Abstract

We investigated the mechanism by which human interferon-α (IFN-α) increases the immobility time in a forced swimming test, an animal model of depression.

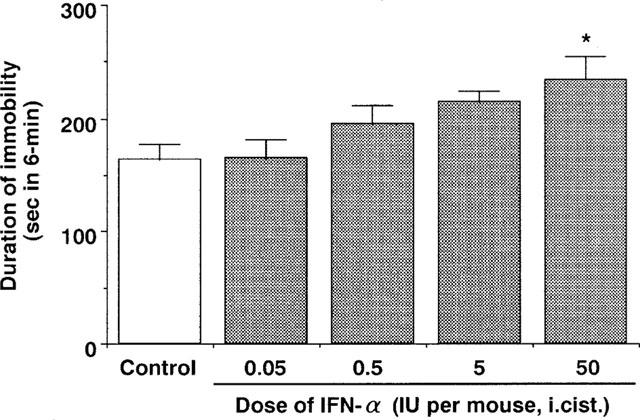

Central administration of IFN-α (0.05–50 IU per mouse, i.cist.) increased the immobility time in the forced swimming test in mice in a dose-dependent manner.

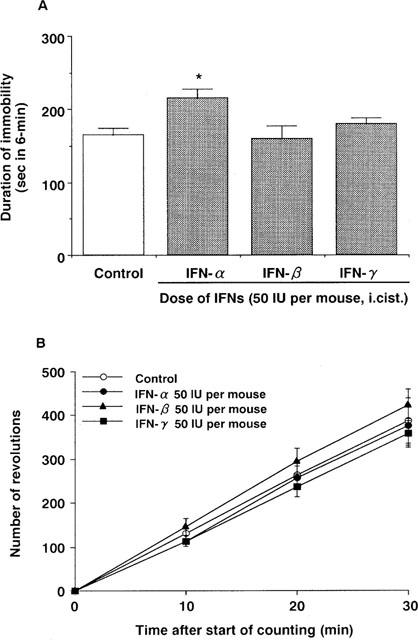

Neither IFN-β nor -γ possessed any effect under the same experimental conditions.

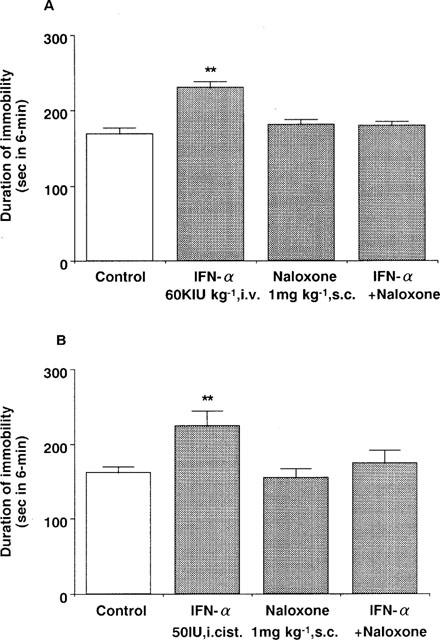

Pre-treatment with an opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone (1 mg kg−1, s.c.) inhibited the prolonged immobility time induced by IFN-α (60 KIU kg−1, i.v. or 50 IU per mouse. i.cist.).

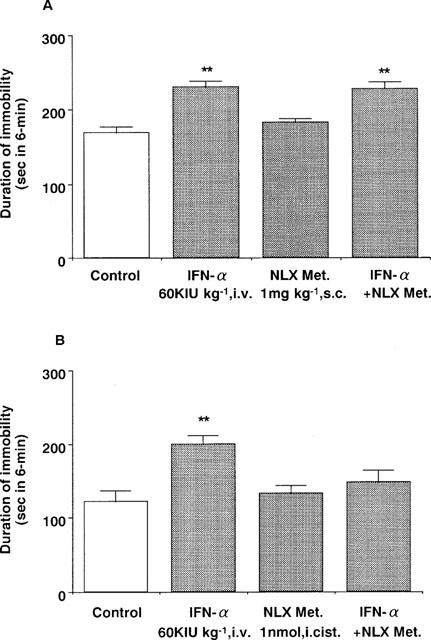

Peripheral administration of naloxone methiodide (1 mg kg−1, s.c.), which does not pass the blood–brain barrier, failed to block the effect of IFN-α, while intracisternal administration of naloxone methiodide (1 nmol per mouse) completely blocked.

