Abstract

We have measured the contractile activities and relative potencies (EC50s) of six thrombin PAR1 receptor-derived receptor-activating peptides (PAR-APs): AparafluroFRChaCit-y-NH2 (Cit-NH2); SFLLRNP(P7); SFLLRNP-NH2 (P7-NH2); SFLLR (P5); SFLLR-NH2 (P5-NH2); TFLLR-NH2 (TF-NH2) and a PAR2 receptor activating peptide [SLIGRL-NH2 (SL-NH2)] (a) in a guinea-pig lung peripheral parenchymal strip preparation and (b) in a gastric longitudinal smooth muscle preparation.

The relative potencies of the PAR-APs in the lung preparation (Cit-NH2≅TF-NH2≅P5-NH2>P7≅P5≅P7-NH2; SL-NH2 not active) differed appreciably from their relative potencies in the gastric preparation: Cit-NH2≅TF-NH2≅P7-NH2≅P5-NH2>P7≅percnt;SL-NH2.

The contractile actions of the PAR1-selective peptide, TF-NH2 in the gastric preparation were entirely dependent on extracellular calcium and were blocked by tyrosine kinase inhibitors (genistein, tyrphostin 47/AG213, PP1) and by the cyclooxygenase inhibitor, indomethacin, whereas in the lung preparation, the PAR1-mediated contractile response was only partially dependent on extracellular calcium and was refractory to the actions of either tyrosine kinase inhibitors or indomethacin.

Partial sequencing of the PAR cDNAs detected by RT – PCR both in whole lung and in the peripheral parenchymal strip bioassay tissue demonstrated the presence of both PAR1 and PAR2 mRNA; the expression of PAR2 was detected by immunohistochemistry.

The data point to the presence of distinct receptor systems for the PAR1-APs in guinea-pig lung parenchymal and gastric smooth muscle and indicate that PAR2 does not regulate contractile activity in peripheral parenchymal guinea-pig lung tissue

Keywords: Lung, protease, PAR1, PAR2, smooth muscle

Introduction

In addition to activating proteolytic enzyme cascades (e.g. coagulation caused by thrombin), proteinases such as thrombin, trypsin, tryptase and cathepsin G are now known to regulate target tissues via the proteolytic activation of cell surface G-protein-coupled receptors. At this point in time, four members of this unique proteinase-activated receptor (PAR) family have been cloned (PARs 1 – 4: Vu et al., 1991; Rasmussen et al., 1991; Nystedt et al., 1994; Ishihara et al., 1997; Xu et al., 1998; Kahn et al., 1998; Reviews: Coughlin, 2000; Dery et al., 1998; Hollenberg, 1999). A novel feature of the PARs is their mechanism of activation that involves the proteolytic unmasking of a ‘tethered' N-terminal receptor activating sequence (Vu et al., 1991). Except for PAR3, short synthetic peptides modeled on the revealed tethered ligand sequences are able to activate the PARs (so-called PAR-activating peptides or PAR-APs). In our own work, we have developed a number of PAR-selective receptor-activating peptide agonists and we have evaluated the originally described thrombin PAR1 receptor-activating peptides (TRAPs) for their selectivity for PAR1 compared with PAR2 (Kawabata et al., 1999). With the PAR-APs it has proved possible to assess the effects of selective PAR activation in a variety of intact tissues ranging from neurons (Corvera et al., 1999) to the vasculature and gastrointestinal tract (Muramatsu et al., 1992; Saifeddine et al., 1996; Tay-Uyboco et al., 1995). Relatively recently, attention has begun to focus on the potential roles that the PARs may play in pulmonary pathophysiology (Cocks et al., 1999; Cocks & Moffatt, 2000; Akers, et al., 2000; Lan et al, 2000).

In the lung, several studies have pointed to a potential role for PAR2 in asthma (Cocks et al., 1999; Akers et al., 2000; Lan et al., 2000). In one study (Lan et al., 2000), both contractile and relaxant responses have been observed for PAR-APs derived from PARs 1, 2 and 4 in murine tracheal smooth muscle preparations that were precontracted with 1 μM carbachol. The predominant response of the tracheal preparations was an indomethacin-blocked transient relaxation, in keeping with the hypothesis that epithelial-derived prostanoids may play a bronchoprotective role in asthma (Cocks et al., 1999; Cocks & Moffatt, 2000). Although tracheal smooth muscle segments are frequently used to assess broncho-active agents, previous work has shown that the tracheal preparation need not reflect the responsiveness of alveolar contractile elements, which are of primary importance in regulating pulmonary function (Drazen & Schneider, 1977). Since we were interested in studying the action of PAR1- and PAR2-APs on the alveolar smooth muscle elements and terminal bronchioles, we used a parenchymal strip preparation instead of more conventional tracheal or bronchial tissue strips for our study. We selected the guinea-pig as a source of tissue: (1) because this species is frequently used as a model for airway diseases such as asthma and (2) because we have previously assessed in depth the responsiveness of guinea-pig and rat gastric longitudinal smooth muscle (LM) preparations towards PAR1 and PAR2 activating peptides (Zheng et al, 1998; Al-Ani et al., 1995; Saifeddine et al., 1996). In a preliminary study, we had observed that the nonselective PAR-AP, SFLLR-NH2 (P5-NH2), caused a robust contractile response in both guinea-pig and rat lung parenchymal strips (Mandhane et al., 1995). It was the main aim of the study we report here: (a) to use a more extended library of PAR1APs, including PAR1-selective agonists, and a selective PAR2AP to evaluate the PAR1 and PAR2 receptor systems present in the lung parenchymal smooth muscle preparation and (b) to compare the results obtained using the lung tissue with structure-activity relationships and signal transduction pathways observed for the same series of peptides in the gastric LM preparation; with which we were already familiar (Muramatsu et al., 1988; Hollenberg et al, 1993; Al-Ani et al., 1995; Yang et al., 1992; Zheng et al. 1998).

