Abstract

Evidence has previously been presented that P1 receptors for adenosine, and P2 receptors for nucleotides such as ATP, regulate stimulus-evoked release of biogenic amines from nerve terminals in the brain. Here we investigated whether adenosine and nucleotides exert presynaptic control over depolarisation-elicited glutamate release.

Slices of rat brain cortex were perfused and stimulated with pulses of 46 mM K+ in the presence of the glutamate uptake inhibitor L-trans-pyrrolidine-2,4-dicarboxylic acid (0.2 mM). High K+ substantially increased efflux of glutamate from the slices.

Basal glutamate release was unchanged by the presence of nucleotides or adenosine at concentrations of 300 μM.

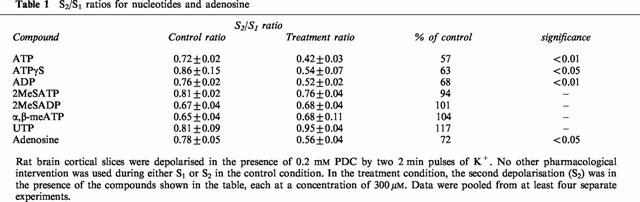

Adenosine, ATP, ADP and adenosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphoshate) at 300 μM attenuated depolarisation-evoked release of glutamate. However UTP, 2-methylthio ATP, 2-methylthio ADP, and α,β-methylene ATP at 300 μM had no effect on stimulated glutamate efflux.

Adenosine deaminase blocked the effect of adenosine, but left the response to ATP unchanged.

The A1 antagonist 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine antagonised the inhibitory effect of both adenosine and ATP.

Cibacron blue 3GA inhibited stimulus-evoked glutamate release when applied alone. When cibacron blue 3GA was present with ATP, stimulus-evoked glutamate release was almost eliminated. However, this P2 antagonist had no effect on the inhibition by adenosine.

These results show that the release of glutamate from depolarised nerve terminals of the rat cerebral cortex is inhibited by adenosine and ATP. ATP appears to act directly and not through conversion to adenosine.

Keywords: P2 receptors, P2Y receptors, adenosine receptors, glutamate release, ATP, presynaptic inhibition

Introduction

It has been accepted for many years that ATP acts as a neurotransmitter (Burnstock, 1972; 1976). This is largely a result of studies on the autonomic neuroeffector junction, where ATP is a co-transmitter, and may in some cases act as the primary transmitter (Burnstock et al., 1972; Meldrum & Burnstock, 1983; von Kugelgen et al., 1994a). Our understanding of the neurotransmitter role for ATP developed further with evidence for prejunctional modulation of neurotransmitter release from autonomic terminals by adenine nucleotides and adenosine acting on presynaptic receptors (Paton, 1981; Wicklund et al., 1985). UTP has also been shown to directly regulate noradrenaline release from sympathetic neurons (Boehm, 1998; Norenberg et al., 2000).

On release into the synaptic cleft ATP is rapidly broken down to adenosine. A major issue in these studies is whether ATP acts directly at presynaptic P2 receptors, or is converted to adenosine, which then acts on presynaptic P1 receptors. While inhibitory P1 receptors are well known (Fredholm & Dunwiddie, 1988), there is evidence that ATP acts directly at presynaptic P2 receptors in the autonomic nervous system (e.g. Shinozuka et al., 1988; Kurz et al., 1993; Allgaier et al., 1994; von Kugelgen et al., 1995).

P2 receptors for nucleotides are divided into two families: ionotropic P2X receptors, and G protein-coupled P2Y receptors (Fredholm et al., 1997; Boarder & Hourani, 1998). P2X receptors are essentially receptors for ATP, whereas the P2Y family includes receptors for both purine and pyrimidine nucleotides (ATP, ADP, UTP and UDP). In the brain ATP is known to be a fast excitatory neurotransmitter, acting directly at postsynaptic P2X receptors (e.g. Edwards et al., 1992). P2Y receptors are believed to be widespread in the brain (Webb et al., 1994), where they may have an excitatory role, acting by reducing K+ channel opening (Shen & North, 1993; Nieber et al., 1997). Additionally, in rat brain preparations P2Y receptors have been shown to play a role in presynaptic inhibition of release of noradrenaline, 5-hydroxytryptamine and dopamine (von Kugelgen et al., 1994b; Koch et al., 1995; 1997a,1997b). There is also a report of enhanced dopamine release on activation of P2Y1 receptors in the rat brain striatum (Zhang et al., 1995).

Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, and there is emerging evidence that its release is subject to presynaptic regulation by P2 receptors. Activation of P2X receptors has been shown to elicit glutamate release from terminals of dorsal root ganglia in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Gu & MacDermott, 1997). An electrophysiological study on hippocampal neurons (Koizumi & Inoue, 1997) provided evidence suggesting an inhibitory influence of presynaptic P2 receptors on glutamate release. These findings follow previous electrophysiological studies showing attenuation of central excitatory neurotransmission by adenosine acting at presynaptic P1 receptors (e.g. Silinsky & Ginsborg, 1983; Manzoni et al., 1994). Therefore it is possible that ATP acting at the presynaptic site may modulate brain glutamate release by direct action, and also by conversion to adenosine. In the present study we set out to directly investigate whether glutamate release from rat brain cortical slices is subject to regulation by adenosine and by nucleotides such as ATP.

