Abstract

The aim of the present study was to examine the effects of chronic infusion of the long-acting agonist salmeterol on pulmonary β2-adrenoceptor function in Sprague-Dawley rats in vivo and to elucidate the molecular basis of any altered state.

Systemic administration of rats with salmeterol for 7 days compromised the ability of salmeterol and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), given acutely by the intravenous route, to protect against ACh-induced bronchoconstriction when compared to rats treated identically with vehicle.

β1- and β2-adrenoceptor density was significantly reduced in lung membranes harvested from salmeterol-treated animals, which was associated with impaired salmeterol- and PGE2-induced cyclic AMP accumulation ex vivo.

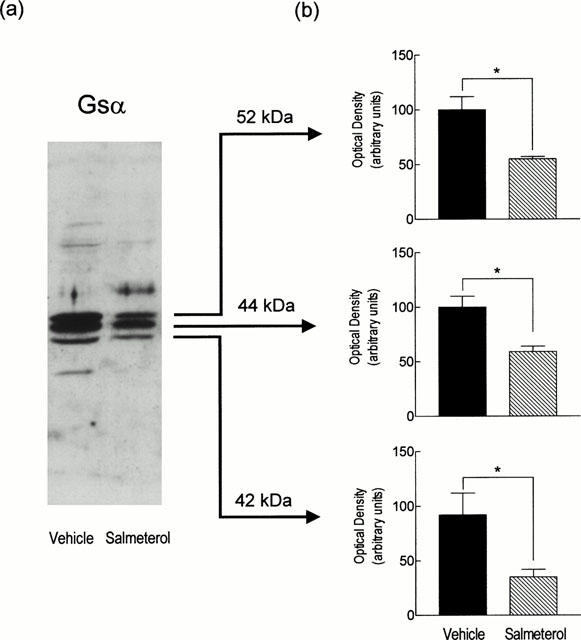

Three variants of Gsα that migrated as 42, 44 and 52 kDa peptides on SDS polyacrylamide gels were detected in lung membranes prepared from both groups of rats but the intensity of each isoform was markedly reduced in rats that received salmeterol.

The activity of cytosolic, but not membrane-associated, G-protein receptor-coupled kinase was elevated in the lung of salmeterol-treated rats when compared to vehicle-treated animals.

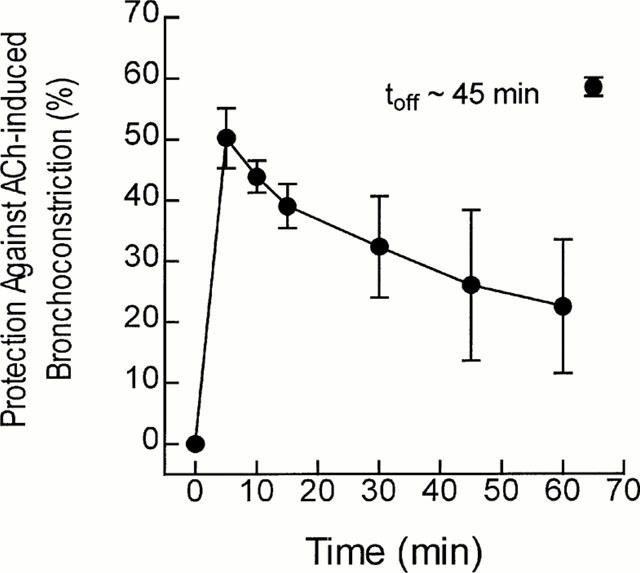

The ability of salmeterol, administered systemically, to protect the airways of untreated rats against ACh-induced bronchoconstriction was short-acting (toff ∼45 min), which contrasts with its long-acting nature when given to asthmatic subjects by inhalation.

These results indicate that chronic treatment of rats with salmeterol results in heterologous desensitization of pulmonary Gs-coupled receptors. In light of previous data obtained in rats treated chronically with salbutamol, we propose that a primary mechanism responsible for this effect is a reduction in membrane-associated Gsα. The short-acting nature of salmeterol, when administered systemically, and the reduction in β-adrenoceptor number may be due to metabolism to a biologically-active, short-acting and non-selective β-adrenoceptor agonist.

Keywords: β2-adrenoceptor desensitization in vivo, salmeterol, down-regulation of Gsα

Introduction

Repeated administration of high-dose β2-adrenoceptor agonists renders susceptible individuals tolerant to their beneficial effects in asthma. With regard to long-acting agonists, there is evidence that tolerance develops both to their dilator and protective effects in the airways. Lipworth and colleagues (Newnham et al., 1994; 1995) have reported that 4 weeks treatment of asthmatic subjects with inhaled eformoterol and salmeterol produced a rightwards shift in the bronchodilator dose-response curve for both agonists. This state of tolerance was reflected in terms of a decrease in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced expiratory flow at 25% and 75% of vital capacity (FEF25 – 75), indicating that subsensitivity of β2-adrenoceptors to salmeterol and eformoterol had occurred in the large and small airways. Equally, tolerance to the protective effect of salmeterol against methacholine- and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction has been documented in mild to moderate asthmatic subjects after chronic administration (Boulet et al., 1998; Cheung et al., 1992; Drotar et al., 1998; Simons et al., 1997).

The molecular aetiology of β2-adrenoceptor sub-sensitivity in asthma is unclear. Airways resected from asthmatic patients fail to relax normally to isoprenaline, supporting a possible defect in β-adrenoceptor function (Bai et al., 1992; Cerrina et al., 1986; Goldie et al., 1986), although it is equivocal whether this is the result of treatment or a consequence of the disease process itself. Nevertheless, down-regulation of β-adrenoceptor number in lung and airways smooth muscle has been reported in animals given isoprenaline and noradrenaline chronically by infusion (Nerme et al., 1990; Nishikawa et al., 1993; 1994) and this is associated with a reduced functional responsiveness towards β-adrenoceptor agonists ex vivo (Nerme et al., 1990; Nishikawa et al., 1994). Thus, it is possible that compromised bronchodilatation and loss of protection against various bronchoconstrictor challenges in humans is due, at least in part, to pulmonary β2-adrenoceptor desensitization.

