Abstract

The contractile profile of human urotensin-II (hU-II) was examined in primate airway and pulmonary vascular tissues. hU-II contracted tissues from different airway regions with similar potencies (pD2s from 8.6 to 9.2). However, there were regional differences in the efficacy of hU-II, with a progressive increase in the maximum contraction from trachea to smaller airway regions (from 9 to 41% of the contraction to 10 μM carbachol). hU-II potently contracted pulmonary artery tissues from different regions with similar potencies and efficacies: pD2s=8.7 to 9.3 and maximal contractions=79 to 86% of 60 mM KCl. hU-II potently contracted pulmonary vein preparations taken proximal to the atria, but had no effect in tissues from distal to the atria. This is the first report describing the contractile activity of hU-II in airways and suggests that the potential pathophysiological role of this peptide in lung diseases warrants investigation.

Keywords: Human urotensin-II, primate lung, contractile activity, primate trachea, primate bronchus, primate pulmonary artery, primate pulmonary vein

Introduction

Urotensin-II (U-II) is an 11-amino acid cyclic peptide found in diverse species, including humans (Coulouarn et al., 1998; Ames et al., 1999). In humans preproU-II is expressed within both the CNS and the periphery, notably in the vasculature (Ames et al., 1999). Recently, Ames et al. (1999) identified human (h)U-II as a selective ligand for a novel G-protein-coupled receptor homologous to a rat ‘orphan' receptor originally designated SENR or GPR14 (see Davenport & Maguire, 2000).

U-II is most widely known for its ability to regulate smooth muscle tone in fish, amphibian and mammalian isolated vascular tissues (Muramatsu et al., 1979; Gibson, 1987; Conlon et al., 1996; Ames et al., 1999; Douglas et al., 2000). In addition, non-vascular preparations, including gastrointestinal (ileum, rectum) and genitourinary (bladder, oviduct, sperm duct) smooth muscle tissues, are contracted by U-II (Bern et al., 1985; Yano et al., 1994; Conlon et al., 1996). However, there is no information on the contractile activity of U-II in the airways. The present study characterized the effect of hU-II in tracheal and bronchial smooth muscle preparations from the primate respiratory tract. A comparison was made with the profile of hU-II in the pulmonary vasculature.

Methods

Seven male cynomolgus monkeys (4–15 years; 3.4–9.2 kg) were euthanized with pentobarbital sodium (at least 100 mg kg−1, i.v.) and the lungs removed. Pulmonary artery (secondary, tertiary and quaternary generation), primary pulmonary vein, trachea and bronchus (primary, secondary and tertiary generation) were removed and cleaned of adherent tissue. Strips (approximately two cartilage rings width; 5–7 mm length) were cut from the trachea and primary bronchus, and rings (approximately 2–5 mm diameter, 3–4 mm length) were cut from the secondary and tertiary bronchi. Rings (approximately 2–5 mm diameter, 3–5 mm length) were cut from pulmonary artery and vein. The endothelium of the pulmonary artery and vein was removed by gently rotating tissue segments several times around the end of suturing forceps (Hay et al., 1993). Individual tissues were suspended via stainless steel hooks and/or silk suture in 10-ml water-jacketed organ baths containing Krebs–Henseleit solution, which was gassed with 95% O2: 5% CO2 and maintained at 37°C, and connected to Grass FTO3C force-displacement transducers; the composition of the modified Krebs–Henseleit solution was (mM): NaCl 113.0, KCl 4.8, CaCl2 2.5, KH2PO4 1.2, MgSO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25.0 and dextrose 11.0. Mechanical responses were recorded isometrically by MP100WS/Acknowledge data acquisition system (Biopac Systems; Santa Barbara, CA, U.S.A.) run on Macintosh computers. Experiments were run in the presence of 10 μM indomethacin. The tissues were equilibrated under a resting tension of 0.5 g for small tissues to 1.5 g for larger tissues, and washed with Krebs–Henseleit solution every 15 min for 1 h. After the equilibration period airways were contracted with 10 μM carbachol and pulmonary vascular tissues with 60 mM KCl until the response reached a plateau. Tissues were then rinsed every 15 min over 1 h until reaching baseline tone, and the preparations were then left for at least 30 min before the start of the experiment.

hU-II concentration-response curves were obtained by cumulative addition of the agonist in half-log increments. At the end of the experiment, tissues were exposed again to 10 μM carbachol (airways) or 60 mM KCl (blood vessels) which served as a reference contraction for data analysis. The results were calculated as pD2 and maximum contractile response (percentage of contraction to reference agonist added at the end of the experiment; ‘post-KCl' or ‘post-carbachol'). All data are given as mean±standard error of the mean (s.e.mean) with n being the number of different animals. Statistical analysis was done using Student's t-test, with a probability, P,<0.05 regarded as significant.

