Abstract

The roles of intracellular Ca2+ stores and ryanodine (Ry) receptors for vascular Ca2+ homeostasis and viability were investigated in rat tail arterial segments kept in organ culture with Ry (10 – 100 μM) for up to 4 days.

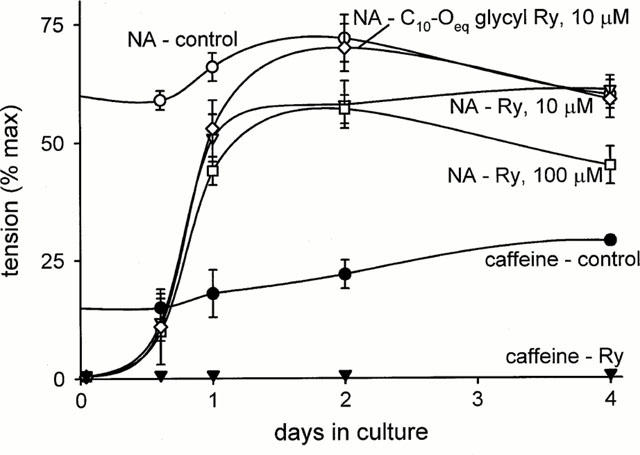

Acute exposure to Ry or the non-deactivating ryanodine analogue C10-Oeq glycyl ryanodine (10 μM) eliminated Ca2+ release responses to caffeine (20 mM) and noradrenaline (NA, 10 μM), whereas responses to NA, but not caffeine, gradually returned to normal within 4 days of exposure to Ry.

Ry receptor protein was detected on Western blots in arteries cultured either with or without Ry.

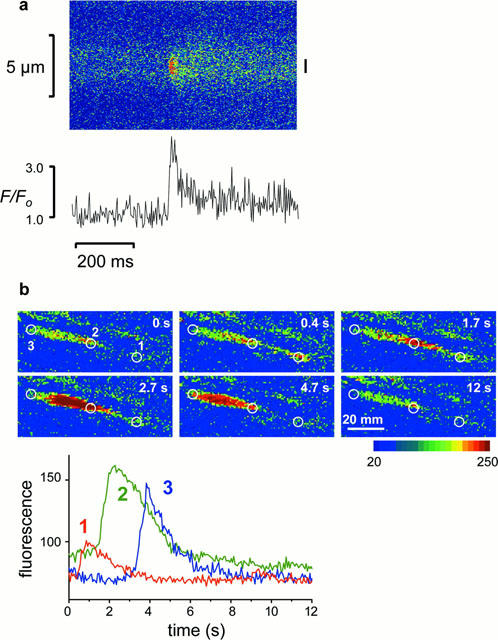

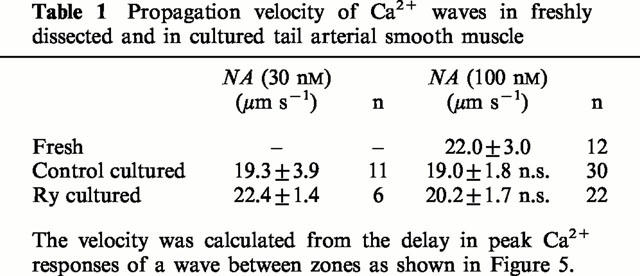

Brief Ca2+ release events (sparks) were absent after culture with Ry, whereas Ca2+ waves still occurred. The propagation velocity of waves was equal (∼19 μm s−1) in tissue cultured either with or without Ry.

Inhibition of Ca2+ accumulation into the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) by culture with caffeine (5 mM), cyclopiazonic acid or thapsigargin (both 10 μM) decreased contractility due to Ca2+-induced cell damage. In contrast, culture with Ry did not affect contractility.

