Abstract

In isolated rat uterine strips, adrenomedullin (AM) inhibited the spontaneous periodic contraction in a concentration-dependent manner (IC50=22.3±0.7 nM). The inhibitory effect of AM was prevented by either AM22–52, a putative antagonist for AM receptors, or calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)8–37, a putative antagonist for CGRP receptors. AM also attenuated bradykinin (BK)-induced periodic uterine contraction, which was blocked by AM22–52 or CGRP8–37, whereas AM had no effect on the periodic contraction caused by oxytocin or prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α). RT–PCR analysis showed that mRNAs for calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CRLR), receptor-activity-modifying protein (RAMP)1, RAMP2 and RAMP3 were expressed in the rat uterus. These results demonstrate that AM selectively inhibits spontaneous and BK-induced periodic contraction via activating receptors for AM and CGRP.

Keywords: Adrenomedullin, uterine contraction, calcitonin receptor-like receptor, receptor-activity-modifying protein

Introduction

Adrenomedullin (AM), originally isolated from human pheochromocytoma as a hypotensive peptide (Kitamura et al., 1993), is widely distributed in various tissues, and plays multiple roles in the regulation of a variety of physiological functions (Kitamura & Eto, 1997; Cameron & Fleming, 1998). AM, consisting of 52 amino acids, shares the amino terminal ring structure and the carboxyl terminal amide structure with calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a vasodilating peptide (Kitamura et al., 1993). Receptors for AM and CGRP have been cloned in human neuroblastoma; combination of calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CRLR) with receptor-activity-modifying protein (RAMP)2 or RAMP3 produces receptor for AM, while combination of CRLR with RAMP1 produces that for CGRP (McLatchie et al., 1998; Foord & Marshall, 1999). AM has been shown to stimulate not only AM receptors but also CGRP receptors (Fraser et al., 1999).

AM and AM mRNA are highly expressed in the female reproductive system, such as posterior pituitary gland, uterus (Upton et al., 1997; Cameron & Fleming, 1998; Makino et al., 1999), and various foetoplacental tissues (Macri et al., 1996; Marinoni et al., 1998; Yotsumoto et al., 1998; Makino et al., 1999). Upton et al. (1997) reported that high concentration of AM (5 μM) inhibited tonic uterine contraction caused by galanin via activation of CGRP receptors, while the biological role of AM in the control of periodic uterine contraction remains elusive.

In the present study, to clarify the role of AM in the female reproductive system, we examined the effects of AM on periodic uterine contraction, and the expression of receptor for AM in rat uterus.

Methods

Isolation of uterine strips

onpregnant Sprague Dawley rats (8–12 weeks old, 230–280 g body weight) were given food and water ad libitum, and housed at 22°C with 50% humidity and a 12 h light/dark cycle. The rats were injected subcutaneously 1 μg 17β-oestradiol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) dissolved in 0.2 ml of 30% ethanol; oestradiol was administered to synchronize the menstrual cycle and to obtain a spontaneous periodic contraction of myometrium (Bek et al., 1988). After 24 h, uterine horns were isolated under pentobarbital anaesthesia (60 mg kg−1, i.p. injection), and divided by a transverse cut into four segments of an equal length in modified Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate (KRB) solution (mM): NaCl 122, KCl 5, CaCl2 2.4, MgSO4 1, NaHCO3 26, EDTA 0.03, and dextrose 11, pH 7.4. Each segment was cut along the mesosalpinx insertion, and placed in a tissue chamber filled with 30 ml modified KRB solution under bubbled of 95% O2/5% CO2 at 37°C.

