Abstract

S-Nitrosothiols are nitric oxide (NO) donor drugs that have been shown to inhibit platelet aggregation in platelet rich plasma (PRP) in vitro and to inhibit platelet activation in vivo. The aim of this study was to compare the platelet effects of a novel S-nitrosated glyco-amino acid, RIG200, with an established S-nitrosothiol, S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) in PRP, and to investigate the effects of cell-free haemoglobin and red blood cells on S-nitrosothiol-mediated inhibition of platelet aggregation.

The effects of GSNO and RIG200 in collagen (2.5 μg ml−1)-induced platelet aggregation in PRP and whole blood were investigated in vitro. Both compounds were found to be powerful inhibitors of aggregation in PRP, and RIG200 was significantly more potent (IC50=2.0 μM for GSNO and 0.8 μM for RIG200; P=0.04).

Neither compound inhibited aggregation in whole blood, even at concentrations of 100 μM. Red blood cell concentrations as low as 1% of the haematocrit, and cell-free haemoglobin (⩾2.5 μM), significantly reduced their inhibitory effects on platelets.

Experiments involving measurement of cyclic GMP levels, electrochemical detection of NO and electron paramagnetic resonance of haemoglobin in red blood cells, indicated that scavenging of NO generated from S-nitrosothiols by haemoglobin was responsible for the lack of effect of S-nitrosothiols on platelets in whole blood.

These studies suggest that scavenging of NO by haemoglobin in blood might limit the therapeutic application of S-nitrosothiols as anti-platelet agents.

Keywords: Nitric oxide, platelet aggregation, thrombosis, haemoglobin, S-nitrosothiols, RIG200

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) inhibits platelet aggregation (Radomski et al., 1987a,1987b) and adhesion to vascular endothelium (Radomski et al., 1987c,1987d). Although the vasodilator properties of NO donor drugs like organic nitrates have long been exploited in the management of ischaemic heart disease, it remains unclear whether these drugs also inhibit platelet aggregation at therapeutic concentrations (Booth et al., 1997; Mehta & Mehta, 1980; Stamler & Loscalzo, 1991).

S-Nitrosothiols are NO donor drugs that, unlike organic nitrates, do not engender vascular tolerance (Bauer & Fung, 1991; Miller et al., 2000). S-Nitrosoglutathione (GSNO; Figure 1a) is an endogenous S-nitrosothiol (Gaston et al., 1993; 1994) that inhibits platelet aggregation at sub-threshold concentrations for vasodilation (De Belder et al., 1994) via both guanylate cyclase dependent (Radomski et al., 1992) and independent pathways (Gordge et al., 1998). Platelet effects in vivo have been confirmed with studies in women with pre-eclampsia (Lees et al., 1996), in patients with acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina (Langford et al., 1996), and following percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA; Langford et al., 1994). However, GSNO is ineffective in inhibiting platelet activation during cardiopulmonary bypass (Langford et al., 1997). Formation of protein and low molecular weight S-nitrosothiols like GSNO (Daniel et al., 1993), has been implicated as a pre-requisite for inhibition of platelet activation by inhaled NO (Gries et al., 1998).

Figure 1.

Structural formulae and full generic names for (a) GSNO and (b) RIG200.

To date, in vitro platelet studies involving NO donors have not addressed the issue of the potential inhibitory effect of haemoglobin (Hb) in the blood. Ferrohaemoglobin (HbFe(II)) is a powerful NO scavenger (Martin et al., 1985) and is often used experimentally to inhibit NO-mediated vasodilatation (Martin et al., 1985; Flitney et al., 1992; 1996; Megson et al., 1997). Cell-free HbFe(II) abolishes the anti-platelet effects of GSNO, thus identifying NO as the mediator (Radomski et al., 1992). Hb in red blood cells (RBCs) might, therefore, also be expected to influence NO-mediated inhibition of platelet aggregation. Indeed, inhibition of platelet aggregation by endothelium-derived NO is reversed by RBCs in vitro (Houston et al., 1990). Recent evidence suggests that Hb can interact with NO in a variety of ways, depending on the oxidation state of the haem iron. Hb might represent a complex NO transporter, binding NO in areas where HbFe(II) is oxygenated, and releasing it during arterio-venous transit (Jia et al., 1996; Gow & Stamler, 1998). S-Nitrosated met-Hb (the Fe(III) form of Hb) has even been shown to inhibit platelet aggregation in platelet rich plasma (PRP) in vitro (Pawloski et al., 1998). The role of Hb in NO function is highly controversial, with a number of recent studies questioning the importance of S-NOHb as a transport mechanism for NO (Liao et al., 1999; Wolz et al., 1999).

Here, we investigated the anti-platelet effects of a novel S-nitrosated glyco-amino acid (RIG200; Figure 1b). RIG200 is considerably more stable than the parent compound, S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP; Megson et al., 1997) and S-nitrosocysteine, and causes prolonged vasodilatation in endothelium-denuded rat femoral arteries (Megson et al., 1997) and in human bypass graft veins (Sogo et al., 2000). Experiments were performed to determine whether the anti-platelet effects seen with RIG200 and GSNO in PRP are reproduced in whole blood and to establish the influence of RBCs, and the Hb they contain, on the fate of NO generated from S-nitrosothiols. This information is critical in determining the therapeutic potential of these compounds as anti-platelet agents.

Methods

Subjects

Venous blood samples (40 ml) were taken from healthy male volunteers aged 20–30 years (n=8). Volunteers were non-smokers, had not taken aspirin or ibuprofen during the previous 10 days, or any other medication during the previous 48 h, and were fasted for 12 h prior to sampling. Each volunteer returned for six visits at least 1 week apart.