Methods

Preparation and perfusion of brain slices

Adult Wistar rats were killed, the cortices dissected on ice and cross-chopped into 350×350 μm prisms which were washed three times in 20 ml Krebs gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2. Slices were preincubated with gentle shaking at 37°C for 80 min with four changes of gassed medium. One ml of gravity packed slices was then placed in each superfusion chamber and perfused with pre-gassed Krebs (37°C) at 0.7 ml min−1 for 45 min before beginning drug treatments. Two-minute fractions of the perfusate were then collected.

Stimulation of perfused slices

A double stimulation protocol (S1/S2) was adopted. In a typical experiment 0.2 mM of the glutamate uptake inhibitor, L-trans-pyrrolidine-2,4-dicarboxylic acid (PDC) was present throughout. Three 2 min samples were collected and their glutamate concentration averaged to give an estimation of basal efflux, followed by a 2 min pulse of 46 mM KCl (S1), a recovery period of 22 min, and a second KCl pulse (S2) of 2 min. Agonists (adenosine or nucleotides) were included for 2 min prior to and during S2; antagonists and adenosine deaminase were introduced, as indicated, 4 min prior to and during S2. Two-minute fractions were collected during and either side of both S1 and S2. Glutamate concentrations in the fractions were determined, and S2/S1 ratios calculated from the area under the S1 and S2 peaks after deduction of basal release. Conclusions were drawn by comparing S2/S1 ratios in the presence of test compounds during S2, with the ratios obtained in controls run in the same experiment in which no test compounds were introduced.

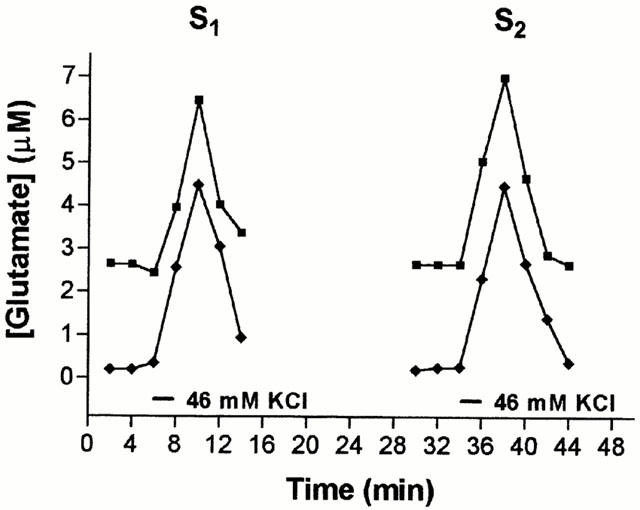

Measurement of glutamate

Two methods were used to measure glutamate. The first procedure measures the glutamate-dependent conversion of NADP to NADPH. A 475 μl aliquot of each fraction was incubated with 30 units of glutamate dehydrogenase (10 μl) and 15 μl NADP (1 mM final concentration) for 10 min at 37°C. Fluorescence was measured in a SPEX fluorimeter (λEx=366, λEm 432 nm). In the second method, glutamate concentration was determined by HPLC with pre column o-opthaldehyde (OPA) derivatisation. Fifty-μl aliquots of perfusate fractions were reacted with an equal volume of OPA (50 mg in 20 ml of 5% methanol, 0.5% β-mercaptoethanol in 1 M boric acid, pH 9.5) for 2 min before injection of the samples onto a reverse phase (C18) analytical column and elution with an acetonitrile/methanol gradient. Detection was with a CMA 280 fluorometric detector. The amino acid peaks were identified using standards. A standard curve was constructed using known concentrations of glutamate. A straight-line relationship between glutamate concentration and fluorometric signal was observed. The two methods gave essentially the same results as shown in Figure 1, in which S1 and S2 peaks of glutamate release were analysed by both methods. The apparent basal levels varied depending on the method used, but the area under each of the two peaks was the same for each method. Data analysis included deduction of basal release, so the outcome of the experiments was the same regardless of the method used.

Figure 1.

Stimulation of glutamate release by 2 consecutive pulses of 46 mM K+. Three basal samples were collected before slices were depolarised using a 2 min pulse of 46 mM K+ as indicated by the first bar. This depolarisation was repeated 30 min later. PDC (0.2 mM) was present throughout the experiment. The concentration of glutamate released from the slices upon depolarisation was calculated using the fluorometric and the HPLC methods for the same samples and plotted against time. These are typical examples of results from a single experiment.

