Abstract

In rat mesangial cells extracellular nucleotides were found to increase arachidonic acid release by a cytosolic phospholipase A2 through the P2Y2 purinergic receptor.

In this study we investigated the effects of ATP and UTP on interleukin-1β (IL-1β)-induced mRNA expression and activity of group IIA phospholipase A2 (sPLA2-IIA) in rat mesangial cells.

Treatment of cells for 24 h with extracellular ATP potentiated IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction, whereas UTP had no effect.

We obtained the following evidence that the P2Y2 receptor is not involved in the potentiation of sPLA2-IIA induction: (i) ATP-γ-S had no enhancing effect; (ii) suramin, a P2 receptor antagonist, did not inhibit ATP-mediated potentiation; (iii) inhibition of degradation of extracellular nucleotides by the 5′-ectonucleotidase inhibitor AOPCP did not enhance sPLA2-IIA induction and (iv) adenosine deaminase treatment completely abolished the ATP-mediated potentiation of sPLA2-IIA induction.

In contrast, treatment of mesangial cells with adenosine or the A2A receptor agonist CGS 21680 mimicked the effects of ATP in enhancing IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction, whereas the specific A2A receptor antagonist ZM 241385 completely abolished the potentiating effect of ATP or adenosine.

The protein kinase A inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cyclic AMPS dose-dependently inhibited the enhancing effect of ATP or adenosine indicating the participation of an adenosine receptor-mediated cyclic AMP-dependent signalling pathway.

These data indicate that ATP mediates proinflammatory long-term effects in rat mesangial cells via its degradation product adenosine through the A2A receptor resulting in potentiation of sPLA2-IIA induction.

Keywords: Adenosine A2A receptor, inflammation, interleukin-1β, mesangial cells, nucleotide receptor, secreted phospholipase A2, secretory phospholipase A2

Introduction

Extracellular nucleotides play an important role in the regulation of pathophysiological processes in the kidney. Nucleotides are released into the extracellular space upon injury of glomerular cells and thrombocyte aggregation and may reach high local concentrations (Gordon, 1986). Significant proinflammatory activities of extracellular adenine nucleotides were found during anti-Thy-1-glomerulonephritis, where the percentage of oxygen radical-producing granulocytes was markedly increased in glomeruli after treatment of nephritic rats with ATP-γ-S (Poelstra et al., 1992). Studies in glomerular mesangial cell cultures show multiple mitogenic reactions to ATP or UTP such as activation of phosphatidylinositol-bisphosphate-specific phospholipase C with subsequent increase in inositoltrisphosphate formation and intracellular Ca2+ (Pfeilschifter, 1990; Pavenstädt et al., 1993), activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and synthesis of prostaglandin E2 (Pfeilschifter, 1990) activation of phospholipase D (Pfeilschifter & Merriweather, 1993), activation of the classical p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (Huwiler & Pfeilschifter, 1994) as well as stress-activated protein kinases (Huwiler et al., 1997, 2000). It was suggested that ATP and UTP exert their equipotent actions through a common nucleotide receptor (P2Y2; Pfeilschifter, 1990). Extracellular ATP and UTP stimulate the proliferation of mesangial cells via P2Y receptors (Huwiler & Pfeilschifter, 1994; Harada et al., 2000) raising the possibility that they act as growth factors and may promote mesangial cell proliferation during glomerular diseases (for review, see Schulze-Lohoff et al., 1996).

In contrast to these immediate effects of ATP and UTP little is known about long-term effects of these nucleotides on proinflammatory enzymes, which are induced several hours after cytokine-treatment of mesangial cells. In this respect Mohaupt et al. (1998) described that activation of purinergic P2Y2 receptors by ATP or UTP inhibits 24-h nitrite production which derived from the LPS-stimulated induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase. The inhibition by ATP was shown to be mediated by a PKC-dependent mechanism, as already previously suggested by Mühl & Pfeilschifter (1994).

Another enzyme, which is induced at the transcriptional level in rat mesangial cells, is the group IIA phospholipase A2 (sPLA2-IIA; for review, see Pfeilschifter et al., 1997). Similar to inducible nitric oxide synthase, the expression of sPLA2-IIA is stimulated by proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) or by cyclic AMP-elevating agents such as forskolin and is secreted into the cell culture supernatant of these cells (Walker et al., 1995, 1998; Pfeilschifter et al., 1993, 1997). Both compounds act synergistically in inducing sPLA2-IIA expression. Moreover, we recently described that endogenous NO is a potent mediator of sPLA2-IIA gene transcription (Rupprecht et al., 1999). We also found that sPLA2-IIA is downregulated by PKC-activating compounds such as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) or thrombin as a physiological agonist (Scholz et al., 1999).

Since extracellular nucleotides also activate PKC (Pfeilschifter, 1990; Pfeilschifter & Huwiler, 1996), we expected that ATP or UTP would also inhibit the IL-1β-stimulated induction of sPLA2-IIA. Surprisingly, we found that extracellular ATP as well as adenosine, but not UTP potentiated the cytokine-stimulated induction of sPLA2-IIA. In this study we obtained evidences that extracellular ATP is rapidly degraded to adenosine by 5′-ectonucleotidase and then exerts long-term effects via the A2A adenosine receptor and subsequent activation of the cyclic AMP-mediated pathways.

Methods

Cell culture

Rat renal mesangial cells were cultured as described previously (Pfeilschifter et al., 1984). The cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum, penicillin (100 u ml−1), streptomycin (100 μg ml−1) and bovine insulin (0.66 u ml−1). For experiments cells were cultured in plastic Petri dishes (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany) with 3.5 cm or 10 cm diameter to near confluency. Then cells were incubated for 24 h in serum-free DMEM containing 0.1 mg ml−1 fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA). After this period cells were treated for 24 h with the compounds to be tested.

sPLA2 assay

sPLA2 activity in the supernatant of mesangial cell cultures was determined with [1-14C]-oleate-labelled Escherichia coli as substrate as described previously (Märki & Franson, 1986). Briefly, assay mixtures (1 ml) contained 100 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.0), 1 mM CaCl2, [1-14C]-oleate-labelled E. coli (≈amp;5000 c.p.m.) and 5 μl of the enzyme-containing supernatants of the cell cultures, which is sufficient to produce less than 5% substrate hydrolysis to be in a linear range. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in a thermomixer. The extraction of the lipids was performed by the Dole method exactly as described (Pfeilschifter et al., 1993). Free [1-14C]-oleate was measured in a β-counter.

