Abstract

The role of different residues of the rat AT1A receptor in the interaction with the N- and C-terminal ends of angiotensin II (AngII) was studied by determining ligand binding and production of inositol phosphates (IP) in COS-7 cells transiently expressing the following AT1A mutants: T88H, Y92H, G196I, G196W and D278E.

G196W and G196I retained significant binding and IP-production properties, indicating that bulky substituents in position 196 did not affect the interaction of AngII's C-terminal carboxyl with Lys199 located three residues below.

Although the T88A mutation did not affect binding, the T88H mutant had greatly decreased affinity for AngII, suggesting that substitution of Thr88 by His might hinder binding through an indirect effect.

The Y92H mutation caused loss of affinity for AngII that was much less pronounced than that reported for Y92A, indicating that His in that position can fulfil part of the requirements for binding.

Replacing Asp278 by Glu caused a much smaller reduction in affinity than replacing it by Ala, indicating the importance of Asp's β-carboxyl group for AngII binding.

Mutations in residues Thr88, Tyr92 and Asp278 greatly reduced affinity for AngII but not for Sar1 Leu8-AngII, suggesting unfavourable interactions between these residues and AngII's aspartic acid side-chain or N-terminal amino group, which might account for the proposed role of the N-terminal amino group of AngII in the agonist-induced desensitization (tachyphylaxis) of smooth muscles.

Keywords: Angiotensin II, AT1 receptor, G-protein, site-directed mutagenesis

Introduction

Angiotensin II (AngII) receptors have been cloned from several species, including rat (Murphy et al., 1991). According to their selectivity for antagonists, two AngII receptor subtypes are distinguished: AT1 (including isoforms AT1A and AT1B), and AT2; AT1 being responsible for the most important actions of AngII (Timmermans et al., 1993).

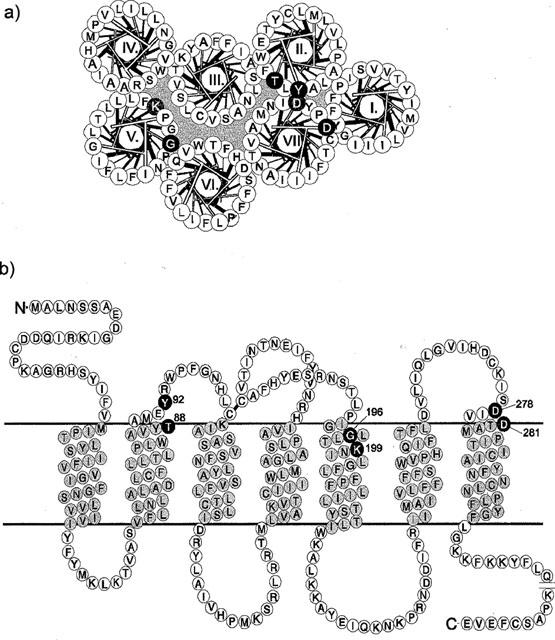

The AT1 receptor belongs to the rhodopsin-like G-protein-coupled receptor family (GPCR) and has the characteristic seven transmembrane domain structure typical of such proteins (Figure 1). Binding of the peptide agonist involves residues situated in the extracellular domain of the receptor, mainly in the N-terminal domain and in the first and third extracellular loops (Hjorth et al., 1994; Feng et al., 1995), whereas residues located in the transmembrane region and intracelluar loops are associated with the triggering of the response (Bihoreau et al., 1993; Marie et al., 1994; Han et al., 1998) and G-protein activation (Oliveira et al., 1994; Scheer et al., 1996; Fanelli et al., 1998; Perlman et al., 1997).

Figure 1.

Helical wheel (a) and serpentine diagram (b) of the rat AT1 receptor, indicating the putative transmembrane segments TM-I to TM-VII. The helical wheel scheme shows a top view of the helices disposed in anti-clockwise orientation, and with TM-III positioned as the central one. Residues that were analysed in this study are shown in white on black. Lys199 and Asp281, discussed in the text, are shown in white on grey.

