Abstract

Evidence is provided for expression and a functional role for phosphodiesterase type V (PDE-V) in the rat isolated small mesenteric artery. The reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT – PCR) demonstrated mRNA for PDE-V, while Western blotting and immunocytochemical studies showed corresponding protein expression. Smooth muscle relaxation to the nitric oxide donor, diethylamine NONOate (DEA NONOate; 1 nM – 10 μM; pEC50=6.7±0.3) was potentiated significantly by the specific inhibitor of PDE-V, 4-[[3,4-(methylenedioxy)benzyl]amino]-6-chloroquinazoline (MBCQ; 1 μM; pEC50=10.5±0.04). These data show that PDE-V is expressed in both the smooth muscle and endothelial cells of a resistance artery, and the enzyme can significantly influence nitric oxide-evoked vasorelaxation.

Keywords: Phosphodiesterase type V, nitric oxide, diethylamine NONOate, mesenteric artery (rat)

Introduction

Sildenafil (Viagra™) a selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE-V), has been shown to be a clinically effective treatment for erectile dysfunction (Boolell et al., 1996). Its action results from increased levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cyclic GMP) which is normally degraded by PDE-V. This cyclic nucleotide is a second messenger for nitric oxide, which is involved in the regulation of numerous functions, including vascular smooth muscle tone (Corbin & Francis, 1999). Reported cardiovascular side effects of sildenafil are typically minor and associated with vasodilatation (headache, flushing and small decreases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure). However, although the incidence is small, serious cardiovascular events, including significant hypotension can occur. Most at risk are individuals taking organic nitrates, commonly prescribed to manage the symptoms of angina pectoris. The coadministration of nitrates and sildenafil significantly increases the risk of potentially life threatening hypotension. The mechanism of this interaction has not been defined. The present study sought to identify the possible expression of PDE type V in a resistance artery and to correlate expression with the effect of a specific inhibitor of this enzyme on the relaxant responses to an exogenously applied NO donor.

Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250 – 300 g) were stunned and killed by cervical dislocation.

RNA isolation and RT – PCR

Small mesenteric arterial segments were dissected, cleaned of fat and connective tissue and snap-frozen prior to isolation of total RNA. Sequence specific sense (5′-ttgaccgacctcttagacc-3′) and antisense (5′-ctacaccaacgacctcttcc-3′) oligonucleotide primers were designed against the published genetic sequences for the rat PDE-V isoform (Kotera et al., 1997). A one tube RT – PCR reaction was carried out on RNA isolated from mesenteric arteries, together with positive and negative controls. Positive controls used rat brain total RNA, whilst negative controls omitted the reverse transcription step. Following reverse transcription at 50°C for 30 min and PCR (94°C, 30 s; 45°C, 30 s; 68°C, 45 s; 40 cycles) reaction products were analysed on a 2% agarose gel, photographed and sequenced (MWG Biotech, U.K.) to confirm their identity.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

Snap-frozen arterial tissue was homogenized in ice-cold buffer (mM: Tris-HCl 20 (pH 7.4), sucrose 250, EDTA 5, dithiothreitol 10) containing a mammalian protease inhibitor cocktail. Rat thoracic aortic homogenate was used as a positive control (Wyatt et al., 1998). Samples of tissue homogenate were then incubated with anti-PDE-V antibody (1 : 1000; 4°C; 12 h), followed by addition of a 10% protein-A sepharose slurry HEPES (50 mM; pH 7.2) (4°C; 3 h). Immunoprecipitates were collected by centrifugation (13,000×g; 10 min) washed three times (50 mM TRIS, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100) and resuspended in 2×Laemmli's buffer containing 2% mercaptoethanol. Samples were resolved by electrophoresis on 8% SDS – PAGE gels and transferred overnight onto PDVF membranes. Briefly, after blocking the residual protein sites on the membrane with 10% low-fat milk in PBS-tween for 12 h at 20°C the membrane was incubated with anti-PDE-V antibody (1 : 1000) in blocking solution. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated, anti-rabbit antibody was used at a 1 : 3000 dilution in blocking solution, followed by detection using an ECL system (Amersham, U.K.).

