Abstract

Lysosphingolipids such as sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP) and sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPPC) can act on specific G-protein-coupled receptors. Since SPP and SPPC cause renal vasoconstriction, we have investigated their effects on urine and electrolyte excretion in anaesthetized rats.

Infusion of SPP (1 – 30 μg kg−1 min−1) for up to 120 min dose-dependently but transiently (peak after 15 min, disappearance after 60 min) reduced renal blood flow without altering endogenous creatinine clearance. Nevertheless, infusion of SPP increased diuresis, natriuresis and calciuresis and, to a lesser extent, kaliuresis. These tubular lysosphingolipid effects developed more slowly (maximum after 60 – 90 min) and also abated more slowly upon lysosphingolipid washout than the renovascular effects.

Infusion of SPPC, sphingosine and glucopsychosine (3 – 30 μg kg−1 min−1 each) caused little if any alterations in renal blood flow but also increased diuresis, natriuresis and calciuresis and, to a lesser extent, kaliuresis.

Pretreatment with pertussis toxin (10 μg kg−1 3 days before the acute experiment) abolished the renovascular and tubular effects of 30 μg kg−1 min−1 SPP.

These findings suggest that lysosphingolipids are a hitherto unrecognized class of endogenous modulators of renal function. SPP affects renovascular tone and tubular function via receptors coupled to Gi-type G-proteins. SPPC, sphingosine and glucopsychosine mimic only the tubular effects of SPP, and hence may act on distinct sites.

Keywords: Sphingosine-1-phosphate, sphingosylphosphorylcholine, sphingosine, glucopsychosine, renal blood flow, diuresis, natriuresis, calciuresis, kaliuresis

Introduction

Lysosphingolipids such as sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP) and sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPPC) have long been known as intracellular bioactive molecules, but recently they have also emerged as representatives of a novel class of intercellular messengers (Goetzl & An, 1998; Meyer zu Heringdorf et al., 1997; Spiegel & Milstien, 2000). In that function lysosphingolipids may act mainly in an auto- or paracrine manner, but considerable SPP concentrations have also been detected in human serum and plasma, i.e. 484±82 and 191±79 nmol l−1, respectively (Yatomi et al., 1997a). Serum and plasma SPP may result at least partly from platelets which can release it upon activation (Yatomi et al., 1995). As intercellular messengers lysosphingolipids act on specific receptors, some of which couple to pertussis toxin (PTX) sensitive G-proteins (Goetzl & An, 1998; Meyer zu Heringdorf et al., 1997). While some members of the Edg receptor family are preferentially activated by lysophosphatidic acid, Edg1, Edg3, Edg5, Edg6 and Edg 8 are preferentially activated by SPP (Im et al., 2000; Lynch & Im, 1999; Pyne & Pyne, 2000; van Brocklyn et al., 2000; Yamazaki et al., 2000), and the previously cloned orphan receptor OGR1 has recently been identified as an SPPC-preferring receptor (Xu et al., 2000).

The kidney is the organ with the greatest impact on long-term blood pressure control and hence plays an important role in the regulation of the cardiovascular system (Guyton, 1991). Therefore, renal function is tightly regulated by a network of neuro-humoral control mechanisms. The kidney contains SPP (Yatomi et al., 1997b), which may be derived from the SPP content in platelets or plasma (Yatomi et al., 1995; 1997a) or synthesized locally from sphingosine (SPH) by a renal sphingosine kinase (Gijsbers et al., 1999; Olivera et al., 1998). At least some of the cloned Edg receptors are expressed in the kidney (An et al., 1999; Lado et al., 1994), and cellular lysosphingolipid effects have also been observed in kidney-derived cell lines such as HK-2 human proximal tubular cells (Iwata et al., 1995). Moreover, lysosphingolipids may affect renal function indirectly due to renal vasoconstriction, which we have recently described for SPP, SPPC, SPH and glucopsychosine (GLU) in vitro and, at least for SPP, in vivo (Bischoff et al., 2000a, 2000b). Based on these findings, we have now investigated whether lysosphingolipids can regulate renal function. In the present study we report that systemically infused SPP can alter renovascular and tubular function in anaesthetized rats in a PTX-sensitive manner, whereas SPPC, SPH and GLU alter tubular functions in the absence of detectable renovascular effects.

Methods

Animal surgery and experimental protocols for anaesthetized rat experiments

All studies were performed following approval by the state animal welfare board at the Regierungspräsident Düsseldorf. Male Wistar rats (strain: Hsd/Cpb:WU; study 1 : 270 – 416 g; study 2 : 292 – 463 g) were obtained from Harlan (Borchem, Germany, study 1) or from the breeding facility at the University of Essen (study 2).