Methods

Bioassay preparations and assay procedures

All procedures were conducted according to the recommendations of the Canadian Council on Animal Care, concerning animal experimentation, as approved by an institutional committee for animal care. Hartley strain male guinea-pigs (250 – 400 g) were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and the thoracic cavity was opened. The animal was then immediately anticoagulated by the intracardiac administration (right ventricle) of heparin [5 ml of 1 mg ml−1 heparin (174 Units/ml, ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora OH, U.S.A.) in physiological saline] followed by perfusion of the lung (as evidenced by blanching) via the right ventricle with Krebs-Henseleit buffer pH 7.4, of composition (mM): NaCl, 115; KC1, 4.7; CaCl2, 2.5; MgCl2, 1.2; NaHCO3, 2.5; KH2PO4, 1.2 and glucose, 10. Lungs were then removed en block and parenchymal strips were cut (about 2×10 mm) from the peripheral edge of each blanched pulmonary lobe preparation. This tissue contained mainly parenchymal elements, with few scattered terminal bronchioles and very few vascular structures (see Results). Strips were suspended in a 4 ml plastic organ bath maintained at 37°C and gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2. Tissue was subjected to a tension of 0.5 mN (determined to be optimal for response monitoring) and contractile force was recorded isometrically, using Grass or Statham force-displacement transducers. Identical lung strips were obtained for fixation and histological staining as well as for the preparation of RNA. The gastric longitudinal muscle strips were prepared as outlined elsewhere (Muramatsu et al., 1988; Yang et al., 1992; Hollenberg et al., 1993) and were used for bioassay. Isometric contractile responses to the receptor-derived peptides were monitored in the LM prepration as described previously (Muramatsu et al., 1988; Yang et al., 1992) under a tension of 1 mN. Agonists were added to the organ bath at 25 – 30-min intervals, and tension was allowed to develop over a 5 – 10 min time period, followed by washing the tissue and re-equilibration in fresh buffer. To monitor the response of tissues in the absence of extracellular calcium, the preparations were washed once with calcium-free Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing 0.2 mM EGTA (5 min) and were equilibrated in calcium-free buffer containing 0.2 mM EGTA for a further 5 min prior to exposure of the tissues to agonists. Contractile responses were expressed as a percentage (% KCl) of the response of the tissue to 50 mM KCl (in complete calcium-containing buffer). Values reported for the concentration-effect curves or for the histograms represent the means (±s.e.mean, bars in figures) for measurements done with 4 – 10 individual tissue preparations coming from three or more different animals. Receptor-activating peptides based on the human PAR1 sequence: SFLLR-NH2 (P5-NH2), SFLLR (P5), SFLLRNP-NH2 (P7-NH2), SFLLRNP (P7), TFLLR-NH2 (TF-NH2) and AparafluroFRChaCit-y-NH2 (Cit-NH2) and on the rat PAR2 sequence: SL1GRL-NH2 (SL-NH2), were prepared by standard solid phase synthesis procedures by the core peptide synthesis laboratory at the University of Calgary Faculty of Medicine, Calgary AB, Canada. Peptides were >95% pure by HPLC and mass spectral criteria. The concentrations and amino acid compositions of stock peptide solutions (1 to 3 mM), dissolved in 25 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4 were verified by quantitative amino acid analysis. The above described receptor activating peptides have been shown to activate PARs in a number of species including the hamster, rat, guinea-pig and humans and have to date been found to be the most potent for doing so. It was based on previously published work by us (Hollenberg et al., 1992; 1993; 1997) and by others (Scarborough et al., 1992; Vassallo et al., 1992) that this spectrum of receptor-activating peptides was selected for purposes of comparing the gastric and pulmonary smooth muscle responses. Amastatin, nifedipine, indomethacin and human thrombin (3000 NIH units/mg; cat no. T-6759) and heparin were from sigma (St. Louis MO, U.S.A.). Genistein was from ICN biochemical (Costa Mesa CA, U.S.A.). Tyrphostin 47/AG 213 (Levitzki & Gazit, 1995) and the Src-tyrosine kinase-selective inhibitor, PP1 (Hanke et al., 1996) were from Calbiochem (La Jolla CA, U.S.A.).

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT – PCR) detection of PAR1 and PAR2 and partial sequencing of guinea-pig PAR1 and PAR2

To assess the presence of PAR1 and PAR2 mRNA in the lung tissue, total RNA was prepared either from a dissected lung segment or from a parenchymal strip, prepared as for a bioassay, using the TRIR reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati OH, U.S.A.). RNA samples were then digested for 15 min at room temperature with DNase I (10 units in 10 μl: Pharmacia FPLCpure™, Amershan Pharmacia Biotech, Baie D'Urfé QC, Canada) to eliminate any possible contaminating DNA. DNase I was then inactivated by heating at 68°C for 15 min in the presence of 2.5 μM EDTA. The RNA was reverse-transcribed (RT) with a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit using pd(N)6 primer (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology, Uppsala, Sweden) according to manufacturers recommendations at 37°C for 60 min; 2 μl of this solution was used with primer pairs derived from Rat PAR1 and PAR2. For PAR1, the primer pairs were: forward primers, (a) PAR1F: 5′-AAAAGCTTCCCGCTCATTTTTTCTCAGGAA-3′; (b) PAR1F1 (lacking the HindIII site present in PAR1F: bold letters): 5′-CCCGCTCATTTTTTCTCAGGAA-3′ and reverse primer, PAR1R: (containing an EcoRI site shown in bold) 5′-GGGAATTCAATCGGTGCCGGAGAAGT-3′ (expected length of PCR product for PAR1F/PAR1R, 409 nucleotides). For PAR2, the primer pairs were: forward primer, PAR2F1: 5′-CACCACCTGTCACGATGTGCT-3′ and reverse primer, PAR2R: 5′-CCCGGGCTCAGTAGGAGGTTTTAACAC-3′ (expected length of PCR product, 527 nucleotides). A second PAR2 forward primer pair, about 330 nucleotides downstream of PAR2F1, based on the determined sequence of guinea-pig PAR2 [PAR2F2: 5′-CAACAGCTGCATTGACCCCTT-3′ (expected length of PCR product, when used with PAR2R, 196 nucleotides)] was also used to confirm that the PCR product yielded by the PAR2F1/PAR2R primer pair did indeed represent guinea-pig PAR2. The signal yielded by the PAR2 primer pairs was normalized to the PCR signal generated from the same RT product using a primer pair for glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), with the sequences: forward primer, GAP-F: 5′-CGGAGTCAACG GATTTGGTCGTAT-3′ and reverse primer, GAP-R: 5′-AGCCTTCTCCATGGTGGTGAAGAC-3′ (expected length of PCR product, 309 nucleotides). Polymerase-chain reaction (PCR) amplification was achieved using 2.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison WI, U.S.A.) in a 10 mM Tris.HCl buffer, pH 9.0 (0.05 ml final vol), containing MgCl2 (1.5 mM), KCl (50 mM), 0.1% v/v Triton X-100 and 0.2 mM each of deoxynucleotide triphosphates. Amplification for 35 cycles began with a 1 min denaturation period at 94°C, followed by a 1 min reannealing time at 55°C and a primer extension period of 1 min at 72°C. PCR products were separated by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The PCR products obtained with primer pairs PAR1F/PAR1R and PAR2F1/PAR2R were ‘gene-cleaned' (Magic™ PCR Preps DNA purification system, Promega, Madison WI, U.S.A.) and ligated (Ready To Go™ T4 ligase, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc. Baie D'Urfé QC, Canada) into the PGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison WI, U.S.A.). This ligation mixture (2 μl) was used to transform E. coli strain DH5α to produce permanent clones for both manual and automated sequencing by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (Sanger et al., 1977), employing a T7DNA sequencing kit (Pharmacia, Dorval QC, Canada) or via the DNA Services Facility at the University of Calgary Faculty of Medicine.

Immunohistochemistry

Perfused dissected lung lobules and peripheral parenchymal strips (2×10 mm), excised as for a bioassay, were fixed for about 24 h at room temperature in 10% isotonic buffered formalin solution, pH 7.4, followed by paraffin embedding. Tissue sections (4 μm) were cut, mounted on silane-coated slides, dried overnight, deparaffinized and treated with 3% H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature to destroy endogenous tissue peroxidase. The PAR2 epitope against which the B5 antibody was developed (Al-Ani et al., 1999), was unmasked by treatment of the slides with dilute pepsin (Digest-All 3, Zymed, San Francisco CA, U.S.A.) for 10 min at 37°C followed by washing with isotonic buffered saline, pH 7.4. After pre-blocking slides with avidin/biotin treatment, tissue was preabsorbed for 10 min with 10% (vol−1 vol−1 in buffered saline) non-immune goat serum (Zymed, San Francisco CA, U.S.A.), washed and then exposed to a 1/1000 dilution of B5 anti-PAR2 antiserum overnight at 4°C, without or with preadsorption of the antiserum for 2 h with the immunizing peptide (final concentration 20 μg ml−1). Immunoreactivity was visualized with the use of biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG followed with streptavadin-conjugated peroxidase (Sigma, St. Louis MO, U.S.A.) and colour generation with diamino-benzidine (25 μg ml−1, 10 min, room temperature). Tissue was counter-stained with haematoxylin (Fisher, Fair Lawn NJ, U.S.A.), and the image was recorded by digital photomicrography.

