Abstract

The effect of the antiarrhythmic drug dronedarone on the Acetylcholine-activated K+ current (IK(ACh)) was investigated in single cells isolated from sinoatrial node (SAN) tissue of rabbit hearts.

Externally perfused dronedarone (0.001–1 μM) caused a potent, voltage independent block of IK(ACh). Fitting of the dose response curve of IK(ACh) block yielded an IC50 value of 63 nM, a value over one order of magnitude lower than those reported for dronedarone block of other cardiac currents.

IK(ACh) block was not due to an inhibitory action of dronedarone on the muscarinic M2 receptor activation, since the drug was effective on IK(ACh) constitutively activated by intracellular perfusion with GTP-γS.

External cell perfusion with dronedarone inhibited the activity of IK(ACh) channels recorded from cell-attached patches by reducing the channel open probability (from 0.56 to 0.11) without modification of the single-channel conductance.

These data suggest that dronedarone blocks IK(ACh) channels either by disrupting the G-protein-mediated activation or by a direct inhibitory interaction with the channel protein.

Keywords: Dronedarone, IK(ACh), amiodarone, sinoatrial node, single channel

Introduction

The rate of cardiac contraction is determined by the spontaneous activity of the sinoatrial node (SAN) which reflects the combined electrical contribution of several ionic conductances. Sympathetic and parasympathetic stimulation affect the electrical activity of the heart by modifying some of these currents in the SAN as well as in atrial and ventricular tissue. Tonic release of ACh by the cardiac branch of the vagal system for example exerts its bradycardic action by reducing both the pacemaker (If) and the L-type calcium (ICa,L) currents (Zaza et al., 1996) and by activating, via direct G-protein coupling, a K+ conductance (IK(ACh)) (Breitwieser & Szabo, 1985; Renaudon et al., 1997).

Pathological alterations of the physiological cardiac rhythm are generated by a variety of mechanisms and represent an area of intense investigation since they affect a substantial segment of the adult population. Amiodarone is one of the most frequently employed drugs in the therapeutic treatment of cardiac arrhythmias and is known for both its antiadrenergic properties and its direct depressant effect on many cardiac ionic conductances; unfortunately, amiodarone also determines hypothyroidism-like effects. Dronedarone (Sanofi-Synthelabo) is a benzofuran derivative related to amiodarone; previous studies on several ionic currents involved in cardiac activity (If, IK, INa, ICa,L, ICa,T) suggested that dronedarone, like amiodarone, possesses the properties of an unspecific ion channel blocker (Rocchetti et al., 1998). The lack of adverse side effects in animals treated with dronedarone makes this drug potentially important for clinical use. Here we show that dronedarone is a potent inhibitor of the ACh-activated K+ current (IK(ACh)) since it blocks this current at doses over one order of magnitude smaller than those reported for other currents (Rocchetti et al., 1998), and the high sensitivity of the block suggests that this drug is a potentially useful pharmacological tool to dissect the effect of IK(ACh) from other cardiac currents.

Methods

Protocols employed in our experiments conformed to the guidelines of the care and use of laboratory animals established by State (DL. 116/1992) and European directives (86/609/CEE).

Cell isolation

Spontaneously active ‘pacemaker' myocytes were isolated from the SAN region of rabbit hearts according to the methods previously reported (DiFrancesco et al., 1986). Briefly, New Zealand rabbits (0.8–1.0 kg) were anaesthetized by i.m. injection of a mixture of Xilazine (4.6 mg kg−1; Sigma) and Ketamine (60 mg kg−1; Sigma). Animals were then sacrificed by cervical dislocation and hearts quickly removed and placed in a prewarmed (37°C) normal Tyrode solution (mM): NaCl 140, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1, HEPES-NaOH 5, Glucose 5.5, pH 7.4) containing 0.1 ml heparin (5000 U ml−1). Anatomical isolation of the SAN was performed under a binocular microscope; the atria were separated from the ventricles and the internal wall of the right atrium was cut open to expose the SAN. Reference points for the determination of the nodal tissue were the superior and inferior venae cavae, the crista terminalis and the interatrial septum. Small strips of central nodal tissue were cut perpendicularly to the crista terminalis and initially treated in an enzyme-containing solution (mM): NaCl 140, KCl 5.4, MgCl2 0.5, CaCl2 0.2, KH2PO4 1.2, taurine 50, glucose 5.5, HEPES-NaOH 5, albumine (BSA) 5 mg, collagenase 1120 U (Worthington), elastase 9.5 U (Sigma), protease 3 U; (Sigma) to loosen intracellular connections; this procedure was followed by a mechanical trituration in a Ca2+-free solution (mM): KCl 20, glutamic ac. 70, β-hydroxybutirric ac. 10, KH2PO4 10, taurine 10, HEPES-KOH 80, pH 7.4. Single cells obtained after this treatment were then slowly readapted to physiological Ca2+ concentration and stored at 4°C until ready for the experiment.