For the acute experiment, animals were prepared as previously described (Bischoff et al., 1996) with minor modifications. Briefly, the rats were anaesthetized with a single dose of thiobutabarbitone (100 mg kg−1 i.p.) and placed on a heating pad to maintain the body temperature at 37°C. Following tracheotomy to facilitate ventilation, the left femoral artery was cannulated for monitoring mean arterial pressure (MAP) via a Statham pressure transducer. The femoral vein was catheterized for volume substitution and lysosphingolipid infusion. Following an abdominal midline incision, both ureters were cannulated for urine sampling. The connective tissue was carefully dissected from the right renal artery and an electromagnetic blood flow sensor (Skalar MDL 1401, Föhr Medical Instruments GmbH, Seeheim/Oberbeerbach, Germany) was placed on the vessel for monitoring renal blood flow (RBF). The signals from the flow sensor and the pressure transducer were continuously recorded online using the HDAS haemodynamic data acquisition system (Dept. of Bioengineering, Rijksuniversiteit Limburg, Maastricht, The Netherlands). Thereafter, fluid substitution was started at a rate of 60 μl min−1 to allow equilibration.

In study 1, vehicle (bovine serum albumin, 1 mg ml−1), 1, 3, 10 or 30 μg kg−1 min−1 SPP or 3, 10 or 30 μg kg−1 min−1 SPPC, SPH or GLU was infused via the femoral vein after an equilibration period of 180 min with total infusion rate maintained at 60 μl min−1 for a period of 120 min; this was followed by a 60 min washout period with vehicle infusion. Each rat received only one dose of lysosphingolipid (n=5 for 30 μg kg−1 min−1 SPH, n=6 for 3 μg kg−1 min−1 SPH, n=7 each for 1, 3 and 30 μg kg−1 min−1 SPP, 10 μg kg−1 min−1 SPH and 3, 10 and 30 μg kg−1 min−1 GLU, n=8 each for 3 and 10 μg kg−1 min−1 SPPC and n=9 each for vehicle, 10 μg kg−1 min−1 SPP and 30 μg kg−1 min−1 SPPC).

For study 2, the rats were pre-treated with PTX or vehicle (phosphate buffer) 3 days before the acute experiment. PTX (10 μg kg−1) was injected into the jugular vein under a light ketamine anaesthesia (100 mg kg−1 i.p.). PTX treatment had no major effects on body weight or animal behaviour. On the day of the experiment, the rats were allowed a 60 min recovery period after completion of surgery. Thereafter, the effectiveness of PTX-treatment was assessed by bolus injections of three neuropeptide Y doses (1, 3 or 10 μg kg−1) in 5 min intervals which caused peak RBF reductions of 0.7±0.1, 1.1±0.3 and 2.1±0.4 ml min−1 in vehicle but only 0.2±0.1, 0.6±0.2 and 0.5±0.1 ml min−1 in PTX-treated rats (n=14). This was followed by another 60 min of equilibration. Four groups of rats (n=7 each), which had been treated with PTX or vehicle, were infused with SPP (30 μg kg−1 min−1) or vehicle for 60 min.

In both studies, MAP and RBF were measured every 5 min during the whole experimental period; during the first 10 min of lysosphingolipid infusion they were quantitated every minute. Urine was collected in pre-weighed tubes at 15 min intervals. At the end of the experiment a blood sample was taken from the abdominal aorta, and subsequently the rats were killed with an overdose of anaesthetic. Urine formation was quantitated gravimetrically assuming a specific gravity of 1.0 kg l−1, and samples were stored at 4°C until analysis. Serum was prepared from the aortic blood sample by centrifugation (10 min at 5000×g) and stored at −20°C until analysis. Urinary electrolyte concentrations were determined with an Eppendorf flame photometer. Urinary and serum creatinine was determined with a photometrical test kit.

Chemicals

SPP and SPPC were obtained from Biomol (Hamburg, Germany) and SPH and GLU from Matreya (Bad Homburg, Germany); they were dissolved in methanol, dried in a SpeedVac concentrator, redissolved in 1 ml bovine serum albumin solution and further diluted with 0.9% saline. Thiobutabarbitone (Inactin®) was obtained from RBI (Natick, MA, U.S.A.). PTX was obtained from ICN (Eschwege, Germany) and dissolved in a phosphate buffer (0.05 mol l−1 NaCl, 0.01 mol l−1 NaH2PO4 and 0.01 mol l−1 Na2HPO4) that served as vehicle.

