Abstract

We studied the effects of benzylalcohol on heterologously expressed wild type (WT), paramyotonia congenita (R1448H) and hyperkalaemic periodic paralysis (M1360V) mutant α-subunits of human skeletal muscle sodium channels.

Benzylalcohol blocked rested channels at −150 mV membrane potential, with an ECR50 of 5.3 mM in wild type, 5.1 mM in R1448H, and 6.2 mM in M1360V. When blockade was assessed at −100 mV, the ECR50 was reduced in R1448H (2 mM) compared with both wild type (4.3 mM; P<0.01) and M1360V (4.3 mM).

Membrane depolarization before the test depolarization significantly promoted benzylalcohol-induced sodium channel blockade. The values of KD for the fast-inactivated state derived from benzylalcohol-induced shifts in steady-state availability curves were 0.66 mM in wild type and 0.58 mM in R1448H. In the presence of slow inactivation induced by 2.5 s depolarizing prepulses, the ECI50 for benzylalcohol-induced current inhibition was 0.59 mM in wild type and 0.53 mM in R1448H.

Recovery from fast inactivation was prolonged in the presence of drug in all clones.

Benzylalcohol induced significant frequency-dependent block at stimulating frequencies of 10, 50, and 100 Hz in all clones.

Our results clearly show that benzylalcohol is an effective blocker of muscle sodium channels in conditions that are associated with membrane depolarization. Mutants that enter voltage-dependent inactivation at more hyperpolarized membrane potentials compared with wild type are more sensitive to inhibitory effects at the normal resting potential.

Keywords: Preservatives, benzylalcohol, muscle sodium channels, paramyotonia congenita, hyperkalaemic periodic paralysis

Introduction

Some of the bacteriostatic agents or stabilizers that are contained in pharmaceutical products are far from being pharmacologically inert. We have recently shown that 4-chloro-m-cresol, an additive in some formulations of suxamethonium and heparin, is a potent blocker of muscle sodium channels (Haeseler et al., 1999). Benzylalcohol, a structurally related substance, is in more widespread use as bacteriostatic diluent. Many therapeutic agents, including formulations of vitamins and heparin, antibiotics, sedatives, and antidysrhythmic drugs for parenteral administration, contain considerable amounts of benzylalcohol (10–240 mg vial−1). Although the acute toxicity of benzylalcohol after single doses in healthy anaesthetized animals appears to be minimal (Kimura et al., 1971), reports of its being linked to the ‘gasping syndrome' in neonates (Benda et al., 1986) brought its true toxicity into question. Animal studies have shown that acute toxicity after sublethal doses of benzylalcohol was primarily characterized by neuromuscular symptoms (such as loss of motor function), dyspnoea, and sedation (McCloskey et al., 1986). As benzylalcohol is well-known for its local anaesthetic properties (Nuttall et al., 1993, Wilson & Martin, 1999), our aim in this study was to examine the effects of benzylalcohol on human muscle Na+ channels, which might in part determine its toxicity. Effects were tested on channels from healthy subjects (wild type), and from patients with paramyotonia congenita and hyperkalaemic periodic paralysis. These muscle diseases belong to a group of sodium channelopathies that are caused by the exchange of single amino acids within the channel protein, resulting in altered function (Lehmann-Horn & Rüdel, 1995). In the paramyotonia congenita mutant R1448H a positively charged and extracellularly positioned arginine is replaced by a histidine; in the hyperkalaemic periodic paralysis mutant M1360V an intracellularly positioned methionine is replaced by a valine.

Methods

Molecular biology

Wild type, R1448H, and M1360V mutant α-subunits of human muscle sodium channels were heterologously expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK 293) cells, a stable cell line since 1962 (American Tissue Culture Collection CRL 1573). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the pSELECT mutagenesis system (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, U.S.A.), as described by Chahine et al. (1994) and Wagner et al. (1997). Full-length R1448H and M1360V mutant α-subunits were reassembled in the mammalian expression vector pRc/CMV (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Plasmids containing either wild type α-subunits or the mutant sequence along with other regions from the wild type channel were transfected into HEK 293 cells, using calcium phosphate precipitation (Graham & Van der Eb, 1973). Permanent expression was achieved by selection for resistance to the aminoglycoside antibiotic geneticin G418 (Life Technology, Eggenstein, Germany) (Mitrovic et al., 1994).

Experimental set-up

Standard whole-cell voltage-clamp experiments (Hamill et al., 1981) were performed at 20°C. Patched cells were lifted up into the visible stream of either bath solution or test solution, applied via a 2-channel superfusion pipette close to the cell. To ensure adequate adjustment of the application device, one test experiment in aqua dest reducing inward sodium current to zero was performed every 6–10 experiments. Each experiment consisted of test recordings with the drug present at only one concentration, and of drug-free control recordings before and after the test. At least three experiments were performed at each concentration.

Solutions

Test solutions containing benzylalcohol (FLUKA, D-82041, Deisenhofen, Germany) in different concentrations in bath solution were prepared immediately before the experiments. Patch electrodes contained (mM) CsCl2 130, MgCl2 2, EGTA 5, HEPES 10; the bath solution contained (mM) NaCl 140, MgCl2 1, KCl 4, CaCl2 2, HEPES 5, dextrose 5. All solutions were adjusted to 290 mosm by addition of mannitol and to pH 7.4 by the addition of CsOH.

Current recordings and analysis

For data acquisition and further analysis we used the EPC9 digitally-controlled amplifier in combination with Pulse and Pulse Fit software (HEKA Electronics, Lambrecht, Germany). The EPC9 provides automatic subtraction of capacitive and leakage currents by means of a prepulse protocol. The data are filtered at 10 kHz and digitized at 20 μs per point. Input resistance of the patch pipettes was at 1.8–2.5 MΩ. We used only small cells with capacitances of 9–15 pF; residual series resistance (after 50% compensation) was 1.2–2.5 MΩ; experiments with a rise in series resistance were rejected. The time constant of the voltage settling within the membrane (residual series resistance × cell capacitance) was <35 μs. To minimize a possible contribution of endogenous Na+ channels in HEK cells that conduct with amplitudes ranging from 50 to 350 pA (Mitrovic et al., 1994), but also to avoid large series resistance errors, we only analysed currents ranging between 1 and 18 nA.