The effect of IFN-α was inhibited by a μ1-specific opioid receptor antagonist, naloxonazine (35 mg kg−1, s.c.) and a μ1/μ2 receptor antagonist, β-FNA (40 mg kg−1, s.c.). A selective δ-opioid receptor antagonist, naltrindole (3 mg kg−1, s.c.) and a κ-opioid receptor antagonist, nor-binaltorphimine (20 mg kg−1, s.c.), both failed to inhibit the increasing effect of IFN-α.

These results suggest that the activator of the central opioid receptors of the μ1-subtype might be related to the prolonged immobility time of IFN-α, but δ and κ-opioid receptors most likely are not involved.

Keywords: Interferon, depression, forced swimming test, opioid receptor

Introduction

Interferons (IFNs) are multifunctional cytokines and components of host defence against viral and parasitic infections and certain tumours. There appear to be three major classes of human IFNs: α, β and γ. These IFNs produced by infected cells prevent the multiplication of viruses and also induce immune-mediated clearance of viruses (Gisslinger et al., 1993; Pestka et al., 1987; Sen & Lengyel 1992). Thus, IFN therapy is useful in the management of a variety of chronic viral infections and malignant diseases (Dianzani et al., 1990; Steinmann et al., 1993).

In therapeutic usage of IFNs, central nervous system (CNS), respiratory and cardiovascular system, renal function, and autoimmune side effects have been observed (Quesada et al., 1986; Vial & Descotes 1994). Recently, the frequency of CNS side effects of IFNs, including drowsiness, sensory hypersensitivity, motility disorder, hallucinations and depression, has increased markedly (Adams et al., 1988; Merimsky et al., 1990; Meyers et al., 1991; Rohatiner et al., 1983; Smedley et al., 1983). Interestingly, the incidence of CNS side effects, in particular that of psychosis with IFN-α appears to be higher than that with IFN-β and IFN-γ (Bocci, 1988; 1994; Takagi 1995; Vial & Descotes, 1994), but the mechanisms by which IFNs induce CNS side effects are not well understood.

Depression is a serious CNS side effect which sometimes results in patient suicide during interferon therapy (Prasad et al., 1992; Renault et al., 1987). Our previous studies have shown that human IFN-α but not human IFN-β or -γ, increased the immobility time in the mouse and rat forced swimming test, which is regarded as a model of depression (Porsolt et al., 1977; 1978), suggesting that human IFN-α has a greater potential for inducing depression than human IFN-β and -γ (Makino et al., 1998; 2000).

In clinical trials, most patients with psychosis during IFN-therapy reveal electroencephalogram (EEG) changes including a slowing of the dominant α-rhythms and the occasional appearance of diffuse δ- or intermittent θ-activity has been reported (Mattson et al., 1983; Rohatiner et al., 1983; Suter et al., 1984). In animal studies, human IFN-α enhanced EEG slow-wave activity in rabbits (Krueger et al., 1987), and the modified cortical EEG activity and increased EEG synchronization induced by human IFN-α in rats were reversed by naloxone, an opioid antagonist (Birmanns et al., 1990). Furthermore, human IFN-α but not IFN-β or -γ, exerts opioid-like effects in the CNS, and similarities have been demonstrated among the structures of IFN-α proopiomelanocortin. ACTH and β-endorphin (Blalock & Smith 1980; 1981; Jornvall et al., 1982). In support of this suggestion, human IFN-α has been shown to bind to rat brain tissue membranes (Janicki 1992) and it inhibits the binding of naloxone to rat brain membranes (Menzies et al., 1992). These clinical and animal model observations suggest that opioid systems likely play a key role in the CNS side effects induced by IFN-α and the possibility exists that human IFN-α induced depression might be mediated by central or peripheral opioid systems.

In the present study, we used the mouse forced swimming test to evaluate whether the immobility induced by human IFN-α might be due to a central or peripheral action and whether human IFN-α induced depression is mediated by central or peripheral opioid receptors. Furthermore, we evaluated the type of opioid receptors involved in the increase in the immobility induced by human IFN-α.