Two major molecular mechanisms have been delineated in isolated cells that result in short-term β2-adrenoceptor desensitization. One of these promotes homologous refractoriness and involves the uncoupling of the agonist-occupied form of the receptor from the stimulatory guanine nucleotide binding protein, Gs, by mechanisms that require phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues at the carboxy-terminus of the agonist-occupied receptor (Fredericks et al., 1996; Premont et al., 1995). This reaction can be catalysed by at least three members of the G-protein receptor-coupled kinase (GRK) superfamily family, including GRK2 and GRK3 (Krupnick & Benovic, 1998; Premont et al., 1995). The subsequent binding of β-arrestin, a soluble protein that prevents further coupling to Gs (Lohse et al., 1990), then halts signalling through the receptor. Short-term desensitization is also effected by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) following phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues present within the third intracellular loop of the protein in response to an increase in intracellular cyclic AMP (Lohse et al., 1990). In contrast, prolonged periods of desensitization can involve physical internalization and subsequent degradation of receptors (Lohse, 1993) due to an inhibition of transcription and/or increased post-transcriptional processing of β2-adrenoceptor mRNA (Lohse, 1993; Mayor et al., 1998). In addition, another less-well characterized process is a reduction of membrane-associated Gsα (Milligan, 1993), although the functional relevance of this process has not been rigorously explored in vitro or in vivo.

Although desensitization of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) has been studied extensively, most of the information to date has been gathered from cultured cell systems and the extent to which this applies to the in vivo situation is little investigated. Here we describe pulmonary β2-adrenoceptor desensitization in rats treated chronically with the long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonist, salmeterol and have investigated the molecular aetiology of this altered state. Although little is known of the regulation of the β2-adrenoceptor in the rat, it was selected for two reasons. First, the rat is relatively more steroid-sensitive than other small laboratory animals such as the guinea-pig (Hirshman & Downes, 1985). Second, we have shown previously that glucocorticoids, such as dexamethasone, protect against pulmonary β2-adrenoceptor desensitization in the rat in vivo (Mak et al., 1995), which mimics the effect of steroids in humans (Barnes, 1995).

Methods

Animals and surgery

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Ltd, Kent) of 275 – 300 g body weight were housed in a temperature-controlled (21°C) environment with food and water available ad libitum. Animals were sedated with 2% v v−1 Hypnorm (0.3 ml kg−1) and implanted sub-cutaneously with osmotic mini pumps (Alzet model 2001) delivering salmeterol (10 μg kg−1 h−1) or vehicle (0.1% glacial acetic acid in phosphate-buffered saline) for 7 days as described previously (Finney et al., 2000). The dose of salmeterol is approximately 25% of the dose of salbutamol used in patients hospitalized with acute severe asthma (Bohn et al., 1984; Cheong et al., 1988; Cluzel et al., 1990; O'Driscoll et al., 1988) and is based on equivalence studies in human asthmatic subjects, where a weight-for-weight dose ratio for salmeterol:salbutamol of 1 : 4 was found (Higham et al., 1997). Salmeterol was given as an infusion to allow a comparison with a previous study where desensitization of pulmonary β2-adrenoceptors was induced in rats treated systemically with salbutamol (Finney et al., 2000).

Instrumentation of rats for measurement of airway mechanics

Each rat was anaesthetized with urethane and the left carotid artery and left jugular vein were cannulated for measuring changes in blood pressure and for the injection of drugs respectively. The trachea was cannulated and the animal ventilated at constant volume with a pump operating at 75 strokes per minute. Changes in respiratory insufflation pressure were measured using a modification of the method described by Konzett & Rössler (1940) as described in Finney et al. (2000).

Assessment of pulmonary β2-adrenoceptor desensitization in vivo

Vehicle- and salmeterol-treated rats were given ACh (500 μg kg−1 i.v, bolus) every 5 min to establish a constant degree of bronchoconstriction. When airway function had normalized (15 min after last dose of ACh), a submaximal concentration of salmeterol (100 μg kg−1 i.v. bolus) was administered and the magnitude of ACh-induced bronchoconstriction was reassessed 5 min later. An identical protocol was used to assess the potential bronchoprotective effect of PGE2 (300 μg kg−1 i.v. bolus).

Quantification of β-adrenoceptor number in lung membranes

Lung membranes were prepared according to Mak et al. (1995) and Nishikawa et al. (1993), and total, β1- and β2-adrenoceptor density (Bmax) and the affinity (KD) of [125I]-iodocyanopindolol ([125I]-ICYP) was determined as described previously (Finney et al., 2000).

Measurement of steady-state β1- and β2-adrenoceptor mRNA levels

Total RNA was isolated from lung as described by Chomczynski & Sacchi (1987) and the abundance of β1- and β2-adrenoceptor mRNA transcripts estimated by Northern blot analysis. Samples of denatured mRNA (20 μg lane−1) were size fractionated on 1% agarose/formaldehyde gels containing 20 mM MOPS (pH 7), 5 mM sodium acetate and 1 mM EDTA, and transferred to Hybond-N+ membranes (Amersham) by capillary action using 20× standard sodium citrate (SSC; 1× SCC, 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM sodium citrate, pH 7). The RNA was permanently fixed to the membranes using a UV Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene, Cambridge).

Random primer labelling was carried out with the 851 bp SmaI/PvuII and 439 bp I fragments from the human β1- and β2-adrenoceptor cDNAs respectively using [α-32P]-dCTP. A 1272 bp PstI fragment from the rat glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA was used as a ‘house-keeping' gene. Pre-hybridization and hybridization were carried out at 42°C with the probes labelled to approximately 1.5×106 c.p.m. ml−1 in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50% formamide, 2× SSC, 5× Denhardt's solution, 0.1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, 250 μg ml−1 denatured salmon sperm DNA). After hybridization, the blots were washed to a stringency of 0.1× SCC/0.1% SDS at 65°C and exposed to Kodak X-OMAT film at −80°C for 1 to 4 days. The autoradiograms were quantified by laser-scanning densitometry and expressed as a ratio to GAPDH.

