Abstract

We studied the effects of the novel Na+/Ca2+ exchange inhibitor KB-R7943, 2-[2-[4-(4-nitrobenzyloxy)phenyl]ethyl]isothiourea methanesulphonate, on the native nicotinic receptors present at the bovine adrenal chromaffin cells, as well as on rat brain α3β4 and α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

As expected, KB-R7943 blocked the Na+-gradient dependent 45Ca2+ uptake into chromaffin cells (IC50 of 5.5 μM); but in addition, the compound also inhibited the 45Ca2+ entry and the increase of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, [Ca2+]c, stimulated by 5 s pulses of ACh (IC50 of 6.5 and 1.7 μM, respectively).

In oocytes expressing α3β4 and α7 nicotinic AChRs, voltage-clamped at −60 mV, inward currents elicited by 1 s pulses of 100 μM ACh (IACh) were blocked by KB-R7943 with an IC50 of 0.4 μM and a Hill coefficient of 0.9.

Blockade of α3β4 currents by KB-R7943 was noncompetitive; moreover, the blocker (0.3 μM) became more active as the ACh concentration increased (34 versus 66% blockade at 30 μM and 1 mM ACh, respectively).

Inhibition of α3β4 currents by 0.3 μM KB-R7943 was more pronounced at hyperpolarized potentials. If given within the ACh pulse (10 μM), the inhibition amounted to 33, 64 and 80% in oocytes voltage-clamped at −40, −60 and −100 mV, respectively. The onset of blockade was faster and the recovery slower at −100 mV; the reverse was true at −40 mV.

In conclusion, KB-R7943 is a potent blocker of nicotinic AChRs; moreover, it displays many features of an open-channel blocker at the rat brain α3β4 AChR. These results should be considered when KB-R7943 is to be used to study Ca2+ homeostasis in cells expressing nicotinic AChRs and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger.

Keywords: KB-R7943, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, α3β4 nicotinic AChRs, α7 nicotinic AChRs, Xenopus oocytes, chromaffin cells

Introduction

Bovine adrenal chromaffin cells of adrenal medulla express a major isoform of the NCX1 clone encoding for the plasmalemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (Pan et al., 1998); this isoform is also expressed at high levels in the heart and in the brain (Komuro et al., 1992). Several studies from our and other laboratories have implicated this transporter in the control of the cytosolic concentration of Ca2+, [Ca2+]c, and hence, in the exocytotic release of catecholamines from adrenal medulla (Esquerro et al., 1980; García et al., 1981a,1981b; Liu & Kao, 1990; Chern et al., 1992; Lin et al., 1994; Pan & Kao, 1997). Attempts to clarify the participation of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in physiological and pathological processes of different cell types have been hampered by the lack of potent and selective blockers of this carrier. A number of compounds have been reported as inhibitors, but at concentrations that also block many other transporters and ion channels (García et al., 1988; Slaughter et al., 1988; Kaczorowski et al., 1989; Kleyman & Cragoe, 1988; Murphy et al., 1991; Iwamoto & Shigekawa, 1998).

A novel isothiourea derivative, KB-R7943, has recently been introduced; at low micromolar concentrations, the compound preferentially inhibits the reverse mode of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in ventricular cells or in fibroblasts transfected with the cardiac NCX1 clone (Iwamoto et al., 1996; Watano et al., 1996). The interaction between KB-R7943 and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger seems to be quite selective since the compound shows a low potency for other cell membrane transporters or channels so far tested, such as the Na+/H+ exchanger, the voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channel, or the inward rectifier K+ channel.

In the light of this interesting profile, we decided to use KB-R7943 as a pharmacological tool to further explore the role of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in regulating Ca2+ homoestasis in chromaffin cells, in resting or in depolarizing conditions. Preliminary results corroborated that KB-R7943 was indeed a potent inhibitor of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, also in this neuronal cell type. However, we discovered that the compound was also an efficient blocker of the 45Ca2+ uptake and [Ca2+]c rise induced by the stimulation of the cells with acetylcholine (ACh), but not with high K+. These findings suggested that the compound is probably blocking native nicotinic ACh receptors (AChR) present in bovine chromaffin cells, which most likely belong to the α3β4 and α7 subtypes (Criado et al., 1992; 1997; García-Guzmán et al., 1995; Campos-Caro et al., 1997; López et al., 1998). Hence, to know the mechanism of nicotinic AChR blockade by KB-R7943, we used a direct approach, namely the study of ACh-evoked currents in oocytes injected with the rat brain nicotinic α3β4 and α7 subunits of the AChR. We present here the results of such studies, performed in bovine chromaffin cells and in oocytes.

Methods

Preparation and culture of chromaffin cells

Bovine adrenal chromaffin cells were isolated following standard methods (Livett, 1984) with some modifications (Moro et al., 1990). Cells were suspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% foetal calf serum, 50 IU ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin. Cells were kept in a water-saturated incubator at 37°C, in a 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere, and used 2–4 days thereafter. For 45Ca2+ uptake experiments, cells were plated at a density of 2×105 cells/well in 96-multiwells plates.

Measurements of 45Ca2+ uptake into chromaffin cells

45Ca2+ uptake studies were carried out in cells after 2–4 days in culture as has been described previously (Villarroya et al., 1999). Before the experiment, cells were washed twice with a Krebs-N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethane-sulphonic acid (HEPES) solution containing (in mM): NaCl 140, KCl 5.9, MgCl2 1.2, CaCl2 1, glucose 11, HEPES 10, at pH 7.4 and maintained at 37°C. Then, 45Ca2+ uptake was initiated by incubation of the cells with 45Ca2+ at a final concentration of 2.5 μCi ml−1 prepared in a Krebs-HEPES solution (basal uptake, in a high-K+ solution (Krebs-HEPES containing 70 mM KCl with isosmotic reduction of NaCl) or in a 100 μM ACh Krebs-HEPES solution. This incubation was carried out during 5 s, and at the end of this period, the medium was rapidly aspirated and the reaction was stopped by addition of cold Ca2+-free Krebs-HEPES solution containing 10 mM LaCl3. Finally, cells were washed five times with a Ca2+-free Krebs-HEPES solution containing 10 mM LaCl3 and 2 mM ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA). Experiments studying the effect of KB-R7943 on 45Ca2+ uptake were carried out by preincubation of the cells with the appropriate concentration of the compound, added 10 min before and during the ACh or high K+ stimulation period.

In order to measure the 45Ca2+ uptake induced by the gradient of cytosolic Na+ [Na+]c (Na+/Ca2+ exchanger working in reverse), cells were first loaded with Na+ in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. Cells were maintained during 40 min with a nominal Ca2+ free Krebs-HEPES solution containing ouabain (10−4 M) to inhibit Na+ pumping, and during the last 10 min, carbachol (10−4 M) was also added to the ouabain medium to increase the Na+ loading of the cell (Wada et al., 1986). After this period, while carbachol was washed out, different concentrations of KB-R7953 were added to the above ouabain solution for an additional 10 min period. To assay the reverse Na+/Ca2+ exchanger activity, the Krebs-HEPES solution was replaced by a modified Na+-free Krebs-HEPES solution prepared by substituting NaCl by an equiosmotic concentration of N-methyl-D-glucamine. Then, the Na+-dependent 45Ca2+ uptake was initiated by incubation of the cells (during 10 min) with a solution containing 40Ca2+ (1 mM) plus 45Ca2+ as a tracer (2.5 μCi ml−1). At the end of this period, the medium was rapidly aspirated, the reaction stopped, and cells were washed as described above.