Resting state affinity and affinity for the slow-inactivated state

Blockade of rested channels was defined as a reduction in the maximum current elicited by 10 ms depolarizing pulses going from either −150 mV or −100 mV to 0 mV, 90 s after the start of perfusion with the drug-containing solution. In order to estimate drug binding to the slow-inactivated state compared with the resting state, the effects of different concentrations of benzylalcohol on the current response, elicited by 40 ms test pulses from −100 mV to 0 mV, were compared with the effects on the current response when introducing a 2.5 s inactivating prepulse to −35 mV before the test pulse. Currents were normalized with respect to the current response obtained with the same protocol in the control experiment. Concentration-response curves for drug effects on rested or slow-inactivated channels were obtained by plotting the fractional maximum currents against the applied concentration of benylalcohol. Hill fits (INa+=[1+([C]/ECR50)nH]−1) to the data yielded the concentration for half-maximum channel blockade of rested (ECR50) or slow-inactivated (ECI50) channels, the Hill coefficient nH described the stoichiometry of drug binding to the channel. INa+ represents the fractional sodium current in the presence of the drug; [C] represents the applied concentration of benzylalcohol.

Steady-state availability

The voltage-dependence of Na+ channel availability was obtained from a double-pulse protocol with a 50 ms prepulse starting at −150 mV up to prepulse potentials ranging from −150 mV to −5 mV, immediately followed by a 4 ms test pulse to 0 mV. Peak INa in response to this step was normalized to INa elicited by the test pulse at the most negative prepulse (−150 mV). Boltzmann fits to the resulting current–voltage plots yielded the membrane potential at half-maximum channel availability (V0.5) and the slope factor z: I/Imax=(1+exp(−zF(Vtest−V0.5)/RT))−1, where F and R are Faraday's constant and Gas constant, T is the temperature in K.

Time-course of channel activation

Time constants of inactivation, τh, were obtained from single or biexponential fits to the decaying currents, following 40 ms voltage jumps from −100 mV to 0 mV: I(t)=a0+a1exp(−t/τh1)+a2exp(−t/τh2).

Recovery from inactivation

Recovery from inactivation was assessed by a two-pulse recovery protocol: a 36 ms inactivating pulse to 0 mV was followed by a variable recovery interval at −100 mV; thereafter, a 25 ms test depolarization to 0 mV was used to elicit a peak current to assess the fraction of channels that had recovered during the preceding recovery interval. The currents elicited by the test pulse were normalized to the peak current elicited by the corresponding prepulse and plotted against the recovery interval. A biexponential curve was fitted to the data, yielding the time constant of recovery from inactivation τrec: I(t)=a0+a1exp(−t/τrec1)+a2exp(−t/τrec2).

Frequency-dependent block

The frequency-dependent effects of benzylalcohol were studied by applying 10, 50 or 100 Hz depolarizing pulses for 5–10 ms from a holding potential of −100 mV to 0 mV. The current amplitude during each pulse was normalized to the first pulse.

Statistics

All data are presented descriptively as mean±s.d. Statistical analysis of the concentration-response-plots was performed in order to reveal differences related to mutant or applied pulse protocol. Curve fitting and parameter estimation of the Hill curves was performed using the program ‘Non-linear Least Squares Regression' of S-PLUS (S-PLUS 2000 Professional Release 1, © 1988-1999 MathSoft, Inc., Cambridge, MA, U.S.A.). The differences between the parameter values (EC50 and nH) of two independent data sets were entered into the common model as shift parameters ΔEC50 and ΔnH, activated for all data of the 2nd data set. The corresponding (asymptotic) t-value was used to test the null hypothesis of no parameter difference. Statistical analysis of frequency dependent block was performed by 3-way analysis of variance taking into account the factors channel type (wild type and R1448H), pulse frequency (10, 50, 100 Hz) and concentration (0.5, 1, 3, 5 mM). The null hypothesis was rejected when the P-value was <0.05.

Results

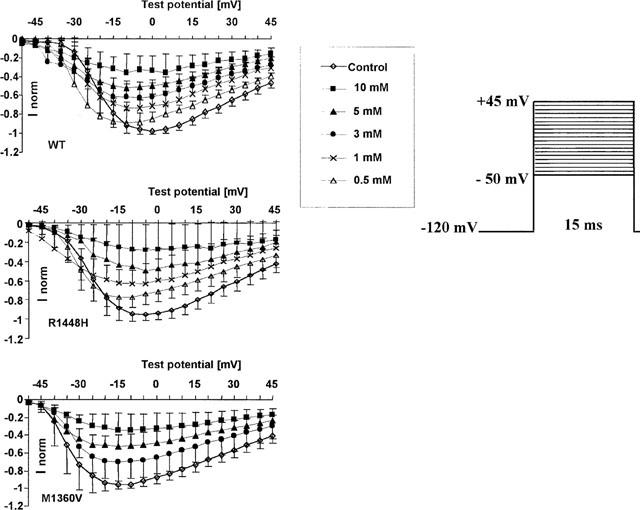

Tonic inhibition of Na+ current by benzylalcohol–resting state affinity

Successful Na+ channel expression was verified electrophysiogically in almost 100% of the established whole-cell patches. Average currents in the control experiments following depolarization from −100 mV to 0 mV were 2.9±1.5 nA in WT, 4.6±2.5 nA in R1448H and 5.6±2.4 nA in M1360V. Benzylalcohol effectively blocked whole-cell Na+ currents after series of depolarizing pulses starting from −120 mV in wild type, the paramyotonia congenita mutant R1448H, and the hyperkalaemic periodic paralysis mutant M1360V. Current–voltage plots obtained from different series of experiments for each concentration of benzylalcohol in the three clones are shown in Figure 1. With increasing concentrations of benzylalcohol to the extracellular solution, the normalized current in the respective current-voltage curves decreased.

Figure 1.

Normalized peak current-voltage plots following families of depolarizing pulses in control conditions and at different concentrations of benzylalcohol (n>3 for each concentration and each clone). Each symbol on the curves represents the mean fractional peak current (with respect to the corresponding peak current in the control), elicited by depolarizations from −120 mV to the indicated test potentials (mV). Error bars are standard deviations. The controls depicted here represent the starting values for all test experiments; each cell was only exposed to one test concentration. Benzylalcohol blocked sodium currents in a concentration-dependent manner in all clones.