When Tyr92, in the first extracellular loop, was mutated to Ala, AngII binding was greatly affected, but no significant loss of affinity was observed when Thr88 and Met90, few residues below, were both changed to Ala in a combined mutation (Hjorth et al., 1994). Similar mutation of Asp residues located in the same face of a putative helical extension of the seventh transmembrane segment (TM-VII) also showed their importance for binding AngII. Asp281 was suggested to interact with the Arg2 of the peptide ligand (Feng et al., 1995), although Asp278 appears to be a more important contact point, since the mutation on that residue caused a decrease of affinity for AngII that was 50 fold that observed with the same mutation on Asp281 (Hjorth et al., 1994). It has also been proposed that Lys199, positioned a few turns deep in TM-V, may be involved in an ionic interaction with the C-terminal caboxyl of the AngII molecule (Yamano et al., 1995; Noda et al., 1995).

Most of the mutational analysis of binding sites that have been done in seven transmembrane receptors, as well as in other proteins, used the Ala scan approach (Schwartz, 1994), but in cases where this generates false negative results the use of steric hindrance mutants should be useful for addressing the importance of a region of the receptor for ligand binding (Holst et al., 1998). Therefore, we have used this approach to investigate some residues which might participate or interfere in the receptor's interactions with the C- and N-terminal ends of the AngII molecule. To explore the possible interaction between the C-terminal carboxyl of AngII and the Lys199 side-chain, Gly196 (positioned three residues above on an helical turn) was mutated to Ile and to Trp, two hydrophobic and bulky residues that might cause a steric hindrance effect. In the region proposed to be involved in the interaction with AngII's N-terminus, we have mutated either Thr88 or Tyr92 to His. Regarding Tyr92, the previously reported Y92A mutation dramatically affected the receptor's affinity for AngII (Hjorth et al., 1994) and mutation of this residue to His, for the same reasons described above, might provide more information on the participation of that residue in ligand binding. In the same region, but in the third extracellular loop close to TM-VII, Asp278, which was previously mutated to Ala (Hjorth et al., 1994), was now mutated to Glu, a very conservative mutation, in order to analyse the importance of an acidic side-chain of the right size in that position.

Methods

Materials

AngII and the peptide antagonist Sar1,Leu8-AngII were purchased from Peninsula Laboratories (St. Helens, Merseyside, U.K.). The non-peptide antagonist L-158,809 and the radiolabelled non-peptide antagonist 125I-L735,286 were kind gifts from Dr William J. Greenlee (Merk Research Laboratories, Rahway, NJ, U.S.A.). Monoiodinated 125I-Sar1,Leu8-AngII and 125I-AngII were prepared by the IODO-GEN method as previously described (Sheikh et al., 1989) and purified by reverse-phase HPLC using a gradient of acetonitrile ranging from 19–27%. Materials and media for cell culture were obtained from Life Technologies, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A.).

Receptor mutagenesis

The rat AT1A receptor cDNA (Murphy et al., 1991), generously provided by Dr T.J. Murphy (Emory University, Atlanta, GA, U.S.A.), was used to generate a ‘cassette' gene, as previously described (Hjorth et al., 1994). Mutations were introduced by the PCR overlap extension technique (Horton et al., 1989). The PCR fragments were digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes and subsequently inserted into the likewise digested expression vector pTEJ8 (Johansen et al., 1990). Pfu polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.) was used for the PCR reactions under conditions recommended by the manufacturer. Temperature cycling consisted of 30–35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 45–50°C 1 min, 72°C 1 min. All receptor constructs were initially identified by the presence of a diagnostic restriction site, and subsequently verified by sequencing.

Cell culture and transfections

Expression plasmids containing wild type or mutated AT1 receptors were transiently transfected into COS-7 cells by a calcium phosphate precipitation method as described before (Gether et al., 1993).

