Abstract

The effect of endogenous glucocorticoid hormones on the expression of rat B1 receptors was examined by means of molecular and pharmacological functional approaches.

Rats were adrenalectomized (ADX), and 7 days after this procedure the intradermal injection of B1 receptor agonist des-Arg9-BK produced a significant increase in the paw volume, while only a weak effect was observed in sham-operated animals. A similar increase in the contractile responses mediated by B1 agonist des-Arg9-BK was also observed in the rat portal vein in vitro.

Chemical ADX performed with mitotane (a drug that reduces corticosteroid synthesis) produced essentially the same up-regulation of B1 receptors as that observed in ADX rats.

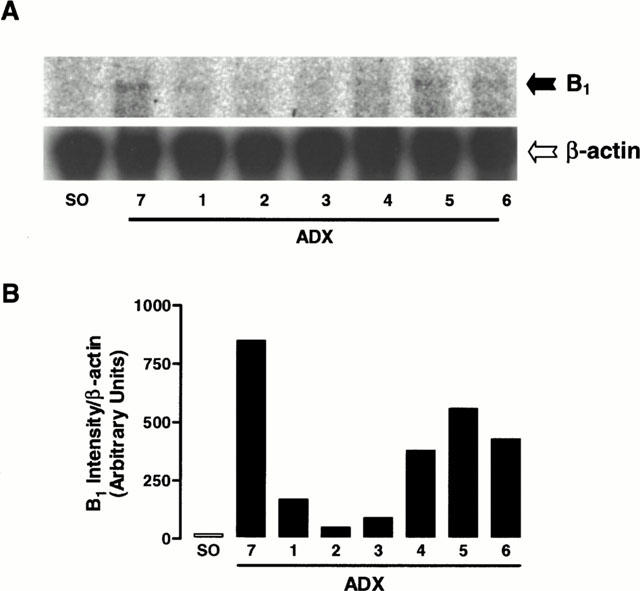

The modulation of B1 receptor expression was evaluated by ribonuclease protection assay, employing mRNA obtained from the lungs and paw of ADX rats.

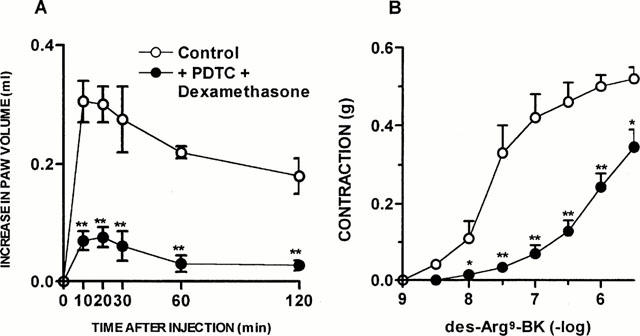

Additionally, both paw oedema and contraction of portal vein mediated by B1 agonist des-Arg9-BK in ADX rats, were markedly inhibited by treatment with dexamethasone, or COX-2 inhibitor meloxican, or with the NF-κB inhibitor PDTC. Interestingly, the same degree of inhibition was achieved when the animals were treated with a combination of submaximal doses of dexamethasone and PDTC.

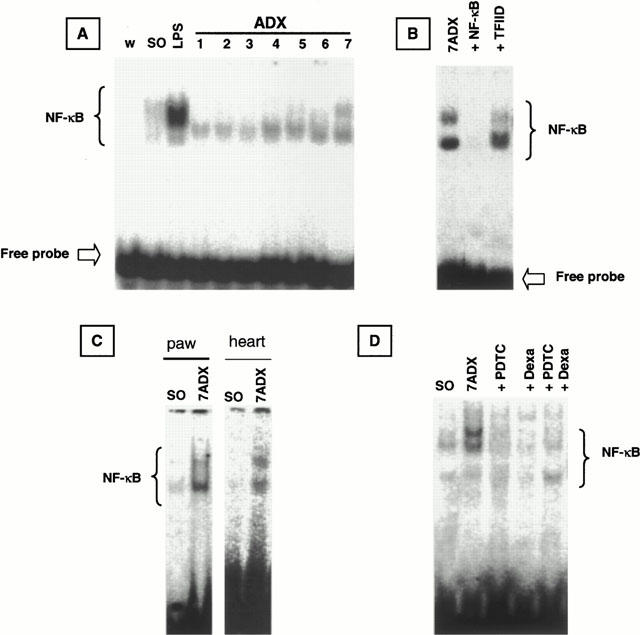

The involvement of NF-κB pathway was further confirmed by mobility shift assay using nuclear extracts from lung, paw and heart of ADX rats. It was also confirmed that the treatment of ADX rats with dexamethasone, PDTC or dexamethasone plus PDTC completely inhibit NF-κB activation caused by absence of endogenous glucucorticoid.

Together, the results of the present study provide, for the first time, molecular and pharmacological evidence showing that B1 kinin receptor expression can be regulated through endogenous glucocorticoids by a mechanism dependent on NF-κB pathway. Clinical significance of the present findings stem from evidence showing the importance of B1 kinin receptors in the mediation of inflammatory and pain related responses.

Keywords: Adrenal hormones, nuclear factor-κB, B1-kinin receptor up-regulation, rat paw oedema, rat portal vein, ribonuclease protection assay, gel shift assay, des-Arg9-bradykinin

Introduction

Bradykinin (BK) and related kinins form a group of potent peptides widely accepted as mediators of inflammatory and nociceptive processes (Farmer & Burch, 1992; Hall, 1992). Kinins are metabolized by proteolytic enzymes to form a variety of products including the active fragments, des-Arg9-BK and des-Arg10-kallidin (Regoli & Barabé, 1980). The current classification of kinin receptors distinguishes two types, namely B1 and B2, and their existence has been supported by both pharmacological and molecular biological studies (for reviews see Marceau et al., 1998; Marceau & Bachvarov, 1998). Cloning studies carried out on different animal species (such as mouse, rat, rabbit and human) revealed that kinin receptors belong to the superfamily of seven transmembrane domain G-protein coupled receptors (McEachern et al., 1991; Eggerix et al., 1992; Hess et al., 1992; 1994; Pesquero et al., 1996; Ni et al., 1998a).