Immunocytochemistry

Perfused fixed rat mesenteric arteries were kindly provided by Prof N.J. Severs, prepared according to the methodology of Yeh et al. (1997) at a fixation pressure of 76.6 mmHg. Arteries were embedded and thin tissue sections (10 μM) cut using a cryomicrostat and thaw mounted onto glass slides. Arterial sections were incubated with either rabbit anti-PDE-V antibody (1 : 1000), rabbit anti-von Willebrand factor (1 : 800) or mouse monoclonal anti-smooth muscle α-actin (1 : 400). Excess antibody was removed by washing with PBS prior to incubation with tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC) labelled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1 : 200 in PBS) or 9-amino-6-chloro-2-methoxyacridine (AMCA) labelled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1 : 200 in PBS). Tissue sections were viewed using an inverted Leica TCS-NT confocal laser scanning microscope with oil immersion lens (×63; Cell Imaging Facility, University of Bristol). Autofluorescence was visualized by excitation at 450 – 490 nm and detection at 515 nm, TRITC-labelled antibodies were visualized by excitation at 515 – 560 nm and detection at 590 nm, and AMCA-labelled secondary antibody was visualized by excitation at 340 – 380 nm and detection at 425 nm.

Tension measurements

Segments of third order mesenteric artery (ID100=239±7.0 μM; n=20) were mounted in a Mulvany-Halpern myograph under normalized tension for isometric recording, as described previously (Waldron & Garland, 1994). Tissues were maintained at 37°C in oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) Krebs buffer of the following composition (mM): NaCl 119; KCl, 4.7; CaCl2, 2.5; MgCl2, 1.2; NaHCO3, 25.0; KH2PO4, 1.18 and glucose, 11. All experiments were performed in the presence of indomethacin (2.3 μM).

Chemicals

Total RNA was isolated using SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega, U.K.) and subsequent RT – PCR performed using Titan™ One Tube RT – PCR System (Roch, U.K.). Unless stated otherwise reagents for Western blotting were purchased from Sigma, U.K. Antibodies: rabbit anti-PDE-V antibody, CalBioChem, U.K.; rabbit anti-von-Willebrand factor antibody, mouse monoclonal anti-smooth muscle α-actin antibody and TRITC-goat anti-rabbit, Sigma, U.K.; and AMCA-goat anti-mouse, Molecular Probes, U.K. In functional studies the following chemicals were used: diethylamine NONOate, CalBioChem, U.K.; phenylephrine hydrochloride, Sigma, U.K.; 4-[[3,4-(methylenedioxy)benzyl]amino]-6-chloroquinazoline, Tocris U.K.; 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one Tocris U.K. All other chemicals were obtained from BDH.

Statistical analysis

Relaxation responses are expressed as a percentage of phenylephrine-induced tone (3 – 6 μM). Under all conditions, phenylephrine contraction was adjusted to give the same level of contractile tone as the control response. Data are expressed as a mean±s.e.mean. Statistical analysis was performed using the paired Students t-test, with a rejection of the null hypothesis at P>0.05.

Results

Expression of PDE-V RNA and protein

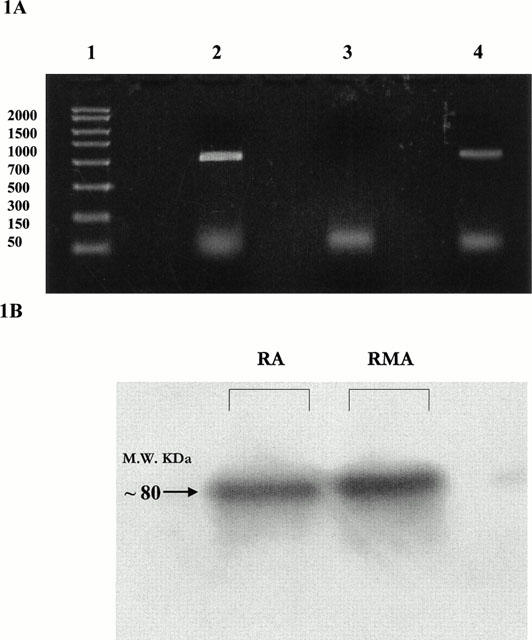

RT – PCR using PDE-V specific oligonucleotide primers demonstrated expression of PDE-V mRNA in total RNA extracts from rat whole brain (n=6; positive control) and isolated mesenteric artery (n=6 where each represents 20 pooled arterial segments). Figure 1A shows a typical gel. Confirmation of PCR product identity was obtained by sequencing (MWG, U.K.) and subsequent alignment with the published sequence for PDE-V (Kotera et al., 1997). Kotera et al. (1999) and Lin et al. (2000) have recently reported the transcriptional regulation of PDE-V, which results in the production of three N-terminal splice variants. The primers used in this study, however, do not distinguish between the expression of splice variants. Expression of PDE-V was further demonstrated using a PDE-V-specific antibody. The anti-PDE-V antibody recognized a protein of ∼80 kDa in rat aorta (positive control) and mesenteric artery homogenates (n=3). A typical immunoblot is shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