Experimental methods and solutions

The whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique was used to study the effect of the benzofuran derivative N,N-dibutyl-3-[4-((2-butyl-5-methylsulphonamido) benzofuran-3-yl-carbonyl)phenoxy] propylamine, hydrochloride: (Dronedarone by Sanofi Synthelabo) on the IK(ACh) current. Petri dishes containing isolated cells were placed on the stage of an inverted microscope and superfused with the control solution. In order to increase the size of the K+ current investigation the external control solution was a high K+ Tyrode containing (mM): NaCl 140, KCl 25, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 1.8, HEPES NaOH 5, Glucose 5.5, CsCl 5 and MnCl2 2 were added to block the pacemaker (If) and Ca L-type currents. IK(ACh) was elicited by adding ACh (10 μM) to the control solution. Different concentrations of dronedarone were prepared by diluting a 5 mM stock solution (3 mg ml−1 ethanol). Ethanol was also added to the control and ACh-containing solutions; in pilot experiments we verified that addition of ethanol had no effects on the size and time course of the current elicited by ACh (not shown). Whole-cell patch pipettes were filled with an intracellular-like solution (mM): K-Aspartate 130, NaCl 10, EGTA KOH 5, HEPES-KOH 10, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, ATP(Na2) 2, creatine phosphate 5, GTP 0.1, pH 7.2), and had a resistance of 2–4 MΩ. In some whole-cell experiments guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (GTP-γS, 100 μM), a non-hydrolizable analogue of GTP, was added to the pipette solution to induce irreversible activation of IK(ACh) channels.

Single-channel data were recorded in the cell-attached configuration; the extracellular solution in the recording pipettes was (mM): KCl 150, CaCl2 1.8, HEPES 5, pH 7.4, ACh (0.1 μM) was added to the pipette solution to activate the muscarinic receptor. Sylgard coating (Levis & Rae, 1993) was employed to reduce pipette capacitance and improve the signal-to-noise ratio. A high K+ bath solution (mM): KCl 130, NaCl 10, HEPES-KOH 5, MgCl2 2, glucose 10, MnCl2 2, pH 7.4 was used to zero the cell resting potential and to allow for a precise control of membrane potential during the experiment.

Control and test solutions were delivered to the cell under investigation through a fast-perfusion device; all experiments were carried out at room temperature (20–24°C). Electrophysiological measurements were performed with pClamp 7.0 software and an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Inc., Foster City, CA, U.S.A.). Software developed in our laboratory was also utilized.