The B2 receptors, which are optimally stimulated by BK or kallidin, mediate most in vivo effects usually assigned to kinins in normal rodents, rabbits and humans, including vasodilatation, pain, increased vascular permeability and increased production of eicosanoids and nitric oxide (Hall, 1992; Calixto et al., 2000). On the other hand, the B1 receptors are preferentially activated by kinin metabolites des-Arg9-BK and des-Arg10-kallidin. With some exceptions, these receptors are not present in most normal tissues, but are rapidly induced under many inflammatory conditions such as trauma, arthritis, cystitis, UV irradiation, colitis and hyperalgesia (Regoli et al., 1981; Bouthillier et al., 1987; Marceau et al., 1987). The mechanisms that underlie the inducible property of B1 receptors, an unusual feature for a G-protein coupled receptor, are not yet completely understood. There is now evidence suggesting that the rapid induction of the B1 receptor gene is regulated both at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels (Marceau et al., 1997). The promoter region of the human B1 receptor bears the characteristics of an eukariotic inducible promoter with a functional TATA box, and contains additional positive and negative control elements, with evidence of tissue specificity and cytokine regulatory control (Marceau et al., 1998). Both DNA sequencing and analysis of the promoter region have revealed several potential regulatory sites in the noncoding parts of the B1 receptor gene. Successive deletions indicated that the 0.14-kb 5′flanking fragment is sufficient for transcriptional activity and inducibility by interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and LPS, and for suppression by dexamethasone and by the putative anti-oxidant inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) PDTC (Ni et al., 1998b). Yang et al. (1998) have shown that AP-1 transcription factor and another unknown nuclear factors are probably crucial for full enhancer activity. Larrivée et al. (1998) have reported an important role of cell injury-controlled mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, singularly the p38 pathway, in the induction of B1 kinin receptors. It has already been demonstrated (Campos et al., 1999; Medeiros et al., 2000) that activation of protein kinases such as PKC, tyrosine kinase or MAP-kinases, and the transcription factor NF-κB, has a critical role in vivo in modulating the up-regulation of des-Arg9-BK-induced paw oedema in rats treated with the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β or TNFα or in isolated rabbit aorta.

Considering that glucocorticoids inhibit the action of transcription factors (for review see Barnes & Karin, 1997) and that NF-κB is directly involved in transcription and regulation of many inflammatory mediators which depend on de novo synthesis of active molecules or, of their pharmacological receptors, the present study was designed to investigate, by use of molecular and in vivo and in vitro pharmacological functional studies, whether endogenous glucocorticoids can modulate the expression of B1 receptor in the rat. We have also assessed the role played by NF-κB pathway in the B1 receptor expression in adrenalectomized (ADX) animals.

Methods

Adrenalectomy

Experiments were conducted using non-fasted male Wistar rats (140 – 180 g) housed at 22±2°C, under 12 : 12 h light-dark cycle (lights on at 0600 h). In most experiments, the animals were ADX according to the procedures described by Flower et al. (1986) with minor modifications. For this purpose, rats were anaesthetized with 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (0.25 g kg−1, i.p.), the dorsal region was incised (approximately 2 cm) and both adrenal glands were removed. After surgery, animals were returned to their cages, with free access to food. To maintain physiological sodium plasma concentrations, water was substituted by 0.9% NaCl solution. The experiments were performed 1–7 days after surgery. Other groups of animals were submitted to the procedure described above, but the adrenal glands were preserved (sham-operated, SO). The corticosterone levels in ADX and SO rats were measured by radioimmunoassay (Coat-A-Count rat corticosterone kit, DPC, Los Angeles, CA, U.S.A.) in accordance to manufacture's description.

Other groups of animals were treated with mitotane (2,2-bis [2-chlorphenyl-4-chlorophenyl]-1,1-dichloroethane; o′p′-DDD) (1.6 g kg−1, p.o., once a day for 10 days), an adrenocorticolytic agent, in order to compare the effects of chemical cessation of glucocorticoid production with surgical adrenalectomy procedure on responses mediated by activation of B1 receptors. The doses of mitotane were chosen based on preliminary experiments.

The reported experiments were carried out in accordance with current guidelines for the care of laboratory animals and ethical guidelines for investigations of experiments in conscious animals (Zimmerman, 1993).

Rat paw oedema

Under slight anaesthesia with 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (0.125 g kg−1, i.p.), animals received a 0.1 ml intraplantar injection of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; composition, mmol/l: NaCl 137, KCl 2.7 and phosphate buffer 10) containing the B1 des-Arg9-BK (10 – 100 nmol paw−1) or the B2 tyrosine8-BK (0.3 – 10 nmol paw−1) selective receptor agonists in the right hindpaw. The left paw received the same volume of PBS (0.1 ml) and was used as control. In most experiments, the animals were treated with captopril (5 mg kg−1, s.c.) 1 h beforehand, in order to prevent the degradation of peptides. The oedema was measured by use of a plethysmometer (Ugo Basile, Italy) at several time-points (10, 20, 30, 60 and 120 min) after injection of kinins, and was expressed in millilitres as the difference between right and left paws.

Rat portal vein

Male Wistar rats (140 – 180 g) were sacrificed with an overdose of CO2 followed by cervical dislocation and the portal vein was isolated, as described by Campos & Calixto (1994). A fine cannula (PE 50) was inserted into the vessel to aid removal of adhering tissues and fat. Rings 2–3 mm long (one per animal) were set up in 5 ml organ bath chambers containing Krebs-Henseleit solution (composition, mM: NaCl 118.0, KCl 4.4, MgSO4 1.1, CaCl2 2.5, NaHCO3 25.0, KH2PO4 1.2 and glucose 11.0), maintained at 37°C, pH 7.4, gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Isometric tension changes were recorded by means of an F-60 force transducer (Letica), under a basal tension of 0.5 g. Preparations were allowed to equilibrate for 60 min before drug additions, during which the bath solution was changed every 20 min. Following the equilibration period, in order to confirm the viability of the tissues, preparations were exposed to high potassium concentration (KCl, 80 mM, prepared by equimolar substitution of 74.4 mM of NaCl by KCl in the medium) as a standard stimulus. Experiments were initiated at least 30 min after washout and replacement with normal medium. Although each animal only yielded one portal vein ring, usually six preparations were tested simultaneously. The contractile responses are expressed in grams of tension.

Influence of treatment of ADX rats with some different groups of drugs

In a separate series of experiments, in order to confirm the involvement of B1 receptors in des-Arg9-BK-induced rat paw oedema, animals received an i.d. injection of the B1 selective agonist des-Arg9-BK (50 nmol paw−1) co-injected with the selective B1 receptor antagonist des-Arg9-NPC 17731 (30 nmol paw−1) or B2 receptor antagonist Hoe 140 (10 nmol paw−1). To assess the participation of COX in paw oedema mediated by B1 agonist in ADX rats, the animals were pre-treated with indomethacin (2 mg kg−1, i.p., 30 min) or with meloxicam (3 mg kg−1, i.p., 30 min) and the oedematogenic responses were measured as described above.

In another series of experiments, the ADX animals were treated with the glucocorticoid dexamethasone (0.5 mg kg−1, s.c.) or with the NF-κB inhibitor PDCT (100 mg kg−1, i.p.) once a day for 6 consecutive days after surgery. Other ADX animals received dexamethasone (0.05 mg kg−1, s.c.) in combination with PDTC (10 mg kg−1, i.p.) (at doses that these inhibitors did not produce any effect alone) every 24 h for 6 consecutive days. The effects of these treatments were evaluated on the seventh day in both rat paw oedema and the isolated rat portal vein models, as described previously.