Data analysis

Data are shown as mean±s.e.mean of n experiments. The averages of the haemodynamic parameters during the last 3 min before the start of the infusion were taken as baseline values. The averages of the urinary parameters were taken from the last three urine collection periods before lysosphingolipid infusion. All other data are shown relative to these baseline values of the individual animal. Statistical significance of the lysosphingolipid effects over time relative to vehicle was determined by a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the overall time course. Statistical significance of PTX effects on baseline values was determined by an unpaired two-tailed t-test. All statistical calculations were performed with the Prism program (GraphPAD Software, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) and P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Study 1

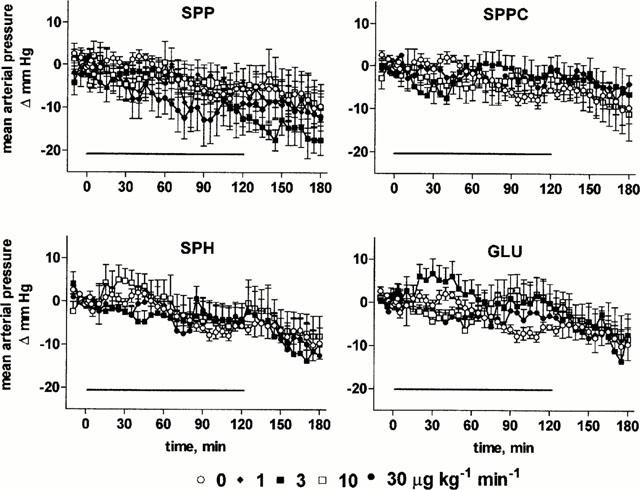

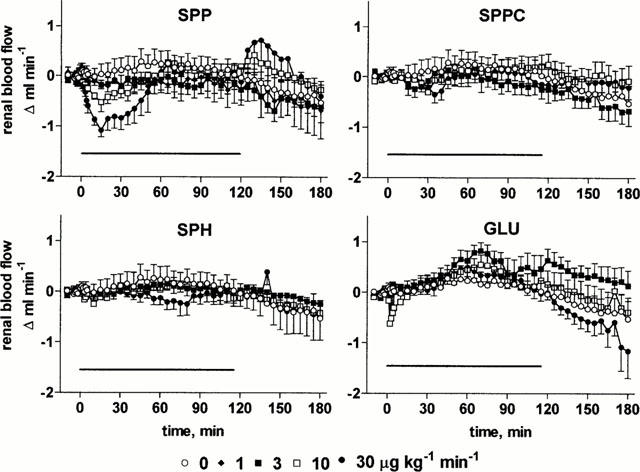

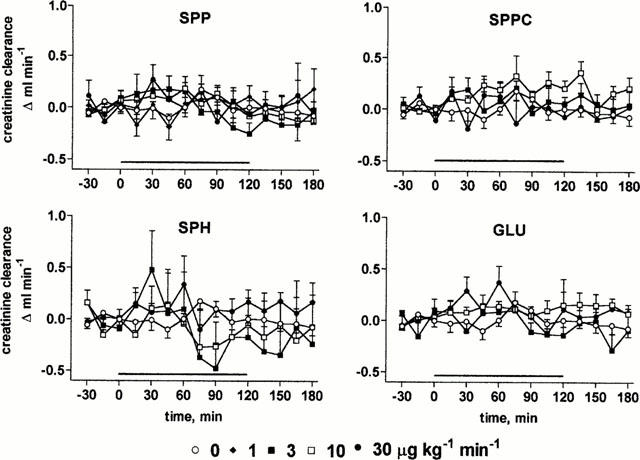

At the end of the recovery period, MAP and RBF had stabilized at 108±1 mm Hg and 6.4±0.1 ml min−1 (n=103 for all rats of study 1), respectively. In agreement with our previous data on lysosphingolipid bolus injections (Bischoff et al., 2000b), infusion of SPP (1 – 30 μg kg−1 min−1) or the other lysosphingolipids (3 – 30 μg kg−1 min−1) caused only minor if any (⩽5 mmHg) alterations of MAP relative to vehicle (Figure 1). Nevertheless, infusion of SPP lowered RBF with maximal reductions of 1.1±0.1 ml min−1, i.e. ≈ 17%, occurring 15 min after start of the infusion (Figure 2). SPP-induced RBF alterations were transient, and RBF returned towards baseline despite continued SPP infusion within the next 45 min. A two-way ANOVA of the pooled data of all SPP doses with time and administered dose as explanatory variables demonstrated significant dose-dependency of the SPP-induced RBF reductions (P=0.0026). After termination of the infusion, a rebound RBF increase was observed with the higher SPP doses (Figure 2). In contrast, infusion of up to 30 μg kg−1 min−1 SPPC, SPH or GLU did not markedly alter RBF (Figure 2). Basal endogenous creatinine clearance at the end of the recovery period was 1.3±0.1 ml min−1 (n=103), and this was not significantly altered by any of the lysosphingolipids in any of the tested doses (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Effects of systemic lysosphingolipid infusion on mean arterial pressure in anaesthetized rats. Data are mean±s.e.mean of 5 – 9 animals per group expressed as alteration relative to basal values (108±1 mmHg). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP), sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPPC), sphingosine (SPH) and glucopsychosine (GLU) were infused from 0 – 120 min (indicated by the horizontal bar) at 1, 3, 10 or 30 μg kg−1 min−1. Relative to vehicle the effects of 30 μg kg−1 min−1 SPP were statistically significant (P<0.05) in a two-way ANOVA testing for overall treatment effect during infusion.

