Abstract

The role of group III metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) in ischaemic neurodegeneration is still unsettled. In order to examine a possible modulatory effect of these receptors on ischaemia-induced damage we tested the novel selective agonist (R,S)-4-phosphonophenylglycine [(R,S)-PPG] after an hypoxic/hypoglycaemic insult in rat hippocampal slices. The recovery of population spike amplitudes in the CA1-region was used as parameter for neuronal viability. (R,S)-PPG significantly improved the recovery of synaptic transmission in the CA1-region even when applied only during the recovery period. The results imply that presynaptic glutamate release after an insult contributes to neurodegeneration. Since agonists of group III mGluR reduce neurotransmitter release – probably via presynaptic autoreceptors – we interpret the results obtained in our in vitro model of hypoxia/hypoglycaemia as support of the hypothesis that group III mGluR agonists might be beneficial drugs against diseases where excitotoxicity is one of the dominant pathological mechanisms.

Keywords: mGluR; hypoxia/hypoglycaemia; hippocampus; neuroprotection; (R,S)-PPG

Introduction

Activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) during ischaemia results in detrimental sodium and calcium overload and iGluR antagonists have been shown to protect neurones from degeneration. The mGluRs, which are coupled to distinct effector systems via GTP-binding proteins (G-proteins) are also activated during hypoxia or ischaemia, but their role in ischaemic neurodegeneration is still a matter of debate. Based on their amino acid homology, pharmacology and transduction mechanisms, the eight mGluRs known to date can be divided into three main groups. Group I consists of mGluR1 and mGluR5, which activate phospholipase C. Group II (mGluRs 2 and 3) and Group III (mGluRs 4, 6, 7 and 8) mGluRs are both negatively coupled to adenylyl cyclase and inhibit cyclic AMP formation, but differ in their agonist preference (Pin & Duvoisin, 1995). The activation of group I and group II mGluRs has been reported in many different studies to either contribute to, or protect against, cell death (e.g. Copani et al., 1995; Bond et al., 1998; Henrich-Noack et al., 1998; Schröder et al., 1999), whereas reports on group III effects are limited. Their activation modulates synaptic transmission effectively either by presynaptic inhibition of transmitter release or by postsynaptic changes in excitability (Abdul-Ghani et al., 1997). Group III mGluRs are widely distributed in the rat brain and immunocytochemical studies have demonstrated that mGluR4 and 7 are localized presynaptically in the hippocampal formation (Bradley et al., 1996). These receptors appear to act as inhibitory presynaptic autoreceptors and to decrease synaptic transmission probably via a reduction of the Ca2+-dependent release of glutamate. Moreover, group III mGluRs have been shown to mediate inhibition of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and of cation influx through Ca2+-permeable α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors (Martin et al., 1997). These characteristics indicate that agonists at these receptors might have the potency to prevent – at least partially – an excessive glutamate release and the development of neurodegeneration. Interestingly, it has been shown that vulnerable neurones react to an increased extracellular glutamate concentration by an upregulation of mGluR4 mRNA levels. L(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutryic acid (L-AP4) and L-Serine-O-phosphate (L-SOP), so far the most commonly used group III mGluR agonists, exerted antiepileptogenic and anticonvulsant activity in kindled and 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG)-treated animals (Abdul-Ghani et al., 1997) and reduced nitric oxide- and anoxia-induced damage in primary hippocampal neurones (Maiese et al., 1996). At high doses, however, both L-AP4 and L-SOP had proconvulsive effects (Gasparini et al., 1999) which might not be due to group III mGluR stimulation. Recently, (R,S)-PPG (Bigge, 1989) was shown to be a potent and selective mGluR group III agonist in recombinant cell lines expressing the human receptors hmGluR4a, hmGluR6, hmGluR7b and hmGluR8a (Gasparini et al., 1999). In contrast to L-AP4 and L-SOP the structurally distinct (R,S)-PPG did not exhibit any proconvulsive effect even at very high doses, but did improve the outcome after maximal electroshock-induced convulsions in mice (Gasparini et al., 1999). Moreover, (R,S)-PPG protected against NMDA- and quinolinic acid-induced lesions in rats (Gasparini et al., 1999). In previous studies reporting neuroprotective effects of mGluR agonists the drugs were applied predominantly before or during the insult (Opitz et al., 1995; Schröder et al., 1999). Stroke patients, however, can only be treated after ischaemia and thus a therapeutic drug must exert its neuroprotective effect after the insult. In the present study we investigated whether or not the novel group III mGluR agonist (R,S)-PPG influences neuronal damage after a hypoxic/hypoglycaemic insult and thus might be a prototype for new neuroprotective therapeutics.