(A) Ethidium-bromide stained agarose gel showing reaction products from RT – PCR using PDE-V specific primer pairs. Lanes 1: DNA base pair ladder; 2: Rat mesenteric artery; 3: Rat mesenteric artery, −ve control; 4: Rat brain positive control. (B) Western blot showing protein expression of PDE-V in rat aorta (RA) and rat small mesenteric artery (RMA).

Immunocytochemical demonstration of PDE-V expression

Immunocytochemical staining of arterial segments showed anti-PDE-V antibody binding to protein expressed in both vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cell layers (Figure 2A,B). Smooth muscle and endothelial cell layers were identified by immunocytochemical staining with antibodies raised against smooth muscle α-actin and endothelial cell specific von-Willebrand factor (Figure 2C). Elastic tissue was visualized as autofluorescence.

Figure 2.

(A) and (B) Immunocytochemical staining of arterial segments showing PDE-V distribution in arterial sections from the rat small mesenteric artery at a low (A) and high (B) magnification. (i) Connective tissue of the internal elastic lamina exhibited strong autofluorescence (green). (ii) Binding of the anti-PDE-V specific antibody to endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cell layers was viewed by a TRITC-labelled secondary antibody (red). (iii) Overlay of images (i) and (ii). (C) Immunocytochemical staining of arterial segments showing the histological location of smooth muscle and endothelial cells using antibodies to the smooth muscle-specific α-actin (blue) and endothelial cell-specific von-Willebrand factor (red).

Relaxant effect of the PDE-V inhibitor MBCQ

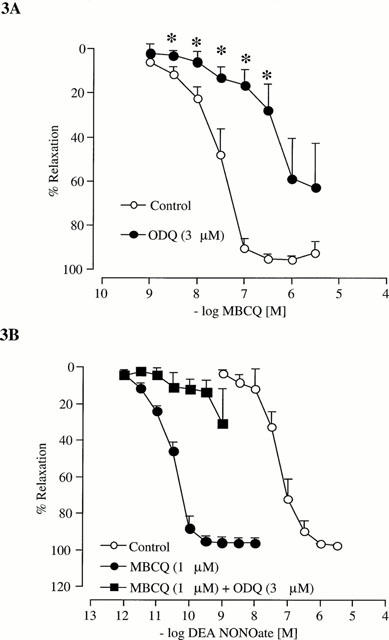

Figure 3A shows that MBCQ-evoked concentration-dependent relaxation of phenylephrine-stimulated, endothelium-intact arterial segments (n=6; pEC50=7.5±0.2), which was attenuated significantly (P<0.05) by pre-incubation with the inhibitor of soluble guanylyl cyclase, ODQ (3 μM; 10 min).

Figure 3.

(A) Concentration-response curves for relaxation of tone in the endothelium-intact rat isolated small mesenteric artery by MBCQ (n=6). (B) Concentration-response curves for relaxation of tone in the endoethelium-intact rat isolated small mesenteric artery by DEA NONOate (n=4). Relaxation is expressed as a percentage of phenylephrine-induced tone and data are shown as mean±s.e.mean from n experiments, *P<0.05 compared to control values.

Effect of MBCQ on diethylamine NONOate-evoked relaxation

The nitric oxide donor, DEA NONOate (0.001 nM – 1 μM), evoked concentration-dependent relaxation of endothelium-intact arterial segments (n=4; pEC50=6.7±0.3) Figure 3B, which was potentiated significantly by pre-incubation with MBCQ (1 μM; n=4; pEC50=10.5±0.04; P<0.05 for between the pEC50 values). Furthermore, the potentiation was reversed by ODQ (3 μM; n=4).

