Abstract

We measured the effects of agonists and antagonists of metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors (types 1 and 5) on NMDA-induced depolarization of mouse cortical wedges in order to characterize the mGlu receptor type responsible for modulating NMDA responses. We also characterized a number of mGlu receptor agents by measuring [3H]-inositol phosphate (IP) formation in cortical slices and in BHK cells expressing either mGlu 1 or mGlu 5 receptors.

(S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG), an agonist of both mGlu 1 and mGlu 5 receptors, at concentrations ranging from 1 – 10 μM, enhanced up to 105±15% the NMDA-induced depolarization. Larger concentrations (100 – 300 μM) of the compound were inactive in this test. When evaluated on [3H]-IP synthesis in cortical slices or in cells expressing either mGlu 1 or mGlu 5 receptors, DHPG responses (1 – 300 μM) increased in a concentration-dependent manner.

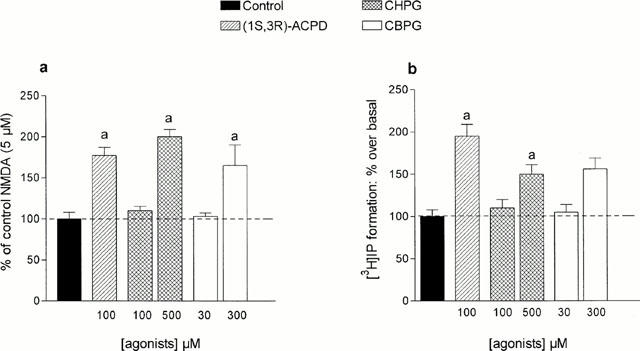

(RS)-2-chloro-5-hydroxyphenylglycine (CHPG) and (S)-(+)-2-(3′-carboxybicyclo[1.1.1]pentyl)-glycine (CBPG), had partial agonist activity on mGlu 5 receptors, with maximal effects reaching approximately 50% that of the full agonists. These compounds, however, enhanced NMDA-evoked currents with maximal effects not different from those induced by DHPG. Thus the enhancement of [3H]-IP synthesis and the potentiation of NMDA currents were not directly related.

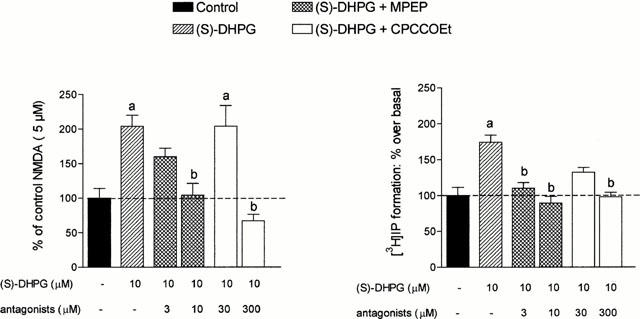

2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP, 1 – 10 μM), a selective mGlu 5 receptor antagonist, reduced DHPG effects on NMDA currents. 7-(hydroxyimino)cyclopropan[b]-chromen-1a-carboxylic acid ethylester (CPCCOEt, 30 μM), a preferential mGlu 1 receptor antagonist, did not reduce NMDA currents.

These results show that mGlu 5 receptor agonists enhance while mGlu 5 receptor antagonists reduce NMDA currents. Thus the use of mGlu 5 receptor agents may be suggested in a number of pathologies related to altered NMDA receptor function.

Keywords: Metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), epilepsy, neurodegeneration, MPEP, CPCCOEt, CBPG, DHPG

Introduction

Ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors are present in most excitatory synapses of the mammalian central nervous system (Lujàn et al., 1996; Kim & Huganir, 1999). The ionotropic receptors mediates the phasic components of neurotransmission and may be classified, on the basis of their preferential agonists in N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), (S) -α-amino -4 -bromo -3 -hydroxy -5 -isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) and kainate (KA) types (Collingridge & Lester, 1989; Hollmann & Heinemann, 1993; Dingledine et al., 1999). Metabotropic (mGlu) receptors seem to be able to regulate synaptic efficacy and are usually classified in three major groups (1 – 3) on the basis of their molecular structures, G-protein coupling and pharmacological properties (Nakanishi, 1992; Schoepp & Conn, 1993; Pin & Duvoisin, 1995).

In the last 20 years, considerable attention has been given to the NMDA receptor ion channel complex because of its unusual properties and role in brain physiology. This complex allows Ca2+ influx into the neurons only when the membrane is depolarized and the receptors bind both glutamate and glycine (Nowak et al., 1984; Johnson & Ascher, 1987; Kleckner & Dingledine, 1988). Functional NMDA receptors are composed of a common NR1 subunit and one of four NR2 (NR2A-D) subunits combined to make a heteromeric complex (Kutsuwada et al., 1992; Monyer et al., 1992). A reduction in the function of the NMDA receptor complex has been associated with schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric disorders (Carlsson et al., 1997; Mohn et al., 1999). On the contrary, an excessive activation of NMDA receptors is thought to contribute to cell death associated with a variety of pathological conditions, including epilepsy, stroke and neurodegenerative disorders (Olney, 1983; Meldrum & Garthwaite, 1990; Olney, 1990; Choi, 1992). Competitive and non-competitive NMDA receptor agents have become available in the last two decades but unfortunately, in the clinical arena, their use has been prevented by numerous side effects. New safer approaches aimed at modulating the function of the NMDA receptor complex are necessary for a number of therapeutic applications.

