Abstract

Mast cells derive from the bone marrow and are responsible for the development of allergic and possibly inflammatory reactions. Mast cells are stimulated by immunoglobulin E (IgE) and specific antigen, but also by a number of neuropeptides such as neurotensin (NT), somatostatin or substance P (SP), to secrete numerous pro-inflammatory molecules that include histamine, cytokines and proteolytic enzymes.

Chondroitin sulphate, a major constituent of connective tissues and of mast cell secretory granules, had a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on rat peritoneal mast cell release of histamine induced by the mast cell secretagogue compound 48/80 (48/80). This inhibition was stronger than that of the clinically available mast cell ‘stabilizer' disodium cromoglycate (cromolyn). Inhibition by chondroitin sulphate increased with the length of preincubation and persisted after the drug was washed off, while the effect of cromolyn was limited by rapid tachyphylaxis.

Immunologic stimulation of histamine secretion from rat connective tissue mast cells (CTMC) was also inhibited, but this effect was weaker in umbilical cord-derived human mast cells and was absent in rat basophilic leukemia (RBL) cells which are considered homologous to mucosal mast cells (MMC). Oligo- and monosaccharides were not as effective as the polysaccharides.

Inhibition, documented by light and electron microscopy, involved a decrease of intracellular calcium ion levels shown by confocal microscopy and image analysis. Autoradiography at the ultrastructural level showed that chondroitin sulphate was mostly associated with plasma and perigranular membranes.

Chondroitin sulphate appears to be a potent mast cell inhibitor of allergic and nonimmune stimulation with potential clinical implications.

Keywords: Chondroitin sulphate, disodium cromoglycate, heparin, histamine, mast cells, proteoglycans, secretion

Introduction

Mast cells derive from the bone marrow and migrate into connective and mucosal tissues (Galli, 1993), where they are located at strategic points around capillaries close to nerve endings (Theoharides, 1996). Mast cells are critical for allergic reactions where the stimulus is immunoglobulin E (IgE) and specific antigen; however, there are also other nonimmune mast cell triggers that include anaphylatoxins, kinins, cytokines, as well as various neuropeptides (Baxter & Adamik, 1978; Coffey, 1973) such as somatostatin (Theoharides & Douglas, 1978), neurotensin (NT) (Carraway et al., 1982) and substance P (SP) (Fewtrell et al., 1982). When stimulated, mast cells synthesize and secrete numerous vasoactive, nociceptive and inflammatory mediators (Galli, 1993) that include histamine, kinins, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, cytokines, as well as the proteolytic enzymes chymase and tryptase (Schwartz, 1987). Such evidence has implicated mast cells also in inflammatory conditions (Galli, 1993; Theoharides, 1996). Sulphated proteoglycans constitute the major constituents of mast cell secretory granules. Of these, heparin is mostly found in connective tissue mast cells (CTMC), while chondroitin sulphate in MMC (Seldin et al., 1985b; Razin et al., 1983). Recent evidence indicates that chondroitin sulphate is also present in human connective tissue (Krilis et al., 1992) and umbilical cord-derived human mast cells (Blom et al., 1996).

A number of compounds have been reported to block rat mast cell secretion experimentally. These include the lodoxomides (Johnson, 1980), doxantrazole (Pearce et al., 1982; Fox et al., 1988), quercetin (Fox et al., 1988; Fewtrell & Gomperts, 1977) and certain histamine-1 receptor antagonists such as hydroxyzine (Theoharides et al., 1985; Fischer et al., 1995) and ketotifen (Nemeth et al., 1987). The only clinically available ‘anti-allergic' drugs are cromolyn (Orr et al., 1971) and its structurally related nedocromil (Enerbäck & Bergström, 1989); yet, they are not capable of effectively blocking human mast cell secretion (Okayama et al., 1992). In addition, the inhibitory action of these drugs is short-lived due to the induction of tachyphylaxis (Theoharides et al., 1980) and they do not inhibit mucosal mast cells (MMC) (Barrett & Metcalfe, 1985; Pearce et al., 1982; Fox et al., 1988). Among mast cell derived molecules, histamine has an autoinhibitory action only in the brain through activation of histamine-3 receptors (Rozniecki et al., 1999), while arachidonic acid products have variable and weak inhibitory effects (Theoharides, 1990). We hypothesized that chondroitin sulphate released from inflamed tissue, as well as from mast cells, could have an inhibitory effect on mast cell secretion. Here we show that chondroitin sulphate is a potent inhibitor of histamine release from CTMC.

Methods

Mast cell purification and treatment

Peritoneal mast cells were isolated from male (250–300 g) Sprague Dawley rats (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME, U.S.A.) using Locke's solution (mM: NaCl 150, KC1 5, HEPES 5, CaC12 2, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Dextrose, pH 7.2) and were purified (>95%) by centrifugation through 22.5% Metrizamide (Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp., Westbury, NY, U.S.A.) (Theoharides et al., 1982); the remaining cells were lymphocytes and a few macrophages. The cell pellet was washed and resuspended (105 cells ml−1) in Locke's solution. Following the indicated incubation times with either disodium cromoglycate, chondroitin sulphate C from shark cartilage or the mono- and disaccharides (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), the cells were washed by centrifugation at 350×g for 5 min at room temperature and resuspended in Locke's solution. The chondroitin sulphate was reported to be over 90% pure type C, balanced with type A. In some cases, chondroitin sulphate and 3H-chondroitin sulphate (see below), was dissolved in 40 mM NaCl to dissociate any loose interaction with other smaller molecules and was then filtered and washed through a 50K exclusion filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA, U.S.A.) to remove any such molecules. Mast cells were stimulated with either: (a) 0.1 μg ml−1 compound 48/80 (48/80); (b) 5×10−5 M SP in Locke's solution without Ca++ plus 0.1 mM EDTA (to chelate any extracellular calcium) for 30 min; (c) immunologically (see below).

Culture of RBL cells

The rat basophilic leukaemia (RBL) cells are considered homologous to rat mucosal mast cells (Seldin et al., 1985a). They were kindly provided by Dr Henry Metzger (NIH) and were grown as described previously (Isersky et al., 1975).

Isolation and culture of umbilical cord-derived human mast cells

Human umbilical cord blood samples were obtained from normal full-term deliveries under the approval from the Human Investigation Review Board. Cord blood was collected in tubes containing 10 U ml−1 heparin and was diluted with twice the volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mast cell progenitors were separated as described before (Kempuraj et al., 1999). Mononuclear cells were separated by density-gradient centrifugation using Lymphocyte Separation Medium (LSM; Organon Teknika Corp, Durham, NC, U.S.A.). The interface containing mononuclear cells was collected and CD34+ cells were separated using a magnetic separation column according to the manufacturer's instructions (Macs II, 441-01; Miltenyl Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Magnetic microbeads were removed with the CD34+ isolation kit (Miltenyl Biotec). The CD34+ cells were further separated with mouse anti-CD34 antibody followed by antimouse IgG1 magnetic microbeads (Miltenyl Biotec). The CD34+ cells were cultured in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, U.S.A.) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 ng−1ml human stem cell factor (SCF) from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA, U.S.A.) and 50 ng ml−1 IL-6 (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA, U.S.A.) in 75-cm2 flasks at 37°C in 5% CO2, for greater than 10 weeks (Kinoshita et al., 1999).

Immunologic stimulation of mast cells

Unpurified rat peritoneal mast cells (106 ml−1) were first incubated with 1.5 μg/105cells ml−1 rat IgE (Zymed, So. San Francisco, CA, U.S.A.) for 30 min in order to occupy the respective receptors to protect them from destruction during the purification step (Coutts et al., 1980); mast cells were then incubated with rabbit anti-IgE (3–15 μg/104 cells ml−1) (Zymed) for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by centrifuging the cells at 350×g for 5 min at 4°C.

Human mast cells were sensitized with human IgE (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, U.S.A.) at 1.5 μg ml−1 for 48–72 h. Then the cells were washed with Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, U.S.A.) solution and Human Tyrode solution once in each. These cells were then challenged with anti-human IgE (Dako, Carpenteria, CA, U.S.A.) at 15 μg ml−1 for 30 min with or without pretreatment with the test compound in a shaking water bath at 37°C. The supernatant was then collected by centrifugation at 350×g for 5 min for the histamine release assay.

RBL-2H3 cells were stimulated as 1.5×10−5 cells per well in 12-well plates. RBL cells were used at mid-logarithmic stage, day 2 of culture postplating, as shown on the growth curve (Trnovsky et al., 1993). After 48 h, cells were washed twice with PBS and sensitized for 24 h with 1.0 μg ml−1 of rat monoclonal IgE to dinitrophenol (DNP) (Zymed). Cells were washed twice with PBS and stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 DNP-BSA (Sigma) for 30 min in 37°C.