Results

Responses of the pulmonary strip preparation to PAR1-activating peptides: potentiation by amastatin, desensitization of thrombin action and comparison of activities and concentration-effect curves with the gastric preparation

Both thrombin and the thrombin receptor-derived peptides P5-NH2 and TF-NH2 caused a contractile response of the pulmonary strip preparation (Figure 1 and data not shown for P5-NH2). Previous work has shown that at a concentration of 3 – 4 μM, P5-NH2 selectively activates PAR1 compared with the PAR2 and that TF-NH2 is highly selective for PAR1 compared with PAR2 (Kawabata et al., 1999). Because of the known presence of peptidase activity in lung tissue and because of the recognized susceptibility of PAR-APs to amino-peptidase (Coller et al., 1992) we monitored the response to TF-NH2 and P5-NH2 in the absence and presence of the amino-peptidase inhibitor, amastatin (Figure 1). The protease inhibitor significantly (at least 2 fold) potentiated the response to P5-NH2 and TF-NH2 (Figure 1A and data not shown). Concentrations of amastatin higher than 10 μM caused no further potentiation of the response; this concentration of amastatin was therefore added to the organ bath for all subsequent experiments with the receptor-activating peptides. For purposes of comparison, this concentration of amastatin was also added to the organ bath for the gastric contractile assays in which this amino-peptidase inhibitor also potentiated the contractile action of TF-NH2 (Figure 1D and see below). Other protease inhibitors (e.g. phosphoramidon, leupeptin, captopril) either with or without amastatin did not potentiate the contractile actions more than the potentiation observed with amastatin alone (not shown).

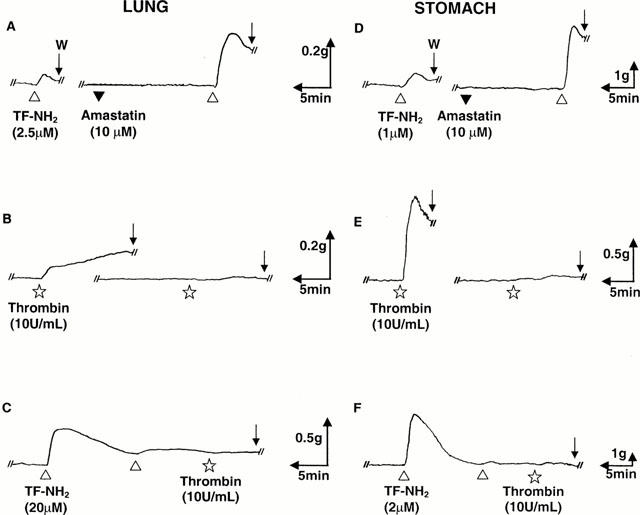

Figure 1.

Contractile responses of the guinea-pig lung and stomach LM preparations to thrombin and the selective PAR1AP, TF-NH2: potentiation by amastatin and desensitization of the thrombin response by TF-NH2. The contractile responses to TF-NH2(▵) and thrombin (⋆) were monitored in the lung parenchymal strip (left-hand tracings, A – C) and stomach LM preparation (right-hand tracings, D – F), as outlined in Methods. In each preparation, the contractile response was potentiated by the addition of amastatin (10 μM, ▾: tracings A and D). Desensitization of the tissues by the repeated addition of TF-NH2 to the organ bath also desensitized the tissues to thrombin (Tracings C and F). The scale for time (min) and tension (g, mN) is also shown for each tracing. W (Arrow)=tissue wash.

The response to thrombin showed considerable tachyphylaxis in both tissue preparations, even after a 1 h re-equilibration period (Figure 1 and data not shown). Desensitization of the contractile response of the lung preparation (but not the gastric preparation) was also observed after repeated exposures of the tissue to relatively high concentrations of TF-NH2 (10 – 20 μM) (data not shown). In the stomach LM preparation, as observed by us previously, a 25 min – 1 h re-equilibration period allowed for a re-sensitization to the PAR-APs, but not to thrombin (Figure 1 and data not shown). A lung preparation desensitized by the cumulative addition of the selective PAR1AP, TF-NH2 to the organ bath no longer responded to thrombin (Figure 1C). A similar result was observed with the LM preparation (Figure 1F). Nonetheless, tissues which were desensitized to thrombin subsequently did respond to TF-NH2 or P5-NH2 (not shown and see Hammes & Coughlin, 1999). Because of the partial desensitization observed in the lung preparation at relatively high concentrations of P5-NH2 and TF-NH2, even after a 40 min to 1 h re-equilibration period, concentration-effect curves for the lung preparation were obtained by monitoring only the first response to each receptor-activating peptide, subsequent to standardizing the tissue's response to 50 mM KCl. For the gastric LM preparation a re-equilibration period of 25 min to 1 h allowed for complete resensitization and therefore permitted the measurement of responses to multiple concentrations of the agonists in a single tissue preparation. The contractile responses to increasing concentrations of the PAR-APs in both the lung and stomach tissues were expressed as a percentage (% KCl) of the contractile response caused in each preparation by 50 mM KCl (Figure 2).

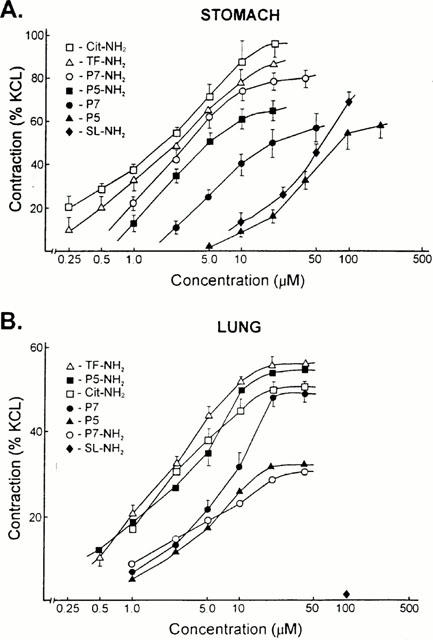

Figure 2.

Concentration-effect curves for PAR-APs in the stomach (A, upper) and lung (B, lower) preparations. Contractile responses to increasing concentrations of the PAR-APs were measured as outlined in Methods, relative to the contraction caused in each preparation by 50 mM KCl (% KCl). Each data point represents the mean±s.e.mean (bars) for observations obtained from six or more independent tissue preparations coming from three or more different animals.

The concentration-effect curves for the six PAR1-APs in the lung preparation (Figure 2B) revealed the following order of peptide potencies: cit-NH2≅TF-NH2≅P5-NH2>P7≅ P5≅P7-NH2. This order of peptide potencies was clearly distinct form the order measured concurrently in the stomach longitudinal muscle strip assay (Figure 2A): Cit-NH2≅TF-NH2⩾P7-NH2⩾P5-NH2>P7>P5. Apart from the distinct order of potencies for the PAR1APs in the two preparations, there were differences in the maximum responsiveness of the lung preparation to the different PAR-APs: P5 and P7-NH2 appeared to be partial agonists, compared with the other PAR1APs. There were also differences in the maximum responsiveness of the gastric LM preparation, with P7, P5 and P5-NH2 behaving as partial agonists (Figure 2).

Actions of PAR2 APs in the pulmonary and gastric smooth muscle preparations

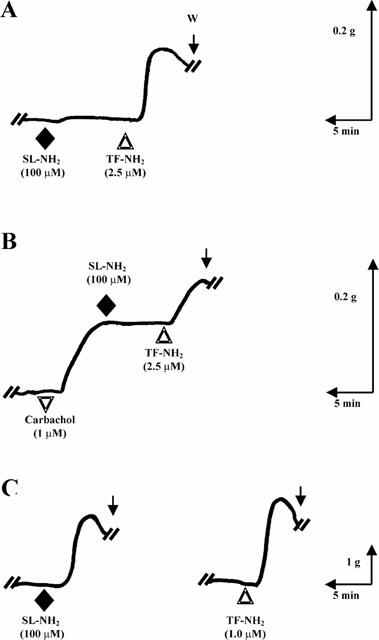

In the gastric LM preparation, the PAR2-selective agonist, SL-NH2 caused a contractile response, as we have observed previously (Al-Ani et al., 1995 and Figure 3C). The potency of SL-NH2 in the stomach preparation was equivalent to that of P5 (Figure 2A). In contrast, in the lung preparation, when care was taken to prepare parenchymal strips 2 mm or less in width from the very periphery of the lobe, a contractile response to the PAR2AP, SL-NH2, was not observed in any of more than 75 preparations at concentrations as high as 100 μM (Figure 3A). Such tissues contracted in response to much lower concentrations (e.g. 2.5 μM) of the PAR1AP, TF-NH2 (Figure 3A). In a lung strip that was pre-constricted with carbachol, the PAR2AP, SL-NH2, failed to cause either a contraction or relaxation, whereas the selective PAR1AP, TF-NH2, caused a further increase in tension (Figure 3B). On occasion (not shown), a contractile response was caused by SL-NH2 (⩾100 μM) in a lung strip preparation that was wider than 3 mm, possibly containing higher order bronchial elements (see histology, below).