Methods

Animals

Male Slc: ddY mice (Japan SLC, Hamamatsu, Japan), weighing 22∼30 g were used. The mice were housed in an animal room under the following conditions: room temperature. 23±2°C: relative humidity, 55±20% with a 12 h/12 h light-dark cycle (lights on at 0800 h). Each mouse was fed a mouse/rat diet (F-2, pellet form. Funabashi Farm, Funabashi, Japan), and allowed tap water ad libitum. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with in-house guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Drugs and treatments

The following drugs were used: IFN-α (recombinant human IFN-α-2b: Intron A®, Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical–Schering Plough, Tokyo, Japan), IFN-β (human fibroblast IFN-β: Feron®. Daiichi Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), IFN-γ (recombinant human IFN-γ-la: Imunomax-γ®. Shionogi Pharmaceutical. Osaka, Japan), naloxone hydrochloride (SIGMA, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), naloxone methiodide (RBI, Natick, MA, U.S.A.), naloxonazine (RBI), β-funaltrexamine hydrochloride (β-FNA, RBI), naltrindole hydrochloride (RBI), nor-binaltorphimine dihydrochloride (nor-BNI, RBI). The drugs were dissolved in 0.9% physiological saline (Fuso Yakuhin Kogyo, Osaka, Japan), except for naloxonazine, β-FNA and naltrindole which were dissolved in 0.1 N hydrochloride (Kishida Chemical, Osaka, Japan) and then diluted in 0.9% physiological saline.

Forced swimming test

The procedure previously reported was used (Makino et al., 1998). Briefly, mice were forced to swim for 6 min inside a vertical acrylic cylinder (height, 25 cm; diameter, 12 cm) containing water about 15 cm deep at 20°C. The total duration of immobility time during the 6 min was measured. During the swimming exposure, the mouse was judged to be immobile whenever it remained floating motionless except for movement necessary to keep its head out of the water. Peripheral administration of IFN-α was administered intravenously into a tail vein 15 min prior to testing. This treatment time and dose of IFN-α were selected taking into account our previous study, in which IFN-α (0.6–60 KIU kg−1, i.v.) dose-dependently increased the immobility time and the effect was peaked at 15 min after administration (Makino et al., 1998). Central administration of IFNs were administered intracisternally 5 min prior to testing. This treatment time of IFNs used was selected taking into account our preliminary study, in which the effect of IFN-α (50 IU per mouse, i.cist.) was peaked at 5 min after administration. Naloxonazine and β-FNA were administered subcutaneously 24 h prior to testing nor-BNI was administered subcutaneously 2 h prior to testing. The other opioid antagonists were administered subcutaneously 30 min prior to testing. These pre-treatment time and doses of antagonists were selected in accordance with the previous reports, in which these antagonists were adequately effective (Carr et al., 1993; Kamei et al., 1995; Paul et al., 1989; Scoto & Parenti, 1996). Animals of the control group received 0.9% physiological saline through injection sites identical to the experimental animals. Separate groups of mice were used in each study.

Locomotor activity

Mice were placed individually into a wheel cage (MIP-012, Muromachi Kikai, Tokyo, Japan). The number of rotations of the cage was measured as an index of spontaneous locomotor activity. Mice which rotated the cage over 200 times in a 30-min period were selected for the study at 24 h prior to the experiment. Mice were administered intracisternally with IFNs, and the spontaneous locomotor activity was measured 5 min after administration. The number of revolutions was recorded at 10-min intervals for a period of 30 min. Animals of the control group were administered 0.9% physiological saline and separate groups of mice were used in each study.

Statistical analysis

Data from the forced swimming test and the locomotor activity test were analysed by the one-way layout and multiple comparison method of Dunnett.

Results

Effects of IFNs in the forced swimming test and the spontaneous locomotor activity

Intracisternal administration of IFN-α (0.05–50 IU per mouse) dose-dependently increased the immobility time in the forced swimming test in mice (Figure 1). At 50 IU per mouse, this effect was statistically significant (Figures 1 and 2A). Neither IFN-β nor IFN-γ (50 IU per mouse, i.cist.) changed the immobility time (Figure 2A). At the highest concentration studied, none of IFNs (50 IU per mouse, i.cist.) changed locomotor activity (Figure 2B) and caused abnormal behaviour in mice.

Figure 1.