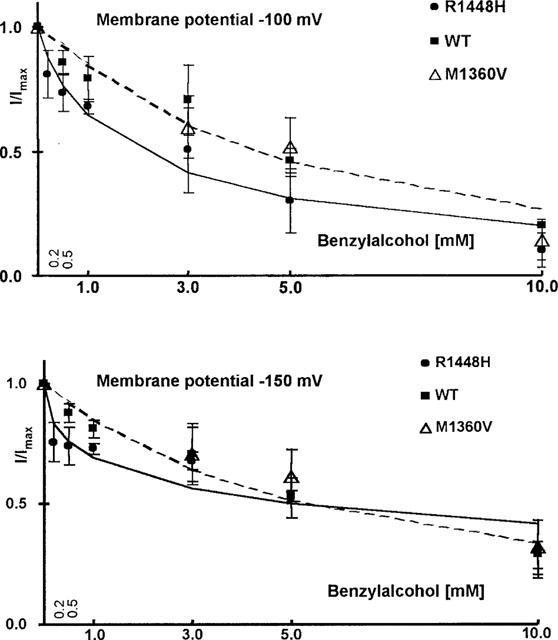

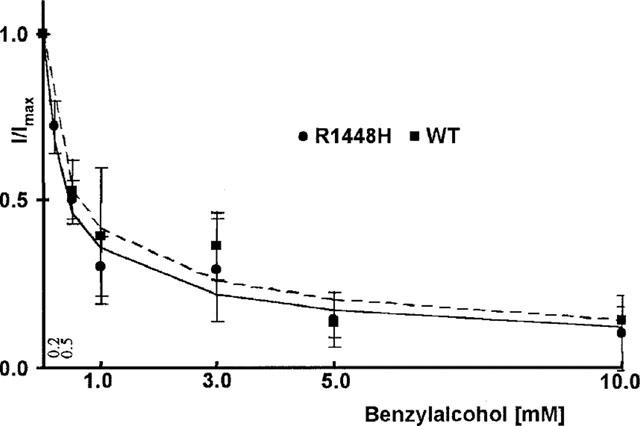

Benzylalcohol-induced block of rested channels was quantitatively assessed by depolarizations to 0 mV starting at either −150 mV or −100 mV holding potential. This protocol was chosen to show a possible reduction in the ECR50 at more depolarized membrane potentials previously reported for other channel blockers (Fan et al., 1996; Haeseler et al., 1999). Hill fits to the concentration-response plots (Figure 2) yielded ECR50 values of 5.3 mM in wild type, 5.1 mM in R1448H, and 6.2 mM in M1360V at −150 mV and 4.3 mM in wild type, 2 mM in R1448H, and 4.3 mM in M1360V at −100 mV. The reduction in ECR50 at a holding potential of −100 mV with respect to −150 mV was statistically significant only for R1448H (P value 0.03, one-tailed testing because the direction of the effect was anticipated). At −100 mV, the difference in ECR50 between WT and R1448H was significant as well (two-tailed P value 0.01). Calculated values for nH were 1.0/1.2 in wild type, 0.5/0.9 in R1448H, and 1.4/1.7 in M1360V at −150 mV and −100 mV respectively. The difference in nH between R1448H and WT at −150 mV was statistically significant (two-tailed P-value 0.017). Reversibility of benzyl-alcohol-induced channel block during wash-out ranged from 48% (R1448H) to 73% (wild type).

Figure 2.

Concentration-dependent reduction in test pulse current with respect to control (n>3, mean±s.d.), applying different protocols. Depolarizing pulses to 0 mV were started from either −150 or −100 mV. Dotted lines are Hill fits to the wild type data, the solid lines are Hill fits to the R1448H data. When depolarizations were started from −150 mV, the concentration for half-maximum effect was nearly the same for the three clones. At −100 mV, R1448H showed stronger effects at all concentrations tested.

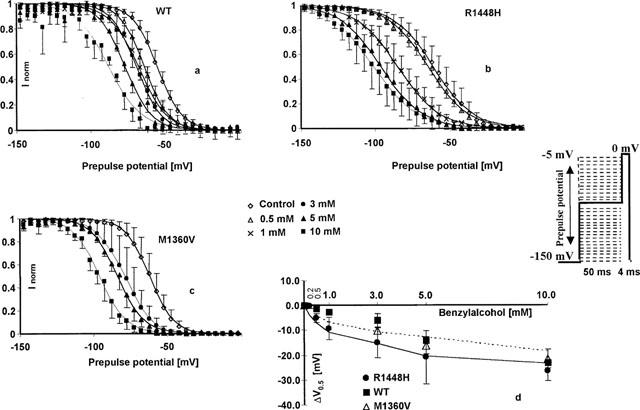

Affinity for the fast-inactivated state estimated by steady-state availability shifts

After brief depolarizations, Na+ channels enter a fast-inactivated state, from which they cannot readily reopen. Steady-state availability curves reflect the availability of Na+ channels to open on depolarization to 0 mV as a function of membrane potential. Currents elicited by the test pulses starting from varying prepulse potentials (from −150 mV to −5 mV), normalized to the current elicited at the most hyperpolarized prepotential (−150 mV), represent the relative fraction of channels that have not been inactivated or blocked during the 50 ms inactivating pre-pulse. The prepulse potential at half-maximum inactivation(V0.5) obtained from Boltzmann fits reflects the position of the curve along the voltage axis, which, in control conditions, represent the voltage-dependent distribution between resting state and inactivated state at a given membrane potential. Summarized data for the three channel types (n=3 for each concentration and each clone) showed that V0.5 in the controls was more negative in R1448H (V0.5 −66.6±8.3 mV) and M1360V (V0.5 −64.6±5.4 mV) compared with wild type (V0.5 −58.7±2.6 mV). The slope factors z were −3.6±0.3 in wild type, −1.9±01 in R1448H, and −3.5±0.4 in M1360V. Benzylalcohol shifted V0.5 considerably in the direction of more negative prepulse potentials; the degree of alteration depended on drug concentration and clone (see Figure 3a–c). Drug binding reached steady-state within 50 ms duration of the inactivating pulses, and prolongation of the prepulse duration up to 100 ms did not enhance drug effects. Small time-dependent hyperpolarizing shifts of −6.3 mV (R1448H) and −7.4 mV (wild type and M1360V), revealed by series of control experiments in bath solution, were subtracted from the drug-induced shifts. The concentration-dependent left-shifts of the steady-state inactivation curves (illustrated in Figure 3d for WT and R1448H) reflect the additional reduction of channel availability induced by benzylalcohol in the potential range from −20 to −120 mV compared with −150 mV. This suggests that the drug has a higher affinity for the channel when it is in the inactivated state. The voltage-dependence of inactivation, reflected by the slope factors z remained unchanged in the presence of drug (see Figure 3a–c). In the presence of the blocker, the position of the steady-state availability curve relative to control conditions reflects drug association with channels in resting as well as fast-inactivated states (the 50 ms prepulses were too short to induce slow inactivation). Assuming that the inactivated state has a higher binding affinity for a blocking drug than the resting state, the higher amount of channel block achieved with consecutive membrane depolarization revealed by the drug-induced hyperpolarizing shifts reflects the apportionment of channels between resting and fast-inactivated states as well as the different binding affinities for the two channel states. At the example of lidocaine effects on Purkinje fibres, Bean et al. (1983) developed a model predicting the shift in midpoint of the steady-state inactivation curve as a function of lidocaine concentration using estimates for lidocaine's affinity for the resting and inactivated states derived from experiments at depolarized or hyperpolarized membrane potentials, respectively. We employed the model developed by Bean et al. (1983) to estimate the dissociation constant (KD) of benzylalcohol for the fast-inactivated state of the channel in the three clones, fitting the concentration-dependence of V0.5 according to: ΔV0.5=k×ln[(1+[C]/ECR50) × (1+[C]/KD)−1] where ΔV0.5 is the shift in the midpoint in each concentration of benzylalcohol (mean, n=3), k the slope factor for the availability curve (k=−RT/Fz), [C] the applied concentration of benzylalcohol, ECR50 the concentration for half-maximum effect derived from the concentration-response-plots at −150 mV membrane potential depicted above, and KD the dissociation constant for benzylalcohol from the inactivated state (see Figure 3d). The estimated values of KD for wild type and R1448H were 0.66 and 0.58 mM respectively. In M1360V, only higher concentrations were evaluated, so a reasonable fit was not possible for those data.

