Abstract

Spontaneously opening, chloride-selective channels that showed outward rectification were recorded in ripped-off patches from rat cultured hippocampal neurons and in cell-attached patches from rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in slices.

In both preparations, channels had multiple conductance states and the most common single-channel conductance varied. In the outside-out patches it ranged from 12 to 70 pS (Vp=40 mV) whereas in the cell-attached patches it ranged from 56 to 85 pS (−Vp=80 mV).

Application of GABA to a patch showing spontaneous channel activity evoked a rapid, synchronous activation of channels. During prolonged exposure to either 5 or 100 μM GABA, the open probability of channels decreased. Application of GABA appeared to have no immediate effect on single-channel conductance.

Exposure of the patches to 100 μM bicuculline caused a gradual decrease on the single-channel conductance of the spontaneous channels. The time for complete inhibition to take place was slower in the outside-out than in the cell-attached patches.

Application of 100 μM pentobarbital or 1 μM diazepam caused 2–4 fold increase in the maximum channel conductance of low conductance (<40 pS) spontaneously active channels.

The observation of spontaneously opening GABAA channels in cell-attached patches on neurons in slices suggests that they may have a role in neurons in vivo and could be an important site of action for some drugs such as benzodiazepines, barbiturates and general anaesthetics.

Keywords: GABAA receptors, anaesthetics, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, diazepam, inhibition, bicuculline, single channel conductance, gating, current potentiation

Introduction

The ubiquitous, inhibitory GABAA receptor is thought to be a hetero-pentamer with two GABA binding sites and the channel is assumed to be formed by the second transmembrane segments of the five subunits (Unwin, 1993; Barnard et al., 1998). It is well established that the conductance state of a GABAA receptor can vary and prominent subconductance states are a characteristic feature of the receptor (Mathers, 1991; Sivilotti & Nistri, 1991; MacDonald & Olsen, 1994). The maximum conductance varies among different neuronal preparations and it can at least be modulated by the benzodiazepines (Mathers, 1991; MacDonald & Olsen, 1994; Rabow et al., 1996, Eghbali et al., 1997; Guyon et al., 1999). Work on reconstituted receptors indicates that the variable maximum conductance observed is in part related to the subunit composition of the receptors (Rabow et al., 1996). Considering the number of GABAA subunits that can form pentamers (20 subunits, Barnard et al., 1998), a variety of single-channel conductances is not unexpected (Mathers, 1991; MacDonald & Olsen, 1994; Rabow et al., 1996).

We and others have shown previously that GABAA channels can open spontaneously (Hamill et al., 1983; Mathers, 1985; Huck & Lux, 1987; Weiss et al., 1988; MacDonald et al., 1989; Birnir et al., 2000). We have now examined in greater detail the effect of GABA, bicuculline, pentobarbital and the benzodiazepine diazepam on the spontaneous channel conductance. The channels were recorded in ripped off patches from cultured hippocampal neurons and in cell-attached patches on CA1 pyramidal neurons in the rat hippocampal slice preparation. One-hundred μM GABA increased the open probability of the channels but did not appear to have any immediate effect on the channel conductance. One-hundred μM bicuculline gradually decreased whereas 100 μM pentobarbital or 1 μM diazepam increased the average channel conductance. A preliminary account of some of these observations has appeared elsewhere (Gage et al., 1998; Birnir et al., 1999).

Methods

Cultured neurons

Neurons used in the experiments were dissociated from hippocampal slices from newborn rats and maintained in culture for 8 to 24 days using techniques described previously (Curmi et al., 1993). Experiments were done at room temperature (20–24°C) on outside-out or inside-out patches. Channels were activated either by switching the solution flowing through the bath to a solution containing GABA or by flowing a solution containing GABA through a narrow tube superfusing the patch. The second method gave a rapid change in GABA concentration (Birnir et al., 1995). In most experiments, the pipette potential was +40 mV since GABAA channels are more active at depolarized than at hyperpolarized potentials (Weiss et al., 1988; Birnir et al., 1994). Bath solution contained (mM): NaCl 135, KCl 3, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, TES (N-tris(hydroxymethyl) methyl-2-amino ethane sulphonic acid) 10, pH 7.4. In some experiments in which the reversal potential of currents was examined, 116 mM NaCl was replaced with 116 mM Na gluconate. Pipette solution contained (mM): NaCl or choline Cl 141, KCl 0.3, CaCl2 0.5, MgCl2 2, EGTA (ethylene glycol-bis (b-aminoethylether)tetraacetic acid) 5, TES 10, pH 7.4. In some experiments, the pipette also contained 4 mM ATP (adenosine triphosphate) but this had no detectable effect.

Hippocampal slices

Rat hippocampal slices were prepared as described previously (Collingridge et al., 1984). Briefly, a 17–21-day-old rat was anaesthetized and then decapitated. The brain was removed and put into ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (mM): 124 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 3 KCL, 1.3 MgSO4, 2.5 NaH2PO4, 2.5 CaCl2 and 20 glucose. The pH of this solution, when equilibrated with a gas mixture containing 95% O2 and 5% CO2, was 7.4. The cerebellum was removed and the brain bisected. The hemi-brain was glued to the cutting stage and immediately submerged in ice-cold ACSF. Slices about 400 μm thick were cut normal to the septo-temporal axis using a vibrating microslicer (Camden Instruments). The slices were removed and put onto a petri dish containing ice-cold ACSF. The hippocampus was gently separated from the surrounding brain tissue and put into a chamber containing ACSF at 35°C and incubated for an hour. At the end of the incubation period, the chamber containing the slices was removed and stored at room temperature. One of the slices was put in a recording chamber and held in place by a grid of parallel nylon threads glued to a u-shaped platinum frame. A standard dissecting microscope (Wild M5) was used to view the slices. The bath solution contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 10 HEPES or TES adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The patch pipette normally contained (mM); 140 choline Cl, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 10 HEPES (N-[2-Hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N′-[2-ethanesulphonic acid]) or TES pH 7.4. In four experiments the pipette solution contained 75 mM NaCl and 75 mM choline Cl (e.g. in experiment shown in Figure 7). Similar spontaneous channels with the same reversal potential were recorded in the two solutions. For injection of drugs to a patch in the cell-attached configuration, a bolus of drug preceded by air (to prevent diffusion from the tube) was ejected from the end of a fine teflon tube threaded down the patch pipette to within 0.5 to 1 mm from the pipette tip (Curmi et al., 1993). The tube was connected to a drug reservoir. By briefly increasing the air pressure in the reservoir, solution was forced into the pipette tubing to deliver solution containing a drug to the patch surface.