In vitro contractility measurements

Four strips prepared from the same uterus were used to examine the effects of test compounds on myometrial contractility in parallel. The contractility of uterine strip was monitored by an isotonic transducer (Nihon Kohden, TD-112S, Japan) with 1 g tension, and recorded on a polygraph (Rikadenki, R-62, Japan). After a 40 min equilibrium of the spontaneous periodic contraction, the strip was preincubated with or without 1 μM AM22–52, a putative antagonist for AM receptors (Eguchi et al., 1994), or 1 μM CGRP8–37, a putative antagonist for CGRP receptors (Chiba et al., 1989), for 15 min, and exposed to 1–100 nM AM in a cumulative manner. In a separate experiment, uterine contraction was caused by 1 nM oxytocin, 1 μM prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α), or 10 nM bradykinin (BK), and the effects of 100 nM AM on the uterine contraction were examined in the absence or presence of AM22–52 or CGRP8–37. Uterine strips were finally contracted by 45 mM KCl to confirm the uterine responsiveness. Peptides were obtained from Peptide Institute (Osaka, Japan).

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) of AM and CGRP receptors

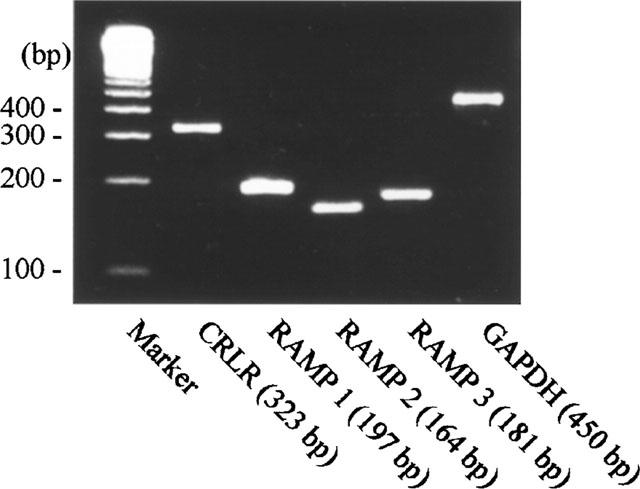

Total RNA was extracted from rat uterus using TRIzolTM (Life Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) and RT–PCR was performed with a thermal cycler (Perkin Elmer Corp., Norwalk, CT, U.S.A.) using a RT–PCR kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). According to the published sequences appeared in GenBank, we constructed primers specific for rat CRLR and RAMP1-3 as follows; CRLR (L27487), 5′-CCAAACAGACTTGGGAGTCACTAGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTGTCTTCTCTTTCTCATGCGTGC-3′ (reverse), RAMP1 (AB028933), 5′-CACTCACTGCACCAAACTCGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGTCATGAGCAGTGTGACCGTAA-3′ (reverse), RAMP2 (AF162778) 5′-AGGTATTACAGCAACCTGCGGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACATCCTCTGGGGGATCGGAGA-3′ (reverse), RAMP3 (AB028935) 5′-ACCTGTCGGAGTTCATCGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACTTCATCCGGGGGGTCTTC-3′ (reverse). The predicted sizes of PCR products using each primer pair are shown in Figure 3. PCR was performed using the following conditions: 30 cycles of 94°C 30 s, 60°C 30 s, and 72°C 90 s. At the end of PCR, samples were kept at 72°C for 10 min for final extension. The amplification products were separated by electrophoresis (2% agarose gel) and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The PCR products were cut from agarose gel, purified by QIA quick gel extraction kit (Qiagen Gmbh, Hilden, Germany). The nucleotide sequence was determined by ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.).

Figure 3.

Expression of mRNA for CRLR, RAMPs in rat uterus. RT–PCR products of CRLR and RAMPs were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. The DNA size marker was 100 bp ladder as shown on the left. The predicted sizes of RT–PCR products are shown at the bottom.

Statistics

Data (mean±s.e.mean) were evaluated statistically of two-way ANOVA or one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons using the Dunnett's test.