To measure the radioactivity retained, the cells were scraped with a plastic pipette tip after the addition of a trichloroacetic acid solution (10%), and later 3.5 ml of scintillation fluid (Ready Micro, Beckman); samples were counted in a Packard beta counter. Results are expressed as counts per minute or normalized as percentage of 45Ca2+ taken up by stimulated cells in the absence of KB-R7943, after substraction of the basal uptake.

Measurement of [Ca2+]c changes in single chromaffin cell

For the measurements of [Ca2+]c, cells were plated on 25 mm-diameter glass coverslips at a density of 5.103 cells ml−1. Cells of 2–4 days old were loaded with fura 2-acetoxymethyl ester (2.5 μM for 40 min at 37°C in the incubator). Then, the cells were washed twice with Krebs-HEPES solution containing (in mM): NaCl 140, KCl 5.9, MgCl2 1.2, CaCl2 2, glucose 11 and HEPES 10, at pH 7.4. Cells were kept for 10 min at 37°C in the incubator before being placed on the stage of an inverted microscope on a chamber, allowing their continuous superfusion with Krebs-HEPES solution, at room temperature (22±3°C). Pulses of ACh or high K+ (5 s) were applied at regular intervals using a fast superfusion device system. Single cell fluorescence measurements were performed by exciting the fura 2-loaded cells with alternating 360- and 390 nm filtered light. The apparent [Ca2+]c was calculated from the ratio of the fluorescent signal (ratio of short to long wavelengths) according to Grynkiewicz et al. (1985); calibration constants were experimentally determined as described by Neher (1995). Experimental fluorescence data were sampled every 0.5 s by a computer, which continuously provided the [Ca2+]c values in micromolar.

Preparation of RNA and injection of Xenopus oocytes

Techniques for mRNA preparation upon in vitro transcription of the corresponding cDNAs, oocytes injection and electrophysiological recordings of the expressed foreign receptors have been described previously (Miledi et al., 1989; Montiel et al., 1997; Herrero et al., 1999). The plasmids pPCA48E, pZPC13 and pHIP306, containing the entire coding regions of rat brain nicotinic AChR α3, β4, and α7 subunits, were linearized and transcribed with the corresponding polymerase using a mCAP RNA capping kit (Stratagene C.S., La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.).

Mature female Xenopus laevis frogs obtained from CRBM du CNRS, (Montpellier, France) were anaesthetized with tricaine solution (0.125%) and ovarian lobes dissected out. Then, follicle-enclosed oocytes were manually stripped from the ovary membranes and incubated overnight at 16°C in a modified Barth's solution containing (in mM): NaCl 88, KCl 1, NaHCO3 2.4, MgSO4 0.82, Ca(NO3)2 0.33, CaCl2 0.41, HEPES 10, buffered to pH 7.4 and supplemented with gentamycin (0.1 mg ml−1) and sodium pyruvate (5 mM). The next day, healthy follicle-enclosed oocytes were injected with 50 nl (50 ng) of α7 RNA or 50 nl (25 : 25 ng) of α3:β4 RNAs using a nanoject automatic injector (Drummond Scientific Co., Broomall, PA, U.S.A.). One day later, oocytes were defolliculated by collagenase treatment. Electrophysiological recordings were made 2–5 days after RNA injection.

Electrophysiological recordings of ACh currents in oocytes

Experiments were carried out at room temperature (22–25°C) in Ringer's solution containing (in mM): NaCl 115, KCl 2, CaCl2 1.8, HEPES 5, buffered to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Membrane currents were recorded with a two-electrode voltage clamp amplifier (OC-725-B Warner Instrument Corporation, Hamden, CT, U.S.A.) using microelectrodes with resistances of 0.5–5 MΩ made from borosilicate glass (GC100TF-15, Clark Electromedical, Pangbourne, U.K.) and filled with KCl (3 M). The holding potential in all experiments was −60 mV, except in those performed to study the voltage-dependent effects of KB-R7943. Single oocytes were held in a 0.3 ml-volume chamber and constantly superfused with Ringer's solution by gravity (4 ml min−1). The volume in the chamber was maintained constant using the reverse suction of one air pump. Solutions containing ACh, KB-R7943 or both compounds were applied with the use of a set of 2 mm diameter glass tubes located close to the oocyte. Voltage protocols, ACh pulses and data acquisition were controlled using a Digidata 1200 Interface and the CLAMPEX software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.).

Flash photolysis of caged Ca2+ in oocytes

These experiments, designed to directly activate the native Ca2+-dependent chloride current [ICl(Ca)] in the oocyte, were performed as described previously (Montiel et al., 1997). Oocytes were injected with 41 nl of the caged-Ca2+ solution containing 50 nM DM-nitrophen, 45 mM CaCl2, 5 mM HEPES at pH 7; injection was made into the animal hemisphere, at latitudes of 20–40°, so as to maximize Ca2+-activated chloride currents (Miledi & Parker, 1984). After equilibrium in the dark for at least 30 min, individual oocytes were voltage-clamped at −60 mV. The light source was a high intensity xenon flashlamp system (Cairn Research Ltd., Faversham, Kent, U.K.). Ultraviolet light was focused onto the oocyte surface using a light guide positioned over the vegetal pole. The capacitance value used was 2000 μF charged to 200 V. Repetitive flashes of constant intensity and duration were given to the oocyte every 4 min; flashes were controlled by a PC computer using the CLAMPEX software. Under these experimental conditions, caged-Ca2+ injected oocytes gave reproducible ICl(Ca) responses upon repetitive light flashes.

Materials and solutions

All products not specified were purchased from SIGMA (Madrid, Spain). KB-R7943, 2-[2-[4-(4-nitrobenzyloxy)phenyl]ethyl]isothiourea methanesulphonate), was synthesized by Pharmaceutical Research Laboratories, Kanebo Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). For chromaffin cell experiments, collagenase type A from Clostridium histolyticum (Boehringer-Mannheim, Madrid, Spain); DMEM, foetal calf serum, penicillin and streptomycin (GIBCO); 45Ca2+ (specific activity 10–40 mCi mg−1 calcium, AMERSHAM). Scintillation fluid Ready micro (BECKMAN). KB-R7943 was prepared and stored as a stock DMSO solution (10−2 M). ω-Conotoxin MVIIC was purchased from Peptide Institute (Osaka, Japan). Experiments with nifedipine in chromaffin cells were performed under sodium lighting; the dihydropiridine was dissolved in ethanol and diluted in saline solutions to the desired concentration. For the experiments in oocytes, DM-nitrophen was purchased from Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, U.S.A. All compounds used were aliquoted and stored at −20°C as a concentrated stock solution. Final concentrations used in oocyte experiments were prepared in Ringer's solution.