For histamine secretion the supernatant and the cell pellet, to which an equal volume of Locke's or Tyrode's solution had been added, were acidified with 20% perchloric acid. Following freezing and boiling for 5 min, both supernatant and pellet were centrifuged at 17,000×g for 5 min to remove denatured protein, and histamine was assayed fluorometrically (Theoharides et al., 1982). The results are expressed as (supernatant/supernatant+pellet) ×100. The data for each incubation time and condition are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (s.e.mean) and statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA.

Intracellular calcium measurement

Mast cells (106 ml−1) were incubated with 5 μg/ml of crimson calcium AM cell permeant probe (Cat. No. C-3018, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.) for 5 min at 37°C in Locke's solution without calcium and 0.1 mM EDTA. This indicator dye has been used effectively to measure intracellular calcium ion levels (Scheenen et al., 1998; Herman, 1997; June & Rabinovitch, 1994). Mast cells were washed and resuspended in Locke's solution without calcium and 0.1 mM EDTA. Mast cells (180 μl) were then incubated with 0.1 μg ml−1 compound 48/80 with or without preincubation with chondroitin sulphate for 10 min at room temperature in an open topped Sykes-Moore chamber. They were examined with a Confocal Laser Scanning Imaging System Odyssey XL (Norans Instruments) equipped with a Crypton-Argon laser set at 560λ (42% intensity) and attached to a Silicon Graphics computer. For image analysis, a field of cells (usually six to 10) was selected. Photography was started taking one frame every 20 s immediately after the addition of the study drug or the secretagogue (20 μl) for 10 min. Image analysis was performed using Image Pro Plus imaging software (Media Cibernetics, 8484 Georgia Avenue, Silver Springs, MD, U.S.A.). Each cell was analysed separately. Final magnification of 600× was used. Fifteen photographic images for each sample were printed on one 8×10 sheet of photographic paper and the images were subsequently digitized for analysis. First, a low threshold was established that extinguished the last image pixel. Thereafter, and at time points through 10 min, pixel values were recorded in response to drug treatment. The illuminated pixel values, representing areas, were then read from the program and plotted on graph paper.

Microscopy

For light microscopy, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed with PBS, aliquoted onto slides and stored at −20°C for further analysis. For electron microscopy, after immersion fixation of the cell pellet in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, the samples were washed in PBS, post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in graded ethanol solutions and embedded in Epon. Semi-thin sections (0.5 μm) were stained with toluidine blue, while ultrathin sections (1000 A) were contrasted in 7.5% uranyl acetate in 50% ethanol and 0.1% aqueous lead citrate. Grids with the sections were examined and photographed using a Phillips CM-10 transmission electron microscope. For autoradiography, chondroitin sulphate was custom-tritiated at New England Nuclear (Boston, MA, U.S.A.) and was made available at specific activity of 4.3 mCi ml−1; 105 mast cells were incubated with 2.5 mCi 3H-chondroitin sulphate for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were then washed twice, fixed and processed for autoradiography at the ultrastructural level without the uranyl acetate step; they were stained with lead citrate for 7.5 min (instead of 3 min when uranyl acetate is present). The cells were then examined and photographed using a Phillips-CM-10 transmission electron microscope; exposure was carried out for 7 days at 4°C.

Results

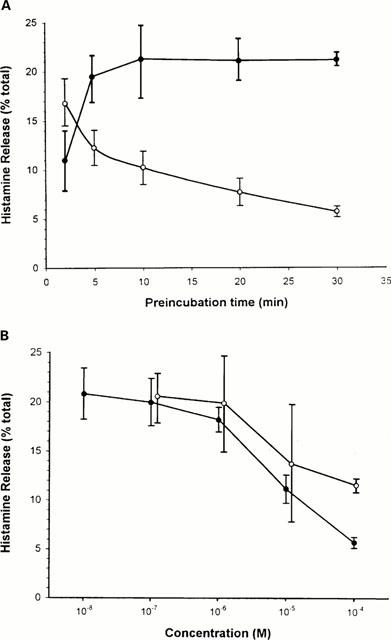

Histamine release from rat CTMC stimulated with 0.1 μg ml−1 of the classic mast cell secretagogue compound 48/80 (48/80) was 22.1±1.3% (n=19). Preincubation with chondroitin sulphate resulted in inhibition of histamine release in response to 48/80 (0.1 μg ml−1 used for 30 min at 37°C); inhibition increased with time and reached a maximum of 76.5% (P=0.0004) by 10 min (Figure 1A). In contrast, the inhibitory action of cromolyn decreased rapidly if preincubation lasted for more than 1 min (Figure 1A). We then investigated whether this inhibitory effect may had been due to some electrostatic interaction between the negatively charged chondroitin sulphate and the cationic 48/80, leading to neutralization of the latter. Following incubation with 10−5 M chondroitin sulphate for 10 min at 37°C, mast cells were washed up to five times before stimulation with 0.1 μg ml−1 48/80; the extent of inhibition was not diminished by the washes (results not shown). We also investigated how long the inhibitory activity of chondroitin sulphate lasted after two washes. Mast cells were incubated with 10−5 M chondroitin sulphate for 10 min at 37°C, washed twice in Locke's solution and then stimulated by 0.1 μg ml−1 48/80 either immediately after or at 5, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min after the wash; there was no statistically significant reduction of the inhibitory effect even when 48/80 was added 2 h later (results not shown).

Figure 1.

(A) Time-course relationship of the inhibitory effect of chondroitin sulphate on compound 48/80-induced histamine release. Purified rat peritoneal mast cells (105 ml−1) were preincubated with 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate or cromolyn for the times indicated followed by stimulation with 0.1 μg ml−1 48/80 for 30 min at 37°C. Open circles=cromolyn; solid circles=chondroitin sulphate. (B) Dose-response relationship of the inhibitory effect of chondroitin sulphate on compound 48/80-induced histamine release. Purified rat peritoneal mast cells (105 ml−1) were first incubated with or without chondroitin sulphate or cromolyn obtained from Sigma (St. Louis) for 10 or 1 min, respectively at 37°C. After incubation with the designated concentrations of chondroitin sulphate, mast cells were washed twice in Locke's solution and were stimulated with 0.1 μg ml−1 48/80 for 30 min at 37°C. Open circles=cromolyn; solid circles=chondroitin sulphate.

Pre-incubation with chondroitin sulphate for 10 min at 37°C inhibited histamine release in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1B). The inhibitory effect of chondroitin sulphate was comparable to that of cromolyn, but chondroitin sulphate was more potent at the highest concentrations. Maximal inhibition of 76% (P=0.0004) was seen at 10−4 M when histamine release decreased from 22.0±1.3% (n=19) to 5.7±0.6% (n=13). At 10−5 M (n=6), histamine decreased to 11.2±1.4% (49.4% inhibition, P<0.05) and at 10−6 M (n=6), it decreased to 18.2±1.3% (17.3% inhibition, P<0.05). There was only 9.4% inhibition at 10−7 M (n=7) with histamine release at 19.9±2.4% which was borderline significant. At 10−8 M (n=4), there was no inhibition and histamine release was 20.8±2.6% (P>0.05).

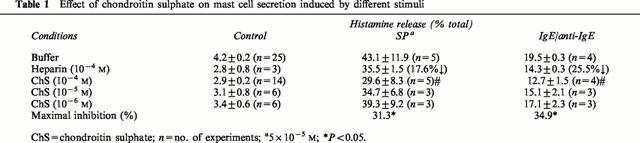

The inhibitory effect of chondroitin sulphate extended to stimulation of rat CTMC by the neuropeptide SP, as well as by immunoglobulin E and anti-IgE; this inhibition also showed a dose-response relationship (Table 1). The inhibition seen with 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate on histamine release triggered by 5×10−5 M SP was less (31.3%) than that seen with 48/80 (76%); this difference may possibly be due to the fact that stimulation by SP was stronger (43.1±11.9, n=5) than that induced by 48/80 (22.1±1.3, n=19) in the absence of extracellular calcium. When mast cells were stimulated by a lower concentration (10−5 M) of SP instead, histamine release was decreased to 25.3±1.4% (n=3) and inhibition by 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate increased to 69.2% (n=3). Histamine secretion induced immunologically was 19.5±2.3% (n=4) and was reduced to 12.7±1.5% (n=4) by 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate, an effect that was statistically significant (P=0.014). Lower concentrations of chondroitin sulphate gave weaker and variable results.

Table 1.

