Abstract

The role of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-1 and ERK-2 in controlling histamine-induced tone in bovine trachealis was investigated. PD 098059, an inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MKK)-1, had no effect on the histamine concentration-response relationship that described contraction. However, in the presence of EGTA, PD 098059 produced a parallel 5 fold rightwards shift of the histamine concentration-response curve without reducing the maximum response. The β2-adrenoceptor agonist, procaterol, also displaced the histamine-concentration response curve to the right but the effect was much greater than that evoked by PD 098059, non-competitive and seen in the absence and presence of EGTA.

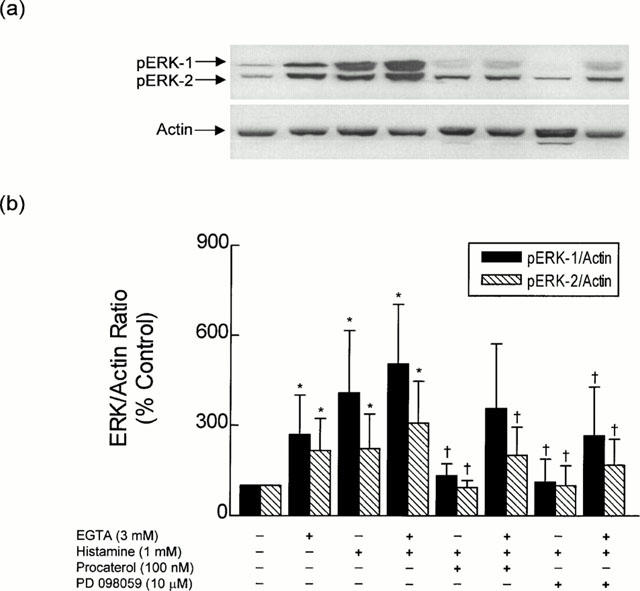

A low basal level of pERK-1 and pERK-2 was always detected in untreated trachealis, which was significantly higher in EGTA-treated tissues and inhibited by PD 098059 and procaterol. Histamine markedly enhanced the phosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2 by a mechanism that was also enhanced by EGTA and significantly attenuated by procaterol and PD 098059.

Neither cholera toxin nor Sp-8-Br-cAMPS mimicked the ability of procaterol to dephosphorylate ERK. Similarly, neither pertussis toxin (PTX) nor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, an inhibitor of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), affected basal pERK levels or antagonized the inhibitory effect of procaterol.

These data implicate the MKK-1/ERK signalling cascade in Ca2+-independent, histamine-induced contraction of bovine trachealis. In addition, the ability of procaterol to dephosphorylate ERK in an Rp-8-Br-cAMPS- and PTX-insensitive manner suggests that this may contribute to the anti-spasmogenic activity of β2-adrenoceptor agonists by activating a novel PKA-independent pathway.

Keywords: Airways smooth muscle, procaterol, PD 098059, mitogen-activated protein kinase, histamine-induced contraction

Introduction

Muscle contraction is the result of the interdigitation of two protein filaments, actin and myosin, which results in the formation of stress-bearing cross-bridges. Classically, the actin-myosin interaction in smooth muscle is regulated by protein phosphorylation catalyzed by a Ca2+- and calmodulin-requiring enzyme called myosin light chain kinase (MLCK). In resting smooth muscle cells, the cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]c is low and MLCK is inactive. Activation of MLCK occurs only when the [Ca2+]c increases significantly to a level sufficient to bind calmodulin, which permits the formation of a Ca2+:calmodulin:MLCK complex. In this form, MLCK phosphorylates myosin on the 20 kDa light chains (LC20) enabling actin to activate myosin ATPase (intrinsic to the myosin molecule), which hydrolyses the ATP required for the formation of stress-bearing cross-bridges between actin and myosin (see Arner & Pfitzer, 1999 for review).

Although LC20 phosphorylation undoubtedly accounts for Ca2+-dependent force generation in airways and other smooth muscles, a different mechanism(s), as well as or in addition to LC20 phosphorylation, may be responsible for the force generated under conditions where [Ca2+]c has declined to near resting levels (see Webb et al., 2000). One school of thought implicates protein kinase C (PKC) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-1 and ERK-2. Indeed, Ca2+-independent, α-adrenoceptor-mediated contraction of ferret aortas is associated with a sustained translocation of the ε isoform of PKC to the plasma membrane (Khalil & Morgan, 1992). This effect is accompanied by a transient re-distribution of ERK-1 and ERK-2 from the cytosol to the cell membrane followed by a second re-localization towards the vicinity of the contractile proteins prior to agonist-induced force development (Khalil & Morgan, 1992).

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1 and ERK-2 are proline-directed, serine/threonine protein kinases that are implicated in diverse functional responses (Davis, 1993) in particular cell growth and differentiation (see Page & Hershenson, 2000). However, ERK-1 and ERK-2 are also activated in non-proliferating differentiated cells by an upstream kinase termed mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MKK)-1 (also called MEK-1). With respect to airways smooth muscle, ERK-1 and ERK-2 are phosphorylated by contractile agonists such as carbachol, 5-HT and endothelin and this has been linked to force development (Gerthoffer et al., 1997; Kelleher et al., 1995; Vichi et al., 1999; Watts, 1996; Yamboliev et al., 2000). Of the many putative substrates recognized by ERK-1 and ERK-2, the actin-binding protein, caldesmon, has attracted much attention with respect to the regulation of smooth muscle contraction for several reasons. First, caldesmon is regulated by reversible phosphorylation and the unphosphorylated form inhibits the ability of actin to activate myosin ATPase without affecting LC20 phosphorylation (Clark et al., 1986; Ngai & Walsh, 1984). Second, purified caldesmon is phosphorylated by ERK-2 in a cell-free system and addition of ERK-2 to Triton X-100-permeabilized canine airways smooth muscle fibres potentiates Ca2+-induced tension development (Gerthoffer et al., 1997). Third, caldesmon is phosphorylated in intact airways, gastrointestinal and vascular smooth muscle during agonist-induced contraction (Dessy et al., 1998; Gerthoffer et al., 1996; 1997; Gerthoffer & Pohl, 1994) at proline-directed serines (i.e. S789PTKV and S759PAPK), which is characteristic of a mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase consensus sequence (Adam & Hathaway, 1993). Another actin-binding protein, calponin, has also been implicated in Ca2+-independent force development (Winder et al., 1998), which may be regulated by ERK independently of phosphorylation (Menice et al., 1997).