Methods

Experiments were performed with 7–8 week old male Wistar rats (Institute breeding stock), which were killed by a blow to the neck. After decapitation and dissection of the brain, transverse hippocampal slices (400 μm) were prepared with a self-constructed tissue chopper and placed into an interface type recording chamber. There they were maintained at 34±1°C with a constant Ringer perfusion (1 ml min−1). The Ringer contained (in mM): NaCl 124, KCl 4.9, MgSO4 1.3, CaCl2 2, KH2PO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25.6, D-glucose 10, bubbled to pH 7.4 with carbogen (95% O2/5% CO2). The surface of the slices was exposed to a moist carbogen atmosphere. A population spike (PS) was evoked by stimulation of the Schaffer collateral/commissural fibres by biphasic constant voltage pulses (0.1 ms per half wave) via a stainless steel electrode and recorded with a glass microelectrode (1–4 MΩ) in the stratum pyramidale of the CA1 region. Test stimuli were adjusted to elicit a PS of about 60% of maximum amplitude. The PS amplitude was evaluated by calculating the voltage difference between the negative peak and the positive one preceding it. The PS amplitude depends, over a wide range, on the number of discharging neurones and may therefore serve as a measure of functional integrity of this cell population.

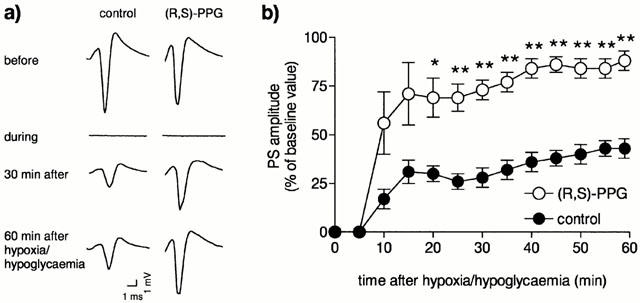

Hypoxia/hypoglycaemia was induced by changing the carbogen atmosphere in the chamber to a gas mixture containing 95% N2/5% CO2 in the presence of a Ringer solution in which glucose was replaced by mannitol. Re-establishment of oxygen and glucose supply started 4 min after the onset of the insult. The recovery of the PS amplitude was monitored for at least 1 h (Figure 1, the responses of four test stimuli with a frequency of 0.2 Hz were averaged for each time point). (R,S)-PPG (Tocris Neuramin, Bristol, U.K.) was bath applied from the time of re-establishment of oxygen and glucose supply until the end of the experiment.

Figure 1.

Effect of the novel selective group III agonist (R,S)-4-phosphonophenylglycine ((R,S)-PPG, 30 μM) on the recovery of PS in area CA1 of rat hippocampal slices after a 4 min hypoxia/hypoglycaemia. (a) The representative traces show evoked PS recorded immediately before, during and at different time points after hypoxia/hypoglycaemia. In the second column (R,S)-PPG was present from the time of re-establishment of oxygen and glucose supply for throughout the recovery period. (b) Time course of PS recovery in untreated control slices (n=6) and in slices treated with 30 μM (R,S)-PPG (n=6). Asterisks indicate significant differences from control slices, calculated with Mann-Whitney's U-test (*P<0.05; **P<0.01). Data are expressed as the mean±standard error.