Figure 3.

Benzylalcohol effects on the fast-inactivated channels. (a–c) Steady-state availability curves assessed by a two-pulse protocol in the absence (control) and presence of 0.5–10 mM benzylalcohol (wild type and R1448H), and 3–10 mM benzylalcohol (M1360V). Each symbol represents the mean fractional current (n=3 for each concentration and each clone) elicited by a 4 ms test pulse to 0 mV, following a 50 ms inactivating prepulse from −150 mV to the indicated prepulse potential. Currents were normalized to maximum value (in each series at −150 mV prepotential); solid lines represent the best Boltzmann fit to the data. Benzylalcohol shifted the midpoints of the curves in the direction of more negative prepulse potentials, reflecting an additional reduction in channel availability at depolarized prepotentials (compared with the block achieved at −150 mV). Drug-induced shift in the midpoints (ΔV0.5 (mV), mean±s.d.) of the steady-state availability plots relative to the starting values in the three clones. Small time-dependent shifts revealed by control experiments were subtracted. Solid or dotted lines are least-squares fits to the equation ΔV0.5 = k×ln[(1+[C]/ECR50)×(1+[C]/KD)−1] in R1448H and wild type, respectively.

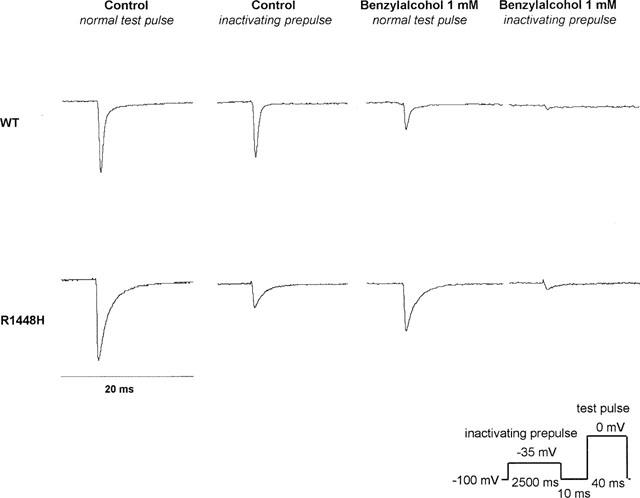

Benzylalcohol effects in the presence of slow inactivation

Drug binding to rested or fast inactivated channels does not reflect all aspects of drug effects, especially in pathological conditions, in which membrane potential might be depolarized for longer periods. Prolonged depolarization induces a slow-inactivated state that requires much longer periods for recovery (>1 s) (Balser et al., 1996). Therefore, the slow-inactivated state assumes particular importance in pathological conditions, such as myotonia or ischaemia, in which tissues are depolarized for longer periods. To examine drug binding to the slow-inactivated channel induced by prolonged depolarization, we stepped up the holding potential from −100 mV to −35 mV for 2.5 s. The membrane potential was then returned to −100 mV for 10 ms, allowing recovery from fast inactivation. The availability of unblocked resting channels was then assessed by a 40 ms test pulse to 0 mV. In control solution, the inactivating prepulse caused a reduction of the current elicited by the test pulse by 44±15% in wild type, 52±15% in R1448H, and 42±12% in M1360V (compare traces 1 and 2 in Figure 4). This is attributed to slow inactivation during the long conditioning prepulse, from which channels did not recover during the 10 ms repolarization (Ragsdale et al., 1994). Benzylalcohol blocked the peak current amplitude in the presence of slow inactivation almost completely at concentrations close to the ECR50 for rest block at −100 mV (see Figure 5). The residual currents in the presence of slow inactivation (with respect to the current amplitude obtained with the same protocol in control solution), plotted against the concentration of benzylalcohol applied, revealed no significant difference in the concentration for half-maximum effect (ECI50) between wild type (0.59 mM) and R1448H (0.53 mM) (see Figure 5). The Hill coefficient nH was 0.6 in both clones. In M1360V, only higher concentrations were evaluated with this protocol, so a reasonable fit was not possible for those data.

Figure 4.

Current recordings in 1 mM benzylalcohol, in the absence and presence of slow inactivation. Representative current traces (in control solution and in 1 mM benzylalcohol) evoked by 40 ms test pulses from −100 mV to 0 mV in the absence (traces 1 and 3) and presence (traces 2 and 4) of a 2.5 s inactivating prepulse introduced before the test pulse. All currents were normalized to the peak current in control solution without inactivating prepulse (trace 1). The peak current amplitude in trace 1 was 4.9 nA in WT and 2.5 nA in R1448H. In control solution, the inactivating prepulse caused a reduction in the current elicited by the test pulse due to slow inactivation, from which channels did not recover during the 10 ms repolarization (compare traces 1 and 2). Note that channel blockade achieved by 1 mM benzylalcohol was >90% in both clones with slow inactivation (compare traces 2 and 4), whereas without slow inactivation it was <70% (compare traces 1 and 3).