Data analysis

Control and treatment pairs were drawn from the same experiment i.e. from the same group of slices. Areas under curves and determinations based on standard curves were calculated with Graphpad Prism. Each experiment was performed at least four times, and statistical analysis was by analysis of variance with Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons.

Results

Effect of inhibiting glutamate re-uptake with L-trans-pyrrolidine-2,4-dicarboxylic acid (PDC)

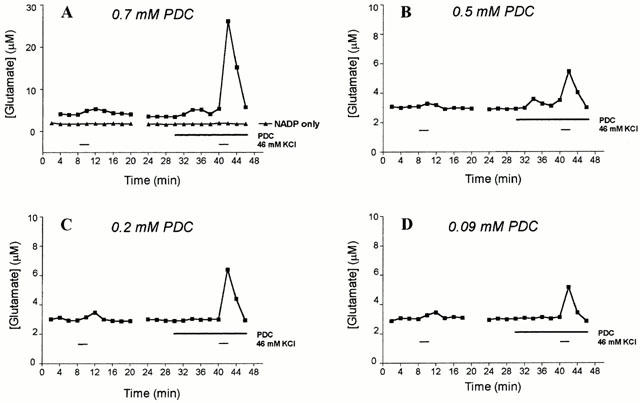

Various concentrations of PDC were tested in the superfusion system for an effect on basal levels of glutamate release, as well as glutamate efflux in response to 46 mM K+ (Figure 2). The left-hand traces in each panel of Figure 2 show a small depolarisation-elicited increase in glutamate efflux in the absence of PDC; depolarisation was then repeated for the same slice in the presence of PDC. At 0.7 or 0.5 mM, PDC caused an increase in basal glutamate efflux, whereas 0.2 or 0.09 mM PDC was without effect (consistent with Volterra et al., 1996). The slices were then exposed to a 2 min pulse of K+ in the presence of PDC to determine the effect of the uptake inhibitor on depolarisation-elicited glutamate efflux. At each concentration of PDC tested, the stimulus-evoked glutamate release was greatly enhanced. A concentration of 0.2 mM PDC was chosen for all subsequent experiments, since this enhanced stimulus-evoked glutamate release without affecting basal efflux (Figure 2C). Typical profiles of stimulus-evoked glutamate release with two sequential pulses of high K+ (S1 and S2), in the presence of 0.2 mM PDC are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Effect of PDC on stimulus-evoked release of glutamate. Slices were depolarised with two consecutive pulses of 46 mM KCl, with PDC present during the second pulse, as indicated by the bars. Different final concentrations of PDC were used in each of the four experiments shown: (A) 0.7 mM; (B) 0.5 mM; (C) 0.2 mM; (D) 0.09 mM. Glutamate was assayed by the glutamate dehydrogenase method in this study, and in (A) a single set of results are shown when glutamate dehydrogenase was omitted from the assay, and aliquots of fractions were incubated with 1 mM NADP alone. The results are from a single representative experiment.

To confirm that the detected increase in fluorescence was not due to release of fluorescent material or to cell disruption, caused by a combination of KCl and PDC, two sets of controls were carried out. In one series of experiments glutamate dehydrogenase was omitted from the assay system; as shown in Figure 2A this eliminated the stimulus-evoked increase in fluorescence. In another series, slices were stimulated with 46 mM KCl and 0.2 mM PDC in the absence of added Ca2+ and in the presence of 0.5 mM EGTA. Under these conditions stimulus-evoked release was reduced to 7.2±4.2% of that seen in the presence of Ca2+.

Effect of P2 receptor agonists and adenosine on depolarization-evoked glutamate release

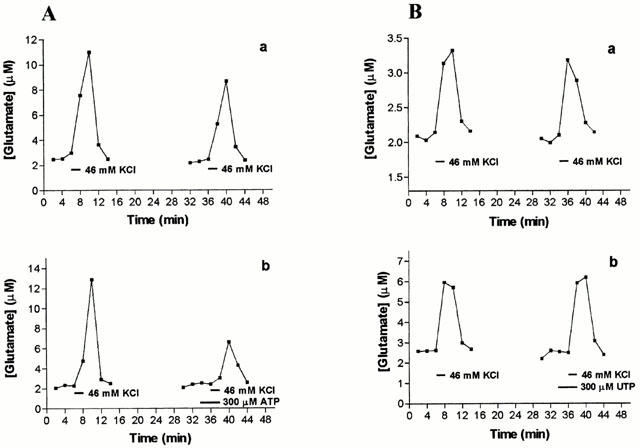

We tested the effect of a range of nucleotides and adenosine on depolarization-evoked glutamate release. None of these compounds had an effect on basal glutamate release. This can be seen for ATP, UTP, ADP and α,β-methylene ATP in the lower panels of the traces in Figures 3 and 4, where the compounds were included alone in the superfusate for 2 min prior to depolarisation.

Figure 3.