Figure 3.

Action of the PAR2-selective agonist, SL-NH2 in lung and stomach tissue: comparison with the action of TF-NH2. The lung parenchymal (A,B) and gastric LM tissues (C) were exposed to SL-NH2 (♦) or TF-NH2 (▵), either singly (C, LM tissue) or in succession (lung tissue, A,B). The effects of the two PAR-APs were also tested in a lung preparation that had been pre-constricted with carbachol (▿, tracing B). The tracings are representative of three or more independent experiments done with tissues coming from three or more separate animals. The scales for time (min) and tension (g, mN) are shown along with the tracings. W (arrow)=tissue wash.

Effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, indomethacin and removal of extracellular calcium in lung and gastric preparations

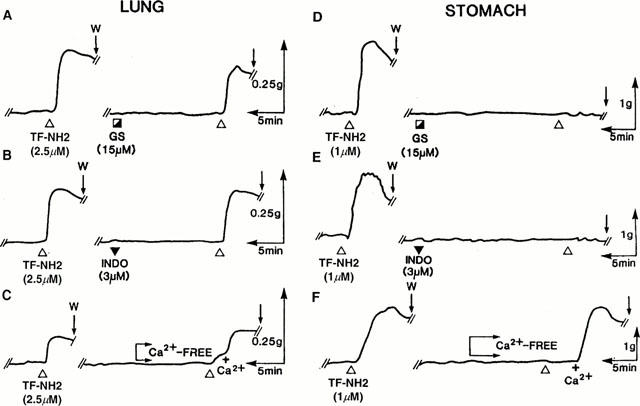

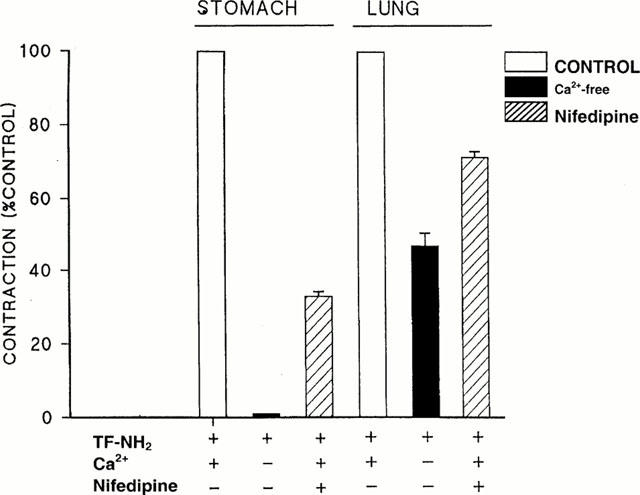

In our previous work with the PAR-activating peptides, we had observed that the PAR1-mediated contractile response of gastric smooth muscle preparations required the presence of extracellular calcium and was inhibited by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, genistein and the cyclo-oxgenase inhibitor indomethacin (Zheng et al., 1998). We were therefore interested to determine if the contractile responses for the lung parenchymal strip to PAR1APs required extracellular calcium and were sensitive to the same enzyme inhibitors. As illustrated in Figure 4A and B, the contractile response of the lung preparation to the PAR1AP, TF-NH2, was refractory to the action of indomethacin (neither inhibited, nor potentiated at 3 μM) and was only minimally affected by genistein (15 μM). Similarly, neither the Src-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor, PP1 (1 μM: Hanke et al., 1996), nor the non-specific tyrosine kinase inhibitor, tyrphostin 47/AG213 (20 μM: Levitzki & Gazit, 1995) affected the PAR1AP-stimulated contractions in this tissue (not shown). In contrast, under the same conditions, the contractile responses of the gastric preparation to the PAR1APs were abolished by indomethacin and by each of the three tyrosine kinase inhibitors tested (Figure 4D and E and data not shown). In the absence of extracellular calcium, there was an appreciable response of the lung preparation to TF-NH2 (on average, 30 – 40% of control: Figures 4C and 5), whereas the response of the gastric longitudinal muscle strip was abolished in the absence of extracellular calcium (Figures 4F and 5). An increase in tension in both preparations exposed to a PAR1 agonist was observed upon replenishing extracellular calcium (Figure 4C and F). In keeping with these results, the calcium channel blocker, nifedipine, caused a more marked inhibition of the PAR1AP-mediated response in the gastric preparation (>65% inhibition: Figure 5) than it did in the pulmonary strip preparation (<30% inhibition: Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Effects of indomethacin, genestein and removal of extracellular calcium on TF-NH2-mediated contractions in the lung (left) and stomach (right) preparations. Contractile responses to TF-NH2 were monitored in the lung (A – C) and stomach (D – F) both before and after exposure of the tissues for 20 min to genistein (GS ┌, 15 μM), indomethacin (▾, 3 μM) or after the removal of extracellular calcium (Ca2+-free). The tension was also monitored upon replenishing the organ bath with 2.5 mM calcium (+Ca2+). Tissues were washed and re-equilibrated for 1 h after the first exposure to TF-NH2. The tracings are representative of three or more independent experiments done with tissues coming from different animals. The scales for time (min) and tension (g, mN) are also shown. W (arrow)=tissue wash.

Figure 5.

Effects of nifedipine and removal of extracellular calcium on the TF-NH2-mediated contractile response in stomach and lung tissue. The inhibitory effects of either removing extracellular calcium, or of adding nifedipine (1 μM) to the organ bath on the contractile actions of TF-NH2 were monitored as outlined in Figure 4. Responses in the absence of calcium (filled histograms) or in the presence of nifedipine (1 μM, hatched histograms) were expressed as a percentage (% control) of the contractile response observed in the presence of 2.5 mM calcium and in the absence of nifedipine (open histograms). The histograms represent the averages (±s.e.mean, bars) for observations done with six or more tissue preparations coming from different animals.