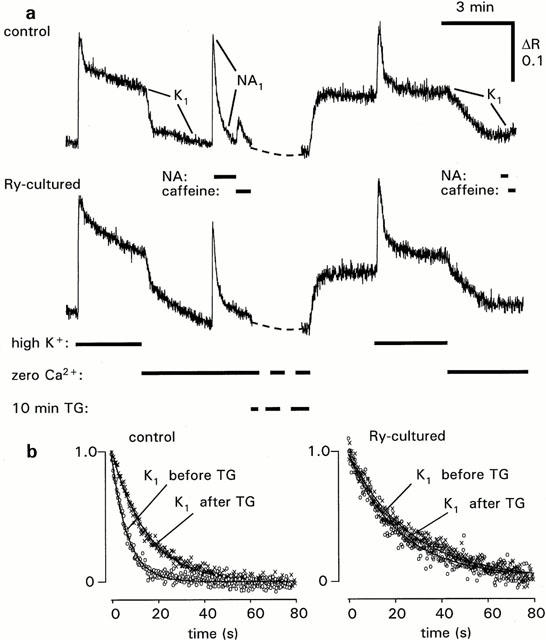

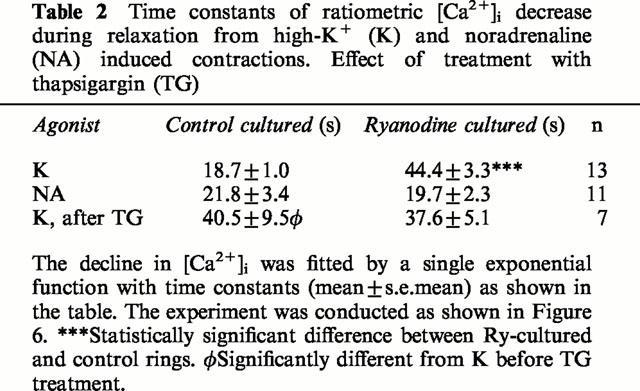

Removal of Ca2+ from the cytosol following a Ca2+ load was retarded after Ry culture. Thapsigargin reduced the rate of Ca2+ removal in control cultured rings, but had no effect after Ry culture.

It is concluded that intracellular Ca2+ stores recover during chronic Ry treatment, while Ry receptors remain non-functional. Ry receptor activity is required for Ca2+ sparks and for SR-dependent recovery from a Ca2+ load, but not for Ca2+ waves or basal Ca2+ homeostasis.

Keywords: Ryanodine receptors, smooth muscle, Ca2+ stores, sarcoplasmic reticulum, organ culture, Ca2+ sparks, Ca2+ waves

Introduction

A key event in excitation-contraction coupling is the release of calcium ions from intracellular stores in response to signals transmitted from the cell membrane. The function of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) in this process has been elucidated partially with the aid of the alkaloid ryanodine (Ry), originally extracted from the plant Ryania speciosa. Its direct action as a selective opener of calcium release channels in the SR has been thoroughly studied (Rousseau et al., 1987; Meissner, 1986; Bidasee et al., 1995) and Ry receptors are widely expressed, also in non-muscle tissues (Coronado et al., 1994). Release of Ca2+ via the receptor is induced by Ca2+ itself (Meissner et al., 1986), by depolarization (Kobayashi et al., 1986), or by agonists, such as cyclic ADP ribose (Lee, 1993). The activation via Ca2+ would provide a way of amplifying Ca2+ signals, and might also explain the spontaneous Ca2+-release events (sparks) that have been described in cells of many tissues (Cheng et al., 1993; Nelson et al., 1995).

Whereas the Ry receptor is the most important and perhaps only path for calcium release from SR in striated muscle, its role in smooth muscle function is less certain. The inositol trisphosphate (IP3) receptor has been shown to mediate agonist induced calcium release in all smooth muscles studied, and the intracellular production of IP3 correlates well with the time course of calcium release (Streb et al., 1985). IP3 receptors are also believed to be responsible for generation of cytosolic [Ca2+] waves (Iino et al., 1994; Hirose et al., 1999), though there is also evidence for a role of Ry receptors in wave propagation (Blatter & Wier, 1992; Boittin et al., 1999).

Problems of assessing the different mechanisms whereby the SR affects calcium homeostasis are mainly due to lack of appropriate pharmacological tools. For instance, distinguishing the different roles of IP3 and Ry receptors is difficult in the absence of selective blockers. The acute effect of Ry is to open its receptor/channel and thereby to empty Ca2+ stores, precluding SR accumulation of Ca2+. Since the Ry receptor and the IP3 receptor appear to be located to the same stores, or to rapidly communicating stores (Saida & van Breemen, 1984; Komori et al., 1995), Ry treatment will also abolish responses to agents acting through IP3. Inhibitors of the Ry receptor, such as ruthenium red, procaine and Mg2+ all have additional effects on muscle (Crompton et al., 1983; Benham et al., 1985).

All agents that deplete calcium stores greatly affect calcium homeostasis. Elevation of basal calcium level, increased net calcium influx, and slowed cellular extrusion of calcium ions are some of the main findings in muscle treated with Ry, SR Ca2+ pump inhibitors, or caffeine, which at high doses also acts to release Ca2+ via Ry receptors (Chen & van Breemen, 1992; Abe et al., 1996).