Results

Interruption of oxygen and glucose supply resulted in a complete loss of the evoked electrophysiological response in the hippocampal slices 1–2 min after the onset of hypoxia/hypoglycaemia. After a 4 min hypoxia/hypoglycaemia, the PS recorded from otherwise untreated CA1 pyramidal cells recovered within 1 h only to about 40% of its baseline amplitude (Figure 1, control). In the presence of 30 μM (R,S)-PPG population spike responses recovered to approximately 88% (Figure 1), significantly different from the recovery in control slices (P⩽0.05, Mann-Whitney U-Test). (R,S)-PPG did not affect the baseline responses measured in a separate series of experiments (104±3.5% of baseline amplitude after 20 min, n=6).

Discussion

In this study we demonstrate for the first time that the activation of group III mGluRs after a hypoxia/hypoglycaemia can still rescue neurones in brain tissue from adult animals. It should be kept in mind, though, that acutely isolated slices from adult rats have a limited life-time and that the short-term protection seen in this study does not necessarily reflect long-term survival. On the other hand, Small et al. (1996) clearly demonstrated that PS recovery 4 h after the insult perfectly matches the morphological damage, indicating that the PS amplitude is a valid parameter for neuronal damage. The attenuation of the functional disturbance following oxygen-glucose deprivation by (R,S)-PPG extends recent findings showing that group I and II mGluR ligands can protect neurones after an ischaemic insult (Bond et al., 1998; Henrich-Noack et al., 1998) and that L-AP4 reduces anoxia-induced damage in primary hippocampal neurones (Maiese et al., 1996). Since agonists of group III mGluR reduce neurotransmitter release – probably via presynaptic autoreceptors (Lombardi et al., 1993; Wigmore & Lacey, 1998) – we interpret our results as support of the hypothesis that (R,S)-PPG might be a beneficial drug against diseases where excitotoxicity is one of the dominant pathological mechanisms. In line with the interpretation that (R,S)-PPG protects mainly against excitotoxic damage the drug was shown to reduce NMDA- and quinolinic acid-induced striatal lesions in vivo (Gasparini et al., 1999) and the classical group III mGluR agonists, L-AP4 and L-SOP, protected rat cerebellar granule cells and cultured cortical and cerebellar neurones against toxic insults, such as prolonged β-amyloid peptide exposure, transient iGluR activation, or mechanical damage (Graham & Burgoyne, 1994; Copani et al., 1995; Faden et al., 1997; Bruno et al., 1999; Gasparini et al., 1999). Part of the (R,S)-PPG-induced protection, which we observed as an improved recovery of synaptic transmission, may therefore result from the inhibition of the vicious circle: dying cells release glutamate, glutamate induces cell death (Gasparini et al., 1999).

Our data indicate that a number of neurones get their final death-blow during the early recovery period, when the low membrane potential renders them hyperexcitable. This explains why NMDA-antagonists, which basically inhibit excitotoxic damage, have been found to be neuroprotective after an insult. It is conceivable that there is synaptic glutamate release from these neurons as long as they are alive which contributes to postischaemic excitotoxicity and might be reduced by (R,S)-PPG-mediated activation of autoreceptors. It is still an open question, however, whether presynaptic autoreceptors can act directly, indirectly or not at all on postischaemic glutamate release.