It has been repeatedly shown, both in native and in recombinant systems, that NMDA evoked responses are significantly increased by the non-specific mGlu receptor agonist (1S,3R)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (1S,3R-ACPD) (Aniksztein et al., 1992; Kelso et al., 1992; Cerne & Randic, 1992; Bleakman et al., 1992; Schoepp & Conn, 1993; Harvey & Collingridge, 1993; O'Connor et al., 1994; Nakanishi, 1994; Bond & Lodge, 1995; Jones & Headley, 1995). Most available studies in this field have shown that the enhancement of NMDA responses is due to a protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation of one of the receptor subunits, thus suggesting that group 1 mGlu receptors are involved in this type of receptor-receptor interaction (Ugolini et al., 1997; 1999). Group 1 mGlu receptors might be divided into mGlu 1 and mGlu 5, and are selectively activated by DHPG (Ito et al., 1992). We reported that DHPG (100 μM) was not able to enhance NMDA depolarization of cortical wedges and suggested that other unknown mGlu receptors could possibly potentiate NMDA responses (Mannaioni et al., 1996). The availability of new selective mGlu receptor agents prompted us to reconsider our observation and we report here that mGlu 5 receptors are responsible for the 1S,3R-ACPD-mediated potentiation of NMDA responses. We also report that the mGlu receptor-induced enhancement of NMDA-responses does not correlate with the mGlu receptor-induced activation of phosphoinositide (PI) metabolism.

Methods

Materials

1S,3R-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (1S,3R-ACPD), (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG), (RS)-2-chloro-5-hydroxyphenylglycine (CHPG), 7-(hydroxyimino)cyclopropan[b]-chromen-la-carboxylic acid ethylester (CPCCOEt) and 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP) were purchased from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, U.K.). (S)-(+)-2-(3′-carboxybicyclo[1.1.1]pentyl)-glycine (CBPG) was synthesized as previously described (Pellicciari et al., 1996). myo-[2-3H(N)]-inositol (10 – 20 Ci.mmol−1) was from Amersham (Milan, Italy) and Dowex AG-1-X 8 anion exchange resin (100 – 200 mesh) was from Sigma Chimica (Milan, Italy). Tissue culture reagents were obtained from Sigma Chimica (Milan, Italy), Gibco (Milan, Italy) and Nunc (Roskilde, Denmark). All other reagents were of analytical grade and obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Transfected cell cultures

Baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells stably transfected with mGlu1a or mGlu5a (Thomsen et al., 1992; 1993) were provided by Dr Thomsen and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 5% dialyzed foetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 0.05 mg ml−1 gentamicin and 0.1 mg ml−1 neomycin in a humidified atmosphere (95% air, 5% CO2) at 37°C. In addition, the incubation medium of the transfected cells was supplemented with G418 and methotrexate. Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere (95% air, 5% CO2) at 37°C and subcultured (every 2nd day) using 0.05% trypsin/EDTA.

Preparation of cortical slices

The preparation of brain slices from the mouse cortex was performed using the methods previously described for the rat (Lombardi et al., 1993; 1996). Briefly: the mouse cortex was rapidly dissected and placed into ice-cold Krebs-bicarbonate buffer (in mM): NaCl 122; KCl 3.1; MgSO4 1.2; KH2PO4 0.4; CaCl2 1.3; NaHCO3 25 and glucose 10, gassed with 95% O2/ 5% CO2. Slices (350 μm thick) were then prepared by use of a McIlwain tissue chopper and placed in gassed Krebs-bicarbonate solution for at least 1 h at 37°C in order to allow functional recovery.

Measurements of second messengers

The assay conditions for measurements of PLC-catalysed [3H] inositol phosphate (IP) formation in transfected cells expressing mGlu receptors (Thomsen et al., 1993) or in brain slices (Pellegrini-Giampietro et al., 1988) were previously reported.