Ex vivo cyclic AMP accumulation studies

Lung was chopped (∼5 mm3) and equilibrated for 30 min at 37°C in oxygenating (95% O2/5% CO2) Krebs-Henseleit (KS) solution (in mM: 118 NaCl, 5.9 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4.7H2O, 1.2 NaH2PO4.2H2O, 2.5 CaCl2.6H2O, 10 glucose, 25 NaHCO3) containing 10 μM indomethacin. Tissue was incubated for 30 min in the presence of IBMX (100 μM), and salmeterol (1 μM) or PGE2 (1 μM) was added for 5 min. Tissue was removed from the KH solution, blotted on absorbent paper, immersed in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C. When required the cyclic AMP content was extracted from the lung and measured by radioimmunoassay as described previously (Finney et al., 2000; Seybold et al., 1998).

Measurement of GRK activity

Cytosolic and particulate GRK was prepared from rat lung according to Benovic et al. (1987) and GRK activity was determined immediately by the method of Mayor et al. (1987).

Western immunoblot analyses

Frozen lung was homogenized, denatured and subjected to electrophoresis on 10% SDS/Tris polyacrylamide gels as described previously (Finney et al., 2000). Proteins were transferred onto Hybond nitrocellulose paper and blocked overnight in 10 mM Tris-base/0.05% Tween 20 containing 5% skimmed milk. Membranes were then incubated at 25°C for 1 h with a rabbit polyclonal antibody specific to either Gsα, Gβ or the β2-adrenoceptor diluted 1 : 1000, 1 : 1000 and 1 : 750 respectively. Membranes were washed, incubated with a donkey, anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody and treated with ECL reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Proteins were visualized by exposure of the membranes to Kodak X-OMAT film and quantified by laser-scanning densitometry.

Protein estimation

Protein was measured using a BioRad kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Drugs and analytical reagents

Salmeterol was provided by GlaxoWellcome (Stevenage, Hertfordshire, U.K.). ECL reagent, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and [α32P]-dCTP and [125I]-ICYP (specific activities >3000 Ci mmol−1 and 2000 Ci mmol−1 respectively) were supplied by Amersham International (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, U.K.). Antibodies against Gsα and Gβ were purchased from NEN/Dupont (code NEI 805 and NEI 808 respectively) and the β2-adrenoceptor antibody was from Santa Cruz (sc # 569). All other reagents were from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, U.K.).

Statistical analysis

Data points and bars represent the mean±s.e.mean of ‘n' independent observations. When appropriate, data were analysed non-parametrically using Mann – Whitney U-test. The null hypothesis was rejected when P<0.05.

Results

Repeated administration of ACh (500 μg kg−1 i.v. ∼ED50) to saline- and salmeterol-treated rats provoked bronchoconstriction that was highly reproducible over 60 min (data not shown). The resting mean arterial blood pressure was not significantly different (P>0.05) between vehicle (76.1±3.7 mmHg, n=28)- and salmeterol (77.9±8.2 mmHg, n=31)-treated animals. Similarly, intravenous administration of ACh (500 μg kg−1) evoked a depressor response in both groups of rats of equivalent magnitude (vehicle: 34.4±1.5 mmHg, n=28; salmeterol: 29.1±3.1 mmHg, n=28, P>0.05).

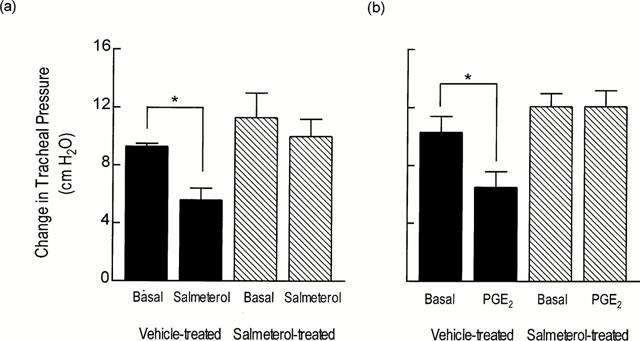

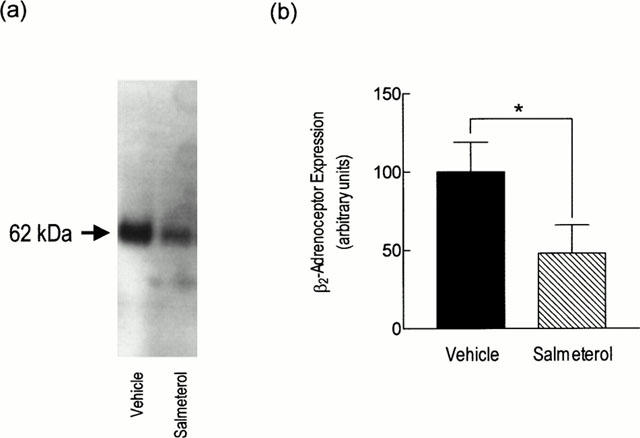

Effect of chronic treatment of rats with salmeterol on the ability of salmeterol and PGE2 to protect against ACh-induced bronchoconstriction

Intravenous administration of salmeterol (100 μg kg−1 bolus) or PGE2 (300 μg kg−1 bolus) to vehicle-treated rats significantly reduced (by 44 and 32% respectively) the magnitude of ACh-induced bronchoconstriction whereas in the salmeterol-treated group of animals no significant protection was observed with either agonist indicating that the desensitization was heterologous (Figure 1a,b; Table 1). In none of the experiments did salmeterol or PGE2 affect resting airways tone.

Figure 1.

Effect of chronic systemic treatment of rats with salmeterol on the ability of salmeterol and PGE2, administered acutely, to protect against ACh-induced bronchoconstriction. Rats were treated with vehicle or salmeterol (10 μg kg−1 h−1). After 7 days, each animal was instrumented for the measurement of lung function. ACh (500 μg kg−1 i.v.) was administered and the maximum increase in overflow pressure was measured. When baseline lung function was re-established, salmeterol (100 μg kg−1 i.v. bolus) or PGE2 (300 μg kg−1 i.v. bolus) was given and 5 min later ACh was administered again and any change in overflow pressure was noted. Each bar represents the mean±s.e.mean of four determinations made in different rats. *P<0.05, significant protection of ACh-induced bronchoconstriction.

Table 1.