Effect of chondroitin sulphate on mast cell secretion induced by different stimuli

In order to study the size or charge requirement of chondroitin sulphate, we compared its inhibitory action at 10−5 M on immunologic stimulation of rat CTMC to that of high (HMW) and low molecular weight (LMW) heparin, as well as chondroitin sulphate disaccharide, and the monosaccharides D-glucosamine sulphate and N-acetyl-glucosamine (10−4 M). They were all weaker inhibitors than chondroitin sulphate (Table 2). For instance, chondroitin sulphate disaccharide inhibited immunologically stimulated histamine release by 23.6%, as compared to equimolar concentrations of the parent molecule (Table 2). The monosaccharides D-glucosamine sulphate and N-acetylglucosamine inhibited histamine release by 20.0 and 24.6%, respectively. Finally, HMW heparin was weaker than chondroitin sulphate with 25.5% inhibition, while LMW heparin inhibited histamine release only by 10.3% (Figure 2). Thus, it appeared that the size and degree of sulphation are important.

Table 2.

Effect of oligosaccharides on rat mast cell secretion triggered by IgE/Anti-IgE

Figure 2.

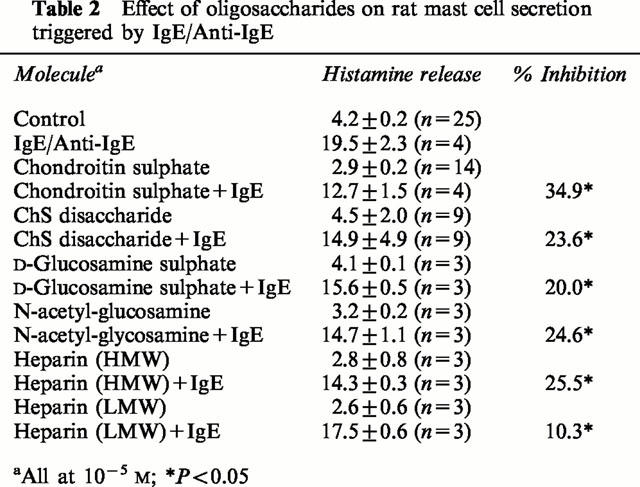

Photomicrographs of mast cells showing inhibition of degranulation by chondroitin sulphate. Purified mast cells (>95%) were washed and resuspended in the Locke's solution. They were observed and photographed after staining with Giemsa. (A) Control; (B) preincubated with 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate; (C) stimulated with 0.1 μg ml−1 C48/80 alone for 30 min at 37°C or (D) after 10 min preincubation with 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate. Bar=10 microns.

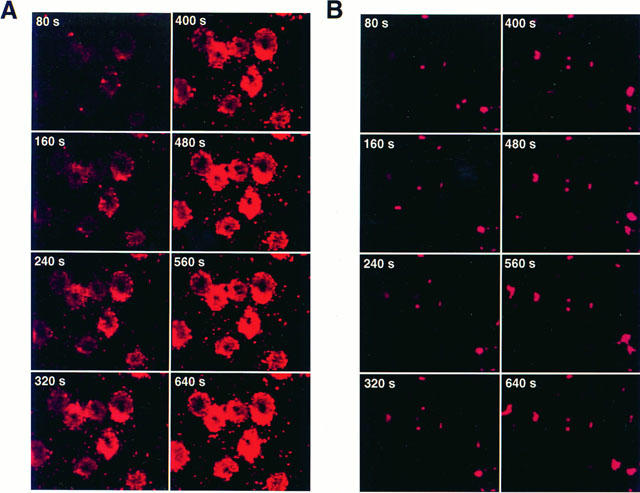

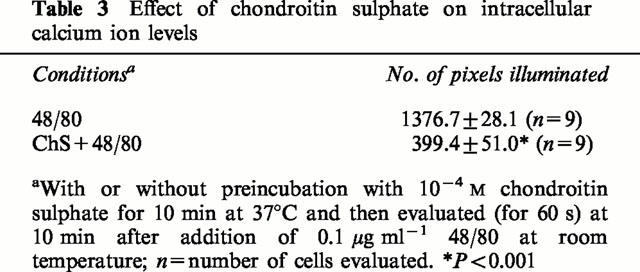

We also examined the morphologic appearance of rat CTMC treated with chondroitin sulphate. Control (untreated) mast cells and those preincubated with 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate for 10 min at 37°C were intact (Figure 2A,B,) as shown after staining with Giemsa. Stimulation with 0.1 μg ml−1 48/80 made most mast cells release their contents to various degrees (compare Figure 2A,C). Preincubation with 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate for 10 min at 37°C, before stimulation with 48/80, largely inhibited degranulation (compare Figure 2C,D). The possibility that the mechanism of action of chondroitin sulphate may be mediated through an effect on the availability of intracellular calcium ions was then investigated. Mast cells were loaded with the calcium indicator dye crimson red in the absence of extracellular calcium, were washed and observed in Locke's solution using a confocal microscope. Stimulation of secretion by 0.1 μg ml−1 48/80 at room temperature led to a gradual increase in intracellular calcium ion levels shown in 20 s frames over a 10 min period (Figure 3A). Preincubation with 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate for 10 min at 37°C prior to stimulation with 48/80 at room temperature inhibited calcium ion levels significantly (compare Figure 3A,B). The extent of the inhibitory effect on intracellular calcium ion levels was confirmed with image analysis. Preincubation with chondroitin sulphate (10−4 M) decreased the number of pixels from 1376.7±28.1 (n=9) illuminated 10 min after addition of compound 48/80 at 24°C to 399.4±51.0 (n=9), more than a 70% (P<0.05) reduction (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of mast cells obtained every 20 s showing the effect of chondroitin sulphate on intracellular calcium ion levels. Mast cells were observed after loading with Crimson calcium AM. They were either (A) stimulated with 0.1 μg ml−1 48/80 alone for 10 min at room temperature or (B) after 10 min preincubation with 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate. Bar=10 microns.

Table 3.