Northern blot analysis

From confluent mesangial cells cultured in 10 cm diameter culture dishes total cellular RNA was extracted from the cell pellets using the guanidinium isothiocyanate/phenol/chloroform method (Sambrook et al., 1989). Samples of 20 μg of RNA were separated on 1.4% agarose/formaldehyde gels and transferred to a gene screen membrane. After u.v. crosslinking and prehybridization for 4 h the filters were hybridized for 16 h at 42°C to [32P]-labelled cDNA insert from sPLA2-IIA. DNA probes were radioactively labelled with [α-32P]-dCTP by random priming. Finally, the filters were washed twice with 2× sodium chloride (3 M)/sodium citrate (0.3 M; SSC)/0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) for 2×20 min and several times at 65°C with 0.2×SSC/1% SDS. The signal was detected and quantified with a phosphorimager BAS 1500 from Fuji (Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany). To correct for variations in RNA loading the respective cDNA probes were stripped and the blots were rehybridized to the [α-32P]-dCTP-labelled cDNA insert for GAPDH. The amount of mRNA calculated for sPLA2-IIA in IL-1β-stimulated cells is expressed as 100%. The numbers at the top of the Northern blot represent the corrected density expressed as the percentage of RNA found in IL-1β stimulated cells.

Data presentation

The mean of the values of sPLA2-activity measured after IL-1β treatment of mesangial cells was calculated as 100%. The data represent the means of several independent determinations±s.e.mean (n=3) as indicated in the figure legends.

Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t-test to determine significant differences among two groups, or by repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test comparing all concentrations of the respective compounds to be tested with IL-1β plus ATP or plus adenosine. A P<0.05 was defined as significant.

Materials

Recombinant human interleukin-1β was obtained from Cell Concepts (Umkirch, Germany). [1-14C]-oleic acid, and [α-32P]-dCTP were from Amersham-Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany. ATP, UTP, adenosine, adenosine deaminase (EC 3.5.4.4) and Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (Rp-8-bromo-adenosine 3′, 5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate) were from Calbiochem. ZM 241385 (4-(2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl) [1,2,4]triazolo[2,3-a] [1,3,5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol) was provided by Tocris/Biotrend (Köln, Germany), and suramin, AOPCP (α,β-methylene adenosine 5′-diphosphate) and CGS 21680 (2-p-(2-carbocyethyl)phenethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxyamidoadenosine hydrochloride) by RBI/Sigma (München, Germany). Nylon membranes (Gene Sreen) were purchased from NEN Life Science (Köln, Germany). All cell culture media and nutrients were from Gibco BRL (Eggenstein, Germany), and all other chemicals used were from either Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), Sigma (Munich, Germany) or Fluka (Deisenhofen, Germany).

Results

Effect of extracellular ATP and UTP on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA mRNA induction, secretion and activity

Recently we have shown that the PKC-activating compounds thrombin or phorbol ester PMA inhibit IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction (Scholz et al., 1999). ATP and UTP are potent mitogens and activators of PKC in rat mesangial cells (Pfeilschifter & Huwiler, 1996). The scope of this study was to investigate effects of extracellular nucleotides on sPLA2-IIA expression.

In rat mesangial cells sPLA2-IIA is induced at the transcriptional level about 8 h after IL-1β treatment reaching maximal mRNA and protein levels after 24 h (Pfeilschifter et al., 1989; Schalkwijk et al., 1991). Therefore, cells were treated for 24 h with IL-1β in absence or presence of ATP or UTP, each 100 μM, which usually elicits maximal responses in the diverse signal transduction pathways in mesangial cells (Huwiler et al., 2000).

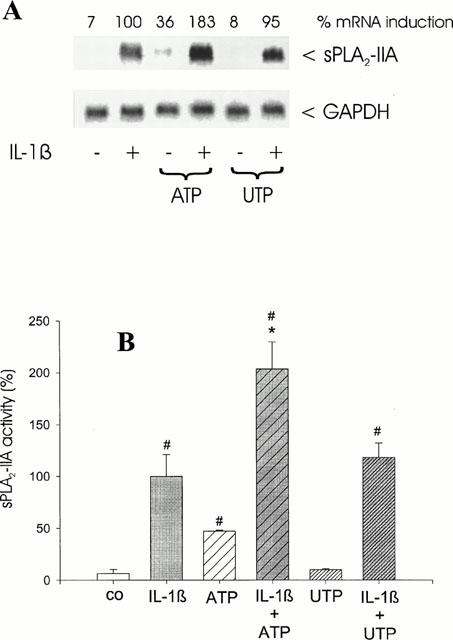

Surprisingly, Northern blot analysis showed that the IL-1β-stimulated induction of sPLA2-IIA mRNA expression was markedly enhanced by ATP, whereas UTP had no potentiating effects (Figure 1A). This Northern blot is representative for five different experiments with similar results. On average the increase in IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA mRNA by 100 μM ATP was 2 fold±0.4 (n=5; P<0.05). ADP and AMP (each 100 μM) had comparable effects (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Effect of ATP and UTP on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction. Mesangial cells were treated for 24 h with ATP or UTP (each 100 μM) in the absence or presence of IL-1β (1 nM) as indicated. (A) Northern blots were performed from the RNA extracts of the cells as described in Methods. To correct for differences in loading, the signal density of each RNA sample hybridized was divided by that hybridized to the GAPDH probe. The amount of mRNA calculated for sPLA2-IIA in IL-1β-stimulated cells is expressed as 100%. The numbers at the top of the Northern blot represent the corrected density expressed as the percentage of RNA found in IL-1β stimulated cells. This is a representative Northern blot out of five separate experiments with comparable results. (B) sPLA2-IIA activity was determined as described in Methods. The means of the values were calculated from five different experiments (n=3). The mean value obtained for IL-1β is indicated as 100%±s.e.mean. Significant differences from control (without stimulation): #P>0.05; ANOVA. Significant differences from IL-1β stimulation (without nucleotide): *P>0.05; ANOVA.

ATP, when given alone, had a stimulatory effect on the mRNA expression of sPLA2-IIA, which was 30%±15 (n=5; P<0.05) of the level reached by IL-1β.

From the cell culture supernatants of these experiments sPLA2 activity assays were performed. Since sPLA2-IIA is the major enzyme secreted by rat mesangial cells (Schalkwjik et al., 1992; Scholz-Pedretti et al., 2000; van der Helm et al., 2000), sPLA2 activity measured in this cell system can be used as a read-out for secreted sPLA2-IIA in the following experiments. In five different experiments it was found that sPLA2-IIA activity was induced after ATP treatment alone by 50±4% of the level reached by IL-1β (n=3; P<0.05). A combination with IL-1β and ATP potentiated sPLA2-IIA activity 2 fold±0.65 (n=3; P<0.01), when compared to IL-1β alone. In contrast, UTP did not change the IL-1β-stimulated effects and had no effects when given alone (Figure 1B). These data correspond to the sPLA2-IIA mRNA expression pattern (Figure 1A).