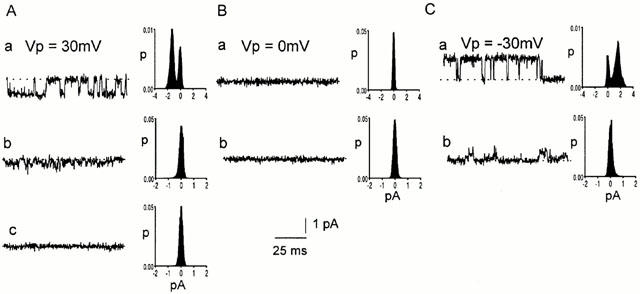

Figure 7.

No effect of bicuculline on the reversal potential of channels in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Spontaneously opening channels were recorded in a cell-attached patch before (a) and after (b, c) injection of 100 μM bicuculline into the pipette tip. Representative current traces are shown at pipette potentials of: A. 30 mV, B. 0 mV and C. −30 mV. Histograms from 10 s current records are shown alongside each trace. The dotted lines represent the level of the baseline current.

Recording current

Conventional patch-clamp techniques were used when establishing a gigaseal and forming patches (Hamill et al., 1981). Pipettes were made from borosilicate glass (Clark Electromedical), coated with Sylgard (Dow Corning) and fire-polished. Their resistance ranged from 10 to 20 MΩ. Currents were recorded using an Axopatch 1C or 200 A current-to-voltage converter (Axon instruments), filtered at 5 kHz, digitized at 44 kHz using a pulse code modulator (Sony PCM 501) and stored on videotape. The currents were played back from the video tape through the Sony PCM and digitized at frequency of 10 kHz using a Tecmar analogue-to-digital converter interfaced with an IBM-compatible PC. The currents were then digitally filtered (Gaussian filter) at 5 (or occasionally 2) kHz and analysed using a computer program called CHANNEL2 written by Michael Smith (JCSMR, A.N.U., Canberra). The amplitude of currents was measured either from all-points current amplitude probability histograms or from direct measurements of the amplitude of individual currents filtered at 5 kHz. We use the terms ‘single-channel current' or ‘single-channel conductance' for the maximum current or conductance levels observed that showed direct transitions to or from the zero current or conductance levels more frequently than would be expected from the opening and closing of two or more independent channels. Lower conductances are called ‘subconductance' states. The average open probability of channels was measured from opening and closing transitions detected by setting thresholds levels just above the baseline noise. For illustrative purposes current traces were sometimes filtered at 2 kHz unless this distorted current levels recorded with a 5 kHz filter (The filter frequency is specified in the figure legends). A correction was made for junction potentials using JPCalc (P.H. Barry, U.N.S.W., Sydney) where appropriate. Data are expressed as means±s.e.mean (n=number of patches).

Drugs

γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA, Sigma), pentobarbital (Sigma) and bicuculline methiodide (Sigma) were dissolved in the bath solution. Diazepam (Hoffman-La Roche) was first dissolved in DMSO (dimethylsulphoxide) as described by Eghbali et al. (1997).

Results

Characteristics of spontaneous channels

Spontaneous single-channel currents were seen in 81 of 190 outside-out patches excised from cultured hippocampal neurons. The maximum conductance of these spontaneous channels varied from patch to patch, ranging from 12 pS to 70 pS. Channels with different conductances in three patches are shown in Figure 1A (Vp=+60 mV): 66 pS (Aa), 42 pS (Ab) and 25 pS (Ac). For comparison, in outside-out patches from the same neurons in which no channel activity was detected before GABA application, the conductance of channels activated by GABA ranged from 10 to 120 pS (Vp=40 mV, Birnir et al., 1999). In all of the 81 patches with spontaneous channels, the zero current (null) potential was 0 mV, the chloride equilibrium potential. Single-channel current-voltage curves from data obtained over a range of potentials in eight patches gave a null potential of 0 mV. The null potential was not affected by the nature of the major cation, which was either sodium or choline. IV curves for three channels with conductances (Vp=+60 mV) of 25 pS (open diamonds), 37 pS (open circles) and 66 pS (open squares) are shown in Figure 1B. The chloride-selectivity of the spontaneous channels was examined further in three experiments, one of which is illustrated in Figure 1B. Initially the patch was exposed to symmetrical chloride solutions (146 mM) and the current-voltage (IV) relationship recorded (open circles). The patch was then exposed to bath solution containing 30 mM chloride (see methods), which shifts the chloride equilibrium potential to +40 mV and the IV relationship was recorded again (filled circles). As expected for a chloride-selective current (EC1=+38 mV), the null potential was now close to +40 mV. The IV relationship showed outward rectification in both the symmetrical and the asymmetrical chloride solutions. Similar outward rectification has been reported for GABA-gated channels in cultured neurons and in guinea-pig and rat hippocampal slices (Gray & Johnston, 1985; Fatima-Shad & Barry, 1992; Curmi et al., 1993; Birnir et al., 1994).

Figure 1.

Spontaneous channels in outside-out patches. (A) Variable conductance. Current records from three different outside-out patches from cultured hippocampal neurons (a–c) at a potential of +60 mV. The maximum conductance of the channels was 66 (Aa), 42 (Ab) and 25 pS (Ac). Currents were digitally filtered at 2 kHz. The corresponding all-points histograms on the right of each trace are from 10 s current records. The dotted lines represent the level of the baseline current. (B) Chloride selectivity. Single-channel current amplitudes are plotted against the pipette potential for three different outside-out patches (open circle, diamond and square). All currents reversed at 0 mV. In one of the patch currents were first recorded in symmetrical Cl− solutions (146 mM, open circles) and then currents were recorded again when the bath Cl− concentration had been lowered to 30 mM (iso-osmolality was maintained with gluconate, filled circles). The reversal potential of the currents was shifted to +38 mV.