Effect of chondroitin sulphate on intracellular calcium ion levels

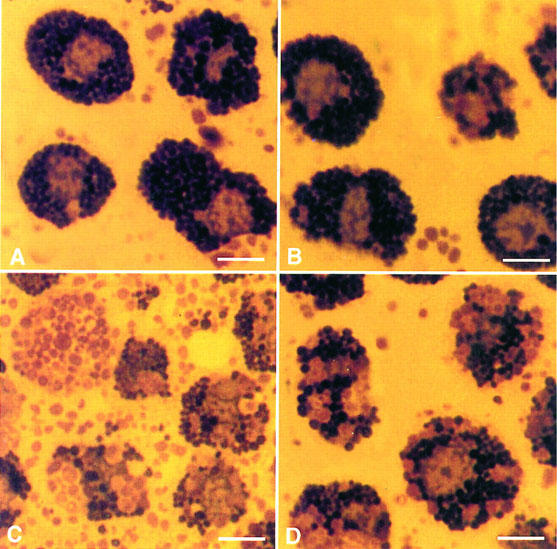

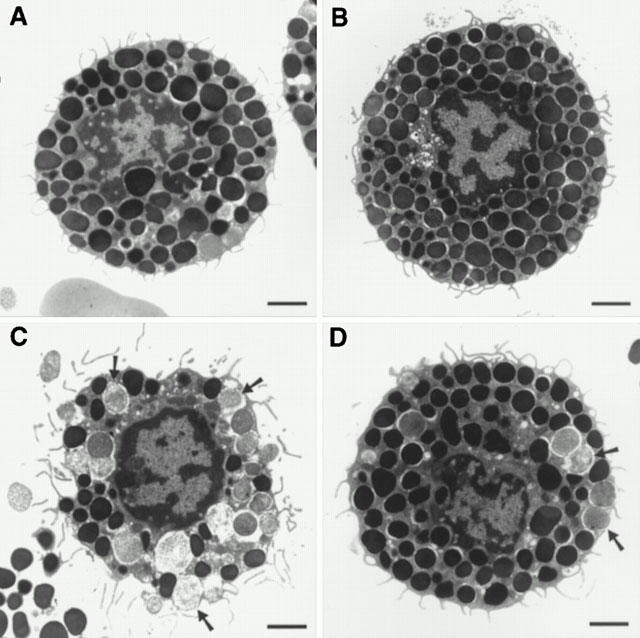

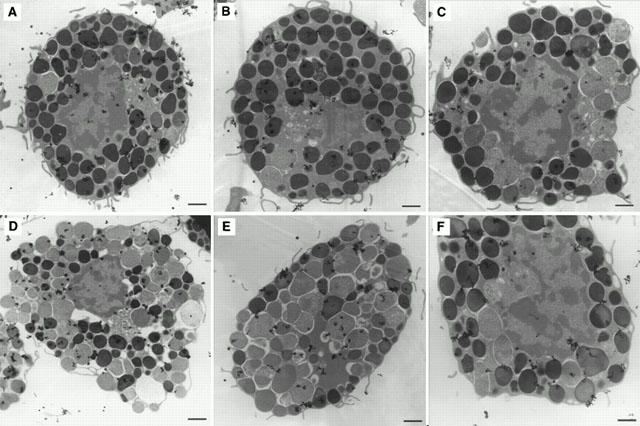

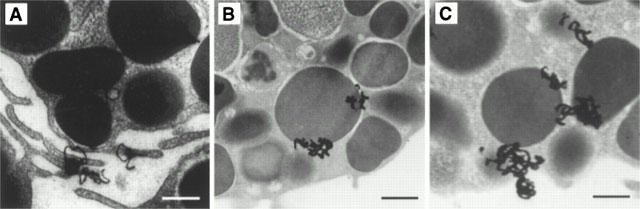

The inhibitory effect of chondroitin sulphate was also confirmed by transmission electron microscopy. Ultrastructural observations showed most control mast cells (Figure 4A) and those treated with 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate for 10 min at 37°C (Figure 4B) to contain intact, homogenous electron dense granules. In contrast, mast cells stimulated by 0.1 μg ml−1 48/80 had undergone extensive degranulation and had lost the electron dense content of most of their secretory granules (Figure 4C). Mast cells incubated with 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate for 10 min at 37°C before stimulation with 0.1 μg ml−1 48/80 also contained mostly intact electron dense granules (Figure 4D). The possible site of action of chondroitin sulphate was investigated by using tritiated chondroitin sulphate. Autoradiography at the ultrastructural level showed that, after a 30 min incubation, 3H-chondroitin sulphate radioactivity could not be removed even by five washes and was mostly associated with the mast cell surface and perigranular membranes (Figures 5 and 6). It is interesting to note that 3H-chondroitin sulphate-related radioactivity appeared to be least associated with the nucleus or secretory granules that had undergone exocytosis (Figures 5B and 6).

Figure 4.

Electron photomicrographs of mast cells showing the inhibitory effect of chondroitin sulphate. (A) Control; (B) 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate for 30 min at 37°C; (C) 0.1 μg ml−1 compound 48/80 for 30 min at 37°C; (D) preincubation with 10−4 M chondroitin sulphate for 30 min at 37°C, washed twice, and stimulated with 0.1 μg ml−1 compound 48/80 for 30 min at 37°C. Bar=1 micron.

Figure 5.

Electron autoradiographs showing non-random distribution of 3H-chondroitin sulphate after 30 min incubation at 37°C. (A–C) Note deposition of 3H-chondroitin sulphate-related radioactivity (grains) mostly in association with intact secretory granules and the cell surface; (D–F) note relative absence of grains from the nucleus and secretory granules that had undergone exocytosis. Magnification=×15,600. Bar=1 micron.

Figure 6.

Electron autoradiographs showing the presence of 3H-chondroitin sulphate after 30 min of incubation at 37°C. (A) Note deposition of 3H-chondroitin sulphate-related radioactivity (grains) in association with the mast cell surface, especially filopodia. (B,C) Note grains are adjacent to secretory granule membranes. Magnification=×19,800. Bar=0.5 microns.

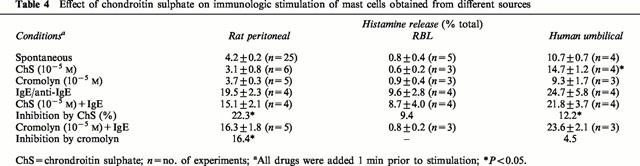

We then investigated if the inhibitory effect of chondroitin sulphate was limited only to rat CTMC. For that reason, we tested it against immunologic stimulation of RBL and human cultured mast cells. While chondroitin sulphate (10−5 M) inhibited immunologic histamine release from rat CTMC by 22% (Table 4), it had no effect (9.4% inhibition, P>0.05) on histamine release from RBL cells which are homologous to rat MMC (Table 4). Histamine release from umbilical cord-derived human mast cells was decreased (Table 4) from 24.7±5.8% to 21.8±3.7%, a 12.2% reduction (P<0.05). Cromolyn used under the same conditions inhibited CTMC by 16.4%, had no effect on RBL cells, and inhibited human cultured mast cells by 4.5% which was not statistically significant.

Table 4.

Effect of chondroitin sulphate on immunologic stimulation of mast cells obtained from different sources

Discussion

The present results show that chondroitin sulphate is a potent inhibitor of mast cell secretion. Chondroitin sulphate is a natural constituent of connective tissues (Hardingham, 1986), especially cartilage (Lindahl & Hook, 1978). Chondroitin sulphate is also present in both rat MMC (Seldin et al., 1985b; Razin et al., 1983) and basophils (Orenstein et al., 1978; Reilly et al., 1988; Seldin et al., 1985b; Metcalfe et al., 1984), as well as in human CTMC (Krilis et al., 1992) and umbilical cord-derived human mast cells (Blom et al., 1996). The inhibitory action of chondroitin sulphate on histamine release was more potent than of the ‘antiallergic' drug cromolyn, especially at higher concentrations. Heparin, the structure of which is quite similar to that of chondroitin sulphate and is also stored in mast cells, had been shown to inhibit in vivo release of histamine (Dragstedt et al., 1942), the immediate response to antigen in the skin and lungs of allergic subjects (Bowler et al., 1993), as well as bronchoconstriction in exercise-induced asthma (Ahmed et al., 1993a). Heparin was also shown to prevent allergic airway hyperresponsiveness (Ahmed et al., 1994) and to have a protective effect on immunologic and non-immunologic tracheal smooth muscle contraction in vitro (Abraham et al., 1996; Ahmed et al., 1992). In fact, just as cromolyn and chondroitin sulphate appear to have roughly equivalent inhibitory activity on CTMC secretion, heparin and the cromolyn analogue nedocromil both induced inhibition of about 50% (Abraham et al., 1996) on tracheal smooth muscle contraction.

While the inhibition by cromolyn disappeared with preincubation times of more than 1 min, the inhibitory action of chondroitin sulphate started at 1 min and progressively increased over 30 min. It was previously shown that the inhibitory action of intravenous heparin in the immediate cutaneous reaction in allergic sheep was enhanced by 60% when the duration of pretreatment was increased from 20 to 60 min (Ahmed et al., 1993b). Like our findings showing that chondroitin sulphate inhibits both 48/80-induced and immunologic stimulation of mast cells, heparin had been shown to inhibit similar responses in isolated human uterine mast cells (Lucio et al., 1992). It was somewhat surprising that the inhibitory effect of chondroitin sulphate was more potent for histamine release induced by 48/80 than with SP, since both are thought to occur through the same mechanism (Mousli et al., 1990). One possible explanation may be the fact that in the absence of extracellular calcium ions, the effect of 48/80 is much weaker than that of SP (Erjavec et al., 1981), suggesting that the stronger the response the weaker the inhibition; our preliminary results using less SP appear to support this explanation.

Our ultrastructural observations showed that chondroitin sulphate prevented mast cell degranulation. Moreover, autoradiographic images suggest that chondroitin sulphate is mostly associated with the mast cell surface and the secretory granule membranes, while largely sparing the nucleus and granules that had undergone exocytosis. Similar findings had been reported in studies of 35S-chondroitin sulphate uptake in other cultured cells where chondroitin sulphate first interacted with the cell surface and by 2 h was found mostly intracellularly (Saito & Uzman, 1971c). Our results showed that the plasma membrane and the extruded secretory granules are preferentially fluorescent in our confocal microscopic images. This is in part due to the fact that the confocal microscope focuses on the surface of live cells. Even with conventional microscopy, however, the plasma membrane of cells in their resting state is preferentially stained for calcium ions (Tasaka et al., 1986; Monck et al., 1992). Previous reports using Quin-2 or Fura-2 (Penner et al., 1988; Tasaka et al., 1986; Almers & Neher, 1985; Monck et al., 1992) also showed that during stimulation of secretion, there is an increase in calcium ions associated with extruded secretory granules, possibly due to indicator dye trapped inside the granules fluorescing upon binding extracellular calcium (Almers & Neher, 1985). There is also binding of the cationic extracellular calcium to the negatively charged extruded granule proteoglycans that permits the intense granule-associated fluorescence. Real time sequence of 20 s frames showed the gradual increase of intracellular calcium upon stimulation of mast cells with 48/80 and its inhibition by chondroitin sulphate. In these frames, not only the time-dependent increase is appreciated, but the cells act as their own controls before stimulation. The precise mechanism through which chondroitin sulphate inhibits mast cell secretion is not entirely clear. Our results indicate the interaction of chondroitin sulphate with mast cells somehow led to inhibition of intracellular free calcium ion levels. This action could not be through a calcium ion channel as 48/80 is known to induce secretion utilizing intracellular calcium (Theoharides et al., 1982) and SP stimulates mast cells in the absence of extracellular calcium (Erjavec et al., 1981). Heparin had previously been reported to inhibit inositol triphosphate-induced intracellular calcium release from permeabilized rat liver cells (Hill et al., 1987).