Effect of chronic systemic treatment of rats with salmeterol on the ability of salmeterol and PGE2, given acutely, to protect against ACh-induced bronchoconstriction

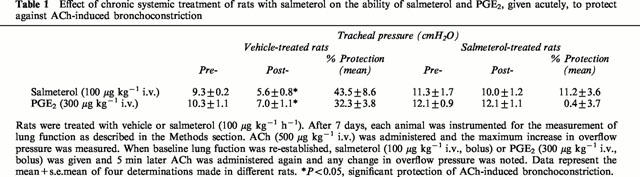

Effect of chronic treatment of rats with salmeterol on β1- and β2-adrenoceptor density and mRNA expression in lung

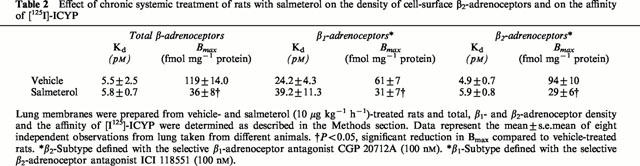

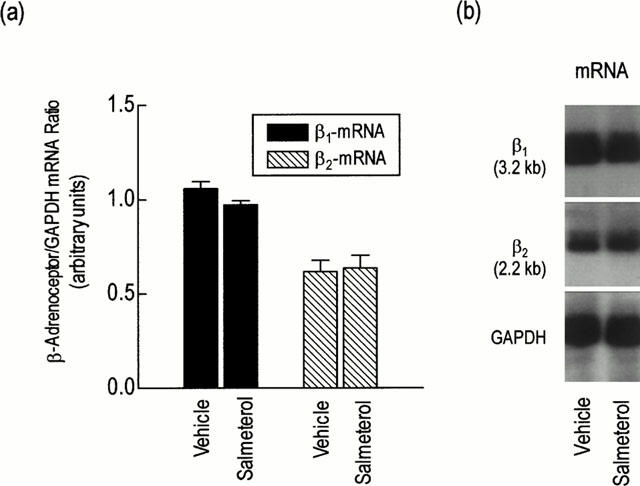

Chronic treatment of rats with salmeterol (10 μg kg−1 h−1) produced a significant (∼70%) reduction in β-adrenoceptor density when compared to naïve animals, without affecting the affinity of the non-selective ligand, [125I]-ICYP (Table 2). In the presence of selective antagonists it was established that salmeterol reduced β1- and β2-adrenoceptor number by 50 and 70% respectively but did not alter the KD of [125I]-ICYP for either receptor subtype (Table 2). To determine whether the in vivo binding of salmeterol to an ‘exosite' within the β2-adrenoceptor reduced, artificially, the total number of binding sites available to [125I]-ICYP ex vivo, β2-adrenoceptor protein in the lung from both groups of animals was measured by Western blotting. Consistent with the radioligand binding data, chronic treatment of rats with salmeterol reduced β2-adrenoceptor protein in lung membranes by ∼50% (Figure 2). Despite the reduction in receptor expression at day 7, the steady state level of β1- and β2-adrenoceptor mRNA transcripts was unchanged in lung harvested from salmeterol-treated rats when compared to animals that received vehicle (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Effect of chronic systemic treatment of rats with salmeterol on the density of cell-surface β2-adrenoceptors and on the affinity of [125I]-ICYP

Figure 2.

Effect of chronic systemic treatment of rats with salmeterol on β2-adrenoceptor protein expression in lung membranes. Rats were treated with salmeterol (10 μg kg−1 h−1) or vehicle for 7 days and the expression of β2-adrenoceptor protein was measured. (a,b) show a representative Western blot and bar chart of the mean±s.e.mean of six determinations respectively. Equal loading was confirmed by staining of the gels with Coomassie Blue (not shown). *P<0.05, significant reduction in β2-adrenoceptor protein in salmeterol-treated rats when compared to vehicle-treated animals.

Figure 3.

Effect of chronic systemic treatment of rats with salmeterol on the steady-state level of β1- and β2-adrenoceptor mRNA transcripts. Rats were treated with salmeterol (10 μg kg−1 h−1) or vehicle for 7 days. Lungs were excised and β1- and β2-adrenoceptor mRNA was extracted and estimated by Northern analysis. (a) shows the mean±s.e.mean of six independent determinations that are expressed relative to the ‘house-keeping' gene GAPDH. A representative autoradiogram is shown in (b).

Effect of chronic treatment of rats with salmeterol on the ability of salmeterol and PGE2 to increase cyclic AMP mass in lung ex vivo

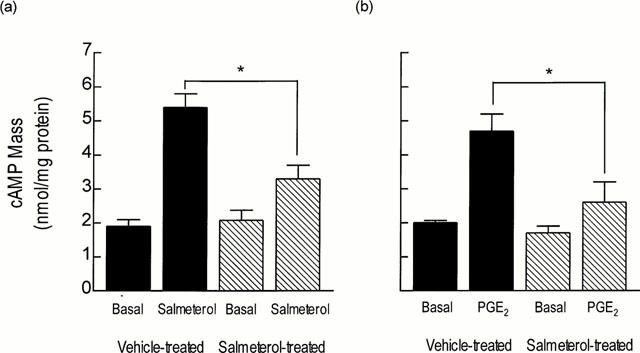

To determine if down-regulation of β-adrenoceptor number was accompanied by compromised signal transduction, the ability of salmeterol to increase cyclic AMP mass in lung parenchyma was assessed ex vivo. No significant difference in the basal cyclic AMP content was detected between lung excised from either group of animals (Figure 4). However, salmeterol (1 μM)-induced cyclic AMP accumulation was significantly attenuated in lung taken from salmeterol-treated rats (1.56 fold increase over basal level) when compared to animals that received vehicle (2.74 fold increase over basal level; Figure 4a). The desensitization of β-adrenoceptor-mediated cyclic AMP accumulation by salmeterol was heterologous in that the ability of PGE2 to increase the cyclic AMP content in lung was profoundly impaired (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Effect of chronic systemic treatment of rats with salmeterol on salmeterol- and PGE2-induced cyclic AMP accumulation in lung ex vivo. Rats were treated with salmeterol (10 μg kg−1 h−1; filled bars) or vehicle (hatched bars) for 7 days and the ability of salmeterol (a) and PGE2 (b) to increase cyclic AMP mass in lung was determined ex vivo in the presence of IBMX (100 μM). Each bar represents the mean±s.e.mean of six independent determinations using tissue from different animals. *P<0.05, significant reduction in salmeterol- and PGE2-induced cyclic AMP formation.