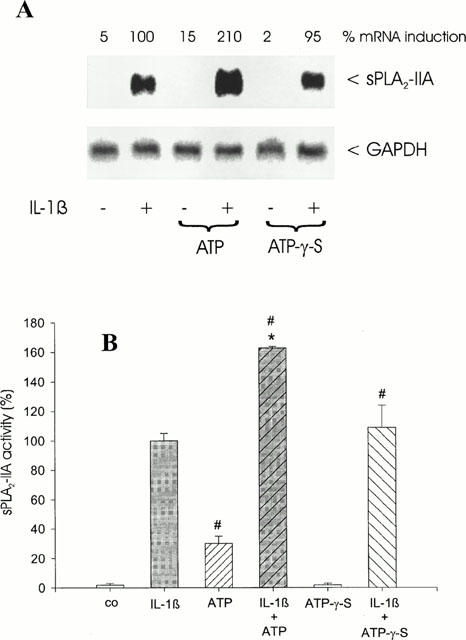

Effect of ATP-γ-S on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction

To test whether a non-hydrolysable analogue of ATP has a similar potentiating effect on sPLA2-IIA mRNA induction and activity, we coincubated mesangial cells for 24 h with ATP-γ-S (100 μM). In contrast to ATP the stable compound ATP-γ-S alone had no effect on sPLA2-IIA induction and did not enhance IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA mRNA expression (Figure 2A) and activity (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Effect of ATP-γ-S on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction. Mesangial cells were treated for 24 h with IL-1β (1 nM) in the absence or presence of ATP (100 μM) or ATP-γ-S (100 μM) as indicated. (A) Northern blot analysis was performed three times with comparable results and quantification was performed as described in Figure 1. This is a representative Northern blot out of three different experiments with comparable results. (B) sPLA2-IIA activity assay was performed as described in Methods. The means of the values were calculated from three different experiments (n=3). The mean value obtained for IL-1β is indicated as 100%±s.e.mean. Significant differences from control (without stimulation): #P>0.05; Student's t-test. Significant differences from IL-1β stimulation (without nucleotide): *P>0.05; Student's t-test.

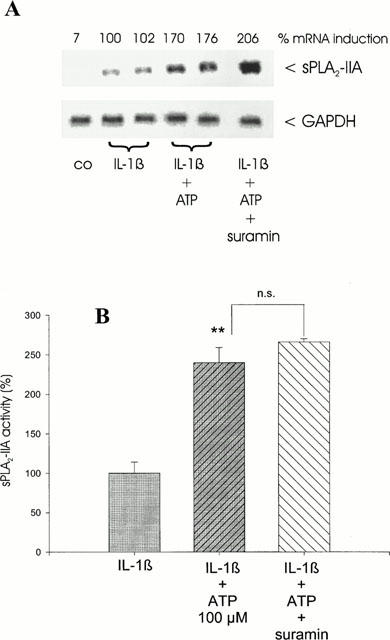

Effect of the P2 receptor antagonist suramin

Suramin, a putative P2 receptor antagonist (Hoiting et al., 1990), was found to almost completely block ATP and UTP-induced activation of the p42/44-MAP kinase (Huwiler & Pfeilschifter, 1994) as well as the p38-MAP kinase cascade (Huwiler et al., 2000). To investigate whether the ATP-induced enhancement of IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction is mediated via P2 receptors, mesangial cells were treated for 24 h with ATP and IL-1β in presence of suramin (100 μM).

The data in Figure 3 show that suramin had no inhibitory effect on the ATP-mediated enhancement of IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA mRNA expression (Figure 3A) and activity (Figure 3B). In some experiments even an enhancement of sPLA2-IIA mRNA induction was observed, which might be due to unspecific actions of suramin (for review, see Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). Suramin had no effects on sPLA2-IIA expression in unstimulated or IL-1β-treated mesangial cells (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effect of suramin on ATP potentiation of IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA expression. Mesangial cells were incubated for 24 h with IL-1β (1 nM) in the absence or presence of ATP (100 μM) or ATP plus suramin (each 100 μM) as indicated. (A) Northern blot analysis was performed three times with comparable results and quantification was performed as described in Figure 1. This is a representative Northern blot out of three different experiments with comparable results. (B) sPLA2-IIA activity assay was performed as described in Methods. The means of the values were calculated from three different experiments (n=3). The mean value obtained for IL-1β is indicated as 100%±s.e.mean. Significant differences from IL-1β stimulation (without nucleotide): **P>0.01; Student's t-test; n.s. – not significant.

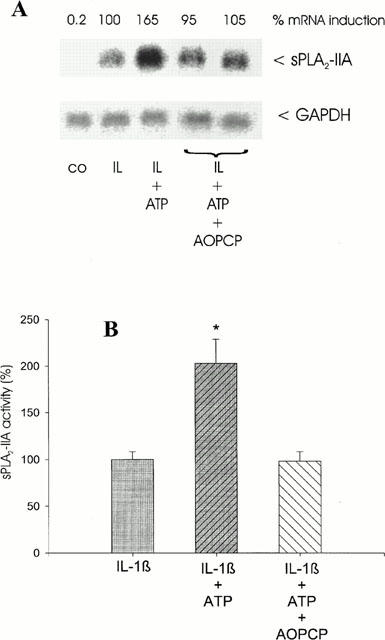

Effect of inhibition of 5′-ectonucleotidase

Mesangial cells express a 5′-ectonucleotidase activity at the cell surface, which rapidly degrades exogenous AMP to adenosine (Le Hir & Kaissling, 1993; Stefanovic et al., 1993). To prevent the formation of adenosine from exogenously added ATP we incubated mesangial cells with AOPCP (100 μM), an inhibitor of 5′-ectonucleotidase activity, thereby inhibiting AMP metabolism to adenosine.

The results show that the treatment of the cells with AOPCP completely abolished the ATP-mediated enhancement of IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA mRNA expression (Figure 4A) and activity (Figure 4B). AOPCP had no effect on sPLA2-IIA expression of unstimulated or IL-1β-treated mesangial cells (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effect of AOPCP on ATP potentiation of IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA expression. Mesangial cells were incubated for 24 h with IL-1β (1 nM) in the absence or presence of ATP (100 μM) or ATP plus AOPCP (100 μM) as indicated. (A) Northern blot analysis and quantification of mRNA expression was performed as described in legend of Figure 1. This is a representative Northern blot out of three different experiments with comparable results. (B) sPLA2-IIA activity was determined in supernatants of mesangial cell cultures. The means of the values were calculated from three different experiments (n=3). The mean value obtained for IL-1β is indicated as 100%±s.e.mean. Significant differences from IL-1β stimulation (without nucleotide): *P>0.05; Student's t-test.

We therefore concluded that the potentiating effect of ATP on sPLA2-IIA induction is not due to a direct ATP action, but is caused by its degradation product adenosine, which exerts its effects via specific adenosine receptors and signalling pathways distinct from ATP (for review, see Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998).

