Abstract

Failing cardiac hypertrophy is associated with an inadequate sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) function. The hypothesis was examined that pressure overloaded hearts fail to increase SR Ca2+ uptake rate proportionally to the hypertrophy and that carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 inhibition by etomoxir ((±)-ethyl 2[6(4-chlorophenoxy)hexyl] oxirane-2-carboxylate) can counteract this process.

Severe left ventricular pressure overload was induced in rats by constricting the ascending aorta for 8, 10, 14 and 28 weeks leading to cardiac hypertrophy (+62–+103% of sham-operated rats) and pulmonary congestion. Homogenate oxalate-facilitated SR Ca2+ uptake rate g wet wt−1 was reduced (P<0.05) by 29.9±1.8% irrespective of phospholamban phosphorylation (in the presence of catalytic subunit of protein kinase A) and inhibition of SR Ca2+ release channel by ruthenium red. SERCA2 protein level was reduced (P<0.05) by 30.4±0.8%.

SR Ca2+ uptake rate was inversely correlated (P<0.05) with left ventricular weight but was not affected by the occurrence of pulmonary congestion. Because SR Ca2+ uptake rate of whole ventricles was not reduced, a hypertrophy proportional dilution of SR Ca2+ uptake has to be inferred which precedes pulmonary congestion.

Treatment with etomoxir (15 mg kg body wt−1 day−1 for 10 weeks) did not affect left ventricular weight but decreased (P<0.05) the right ventricular hypertrophy related to pulmonary congestion. In parallel, SR Ca2+ uptake rate of left ventricle and myosin isozyme V1 were increased (P<0.05).

Etomoxir represents a candidate approach for prevention of heart failure by inducing a hypertrophy proportional increase in SR Ca2+ uptake rate.

Keywords: CPT-1 inhibitor, etomoxir, heart failure, heart hypertrophy, myosin isozymes, pressure overload, pulmonary congestion, sarcoplasmic reticulum

Introduction

Despite progress in the treatment of the pressure overloaded hypertrophied heart, congestive failure cannot be prevented. Current drug targets are linked to neuro-endocrine consequences of an impaired myocardial performance, such as activation of the sympathetic nervous system or renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. Although neuro-endocrine activation induces an adverse remodelling of the extracellular matrix, it appears that it cannot account for the initial stage of the disease (Katz, 1989; Depre et al., 1998; Bristow, 1998; O'Rourke et al., 1999). To examine the possibility that initiating mechanisms are linked to altered gene expression of the cardiomyocyte involving also the myosin heavy chain (MHC) gene and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) genes (Bugaisky et al., 1990; Bristow, 1998; O'Rourke et al., 1999; Schwartz et al., 1992; Feldman et al., 1993; Depre et al., 1998; Minamisawa et al., 1999), we assessed interventions which partially prevent the expression of the characteristic phenotype of a pressure overloaded rat heart (Rupp & Jacob, 1982; Rupp et al., 1992). Because pressure overload of the left ventricle is associated with insulin resistance (Paternostro et al., 1999), a hypoglycemic drug which inhibits mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 (CPT-1) and thereby increases glucose oxidation represents a candidate approach. Previous studies were performed in models of pressure overload in the absence of congestive heart failure (Turcani & Rupp, 1997). The CPT-1 inhibitor etomoxir improved SR function (Rupp et al., 1992, 1995), in vivo heart performance (Turcani & Rupp, 1997) and delayed the dilative ventricular remodelling (Turcani & Rupp, 1999), whereby metabolic signals appear to be involved (Zarain-Herzberg & Rupp, 1999). We addressed, therefore, the hypothesis that etomoxir prevents the transition from compensated to failing hypertrophy via an improved SR Ca2+ uptake rate. We hypothesized also that the hypertrophied heart fails to upregulate the SR Ca2+ uptake rate in a weight proportional manner and that etomoxir counteracts this unfavourable process. Rate of SR Ca2+ uptake was determined in the homogenate to avoid confounding influences arising from the purification procedure. To exclude possible effects of an altered phospholamban phosphorylation and SR Ca2+ release, measurements were performed also under conditions where phospholamban phosphorylation was stimulated by catalytic subunit of protein kinase A or the Ca2+ release channel was inhibited by ruthenium red. To examine whether heart chambers upregulate SR Ca2+ uptake rate in a hypertrophy proportional manner, the experimental rate values of whole chambers were compared with the respective predicted values assuming a hypertrophy proportional increase in activity. For assessing the hypothesis that changes in SR function induced by etomoxir are associated with an altered expression of the contractile protein myosin, the distribution of myosin isozymes was determined at the protein level (Rupp & Jacob, 1982). To monitor the transition from compensated to failing cardiac hypertrophy, rats were examined 8, 10, 14 and 28 weeks after severe constriction of the ascending aorta. The etomoxir treatment (15 mg kg body wt−1 day−1) was started one day post surgery and lasted 10 weeks. The study demonstrates that the transition from compensated to failing hypertrophy can be prevented by increasing the SR Ca2+ uptake rate proportionally to cardiac hypertrophy.