Figure 2.

Effects of systemic lysosphingolipid infusion on renal blood flow in anaesthetized rats. Data are mean±s.e.mean of 5 – 9 animals per group expressed as alteration relative to basal values (6.4±0.1 ml min−1). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP), sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPPC), sphingosine (SPH) and glucopsychosine (GLU) were infused from 0 – 120 min (indicated by the horizontal bar) at 1, 3, 10 or 30 μg kg−1 min−1. Relative to vehicle the effects of 3 and 30 μg kg−1 min−1 SPP were statistically significant (P<0.05) in a two-way ANOVA testing for overall treatment effect during infusion.

Figure 3.

Effects of systemic lysosphingolipid infusion on endogenous creatinine clearance in anaesthetized rats. Data are mean±s.e.mean of 5 – 9 animals per group expressed as alteration relative to basal values (1.3±0.1 ml min−1). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP), sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPPC), sphingosine (SPH) and glucopsychosine (GLU) were infused from 0 – 120 min (indicated by the horizontal bar) at 1, 3, 10 or 30 μg kg−1 min−1.

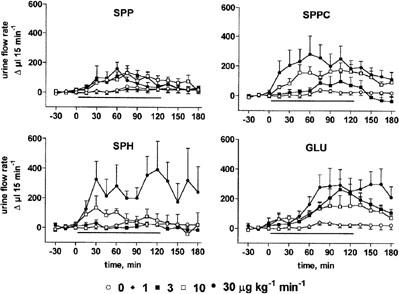

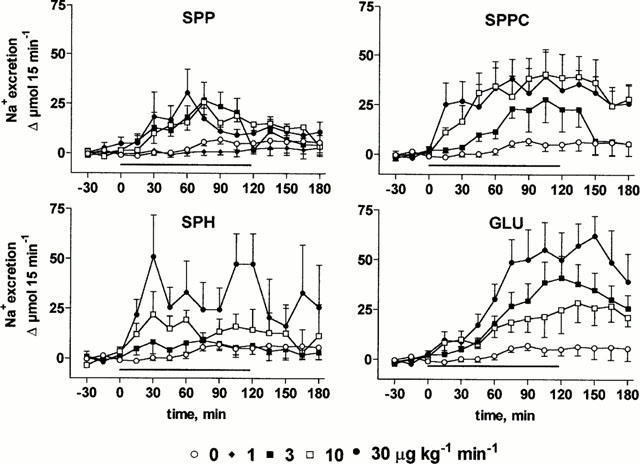

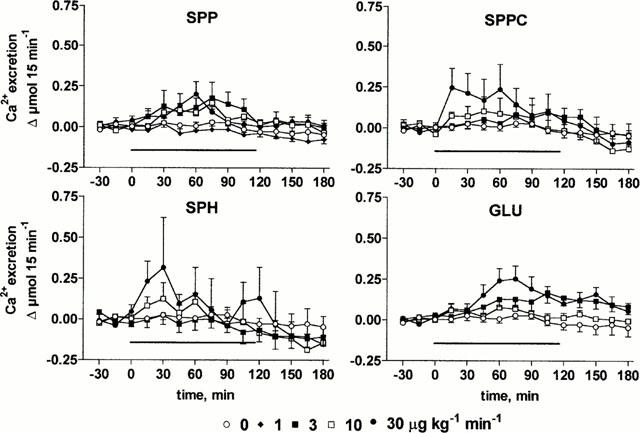

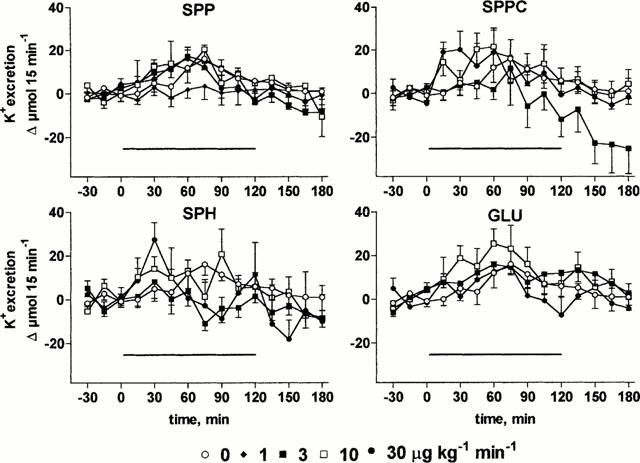

At the end of the recovery period, urine flow rate and Na+, Ca2+ and K+ excretions were 156±9 μl 15 min−1 and 21±2 μmol 15 min−1, 0.25±0.03 μmol 15 min−1 and 48±2 μmol 15 min−1 (n=103), respectively, and remained stable throughout the experimental period upon vehicle infusion (Figures 4, 5, 6, 7). Infusion of SPP increased urine, Na+ and Ca2+ excretion up to approximately 2 fold (Figures 4, 5, 6, 7). In contrast, SPP infusion caused only small if any increases of K+ excretion (Figure 7), and accordingly urinary K+ concentration declined during SPP infusion (data not shown). The increases of urine and electrolyte excretion developed slowly and peaked 60 min after start of the infusion; only slow abatement was seen during washout. Within the investigated dosage range, little dose-dependency of SPP-induced urine and electrolyte excretion was observed with 1 μg kg−1 min−1 being without detectable effect, and 3, 10 and 30 μg kg−1 min−1 all being similarly effective. Although SPPC, SPH and GLU largely lacked renovascular effects (Figure 2), they enhanced urine, Na+ and Ca2+ excretion in a qualitatively similar way as SPP but caused only little if any alterations of K+ excretion (Figures 4, 5, 6, 7). Maximal enhancements of urine and electrolyte excretion by 30 μg kg−1 min−1 SPPC, SPH and GLU were about twice as large as those of SPP.

Figure 4.

