Abstract

This study demonstrates the localization of the prostaglandin (PG)D2 receptor (DP) within the mucous-secreting globlet cells of the human colon by in situ hybridization, which suggests a role for DP in mucous secretion. Selective high affinity ligands were used, therefore, to evaluate DP regulation of mucous secretion in LS174T human colonic adenocarcinoma cells.

The expression of hDP in LS174T cells was confirmed at the mRNA level by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, and at the protein level by radioligand binding assays and signal transduction (cyclic AMP accumulation) assays. PGD2 and the highly selective DP-specific agonist L-644,698 ((4-(3-(3-(3-hydroxyoctyl)-4-oxo-2-thiazolidinyl) propyl) benzoic acid) (racemate)), but not PGE2 competed for [3H]-PGD2-specific binding to LS174T cell membranes (Ki values of 0.4 nM and 7 nM, respectively). The DP-specific agonists PGD2, PGJ2, BW245C (5-(6-carboxyhexyl)-1-(3-cyclohexyl-3-hydroxypropylhydantoin)), and L-644,698 showed similar potencies in stimulating cyclic AMP accumulation (EC50 values: 45–90 nM) and demonstrated the expected rank order of potency. PGE2 also elicited cyclic AMP production in this cell line (EC50 value: 162 nM).

The activation of cyclic AMP production by PGD2 and L-644,698, but not PGE2, was inhibited by the selective DP antagonist BW A868C. Thus, PGD2 and L-644,698 act through hDP in LS174T cells. PGD2, L-644,698 and PGE2 (an established mucin secretagogue) potently stimulated mucin secretion in LS174T cells in a concentration-dependent manner (EC50<50 nM). However, BW A868C effectively antagonized only the mucin secretion mediated by PGD2 and L-644,698 and not PGE2. These data support a role for the DP receptor in the regulation of mucous secretion.

Keywords: Prostanoid receptor, DP, prostaglandin D2, human, colon, mucin, LS174T

Introduction

The primary bioactive prostanoids encompass prostaglandin (PG)D2, PGE2 PGF2α, prostacyclin (PGI2) and thromboxane A2. These products of arachidonic acid metabolism mediate biological activities through eight individual prostanoid receptors [DP, EP (EP1, EP2, EP3, EP4), FP, IP and TP] some of which have associated subtypes due to differential mRNA splicing. The prostanoid receptors form a distinct sub-family within the rhodopsin-type G protein-coupled receptor superfamily (for review see Coleman et al., 1994).

PGD2 is the bioactive prostanoid interacting preferentially with the DP receptor, and its synthesis is governed by the sequential actions of PGH synthase and PGD synthase. PGD2 is associated with both central and peripheral physiological effects. Centrally, PGD2 has been associated with sleep induction, modulation of body temperature, olfactory function, hormone release, nociception and neuromodulation. Within peripheral tissues, PGD2 has been shown to mediate vasodilation, inhibition of platelet aggregation, glycogenolysis, bronchoconstriction and vasoconstriction (for review: Giles & Leff, 1988; Ito et al., 1989). In addition, PGD2 is the major prostanoid synthesized by immunologically challenged mast cells (Lewis et al., 1982) and its release within this system is well characterized (Kawata et al., 1995; Murakami et al., 1995).

Comparatively little is known about the DP receptor. The cloning and characterization of the human (Boie et al., 1995), mouse (Hirata et al., 1994) and rat (Wright et al., 1999) species homologues have previously been reported and in each case the recombinant receptor demonstrated the ability to increase intracellular cyclic AMP in response to PGD2 and its various analogues. Various studies utilizing mouse and rat tissue slices to investigate the cell-specifc localization of DP mRNA by in situ hybridization support the roles for the DP receptor in the brain and spinal cord (Oida et al., 1997; Urade et al., 1993; Wright et al., 1999). In addition, strong positive signals were identified for mouse (Hirata et al., 1994) and human (Boie et al., 1995) DP receptor mRNA in the small intestine and ileum, respectively, by Northern blot analysis. A much weaker signal was also present in the stomach of the mouse. However, a defined role for DP in the gastrointestinal tract does not exist. Recently, we localized DP-specific mRNA transcripts to the mucous-secreting goblet cells and/or adjacent epithelium of the stomach, small intestine (duodenum, ileum) and colon whilst performing in situ hybridization in selected rat tissues (Wright et al., 1999). These results suggested that the regulation of mucin secretion may be a novel physiological role for the DP receptor. In support of this hypothesis, this report describes the DP-specific regulation of mucin secretion in a human colonic epithelial cell line.

Methods

In situ hybridization

Human colon tissue was removed during surgical biopsy and immediately processed using standard procedures for paraffin embedding (Martinez et al., 1995). Tissue blocks were cut into 4 μM sections and mounted on aminoalkylsilane-coated microscope slides. Solutions were made using water pretreated with diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) and new glassware was used to minimize nuclease activity.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to amplify two non-overlapping sequences of 300–400 bp found within the human DP receptor using the following primer pairs: Probe 1: hDP-ATG (5′-G CTC CCG CAC GCC ATG AAG TCG CCG-3′) and hDP-NcoA (5′-CCA GCA CTC CAG TGC CAT GGC CAG G-3′) and Probe 2: hDP-NcoSv2 (5′-TC CTG GCC ATG GCA CTG GAG TGC-3′) and hDP-PstAv2 (5′-CCG GTG CAT CGC ATA GAG GTT GC-3′). Probes 1 and 2 were cloned into pCR2.0 (Invitrogen).

Cloning into the pCR2.0 vector, preparation of pCR2.0 clones for use as templates for cRNA riboprobe synthesis (including DNA linearization by restriction digest, proteinase K treatment and phenol/chloroform extraction) and synthesis of digoxigenin-labelled cRNA riboprobes have previously been described (Wright et al., 1999). In situ hybridization including tissue preparation and probe hybridization, was also conducted as previously described (Wright et al., 1999).