Methods

Experimental animals

Pressure overload of the left ventricle was induced in 80–100 g Wistar/WU rats (Charles-River, Kissleg, Germany) under ketamine (60 mg kg body wt−1) and xylazine (2 mg kg body wt−1) anaesthesia. After endotracheal intubation, rats were ventilated using a rodent respirator (Hugo Sachs, Hugstetten, Germany) and a right lateral thoracotomy (2nd intercostal space) was performed. The ascending aorta was isolated and constricted with a 3-0 silk suture tied against a 0.9 mm blunt steel wire. The constriction was made tighter than reported previously (Turcani & Rupp, 1997). The wire was removed whereby the aorta was constricted to about 70% of the original diameter. Sham-operated rats underwent a right thoracotomy and the aorta was isolated but not banded. Rats were housed at 21–23°C on a 12 : 12 h light/dark cycle. The powdered regular chow (Ssniff of Plange, Soest, Germany) was supplemented with racemic etomoxir ((±)-ethyl 2[6(4-chlorophenoxy)hexyl] oxirane-2-carboxylate) provided by Dr H.P.O. Wolf (Byk Gulden, Konstanz, Germany). The average daily etomoxir intake of 15 mg kg body wt−1 was calculated from food consumption. Sham-operated control rats received a powdered regular chow. Tap water and chow were ad libitum. Handling of rats and experimental procedures were in accordance with the institutional guidelines. Rats were killed by decapitation, hearts were quickly excised and immersed in an ice-cold solution containing 130 mol l−1 NaCl, 30 mmol l−1 KCl and 10 mmol l−1 histidine (pH 7.4). Left ventricular samples were blotted and shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen tissue was stored at −80°C. Preparation of homogenous catalytic subunit (C subunit) of bovine cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (spec. act. 1 unit mg−1 using histone IIa as substrate) was prepared as described (Rupp et al., 1995). Protein was determined according to Lowry et al. (1951) using ovalbumin as standard after incubating samples in 1 mol l−1 NaOH for 30 min.

Preparation of homogenates

Cardiac homogenates were prepared at 4°C. A 20–50 mg specimen of frozen ventricular tissue was placed into 16 vols. of an ice-cold 250 mmol l−1 sucrose, 10 mmol l−1 histidine (pH 7.4) solution and homogenized six times for 10 s with 15 s intervals using a Brinkmann Polytron PT 3000 (Kinematica AG, Littau/Lucerne, Switzerland) set at 25,000 r.p.m.. The final homogenate (60 mg wet tissue wt ml−1) was filtered through polyamide gauze of 90 mesh (neoLab, Heidelberg, Germany). Samples were kept on ice and used within 10 min for measurement of oxalate-supported Ca2+ uptake. Another sample of the homogenate designated for protein phosphorylation was immediately diluted 3-fold in a phosphoprotein protection buffer containing 250 mmol l−1 sucrose, 10 mmol l−1 histidine (pH 7.4), 150 mmol l−1 KH2PO4, 50 mmol l−1 NaF and 30 mmol l−1 EDTA and frozen in liquid nitrogen. For immunochemical and additional phosphorylation experiments, KCl-extracted homogenates were prepared. Tissue homogenates were extracted with 0.6 mol l−1 KCl to remove contractile proteins. The homogenate was first stirred on ice for 20 min in phosphoprotein protection buffer containing 0.6 mol l−1 KCl and then centrifuged at 150,000×g for 10 min in a Beckman TLX-100 desktop centrifuge (rotor 100.3). The pellet was resuspended in 3 ml of the same buffer solution and the centrifugation was repeated. The final pellet was resuspended in 250 mmol l−1 sucrose, 10 mmol l−1 histidine (pH 7.4) to a protein concentration of 1–3 mg ml−1 and frozen in liquid nitrogen. A sample of the KCl-extracted pellet was diluted in 10 mmol l−1 sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) to a final protein concentration of 0.05 mg ml−1 and stored at −20°C until used for immunochemical quantitation of phospholamban. Samples for protein phosphorylation were stored at −80°C.

Oxalate-supported SR Ca2+ uptake

Oxalate-supported SR Ca2+ uptake was measured in homogenates as described (Rupp et al., 1995). Briefly, the Ca2+ uptake medium contained 40 mmol l−1 imidazole (pH 7.0), 100 mmol l−1 KCl, 5 mmol l−1 MgCl2, 5 mmol l−1 TrisATP, 6 mmol l−1 phosphocreatine, 10 mmol l−1 K+-oxalate, 10 mmol l−1 NaN3, 0.2 mmol l−1 EGTA, 0.1 mmol l−1 45CaCl2 (spec. act. 15 d.p.m./pmol) corresponding to 0.21 μmol l−1 free Ca2+ (MAXC program of Dr C. Patton, Stanford University, Hopkins Marine Station, Pacific Grove, CA, U.S.A.) and 3 mg wet heart tissue per ml. The reaction mixture was preincubated without homogenate at 37°C for 2 min. Ca2+ uptake was started by addition of homogenate. At 0.5 min intervals, samples of 0.05 ml were filtered through 0.45 μm ME membrane filters (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany) using a vacuum pump. Filters were washed twice with 3 ml of an ice-cold solution containing 100 mmol l−1 KCl, 2 mmol l−1 EGTA and 40 mmol l−1 imidazole (pH 7.0). The radioactivity associated with dry filters was determined by liquid scintillation counting. The rate of SR Ca2+ uptake was calculated by linear regression of data points obtained between 0.5 and 2.0 min. SR Ca2+ uptake was also measured in the presence of either 2 μmol l−1 C subunit of protein kinase A or 20 μmol l−1 ruthenium red. All measurements were done in duplicate.