Further evidence that the MAP kinase signalling cascade regulates smooth muscle contractility derives from pharmacological studies in vascular smooth muscle. Thus, 5-HT-evoked contraction of the rat aorta, mesenteric and tail artery (Watts, 1996) and phenylephrine-induced, Ca2+-independent contraction of ferret aortas (Dessy et al., 1998) were significantly suppressed by PD 098059, a selective inhibitor of MKK-1. However, PD 098059 had no effect on histamine- or leukotriene D4-induced tone of guinea-pig trachealis (Tsang et al., 1998) or on histamine-evoked contraction of porcine carotid artery (Gorenne et al., 1998) suggesting that the involvement of ERK in tension generation may be tissue, agonist or species dependent.

In light of the apparent controversy surrounding the effect of PD 098059 on agonist-induced tension generation in smooth muscle, we have performed a pharmacological study examining the role of the MKK-1/ERK signalling pathway in regulating histamine-induced contraction of bovine trachealis. As β2-adrenoceptor agonists affect the phosphorylation of a variety of substrates in airways smooth muscle, many of which impact on the contractile proteins to effect a spasmolytic or anti-spasmogenic influence (see Giembycz & Raeburn, 1991), we have also determined if ERK activity is affected by procaterol, a potent and selective β2-adrenoceptor agonist.

Methods

Preparation of bovine tracheal smooth muscle

Fresh tracheae were obtained from a local abattoir and transported to the laboratory on ice. The cervical trachealis was isolated, stripped free of epithelium and all other extrinsic connective tissue, and used immediately.

Tension measurements

Strips (2×2×10 mm) of trachealis were mounted vertically, under an initial force of 20 mN in 5 ml tissue baths containing oxygenating (95% O2; 5% CO2) Krebs-Henseleit (KH) solution of the following composition (in mM): NaCl 118; KCl 5.9; MgSO4 1.2; CaCl2 2.5; NaH2PO4 1.2; NaHCO3 25.5 and glucose 5.6. Each strip was left to equilibrate for ∼60 min after which ACh (100 μM) was added. When contractions had reached a plateau, the tissues were washed extensively until resting tone was re-established. After a further period (30 min) of equilibration, procaterol (100 nM), PD 098059 (10 μM) or an equivalent volume of their respective vehicles were added to the baths and cumulative concentration-response curves were constructed to histamine 20 min later according to the method of Van Rossum (1963). In some experiments, EGTA (3 mM) was added to the tissue baths 15 min before procaterol or PD 098059. One concentration-response curve was generated per tissue. Changes in tension were measured isometrically via Grass FT-03.c force-displacement transducers (Quincy, MA, U.S.A.) and recorded on a Polygraph (Model 7D). The results are expressed as a percentage of the maximum contraction elicited by ACh (100 μM).

Treatment of tissue for cyclic AMP content and MAP kinase measurements

Bovine tracheal smooth muscle strips were incubated free-floating for 60 min in oxygenating KH solution in the absence and presence of EGTA (3 mM; as indicated) at 37°C and then stimulated with histamine, procaterol, Rp-/Sp-8-Br-cAMPS, PD 098059 or SB 203580 as described in the Results section. Tracheal strips were blotted on adsorbant tissue paper and frozen immediately for cyclic AMP estimation and/or Western blotting. In experiments where pertussis toxin (PTX; 500 ng ml−1) or cholera toxin (CTX; 2 μg ml−1) were used, tracheal smooth muscle was incubated overnight in Dulbecco‘s modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, HEPES-modification) supplemented with 10% (v v−1) foetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamate, 100 IU ml−1 penicillin, 100 mg ml−1 streptomycin and 2.5 μg ml−1amphotericin B at 37°C before being exposed to the drugs under investigation.

Measurement of cyclic AMP

The frozen bovine tissue was homogenized in 2 ml of ice-cold 1 M trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and centrifuged at 2500×g to precipitate particulate material. To 500 μl of supernatant 50 μl of 25 mM EDTA was added, vortex-mixed and then 500 μl of 1,1,2-trichloro-trifluoroethane:tri-n-octylamine (1 : 1 v v−1) was added. This mixture was then thoroughly vortex-mixed and centrifuged at 13,000×g for 2 min at room temperature. An aliquot (360 μl) of the upper phase was decanted and neutralized with 40 μl of 120 mM sodium bicarbonate. The neutralized extracts were acetylated by the consecutive addition of triethylamine (20 μl) and acetic anhydride (10 μl), and cyclic AMP mass was measured immediately by RIA. Briefly, to 200 μl of acetylated sample, were added 50 μl of adenosine-3′,5′-monophospho-2-O-succinyl-3-[125I] iodotyrosine methyl ester (approximately 2000–3000 d.p.m.) in 0.2% BSA and 100 μl of anti-cyclic AMP antibody in 0.2% BSA. After vortex-mixing, samples were incubated overnight at 4°C and free and antibody-bound cyclic AMP was separated by charcoal precipitation with ice-cold potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM in 0.2% BSA-pH 7.4) and quantified by γ-counting.

Measurement of the phosphorylation status of ERK-1, ERK-2 and p38 MAP kinase

The activation status of ERK-1, ERK-2 and p38 MAP kinase was assessed by Western immunoblot analysis using antibodies that recognize the dual phosphorylated (activated) form of the enzymes. Frozen bovine tissue was homogenized in lysis buffer (Tris HCl 10 mM, NaCl 150 mM, EDTA 1 mM, pH 7.4), supplemented with phenyl-methyl-sulphonyl-fluoride (PMSF; 500 μM), Na-orthovanadate (2 mM), leupeptin (10 μg ml−1), aprotinin (25 μg ml−1), pepstatin (10 μg ml−1), NaF (1.25 mM) and Na-pyrophosphate (1 mM). Insoluble protein was removed by centrifugation at 12,000×g for 5 min and the supernatants were ultracentrifuged at 33,000 for 1 h to separate membrane and cytosolic fractions. Protein (20 μg cytosolic fraction) was diluted 1 : 4 in Laemelli buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl–pH 6.8, 10% v v−1 glycerol, 1% w v−1 SDS, 1% v v−1 β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% w v−1 bromophenol blue) and boiled for 5 min. Denatured proteins were subsequently separated by SDS–PAGE upon 10% vertical slab gels and transferred to Hybond ECL membranes (Amersham) in blotting buffer supplemented with 20% v v−1 methanol.