Identification of prostanoid receptor transcripts

Gene expression of the eight prostanoid receptors within LS174T cells was analysed by reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR. Total RNA was isolated from LS174T cells using Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Burlington, Canada) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RT–PCR was performed on LS174T total RNA using a RT–PCR Core Kit (Perkin Elmer), with slight amendments to the manufacturer's protocol as follows: following the reverse transcriptase reaction, sense (S) and anti-sense (AS) primers were used to amplify cDNAs for human (h)EP1 (hEP1S: 5′-CCT TGG GTG TAC ATC CTA CTG-3′ and hEP1AS: 5′-AGA ATG GCT TTT TAT TCC CAA AG-3′), hEP2 (hEP2S: 5′-GAA AGC CCA GCC ATC AGC TC-3′ and hEP2AS: 5′-GCG AAG AGC ATG AGC ATC G-3′), hEP3 (hEP3S: 5′-AGA CGG CCA TTC AGC TTA TGG GGA-3′ and hEP3AS: 5′-GAA GAA GGA TCT TTC TTA ACA G-3′), hEP4 (hEP4S: 5′-ATC TTC GGG GTG GTG GGC AAC-3′ and hEP4AS: 5′-CGC TTG TCC ACG TAG TGG C-3′), hDP (hDPS: 5′-GGA GCA TTT AAG GAT GTC AAG-3′ and hDPAS: 5′-TTC CAT GTT AGT GGA ATT GCT G-3′), hFP (hFPS: 5′-TTT CAA CTT GTT TTT GCC AAT G-3′ and hFPAS: 5′-CAT GCA TGT GTT AAT TGA GGC T-3′), hIP (hIPS: 5′-CTG CTC CCT CTG CTG ACA TT-3′ and hIPAS: 5′-TCC TCT GTC CCT CAC TCT CTT C-3′), hTP (hTPS: 5′-CCC TGG GGA TCC ATC CTG TTC CGC CGC-3′ and hTPAS: 5′-GAG AAG GAA TTC CTA CTG CAG CCC GGA-3′), and β- actin (hBACS: 5′-ACA TTA AGG AGA AGC TGT GCT ATG T-3′ and hBACAS: 5′-CTT CAT GAT GGA GTT GAA GGT AGT T-3′). PCR was performed in 2 mM Mg2+ for all primer pairs except those for hTP as follows: initial denaturation at 99°C, 2 min; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C, 15 s, then annealing and extension at 57°C, 30 s; and a final extension at 72°C, 10 min (GeneAmp 9600 system; Perkin-Elmer/Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.). In the case of hTP, PCR was performed in 3.5 mM Mg2+ as follows: initial denaturation at 99°C, 2 min; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C, 15 s; then annealing and extension at 68°C, 30 s; and then a final extension at 72°C, 10 min. RT–PCR reaction products were resolved by gel electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The molecular sizes of the amplified products were determined by comparison with the molecular weight markers run in parallel.

LS174T cell culture and membrane preparation

Maintenance of LS174T human colonic adenocarcinoma cells (ATCC No. CL-188; Rockville, MD, U.S.A.) in culture was as previously described (Belley et al., 1996; Tse & Chadee, 1992).

Briefly, a high mucin expressing variant was obtained by serially passing LS174T cells through nude mice (nu/nu BALB/c). Cells from xenograph tumours were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in complete minimal essential medium (MEM) (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Burlington, Canada) containing 10% foetal bovine serum, 100 units ml−1 penicillin G, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin sulphate, and 20 mM HEPES). LS174T cell membranes were prepared by cell disruption in the presence of protease inhibitors using nitrogen cavitation as previously described (Wright et al., 1999).

[3H]-PGD2 binding to LS174T cell membranes

Radioligand binding assays were carried out as previously described (Wright et al., 1998). Briefly, assays were performed in 0.2 ml of 10 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM EDTA, 8 nM [3H]-PGD2 (115 Ci mmol−1) and 10 mM MnCl2. Compounds were added in dimethylsulphoxide (Me2SO) at 1% (v v−1) of the final incubation volume (vehicle concentration was constant throughout). The reaction was initiated by the addition of 350 μg cell membrane protein to all tubes and the samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Termination of the reaction and analysis of [3H]-PGD2-specific binding were performed as previously described (Wright et al., 1999). Non-specific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM PGD2.

Protein assays

Protein concentrations were measured by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, U.S.A.) using the manufacturer's protocol and bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Cyclic AMP accumulation assays in LS174T cells

Cyclic AMP accumulation assays were conducted using LS174T cells in suspension as previously described (Wright et al., 1998). LS174T cells were harvested at 80% confluence by rinsing the cells in prewarmed Versene 1 : 5000 (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Burlington, Canada) followed by enzyme-free cell dissociation buffer to facilitate their dissociation from the culture dish. Cells were thoroughly washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.4 (PBS) by resuspension and centrifugation (300×gmax, 6 min, room temperature) and finally resuspended in HBSS for functional assays. Cell viability (>60%) was determined by trypan blue exclusion. Generation of cyclic AMP was performed in a final incubation volume of 0.2 ml of HBSS containing 100 μM Ro 20-1724 to abrogate cyclic AMP hydrolysis. Compounds were added in Me2SO and the vehicle was 1% (v v−1) of the final incubation volume throughout. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 2×105 cells per incubation for both agonist and antagonist assays and the samples were incubated for 10 min at 37°C. Reactions were terminated and agonist concentration-response curves were analysed as previously described (Wright et al., 1999).

Antagonist potencies were determined by Schild analysis as follows: agonist concentration-response curves were constructed in the absence and presence of a fixed and increasing concentration of antagonist. Concentration-response curves were analysed and EC50 values determined. The equilibrium dissociation constant for the antagonist-receptor complex (Kb) was calculated from the following equation: dr=[B](Kb+1)−1, where dr is the equiactive dose ratio of the agonist (determined in the presence and absence of the antagonist) and [B] is the antagonist concentration used. Schild regression involves the following logarithmic manipulation of dr on [B]: log (dr-1)=log [B]−log Kb.

Analyses of statistical significance employed the statistical modelling software SuperANOVA (Abacus Concepts, Inc.; Berkley, CA, U.S.A.) to perform an analysis of variance (ANOVA). A two-way ANOVA was used to establish differences in the maximal efficacy of DP-specific agonists and a one-way ANOVA was performed to identify differences in agonism in the presence and absence of the DP-specific antagonist BW A868C. All statistically significant differences were analysed further by way of a Bonferroni/Dunn test of all means.