We also do not know whether the inhibitory effect of chondroitin sulphate is mediated through its surface binding and/or some action on the perigranular membrane or both. However, it is interesting to note that mast cell treatment with neuraminidase prevented histamine release induced by SP (Cocchiara et al., 1997), implying that incorporation of chondroitin sulphate in the plasma membrane may interfere with activation, especially by neuropeptides. How chondroitin sulphate gets across the cell membrane can only be theorized at the present, but a number of publications have shown internalization of both chondroitin sulphate (Saito & Uzman, 1971a,1971b,1971c) and heparin (Letourneur et al., 1995a,1995b) by active uptake through receptor-mediated endocytosis.

Proteoglycans liberated from activated mast cells and/or connective tissues could act as natural inhibitors of mast cell secretion, thus also reducing the extent of local inflammation. The mechanism of inhibitory action of chondroitin sulphate may be through two different mechanisms. Firstly, competition of compound 48/80 or SP binding to surface proteoglycans through membrane incorporation so that it can not be washed off; for instance, neuraminidase-treated rat peritoneal mast cells could not be stimulated by 48/80 or SP (Mousli et al., 1989) and lectins specific for N-acetyl galactosamine and N-acetyl glucosamine oligomers blocked stimulation by 48/80 (Matsuda et al., 1994). Secondly, chondroitin sulphate may interfere with the action of inositol triphosphate and subsequent increases in intracellular calcium ions, especially since heparin has been shown to act as a competitive inhibitor of inositol triphosphate receptors (Kobayashi et al., 1988; Ahmed et al., 1994).

Chondroitin sulphate may have additional actions leading to inhibition of inflammatory responses in vivo. Since proteoglycans have been shown to extend the life of growth factors (Brittis et al., 1992; Nurcombe et al., 1993; Kan et al., 1993), exogenously provided chondroitin sulphate may act as a decoy to prevent or limit the action of growth factors on local immune cells or neurons. The possibility that any growth or other factors bound to chondroitin sulphate may have contributed to the inhibitory action of chondroitin sulphate in our experiments is rendered unlikely due to the fact that in certain experiments chondroitin sulphate was first dissolved in high salt to disrupt any loose interactions; it was then filtered through a 50 K exclusion filter which would have allowed any smaller molecules to be washed through. An additional possible beneficial effect of chondroitin sulphate in reducing inflammation would be its ability to bind intercellular adhesion molecules (Nelson et al., 1993), often expressed in response to TNF-α released from mast cells (Gordon et al., 1990; Walsh et al., 1991), and to neutralize proteolytic enzymes released during inflammatory responses (Zehnder & Galli, 1999; Humphries et al., 1999; Forsberg et al., 1999). It is interesting to note that heparin sulphate was recently shown to bind to CD48 (Ianelli et al., 1998), a molecule that is upregulated in various autoimmune disorders. Such findings are provocative in view of the fact that mast cells are increasingly implicated in inflammatory processes (Galli, 1993) especially those exacerbated by stress (Theoharides, 1996). For instance, mast cells have been implicated in sterile inflammatory disorders such as asthma (Barnes, 1988; Lewis & Austen, 1977), irritable bowel syndrome (Weston et al., 1993) and interstitial cystitis in the urinary bladder (Theoharides et al., 1998), in all of which a deficit of glycosaminoglycans has been reported (Shute et al., 1997; Hurst et al., 1996; Burton & Anderson, 1983).

A number of non-mast cell natural or synthetic compounds have been reported to inhibit mast cell secretion. These include lodoxamides (Johnson, 1980), doxantrozole (Pearce et al., 1982; Fox et al., 1988), quercetin (Fewtrell & Gomperts, 1977; Fox et al., 1988) and certain antihistamines such as hydroxyzine (Theoharides et al., 1985; Fischer et al., 1995) and ketotifen (Nemeth et al., 1987). Glucocorticoids do not affect anaphylactic mast cell degranulation, but prolonged treatment inhibits the synthesis of arachidonic acid products such as prostaglandins, thromboxanes and leukotrienes in response to immunologic stimulation (Robin et al., 1985; Marquardt & Wasserman, 1983). On the contrary, even overnight steroid treatment of mast cells did not affect either histamine or arachidonic acid release induced by 48/80 or somatostatin (Heiman & Crews, 1984). Cromolyn and its structurally related nedocromil known as ‘mast cell stabilizers' (Theoharides et al., 1980), are available for allergic conjunctivitis, rhinitis, asthma and food allergies (Enerbäck & Bergström, 1989; Theoharides et al., 1980; Okayama et al., 1992), even though they do not appear to be able to inhibit human mast cells (Okayama et al., 1992), as also shown herein. Moreover, their inhibitory action on histamine release is only modest, short-lived and does not inhibit histamine secretion from MMC (Barrett & Metcalfe, 1985; Pearce et al., 1982; Fox et al., 1988). Nevertheless, cromolyn was shown to inhibit tumour necrosis-α (TNF-α) release from both CTMC and MMC, an action that required 2 h pretreatment (Bissonnette et al., 1995). It is interesting that low molecular weight (LMW) heparin preferentially inhibited TNF-α and IL-4 production without affecting degranulation (Baram et al., 1997). Our preliminary results show that LMW heparin, as well as chondroitin sulphate disaccharide and related monosaccharides are weaker inhibitors of histamine secretion. Weak inhibition on mast cell secretion, has previously been reported for other mast cell derived molecules (Theoharides, 1990) such as lipoxins (Conti et al., 1992), histamine through H-3 receptors in the brain (Rozniecki et al., 1999) and interleukin-8 (Kuna et al., 1991). Inhibition of mast cell production of nitric oxide (NO) enhanced histamine release in response to compound 48/80 and SP (Brooks et al., 1999), but diminished mast cell dependent TNF-α-mediated cytotoxicity (Bissonnette et al., 1991). Both the constitutive and the antigen-induced NO production was inhibited by IL-10; however, long-term (24 h) incubation with IL-10 enhanced histamine release from CTMC (Lin & Befus, 1997). These findings imply that there may be differential inhibition of release of mast cell mediators we first reported for biogenic amines (Theoharides et al., 1982). A number of subsequent reports confirmed our original observation. For instance, vasoactive amines were differentially released in T-cell-dependent, as compared to IgE-dependent hypersensitivity reactions (Van Loveren et al., 1984). Differential release of histamine without prostaglandin D2 (Benyon et al., 1989) was reported by peptides (Levi-Schaffer & Shalit, 1989) and 48/80 (van Haaster et al., 1995), which also released almost no leukotriene C4 (Benyon et al., 1989). The anaphylatoxin C5a induced high histamine release without any leukotrienes from human basophils (Dahinden et al., 1989). Interleukin-10 stimulated IL-6 and TNF-α production without affecting histamine release (Marshall et al., 1996), while the phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase inhibitor Wortmannin inhibited mast cell exocytosis, but not IL-6 production (Marquardt et al., 1996). Stimulation with SCF resulted in IL-6 release without histamine or leukotriene C4 (Gagari et al., 1997) and bacterial lipopolysaccharide induced release of IL-6 without histamine (Leal-Berumen et al., 1994).

Differential activation of mast cells may also vary due to their content, source, as well as experimental or pathological conditions. In addition to the well-known differences in human protease content (Schwartz, 1987), human mast cells also differ in their proteoglycan (Pipkorn et al., 1988) and cytokine (Bradding et al., 1995) content. The secretory responsiveness of mast cells also varies considerably. Human mast cells appear capable of constitutively releasing histamine without tryptase (Granerus et al., 1994). MMC do not secrete in response to 48/80 or neuropeptides (Barrett & Metcalfe, 1985; Pearce et al., 1982), even though they did respond weakly only to high concentrations of SP (Ali et al., 1986; Shanahan et al., 1985). Human mast cells are refractory to the action of 48/80 or polylysine (Lowman et al., 1988b; Church et al., 1982), while skin mast cells are responsive to these synthetic compounds, as well as to SP, somatostatin and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) (Lowman et al., 1988a,1988b; Piotrowski & Foreman, 1985).

Conclusion

The present findings suggest that chondroitin sulphate may be useful as a natural ‘anti-allergic' agent. In addition, evidence that mast cells are involved in neuroinflammatory processes (Church et al., 1989; Foreman, 1987; Goetzl et al., 1985; Stead & Bienenstock, 1990; Theoharides, 1996) and are present in inflamed joints (Crisp et al., 1984; Wasserman, 1984; Metzler & Xu, 1997), may help explain (Theoharides & Boucher, 1999) a meta-analysis suggesting that chondroitin sulphate may be beneficial in osteoarthritis (McAlindon, et al., 2000). In fact the US National Institutes of Health recently sponsored a trial (NIH-NIAMS-98-2) to test the efficacy of chondroitin sulphate in osteoarthritis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Theta Biomedical Consulting and Development Co., Inc. (Brookline, MA, U.S.A.) which has been allowed US patent No. 09/056,707 covering the therapeutic use of proteoglycans in mast cell related conditions. Thanks are due to Dr Henry Metzger for the RBL cells and Amgen, Inc. for the SCF. We also thank Ms Sharon Titus for her word-processing skills.