Results

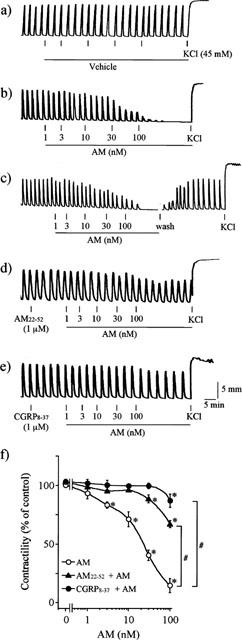

Uterine strips isolated from oestrogenized rats spontaneously contracted in a periodic manner (Figure 1a). Bath application of AM, in a cumulative fashion, inhibited the spontaneous periodic contraction in a concentration-dependent manner (IC50=22.3±0.7 nM) (Figure 1b,c,f), whereas the addition of vehicle alone had no effect (Figure 1a). The inhibitory effect of AM was reversible upon washout, even when the myometrium was completely relaxed by 100 nM AM (Figure 1c). Preincubation with either 1 μM AM22–52 or 1 μM CGRP8–37 had no effect per se, but prevented the relaxing effects of 1–100 nM AM (Figure 1d–f) AM had no effect on high K+-induced tonic contraction (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Effects of AM on spontaneous periodic contraction. Uterine strips of oestrogenized rats were treated with (a) vehicle; (b,c) AM; (d) AM22–52+AM; (e) CGRP8–37+AM. Typical recordings from five separate experiments with similar results were shown. (f) effect of AM22–52 or CGRP8–37 on the AM-induced inhibition of the contraction. *P<0.05, compared with the response without any peptide (one-way ANOVA); #P<0.05, compared with AM alone (two-way ANOVA).

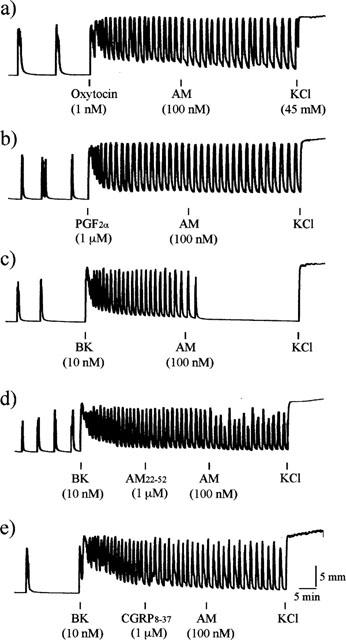

We then examined the effects of AM on periodic uterine contraction caused by oxytocin, PGF2α or BK. In uterine strips of non-oestrogenized rats, they contracted spontaneously with variable intervals and amplitudes (Figure 2a–e). Either 1 nM oxytocin (Figure 2a), 1 μM PGF2α (Figure 2b), or 10 nM BK (Figure 2c) significantly stimulated the contractility. AM, at 100 nM, completely blocked the BK-induced contraction (Figure 2c) whereas it had no effect on the oxytocin- or PGF2α-induced periodic contraction even at 100 nM (Figure 2a,b). The inhibitory effect of AM on BK-induced periodic contraction was substantially prevented by preincubation of AM22–52 or CGRP8–37 (Figure 2d,e). The inhibitory effect of AM on BK-induced periodic uterine contraction was also observed in uterine strips of oestrogenized rats (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effects of AM on periodic contraction caused by oxytocin, PGF2α or BK. Uterine strips of non-oestrogenized rats were pretreated with (a) oxytocin; (b) PGF2α; (c–e) BK and further treated with (a–c) AM; (d) AM22–52+AM; (e) CGRP8–37+AM. Typical recordings from five separate experiments with similar results were shown.

RT–PCR analysis showed that rat uterus expressed mRNAs for CRLR, RAMP1, RAMP2, and RAMP3. The PCR products were sequenced and found to be identical to the reported sequences of the rat CRLR and RAMPs (Figure 3).

Discussion

Our main finding is that AM reversibly inhibits spontaneous periodic uterine contraction in a concentration-dependent manner. Thus our finding demonstrates that AM has a regulatory function in female reproductive system as a modulator of uterine contractility.

We also observed that AM inhibited BK-induced periodic uterine contraction, while it did not affect oxytocin- or PGF2α-induced periodic and high K+-induced tonic contraction. These results suggest that AM does not have an active dilatory effect on myometrium. The inhibitory effect of AM could be operated by the prevention of mechanism(s) for spontaneous and/or BK-induced periodic contractions.