Mucin secretion assays

LS174T cells were grown in complete MEM to 80% confluence (approximately 4×105 cells per well) in 6-well plastic culture dishes (well diameter: 34.6 mm). Mucins were subjected to metabolic labelling by incubating cells for 48 h in complete MEM containing 1 μCi ml−1 [3H]-glucosamine (specific activity: 40 Ci mmol−1; ICN Biomedicals Inc., Irvine, CA, U.S.A.). Cells were washed three times with warm MEM and incubated in 3 ml complete MEM. The cell media were collected at the required time points for analysis of secreted radiolabelled glycoproteins as follows: samples were centrifuged to remove cell debris (2500×g, 5 min, room temperature) and then an equal volume of 10% (w v−1) trichloroacetic acid (TCA), 1% (w v−1) phosphotungstic acid (PTA) (Sigma Chemical Co.) was added to precipitate the secreted radiolabelled glycoproteins overnight. Precipitated material was collected by centrifugation (1800×g, 5 min, 4°C), solubilized in PBS (pH 7.2), and neutralized to pH 7 with 0.1 M NaOH. Radiolabelled mucins were separated from non-mucin radiolabelled glycoproteins by Sepharose 4B column chromatography as described previously (Belley et al., 1996).

High molecular weight mucins elute in the void volume by Sepharose 4B column chromatography (Chadee et al., 1987). It was determined that 98±2% of the TCA/PTA-precipitable [3H]-glycoproteins were recovered in the void volume. Accordingly, subsequent analyses were performed directly on the solubilized, neutralized, TCA/PTA protein precipitates. Data were calculated as the percentage change in secreted [3H]-glucosamine relative to vehicle-challenged control wells.

Analysis of statistical significance employed the statistical modelling software SuperANOVA (Abacus Concepts, Inc.) to perform a two-way ANOVA to analyse differences in mucin secretagogue activity mediated by increasing ligand concentrations. A one-way ANOVA was performed to identify differences in secretagogue activity in the presence and absence of the DP-specific antagonist BW A868C. All statistically significant differences were further analysed by way of a Bonferroni/Dunn test of all means.

Reagents

PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, U46619 (9,11-dideoxy-9α, 11α-methanoepoxy-PGF2α), PGJ2 and Ro-20-1724 (4-(3-butoxy-4-methoxybenzyl)-2-imidaxlidinone) were from Biomol Research Laboratories (Plymouth Meeting, PA, U.S.A.). BW245C (5-(6-carboxyhexyl)-1-(3-cyclohexyl-3-hydroxypropylhydantoin)) and BW A868C ((±)-3-benzyl-5-(6-carboxyl)-1-(2-cyclohexyl-2-hydroxyethylamino)-hydantoin) were from The Wellcome Foundation Ltd (Beckenham, Kent, U.K.). L-644,698 ((4-(3-(3-(3-hydroxyoctyl)-4-oxo-2-thiazolidinyl) propyl) benzoic acid) (racemate)) was synthesized at Merck Research Laboratories by Dr J.B. Bicking. Iloprost (5-(hexahydro-5-hydroxy-4-(3-hydroxy-4-methyl-1-octen-6-ynyl)-2(1H)-pentalenylidene) pentanoic acid) and [125I]-cyclic AMP scintillation proximity assay kits were from Amersham (Oakville, ON, Canada). [3H]-PGD2 was from Dupont NEN (Boston, MA, U.S.A.).

Results

In situ hybridization of DP in human colon

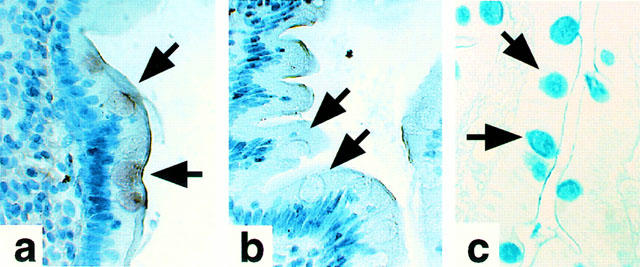

In situ hybridization reactions were carried out to determine the cell-specific localization of DP receptor mRNA transcripts within human colon tissue using digoxigenin-labelled human DP receptor-specific cRNA riboprobes (Figure 1). Experiments using two distinct, non-overlapping, anti-sense riboprobes specific for the hDP receptor corroborated positive results. Negative control experiments were performed employing exact complementary sense riboprobes. Positive staining was identified using the anti-sense riboprobes within the mucous-secreting goblet cells of human colon tissue (Figure 1a). This staining was absent in the presence of the negative sense control riboprobes (Figure 1b). The localization of goblet cells within the human colon biopsy sections under study was confirmed by staining with Alcian Blue (Figure 1c), an established stain for acidic mucopolysaccharides (Steedman, 1950).

Figure 1.

Histochemical localization of DP receptor mRNA in human colon tissue by in situ hybridization. Results (400×mag) illustrate a strong, specific, positive signal obtained within the mucous-producing goblet cells upon application of the anti-sense probe (a) that was not present with application of the exact complementary sense probe (b) used as a negative control. Data were confirmed using two independent non-overlapping anti-sense riboprobes with the respective complementary sense riboprobes. Goblet cells were identified using Alcian Blue (c).

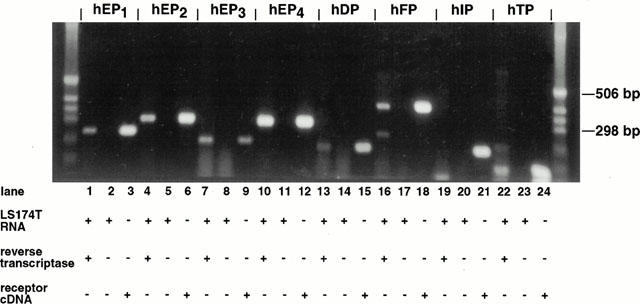

Identification of prostanoid receptor transcripts in LS174T cells

Total RNA was subjected to RT–PCR to survey the gene expression of mRNA transcripts corresponding to the eight human prostanoid receptors within LS174T cells (Figure 2). Expression of transcripts corresponding to hEP1, hEP2, hEP3, hEP4, hDP, hFP and hTP in LS174T cells was confirmed by the migration of each receptor-specific amplified cDNA fragment (lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16 and 22, respectively) to the predicted position. Results were confirmed by the migration pattern of receptor-specific positive control reactions (lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18 and 24, respectively). Receptor-specific negative control reactions (lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20 and 23, respectively) performed without reverse transcriptase confirmed in each case that the template for amplification was RNA. In contrast to these results, there was no detectable cDNA fragment synthesized corresponding to the hIP receptor (lane 19) that co-migrated with the amplified product generated in the positive control reaction for hIP (lane 21). RT–PCR reactions employing primers designed to human β-actin were used as a positive control (data not shown). cDNA fragments corresponding to human β-actin were amplified in a reverse transcriptase-dependent manner. The β-actin fragments co-migrated with fragments generated from an analogous positive control PCR reaction employing human β-actin cDNA as a template.