The nitrocellulose was incubated for 1 h in TBS-Tween-20® (25 mM Tris-base–pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% v v−1 Tween 20, 10% w v−1 non-fat milk) and incubated 2 h in TBS-Tween 20 containing 3% w v−1 BSA and primary antibodies raised against pERK1/2, pp38 MAP kinase or actin (diluted 1 : 1000). Following 3×10 min washes in TBS-Tween 20, the membranes were incubated for 60 min with a goat anti-rabbit peroxidase-conjugated IgG antibody diluted 1 : 5000 in TBS-Tween 20 supplemented with 1% w v−1 non-fat milk and then washed again (3×10 min). Antibody-labelled proteins were subsequently visualized by ECL. Relevant bands were quantified by laser-scanning densitometry and normalized to a house-keeping protein, actin.

Drugs and analytical reagents

Anti-phospho-ERK-1/2 and anti-p38 MAP kinase, mouse-monoclonal IgG1 anti-actin and peroxidase-conjugated, goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulins were purchased from New England Biolabs U.K. Ltd (Hitchin, Hertfordshire, U.K.), Santa Cruz Biotechnology/Autogen Bioclear (Calne, Wiltshire, U.K.) and Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) respectively. Sp- and Rp-8-Br-cAMPS were from BioLog Life Science (Bremen, Germany), ECL and adenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophospho-2′-O-succinyl 3-[125I]iodotyrosylmethyl ester (∼2000 Cimmol−1) were purchased from Amersham International (Buckinghamshire, U.K.), PD 098059 was obtained from Calbiochem-NovaBiochem U.K. Ltd (Nottingham U.K.) and SB 203580 was a kind gift from SmithKline-Beecham (King of Prussia, U.S.A.). Procaterol, histamine, propranolol, CTX, PTX, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; HEPES-modification), cyclic AMP antibody, proteinase inhibitors and all other reagents were purchased from the Sigma Chemical Company (Poole, Dorset, U.K.).

Stock solutions of drugs were made in methanol (procaterol), DMSO (PD 098059, SB 203580) or distilled water (histamine, propranolol, Rp-8-Br-cAMPs, Sp-8-Br-cAMPs, CTX, PTX) and diluted to the desired concentration in aqueous media.

Data and statistical analyses

Data points, and values in the text and figure legends, represent the mean±s.e.mean of n independent determinations. Data were analysed by Student's t-test for paired data or, where appropriate, ANOVA/Dunnett's multiple comparison test before normalization. The null hypothesis was rejected when P<0.05.

Results

Effect of PD 098059 on histamine-induced contraction

To test the hypothesis that MAP kinase-signalling cascades regulate airways smooth muscle tone, the effect of PD 098059, a selective inhibitor of MKK-1, was evaluated on histamine-induced tension generation and on the dual phosphorylation status of ERK-1 and ERK-2, an unequivocal index of activation.

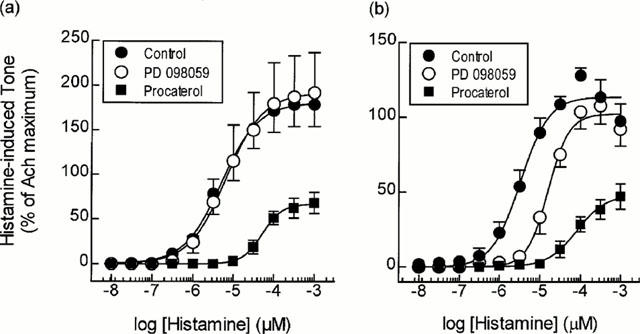

PD 098059 (10 μM; 30 min) exerted no effect on resting tone in bovine tracheal smooth muscle strips or on histamine-induced contractile responses (Figure 1a; Table 1). In contrast, when the KH solution was supplemented with 3 mM EGTA, to chelate extracellular Ca2+, PD 098059 (10 μM; 30 min) still failed to influence basal tone but produced a significant (∼5 fold) rightwards shift of the histamine concentration-response curve without affecting the maximum response (Figure 1b; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of PD 098059 and procaterol on histamine-induced contractile responses. Strips of smooth muscle were equilibrated in KH solution in the absence (a) or presence (b) of EGTA (3 mM) and then pre-treated for 30 min with procaterol (100 nM), PD 098059 (10 μM) or their respective vehicles. Cumulative concentration-response curves were then constructed to histamine and EC50 values and the maximum tension generated relative to ACh (100 μM) were interpolated from curves of best-fit. Data points represent the mean±s.e.mean of 4–6 determinations.

Table 1.

Effect of procaterol and PD 098059 on histamine-induced tension generation in the absence and presence of EGTA

Effect of PD 098059 on the phosphorylation state of ERK-1, ERK-2 and p38 MAP kinase