Effect of chronic treatment of rats with salmeterol on the expression of Gsα and Gβ subunits in lung

Western blotting was performed to determine if the compromised ability of salmeterol to elevate the cyclic AMP content in lung taken from salmeterol-treated rats was associated with a reduction in the expression of Gsα (Figure 5). A primary antibody raised against an epitope at the carboxy-terminus of the α-subunit of Gs, identified three bands in lung membranes prepared from vehicle-treated rats that migrated as 42, 44 and 52 kDa peptides on SDS polyacrylamide gels. Treatment of rats for 7 days with salmeterol significantly reduced the intensity of each of these bands by between 45 and 70% (Figure 5a,b). A primary antibody raised against an epitope at the carboxy-terminus of the common β-subunit of heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins, detected a single 35 kDa band in lung membranes prepared from vehicle-treated rats. However, unlike Gsα variants, Gβ was not altered in lung taken from salmeterol-treated animals (data not shown). Western blotting failed to detect Gsα or Gβ subunits in the cytosolic fraction of lung tissue taken from either group of animals at day 7.

Figure 5.

Effect of chronic systemic treatment of rats with salmeterol on Gsα expression in lung membranes. Rats were treated with salmeterol (10 μg kg−1 h−1) or vehicle for 7 days and the expression of membrane-associated Gsα variants was measured by Western blotting. (a,b) show representative blot and a bar charts of the mean data (±s.e.mean of six determinations) respectively. Equal loading was confirmed by staining of the gels with Coomassie Blue (not shown). *P<0.05, significant reduction in Gsα variant expression.

Effect of chronic treatment of rats with salmeterol on GRK activity in lung

Chronic administration of rats with salmeterol produced a significant (∼2 fold over basal level) increase in cytosolic GRK activity in lung parenchyma when compared to vehicle-treated animals (from 164±25 to 341±87 fmol min−1 mg protein−1; n=12, P<0.05). No change in GRK activity was detected in the particulate fraction of salmeterol-treated rats at day 7.

Duration of action of intravenous salmeterol

The duration of action of salmeterol was assessed by monitoring the magnitude of ACh (500 μg kg−1 i.v.)-induced bronchoconstriction repeatedly in naïve rats over a period of 60 min. The anti-spasmogenic activity of salmeterol (100 μg kg−1; bolus) was short-lasting with an offset halftime (defined as the time required for the peak of ACh-bronchoconstriction to recover by 50%) of ∼45 min (Figure 6). Protection against ACh-induced bronchoconstriction was re-established when salmeterol was re-administered 65 min after the first dose, indicating that the short duration of action was not due to β2-adrenoceptor desensitization.

Figure 6.

Duration of action of intravenous salmeterol in rats. Naïve rats were given ACh (500 μg kg−1, i.v.) and changes in overflow pressure were measured. When basal lung function was re-established salmeterol (100 μg kg−1 i.v.; bolus) was given and 5, 10, 15, 30, 45 and 60 min later the magnitude of ACh-induced bronchoconstriction was measured. At 65 min salmeterol (100 μg kg−1 i.v.; bolus) was given again and the protection against the original bronchoconstrictor response was measured. Data points represent the mean±s.e.mean of six independent determinations.

Discussion

Systemic infusion of salmeterol to rats for 7 days promoted pulmonary β2-adrenoceptor desensitization that was seen both at the functional and molecular level. This finding is consistent with a number of previous studies where desensitization of β2-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation has been demonstrated ex vivo in tracheae and lung taken from rats treated chronically with isoprenaline and noradrenaline (Avner & Noland, 1978; Nishikawa et al., 1994), and in vivo in rats given salbutamol (Finney et al., 2000). Significantly, the anti-spasmogenic activity of PGE2, which relaxes rat tracheae through EP4-like prostanoid receptors (Lydford & McKechnie, 1994), was also impaired indicating that the desensitization was heterologous. Although this mode of desensitization is poorly documented in vivo, it has been observed in the lung and heart of rats given salbutamol (Finney et al., 2000) and isoprenaline (Zeiders et al., 1997) respectively.

Many processes can effect desensitization of β2-adrenoceptors and, as the molecular aetiology of long-term subsensitivity in vivo is largely unexplored, several mechanisms were investigated.

Down-regulation of β2-adrenoceptor number

Systemic treatment of rats with salmeterol produced a marked (70%) reduction in pulmonary β2-adrenoceptor density relative to animals that received vehicle. These results agree with a previous study where rats were treated chronically with salbutamol (Finney et al., 2000), but the degree of receptor down-regulation effected by salmeterol was much greater. The reason for this disparity is currently unclear. One explanation is that the decrease in Bmax may have been over-estimated due to pseudo-irreversible in vivo binding of salmeterol to the ‘exosite' within the β2-adrenoceptor, which would reduce the total number of binding sites available to [125I]-ICYP ex vivo. However, this possibility seems unlikely as a comparable (52%) reduction in β2-adrenoceptor protein was found in lung membranes by Western analysis.

The results of the present and a previous study (Finney et al., 2000) are consistent with the concept that chronic exposure of animals to β2-adrenoceptor agonists effects tolerance by stimulating the internalization and degradation of the cognate receptors (Lohse, 1993). Although destabilization of β2-adrenoceptor mRNA can account for this effect, there was no evidence for a reduction in mRNA transcripts in the lung of salmeterol-treated rats at day 7. This was unexpected and contrary to previous in vivo experiments performed in rats and guinea-pigs given isoprenaline (Mak et al., 1995; Nishikawa et al., 1993) and noradrenaline (Nishikawa et al., 1994) respectively. At least three explanations could account for this discrepancy. First, the efficacy and selectivity of salmeterol, noradrenaline and isoprenaline differ between β-adrenoceptor subtypes, which may influence the magnitude and kinetics of mRNA degradation. Second, β-adrenoceptor expression and function vary between strains of rat (Van Liefde et al., 1994). Thus, mRNA in the lung of Sprague-Dawley rats treated with salmeterol (this study) may be degraded relatively rapidly and recover to steady-state levels by day 7 when compared to Wistar rats treated identically with isoprenaline (Mak et al., 1995; Nishikawa et al., 1993). Third, salmeterol may down-regulate pulmonary β2-adrenoceptors in Sprague-Dawley rats by a process unrelated to mRNA destabilization.