Effect of ATP and UTP on stimulus-evoked glutamate release. In each case two consecutive pulses of 46 mM KCl enabled an S2/S1 ratio of areas under peaks to be calculated, in the absence of any other agent (control ratio, upper panels) and in the presence of nucleotides during S2 (treatment ratio, lower panels). (A) ATP (300 μM), (B) UTP (300 μM). A representative experiment is shown here, in which each panel is data collected from aliquots from the same brain slice preparation perfused simultaneously. Results of ratios pooled across experiments are presented in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Effect of ADP and α,β-methylene ATP on stimulus-evoked glutamate release. In each case two consecutive pulses of 46 mM KCl enabled an S2/S1 ratio to be calculated in the absence of any other agent (control ratio, upper panels), and in the presence of nucleotides during S2 (treatment ratio, lower panels). (A) ADP (300 μM), (B) α,β-methylene ATP (300 μM). A representative experiment is shown here, in which each panel is data collected from aliquots from the same brain slice preparation perfused simultaneously. Results of ratios pooled across experiments are presented in Table 1.

Addition of ATP (300 μM) lowered the depolarisation-evoked release of glutamate by 43% (Figure 3A, Table 1). In contrast, 300 μM UTP had no effect on glutamate release (Figure 3B, Table 1). Like ATP, ADP (300 μM) significantly reduced glutamate release during S2 (Figure 4A, Table 1), whereas α,β-methylene ATP, 2MeSATP, or 2MeSADP (each at 300 μM) were without effect (Figure 4B and Table 1).

Table 1.

S2/S1 ratios for nucleotides and adenosine

Adenosine also effectively inhibited K+-evoked glutamate release (Table 1), reducing the S2/S1 ratio by 28%. It is therefore possible that ATP and ADP could influence glutamate release by extracellular breakdown to adenosine and action at P1 (adenosine) receptors. To test this we investigated the effect of the ATP analogue, ATPγS which is relatively resistant to breakdown by ectonucleotidases. ATPγS (300 μM) exerted a similar inhibitory effect to ATP (Table 1), consistent with the notion that breakdown of ATP to adenosine was not required to inhibit glutamate release.

Effect of adenosine deaminase

To further investigate this, the enzyme adenosine deaminase was introduced into the superfusate 2 min prior to the inclusion of adenosine or ATP in S2. If formation of adenosine was required for the action of ATP, the response should be inhibited by the presence of adenosine deaminase in the superfusion buffer. Adenosine deaminase alone (2 u ml−1) increased stimulus-evoked release in each experiment (i.e. higher S2/S1 ratio), but when results were pooled across experiments this effect was not significant. In the presence of the enzyme the ability of adenosine (300 μM) to inhibit glutamate release during S2 was eliminated. However, in the presence of adenosine deaminase (2 u ml−1) ATP (300 μM) was still able to attenuate glutamate release. Expressed as S2/S1 ratios pooled across experiments (n=4–10) the results were: control, 0.77±0.05; adenosine deaminase alone, 1.06±0.12+; adenosine deaminase plus adenosine, 1.10±0.07; adenosine deaminase plus ATP, 0.65±0.09*; (+not significantly different from control; *significantly different from adenosine deaminase alone, P=0.02).

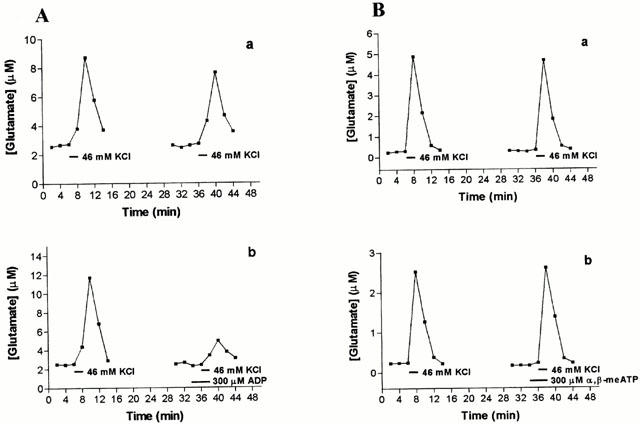

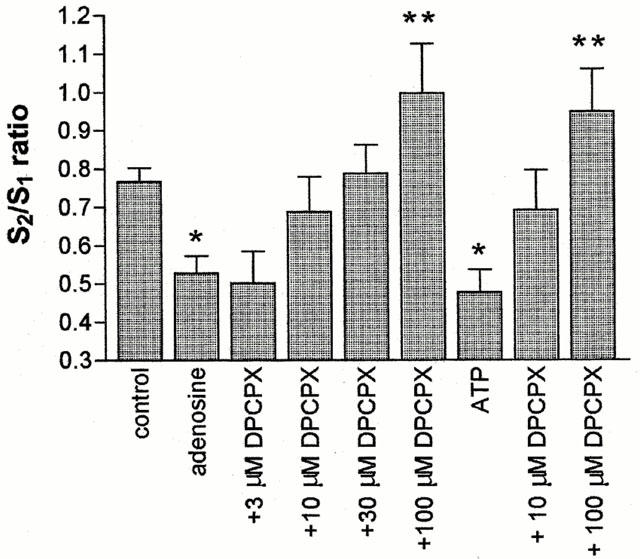

Effect of DPCPX

To further evaluate the role of adenosine receptors in the response to ATP we used DPCPX, an A1 antagonist. DPCPX alone had no effect on glutamate release (data not shown). As shown in Figure 5, DPCPX (10 –100 μM) reversed the effect of adenosine (300 μM) in a concentration dependent manner. However, DPCPX (10 and 100 μM) also reversed the inhibition of K+-evoked glutamate release by 300 μM ATP.