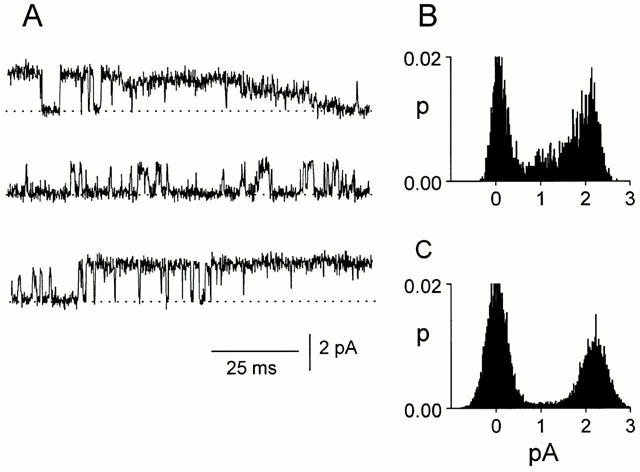

Similar results were obtained in cell-attached patches on CA1 pyramidal neurons in rat hippocampal slices. The most common single-channel conductance varied between patches e.g. in 10 patches, it ranged from 56 to 85 pS (−Vp=80 mV). In all 10 patches, the currents reversed at Vp=0 mV. Even in the same patch, the conductance of channels could vary widely, as illustrated in Figure 2 (the three traces in Figure 2A are continuous). In this patch, the most common conductance of the channel was 55 pS (−Vp=40 mV) but the channel could clearly exist in several conducting states. Particularly intriguing is the current behaviour observed in the first trace in Figure 2A in which the single channel current appears to decrease progressively to a very low level. The multiple levels in the traces in Figure 2A are apparent in the all-points histograms in Figure 2B. However, the maximum conductance was the most common conductance as can be seen in the all-points histogram in Figure 2C obtained from a 3 s current record from the same patch.

Figure 2.

Conductance states of channels in CA1 pyramidal neurons. The channels can adopt various conductance states but subconductance states are not as frequent as the main, largest conducting state. (A) The current traces are from a cell-attached patch at a pipette potential of −40 mV and are continuous. (B) All-points histograms from the 300 ms of current trace shown in (A). (C) All-points histogram from the same patch as in (B) but from a longer (3 s) current record.