While tolerance to salmeterol could be due to the reduction in pulmonary β2-adrenoceptor density, other processes must be involved, as PGE2-induced responses were also impaired. Indeed, the desensitization of salmeterol-induced cyclic AMP accumulation in lung ex vivo was very similar in magnitude to that produced in the lung of salbutamol-treated rats (Finney et al., 2000), which would not be expected if β2-adrenoceptor down-regulation was the only determinant of tolerance. In addition, heterologous desensitization may have resulted, at least in part, from down-regulation/uncoupling of the EP4-like receptor. Although the mechanism by which this could occur is unclear, PKA is an unlikely effector as activation of this enzyme by salbutamol was significantly impaired in lung taken from salbutamol-treated rats (Finney et al., 2000).

Activation of GRKs

Phosphorylation of GPCRs by GRKs can promote desensitization. However, GRK activity was not elevated in lung membranes prepared from salmeterol- (this study) or salbutamol-treated rats (Finney et al., 2000), which is consistent with GRK-induced receptor phosphorylation being a short-term process. Moreover, as GRKs effect homologous desensitization it is difficult to envisage how this process could also inhibit PGE2-induced responses. In contrast, cytosolic GRK activity was significantly increased in the lung of salmeterol-treated rats, in agreement with a previous study where salbutamol was used (Finney et al., 2000), which may be due to increased GRK2 gene transcription and/or mRNA stability (Iaccarino et al., 1998).

Down-regulation of Gsα

Heterologous desensitization GPCRs can be accounted for by a reduction in the abundance of membrane-associated Gsα (Milligan, 1993). Indeed, three molecular weight species of Gsα were detected in rat lung membranes as reported previously (Finney et al., 2000) but the expression was significantly reduced in tissue taken from those animals that received salmeterol. Further support for this mechanism derives from a previous study where chronic treatment of rats with salbutamol reduced the ability of cholera toxin to increase the cyclic AMP content in lung ex vivo (Finney et al., 2000). Moreover, the bronchoprotective effect of forskolin and the phosphodiesterase inhibitor, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, was preserved in rats treated chronically with salbutamol providing further evidence that the site of desensitization is upstream of adenylyl cyclase (Finney et al., 2000). Mechanistically, down-regulation of Gsα would blunt the ability of salmeterol, and other agonists (e.g. PGE2) that utilize the same pool of Gsα, to activate adenylyl cyclase and protect the airways against ACh-induced bronchoconstriction. A similar explanation is suggested for the impaired activation of adenylyl cyclase by isoprenaline and glucagon ex vivo in cardiac membranes purified from rats treated chronically with isoprenaline (Zeiders et al., 1997).

Down-regulation of Gsα could be effected by at least three mechanisms (discussed in Finney et al., 2000) including decreased Gsα gene transcription, destabilization of Gsα mRNA transcripts or redistribution/degradation of membrane-associated Gsα. In cell-based experiments there is strong evidence that β-adrenoceptor agonists promote the translocation of Gsα from the membrane to a cytosolic pool (Ransnas et al., 1989; Wedegaertner et al., 1996) by a process that involves depalmitoylation of the protein (Wedegaertner & Bourne, 1994; Loisel et al., 1999). This is followed, after chronic exposure, by degradation of Gsα (Milligan, 1993). The results presented herein are consistent with the degradation theory as the reduction in membrane-associated Gsα was not associated with a commensurate increase of Gsα in the cytosol at day 7.

A critical question that arises from the present study is whether a 45 to 70% reduction in Gsα is sufficient to effect tolerance to salmeterol. As discussed previously (Finney et al., 2000) evidence provided by Paulssen et al. (1992) suggests that changes in Gsα expression can, indeed, affect signalling through GPCRs in an agonist-dependent manner.

Duration of action of intravenous salmeterol

An unexpected observation of the present investigation was the short-acting behaviour of salmeterol when given to rats by the intravenous route that was not the result of acute β2-adrenoceptor desensitization. If the duration of action of salmeterol is to be explained by binding to an exosite (Green et al., 1996; Rong et al., 1999) then this should be independent of the route of administration. Thus, other mechanisms must account for this difference. One possibility is that salmeterol was rapidly metabolized to a shorter-acting molecule that retained affinity and efficacy at the β2-adrenoceptor. This situation would be in contrast to administration by inhalation where salmeterol's high lipophilicity would ensure that it is rapidly absorbed and retained in the airways; indeed, bronchoprotection effected by inhaled salmeterol in asthmatic subjects persists for more than 12 h (Rabe et al., 1993). Previous studies in rats have established that salmeterol is cleared predominantly by metabolism and at least two, albeit minor, products can be formed by O-dealkylation of the phenalkyloxalkyl ‘tail' that, theoretically could be short-acting (Manchee et al., 1993). In our own preliminary studies we have found that following bolus intravenous administration of salmeterol to Sprague-Dawley rats, the circulating level fell rapidly due to the combined effects of a very high volume of distribution (previously estimated at 42 ml min−1 kg−1) and metabolism with products resulting from O-dealkylation detected (Authors' unpublished observations). Metabolism of salmeterol could also account for the unanticipated reduction in pulmonary β1-adrenoceptor density after chronic treatment if these O-dealkylated metabolites are agonists at both β1- and β2-adrenoceptor subtypes. Alternatively, the down-regulation of β1-adrenoceptors might simply reflect the weak agonist activity of salmeterol at this subtype (Ball et al., 1991; Roux et al., 1996).

Conclusion

Chronic systemic treatment of rats with salmeterol produced pulmonary β2-adrenoceptor desensitization. Although several processes could contribute to this effect, the heterologous nature of the desensitization and the results of a previous investigation with salbutamol (Finney et al., 2000) where the bronchoprotective effect of forskolin and IBMX were preserved, suggest that a primary molecular aetiology is a reduction in the abundance of membrane-associated Gsα. As salmeterol is a partial agonist on many tissues the marked reduction in β2-adrenoceptor density may also have contributed to desensitization. It is important to appreciate that these experiments were performed with healthy rats and the relevance of the findings to patients with asthma is unknown. However, evidence that asthma, itself, does not predispose to β2-adrenoceptor desensitization has been presented (Penn et al., 1996). Thus, down-regulation of Gsα may be pertinent to the treatment of asthma where susceptible individuals become tolerant to the beneficial effects of salmeterol or high doses of short-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonists such as salbutamol.