The inhibitory effect of AM on the periodic uterine contraction was antagonized by AM22–52 or CGRP8–37, suggesting that AM reacted with receptors for AM and CGRP. In addition, our RT–PCR experiments showed that rat uterus expressed mRNAs for CRLR, RAMP1, RAMP2 and RAMP3, although we cannot exclude the possibility that mRNAs for CRLR or RAMPs may come from blood vessels in the uterus. Collectively, our results suggest that rat uterus possesses both AM receptors and CGRP receptors both of which are reactive to AM (Fraser et al., 1999). Our results are in agreement with those of previous report in which both 125I-AM binding and 125I-CGRP binding were entirely displaced by AM in membrane fraction prepared from rat uterus (Upton et al., 1997). Although AM22–52 is generally accepted as an antagonist for AM receptors (Eguchi et al., 1994; McLatchie et al., 1998), it is reported to suppress CGRP (but not AM)-induced vascular dilation in cat hindlimb (Champion et al., 1997). If AM22–52 is acting on CGRP receptors, AM might act via CGRP receptors in the rat uterus.

Levels of AM peptide and mRNA in rat uterus are as high as those in adrenal medulla (Upton et al., 1997; Cameron & Fleming, 1998). In human and rat uterus, AM is mainly located in the endometrium (Cameron & Fleming, 1998; Michishita et al., 1999). These findings suggest that AM may act on the myometrium in a paracrine manner.

It has become evident that levels of AM, AM receptors and CGRP receptors significantly increase during pregnancy in various maternal and foetal tissues. Abundance of AM mRNA in uterus increased 1.8 to 4.5 fold during pregnancy (Upton et al., 1997; Makino et al., 1999). Immunohistochemical analyses showed that trophoblast giant cells in placenta produced a large amount of AM, and secreted it into the surrounding maternal and foetal tissues (Yotsumoto et al., 1998). In pregnant rat uterus, AM binding sites and CGRP binding sites were increased by 10 and 4 fold, respectively (Upton et al., 1997; Dong et al., 1998), whereas the amount of CGRP peptide decreased to undetectable level (Upton et al., 1997). These findings suggest that the increased binding sites of AM and CGRP as well as the increased local production of AM, but not CGRP, in pregnant uterus play a crucial role in the maintenance of uterine quiescence.

In the present study, AM selectively inhibits BK induced, but not oxytocin- or PGF2α-induced periodic uterine contraction. The abnormal expression of BK, an autacoid causing inflammatory responses (De La Cadena et al., 1991), has been implicated in triggering infection-driven preterm labour (Schrey et al., 1992), whereas oxytocin- or PGF2α-induced uterine contraction is generally thought to be involved in normal labour. These findings imply that AM selectively inhibits preterm contraction caused by BK, and it might contribute to the maintenance of pregnancy without interfering normal labour promoted by oxytocin or PGF2α.

Acknowledgments

Technical and secretarial assistance by Ms Keiko Kawabata and Mr Keizo Masumoto is appreciated. This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, Japan.