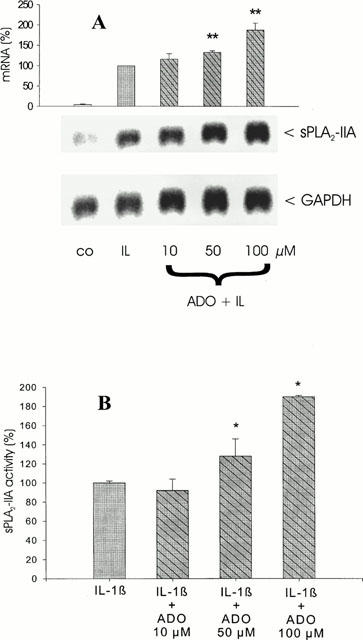

Effect of adenosine on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction

To test if adenosine has a similar potentiating effect as ATP on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction, mesangial cells were treated with different concentrations of adenosine in the presence of IL-1β for 24 h.

Analysis of mRNA induction and activity shows that adenosine concentration-dependently potentiated the IL-1β-stimulated mRNA expression (Figure 5A). In five independent experiments the average increase in sPLA2-IIA mRNA induction was 1.8 fold±0.4; P<0.05). In the same experiments an average increase in sPLA2-IIA activity (Figure 5B) was observed by 1.9 fold±0.35 (n=3; P<0.01). This indicates that adenosine mimicked ATP in enhancing IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction in mesangial cells. Adenosine, when given alone, had a stimulatory effect on sPLA2-IIA by 2.5 fold±1 of control values (P<0.05; n=3; data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effect of adenosine on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction. Mesangial cells were incubated for 24 h with IL-1β (1 nM) in the absence or presence of the indicated adenosine (ADO) concentrations. (A) Northern blot analysis and quantification of mRNA expression was performed as described in legend of Figure 1. This is a representative Northern blot out of four different experiments with comparable results. The bars represent the mean values of mRNA induction (%) from four independent experiments±s.e.mean. The mean value obtained for IL-1β is indicated as 100%±s.e.mean. Significant differences from IL-1β stimulation (without adenosine): **P>0.01; ANOVA. (B) sPLA2-IIA activity was determined in supernatants of mesangial cell cultures. The means of the values were calculated from three different experiments (n=3). The mean value obtained for IL-1β is indicated as 100%±s.e.mean. Significant differences from IL-1β stimulation (without adenosine): *P>0.05; ANOVA.

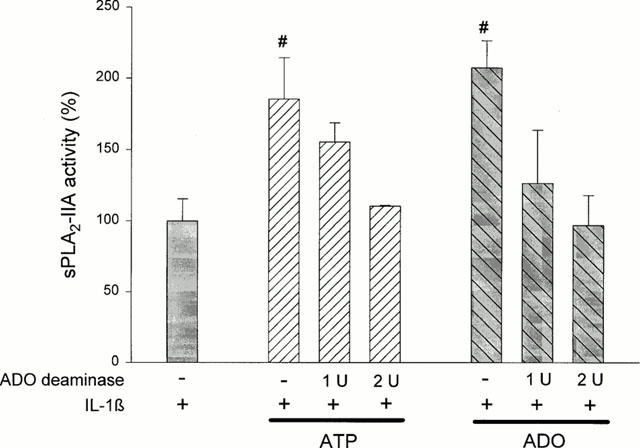

Effect of adenosine deaminase

To confirm that ATP mediates its effects on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction via adenosine, we incubated mesangial cells with IL-1β and ATP in the presence of adenosine deaminase. This enzyme degrades adenosine, which may have arisen from metabolism of ATP. As control we treated the cells with adenosine deaminase in the presence of adenosine. The data in Figure 6 show that adenosine deaminase dose-dependently abolished the potentiating effect of ATP as well as adenosine on IL-1β-induced sPLA2-IIA activity. This observation strongly supports our hypothesis that ATP mediates its effect on sPLA2-IIA induction through its degradation product adenosine. Adenosine deaminase had no effect on sPLA2-IIA expression in unstimulated or IL-1β-treated mesangial cells (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Effect of adenosine deaminase on ATP- or adenosine-mediated potentiation of IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA expression. Mesangial cells were incubated for 24 h with IL-1β (1 nM) in the absence or presence of ATP or adenosine (ADO), (each 100 μM) plus adenosine deaminase (1 or 2 u/ml−1). sPLA2-IIA activity was determined in the cell culture supernatants as described in Methods. The values represent the means of three independent experiments±s.e.mean. (n =3). The mean value obtained for IL-1β is indicated as 100%±s.e.mean. Significant differences from IL-1β stimulation alone: *P>0.05; ANOVA.

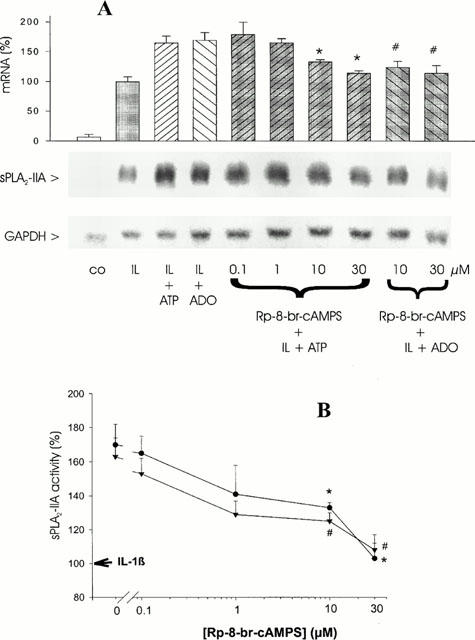

Effect of inhibition of cyclic AMP-mediated signal transduction

Binding of adenosine to A2 receptors of mesangial cells results in activation of adenylate cyclase and subsequent increase in cyclic AMP (Olivera & Lopez-Novoa, 1992). Earlier studies in rat mesangial cells have shown (i) that cyclic AMP induces sPLA2-IIA mRNA induction and (ii) that cyclic AMP acts synergistically with IL-1β in this respect (Walker et al., 1995; Pfeilschifter et al., 1997).

To further support our hypothesis that ATP acts via an A2 receptor-mediated increase in cyclic AMP and subsequent signal transduction via protein kinase A we treated mesangial cells for 24 h with Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, a potent inhibitor of protein kinase A (Gjertsen et al., 1995).

The data in Figure 7 show that Rp-8-Br-cAMPS dose-dependently reduced the synergistic interaction of IL-1β and ATP or adenosine on sPLA2-IIA mRNA expression (Figure 7A) and activity (Figure 7B), reaching the level of IL-1β at 30 μM of the inhibitor. These results demonstrate that ATP and adenosine mediate their potentiating effect on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction via cyclic AMP-activated signal transduction pathways. Rp-8-Br-cAMPS had no effect on sPLA2-IIA expression in unstimulated cells and it did not inhibit IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction (data not shown), thus confirming earlier observations that IL-1β-mediated sPLA2-IIA expression is independent of cyclic AMP-mediated signal transduction (Pfeilschifter et al., 1991).