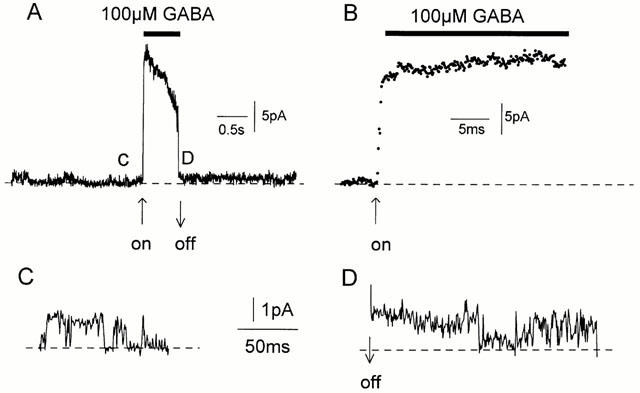

Channels activated by GABA

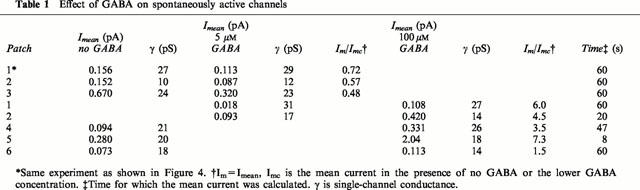

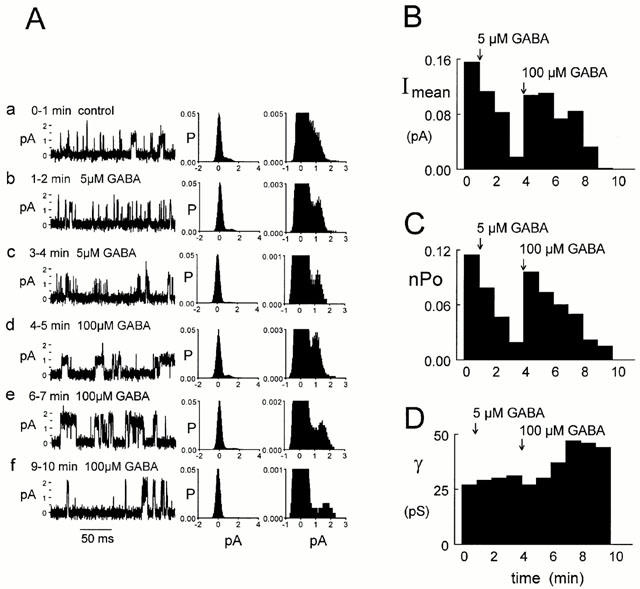

When 100 μM or 10 mM GABA was applied to an outside-out patch containing spontaneous channels, a rapid increase in channel activity was observed (n=6). An example is shown in Figure 3A. The patch had spontaneous channels with a single channel current of 1.5 pA and conductance of about 37 pS (Vp=+40 mV, Figure 3Ac, C). When 100 μM GABA was applied to the patch (horizontal bar), there was a burst of channel activity, the current rapidly increased to 21 pA and then started to decay. The rate of current rise was fast and had reached 80% of its peak-amplitude within 700 μs (Figure 3B). When GABA application was stopped, the current rapidly decreased. The single-channel conductance immediately after the GABA application was the same as before GABA application, about 37 pS (Figure 3Ad, D). The characteristics of single channels activated immediately by GABA could not be examined in most patches because of the great increase in channel activity during the drug application. However, in six patches, single-channel currents were not superimposed during the GABA application. The mean currents and the single channel conductance recorded in theses patches are given in Table 1. When 5 μM GABA was applied, the mean current decreased whereas when the patch was exposed to 100 μM GABA, the mean current increased. As the GABA concentration did not affect the single-channel conductance, GABA must affect the open probability of the channels and, presumably, also their desensitization. Results from one of these patches that was held for over 10 min and could be exposed to both 5 and 100 μM GABA are shown in Figure 4 (Vp=+40 mV). Representative current traces (200 ms) and corresponding 1 min all-points current amplitude probability histograms are shown in Figure 4A. The patch was held for 10.7 min and Figure 4Aa shows spontaneous channel currents recorded in the absence of GABA. The patch was then exposed to 5 μM GABA (Figure 4Ab,c) and 3 min later to 100 μM GABA (Figure 4Ad–f). The mean currents, open probability and channel conductance were measured over 1 min periods and the results are shown in Figure 4B–D. Before exposure to GABA the mean current was 0.155 pA (Figure 4B). During the three minutes the patch was exposed to 5 μM GABA the mean current gradually decreased to 0.018 pA but increased to 0.108 pA when 100 μM GABA was applied. In this patch, only exposure to 100 μM GABA initially increased the open probability of the channels over the first 1 min (Figure 4C). The decay of the mean current was slower in the presence of 100 μM GABA. The changes in the mean current were largely caused by changes in channel open probability, as illustrated in Figure 4C. Effects of GABA on channel conductance are shown in Figure 4D. The conductance was determined from the peak in the all-points histograms shown in Figure 4A. Exposure of patches containing spontaneous channels to 100 μM GABA appeared to increase the channel conductance. Before exposure to GABA, the channel conductance was 27 pS and remained at about 30 pS in the presence of 5 μM GABA. During the first 2 min of exposure to 100 μM GABA, the single channel conductance was 27–30 pS. In the third minute, however, channel conductance had increased to 37 pS and after 4 min in 100 μM GABA channel conductance was 47 pS: no further increase was observed. Concomitant with the shift in the peak current amplitude to the right was the disappearance of the lower channel current (see Figure 4A).

Figure 3.

Rapid activation of channels by GABA. (A) 100 μM GABA was rapidly applied (horizontal bar) to an outside-out patch (Vp=+40 mV) containing spontaneously active 37 pS channels (see C). The ‘peak' current response was 21 pA (525 pS). (B) The rising phase of the current shown in (A) at a faster time scale. The data points are at 100 μs intervals. (C). Spontaneous single-channel currents before GABA application. (D) Spontaneous single-channel currents immediately after GABA application was stopped.

Table 1.

Effect of GABA on spontaneously active channels

Figure 4.

GABA modulation of spontaneous channels recorded in an outside-out patch. (A) Traces (200 ms) of single-channel currents under the conditions shown above each trace (a–f). One-minute all-points histograms are shown on two vertical scales alongside each trace. The vertical scale on the histograms to the right was chosen to emphasise the peak representing the open channel currents. The dotted lines represent the level of the baseline current. Currents were filtered at 5 kHz. (B) Mean current (Imean). The mean current was determined in successive 1 min periods after patch formation (Vp=+40 mV). Five and 100 μM GABA were applied after 1 and 4 min, respectively. (C) Channel open probability (nPo). Results were obtained from the same current record as used in (B) and the open probability was determined in 1 min consecutive current segments. (D) Channel conductance as a function of time. The conductance was determined from the peak in consecutive 1 min all-points current amplitude histograms.

Effects of drugs

Bicuculline

Bicuculline is normally classified as a competitive GABA antagonist but there is increasing evidence that it can also act as an allosteric inhibitor at GABAA receptors (Barker et al., 1987; Ueno et al., 1997; Birnir et al., 2000). As 50 μM bicuculline reduced spontaneous single-channel conductance in a cell attached patch on a CA1 neuron in the hippocampal slice from 60 to only 40 pS and 100 μM bicuculline was required to inhibit channels activated by 100 μM GABA in outside-out patches from the cultured neurons (unpublished observation), we examined the effect of 100 μM bicuculline on the spontaneously opening chloride channels.

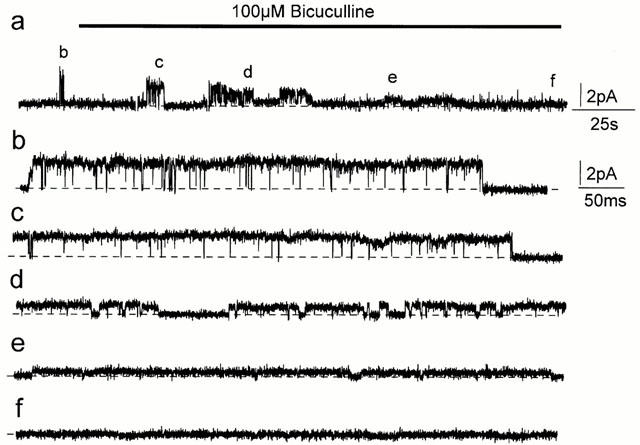

In the outside-out patches from the cultured neurons, 100 μM bicuculline blocked spontaneous chloride channels whether they had a high (>40 pS, n=4) or low (<40 pS, n=11) conductance. The effect of 100 μM bicuculline on spontaneously opening channels is illustrated in Figure 5. The experimental record is shown condensed in Figure 5a (3.8 min, Vp=+60 mV). Channels on a faster time scale are shown in Figure 5b–f. Before exposure to bicuculline, the maximum conductance of spontaneous channels was 42 pS (Figure 5a, b). When the patch was exposed to 100 μM bicuculline, channel conductance decreased gradually as illustrated in Figure 5a. At 0.5, 1.1 and 2.1 min after exposure to the bicuculline, single-channel conductances were 30, 15 and 8 pS, respectively (Figure 5c–e). 3.1 min after the bicuculline application, no channel activity was observed (Figure 5a,f). In four experiments where the initial conductance in the different patches ranged from 20 to 65 pS, bicuculline caused a gradual decrease in channel conductance.

Figure 5.

Bicuculline inhibition of spontaneously active channels. (A) 100 μM bicuculline inhibited spontaneous channel currents recorded in an outside-out patch from cultured hippocampal neurons (Vp=+60 mV). (a) A compressed 3.8 min current trace. Initially the maximum channel conductance was 42 pS (b) but after exposure to bicuculline (c–f) it decreased gradually. The conductances were 30 (c), 15 (d), 8 (e) and 0 pS (f) at 0.5, 1.1, 2.1 and 3.1 min after bicuculline application started, respectively. The horizontal bar denotes the bicuculline application and the breaks in the current record are due to brief changes in the holding potential. Currents are filtered at 5 kHz. Calibration bars for trace a are shown beside the trace. Calibrations for traces (b–f) are beside trace (b). The dotted lines represent the level of the baseline current.