Abbreviations

- AM

adrenomedullin

- BK

bradykinin

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CRLR

calcitonin receptor-like receptor

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- PG

prostaglandin

- RAMP

receptor-activity-modifying protein

- RT–PCR

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

References

- BEK T., OTTESEN B., FAHRENKRUG J. The effect of galanin, CGRP and ANP on spontaneous smooth muscle activity of rat uterus. Peptides. 1988;9:497–500. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(88)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMERON V.A., FLEMING A.M. Novel sites of adrenomedullin gene expression in mouse and rat tissues. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2253–2264. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.5.5965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAMPION H.C., SANTIAGO J.A., MURPHY W.A., COY D.H., KADOWITZ P.J. Adrenomedullin-(22-52) antagonizes vasodilator responses to CGRP but not adrenomedullin in the cat. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:R234–R242. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.1.R234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIBA T., YAMAGUCHI A., YAMATANI T., NAKAMURA A., MORISHITA T., INUI T., FUKASE M., NODA T., FUJITA T. Calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist human CGRP-(8-37) Am. J. Physiol. 1989;256:E331–E335. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1989.256.2.E331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE LA CADENA R.A., LASKIN K.J., PIXLEY R.A., SARTOR R.B., SCHWAB J.H., BACK N., BEDI G.S., FISHER R.S., COLMAN R.W. Role of kallikrein-kinin system in pathogenesis of bacterial cell wall-induced inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;260:G213–G219. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1991.260.2.G213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DONG Y-L., GANGULA P.R.R., FANG L., WIMALAWANSA S.J., YALLAMPALLI C. Uterine relaxation responses to calcitonin gene-related peptide and calcitonin gene related peptide receptors decreased during labor in rats. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998;179:497–506. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70386-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EGUCHI S., HIRATA Y., IWASAKI H., SATO K., WATANABE T.X., INUI T., NAKAJIMA K., SAKAKIBARA S., MARUMO F. Structure-activity relationship of adrenomedullin, a novel vasodilatory peptide, in cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Endocrinology. 1994;135:2454–2458. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.6.7988431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOORD S.M., MARSHALL F.H. RAMPs: accessory proteins for seven transmembrane domain receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:184–187. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRASER N.J., WISE A., BROWN J., MCLATCHIE L.M., MAIN M.J., FOORD S.M. The amino terminus of receptor activity modifying proteins is a critical determinant of glycosylation state and ligand binding of calcitonin receptor-like receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;55:1054–1059. doi: 10.1124/mol.55.6.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAMURA K., ETO T. Adrenomedullin–physiological regulator of the cardiovascular system or biochemical curiosity. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 1997;6:80–87. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199701000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAMURA K., KANGAWA K., KAWAMOTO M., ICHIKI Y., NAKAMURA S., MATSUO H., ETO T. Adrenomedullin: a novel hypotensive peptide isolated from human pheochromocytoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;192:553–560. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACRI C.J., MARTINEZ A., MOODY T.W., GRAY K.D., MILLER M-J., GALLAGHER M., CUTTITTA F. Detection of adrenomedullin, a hypotensive peptide, in amniotic fluid and fetal membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996;175:906–911. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)80023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAKINO I., SHIBATA K., MAKINO Y., KANGAWA K., KAWARABAYASHI T. Adrenomedullin attenuates the hypertension in hypertensive pregnant rats induced by NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;371:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARINONI E., DI IORIO R., LETIZIA C., VILLACCIO B., SCUCCHI L., COSMI E.V. Immunoreactive adrenomedullin in human fetoplacental tissues. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998;179:784–787. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLATCHIE L.M., FRASER N.J., MAIN M.J., WISE A., BROWN J., THOMPSON N., SOLARI R., LEE M.G., FOORD S.M. RAMPs regulate the transport and ligand specificity of the calcitonin-receptor-like receptor. Nature. 1998;393:333–339. doi: 10.1038/30666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICHISHITA M., MINEGISHI T., ABE K., KANGAWA K., KOJIMA M., IBUKI Y. Expression of adrenomedullin in the endometrium of the human uterus. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;93:66–70. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHREY M.P., MONAGHAN H., HOLT J.R. Interaction of paracrine factors during labour: Interleukin-1β causes amplification of decidua cell prostaglandin F2α production in response to bradykinin and epidermal growth factor. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes Essent. Fatty Acids. 1992;45:137–142. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(92)90230-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UPTON P.D., AUSTIN C., TAYLOR G.M., NANDHA K.A., CLARK A.J.L., GHATEI M.A., BLOOM S.R., SMITH D.M. Expression of adrenomedullin (ADM) and its binding sites in the rat uterus: increased number of binding sites and ADM messenger ribonucleic acid in 20-day pregnant rats compared with nonpregnant rats. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2508–2514. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.6.5186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOTSUMOTO S., SHIMADA T., CUI C.-Y., NAKASHIMA H., FUJIWARA H., KO M.S.H. Expression of adrenomedullin, a hypotensive peptide, in the trophoblast giant cells at the embryo implantation site in mouse. Dev. Biol. 1998;203:264–275. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]