Discussion

Our data show qualitative expression of PDE-V at the messenger RNA and protein level in resistance arteries, the major determinants of peripheral resistance and hence, blood pressure. Furthermore, the immunocytochemical data presented demonstrate for the first time that PDE-V expression is not confined to the vascular smooth muscle cell layer but is also expressed in the endothelium. In contrast, previous investigations have relied on isolating and distinguishing enzyme activity based on sensitivity to pharmacological inhibitors (Komas et al., 1991).

The novel inhibitor of PDE-V, MBCQ has little effect on the enzyme activity of other phosphodiesterase isoforms (Takase et al., 1994). In our studies, the ability of ODQ, an inhibitor of soluble guanylyl cyclase, to reverse MBCQ-evoked relaxation confirmed that basal, or possibly phenylephrine-stimulated cyclic GMP synthesis (Fleming et al., 1999), is mediated by the stimulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Furthermore, the significant potentiation of NO-evoked relaxation by an inhibitor of PDE-V clearly indicates an important role for this enzyme in the response of a resistance artery to NO-based vasodilators. In addition, the ability of ODQ to reverse the potentiation demonstrates MBCQ is acting to prolong the effects of cyclic GMP elborated by NO-mediated stimulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. These data, showing potent modulatory effects of a PDE-V inhibitor on vasodilator properties of mesenteric resistance arteries, is important in the consideration of phosphodiesterase inhibitors therapeutically in circulatory disorders (Wagner et al., 1997) and erectile dysfunction (Boolell et al., 1996).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Wellcome Trust. L.J. Sampson was supported by an MRC studentship.

Abbreviations

- cyclic GMP

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- DEA NONOate

diethylamine NONOate

- MBCQ

4-[[3,4-(methylenedioxy)benzyl]amino]-6-chloroquinazoline

- PDE-V

phosphodiesterase type 5

References

- BOOLELL M., GEPI-ATTEE S., GINGELL J.C., ALLEN M.J. Sildenafil, a novel effective oral therapy for male erectile dysfunction. Br. J. Urol. 1996;78:257–261. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.10220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORBIN J.D., FRANCIS S.H. Cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase-5; Target of sildenafil. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;275:13729–13732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLEMING I., BAUERSACHS J., SCHAFFER A., SCHOLZ D., ALDERSHVILE J., BUSSE R. Isometric contraction induces the Ca2+-independent activation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:1123–1128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOMAS N., LUGNIER C., ANDRIANTSITOHAINA R., STOCLET J.-C. Characterization of cyclic-nucleotide phosphodiesterases from rat mesenteric artery. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;208:85–87. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(91)90056-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOTERA J., FUJISHIGE K., IMAI Y., KAWAI H., AKATSUKA H., YANAKA N., OMORI K. Genomic origin and transcriptional regulation of two variants of cGMP-binding cGMP-specific phosphodiesterases. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;262:866–872. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOTERA J., YANAKA N., FUJISHIGE K., IMAI Y., AKASUKA H., ISHIZUKA T., KAWASHIMA K., OMORI K. Expression of rat cGMP-binding cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase mRNA in Purkinje cell layers during postnatal neuronal development. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;249:434–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN C.-S., LAU A., TU R., LUE T.F. Identification of three alternative first exons and and intronic promoter of human PDE5A gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Com. 2000;268:628–635. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKASE Y., SAEKI T., WATANABE N., ADACHI H., SOUDA S., SAITO I. Cyclic-GMP phosphodiesterase inhibitors 2. Requirement of 6-substitution of quinazoline derivatives for potent and selective inhibitory activity. J. Med. Chem. 1994;37:2106–2111. doi: 10.1021/jm00039a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAGNER R.S., SMITH C.J., TAYLOR A.M., RHOADES R.A. Phosphodiesterase inhibition improves agonist-induced relaxation of hypertensive pulmonary arteries. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeutics. 1997;282:1650–1657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALDRON C.J., GARLAND C.J. Contribution of both nitric oxide and a change in membrane potential to acetylcholine-induced relaxation in the rat small mesenteric artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;112:831–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WYATT T.A., NAFTILAN A.J., FRANCIS S.H., CORBIN J.D. ANF elicits phosphorylation of the cGMP phosphodiesterase in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;43:H448–H455. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.2.H448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YEH H.-I., DUPONT E., COPPEN S., ROTHERY S., SEVERS N.J. Gap junction localization and connexin expression in cytochemically identified endothelial cells of arterial tissue. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1997;45:539–550. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]