Effect of IFN-α on the immobility time of the forced swimming test in mice. Saline (control) or IFN-α (0.05–50 IU per mouse. i.cist.) was administered 5 min before measurement of immobility time. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean (n=10). *P<0.05 vs control group.

Figure 2.

Effects of IFNs on the immobility time of the forced swimming test (A) and locomotor activity (B) in mice. Saline (control) or IFNs (50 IU per mouse, i.cist.) were administered 5 min before measurement of immobility time and locomotor activity. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean (n=10). *P<0.05 vs control group.

Effects of naloxone and naloxone methiodide on the effect of IFN-α in the forced swimming test

Intravenous administration of IFN-α (60 KIU kg−1) also increased the immobility time. Pre-treatment with naloxone (1 mg kg−1, s.c.) blocked the effects of IFN-α administered either intravenously or intracisternally (50 IU per mouse) (Figure 3). On the other hand, naloxone methiodide (1 mg kg−1, s.c.) was ineffective, but pre-treatment with naloxone methiodide administered intracisternally (1 nmol per mouse) blocked the increasing effect of IFN-α (Figure 4). Either drug alone had no effect either the immobility time (Figures 3 and 4) or the spontaneous locomotor activity in mice (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effects of naloxone on the effect of IFN-α in the forced swimming test in mice. (A) Saline (control) or IFN-α (60 KIU kg−1, i.v.) was administered 15 min before measurement of immobility time. (B) Saline (control) or IFN-α (50 IU per mouse, i.cist.) was administered 5 min before measurement of immobility time. Naloxone (1 mg kg−1, s.c.) was administered 30 min before measurement of immobility time. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean (n=10). **P<0.01 vs control group.

Figure 4.

Effect of naloxone methiodide on the effect of intravenous administration of IFN-α in the forced swimming test in mice. Saline (control) or IFN-α (60 KIU kg−1, i.v.) was administered 15 min before measurement of immobility time. (A) Naloxone methiodide (1 mg kg−1, s.c.) was administered 30 min before measurement of immobility time. (B) Naloxone methiodide (1 nmol per mouse, i.cist.) was administered 30 min before measurement of immobility time. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean (n=10). **P<0.01 vs control group. NLX Met.: naloxone methiodide.

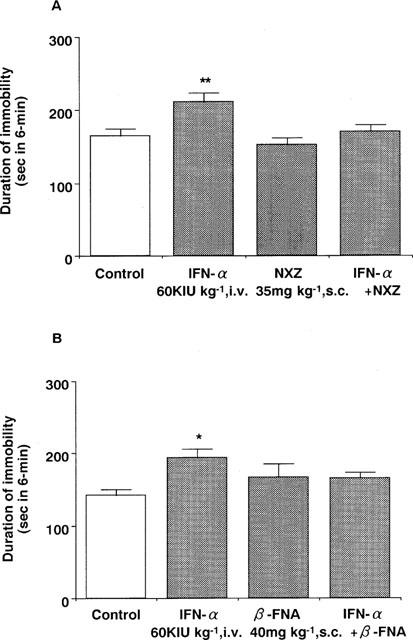

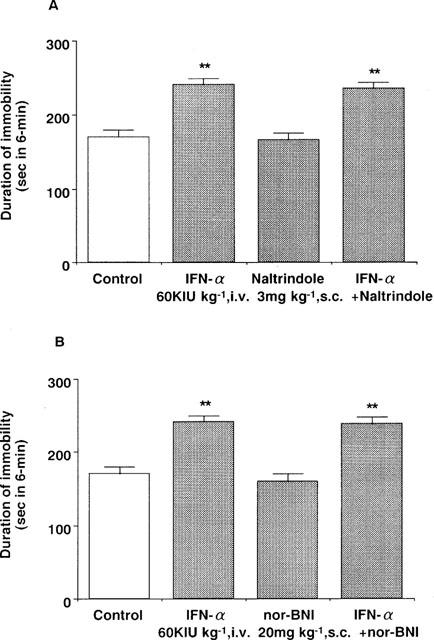

Effects of selective opioid antagonists on the effect of IFN-α in the forced swimming test