Preparation of cortical wedges

The cortical wedge preparation described by Harrison & Simmonds (1985) and modified by Burton et al. (1988) was used as previously described (Carlà & Moroni, 1992). Briefly: wedges obtained from white Swiss mice (male 15 – 25 g) were placed in a two-compartment bath and silicone grease was placed between the two portions of the bath. The wedges were incubated at room temperature and perfused with Krebs solution (mM): NaCl 135; CaCl2 2.4; KH2PO4 1.3; MgCl2 1.2; NaHCO3 16.3 and glucose 7.7, gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at a flow rate of 2 ml min−1. After stabilization, the grey matter was perfused with a Mg2+-free medium. NMDA and AMPA were repeatedly applied for 2 min every 15 min, whereas the other compounds were applied continuously. The NMDA-induced variations of the d.c. potentials between the two compartments were monitored via Ag/AgCl electrodes and displayed on a chart recorder. The preparations were initially stabilized by repeated application of 10 μM NMDA, a concentration which gave a sub-maximal response but which did not significantly reduce the response of subsequent applications of the agonist (Mannaioni et al., 1996).

Results

Characterization of mGlu receptor agonists and antagonists in BHK cells expressing mGlu 1 or mGlu 5 receptors

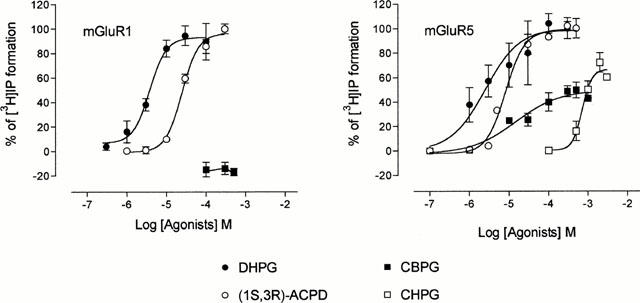

The pharmacological profile of a number of agonists and antagonists known to interact with group 1 mGlu receptors was investigated by measuring drug-induced changes of PI metabolism in mouse cortical wedges and in BHK cells expressing either mGlu 1 or mGlu 5 receptors. Increasing concentrations of 1S,3R-ACPD and DHPG, applied to cells expressing either mGlu 1 or mGlu 5 receptors, stimulated PI metabolism up to the level obtained with glutamate (100 μM). They were therefore considered full agonists of mGlu 1 and mGlu 5 receptors. On the contrary, CHPG and CBPG (both up to 1 mM) did not stimulate PI metabolism in cells expressing mGlu 1 receptors and in cells expressing mGlu 5 receptors their maximal effects reached approximately 50% those obtained with glutamate. They were therefore considered partial mGlu 5 receptor agonists (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Concentration-response curves for [3H]-IP formation stimulated by DHPG, (1S,3R)-ACPD, CBPG, and CHPG in BHK cells expressing mGlu 1 or mGlu 5 receptors. In each experiment, maximal [3H]-IP formation was induced with glutamate (100 μM) and considered 100%. Glutamate raised [3H]-IP formation from 6300±400 to 21,500±1500 d.p.m mg−1 protein in cells expressing mGlu 1 receptors and from 6950±720 to 31,800±4500 d.p.m mg−1 protein in cells expressing mGlu 5 receptors. The other values were calculated accordingly and each point represents this mean percentage±s.e.mean of at least three experiments conducted in duplicate. *P<0.01.

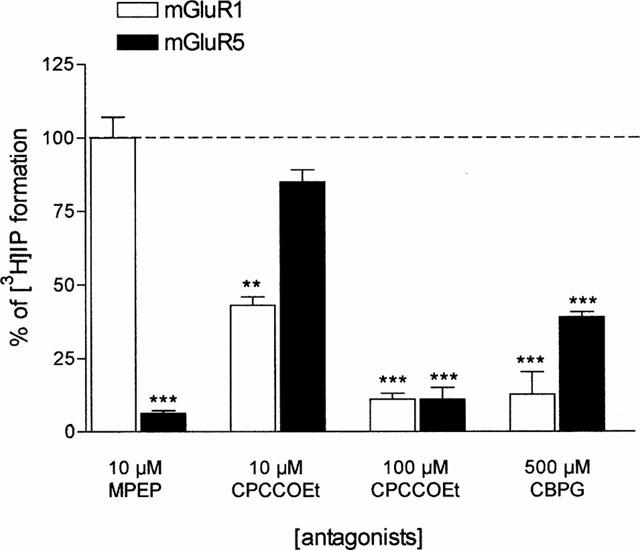

The antagonists we characterized in BHK cells expressing either mGlu 1 or mGlu 5 receptors were MPEP, CPCCOEt and CBPG. Figure 2 shows that MPEP was a potent and selective mGlu 5 receptor antagonist with no activity on mGlu 1 receptors (up to 10 μM). CPCCOEt preferentially antagonized mGlu 1 over mGlu 5 receptors, but its selectivity was relatively poor because at 100 μM it completely antagonized 1S,3R-ACPD effects on both mGlu 1 and mGlu 5 receptors. Finally, as previously reported (Mannaioni et al., 1999), CBPG was a potent antagonist of mGlu 1 and a partial agonist of mGlu 5 receptors. At large concentrations (500 μM) it also reduced the 1S,3R-ACPD stimulation of PI hydrolysis in BHK cells expressing mGlu 5 receptors (see Figure 2). When different concentrations of 1S,3R-ACPD, DHPG, CHPG and CBPG were tested on the increase of PI hydrolysis in mouse cortical slices, the maximal increase obtained with 1S,3R-ACPD (100 μM) was 190±12% over the basal values; that obtained with DHPG (100 μM) was 170±10%; with CHPG (500 μM) was 150±7 and with CBPG (300 μM) was 153±6% (means±s.e.mean of five experiments conducted in duplicate).