Figure 7.

Effect of the protein kinase A inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS on ATP- or adenosine-mediated potentiation of IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA expression. Mesangial cells were treated for 24 h with IL-1β (1 nM) in the absence or presence of ATP or adenosine (ADO) and the indicated concentrations of Rp-8-Br-cAMPS. (A) Northern blot analysis and quantification of mRNA expression was performed as described in legend of Figure 1. This is a representative Northern blot out of four different experiments with comparable results. The bars represent the mean values of mRNA induction (%) from four independent experiments±s.e.mean. The mean value obtained for IL-1β is indicated as 100%±s.e.mean. (B) sPLA2-IIA activity was determined in the cell culture supernatants as described in Methods. The values represent the means of three independent experiments±s.e.mean. (n=3). The mean value obtained for IL-1β is indicated as 100%±s.e.mean. Significant differences from corresponding IL-1β plus ATP stimulation (without inhibitor): *P>0.001; ANOVA. Significant differences from corresponding IL-1β plus adenosine stimulation (without inhibitor): #P>0.001; ANOVA.

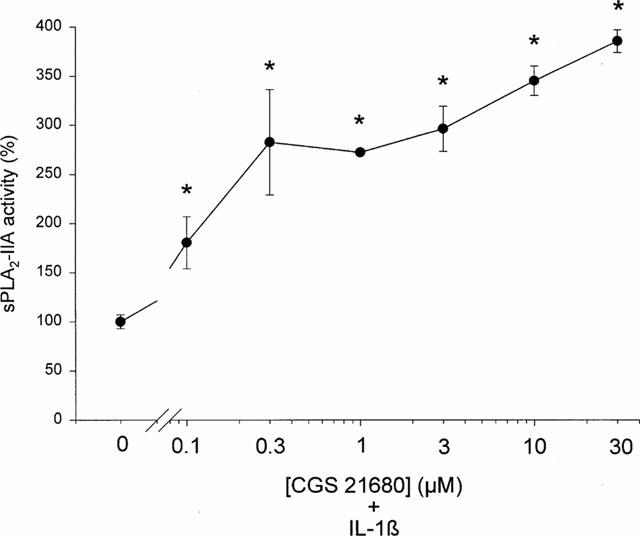

Effect of CGS 21680 as a specific A2A receptor agonist

We next tested CGS21680, which is a 140 fold selective agonist for the A2A receptor subtype versus the A1 receptor (Hutchison et al., 1990) and which binds only with a low affinity to the A2B receptor.

The data in Figure 8 show that CGS21680 dose-dependently enhanced the effect on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA activity thus indicating that in mesangial cells the activation of the A2A receptor subtype may represent the mechanism by which ATP or adenosine mediate their potentiating effects on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction. CGS21680 alone did not induce sPLA2-IIA mRNA induction and activity (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Effect of the specific A2A adenosine receptor agonist CGS 21680 on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2 activity. Mesangial cells were treated for 24 h with IL-1β (1 nM) in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of CGS 21680. sPLA2-IIA activity in the cell culture supernatants was detected as described in Methods. The means of the values were calculated from two different experiments (n=3). The mean value obtained for IL-1β is indicated as 100%±s.e.mean. Significant differences from IL-1β stimulation alone: *P>0.05; ANOVA.

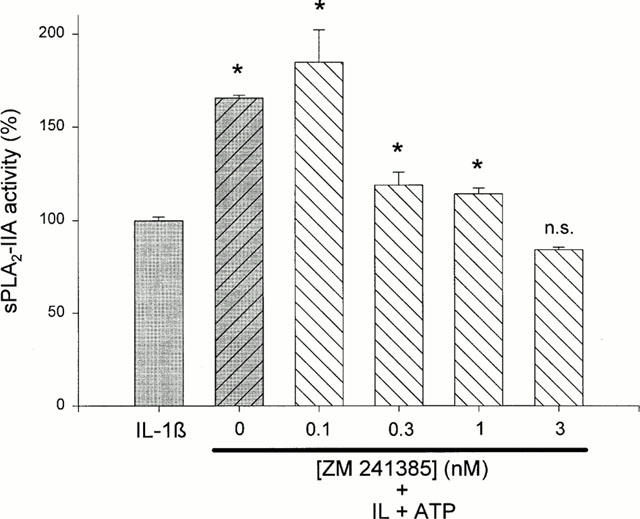

Effect of ZM 241385 as a specific A2A adenosine receptor antagonist

Further support for the involvement of the A2A receptor in the effect of ATP on sPLA2-IIA induction was obtained with ZM 241385, a non-xanthine, selective A2A receptor antagonist (Poucher et al., 1995; Keddie et al., 1996), which dose-dependently reduced the ATP-mediated potentiation of IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA activity reaching the level of IL-1β at 1 – 3 nM (Figure 9). ZM 241385 had no effect on sPLA2-IIA induction in unstimulated or IL-1β-treated mesangial cells (data not shown).

Figure 9.

Effect of the specific A2A adenosine receptor antagonist ZM 241385 on the ATP potentiation of IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA expression. Mesangial cells were incubated for 24 h with IL-1β (1 nM) in the absence or presence of ATP plus ZM 241385 at the indicated concentrations. sPLA2-IIA activity in the cell culture supernatants was detected as described in Methods. The means of the values were calculated from two different experiments (n=3). The mean value obtained for IL-1β is indicated as 100%±s.e.mean. Significant differences from IL-1β stimulation alone: *P>0.05; ANOVA, n.s.–not significant.

Discussion

In this study we have shown for the first time that long-term treatment of rat mesangial cells with extracellular ATP potentiated the IL-1β induction of sPLA2-IIA. At a first glance this result was surprising, since we expected that ATP, which is known to activate PKC in mesangial cells (Pfeilschifter & Huwiler, 1996), would inhibit the induction of sPLA2-IIA. We have shown earlier that activators of PKC drastically reduce IL-1β-stimulated mRNA expression of sPLA2-IIA in mesangial cells (Scholz et al., 1999). In this respect, it was also surprising, that UTP, which shows an equipotent potency to ATP in activating PKC via P2Y2 purinergic receptors (Pfeilschifter, 1990; Pfeilschifter & Huwiler, 1996) had no effect on sPLA2-IIA induction, when coincubated for 24 h with IL-1β. Recently, additional P2 receptor subtypes were described in mesangial cells (Harada et al., 2000). P2Y4, which was shown to be equally sensitive to UTP and ATP (Bogdanov et al., 1998), or P2Y6 (Huwiler et al., 2000), which is activated most potently by UDP, but not by UTP (Nicholas et al., 1996). However, a rapid desensitization of purinergic receptors (Pfeilschifter, 1990), which might be the reason for the lack of an effect of UTP on sPLA2-IIA induction, or consequences of long-term effects of UTP on signal transduction mechanisms in mesangial cells were not investigated so far.