Gel mobility shift analysis of nuclear extracts binding to NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide

Lung tissues were obtained from rats treated with lipopolysaccharide of Escherichia coli (LPS, 5 mg kg−1, i.p., 60 min) and used as a positive control group (Liu et al., 1997). Lung, paw and heart tissues were obtained from SO or ADX rats and from ADX rats treated or not with PDTC, dexamethasone or with a combination of both drugs. Tissues were frozen and pulverized under liquid nitrogen, and nuclear extracts were prepared as described by Shames et al. (1998). Tissues were firstly suspended in 30 volumes of ice-cold buffer solution A (10 mmol l−1 HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mmol l−1 KCl, 0.1 mmol l−1 EDTA, 0.35 mol l−1 sucrose, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5 mmol l−1 DTT, 0.5 mmol l−1 phenylmethylsulphonylfluoride-PMSF) and were then homogenized in Polytron for 20 s twice. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1500×g for 25 min. The pellet was re-suspended and homogenized in 15 ml of solution B (10 mmol l−1 HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mmol l−1 KCl, 0.1 mmol l−1 EDTA, 0.7 mol l−1 sucrose) and the homogenate was again centrifuged at 1500×g for 30 min. The pellet was washed in a buffer containing 10 mmol l−1 HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mmol l−1 KCl and 0.1 mmol l−1 EDTA. After centrifugation at 1500×g for 30 min, the pellet was re-suspended in high salt extraction buffer (100 μl) (20 mmol l−1 HEPES pH 7.9, 1.5 mmol l−1 MgCl2, 0.42 mol l−1 NaCl, 0.2 mmol l−1 EDTA, 25% glycerol, 0.5 mmol l−1 DTT, 0.5 mmol l−1 PMSF) and incubated at 4°C for 20 min. The nuclear extract was centrifuged for a further 30 min at 1500×g. The supermatant was re-suspended in solution containing 20 mmol l−1 HEPES pH 7.9, 50 mmol l−1 KCl, 0.2 mmol l−1 EDTA, 20% glycerol, 0.5 mmol l−1 DTT, 0.5 mmol l−1 PMSF and stored at −70°C until use. Protein concentration was determined by using the BioRad Protein Assay kit (BioRad).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay was performed by use of the Gel Shift Assay System kit from Promega, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, NF-κB double-stranded consensus oligonucleotide probe (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′) was end-labelled with [γ32P]-ATP (DuPont, New England) in the presence of T4 polynucleotide kinase for 10 min at 37°C. Unincorporated nucleotides were removed by passing the reaction mixture over a Sephadex G-25 spin column (Pharmacia). In a total volume of 20 μl, nuclear extracts (lung 20 μg, heart 30 μg or paw 10 μg) were incubated with gel shift binding buffer (mM: Tris-HCl pH 7.5 10, MgCl2 1, NaCl 50, DTT 0.5, EDTA 0.5, 4% glycerol, and 1 μg of poly(didC)) for 20 min at room temperature. Further, each sample was incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 25,000 c.p.m. of 32P-labelled NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide. Protein-DNA complexes were resolved by non-denaturing 6% acrilamide:bisacrilamide (37.5 : 1) in 0.25×Tris-borate/EDTA (TBE) buffer at 150 V for 2 h. The gel was vacuum-dried and analysed using a FUJIX BAS 2000 (Düsseldorf, Germany) Phosphor-Imager system. For competition studies, NF-κB or TFIID (5′-GCAGAGCATATAAGGTGAGGTAGGA-3′) unlabelled double-stranded oligonucleotide was included in molar excess over the amount of radiolabelled probe in order to detect specific and non-specific DNA/protein interactions, respectively.

B1 Ribonuclease Protection Assay (RPA)

The expression of B1 receptor in lung obtained from SO or ADX rats was checked by the RPA using 50 μg of total RNA extracted from tissues (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 or 7 days after surgery). The B1 receptor probe was obtained by cloning a PCR fragment generated using the primers 5-′CAGCCCTCTAACCGAAGCCTGC-3′ (sense); 5′-ACACCAGATCGGAAGCCGCC-3′ (anti-sense) based on published rat bradykinin B1 receptor gene sequence (Genbank AF009899) and rat genomic DNA as template. The PCR fragment was cloned into the plasmid pGem-Teasy (Promega) and linearized by digestion with Spel. Total length of the antisense probe was 321-nt and 259-nt before and after RNase A/T1 digestion, respectively. A β-actin probe of 170 bp (undigested) and 150 bp (after RNase A/T1 digestion) was used as an internal control. RNase protection assay was performed with an Ambion RPA III kit (ITC Biotechnology GmbH, Austin, TX, U.S.A.) according to the manufacturer's description. Radioactively labelled specific antisense RNA probes were prepared by use of 32P-α-UTP, transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) and approximately 80,000 c.p.m. of each probe was hybridized with the RNA samples. The hybridized fragments were separated by electrophoresis on denaturing gel and analysed using FUJIX BAS 2000 (Düsseldorf, Germany) Phosphor-Imager system. Quantitative analysis was performed by measurement of the intensity of the B1 receptor band normalized by the intensity of the β-actin band.

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as the mean accompanied by the s.e.mean. Statistical comparison of the data was carried out by the use of analysis of variance followed by unpaired Student's t-test. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Drugs and reagents

The drugs used were: des-Arg9-BK, BK, tyrosine8-BK, captopril, dexamethasone, 2,2,2-tribromoethanol, indomethacin, pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate (PDTC), bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS, E. coli serotype 0111B4, L=2630) (all from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Des-Arg9-NPC 17731 and HOE 140 were kindly supplied by SCIOS-NOVA Corporation (Baltimore, CA, U.S.A.) and by Hoechst (Frankfurt, Germany), respectively. Mitotane was donated by the University Hospital, UFSC, Florianópolis, Brazil, and Meloxicam was supplied by Boehringer Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany).

Most drugs were stored as 1 – 10 mM stock solutions at −20°C and were diluted to the desired concentrations in distilled water or in PBS solution just before use. The peptides were kept in siliconized plastic tubes. Most drugs were dissolved in PBS.