Results

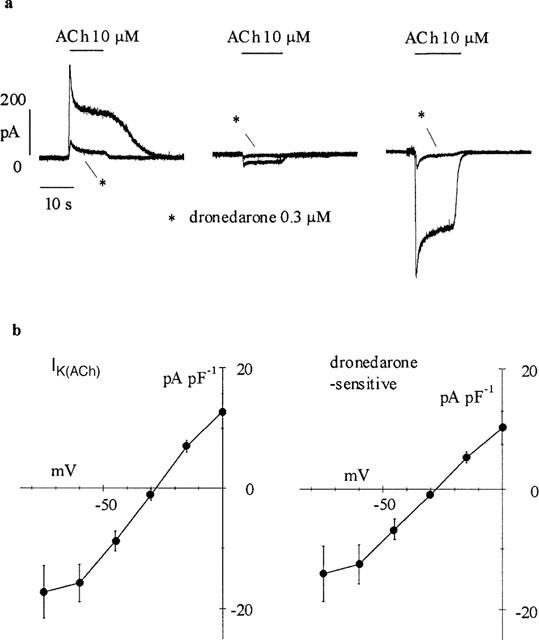

To activate the ACh-dependent K+current, cells were held at different holding potentials and superfused with ACh (10 μM) for 10 s. The current elicited by ACh had a rapid onset followed by a slowly developing decay, reversed at voltages near the predicted EK and disappeared upon wash off of ACh; these properties confirmed that the current under investigation was the ACh-activated K+ current (Carmeliet & Mubagwa, 1986). Figure 1 illustrates a typical experiment where the action of dronedarone on IK(ACh) was tested. After the whole-cell configuration was established and a stable holding current recorded in control conditions, we tested for the presence of IK(ACh) by 10 s perfusion with ACh (10 μM). The cell was then exposed for at least 3 min (to allow full development of its action) to dronedarone (300 nM) and ACh was again perfused in the presence of the drug. This protocol was repeated at different voltages and sample traces recorded at 0, −30 and −60 mV are superimposed in Figure 1a. In all cases dronedarone (300 nM, traces labelled by asterisks) caused a marked block of IK(ACh), which did not appear to be dependent upon current direction.

Figure 1.

Effect of dronedarone on IK(ACh) elicited by ACh (10 μM). (a) ACh-induced current recorded in three cells before and after 3 min exposure to dronedarone (300 nM, asterisks) at holding potentials of 0, −30 and −60 mV (left to right). (b) Mean current-voltage (I-V) relations for IK(ACh) (n=7) and dronedarone-sensitive current (n=7). Current amplitudes were measured as the difference between the peak and the baseline and normalized to cell capacity. Linear regression in the range −60 to 0 mV yielded slope conductances of 0.41 and 0.34 pS pF−1, and reversal potentials of −28.9 and −28.1 mV for the ACh-activated and dronedarone-blocked components, respectively.

The same protocol was repeated using different holding potentials and dronedarone concentrations in a total of 27 cell, and mean current-voltage (I-V) relations for IK(ACh) and dronedarone-sensitive currents normalized to cell capacity are shown in Figure 1b. Control and drug-sensitive current amplitudes, measured as the difference between peak and baseline current levels, were plotted against holding potentials. Reversal potentials for IK(ACh) and dronedarone-sensitive currents, calculated by fitting the linear part of the curves, were −28.7±1.1 (n=7) and −29.3±0.9 (n=7), respectively; these values are not significantly different (P<0.05). A comparison between the two I-V curves shows a similar voltage dependence, suggesting lack of voltage dependence of channel blockade. It also appears that both I-V relations display a reduction of conductance at voltages negative to −60 mV. A conductance decrease may result from a voltage-dependent channel blocking action of external Cs+ ions, which becomes evident at the most negative potentials investigated (Carmeliet & Mubagwa, 1986). The inward rectifying nature of the ACh-induced K+ current was confirmed by extending the analysis of the I-V relation to positive voltages (n=6, data not shown).

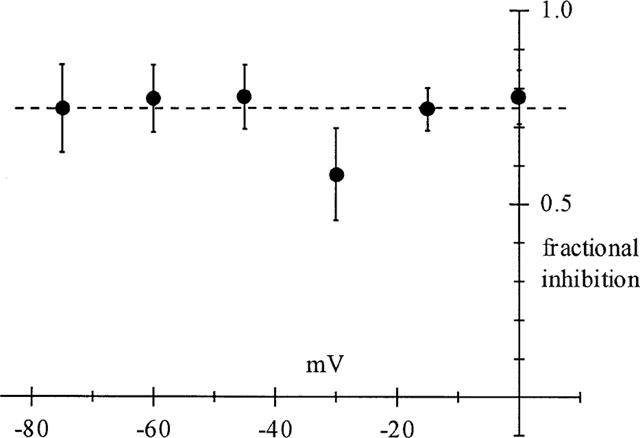

The lack of voltage dependence of dronedarone-induced IK(ACh) block was confirmed by the analysis shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Lack of voltage-dependence of dronedarone-induced block on IK(ACh). Data points were calculated as the ratio between the difference of peak currents in control and after addition of the drug (300 nM), and control peak amplitude, and represent the mean fractional inhibition obtained at different potentials (n=6–9) for each potential.

Fractional current inhibition was calculated from data as those in Figure 1a as the ratio between difference current amplitude in the presence and absence of the drug and control current amplitude. Data points represent mean±s.e.mean values obtained at different potentials in n=6–9 cells. A correlation index of 0.014 obtained by regression analysis confirmed that dronedarone block of the IK(ACh) channel is independent from membrane voltage.