A recent advance in the field is the production of mice lacking expression of different Ry receptor subtypes (Takeshima et al., 1996; Barone et al., 1998). So far studies of these strains are sparse. The animals show abnormalities in calcium release patterns in skeletal muscle, but in smooth muscle, no abnormalities have so far been detected. One reason for this is that different Ry receptor isoforms may substitute for one another, while knockout of all Ry receptors would be lethal. Using antisense techniques in cultured portal venous cells, Coussin et al. (2000) have shown that the Ry receptor subtypes 1 and 2 are both required for Ca2+ spark activity and responses to caffeine, while deletion of subtype 3 has no effect.

Here we report a procedure that causes a selective blockade of Ry receptors in organized contractile vascular smooth muscle tissue in vitro, with maintenance of SR Ca2+ stores and IP3-induced Ca2+ release. This model was used to examine the role of Ry-receptors and the SR in controlling intracellular [Ca2+]i and preventing Ca2+-induced vascular damage.

Methods

Tissue preparation and culture

Female Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing ∼200 g, were killed by cervical dislocation. Tail arteries were dissected free under sterile conditions and transferred to nominally Ca2+-free Krebs solution containing (mM): KCl 4.7, NaHCO3 15.5, KH2PO4 1.2, MgCl2 1.2, glucose 11.5, NaCl 122, and 100 u ml−1 penicillin plus 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin. Connective tissue and fat cells were removed and the artery was cut into rings under a dissecting microscope. The width and luminal diameter of rings did not vary substantially and were approximately 0.6 and 0.5 mm, respectively. Rings were transferred to culture dishes containing culture medium (DMEM / Ham's F12 1 : 1 and antibiotics, as above). To some dishes Ry (10 – 100 μM), C10-Oeq glycyl ryanodine (10 μM), cyclopiazonic acid (10 μM), thapsigargin (10 μM), caffeine (5 mM), EGTA (0.88 mM), or KCl and CaCl2 (26 and 1.42 mM) were added. The dishes were placed in a water-jacketed cell incubator at 37°C under 5% CO2 in air.

Experimental procedure

Rings (fresh or cultured) were transferred to Ca2+-free Krebs solution without antibiotics. To remove endothelium, a thin needle was passed through the lumen of the ring. Rings were mounted on stainless steel hooks (diameter 0.2 mm). One of these was connected to a force transducer (AE 801, SensoNor A/S, Horten, Norway), and the other to an adjustable support. Rings were stretched to a final diameter of ∼0.6 mm, which produced a passive tension of 2.5±0.2 mN mm−1. This is close to the optimal preload for these preparations (Lindqvist et al., 1999). Preparations were immersed in warm HEPES-buffered solution containing (mM): NaCl 135.5, KCl 5.9, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 1.2, N-2-hydroxyethyl-piperazine-N′-2-ethanesulphonic acid (HEPES) 11.6, and glucose 11.5. High-K+ solution was prepared by replacing NaCl with KCl. Solution was contained in 0.4 ml Plexiglas cups fitted into thermostatted (35°C) metal blocks. In all experiments rings were allowed to equilibrate for at least 35 min before being stimulated. The width of each ring was measured at the end of experiments using a dissecting microscope equipped with an ocular scale. Wall tension was expressed as recorded force divided by twice the ring width.

Microsomal membrane isolation and Ry receptor immunoblotting

Tail arteries from >20 rats were cultured with or without Ry for 4 days, then washed in Ca2+-free Krebs solution, briefly blotted on a filter paper and frozen in liquid N2. Tissues were stored at −80°C until used. Samples (∼200 mg each) were pulverized in liquid N2 and transferred to 1.2 ml of ice cold isolation buffer (pH 7.4) containing (mM): 300 sucrose, 10 imidazole, 0.5 dithiothreitol, 0.5 phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride and (μg/ml) 10 trypsin inhibitor (type II-S), 1 leupeptin, 1 aprotinin. Homogenization was completed by two brief pulses of an ultra-turrax. The homogenates were centrifuged at 1000×g and then at 10,000×g, both for 10 min, and each time the pellets were discarded. Microsomal membrane pellets were then obtained by centrifugation for 60 min at 100,000×g (Beckman airfuge). Heart and ileum longitudinal smooth muscle fractions were obtained in the same way. The pellets were dissolved in 100 μl of a sample buffer containing 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride. Samples were denatured in boiling water for 3 min and cleared by centrifugation (14,000×g, 10 min). Proteins were separated by SDS – PAGE on a BioRad Minigel system using 5 or 7.5% polyacrylamide gels. Twenty-five microlitres of the sample was loaded on each lane and 200 V applied for 40 min. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane overnight at 30 V, 4°C. Membranes were blocked with 10% non fat dry milk for 2 h (room temperature) and subsequently incubated with anti-Ry receptor antibody (34C, or 110E, Airey et al., 1990; diluted 1 : 500) overnight at 4°C. The antibodies were obtained from Dr J. Sutko, University of Nevada, Reno, NE, U.S.A. or from Affinity Bioreagents, Inc (Golden, CO, U.S.A.). An anti-mouse antibody conjugate to HRP was used as second antibody together with an anti-biotin antibody for visualizing a biotinylated molecular weight marker, and detected with chemiluminescence (West Pico Supersignal, Pierce).