Figure 5.

Concentration-response plots of benzylalcohol effects on slow-inactivated channels. Concentration-dependent reduction in test pulse current when a 2.5 s inactivating prepulse was introduced before the test pulse (n>3, mean±s.d.). Currents were normalized to the current elicited with the same protocol in the controls. The solid and dotted lines are Hill plot fits to the R1448H and wild type data respectively. In the presence of slow inactivation, benzylalcohol blocked the currents almost completely at concentrations close to the ECR50 for rest block (compare Figure 2).

Acceleration of the Na+ current decay phase by benzylalcohol

To examine the time course of Na+ channel inactivation after a depolarization, series of 40 ms voltage steps from a holding potential of −100 mV were performed. At least three whole-cell patches each were evaluated in 1, 3, 5, and 10 mM benzylalcohol in wild type and R1448H, and in 3, 5, and 10 mM benzylalcohol in M1360V. The INa+ decay time-course was assessed by fitting a single exponential to the decay of currents after depolarizations to 0 mV obtained with wild type and M1360V channels and a biexponential in the case of R1448H. For M1360V, the time constant thus obtained was not different from wild type (τh 0.5±0.2 ms vs τh 0.46±0.1 ms in wild type). For R1448H, the decay was markedly slower (τh 1.4±0.6 ms) and obviously contained a second slower component that made up 17±10%. Benzylalcohol slightly accelerated the decay of whole-cell currents in all clones at concentrations >3 mM, but even high concentrations (10 mM) did not restore wild type inactivation to R1448H whole-cell currents. Values obtained for γh in the presence of drug were: 0.44±0.17 ms (wild type) and 1.2±0.4 ms (R1448H) in 1 mM benzylalcohol; 0.25±0.05 ms (wild type), 0.32±0.09 ms (M1630V), and 0.73±0.5 ms (R1448H) in 3 mM benzylalcohol; and 0.28±0.07 ms (wild type), 0.31±0.06 ms (M1360V), and 1±0.3 ms (R1448H) in 5 mM benzylalcohol.

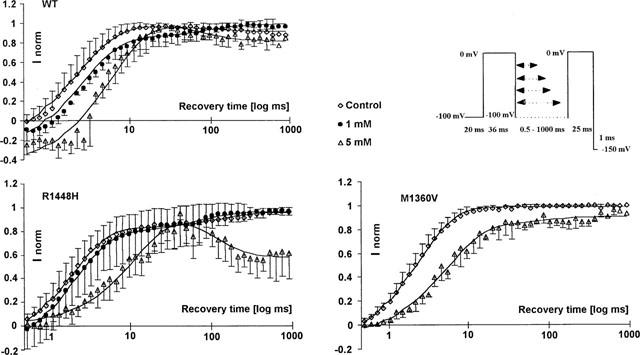

Effects of benzylalcohol on recovery from inactivation

After inactivation, channel reopenings are impossible until channels recover from inactivation, a process that requires several ms after membrane repolarization. Further information about drug effects on the stability of the fast inactivated state or the kinetics of drug dissociation from the fast inactivated state can be derived from the rate at which the channels recover from inactivation in the presence of the drug. The time of membrane repolarization required to remove fast inactivation was assessed at −100 mV by a two-pulse protocol with varying time intervals (up to 1000 ms) between the inactivating prepulse and the test pulse. Three experiments were performed for each concentration (1 and 5 mM in wild type and R1448H, 5 mM in M1360V) and each clone. The time constants of recovery (τrec) were derived from biexponential fits to the fractional current having recovered from inactivation, and plotted against the time interval between the inactivating prepulse and test pulse (see Figure 6). The fast component of recovery from inactivation, τrec1, was enhanced in both mutants (2.0±0.9 ms in M1360V and 1.9±1 ms in R1448H) compared with wild type (2.3±1 ms) in control conditions. The second, slow component of recovery, τrec2, was 16±4 ms in WT, 4.6±3.9 ms in R1448H and 2.9±1 ms in M1360V with amplitudes <14% in all clones. Benzylalcohol delayed recovery from inactivation in all clones. In 1 mM benzylalcohol, τrec1 was prolonged from 1.3±0.5 to 2.8±1 ms in wild type and from 0.9±0.2 to 2.2±03 ms in R1448H. The slow component, τrec2, of 145±77 ms (wild type) and 170±90 ms (R1448H) made up 11±9% (wild type) and 18±9% (R1448H) of the current amplitude. Benzylalcohol (5 mM) delayed the τrec1 from 3.2±0.5 to 7.6±4 ms (wild type), from 2.5±0.7 to 10.4±4 ms (R1448H) and from 2.6±0.6 to 5.4±1 ms in M1360V. Interestingly, there was a second decline in the current amplitude after the initial recovery, with prolongation of the recovery interval in R1448H and wild type in 5 mM benzylalcohol (see Figure 6). This second blockade of test pulse current relative to the inactivating pulse occurred on a time scale, τrec2, of 115±60 ms (both clones), comprising −49±18% (R1448H) and −30±28% (wild type) of the prepulse amplitude. This effect was not observed for M1360V, in which τrec2 occurred at 70±10 ms, with a positive amplitude of 22±9%.

Figure 6.

Recovery from inactivation assessed by a two-pulse protocol in the absence (control) and presence of 1 and 5 mM benzylalcohol in wild type and R1448H and 5 mM benzylalcohol in M1360V. The abscissa represents the recovery time interval between prepulse and test pulse on a logarithmic scale up to 1000 ms; the ordinate represents the fractional current (mean±s.d.) elicited by the test pulse with respect to the prepulse in the same series. Solid lines are biexponential fits to the data. In the presence of 1 mM benzylalcohol, recovery was markedly delayed and contained a second slow component that made up 11% (wild type) or 18% (R1448H) of the current amplitude. In the presence of 5 mM benzylalcohol, there was a second fall in the current amplitude after initial recovery, with prolongation of the recovery interval in R1448H and wild type. This effect was not observed with M1360V.