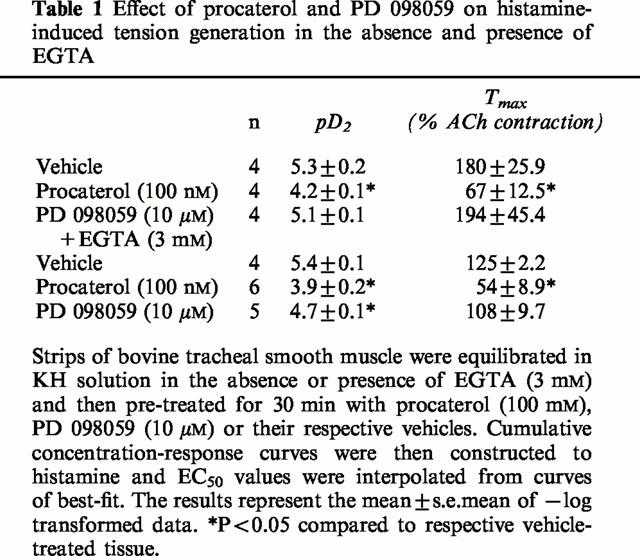

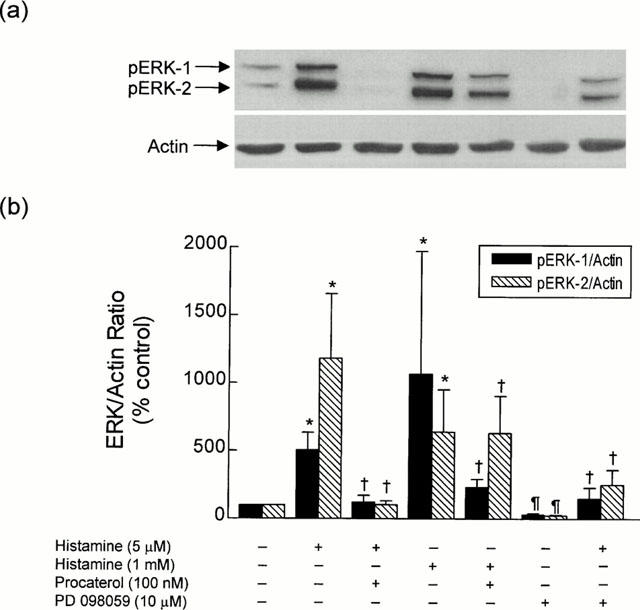

Significant phosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2 was normally detected in quiescent tracheal smooth muscle strips and this ‘resting' activity was inhibited in tissues pre-treated with PD 098059 (10 μM; 30 min; Figure 2). Similarly, immunoreactive pp38 MAP kinase was also routinely found in the same smooth muscle preparations under identical experimental conditions, which was unaffected by PD 098059 (Figure 3). The constitutive expression of pERK-1, pERK-2 and pp38 MAP kinase was not apparently due to mechanical stretch caused during preparation of the trachealis since identical results were obtained with tissue equilibrated in KH solution for up to 13 h (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Histamine-induced phosphorylation of ERK in bovine trachealis: effect of procaterol and PD 098059. Strips of smooth muscle were equilibrated in KH solution and the effect of histamine alone and in tissue pre-treated with procaterol (100 nM) and PD 098059 (10 μM) on the phosphorylation state of ERK-1 and ERK-2 was determined relative to the house-keeping protein actin. (a) and (b) show a representative Western blot and the mean±s.e.mean of 10 independent determinations respectively. *P<0.05, significant increase in ERK phosphorylation relative to control levels. †P<0.05, significant decrease in histamine-induced ERK phosphorylation. ¶P<0.05, significant decrease in ERK phosphorylation relative to control levels.

Figure 3.

Lack of effect of histamine, procaterol and PD 098059 on the phosphorylation state of p38 MAP kinase. Strips of smooth muscle were equilibrated in KH solution and the effect of EGTA and histamine alone and in tissue pre-treated with procaterol (100 nM) and PD 098059 (10 μM), on the phosphorylation state of p38 MAP kinase was determined relative to total p38 MAP kinase protein.

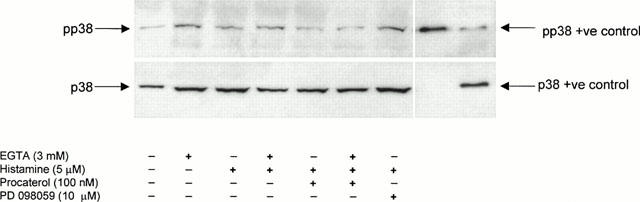

Exposure of bovine trachealis to histamine (5 μM and 1 mM; 30 min) dramatically augmented (5–12 fold) the pERK-1/actin and pERK-2/actin ratio over basal levels by a process that was also inhibited by PD 098059 (10 μM; 30 min; Figure 2b). Significantly, both basal and histamine-induced phosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2 was significantly augmented when EGTA (3 mM) was added to the KH solution (Figure 4). In contrast, neither EGTA nor histamine affected the basal phosphorylation status of p38 MAP kinase (Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Histamine-induced phosphorylation of ERK in bovine trachealis: effect of EGTA, procaterol and PD 098059. Strips of smooth muscle were equilibrated in KH solution and the effect of EGTA (3 mM) and histamine (1 mM) on the phosphorylation status of ERK-1 and ERK-2 was determined in the absence and presence of procaterol (100 nM) and PD 098059 (10 μM), and related to the house-keeping protein actin. (a) and (b) show a representative Western blot and the mean±s.e.mean of six independent determinations respectively. *P<0.05, significant increase in ERK phosphorylation relative to control levels. †P<0.05, significant decrease in histamine-induced ERK phosphorylation.

Effect of procaterol on histamine-induced contraction and on the phosphorylation state of ERK-1 and ERK-2

In contrast to the data obtained with PD 098059, the selective β2-adrenoceptor agonist, procaterol exerted a marked anti-spasmogenic effect on histamine-induced tone irrespective of the presence of EGTA (Figure 1; Table 1). Thus, the histamine concentration-response curves were displaced to the right in a non-parallel fashion and the maximum response was significantly reduced by approximately 60% (Table 1; Figure 1).

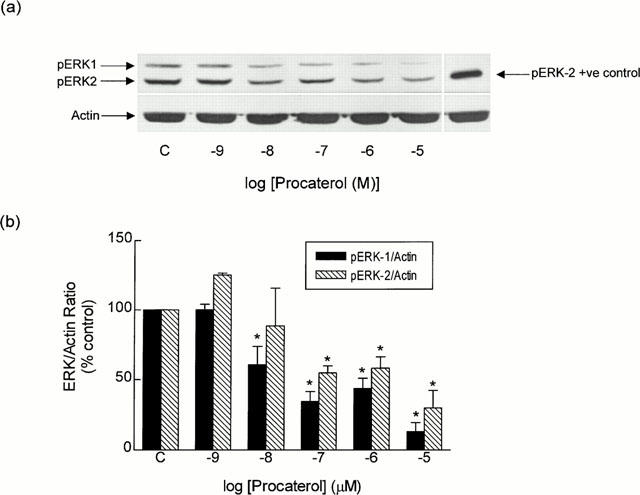

Procaterol (1 nM to 10 μM) also decreased the basal phosphorylation status of ERK-1 and ERK-2 in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 5). At the concentration of procaterol (100 nM; 30 min) used in the functional studies, the pERK-1/actin and pERK-2/actin ratios were reduced by 65 and 45% respectively when compared to untreated, time-matched control tissues (Figure 5b), and this effect was associated with a modest (∼40%), but nevertheless, significant (P<0.05) increase in cyclic AMP mass (from 2.57±0.33 to 3.63±0.41 pmol mg protein−1, n=4). Procaterol (100 nM; 30 min) also dephosphorylated ERK-1 and ERK-2 in tracheal smooth muscle incubated in EGTA-containing KH solution (Figure 4). The phosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2 evoked by histamine (1 mM) similarly was reduced in tissues pre-treated with procaterol (100 nM for 30 min) regardless of the presence of EGTA (Figures 2 and 4).