Pre-treatment with naloxonazine (35 mg kg−1, s.c.) or β-FNA (40 mg kg−1, s.c.) blocked the IFN-α (60 KIU kg−1, i.v.) induced increase in the immobility time (Figure 5). In contrast, neither naltrindole (3 mg kg−1, s.c.) nor nor-BNI (20 mg kg−1, s.c.) had any effect (Figure 6). None of the drugs administered alone changed the immobility time (Figures 5 and 6) or the spontaneous locomotor activity in mice (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effects of naloxonazine (A) and β-FNA (B) on the effect of IFN-α in the forced swimming test in mice. Saline (control) or IFN-α (60 KIU kg−1, i.v.) was administered 15 min before measurement of immobility time. Naloxonazine (35 mg kg−1, s.c.) or β-FNA (40 mg kg−1, s.c.) was administered 24 h before measurement of immobility time. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean (n=10). *P<0.05. **P<0.01 vs control group. NXZ: naloxonazine.

Figure 6.

Effects of naltrindol (A) and nor-BNI (B) on the effect of IFN-α in the forced swimming test in mice. Saline (control) or IFN-α (60 KIU kg−1, i.v.) was administered 15 min before measurement of immobility time. Naltrindol (3 mg kg−1, s.c.) or nor-BNI (20 mg kg−1, s.c.) were administered 30 min or 2 h before measurement of immobility time, respectively. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean (n=10). **P<0.01 vs control group.

Discussion

The data obtained in this study confirm our previous observations, in that human IFN-α but not human IFN-β or -γ, has the potential for inducing depression (Makino et al., 1998). The increasing effect of human IFN-α in the mouse forced swimming test was apparent following both central and peripheral administration. The penetration of IFNs into the brain from plasma is limited by its low cerebrovascular permeability and its rapid elimination from plasma (Bocci, 1994; Vial & Descotes, 1994). Despite the achievement of high plasma IFN levels after systemic administration, little or no IFN is detectable in the cerebrospinal fluid (Jordan et al., 1974; Rohatiner et al., 1983; Martino & Singhakowinta 1984). According to Wiranowska et al. (1989), however, IFNs might enter the brain at low levels through areas lacking the blood–brain barrier, such as the area postrema, median eminence and infundibular recess. Some reports concerning the pharmacokinetics of IFN in CNS indicate that the brain/plasma ratio of IFN-α intravenously administered in rats is 0.002 (Greig et al., 1988). The cerebrospinal fluid/serum ratio of IFN-α after intravenous or intramuscular administration in monkeys is 0.03 (Habif et al., 1975), and the ratio for IFN-α after intravenous administration in humans ranged from 1/550 to 1/1100 (Smith et al., 1985). These reports also suggest that the brain levels of IFN-α are very low, <20 IU ml−1 of the cerebrospinal fluid level in animals. In the current study, central administration of IFN-α (50 IU per mouse, i.cist.) significantly increased the immobility in the mouse forced swimming test, consistent with our previous studies with IFN-α (60 KIU kg−1, i.v.). Although we did not measure the brain IFN-α levels after peripheral administration, it is likely that the very low levels of IFNs entering the brain are enough to increase the immobility in the mouse forced swimming test. In contrast to IFN-α, neither IFN-β nor -γ increased the immobility time in the forced swimming test even after central administration, suggesting that IFN-β and -γ have less ability to act in CNS than IFN-α.

It is unlikely that the increasing effect of IFN-α in the forced swimming test following both central and peripheral administration was due to motor dysfunction, such as decreased locomotor activity and ataxia, since IFN-α did not affect the locomotor activity of mice under the same treatment regimen and conditions as those used for the forced swimming test, consistent with our previous study with peripheral administration of IFN-α (Makino et al., 1998).

Electrophysiological and other studies have indicated that human IFN-α acts upon opioid receptors (Birmanns et al., 1990; Blalock & Smith 1981; Dafny et al., 1988; Dafny, 1998; De Sarro et al., 1990; Saphier et al., 1993), and this viewpoint is substantiated by the ability of IFN-α, but not IFN-β or -γ, to inhibit the binding of naloxone to brain membrane of rats and mice (Blalock & Smith 1981; Menzies 1992). In the present study, central and peripheral administration of human IFN-α induced an increase in the forced swimming test and this effect was blocked by naloxone, an opioid receptor antagonist, supporting the hypothesis that opioid systems play a key role in the effect of IFN-α in this test. Since opioid receptors are found to be widely expressed in the CNS region and several peripheral tissues of the body (Mansour et al., 1995; Wittert et al., 1996), either one or both sites might be related to the increasing effect of IFN-α. In this study, naloxone methiodide administered peripherally, which does not pass the blood–brain barrier, failed to block the effect of human IFN-α, but intracisternal administration of naloxone methiodide com-pletely blocked the effect. These results suggest that the increase in the immobility induced by human IFN-α in the forced swimming test could be mediated by the central opioid receptors, rather than receptors expressed in tissues.