Abbreviations

- ChS

chondroitin sulphate

- 48/80

compound 48/80

- IgE

immunoglobulin E

- NT

neurotensin

- RBL

rat basophilic leukaemia

- SP

substance P

References

- ABRAHAM W.M., ABRAHAM M.K., AHMED T. Protective effect of heparin on immunologically induced tracheal smooth muscle contraction in vitro. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1996;110:79–84. doi: 10.1159/000237315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHMED T., ABRAHAM W.M., D'BROT J. Effects of inhaled heparin on immunologic and non-immunologic bronchoconstrictor responses in sheep. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1992;145:566–570. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.3.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHMED T., GARRIGO J., DANTA I. Preventing bronchoconstriction in exercise-induced asthma with inhaled heparin. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993a;329:90–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307083290204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHMED T., LUCIO J., ABRAHAM W.M., D'BROT J. Inhibition of antigen-induced airway and cutaneous responses by heparin: A pharmacodynamic study. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993b;74:1492–1498. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHMED T., SYRISTE T., MENDELSSOHN R., SORACE D., MANSOUR E., LANSING M., ABRAHAM W.M., ROBINSON M.J. Heparin prevents antigen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness: Interference with IP3-mediated mast cell degranulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 1994;76:893–901. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.2.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALI H., LEUNG K.B.P., PEARCE F.L., HAYES N.A., FOREMAN J.C. Comparison of the histamine-releasing action of substance P on mast cells and basophils from different species and tissues. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 1986;79:413–418. doi: 10.1159/000234011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALMERS W., NEHER E. The Ca signal from fura-2 loaded mast cells depends strongly on the method of dye-loading. FEBS Lett. 1985;192:13–18. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARAM D., RASHKOVSKY M., HERSHKOVIZ R., DRUCKER I., RESHEF T., BEN-SHITRIT S., MEKORI Y.A. Inhibitory effects of low molecular weight heparin on mediator release by mast cells:preferential inhibition of cytokine production and mast cell dependent cutaneous inflammation. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1997;110:485–491. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4541471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P. Inflammatory mediators & asthma. Pharmacol. Rev. 1988;40:49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRETT K.E., METCALFE D.D. The histologic and functional characterization of enzymatically dispersed intestinal mast cells of nonhuman primates: effects of secretagogues and antiallergic drugs on histamine secretion. J. Immunol. 1985;135:2020–2026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAXTER J.H., ADAMIK R. Differences in requirements and actions of various histamine-releasing agents. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1978;27:497–503. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(78)90384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENYON R., ROBINSON C., CHURCH M.K. Differential release of histamine and eicosanoids from human skin mast cells activated by IgE-dependent and non-immunological stimuli. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989;97:898–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISSONNETTE E.Y., ENCISO J.A., BEFUS A.D. Inhibition of tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) release from mast cells by the anti-inflammatory drugs, sodium cromoglycate and nedocromil sodium. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1995;102:78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb06639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISSONNETTE E.Y., HOGABOAM C.M., WALLACE J.L., BEFUS A.D. Potentiation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated cytotoxicity of mast cells by their production of nitric oxide. J. Immunol. 1991;147:3060–3065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLOM N.G., HARVIMA I., KUSCHE-GULLBERG M., NILSSON K., HELLMAN L. Stem cell factor-dependent human cord blood derived mast cells express alpha-and beta-tryptase, heparin and chondroitin sulphate. Immunology. 1996;88:308–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.1996.tb00020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOWLER S.D., SMITH S.M., LAVERCOMBE P.S. Heparin inhibits the immediate response to antigen in the skin and lungs of allergic subjects. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1993;147:160–163. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.1.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADDING P., OKAYAMA Y., HOWARTH P.H., CHURCH M.K., HOLGATE S.T. Heterogeneity of human mast cells based on cytokine content. J. Immunol. 1995;155:297–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRITTIS P.A., CANNING D.R., SILVER J. Chondroitin sulfate as a regulator of neuronal patterning in the retina. Science. 1992;255:733–736. doi: 10.1126/science.1738848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROOKS A.C., WHELAN C.J., PURCELL W.M. Reactive oxygen species generation & histamine release by activated mast cells:modulation by nitric oxide synthase inhibition. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:585–590. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURTON A.F., ANDERSON F.H. Decreased incorporation of 14C-glucosamine relative to 3H-N-acetyl glucosamine in the intestinal mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1983;78:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARRAWAY R., COCHRANE D.E., LANSMAN J.B., LEEMAN S.E., PATERSON B.M., WELCH H.J. Neurotensin stimulates exocytotic histamine secretion from rat mast cells and elevates plasma histamine levels. J. Physiol. 1982;323:403–414. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHURCH M.K., LOWMAN M.A., REES P.H., BENYON R.C. Mast cells, neuropeptides and inflammation. Agents Actions. 1989;27:8–16. doi: 10.1007/BF02222185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHURCH M.K., PAO G.J., HOLGATE S.T. Characterization of histamine secretion from mechanically dispersed human lung mast cells: effects of anti-IgE, calcium ionophore A23187, compound 48/80, and basic polypeptides. J. Immunol. 1982;129:2116–2121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COCCHIARA R., BONGIOVANNI A., ALBEGGIANI G., AZZOLINA A., LAMPIASI N., DIBLASI F., GERACI D. Inhibitory effect of neuraminidase on SP-induced histamine release and TNF-α mRNA in rat mast cells. Evidence of a receptor-independent mechanism. J. Neuroimmunol. 1997;75:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COFFEY R.G. Comparison of circulating and peritoneal leukocyte cationic proteins in release of histamine from rat mast cells. Life Sci. 1973;13:1117–1130. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(73)90379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONTI P., REALE M., BARBACANE R.C., PANARA M.R., BONGRAZIO M., THEOHARIDES T.C. Role of lipoxins A4 &B4 in the generation of arachidonic acid metabolites by rat mast cells and their effect on [3H] serotonin release. Immunol. Lett. 1992;32:117–124. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(92)90103-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COUTTS S.M., NEHRING R.E., JARIWALA N.U. Purification of rat peritoneal mast cells: occupation of IgE receptors by IgE prevents loss of the receptors. J. Immunol. 1980;124:2309–2315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRISP A.J., CHAMPAN C.M., KIRKHAM S.E., SCHILLER A.L., KEANE S.M. Articular mastocytosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:845–851. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAHINDEN C.A., KURIMOTO J., BAGGIOLINI M., DEWALD B., WALZ A. Histamine and sulfidoleukotriene release from human basophils: Different effects of antigen, anti-IgE, C5a, f-Met-Leu-Phe and the novel neutrophil-activating peptide NAF1. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 1989;90:113–118. doi: 10.1159/000235011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRAGSTEDT C.A., WELLS J.A., ROCHA E SILVA M. Inhibitory effect of heparin upon histamine release by trypsin, antigen and proteose. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1942;51:191–192. [Google Scholar]

- ENERBÄCK L., BERGSTRÖM S. Effect of nedocromil sodium on the compound exocytosis of mast cells. Drugs. 1989;37 Supp. 1:44–50. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198900371-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERJAVEC F., LEMBECK F., FLORJANC-IRMAN T., SKOFITSCH G., DONNERER J., SARIA A., HOLZER P. Release of histamine by substance P. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1981;317:67–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00506259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEWTRELL C.M.S., FOREMAN J.C., JORDAN C.C., OEHME P., RENNER H., STEWART J.M. The effects of substance P on histamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine release in the rat. J. Physiol. 1982;330:393–411. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEWTRELL C.M., GOMPERTS B.D. Effect of flavone inhibitors of transport ATPases on histamine secretion from rat mast cells. Nature. 1977;265:635–636. doi: 10.1038/265635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISCHER M.J.E., PAULUSSEN J.J.C., HORBACH D.A., ROELOFSEN E.P.W., VAN MILTENBURG J.C., DE MOL N.J., JANSSEN L.H.M. Inhibition of mediator release in RBL-2H3 cells by some H1-antagonist derived anti-allergic drugs: relation to lipophilicity and membrane effects. Inflamm. Res. 1995;44:92–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01793220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOREMAN J.C. Neuropeptides and the pathogenesis of allergy. Allergy. 1987;42:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1987.tb02180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORSBERG E., PEJLER G., RINGVALL M., LUNDERIUS C., TOMASINI-JOHANSSON B., KUSCHE-GULLBERG M., ERIKSSON I., LEDIN J., HELLMAN L., KJELLEN L. Abnormal mast cells in mice deficient in a heparin-synthesizing enzyme. Nature. 1999;400:773–776. doi: 10.1038/23488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOX C.C., WOLF E.J., KAGEY-SOBOTKA A., LICHTENSTEIN L.M. Comparison of human lung and intestinal mast cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1988;81:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(88)90225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAGARI E., TSAI M., LANTZ C.S., FOX L.G., GALLI S.G. Differential release of mast cell interleukin-6 via c-kit. Blood. 1997;89:2654–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALLI S.J. New concepts about the mast cell. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;328:257–265. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOETZL E.J., CHERNOV T., RENOLD F., PAYAN D.G. Neuropeptide regulation of the expression of immediate hypersensitivity. J. Immunol. 1985;135:802s–805s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GORDON J.R., BURD P.R., GALLI S.J. Mast cells as a source of multifunctional cytokines. Immunol. Today. 1990;11:458–464. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90176-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRANERUS G., LÖNNQVIST B., ROUPE G. No relationship between histamine release measured as metabolite excretion in the urine, and serum levels of mast cell specific tryptase in mastocytosis. Agents Actions. 1994;41:C127–C128. doi: 10.1007/BF02007796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARDINGHAM T.E. Structure and biosynthesis of proteoglycans. Rheumatology. 1986;10:143–183. [Google Scholar]