Frequency-dependent block

The accumulation of block during trains of depolarizing pulses indicates that the interval between pulses is too short to allow recovery of Na+ channel availability. To get an estimate of the kinetics of drug binding and unbinding during the interpulse interval, we applied a series of depolarizing pulses at high frequencies (10, 50 and 100 Hz). Frequency-dependent block was defined as the additional reduction in INa+ for the last pulse relative to the first pulse in a test train in the presence of benzylalcohol. Three to four experiments were performed in each concentration. Frequency-dependent block in response to trains of 10 ms depolarizing pulses applied at 10 Hz was <18% in all clones and all concentrations of benzylalcohol examined. Applying the 50 Hz protocol, frequency-dependent block was <6% in all clones in control conditions and 8±6% (wild type), 17±4% (R1448H), and 16±4% (M1360V) in 5 mM benzylalcohol. During a 100 Hz train, the additional fall relative to the first pulse was >18% in control conditions and 33±2% (wild type), 42±3% (R1448H), and 41±12% (M1360V) in 5 mM benzylalcohol. As a result of three-way analysis of variance, significant blocking effect on the last pulse relative to the first pulse in a test train of 10 pulses were caused independently by the factors channel type (R1448H>WT, P=0.001), stimulating frequency (100>50>10 Hz, P=0.001) and concentration (5>3>1>0.5 mM, P=0.001). There were no significant factor interactions. Thus, frequency-dependent block was present in both clones, but the amount was not significantly different between R1448H and wild type.

Discussion

Modulation of benzylalcohol-induced block by the kinetic state of the channel

We have shown that benzylalcohol blocks both normal and mutant skeletal muscle sodium channels. Similar studies on sodium channels with other local anaesthetics or antidys-rhythmic drugs such as lidocaine (Balser et al., 1996; Pugsley & Goldin, 1998) have shown that the affinity of the drug strongly depends on the kinetic state of the channel. When hyperpolarized for longer periods, Na+ channels have a low affinity for benzylalcohol. The ECR50 for rest block at hyperpolarized membrane potentials (−150 mV) was high in the three clones examined (5–6 mM). In contrast, high affinity block was seen when membrane depolarization before the test pulse induced channel inactivation. In native tissues, drug-free sodium channels can occupy at least two inactivated conformations that are kinetically distinct (Balser et al., 1996). Brief depolarizations induce fast inactivation, from which recovery at hyperpolarized membrane potentials is rapid (<10 ms), whereas prolonged depolarizations (>500 ms) induce slow inactivation. Slow-inactivated channels require long repriming periods (>1 s) at hyperpolarized membrane potentials to regain availability (Balser et al., 1996). When short depolarizing prepulses (50 ms) were applied to induce fast inactivation before the test pulse, benzylalcohol consecutively reduced channel availability, with more positive prepotentials (relative to −150 mV). This additional drug-induced reduction in channel availability at depolarized membrane potentials is revealed by a hyperpolarizing shift in the steady-state availability curve. The estimated dissociation constant from the fast inactivated state KD, derived from the concentration-dependence of this shift, was 600 μM for wild type and 580 μM for R1448H. Slow inactivation occurs on a time scale of seconds to minutes and may modulate excitability in response to slow shifts in the resting potential (Takahashi & Cannon, 1999). When channels were depolarized for a longer period (2.5 s), inducing slow inactivation, benzylalcohol achieved block of the residual current during depolarization to 0 mV with an ECI50 of 530 μM in R1448H and 590 μM in wild type. This finding might gain particular importance in pathological conditions, such as hypoxia or ischaemia, in which the muscle membrane is depolarized for longer periods (Lehmann-Horn & Rüdel, 1995). The large difference in EC50 values for inactivated states compared with the resting state we found for benzylalcohol is qualitatively comparable to the effects described for lidocaine on skeletal muscle sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Balser et al., 1996). Unlike structurally related Na+ channel blockers, such as benzocaine (Sah et al., 1998) and the phenol derivative 4-chloro-m-cresol (Haeseler et al., 1999), benzylalcohol accelerated the time course of channel inactivation only to a small extent at high concentrations (>3 mM).

Analogous to the effects described for other Na+ channel blocking drugs (Fan et al., 1996), channel repriming following a depolarization is delayed in the presence of benzylalcohol. This might on one hand be due to drug-induced stabilization of the inactivated state. On the other hand, removal of inactivated channel block at −100 mV could slow down overall recovery processes studied by using a two-pulse protocol. Our experimental protocol does not elucidate the precise role of fast inactivation in benzylalcohol action, because gating transitions that occur in drug-bound channels do not involve changes in ionic current. However, experiments employing a conformational marker for the fast inactivation gate revealed that lidocaine-induced slowing of sodium channel repriming does not result from a slowing of recovery of the fast-inactivation gate (Vedantham & Cannon, 1999). If the same holds for benzylalcohol, recovery from fast inactivation would precede recovery of the ionic current in drug-bound channels. Thus, the frequency-dependent block of Na+ currents seen with benzylalcohol and lidocaine-like local anaesthetics at high rates of stimulation can be interpreted as resulting from an accumulation of drug-associated channels when the interpulse interval at −100 mV becomes too short to allow recovery from inactivated channel blockade (Pugsley & Goldin, 1999). Exceptions are benzocaine (Quan et al., 1996) and the phenol derivative 4-chloro-m-cresol, which induces only very little frequency-dependent block, even at 100 Hz (Haeseler et al., 1999). Following short depolarizations (<100 ms) we do not expect any accumulation of slow inactivation under our experimental conditions. While Na+-channel α-subunits expressed in oocytes without auxiliary β-subunits conveniently display a prominent component of slow inactivation after short (<50 ms) depolarizations (Balser et al., 1996), expression of α-subunits in a mammalian cell line resulted in channels exhibiting normal (with respect to experiments in native tissue) rapid activation and inactivation (Chahine et al., 1994b). In addition, mutants leading to an exchange of the arginine in position 1448 or the methionine in position 1360 revealed no detectable alteration in slow inactivation (Takahashi et al., 1999). Thus, a possible contribution of alterations in recovery from slow inactivation in the mutants modulating frequency-dependent block can be excluded. The finding that wild type and R1448H channels exhibit a second fall in the current amplitude in 5 mM benzylalcohol after recovery from fast inactivation was completely unexpected. It is conceivable that dissociation from the inactivated state occurs on a faster time scale than binding to rested channels.