Note added in proof

Since submission of this manuscript the short duration of action of salmeterol at pulmonary β2-adrenoceptors has been confirmed in the guinea-pig when given by the intravenous route.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge GlaxoWellcome, Monsanto/Searle and the Royal Brompton Hospital Clinical Research Committee for financial support.

Abbreviations

- FEF25 – 75

forced expiratory flow at 25% and 75% of vital capacity

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GRK

G-protein receptor-coupled kinase

- ICYP

iodocyanopindolol

- KH

Krebs-Henseleit

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PKA

cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase

- ROS

rod outer segments

- SSC

standard sodium citrate

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

References

- AVNER B.P., NOLAND B. In vivo desensitization to β-receptor-mediated bronchodilator drugs in the rat: decreased beta receptor affinity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1978;207:23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAI T.R., MAK J.C., BARNES P.J. A comparison of β-adrenergic receptors and in vitro relaxant responses to isoproterenol in asthmatic airway smooth muscle. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1992;6:647–651. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BALL D.I., BRITTAIN R.T., COLEMAN R.A., DENYER L.H., JACK D., JOHNSON M., LUNTS L.H., NIALS A.T., SHELDRICK K.E., SKIDMORE I.F. Salmeterol, a novel, long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonist: characterization of pharmacological activity in vitro and in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;104:665–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J. β-Adrenergic receptors and their regulation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995;152:838–860. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENOVIC J.L., MAYOR F., STANISZEWSKI C., LEFKOWITZ R.J., CARON M.G. Purification and characterization of the β-adrenergic receptor kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:9026–9032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOHN D., KALLOGHLIAN A., JENKINS J., EDMONDS J., BARKER G. Intravenous salbutamol in the treatment of status asthmaticus in children. Crit. Care Med. 1984;12:892–896. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198410000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOULET L.P., CARTIER A., MILOT J., COTE J., MALO J.L., LAVIOLETTE M. Tolerance to the protective effects of salmeterol on methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction: influence of inhaled corticosteroids. Eur. Respir. J. 1998;11:1091–1097. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.11051091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CERRINA J., LE ROY LADURIE M., LABAT C., RAFFESTIN B., BAYOL A., BRINK C. Comparison of human bronchial muscle responses to histamine in vivo with histamine and isoproterenol agonists in vitro. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1986;134:57–61. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEONG B., REYNOLDS S.R., RAJAN G., WARD M.J. Intravenous β-agonist in severe acute asthma. Br. Med. J. 1988;297:448–450. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6646.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEUNG D., TIMMERS M.C., ZWINDERMAN A.H., BEL E.H., DIJKMAN J.H., STERK P.J. Long-term effects of a long-acting beta2-adrenoceptor agonist, salmeterol, on airway hyperresponsiveness in patients with mild asthma. New Engl. J. Med. 1992;327:1198–1203. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210223271703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOMCZYNSKI P., SACCHI N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLUZEL M., BOUSQUET J., DAURES J.P., RENON D., CLAUZEL A.M., GODARD P.H., MICHEL F.B. Ambulatory long-term subcutaneous salbutamol infusion in chronic severe asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1990;85:599–606. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(90)90099-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DROTAR D.E., DAVIS E.E., COCKCROFT D.W. Tolerance to the bronchoprotective effect of salmeterol 12 hours after starting twice daily treatment. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;80:31–34. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62935-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FINNEY P.A., BELVISI M.G., DONNELLY L.E., CHUANG T.T., MAK J.C., SCORER C., BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M., GIEMBYCZ M.A. Albuterol-induced downregulation of Gsα accounts for pulmonary β2-adrenoceptor desensitization in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:125–135. doi: 10.1172/JCI8374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDERICKS Z.L., PITCHER J.A., LEFKOWITZ R.J. Identification of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase phosphorylation sites in the human β2-adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:13796–13803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDIE R.G., SPINA D., HENRY P.J., LULICH K.M., PATERSON J.W. In vitro responsiveness of human asthmatic bronchus to carbachol, histamine, β-adrenoceptor agonists and theophylline. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1986;22:669–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1986.tb02956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN S.A., SPASOFF A.P., COLEMAN R.A., JOHNSON M., LIGGETT S.B. Sustained activation of a G protein-coupled receptor via ‘anchored' agonist binding. Molecular localization of the salmeterol exosite within the β2-adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:24029–24035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.24029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRSHAM C.A., DOWNES H.Experimental asthma in animals Bronchial Asthma–Mechanisms and Therapeutics 1985Little, Brown & Co: Boston; 280–299.2nd edn. (eds.) Weiss, E.B., Segal, M.S. & Stein, M [Google Scholar]

- HIGHAM M.A., SHARARA A.M., WILSON P., JENKINS R.J., GLENDENNING G.A., IND P.W. Dose equivalence and bronchoprotective effects of salmeterol and salbutamol in asthma. Thorax. 1997;52:975–980. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.11.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IACCARINO G., TOMHAVE E.D., LEFKOWITZ R.J., KOCH W.J. Reciprocal in vivo regulation of myocardial G protein-coupled receptor kinase expression by β-adrenergic receptor stimulation and blockade. Circulation. 1998;98:1783–1789. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.17.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONZETT H., RÖSSLER R. Versuchsanordnung zu untersuchungen an der bronchialmuskulatur. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch. Exp. Path. Pharmacol. 1940;195:71–74. [Google Scholar]