Results

Influence of adrenalectomy on B1 receptor functional responses

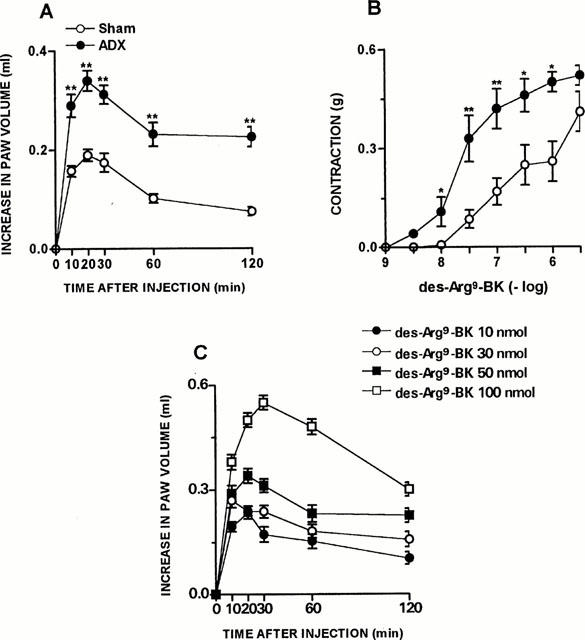

As reported previously (Campos & Calixto, 1995), i.d. injection of the selective B1 receptor agonist des-Arg9-BK (in doses up to 300 nmol) caused a very slight increase in paw oedema formation in naive animals (0.07±0.02 ml). On the other hand, the B2 selective agonist tyrosine8-BK (0.3 – 10 nmol paw−1) produced a marked and dose-related oedema (ED50 1.1 nmol paw−1, Emax 0.38±0.03 ml, n=6) (results not shown). However, in ADX rats, 7 days prior (but not 3 – 5 days prior), the i.d. injection of des-Arg9-BK produced a significant and dose-related oedema formation (ED50 31 nmol paw−1 Emax 0.51±0,045 ml) when compared to SO rats (Emax of 0.18±0.01 ml) (Figure 1A,C). On the other hand, the rat paw oedema induced by the selective B2 agonist receptor tyrosine8-BK (3 nmol paw−1) was not modified by the removal of adrenal glands as compared with SO animals (results not shown). No detectable levels of plasma corticosterone was observed in ADX animals when assessed by use of radioimmunoassay. However, the concentration of this hormone in SO rats was significantly increased (P<0.001) when compared with normal rats (148.2±4.6 and 102.0±5.6 ng ml−1, respectively).

Figure 1.

ADX-induced increase on des-Arg9-BK response in vivo and in vitro. (A) Des-Arg9-BK (50 nmol paw−1)-induced paw oedema in rats sham-operated or 7 days after adrenalectomy. Values represent the differences between volumes (in ml) of vehicle-injected (0.1 ml of PBS solution) and drug-injected paws. (B) Contraction concentration response curve for des-Arg9-BK (1 – 3000 nM) of portal vein from rats sham-operated or 7 days after adrenalectomy. (C) Dose-response curve of des-Arg9-BK-induced paw oedema in rats 7 days after adrenalectomy. Each point represents the mean±s.e.mean of 5 – 7 rats. In some cases the error bars are hidden within the symbols. Significantly different from control values *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (Student's unpaired t-test).

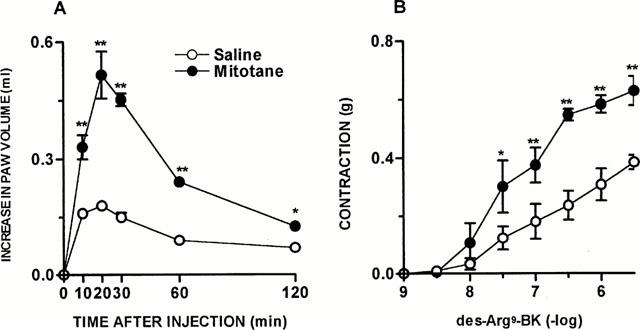

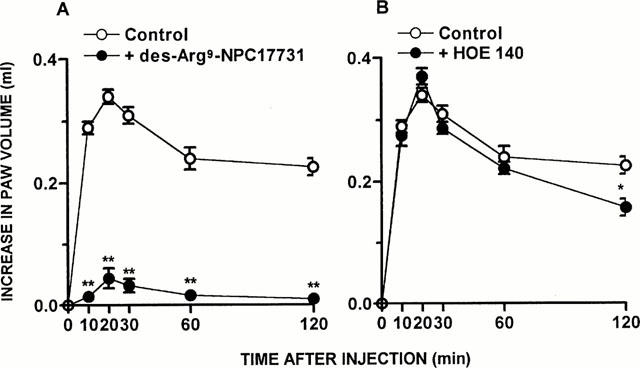

As demonstrated by Campos & Calixto (1994), the contractile response induced by des-Arg9-BK in rat portal vein increases significantly as a function of time, an effect which is inhibited by protein synthesis inhibitor, suggesting de novo formation of B1 receptors. In portal vein isolated from ADX rats 7 days prior, at 1 : 30 h of equilibration period, des-Arg9-BK (1 – 3000 nM) elicited a concentration-dependent contraction (EC50 of 35 nM and Emax 0.52±0.03 g) when compared to SO animals (EC50 of 180 nM and Emax 0.38±0.02 g) (Figure 1B). The treatment of normal rats with mitotane (1 – 16 g day−1, p.o, for 10 days, a drug that reduces corticosteroid synthesis mainly by a cytotoxic action on the cells) resulted in a marked increase in the paw oedema (Emax 0.51±0.06 ml) and a potentiation of the portal vein-contraction induced by des-Arg9-BK (EC50 of 42 nM and Emax 0.63±0.05 g), similar to that observed in ADX rats (Figure 2A,B). The co-injection of the selective B1 receptor antagonist des-Arg9-NPC 17731 (30 nmol paw−1) produced a significant inhibition of the paw oedema (87±4%) induced by des-Arg9-BK (50 nmol paw−1) in ADX rats. In contrast, des-Arg9-BK-induced oedema formation in ADX rats was not affected by the co-injection of the selective B2 receptor antagonist HOE 140 (10 nmol paw−1) (Figure 3A,B).

Figure 2.

Mitotane treatment-induced increase on des-Arg9-BK response in vivo and in vitro. (A) Des-Arg9-BK (50 nmol paw−1)-induced paw oedema in rats 10 days treated with saline or mitotane (1 – 1.6 g kg−1, v.o.). Values represent the differences between volumes (in ml) of vehicle-injected (0.1 ml of PBS solution) and drug-injected paws. (B) Contraction concentration response curves for des-Arg9-BK (1 – 3000 nM) of portal vein from rats 10 days treated with saline or mitotane (1 – 1.6 g kg−1, v.o.). Each point represents the mean±s.e.mean of 5 – 7 rats. In some cases the error bars are hidden within the symbols. Significantly different from control values *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (Student's unpaired t-test).

Figure 3.

The B1 receptor antagonist inhibit ADX-induced increase on des-Arg9-BK response in vivo. Des-Arg9-BK (50 nmol paw−1)-induced paw oedema in rats 7 days after adrenalectomy pre-treated with saline (Control), (A) des-Arg9-NPC 17731 (30 nmol paw−1) or (B) HOE 140 (10 nmol paw−1). Values represent the differences between volumes (in ml) of vehicle-injected (0.1 ml of PBS solution) and drug-injected paws. Each point represents the mean±s.e.mean of 5 – 7 rats. In some cases the error bars are hidden within the symbols. Significantly different from control values *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (Student's unpaired t-test).

The treatment of ADX rats with the COX-2 inhibitor meloxicam (3 mg kg−1, i.p., 1 h) caused a significant inhibition of the oedema induced by des-Arg9-BK (54±4%) in ADX rats (results not shown). In contrast, the treatment of ADX animals with the non selective COX inhibitor indomethacin (2 mg kg−1, i.p., 1 h) produced only a very slight inhibition of oedema induced by des-Arg9-BK (50 nmol paw−1) (results not shown).