From the fact that ATP potentiated rather than inhibited sPLA2-IIA induction by IL-1β, we inferred that the long-term effects of ATP observed in this study are not primarily mediated via P2 receptor-activated signalling pathways. This was corroborated by the following observations: (i) the non-hydrolysable ATP-analogue ATP-γ-S, which binds to different P2 receptor subtypes, had no potentiating effects on sPLA2-IIA induction; (ii) the P2Y antagonist suramin did not abolish the ATP-mediated potentiation; (iii) the inhibition of 5′-ectonucleotidase activity with AOPCP, which may lead to an accumulation of extracellular AMP, did not potentiate IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction and (iv) treatment of cells with ATP and IL-1β in the presence of adenosine deaminase completely abolished the ATP-mediated potentiation.

Mesangial cells express 5′-ectonucleotidase activity at the cell surface, which represents the major source of extracellular adenosine in the kidney (Stefanovic et al., 1993; Le Hir & Kaissling, 1993). This ATP metabolite acts via adenosine-specific receptors and signalling cascades different from P2 receptors (Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). In mesangial cells the presence of A1 and A2 adenosine receptors was characterized by subtype-specific agonists (Olivera & Lopez-Novoa, 1992; Stefanovic & Valhovic, 1995). The activation of A1 adenosine receptor results in inhibition of adenylate cyclase causing a decrease in cellular cyclic AMP levels, whereas A2 receptors couple via GS to adenylate cyclase and trigger an increase in cyclic AMP. In earlier studies cyclic AMP was shown to stimulate sPLA2-IIA induction in rat mesangial cells and to act synergistically with IL-1β (Pfeilschifter et al., 1991) by using different signalling pathways and transcription factors, which control the induction of the enzyme by cyclic AMP and IL-1β (Walker et al., 1995, 1998; Pfeilschifter et al., 1997; Scholz-Pedretti et al., 2000). Refering to these observations we assumed that most probably the A2 class of adenosine receptors rather than the A1 adenosine receptor is involved in the observed effects on sPLA2-IIA upregulation. Indeed we found a potentiating effect of CGS21680 which is an agonist specific for the A2A adenosine receptor on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction in mesangial cells, thus strongly suggesting that adenosine acts through the A2A adenosine receptor subtype and subsequent cyclic AMP-activated signalling to alter sPLA2-IIA expression. This involves the activation of the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A, which is responsible for phosphorylation and activation of transcription factors critical for the transcriptional regulation of genes in response to cyclic AMP (for review, see Daniel et al., 1998). Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, a potent inhibitor of protein kinase A, blocked the enhancing effects of ATP and adenosine on sPLA2-IIA induction, thus again supporting the involvement of the A2, but not the A1 adenosine receptor in this process.

Further confirmation was obtained in experiments using the specific A2A receptor antagonists ZM 241385, which completely inhibited the ATP potentiation at a concentration of 3 nM (Figure 9).

Interestingly, using the xanthines DMPX (3,7-dimethyl-I-propargylxanthine) or CSC (8-(3-chlorostyryl)caffeine) as putative A2 receptor antagonists we observed an enhancement rather than an inhibition of sPLA2-IIA induction in a concentration range between 10 and 100 μM of these compounds (data not shown). Despite their increased selectivity as A2 receptor antagonists they still may have the potential to inhibit phosphodiesterases, since they belong to the class of xanthates. This inhibition will result in an accumulation of cyclic AMP in amounts sufficient to potentiate the IL-1β-mediated sPLA2-IIA induction. There are very few reports about effects of these xanthate derivatives distinct from their antagonistic effects on A2 adenosine receptors. In this respect Pereira and coworkers (1998) showed that DMPX potentiated the isoproterenol-induced cyclic AMP increase without further discussing a possible mode of action of DMPX in this respect. Such an increase in cyclic AMP levels might be due to an inhibition of phosphodiesterases and thus would explain the synergistic effect of this compound or of CSC on IL-1β-stimulated sPLA2-IIA induction in our system. In contrast, ZM 241385, which is a non-xanthate compound, does not inhibit phosphodiesterases (Poucher et al., 1995; Keddie et al., 1996) and therefore acts exclusively by blocking A2A receptors.

Adenosine as well as A2A agonists were described as potent inhibitors of inflammation in human embryonic kidney cells and in a rat model of ischemia-reperfusion injury (Okusa et al., 1999), as well as in anti-Thy 1 glomerulonephritis in the rat (Poelstra et al., 1992). In addition, adenosine was found to stimulate 5′-ectonucleotidase activity in rat mesangial cells via A2 receptors (Stefanovic et al., 1993) thereby acting as a regulator of ATP levels by degrading elevated amounts of ATP during inflammatory processes in the kidney. Here we describe for the first time, that adenosine is a potent stimulator of the induction of sPLA2-IIA which is a potent proinflammatory enzyme secreted by mesangial cells. This might be crucial for the mitogenic and proinflammatory effects of ATP, which itself is rapidly degraded, but which may act through its metabolite adenosine in long-term potentiation of pathophysiological processes in the glomerulus. Adenosine was described to stimulate proliferation in mesangial cells (MacLaughlin et al., 1997), thus participating in the progression of mitogenic signals induced by extracellular ATP. Moreover, A2A receptor-mediated cyclic AMP-signalling cascades may be involved in induction or potentiation of several other proinflammatory factors in mesangial cells, which are activated by cyclic AMP, such as the inducible nitric oxide synthase (Mühl et al., 1994; Eberhardt et al., 1998), cyclooxygenase 2 (Nüsing et al., 1996; Klein et al., 1998), or interleukin-6 (Dendorfer, 1996). Furthermore, cyclic AMP triggers apoptosis in mesangial cells (Mühl et al., 1996), which may be a critical step in the initiation as well as progression of glomerulonephritis.

Studies in patients with glomerulonephritis have shown a significant decrease of activity of adenosine deaminase in lymphocytes when compared to cells obtained from healthy individuals (Klinger et al., 1983). This may lead to an accumulation of adenosine and subsequent potentiation of proinflammatory cyclic AMP-mediated signal transduction pathways. A recent report shows that adenosine potentiates nitric oxide production via activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in LPS-stimulated macrophages (Min et al., 2000). Moreover, the inhibition of adenosine degradation to inosine may prevent the activation of a negative feed-back mechanism, as inosine was found to inhibit cytokine formation in LPS-stimulated macrophages and thus may represent a potent endogenous antiinflammatory modulator (Hasko et al., 2000).