Figure 5.

Effect of DPCPX on inhibition of glutamate release by adenosine and ATP. Rat brain cortical slices were depolarised twice using 2 min pulses of 46 mM K+. The second depolarisation was in the presence of the compounds indicated. DPCPX was introduced 4 min prior to S2, and 300 μM adenosine or 300 μM ATP, 2 min prior to S2. S2/S1 ratios were calculated from the areas under the peaks and plotted as a bar chart (mean±s.e.mean, n=4). By one-way ANOVA the effect of DPCPX in the presence of adenosine was significant at P<0.001 and in the presence of ATP at P<0.05. Using Neumann-Keul's post-test, adenosine and ATP alone were different from controls (*P<0.05) and 100 μM DPCPX in the presence of adenosine or ATP were different from adenosine or ATP alone (**P<0.001).

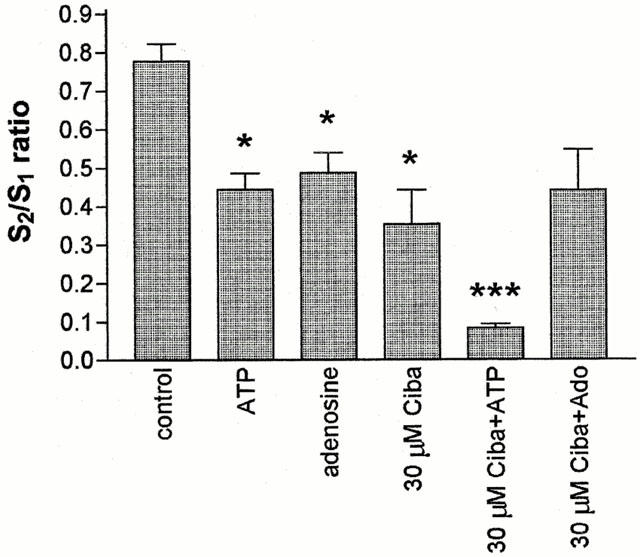

Effect of cibacron blue 3GA

von Kugelgen et al. (1994b) showed that cibacron blue 3GA antagonised presynaptic inhibition of noradrenaline release in the rat cortex by ATP but not by adenosine. We therefore used this P2 antagonist to investigate further the hypothesis that ATP and adenosine act on different receptors when causing the inhibition of stimulus-evoked glutamate release. The results were surprising (Figure 6). Cibacron blue 3GA (30 μM) alone significantly reduced the 46 mM K+-evoked glutamate efflux. Inclusion of both 300 μM ATP and 30 μM cibacron blue 3GA had an additive inhibitory effect on the recorded glutamate output. In three out of four experiments, the depolarisation-evoked glutamate efflux was completely abolished by this treatment. In contrast cibacron blue 3GA had no effect on the inhibitory response to 300 μM adenosine.

Figure 6.

Effect of cibacron blue 3GA (Ciba) on adenosine and ATP inhibition of glutamate release. Rat brain cortical slices were depolarised twice using 2 min pulses of 46 mM K+. The second depolarisation was in the presence of the compounds shown on the x-axis of the graph (ATP and adenosine, 300 μM; cibacron blue 3GA, 30 μM). Glutamate concentrations were determined using the HPLC technique and the areas under the peaks calculated using GraphPad Prism. S2/S1 ratios were calculated and plotted as a bar chart (mean±s.e.mean, n=4 separate experiments, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001).

Discussion

Glutamate is the dominant excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, affecting all aspects of brain function. It seems likely that presynaptic modulation of glutamate release may differ between pathways or brain regions, providing a route for specific drug manipulation of glutamatergic influence. In this study we set out to ask whether adenosine and nucleotides regulate glutamate release from rat brain cortex, following reports that presynaptic P2Y and adenosine receptors regulate biogenic amine release from the brain (von Kugelgen et al., 1994b; Koch et al., 1995; 1997a,1997b).