Based on pharmacological studies, at least three classes of opioid receptors have been defined and are known as μ, δ and κ receptors (Reisine & Bell, 1993). These receptors are known to be widely distributed in the CNS (Mansour et al., 1995). To determine the role of centrally located μ, δ and κ opioid receptors in the immobility increased by human IFN-α we evaluated the effects of their specific receptor antagonists. The increasing effect of human IFN-α in the forced swimming test was inhibited by the μ1-specific opioid receptor antagonist, naloxonazine and the μ1 and μ2 receptor antagonist, β-FNA. In contrast, neither naltrindole, a selective δ-opioid receptor antagonist, nor nor-BNI, a κ-opioid receptor antagonist were able to block the effect of human IFN-α. These results suggest that the effect of human IFN-α might be mediated through central opioid receptors of the μ-type in particular the μ1-subtype.

Although some previous reports have indicated that opioid agonists exerted antidepressant-like activity (Nabeshima et al., 1988; Baamonde et al., 1992; Tejedor-Real et al., 1998), which was opposite to our results, these reports indicated that the activity induced by opioid agonists was mainly mediated through δ-type of opioid receptors because antidepressant-like activity induced by opioid agonists was blocked by naltrindole, a δ-opioid antagonist. On the other hand, Amir (1982) reported that the low dose of morphine induced the immobility, and our preliminary study indicated that a low dose of morphine induced the immobility, but higher doses of morphine (>10 mg/kg s.c.) decreased the immobility mediated through δ or κ-opioid receptors. Collectively, these results showed that opioid agonists might have dual action; the depressant-like activity, mainly mediated through μ-opioid receptors and antidepressant-like activity, mainly mediated through δ-opioid receptors. In the present study, we indicated that human IFN-α-induced immobility (depressant-like activity) may be mediated through μ-type of opioid receptors, likewise the effect of the low dose of morphine.

In the present study, we demonstrated that central and peripheral administration of IFN-α, but not IFN-β or -γ, induced the increase in the immobility time in the forced swimming test. It is likely that our animal experimentation reflects the clinical observations in which the incidence of psychosis including depression observed during IFN-α therapy is higher than that of IFN-β or -γ (Bocci, 1988; Vial & Descotes, 1994: Takagi, 1995). Our study also indicates that the effect of IFN-α could be mediated by central opioid receptors of the μ-type, although the involvement of opioid receptors in the occurrence of depression is unclear in the clinical trials. Further studies focusing on the mechanisms of the depressant effect of human IFN-α with special reference of how IFN-α activates the opioid systems are currently in progress.