Effects of systemic lysosphingolipid infusion on urine flow rate in anaesthetized rats. Data are mean±s.e.mean of 5 – 9 animals per group expressed as alteration relative to basal values (156±9 μl 15 min−1). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP), sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPPC), sphingosine (SPH) and glucopsychosine (GLU) were infused from 0 – 120 min (indicated by the horizontal bar) at 1, 3, 10 or 30 μg kg−1 min−1. Relative to vehicle the effects of 3 – 30 μg kg−1 min−1 of SPP, SPPC, SPH (except for 3 μg kg−1 min−1) and GLU were statistically significant (P<0.05) in a two-way ANOVA testing for overall treatment effect during infusion.

Figure 5.

Effects of systemic lysosphingolipid infusion on Na+ excretion in anaesthetized rats. Data are mean±s.e.mean of 5 – 9 animals per group expressed as alteration relative to basal values (21±2 μmol 15 min−1). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP), sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPPC), sphingosine (SPH) and glucopsychosine (GLU) were infused from 0 – 120 min (indicated by the horizontal bar) at 1, 3, 10 or 30 μg kg−1 min−1. Relative to vehicle the effects of 3 – 30 μg kg−1 min−1 of SPP, SPPC, SPH and GLU were statistically significant (P<0.05) in a two-way ANOVA testing for overall treatment effect during infusion.

Figure 6.

Effects of systemic lysosphingolipid infusion on Ca2+ excretion in anaesthetized rats. Data are mean±s.e.mean of 5 – 9 animals per group expressed as alteration relative to basal values (0.25±0.03 μmol 15 min−1). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP), sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPPC), sphingosine (SPH) and glucopsychosine (GLU) were infused from 0 – 120 min (indicated by the horizontal bar) at 1, 3, 10 or 30 μg kg−1 min−1. Relative to vehicle the effects of 3 – 30 μg kg−1 min−1 of SPP and SPPC, of 10 μg kg−1 min−1 SPH and of 30 μg kg−1 min−1 GLU were statistically significant (P<0.05) in a two-way ANOVA testing for overall treatment effect during infusion.

Figure 7.

Effects of systemic lysosphingolipid infusion on K+ excretion in anaesthetized rats. Data are mean±s.e.mean of 5 – 9 animals per group expressed as alteration relative to basal values (48±2 μmol 15 min−1). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP), sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPPC), sphingosine (SPH) and glucopsychosine (GLU) were infused from 0 – 120 min (indicated by the horizontal bar) at 1, 3, 10 or 30 μg kg−1 min−1. Relative to vehicle the effects of 3 μg kg−1 min−1 SPPC, of 3 and 10 μg kg−1 min−1 SPH and of 10 μg kg−1 min−1 GLU were statistically significant (P<0.05) in a two-way ANOVA testing for overall treatment effect during infusion.