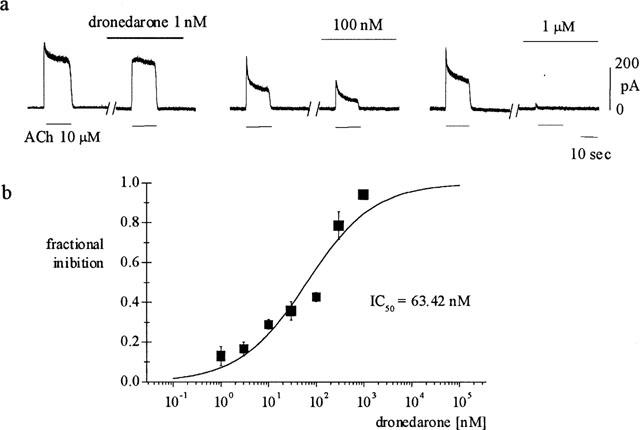

To investigate the concentration-dependence of the block, we measured IK(ACh) at a fixed voltage (0 mV) before and during drug exposure. In Figure 3a the results from three representative cells are plotted. Since drug-induced block of IK(ACh) was not fully reversible we used a single drug concentration for each cell to avoid cumulative effects.

Figure 3.

Concentration dependence of dronedarone-induced IK(ACh) block. (A) Sample traces recorded from three different cells (holding potential of 0 mV). IK(ACh) was elicited by 10 s exposure to ACh (10 μM) before and after 3 min perfusion of dronedarone at the indicated concentrations; block of peak current is apparent at concentrations as low as 1 nM. (b) Dose-response curve illustrating the concentration dependence of IK(ACh) block. Experimental data points, representing the mean (±s.e.mean) of four separate measurements for each concentration, were fitted to the Hill equation (full line) by setting the maximal value to 1. Half-block concentration and Hill coefficient were 63.4 and 0.61 nM, respectively.

To avoid desensitization of the current response to muscarinic receptor activation during prolonged exposures (Boyett & Roberts, 1987), we measured the dronedarone-induced current block by comparing peak currents obtained upon short (10 s) ACh exposures before and after 3 min perfusion with dronedarone. In pilot experiments we verified that there was no significant IK(ACh) current change within this time (average change after 3 min from first ACh application in three control cells was −5.07±5.21%, not significantly different from zero, P>0.1).

From the sample data shown in Figure 3, it appears that even concentrations as low as 1 nM induced a measurable reduction of the peak ACh-activated K+ current. A dose-response curve of IK(ACh) block is shown in Figure 3b where mean±s.e.mean fractional block values, as measured on the peak current, are plotted for concentrations of dronedarone in the range 1–1000 nM. Fitting of the dose-response data with the Hill equation yielded a half-block value (IC50) of 63.4 nM and a Hill coefficient of 0.61.

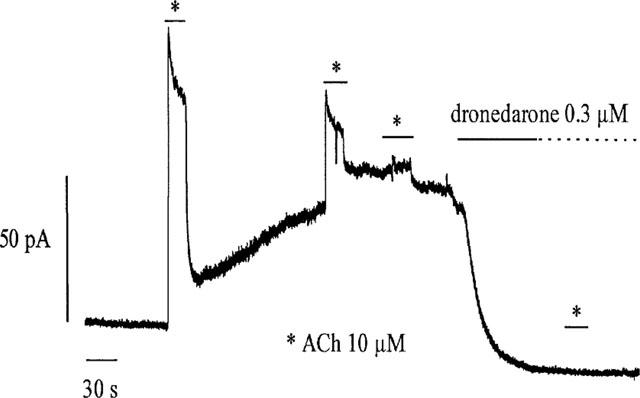

Since the activation of IK(ACh) depends on a G-protein-mediated interaction between muscarinic receptors and channel proteins, dronedarone could act by uncoupling this cascade of events at different levels. In order to dissect possible effects of dronedarone on the receptor-G-protein interaction from downstream events, we tested the action of the drug after constitutively activating the G-proteins by intracellular perfusion with GTP-γ-S. Immediately after establishing the whole-cell configuration, IK(ACh) was activated at 0 mV by a 10 s perfusion with ACh (10 μM, Figure 4). Under these conditions, IK(ACh) activation was nearly fully reversible upon ACh wash out. Following return of the current towards the baseline, a slow upward current deflection started to develop. To verify if this behaviour reflected activation of IK(ACh) by GTP-γS-induced G-protein activation following cell dialysis, we applied ACh at different times during development of the outward current. In accordance with this hypothesis, the current stimulated by ACh progressively decreased with time until it was fully abolished after about 400 s after establishment of whole-cell conditions. Lack of response to ACh and the attainment of a stable level of outward current developed during whole-cell recording were taken as indication that the ACh-activated K+ current was fully activated. Perfusion of dronedarone at this point produced a slow decrease of the current to a level similar to the one at the beginning of the experiment. The decay could be fitted by a single exponential time course with a time constant of 29.9 s.