Sensitivity to benzylalcohol in mutant channels compared to wild type–influence of altered gating kinetics in control conditions

Paramyotonia congenita and hyperkalaemic periodic paralysis are both attributed to altered inactivation phenotypes, a common feature in most sodium channel myopathies (Lehmann-Horn & Rüdel, 1995). In both mutants the steady-state inactivation plots were at more negative membrane potentials compared to WT, the degree of alteration being more severe in R1448H. These findings are consistent with previous reports (Chahine et al, 1994a; Wagner et al., 1997). In addition, the time course of channel inactivation is severely impaired in R1448H (Chahine et al., 1994a). Incomplete channel inactivation after activation of subpopulations of mutant sodium channels is considered sufficient to cause consecutive membrane depolarization, leading to long-lasting hyperexcitability if depolarization is mild and to hypoexcitability if depolarization is severe enough to cause channel inactivation (Lehmann-Horn & Rüdel, 1995).

While resting state affinity at strongly hyperpolarized membrane potentials (−150 mV) was the same in the three clones, the ECR50 for channel blockade at −100 mV was significantly lower in R1448H compared with both wild type and M1360V. This finding is consistent with results on lidocaine sensitivity of the paramyotonia congenita mutant R1448C compared to that of the wild type at different resting potentials (Fan et al., 1996). As the mutant did not enhance the affinity of the different kinetic states of the channel for benzylalcohol, the voltage-dependent higher sensitivity of R1448H to benzylalcohol might be due to altered kinetics of distribution between the resting and inactivated states of the channel in the controls, revealed by the amount of hyperpolarizing shift in steady-state inactivation plots compared with wild type. A possible explanation is that the rate of entry into the inactivated state is faster in the mutants at membrane potentials more negative than −60 mV (Yang et al., 1994). Thus, R1448H should reveal more rest block induced by either benzylalcohol or lidocaine, owing to binding of the drug to the inactivated state at any given membrane potential more positive than −100 mV. The resting potential of muscle is much less hyperpolarized than the holding potential used in our experiments. In addition, muscle fibre membranes that express inactivation-deficient Na+ channels might be even more depolarized than normal membranes (Lehmann-Horn & Rüdel, 1995). Thus, shifts in steady-state availability induced by the mutants are likely to be important in vivo, making mutant channels much more susceptible to benzylalcohol than normal channels. This hypothesis equally holds for the enhanced sensitivity of cardiac vs skeletal muscle Na+ channels to local anaesthetics. Experiments on heterologously expressed rat skeletal and human cardiac muscle Na+ channels have shown that the greater sensitivity of cardiac tissue to cocaine or lidocaine is due to a greater percentage of inactivated (=high-affinity) channels at physiological resting potentials (Wright et al., 1997).

Clinical implications

From our in vitro results we conclude that benzylalcohol has little effect on normal muscle membranes at hyperpolarized membrane potentials. However, in pathological conditions in which the normal resting potential cannot be maintained and muscle membranes are depolarized for longer periods, benzylalcohol might affect muscle excitability at very low concentrations. Although the results obtained for benzylalcohol at the molecular level are difficult to frame into clinical terms, we could show that benzylalcohol concentrations <500 μM exert substantial blockade of muscle sodium channels in the presence of slow inactivation. This corresponds to serum levels reached in benzylalcohol-exposed mice when adverse reactions like loss of motor function, dyspnoea and sedation were apparent (McCloskey et al., 1986; Montaguti et al., 1994). Lethality due to respiratory paralysis corresponded to a sharp increase in benzylalcohol plasma concentrations from 86 up to 150–200 μg ml−1 (1.5–2.0 mM), which is in the concentration range in which we observed substantial benzylalcohol-induced block of rested channels and complete block in the presence of inactivation. That study equally suggested a risk of accumulation due to saturable kinetics of elimination of benzylalcohol, so that a small increase in dosage would produce a disproportionately higher plasma benzylalcohol concentration, resulting in rapid occurrence of toxicity. In addition, the authors could unambiguously show that acute toxicity of the alcohol including sedation, dyspnoea and loss of motor function is due to the alcohol itself and not to its metabolites (McCloskey et al., 1986). Elimination of benzylalcohol depends on hepatic alcohol dehydrogenase (McCloskey et al., 1986; Kawamoto et al., 1995). The velocity of the reaction shows a sigmoid inhibition curve due to substrate saturation (Messiha, 1991). At high concentrations of benzylalcohol, turnover is inhibited by the formation of enzyme–alcohol binary and abortive ternary complexes (Shearer et al., 1993). In addition, hepatic alcohol dehydrogenase substrate competition between benzylalcohol and ethanol may precipitate adverse metabolic interaction (Messiha, 1991; Smith-Kielland & Ripel, 1992). Although benzyl alcohol-containing preparations are commonly used in intensive care units up to a possibly daily intake of 1 g die−1, little is known about the serum levels that are actually reached during long-term parental administration. One case of benzylalcohol poisoning has been reported in a 5-year-old girl who received benzylalcohol-containing diazepam for control of status epilepticus. Over a 36 h period, 180 mg kg−1 die−1 benzylalcohol had been administered with the diazepam infusion. At that time, serum concentrations of benzoic acid, a 1:1 metabolite of benzylalcohol measured by gas chromatography were found at 18 mg ml−1 (150 mM) (Lopez-Herce, 1995). These results indicate that serum levels of benzylalcohol must have been equally high, benzylalcohol accumulation due to ADH-deficiency cannot be excluded. Thus, long-term administration of benzylalcohol-containing solutions to patients with impaired hepatic function or the use of benzylalcohol-containing formulations during ethanol consumption requires special alertness with regard to possible neuromuscular adverse effects.

Conclusions

Benzylalcohol is an effective blocker of skeletal muscle Na+ channels at depolarized membrane potentials. Na+ channel mutants with altered gating kinetics enhance benzylalcohol binding at normal resting potentials. Our results suggest that long-term benzylalcohol administration in pathological conditions might considerably affect muscle membrane excitability.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Prof Lehmann-Horn, Ulm, for providing us with transfected cells. We thank Birgitt Nentwig, Department of Anaesthesiology, Hannover, for taking care of the cell culture and Jobst Kilian, Department of Neurology, Hannover, for technical support.