Study 2

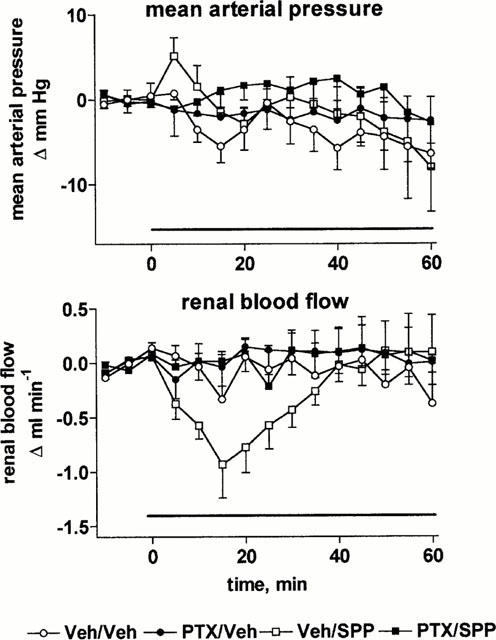

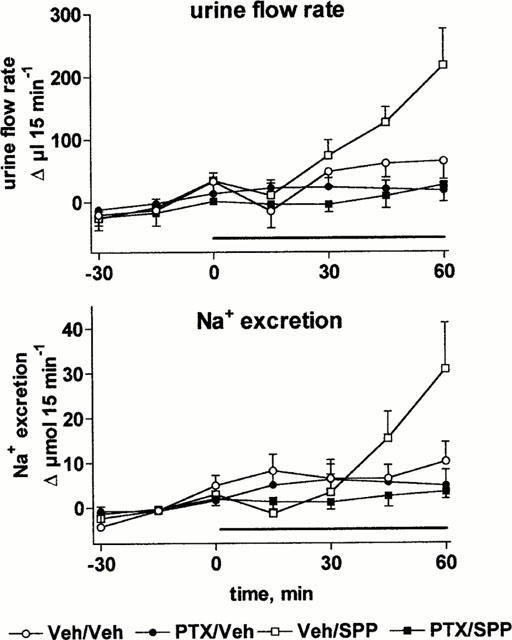

In PTX-treated rats basal values of MAP (85±2 vs 113±2 mmHg) and urine flow rate (98±21 vs 180±27 μl 15 min−1) were significantly lower than in vehicle-treated rats (n=14 each, P<0.05), while alterations of RBF (7.1±0.6 vs 8.0±0.4 ml min−1) and Na+ excretion (10±4 vs 17±5 μmol 15 min−1) did not reach statistical significance. As in study 1 (Figure 1), infusion of SPP (30 μg kg−1 min−1) for 60 min did not markedly alter MAP relative to vehicle in control or PTX-treated rats (Figure 8). SPP-induced reductions of RBF (Figure 8) and enhancements of urine and Na+ excretion were abolished in PTX-treated rats (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Effects of systemic vehicle (Veh) or sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP) infusion on mean arterial pressure and renal blood flow in pertussis toxin (PTX)- and vehicle-treated anaesthetized rats. Data are mean±s.e.mean of seven animals per group expressed as alteration relative to basal values (85±2 and 113±2 mmHg and 7.1±0.6 and 8.0±0.4 ml min−1). Veh and SPP (30 μg kg−1 min−1) was infused from 0 – 60 min in Veh and PTX-treated rats. Relative to vehicle, the effect of SPP on renal blood flow was statistically significant (P<0.05) in a two-way ANOVA testing for overall treatment effect during infusion in the vehicle-treated but not in the PTX-treated group.

Figure 9.

Effects of systemic vehicle (Veh) or sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP) infusion in pertussis toxin (PTX)- and vehicle-treated anaesthetized rats on urine flow rate and Na+ excretion. Data are mean±s.e.mean of seven animals per group expressed as alteration relative to basal values (98±21 and 180±27 μl 15 min−1 and 10±4 and 17±5 μmol 15 min−1). Veh and SPP (30 μg kg−1 min−1) was infused from 0 – 60 min in Veh and PTX-treated rats. Relative to vehicle, the effects of SPP on urine flow or Na+ excretion were statistically significant (P<0.05) in a two-way ANOVA testing for overall treatment effect during infusion in the vehicle-treated but not in the PTX-treated group.

Discussion

Previous reports have demonstrated the presence of sphingosine kinase (Gijsbers et al., 1999; Olivera et al., 1998), SPP (Yatomi et al., 1997b) and SPP receptors in the kidney (An et al., 1999; Lado et al., 1994). They have also demonstrated receptor-mediated renovascular effects of SPP and other lysosphingolipids in vitro and in vivo (Bischoff et al., 2000a, 2000b). Therefore, the present study was designed to determine the functional effects of SPP and the related lysosphingolipids SPPC, SPH and GLU in the kidney.

We have previously shown that the lysosphingolipids SPP, SPPC, SPH and GLU can constrict intrarenal blood vessels, i.e. interlobar arteries, in vitro (Bischoff et al., 2000a). Accordingly, intravenous bolus injections of SPP dose-dependently reduced RBF, and this effect was enhanced upon intrarenal injection (Bischoff et al., 2000b). In contrast, SPPC, SPH and GLU did not affect RBF upon intravenous bolus injection over a similar dose range, and caused only very weak if any RBF reduction upon intrarenal injection (Bischoff et al., 2000b). Similar findings were obtained in the present study for extended intravenous lysosphingolipid infusions using comparable dosages. Thus, RBF reduction in vivo appears to be a specific effect for SPP relative to other lysosphingolipids.