Figure 4.

Current trace recorded in whole-cell conditions using a GTP-γS-containing solution. After establishing the whole-cell configuration with a GTP-γS-containing pipette solution, an upward drift of the baseline current developed indicating the activation of K(ACh) channels. Repetitive perfusions with ACh (10 μM, asterisks) induced currents of decreasing amplitudes. Dronedarone (300 nM) fully reversed the effect of GTP-γS, but did not restore the ability of ACh to activate the current.

Further perfusion of ACh did not elicit any current responses. We obtained similar results in a total of seven cells at two different voltages (0 mV, n=5; −80 mV, n=2). These data rule in favour of the hypothesis that dronedarone acts either by functionally uncoupling the G-protein channel interaction or by directly binding to the channel.

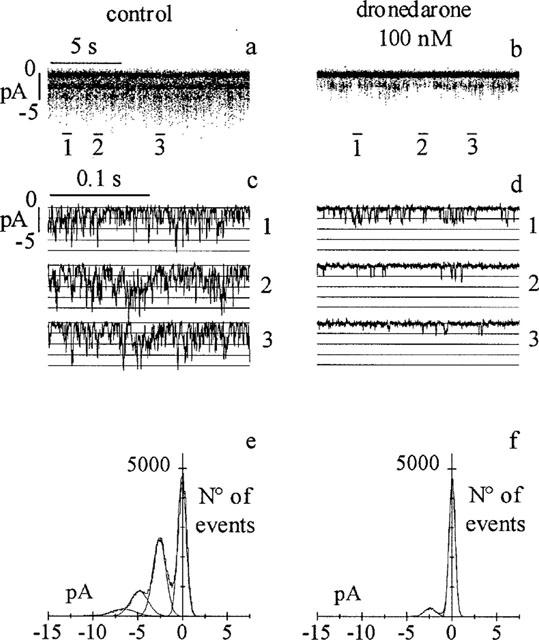

Channel blockers can act by reducing the single channel conductance and/or by modifying the probability of channel openings (Hille, 1992). We performed single-channel experiments in the cell-attached configuration in order to test whether bath perfusion with dronedarone could induce the block of channels present in the recording pipette. Patch pipettes containing ACh (0.1 μM) were sealed onto the cell membrane and channel activity was recorded in control conditions and during perfusion with dronedarone (300 nM). In Figure 5, sample traces and all-points distributions obtained from a typical experiment are shown.

Figure 5.

Dronedarone reduces IK(ACh) single channel activity by decreasing the open probability (Po). Single channel events were recorded in the cell-attached patch configuration before (a) and after (b) external perfusion of the drug onto the cell; three segments from the traces in a and b (bars) are shown on an expanded time scale in (c) and (d). All-points histograms of records in a and b, and the multi-Gaussian fitting are shown in e and f. The mean channel amplitudes were 2.46 pA in control (e) and 2.41 pA during drug perfusion (f). Po, calculated as the area of open states normalized to the total area determined by the multiple fitting function, was 0.56 and 0.11 in the control and dronedarone records, respectively.

Single channel events measured at −80 mV (20 s) in control and in presence of the drug are shown in Figure 5a,b; selected representative segments from the same traces (bars) are plotted, on a more expanded time scale, in Figure 5c,d. The presence of dronedarone in the bath solution induced a marked decrease of the activity of channels present in the patch pipette, implying that the site of action of the drug is intracellular. The open probability (Po) and single channel amplitude were calculated from the all-point distribution of traces in Figure 5a,b. All-points distribution analysis (Figure 5e,f) indicates that dronedarone did not modify the single channel conductance (2.46 pA vs 2.41 pA respectively in control and dronedarone) but clearly decreased the open probability (0.56 vs 0.11). Similar results were obtained in another cell.