Figure 2.

Antagonism of (1S,3R)-ACPD (100 μM) induced [3H]-IP formation in BHK cells expressing mGlu1 or mGlu 5 receptors: effects of MPEP, CPCCOEt and CBPG. Each bar represents [3H]-IP formation calculated as a percentage and is the mean±s.e.mean obtained in three experiments conducted in triplicate. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Effects of mGlu 5 receptor agents in cortical wedges

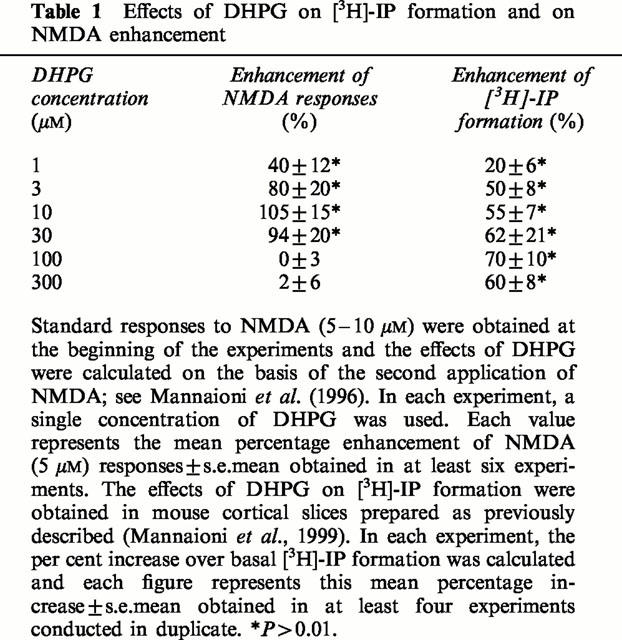

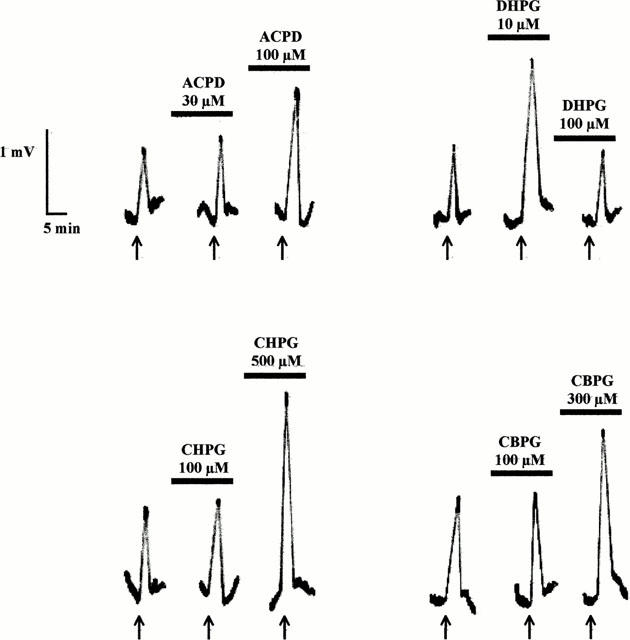

The depolarization induced by NMDA, but not that induced by AMPA or KA may be strongly enhanced by 1S,3R-ACPD (30 – 300 μM). This enhancement has a slow onset, a relatively long duration and has been ascribed to an increased affinity of NMDA for its recognition site (the maximal NMDA effects were not increased; Mannaioni et al., 1996). In the present series of experiments, we report that low concentrations (1 – 10 μM) of DHPG (see Table 1) and fully active concentrations of CHPG and CBPG also increased NMDA effects (Figures 3 and 4). The maximal degree of enhancement of NMDA-induced depolarization observed in the presence of the partial mGlu 5 agonists was no different than that observed in the presence of the full agonists 1S,3R-ACPD or DHPG. Furthermore, large concentrations (100 – 300 μM) of DHPG increased PI turnover without potentiating NMDA effects (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of DHPG on [3H]-IP formation and on NMDA enhancement

Figure 3.

Records of typical experiments showing the effects of 1S,3R-ACPD, DHPG, CHPG and CBPG on NMDA responses. The mGlu receptor agents were superfused for at least 15 min before challenging the cortical wedges with NMDA 5 μM. NMDA was applied for 2 min every 15 min. See Mannaioni et al. (1996) for details.

Figure 4.