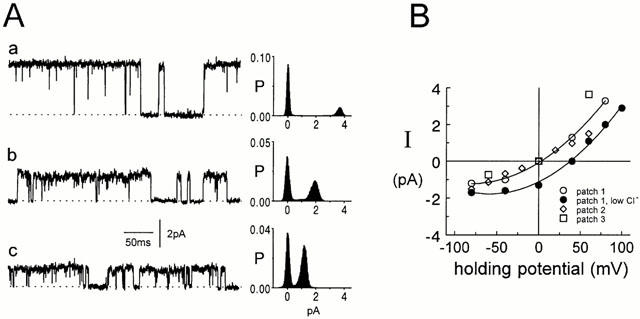

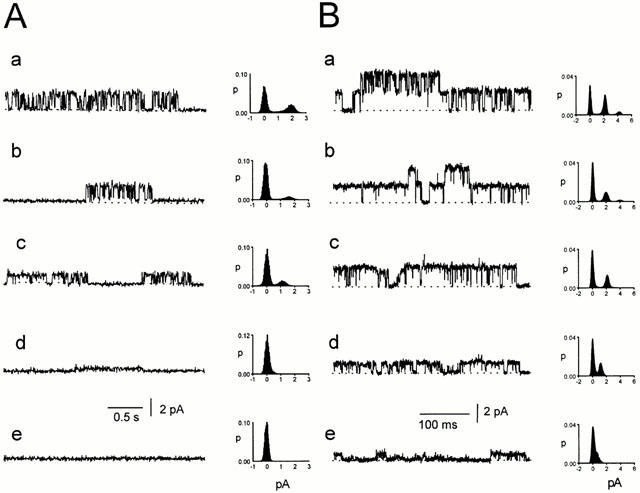

Similar results were obtained in cell-attached patches on neurons in slices when 100 μM bicuculline was injected into the pipette tip. The effects of 100 μM bicuculline on spontaneous channels in one of these patches can be seen in Figure 6A. Again the striking feature of the inhibitory effect of the bicuculline is the reduction in current amplitude. The accompanying histograms are each from a 10 s current record and are in continuous time sequence after the bicuculline injection. They illustrate the effect of the bicuculline on both channel conductance and open probability. Before introduction of the bicuculline (Figure 6Aa) average channel conductance was about 50 pS. The succeeding traces taken 5, 15 and 25 s after bicuculline injection into the pipette tip show channels with average conductances of 40, 29 and 9 pS, respectively (Figure 6Ab–d). After about 40 s (Figure 6Ae), no spontaneous activity could be seen. Similar inhibition of spontaneous single-channel currents by bicuculline was obtained in all seven patches in which the effects of bicuculline were tested.

Figure 6.

Effects of bicuculline on spontaneous channels in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Spontaneously opening channels were recorded in a cell-attached patch on CA1 hippocampal neurons in the slice preparation at a pipette potential of −40 mV. (A) 100 μM bicuculline was then injected into the tip of the patch pipette. Initially the maximum channel conductance was 50 pS (a) but after exposure to bicuculline (b–e) it decreased gradually. The conductances were 40 (b), 29 (c), 9 (d) and 0 pS (e) at 5, 15, 25 and 40 s after bicuculline application, respectively. The all-points histograms were each obtained from 10 s current records and are in time sequence after bicuculline injection. The dotted lines represent the level of the baseline current. (B) Effect of 100 μM bicuculline plus GABA. (a) The all-points histogram is from 16 s of current record before bicuculline and GABA were injected into the pipette tip. (b–e). Each histogram is from 2 min of current record after bicuculline plus GABA had been injected into the pipette tip. The representative current traces shown were recorded 0.3 min (b), 3.3 min (c), 5.6 min (d) and 7.9 min (e) after injection of bicuculline plus GABA.

The records in Figure 6B were obtained from a patch on a CA1 neuron in a slice. Before injection of 100 μM bicuculline, now together with 0.5 μM GABA, into the pipette tip, there was evidence of two active channels in the patch, each with a conductance of 55 pS. Three minutes after injection of GABA and bicuculline into the pipette tip, only one channel with average conductance of 54 pS was still active (Figure 6Bc) and 5 and 7 min later the average channel conductance had dropped to 30 and then to 15 pS, respectively (Figure 6Bd, e). Again, the decrease in channel conductance with time is clearly demonstrated by the shift to lower current values in the all-points current-amplitude histograms. The histograms obtained after injection of the drugs are in time sequence and each represents 2 min of current record. In the presence of the low concentration of GABA (0.5 μM), the decrease in channel conductance appeared to be slower but followed a pattern similar to that observed for spontaneous channels in the absence of GABA. These results are similar to what was recorded for bicuculline inhibition of GABA-activated channels on dentate gyurus neurons in slices (Birnir et al., 1994).

The reduction in the current amplitude when bicuculline was injected into the pipette was not due to a change in the driving force on the ions flowing through the channel. This is illustrated in Figure 7. Before bicuculline application, average channel conductance was 43 pS when the Vp was +30 mV (Figure 7Aa) and 53 pS when Vp was −30 mV (Figure 7Ca). The null (zero current) potential was at Vp=0 mV (Figure 7Ba). After bicuculline (100 μM) was injected into the pipette tip, channels at a pipette potential of +30 mV had a reduced conductance of 13 pS (Figure 7Ab) and the null potential was at a Vp of 0 mV, as before (Figure 7Bb). At a Vp of −30 mV, the channel conductance had decreased to about 20 pS (Figure 7Cb). Complete blockage of channels by the bicuculline was later observed (Figure 7Cc). Similar results were obtained in two other experiments. Since the null potential for the single-channel currents remained at a Vp close to 0 mV as the currents became smaller, the driving force on the ions did not change so that the changes in current amplitude must have been due to changes in channel conductance.