Discussion and conclusions

Acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter playing a key role in the modulation of many heart functions (Wickman et al., 1998). Drugs that mimic or antagonize the effect of ACh are widely utilized in cardiac pharmacology; among these one of the most used in antiarrhythmic therapy is the class III agent amiodarone. Detailed studies on the effects of amiodarone in atrial cardiac cells have shown that this drug produces a prolongation of the action potential duration by inhibiting the ACh-activated K+ current (Watanabe et al., 1996). However amiodarone is not a selective blocker of ACh-activated K+ channels since it can also block several other ionic conductances (Sato et al., 1994; Singh, 1994). As part of a screening project aimed at selecting more specific channel blockers, we tested in SAN single cells the ability of the amiodarone derivative dronedarone (for detailed structures: Manning et al., 1995) to modify the ACh-activated K+ current. SAN myocytes were chosen as the experimental substrate since in these cells IK(ACh), together with the pacemaker current (If), contributes to parasympathetic modulation of heart rate.

The results presented in Figure 1 indicate that dronedarone, like amiodarone, blocks the ACh-activated K+ current. Both the ACh-activated and the drug-sensitive currents had a similar reversal potential and were linear in the range −60/0 mV. A slight deviation from linearity at negative potential was detected in both I-V curves, possibly reflecting a partial voltage-dependent reduction due to the presence of extracellular Cs+ (5 mM) (Carmeliet & Mubagwa, 1986), which we used in order to block the If current. The block of IK(ACh) by dronedarone was, on the other hand, linear in the voltage range investigated (−75 to 0 mV), as demonstrated by the lack of voltage dependence of fractional inhibition in this range (Figure 2).

Dronedarone blocks IK(ACh) with an IC50 of 63.4 nM, a value over one order of magnitude lower than that of amiodarone (∼2 μM, Watanabe et al., 1996). The shallow Hill coefficient (0.61) of the dose-block relation might indicate negative cooperative binding of dronedarone to IK(ACh) channels. However, we have no evidence favouring this or alternative mechanisms to explain this characteristic, and further experimentation will be needed to clarify it.

Experimentation in guinea-pig atrial and SAN action potentials showed that dronedarone, like amiodarone, induces significant modification of most action potential parameters and inhibits several currents (ICaL, ICaT, If, IK; Rocchetti et al., 1998). Although a precise determination of IC50 values is not available for all dronedarone-inhibited currents, where known these values are in the micromolar range. Thus, the very high potency of IK(ACh) block induced by dronedarone points to this drug as a potentially useful specific IK(ACh) blocker. For a more complete knowledge of dronedarone effects on cardiac currents, it would also be important to verify the affinity for other members of the inward rectifier channel family (Kir), and especially the IKl current.

Opening of ACh-dependent K+ channels is a G-protein-mediated multiple step process triggered by the interaction of ACh with the muscarinic (M2) receptor (Kurachi, 1995). The identification of the site of IK(ACh) block by dronedarone was therefore an important aspect to evaluate. Watanabe et al. (1996) studied the inhibitory effect of amiodarone on IK(ACh) activated by the muscarinic agonist carbachol, GTP-γS or adenosine; in all cases the IC50 values for inhibitory action of amiodarone on IK(ACh) were similar (∼2 μM). Since the three activation pathways are different, the authors concluded that amiodarone must act directly at the channel level and not upstream of the channel protein. The dronedarone molecule is structurally derived from amiodarone, suggesting that the two drugs may have a similar mechanism of action; we confirmed this hypothesis by verifying that dronedarone blocks ACh-dependent K+ channels previously opened by GTP-γS-induced activation of G proteins. The simplest assumption able to account for the inhibitory action of dronedarone on IK(ACh) is a drug-induced channel block. Current decrease could also be explained by alternative mechanisms such as for example inhibition of G-protein-channel interaction. However, we favour the blocking mechanisms since dronedarone blocks several other channels whose action is not dependent upon G-protein binding.

Dronedarone is a highly lipophilic molecule that can easily diffuse into the cell membrane. Results such as those in Figure 4, indicating a relatively slow time course of IK(ACh) inhibition (τ=29.9 s) are more compatible with a diffusion process than with an extracellular blockade mediated by drug entry into the channel. Intracellular diffusion was confirmed by cell-attached experiments where dronedarone was externally perfused, but was missing from the pipette solution; block of single-channel activity under these conditions (Figure 5a–c) requires that dronedarone diffuses through the membrane and into the cytoplasm before reaching its site of block. Although this does not exclude the possibility of an interaction between drug and channel occurring within the membrane, it indicates the need for the free-diffusion of drug molecules for block to occur, in agreement with the view that current inhibition could be due to interaction between channels and soluble drug molecules. Channel blockers exert their effects by modifying the open probability (Po) and/or reducing the single channel conductance (Hille, 1992). The analysis of dronedarone effects on IK(ACh) at the single channel level (Figure 5) indicates that the drug acts by lowering Po while leaving unaltered the single channel conductance.