In summary, ATP seems to exert proinflammatory functions in rat mesangial cells in multiple ways: (i) as a short-lived agonist for P2 receptors activating mitogen- and stress-mediated signalling cascades, and (ii) on a more long-term scale by its degradation to adenosine and subsequent potentiation of sPLA2-IIA expression via A2A receptor-mediated signal transduction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Silke Spitzer for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by a grant of the Wilhelm Sander Stiftung to Kirsten Scholz and Josef Pfeilschifter, and by a grant of the Paul and Cilly Weill-Stiftung to Kirsten Scholz.

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified essential medium

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- NO

nitric oxide

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- sPLA2-IIA

group IIA phospholipase A2

References

- BOGDANOV Y.D., WILDMAN S.S., CLEMENTS M.P., KING B.F., BURNSTOCK G. Molecular cloning and characterization of rat P2Y4 nucleotide receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:428–430. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DANIEL P.B., WALKER W.H., HABENER J.F. Cyclic AMP signaling and gene regulation. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1998;18:353–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.18.1.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENDORFER U. Molecular biology of cytokines. Artif. Organs. 1996;20:437–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1996.tb04529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EBERHARDT W., PLÜSS C., HUMMEL R., PFEILSCHIFTER J. Molecular mechanisms of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression by IL-1β and cAMP in rat mesangial cells. J. Immunol. 1998;160:4961–4969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GJERTSEN B.T., MELLGREN G., OTTEN A., MARONDE E., GENIESER H.G., JASTORFF B., VINTERMYR O.K., MCKNIGHT G.S., DOSKELAND S.O. Novel (Rp)-cAMPS analogs as tools for inhibition of cAMP-kinase in cell culture. Basal cAMP-kinase activity modulates interleukin-1 β action. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:20599–20607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GORDON J.L. Extracellular ATP: effects, sources and fate. Biochem. J. 1986;233:309–319. doi: 10.1042/bj2330309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARADA H, CHAN C.M., LOESCH A., UNWIN R., BURNSTOCK G. Induction of proliferation and apoptotic cell death via P2Y and P2X receptors, respectively, in rat glomerular mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2000;57:949–958. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASKO G., KUHEL D.G., NEMETH Z.H., MABLEY J.G., STACHLEWITZ R.F., VIRAG L., LOHINAI Z., SOUTHAN G.J., SALZMAN A.L., SZABO C. Inosine inhibits inflammatory cytokine production by a posttranscriptional mechanism and protects against endotoxin-induced shock. J. Immunol. 2000;164:1013–1019. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOITING B., MOLLEMAN A., NELEMANS A., DEN HERTOG A. P2-purinoceptor-activated membrane currents and inositol tetrakisphosphate formation are blocked by suramin. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;181:127–131. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUTCHISON A.J., WILLIAMS M., DE JESUS R., YOKOYAMA R., OEI H.H., GHAI G.R., WEBB R.L., ZOGANAS H.C., STONE G.A., JARVIS M.F. 2-(Arylalkylamino)adenosin-5′-uronamides: a new class of highly selective adenosine A2 receptor ligands. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:1919–1924. doi: 10.1021/jm00169a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUWILER A., PFEILSCHIFTER J. Stimulation by extracellular ATP and UTP of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade and proliferation of rat renal mesangial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;113:1455–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17160.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUWILER A., VAN ROSSUM G., WARTMANN M., PFEILSCHIFTER J. Stimulation by extracellular ATP and UTP of the stress-activated protein kinase cascade in rat renal mesangial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:807–812. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUWILER A., WARTMANN M., VAN DEN BOSCH H., PFEILSCHIFTER J. Extracellular nucleotides activate the p38-stress-activated protein kinase cascade in glomerular mesangial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:612–618. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEDDIE J.R., POUCHER S.M., SHAW G.R., BROOKS R., COLLIS M.G. In vivo characterisation of ZM 241385, a selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;301:107–113. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEIN T., ULLRICH V., PFEILSCHIFTER J., NÜSING R. On the induction of cyclooxygenase-2, inducible nitric oxide synthase and soluble phospholipase A2 in rat mesangial cells by a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug: the role of cyclic AMP. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:385–391. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLINGER M., SZEWCZYK Z ROBAK M. Aldolase and adenosine deaminase activity in lymphocytes of patients with glomerulonephritis. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 1983;15:273–279. doi: 10.1007/BF02083015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LE HIR M., KAISSLING B. Distribution and regulation of renal ecto-5′-nucleotidase: implications for physiological functions of adenosine. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:F377–387. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.3.F377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACLAUGHLIN M., MARTINEZ-SALGADO C., ELENO N., OLIVERA A., LOPEZ-NOVOA J.M. Adenosine activates mesangial cell proliferation. Cell. Signal. 1997;9:59–63. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MÄRKI F., FRANSON R. Endogenous suppression of neutral-active and calcium-dependent phospholipase A2 in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1986;879:149–156. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(86)90097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIN H.W., MOOCHHALA S., ENG K.H. Adenosine and its receptor agonists regulate nitric oxide production and RAW 264.7 macrophages via both receptor binding and its downstream metabolites-inosine. Life Sci. 2000;66:1781–1793. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOHAUPT M.G., FISCHER T., SCHWOBEL J., STERZEL R.B., SCHULZE-LOHOFF E. Activation of purinergic P2Y2 receptors inhibits inducible NO synthase in cultured rat mesangial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:F103–110. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.1.F103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MÜHL H., PFEILSCHIFTER J. Possible role of protein kinase C-epsilon isoenzyme in inhibition of interleukin 1 beta induction of nitric oxide synthase in rat renal mesangial cells. Biochem. J. 1994;303:607–612. doi: 10.1042/bj3030607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MÜHL H., KUNZ D., PFEILSCHIFTER J. Expression of nitric oxide synthase in rat glomerular mesangial cells mediated by cyclic AMP. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;112:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13019.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MÜHL H., NITSCH D., SANDAU K., BRÜNE B., VARGA Z., PFEILSCHIFTER J. Apoptosis is triggered by the cyclic AMP signalling pathway in renal mesangial cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;382:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHOLAS R.A., WATT W.C., LAZAROWSKI E.R., LI Q., HARDEN K. Uridine nucleotide selectivity of three phospholipase C-activating P2 receptors: identification of a UDP-selective, a UTP-selective, and an ATP- and UTP-specific receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:224–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NÜSING R.M., KLEIN T., PFEILSCHIFTER J., ULLRICH V. Effect of cyclic AMP and prostaglandin E2 on the induction of nitric oxide- and prostanoid-forming pathways in cultured rat mesangial cells. Biochem. J. 1996;313:617–623. doi: 10.1042/bj3130617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLIVERA A., LOPEZ-NOVOA J.M. Effect of adenosine and adenosine analogues on cyclic AMP accumulation in cultured mesangial cells and isolated glomeruli of the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;107:341–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb12748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKUSA M.D., LINDEN J., MACDONALD T., HUANG L. Selective A2A adenosine receptor activation reduces ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat kidney. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:F404–412. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.3.F404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAVENSTÄDT H., GLOY J., LEIPZIGER J., KLAR B., PFEILSCHIFTER J., SCHOLLMEYER P., GREGER R. Effect of extracellular ATP on contraction, cytosolic calcium activity, membrane voltage and ion currents of rat mesangial cells in primary culture. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;109:953–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEREIRA M.M., LLOYD MILLS C., DORMER R.L., MCPHERSON M.A. Actions of adenosine A1 and A2 receptor antagonists on CFTR antibody-inhibited beta-adrenergic mucin secretion response. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:697–704. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFEILSCHIFTER J. Comparison of extracellular ATP and UTP signalling in rat renal mesangial cells. No indications for the involvement of separate purino- and pyrimidino-ceptors. Biochem. J. 1990;272:469–472. doi: 10.1042/bj2720469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFEILSCHIFTER J., HUWILER A. Regulatory functions of protein kinase C isoenzymes in purinoceptor signalling in mesangial cells. J. Auton. Pharmacol. 1996;16:315–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1996.tb00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFEILSCHIFTER J., MERRIWEATHER C. Extracellular ATP and UTP activation of phospholipase D is mediated by protein kinase C-epsilon in rat renal mesangial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:847–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13890.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFEILSCHIFTER J., KURTZ A., BAUER C. Activation of phospholipase C and prostaglandin synthesis by [arginine]vasopressin in cultures of rat renal mesangial cells. Biochem. J. 1984;223:855–859. doi: 10.1042/bj2230855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFEILSCHIFTER J., LEIGHTON J., PIGNAT W., MÄRKI F., VOSBECK K. Cyclic AMP mimics, but does not mediate, interleukin-1- and tumour-necrosis-factor-stimulated phospholipase A2 secretion from rat renal mesangial cells. Biochem. J. 1991;273:199–204. doi: 10.1042/bj2730199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFEILSCHIFTER J., PIGNAT W., VOSBECK K., MÄRKI F., WIESENBERG I. Susceptibility of interleukin 1- and tumour necrosis factor-induced prostaglandin E2 and phospholipase A2 release from rat renal mesangial cells to different drugs. Biochem. Soc. Transact. 1989;17:916–917. [Google Scholar]