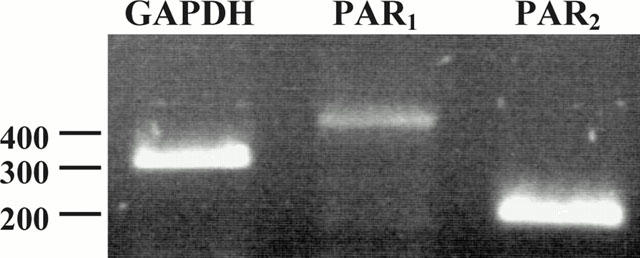

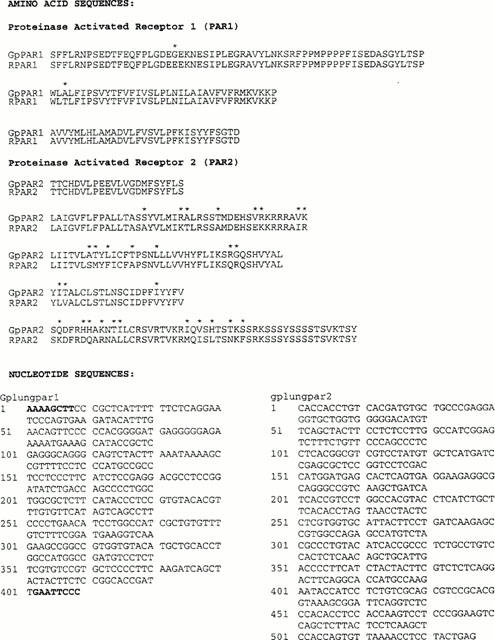

Detection of PAR1 and PAR2 by RT – PCR, partial sequences of guinea-pig PAR1 and PAR2

To determine if both PAR1 and PAR2 were present in the lung tissue, RNA was obtained both from freshly dissected whole lung lobules and from parenchymal strip preparations as obtained for the contractile bioassay. RT – PCR using primer pairs targeted to either PAR1 or PAR2 yielded oligonucleotide products having the sizes anticipated from the published sequences of the mouse, human and rat receptors. The relative signal intensities of the PAR1 and PAR2 RT – PCR products obtained from the whole lung tissue, compared with the RT – PCR signal for glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), are shown in Figure 6. The relative intensity of the PCR signals for PAR1 and PAR2 obtained for the parenchymal strip (not shown) were comparable to those shown in Figure 6 for whole lung tissue. Sequencing of the RT – PCR products obtained from the lung tissue, using primer pairs PAR1F/PAR1R for PAR1 and PAR2F1/PAR2R for PAR2 confirmed (Figure 7) that they did indeed represent partial sequences of guinea-pig PAR1 and PAR2. The identity of the PAR2 PCR product was supported further by an independent RT – PCR procedure, using a second forward PCR primer (PAR2F2) based on the determined guinea-pig oligonucleotide sequence shown in Figure 7. This second forward primer targets a receptor sequence about 330 nucleotides (110 amino acids) downstream from the 5′-primer (PAR2F1), that begins at the position of the amino acid sequence, TTCHDVL in extracellular loop 2. In comparing the partial predicted amino acid sequences we obtained from the guinea-pig tissue with the predicted amino acid sequences of rat PAR1 and PAR2, we observed only two amino acid differences between rat and guinea-pig PAR1 (out of 137 amino acid residues), despite a number of differences in the oligonucleotide sequences (not shown); there were 29 differences between rat and guinea-pig PAR2 (out of 176 amino acid residues: asterisks, Figure 7). Although there was a lack of a contractile response of the parenchymal strip for the PAR2AP, a strong PCR product was detected both for the lung segment used to prepare RNA for PCR-based sequencing (Figure 6) and for the parenchymal strip tissue prepared exactly as for a bioassay (results comparable to those shown in Figure 6). The PCR signal for PAR2 appeared much stronger than that obtained for PAR1.

Figure 6.

Reverse-transcriptase-polymerase-chain reaction detection of PAR1 and PAR2 in lung tissue. RNA was isolated from whole lung tissue and reverse-transcribed as outlined in Methods. RT – PCR was performed as described in Methods, using primer pairs targeted to PAR1 (PAR1F1/PAR1R), to PAR2 (PAR2F2/PAR2R) and to GAPDH (GAP-F/GAP-R). The positions of the oligonucleotide size markers (in nucleotides, nt) are shown to the left of the separating gel. The identity of each PCR product of the expected size is indicated at the top of each lane for GAPDH (expected size, 306 nt), PAR1 (expected size, 401 nt) and PAR2 (expected size, 196 nt).

Figure 7.

Translated amino acid sequences (upper) and oligonucleotide sequences (lower) for guinea-pig PAR PCR products. The oligonucleotide sequences (lower left and right) for the PCR products obtained by RT – PCR from lung RNA samples, using primer pairs PAR1F/PAR1R for PAR1 (gplungpar1: lower left) and primer pairs PAR2F1/PAR2R for PAR2 (gplungpar2: lower right) were determined as outlined in Methods. Nucleotide residues resulting from the added HindIII and EcoRI restriction sites, that are not part of the PAR2 receptor sequence, are shown in boldface type. The translated amino acid sequences for guinea-pig PAR1 and PAR2 are shown in the upper panel, compared with the equivalent rat PAR sequences (RPar1; RPar2). The asterisks denote differences between the rat and guinea-pig deduced amino acid sequences.

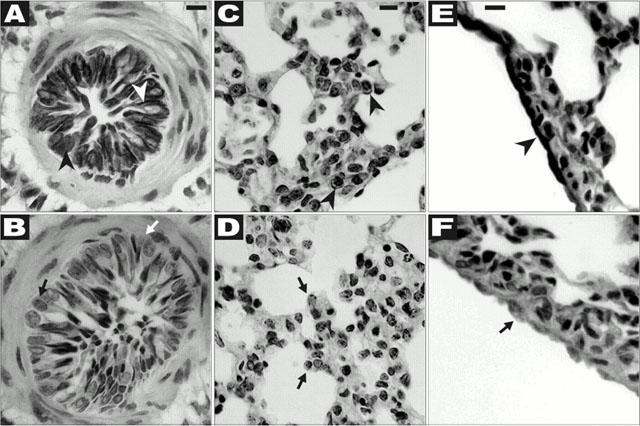

Immunohistochemical detection of PAR2 using antireceptor antibody B5

The haematoxylin stain of the peripheral strip sections used for the bioassay revealed the presence principally of scattered terminal bronchioles and very few arterial elements, amidst abundant parenchymal alveolar structures that have been described previously (Figure 8E,F, data not shown and see Kapanci et al., 1974). Given the absence of arterial and bronchial components observed histologically, it was evident that the contractile responses observed with the peripheral parenchymal strip preparation must have been due to the intrinsic contractility of the airway smooth muscle itself and not due to the contractility of the bronchiolar or vascular tissue components. In contrast, the histology of the whole lung segments revealed the expected presence of the primary and secondary bronchi with a prominent epithelial lining as well as numerous vascular structures (Figure 8A – D and data not shown). In the whole lung tissue containing primary and secondary bronchioles, the B5 antiserum revealed prominent reactivity in the bronchial epithelium (Figure 8A: granular bead-like staining at the cell periphery, open arrowhead; diffuse cytoplasmic staining, solid arrowhead) as well as in cells with the morphology of type II pneumocytes (Figure 8C), that exhibited granular staining at the cell periphery (solid arrowhead, Figure 8C). Pre-adsorption with the immunizing B5 peptide eliminated the staining in these cells (Figure 8B,D, solid and open arrows), indicating specificity. In contrast, in the parenchymal strip tissue, only diffuse cytoplasmic PAR2 immunoreactivity that was partially blocked by peptide pre-adsorption was observed in the alveolar components. Notwithstanding, in the occasional terminal bronchiole that was present in the strip, granular immunoreactivity (not shown), completely eliminated by peptide pre-adsorption, was detected in the epithelial elements as described above for Figure 8A. Some, but not all cells with the morphology of alveolar type II pneumocytes present in the strip preparation (not shown) also showed light immunoreactivity at the cell periphery; this reactivity was also eliminated by peptide pre-adsorption. In the parenchymal strip tissue, immunoreactivity neutralized by peptide pre-adsorption (Figure 8F, solid arrow) was detected in addition in cells at the very periphery of the strips (Figure 8E, solid arrowhead), most likely representing mesothelial cells of the pleural tissue. Thus, in contrast with the lobular tissue wherein PAR2-expressing cells were abundant and readily identified, in the parenchymal strip tissue used for the bioassay, it was possible to detect PAR2-expression by immunohistochemistry with confidence only in the mesothelial cells, type II pneumocytes and in the epithelial cells of the rare terminal bronchial elements.

Figure 8.