In summary our data suggest that dronedarone is an efficient voltage independent blocker of IK(ACh) channels. The low IC50 (nM range) makes this drug potentially useful as a selective blocker of IK(ACh) since IC50 values larger by at least one order of magnitude are reported in literature for other ionic currents contributing to electrical activity of SAN cells (Rocchetti et al., 1998).

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Ferroni and M. Rocchetti for helpful discussion and A. Bucchi and E. Camatini for technical assistance. This work was supported by SANOFI Recherche, Montpellier, France.

Abbreviations

- Dronedarone

N,N-dibutyl-3-[4-((2-butyl-5-methylsulphonamido)benzofuran-3-yl-carbonyl)phenoxy] propylamine

- GTP-γS

guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate)

- hydrochloride

C31H44N2O55HCl

- IK(ACh)

Acetylcholine activated K current

- SAN

sinoatrial node

References

- BOYETT M.R., ROBERTS A. The use of quartz patch pipette for low noise single channel recording. Bioph. J. 1987;65:1666–1777. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81224-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BREITWIESER G.E., SZABO G. Uncoupling of cardiac muscarinic and β-adrenergic receptors from ion channels by a guanine nucleotide analogue. Nature. 1985;317:538–540. doi: 10.1038/317538a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARMELIET E., MUBAGWA K. Characterization of the acetylcholine-induced potassium current in rabbit cardiac Purkinje fibres. J. Physiol. 1986;371:219–237. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIFRANCESCO D., FERRONI A., MAZZANTI M., TROMBA Properties of the hyperpolarizing-activated current(if) in cells isolated from the rabbit sino-atrial node. J. Physiol. 1986;377:61–88. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILLE B. Sinauer Associates Inc., Sunderland, MA, U.S.A; 1992. Ionic channels of excitable membranes. [Google Scholar]

- KURACHI Y.G protein regulation of cardiac muscarinic potassium channel Am. J. Physiol. 1995269C821–C830.(Cell Physiol. 38) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVIS R.A., RAE J.L. The use of quartz patch pipette for low noise single channel recording. Bioph. J. 1993;65:1666–1777. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81224-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANNING A.S., BRUYNINCKX C., RAMBOUX J., CHATELAIN P. SR 33589B, a new amiodarone-like agent: effect on ischemia- and reperfusion-induced arrhythmias in anesthetized rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharm. 1995;26:453–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RENAUDON B., BOIS P., BESCOND J., LENFANT J. Acetylcholine modulates If and IK(ACh) via different pathways in rabbit sino-atrial node cells. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:969–975. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROCCHETTI M., BERTRAND J.P., NISATO D., GAUTIER P. Cellular electrophysiological study of dronedarone, a new amiodarone-like agent, in Guinea pig sinoatrial node. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1998;358,1 Suppl.2:R617. [Google Scholar]

- SATO R., KOUMI S., SINGER H.D., HISATOME I., JIA H., EAGER S., WASSERSTROM A.J. Amiodarone blocks the inward rectifier potassium channel in isolated guinea-pig ventricular cells. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 1994;269:1213–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINGH B.N.Amiodarone: pharmacological, electrophysiological, and clinical profile of unusual antiarrhythmic compound Electropharmacological control of cardiac arrhythmias: to delay conduction on prolong refractoriness 1994Futura Publishing Company, Inc., Mount Kisco, NY; 493–522.ed. Singh, B.N. Wellens, H.J.J. and Hiraoka, M [Google Scholar]

- WATANABE Y., HARA Y., TAMAGAWA N., NAKAYA H. Inhibitory effect of amiodarone on the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-operated potassium current in guinea pig atrial cells. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 1996;279.2:617–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WICKMAN K., NEMEC J., GENDLER S.J., CLAPHAM D.E. Abnormal heart rate regulation in GIRK4 knockout mice. Neuron. 1998;20:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAZA A., ROBINSON R.B., DIFRANCESCO D. Basal response of the L-type Ca2+ and hyperpolarization-activated currents to autonomic agonists in the rabbit sino-atrial node. J. Physiol. 1996;491.2:347–355. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]