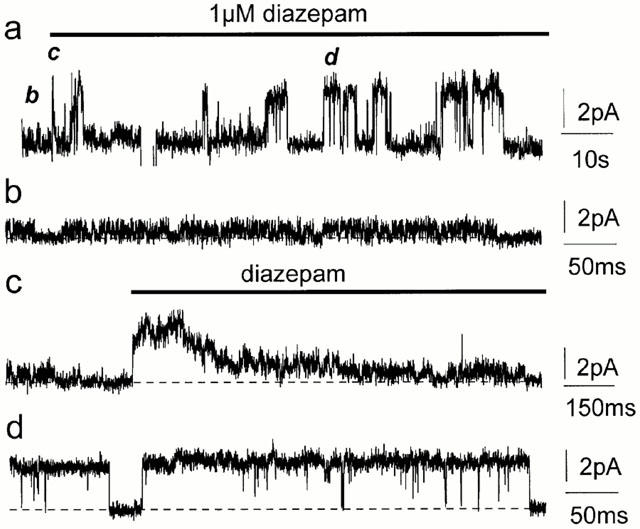

Diazepam

Benzodiazepines specifically increase GABAA channel activity (MacDonald & Olsen, 1994; Rabow et al., 1996) and have recently been reported also to increase channel conductance (Eghbali et al., 1997; Guyon et al., 1999). In three experiments in which outside-out patches with spontaneous channels were exposed to 1 μM diazepam, channels were modulated by the drug. One of these experiments is illustrated in Figure 8 (Vp=+40 mV). We used 1 μM diazepam since we found it to be the most effective concentration of diazepam in modulating GABAA channel conductance in the neurons used in this study (Eghbali et al., 1997). Changes caused by diazepam are shown in a condensed record in Figure 8a (1.7 min). Channels on a faster time scale are shown in Figure 8b–d. Initially the single-channel current amplitude was 0.9 pA (22 pS, Figure 8a,b). When 1 μM diazepam was applied to the patch, there was a rapid increase in current amplitude to 3.1 pA (77 pS) that then decreased (Figure 8a,c). Later, single channels maintained the high conductance state (77 pS, Figure 8a,d). The conductance returned to about 20 pS when the drug was flushed out with bath solution (not shown). In another patch, channel conductance increased from 56 pS to 98 pS in the presence of 1 μM diazepam whereas in a third patch the increase in the channel conductance was about 2 fold. Diazepam alone did not activate channels when applied to silent outside-out patches. The increase in conductance observed in the presence of diazepam is greater than the effect on the high conducting (>40 pS) spontaneous channels recorded in cell-attached patches in the slice preparation (Birnir et al., 2000) but similar to the increase recorded in GABA-activated channels from cultured neurons (Eghbali et al., 1997).

Figure 8.

Diazepam modulation of spontaneously active channels. Diazepam enhanced spontaneous channel currents in outside-out patches from cultured hippocampal neurons (Vp=+40 mV). (a) A compressed 1.7 min current trace, the letters (b–d) refer to the traces that follow and show the corresponding section of the experiment at a faster time scale. Initially the maximum spontaneous channel conductance was about 22 pS (a,b). The channel conductance increased rapidly to 77 pS when exposed to 1 μM diazepam but then decreased (a,c). 77 pS channels were later maintained in the presence of 1 μM diazepam (a,d). The horizontal bar in (a,c) denote the diazepam application and breaks in the current record are due to brief changes in the holding potential. The dotted lines represent the level of the baseline current. Currents are filtered at 5 kHz. Calibrations for each trace are shown on the right.

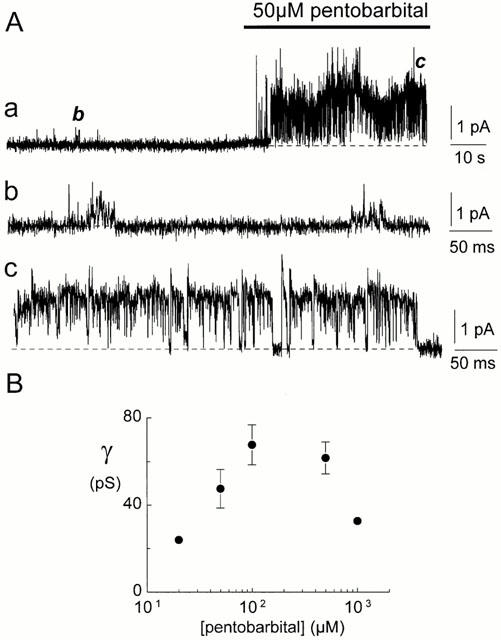

Pentobarbital

Barbiturates enhance GABAA channel activity (MacDonald & Olsen, 1994; Rabow et al., 1996). An example of the effect of pentobarbital on the conductance of spontaneously active channels is shown in Figure 9. The spontaneous channels in Figure 9A had an average current amplitude of 0.63 pA (Figure 9Aa,b, 16 pS) before application of 50 μM pentobarbital. Following application of pentobarbital, the average single channel current increased to 1.7 pA (Figure 9Aa,c, 43 pS). The results from a number of similar experiments are shown in Figure 9B. In ten inside-out and four outside-out patches, we examined the effects of a range of pentobarbital concentrations on the spontaneously active channels. Before application of pentobarbital, the average conductance of the channels was 15±2 pS. The increase in conductance of the channels caused by pentobarbital was dependent on the pentobarbital concentration. The maximal single-channel conductance of 68±9 pS was recorded in the presence of 100 μM pentobarbital. For comparison, in 13 inside-out patches in which no channel activity was detected before pentobarbital application, 100 μM pentobarbital activated 30±2 pS channels. At 1 mM concentration the single-channel conductance was depressed (Figure 9B).

Figure 9.

Pentobarbital modulation of spontaneously active channels. (A) Pentobarbital enhanced spontaneous channel currents in an inside-out patch from cultured hippocampal neurons (Vp=−40 mV). (a) A compressed 2.2 min current trace where the horizontal bar denotes the pentobarbital application. Initially the average spontaneous channel conductance was about 16 pS (a,b). The average channel conductance increased when the patch was exposed to 50 μM pentobarbital (a,c, 43 pS). The dotted lines represent the level of the baseline current. The current trace in (a) is filtered at 2 kHz, the traces in (b,c) at 5 kHz. Calibrations for each trace are shown on the right. (B) The effect of pentobarbital concentration on the average single-channel conductance of the spontaneously active channels. The data were obtained from ten inside-out and four outside-out patches. Data points represent the mean conductance±s.e.mean if larger than the symbol. The average conductance of the spontaneously active channels before exposure to pentobarbital was 15±2 pS.