The increase in glutamate efflux in response to depolarisation with 46 mM K+ was modest in the absence of inhibition of uptake. In rat brain, three glutamate transporter proteins have been isolated; GLAST and GLT-1 are mainly glial and EAAC1 is mainly neuronal. Under the conditions used in these experiments, PDC should not discriminate between these proteins and therefore acts as a non-specific glutamate uptake inhibitor (Swanson et al., 1997). The observation that PDC greatly enhances the efflux of glutamate in response to 46 mM K+ indicates that the uptake mechanisms within the slices remain effective under the experimental conditions used. The results described here established a concentration of PDC which enhanced stimulus-evoked glutamate efflux, with no effect on basal levels of release, enabling PDC to be used in subsequent experiments in a manner analogous to the widespread use of uptake inhibition in the study of biogenic amine release from perfused slices.

The abolition of K+-evoked glutamate efflux in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ in this system is consistent with this being an exocytotic process. We confirmed that high K+ treatment did not cause release as a result of cell disruption by analysis of the serine content of the superfusate samples. Serine is a marker of cell lysis and therefore would not be present at appreciable levels in the superfusate unless cell disruption was occurring. Serine levels did not rise significantly above basal levels during treatment with 46 mM K+ (not shown).

Regulation of glutamate efflux from brain slices may be at the site of release in the nerve terminal. However, if intact neurons are found within the slice it is conceivable that regulation is by action remote from the terminal, at the cell body. In these experiments the stimulus for release was depolarisation with 46 mM K+ in the medium, effectively depolarising the membrane potential at the nerve terminal for the duration of the high K+ pulse. This means that the site of action of adenosine and ATP in regulation of glutamate release in these experiments is likely to be at the nerve terminal close to the site of release.

Both ATP and adenosine, at 300 μM, inhibited stimulus-evoked glutamate efflux. Attempts to generate concentration response curves did not yield suitably reproducible effects below 100 μM when data were pooled across experiments (data not shown). Consequently we were unable to derive EC50 values for agonists.

As ATP and adenosine exerted similar effects, several lines of investigation were pursued to ascertain whether the effect of ATP was direct, or via breakdown by ectonucleotidases to adenosine. Ectonucleotidases have been shown to be abundant and highly active in brain tissue (James & Richardson, 1993; Cunha et al., 1996). Several findings here provide evidence that ATP is acting directly, and not by conversion to adenosine. Firstly the stable ATP analogue ATPγS, which is relatively resistant to breakdown, had the same effect as ATP. Secondly, whilst the addition of adenosine deaminase completely abolished the inhibition of release by adenosine, it did not attenuate the inhibitory effect of ATP. Thirdly, cibacron blue 3GA has different effects on the responses to adenosine and ATP (see below).

It seems likely, therefore, that ATP is acting directly on a receptor which inhibits glutamate release, so we investigated whether a previously characterized P2 receptor is responsible. UTP had no effect on glutamate release, effectively eliminating a role for P2Y2, P2Y4 and P2Y6 receptors at which UTP is an agonist. Similarly the lack of effect of 2MeSATP and 2MeSADP excludes P2Y1 receptors. The agonist potency order of P2Y11 receptors is ATP>2-MeSATP>>ADP. As ATP and ADP gave a similar magnitude of inhibition, and 2MeSATP was ineffective, it seems unlikely that P2Y11 receptors mediate the nucleotide-induced inhibition of depolarisation-evoked glutamate efflux. The failure of both 2MeSATP and α,β-meATP to produce an inhibitory effect rules out all but the P2X7 member of the P2X receptor family. Furthermore, activation of any P2X receptor would be expected to increase neurotransmitter release, in contrast to the inhibition seen here. The results presented therefore are not consistent with the involvement of any of the currently cloned and characterized P2 receptor types. However, as full curves to the agonists could not be constructed, it is impossible to produce an agonist potency order for this system.

The A1 receptor antagonist, DPCPX was found to reverse the effects of both adenosine and ATP in the regulation of glutamate release. This might be taken as evidence that ATP is acting via conversion to adenosine and stimulation of A1 receptors. However, an alternative explanation was offered for an apparently similar finding reported by von Kugelgen et al. (1994b), who showed a presynaptic inhibition of noradrenaline release in the rat cortex by ATP and adenosine. The effects of both adenosine and ATP were blocked by DPCPX, while the P2 antagonist, cibacron blue 3GA was only effective against ATP. This led to the suggestion that two distinct receptors were present; an atypical A1 receptor that responds to both adenosine and ATP, and a P2 receptor at which ATP could act but not adenosine. However, it should be noted that our results differ in several important respects from those of von Kugelgen (1994b). Firstly, cibacron blue 3GA antagonized the response to ATP in their report but had the opposite effect in ours; secondly, they found DPCPX to be effective at much lower concentrations than those used here; thirdly, 2MeSATP mimicked ATP in their study but was without effect in the present study.

Cunha et al. (1994) reported relevant findings in synaptosomes isolated from rat cerebral cortex. They found that the effect of ATP on [3H]-acetylcholine release was not prevented by adenosine deaminase. The effect of both ATPγS and adenosine in the cerebral cortex was prevented by DPCPX. This report also suggests the presence of presynaptic receptors for ATP which are sensitive to DPCPX.