Figure 5.

Effect of procaterol on the basal phosphorylation state of ERK-1 and ERK-2. Strips of smooth muscle were equilibrated in KH solution and the effect of procaterol (1 nM to 10 μM; 30 min) on pERK-1 and pERK-2 levels was determined relative to the house-keeping protein actin. (a) and (b) show a representative Western blot and the mean±s.e.mean of six independent determinations respectively. *P<0.05, significant inhibition of basal phosphorylation — one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

The ability of procaterol (100 nM; 30 min) to dephosphorylate ERK-1 and ERK-2 was antagonized in tissues pre-treated with propranolol (1 μM; 30 min) indicating that these effects were mediated through β-adrenoceptors (data not shown).

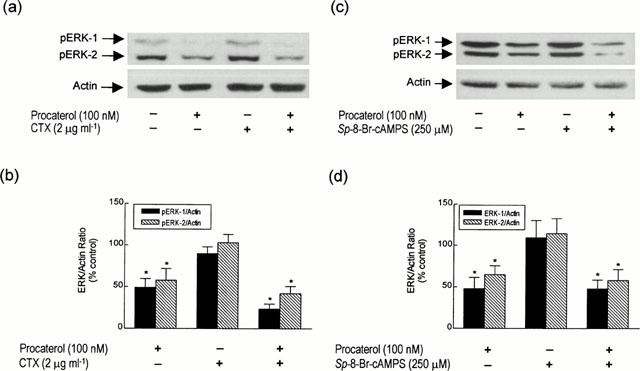

Effect of other cyclic AMP-elevating drugs on ERK-1 and ERK-2 phosphorylation

Pre-incubation of bovine trachealis with cholera toxin (CTX; 2 μg ml−1; 12 h), which irreversibly activates the α-subunit of Gs, failed to affect the basal phosphorylation status of ERK-1 and ERK-2 in bovine trachealis (Figure 6a,b) under conditions where the cyclic AMP content was increased 8 fold over the resting level (from 2.57±0.33 to 21.1± 2.9 pmol mg protein−1 n=4). Sp-8-Br-cAMPS (250 μM; 30 min), a cell permeant and phosphodiesterase-resistant analogue of cyclic AMP, similarly was inactive under identical experimental conditions (Figure 6c,d).

Figure 6.

Effect of CTX (a and b) and Sp-8-Br-cAMPS (c and d) on the phosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2. Strips of bovine trachealis were pre-treated with CTX (2 μg ml−1; 12 h) or Sp-8-Br-cAMPS (250 μM; 30 min) before the addition of procaterol (100 nM; 30 min) or vehicle. (a) and (c), and (b) and (d) show representative Western blots and the mean±s.e.mean of four determinations respectively. *P<0.05, significant inhibition of basal phosphorylation — one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

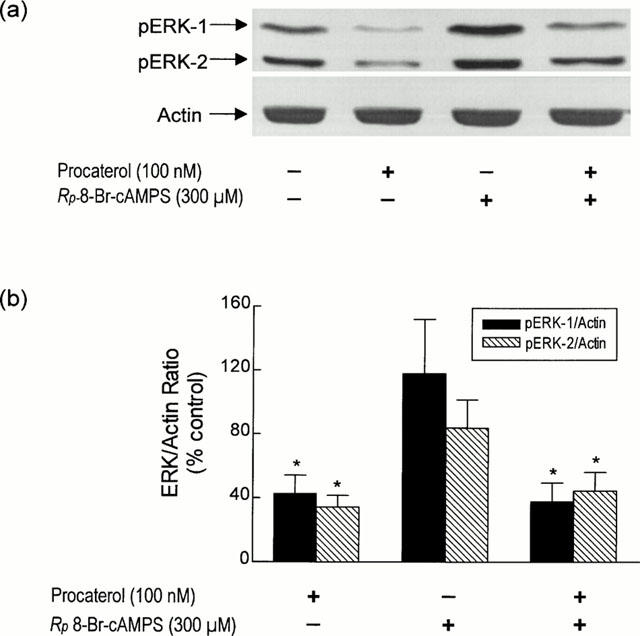

Effect of the PKA inhibitor, Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, on procaterol-induced dephosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2

To determine if dephosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2 by procaterol was mediated by a cyclic AMP-dependent mechanism, bovine tracheal smooth muscle strips were pre-treated with Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (300 μM; 30 min), a membrane-permeant and metabolically-stable inhibitor of PKA, prior to the addition of procaterol (100 nM). As shown in Figure 7, Rp-8-Br-cAMPS did not change the basal pERK-1/actin and pERK-2/actin ratios and similarly failed to inhibit procaterol-induced dephosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2.

Figure 7.

Lack of effect of the PKA antagonist, Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, on procaterol-induced dephosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2. Strips of smooth muscle were equilibrated in KH solution and the ability of Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (300 μM; 30 min) to antagonize procaterol (100 nM)-induced dephosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2 levels was determined relative to the house-keeping protein actin. (a) and (b) show a representative Western blot and the mean±s.e.mean of eight independent determinations respectively. *P<0.05, significant inhibition of basal phosphorylation — one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

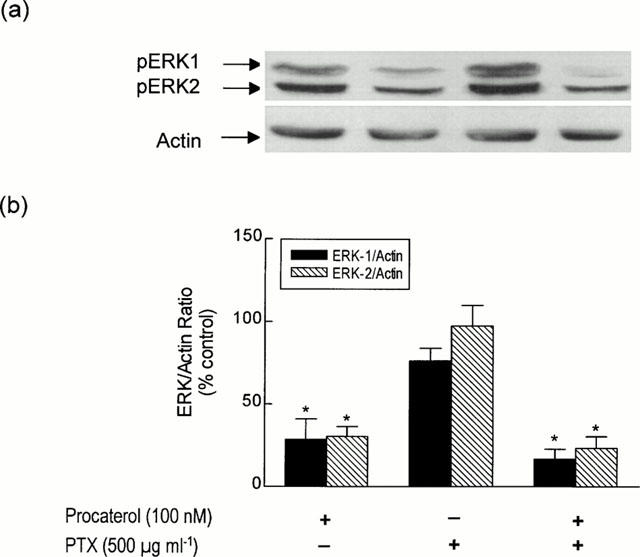

Effect of PTX on the phosphorylation status of ERK-1 and ERK- 2

To investigate whether Gi/Go was involved in procaterol-induced dephosphorylation of pERK-1 and pERK-2, smooth muscle strips were pre-incubated for 12 h in HEPES-modified DMEM in the presence of PTX (500 ng ml−1) before the addition of procaterol (100 nM; 30 min). As shown in Figure 8, no significant change in ERK-phosphorylation was seen in PTX-treated muscle. Similarly, PTX failed to inhibit procaterol-induced dephosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2.