Samples

Blood samples were taken using a 19-gauge needle into 10 ml evacuated Monovette™ tubes containing 0.8 ml sodium citrate (3.8%), and gently mixed. Tubes for whole blood (WB) experiments were stored at room temperature. Blood for PRP experiments was centrifuged at 120×g for 10 min and PRP aspirated and stored at room temperature prior to aggregation. Platelet-poor plasma (PPP) was derived from blood that was centrifuged at 1000×g for 15 min. In experiments requiring washed RBCs, a sample (1 ml) of packed RBCs was taken from the lower layer, taking care to avoid the ‘buffy coat' containing monocytes and other white blood cells. Samples were then ‘washed' with an equal volume of sterile saline (0.9%) and centrifuged again at 1000×g for a further 15 min. The saline was then aspirated, leaving a layer of packed RBCs.

Blood counts (Coulter Ac.T 8 Haematology Analyser, Coulter Electronics, Luton, U.K.) were carried out on samples to determine the number of RBCs and platelets, and the Hb concentration. RBC counts for all volunteers were between 4.25–4.50×1012 l−1 and platelet counts were 1.50–2.75×1011 l−1. PRP derived from samples contained <0.01×1012 l−1 RBCs and 2.75–4.00×1011 l−1 platelets.

Platelet aggregation

Half-millilitre samples of PRP and WB were diluted with 0.5 ml of 0.9% sterile saline and pre-warmed to 37°C for 5 min in a two-channel platelet aggregometer (Chronolog Ca560, Labmedics, Stockport, U.K.) capable of measuring aggregation in PRP and WB by an impedance method.

Diluted samples of PRP and WB were stirred at 1000 r.p.m. using disposable stirrer bars and platelets were activated with a supramaximal concentration of collagen (2.5 μg ml−1). Samples were treated 1 min prior to collagen with 10 μl of saline (control) or concentrations of either GSNO or RIG200 to give final drug concentrations in cuvettes of 0.3–100 μM and an IC50 concentration of aspirin (10 μM), as determined by pilot experiments (n=3). The concentration used is slightly lower than that reported previously for aspirin in vitro (∼45 μM; Dohi et al., 1993), perhaps because of differences in the population from which blood was derived. Aspirin experiments were used to determine whether RBCs could influence NO-independent inhibition of platelet aggregation. Aggregation was measured by an impedance method using an electrode immersed in the sample. The signal from the aggregometer was processed by an analogue-digital converter (MacLab 4e; AD Instruments, Sussex, U.K.) and displayed on a microcomputer (Macintosh LC III) using Chart™ software (AD Instruments). Change in impedance recorded 10 min after addition of collagen was used as a measure of the extent of aggregation.

In separate experiments, diluted PRP samples were treated with 10 μM GSNO or RIG200 (∼IC80) in the presence of washed RBCs (100, 10, 1 or 0.1% of WB haematocrit; n=6 for each). Samples of diluted RBCs were centrifuged (1000×g) and the supernatant assayed in the Coulter counter to assess cell-free Hb due to haemolysis. Alternatively, drug exposures were carried out in the presence of human ferrohaemoglobin (HbFe(II); 250, 25 or 2.5 μM, chosen to approximate Hb concentrations in 10, 1 and 0.1% WB, as determined from blood counts). In both cases, RBCs or HbFe(II) were added to PRP immediately prior to NO donor drug exposure. Again, samples were treated with NO donors 1 min prior to collagen addition (2.5 μg ml−1).

NO electrode measurements

One-millilitre samples of PPP or PRP were diluted with 1 ml of sterile saline (0.9%) and incubated at 37°C in the aggregometer, as for the aggregation studies described above. An isolated NO electrode (World Precision Instruments, Stevenage, Hertfordshire, U.K.), calibrated using sodium nitrite solutions (10–1000 nM) in saline acidified with ascorbic acid (10 mM) at 37°C, was introduced into the cuvette in place of the impedance electrode and allowed to stabilize (10–30 min). The signal from the NO electrode was processed and displayed using the same microcomputer system detailed above for aggregation studies. Once stable, GSNO or RIG200 (20 μl) was added to the PPP or PRP using a microsyringe to give a final concentration of 10−5 M. Drug solutions and the microsyringe were pre-warmed (37°C) to minimize temperature artefacts.

Cyclic GMP measurements

Whole blood (10 ml) was collected in trisodium citrate evacuated tubes and centrifuged at 120×g for 10 min to obtain PRP. Platelets were counted in PRP samples (Coulter AcT8, Beckman Coulter, U.K.) and five 250 μl aliquots were diluted with 240 μl of sterile saline. Aliquots were then pre-warmed to 37°C in the aggregometer pre-warming wells. Thereafter, two aliquots were treated with HbFe(II) (2.5 μM final concentration) and then with either GSNO (10 μM final concentration, two tubes) or RIG200 (10 μM, two tubes). The remaining aliquots were treated with equivalent concentrations of GSNO or RIG200 or with an equal volume of saline (5 μl; control), all in the absence of Hb. The concentrations of S-nitrosothiols chosen were known to give ∼80% inhibition of platelet aggregation. Collagen (2.5 μg ml−1) was then added to all five aliquots to mimic experimental conditions and, following a 5-min incubation, trichloroacetic acid (TCA; 10%; 300 μl) was added to the PRP to precipitate proteins and aliquots were centrifuged (20,000×g for 10 min at 4°C). The supernatant was decanted and frozen at −80°C prior to cyclic GMP immunoassay (low pH; R & D Systems, Abingdon, U.K.). Results were expressed as pmol 108 platelets−1.