Discussion

Our aim was to study characteristics of spontaneous GABAA channels and how drugs affected them. We mainly used outside-out patches from cultured neurons because they regularly exhibit spontaneous channel activity and the drug concentration at the surface of the patch is known. Since in the outside-out patch configuration the receptors are not in contact with the normal intracellular milieu and cellular structure, we compared the results on outside-out patches to drug effects obtained on spontaneous channels recorded in cell-attached patches on intact neurons in slices.

The spontaneous channels in the outside-out patches were chloride-selective, blocked by bicuculline and modulated by both pentobarbital and diazepam. Application of high GABA concentrations caused a rapid increase in channel activity whereas prolonged exposure to GABA decreased channel open probability. It was concluded, therefore, that the channels were GABAA channels. Spontaneous channel activity has been reported previously for neuronal GABAA channels and their conductance has varied widely (Hamill et al., 1983; Mathers, 1985; Huck & Lux, 1987; Weiss et al., 1988; MacDonald et al., 1989; Birnir et al., 2000). A wide range of GABA-activated channel conductances has also been reported. (Hamill et al., 1983; Gray & Johnston, 1985; Smith et al., 1989; MacDonald et al., 1989; Mathers, 1991; Sivilotti & Nistri, 1991; Curmi et al., 1993; Birnir et al., 1994). Why ligand-gated channels should open spontaneously is not clear. There must always be equilibrium between open and closed conformations and binding of ligand presumably makes the open state more favoured. It is not inconceivable that in some GABAA receptors the equilibrium may be shifted towards the open state in the absence of ligand and this would give rise to spontaneous openings.

It is perhaps more surprising that bicuculline should decrease the conductance of channels. Bicuculline is thought to depress GABAA currents by competitively inhibiting GABA binding to GABAA receptors (MacDonald & Olsen, 1994; Rabow et al., 1996). The depressant effect of bicuculline on the spontaneous currents cannot have been due to this mechanism since no GABA was present. The observation is in accord with studies of GABAA receptors in which bicuculline inhibited currents activated by pentobarbital or steroids (Barker et al., 1987; Ueno et al., 1997), neither of which activates receptors by binding to the GABA binding site. These observations suggested that bicuculline must have a depressant effect on GABAA receptors apart from competing with GABA or other agonists at the GABA binding site. It is likely, therefore, that bicuculline has an allosteric mechanism of inhibition, in addition to the competitive mechanism observed in the presence of GABA, as previously proposed by Ueno et al. (1997) based on whole-cell experiments.

In the outside-out patches from cultured neurons, full inhibition by bicuculline took several minutes whereas in cell-attached patches on neurons in hippocampal slices, the same concentration of bicuculline (100 μM) inhibited channel activity within a minute. Why this difference exists is not clear. The effectiveness of the allosteric mechanism of inhibition by bicuculline may vary and be related to the subunit composition of the receptors. The GABAA isoforms expressed in the slices and the cultured neurons may not be the same. In this context it is also worth noting that when recordings are made in the cell-attached configuration from the cultured neurons used in this study, spontaneous GABAA channel openings are rare (Curmi et al., 1993), suggesting that the open probability of the receptors is increased in the excised patches. It is hardly surprising if there are some differences in channel properties in cell-attached and outside-out patches considering how the outside-out patch is formed. Receptor complexes need to be dragged into the patch and they are no longer in contact with the normal intracellular milieu and cellular architecture. If for example the phosphorylation state of the receptors differs, the open probability of channels may not be the same (MacDonald & Olsen, 1994; Rabow et al., 1996).

An unusual and previously unreported feature of the bicuculline inhibition was the gradual decrease in channel conductance. In the cell-attached patch, it could be argued that the reduction in amplitude of currents when bicuculline was injected into the pipette might have been due to a change in the driving force on the ions flowing through the channel, perhaps because of a change in membrane potential. However, there was no change in the null potential (E0) which remained at 0 mV. Channel conductance is given by the amplitude of the single channel current, i, divided by Vp−E0. As Vp was fixed and E0 did not change, channel conductance must have decreased. Furthermore, in the outside-out patches, a similar gradual reduction in conductance was recorded. It is not inconceivable that bicuculline, when it binds to the GABA-binding site, could alter the conformation of the channel. A part of the bicuculline molecule can be used to obtain an isosteric match with GABA and may account for the competitive mechanism of inhibition but the whole bicuculline structure is much larger than the size of the GABA molecule (Steward et al., 1975). It may be that the spread of charges or other structural features associated with bicuculline's larger size affect the open conformation of the receptor and thereby influence channel characteristics. It is well recognized that GABAA receptors have multiple subconductance states and the bicuculline may make the lower conductance states more favoured. The presence of the various subconductance states clearly cannot be due to the binding of an agonist since they can be observed in the absence of a ligand but GABA may stabilize some higher conductance states similar to what has been observed for cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (Ruiz & Karpen, 1997). The results in Figure 4 are consistent with this idea. Following exposure of the patch to 100 μM GABA, the low conductance channels gradually disappear and higher conductance channels appear (see Figure 4Ad–f,D).

It has been shown previously that barbiturates and benzodiazepines increase the open probability of GABAA channels (Rogers et al., 1994; MacDonald & Olsen, 1994; Rabow et al., 1996; Birnir et al., 2000) and diazepam also increases their conductance (Eghbali et al., 1997; Guyon et al., 1999). The concentration of pentobarbital determined the average conductance of the spontaneously active channels in this study. The increase in the single-channel conductance of the spontaneous channels in the outside-out patches caused by diazepam was much greater than for spontaneous channels in cell-attached patches from hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons (Birnir et al., 2000). As with GABA-activated channels (Eghbali et al., 1997), the conductance increase caused by diazepam was less for the higher conductance spontaneous channels than for the lower conductance channels. Variability in GABA-activated conductance has been associated with different subunit compositions of reconstituted receptors (MacDonald & Olsen, 1994; Rabow et al., 1996). This raises the question whether the high and the low conducting spontaneous channels are due to identical receptors or not. Is their subunit composition different or is the molecular identity the same in both cases but the channel in a different conducting state? The gradual decrease of the channel conductance caused by bicuculline indicates that the latter explanation is more likely.