Figure 8.

Effect of PTX on procaterol-induced dephosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2. Strips of smooth muscle were incubated in DMEM and the ability of PTX (500 μg ml−1; 12 h) to modify procaterol-induced dephosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2 was determined relative to the house-keeping protein actin. (a) and (b) show a representative Western blot and the mean±s.e.mean of five independent determinations respectively. *P<0.05, significant inhibition of basal phosphorylation — one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

Discussion

Histamine-induced contraction

In this manuscript we provide pharmacological evidence that activation of the MKK-1/ERK signalling cascade participates in the Ca2+-independent component of histamine-induced force generation in bovine trachealis. Thus, PD 098059, which binds to the inactive form of MKK-1 and prevents its phosphorylation and activation by Raf-1 (Dudley et al., 1995), produced a parallel rightwards shift of the histamine concentration-response curve when the extracellular Ca2+ were chelated by EGTA. These results are entirely consistent with a recent report by Dessy et al. (1998) who found that α1-adrenoceptor-mediated contraction of ferret aortas was antagonized by PD 098059 when the experiment was conducted in the absence, but not the presence, of extracellular Ca2+.

The inability of PD 098059 to antagonize Ca2+-dependent force development in bovine trachealis (present study) and in rat and guinea-pig vascular and airway smooth muscle preparations (Dessy et al., 1998; Gorenne et al., 1998; Tsang et al., 1998) implies that the MKK-1/ERK signalling cascade plays only a minor role in regulating contractility when LC20 phosphorylation is pronounced. This interpretation is consistent with the finding that PD 098059 was a more effective antagonist of contraction at low concentrations of histamine. While the data presented herein do not allow us unequivocally to exclude this pathway from the Ca2+-dependent component of contraction, signalling through MKK-1 clearly participates in force generation/maintenance independently of the phosphorylation of LC20 by MLCK. It is noteworthy that although PD 098059 clearly antagonized histamine-induced contraction of bovine trachealis in EGTA-containing KH solution, this effect was surmountable at higher agonist concentrations indicating that additional PD 098059-insensitive mechanism(s) also contribute to force generation in this species. One process that has been studied in canine (Bremerich et al., 1997; Gerthoffer et al., 1996; Iizuka et al., 1997), human (Yoshii et al., 1999) and rabbit trachealis (Yoshii et al., 1999) is Ca2+ sensitization, whereby contractile agonists, which act through G-protein-coupled receptors, sensitize the contractile machinery to Ca2+ by inhibiting myosin light chain phosphatase (Kitazawa et al., 1991a,1991b; 1999; see Webb et al., 2000).

Western blotting detected significant pERK-1 and pERK-2 in quiescent tracheal smooth muscle strips and this was seen in the absence and presence of EGTA. These data are consistent with results obtained in other tissues including canine trachealis (Gerthoffer et al., 1997; Hedges et al., 2000), guinea-pig bronchi (Tsang et al., 1998), canine pulmonary artery (Yamboliev et al., 2000) and rabbit aortic smooth muscle rings (Larrivee et al., 1998) and suggest that these preparations may release, tonically, mediators that act in an autocrine fashion to activate the MKK-1/ERK signalling pathway. Of significance was the additional finding that PD 098059, at a concentration (10 μM) that antagonized histamine-induced Ca2+-independent contractions of bovine trachealis, abolished basal ERK phosphorylation without inhibiting constitutive pp38 MAP kinase expression. This was seen irrespective of the presence of EGTA and confirms the high specificity of PD 098059 for unphosphorylated MKK-1 (Alessi et al., 1995). It is noteworthy that both ERK isoenzymes were phosphorylated to a significantly greater degree when Ca2+ were chelated by EGTA, which may point to direct or indirect negative regulation of ERK-1 and ERK-2 by a Ca2+-dependent phosphatase.

Exposure of bovine tracheal smooth muscle to histamine significantly increased the phosphorylation of both ERK isoenzymes in a PD 098059-sensitive manner, consistent with a causal role of the MKK-1/ERK pathway in Ca2+-independent contraction. These results confirm previous studies where agonist exposure of canine trachealis (Gerthoffer et al., 1997), ferret aortas (Dessy et al., 1998) and bovine tracheal myocytes (Kelleher et al., 1995; Hershenson et al., 1995) is associated with ERK phosphorylation, which follows a time-course that correlates with smooth muscle contraction (Dessy et al., 1998; Katoch et al., 1995; Gerthoffer et al., 1997). However, our data conflict with a study by Hershenson et al. (1995) who reported that histamine had no effect on basal ERK activity and, in fact, opposed the activation of ERK evoked by 5-HT in bovine cultured tracheal myocytes by a mechanism that was blocked by the histamine H2-receptor antagonist, cimetidine. This is a curious finding as bovine tracheal smooth muscle normally does not express the histamine H2-receptor subtype (see Chand & Sofia, 1995) and suggests that in the studies of Hershenson et al. (1995), the process of culture per se or factors in the culture medium may have induced the histamine H2 receptor gene, which then predominated in the tissue.