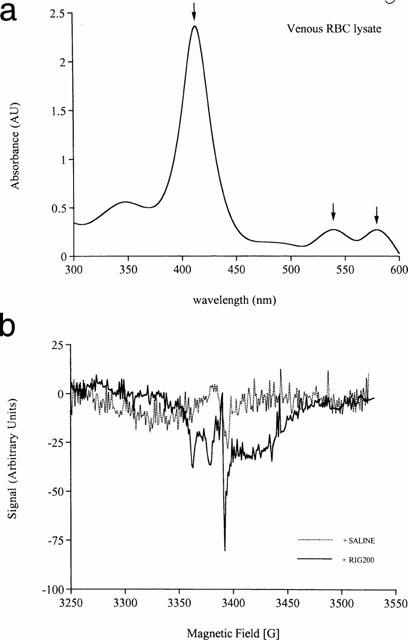

Electron paramagenetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy

Spectrometric analysis similar to that used previously was not sufficiently sensitive to detect nitrosation of either cysteine residues (414 nm) or haem iron (560 nm) on account of the low ratio of S-nitrosothiol to Hb (1 : 10 compared to 1 : 1 detection limit in previous studies; Jia et al., 1996). Ultraviolet/visible (u.v./vis) spectroscopy was nevertheless carried out on Hb from washed, lysed RBCs from fresh venous blood to confirm its oxygenation status (absorption peaks at λ=∼530 and 575 nm).

EPR was used to detect nitrosylation of haem iron. RBC suspensions in plasma containing 100% of the haematocrit were incubated with GSNO or RIG200 (both 100 μM) for 30 min at 37°C and immediately snap-frozen on dry ice for EPR studies that were carried out within 4 h of S-nitrosothiol incubation. EPR spectra were run on ∼200 μl samples in 4 mm diameter quartz tubes on a Bruker instrument (EMX 10/12 EPR X-band spectrometer) under the following conditions: Temperature=102K; microwave power and frequency=10 mW, 9.52 GHz; receiver gain=1×106; modulation=2 Gauss peak-to-peak (Gpp). Spectra between 3235 and 3530 Gauss (G) magnetic field were recorded, generally as the sum of eight scans. Nitrosylation of Hb iron was expected to result in a triplet of peaks at ∼3350–3400 G.

Drugs

GSNO was purchased from Sigma Ltd (Poole, Dorset, U.K.). RIG200 was synthesized using a published method (Megson et al., 1997). Collagen was purchased from Labmedics (Stockport, U.K.) and all other compounds were purchased from Sigma Ltd. Human Met-Hb was reduced to the ferro(FeII)-form by sodium hydrosulphite, which was then removed by dialysis. Hb aliquots were frozen (−80°C) and used within 2 weeks (Martin et al., 1985).

Statistical analysis

Repeated measures, 2-factor ANOVAs, paired and unpaired Student's t-tests and one-factor ANOVAs followed by post hoc Bonferroni analyses were carried out where appropriate. Tests used for each data set are stated in the text and a P value of <0.05 was accepted as significant. Experimental data are expressed as mean±s.e.mean in the text.

Results

Aggregometry

Effect of RBCs on S-nitrosothiol-mediated inhibition of platelet aggregation

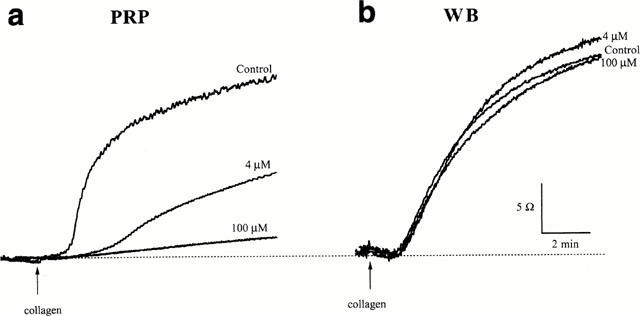

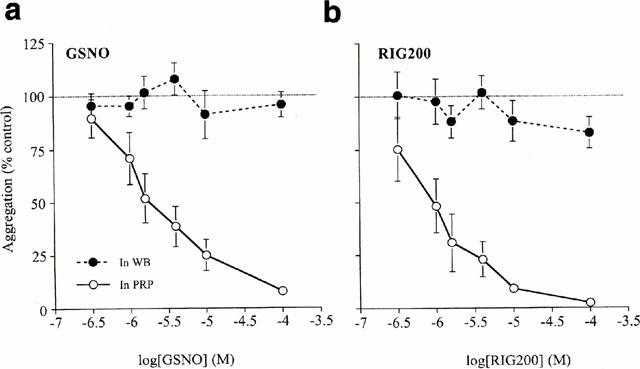

Collagen-induced aggregation in PRP was inhibited by GSNO (Figures 2a and 3a; IC50=2.0±1.3; n=8) and RIG200 (Figure 3b; IC50=0.8±0.3; n=8). RIG200 was a significantly more effective inhibitor of platelet aggregation than GSNO (P=0.04, paired Student's t-test).

Figure 2.

Recordings from platelet aggregation studies in (a) platelet rich plasma (PRP) and (b) whole blood (WB) from the same subject. In each case, traces from saline-treated controls, and PRP or WB treated with GSNO (4 and 100 μM) are shown. Collagen (2.5 μg ml−1) was added at the point indicated.