- HEIMAN A.S., CREWS F.T. Inhibition of immunoglobulin but not polypeptide basestimulated release of histamine and arachidonic acid by anti-inflammatory steroids. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1984;230:175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERMAN B. Recent developments in monitoring calcium and protein interactions in cells using fluorescence lifetime microscopy. J. Fluorescence. 1997;7:85. [Google Scholar]

- HILL T.D., BERGGREN P.O., BOYNTON A.L. Heparin inhibits inositol-trisphosphate-induced calcium release from permeabilized rat liver cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1987;149:897–901. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90492-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUMPHRIES D.E., WONG G.W., FRIEND D.S., GURISH M.F., QUI W., HUANG C., SHARPE A.H., STEVENS R.L. Heparin is essential for the storage of specific granule proteases in mast cells. Nature. 1999;400:769–772. doi: 10.1038/23481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HURST R.E., ROY J.B., MIN K.W., VELTRI R.W., MARLEY G., PATTON K., SHACKFORD D.L., STEIN P., PARSONS C.L. A deficit of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans on the bladder urothelium in interstitial cystitis. Urology. 1996;48:817–821. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IANELLI C.J., DELELLIS R., THORLEY-LAWSON D.A. CD48 binds to heparin sulfate on the surface of epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:23367–23375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISERSKY C., METZGER H., BUELL D.N. Cell cycle-associated changes in receptors for IgE during growth and differentiation of a rat basophilic leukemia cell line. J. Exp. Med. 1975;141:1147–1162. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.5.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON H.G. New anti-allergy drugs–the lodoxamides. Trends in Pharmacol. Sci. 1980. pp. 343–345.

- JUNE C.H., RABINOVITCH P.S. Intracellular ionized calcium. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;41:149–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAN M., WANG F., XU J., CRABB J.W., HOU J., MCKEEHAN W.L. An essential heparin-binding domain in the fibroblast growth factor receptor kinase. Science. 1993;259:1918–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.8456318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEMPURAJ D., SAITO H., KANEKO A., FUKAGAWA K., NAKAYAMA M., TORU H., TOMIKAWA M., TACHIMOTO H., EBISAWA M., AKASAWA A., MIYAGI T., KIMURA H., NAKAJIMA T., TSUJI K., NAKAHATA T. Characterization of mast cell-committed progenitors present in human umbilical cord blood. Blood. 1999;93:3338–3346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KINOSHITA T., SAWAI N., HIDAKA E., YAMASHITA T., KOIKE K. Interleukin-6 directly modulates stem cell factor-dependent development of human mast cells derived from CD34+ cord blood cells. Blood. 1999;94:496–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOBAYASHI S., SOMLYO A.V., SOMLYO A.P. Heparin inhibits the inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate-dependent, but not the independent, calcium release induced by guanine nucleotide in vascular smooth muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988;153:625–631. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRILIS S.A., AUSTEN K.F., MACPHERSON J.L., NICODEMUS C.F., GURISH M.F., STEVENS R.L. Continuous release of secretory granule proteoglycans from a strain derived from the bone marrow of a patient with diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis. Blood. 1992;79:144–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUNA P., REDDIGARI S.R., KORNFELD D., KAPLAN A.P. Il-8 inhibits histamine release from human basophils induced by histamine-releasing factors, connective tissue activating peptide III and IL-3. J. Immunol. 1991;147:1020–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEAL-BERUMEN I., CONLON P., MARSHALL J.S. IL-6 production by rat peritoneal mast cells is not necessarily preceded by histamine release and can be induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 1994;152:5468–5476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LETOURNEUR D., CALEB B.L., CASTELLOT J.J., JR Heparin binding, internalization, and metabolism in vascular smooth muscle cells: I. Upregulation of heparin binding correlates with antiproliferative activity. J. Cell. Physiol. 1995b;165:676–686. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041650327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LETOURNEUR D., CALEB B.L., CASTELLOT J.J., JR Heparin binding, internalization, and metabolism in vascular smooth muscle cells: II. Degradation and secretion in sensitive and resistant cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1995a;165:687–695. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041650328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVI-SCHAFFER F., SHALIT M. Differential release of histamine and prostaglandin D2 in rat peritoneal mast cells activated with peptides. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 1989;90:352–357. doi: 10.1159/000235052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEWIS R.A., AUSTEN K.F. Nonrespitory functions of pulmonary cells: the mast cell. Fed. Proc. 1977;36:2676–2683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN T.J., BEFUS A.D. Differential regulation of mast cell function by IL-10 and stem cell factor. J. Immunol. 1997;159:4015–4023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDAHL U., HOOK M. Glycosaminoglycans and their binding to biological macromolecules. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1978;47:385–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWMAN M.A., BENYON R.C., CHURCH M.K. Characterization of neuropeptide-induced histamine release from human dispersed skin mast cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988a;95:121–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb16555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWMAN M.A., REES P.H., BENYON R.C., CHURCH M.K. Human mast cell heterogeneity: histamine release from mast cells dispersed from skin, lung, adenoids, tonsils, and colon in response to IgE-dependent and nonimmunologic stimuli. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1988b;81:590–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUCIO J., D'BROT J., GUO C.B., ABRAHAM W.M., LICHTENSTEIN L.M., KAGEY-SOBOTKA A., AHMED T. Immunologic mast cell mediated responses and histamine release are attenuated by heparin. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992;73:1093–1101. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.3.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARQUARDT D.L., ALONGI J.L., WALKER L.L. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor wortmannin blocks mast cell exocytosis but not IL-6 production. J. Immunol. 1996;156:1942–1945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARQUARDT D.L., WASSERMAN S.I. Modulation of rat serosal mast cell biochemistry by in vivo dexamethasone administration. J. Immunol. 1983;131:934–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSHALL J.S., LEAL-BERUMEN I., NIELSEN L., GLIBETIC M., JORDANA M. Interleukin (IL)-10 inhibits long-term IL-6 production but not preformed mediator release from rat peritoneal mast cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:1122–1128. doi: 10.1172/JCI118506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUDA K., NIITSUMA A., UCHIDA M.K., SUZUKI-NISHIMURA T. Inhibitory effects of sialic acid- or N-Acetylglucosamine-specific lectins on histamine release induced by compound 48/80, bradykinin and a polyethylenimine in rat peritoneal mast cells. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1994;64:1–8. doi: 10.1254/jjp.64.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCALINDON T.E., LA VALLEY M.P., GULIN J.P., FELSON D.T. Glucosamine and chondroitin for treatment of osteoarthritis. A systematic quality assessment and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assn. 2000;283:1469–1475. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.11.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- METCALFE D.D., BLAND C.E., WASSERMAN S.I. Biochemical and functional characterization of proteoglycans isolated from basophils of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. J. Immunol. 1984;132:1943–1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- METZLER B., XU Q. The role of mast cells in atherosclerosis. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1997;114:10–14. doi: 10.1159/000237636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONCK J.R., OBERHAUSER A.F., KEATING T.J., FERNANDEZ J.M. Thin-section ratiometric Ca2+ images obtained by optical sectioning of fura-2 loaded mast cells. J. Cell Biol. 1992;116:745–759. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.3.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOUSLI M., BRONNER C., LANDRY Y., BOCKAERT J., ROUOT B. Direct activation of GTP-binding regulatory proteins (G-proteins) by substance P and compound 48/80. FEBS Lett. 1990;259:260–262. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80023-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOUSLI M., BRONNER C., BUEB J.-L., GIES J-P., LANDRY Y. Activation of rat peritoneal mast cells by substance P and mastoparan. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 1989;250:329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELSON R.M., CECCONI O., ROBERTS W.G., ARUFFO A., LINHARDT J., BEVILACQUA M.P. Heparin oligosaccharides bind L and P-selectin and inhibit acute inflammation. Blood. 1993;82:3253–3258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEMETH A., MAGYAR P., HERCEG R., HUSZTI Z. Potassium-induced histamine release from mast cells and its inhibition by ketotifen. Agents Actions. 1987;20:149–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02074654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NURCOMBE V., FORD M.D., WILDSCHUT J.A., BARTLETT P.F. Development regulation of neural response to FGF-1 and FGF-2 by heparin sulfate proteoglycan. Science. 1993;260:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.7682010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKAYAMA Y., BENYON R.C., REES P.H., LOWMAN M.A., HILLIER K., CHURCH M.K. Inhibition profiles of sodium cromoglycate and nedocromil sodium on mediator release from mast cells of human skin, lung, tonsil, adenoid and intestine. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 1992;22:401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1992.tb03102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORENSTEIN N.S., GALLI S.J., DVORAK A.M., SILBERT J.E., DVORAK H.F. Sulfated glycosaminoglycans of guinea pig basophilic leukocytes. J. Immunol. 1978;121:586–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORR T.S., HALL D.E., GWILLIAM J.N., COX J.S. The effect of disodium cromoglycate on the release of histamine and degranulation of rat mast cells induced by compound 48/80. Life Sci. 1971;10:805–812. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(71)90035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEARCE F.L., BEFUS A.D., GAULDIE J., BIENENSTOCK J. Mucosal mast cells. II: Effects of anti-allergic compounds on histamine secretion by isolated intestinal mast cells. J. Immunol. 1982;128:2481–2486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PENNER R., MATTHEWS G., NEHER E. Regulation of calcium influx by second messengers in rat mast cells. Nature. 1988;334:499–504. doi: 10.1038/334499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIOTROWSKI W., FOREMAN J.C. On the actions of substance P, somatostatin and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide on rat peritoneal mast cells and in human skin. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1985;331:364–368. doi: 10.1007/BF00500821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIPKORN U., KARLSSON G., ENERBÄCK L. Phenotypic expression of proteoglycan in mast cells of the human nasal mucosa. Histochem. J. 1988;20:519–525. doi: 10.1007/BF01002650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAZIN E., MENCIA-HUERTA J., STEVENS R.L., LEWIS R.A., LIU F., COREY E., AUSTEN K.F. IgE-mediated release of leukotriene C4, chondroitin sulfate E proteoglycan, beta-hexosaminidase, and histamine from cultured bone marrow-derived mouse mast cells. J. Exp. Med. 1983;157:189–201. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.1.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REILLY K.M., DAWES J., YAP P.L., BARNETSON R.S., MACGREGOR I.R. Release of highly-sulphated glycosaminoglycans and histamine from human basophils. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 1988;86:261–266. doi: 10.1159/000234583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBIN J., SELDIN D.C., AUSTEN K.F., LEWIS R.A. Regulation of mediator release from mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells by glucocorticoids. J. Immunol. 1985;135:2719–2726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROZNIECKI J.J., LETOURNEAU R., SUGIULTZOGLU M., SPANOS C., GORBACH J., THEOHARIDES T.C. Differential effect of histamine-3 receptor active agents on brain but not peritoneal mast cell activation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;290:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAITO H., UZMAN B.G. Uptake of chondroitin sulfate by mammalian cells in tissue culture. Exp. Cell Res. 1971a;60:301–305. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(70)90519-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAITO H., UZMAN B.G. Uptake of chondroitin sulfate by mammalian cells in culture. II. Kinetics of uptake and autoradiography. Exp. Cell Res. 1971b;66:90–96. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(71)80015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAITO H., UZMAN B.G. Uptake of chondroitin sulfate by mammalian cells in culture. III. Effect of incubation media, metabolic inhibitors and structural analogs. Exp. Cell Res. 1971c;66:97–103. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(71)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHEENEN W.J.J.M., HOFER A.M., POZZAN T. Intracellular measurement of calcium using fluorescent probes. Cell Biology. 1998;3:363–374. [Google Scholar]