Figure 2.

Expression of human prostanoid receptor mRNA in LS174T cells. As described under Methods, RT–PCR was performed using total RNA isolated from cultured LS174T cells, in the presence of reverse transcriptase and employing primers specific for each of the human prostanoid receptors: EP1, EP2, EP3, EP4 DP, FP, IP and TP (lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19 and 22, respectively). Analogous negative control reactions for each primer pair were performed under the same conditions but in the absence of reverse transcriptase (lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20 and 23). Positive control PCR reactions were performed for each primer pair using the corresponding receptor cDNA as the template, in order to generate PCR products of the expected size as markers (lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21 and 24). PCR products were resolved on a 1.2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

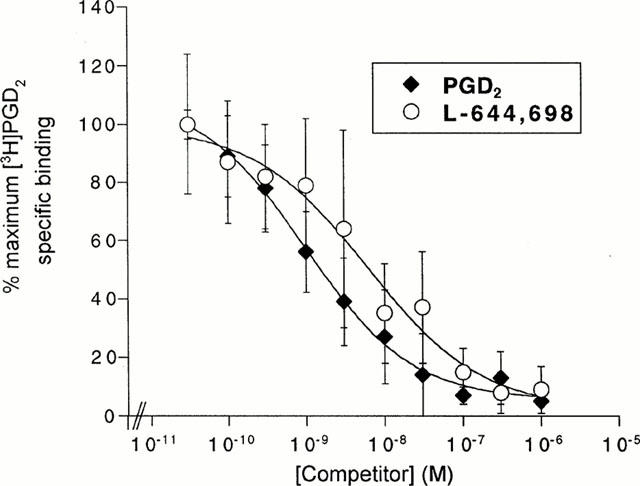

Radioligand binding to LS174T cell membranes

Equilibrium competition binding experiments were performed employing [3H]-PGD2 to determine if DP-specific binding to LS174T cell membranes could be measured (Figure 3). Both PGD2 and the selective DP-agonist L-644,698 competed in a concentration-dependent manner for [3H]-PGD2-specific binding to LS174T membranes, with inhibitor constant (Ki) values of 0.4±0.1 nM and 7.0±7.5 nM, respectively (n=3). However, PGE2 did not compete for [3H]-PGD2-specific binding to LS174T membranes at concentrations up to 1 μM (data not shown). These results support the hypothesis that radioligand binding is to DP.

Figure 3.

Competition for [3H]-PGD2-specific binding to LS174T cell membranes by DP-specific agonists. Radioligand membrane binding assays were carried out as previously described under Methods. Equilibrium competition binding assays were conducted using 0.03–1000 nM PGD2 or L-644,698. Data points are the mean and s.e.mean of values from three independent experiments each performed in duplicate.