Figure 3.

Concentration-response curves for inhibition of platelet aggregation by (a) S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) and (b) the S-nitrosated glyco-amino acid, RIG200, in platelet rich plasma (PRP; IC50=2.0±1.3 and 0.8±0.3 μM respectively) and in whole blood (WB). RIG200 was significantly more effective than GSNO (P=0.04; paired Student's t-test, n=8). Inhibition of platelet aggregation was prevented in WB (P<0.001 for both GSNO and RIG200; 2-factor, repeated measures ANOVA, n=8).

Equivalent experiments carried out in WB from the same volunteers (Figures 2b and 3a,>b; n=8) showed that GSNO and RIG200-induced inhibition of aggregation was significantly inhibited (P<0.001 for GSNO; P<0.001 for RIG200 compared to PRP results; 2-factor, repeated dose ANOVA). The inhibitory effect of IC50 concentrations of aspirin (10 μM) were not significantly different in PRP (61.2±13.8% of collagen-induced aggregation) compared to WB (51.7±13.4%; P=0.65; paired Student's t-test; n=8).

Comparison of RBCs and cell-free HbFe(II) on S-nitrosothiol-mediated inhibition of aggregation

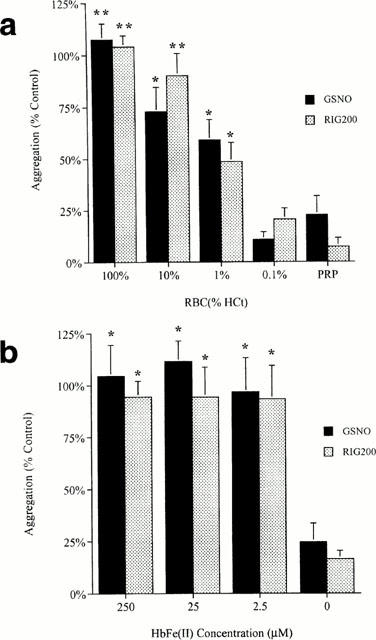

S-Nitrosothiol-induced inhibition of platelet aggregation in PRP was abolished in the presence of RBCs (100% of the haematocrit, n=6; Figure 4a). The effect was dependent on the RBC concentration; RBCs at 0.1% of the haematocrit were incapable of significantly altering inhibition of aggregation by either GSNO (P=0.33, Bonferroni post hoc test following a one-factor ANOVA) or RIG200 (P=0.08). Cell-free Hb in all RBC dilutions was below the level of detection of the Coulter counter (<0.5 μM). HbFe(II) concentrations of 250, 25 and 2.5 μM, equating to Hb concentrations in RBCs at 10, 1 and 0.1% of the haematocrit, all abolished S-nitrosothiol-induced inhibition of aggregation in PRP (Figure 4b, n=6; P<0.05 for each HbFe(II) concentration compared to PRP).

Figure 4.

Effect of (a) red blood cells (RBCs) and (b) cell-free haemoglobin (HbFe(II)) on S-nitrosothiol-mediated inhibition of aggregation. RBCs were reconstituted in platelet rich plasma (PRP) to 100, 10, 1 and 0.1% of the haematocrit for WB. A one-factor ANOVA indicated a significant difference between aggregation with different RBC concentrations (P<0.001, n=6). The results of post-hoc Bonferroni analyses between aggregation in PRP against each of the RBC concentrations are indicated on the graph: *P<0.05, **P<0.01. A similar one-factor ANOVA was carried out on the data presented in (b) (P<0.001, n=6), and the results of Bonferroni post-hoc analyses are indicated on the graph.

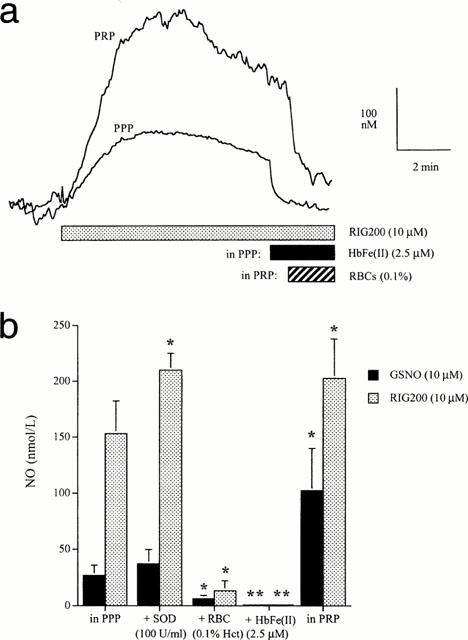

NO electrode

NO generation from GSNO and RIG200 in PPP and PRP was confirmed using an isolated NO electrode (Figure 5a). RIG200 generated significantly more NO than GSNO (Figure 5b; P=0.01, paired Student's t-test), and NO measured from RIG200 was enhanced by SOD (100 u ml−1; P=0.03), abolished by Hb (2.5 μM; Figure 4, P<0.01 for both S-nitrosothiols, n=5) and significantly reduced by 0.1% RBCs (P=0.03). Interestingly, NO generated from both compounds was greater in the presence of platelets (PRP) than in PPP (Figure 5a,b; P=0.04 for GSNO and P=0.03, Bonferroni post hoc tests).

Figure 5.