Immunohistochemistry of whole lung and peripheral strip tisssues. Sections of either whole lung (A – D) or of the peripheral strip preparation (E,F) were prepared from paraffin embedded fixed tissue specimens as outlined in Methods. Immunoreactivity was detected using the B5 anti-PAR2 antiserum as described, either without (A, C and E) or with (B, D and F) peptide pre-adsorption. (A) Shows bronchial epithelium immunoreactivity with a granular pattern at the cell periphery (open arrowhead) as well as in the cytoplasm (solid arrowhead); peptide pre-adsorption eliminated this reactivity (B, open and solid arrows). (C) Shows granular immunoreactivity at the periphery of a cell with morphology consistent with that of a Type II pneumocyte (solid arrowheads); this reactivity was eliminated by peptide pre-adsorption (solid arrows, D). (E) Shows the immunoreactivity of pleural mesothelial cells (solid arrowhead); this reactivity was neutralized by peptide pre-adsorption (F, solid arrow). Magnification was approximatately ×400 for A,B,E and F; and about ×200 for C and D. The solid bar at the top of A,C and E represents 10 μm, which scale also applies to each panel directly underneath (B,D and F).

Discussion

The main findings of our study were: (1) that the contractility of peripheral lung parenchymal strips was stimulated by a number of PAR1-activating peptides, but was not affected by the selective PAR2-activating peptide, SLIGRL-NH2 and (2) that there were differences between the pulmonary and gastric preparations in terms of the contractile signal transduction pathways and in terms of the structure-activity relationships for a number of PAR1-activating peptides (Figure 2). Our new data considerably extend our preliminary observations of the contractile activities of P5-NH2 and P7-NH2 in the lung strips assay (Mandhane et al., 1995). Further, our data differed somewhat from the findings of others (Cocks et al., 1999; Lan et al., 2000; Ricciardolo et al., 2000) in terms of a lack of response to the PAR2-activating peptide, SLIGRL-NH2.

Peptide potencies and possible role of tissue peptidase activity

As with a platelet assay system (Coller et al., 1992), it was necessary to prevent peptide degradation by the addition of the amino-peptidase inhibitor, amastatin, to observe the full effects of the PAR-activating peptides. Other peptidase inhibitors added in addition to amastatin had no further effect than did amastatin alone. This result suggested that aminopeptidase activity per se may play a significant role in the peripheral pulmonary strip tissue. In the presence of amastatin, the concentration range over which the PAR1-activating peptides caused a contractile response in the lung strip preparation was comparable to the concentration range over which the same peptides have been found to regulate contractility in smooth muscle preparations derived from other tissues (vascular or gastric tissue: Muramatsu et al., 1992; Hollenberg et al., 1993; Glusa & Paintz, 1994). Given the presence of peptidase activity in the lung and gastric tissue, the possibility cannot be entirely discounted that differential susceptibility of the PAR-activating peptides to the peptidases, albeit unlikely in the presence of amastatin, may possibly have affected the relative potencies of the PAR-activating peptides that were used. This theoretical (but unlikely) differential susceptibility to proteolysis of the peptide agonists with comparable sequences (e.g. P5, P7, P5-NH2, P7-NH2) would be difficult to document and was therefore not explored in the present study. Notwithstanding, the order of potencies for the contractile actions of the PAR-activating peptides in the lung preparation (Cit-NH2≅TF-NH2≅P5-NH2>P7≅P5≅P7-NH2; SL-NH2 not active) clearly differed from the order of peptide potencies observed in the gastric LM preparation (Cit-NH2≅TF-NH2⩾P7-NH2⩾P5-NH2>P7>P5≅SL-NH2), particularly in terms of the activity of P7-NH2, relative to Cit-NH2 and TF-NH2.

Comparison with previous structure-activity studies with PAR1-activating peptides

It can be noted that the relative potencies of the PAR1-activating peptides, modelled on the human tethered ligand, have been found to be comparable for activating PAR1 in both human and rat tissues (Hollenberg et al., 1993; Kawabata et al., 1999; Vassallo et al., 1992; Scarborough et al., 1992). Indeed, the order of potencies observed for the peptides in the guinea-pig gastric LM preparation was in accord with data obtained previously with a rat gastric LM assay (Hollenberg et al., 1993) and with a human cultured HEK cell assay (Kawabata et al., 1999). In the gastric LM preparation we have established previously, by a receptor cross-desensitization approach, that the response to the PAR1-APs peptides can be attributed principally to the activation of PAR1 and not PAR2. In agreement with these previous observations, the EC50s of all of the PAR1-APs except for P5 were lower than that of the PAR2-AP, SL-NH2 (Figure 2). The distinct relative potencies and different apparent intrinsic activities of the PAR1-activating peptides in the lung versus the gastric preparation therefore suggest the presence of a functionally distinct receptor subtype, in keeping with classical receptor criteria established some time ago (Ahlquist, 1948). Since the PAR1-AP, TF-NH2, was able to desensitize the lung preparation completely to subsequent thrombin stimulation (Figure 1), it was clear that the preparation did not possess functional PAR4, which is not affected by PAR1-APs (Xu et al., 1998; Kahn et al., 1998). Notwithstanding, the partial sequence that we have determined for guinea-pig PAR1 was essentially the same as that for rat PAR1 (Figure 7), including the putative tethered ligand activating sequence. Thus, the distinct order of peptide potencies for the PAR1-APs in the lung and LM tissues and the differences in signal transduction pathways between the lung and gastric preparations may possibly be due either, as suggested above, to the presence of a distinct receptor subtype that was not detected by RT – PCR or to a distinct post-translational modification of the lung PAR1 receptor (e.g. differential glycosylation) that could in theory alter peptide specificity. The distinct order of PAR1-AP potencies we have found in comparing the guinea-pig lung and gastric tissues is in keeping with previous work we have done with human placental vascular preparations, wherein the PAR1-activating peptide structure activity (SAR) profiles differ from the one observed in human platelets (Tay-Uyboco et al., 1995). As in the present study, our previous work with the human placental tissue displaying distinct PAR-AP structure activity relationships, did not reveal the presence of a distinct PAR1 receptor mRNA sequence. It can be noted that the same receptor present in different tissues can in theory yield different agonist relative potencies because of differences in receptor coupling, leading to distinct agonist intrinsic efficacies. Thus, receptor antagonists are required to distinguish clearly between receptor subtypes. Unfortunately, pure receptor antagonists for PAR1, such as the one recently described (Andrade-Gordon et al., 1999) are not yet readily available to explore in more depth the receptors in the two PAR1AP-responsive tissues we have described in this study. Further work will thus be required to determine the molecular basis for the functionally distinct receptor present in the lung parenchymal tissue.

Comparison with previous work using non-selective PAR1 activating peptides

Although previous work has documented a constrictor effect in lung tissue with non-selective PAR-activating peptides (e.g. SFLLRN-NH2: Lum et al., 1994; Cocks et al., 1999; Lan et al., 2000) or with thrombin, none of these previous studies used PAR1-selective agonists like TF-NH2 or Cit-NH2. Nonetheless, our data obtained using the selective PAR1APs, which were able to desensitize the tissue completely to the contractile action of thrombin (thus, ruling out the presence of functional PAR4, as mentioned above), were in keeping with previous studies with tracheal, bronchial and perfused lung preparations (Cocks et al., 1999; Lan et al., 2000; Lum et al., 1994). Taken together, all of the studies suggest that the contractile action of thrombin in the lung tissue can be attributed principally to the activation of PAR1 and not PAR4 that is activated with the assistance of PAR3. In the lung strip preparation, inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase with indomethacin did not either potentiate or block the PAR1-mediated contractile response. In contrast, in the work reported previously using a murine bronchial preparation, indomethacin potentiated a contracile response caused by the PAR1-activating peptide, SFLLRNP-NH2 (Cocks et al., 1999). Our data suggest that this epithelium-dependent PAR1-mediated relaxant response involving prostaglandins does not occur in the peripheral guinea-pig lung tissue. The ability of PAR1 activation to cause a contractile response in the lung strip preparation in vitro indicates that PAR1-mediated responses in lung tissue in vivo could result from a direct action of thrombin on lung tissue, in addition to the reported ability of thrombin or PAR1-activating peptides to cause bronchoconstriction indirectly via platelet activation (Cicala et al., 1999). In this regard, the intense desensitization towards repeated thrombin activation (Figure 1B) would suggest that in vivo, the effect of thrombin itself to alter alveolar function in the lung periphery may be transient.