Western blot analysis and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

For Western blotting, 100 μg of membrane protein was solubilized at room temperature for 30 min in 1.5% SDS, 62.5 mmol l−1 Tris-Cl (pH 6.8), 7.5% glycerol, 3.8% mercaptoethanol, 0.0005% pyronin and 0.04% bromophenol blue. Proteins were separated by electrophoresis in SDS-polyacrylamide gels (total monomer concentration 7.6%, crosslinking monomer concentration 2.7%). The Laemmli protocol (Laemmli, 1970) was modified by including 4 mol l−1 urea in the gels. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane BA 85 (Schleicher & Schuell) for 1.1 h at a constant voltage of 100 V at 4°C using a Minitransblot cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, U.S.A.) as described (Rupp et al., 1995). Membranes were blocked for 1.5 h at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline containing Tween (TBS-T) (10 mmol l−1 Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 150 mmol l−1 NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) with 3% ovalbumin. Three subsequent washes of 10 min, each in TBS-T, were performed prior to addition of the primary antibodies. For detecting the SR Ca2+ ATPase, membranes (3 μg protein/lane) were first incubated with rabbit SERCA2 antiserum (dilution 1 : 5000; gift of Dr W.H. Dillmann, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) for 1.5 h at room temperature in detergent-free TBS (50 mmol l−1 Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 120 mmol l−1 NaCl) containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.04% NaN3. Afterwards, they were washed twice in TBS-T with 3% ovalbumin for 10 min and finally twice in TBS for 5 min. The nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1 : 5000 in TBS with 0.1% ovalbumin) for 1 h and washed twice in TBS-T and TBS for 10 min, respectively. Immunoreactive SERCA2 was visualized using an enhanced chemoluminescence (ECL) analysis kit (Amersham, Little Chalfont, U.K.) and Kodak X-OMAT AR X-ray film. Exposure time was 1 min. The optical density of the immunoreactive bands was quantified after densitometric scanning using a PDI scanner (Model DNA 35; PDI, Huntington Station, N.Y., U.S.A.). Defined amounts of protein (1 to 10 μg/lane) were used to check the linearity between the amount of applied protein and the intensity of the optical signal. The value of this parameter was considered to reflect the relative amount of SERCA2.

Immunochemical identification of phospholamban by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was carried out as given by (Cernohorsky et al., 1998). A monoclonal anti-phospholamban antibody (Biomol, Hamburg, Germany), that recognized both phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated phospholamban and goat anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugate as a secondary antibody, were used. The detection was performed with 0.1 ml of a peroxidase substrate mixture containing 10 mg o-phenylenediamine, 10 μl 30% H2O2, and 0.2 ml 1 mol l−1 citric acid (pH 4.7) per 10 ml distilled water. The absorbance of the sample was recorded at 492 nM using an Anthos HT II spectrophotometer microtiter plate reader (Anthos Labtec Instruments, Salzburg, Austria).

Myosin isozymes

The proportion of myosin isozymes was determined by non-dissociating polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of pyrophosphate (Rupp & Jacob, 1982). Myosin isozymes were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 and gels were scanned using a Quick Scan densitometer (Helena Laboratories, Beaumont, TX, U.S.A.). Myosin isozymes were quantified by measuring peak heights. Isozymes of less than 5% were quantitated by fitting the isozyme profile to an envelope consisting of three Gaussian curves which were integrated. Because myosin V1 consists of α-MHC, V2 of α,β-MHC and V3 of β-MHC, the proportion of α-MHC (%) was calculated using the equation: α-MHC (%)=0.5 * V2 (%)+V1 (%).

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons between the experimental groups were performed by one-way analysis of variance. If not otherwise indicated, Dunnett's multiple comparison test was used for identifying significant group-to-group differences. Correlations were tested by regression analysis using the least-squares method. Values are mean±s.e.mean. Statistical significance was assumed at P<0.05.