(a) Recordings from a nitric oxide (NO) electrode showing the concentration of NO detected in platelet rich plasma (PRP) and platelet poor plasma (PPP) on addition of RIG200 (10 μM). NO was rapidly scavenged by haemoglobin (HbFe(II)) in PPP and by 0.1% red blood cells (RBCs). However, NO was still detectable in the presence of RBCs at this concentration. (b) The effect of superoxide dismutase (SOD; 100 U ml−1), RBCs (0.1%) and Hb (2.5 μM) on NO measured in PPP. NO measured in PRP is also shown. *P<0.05, **P<0.01; Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, n=6).

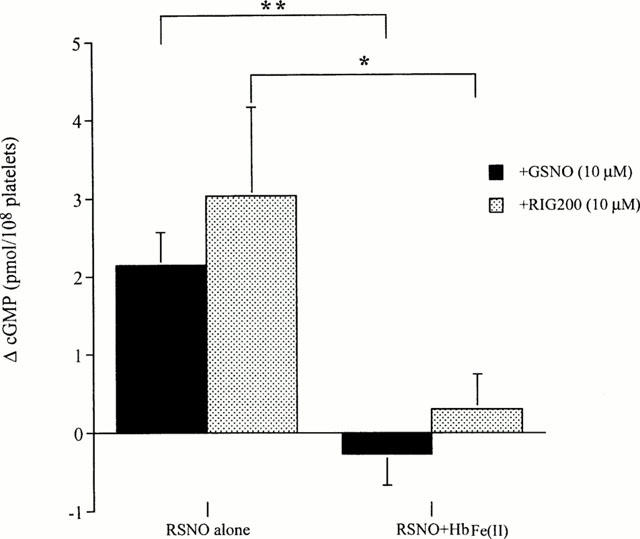

Cyclic GMP immunoassay

Cyclic GMP concentrations in saline-treated (control) PRP were 8.9±1.5 pmol 108 platelets−1 (n=5). Concentrations increased in platelets treated with 10 μM GSNO (+2.15±0.42 pmol 108 platelets−1) or RIG200 (+3.0±1.1 pmol 108 platelets−1) in the absence of Hb (Figure 6). There was no significant difference in the amount of cyclic GMP generated in the presence of GSNO compared to RIG200 (P=0.46; paired Student's t-test). Significantly less cyclic GMP was generated in the presence of Hb(Fe(II) (2.5 μM; P=0.001 for GSNO and 0.04 for RIG200, paired Student's t-test).

Figure 6.

Effect of S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) and the S-nitrosated glyco-amino acid, RIG200 (both 10 μM), on cyclic GMP concentrations measured in PRP. Results are expressed as the change (Δ) in cyclic GMP after a 5 min incubation at 37°C with S-nitrosothiols (RSNO) alone, or in the presence of haemoglobin (HbFe(II); 2.5 μM). Results in the presence and absence of HbFe(II) are compared for each S-nitrosothiol by a paired Student's t-test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, n=5.

Ultraviolet/visible (u.v./vis) and EPR spectroscopy

Spectrophotometric analysis of diluted Hb (5 μM) from lysed RBCs obtained from fresh venous blood samples indicated that Hb was at least partially oxygenated on account of absorption peaks at ∼530 and ∼575 nm (Figure 7a). Deoxy-HbFe(II) has a single absorption peak at ∼550 nm and the spectrum for HbFe(III) shows little absorption in this region. Incubation of RBCs with RIG200 or GSNO (100 μM; 30 min) caused a detectable change in the EPR signal at ∼3375 G, corresponding to nitrosylation of haem Fe(II) (Figure 7b). The characteristic three-line signal of αHbFe(II)NO (splitting constant of a(N)=16.5 G), superimposed on a broad ceruloplasmin signal (Kagan & Day, 1996), is apparent after treating WB for 30 min with RIG200 (10−4 M; Henry et al., 1991). There is no signal corresponding to βHbFe(II)NO, reinforcing previous data indicating that NO binds to α but not β subunits of Hb (Kagan & Day, 1996). The high field component of the triplet is partly obscured by a sharp singlet. The g-factor of this singlet (∼2.001) suggests that it is a carbon-centred radical, possibly derived from lipid or protein components of the RBCs.

Figure 7.

(a) Ultraviolet/visible spectrophotometric analysis of venous red blood cell (RBC) lysate (5 μM). The absorption peaks shown are at 415, 530 and 570 nm (arrowed). Changes in the 414 nm absorption peak caused by S-nitrosation were not detectable in these experiments after incubation with S-nitrosothiols (⩽100 μM). The two peaks at ∼530 and ∼570 nm are indicative of at least partial oxygenation of haemoglobin (HbFe(II)); deoxy HbFe(II) has a single, broad peak centered at ∼550 nm and HbFe(III) fails to absorb strongly in this region. (b) Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra for venous blood treated with saline (control) or the S-nitrosated glyco-amino acid (RIG200; 100 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. The RIG200 trace shows a characteristic triplet of peaks indicative of nitrosylation of α-subunit haem iron. Similar spectra were obtained with S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) under the same conditions (not shown). These signals were weak and were undetectable with lower concentrations of RIG200 and GSNO (10 μM), or with shorter incubation times (10 min).