Statistical analysis

Values of ACh concentration eliciting half maximal current (EC50), and KB-R7943 concentration eliciting 50% blockade of maximal current (IC50) and the Hill coefficient (nH) were estimated through non-linear regression analysis using the four-parameter logistic equation of the GraphPad Prism software, for a PC computer. To calculate the time constant for blockade (τon) of nicotinic currents by KB-R7943, as well as the recovery upon drug washout (τoff), records were fitted to a single exponential curve. Results are expressed as means±s.e.m. Differences between groups, for continuous variables with non normal distribution, were analysed by non-parameteric tests (Kruskal-Wallis, Wilcoxon), using the statistical SPSS software for a PC computer; values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Blockade by KB-R7943 of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in chromaffin cells

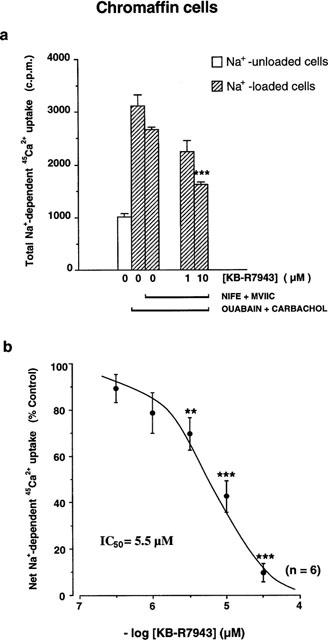

To assay the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger activity, Na+-loaded bovine chromaffin (2×105 cells−1) were incubated during 10 min with 45Ca2+ (see Methods); under these experimental conditions, the 45Ca2+ uptake amounted to 3100±150 c.p.m. (see Figure 1a), whereas the basal uptake value in Na+-unloaded cells reached only 1000±50 c.p.m.; individual values were obtained in quadruplicate from six different batches of cells. Under these conditions, it was likely that 45Ca2+ uptake was mostly due to the activation of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, that now works in the reverse mode. Nevertheless, to discard a component associated to voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in this 45Ca2+ uptake signal, new experiments were performed as above but, 10 min prior and during the 45Ca2+ incubation period, Na+-loaded cells were treated with 3 μM nifedipine (an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker)±3 μM ω-conotoxin MVIIC (an N-, P-, Q-subtypes Ca2+ channel blocker). These experimental conditions are known to fully block 45Ca2+ uptake through Ca2+ channels in depolarized chromaffin cells (Villarroya et al., 1997). Under these conditions, the [Na+]c-dependent 45Ca2+ uptake was reduced by 24% (Figure 1a). Hence, in the next experiments carried out to determine the blocking effects of KB-R7943 on the exchanger, chromaffin cells were always incubated in the presence of the Ca2+ channel blockers. In this manner, we ensured that all 45Ca2+ uptake measured occurred solely via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger working in reverse.

Figure 1.

Inhibition by KB-R7943 of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in bovine chromaffin cells. (a) Na+-dependent 45Ca2+ uptake (expressed in counts per minute−1, c.p.m.) initiated by the incubation of Na+-loaded cells (total uptake) or Na+-unloaded cells (basal uptake) with a Na+-free solution containing 45Ca2+. In all cases in which the effect of KB-7943 is assayed, Na+-loaded cells were incubated with nifedipine (NIFE, 0.3 μM) and ω-conotoxin MVIIC (MVIIC, 0.3 μM), to remove the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel component of the signal. Horizontal bars at the bottom indicated the different treatments of the cells. The effect of two different concentrations of KB-R7943 (1 and 10 μM) on the Na+-dependent 45Ca2+ uptake are shown. (b) Concentration-dependent inhibition by KB-R7943 of the 45Ca2+ uptake induced in Na+-loaded cells treated with Ca2+ channel blockers as above; values were obtained upon subtracting basal from total 45Ca2+ uptake, and expressed as percentage of the 45Ca2+ uptake in the absence of KB-R7943 (Control). Data are means±s.e.mean of six experiments performed in quadruplicate in different batches of cells. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with control uptake, in the absence of KB-R7943.

The threshold concentration inhibiting the exchanger was above 1 μM of KB-R7943; at 10 μM the inhibition rose to 60% (Figure 1a), and at 30 μM the compound suppressed fully the 45Ca2+ influx into chromaffin cells, in exchange for Na+ efflux. A full concentration-inhibition curve is shown in Figure 1b; the IC50 amounted to 5.5 μM.

Effects of KB-R7943 on other Ca2+ entry pathways in chromaffin cells

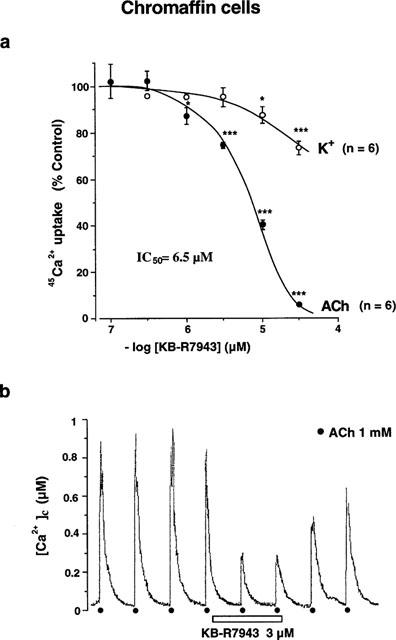

The 45Ca2+ uptake into chromaffin cells is strongly stimulated by cell depolarization, either directly with a high K+ concentration, or indirectly through nicotinic receptor activation (Villarroya et al., 1999). Using 2×105 cells−1, the 45Ca2+ uptake evoked by high K+ (70 mM K+, 5 s) amounted to 892±75 c.p.m., 5 fold the basal uptake (n=6 different batches of cells); this signal was affected little (26% blockade) by the highest concentration of KB-R7943 tested (30 μM). The 45Ca2+ uptake evoked by ACh (100 μM, 5 s) amounted to 829±79 c.p.m. 2×105 cells−1, about 4.6 fold the basal uptake (n=6 from different batches of cells); however, this signal was blocked by KB-R7943 in a concentration-dependent manner, showing and IC50 of 6.5 μM (Figure 2a). The preferential blockade by KB-R7943 of the ACh- over the K+-mediated 45Ca2+ uptake was additionally corroborated in experiments carried out in single chromaffin cells loaded with fura-2, assaying the effect of the drug on the [Ca2+]c rise. In these experiments, the cell was stimulated with successive pulses of ACh (1 mM, 5 s) or high K+ (70 mM, 5 s), applied at 2.5 min intervals, in the absence and later on in the presence of different concentrations of KB-R7943 (ranging from 0.1–30 μM); only one concentration of drug was assayed in each cell, and a minimum of three cells were tested for each concentration. Figure 2b shows a typical record of the [Ca2+]c signal evoked by ACh, and the inhibition exerted by 3 μM KB-R7943 (about 70% blockade). Under these experimental conditions, the IC50 value obtained for the ACh blockade by the compound was 1.7 μM. The [Ca2+]c rise evoked by high K+ was reduced only by 40±6% (n=4), in the presence of 30 μM KB-R7943.