Effects of (1S,3R)-ACPD, CHPG and CBPG on NMDA-induced depolarization and on [3H]-IP formation in the mouse cortex. (a) The potentiation of NMDA responses was calculated as previously described (Mannaioni et al. 1996). Each column represents the mean percentage increase±s.e.mean obtained in at least five experiments. a : P<0.05 vs controls (100%). (b) Increase of basal [3H]-IP formation induced by (1S,3R)-ACPD, CBPG and CHPG in mouse cortical slices. Each column represents the mean percentage increase±s.e.mean obtained in at least four experiments. a: P<0.05 vs controls.

We then investigated the effects of mGlu antagonists and we found that MPEP, at concentrations that selectively interacted with mGlu 5 receptors (1 – 10 μM), reduced the DHPG-induced enhancement of NMDA depolarization (see: Figures 2 and 5). On the contrary, concentrations of CPCCOEt (up to 30 μM) that selectively interacted with mGlu 1 receptors did not antagonize this enhancement. Larger concentrations (300 μM) of CPCCOEt, however, were sufficient to antagonize both mGlu 1 and mGlu 5 receptors and also reduced the NMDA potentiating effects of DHPG (see: Figures 2 and 5). In line with these findings, low concentrations of CBPG (10 μM), that selectively antagonized mGlu 1 receptors, did not modify the DHPG (10 μM) enhancement of the NMDA (5 μM)-induced depolarization.

Figure 5.

(a) Effects of mGlu receptor antagonists on the potentiation of NMDA responses induced by DHPG. The columns represent the per cent potentiation of DHPG obtained in the presence of antagonists. Each column represents the mean percentage increase±s.e.mean obtained in at least three experiments. (b) Effects of MPEP and CPCCOEt on [3H]-IP formation in mouse cortical slices. In each experiment, basal [3H]-IP formation was considered as 100% and the other values were calculated accordingly. Each column represents the mean percentage increase±s.e.mean obtained in at least three experiments. (a) P<0.05 vs control; (b) P<0.05 vs DHPG treated slices.

Discussion

Our experiments show that, in the mammalian cortex, it is possible to modulate NMDA receptor function with selective mGlu 5 receptor agonists and antagonists. The agonists enhance NMDA-depolarization and the antagonists reduce this enhancement. The possibility of safely modulating NMDA receptor function with compounds that do not directly interact with the NMDA receptor complex seems of particular interest for pharmacologists since both an excessive or a reduced function of the complex have been associated with major CNS pathologies. It has been previously reported that 1S,3R-ACPD is a full agonist of most mGlu receptor subtypes (Schoepp & Conn, 1993), that DHPG selectively interacts with group 1 mGlu receptors (Ito et al., 1992; Schoepp et al., 1994), that CHPG may activate, with low affinity, mGlu 5 but not mGlu 1 receptors (Doherty et al., 1997) and that CBPG is an agonists of mGlu 5 and an antagonist of mGlu1 receptors. In previous experiments we showed that the potency of group 1 mGlu agents tested on PI hydrolysis in recombinant receptors expressed in BHK cells was not significantly different than that found in native receptors expressed in mouse or rat cortical slices (Mannaioni et al., 1999). While 1S,3R-ACPD and DHPG behave as full mGlu 5 agonists, CHPG and CBPG behave as partial agonists, and their maximal effect was approximately 50% that of glutamate (see Figure 1). The maximal degree of enhancement of NMDA (5 μM) effects caused by the full or the partial mGlu 5 agonists, however, was no different, thus suggesting that a partial activation of mGlu 5 receptors is sufficient to saturate the process leading to enhanced NMDA responses. In addition, when relatively large concentrations (above 30 μM) of DHPG were used, PI hydrolysis was maximally stimulated but no enhancement of NMDA effects was detected (see: Table 1 and Mannaioni et al., 1999). It seems, therefore, that the enhancement of [3H]-IP synthesis and the potentiation of NMDA currents are not directly related.

It has been previously demonstrated that NMDA potentiation may be mediated by an increased phosphorylation of the NMDA receptor complex leading to an increased affinity of the complex for its agonist (Mannaioni et al., 1996; Pisani et al., 1997; Ugolini et al., 1997). Not all NMDA receptor subtypes are affected in the same manner by an increased activity of mGlu receptors. In fact, when the NR2C subunit is present (for instance in the granule cells of the cerebellum), group 1 mGlu receptor agonists reduce the NMDA-mediated responses (Pizzi et al., 1999). It is also interesting to note that while the process activated by mGlu 5 agonists may lead to phosphorylation of proteins belonging to the NMDA receptor complex, activation of the NMDA receptor complex may regulate the phosphorylation state and the functional responses of mGlu 5 receptors, thus suggesting that these two receptor types interact in a coordinated manner in order to finely tune the synaptic responses (Alagarsamy et al., 1999).