In addition to the regulation of presynaptic glutamate release, the inhibition of NMDA receptors by postsynaptic group III mGluRs via a protein phosphorylation cascade (Martin et al., 1997) may also be involved in the neuroprotective effect of (R,S)-PPG. In our in vitro model of hypoxia/hypoglycaemia we found a pronounced neuroprotective effect with (R,S)-PPG, with similar efficacy as manifested by ligands of group I mGluRs and NMDA-receptor antagonists, which have been shown to be very potent drugs to improve electrophysiological responses after hypoxia (Opitz et al., 1995; Schröder et al., 1999). The observation that glutamate release inhibitors have also been shown to protect the brain against ischaemia (Meldrum et al., 1992) supports the hypothesis that several glutamate receptors should be involved in excitotoxic neurodegeneration. It should be kept in mind, however, that neurodegeneration due to oxygen-glucose deprivation is a multifactorial process, which does not only involve excitotoxicity, but also many other mechanisms including free radical formation, breakdown of ion gradients and energy supply, inflammation and protease activation. Thus, the improvement of neuronal function seen in our experimental setting might not be exclusively due to the antiexcitotoxic potency of (R,S)-PPG. It is likely, that (R,S)-PPG simultaneously also affects other mechanisms by diminishing intracellular cyclic AMP levels. Since (R,S)-PPG, L-AP 4 and L-SOP seem to bind to a glutamate transporter (Urwyler et al., 1996) it is conceivable that direct inhibition of this transporter might also contribute to the protective effects of these compounds, because unfavourable ion gradients and a low membrane potential might promote glutamate release via this transporter even early during reperfusion.

The concentration of (R,S)-PPG applied in our experiments (30 μM) might mediate neuroprotection via activation of mGluR4 and/or mGluR8, but only partially by the recruitment of mGluR7, due to the lower potency of the drug on this receptor subtype (EC50 values: 5.2±0.7 μM, 185±42 μM and 0.2±0.1 μM on hmGluR4a, hmGluR7b and hmGluR8a, respectively (Gasparini et al., 1999)). Since mGluR7 is widely distributed in the brain, development of a group III mGluR agonist with higher potency on the mGluR7 subtype might lead to a more pronounced influence even on ischaemic pathophysiology.

In summary, our in vitro results support the notion that group III mGluR agonists might be a valuable class of drugs against early glutamate-mediated cell damage. However, ischaemia experiments in vivo are necessary to substantiate our hypothesis, that further development of group III mGluR agonists could open a novel strategy to interfere with neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mrs Kathrin Böhm for expert technical assistance and Dr Tariq Ahmed for critical reading of the manuscript. This research was supported by a grant of Saxony-Anhalt (LSA 2508).