While the present and another investigation (Dessy et al., 1998) provide persuasive evidence that the MKK-1/ERK pathway regulates contraction of smooth muscle, they do not agree with all published studies. Thus, PD 098059 does not inhibit agonist-induced contractions of guinea-pig bronchi (Tsang et al., 1998), porcine carotid artery (Gorenne et al., 1998) or canine pulmonary artery (Yamboliev et al., 2000). Although those experiments were not conducted in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, Yamboliev et al. (2000) have argued against a role for ERK in agonist-induced force generation and, instead, provide evidence that heat shock protein-27 (HSP-27), which is a substrate for p38 MAP kinase in intact cells, is a primary regulator of smooth muscle contractility. Evidence to support that assertion was that SB 203580, an inhibitor of the α- and β-isoforms of p38 MAP kinase (Tong et al., 1997; Young et al., 1997), suppressed the rate and magnitude of phenylephrine-induced contractions and the phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase effected by endothelin-1 (Yamboliev et al., 2000). Furthermore, SB 203580 and a neutralizing antibody against HSP-27 attenuated endothelin-1-evoked force development in staphylococcus α-toxin-skinned muscle fibres whereas PD 098059 was inactive (Yamboliev et al., 2000). Those results are difficult to reconcile with our inability to detect phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase in histamine-stimulated bovine tracheal smooth muscle indicating that HSP-27 is unlikely to participate in H1-receptor-mediated contraction. It is plausible that the contribution of the MKK-1/ERK and p38 MAP kinase/HSP-27 pathways to smooth muscle contraction may be receptor-dependent as p38 MAP kinase is phosphorylated by the muscarinic agonist, carbachol, in canine trachealis (Hedges et al., 2000; Larsen et al., 1997) although whether this is mediated through the M2 or M3 receptor subtype is unexplored.

Anti-spasmogenic activity of procaterol

Pre-treatment of bovine trachealis with the β2-adrenoceptor agonist, procaterol, also exerted an anti-spasmogenic influence on histamine-induced tension generation but this effect differed from that produced by PD 098059 in that it was seen in the absence and presence of EGTA. One interpretation of these results is that procaterol inhibits those processes that control both Ca2+-dependent and independent contractions. Indeed, cyclic AMP-elevating drugs can act at several sites in airways smooth muscle to lower the [Ca2+]c, and evidence is also available for an action at the level of the contractile proteins (see Giembycz & Raeburn, 1991). In the present study, we have demonstrated that procaterol reduced the basal and histamine-induced phosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2 by a β-adrenoceptor-mediated mechanism. In view of the ability of PD 098050 to antagonize histamine-induced contraction under Ca2+-free conditions and the general consensus that pERK represents the endogenous caldesmon kinase in airways smooth muscle (Gerthoffer et al., 1997), β2-adrenoceptor agonists may prevent histamine-induced force generation, in part, by preventing the activation of the MKK-1/ERK signalling cascade.

A limited number of additional experiments were conducted to assess the role of the cyclic AMP/PKA cascade in procaterol-induced dephosphorylation of ERK. The finding that neither CTX, which increased cyclic AMP mass 8 fold, nor Sp-8-Br-cAMPS mimicked the effect of procaterol implies that activation of adenylyl cyclase does not underlie this effect. This interpretation is strengthened by the knowledge that Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, a cell permeant and competitive inhibitor of PKA, failed to antagonize the ability of procaterol to dephosphorylate ERK. As β-adrenoceptors can, under certain circumstances, couple to effectors via the inhibitory GTP-binding protein, Gi (Daaka et al., 1997), we also determined if inactivation of Gi would block the effect of procaterol. However, overnight pre-treatment of bovine trachealis with PTX, which catalyzes the NAD+-dependent ADP ribosylation of the α-subunit, failed to inhibit procaterol-induced ERK dephosphorylation. Thus, the β2-adrenoceptor in bovine trachealis must couple to an alternative signalling pathway that negatively regulates the MKK-1/ERK cascade independently of cyclic AMP and Giα.

Conclusion

The results of this study are consistent with a causal relationship between activation of the MKK-1/ERK cascade and Ca2+-independent histamine-induced contraction of bovine tracheal smooth muscle. We also speculate that part of the anti-spasmogenic activity of β2-adrenceptor agonists is due to the inhibition of ERK phosphorylation. The identity of the down-stream targets that ultimately control force is a matter of some conjecture (see Introduction) but both caldesmon and calponin have been implicated.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank GlaxoWellcome and the Wellcome Trust for financial support. A. Koch and M.A. Lindsay were supported by the Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina (BMBF-LPD 9701-12), Halle, Germany, and the Wellcome Trust (# 056814) respectively.

Abbreviations

- 8-Br-cAMPS

8-bromo-cyclic adenosine-3′,5′-monophosphorothioate

- [Ca2+]c

cytosolic free calcium concentration

- CTX

cholera toxin

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- HSP-27

heat shock protein-27

- LC20

20 kDa myosin light chains

- MAP

mitogen-activated protein

- MKK

MAP kinase kinase

- MLCK

myosin light chain kinase

- PMSF

phenyl-methyl-sulphonyl-fluoride

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- RIA

radioimmunoassay

- TCA

trichloroacetic acid

References

- ADAM L.P., HATHAWAY D.R. Identification of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation sequences in mammalian h-Caldesmon. FEBS Lett. 1993;322:56–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81110-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALESSI D.R., CUENDA A., COHEN P., DUDLEY D.T., SALTIEL A.R. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARNER A., PFITZER G. Regulation of cross-bridge cycling by Ca2+ in smooth muscle. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;134:63–146. doi: 10.1007/3-540-64753-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BREMERICH D.H., WARNER D.O., LORENZ R.R., SHUMWAY R., JONES K.A. Role of protein kinase C in calcium sensitization during muscarinic stimulation in airway smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:L775–L781. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.4.L775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAND N., SOFIA R.D.Histamine Airways Smooth Muscle: Neurotransmitters, Amines, Lipid Mediators and Signal Transduction 1995Basel, Switzerland: Birkhauser Verlag AG; 131–155.eds. Raeburn, D. & Giembycz, M.A. pp [Google Scholar]