Results

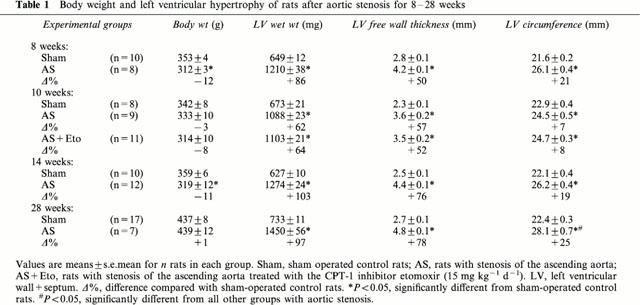

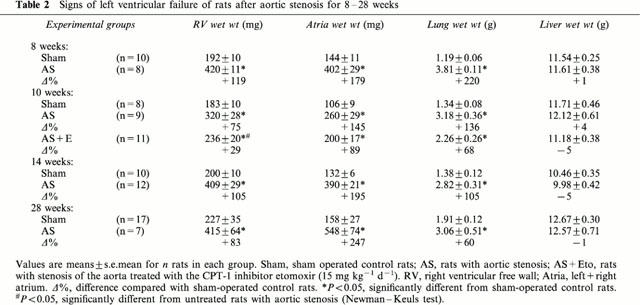

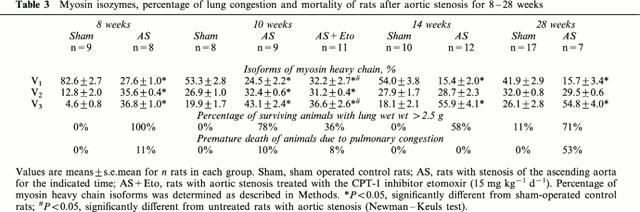

Severe constriction of the ascending aorta for 8 weeks increased left ventricular weight by 86% and wall thickness measured at the point of maximum diameter by 50% (Table 1). The protein content g wet wt−1 of left ventricle was not affected (not shown). Weight of atria increased by 179%, of lung by 220% and of right ventricle by 119%, indicating left ventricular failure (Table 2). Because liver weight was not altered (Table 2), right ventricular failure had not occurred. Extending the duration of pressure overload to 10, 14 and 28 weeks did neither increase left ventricular hypertrophy (Table 1) nor signs of left ventricular failure (Table 2). Because lung weight did not exceed 2.5 g in all sham-operated rats, the occurrence of pulmonary congestion and thus left ventricular failure was assumed at a lung weight greater than 2.5 g. The percentage of surviving rats exhibiting pulmonary congestion was 100% (8 weeks), 78% (10 weeks), 58% (14 weeks) and 71% (28 weeks) (Table 3). After 28 weeks, the left ventricular circumference was increased (P<0.05) demonstrating ventricular dilatation (Table 1). Mortality increased from 11% at 8 weeks to 53% at 28 weeks of pressure overload (Table 3).

Table 1.

Body weight and left ventricular hypertrophy of rats after aortic stenosis for 8–28 weeks

Table 2.

Signs of left ventricular failure of rats after aortic stenosis for 8–28 weeks

Table 3.

Myosin isozymes, percentage of lung congestion and mortality of rats after aortic stenosis for 8–28 weeks

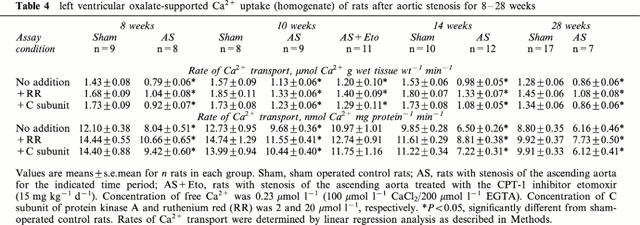

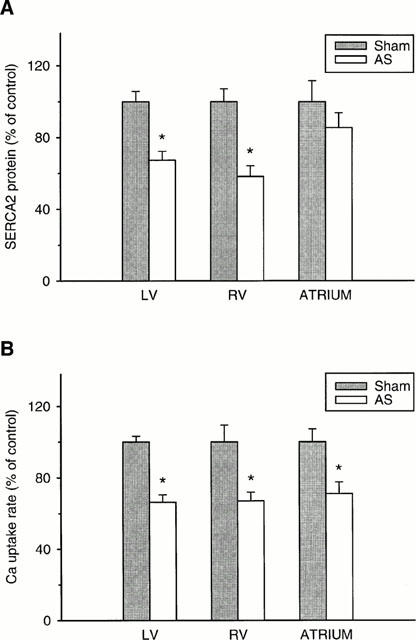

Rate of SR Ca2+ uptake referred either to g wet weight or mg homogenate protein was decreased (P<0.05) in the left ventricle of rats 8 weeks after aortic constriction (Table 4). This depression was also observed when SR Ca2+ uptake was measured in the presence of ruthenium red or catalytic subunit of protein kinase A (Table 4). Extending the duration of pressure overload to 10, 14 and 28 weeks did not further reduce SR Ca2+ uptake rate (Table 4). Equidirectional changes were observed in SR Ca2+ uptake rate and immunoreactive protein level of the SR Ca2+ pump (SERCA2) determined by Western blots (Figure 1). After 8 weeks of aortic banding, the SERCA2 protein was significantly decreased in left and right ventricles and not significantly in atria (Figure 1A). For all untreated rats with 8 to 28 weeks pressure overload, the decline in left ventricular SR Ca2+ uptake rate (Figure 1B) was 29.9±1.8% (P<0.05 vs sham-operated controls). Similarly, left ventricular immunoreactive SERCA2 protein level was decreased by 30.4±0.8% (P<0.05 vs sham-operated controls).

Table 4.

left ventricular oxalate-supported Ca2+ uptake (homogenate) of rats after aortic stenosis for 8–28 weeks

Figure 1.

Percentage changes in (A) the immunoreactive SERCA2 protein and (B) SR Ca2+ uptake rate of left ventricle (LV), right ventricle (RV) and atria due to aortic stenosis (AS) for 8 weeks. Same left ventricular homogenates were used for Western blots and oxalate-supported SR Ca2+ uptake. Values are means±s.e.mean (10 sham-operated control rats and eight untreated AS). SR Ca2+ uptake rates were normalized to the respective value of sham-operated rats (LV: 12.1±0.4; RV: 11.3±1.1; atria: 20.1±1.4 nmol Ca2+ mg tissue protein−1 min−1). *P<0.05, significantly different from respective sham-operated (Sham) value.