The involvement of mGlu 5 receptors in the enhancement of NMDA responses was supported also by the observation that MPEP (3 – 10 μM), at concentrations that selectively interacted with mGlu 5 receptors (see: Figure 5 and Gasparini et al., 1999), completely prevented this enhancement. Larger concentrations of MPEP (>150 μM), however, decreased the NMDA-induced depolarization, suggesting a direct interaction of the compound with the NMDA receptor complex. Another mGlu receptor antagonist we tested was CPCCOEt, a non-competitive mGlu 1 antagonist, that only at concentrations above 100 μM was able to antagonize also mGlu 5 receptors (see Figure 2, see also Casabona et al., 1997). We found that low concentrations of CPCCOEt did not reduce the effects of DHPG on NMDA responses while, at larger concentrations (300 μM) that were able to interact with mGlu 5 receptors, CPCCOEt reduced these effects. Similar results were obtained with CBPG, a potent mGlu 1 antagonist with partial agonist activity on mGlu 5 receptors (see Figure 3 and Mannaioni et al., 1999). The use of appropriate concentrations of this compound confirmed that the receptor subtype involved in the enhancement of NMDA responses was mGlu 5 and not mGlu 1.

It has been previously observed that mGlu receptor agonists facilitate NMDA responses in Xenopus oocytes injected with rat brain mRNA (Kelso et al., 1992), in various spinal cord preparations (Bleakman et al., 1992; Bond & Lodge, 1995; Ugolini et al., 1997) and in slices of the hippocampus and the striatum (Aniksztein et al., 1992; Cerne & Randic, 1992; Harvey & Collingridge, 1993). Our experiments are in line with these observations, extend the possibility of modulating NMDA responses in the mammalian cortex and characterize the receptor subtype involved. In view of the importance of NMDA receptors in the learning process, it is possible to predict that selective stimulation of mGlu 5 receptors could be a new strategy for the treatment of learning pathologies. In support of this proposal it has been shown that mice deprived of mGlu 5 receptors with gene targeting approaches have significant learning problems (Lu et al., 1997). It has been also proposed that a reduced function of cortical NMDA receptors may be responsible for several symptoms and for the cognitive disturbances commonly observed in patients with schizophrenia (Carlsson, 1988; Javitt & Zukin, 1991). Interestingly, mGlu 5 receptors are particularly abundant in the mammalian cortex (Abe et al., 1992; Shigemoto et al., 1993) and their expression dramatically decreases during development (Casabona et al., 1997), when these symptoms became evident.

On the other hand, excessive activation of NMDA receptors has been involved in epilepsy, stroke, neurodegenerative disorders and neuropathic pain (Olney, 1983; 1990; Meldrum & Garthwaite, 1990; Choi, 1992; Wiesenfeld-Hallin, 1998). The use of mGlu 5 antagonists may be of therapeutic values in those pathological conditions. Experiments aimed at testing these hypotheses are now in progress with the use of selective mGlu 5 receptor agents.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the University of Florence, CNR, MURST and the European Union (Biomed 2 project DMH4-CT96-0028).