Inositol phosphate (IP) turnover

0.3–0.4×106 cells expressing the wild type rat AT1 receptor or mutants were cultivated for 24 h in inositol-free medium (1885 Dulbecco with NaH2CO3 supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine and 0.1 mg ml−1 gentamicin) in 6- or 12-well plates, each well containing 5 μCi 3H-myoinositol (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, U.K.). The cells were washed twice with buffer (in mM): HEPES 20, NaCl 140, MgSO4 10, CaCl2 1, glucose 10, pH 7.4, and subsequently incubated for 5 min with the same buffer including 10 mM LiCl. AngII dose-response experiments were performed with 1-h incubation time. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 0.5 ml 10% perchloric acid and the precipitated cellular proteins were removed by centrifugation. The supernatants were collected and neutralized with 200 μl of a buffer solution (4.8 M KOH, 67.5 M HEPES) and incubated for 30 min with 2 ml of water and 0.5 ml of AG1-X8 anion-exchanger resin (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, U.S.A.) (Berridge et al., 1983). The resin was washed three times with 5 mM myoinositol and the 3H-inositol phosphates were eluted by adding 1 ml of 1.0 M ammonium formate in 0.1 M formic acid. The data were analysed by nonlinear regression analysis using INPLOT 4.0 (Graph-Pad Software, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.).

Whole cell binding experiments

Receptor binding assays were performed on whole COS-7 cells 48 h after transfection. Cells transfected with receptor expression plasmids were transferred to 12- or 24-well culture plates 24 h after transfection aiming at 0.2–1.5×105 cells per well, depending on the expression level of the plasmid used. Twenty-four hours following plating of the transfected cells, and immediately before the binding experiment, the cells were washed briefly in 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 and 0.1% bovine serum albumin. Binding experiments were performed at 4°C and initiated by the addition of 50 pM 125I-L735,286, or 125I-Sar1-Leu8-AngII, or 125I-AngII in the presence of varying amounts of unlabelled peptide or non-peptide ligand as a competitor in a 0.5–1.0 ml assay volume. The binding buffer consisted of 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, including 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, and 100 μg ml−1 bacitracin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). All measurements were done in triplicate, and the data were analysed by nonlinear regression analysis using INPLOT 4.0 (Graph-Pad Software, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.).

Results and discussion

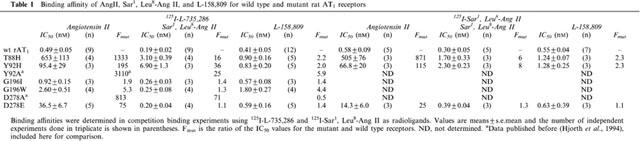

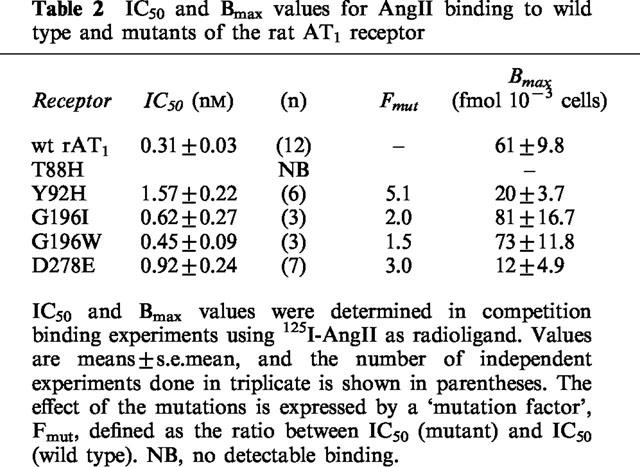

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the effects of the mutations on the AT1 receptor as determined by competition binding experiments using either the non-peptide compound 125I-L-735,286 or 125I-AngII (homologous competition) as radioligands. 125I-L-735,286 was used more extensively as radioligand because the mutations studied were located in regions supposedly involved in interactions with the natural peptide ligand AngII, and it is known that peptide and non-peptide ligands bind to different sites in the receptor. The mutants that presented greater loss of affinity for 125I-L-735,286 (F(mut)>10) were also tested in competition assays with the peptide antagonist 125I-Sar1,Leu8-AngII. Table 1 shows that the mutations that affected AngII binding did not significantly reduce the receptor's affinity for the non-peptide antagonist L-158,809. However, the sole use of a non-peptide as a radioligand might lead to an overestimation of the observed loss of affinity in some of the mutants studied. For that reason, we also used two other radioligands: the peptide antagonist 125I-Sar1,Leu8-AngII (Table 1) and the peptide agonist 125I-AngII (used for Bmax calculation, Table 2).