While not all receptor-mediated lysosphingolipid effects are PTX-sensitive, PTX sensitivity indicates receptor-mediated rather than intracellular effects (Pyne & Pyne, 2000). In the present study SPP infusion-induced reductions of RBF were abolished by PTX treatment. This confirms our previous conclusion based on bolus injections (Bischoff et al., 2000b) that SPP-induced renal vasoconstriction appears to be a receptor-mediated event.

Interestingly, the SPP-induced RBF reductions developed a rapid tachyphylaxis despite continued infusion, and a considerable rebound effect was seen upon washout. These data indicate the development of renovascular SPP receptor desensitization and/or the compensatory formation and/or release of renovascular vasodilator substances which maintain RBF in the presence of SPP-induced renal vasoconstriction.

Most renal vasoconstrictor neurotransmitters and hormones, e.g. endothelin-1, angiotensin II and noradrenaline, cause antidiuresis and antinatriuresis. Surprisingly, SPP enhanced urine and electrolyte excretion despite the reduction in RBF. The inhibition of SPP-induced diuresis and natriuresis by PTX indicates a receptor-mediated effect. Since SPP injections (Bischoff et al., 2000b; Sugiyama et al., 2000) or infusion (present study) did not increase MAP or glomerular filtration rate, the observed alterations in urine and electrolyte excretion appear to occur via tubular SPP receptors. The present finding that SPPC, SPH and GLU cause marked diuresis, natriuresis and calciuresis without altering RBF supports the idea that SPP causes diuresis, natriuresis and calciuresis via a tubular site of action, i.e. independent of its effects on RBF. Moreover, mRNA for Edg-1 and Edg-3 SPP receptors is present in rat and human kidney (An et al., 1999; Lado et al., 1994; Okazaki et al., 1993).

On the other hand, it should be noted that the hitherto cloned receptors with high affinity for SPP all have low affinity for SPPC (Lynch & Im, 1999), and the opposite holds true for the only cloned receptor with high affinity for SPPC (Xu et al., 2000). Moreover, the affinity of SPH and GLU for either group of receptors is either low or has not been determined, and thus it remains unclear whether they can cause receptor-mediated effects. Therefore, our data indicate that SPPC, SPH and GLU affect tubular function by one or multiple mechanisms distinct from those used by SPP. However, it remains possible that additional as yet unidentified receptors with similar affinity for SPP, SPPC, SPH and GLU exist in rat kidney tubules. Resolution of these possibilities will depend on further progress in the molecular identification of lysosphingolipid receptors.

The present data also allow a number of conclusions regarding physiological aspects of renal SPP effects. Thus, the unchanged endogenous creatinine clearance despite marked RBF reduction indicates that SPP-induced vasoconstriction occurs predominantly at the level of the vas efferens. While lysosphingolipid infusion markedly enhanced Na+ excretion, only minor if any enhancements of K+ excretion were seen, and urinary K+ concentrations even declined. This pattern of electrolyte excretion indicates that lysosphingolipids may primarily affect tubular function in a distal nephron segment. While the combination of reduced RBF, unchanged glomerular filtration rate and increased diuresis and natriuresis is unusual among neurohumoral regulators of renal function, it resembles effects seen with neuropeptide Y. Neuropeptide Y also causes RBF reduction via PTX-sensitive G-proteins, does not affect glomerular filtration rate and enhances diuresis, natriuresis and calciuresis but has only minor if any effect on urinary K+ excretion (Bischoff & Michel, 1998; 2000). Neuropeptide Y was shown to alter RBF and urine and electrolyte excretion via distinct receptor subtypes (Bischoff & Michel, 1998).

In summary, our data demonstrate for the first time that the endogenous lysosphingolipid SPP can alter renovascular and tubular function via a receptor-mediated mechanism in anaesthetized rats. Whether these effects are at least partly mediated by alterations of neuro-humoral systems such as vasopressin or the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system remains to be determined. SPPC, SPH and GLU mimic the tubular but not the renovascular SPP effects, and hence appear to act via one or more distinct mechanisms. These findings identify a novel class of endogenous regulators of renal function and could help to understand the postulated role of lysosphingolipids in renal disease particularly in diabetic nephropathy and polycystic kidney disease (Shayman, 1996).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Bi 544/2-1) and the intramural grant program of the Universitätsklinikum Essen (IFORES).