- PFEILSCHIFTER J., SCHALKWIJK C., BRINER V.A., VAN DEN BOSCH H. Cytokine-stimulated secretion of group II phospholipase A2 by rat mesangial cells. Its contribution to arachidonic acid release and prostaglandin synthesis by cultured rat glomerular cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;92:2516–2523. doi: 10.1172/JCI116860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFEILSCHIFTER J., WALKER G., KUNZ D., PIGNAT W., VAN DEN BOSCH H. Phospholipase A2. Basic and Clinical Aspects in Inflammatory Diseases. Prog. Surg. 19972431–37.Uhl W., Nevalainen, T. J., Büchler M. W. (Eds.)Karger, Basel

- POELSTRA K., HEYNEN E.R., BALLER J.F., HARDONK M.J., BAKKER W.W. Modulation of anti-Thy1 nephritis in the rat by adenine nucleotides. Evidence for an anti-inflammatory role for nucleotidases. Lab. Invest. 1992;66:555–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POUCHER S.M., KEDDIE J.R., SINGH P., STOGGALL S.M., CAULKETT P.W., JONES G., COLL M.G. The in vitro pharmacology of ZM 241385, a potent, non-xanthine A2a selective adenosine receptor antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:1096–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RALEVIC V., BURNSTOCK G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUPPRECHT G., SCHOLZ K., BECK K.F., GEIGER H., PFEILSCHIFTER J., KASZKIN M. Cross-talk between group IIA-phospholipase A2 and inducible NO-synthase in rat renal mesangial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:51–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMBROOK J., FROTSCJ J., MANIATIS T. Molecular cloning: a Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- SCHALKWIJK C., PFEILSCHIFTER J., MÄRKI F., VAN DEN BOSCH H. Interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor and forskolin stimulate the synthesis and secretion of group II phospholipase A2 in rat mesangial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991;174:268–275. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90515-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHALKWIJK C., PFEILSCHIFTER J., MÄRKI F., VAN DEN BOSCH H. Interleukin-1β- and forskolin-induced synthesis and secretion of group II phospholipase A2 and prostaglandin E2 in rat mesangial cells is prevented by transforming growth factor-β 2. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:8846–8851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHOLZ K., VLACHOJANNIS G.J., SPITZER S., SCHINI-KERTH V., VAN DEN BOSCH H., KASZKIN M., PFEILSCHIFTER J. Modulation of cytokine-induced expression of secretory phospholipase A2-type IIA by protein kinase C in rat renal mesangial cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;58:1751–1758. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHOLZ-PEDRETTI K., EBERHARDT W., RUPPRECHT G., BECK K.-F., SPITZER S., PFEILSCHIFTER J., KASZKIN M. Inhibition of NF-κB-mediated proinflammatory gene expression in rat mesangial cells by the enolized 1,3-dioxane-4,6-dione-5-carboxamide CGP-43182. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1183–1190. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHULZE-LOHOFF E., OGILVIE A., STERZEL R.B. Extracellular nucleotides as signalling molecules for renal mesangial cells. J. Auton. Pharmacol. 1996;16:381–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1996.tb00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEFANOVIC V., VALHOVIC P. A2 adenosine receptors in human glomerular mesangial cells. Experientia. 1995;51:360–362. doi: 10.1007/BF01928895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEFANOVIC V., VALHOVIC P., SAVIC V., ARDAILLOU N., ARDAILLOU R. Adenosine stimulates 5′-nucleotidase activity in rat mesangial cells via A2 receptors. FEBS Lett. 1993;331:96–100. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80304-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DER HELM H.A., AARSMAN A.J., JANSSEN M.J., NEYS F.W., VAN DEN BOSCH H. Regulation of the expression of group IIA and group V secretory phospholipases A2 in rat mesangial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1484:215–224. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER G., KUNZ D., PIGNAT W., PFEILSCHIFTER J. Platelet-derived growth factor and fibroblast growth factor differentially regulate interleukin 1β- and cyclic AMP-induced group II phospholipase A2 expression in rat renal mesangial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1391:213–222. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER G., KUNZ D., PIGNAT W., VAN DEN BOSCH H., PFEILSCHIFTER J. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate differentially affects cytokine- and cAMP-induced expression of group II phospholipase A2 in rat renal mesangial cells. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:218–222. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00402-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]