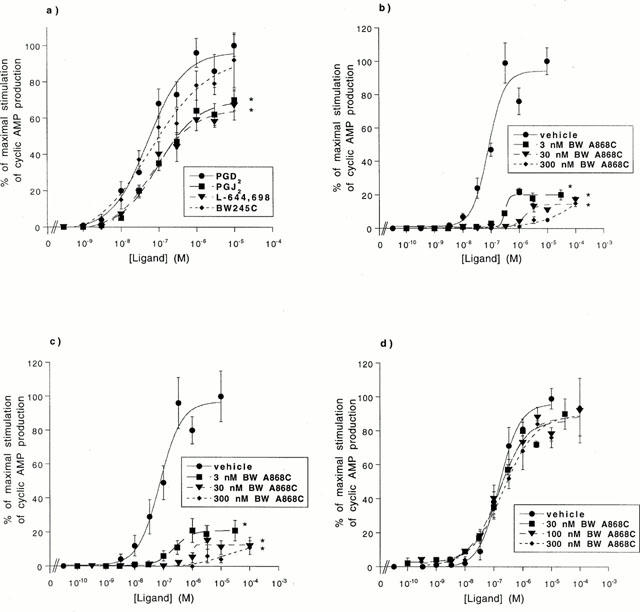

Cyclic AMP accumulation in LS174T cells

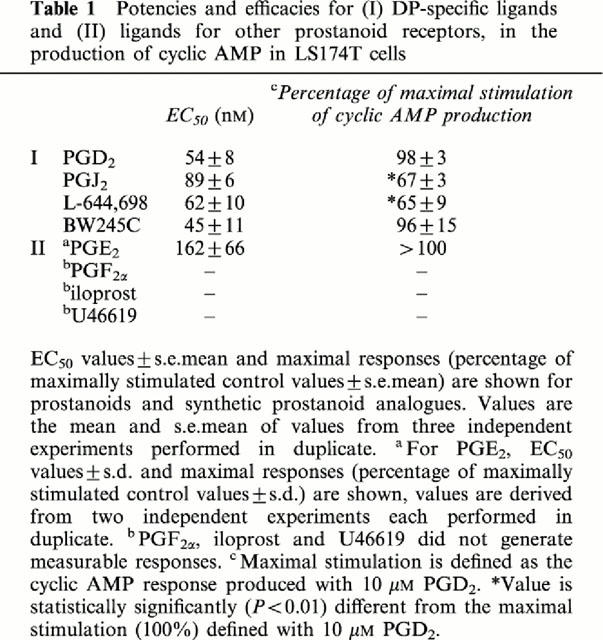

The stimulation of cyclic AMP production by adenylate cyclase is the predominating signalling pathway for the DP receptor. Second messenger assays were performed to investigate the capacity of LS174T cells to generate cyclic AMP in response to DP-specific agonists and agonists selective for other receptor specificities (Figure 4a and Table 1). Several DP agonists were potent in this regard with EC50 values of approximately 50 nM, resulting in a rank order of BW245C=PGD2=L-644,698=PGJ2. Generally, prostanoids and prostanoid analogues of other receptor specificities were without measurable response with the exception of PGE2, which demonstrated an EC50 value of 162 nM (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Cyclic AMP production in LS174T cells. (a) LS174T cells were challenged with 0.3 nM–10 μM of PGD2, PGJ2, L-644,698, or BW245C. Maximal (100%) cyclic AMP production is defined as the amount of cyclic AMP generated in response to 10 μM PGD2. Data points are the mean and s.e.mean of values from three independent experiments performed in duplicate. The asterisk (*) denotes a ligand demonstrating a statistically significant difference (P<0.01) in maximal efficacy relative to the maximal stimulation (100%) defined with 10 μM PGD2. (b,c) LS174T cells were pre-incubated with vehicle, 3 nM BW A868C, 30 nM BW A868C or 300 nM BW A868C and then challenged with 0.03 nM–100 μM (b) PGD2, or (c) L-644,698. (d) LS174T cells were pre-incubated with vehicle, 30 nM BW A868C, 100 nM BW A868C or 300 nM BW A868C and then challenged with 0.03 nM–100 μM PGE2. In panels (b–d) the maximal (100%) cyclic AMP production for a given agonist is defined as the amount of cyclic AMP generated in response to 10 μM of that agonist in the absence of BW A868C. Data points are the mean and s.d. of values from two independent experiments performed in duplicate. The asterisk (*) denotes a ligand demonstrating a statistically significant (P<0.01) difference in maximal efficacy in the presence, relative to the absence, of BW A868C.

Table 1.

Potencies and efficacies for (I) DP-specific ligands and (II) ligands for other prostanoid receptors, in the production of cyclic AMP in LS174T cells

The maximal response for each ligand (the amount of cyclic AMP produced at a concentration of 10 μM) was normalized to that elicited by 10 μM PGD2 (Table 1). The DP-specific ligand BW245C responded as a full agonist in LS174T cells, with a normalized maximal response of approximately 100%. In contrast, the DP-specific ligands PGJ2 and L-644,698 were significantly less efficacious than the maximal stimulation defined by PGD2 (P<0.01), with normalized maximal responses of 67% and 65%, respectively and therefore demonstrated partial agonism. PGE2 mediated a maximal response greater than that mediated by 10 μM PGD2.

The ability of the DP antagonist BW A868C to abrogate the cyclic AMP production stimulated in LS174T cells by the DP-specific agonists PGD2 (Figure 4b) and L-644,698 (Figure 4c), as well as PGE2 (Figure 4d), was then investigated. BW A868C functioned as a potent, insurmountable, DP-specific antagonist. This was demonstrated by the inability of PGD2 and L-644,698 to reach maximal efficacy in the presence of 3–300 nM BW A868C. The insurmountable nature of the antagonism produced by BW A868C in this cell line precluded calculation of pKb values or Schild plot ratios. The antagonism mediated at all concentrations of BW A868C against the DP-specific agonists was statistically significant (P<0.01). However, the published pKb value for BW A868C is approximately 3 nM (Giles et al., 1989). In marked contrast, BW A868C was inefficient at antagonizing the PGE2-mediated cyclic AMP response.

Mucin secretion in LS174T cells

The LS174T cell line was used to investigate the mucin secretagogue activity of DP receptor agonists because it is an established model for the in vitro study of mucin secretion (Belley & Chadee, 1999; Kuan et al., 1987). In preliminary experiments, the time course of PGD2-mediated mucin secretion was established (data not shown). Forskolin was used as a positive control, since it is a known mucin secretagogue (McCool et al., 1990). Over a 12 h time course forskolin (50 μM) stimulated mucin secretion to a level 87% above vehicle-stimulated control values. In comparison, PGD2 (250 nM) attained a maximal amount of mucin secretion of 52% above vehicle control over the same period of time. Forskolin stimulated mucin secretion in a linear fashion over the 12 h time course, while PGD2-mediated mucin secretion reached a plateau after 3–6 h of incubation. These experiments confirmed that PGD2 has the ability to stimulate mucin secretion and experiments were routinely conducted over a 6 h incubation period.

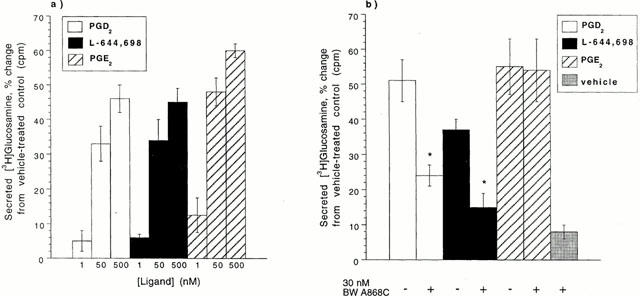

To establish further that the DP receptor was specifically mediating mucin secretion, increasing concentrations of DP-specific agonists were investigated to ascertain if they could stimulate a concentration-dependent response (Figure 5a). PGE2 was included as a positive control, because it is an established mucin secretagogue in LS174T cells (Belley & Chadee, 1999). Incubation with increasing concentrations (1, 50, and 500 nM) of PGD2, L-644,698 or PGE2 resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in mucin secretion that was statistically significant (P<0.01). The EC50 values for mucin secretion were comparable for all three agonists. The rank order for maximal mucin secretion was PGE2>PGD2=L-644,698.

Figure 5.

Mucin secretion from LS174T cells. (a) LS174T cells were challenged with 1, 50, or 500 nM PGD2, L-644,698, or PGE2 for 6 h. A statistically significant (P<0.01) difference was observed for each ligand in the amount of [3H]-glucosamine secreted at 50 nM relative to 1 nM and at 500 nM relative to 50 nM. (b) Following pre-incubation with vehicle or 30 nM BW A868C for 30 min, LS174T cells were challenged with 100 nM PGD2, L-644,698, PGE2, or vehicle for 6 h. Data points are the mean and s.d. of values from two independent experiments performed in duplicate. The asterisk (*) denotes a ligand demonstrating a statistically significant (P<0.01) difference in the presence, relative to the absence, of the antagonist.