- CLARK T., NGAI P.K., SUTHERLAND C., GROSCHEL-STEWART U., WALSH M.P. Vascular smooth muscle caldesmon. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:8028–8035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAAKA Y., LUTTRELL L.M., LEFKOWITZ R.J. Switching of the coupling of the β2-adrenergic receptor to different G proteins by protein kinase A. Nature. 1997;390:88–91. doi: 10.1038/36362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIS R.J. The mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:14553–14556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DESSY C., KIM I., SOUGNEZ C.L., LAPORTE R., MORGAN K.G. A role for MAP kinase in differentiated smooth muscle contraction evoked by α-adrenoceptor stimulation. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:C1081–C1086. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.4.C1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUDLEY D.T., PANG L., DECKER S.J., BRIDGES A.J., SALTIEL A.R. A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:7686–7689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERTHOFFER W.T., POHL J. Caldesmon and calponin phosphorylation in regulation of smooth muscle contraction. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1994;72:1410–1414. doi: 10.1139/y94-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERTHOFFER W.T., YAMBOLIEV I.A., POHL J. , HAYNES R., DANG S., MCHUGH J. Activation of MAP kinases in airway smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:L244–L252. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.2.L244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERTHOFFER W.T., YAMBOLIEV I.A., SHEARER M., POHL J., HAYNES R., DANG S., SATO K., SELLERS J.R. Activation of MAP kinases and phosphorylation of caldesmon in canine colonic smooth muscle. J. Physiol. (Lond). 1996;495:597–609. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIEMBYCZ M.A., RAEBURN D. Putative substrates for cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases and the control of airway smooth muscle tone. J. Auton. Pharmacol. 1991;11:365–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1991.tb00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GORENNE I., SU X., MORELAND R.S. Inhibition of p42 and p44 MAP kinase does not alter smooth muscle contraction in swine carotid artery. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:H131–H138. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.1.H131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEDGES J.C., OXHORN B.C., CARTY M., ADAM L.P., YAMBOLIEV I.A., GERTHOFFER W.T. Phosphorylation of caldesmon by ERK MAP kinases in smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;278:C718–C726. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.4.C718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERSHENSON M.B., CHAO T.S., ABE M.K., GOMES I., KELLEHER M.D. , SOLWAY J., ROSNER M.R. Histamine antagonizes serotonin and growth factor-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in bovine tracheal smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:19908–19913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.19908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IIZUKA K., DOBASHI K., YOSHII A., HORIE T., SUZUKI H., NAKAZAWA T., MORI M. Receptor-dependent G-protein-mediated Ca2+-sensitization in canine airway smooth muscle. Cell Calcium. 1997;22:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATOCH S.S., MORELAND R.S. Agonist and membrane depolarization induced activation of MAP kinase in the swine carotid artery. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:H222–H229. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.1.H222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KELLEHER M.D., ABE M.K., CHAO T.S., JAIN M., GREEN J.M., SOLWAY J., ROSNER M.R., HERSHENSON M.B. Role of MAP kinase activation in bovine tracheal smooth muscle mitogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:L894–L901. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.6.L894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KHALIL R.A., MORGAN K.G. PKC-mediated redistribution of mitogen-activated protein kinase during smooth muscle cell activation. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;265:C406–C411. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.2.C406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAZAWA T., GAYLINN B.K., DENNEY G.H., SOMLYO A.P. G-protein-mediated Ca2+ sensitization of smooth muscle contraction through myosin light chain phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1991a;266:1708–1715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAZAWA T., MASUO M., SOMLYO A.P. G-protein-mediated inhibition of myosin light-chain phosphatase in vascular smooth muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991b;88:9307–9310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAZAWA T., TAKIZAWA N., IKEBE M., ETO M. Reconstitution of protein kinase C-induced contractile Ca2+ sensitization in Triton X-100-demembranated rabbit arterial smooth muscle. J. Physiol. (Lond). 1999;520:139–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LARRIVEE J.F., BACHVAROV D.R., HOULE F., LANDRY J. , HUOT J., MARCEAU F. Role of the mitogen-activated protein kinases in the expression of the kinin B1 receptors induced by tissue injury. J. Immunol. 1998;160:1419–1426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LARSEN J.K., YAMBOLIEV I.A., WEBER L.A., GERTHOFFER W.T. Phosphorylation of the 27-kDa heat shock protein via p38 MAP kinase and MAPKAP kinase in smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:L930–L940. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.5.L930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MENICE C.B., HULVERSHORN J., ADAM L.P., WANG C.A., MORGAN K.G. Calponin and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in differentiated vascular smooth muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25157–25161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NGAI P.K, WALSH M.P. Inhibition of smooth muscle actin-activated myosin Mg2+-ATPase activity by caldesmon. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:13656–13659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAGE K., HERSHENSON M.B. Mitogen-activated signaling and cell cycle regulation in airway smooth muscle. Front. Biosci. 2000;5:D258–D267. doi: 10.2741/page. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TONG L., PAV S., WHITE D.M., ROGERS S., CRANE K.M., CYWIN C.L., BROWN M.L., PARGELLIS C.A. A highly specific inhibitor of human p38 MAP kinase binds in the ATP pocket. Nature (Struct. Biol). 1997;4:311–316. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSANG F., KOH A.H.M., TING W.L., WONG P.T.H., WONG W.S.F. Effects of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor PD 098059 on antigen challenge of guinea-pig airways in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:61–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN ROSSUM J.M. Cumulative dose-response curves. II. Technique for the making of dose-response curves in isolated organs and the evaluation of drug parameters. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 1963;143:299–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VICHI P., WHELCHEL A., KNOT H., NELSON M., KOLCH W., POSADA J. Endothelin-stimulated ERK activation in airway smooth-muscle cells requires calcium influx and Raf activation. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 1999;20:99–105. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.1.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATTS S.W. Serotonin activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in vascular smooth muscle: use of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor PD098059. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;279:1541–1550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBB B.L.J., HIRST S.J., GIEMBYCZ M.A. Protein kinase C isoenzymes: a review of their structure, regulation and role in regulating airways smooth muscle tone and mitogenesis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1433–1452. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINDER S.J., ALLEN B.G., CLEMENT-CHOMIENNE O., WALSH M.P. Regulation of smooth muscle actin-myosin interaction and force by calponin. Acta. Physiol. Scand. 1998;164:415–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201x.1998.tb10697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMBOLIEV I.A., HEDGES J.C., MUTNICK J.L., ADAM L.P., GERTHOFFER W.T. Evidence for modulation of smooth muscle force by the p38 MAP kinase/HSP27 pathway. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;278:H1899–H1907. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOSHII A., IIZUKA K., DOBASHI K., HORIE T., HARADA T., NAKAZAWA T., MORI M. Relaxation of contracted rabbit tracheal and human bronchial smooth muscle by Y-27632 through inhibition of Ca2+ sensitization. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1999;20:1190–1200. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.6.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOUNG P.R., MCLAUGHLIN M.M., KUMAR S., KASSIS S., DOYLE M.L., MCNULTY D., GALLAGHER T.F., FISHER S., MCDONNELL P.C., CARR S.A., HUDDLESTON M.J., SEIBEL G., PORTER T.G., LIVI G.P., ADAMS J.L., LEE J.C. Pyridinyl imidazole inhibitors of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase bind in the ATP site. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:12116–12121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]