- SCHWARTZ L.B. Mediators of human mast cells and human mast cell subsets. Ann. Allergy. 1987;58:226–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SELDIN D.C., ADELMAN S., AUSTEN K.F., STEVENS R.L., HEIN A., CAULFIELD J.P., WOODBURY R.G. Homology of the rat basophilic leukemia cell and the rat mucosal mast cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985a;82:3871–3875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.11.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SELDIN D.C., AUSTEN K.F., STEVENS R.L. Purification and characterization of proteaseresistant secretory granule proteoglycans containing chondroitin sulfate di-B and heparin-like glycosaminoglycans from rat basophilic leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1985b;260:11131–11139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHANAHAN F., DENBURG J.A., FOX J., BIENENSTOCK J., BEFUS D. Mast cell heterogeneity: effects of neuroenteric peptides on histamine release. J. Immunol. 1985;135:1331–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHUTE J.K., PARMAR J., HOLGATE S.T., HOWARTH P.H. Urinary glycosaminoglycan levels are increased in acute severe asthma-a role for eosinophil-derived gelatinase B. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1997;113:366–367. doi: 10.1159/000237604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHUTE N.Aching for an arthritis cure U.S. News & World Report 199763–64.(Abstract)

- STEAD R.H., BIENENSTOCK J. Cell to Cell Interaction. Basel: Karger; 1990. Cellular interactions between the immune and peripheral nervous system. A normal role for mast cells; pp. eds Burger, M.M., Sordat, B. & Zinkernagel, R.M. pppp. 170–187. [Google Scholar]

- TASAKA K., MIO M., OKAMOTO M. Intracellular calcium release induced by histamine releasers and its inhibition by some antiallergic drugs. Ann. Allergy. 1986;56:464–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THEOHARIDES T.C. Mast cells: the immune gate to the brain. Life Sci. 1990;46:607–617. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90129-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THEOHARIDES T.C. Mast cell: a neuroimmunoendocrine master player. Int. J. Tissue React. 1996;18:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THEOHARIDES T.C., DOUGLAS W.W. Somatostatin induces histamine secretion from rat peritoneal mast cells. Endocrinology. 1978;102:1637–1640. doi: 10.1210/endo-102-5-1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THEOHARIDES T.C., BONDY P.K., TSAKALOS N.D., ASKENASE P.W. Differential release of serotonin and histamine from mast cells. Nature. 1982;297:229–231. doi: 10.1038/297229a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THEOHARIDES T.C., BOUCHER W. Sulphated polysaccharides inhibit mast cell (MC) secretion and may be useful in bone inflammation. FASEB J. 1999;13:A149. [Google Scholar]

- THEOHARIDES T.C., KOPS S.K., BONDY P.K., ASKENASE P.W. Differential release of serotonin without comparable histamine under diverse conditions in the rat mast cell. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1985;34:1389–1398. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90675-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THEOHARIDES T.C., PANG X., LETOURNEAU R., SANT G.R. Interstitial cystitis: a neuroimmunoendocrine disorder. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1998;840:619–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THEOHARIDES T.C., SIEGHART W., GREENGARD P., DOUGLAS W.W. Antiallergic drug cromolyn may inhibit histamine secretion by regulating phosphorylation of a mast cell protein. Science. 1980;207:80–82. doi: 10.1126/science.6153130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRNOVSKY J., LETOURNEAU R., HAGGAG E., BOUCHER W., THEOHARIDES T.C. Quercetin-induced expression of rat mast cell protease II and accumulation of secretory granules in rat basophilic leukemia cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1993;46:2315–2326. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90623-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN HAASTER C.M.C.J., ENGELS W., LEMMENS P.J.M.R., HORNSTRA G., VAN DER VUSSE G.J., HEEMSKERK J.W.M. Differential release of histamine and prostaglandin D2 in rat peritoneal mast cells; roles of cytosolic calcium and protein tyrosine kinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1265:79–88. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)00210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN LOVEREN H., KOPS S.K., ASKENASE P.W. Different mechanisms of release of vasoactive amines by mast cells occur in T cell-dependent compared to IgE-dependent cutaneous hypersensitivity responses. Eur. J. Immunol. 1984;14:40–47. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830140108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALSH L.J., TRINCHIERI G., WALDORF H.A., WHITAKER D., MURPHY G.F. Human dermal mast cells contain and release tumor necrosis factor α, which induces endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:4220–4224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WASSERMAN S.I. The mast cell and synovial inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:841–844. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WESTON A.P., BIDDLE W.L., BHATIA P.S., MINER P.B., JR Terminal ileal mucosal mast cells in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1993;38:1590–1595. doi: 10.1007/BF01303164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZEHNDER J.L., GALLI S.J. Mast-cell heparin demystified. Nature. 1999;400:714–715. doi: 10.1038/23360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]