Figure 2.

Effects of KB-R7943 on voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and on nicotinic receptors in bovine chromaffin cells. (a) The 45Ca2+ uptake was initiated by a brief exposure of the cells to a high K+ (70 mM, 5 s) or to ACh (100 μM, 5 s) medium containing 45Ca2+ (2.5 μCi ml−1) as a tracer. The effects of increasing concentrations of KB-R7943 on the 45Ca2+ uptake induced by both stimuli were expressed as percentage of control uptake (in the absence of the blocker, after subtracting basal from total 45Ca2+ uptake). In parentheses the number of experiments performed in different batches of cells (each value was obtained in quadruplicate from the same batch). (b) A typical record of the [Ca2+]c signal induced by successive ACh pulses (1 mM, 5 s), applied at 2.5 min intervals; in this particular cell, a concentration of 3 μM KB-R7943 was assayed. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with control uptake elicited by high K+ or ACh, in the absence of KB-R7943.

Effects of KB-R7943 on nicotinic α3β4 and α7 currents expressed in oocytes

In order to study in detail the selectivity and the mechanism of KB-R7943 blockade of nicotinic receptors, the following experiments were performed in oocytes expressing rat brain α3β4 and α7 nicotinic AChRs. Both receptors subtypes are highly homologous (above 90% homology) with their counterparts in bovine chromaffin cells, representing the two main nicotinic AChR subtypes expressed in these cells (Criado et al., 1992; García-Guzmán et al., 1995; Campos-Caro et al., 1997; López et al., 1998).

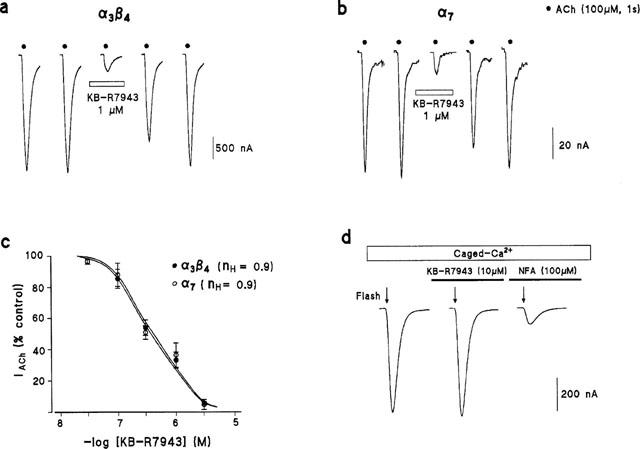

The protocols designed to study the effects of KB-R7943 on nicotinic AChRs expressed in oocytes implied the repeated pulsing of oocytes with ACh (at regular intervals), and the recording of the generated inward currents (IACh). After current stabilization, the effects of KB-R7943 on current amplitude was studied. For instance, in the experiments shown in Figure 3a,b, one typical α3β4- or α7-injected oocyte was stimulated several times with ACh pulses (100 μM, 1 s), applied at 1 min intervals. Using this stimulation protocol, reproducible currents were obtained for the two receptors expressed; the two first IACh traces in each figure were obtained after current stabilization. The addition of 1 μM KB-R7943 (present 1 min before and during the next ACh pulse) reduced α3β4 and α7 currents by 87 and 83%, respectively. In both cases, blockade was almost fully reversible upon washout of the drug for an additional 2 min.

Figure 3.

Blockade by KB-R7943 of rat brain α3β4 or α7 nicotinic currents (IACh) expressed in oocytes. (a) Shows the original IACh traces (recorded during 5 s) elicited by the application of successive ACh pulses (100 μM, 1 s), every 1 min, to an α3β4-injected oocyte, voltage-clamped at −60 mV. (b) Original IACh traces (recorded during 5 s) obtained in an α7-injected oocyte stimulated following the same pattern. In both cases, the third pulse of ACh was accompanied by KB-R7943 (1 μM), perfused from 1 min before and during the ACh pulse. (c) Shows the effects of increasing concentrations of KB-R7943 on α3β4 and α7 currents. Currents in the presence of the blocker were normalized as percentage of control peak IACh; data are means±s.e.mean of the results obtained in 4–8 oocytes. (d) An oocyte (out of four) injected with DM-nitrophen was exposed to three light flashes (arrows) applied at 4 min-intervals, to elicit ICl(Ca); the effects of KB-R7943 (10 μM) or niflumic acid (NFA, 100 μM) on ICl(Ca) are shown; each trace of the figure represent a period of 700 ms. Blockers were added since 1 min before and during the flash application.

Figure 3c shows the effects of increasing concentrations of KB-R7943 on α3β4 and α7 currents in several oocytes assayed as described above. Under these experimental conditions, the compound did not discriminate between both receptor subtypes; it exhibited a threshold of blockade in the nanomolar concentration range, a maximum effect in the low micromolar range, an IC50 of 0.4 μM and a Hill coefficient close to the unit (nH=0.9); four to eight oocytes were assayed for each concentration and receptor type.

Inward IACh measured in oocytes is mostly carried by Na+; however, Ca2+ also permeates these channels, particularly the α7 AChR (Seguela et al., 1993). Hence, Ca2+ entry through nicotinic AChRs could be coupled with ICl(Ca) activation and, therefore, the possibility existed that we were measuring the KB-R7943 effect on this last current. To explore this possibility, we performed a few experiments in oocytes loaded with DM-nitrophen-caged Ca2+ (see Methods); in these oocytes, the ICl(Ca) was directly recruited by cytosolic Ca2+ photoreleased from the caged-compound. Flashes of light, applied at 4 min intervals, elicited ICl(Ca) of reproducible amplitude. Figure 3d shows typical ICl(Ca) traces obtained in one oocyte (out of four) elicited by three consecutive flashes of light; current was not affected by 10 μM KB-R7943, a concentration above those used in the experiments performed in oocytes. Figure 3d also shows the effect of the well-known ICI(Ca) blocker niflumic acid (100 μM), which reduced ICl(Ca) by over 85%.

Blockade by KB-R7943 of the α3β4 currents induced by increasing concentrations of ACh

At this point, it was interesting to study the mechanism of nicotinic AChR blockade by KB-R7943. However, several reasons made such study particularly difficult in α7 currents. Thus, IACh through α7 AChRs faded off rapidly (1 s) in the presence of ACh, as compared with α3β4 currents (Papke & Heinemann, 1991; López et al., 1998; Herrero et al., 1999). Moreover, the experiments with α7 AChRs become particularly complicated and the interpretation of results difficult when high concentrations of ACh or long stimulation periods are required; on the other hand, the slow superfusion system in oocytes precluded the application of shorter ACh pulses. Thus, from now onwards, to study in detail the mechanism of receptor blockade by KB-R7943, the experiments will be performed in oocytes expressing α3β4 AChRs.