The DP-specific antagonist BW A868C was employed to demonstrate that mucin secretion was DP receptor-specific (Figure 5b). LS174T cells were first pre-incubated for 30 min with 30 nM BW A868C or ethanol (vehicle) and were then incubated for 6 h in the presence or absence of PGD2, L-644,698, or PGE2 (100 nM). Cells incubated with the antagonist alone responded with a slight increase in secreted mucins of 8%. The mucin secretion observed when cells were stimulated with 100 nM PGD2 or L-644,698 was significantly inhibited (P<0.01) by 53 and 59%, respectively, when cells were pre-incubated with 30 nM BW A868C prior to agonist addition. However, pre-incubation of cells with 30 nM BW A868C had no effect on the PGE2-mediated mucin secretion, demonstrating that DP agonist-induced mucin secretion in LS174T occurs via an independent pathway to that provoked by PGE2. These data suggest that DP receptor activation stimulates mucin secretion.

Discussion

This paper provides evidence for a novel physiological role for the DP receptor, namely the regulation of mucin secretion. This role was first suggested by work from this laboratory showing the presence of the DP receptor in mucous-secreting goblet cells of the rat by in situ hybridization. In this report we confirm this is not a species-specific observation, by demonstrating that DP receptor mRNA is also localized in mucous-secreting goblet cells of the human colon. This result validated the use of the human LS174T colonic adenocarcinoma cell line, an established in vitro model of mucin secretion that endogenously expresses the DP receptor, as a system to study the role of DP in mucous production. The presence of DP within LS174T cells was confirmed at the level of transcription, specific radioligand binding, second messenger coupling and mucin secretion, utilizing DP-specific agonists (PGD2, L-644,698) and a DP-specific antagonist (BW A868C).

The endogenous DP receptor expressed in LS174T cells shows similar properties to recombinant hDP expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK293(EBNA)) cells (Wright et al., 1998). The Ki values for PGD2 and the selective DP agonist L-644,698 determined in radioligand binding assays were comparable between endogenous and recombinant hDP (0.5–7 nM). As expected, PGE2 had reduced affinity compared with PGD2 and L-644,698. These results support [3H]-PGD2 binding specifically to hDP in LS174T cells. Activation of DP stimulates intracellular cyclic AMP production. The EC50 values for cyclic AMP production stimulated by DP agonists in LS174T cells (54–89 nM) were all 100 fold less potent than those previously identified for recombinant hDP in HEK293(EBNA) cells (Wright et al., 1998), but the same rank order of potency was observed: PGD2=PGJ2=L-644,698=BW245C. In the current study, PGD2 and BW245C both demonstrated full agonism while PGJ2 and L-644,698 were both partial agonists, in contrast to results with recombinant hDP where all four DP compounds functioned as full agonists. This disparity is probably due to the high number of hDP receptors in the recombinant cell line compared with that of endogenous hDP in LS174T, as demonstrated by the level of radioligand binding. Saturation analyses of the recombinant hDP receptor in HEK cells demonstrated that the level of receptor expression was high at ∼6 pmol mg−1. Furthermore, two sites of specific binding were detected in the cell line transfected with the recombinant receptor; a high affinity, G protein-coupled site and a low affinity, G protein-uncoupled site. In contrast, saturation analyses could not be performed to estimate the level of endogenous DP expressed in LS174T cells because binding capacity was so poor. It should be noted that experiments investigating binding of the recombinant receptor employed 50 μg of membrane protein, while a similar level of binding in experiments addressing the endogenous receptor utilized 350 μg of membrane protein. Membranes were prepared using the same protocol in each case.

Cyclic AMP accumulation was also measured in LS174T cells challenged with the preferred ligands for prostanoid receptors other than DP, since RT–PCR suggested the presence of multiple types of prostanoid receptors (hDP, hEP1, hEP2, hEP3, hEP4, hFP, and hTP) in these cells. PGE2 induced increases in intracellular cyclic AMP (EC50=162 nM). This represents a balance of contributions from different EP receptors: the stimulation of cyclic AMP production mediated by hEP2 and hEP4 and the inhibition of cyclic AMP production mediated by hEP3. The IP receptor agonist iloprost was functionally silent, corroborating the RT–PCR experiments that did not detect IP mRNA. This data supports the functional expression of hDP in the LS174T cell line. Furthermore, it verifies the presence of multiple prostanoid receptors within LS174T cells that signal through the cyclic AMP pathway. In this report, therefore, we employ DP selective ligands to investigate the contribution of DP to mucous secretion in this cell line.

BW A868C clearly functions as an insurmountable antagonist at the DP receptor in LS174T cells in the current study. Previous characterization of BW A868C, however, suggested that it functions as a DP-specific competitive, surmountable antagonist (Giles et al., 1989). The differences observed between these two studies may be attributable to the kinetics of formation of the antagonist-receptor complex, as has previously been suggested for the angiotensin II AT1 receptor (Vanderheyden et al., 1999). Although no kinetic data is available for BW A868C, the time interval of pre-incubation of the antagonist with cells prior to agonist addition differs between the two studies, 2 min previously and 10 min here. If BW A868C has a slow Kon Koff−1, then its competitive antagonism could be surmountable under conditions of short pre-incubation time and insurmountable under conditions of longer pre-incubation time.

There are no previous reports describing a role for PGD2 in the regulation of DP-mediated mucin secretion. The current study is the first to identify that mucin secretion can occur in response to DP-specific ligands, i.e. using PGD2 and L-644,698 at concentrations ranging from 1–500 nM with an EC50 of less than 50 nM for both ligands.

The concentrations used of the DP agonists might be considered close to those relevant in vivo, and agree well in this regard with a report identifying a significant increase in mucin secretion upon challenge of rabbit gastric mucosal explants with 10 nM PGE2 (Seidler et al., 1988). The ability of PGE2 and PGF2β to regulate mucin secretion is well established (Belley & Chadee, 1999; Enss et al., 1995; Lamont et al., 1983; McCool et al., 1990; Phillips et al., 1993; Plaisancie et al., 1997; Seidler & Sewing, 1989) in several cell lines and tissue explants from various species. In contrast to the results observed with the DP agonists, many of these studies have used supra-physiological concentrations of ligands, typically in the micromolar range. For instance, concentrations of ligand (PGE1, PGE2 and 16,16-dimethyl PGE2, respectively) greater than or equal to 1 μM were employed in studies with the cultured human mucous-secreting cell lines T84 (McCool et al., 1990) and HT29-18N2 (Phillips et al., 1993), and cultured pig gastric mucous cells (Enss et al., 1995). Similarly, in a study employing carbachol, A23187 and histamine, the lowest concentration used of these three compounds was 10 μM (McCool et al., 1990).