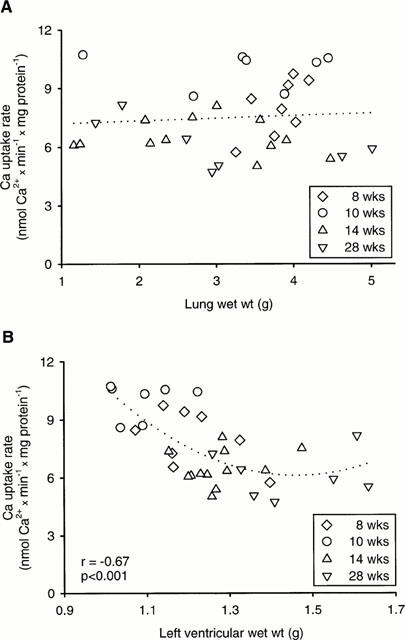

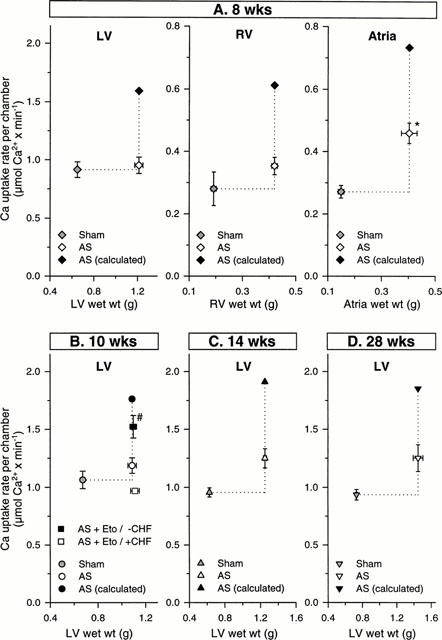

While SR Ca2+ uptake rate was not significantly affected by pulmonary congestion (Figure 2A), it was inversely correlated (P<0.05) with left ventricular weight (Figure 2B). Although the regression appeared not be linear particularly at heart weights exceeding 1.5 g, a hypertrophy proportional decrease in SR Ca2+ uptake rate can be inferred at lower heart weights. Total SR Ca2+ uptake rate was, therefore, calculated for whole ventricles and atria by multiplying the activities (μmol Ca2+ g wet wt−1 min−1) with the respective chamber weights (Figure 3A). SR Ca2+ uptake rates were also predicted assuming a hypertrophy proportional increase in activity (Figure 3A). The SR Ca2+ uptake rate per whole left or right ventricle was not significantly altered after 8 weeks of pressure overload (Figure 3A). The depressed SR Ca2+ uptake rates per g wet wt. can thus be interpreted in terms of a hypertrophy proportional decrease in activity. In atria, total SR Ca2+ uptake rate was increased (P<0.05) but did not reach the predicted value assuming a hypertrophy proportional increase (Figure 3A). Extending the duration of pressure overload to 10, 14 and 28 weeks had no significant effect on SR Ca2+ uptake rate per left ventricle (Figure 3B–D).

Figure 2.

Relationship between SR Ca2+ uptake rate and (A) lung weight and (B) left ventricular weight of untreated rats with aortic stenosis for 8, 10, 14, 28 weeks. Oxalate-supported Ca2+ uptake was measured in left ventricular homogenates (mean values of duplicate determinations). Calculated free Ca2+ concentration was 0.21 μmol l−1. Regression equations: (A) y=0.14 x+7.07; (B) y=10.6 x3–20.7 x2−7.9 x+28.5.

Figure 3.

(A) Total tissue SR Ca2+ uptake rate of left ventricle (LV), right ventricle (RV) and atria of untreated rats with aortic stenosis (AS) for 8 weeks and sham-operated (Sham) rats. Total chamber SR Ca2+ uptake rate was calculated by multiplying the measured Ca2+ uptake rate (μmoles g wet tissue wt−1 min−1) with the respective wet tissue weight. Predicted values for total SR Ca2+ uptake rates were calculated assuming a hypertrophy proportional increase in SR Ca2+ uptake rate. *P<0.05, significantly different from Sham. Values are means±s.e.mean. (B–D) Total tissue SR Ca2+ uptake rate of left ventricle of untreated rats with aortic stenosis (AS) for 10, 14, 28 weeks, etomoxir (Eto) treated rats with AS for 10 weeks and sham-operated (Sham) rats. Predicted values for total SR Ca2+ uptake rates were calculated assuming a hypertrophy proportional increase in SR Ca2+ uptake rate. Values are given for etomoxir-treated rats without (seven out of 11 rats) pulmonary congestion (−CHF; lung wt<2.5 g) and for etomoxir-treated rats with (four out of 11 rats) pulmonary congestion (+CHF; lung wt >2.5 g). #P<0.05, significantly different from untreated rats with aortic stenosis and etomoxir treated rats with pulmonary congestion. Values are means±s.e.mean.