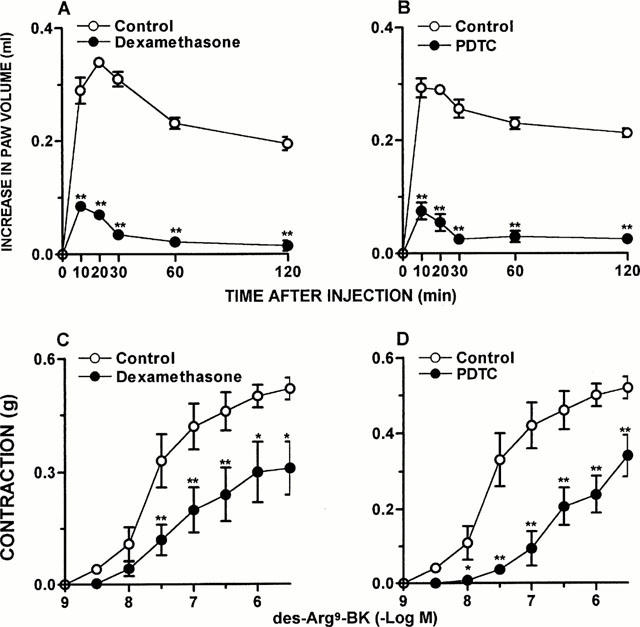

The treatment with dexamethasone (0.5 mg kg−1, s.c., once a day for 6 consecutive days) resulted in a significant inhibition of des-Arg9-BK-induced oedema formation (80±2%), as well as of the portal vein contraction induced by des-Arg9-BK (Emax 0.31±0.07 g) (Figure 4A,C). Des-Arg9-BK-induced paw oedema in ADX rats was also inhibited by previous treatment with PDCT (100 mg kg−1, i.p., an inhibitor of the activation of NF-κB) given once a day for 6 days after surgery (82±3%) (Figure 4B). Again, when evaluated in the response of portal vein, the treatment with PDTC significantly reduced the contractile response induced by des-Arg9-BK (Emax from 0.52±0.03 g to 0.35±0.04 g, P<0.05) (Figure 4D). Interestingly, the treatment of ADX rats with an association of submaximal doses of dexamethasone (0.05 mg kg−1, s.c.) plus PDTC (10 mg kg−1, i.p.) for 6 days (which alone had no effect) significantly reduced the oedema formation caused by des-Arg9-BK (82±5%) and also des-Arg9-BK-induced portal vein contraction (Emax 0.34±0.08 g, P<0.05) (Figure 5A,B).

Figure 4.

Dexamethasone and PDTC treatment inhibit ADX-induced increase on des-Arg9-BK response in vivo and in vitro. Des-Arg9-BK (50 nmol kg−1)-induced paw oedema in rats 7 days after adrenalectomy and treated 6 days with saline (Control), (A) dexamethasone (0.5 mg kg−1, s.c.) or (B) PDTC (100 mg kg−1, i.p.). Values represent the differences between volumes (in ml) of vehicle-injected (0.1 ml of PBS solution) and drug-injected paws. Contraction concentration response curves for des-Arg9-BK (1 – 3000 nM) of portal vein from rats 7 days after adrenalectomy 6 days treated with saline (Control), (C) dexamethasone (0.5 mg kg−1, s.c.) or (D) PDTC (100 mg kg−1, i.p.). Each point represents the mean±s.e.mean of 5 – 7 rats. In some cases the error bars are hidden within the symbols. Significantly different from control values *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (Student's unpaired t-test).

Figure 5.

The co-treatment with dexamethasone plus PDTC inhibit ADX-induced increase on des-Arg9-BK response in vivo and in vitro. (A) Des-Arg9-BK (50 nmol paw−1)-induced paw oedema in rats 7 days after adrenalectomy and treated 6 days with saline (Control) or dexamethasone (0.05 mg kg−1, s.c.) plus PDTC (10 mg kg−1, i.p.). Values represent the differences between volumes (in ml) of vehicle-injected (0.1 ml of PBS solution) and drug-injected paws. (B) Contraction concentration response curves for des-Arg9-BK (1 – 3000 nM) of portal vein from rats 7 days after adrenalectomy 6 days treated with saline (Control) or dexamethasone (0.05 mg kg−1, s.c.) plus PDTC (10 mg kg−1, i.p.). Each point represents the mean±s.e.mean of 5 – 7 rats. In some cases the error bars are hidden within the symbols. Significantly different from control values *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (Student's unpaired t-test).

Gel mobility shift assay with NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide

Figure 6A gives data from the NF-κB/DNA binding gel shift assays by using nuclear extracts of lungs obtained from SO or ADX rats (1 – 7 days after surgery). Nuclear extracts obtained from lungs of LPS-treated rats were used as positive control for NF-κB/DNA binding. Very low basal levels of NF-κB/DNA binding were detected in lung nuclear extracts obtained from SO rats (Figure 6A). After 5 days of surgical ablation of adrenal glands, there was an increase in the steady-state levels of NF-κB/DNA binding, an effect which was more pronounced in 7-day ADX rats (Figure 6A). Protein/DNA complexes obtained with lung nuclear extracts from 7-day ADX rats were displaced by an excess of unlabelled NF-κB, but not TFIID, double-stranded oligonucleotide, demonstrating the specificity of NF-κB/DNA interaction (Figure 6B). The activation of NF-κB in ADX rats was also confirmed when experiments were conducted with nuclear extracts of paw and heart tissues from SO or 7-day ADX rats (Figure 6C). In Figure 6D it is demonstrated that dexamethasone, PDTC or the association of very low doses of dexamethasone and PDTC treatment caused a complete inhibition of lung's NF-κB activation induced by adrenalectomy.

Figure 6.

Electromobility shift assay showing ADX-induced NF-κB activation in lung tissue. (A) Nuclear protein was extracted from lungs of rats challenged with LPS (8 mg kg−1, i.p., 60 min), utilised as a positive control, or sham-operated (SO) or ADX 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 or 7 days. The competition (B) study was performed using lung nuclear extract from ADX 7 days rats in the absence (7 ADX) or in the presence of excess of unlabelled NF-κB probe (0.9 pmol) (+NF-κB) or TFIID probe (0.9 pmol) (+TFIID). (C) Electromobility shift assay showing ADX-induced NF-κB activation in paw and heart tissue. (D) Effect of in vivo treatment with different inhibitors on NF-κB activation in lung nuclear extract. The position of NF-κB/DNA binding complex and free probe are marked.

Effects of adrenalectomy on B1 receptor mRNA expression

The removal of adrenal glands caused an induction of the expression of B1 receptor mRNA obtained from lung tissues (Figure 7). The receptor mRNA in lung was observed at 5 and 6 days after surgery, and the increment proved to be intensified on the seventh day after ADX (Figure 7). The quantification of bands confirmed the significant increased in levels of B1 receptor mRNA caused by the absence of adrenal glands, especially 7 days after the surgery (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

(A) RPA showing the time course of ADX-induced B1 kinin receptor mRNA expression in the lung. (B) Quantification of the RPA bands intensity. The β-actin mRNA served as the internal control. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7, days after ADX.

Discussion

The results of the present study provide, for the first time, considerable pharmacological and molecular evidence to suggest that endogenous glucocorticoids exert a pivotal role in controlling the expression of the rat B1 receptor.