In this report we have used the selective DP agonist L-644,698 to show that mucin secretion occurs through the DP receptor. L-644,698 was employed because it is one of the most selective DP agonists reported to date with at least 300 fold higher affinity for hDP over any of the other cloned prostanoid receptors (Wright et al., 1998). In a recent report, Belley & Chadee (1999) show that mucin secretion in LS174T cells is regulated by hEP4 which acts by increasing cyclic AMP like PGD2. It was particularly important, therefore, to use selective DP-specific tools to delineate clearly the contribution of the hDP receptor in the mucin response. In comparison to BW245C, L-644,698 has a 100 fold reduced affinity for hEP4 versus hDP (130 nM and 9.3 μM (Wright et al., 1998). In addition, using the antagonist BW A868C in combination with both PGD2 and PGE2 provides further support for the DP-specific regulation of mucin secretion. PGD2- and L-644,698-mediated increases in cyclic AMP production and stimulation of mucin secretion in LS174T cells were both effectively antagonized by BW A868C at 3 nM. In contrast, BW A868C had no effect on PGE2-mediated increases in cyclic AMP and mucin release at concentrations up to 300 nM. These data provide compelling evidence that mucin secretion in LS174T cells can be induced by the DP receptor.

A definitive role for the DP receptor in gastrointestinal (GI) physiology has not been demonstrated. Studies of PGD2-mediated effects within the GI tract have focused on smooth muscle contraction and ion secretion. Both contractile and relaxant roles for PGD2 have been reported in the GI tract, but several studies were also negative (Giles & Leff, 1988). PGD2 administration has been correlated with contraction in the rat fundus, rabbit jejunum (Horton & Jones, 1974) and guinea-pig (longitudinal) ileum (Bennett et al., 1980), as well as relaxation of guinea-pig ileum (Bennett & Sanger, 1978) and rabbit stomach (Whittle et al., 1979). PGD2 was without effect in the human colon and stomach (Sanger et al., 1982). PGD2 has also been reported to both facilitate (Frieling et al., 1994) and inhibit (Goerg et al., 1991) chloride secretion in guinea-pig colon and rat colon, respectively. In addition, the T84 human intestinal cell line was reported to stimulate chloride secretion with low potency when challenged with PGD2 (Barrett, 1992). The current report is the first indication that the DP receptor mediates mucin secretion. PGD2-mediated mucin secretion may occur through a mechanism originally described by Powell (1991) and modified by Eberhart & Dubois (1995) for electrolyte transport, whereby inflammatory cells, particularly mast cells, release mediators upon activation of the inflammatory response. PGD2 is the major prostanoid released by mast cells (Lewis et al., 1982) and mast cell degranulation is a prominent feature of certain conditions such as Crohn's disease (Dvorak et al., 1978).

In conclusion, we report the identification of DP mRNA in the mucous-secreting goblet cells of the human colon. We have used the LS174T human colonic adenocarcinoma cell line, an established in vitro model of mucin secretion, to investigate a potential role for DP. The expression of endogenous functional DP in LS174T cells has been demonstrated and its ability to activate mucin secretion has been confirmed through the use of selective DP ligands.

Acknowledgments

The authors would particularly like to thank Dr François Nantel for his assistance with the localization of DP, Dr Adel Giaid (Montreal General Hospital) for providing the human colon tissue, Dr Mark Abramovitz for useful discussions, Dr Annette Robichaud for advice on statistical analyses, Adam Belley (McGill University) for technical assistance and useful discussions, Maria Cirino for technical assistance, and Louise Charlton for administrative assistance. BW245C and BW A868C were generous gifts from The Wellcome Foundation Ltd (Beckenham, Kent, U.K.). Financial assistance was provided by a Medical Research Council – Pharmaceutical Manufacturer's Association of Canada Health Program Award.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- AS