In view of these studies we decided to investigate the effect of cibacron blue 3GA in the stimulus-evoked glutamate release system. We anticipated that it would either inhibit the effect of ATP but not adenosine (as in von Kugelgen et al., 1994b), or do nothing. Surprisingly it did neither. Alone, cibacron blue 3GA inhibited depolarisation-evoked glutamate efflux. The response to adenosine was not affected by the presence of cibacron blue 3GA. When this compound was added together with ATP their inhibitory effects were essentially additive, almost abolishing the K+-evoked efflux of glutamate. This type of effect of cibacron blue 3GA, or of its parent compound reactive blue 2, has not previously been reported. It may be the result of inhibition by cibacron blue 3GA of ectonucleotidases (Koch et al., 1997a), as reported for reactive blue 2 (Bultmann et al. 1999), leading to an increase in activation of inhibitory presynaptic P2 receptors by endogenous ATP. This could account for the inhibitory effect of cibacron blue 3GA alone. It may also reduce the breakdown of exogenous ATP, thereby contributing to a more effective delivery to the site of the receptor. If ATP which is degraded by ectonucleotidases in brain slices is rapidly converted to adenosine, and ATP and adenosine are equally effective at a common receptor in attenuating glutamate release, then inhibition of ectonucleotidases by cibacron blue 3GA would have no effect on the release inhibitory effect of ATP. This is clearly not the case. While the mechanism of action of cibacron blue 3GA remains to be confirmed, it does suggest that ATP and adenosine act at different receptors in modulating depolarisation-evoked glutamate release.

In conclusion we have provided direct evidence that glutamate release from depolarised nerve terminals is subject to inhibitory control by both ATP and adenosine, and that the effect of ATP is not dependent on conversion to adenosine. This study establishes that depolarisation-elicited glutamate release in the brain, like biogenic amine release, is subject to regulation by the presynaptic action of ATP and adenosine. The results may be interpreted as suggesting that ATP and adenosine are acting at separate receptors. It seems likely that presynaptic adenosine and P2 receptors exert a widespread influence on brain function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The BBSRC and Roche Bioscience, Palo Alto, California. We thank Dr Andrew Young (Department of Psychology, University of Leicester) for help establishing the HPLC analysis, Dr C.J. Dixon for help with manuscript preparation and Dr Anthony Ford (Roche Bioscience) for support and discussion.

Abbreviations

- ATPγS

adenosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphoshate)

- DPCPX

8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- 2MeSADP

2-methylthio ADP

- 2MeSATP

2-methylthio ATP

- OPA

o-opthaldehyde

- PDC

L-trans-pyrrolidine-2,4-dicarboxylic acid

References

- ALLGAIER C., PULLMANN F., SCHOBERT A., VON KUGELGEN I., HERTTING G. P2 purinoceptors modulating noradrenaline release from sympathetic neurons in culture. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;252:R7–R8. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90605-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOARDER M.R., HOURANI S.M.O. The regulation of vascular function by P2 receptors: multiple sites and multiple receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOEHM S. Selective inhibition of M-type potassium channels in rat sympathetic neurons by uridine nucleotide preferring receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;116:2341–2343. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BULTMANN R., TRENDELENBURG M., TULUC F., WITTENBURG H., STARKE K. Concomitant blockade of P2X-receptors and ecto-nucleotidases by P2-receptor antagonists: functional consequences in rat vas deferens. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1999;359:339–344. doi: 10.1007/pl00005360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNSTOCK G. Purinergic nerves. Pharmacol. Rev. 1972;24:509–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNSTOCK G. Do some nerve cells release more than one neurotransmitter. Neuroscience. 1976;1:239–248. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(76)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNSTOCK G., DUMSDAY B., SMYTHE A. Atropine-resitant excitation of the urinary bladder: The possibility of transmission via nerves releasing a purine nucleotide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1972;44:451–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1972.tb07283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUHNA R.A., SEBASTIAO A.M., RIBEIRO J.A. Purinergic modulation of the evoked release of [3H]acteylcholine from the hippocampus and cerebral corte of the rat: role of the ectonucleotidases. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1994;6:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUHNA R.A., VIZI E.S., RIBIERO J.A., SEBASTIAO A. Preferential release of ATP and its extracellular catabolism as a source of adenosine upon high- but not low-frequency stimulation of rat hippocampal slices. J. Neurochem. 1996;67:2180–2187. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67052180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDWARDS F.A., GIBB A.J., COLQUHOUN D. ATP receptor-mediated synaptic currents in the central nervous system. Nature. 1992;359:144–147. doi: 10.1038/359144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDHOLM B., ABBRACHIO M.P., BURNSTOCK G., DUBYAK G.R., HARDEN T.K., JACOBSEN K.A., SCHWABE U., WILLIAMS M. Towards a revised nomenclature of P1 and P2 receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:79–82. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(96)01038-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDHOLM B.B., DUNWIDDIE T.V. How does adenosine inhibit transmitter release. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1988;9:130–134. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(88)90194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GU J.G., MACDERMOTT A.B. Activation of ATP P2X receptors elicits glutamate release from sensory neuron synapses. Nature. 1997;389:749–753. doi: 10.1038/39639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAMES S., RICHARDSON P.J. Production of adenosine from extracellular ATP at striatal cholinergic synapse. J. Neurochem. 1993;60:219–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb05841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOCH H., KUGELGEN I., STARKE K. P2-receptor-mediated inhibition of noradrenaline release in the rat hippocampus. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's. Arch. Pharmacol. 1997a;355:707–715. doi: 10.1007/pl00005003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOCH H., TRENDELENBERG A.U., BULTMANN R., VON KUGELGEN I., STARKE K. P2-purinoceptors inhibiting the release of endogenous dopamine in rat neostriatum. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1997b;355:R33. [Google Scholar]