Abbreviations

- CNS

central nervous system

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- β-FNA

β-funaltrexamine

- IFN

interferon

- nor-BNI

nor-binaltorphimine

References

- ADAMS F., FERNANDEZ F., MAVLIGIT G. Interferon-induced organic mental disorders associated with unsuspected pre-existing neurologic abnormalities. J. Neurooncol. 1988;6:355–359. doi: 10.1007/BF00177432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AMIR S. Involvement of endogenous opioids with forced swimming-induced immobility in mice. Physiol. Behav. 1982;28:249–251. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(82)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAAMONDE A., DAUGÉ V., RUIZ-GAYO M., FULGA I.G., TURCAUD S., FOURNIÉ-ZALUSKI M.C., ROQUES B.P. Antidepressant-type effects of endogenous enkephalins protected by systemic RB101 are mediated by opioid δ and dopamine D1 receptor stimulation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;216:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIRMANNS B., SAPHIER D., ABRAMSKY O. α-Interferon modifies cortical EEG activity: dose-dependence and antagonism by naloxone. J. Neurol. Sci. 1990;100:22–26. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(90)90007-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLALOCK J.E., SMITH E.M. Human leukocyte interferon: Structural and biological relatedness to adrenocorticotropic hormone and endorphins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1980;77:5972–5974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.10.5972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLALOCK J.E., SMITH E.M. Human leukocyte interferon (HuIFN-α): potent endorphin-like opioid activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1981;101:472–478. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOCCI V. Central nervous system toxicity of interferons and other cytokines. J. Biol. Regul. Homeostat. Agents. 1988;2:107–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOCCI V. Pharmacology and side-effects of interferons. Antiviral Res. 1994;24:111–119. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARR D.J.J., GEBHARDT B.M., PAUL D. Alpha adrenergic and mu-2 opioid receptors are involved in morphine-induced suppression of splenocyte natural killer activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;264:1179–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAFNY N. Is interferon-α a neuromodulator. Brain Res. Rev. 1998;26:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAFNY N., LEE J.R., DOUGHERTY P.M. Immune response products alter CNS activity: Interferon modulates central opioid functions. J. Neurosci. Res. 1988;19:130–139. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490190118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE SARRO G.B., MASUDA Y., ASCIOTI C., AUDINO M.G., NISTICO G. Behavioral and ECoG spectrum changes induced by intracerebral infusion of interferons and interleukin 2 in rats are antagonized by naloxone. Neuropharmacol. 1990;29:167–179. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIANZANI F., ANTONELLI G., CAPOBIANCHI M.R. The biological basis for clinical use of interferon. J. Hepatol. 1990;11:S5–S10. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90156-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GISSLINGER H., SVOBODA T., CLODI M., GILLY B., LUDWIG H. Interferon-α stimulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in vivo and in vitro. Neuroendocrinol. 1993;57:489–495. doi: 10.1159/000126396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREIG N.H., SONCRANT T.T., WOZNIAK K.M., RAPOPORT S.I. Plasma and tissue pharmacokinetics of human interferon-alpha in the rat after its intravenous administration. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;245:574–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HABIF D.V., LIPTON R., CANTELL K. Interferon crosses blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier in monkeys. Proc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1975;149:287–289. doi: 10.3181/00379727-149-38790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANICKI P.K. Binding of human alpha-interferon in the brain tissue membranes of the rat. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol, Pharmacol. 1992;75:117–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JORDAN G., FRIED R., MERIGAN T.C. Administration of human leukocyte interferon in herpes. I. Safety, circulating antiviral activity, and host responses to infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1974;130:56–62. doi: 10.1093/infdis/130.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JORNVALL H., PERSSON M., EKMAN R. Structural comparisons of leukocyte interferon and proopiomelanocortin correlated with immunological similarities. FEBS Lett. 1982;137:153–156. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMEI J., SAITOH A., SUZUKI T., MISAWA M., NAGASE H., KASUYA Y. Buprenorphine exerts its antinociceptive activity via μ1-opioid receptors. Life Sci. 1995;56:PL285–PL290. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRUEGER J.M., DINARELLO C.A., SHOHAM S., DAVENNE D., WALTER J., KUBILLUS S. Interferon alpha-2 enhances slow-wave sleep in rabbits. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1987;9:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(87)90107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAKINO M., KITANO Y., HIROHASHI M., TAKASUNA K. Enhancement of immobility in mouse forced swimming test by treatment with human interferon. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;356:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAKINO M., KITANO Y., KOMIYAMA C., TAKASUNA K. Human interferon-α increases immobility in the forced swimming test in rats. Psychopharmacol. 2000;148:106–110. doi: 10.1007/s002130050031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANSOUR A., FOX C.A., AKIL H., WATSON S.J. Opioid-receptor mRNA expression in the rat CNS: anatomical and functional implications. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:22–29. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93946-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTINO S., SINGHAKOWINTA A. Serial interferon alpha2 levels in serum and cerebrospinal fluid. Cancer Treat. Rep. 1984;68:1057–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATTSON K., NIIRANEN A., IIVANAINEN M., FARKKILA M., BERGSTROM L., HOLSTI L.R., CANTELL K. Neurotoxicity of interferon. Cancer Treat, Rep. 1983;67:958–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MENZIES R.A., PATEL R., HALL N.R.S., O'GRADY M.P., RIER S.E. Human recombinant interferon alpha inhibits naloxone binding to rat brain membranes. Life Sci. 1992;50:227–232. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90555-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERIMSKY O., REIDER-GROSWASSER I., INBAR M., CHAIT-CHIK S. Interferon-related mental deterioration and behavioral changes in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 1990;26:596–600. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(90)90086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYERS C.A., SCHEIBEL R.S., FORMAN A.D. Persistent neurotoxicity of systemically administered interferon-alpha. Neurology. 1991;41:672–676. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NABESHIMA T., KATOH A., KAMEYAMA T. Inhibition of enkephalin degradation attenuated stress-induced motor suppression (conditioned suppression of motility) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;244:303–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAUL D., BODNAR R.J., GISTRAK M.A., PASTERNAK G.W. Different μ receptor subtypes mediate spinal and supraspinal analgesia in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;168:307–314. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90792-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PESTKA S., LANGER J.A., ZOON K.C., SAMUEL C.E. Interferons and their actions. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1987;56:727–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORSOLT R.D., ANTON G., BLAVET N., JALFRE M. Behavioral despair in rats: A new model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1978;47:379–391. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(78)90118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORSOLT R.D., LE PICHON M., JALFRE M. Depression: a new animal model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Nature. 1977;266:730–732. doi: 10.1038/266730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRASAD S., WATERS B., HILL P.B., PORTERA F.A., RIELY C.A. Psychiatric side effects of interferon alpha-2b in patients treated for hepatitis C. Abstract. Clinical Research. 1992;40:840A. [Google Scholar]