Earlier studies have demonstrated that various procedures, such as tissue injury, application of noxious stimulus, certain cytokines, Freund's adjuvant, immune complex arthritis, chemical colitis or cystitis, heat stress, in vivo desensitization of B2 receptors, previous treatment of animals with LPS or long-term treatment with Mycobacterium bovis Calméte-Guérin (BCG) (Dray & Perkins, 1993; Davis et al., 1994; Campos & Calixto, 1995; Campos et al., 1996; 1997; Lagneux & Ribuot, 1997; Lecci et al., 1999, for review see: Marceau & Bachvarov, 1998) induce up-regulation of B1 receptors in many animal species. Either in vitro or in vivo treatment with the glucocorticoid dexamethasone or with protein synthesis inhibitors largely prevents B1 receptor up-regulation (for review see: Marceau, 1995; 1997). Both ourselves and other researchers have hypothesized that the endogenous glucocorticoids might exert an endogenous modulation of the B1 receptor expression, and such a mechanism could have clinical relevance in the control of chronic inflammatory processes.

In the present study, in vivo and in vitro pharmacological and molecular data demonstrate that the endogenous glucocorticoids have a critical role in controlling B1 receptor expression. This assumption derives from the view that suppression of circulating adrenal hormones, either by surgical (ablation of adrenal glands) or pharmacological (mitotane treatment) (Schulick & Brennan, 1977; Moore et al., 1980; Cai et al., 1995), resulted in a marked up-regulation of B1 agonist des-Arg9-BK-mediated contraction in portal vein or paw oedema formation. To explore further whether the up-regulation of B1 receptor in ADX rats involves the increase of B1 receptor expression, we employed a RPA and B1 kinin receptor encoding mRNA was measured in lung tissues of SO and ADX rats. These experiments revealed clearly that B1 receptor was expressed in lung of 5 – 7 day ADX rats, while lung of SO rats did not show B1 receptor mRNA expression. Such results are in accordance with the increase of functional B1 receptor-mediated responses, as noted both in vivo (paw oedema) and in vitro (portal vein contraction) pharmacological models. Confirming our previous studies carried out on rats treated with LPS, BCG, or with pro-inflammatory cytokines, or after complete in vivo desensitization of B2 receptor (Campos & Calixto, 1995; Campos et al., 1996; 1997; 1998), the increase in paw oedema caused by des-Arg9-BK in ADX rats is a specific phenomenon clearly mediated by activation of B1 (but not B2) receptors, as the selective B1 receptor antagonist des-Arg9-NPC 17731, but not the B2 selective antagonist HOE 140, almost completely inhibited des-Arg9-BK-induced oedema formation. Contrasting with results following acute systemic treatment of animals with LPS where the B1 receptor up-regulation is associated with the down-regulation of B2-mediated responses (Cabrini et al., 1996; Campos et al., 1996), the B1 receptor expression in ADX animals seems to be a quite specific phenomenon, since the B2 response induced by selective B2 agonist tyrosine8-BK did not differ between SO and ADX rats.

Confirming and extending previous observations (Campos et al., 1996; 1997), hormonal replacement of ADX animals with dexamethasone, for 6 consecutive days, greatly reduced the up-regulation of the B1 agonist des-Arg9-BK-mediated oedema formation and contraction of the rat portal vein in vitro. Such results further support the new concept indicating the de novo protein synthesis of the B1 receptor following surgical ablation of the adrenal glands, likely involves the suppression of cytokine synthesis and possibly further actions facilitating the B1 receptor expression (DeBlois et al., 1988; Galizzi et al., 1994; Levesque et al., 1995; for review see: Marceau, et al., 1998). In addition, confirming previous studies (Campos et al., 1997; 1998; Medeiros et al., 2000), both the metabolites derived from COX-2 and, to a lesser extent, those derived from COX-1, appear to largely contribute to the control of the des-Arg9-BK-mediated paw oedema in ADX animals. Similar results have been reported by Masferrer et al. (1992; 1994) who demonstrated that peritoneal macrophages obtained from ADX mice showed an increase of COX-2 mRNA and protein compared to SO animals, this effect being suppressed by dexamethasone replacement. These findings led the authors to suggest that, under normal conditions, endogenous glucocorticoids have an inhibitory action on inducible COX expression. In addition, it has been demonstrated that adrenalectomy enhances cytokine expression in several tissues such as spleen, pituitary and brain in mice (Goujon et al., 1996). Adrenalectomy also increases the sensitivity of mice to LPS-induced endotoxic shock (Bertini et al., 1988). It has been shown recently by several groups that glucocorticoids also interfere with some transcription factors involved in the inflammatory process, including the NF-κB/κB family and AP-1 (Scheinman et al., 1995; Auphan et al., 1995; Mckay & Cidlowski, 1998). Thus, the reduction of glucocorticoids might cause an exacerbation of inflammatory response related to increase of COX-2 expression or synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Bertini et al., 1988; Kujubu & Herschman, 1992; Masferrer et al., 1992; 1994).

NF-κB is a well-characterized DNA-binding factor controlled by regulatory proteins, known as a transcription factor, which has a relevant role in controlling the transcription of certain inflammatory genes, including cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and cell adhesion molecules, among others (Barnes & Adcock, 1997; Barnes & Karin, 1997). Normally, the NF-κB proteins are found in the cytoplasm as an inactive heterodimer, composed of two subunities p50 and p65 (relA), coupled to the inhibitory protein IκB-α. Once the cell is stimulated by inflammatory cytokines, the IκB-α is phosphorylated by specific protein kinases, causing its degradation, that then permits the NF-κB to migrate to the nucleus where it binds to specific κB portion at the promoter of the NF-κB-regulated genes and initiates gene transcription (Thanos & Maniatis, 1995; Baeuerle & Baltimore, 1996; Ghosh et al., 1998). There is now evidence showing that NF-κB exerts a pivotal role in regulating the molecular mechanisms which modulate the kinin B1 receptor expression in both in vivo and in in vitro studies. Ni et al. (1998) recently found a sequence containing an NF-κB-like binding site on the promoter of the B1 receptor in the vascular smooth muscle cells stimulated by inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, TNFα or by LPS. Very similar observations have been made by Schanstra et al. (1998), indicating that expression of kinin B1 receptors in cultured human lung fibroblasts in response to IL-1β is modulated at the transcriptional level by the activation of NF-κB. Recent results from our group have given evidence for the in vivo participation of NF-κB in the process of up-regulation of B1 receptors in animals treated with either IL-1β or with TNFα (Campos et al., 1999). The findings of the present study clearly demonstrate that either surgical ablation of adrenal glands, carried out 7 days prior, or chemical ADX, performed through daily treatment of rats with anticancer drug mitotane once a day for 10 days, induces an increase in B1 receptor expression. Electromobility shift assay indicate that in the lung, the change in B1 receptor expression after surgical ablation of adrenal glands is accompanied by an increase in NF-κB/DNA binding. Further confirmation for the involvement of the NF-κB on B1 receptor expression after bilateral ADX came from results showing a marked inhibition of des-Arg9-BK-mediated rat paw oedema, portal vein contraction and in nuclear extracts of lung tissues from PDCT or dexamethasone-treated rats. Although the precise mechanism for the biological effects of PDTC is still controversial, several in vitro and in vivo studies showed that PDTC was a potent inhibitor of NF-κB, but had no effect on AP-1, CREB, specific protein (Sp-1), or octamer-biding proteins (Schreck et al., 1992; Liu & Malik, 1999; Muller et al., 2000). Muller et al. (2000) have recently reported that the in vivo treatment of rats with PDTC although was found effective in inhibiting NF-κB, it failed to modify AP-1 or any other transcription factor. As the same effect of PDTC on NF-κB activation was also obtained when the activation was caused by adrenalectomy, we could speculate that the up-regulation of B1 receptor in our study possibly involve only the activation of NF-κB, and not AP-1 nuclear factor.

