-HT release. Our demonstration of a close correlation between 5-HT release and the degree of cholera toxin-induced fluid secretion supports the hypothesis that, following cholera toxin exposure, activated 5-HT3 receptors upregulate enterochromaffin cell degranulation, thereby magnifying 5-HT release and so recruiting 5-HT dependent secretory pathways. Conversely, this implies that stabilization of enterochromafin cells and the prevention of degranulation may limit the severity of cholera.

The importance of the 5-HT3 receptor in cholera toxin-induced secretion, has been demonstrated both in animal and human models (Beubler & Horina, 1990; Mourad et al., 1995; Turvill & Farthing, 1997). Until now, it has been assumed that it bridges the gap between enterochromafin cell 5-HT release and the activation of the enteric nervous system. However, Gershon et al. (1990) have suggested that the 5-HT1P receptor performs this role (Jiang et al., 1993; Kirchgessner et al., 1992). The above modulation of 5-HT release provides an alternative mechanism of action for the 5-HT3 receptor that may complement the observations of Gershon et al. (1990).

In conclusion pre-treatment with granisetron directly prevents 5-HT release into the small intestinal lumen and so attenuates the 5-HT dependent secretory pathways that would otherwise be activated. These observations support the value of the control of enterochromaffin cell degranulation in the control of cholera.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the receipt of an educational grant from SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals.

Abbreviations

- CT

cholera toxin

- gra

granisetron

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- lido

lidocaine

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

References

- BARNES J.M., BARNES N.M., COSTALL B., NAYLOR R.J., TATTERSALL F.D. Reserpine, para-chlorophenylalanine and fenfluramine antagonise cisplatin-induced emesis in the ferret. Neuropharmacology. 1988;27:783–790. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(88)90092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEARCROFT C.P., FARTHING M.J.G., PERRETT D. Determination of 5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid and tryptophan in plasma and urine by HPLC with fluorimetric detection. Biomed. Chromatogr. 1995;9:23–27. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1130090105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEUBLER E., HORINA G. 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptor subtypes mediate cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:83–89. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91233-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEUBLER E., KOLLAR G., SARIA A., BUKHAVE K., RASK-MADSEN J. Involvement of 5-hydroxytryptamine, prostaglandin E2, and cyclic adenosine monophosphate in cholera toxin-induced fluid secretion in the small intestine of the rat in vivo. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:368–376. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)91560-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEUBLER E., SCHIRGI-DEGEN A., GAMSE R. Inhibition of 5-hydroxytryptamine- and enterotoxin-induced fluid secretion by 5-HT receptor antagonists in the rat jejunum. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;248:157–162. doi: 10.1016/0926-6917(93)90038-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DONOWITZ M., CHARNEY A.N., HEFFERNAN J.M. Effect of serotonin on intestinal transport in the in vivo rabbit small intestine. Am. J. Physiol. 1977;232:E85–E94. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1977.232.1.E85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERSPAMER V. Occurrence of indolealkyl amines in nature Handbuch der experimentellen Pharmakologie 1966Berlin: Springer; 132–181.Vol 19. eds. Eichler, O. & Farah, A. pp [Google Scholar]

- GEBAUER A., MERGER M., KILBINGER H. Modulation by 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors of the release of 5-hydroxytryptamine from the guinea-pig small intestine. Naunyn Schmied. Arch. Pharmacol. 1993;347:137–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00169258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERSHON M.D., TAMIR H. Release of endogenous 5-hydroxytryptamine from resting and stimulated enteric neurons. Neuroscience. 1981;6:2277–2286. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(81)90017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERSHON M.D., WADE P.R., KIRCHGESSNER A.L., TAMIR H. 5-HT receptor subtypes outside the central nervous system. Roles in the physiology of the gut. [Review] Neuropsychopharmacology. 1990;3:385–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANSEN M.B., JAFFE B.M. 5-HT receptor subtypes involved in luminal serotonin-induced secretion in rat intestine in vivo. J. Surg. Res. 1994;56:277–287. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIANG M., KIRCHGESSNER A., GERSHON M.D., SURPRENANT A. Cholera toxin-sensitive neurons in guinea-pig submucosal plexus. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:G86–G94. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.264.1.G86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JODAL M. Neuronal influence on intestinal transport. J. Inter. Med. 1990;228:125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1990.tb01484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRCHGESSNER A.L., TAMIR H., GERSHON M.D. Identification and stimulation by serotonin of intrinsic sensory neurons of the submucosal plexus of the guinea-pig gut: activity-induced expression of FOS immunoreactivity. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:235–248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-01-00235.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KISLOFF B., MOORE E.W. Effect of serotonin on water and electrolyte transport in the in vivo rabbit small intestine. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:1033–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUNDBERG J.M., DAHLSTROM A., BYLOCK A., AHLMAN H., PETTERSSON G., LARSSON I., HANSSON H.A., KEWENTER J. Ultrastructural evidence for an innervation of epithelial enterochromaffin cell in the guinea-pig duodenum. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1978;104:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1978.tb06245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOURAD F.H., O'DONNELL L.J., DIAS J.A., OGUTU E., ANDRE E.A., TURVILL J.L., FARTHING M.J.G. Role of 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptors in rat intestinal fluid and electrolyte secretion induced by cholera and Escherichia coli enterotoxins. Gut. 1995;37:340–345. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NILSSON O., CASSUTO J., LARSSON P.A., JODAL M., LIDBERG P., AHLMAN H.D., LUNDGREN O. 5-Hydroxytryptamine and cholera secretion: a histochemical and physiological study in cats. Gut. 1983;24:542–548. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.6.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETTERSSON G., DAHLSTROM A., LARSSON I., LUNDBERG I., AHLMAN H., KEWENTER J. The release of serotonin from rat duodenal enterochromaffin cells by adrenoceptor agonists studied in vitro. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1978;103:219–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1978.tb06209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RACKE K., SCHWORER H. Regulation of serotonin release from the intestinal mucosa. Pharmacol. Res. 1991;21:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(05)80101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RACKE K., SCHWORER H. Nicotinic and muscarinic modulation of 5-hydoxytryptamine (5-HT) release from porcine and canine small intestine. Clin. Invest. 1992;70:190–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00184650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICHARDSON B.P., ENGEL G. The pharmacology and function of 5-HT3 receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1986;9:424–428. [Google Scholar]

- ROLSTON D.D.K., BORODO M.M., KELLY M.J., DAWSON A.M., FARTHING M.J.G. Efficacy of oral rehydration solutions in a rat model of secretory diarrhoea. J. Paed. Gastroent. Nutr. 1987;6:624–630. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198707000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TURVILL J.L., FARTHING M.J.G. Effect of granisetron on cholera toxin-induced enteric secretion. Lancet. 1997;349:1293. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)24018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TURVILL J.L., MOURAD F.H., FARTHING M.J.G. Crucial role for 5-HT in cholera toxin but not E.coli heat labile induced secretion in rat. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:883–890. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIALLI M. Histology of enterochromaffin cell system Handbuch der experimentallen Pharmakologie 1966Berlin: Springer; 1–65.Vol 19, eds. Eichler, O. & Farah, A. pp [Google Scholar]