- QUESADA J.R., TALPAZ M., RIOS A., KURZROCK R., GUTTERMAN J.U. Clinical toxicity of interferon in cancer patients: a review. J. Clin. Oncol. 1986;4:234–243. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REISINE T., BELL G.I. Molecular biology of opioid receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:506–510. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90194-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RENAULT P.F., HOOFNAGLE J.H., PARK Y., MULLEN K.D., PETERS M., JONES D.B., RUSTGI V., JONES E.A. Psychiatric complications of long-term interferon alpha therapy. Arch. Intern. Med. 1987;147:1577–1580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROHATINER A.Z.S., PRIOR P.F., BURTON A.C., SMITH A.T., BALKWILL F.R., LISTER T.A. Central nervous system toxicity of interferon. Br. J. Cancer. 1983;47:419–422. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1983.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAPHIER D., WELCH J.E., CHULUYAN H.E. α-Interferon inhibits adrenocortical secretion via μ1-opioid receptors in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;236:183–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCOTO G.M., PARENTI C. Central and peripheral involvement of endogenous opioid peptides in gastric protection in stressed rats. Pharmacol. 1996;52:56–60. doi: 10.1159/000139361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEN G.C., LENGYEL P. The interferon system. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:5017–5020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMEDLEY H., KATRAK M., SIKORA K., WHEELER T. Neurological effects of recombinant human interferon. Br. Med. J. 1983;286:262–264. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6361.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH R.A., NORRIS F., PALMER D., BERNHARDT L., WILLS R.J. Distribution of alpha interferon in serum and cerebrospinal fluid after systemic administration. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1985;37:85–88. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1985.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINMANN G.G., ROSENKAIMER F., LEITZ G. Clinical experiences with interferon-α and interferon-γ. Int. Rev. Exp. Pathol. 1993;34B:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUTER C.C., WESTMORELAND B.F., SHARBROUGH F.W., HERMANN R.C., JR Electroencephalographic abnormalities in interferon encephalopathy: A preliminary report. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1984;59:847–850. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAGI S. Psychiatric manifestations of interferon therapy. Seishin Igaku (Clinical Psychiatry) 1995;37:344–358. [Google Scholar]

- TEJEDOR-REAL P., MICO J.A., SMADJA C., MALDONADO R., ROQUES B.P., GIBERT-RAHOLA J. Involvement of δ-opioid receptors in the effects induced by endogenous enkephalins on learned helplessness model. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;354:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIAL T., DESCOTES J. Clinical toxicity of the interferons. Drug Safety. 1994;10:115–150. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199410020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIRANOWSKA M., WILSON T.C., THOMPSON K., PROCKOP L.D. Cerebral interferon entry in mice after osmotic alternation of blood–brain barrier. J. Interferon Res. 1989;9:353–362. doi: 10.1089/jir.1989.9.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WITTERT G. , HOPE P., PYLE D. Tissue distribution of opioid receptor gene expression in the rat. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;218:877–881. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]