Discussion

Our results show that two S-nitrosothiols, RIG200 and GSNO, are powerful inhibitors of platelet aggregation in PRP but fail to inhibit aggregation in WB. This is an important finding because, although it is known that RBCs abolish the antiplatelet effects of endothelium-derived NO (Houston et al., 1990), and that cell-free HbFe(II) inhibits the effect of S-nitrosothiols in platelets (Radomski et al, 1992), it was unknown whether the NO in S-nitrosothiols would be protected from scavenging by Hb in RBCs. Indeed, recent studies have shown that the S-nitrosothiol, S-nitrosocysteine, can nitrosate cysteine residues on so-called ‘tense' or ‘T-state' HbFe(III), but not ‘relaxed' or ‘R-state' oxy-HbFe(II), and that the resultant SNO-HbFe(III) subsequently releases NO that can inhibit platelet aggregation in vitro (Pawloski et al., 1998). Given that at least some of the Hb in the venous blood used in our experiments was in the T-state, potentially facilitating S-nitrosation by exogenous S-nitrosothiols (Pawloski et al., 1998), we tested the hypothesis that pharmacologically relevant S-nitrosothiol concentrations would cause sufficient S-nitrosation of Hb to inhibit platelet aggregation in mixed WB. In the event, this was not the case, with RBCs preventing S-nitrosothiol-mediated inhibition of platelet aggregation under these conditions. Furthermore, our experiments show that RBCs at a concentration of only 1% of the haematocrit can significantly attenuate the inhibitory effect of pharmacologically relevant concentrations of both GSNO and RIG200.

Net scavenging of NO by Hb in our experiments, as opposed to net release in previous studies, probably occurs because the concentration of NO available for Hb interaction was insufficient to generate enough S-nitrosated HbFe(III) to inhibit aggregation, even with 100 μM GSNO or RIG200; Hb in previous experiments was saturated with NO from S-nitrosocysteine (Pawloski et al., 1998). Furthermore, spectrophotometric analysis indicated that the Hb in RBCs from our venous samples was partly in the oxy-HbFe(II) and would be unlikely to release NO from any S-nitrosated cysteine residues (Pawloski et al., 1998), and EPR studies indicated that at least some of the NO scavenged by Hb in RBCs nitrosylated the haem iron of α, but not β, subunits. Our results do not, however, preclude the possibility that NO scavenged by Hb in RBCs in vivo could be released later, when the molecule undergoes autoxidation to HbFe(III).

Interestingly, cell-free HbFe(II) proved more effective at scavenging NO than RBCs containing an equivalent concentration of Hb, probably because of closer proximity of free HbFe(II) to platelet membranes, and the relatively slow rate at which NO crosses RBC membranes (diffusion coefficient=0.4×10−5 cm2 s−1; Denicola et al., 1996) compared to the rate of reaction with HbFe(II) (rate constant=2×105 M−1 s−1; Hakim et al., 1996). In addition, it has recently been proposed that RBCs possess an intrinsic barrier that limits NO consumption still further (Vaughn et al., 2000). It is possible that a proportion of the inhibitory effect seen with high concentrations of RBCs was caused by Hb released from cells through haemolysis. The concentration of cell-free Hb was found to be below our detection limit (<0.5 μM) but could, nevertheless, exaggerate inhibition by RBCs. The effect of confining Hb to cells might, therefore, be even more pronounced than we show here.

The inhibitory effects of the S-nitrosothiols in PRP were associated with increased concentrations of NO and of platelet cyclic GMP, and low concentrations of cell-free HbFe(II) were capable of preventing both inhibition of aggregation and cyclic GMP elevation in PRP, probably due to scavenging of NO. The amount of NO generated from both GSNO and RIG200 was greater in PRP than in PPP, indicative of a platelet-dependent mechanism that can accelerate S-nitrosothiol decomposition, as previously proposed (Radomski et al., 1992; Gordge et al., 1996).

These results have important implications for S-nitrosothiols as inhibitors of platelet aggregation in vivo. On the face of it, they might suggest that these compounds would be ineffective, and studies using GSNO in cardiopulmonary bypass support this conclusion (Langford et al., 1997). However, studies in women with pre-eclampsia and in patients following myocardial infarction indicate that GSNO can inhibit platelet activation, as indicated by reduced P-selectin and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa expression in vivo (Langford et al., 1996; Lees et al., 1996). Furthermore, it has been shown that inhaled NO can inhibit platelet activation in vivo by a mechanism that is likely to involve an S-nitrosothiol intermediate (Gries et al., 1998).

Perhaps the obvious contradiction in the data can be explained by the fact that blood is mixed in cardiopulmonary bypass whereas in the true in vivo situation, plasma streaming results in RBCs flowing through the centre of blood vessels, surrounded by PRP adjacent to the endothelium (Aarts et al., 1988). Separation of RBCs from platelets could facilitate NO-mediated platelet actions of both endothelium-derived NO and S-nitrosothiols under normal conditions in vivo. Recent modelling studies suggest that, whilst effectively scavenging NO in the centre of vessels, Hb in RBCs might have little influence over endothelium-derived NO in the peripheral zone (Butler et al., 1998). A potential added benefit of this dependency on plasma streaming is that during haemorrhage, mixing of RBCs with PRP could prevent S-nitrosothiol inhibition of aggregation, particularly if associated with haemolysis. Therefore, use of S-nitrosothiols as a preventative measure against thrombotic events may not carry the otherwise anticipated risk of haemorrhagic stroke (He et al., 1998). The apparent dependency of S-nitrosothiol activity in platelets on the separation of RBCs from platelets requires confirmation. Bleeding time experiments, where blood is likely to be mixed, could help to determine whether or not S-nitrosothiols retain anti-aggregating properties in mixed blood under physiological conditions.

It should be noted that, whilst plasma streaming is a characteristic of healthy blood vessels, laminar flow is disrupted by atherosclerotic plaques and thrombi. Mixing of red blood cells with platelets under those conditions is likely to limit the effect of endothelium-derived NO and prevent the anti-platelet activity of blood-borne S-nitrosothiols. However, RIG200 has selective effects in injured vessels, perhaps due to retention within the vessel wall in these areas (Megson et al., 1997). In this case, NO released from retained RIG200 might inhibit the platelet-vascular wall interaction and thrombus formation specifically in areas where the endothelium is damaged.