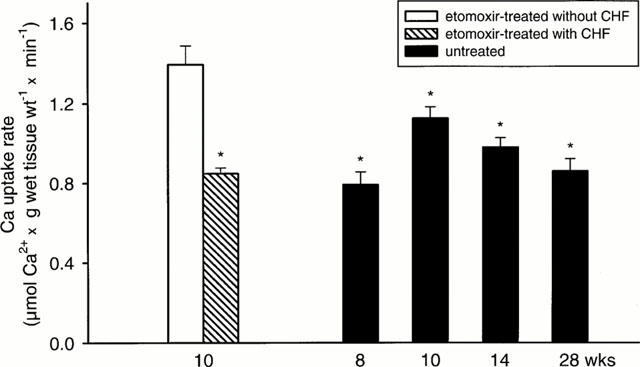

To examine effects of etomoxir, an additional group of rats with 10 weeks pressure overload were treated starting one day post surgery. Left ventricular weight was not altered, however, the right ventricular hypertrophy was decreased (P<0.05) (Table 2). In 64% of etomoxir-treated rats, pulmonary congestion was absent (lung weight >2.5 g) (Table 3) and was associated with a higher (P<0.05) SR Ca2+ uptake rate (Figure 4). The increased SR Ca2+ uptake rate was observed also in the presence of ruthenium red or catalytic subunit of protein kinase A (not shown). The SR Ca2+ uptake rate per whole left ventricle of etomoxir-treated rats was increased (P<0.05) when pulmonary congestion had not occurred (Figure 3B). The predicted activity assuming a hypertrophy proportional increase of SR Ca2+ uptake rate was, however, not reached completely (Figure 3B). In 36% of etomoxir-treated rats, pulmonary congestion had occurred (Table 3) and rate of SR Ca2+ uptake did not differ significantly from untreated rats with aortic stenosis (Figure 4). Thus, only in etomoxir-treated rats a decreased SR Ca2+ uptake rate was diagnostic for the occurrence of pulmonary congestion. In contrast to the etomoxir-treated rats, pulmonary congestion occurred in 78% of untreated rats with aortic constriction.

Figure 4.

Left ventricular SR Ca2+ uptake rate of etomoxir-treated rats (10 weeks) with aortic stenosis and untreated rats with aortic stenosis for 8, 10, 14, 28 weeks. Values are given for etomoxir treated rats without (seven out of 11 rats) pulmonary congestion (−CHF; lung wt<2.5 g) and for etomoxir treated rats with (four out of 11 rats) pulmonary congestion (+CHF; lung wt >2.5 g). *P<0.05, significantly different from etomoxir treated rats without pulmonary congestion. Values are means±s.e.mean.

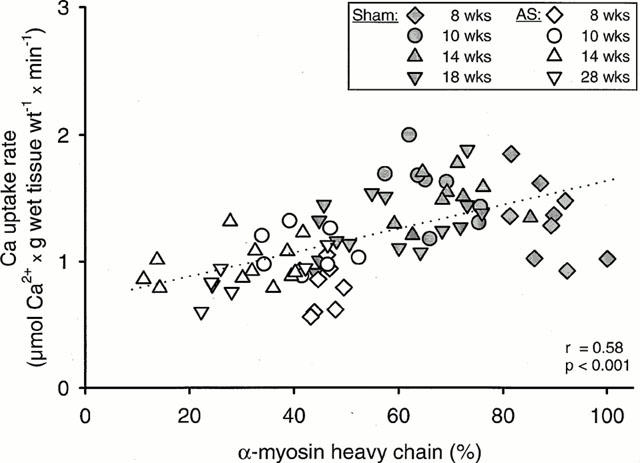

Rate of SR Ca2+ uptake was correlated (P<0.05) with the proportion of α-MHC in untreated sham-operated rats and untreated rats with aortic constriction (Figure 5). In accordance, the proportion of myosin V1 was decreased (P<0.05) in rats with aortic constriction and the proportion of myosin V3 was increased (P<0.05) (Table 3). In etomoxir-treated rats, the proportion of myosin V1 was increased (P<0.05) but did not reach the value of untreated sham-operated rats (Table 3). Similarly to SR Ca2+ uptake rate, the proportion of myosin V1 was decreased (P<0.05) in etomoxir treated rats from 36.7±2.9% to 25.6±4.0% when pulmonary congestion occurred.

Figure 5.

Relationship between the proportion of α-MHC and SR Ca2+ uptake rate of left ventricular homogenates of rats with aortic stenosis (AS) and sham-operated rats (Sham). Values of SR Ca2+ uptake rate are means of duplicate determinations. Regression equation: y=0.0093 x+0.69.

Discussion

Transition to failing left ventricular hypertrophy

Although hypertrophy of the pressure overloaded heart is required for reducing wall stress, it cannot prevent the onset of failure in the case of a sustained severe overload. To address the time-course of the transition from compensated to failing hypertrophy, the ascending aorta was constricted in rats resulting in left ventricular hypertrophy in the range of 62–103%. Signs of pulmonary congestion were observed in 58–100% of rats, whereby the mechanisms underlying the apparent decline with time in the incidence of congestion require further studies. A less severe constriction resulted previously in 39% left ventricular hypertrophy and pulmonary congestion in 10% of rats (Turcani & Rupp, 1997). In the present study, the weight of right ventricles was significantly correlated with lung weight (y=0.083x+0.10, r=0.78, P<0.05) which is another characteristic feature of left ventricular failure. Extending the duration of pressure overload from 8 weeks to 28 weeks did not increase further left ventricular hypertrophy but resulted in a greater left ventricular circumference.

SR Ca2+ uptake rate referred to g wet weight

The present model of left ventricular failure has not been examined with respect to SR Ca2+ uptake rate under the defined conditions of stimulated phospholamban phosphorylation or inhibition of the ryanodine Ca2+ release channel. It has, however, been shown in rats with ascending aortic banding that SR Ca2+ ATPase mRNA abundance was decreased in severely hypertrophied hearts (Feldman et al., 1993; Bruckschlegel et al., 1995). The present study demonstrates that in all rats with left ventricular hypertrophy, the depressed rate of SR Ca2+ uptake was neither affected by the degree of pulmonary congestion nor the process of dilatation. Stimulation of phospholamban phosphorylation by the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A or inhibition of the Ca2+ release channel by ruthenium red did not prevent the depressed SR Ca2+ uptake rate thus excluding the possibility of a decreased phospholamban phosphorylation or an enhanced release of SR Ca2+. Also ELISA-determined immunoreactive phospholamban levels did not differ between aortic banded and sham-operated rats (not shown).