Table 1.

Binding affinity of AngII, Sar1, Leu8-Ang II, and L-158,809 for wild type and mutant rat AT1 receptors

Table 2.

IC50 and Bmax values for AngII binding to wild type and mutants of the rat AT1 receptor

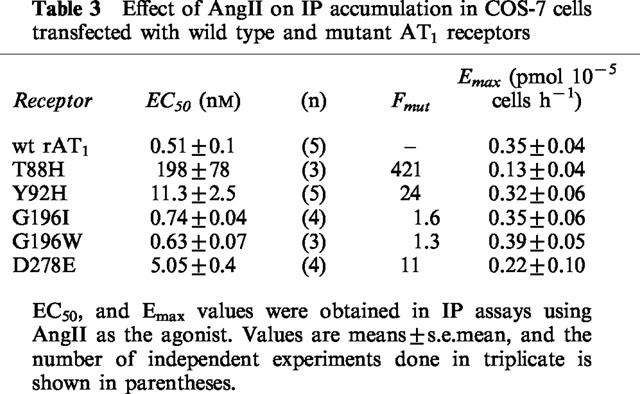

The functional state of the mutants was assessed by the inositol phosphate accumulation in response to AngII and the results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Effect of AngII on IP accumulation in COS-7 cells transfected with wild type and mutant AT1 receptors

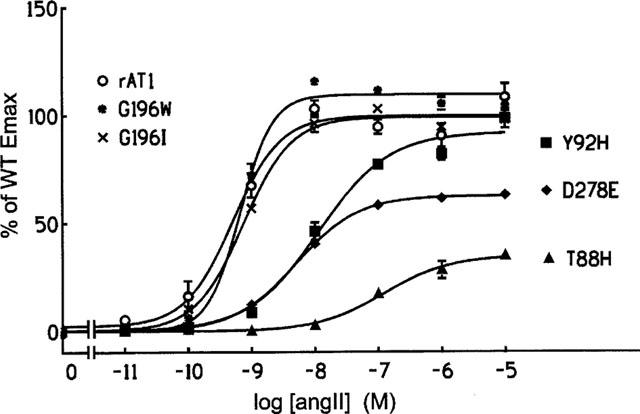

Gly196

In spite of the potential steric consequences on Lys199, replacing Gly196 residue by Ile or by Trp affected very little the receptor's affinity for AngII as determined by competition experiments using 125I-L-735,286 as radioligand (Table 1). The wild type receptor and the G1961 or G196 W mutants presented similar IC50 values for binding AngII and Sar1,Leu8-AngII, as well as the non-peptide antagonist L-158,809. Homologous competition binding experiments using 125I-AngII as radioligand were also performed (Table 2), and the Bmax values found for G1961 and for G196 W were similar to those obtained for the wild type receptor. The results of the IP accumulation assays are shown in Figure 2. No significant differences were also found between the EC50 and Emax values obtained for the two mutants and for the wild type receptor (Table 3). These unexpected results might be due to one of the following situations: (a) Gly196 is not on a transmembrane region, i.e. its position is not constrained above Lys199; (b) the two residues are in a transmembrane region, but the Lys199 side-chain could be pointing toward the extracellular surface of the receptor, in a snorkel effect, allowing AngII's C-terminal end to interact without having to penetrate the transmembrane domain of the receptor; (c) the receptor pocket formed on the interfaces of TM-III, TM-V, and TM-VII may have a higher degree of freedom, allowing the peptide's C-terminus to reach the Lys199 side-chain even in the presence of the bulky substituents introduced in the G1961 and G196W mutants.