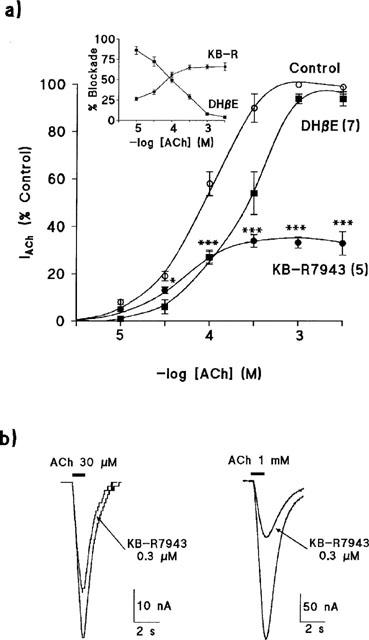

To know the nature of the receptor blockade by KB-R7943, α3β4 currents expressed in oocytes were activated by increasing concentrations of ACh (ranging from 10 μM to 3 mM) given as 1 s pulses every 1 min, to avoid receptor desensitization at the highest ACh concentrations used. Figure 4a shows the IACh curve obtained in the absence (control) or in the presence of two different blockers (KB-R7943 and dihydro-β-erythroidine). Results of control curve show that the amplitude of the IACh peaks increased as a function of the ACh concentration, the threshold ACh concentration capable of generating a measurable IACh was 10 μM, and the maximum peak current (Imax) was reached at 1 mM. The blockade exerted by 0.3 μM KB-R7943 was unsurmountable, even by the highest concentrations of ACh used. Furthermore, the relative blockade exerted by KB-R7943 was larger at the highest concentrations of ACh used (see the inset of Figure 4a). Thus, at 30 μM and 1 mM of ACh, the compound reduced IACh by 34.6±5.4% and 66.5±2.5%, respectively; differences were statistically significant (P<0.001). As positive control to reinforce the KB-R7943 data, similar experiments were performed with 10 μM dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE), a known competitive blocker at the nicotinic AChRs (Harvey & Luetje, 1996), which produced a parallel shift to the right of the concentration-response curve for ACh. Maximum peak current (Imax) induced by 1 mM ACh in the absence or in the presence of KB-R7943 was 2.3±0.3 and 0.7±0.2 μA, respectively; such values were 2.6±0.3 and 2.4±0.3 μA, in the absence or presence of dihydro-β-erythroidine; these values were obtained from the concentration-response curves for ACh represented in Figure 4a. Results show that whereas the dihydro-β-erythroidine did not modify the Imax, KB-R7943 significantly reduced it (P⩽0.05). The calculated EC50 values for ACh in the absence, or in the presence of KB-R7943 or dihydro-β-erythroidine, were 91±11, 50±7 and 290±16 μM, respectively. Thus, in contrast to what is observed for the competitive antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine, the EC50 value to ACh became smaller, rather than larger, in the presence of KB-R7943 (P<0.01).

Figure 4.

Blockade by KB-R7943 of IACh through α3β4 nAChRs is non-competitive in nature. (a) Each oocyte was stimulated with pulses of increasing concentrations of ACh (abscissa) of 1 s duration, given at 1 min intervals, both in the absence (control) and in the presence of KB-R7943 (0.3 μM) dihidro-β-erythroidine (DHβE, 10 μM). The effects of the blockers on IACh were normalized in terms of percentage of control current measured during the peak (100% current). Data are means±s.e.mean of the number of oocytes shown in parentheses. Inset shows the relative percentage of blockade on control IACh, exerted by the two blockers, at each ACh concentration assayed. Blockade of IACh by KB-R7943 was significant at all concentrations of ACh tested (***P<0.001, *P<0.05), although it was significantly larger at the highest concentrations of ACh used. (b) Original traces of α3β4 currents elicited by two different concentrations of ACh assayed in the same oocyte, revealing the higher blockade by KB-R7943 of IACh evoked by 1 mM ACh; currents were normalized to the same size.

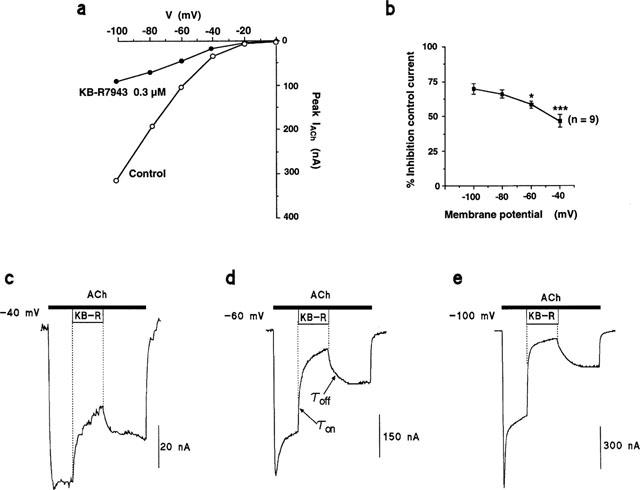

Blockade of α3β4 current by KB-R7943 is voltage-dependent

The IACh elicited by 100 μM ACh (1 s) was tested at various holding potentials (from −100 to 0 mV), both in the absence and in the presence of 0.3 μM KB-R7943. Figure 5a shows a prototype experiment performed in one oocyte expressing α3β4 currents. At −100 mV, the amplitude during the peak of IACh was 317 nA (control), and 94 nA (in the presence of KB-R7943); whereas at −40 mV, value was 35 nA in control, and 18 nA in the presence of KB-R7943. Figure 5b represents the blockade of IACh as a function of the holding membrane potential; values are expressed as percentage of control IACh and were obtained from different oocytes tested, as in Figure 5a. Results show that whereas the blocking effect of KB-R7943 on IACh was 69±3% at −100 mV, this effect was significantly smaller at −60 mV (58±2% inhibition; P<0.05), and even smaller at −40 mV (46±4% inhibition; P<0.001).

Figure 5.

KB-R7943 inhibits, in a voltage-dependent manner, IACh through α3β4 receptors. (a) Shows a typical experiment performed in one oocyte expressing α3β4 receptors that was voltage-clamped at various membrane potentials, from −100 to 0 mV, in 20 mV steps (abscissa). Two ACh pulses (100 μM, 1 s), 1 min apart, were applied at each holding potential; the value of the IACh peaks obtained in each pair of pulses at the same holding potential, were averaged and plotted as control (ordinate). This protocol was repeated in the same oocyte, but in the presence of 0.3 μM KB-R7943 added throughout the experiment. (b) Averaged values for the inhibition by KB-R7943 of IACh at the various potentials tested (abscissa) using the same protocol. Inhibition of the control current at each potential (ordinate) is normalized in terms of percentage of IACh obtained in the presence of the blocker; the 100% current was considered to be the amplitude of peak IACh preceding the addition of the compound. Values are means±s.e.mean of the number of oocytes shown in parentheses. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, compared with the blockade of IACh exerted by the compound at −100 mV. (c) Shows the original IACh traces elicited by 160 s application of 10 μM ACh (top horizontal black bar) in an α3β4 oocyte (out of five) voltage-clamped at −40 mV; KB-R7943 (0.3 μM) was given within the ACh pulse during the time period shown by ‘KB-R'. (d,e) Show the IACh traces, obtained in the same oocyte under similar experimental conditions, but voltage-clamped at −60 or −100 mV. The arrows in (d) indicate where the curves were fitted to single exponentials to calculate the time constant for blockade (τon) or recovery (τoff) of the current.