The fact that the association of very low doses of dexamethasone with PDCT, that alone had no effect, but together produced the greatest inhibition of des-Arg9-BK-mediated response, is very interesting and suggests that both drugs act via distinct pathways in the process of B1 receptor expression. The association of low doses of NF-κB inhibitor and corticosteroid may represent a therapeutic strategy in the sense of reducing side effects of monotherapy in the management of inflammatory processes. Similar synergistic effect between association of NF-κB inhibitor and dexamethasone have been reported both in vivo (Fröde-Saleh & Calixto, 2000) and ex vivo (Medeiros et al., 2000).

In summary, results from the present study, based on both functional and molecular findings, have demonstrated for the first time that glucocorticoid deficiency following either chemical or surgical ablation of adrenal glands dramatically results in a marked expression of kinin B1 receptor through an NF-κB-mediated mechanism. Taken together, these findings support the notion that besides the well-known pharmacological effects of glucocorticoids in controlling the inflammatory responses, their action is probably, at least in part, related to the modulation of kinin B1 receptor expression.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from CNPq, FINEP and FAPESP. K.S. Tratsk is an undergraduate medical student receiving a grant from CNPq (Brazil), V.F. Merino is a postgraduate student receiving a grant from FAPESP and D.A. Cabrini and M.M. Campos are PhD students in Pharmacology receiving a grant from CAPES and CNPq (Brazil), respectively.

Abbreviations

- ADX

adrenalectomized

- BK

bradykinin

- LPS

bacterial lipopolysaccharide

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- RPA

ribonuclease protection assay

- SO

sham-operated

References

- AUPHAN N., DIDONATO J.A., ROSETTE C., HELMBERG A., KARIN M. Immunosuppression by glucocorticoids: inhibition of NF-κB activity through induction of IκB synhesis. Science. 1995;270:286–290. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J., ADOCK I.M. NF-κB: a pivotal role in asthma and a new target for therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:47–50. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)89796-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J., KARIN M. Nuclear factor-κB–A pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. New Eng. J. Med. 1997;336:1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAUERLE P.A., BALTIMORE D. NF-κB: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERTINI R., BIANCHI M., GHEZZI P. Adrenalectomy sensitizes mice to the lethal effects of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor. J. Exp. Med. 1988;167:1708–1712. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.5.1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOUTHILLIER J., DEBLOIS D., MARCEAU F. Studies on the induction of pharmacological responses to des-Arg9-bradykinin in vitro and in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987;92:257–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11319.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CABRINI D.A., KYLE D.J., CALIXTO J.B. A pharmacological analysis of receptor subtypes and the mechanisms mediating the biphasic response induced by kinins in the stomach fundus in vitro. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;277:299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAI W., COUNSELL R.E., DJANEGARA T., SCHTEINGART D.E., SINSHEIMER J.E., WOTRING L.L. Metabolic activation and binding of mitotane in adrenal cortex homogenates. J. Pharm. Sci. 1995;84:134–138. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600840203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALIXTO J.B., CABRINI D.A., FERREIRA J., CAMPOS M.M. Kinins and pain and inflammation. Pain. 2000;87:1–5. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPOS A.H., CALIXTO J.B. Mechanisms involved in the contractile responses of kinins in rat portal vein rings: mediation by B1 and B2 receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;268:902–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPOS M.M., CALIXTO J.B. Involvement of B1 and B2 receptors in bradykinin-induced rat paw oedema. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:1005–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPOS M.M., HENRIQUES M.G.M.O., CALIXTO J.B. The role of B1 and B2 receptors in oedema formation after long-term treatment with Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:502–508. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPOS M.M., SOUZA G.E.P., CALIXTO J.B. Up-regulation of B1 mediating des-Arg9-BK-induced rat paw oedema by systemic treatment with bacterial endotoxin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:793–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPOS M.M., SOUZA G.E.P., CALIXTO J.B. Modulation of kinin B1 but not B2 receptor-mediated rat paw edema by IL-1beta and TNFalpha. Peptides. 1998;19:1269–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(98)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPOS M.M., SOUZA G.E.P., CALIXTO J.B. In vivo B1 kinin-receptor upregulation. Evidence for involvement of protein kinases and nuclear factor-κB pathaways. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:1851–1859. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIS A.J., KELLY D., PERKINS M.N. The induction of des-Arg9-bradykinin-mediated hyperalgesia in the rat by inflammatory stimuli. Br. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1994;27:1793–1802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEBLOIS D., BOUTHILLIER J., MARCEAU F. Effect of glucocorticoids, monokines and growth factors on the spontaneously developing responses of the rabbit isolated aorta to des-Arg9-bradykinin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;93:969–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRAY A., PERKINS M.N. Bradykinin and inflammatory pain. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EGGERIX D., RASPE E., BERTRAND D., VASSART G., PARMENTIER M. Molecular cloning, functional expression and pharmacological characterization of human bradykinin B2 receptor gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;187:1306–1313. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90445-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FARMER S.G., BURCH R.M. Biochemical and molecular pharmacology of kinin receptors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1992;32:511–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.32.040192.002455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLOWER R.J., PARENTE L., PERSICO P., SALMON J.A. A comparison of the acute inflammatory response in adrenalectomised and sham-operated rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986;87:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALLIZI J.P., BODINIER M.C., CHAPELAIN B., LY S.M., COUSSY L., GIRAUD S., NEILAT G., JEAN T. Up-regulation of [3H]-des-Arg10-kallidin binding to the bradykinin B1 receptor by interleukin-1β in isolated smooth muscle cells: correlation with B1 agonist-induced PGI2 production. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;113:389–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHOSH S., MAY M.J., KOPP E.B. NF-κB and Rel proteins: evolutionary conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1998;16:225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOUJON E., PARNET P., LAYE S., COMBE C., DANTZER R. Adrenaelctomy enhances pro-inflammatory cytokines gene expression, in the spleen, pituitary and brain of mice in response to lipopolysaccharide. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1996;36:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00242-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL J.M. Bradykinin receptors: pharmacological properties and biological roles. Pharmacol. Ther. 1992;56:131–190. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90016-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HESS J.F., BORKOWSKI J.A., MACNEIL T., STONESIFER G.Y., FRAHER J., STRADER C.D., RANSOM R.W. Differential pharmacology of cloned human and mouse B2 bradykinin receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HESS J.F., BORKOWSKI J.A., YOUNG G.S., STRADER C.D., RANSOM R.W. Cloning and pharmacological characterization of a human bradykinin (bradykinin-2) receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;184:260–268. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91187-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUJUBU D.A., HERSCHMAN H.R. Dexamethasone inhibits mitogen induction of the TIS10 prostaglandin synthase/cyclooxygenase gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:7991–7994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAGNEUX C., RIBOUT C. In vivo evidence for B1-receptor synthesis induction by heart stress in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:1045–1046. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LARRIVÉE J.-F., BACHVAROV D.R., HOULE F., LANDRY J., HOUT J., MARCEAU F. Role of the mitogen-activated protein kinases in the expression of the kinin B1 receptors induced by tissue injury. J. Immunol. 1998;160:1419–1426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LECCI A., MEINI S., PATACCHINI R., TRAMONTANA M., GIULIANI S., CRISCUOLI M., MAGGI C.A. Effect of dexamethasone on cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis in rats: lack of relation with bradykinin B1 receptor-mediated motor responses. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;369:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVESQUE L., LARRIVÉ J.-F., BACHVAROV D.R., RIOUX F., DRAPEAU G., MARCEAU F. Regulation of kinin-induced contraction and DNA synthesis by inflammatory cytokines in the smooth muscle of the rabbit aorta. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:1673–1679. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU S.F., YE X., MALIK A.B. In vivo inhibition of nuclear factor-κB activation prevents inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and systemic hypotension in a rat model of septic shock. J. Immunol. 1997;159:3976–3983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU S.F., MALIK A.B. Inhibition of NF-κβ activation by pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate prevents in vivo expression of proinflammatory genes. Circulation. 1999;100:1330–1337. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.12.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCEAU F. Kinin B1 receptors: a review. Immunopharmacology. 1995;30:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(95)00011-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCEAU F.Kinin B1 receptor induction and inflammation The Kinin system 1997Academic Press: New York; 143–153.ed. Farmer, S.G. pp [Google Scholar]