- KRUPNICK J.G., BENOVIC J.L. The role of receptor kinases and arrestins in G protein-coupled receptor regulation. Ann. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1998;38:289–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOHSE M.J. Molecular mechanisms of membrane receptor desensitization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1179:171–188. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90139-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOHSE M.J., BENOVIC J.L., CODINA J., CARON M.G., LEFKOWITZ R.J. β-Arrestin: a protein that regulates β-adrenergic receptor function. Science. 1990;248:1547–1550. doi: 10.1126/science.2163110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOISEL T.P., ANSANAY H., ADAM L., MARULLO S., SEIFERT R., LAGACE M., BOUVIER M. Activation of the β2-adrenergic receptor-Gαs complex leads to rapid depalmitoylation and inhibition of repalmitoylation of both the receptor and Gαs. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:31014–31019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.31014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LYDFORD S.J., MCKECHNIE K. Characterization of the prostaglandin E2 sensitive (EP)-receptor in the rat isolated trachea. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;112:133–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAK J. C., NISHIKAWA M., SHIRASAKI H., MIYAYASU K., BARNES P.J. Protective effects of a glucocorticoid on downregulation of pulmonary β2-adrenergic receptors in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:99–106. doi: 10.1172/JCI118084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANCHEE G.R., BARROW A., KULKARNI S., PALMER E., OXFORD J., COLTHUP P. V., MACONACHIE J.G., TARBIT M.H. Disposition of salmeterol xinafoate in laboratory animals and humans. Drug Met. Disp. 1993;21:1022–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAYOR F., BENOVIC J.L., CARON M.G., LEFKOWITZ R.J. Somatostatin induces translocation of the β-adrenergic receptor kinase and desensitizes somatostatin receptors in S49 lymphoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:6468–6471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAYOR F., PENELA P., RUIZ-GOMEZ A. Role of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 and arrestins in β-adrenergic receptor internalization. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 1998;8:234–240. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(98)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLIGAN G. Agonist regulation of cellular G protein levels and distribution: mechanisms and functional implications. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1993;14:413–418. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90064-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOHAMMED S.P., TAYLOR C.V., WEYMAN-JONES C.B., MATHER M.E. , VEND Y.K., DOUGALL I.G., YOUNG A. Duration of action of inhaled vs. intravenous β2-adrenoceptor agonists in an anaesthetized guinea-pig model. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000;13:287–292. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2000.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NERME V., ABRAHAMSSON T., VAUQUELIN G. Chronic isoproterenol administration causes altered β-adrenoceptor-Gs-coupling in guinea pig lung. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;252:1341–1346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEWNHAM D.M., GROVE A., MCDEVITT D.G., LIPWORTH B.J. Subsensitivity of bronchodilator and systemic β2-adrenoceptor responses after regular twice daily treatment with eformoterol dry powder in asthmatic patients. Thorax. 1995;50:497–504. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.5.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEWNHAM D.M., MCDEVITT D.G., LIPWORTH B.J. Bronchodilator subsensitivity after chronic dosing with eformoterol in patients with asthma. Am. J. Med. 1994;97:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIKAWA M., MAK J.C., SHIRASAKI H., BARNES P.J. Differential down-regulation of pulmonary β1- and β2- adrenoceptor messenger RNA with prolonged in vivo infusion of isoprenaline. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;247:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(93)90070-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIKAWA M., MAK J.C., SHIRASAKI H., HARDING S.E., BARNES P.J. Long-term exposure to norepinephrine results in down-regulation and reduced mRNA expression of pulmonary β-adrenergic receptors in guinea pigs. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1994;10:91–99. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.1.8292387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'DRISCOLL B.R., RUFFLES S.P., AYRES J.G., COCHRANE G.M. Long-term treatment of severe asthma with subcutaneous terbutaline. Br. J. Dis. Chest. 1988;82:360–367. doi: 10.1016/0007-0971(88)90089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAULSSEN R.H., PAULSSEN E.J., GAUTVIK K.M., GORDELADZE J.O. The thyroliberin receptor interacts directly with a stimulatory guanine nucleotide-binding protein in the activation of adenylyl cyclase in GH3 rat pituitary tumour cells. Evidence obtained by the use of antisense RNA inhibition and immunoblocking of the stimulatory guanine nucleotide-binding protein. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;204:413–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PENN R.B., SHAVER J.R., ZANGRILLI J.G., POLLICE M., FISH J.E., PETERS S.P., BENOVIC J.L. Effect of inflammation and acute β-agonist inhalation on β2-AR signaling in human airways. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:L601–L608. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.4.L601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PREMONT R.T., INGLESE J., LEFKOWITZ R.J. Protein kinases that phosphorylate activated G protein-coupled receptors. FASEB J. 1995;9:175–182. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.2.7781920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RABE K.F., JORRES R., NOWAK D., BEHR N., MAGNUSSEN H. Comparison of the effects of salmeterol and formoterol on airway tone and responsiveness over 24 hours in bronchial asthma. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1993;147:1436–1441. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.6_Pt_1.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RANSNAS L.A., SVOBODA P., JASPER J.R., INSEL P.A. Stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors of S49 lymphoma cells redistributes the α-subunit of the stimulatory G protein between cytosol and membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1989;86:7900–7903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RONG Y., ARBABIAN M., THIRIOT D.S., SEIBOLD A., CLARK R.B., RUOHO A.E. Probing the salmeterol binding site on the β2-adrenergic receptor using a novel photoaffinity ligand, [125I]iodoazidosalmeterol. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11278–11286. doi: 10.1021/bi9910676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROUX F.J., GRANDORDY B., DOUGLAS J.S. Functional and binding characteristics of long-acting β2-agonists in lung and heart. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996;153:1489–1495. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEYBOLD J., NEWTON R., WRIGHT L., FINNEY P.A., SUTTORP N., BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M., GIEMBYCZ M.A. Induction of phosphodiesterases 3B, 4A4, 4D1, 4D2, and 4D3 in Jurkat T-cells and in human peripheral blood T-lymphocytes by 8-bromo-cAMP and Gs-coupled receptor agonists. Potential role in β2-adrenoreceptor desensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:20575–20588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMONS F.E., GERSTNER T.V., CHEANG M.S. Tolerance to the bronchoprotective effect of salmeterol in adolescents with exercise-induced asthma using concurrent inhaled glucocorticoid treatment. Pediatrics. 1997;99:655–659. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.5.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN LIEFDE I., VAN ERMEN A., VAN WITZENBURG A., FRAEYMAN N., VAUQUELIN G. Species- and strain-related differences in the expression and functionality of β-adrenoceptor subtypes in adipose tissue. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 1994;327:69–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEDEGAERTNER P.B., BOURNE H.R. Activation and depalmitoylation of Gsα. Cell. 1994;77:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90445-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEDEGAERTNER P.B., BOURNE H.R., VON ZASTROW M. Activation-induced subcellular redistribution of Gsα. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1996;7:1225–1233. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.8.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZEIDERS J.L., SEIDLER F.J., SLOTKI T.A. Ontogeny of regulatory mechanisms for β-adrenoceptor control of rat cardiac adenylyl cyclase: targeting of a G-protein and cyclase catalytic subunit. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:603–615. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]