These potential benefits of S-nitrosothiols like RIG200 as anti-platelet drugs require further investigation. Powerful antiplatelet activity, in concert with other protective effects of S-nitrosothiol-derived NO, could confirm these compounds as viable alternatives to conventional treatments for thrombotic diseases.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from the British Heart Foundation (PG/98123), The Engineering & Physical Sciences Research Council, The Rollo Trust, The Sir Stanley & Lady Davidson Fund and The Urquhart Charitable Trust. Professor Webb is supported by a Research Leave Fellowship from the Wellcome Trust (WT 0526330). We also wish to thank the volunteers who provided repeated blood samples, and the clinicians who took the samples. Technical support and advice from Mr N. Johnson and Mr K. Magid was also much appreciated.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- cyclic GMP

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- EDRF

endothelium-derived relaxing factor

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- G

Gauss

- Gpp

Gauss peak-to-peak

- GSNO

S-nitrosoglutathione

- HbFe(II)

ferrohaemoglobin

- HbFe(III)

met-hamoglobin

- IC50

inhibitory concentration (50% max)

- NO

nitric oxide

- PPP

platelet poor plasma

- PRP

platelet rich plasma

- PTCA

percutaneous transluminal angioplasty

- RBC

red blood cell

- RIG200

N-(S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine)-2-amino-2-deoxy-1,3,4,6,-tetra-O-acetyl-β-D-glucopyranose