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- GLU

glucopsychosine

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- RBF

renal blood flow

- SPH

sphingosine

- SPP

sphingosine-1-phosphate

- SPPC

sphingosylphosphorylcholine

References

- AN S., GOETZL E.J., LEE H. Signaling mechanisms and molecular characteristics of G protein-coupled receptors for lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine-1-phosphate. J. Cell. Biochem. 1999;30–31 Suppl.:147–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISCHOFF A., CZYBORRA P., FETSCHER C., MEYER ZU HERINGDORF D., JAKOBS K.H., MICHEL M.C. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and sphingosylphosphorylcholine constrict renal and mesenteric microvessels in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000a;130:1871–1877. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISCHOFF A., CZYBORRA P., MEYER ZU HERINGDORF D., JAKOBS K.H., MICHEL M.C. Sphingosine-1-phosphate reduces rat renal and mesenteric blood flow in vivo in a pertussis toxin-sensitive manner. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000b;130:1878–1883. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISCHOFF A., ERDBRÜGGER W., SMITS J., MICHEL M.C. Neuropeptide Y-enhanced diuresis and natriuresis in anaesthetized rats in independent from renal blood flow reduction. J. Physiol. (London) 1996;495:525–534. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISCHOFF A., MICHEL M.C. Renal effects of neuropeptide Y. Pflügers Arch. 1998;435:443–453. doi: 10.1007/s004240050538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISCHOFF A., MICHEL M.C. Neuropeptide Y enhances potassium excretion by mechanisms distinct from those contolling sodium excretion. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2000;78:93–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIJSBERS S., CAUSERET C., VAN DER HOEVEN G., VAN VELDHOVEN P.P. Sphingosine kinase: assay conditions, tissue distribution in rat, and subcellular localization in rat kidney and liver. Lipids. 1999;34 Suppl.:S77–S77. doi: 10.1007/BF02562236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOETZL E.J., AN S. Diversity of cellular receptors and functions for the lysophospholipid growth factors lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine 1-phosphate. FASEB J. 1998;12:1589–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUYTON A.C. Blood pressure control–special role of the kidneys and body fluids. Science. 1991;252:1813–1816. doi: 10.1126/science.2063193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IM D.-S., HEISE C.E., ANCELLIN N., O'DOWD B.F., SHEI G., HEAVENS R.P., RIGBY M.R., HLA T., MANDALA S., MCALLISTER G., GEORGE S.R., LYNCH K.R. Characterization of a novel sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor, Edg-8. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:14281–14286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IWATA M., HERRINGTON J., ZAGER R.A. Sphingosine: a mediator of acute renal tubular injury and subsequent cytoresistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:8970–8974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LADO D.C., BROWE C.S., GASKIN A.A., BORDEN J.M., MACLENNAN A.J. Cloning of the rat edg-1 immediate-early gene: expression pattern suggests diverse functions. Gene. 1994;149:331–336. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LYNCH K.R., IM D.-S. Life on the edg. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:473–475. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYER ZU HERINGDORF D., VAN KOPPEN C.J., JAKOBS K.H. Molecular diversity of sphingolipid signalling. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:34–38. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKAZAKI H., ISHIZAKA N., SAKURAI T., KUROKAWA K., GOTO K., KUMADA M., TAKUWA Y. Molecular cloning of a novel putative G protein-coupled receptor expressed in the cardiovascular system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;190:1104–1109. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLIVERA A., KOHAMA T., TU Z., MILSTIEN S., SPIEGEL S. Purification and characterization of rat kidney sphingosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12576–12583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PYNE S., PYNE N.J. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signalling in mammalian cells. Biochem. J. 2000;349:385–402. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAYMAN J.A. Sphingolipids: their role in intracellular signaling and renal growth. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1996;7:171–182. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V72171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPIEGEL S., MILSTIEN S. Functions of a new family of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1484:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUGIYAMA A., AYE N.N., YATOMI Y., OZAKI Y., HASHIMOTO K. Effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate, a naturally occurring biologically active lysophospholipid, on the rat cardiovascular system. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 2000;82:338–342. doi: 10.1254/jjp.82.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN BROCKLYN J.R., GRÄLER M.H., BERNHARDT G., HOBSON J.P., LIPP M., SPIEGEL S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate is a ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor EDG-6. Blood. 2000;95:2624–2629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU Y., ZHU K., HONG G., WU W., BAUDHUIN L.M., XIAO Y., DAMRON D.S. Sphingosylphosphorylcholine is a ligand for ovarian cancer G-protein-coupled receptor 1. Nature Cell Biol. 2000;2:261–267. doi: 10.1038/35010529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAZAKI Y., KON J., SATO K., TOMURA H., SATO M., YONEYA T., OKAZAKI H., OKAJIMA F., OHTA H. Edg-6 as a putative sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor coupling to Ca2+ signaling pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;268:583–589. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YATOMI Y., IGARASHI Y., YANG L., HISANO N., QI R., ASAZUMA N., SATOH K., OZAKI Y., KUME S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate, a bioactive sphingolipid abundantly stored in human platelets, is a normal constituent of human plasma and serum. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 1997a;121:969–973. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YATOMI Y., RUAN F., HAKOMORI S., IGARASHI Y. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: a platelet-activating sphingolipid released from agonist-stimulated human platelets. Blood. 1995;86:193–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YATOMI Y., WELCH R.J., IGARASHI Y. Distribution of sphingosine 1-phosphate, a bioactive sphingolipid, in rat tissues. FEBS Lett. 1997b;404:173–174. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]