Although the experiments described above, using brief ACh pulses, reveal a clear voltage-dependence of the KB-R7943 effect on IACh, we attempted to disclose this property more sharply with still another protocol, which also will provide additional information concerning the rate of KB-R7943 blockade and washout. Figure 5c shows the IACh trace obtained in one oocyte expressing α3β4 receptors, voltage-clamped at −40 mV, and stimulated during 160 s with ACh; to reduce current desensitization upon this prolonged stimulation period, a moderate concentration of ACh (10 μM) was used. Then, when current stabilized (approximately 40 s after starting the ACh stimulation), the perfusion of KB-R7943 (0.3 μM) was initiated for a period of 50 s; the compound caused a relaxation of the current to a plateau which represented about 45% of initial current; washout of KB-R7943 restored the current amplitude to near its pre-KB-R7943 value. In Figure 5d,e, similar experiments are shown, but the same oocyte was this time voltage-clamped at −60 or −100 mV, respectively. Note that now KB-R7943 produced a faster and higher blockade of the current at more hyperpolarized membrane potential. Averaged pooled results from five oocytes showed 33.4±5.5% current blockade at −40 mV, 64.8±2.9% at −60 mV and 80.4±4.3% at −100 mV. The blockade of IACh by KB-R7943 fitted to a single exponential at each membrane potential; values of τon obtained were 7.6±1.2 s at −40 mV, 2.0±0.4 s at −60 mV and 1.9±0.2 s at −100 mV; values at −40 mV were significantly different (P⩽0.01) from those obtained at −60 and −100 mV. Differences in the time required to remove the blockade were also found among different membrane potentials; after removing KB-R7943, IACh blockade recovered faster at −40 mV (τoff=3.2±0.5 s; P<0.001) than at −60 or −100 mV (τoff=10.8±2.3 s and 13.7±2.6 s), respectively.

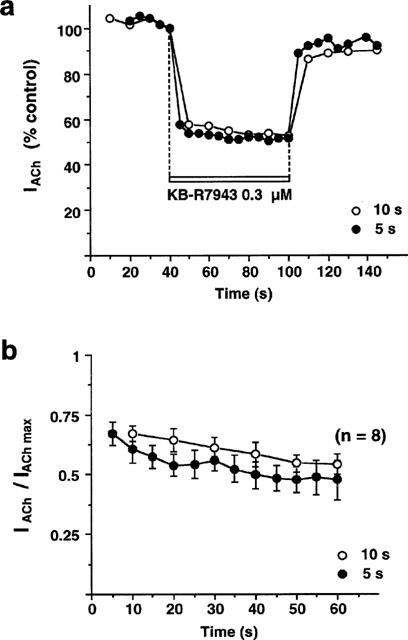

Blockade of α3β4 currents by KB-R7943 was similar at two frequencies of ACh stimulation tested

The main limitation to the study of the rate of development of IACh blockade by KB-R7943 lies in the desensitization of receptors upon repeated stimulation with ACh, applied at regular intervals, briefer than those used up to now. Thus, in order to get reproducible, non-desensitizing IACh, we had to recourse to brief pulses of ACh (100 μM, 0.5 s), applied every 5 or 10 s, to oocytes expressing α3β4 nAChRs. Figure 6a shows the results obtained in a typical oocyte in which ACh pulses were applied at the two frequencies; in this oocyte, KB-R7943 (0.3 μM), added continuously from the moment that current was reproducible, produced a fast blockade of IACh through α3β4 receptors, which was maximum during the first ACh pulse applied in the presence of the blocker; such an effect was promptly reversed upon washout of the compound. Figure 6b shows the results obtained in different oocytes assayed as above. No differences were found in the rate or extent of IACh blockade by KB-R7943 at the two frequencies of ACh stimulation tested.

Figure 6.

KB-R7943 blocks, in a stepwise, reversible and use-independent manner, α3β4 currents. (a) Represents the time-course of blocking effects of KB-R7943 (0.3 μM) on α3β4 current obtained in a typical oocyte; the oocyte was stimulated with ACh pulses (100 μM, 0.5 s) applied at two different intervals (10 or 5 s). After a few initial pulses, when the current stabilized (IACh max), KB-R7943 was added before and during the successive ACh pulses and the current obtained in the presence of the blocker, at each frequency, measured (IACh). After 60 s of perfusion, KB-R7943 was washed out. (b) Shows means±s.e.mean blocking values of KB-R7943 assayed, as above, in the number of oocytes shown in parentheses; values obtained at each frequency were expressed as ratio of IACh versus IACh max.

Discussion

The present study shows, for the first time, that KB-R7943 potently inhibits either native neuronal nicotinic AChRs present in bovine chromaffin cells, or rat brain α3β4 and α7 nicotinic AChRs expressed in oocytes. In addition, our results also confirm, in another system as the adrenal medullary chromaffin cells, the ability of KB-R7943 to block its native Na+/Ca2+ exchanger identified as an isoform of the NCX1 gene (Pan et al., 1998). The blockade of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger by the drug was exerted at concentrations in the low micromolar range (Figure 1b), similar to those concentrations required to inhibit this exchanger in fibroblasts transfected with the cardiac NCX1 clone (Iwamoto & Shigekawa, 1998). Thus, our results support the general view that KB-R7943 considerably improves the potency of organic (amiloride, bepridil and analogues) and inorganic blockers (Ni2+, La3+ and Cd2+), that required several tens to hundreds of micromolar to inhibit the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger to a significant extent (Garcia et al., 1988; Slaughter et al., 1988; Kaczorowski et al., 1989; Kleyman & Cragoe, 1988; Murphy et al., 1991; Iwamoto & Shigekawa, 1998).

However, our results reveal that the supposed selectivity of KB-R7943 to block the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is limited. Thus, although the compound exhibits a low potency to target various voltage-dependent channels and other ion transport systems so far studied (i.e. the neuronal Ca2+ channels present in chromaffin cells (Figure 2a), the inward rectifier K+ channel or the Na+/H+ exchanger (Iwamoto et al., 1996; Watano et al., 1996), it seems to recognize some ligand-gated ion channels such as the N-methyl-D-aspartate ion channels of hippocampal neurons (Sobolevsky et al., 1999) and the native neuronal nicotinic AChRs expressed in bovine chromaffin cells (present study), which most likely belong to the α3β4 and α7 subtypes (Criado et al., 1992; 1997; García-Guzmán et al., 1995; Campos-Caro et al., 1997). This last finding is corroborated in the present study using a more direct approach, the blockade of the rat brain nicotinic α3β4 or α7 currents expressed in oocytes; formed by nicotinic subunits highly homologous to their counterparts in chromaffin cells (Campos-Caro et al., 1997).