- UV/vis

ultraviolet/visible

- WB

whole blood

References

- AARTS P.A.M.M., VAN DEN BROEK S.A.T., PRINS G.W., SIXMA K.J.J., HEETHAAR R.M. Blood platelets are concentrated near the wall, and red blood cells in the center, in flowing blood. Arteriosclerosis. 1988;8:819–824. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.8.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAUER J.A., FUNG H.L. Differential hemodynamic effects and tolerance properties of nitroglycerin and an S-nitrosothiol in experimental heart failure. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;256:249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOOTH B.P., NOLAN T.D., FUNG H.-L. Nitroglycerin-inhibited whole blood aggregation is partially mediated by calcitonin gene-regulated peptide–a neurogenic mechanism. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:577–583. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUTLER A.R., MEGSON I.L., WRIGHT P.G. Diffusion of nitric oxide and scavenging by blood in the vasculature. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1425:168–176. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DANIEL I., STAMLER J.S., JARAKI O.J., KEANEY J.F., OSBORNE J.A., FRANCIS S.A., SINGEL D.J., LOSCALZO J. Antiplatelet properties of protein S-nitrosothiols derived from nitric oxide and endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Arterioscler. Thromb. 1993;13:791–799. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.6.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE BELDER A.J., MACALLISTER R., RADOMSKI M.W., MONCADA S. Effects of S-nitroso-glutathione in the human forearm circulation: evidence for selective inhibition of platelet activation. Cardiovasc. Res. 1994;28:691–694. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENICOLA A., SOUZA J.M., RADI R., LISSE E. Nitric oxide diffusion in membranes determined by fluorescence quenching. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996;328:208–212. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOHI M., SAKATA Y., SEKI J., NAMIKAWA Y., FUJISAKI J., TANAKA A., TAKASUGI H., MOTOYAMA Y., YOSHIDA K. The antiplatelet actions of FR122047, a novel cyclooxygenase inhibitor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;243:179–184. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90378-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLITNEY F.W., MEGSON I.L., FLITNEY D.E., BUTLER A.R. Iron-sulphur cluster nitrosyls, a novel class of nitric oxide generator: mechanism of vasodilator action on rat isolated tail artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;107:842–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLITNEY F.W., MEGSON I.L., THOMSON J.L.M., KENNOVIN G.D., BUTLER A.R. Vasodilator responses of rat isolated tail artery enhanced by oxygen-dependent, photochemical release of nitric oxide from iron-sulphur nitrosyls. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1549–1557. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GASTON B., DRAZON J.M., FACKLER J., RANDEV P., ARNELLE D., MULLINS M.E., SUGARBAKER D.J., CHEE C., SINGEL D.J., LOSCALZO J., STAMLER J.S. Endogenous nitrogen oxides and bronchodilator S-nitrosothiols in human airways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:10957–10961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GASTON B., DRAZON J.M., JANSEN A., SUGARBAKER D.A., LOSCALZO J., RICHARDS W., STAMLER J.S. Relaxation of human bronchial smooth muscle by S-nitrosothiols in vitro. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;268:978–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GORDGE M.P., HOTHERSALL J.S., NORONHA-DUTRA A.A. Evidence for a cyclic GMP-independent mechanism in the anti-platelet action of S-nitrosoglutathione. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:141–148. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GORDGE M.P., MEYER D.J., HOTHERSHALL J., NEILD G.H., PAYNE N.N., NORONHA-DUTRA A. Role of a copper (I)-dependent enzyme in the anti-platelet action of S-nitrosoglutathione. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;114:1083–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOW A.J., STAMLER J.S. Reactions between nitric oxide and haemoglobin under physiological conditions. Nature. 1998;391:169–173. doi: 10.1038/34402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIES A., BODE C., PETER K., HERR A., BOHRER H., MOTSCH J., MARTIN E. Inhaled nitric oxide inhibits human platelet aggregation, P-selectin expression, and fibrinogen binding in vitro and in vivo. Circulation. 1998;97:1481–1487. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.15.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAKIM T.S., SUGIMORI K., CAMPORESI E.M., ANDERSON G. Half-life of nitric oxide in aqueous solutions with and without haemoglobin. Physiol. Measurement. 1996;17:267–277. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/17/4/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HE J., WHELTON P.K., VU B., KLAG M.J. Aspirin and risk of hemorrhagic stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1998;280:1930–1935. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.22.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENRY Y., DUCROCQ C., DRAPIER J.C., SERVENT D., PELLAT C., GUISSANI A. Nitric oxide as a biological effector: EPR detection of nitrosyl-iron protein complexes in whole cells. Eur. Biophys. J. 1991;20:1–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00183275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOUSTON D., ROBINSON P., GERRARD J. Inhibition of intravascular platelet aggregation by endothelium-derived relaxing factor: reversal by red blood cells. Blood. 1990;76:953–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIA L., BONAVENTURA C., BONAVENTURA J., STAMLER J.S. S-Nitrosohaemoglobin: a dynamic activity of blood involved in vascular control. Nature. 1996;380:221–226. doi: 10.1038/380221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAGAN V.E., DAY B.W. Dynamics of haemoglobin. Nature. 1996;383:29–30. doi: 10.1038/383030b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANGFORD E.J., BROWN A.S., WAINWRIGHT R.J., DE BELDER A.J., THOMAS M.R., SMITH R.E.A., RADOMSKI M.W., MARTIN J.F., MONCADA S. Inhibition of platelet activity by S-nitrosoglutathione during coronary angioplasty. Lancet. 1994;344:1458–1460. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANGFORD E.J., PARFITT A., DE BELDER A.J., MARRINAN M.T., MARTIN J.F. A study of platelet activation during human cardiopulmonary bypass and the effect of S-nitrosoglutathione. Thromb. Haemostasis. 1997;78:1516–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANGFORD E.J., WAINWRIGHT R.J., MARTIN J.F. Platelet activation in acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina is inhibited by nitric oxide donors. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996;16:51–55. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEES C., LANGFORD E., BROWN A.S., DE BELDER A., PICKLES A., MARTIN J.F., CAMPBELL S. The effect of S-nitrosoglutathione on platelet activation, hypertension, and uterine fetal Doppler in severe preeclampsia. Obstetr. Gynecol. 1996;88:14–19. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIAO J.C., HEIN T.W., VAUGHN M.W., HUANG K.-T., KUO L. Intravascular flow decreases erythrocyte consumption of nitric oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:8757–8761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN W., VILLANI G.M., JOTHIANANDAN D., FURCHGOTT R.F. Selective blockade of endothelium-dependent and glyceryl trinitrate-induced relaxation by hemoglobin, and by methylene blue in the rabbit aorta. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1985;232:708–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEGSON I.L., GREIG I.R., GRAY G.A., WEBB D.J., BUTLER A.R. Prolonged effect of a novel S-nitrosated glyco-amino acid in endothelium-denuded rat femoral arteries: potential as a slow release nitric oxide donor drug. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1617–1624. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEHTA J.L., MEHTA P. Comparative effects of nitroprusside and nitroglycerin on platelet aggregation in patients with heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1980;2:25–33. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198001000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER M.R., ROSEBERRY M.J., MAZZEI F.A., BUTLER A.R., WEBB D.J., MEGSON I.L.Novel S-nitrosothiols do not engender vascular tolerance and remain effective in glyceryl trinitrate-tolerant rat femoral arteries Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000(in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- PALMER R.M.J., FERRIGE A.G., MONCADA S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of EDRF. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAWLOSKI J.R., SWAMINATHAN R.V., STAMLER J.S. Cell-free and erythrocytic S-nitrosohemoglobin inhibits human platelet aggregation. Circulation. 1998;97:263–267. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., PALMER R.M.J., MONCADA S. The anti-aggregating properties of vascular endothelium: interactions between prostacyclin and nitric oxide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987a;92:639–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., PALMER R.M.J., MONCADA S. Comparative pharmacology of EDRF, NO and prostacyclin in platelets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987b;92:181–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., PALMER R.M.J., MONCADA S. Endogenous nitric oxide inhibits human platelet adhesion to vascular endothelium. Lancet. 1987c;2:1057–1058. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., PALMER R.M.J., MONCADA S. The role of nitric oxide and cGMP in platelet adhesion to vascular endothelium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1987d;148:1482–1489. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(87)80299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., REES D.D., DUTRA A., MONCADA S. S-nitrosoglutathione inhibits platelet aggregation in vitro and in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;107:745–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOGO N., CAMPANELLA C., WEBB D.J., MEGSON I.L. S-Nitrosothiols cause prolonged, nitric oxide-mediated relaxation in human saphenous vein and internal mammary artery: therapeutic potential in bypass surgery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:1236–1244. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STAMLER J.S., LOSCALZO J. The antiplatelet properties of organic nitrates and related nitroso compounds in vitro and in vivo and their relevance to cardiovascular disorders. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1991;18:1529–1536. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90686-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAUGHN M.W, , HUANG K.T., KUO L., LIAO J.C. Erythrocytes possess an intrinsic barrier to nitric oxide consumption. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:2342–2348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOLZ M., MACALLISTER R.J., DAVIS D., FEELISCH M., MONCADA S., VALLANCE P., HOBBS A. Biochemical characterization of S-nitrosohemoglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:28983–28990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.28983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]