Figure 2.

Concentration-response curves for the effect of AngII on IP turnover in transiently transfected COS-7 cells expressing wild type and mutant AT1 receptors. The phosphatidylinositol turnover is expressed as a percentage of the Emax values obtained for the wild type receptor.

Thr88

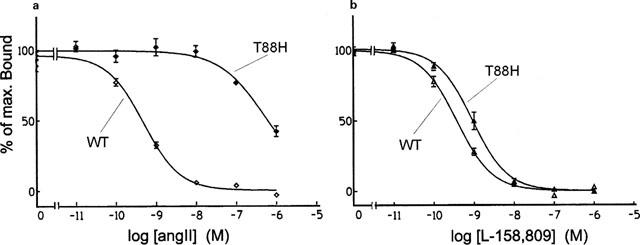

As expected if Thr88 were in fact located in an important region, the T88H mutation decreased the affinity constant for AngII by more than 1000 fold (Figure 3a). The affinity for Sar1, Leu8-AngII and for L-158,809 was much less affected, as illustrated in Figure 3b for the case of L-158,809. Table 1 shows that the loss of affinity of the T88H mutant for Sar1, Leu8-AngII and L-158,809 ranged from 2.2–16 fold when either 125I-L-735,286 or 125I-Sar1, Leu8-AngII was used as the radioligand. As a result of its very low affinity for AngII the mutant T88H was not able to bind 125I–AngII, and therefore no Bmax value could be obtained to be included in Table 2. Nevertheless, this mutant was still able to stimulate IP turnover, although with very high EC50 and low Emax values (Figure 2 and Table 3).

Figure 3.

Competition binding profiles for AngII (a) and for the non-peptide antagonist L-159,809 (b) in cells transfected with the wild type (WT) and with the T88H mutant of the rat AT1 receptor. Data are expressed as percentages of the maximum specific binding of the radioligand 125I-L-735,286 (mean±s.e.mean, n=4–12).

Since replacement of Thr88 by alanine did not affect the binding of AngII (Hjorth et al., 1994), it is conceivable that substitution by His might hinder AngII binding through an indirect effect. Histidine is an amino acid that displays both hydrophobic and polar characteristics, with a partial positive charge at neutral pH. A mutation of Thr88 to His might affect AngII binding through an ionic interaction with acidic residues (such as Asp278 or Asp281) supposed to be directly involved in AngII's binding, or by disrupting a cluster of residues involved on the formation of a binding site such as Tyr92, Asp278 or Asp281 (Hjorth et al., 1994; Feng et al., 1995).

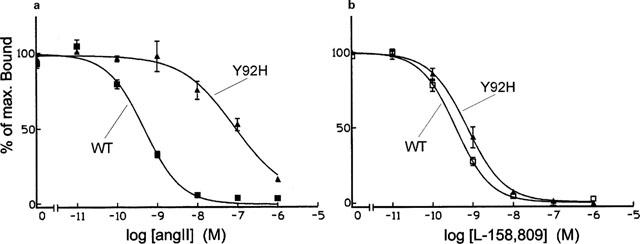

Tyr92

Previous mutation of this residue to Ala (Hjorth et al., 1994) caused a very large loss of affinity for AngII in competition binding experiments using the non-peptide antagonist 125I-L-735,286 as radioligand. In the case of the Y92H mutant, when 125I-L-735,286 or 125I-Sar1,Leu8-AngII were used as radioligands (Table 1), the affinity for AngII was greatly decreased with regard to that of the wild type receptor (Figure 4a), but not as much as occurred with the Y92A mutant. Also similarly to what was observed when Tyr92 was replaced by Ala, the affinity of the Y92H mutant for the antagonists Sar1, Leu8-AngII and L-158,809 (Figure 4b) was not much affected as compared to that of the wild type receptor. In homologous binding experiments using 125I-AngII as the radioligand, only a 5.1 fold reduction in the affinity for AngII was observed, while the calculated Bmax value was significantly lower than that found for the wild type receptor (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Competition binding profiles for AngII (a) and for the non-peptide antagonist L-159,809 (b) in cells transfected with the wild type (WT) and with the Y92H mutant of the rat AT1 receptor. Data are expressed as percentages of the maximum specific binding of the radioligand 125I-L-735,286 (mean±s.e. mean, n=4–12).