Whole chamber SR Ca2+ uptake

The SR Ca2+ uptake rates per g wet weight were multiplied with the respective chamber weights. Although the total SR Ca2+ uptake rate of normal and hypertrophied left ventricles did not differ significantly, a trend towards increased SR Ca2+ uptake rates was observed at 14 and 28 weeks. Because the number of cardiomyocytes per ventricle is expected to remain constant during cardiac hypertrophy (Zak, 1984) particularly in the absence of marked fibrosis and pulmonary congestion (Turcani & Rupp, 1997) and because chamber hypertrophy is associated with hypertrophy of the cardiomyocyte (Delbridge et al., 1997; Campbell et al., 1991), it can be inferred that SR Ca2+ uptake rate per hypertrophied cardiomyocyte remained unchanged. Furthermore, the similar quantitative changes in SR Ca2+ uptake rate and immunoreactive SERCA2 level suggest that the number of SR Ca2+ pump molecules per cardiomyocyte remained unchanged.

To maintain cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis, the SR has to handle more than 90% of cellular Ca2+ in mammalian hearts (Bers et al., 1993; Negretti et al., 1993). Since in hypertrophied cardiomyocytes the size of the myofilament lattice is increased, more activator Ca2+ is required. If a weight proportional increase in activator Ca2+ is assumed, the number of SR Ca2+ pumps are expected to be raised to a similar extent. If the SR Ca2+ uptake is, however, not increased adequately a reduction in the ‘SR Ca2+ pumping reserve' ensues. Although at low heart rates an inadequate SR function might not be detectable, it could be unmasked at high contraction rates (Morgan, 1991; Hasenfuss et al., 1994). In accordance, targeted overexpression of the SR Ca2+ pump increased cardiac contractile function by increasing SR Ca2+ transport (Baker et al., 1998). The present study shows that pressure overloaded ventricles fail to upregulate the SR Ca2+ uptake rate in a hypertrophy proportional manner. The possibility of such an upregulation is demonstrated by the atria. It can also be concluded that the failure to upregulate the SR Ca2+ uptake rate in a hypertrophy proportional manner represents a defect present already in hypertrophied hearts in the absence of pulmonary congestion.

Effect of etomoxir treatment

The dose of 15 mg kg body wt−1 per day of racemic etomoxir was chosen to affect SR and myosin but not to induce additional cardiac hypertrophy. When the ascending aorta was less severely constricted and signs of left ventricular failure were not observed, this dose did not increase left ventricular weight but raised the developed systolic pressure as well as rate of contraction and relaxation (Turcani & Rupp, 1997). This improved performance was associated with an increased α-MHC expression (Turcani & Rupp, 1997). Because in the present study α-MHC was correlated with SR Ca2+ uptake rate, it can be deduced that an improved heart performance of etomoxir-treated rats (Turcani & Rupp, 1997) could arise also from an enhanced SR function. While left ventricular weight was not affected by etomoxir, the characteristic increase in right ventricular weight due to left ventricular failure was partially prevented. The etomoxir treated rats exhibited also the lowest incidence of pulmonary congestion.

In the absence of pulmonary congestion, etomoxir-treated rats exhibited a higher SR Ca2+ uptake rate compared with etomoxir-treated rats with pulmonary congestion as well as all untreated rats with 8, 14 and 28 weeks pressure overload. Etomoxir increased thus SR Ca2+ uptake rate of hypertrophied ventricles unless heart failure developed. Because in untreated rats with aortic stenosis the SR Ca2+ uptake process appeared to be affected primarily by a hypertrophy proportional dilution of Ca2+ pumping sites, this dilution was apparently less marked in etomoxir treated rats if pulmonary congestion did not occur. It is hypothesized that pulmonary congestion does not develop if SR Ca2+ uptake can be increased in a hypertrophy proportional manner. If this state cannot be reached or maintained, ventricular function deteriorates and pulmonary congestion ensues.

It is a novel finding that CPT-1 inhibition has beneficial effects during progression of left ventricular failure. In favour of this contention is a pilot clinical study in patients with chronic heart failure NYHA II-III (Schmidt-Schweda & Holubarsch, 2000). Patients were treated with etomoxir on top of a standard therapy (ACE-inhibitors, diuretics, digitalis, beta-blockers). Because the clinical status and heart function at maximum exercise were improved by etomoxir, it can be inferred that the drug target of etomoxir is not adequately affected by standard therapy.

It is concluded that the transition from compensated to failing cardiac hypertrophy can be attenuated by inducing a hypertrophy proportional increase in SR Ca2+ transport. Although etomoxir did not completely achieve this target, it represents nonetheless a candidate approach for preventing an inadequate SR function and thus progression of heart failure.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the German Research Foundation (245/7-1, Ve 136/1-3). The expert assistance of Karin Rupp is gratefully appreciated.