- KOCH H., VON KUGELGEN I., STARKE K. Presynaptic P2-purinoceptors at serotininergic axons in rat brain cortex. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1995;352:R21. [Google Scholar]

- KOIZUMI S., INOUE K. Inhibition by ATP of calcium oscillations in rat cultured hippocampal neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:51–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KURZ K., VON KUGELGEN I., STARKE K. Prejunctional modulation of noradrenaline release in mouse and rat vas deferens: Contribution of P1 and P2-purinoceptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:1465–1472. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANZONI O.J., TOSHIYA M., NICOLL R.A. Release of adenosine by activation of NMDA receptors in the hippocampus. Science. 1994;265:2098–2101. doi: 10.1126/science.7916485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MELDRUM L.A., BURNSTOCK G. Evidence that ATP acts as a cotransmitter with noradrenaline in sympathetic nerves supplying the guinea-pig vas deferens. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1983;92:161–163. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(83)90126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIEBER K., POELCHEN W., ILLES P. Role of ATP in fast excitatory synaptic potential in locus coeruleus neurons of the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:423–430. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORENBERG W., VON KUGELGEN I., MEYER A., ILLES P., STARKE K. M-type K+ currents in rat cultured thoracolumbar sympathetic neurons and their role in uracil nucleotide-evoked noradrenaline release. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:709–731. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATON D.M.Presynaptic neuromodulation mediated by purinergic receptors Purinergic receptors 1981Chapman and Hall: London; 199–219.ed. Burnstock, G. pp [Google Scholar]

- SHEN K.-Z., NORTH R.A. Excitation of rat locus coeruleus neurons by adenosine 5′-triphosphate: ionic mechanism and receptor characterisation. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:894–899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-00894.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHINOZUKA K., BJUR R.A., WESTFALL D.P. Characterisation of prejunctional purinoceptors on adrenergic nerves of the rat caudal artery. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1988;338:221–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00173391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SILINSKY E.M., GINSBORG B.L. Inhibition of acetylcholine release from preganglionic frog nerves by ATP but not adenosine. Nature. 1983;305:327–328. doi: 10.1038/305327a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWANSON R.A., LIU J., MILLER J.W., ROTHSTEIN J.D., FARRELL K., STEIN B.A., LONGUEMARE M.C. Neuronal regulation of glutamate transporter subtype expression in astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:932–940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00932.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VOLTERRA A., BEZZI P., RIZZINI B.L., TROTTI D., ULLENSVANG K., DANBOLT N., RACAGNI G. The competitive transport inhibitor L-trans-pyrrolidine-dicarboxylate triggers excitotoxicity in rat cortical-astrocyte co-cultures via glutamate release rather than uptake inhibition. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1996;8:2019–2029. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON KUGELGEN I., ALLGAIER C., SCHOBERT A., STARKE K. Corelease of noradrenaline and ATP from cultured sypathetic neurons. Neuroscience. 1994a;61:199–202. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON KUGELGEN I., SPATH L., STARKE K. Evidence for P2-purinoceptor-mediated inhibition of noradrenaline release in rat brain cortex. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994b;113:815–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON KUGELGEN I., STOFFEL D., STARKE K. P2-purinoceptor mediated inhibition of noradrenaline release in rat atria. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:247–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBB T.E., SIMON J., BATESON A.N., BARNARD E.A. Transient expression of the recombinant chick brain P2Y1 receptor and localisation of the corresponding mRNA. Mol. Cell Biol. 1994;40:437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WICKLUND N.P., GUSTAFSSON L.E., LUNDIN J. Pre- and postjunctional modulation of cholinergic neuroeffector transmission by adenine nucelotides. Experiments with agonist and antagonist. Acta Physiologica Scand. 1985;125:681–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1985.tb07771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG Y.X., YAMASHITA H., OHSHITA T., SAWAMOTO N., NAKAMURA S. ATP increases extracellular dopamine level through stimulation of P2Y purinoceptors in the rat striatum. Brain Res. 1995;691:205–212. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00676-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]