Regarding the IP accumulation response (Figure 2 and Table 3), AngII stimulated the Y92H mutant with an EC50 value 24 times higher than that of the wild type receptor. The Emax value, however was not different from that obtained for the wild type receptor. Therefore, His at position 92 still retains some of the contribution of the Tyr residue for ligand binding by AT1. The imidazole and phenolic moieties present in the His and Tyr side-chains, respectively, have some characteristics not present in Ala, such as their aromatic character, their partly hydrophobic partly polar properties, their ability as hydrogen bond makers, as well as their bulk. Which of these characteristics might be important for the role of Tyr92 in AT1 ligand binding is not possible to say with the present results.

Asp278

Using 125I-L-735,286 as the radioligand, the binding constant of the D278E mutant for AngII was decreased 75 fold, but that for Sar1,Leu8-AngII was basically not affected (Table 1). When 125I-AngII was used as the radioligand, the competition binding assay revealed little change in the affinity of D278E for AngII, but the Bmax value obtained was significantly decreased (Table 2). In cells transfected with this mutant, the dose response-curve for the effect of AngII on IP accumulation was shifted to the right, with a 10 fold increase in the EC50 value, and Emax was decreased as compared to the wild type (Figure 2 and Table 3). This indicates that the carboxyl group of the side-chain, also present in Glu, is mostly responsible for the contribution of Asp278 to the affinity of AT1 for AngII. Yet, it shows the important participation of Asp278 in the interaction with AngII, since in the D278E mutant a single amino acid residue in the entire receptor molecule had its side-chain modified with the ‘insertion' of an extra methylene group.

It is interesting to note that the loss of AngII binding observed in mutants T88H, Y92H and D278E was not accompanied by a similar loss of affinity for the peptide analogue Sar1, Leu8-AngII. This suggests that mutations in those residues might allow interactions between receptor and ligand that would be unfavourable to the binding of AngII, but not to that of Sar1,Leu8-AngII. This unfavourable interaction would involve either the aspartic acid side-chain or the primary N-terminal amino group of AngII, which are absent in Sar1,Leu8-AngII, and might account for the proposed role of the N-terminal amino group of AngII in the agonist-induced desensitization (tachyphylaxis) observed in smooth muscle (Oshiro et al., 1989).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the São Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP), the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq), the Danish Medical Research Council and the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Abbreviations