Comparison with previous work with pulmonary preparations and PAR2 agonists

Our result with the parenchymal strip preparation can be compared with data obtained by others with rodent tissues (rat, mouse) using either isolated tracheal or bronchial preparations (Cocks, et al., 1999; Lan et al., 2000) or guinea-pig preparations employing either perfusion (Lum et al., 1994) or intratracheal/intravenous administration (Ricciardolo et al., 2000) of PAR-agonists. Significantly, in our work with the guinea-pig pulmonary strip preparation, we were not able to observe either a contractile or a relaxant response to the PAR2AP, SL-NH2, in contrast with the PAR2-mediated epithelium-dependent relaxation of tracheal or bronchial preparations observed by others in rodent tracheal and bronchial preparations (Cocks et al., 1999; Lan et al., 2000). Possibly these differences are due to species differences (mouse or rat in previous work with SL-NH2, compared with guinea-pig tissue for our own study). Importantly, the study of Ricciardolo et al. (2000), that appeared upon completion of our work, used the identical PAR2-targeted antiserum to localize the receptor in guinea-pig airway epithelial cells. That study documented a tachykinin-mediated (presumably neurally-triggered) PAR2-regulated bronchoconstriction caused by agonists administered in vivo, as well as both a mixed bronchomotor effect of PAR2-agonists in vitro, resulting in a prostanoid/epithelium-dependent relaxation of isolated trachea and main bronchi and a contraction of intrapulmonary bronchi. Our data with the peripheral parenchymal strip indicate that the prostanoid-dependent PAR2-mediated relaxant response and the neurally-regulated contractile response observed by Ricciardolo et al. (2000) are not present in the peripheral alveolar tissue, wherein contractile elements are thought to be important for matching ventilation to perfusion (Kapanci et al., 1974). Thus, overall, there would appear to be distinct regional differences in the various roles that PAR2 may play in the setting of pulmonary function.

Differences in signal transduction pathways between the pulmonary and gastric preparations

It is of interest that the signal transduction pathway for PAR1-mediated contractions of the lung strip preparation differed from those leading to contraction of the gastric LM preparation in terms of: (1) blockade of the gastric, but not the lung preparation by indomethacin and the tyrosine kinase inhibitors and (2) a complete dependence of the contractile response of the gastric but not the lung preparation on extracellular calcium. Thus, as pointed out briefly above, there were differences between the lung and gastric smooth muscle preparation not only in terms of the PAR1-activating peptide structure-activity relationships, but also in terms of the receptor signal transduction pathways leading to contraction. From a practical point of view, the distinct functional receptor systems for the PAR1 activating peptides present in the guinea-pig lung and gastric tissues, if also present in humans, may allow for the development of tissue-selective PAR receptor agonists and antagonists that could prove of use in a pathophysiological setting.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported in large part by an operating grant from the Canadian Medical Research Council (now, the Canadian Institute for Health Research), with ancillary support from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (Alberta Chapter) and The Kidney Foundation of Canada. S. Sandhu was supported by a summer studentship from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. We are most grateful to Drs F. Green and H. Benediktsson for helpful discussions and for assistance with evaluating the lung histology.

Abbreviations

- Amino acids are abbreviated by their one-letter codes; Cha

cyclohexyl-alanine

- Cit

citrulline

- Cit-NH2

AparafluroFRChaCit-y-NH2

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase

- HEK

human embryonic kidney cell line

- LM

gastric longitudinal smooth muscle preparation

- PAR1

proteinase-activated receptor-1

- PAR2

proteinase-activated receptor-2

- PAR-AP

PAR-activating peptide

- PAR1F

forward PCR primer for PAR1

- PAR1R

reverse PCR primer for PAR1

- PAR2F1 or PAR2F2

forward PCR primers for PAR2

- PAR2R

reverse PCR primer for PAR2

- P5

SFLLR

- P5-NH2

SFLLR-NH2

- P7

SFLLRN

- P7-NH2

SFLLRNP-NH2

- PP1

Src-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor, 4-amino-5(4-methylphenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine

- RT – PCR

reverse-transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- SL-NH2

SL1GRL-NH2

- TF-NH2

TFLLR-NH2

References

- AHLQUIST R.P. A study of the adrenotropic receptors. Am. J. Physiol. 1948;153:586–600. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1948.153.3.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AKERS I.A., PARSONS M., HILL M.R., HOLLENBERG M.D., SANJAR S., LAURENT G.J., MCANULTY R.J. Mast cell tryptase stimulates human lung fibroblast proliferation via protease-activated receptor-2. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2000;278:L193–201. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.1.L193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AL-ANI B., SAIFEDDINE M., HOLLENBERG M.D. Detection of functional receptors for the proteinase-activated receptor-2-activating polypeptide, SLIGRL-NH2, in rat vascular and gastric smooth muscle. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1995;73:1203–1207. doi: 10.1139/y95-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AL-ANI B., SAIFEDDINE M., KAWABATA A., RENAUX B., MOKASHI S., HOLLENBERG M.D. Proteinase-activated receptor 2 (PAR2): Development of a ligand-binding assay correlating with activation of PAR2 by PAR1- and PAR2-derived peptide ligands. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;290:753–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDRADE-GORDON P., MARYANOFF B.E., DERIAN C.K., ZHANG H.C., ADDO M.F., DARROW A.L., ECKARDT A.J., HOEKSTRA W.J., MCCOMSEY D.F., OKSENBERG D., REYNOLDS E.E., SANTULLI R.J., SCARBOROUGH R.M., SMITH C.E., WHITE K.B. Design, synthesis, and biological characterization of a peptide-mimetic antagonist for a tethered-ligand receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:12257–12262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CICALA C., BUCCI M., DEDOMINICIS G., HARRIOT P., SORRENTINO L., CIRINO G. Bronchoconstrictor effect of thrombin and thrombin receptor activating peptide in guinea-pigs in vivo. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:478–484. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COCKS T.M., MOFFAT J.D. Protease-activated receptors: sentries for inflammation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COCKS T.M., FONG B., CHOW J.M., ANDERSON G.P., FRAUMAN A.G., GOLDIE R.G., HENRY P.J., CARR M.J., HAMILTON J.R., MOFFATT J.D. A protective role for protease-activated receptors in the airways. Nature. 1999;398:156–160. doi: 10.1038/18223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLER B.S., WARD P., CERUSO M., SCUDDER L.E., SPRINGER K., KUTOK J., PRESWICH G.D. Thrombin receptor activating peptide: Importance of the N-terminal serine and its ionization state as judged by pH dependence, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and cleavage by aminopeptidas. M. Biochem. 1992;31:11713–11720. doi: 10.1021/bi00162a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORVERA C.U., DÉRY O., MCCONALOGUE K., AL-ANI B., CAUGHEY G.H., HOLLENBERG M.D., BUNNETT N.W. Thrombin and mast cell tryptase regulate myenteric neurons through proteinase-activated receptors-1 and 2. J. Physiol. 1999;517:741–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0741s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COUGHLIN S.R. Thrombin signalling and protease-activated receptors. Nature. 2000;407:258–264. doi: 10.1038/35025229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DERY O., CORVERA C.U., STEINHOFF M., BUNNETT N.W. Proteinase-activated receptors: novel mechanisms of signaling by serine proteases. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:1429–1452. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.6.C1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRAZEN J.M. &, SCHNEIDER M.W. Comparative responses of tracheal spirals and parenchymal strips to histamine and carbachol in vitro. M. Clin.. Invest. 1977;61:1441–1449. doi: 10.1172/JCI109063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLUSA E., PAINTZ M. Relaxant and contractile responses of porcine pulmonary arteries to a thrombin receptor activating peptide (TRAP) Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1994;349:431–436. doi: 10.1007/BF00170891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMMES S.R., COUGHLIN S.R. Protease-activated receptor-1 can mediate responses to SFLLRN in thrombin-desensitized cells: evidence for a novel mechanism for preventing or terminating signaling by PAR1's tethered ligand. Biochemistry. 1999;38:2486–2493. doi: 10.1021/bi982527i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANKE J.H., GARDNER J.P., DOW R.L., CHANGELIAN P.S., BRISSETTE W.H., WERINGER E.J., POLLOK B.A., CONNELLY P.A. Discovery of a novel, potent, and Src family-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Study of Lck- and FynT-dependent T cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:695–701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLENBERG M.D. Proteinase-activated receptor-4: PAR4 and counting – how long is the course. Trends. Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:271–273. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLENBERG M.D., LANIYONU A.A., SAIFEDDINE M., MOORE G.J. Role of the amino- and carboxyl-terminal domains of thrombin receptor-derived polypeptides in biological activity in vascular endothelium and gastric smooth muscle: evidence for receptor subtypes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;43:921–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLENBERG M.D., SAIFEDDINE M., AL-ANI B., KAWABATA A. Proteinase-activated receptors: structural requirements for activity, receptor cross-reactivity and receptor selectivity of receptor-activating peptides. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1997;75:832–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLENBERG M.D., YANG S.G., LANIYONU A.A., MOORE G.J., SAIFEDDINE M. Action of thrombin receptor polypeptide in gastric smooth muscle: identification of a core pentapeptide retaining full thrombin-mimetic intrinsic activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;42:186–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIHARA H., CONNOLLY A.J., ZENG D., KAHN M.L., ZHENG Y.W., TIMMONS C., TRAM T., COUGHLIN S.R. Protease-activated receptor 3 is a second thrombin receptor in humans. Nature. 1997;386:502–506. doi: 10.1038/386502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAHN M.K., ZHENG Y.-W., HUANG W., BIGORNIA V., ZENG D., MOFF S., FARESE R.V. , JR, TAM C., COUGHLIN S.R. A dual thrombin receptor system for platelet activation. Nature. 1998;394:690–694. doi: 10.1038/29325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAPANCI Y., ASSIMACOPOULOS A., IRLE C., ZWAHLEN A., GABBIANI G. ‘Contractile interstitial cells' in pulmonary alveolar septa: a possible regulator of ventilation-perfusion ratio? Ultrastructural, immunofluorescence, and in vitro studies. J. Cell. Biol. 1974;60:375–392. doi: 10.1083/jcb.60.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., SAIFEDDINE M., AL-ANI B., LEBLOND L., HOLLENBERG M.D. Evaluation of proteinase-activated receptor-a (PAR1) agonists and antagonists using a cultured cell receptor desensitization assay: activation of PAR2 by PAR1-targeted ligands. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;288:358–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAN R.S, , STEWART G.A., HENRY P.J. Modulation of airway smooth muscle tone by protease activated receptor-1,-2,-3 and -4 in trachea isolated from influenza A virus-infected mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:63–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVITZKI A., GAZIT A. Tyrosine kinase inhibition: an approach to drug development. Science. 1995;267:1782–1788. doi: 10.1126/science.7892601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUM H., ANDERSEN T.T., FENTON J.W., II, MALIK A.B. Thrombin receptor activation peptide induces pulmonary vasoconstriction. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:C448–C454. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.2.C448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANDHANE P., SAIFEDDINE M., GREEN F.H.Y., HOLLENBERG M.D. Contractile actions of thrombin receptor-derived polypeptides in rat and guinea-pig lung parenchymal smooth muscle. Proc. West. Pharmacol. Soc. 1995;38:93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURAMATSU I., ITOH H., LEDERIS K., HOLLENBERG M.D. Distinctive actions of epidermal growth factor-urogastrone in isolated smooth muscle preparations from guinea-pig stomach: Differential inhibition by indomethacin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;245:625–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURAMATSU I., LANIYONU A.A., MOORE G.J., HOLLENBERG M.D. Vascular actions of thrombin receptor peptide. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1992;70:996–1003. doi: 10.1139/y92-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NYSTED S., EMILSSON K., WAHLESTED C., SUNDELIN J. Molecular cloning of a potential proteinase activated receptor. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:9208–9212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RASMUSSEN U.B., VOURET-CRAVIARI V., JALLAT S., SCHLESINGER Y., PAGES G., PAVIRANI A., LECOCQ J.-P., POUSSEGUR J., VAN OBBERGHEN-SCHILLING E. cDNA cloning and expression of a hamster α-thrombin receptor coupled to a Ca+ mobilization. FEBS Lett. 1991;288:123–128. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICCIARDOLO F.L, , STEINHOFF M., AMADESI S., GUERRINI R., TOGNETTO M., TREVISANI M., CREMINON C., BERTRAND C., BUNNETT N.W., FABBRI L.M., SALVADORI S., GEPPETTI P. Presence and bronchomotor activity of protease-activated receptor-2 in guinea-pig airways. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 2000;161:1672–1680. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9907133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAIFEDDINE M., AL-ANI B., CHENG C.H., WANG L., HOLLENBERG M.D. Rat proteinase–activated receptor-2 (PAR-2): cDNA sequence and activity of receptor-derived peptides in gastric and vascular tissue. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:521–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANGER F., NICKLEN S., COULSON A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCARBOROUGH R.M., NAUGHTON M.-A., TENG W., HUNG D.T., ROSE J., VU T. K.-H., WHEATON V.I., TUREK C.W., COUGHLIN S.R. Tethered ligand agonist peptide: structural requirements for thrombin receptor activation reveal mechanism of proteolytic unmasking of agonist function. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:13146–13149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAY-UYBOCO J., POON M.-C., AHMAD S., HOLLENBERG M.D. Contractile actions of thrombin receptor-derived polypeptides in human umbilical and placenta vasculature: evidence for distinct receptor systems. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:569–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VASSALLO R.R, , JR, KIEBER-EMMONS T., CICHOWSKI K., BRASS L.F. Structure-function relationship in the activation of platelet thrombin receptors by receptor-derived peptides. J. Bio.l Chem. 1992;267:6081–6085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VU T.-K., HUNG D.T., WHEATON V.I., COUGHLIN S.R. Molecular cloning of a functional thrombin receptor reveals a novel proteolytic mechanism of receptor activation. Cell. 1991;64:1057–1068. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90261-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU W.-F., ANDERSEN H., WHITMORE T.E., PRESNESS S.R., YEE D.P., CHING A., GILBERT T., DAVIE E.W., FOSTER D. Cloning and characterization of human protease-activated receptor 4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:6642–6646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG S.-G., LANIYONU A. , SAIFEDDINE M., MOORE G.J., HOLLENBERG M.D. Actions of thrombin and thrombin receptor peptide analogues in gastric and aortic smooth muscle: Development of bioassays for structure-activity studies. Life Sci. 1992;51:1325–1332. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90631-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHENG X.-L., RENAUX B., HOLLENBERG M.D. Parallel signal transduction pathways activated by receptors for thrombin (PAR1) and EGF-urogastrone in guinea-pig gastric smooth muscle: blockade by inhibitors of mitogen-activated protein kinase-kinase (MEK) and phosphatidyl inositol 3′-kinase. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;123:325–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]