anti-sense

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- DEPC

diethyl pyrocarbonate

- DP

prostaglandin D2 receptor

- dr

dose ratio

- GI

gastrointestinal

- h

human

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- Me2SO

dimethylsulphoxide

- MEM

minimal essential medium

- nu/nu Balb/c

nude Balb/c mice

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PG

prostaglandin

- PTA

phosphotungstic acid

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- S

sense

- TCA

trichloroacetic acid

References

- BARRETT K.E. Effect of histamine and other mast cell mediators on T84 epithelial cells. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1992;664:222–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb39763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELLEY A., CHADEE K. Prostaglandin E(2) stimulates rat and human colonic mucin exocytosis via the EP(4) receptor. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1352–1362. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELLEY A., KELLER K., GROVE J., CHADEE K. Interaction of LS174T human colon cancer cell mucins with Entamoeba histolytica: an in vitro model for colonic disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1484–1492. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENNETT A., SANGERG G.J. The effects of prostaglandin D2 on the circular muscle of guinea-pig isolated ileum and colon [proceedings] Br. J. Pharmacol. 1978;63:357P–358P. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENNETT A., PRATT D., SANGER G.J. Antagonism by fenamates of prostaglandin action in guinea-pig and human alimentary muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1980;68:357–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1980.tb14548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOIE Y., SAWYER N., SLIPETZ D.M., METTERS K.M., ABRAMOVITZ M. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human prostanoid DP receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:18910–18916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHADEE K., PETRI W.A., JR, INNES D.J., RAVDIN J.I. Rat and human colonic mucins bind to and inhibit adherence lectin of Entamoeba histolytica. J. Clin. Invest. 1987;80:1245–1254. doi: 10.1172/JCI113199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLEMAN R.A., SMITH W.L., NARUMIYA S. International Union of Pharmacology classification of prostanoid receptors: properties, distribution, and structure of the receptors and their subtypes. Pharmacol. Rev. 1994;46:205–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DVORAK A.M., MONAHAN R.A., OSAGE J.E., DICKERSIN G.R. Mast-cell degranulation in Crohn's disease [letter] Lancet. 1978;1:498. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EBERHART C.E., DUBOIS R.N. Eicosanoids and the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:285–301. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENSS M.L., SCHMIDT-WITTIG U., HEIM H.K., SEWING K.F. Prostaglandin E2 alters terminal glycosylation of high molecular weight glycoproteins, released by pig gastric mucous cells in vitro. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1995;52:333–340. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(95)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRIELING T., RUPPRECHT C., KROESE A.B., SCHEMANN M. Effects of the inflammatory mediator prostaglandin D2 on submucosal neurons and secretion in guinea pig colon. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:G132–G139. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.1.G132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILES H., LEFF P. The biology and pharmacology of PGD2. Prostaglandins. 1988;35:277–300. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(88)90093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILES H., LEFF P., BOLOFO M.L., KELLY M.G., ROBERTSON A.D. The classification of prostaglandin DP-receptors in platelets and vasculature using BW A868C, a novel, selective and potent competitive antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989;96:291–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11816.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOERG K.J., DIENER C., DIENER M., RUMMEL W. Antisecretory effect of prostaglandin D2 in rat colon in vitro: action sites. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;260:G904–G910. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1991.260.6.G904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRATA M., KAKIZUKA A., AIZAWA M., USHIKUBI F., NARUMIYA S. Molecular characterization of a mouse prostaglandin D receptor and functional expression of the cloned gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:11192–11196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORTON E.W., JONES R.L. Proceedings: Biological activity of prostaglandin D2 on smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1974;52:110P–111P. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO S., NARUMIYA S., HAYAISHI O. Prostaglandin D2: a biochemical perspective. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1989;37:219–234. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(89)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWATA R., REDDY S.T., WOLNER B., HERSCHMAN H.R. Prostaglandin synthase 1 and prostaglandin synthase 2 both participate in activation-induced prostaglandin D2 production in mast cells. J. Immunol. 1995;155:818–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUAN S.F., BYRD J.C., BASBAUM C.B., KIM Y.S. Characterization of quantitative mucin variants from a human colon cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 1987;47:5715–5724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMONT J.T., VENTOLA A.S., MAULL E.A., SZABO S. Cysteamine and prostaglandin F2 beta stimulate rat gastric mucin release. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:306–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEWIS R.A., SOTER N.A., DIAMOND P.T., AUSTEN K.F., OATES J.A., ROBERTS L.J.D. Prostaglandin D2 generation after activation of rat and human mast cells with anti-IgE. J. Immunol. 1982;129:1627–1631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTINEZ A., MILLER M.J., QUINN K., UNSWORTH E.J., EBINA M., CUTTITTA F. Non-radioactive localization of nucleic acids by direct in situ PCR and in situ RT–PCR in paraffin-embedded sections. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1995;43:739–747. doi: 10.1177/43.8.7542678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCOOL D.J., MARCON M.A., FORSTNER J.F., FORSTNER G.G. The T84 human colonic adenocarcinoma cell line produces mucin in culture and releases it in response to various secretagogues. Biochem. J. 1990;267:491–500. doi: 10.1042/bj2670491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURAKAMI M., BINGHAM C.O., III, MATSUMOTO R., AUSTEN K.F., ARM J.P. IgE-dependent activation of cytokine-primed mouse cultured mast cells induces a delayed phase of prostaglandin D2 generation via prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase-2. J. Immunol. 1995;155:4445–4453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OIDA H., HIRATA M., SUGIMOTO Y., USHIKUBI F., OHISHI H., MIZUNO N., ICHIKAWA A., NARUMIYA S. Expression of messenger RNA for the prostaglandin D receptor in the leptomeninges of the mouse brain. FEBS Lett. 1997;417:53–56. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PHILLIPS T.E., STANLEY C.M., WILSON J. The effect of 16,16-dimethyl prostaglandin E2 on proliferation of an intestinal goblet cell line and its synthesis and secretion of mucin glycoproteins. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1993;48:423–428. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(93)90047-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLAISANCIE P., BOSSHARD A., MESLIN J.C., CUBER J.C. Colonic mucin discharge by a cholinergic agonist, prostaglandins, and peptide YY in the isolated vascularly perfused rat colon. Digestion. 1997;58:168–175. doi: 10.1159/000201440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POWELL D.W.Immunophysiology of intestinal electrolyte transport Handbook of physiology 1991Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society; ed. Schultz, S.G., Field, M., Frizzell, R.A. & Rauner, B.B. [Google Scholar]

- SANGER G.J., JACKSON A., BENNETT A. A prostaglandin analogue which potently relaxes human uterus but not gut muscle. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1982;81:141–143. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(82)90613-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEIDLER U., KNAFLA K., KOWNATZKI R., SEWING K.F. Effects of endogenous and exogenous prostaglandins on glycoprotein synthesis and secretion in isolated rabbit gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:945–951. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEIDLER U., SEWING K.F. Ca2+-dependent and -independent secretagogue action on gastric mucus secretion in rabbit mucosal explants. Am. J. Physiol. 1989;256:G739–G746. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1989.256.4.G739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEEDMAN H.F. Alcian Blue 8GS: A new stain for mucin. Q. J. Microsc. Sci. 1950;91:477–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSE S.K., CHADEE K. Biochemical characterization of rat colonic mucins secreted in response to Entamoeba histolytica. Infect. Immun. 1992;60:1603–1612. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1603-1612.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- URADE Y., KITAHAMA K., OHISHI H., KANEKO T., MIZUNO N., HAYAISHI O. Dominant expression of mRNA for prostaglandin D synthase in leptomeninges, choroid plexus, and oligodendrocytes of the adult rat brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:9070–9074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANDERHEYDEN P.M., FIERENS F.L., DE BACKER J.P., FRAEYMAN N., VAUQUELIN G. Distinction between surmountable and insurmountable selective AT1 receptor antagonists by use of CHO-K1 cells expressing human angiotensin II AT1 receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:1057–1065. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITTLE B.J., MUGRIDGE K.G., MONCADA S. Use of the rabbit transverse stomach-strip to identify and assay prostacyclin, PGA2, PGD2 and other prostaglandins. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1979;53:167–172. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(79)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WRIGHT D.H., METTERS K.M., ABRAMOVITZ M., FORD-HUTCHINSON A.W. Characterization of the recombinant human prostanoid DP receptor and identification of L-644,698, a novel selective DP agonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:1317–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WRIGHT D.H., NANTEL F., METTERS K.M., FORD-HUTCHINSON A.W. A novel biological role for prostaglandin D2 is suggested by distribution studies of the rat DP prostanoid receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;377:101–115. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]