- AngII

angiotensin II

- AT1 and AT2

angiotensin type 1 and type 2 receptors

- IP

inositol phosphates

- TM

transmembrane segment

References

- BERRIDGE M.J., DAWSON M.C., DOWNES C.P., HESLOP J.P., IRVINE R.F. Changes in the level of inositol phosphates after agonist-dependent hydrolysis of membrane phosphoinositides. Biochem. J. 1983;212:473–482. doi: 10.1042/bj2120473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIHOREAU C., MONNOT C., DAVIES E., TEUTSCH B., BERNSTEIN K.E., CORVOL P., CLAUSER E. Mutation of Asp74 of the rat angiotensin II receptor confers changes in antagonist affinities and abolishes G-protein coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:5133–5137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FANELLI F., MENZIANI C., SCHEER A., COTECCHIA S., DE BENEDETTI P.G. Ab initio modeling and molecular dynamics simulation of the alpha 1b-adrenergic receptor activation. Methods. 1998;14:302–317. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FENG Y., NODA K., SAAD Y., LIU X., HUSAIN A., KARNIK S.S. The docking of Arg2 of angiotensin II with Asp281 of AT1 receptor is essential for full agonism. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;170:12846–12850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GETHER U., JOHANSEN T.E., SCHWARTZ T.W. Chimeric NK1 (substance P)/NK3 (neurokinin B) receptors - Identification of domains determining the binding specificity of tachykinin. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:7893–7898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAN H.M.C.B., SHIMUTA S.I., KANASHIRO C.A., OLIVEIRA L., HAN S.W., PAIVA A.C.M. Residues Val254, His256, and Phe259 of the angiotensin II AT1 receptor are not involved in ligand binding but participate in signal transduction. Mol. Endocrinol. 1998;12:810–814. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.6.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HJORTH A.S., SCHAMBYE H.T., GREENLEE W.J., SCHWARTZ T.W. Identification of peptide binding residues in the extracellular domains of the AT1 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:30953–30959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLST B., ZOFFMANN S., ELLING C.E., HJORTH S.A., SCHWARTZ T.W. Steric hindrance mutagenesis versus alanine scan in mapping of ligand binding sites in the tachykinin NK1 receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:166–175. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORTON R.M., HUNT H.D., HO S.N., PULLEN J.K., PEASE L.R. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene. 1989;77:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHANSEN T.E., SCHOLER M.S., TOLSTOY S., SCHWARTZ T.W. Biosynthesis of peptide precursors and protease inhibitors using new constitutive and inducible eukariotic expression vectors. FEBS Lett. 1990;267:289–294. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80947-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARIE J., MAIGRET B., JOSEPH M., LARGUIER R., NOUET S., LOMBARD C., BONNAFOUS J. Tyr292 in the seventh transmembrane domain of the AT1a angiotensin II receptor is essential for its coupling to phospholipase C. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:20815–20818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURPHY T.J., ALEXANDER R.W., GRIENDLING K.K., RUNGE M.S., BERNSTEIN K.E. Isolation of a cDNA encoding the vascular type-1 angiotensin II receptor. Nature. 1991;351:233–336. doi: 10.1038/351233a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NODA K., SAAD Y., KARNIK S.S. Interaction of Phe8 of angiotensin II with Lys199 and His256 of AT1 receptor in agonist activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:28511–28514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLIVEIRA L., PAIVA A.C.M., SANDER C., VRIEND G. A common step for signal transduction in G protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1994;15:170–172. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSHIRO M.E.M., SHIMUTA S.I., PAIVA T.B., PAIVA A.C.M. Evidence for a regulatory site in the angiotensin II receptor of smooth muscle. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;166:411–417. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERLMAN S., COSTA-NETO C.M., MIYAKAWA A.A., SCHAMBYE H.T., HJORTH A.S., PAIVA A.C.M., RIVERO R.A., GREENLEE W.J., SCHWARTZ T.W. Dual agonistic and antagonistic property of non-peptide angiotensin AT1 ligands - Susceptibility to receptor mutagenesis. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;51:301–311. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHEER A., FANELLI F., COSTA T., DE BENEDETTI P.G., COTECCHIA S. Constitutively active mutants of the alfa 1B-adrenergic receptor: role of highly conserved polar amino acids in receptor activation. EMBO J. 1996;15:3566–3578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWARTZ T.W. Locating ligand-binding sites in 7TM receptors by protein engineering. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 1994;5:434–444. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEIKH S.P., O'HARE M.M.T., TORTORA O., SCHWARTZ T.W. Binding of monoiodinated neuropeptide Y to hippocampal membranes and human neuroblstoma cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:6648–6654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIMMERMANS P.B.M.W.M., WONG P.G., CHIN A.T., HERBLIN W.F., BENFIELD P., CARINI D.J., LEE R.J., WEXLER R.R., SAYE J.A.M., SMITH R.M. Angiotensin II receptors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Pharmacol. Ver. 1993;45:205–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMANO Y., OHYAMA K., KIKYO M., SANO T., NAKAGOMI Y., INOUE Y., NAKAMURA N., MORISHIMA I., GUO D.-F., HAMAKUBO T., INAGAMI T. Mutagenesis and the molecular modeling of the rat angiotensin II receptor (AT1) J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:14024–14030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.14024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]