Abbreviations

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid

- GluRs

ionotropic glutamate receptors

- L-AP4

L(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutryic acid

- L-SOP

L-Serine-O-phosphate

- mGluRs

metabotropic glutamate receptors

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- (R,S)-PPG

(R,S)-4-phosphonophenylglycine

References

- ABDUL-GHANI A., ATTWELL P.J.E., SING KENT N., BRADFORD H.F., CROUCHER M.J., JANE D.E. Anti-epileptogenic and anticonvulsant activity of L-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate, a presynaptic glutamate receptor agonist. Brain Res. 1997;755:202–212. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIGGE C.F., DRUMMOND J.T., JOHNSON G., MALONE T., PROBERT A.W., JR, MARCOUX F.W., COUGHENOUR L.L., BRABES L.J. Exploration of phenyl-spaced 2-amino-(5-9)-phosphonoalkanoic acids as competitive N-methyl-D-aspartatic acid antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1989;32:1580–1590. doi: 10.1021/jm00127a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOND A., O'NEILL M.J., HICKS C.A., MONN J.A., LODGE D. Neuroprotective effects of a systemically active group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist LY354740 in a gerbil model of global ischaemia. NeuroReport. 1998;9:1191–1193. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199804200-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADLEY S.R., LEVEY A.I., HERSCH S.M., CONN P.J. Immunocytochemical localization of group III metabotropic glutamate receptors in the hippocampus with subtype specific antibodies. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:2044–2056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02044.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRUNO V., BATTAGLIA G., KINGSTON A., O'NEILL M.J., CATANIA M.V., DI GREZIA R., NICOLETTI F. Neuroprotective activity of the potent and selective mGlu1a metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist, (+)-2-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine ( LY367385): comparison with LY357366, a broader spectrum antagonist with equal affinity for mGlu1a and mGlu5 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:199–207. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COPANI A., BRUNO V., BATTAGLIA G., LEANZA G., PELLITTERI R., RUSSO A., STANZANI S., NICOLETTI F. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors protects cultured neurones against apoptosis induced by beta-amyloid peptide. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;47:890–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FADEN A.I., IVANOVA S.A., YAKOVLEV A.G., MUKHIN A.G. Neuroprotective effects of group III mGluR in traumatic neuronal injury. J. Neurotrauma. 1997;14:885–895. doi: 10.1089/neu.1997.14.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GASPARINI F., BRUNO V., BATTAGLIA G., LUKIC S., LEONHARDT T., INDERBITZIN W., LAURIE D., SOMMER B., VARNEY M.A., HESS S.D., JOHNSON E.C., KUHN R., URWYLER S., SAUER D., PORTRET C., SCHMUTZ M., NICOLETTI F., FLOR P.J. (R,S)-4-Phosphonophenylglycine, a potent and selective group III metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist, is anticonvulsive and neuroprotective in vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;290:1678–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAHAM M.E., BURGOYNE R.D. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors by L-AP4 stimulates survival of rat cerebellar granule cells in culture. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;288:115–123. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENRICH-NOACK P., HATTON C.D., REYMANN K.G. The mGlu receptor ligand (S)-4C3HPG protects neurones after global ischaemia in gerbils. Neuroreport. 1998;9:985–988. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199804200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOMBARDI G., ALESIANI M., LEONARDI P., CHERIZI G., PELLICCIARI R., MORONI F. Pharmacological characterization of the metabotropic glutamate receptor inhibiting the D-[(3)H]-aspartate output in rat striatum. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:1407–1412. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAIESE K., SWIRIDUK M., TENBROEKE M. Cellular mechanisms of protection by metabotropic glutamate receptors during anoxia and nitric oxide toxicity. J. Neurochem. 1996;66:2419–2428. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66062419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN G., NIE Z., SIGGINS G.R. Metabotropic glutamate receptors regulate N-methyl-D-aspartate-mediated synaptic transmission in nucleus accumbens. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;78:3028–3038. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MELDRUM B.S., SWAN J.H., LEACH M.J., MILLAN M.H., GWINN R., KADOTA K., GRAHAM S.H., CHEN J., SIMON R.P. Reduction of glutamate release and protection against ischaemic brain damage by BW 1003C87. Brain Res. 1992;593:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91254-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OPITZ T., RICHTER P., CARTER A.J., KOZIKOWSKI A.P., SHINOZAKI H., REYMANN K.G. Metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes differentially influence neuronal recovery from in vitro hypoxia/hypoglycaemia in rat hippocampal slices. Neurosci. 1995;68:989–1001. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00195-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIN J.P., DUVOISIN R. The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and function. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRÖDER U.H., OPITZ T., JÄGER T., SABELHAUS C.F., BREDER J., REYMANN K.G. Protective effect of group I metabotropic glutamate receptor activation against hypoxic/hypoglycaemic injury in rat hippocampal slices: timing and involvement of protein kinase C. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMALL D.L., MONETTE R., CHAKRAVARTHY B., DURKIN J., BARBE G., MEALING G., MORLEY P., BUCHAN A.M. Mechanisms of 1S,3R-ACPD-induced neuroprotection in rat hippocampal slices subjected to oxygen and glucose deprivation. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1037–1048. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- URWYLER S., LAURIE D., LOWE D.A., MEIER C.L., MULLER W. Biphenyl-derivatives of 2-amino-7-phosphonoheptanoic acid, a novel class of potent competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist-I. Pharmacological characterization in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:643–654. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)84636-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIGMORE M.A., LACEY M.G. Metabotropic glutamate receptors depress glutamate-mediated synaptic input to rat midbrain dopamine neurones in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:667–674. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]