Results

Airways

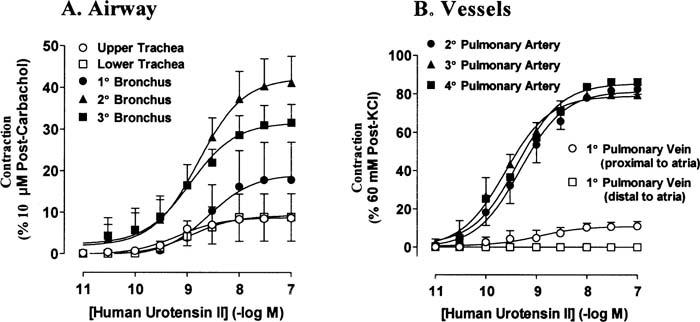

hU-II potently contracted tissues from different airway regions – upper and lower trachea, primary, secondary and tertiary bronchus – with similar potencies, yielding pD2s from 8.6 to 9.2 (n=3–4; Table 1; Figure 1). In contrast, there were marked regional differences in the efficacy elicited by hU-II. Thus, in upper and lower tracheal tissues the maximum responses to hU-II (100 nM) represented only about 9% of the reference contraction (10 μM post-carbachol response; n=4); upper tracheal preparations from two of these animals, and lower tracheal tissues from one animal, did not respond to hU-II. In the bronchial tissues hU-II was a much more effective contractile agonist than in the trachea; maximum contractions to 100 nM hU-II (10 μM post-carbachol): primary bronchus=17.8±9.1; secondary bronchus=41.2±6.4; tertiary bronchus=34.4±4.8 (n=3–4) (Table 1; Figure 1).

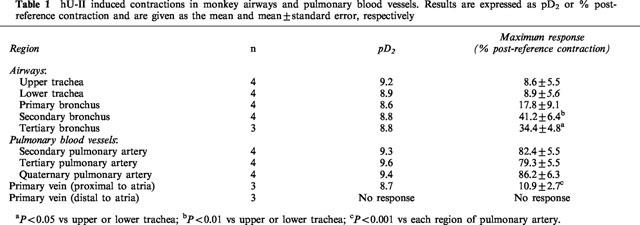

Table 1.

hU-II induced contractions in monkey airways and pulmonary blood vessels. Results are expressed as pD2 or % post-reference contraction and are given as the mean and mean±standard error, respectively

Figure 1.

Concentration-response curves to hU-II in primate airways (A) and pulmonary blood vessels (B). Results are expressed as a percentage of the reference contraction obtained at the end of the experiment and are given as the mean±standard error; n=3–4.

Pulmonary blood vessels

hU-II potently contracted pulmonary arterial preparations from different regions with similar potencies and efficacies: pD2s were 8.7 to 9.3, and maximal contractions ranged from 79 to 86% of post-60 mM KCl (n=3–4; Table 1; Figure 1).

hU-II contracted pulmonary vein in preparations taken proximal to the atria with a pD2 of 8.9. The maximal contraction (10.9±2.7% of post-60 mM KCl; n=3) was significantly less than that obtained in pulmonary arterial preparations. Primary pulmonary vein from a region distal to the atria did not contract to hU-II (in concentrations up to 100 nM; n=3).

It is noteworthy that there was marked inter-animal variation in the responsiveness of monkey airways, to hU-II. Thus airway preparations from four of the seven animals explored contracted to hU-II, whereas there were little or no contractile responses in any tissues from the other animals; in these three sets of preparations there was the characteristic response to the contractile agonist, carbachol and endothelin-1.

Responses to hU-II in all airway and vascular preparations were slow to develop (peak response to each concentration of hU-II was obtained after approximately 30–60 min).

Discussion

This report describes for the first time potent contractile activity of hU-II in airways. hU-II is an 11-amino acid cyclic peptide which was recently identified as the cognate ligand for GPR14, a member of the superfamily of G-protein coupled, seven transmembrane-spanning receptors (Ames et al., 1999; Davenport & Maguire, 2000). Although U-II has been demonstrated to contract mammalian isolated vascular tissue (Muramatsu et al., 1979; Gibson, 1987; Conlon et al., 1996; Ames et al., 1999; Douglas et al., 2000) and also non-vascular preparations, including gastrointestinal and genitourinary smooth muscle tissues (Bern et al., 1985; Yano et al., 1994; Conlon et al., 1996), its influence on isolated respiratory tissues is not known.