- MARCEAU F., BACHVAROV D.R. Kinin receptors. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 1998;16:385–401. doi: 10.1007/BF02737658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCEAU F., HESS J.F., BACHVAROV D.R. The B1 receptors for kinins. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:357–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCEAU F., LARRIVÉ J.-F., SAINT-JACQUES E., BACHVAROV D.R. The kinin B1 receptor: an inducible G protein coupled receptor. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1997;75:725–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASFERRER J.L., REDDY S.T., ZWEIFEL B.S., SEIBERG K., NEEDLEMAN P., GILBERT R.S., HERSCHMAN H.R. In vivo glucocorticoids regulate cyclooxigense-2 but not cyclooxigenase-1 in peritoneal macrophages. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;270:1340–1344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASFERRER J.L., SEIBERT K., ZWEIFEL B., NEEDLEMAN P. Endogenous glucocorticoids regulate an inducible cyclooxigenase enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:3917–1921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCEACHERN A.E., SHELTON E.R., BHAKTA S., OBERNOLTE R., BACH C., ZUPPAN P., FUJISAKA J., ALDRICH R.W., JARNAGIN K. Expression cloning of a rat B2 receptor. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:7724–7728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCKAY L.I., CIDLOWSKI J.A. Cross-talk between nuclear factor-κB and the steroid hormone receptors: mechanisms of mutual antagonism. Mol. Endoc. 1998;12:45–56. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.1.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEDEIROS R., CABRINI D.A., CALIXTO J.B.The role of nuclear factor-κB, kinases and cyclooxygenase-2 pathways in up-regulation of b1 receptor-mediated contraction of the rabbit aorta Regul. Peptides 2000. in press [DOI] [PubMed]

- MOORE R.N., PENNEY D.P., AVERILL K.T. Fine structural and biochemical effects of aminoglutethimide and o,p′-DDD on rat adrenocortical carcinoma 494 and adrenals. Anat. Rec. 1980;198:113–124. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091980109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLER D.N., DECHEND R., MERVEELA E.M.A., PARK J.-K., SCHMIDT F., FIEBELER A., THEUER J., BREU V., GANTEN D., HALLER H., LUFT F.C. NF-κB inhibition ameliorates angiotensin II-induced inflammatory damage in rats. Hypertension. 2000;35:193–201. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NI A., CHAO L., CHAO J. Transcription factor nuclear factor-κB regulates the inducible expression of the human B1 receptor gene in inflammation. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1998a;273:2784–2791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NI A., CHAI K.X., CHAO L., CHAO J. Molecular cloning and expression of rat bradykinin B1 receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1998b;1442:177–185. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PESQUERO J.B., PESQUERO J.L., OLIVEIRA S.M., ROSCHER A.A., METZGER R., GANTEN D., BADER M. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a mouse bradykinin B1 receptor gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;220:219–225. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REGOLI D., BARABÉ J. Pharmacology of bradykinin and related kinins. Pharmacol. Res. 1980;32:1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REGOLI D., MARCEAU F., LAVIGNE J. Induction of B1-receptors for kinins in the rabbit by a bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1981;71:105–119. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90391-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRÖDE-SALEH T.S., CALIXTO J.B. Synergistic antiinflammatory effect of NF-κB inhibitors and steroid or non steroid antiinflammatory drugs in the pleural inflammation induced by carrageenan in mice. Inflamm. Res. 2000;49:330–337. doi: 10.1007/PL00000213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHANSTRA J.P., BATALLE E., CASTAÑO M.E.M., BARASCUD Y., HIRTZ C., PESQUERO J.B., PECHER C., GAUTHIER F., GIROLAMI J.-P., BASCANDS J.-L. The B1-agonist [des-Arg10]-kallidin activates transcription factor NF-κB and induces homologous up-regulation of the bradykinin B1-receptor in cultured human lung fibroblasts. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:2080–2091. doi: 10.1172/JCI1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHEINMAN R.I., COGSWELL P.C., LOFQUIST A.K., BALDWIN A.S. Role of transcriptional activation of IκBα in mediation of immunosuppression by glucocorticoids. Science. 1995;270:283–286. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRECK R., MEIER B., MANNEL D.N., DROGE W., BAUERLE P.A. Dithiocarbamates as potent inhibitors of nuclear factor kappa B activation in intact cells. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 1992;175:1181–1194. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.5.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHULICK R.D., BRENNAN M.F. Adrenocortical carcinoma. JAMA. 1977;238:2527–2532. [Google Scholar]

- SHAMES B.D., MELDRUM D.R., SELZMAN C.H., PULIDO E.J., CAIN B.S., BANERJEE A., HARKEN A.H., MENG X. Increased levels of myocardial IκB-alpha protein promote tolerance to endotoxin. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:H1084–H1091. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.3.H1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THANOS D., MANIATIS T. NF-κB: a lesson in family values. Cell. 1995;80:529–532. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG X., TAYLOR L., POLGAR P. Mechanisms in the transcriptional regulation of bradykinin B1 receptor gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:10763–10770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZIMMERMAN M. Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain. 1993;16:109–119. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]