Abbreviations

- ECI50

concentration of benzylalcohol producing half-maximum effect in the presence of slow inactivation induced by a 2.5 s inactivating prepulse

- ECR50

concentration of benzylalcohol producing half-maximum effect at hyperpolarized membrane potentials

- F

Faraday's constant (9.648×104 C mol−1)

- M1360V

sodium channel mutant substituting methionine for valine in the channel protein

- R

gas constant (8.315 J K−1 mol−1)

- R1448H

sodium channel mutant substituting arginine for histidine in the channel protein

References

- BALSER J.R., BRADLEY NUSS H., ROMASHKO D.N., MARBAN E., TOMASELLI G.F. Functional consequences of lidocaine binding to slow-inactivated sodium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 1996;107:643–658. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.5.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEAN B.P., COHEN C.J., TSIEN R.W. Lidocaine block of cardiac sodium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 1983;81:613–642. doi: 10.1085/jgp.81.5.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENDA G.I., HILLER J.L., REYNOLDS J.W. Benzyl alcohol toxicity: impact on neurologic handicaps among surviving very low birth weight infants. Pediactrics. 1986;77:507–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAHINE M., BENNETT P., GEORGE A.L., HORN R. Functional expression and properties of the human skeletal muscle sodium channel. Pflügers Arch. 1994b;427:136–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00585952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAHINE M., GEORGE A.L., ZHOU M., JI S., SUN W., BARCHI R.L., HORN R. Sodium channel mutations in paramyotonia congenita uncouple inactivation from activation. Neuron. 1994a;12:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAN Z., GEORGE A.L., KYLE J.W., MAKIELSKI J.C. Two human paramyotonia congenita mutations have opposite effects on lidocaine block of Na+ channels expressed in a mammalian cell line. J. Physiol. Lond. 1996;496:275–286. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAHAM F.L., VAN DER EB A.J. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology. 1973;52:456–467. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAESELER G., LEUWER M., KAVAN J., WÜRZ A., DENGLER R., PIEPENBROCK S. Voltage-dependent block of normal and mutant muscle sodium channels by 4-chloro-m-cresol. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:1259–1267. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILL O.P., MARTY A., NEHER E., SAKMANN B., SIGWORTH F.J. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWAMOTO T., KOGA M,. , MURATA K., MATSUDA S., KODAMA Y. Effects of ALDH2, CYP1A1, and CYP2E1 genetic polymorphisms and smoking and drinking habits on toluene metabolism in humans. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1995;133:295–304. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIMURA E.T., DARBY T.D., KRAUSE R.A., BRONDYK H.D. Parenteral toxicity studies with benzyl alcohol. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1971;18:50–68. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(71)90315-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEHMANN-HORN F., RUDEL R. Hereditary nondys-trophic myotonias and periodic paralyses. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 1995;8:402–410. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199510000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOPEZ-HERCE J. Benzyl alcohol poisoning following diazepam intravenous infusion. Ann. Pharmacother. 1995;29:632. doi: 10.1177/106002809502900616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCLOSKEY S.E., GERSHANIK J.J., LERTORA J.J.L., WHITE L.A., GEORGE W.J. Toxicity of benzyl alcohol in adult and neonatal mice. J. Pharm. Sci. 1986;75:702–705. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600750718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MESSIHA F.S. Benzyl alcohol adverse effects in the rat: implications for toxicity as a perservative in parenteral injectable solutions. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. 1991;99:445–449. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(91)90269-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITROVIC N., GEORGE A.L., HEINE R., WAGNER S., PIKA U., HARTLAUB U., ZHOU M., LERCHE H., FAHLKE C., LEHMANN-HORN F. K+-aggravated myotonia: destabilization of the inactivated state of the human muscle sodium channel by the V1589M mutation. J. Physiol. Lond. 1994;478:395–402. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONTAGUTI P., MELLONI E., CAVALLETTI E. Acute intravenous toxicity of dimethyl sulfoxide, polythylene glycol 400, dimethylformamide, absolute ethanol, and benzyl alcohol in inbred mouse strains. Arzneim. Forsch. 1994;44:566–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NUTTALL G.A., BARNETT M.R., SMITH R.L., BLUE T.K., CLARK K.R., PAYTON B.W. Establishing intravenous access: a study of local anesthetic efficacy. Anesth. Analg. 1993;77:950–953. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199311000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUGSLEY M., GOLDIN A. Molecular analysis of the Na+ channel blocking actions of the novel class I anti-arrythmic agent RSD 921. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:9–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUGSLEY M.J., GOLDIN A.L. Effect of bisaramil, a novel class I antiarrythmic agent, on heart, skeletal muscle and brain Na+ channels. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;342:93–104. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01420-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUAN C., MOK W.M., WANG G.K. Use-dependent inhibition of Na+ currents by benzocaine homologs. Biophys. J. 1996;70:194–201. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79563-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAGSDALE D.S., MCPHEE J.C., SCHEUER T., CATTERALL W.A. Molecular determinants of state-dependent block of Na+ channels by local anesthetics. Science. 1994;265:1724–1728. doi: 10.1126/science.8085162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAH R.L., TSUSHIMA R.G., BACKX P.H. Effects of local anesthetics on Na+ channels containing the equine hyperkalemic periodic paralysis mutation. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:C389–C400. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEARER G.L., KIM K., LEE K.M., WANG C.K., PLAPP B.V. Alternative pathways and reactions of benzyl alcohol and benzaldehyde with horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11186–11194. doi: 10.1021/bi00092a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH-KIELLAND A., RIPEL A. Toluene metabolism in isolated rat hepatocytes: effects of in vivo pretreatment with acetone and phenobarbital. Arch. Toxicol. 1992;67:107–112. doi: 10.1007/BF01973680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAHASHI M.P., CANNON S.C. Enhanced slow inactivation by V445M: a sodium channel mutation associated with myotonia. Biophys. J. 1999;76:861–868. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77249-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VEDANTHAM V., CANNON S.C. The position of the fast-inactivation gate during lidocaine block of voltage-gated Na+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999;113:7–16. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAGNER S., LERCHE H., MITROVIC N., HEINE R., GEORGE A.L., LEHMANN-HORN F. A novel sodium channel mutation causing a hyperkalemic paralytic and paramyotonic syndrome with variable clinical expressivity. Neurology. 1997;49:1018–1025. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.4.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILSON L., MARTIN S. Benzyl alcohol as an alternative local anesthetic. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1999;33:495–499. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70335-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WRIGHT S.N., WANG S.Y., KALLEN R.G., WANG G.K. Differences in steady-state inactivation between Na channel isoforms affect local anaesthetic binding affinity. Biophys. J. 1997;73:779–788. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78110-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG N., JI S., ZHOU M., PTACEK L.J., BARCHI R.L., HORN R., GEORGE A.L. Sodium channel mutations exhibit similar biophysical phenotypes in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:12785–12789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]