Abbreviations

- CPT-1

carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- MHC

myosin heavy chain

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- TBS

tris-buffered saline

- TBS-T

TBS containing Tween

References

- BAKER D.L., HASHIMOTO K., GRUPP I.L., JI Y., REED T., LOUKIANOV E., GRUPP G., BHAGWHAT A., HOIT B., WALSH R., MARBAN E., PERIASAMY M. Targeted overexpression of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase increases cardiac contractility in transgenic mouse hearts. Circ. Res. 1998;83:1205–1214. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.12.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERS D.M., BASSANI J.W., BASSANI R.A. Competition and redistribution among calcium transport systems in rabbit cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993;27:1772–1777. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.10.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRISTOW M.R. Why does the myocardium fail? Insights from basic science. Lancet. 1998;352:SI8–SI14. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)90311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRUCKSCHLEGEL G., HOLMER S.R., JANDELEIT K., GRIMM D., MUDERS F., KROMER E.P., RIEGGER G.A., SCHUNKERT H. Blockade of the renin-angiotensin system in cardiac pressure-overload hypertrophy in rats. Hypertension. 1995;25:250–259. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUGAISKY L.B., ANDERSON P.G., HALL R.S., BISHOP S.P. Differences in myosin isoform expression in the subepicardial and subendocardial myocardium during cardiac hypertrophy in the rat. Circ. Res. 1990;66:1127–1132. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.4.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPBELL S.E., KORECKY B., RAKUSAN K. Remodeling of myocyte dimensions in hypertrophic and atrophic rat hearts. Circ. Res. 1991;68:984–996. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.4.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CERNOHORSKY J., KOLAR F., PELOUCH V., KORECKY B., VETTER R. Thyroid control of sarcolemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and SR Ca2+-ATPase in developing rat heart. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:H264–H273. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.1.H264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DELBRIDGE L.M., SATOH H., YUAN W., BASSANI J.W., QI M., GINSBURG K.S., SAMAREL A.M., BERS D.M. Cardiac myocyte volume, Ca2+ fluxes, and sarcoplasmic reticulum loading in pressure-overload hypertrophy. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:H2425–H2435. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.5.H2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEPRE C., SHIPLEY G.L., CHEN W., HAN Q., DOENST T., MOORE M.L., STEPKOWSKI S., DAVIES P.J., TAEGTMEYER H. Unloaded heart in vivo replicates fetal gene expression of cardiac hypertrophy. Nat. Med. 1998;4:1269–1275. doi: 10.1038/3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FELDMAN A.M., WEINBERG E.O., RAY P.E., LORELL B.H. Selective changes in cardiac gene expression during compensated hypertrophy and the transition to cardiac decompensation in rats with chronic aortic banding. Circ. Res. 1993;73:184–192. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASENFUSS G., REINECKE H., STUDER R., MEYER M., PIESKE B., HOLTZ J., HOLUBARSCH C., POSIVAL H., JUST H., DREXLER H. Relation between myocardial function and expression of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase in failing and nonfailing human myocardium. Circ. Res. 1994;75:434–442. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATZ A.M. Changing strategies in the management of heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1989;13:513–523. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAEMMLI U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O.H., ROSEBROUGH N.J., FARR A.L., RANDALL R.J. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINAMISAWA S., HOSHIJIMA M., CHU G., WARD C.A., FRANK K., GU Y., MARTONE M.E., WANG Y., ROSS J., , JR, KRANIAS E.G., GILES W.R., CHIEN K.R. Chronic phospholamban-sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase interaction is the critical calcium cycling defect in dilated cardiomyopathy. Cell. 1999;99:313–322. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORGAN J.P. Abnormal intracellular modulation of calcium as a major cause of cardiac contractile dysfunction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;325:625–632. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108293250906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEGRETTI N., O'NEILL S.C., EISNER D.A. The relative contributions of different intracellular and sarcolemmal systems to relaxation in rat ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993;27:1826–1830. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.10.1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'ROURKE B., KASS D.A., TOMASELLI G.F., KAAB S., TUNIN R., MARBAN E. Mechanisms of altered excitation-contraction coupling in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure, I: experimental studies. Circ. Res. 1999;84:562–570. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.5.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATERNOSTRO G., PAGANO D., GNECCHI-RUSCONE T., BONSER R.S., CAMICI P.G. Insulin resistance in patients with cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;42:246–253. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUPP H., ELIMBAN V., DHALLA N.S. Modification of subcellular organelles in pressure-overloaded heart by etomoxir, a carnitine palmitoyltransferase I inhibitor. FASEB J. 1992;6:2349–2353. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.6.1531968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUPP H., JACOB R. Response of blood pressure and cardiac myosin polymorphism to swimming training in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1982;60:1098–1103. doi: 10.1139/y82-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUPP H., SCHULZE W., VETTER R. Dietary medium-chain triglycerides can prevent changes in myosin and SR due to CPT-1 inhibition by etomoxir. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:R630–R640. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.3.R630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMIDT-SCHWEDA S., HOLUBARSCH C. First clinical trial with etomoxir in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. Clin. Sci. (Colch) 2000;99:27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWARTZ K., BOHELER K.R., DE LA BASTIE D., LOMPRE A.M., MERCADIER J.J. Switches in cardiac muscle gene expression as a result of pressure and volume overload. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;262:R364–R369. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.3.R364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TURCANI M., RUPP H. Etomoxir improves left ventricular performance of pressure-overloaded rat heart. Circulation. 1997;96:3681–3686. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TURCANI M., RUPP H. Modification of left ventricular hypertrophy by chronic etomixir treatment. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:501–507. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAK R.Overview of the growth process Growth of the Heart in Health and Disease 1984New York: Raven Press; 1–24.ed. Zak R. pp [Google Scholar]

- ZARAIN-HERZBERG A., RUPP H. Transcriptional modulators targeted at fuel metabolism of hypertrophied heart. Am. J. Cardiol. 1999;83:31H–37H. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]