Abbreviations

- 1S,3R-ACPD

(1S,3R)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid

- AMPA

(S)-α-amino-4-bromo-3-hydroxy-5-isoxazolepropionic acid

- BHK

baby hamster kidney cells

- CBPG

(S)-(+)-2-(3′-carboxybicyclo[1.1.1]pentyl)-glycine

- CHPG

(RS)-2-chloro-5-hydroxyphenylglycine

- CPCCOEt

7-(hydroxyimino)cyclopropan[b]-chromen-1a-carboxylic acid ethylester

- DHPG

(S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine

- IP

inositol phosphate

- KA

kainate

- MPEP

2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- PI

phosphoinositide

References

- ABE T., SUGIHARA H., NAWA H., SHIGEMOTO R., MIZUNO N., NAKANISHI S. Molecular characterization of a novel metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 coupled to inositol phosphate/Ca2+ signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:13361–13368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALAGARSAMY S., MARINO M.J., ROUSE S.T., GEREAU R.W. , IV, HEINEMANN S.F., CONN P.J. Activation of NMDA receptors reverses desensitization of mGluR5 in native and recombinant systems. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:234–240. doi: 10.1038/6338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANIKSZTEIN L., OTANI S., BEN-ARI Y. Quisqualate metabotropic receptors modulate NMDA currents and facilitate the induction of long-term potentiation through protein kinase C. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1992;4:500–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLEAKMAN D., RUSIN K.I., CHARD P.S., GLAUM S.R., MILLER R.J. Metabotropic glutamate receptors potentiate ionotropic glutamate responses in the rat dorsal horn. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;42:192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOND A., LODGE D. Pharmacology of metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated enhancement of responses to excitatory and inhibitory amino acids on rat spinal neurons in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1015–1023. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURTON N.R., SMITH D.A.S., STONE T.W. A quantitative pharmacological analysis of some excitatory amino acid receptors in the mouse neocortex in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988. pp. 693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- CARLÀ V., MORONI F. General anaesthetics inhibit the responses induced by glutamate receptor agonists in the mouse cortex. Neurosci. Lett. 1992;146:21–24. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90162-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARLSSON A. The current status of the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1988;1:179–186. doi: 10.1016/0893-133x(88)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARLSSON A., HANSSON L.O., WATERS N., CARLSSON M.L. Neurotransmitter aberrations in schizophrenia:new perspectives and therapeutic implications. Cell. 1997;98:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASABONA G., KNOPFEL T., KUHN R., GASPARINI F., BAUMANN P., SORTINO M.A., COPANI A., NICOLETTI F. Expression and coupling to polyphosphoinositide hydrolysis of group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors in early post-natal and adult rat brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1997;9:12–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CERNE R., RANDIC M. Modulation of AMPA and NMDA responses in rat spinal dorsal horn neurons by trans-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid. Neurosci. Lett. 1992;144:180–184. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90745-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOI D.W. Excitotoxic cell death. J. Neurobiol. 1992;23:1261–1276. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINGRIDGE G.L., LESTER R.A.J. Excitatory amino acid receptors in the vertebrate central nervous system. Pharmacol. Rev. 1989;40:143–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DINGLEDINE R., BORGES K., BOWIE D., TRAYNELIS S.F. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOHERTY A.J., PALMER M.J., HENLEY J.M., COLLINGRIDGE G.L., JANE D.E. (RS)-2-Chloro-5-hydroxyphenylglycine (CHPG) activates mGlu5, but not mGlu1, receptors expressed in CHO cells and potentiates NMDA responses in the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:265–267. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GASPARINI F., LINGENHOEL K., STOER N., FLOR P.J., HEINRICH M., VRANESIC I., BIOLLAZ M., ALLGEIER H., HECKENDORN R., URWYLER S., VARNEY M.A., JOHNSON E.C., HESS S.D., RAO S.P., SACAAN A., SANTORI E.M., VELICELEBI G., KUHN R. 2-Methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP), a potent, selective and systemically active mGlu 5 receptor antagonist. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1493–1503. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRISON N.L., SIMMONDS M.A. Quantitative studies of some antagonists of NMDA in slices of rat cerebral cortex. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1985;84:381–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb12922.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARVEY J., COLLINGRIDGE G.L. Signal transduction pathways involved in the acute potentiation of NMDA responses by 1S,3R-ACPD in rat hippocampal slices. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;109:1085–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLMANN M., HEINEMANN S. Cloned glutamate receptors. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1993;17:31–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO I., KOHDA A., TANABE S., HIROSE E., HAYASHI M., MITSUNAGA S., SUGIYAMA H. 3,5-Dihydroxyphenylglycine: a potent agonist of metabotropic glutamate receptors. NeuroReport. 1992;3:1013–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAVITT D.C., ZUKIN S.R. Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatr. 1991;148:1301–1308. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON J.W., ASCHER P. Glycine potentiates the NMDA response in cultured mouse brain neurons. Nature. 1987;325:529–531. doi: 10.1038/325529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES M.W., HEADLEY P.M. Interactions between metabotropoipic and ionotropic glutamate receptor agonist in the rat spinal cord in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1025–1031. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00055-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KELSO S.R., NELSON T.E., LEONARD J.P. Protein kinase C-mediated enhancement of NMDA currents by metabotropic glutamate receptors in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 1992;449:705–718. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM J.K., HUGANIR R.L. Organization and regulation of proteins at synapses. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1999;11:248–254. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLECKNER N.W., DINGLEDINE R. Requirement for glycine in activation of NMDA-receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Science. 1988;241:835–837. doi: 10.1126/science.2841759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUTSUWADA T., KASHIWABUCHI N., MORI H., SAKIMURA K., KUSHIYA E., ARAKI K., MEGURO H., MASAKI H., KUMANISHI T., ARAKAWA M., MISHINA M. Molecular diversity of the NMDA receptor channel. Nature. 1992;358:36–41. doi: 10.1038/358036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOMBARDI G., ALESIANI M., LEONARDI P., CHERICI G., PELLICCIARI R., MORONI F. Pharmacological characterization of the metabotropic glutamate receptor inhibiting D-3H-aspartate output in rat striatum. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:1407–1412. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOMBARDI G., LEONARDI P., MORONI F. Metabotropic glutamate receptors, transmitter output and fatty acids: studies in brain slices. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:189–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15173.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LU Y.M., JIA Z., JANUS C., HENDERSON J.T., GERLAI R., WOJTOWICZ J.M., RODER J.C. Mice lacking metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 show impaired learning and reduced CA1 long term potentiation (LTP) but normal CA3 LTP. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:5193–5204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05196.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUJÀN R., NUSSER Z., ROBERTS J.D.B., SHIGEMOTO R., SOMOGYI P. Perisynaptic location of metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR1 and mGluR5 on dendrites and dendritic spines in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1996;8:1488–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANNAIONI G., ATTUCCI S., MISSANELLI A., PELLICCIARI R., CORRADETTI R., MORONI F. Biochemical and electrophysiological studies on (S)-(+)-2-(3′-carboxybicyclo[1.1.1]pentyl)-glycine (CBPG), a novel mGlu5 receptor agonist endowed with mGlu 1 receptor antagonist activity. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:917–926. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANNAIONI G., CARLÀ V., MORONI F. Pharmacological characterization of metabotropic glutamate receptors potentiating NMDA responses in mouse cortical wedge preparations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:1530–1536. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15570.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MELDRUM B., GARTHWAITE J. Excitatory amino acid neurotoxicity and neurodegenerative disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1990;11:379–387. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90184-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOHN A.R., GAINETDINOV R.R., CARON M., KOLLER B.H. Mice with reduced NMDA receptor expression display behaviors related to schizophrenia. Cell. 1999;98:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81972-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONYER H., SPRENGEL R., SCHOEPFER R., HERB A., HIGUCHI M., LOMELI H., BURNASHEV N., SAKMANN B., SEEBURG P. Heteromeric NMDA receptors: Molecular and functional distinction of subtypes. Science. 1992;256:1217–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKANISHI S. Molecular diversity of glutamate receptors and implications for brain function. Science. 1992;258:597–603. doi: 10.1126/science.1329206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKANISHI S. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: synaptic transmission, modulation and plasticity. Neuron. 1994;13:1031–1037. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOWAK L., BREGESTOVSKI P., ASCHER P., HERBERT A., PROCHIANTZ A. Magnesium gates glutamate-activated channels in mouse central neurones. Nature. 1984;307:462–465. doi: 10.1038/307462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'CONNOR J.J., ROWAN M.J., ANWYL R. Long-lasting enhancement of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation. Nature. 1994;367:557–559. doi: 10.1038/367557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLNEY J.W.Excitotoxins: an overview Excitotoxins 1983London: Macmillan; 82–96.ed. Fuxe, K., Roberts, P. & Schwarcz, R. pp [Google Scholar]