Thus, the results obtained in oocytes assaying the effects of KB-R7943 on the IACh reveal the following aspects concerning the selectivity and the mechanism of receptor blockade: (1) KB-R7943 appears to block the current by a direct interaction with the nicotinic AChR itself, and not through an indirect effect on the native ICl(Ca) of the oocyte (see Figure 3d); (2) the blockade produced was potent, fast and reversible, and the compound does not distinguish between α3β4 or α7 nAChR subtypes, at least as far as its potency is concerned and (3) the compound blocks the neuronal α3β4 AChR currents in a noncompetitive and voltage-dependent manner.

In relation to the efficacy and selectivity to target α3β4 or α7 AChRs expressed in oocytes, we find that KB-R7943 inhibits with similar potency the IACh through both receptor subtypes (IC50 of 0.4 μM); this low IC50 value indicates that the compound was very active acting on more than one type of nicotinic AChR; the low Hill coefficient obtained for both subtypes of receptors suggests the absence of cooperativity in the blockade elicited by the drug. Differences among IC50 values obtained in oocytes and chromaffin cells concerning the receptor blockade by KB-R7943 could be explained by the different techniques used (45Ca2+ uptake or [Ca2+]c signal in chromaffin cells versus IACh in oocytes), rather than to a different sensitivity of native and expressed receptors. This hypothesis is reinforced by the fact that native nicotinic receptors in chromaffin cells are more sensitive to the blocking effect of KB-R7943 when the parameter measured was the ACh-elicited [Ca2+]c signal (IC50=1.7 μM) instead of the 45Ca2+ uptake (IC50=6.5 μM).

When the mechanism of α3β4 currents blockade was analysed, the first finding was that KB-R7943 interacts with the receptor in a noncompetitive fashion. Thus, the blockade of IACh was unsurmountable by increasing concentrations of ACh; furthermore, the compound significantly reduced the Imax, in contrast to dihydro-β-erythroidine, a well known competitive blocker at the nicotinic AChR (Harvey & Luetje, 1996). Moreover, our results also reveal that the EC50 value for ACh became smaller in the presence of KB-R7943, as would be expected for a noncompetitive antagonist which blocks those channels that are open, by entering and occluding the channel itself. In this sense, when the concentration of ACh was increased, maintaining the same concentration of KB-R7943, the fraction of IACh blocked was significantly larger (see inset of Figure 4a,b). This behaviour has been reported for noncompetitive agents considered as open channel blockers of the nicotinic AChRs, i.e. hexamethonium; such effect is opposite to what would be expected for a competitive antagonist drug, i.e. dihydro-β-erythroidine (inset Figure 4a).

The above result suggests that the site of action of KB-R7943 seems to be located within the ion channel pore of the nicotinic AChR. This view was reinforced by the clear voltage-dependence of the IACh blockade exhibited by the compound; the fraction of the inhibited current increased with more negative holding potential values (Figure 5). In addition, the blockade of IACh was faster at −60 or −100 mV than at −40 mV; the opposite occurs with the recovery after washout of the drug (compare Figure 5c,d,e). These results suggest that KB-R7943 has to enter inside the ion pore of the receptor, so that the compound can feel the changes in the potential field of the membrane.

In conclusion, the novel isothiourea derivative KB-R7943, behaves as a potent blocker of neuronal nicotinic AChRs. Its features of noncompetitive blockade and voltage-dependent effect on the receptor, can be interpreted in the frame of an open-channel blocking mechanism, as proposed by Buisson & Bertrand (1998) for the blockade of α4β2 currents by hexamethonium, amantadine, memantadine and TMB-8. The lack of use-dependence of the KB-R7943 effect on IACh at the two frequencies of ACh assayed, is not compatible with this mechanism; however, the slow superfusion system in the oocytes experiments, as well as the desensitization of the nicotinic nAChR, limited a study using a wider range of stimulation frequencies with ACh, that could provide a better resolution of this issue. The effectiveness and potency of KB-R7943 to block different subtypes of neuronal nicotinic AChRs reported in the present study should be taken into account if the compound is used as a pharmacological tool to explore the role of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in the control of Ca2+ homeostasis, in those cells where this electrogenic transport and nicotinic AChRs coexist. Such is the case of chromaffin cells, the sympathetic and parasympathetic ganglia, or the central nAChR synapses.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Hiroshi Nakagawa from Pharmaceutical Research Laboratories, Kanebo Ltd. (Osaka, Japan) for kindly providing us with KB-R7943. Also, we thank Prof Heinemann (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.) for providing the plasmid pPCA48E, pZPC13 and pHIP306 containing the coding regions for the rat brain nicotinic α3, β4 and α7 subunits. This work was supported by grants from DGES No PB 97-0047 and PB98-0090 to C. Montiel; and Plan Nacional de Investigación I+D No 2FD97-0388-C02-01 and Fundación Teófilo Hernando to A.G. García. A.J. Pintado is a fellow of Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain. C.J. Herrero is a fellow of Fundación Teófilo Hernando, Madrid, Spain.