In the current study hU-II potently contracted tracheal and bronchial smooth muscle preparations from the primate respiratory tract. Although the potencies of hU-II were similar in the different preparations there were marked regional differences in the maximum contractile responses to hU-II, with the efficacies progressively increasing with decreasing airway diameter from upper trachea to tertiary bronchus. A similar gradation in the maximum response to the endothelin receptor ligand, sarafotoxin S6c, was noted from upper tracheal to bronchial tissue of the guinea-pig (Hay et al., 1993). No regional differences in the maximum responses to hU-II were noted when comparing secondary, tertiary and quaternary pulmonary artery. However, unlike the arterial tissues, hU-II produced little or no effect in pulmonary vein (primary); there was evidence of a small contraction in tissues obtained proximal but not distal to the atria.

It was observed that there was some inter-animal variation in the sensitivity of monkey airways and pulmonary vascular tissues to hU-II, with preparations from some animals much less responsive. The reason(s) for this observation is unknown, but it is a phenomenon that has been demonstrated previously with hU-II in human pulmonary artery (MacLean et al., 2000).

The potent contractile effects of hU-II in primate lung suggests that exploration of its effect in human pulmonary tissues will be worthy of investigation. In addition, it will be important to elucidate the non-contractile influences of hU-II, and, thus, its overall profile in the lung to determine if it may be a pathophysiologically relevant mediator in pulmonary disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Charles Sauermelch, Bob Willette and Bob Coatney for providing the tissues.

Abbreviations

- hU-II

human urotensin-II

References

- AMES R.S., SARAU H.M., CHAMBERS J.K., WILLETTE R.N., AIYAR N.V., ROMANIC A.M., LOUDEN C.S., FOLEY J.J., SAUERMELCH C.F., COATNEY R.W., AO Z., DISA J., HOLMES S.D., STADEL J.M., MARTIN J.D., LIU W.-S., GLOVER G.I., WILSON S., MCNULTY D.E., ELLIS C.E., ELSHOURBAGY N.A., SHABON U., TRILL J.J., HAY D.W.P., OHLSTEIN E.H., BERGSMA D.J., DOUGLAS S.A. Human urotensin-II is a potent vasoconstrictor and agonist for the orphan receptor GPR14. Nature. 1999;401:282–286. doi: 10.1038/45809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERN H.A., PEARSON D., LARSON B.A., NISHIOKA R.S. Neurohormones from fish tails: the caudal neurosecretory system. I. ‘Urophysiology' and the caudal neurosecretory system of fishes. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 1985;41:533–552. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571141-8.50016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONLON J.M., YANO K., WAUGH D., HAZON N. Distribution and molecular forms of urotensin II and its role in cardiovascular regulation in vertebrates. J. Exp. Zool. 1996;275:226–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COULOUARN Y., LIHRMANN I., JEGOU S., ANOUAR Y., TOSTIVINT H., BEAUVILLAIN J.C., CONLON J.M., BERN H.A., VAUDRY H. Cloning of the cDNA encoding the urotensin II precursor in frog and human reveals intense expression of the urotensin II gene in motoneurons of the spinal cord. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:15803–15808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVENPORT A.P., MAGUIRE J.J. Urotensin II: fish neuropeptide catches orphan receptor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2000;21:80–82. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS S.A., ASHTON D.J., SAUERMELCH C.F., COATNEY R.W., OHLSTEIN D.H., RUFFOLO M.R., OHLSTEIN E.H., AIYAR N.V., WILLETTE R.N.Human urotensin-II is a potent vasoactive peptide: pharmacological characterisation in the rat, mouse, dog and primate J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2000(in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- GIBSON A. Complex effects of Gillichthys urotensin II on rat aortic strips. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987;91:205–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb09000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAY D.W.P., LUTTMANN M.A., HUBBARD W.C., UNDEM B.J. Endothelin receptor subtypes in human and guinea-pig pulmonary tissues. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:1175–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACLEAN M.R., ALEXANDER D., STIRRAT A., GALLAGHER M., DOUGLAS S.A., OHLSTEIN E.H., MORECROFT I., POLLAND K. Contractile responses to human urotensin-II in rat and human pulmonary arteries: effect of endothelial factors and chronic hypoxia in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:201–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURAMATSU I., FUJIWARA M., HIDAKA H., AKUTAGAWA H. Pharmacological analysis of urotensin-II-induced contraction and relaxation in isolated rabbit aortas. Gunma Symp. Endocrinol. 1979;16:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- YANO K., VAUDRY H., CONLON J.M. Spasmogenic actions of frog urotensin II on the bladder and ileum of the frog. Rana catesbeiana. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1994;96:412–419. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1994.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]