- OLNEY J.W. Excitotoxic amino acids and neuropsychiatric disorders. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1990;30:47–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.30.040190.000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PELLEGRINI-GIAMPIETRO D.E., CHERICI G., ALESIANI M., CARLÀ V., MORONI F. Excitatory amino acid release from rat hippocampal slices as a consequence of free radical formation. J. Neurochem. 1988;51:1960–1963. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PELLICCIARI R., RAIMONDO M., MARINOZZI M., NATALINI B., COSTANTINO G., THOMSEN C. (S)-(+)-2-(3-Carboxybicyclo[1.1.1]pentil)-glycine, a structurally new group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:2874–2876. doi: 10.1021/jm960254o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIN J.-P., DUVOISIN R. The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and functions. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PISANI A., CALABRESI P., CENTONZE D., BERNARDI G. Enhancement of NMDA responses by group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in striatal neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:1007–1014. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIZZI M., BORONI F., MORAITIS K., BIANCHETTI A., MEMO M., SPANO P.F. Reversal of glutamate excitotoxicity by activation of PKC-associated metabotropic glutamate receptors in cerebellar granule cells relies on NR2C subunit expression. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:2489–2496. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHOEPP D.D., CONN P.J. Metabotropic glutamate receptors in brain function and pathology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1993;14:13–20. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90107-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHOEPP D.D., GOLDSWORTHY J., JOHNSON B.G., SALHOFF C.R., BAKER S.R. 3,5-Dihydroxyphenilglycine is a highly selective agonist for phosphoinositide-linked metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat hippocampus. J. Neurochem. 1994;63:769–772. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIGEMOTO R., NOMURA S., OHISHI H., SUGIHARA H., NAKANISHI S., MIZUNO N. Immunohistochemical localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR5, in the rat brain. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;163:53–57. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90227-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMSEN C., KRISTENSEN P., MULVIHILL E., HALDEMAN B., SUZDAK P.D. L-2-Amino-4-phosphonobutyrate (L-AP4) is an agonist at the type- IV metabotropic glutamate receptor which is negatively coupled to adenylate cyclase. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;227:361–362. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(92)90018-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMSEN C., MULVIHILL E.R., HALDEMAN B.A., PICKERING D.S., HAMPSON D.R., SUZDAK P.D. A pharmacological characterization of the mGluR1a subtype of the metabotropic glutamate receptor expressed in baby hamster kidney cell line. Brain Res. 1993;619:22–28. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91592-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UGOLINI A., CORSI M., BORDI F. Potentiation of NMDA and AMPA responses by group 1 mGluR in spinal cord motoneurons. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1047–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UGOLINI A., CORSI M., BORDI F. Potentiation of NMDA and AMPA responses by the specific mGluR5 agonist CHPG in spinal cord motoneurons. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1569–1576. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIESENFELD-HALLIN Z. Combined opioid-NMDA antagonist therapies. What advantages do they offer for the control of pain syndromes. Drugs. 1998;55:1–4. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199855010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]