Abbreviations

- AChRs

acetylcholine receptors

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- HEPES

Krebs-N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulphonic acid

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

References

- BUISSON B., BERTRAND D. Open-channel blockers at the human α4β2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:555–563. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPOS-CARO A., SMILLIE F.I., DOMÍNGUEZ DEL TORO E., ROVIRA J.C., VICENTE-AGULLÓ F., CHAPULI J., JUÍZ J.M., SALA S., SALA F., BALLESTA J.J., CRIADO M. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor on bovine chromaffin cells: Cloning, expression and genomic organization of receptor subunits. J. Neurochem. 1997;68:488–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68020488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHERN Y.J., CHUEH S.H., LIN Y.J., HO C.M., KAO L.S. Presence of Na+/Ca2+ exchange activity and its role in regulation of intracellular calcium concentration in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Cell Calcium. 1992;13:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(92)90003-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRIADO M., ALAMO L., NAVARRO A. Primary structure of an agonist binding subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor from bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Neurochem. Res. 1992;17:281–287. doi: 10.1007/BF00966671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRIADO M., DOMÍNGUEZ DEL TORO E., CARRASCO-SERRANO C., SMILLIE F.I., JUÍZ J.M., VINIEGRA S., BALLESTA J.J. Differential expression of α-bungarotoxin-sensitive neuronal nicotinic receptors in adrenergic chromaffin cells: A role for transcription factor Egr-1. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:6554–6564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06554.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESQUERRO E., GARCIA A.G., HERNADEZ M., KIRPEKAR S.M., PRAT J.C. Catecholamine secretory response to calcium reintroduction in the perfused cat adrenal gland treated with ouabain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1980;29:2669–2673. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(80)90084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA A.G., GARCIA-LOPEZ E., HORGA J.F., KIRPEKAR S.M., MONTIEL C., SANCHEZ-GARCIA P. Potentiation of K+-evoked catecholamine release in the cat adrenal gland treated with ouabain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1981a;74:673–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb10478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA A.G., GARCIA-LOPEZ E., MONTIEL C., NICOLAS G.P., SANCHEZ-GARCIA P. Correlation between catecholamine release and sodium pump inhibition in the perfused adrenal gland of the cat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1981b;74:665–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb10477.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA M.L., SLAUGHTER R.S., KING V.F., KACZOROWSKI G.J. Inhibition of Sodium-Calcium exchange in cardiac sarcolemmal membrane vesicles. 2. Mechanism of inhibition of bepridil. Biochemistry. 1988;27:2410–2415. doi: 10.1021/bi00407a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCÍA-GUZMÁN B.M., SALA F., SALA S., CAMPOS-CARO A., STÜHMER W., GUTIÉRREZ L.M., CRIADO M. α-Bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic receptors on bovine chromaffin cells: Molecular cloning, functional expression and alternative splicing of the α7 subunit. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1995;7:647–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRYNKIEWICZ G., POENIE M., TSIEN R.Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARVEY S.C., LUETJE C.W. Determinants of competitive antagonist sensitivity on neuronal nicotinic receptor β subunits. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:3798–3806. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03798.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERRERO C.J., GARCÍA-PALOMERO E., PINTADO A.J., GARCÍA A.G., MONTIEL C. Differential blockade of rat α3β4 and α7 neuronal nicotinic receptors by ω-conotoxin MVIIC, ω-conotoxin GVIA and diltiazem. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:1375–1387. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IWAMOTO T., SHIGEKAWA M. Differential inhibition of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger isoforms by divalent cations and isothiourea derivative. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:423–430. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IWAMOTO T., WATANO T., SHIGEKAWA M. A novel isothiourea derivative selectively inhibits the reverse mode of Na+/Ca2+ exchange in cells expressing NCX1. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:22391–22397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KACZOROWSKI G.J., SLAUGHTER R.S., KING V.F., GARCIA M.L. Inhibitors of sodium-calcium exchange: identification and development of probes of transport activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1989;988:287–302. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(89)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEYMAN T.R., CRAGOE E.J. , JR Amiloride and its analogs as tools in the study of ion transport. J. Membr. Biol. 1988;105:1–21. doi: 10.1007/BF01871102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOMURO I., WENNINGER K.E., PHILIPSON K.D., IZUMO S. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human cardiac Na+/Ca+ exchanger cDNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:4769–4773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN L.F., KAO L.S., WESTHEAD E.W. Agents that promote protein phosphorylation inhibit the activity of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and prolong Ca2+ transients in bovine chromaffin cells. J. Neurochem. 1994;63:1941–1947. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63051941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU P.S., KAO L.S. Na+-dependent Ca2+ influx in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Cell Calcium. 1990;11:573–579. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90011-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIVETT B.G. Adrenal medullary chromaffin cells in vitro. Physiol. Rev. 1984;64:1103–1161. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1984.64.4.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LÓPEZ M.G., MONTIEL C., HERRERO C.J., GARCÍA-PALOMERO E., MAYORGAS I., HERNÁNDEZ-GUIJO J.M., VILLARROYA M., OLIVARES R., GANDÍA L., MCINTOSH J.M., OLIVERA B.M., GARCÍA A.G. Unmasking the functions of the chromaffin cell α7 nicotinic receptor by using short pulses of acetylcholine and novel selective blockers. Proc. Nalt. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:14184–14189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILEDI R., PARKER I. Chloride current induced by injection of calcium into Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1984;357:173–183. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILEDI R., PARKER I., SUMIKAWA K. Properties of acetylcholine receptors translated by cat muscle mRNA in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1989;1:1307–1312. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONTIEL C., HERRERO C.J., GARCÍA-PALOMERO E., RENART J., GARCÍA A.G., LOMAX R.B. Serotonergic effects of dotarizine in coronary artery and in oocytes expressing 5-HT2 receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;332:183–193. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORO M.A., LÓPEZ M.G., GANDÍA L., MICHELENA P., GARCÍA A.G. Separation of living adrenaline- or noradrenaline-containing cells from bovine adrenal medullae. Anal. Biochem. 1990;185:243–248. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90287-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURPHY E., PERLMAN M., LONDON R.E., STEENBERGEN C. Amiloride delays the ischemia-induced rise in cytosolic free calcium. Circ. Res. 1991;68:1250–1258. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.5.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEHER E. The use of fura-2 for estimating Ca buffers and Ca fluxes. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1423–1442. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00144-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAN C.Y., CHU Y.S., KAO L.S. Molecular study of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Biochem. J. 1998;336:305–310. doi: 10.1042/bj3360305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAN C.Y., KAO L.S. Catecholamine secretion from bovine adrenal chromaffin cells: the role of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and the intracellular Ca2+ pool. J. Neurochem. 1997;69:1085–1092. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69031085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAPKE R.L., HEINEMANN S.F. The role of the beta 4-subunit in determining the kinetic properties of rat neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine alpha 3-receptors. J. Physiol. (Lond) 1991;440:95–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEGUELA P., WADICHE J., DINELEY-MILLER K., DANI J.A., PATRICK J.W. Molecular cloning, functional expression and distribution of rat brain α7. A nicotinic cation channel highly permeable to calcium. J. Neurochem. 1993;13:596–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00596.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SLAUGHTER R.S., GARCIA M.L., CRAGOE E.J., JR, REEVES J.P., KACZOROWSKI G.J. Inhibition of sodium-calcium exchange in cardiac sarcolemmal membrane vesicle. 1. Mechanism of inhibition by amiloride analogues. Biochemistry. 1988;27:2403–2409. doi: 10.1021/bi00407a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOBOLEVSKY A.I., KHODOROV B.I. Blockade of NMDA channels in acutely isolated rat hippocampal neurons by the Na+/Ca2+ exchange inhibitor KB-R7943. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1235–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VILLARROYA M., DE LA FUENTE M.T., LOPEZ M.G., GANDÍA L., GARCÍA A.G. Distinct effects of ω-conotoxins and various groups of Ca2+-entry inhibitors on nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and Ca2+ channels of chromaffin cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;320:249–257. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VILLARROYA M., LOPEZ M.G., CANO-ABAD M.F., GARCÍA A.G. Measurement of Ca2+ entry using 45Ca2+ Methods Mol. Biol. 1999;114:137–147. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-250-3:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WADA A., TAKARA H., YANAGIHARA N., KOBAYASHI H., IZUMI F. Inhibition of Na+-pump enhances carbachol-induced influx of 45Ca2+ and secretion of catecholamines by elevation of cellular accumulation of 22Na+ in cultured bovine adrenal medullary cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1986;332:351–356. doi: 10.1007/BF00500086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATANO T., KIMURA J., MORITA T., NAKANISHI H. A novel antagonist, No. 7943, of the Na+/Ca2+ exchange current in guinea-pig cardiac ventricular cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:555–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]