Abbreviations

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis (b-aminoethylether)tetraacetic acid

- DMSO

dimethylsulphoxide

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- HEPES

N-[2-Hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N′-[2-ethanesulphonic acid]

- TES

N-tris(hydroxymethyl) methyl-2-amino ethane sulphonic acid

References

- BARKER J.L., HARRISON N.L., LANGE G.D., OWEN D.G. Potentiation of γ-aminobutyric-acid-activated chloride conductance by a steroid anaesthetic in cultured rat spinal neurons. J. Physiol. 1987;386:485–501. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNARD E.A., SKOLNICK P., OLSEN R.W., MOHLER H., SIEGHART W., BIGGIO G., BRAESTRUP C., BATESON A.N., LANGER S.Z. International Union of Pharmacology. XV. Subtypes of γ-aminobutyric acidA receptors: classification on the basis of subunit structure and receptor function. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:291–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIRNIR B., EGHBALI M., EVERITT A.B., COX G.B., GAGE P.W. Non-synaptic GABA-gated receptors exhibit great plasticity in channel conductance. Biophys. J. 1999;76:A338. [Google Scholar]

- BIRNIR B., EVERITT A.B., GAGE P.W. Characteristics of GABAA channels in rat dentate gyrus. J. Membrane. Biol. 1994;142:93–102. doi: 10.1007/BF00233386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIRNIR B., EVERITT A.B., LIM M.S.F., GAGE P.W. Spontaneously opening GABAA channels in CA1 pyramidal neurones of rat hippocampus. J. Membrane Biol. 2000;174:21–29. doi: 10.1007/s002320001028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIRNIR B., TIERNEY M.L., PILLAI N.P., COX G.B., GAGE P.W. Rapid desensitization of α1β1 GABAA receptors expressed in Sf9 cells under optimized conditions. J. Membrane Biol. 1995;148:193–202. doi: 10.1007/BF00207275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINGRIDGE G.L., GAGE P.W., ROBERTSON B. Inhibitory post-synaptic currents in rat hippocampal CA1 neurones. J. Physiol. 1984;356:551–564. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURMI J.P., PREMKUMAR L.S., BIRNIR B., GAGE P.W. The influence of membrane potential on chloride channels activated by GABA in rat cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Membrane Biol. 1993;136:273–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00233666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EGHBALI M., CURMI J.P., BIRNIR B., GAGE P.W. Hippocampal GABAA channel conductance increased by diazepam. Nature. 1997;388:71–75. doi: 10.1038/40404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FATIME-SHAD K., BARRY P.H. A patch-clamp study of GABA- and strychnine-sensitive glycine-activated currents in post-natal tissue-cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 1992;250:99–105. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAGE P.W., BIRNIR B., EVERITT A.B. Spontaneously opening tonic GABAA channels in rat CA1 hippocampal neurons. Proc. Austr. Physiol. Pharmacol. Soc. 1998;29:56P. [Google Scholar]

- GRAY R., JOHNSTON D. Rectification of single GABA-gated chloride channels in adult hippocampal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1985;54:134–142. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUYON A., LAURENT S., PAUPARDIN-TRITSCH D., ROSSIER J., EUGENE D. Incremental conductance levels of GABAA receptors in dopaminergic neurons of the rat substantia nigra pars compacta. J. Physiol. 1999;516:719–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0719u.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILL O.P., BORMANN J., SAKMANN B. Activation of multiple-conductance state chloride channels in spinal neurons by glycine and GABA. Nature. 1983;305:305–308. doi: 10.1038/305805a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILL O.P., MARTY A., NEHER E., SAKMANN B., SIGWORTH F.J. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUCK S., LUX H.D. Patch-clamp study of ion channels activated by GABAA and glycine in cultured cerebellar neurons of the mouse. Neurosci. Lett. 1987;79:103–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90679-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACDONALD R.L., OLSEN R.W. GABAA receptor channels. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1994;17:569–602. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACDONALD R.L., ROGERS C.J., TWYMAN R.E. Kinetic properties of the GABAA receptor main conductance state of mouse spinal cord neurons in culture. J. Physiol. 1989;410:479–499. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATHERS D.A. Spontaneous and GABA-induced single channel currents in cultured murine spinal cord neurons. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1985;63:1228–1233. doi: 10.1139/y85-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATHERS D.A. Activation and inactivation of the GABAA receptor: insights from comparison of native and recombinant subunit assemblies. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1991;69:1057–1063. doi: 10.1139/y91-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RABOW L.E., RUSSEK S.J.A., FARB D.F. From ion currents to genomic analysis: Recent advances in GABAA receptor research. Synapse. 1996;21:189–274. doi: 10.1002/syn.890210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROGERS C.J., TWYMAN R.E., MACDONALD R.L. Benzodiazepine and β-carboline regulation of single GABAA receptor channels of mouse spinal neurones in culture. J. Physiol. 1994;475:69–82. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUIZ M.L., KARPEN J.W. Single cyclic nucleotide-gated channels locked in different ligand-bound states. Nature. 1997;389:389–392. doi: 10.1038/38744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIVILOTTI L., NISTRI A. GABA receptor mechanisms in the central nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 1991;36:35–92. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(91)90036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH S.M., ZOREC R., MCBURNEY R.N. Conductance states activated by glycine and GABA in rat cultured spinal neurons. J. Membrane Biol. 1989;108:45–52. doi: 10.1007/BF01870424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEWARD E.G., BORTHWICK P.W., CLARKE G.R., WARNER D. Agonism and antagonism of γ-aminobutyric acid. Nature. 1975;256:600–602. doi: 10.1038/256600a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UENO S., BRACAMONTES J., ZORUMSKI C., WEISS D.S., STEINBACH J.H. Bicuculline and gabazine are allosteric inhibitors of channel opening of the GABAA receptor. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:625–634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00625.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNWIN N. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 9 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;229:1101–1125. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEISS D.S., BARNES E.M., HABLITZ J.J. Whole-cell and single-channel recordings of GABA-gated currents in cultured chick cerebral neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1988;59:495–513. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.2.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]