Calcium measurements

[Ca2+]i was estimated ratiometrically by the use of fura-2 in an imaging system (IonOptix Corp., MA, U.S.A.) which was mounted on a Nikon TMD inverted microscope with a Nikon Fluor 20×objective. For simultaneous measurements on two preparations, arterial rings were inverted and mounted on a thin glass capillary (35 μm outer diameter). Thus the de-endothelialized intima and muscular media will face the perfusing solution and the objective of the microscope, which facilitates fluid exchange and minimizes the contribution of adventitial fibroblasts to the Ca2+ signal. Rings were incubated for 90 min at room temperature with 13.3 μM of fura-2-AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.), 3% DMSO and 0.067% pluronic F-127. The capillary with the rings was mounted in the chamber with perfusion at room temperature. Zones that averaged 0.04 mm2 were defined over each of the two rings and the measurements were carried out at a sampling frequency of 2 Hz.

For detection of spontaneous cellular Ca2+ events, rings were mounted as described above and loaded with fluo-4-AM (10 μM; Molecular Probes), 0.05% pluronic F-127 and 2% DMSO for 80 min. A Zeiss LSM 510 laser scanning confocal microscope was used. Exciting light at 488 nm was from a krypton/argon laser, and emitted light >505 nm was recorded through a 63×oil immersion lens (Zeiss, N.A.=1.25). For detection of Ca2+ waves, images were obtained every 0.2 second and wave propagation was evaluated with the Zeiss LSM 510 software. For sparks a single line, 25 – 65 μm long, was defined close to the plasma membrane, and scanned every 3 ms, for up to 30 s.

Statistics

Summarized data are expressed as means±s.e.mean. Student's t-test was used to evaluate statistical significance. Paired tests were used only when comparisons were made within the same preparation (e.g. before and after addition of inhibitors). For double comparisons an ANOVA analysis was performed. * or Φ denote P<0.05, ** or ΦΦ P<0.01 and *** or ΦΦΦ P<0.001.

Results

Long term effects of ryanodine and Ca2+ pump inhibitors on basal [Ca2+]i and viability of rat tail artery in vitro

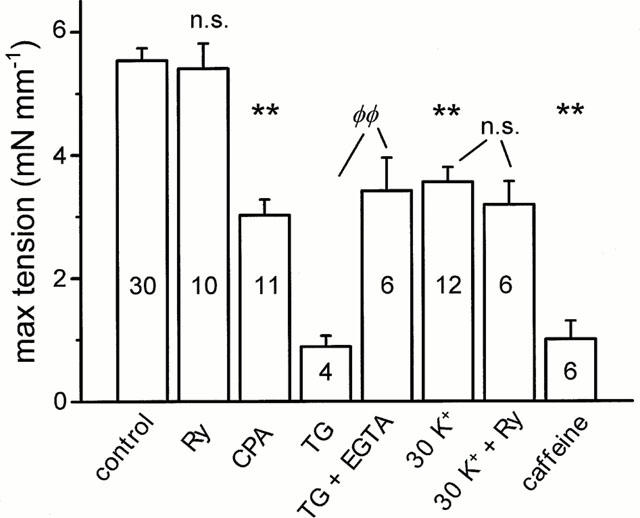

We have previously shown, using organ culture of rat tail artery, that chronic increase of basal [Ca2+]i decreases contractility due to Ca2+-induced cell damage (Lindqvist et al., 1997; 1999), and furthermore leads to a selective up-regulation of caffeine-sensitive Ca2+ stores (Dreja & Hellstrand, 1999). The increase in Ca2+ store capacity might be interpreted as an adaptive response, suggesting that the stores act to prevent increases in [Ca2+]i in situations of high Ca2+ load. To test this, we cultured tail artery rings with Ry (10 μM) in normal or depolarizing medium (30 mM K+, 2.5 mM Ca2+). Surprisingly, under none of these culture conditions does Ry affect the maximal force output (Figure 1). Depleting Ca2+ stores during culture using caffeine (5 mM), or the Ca2+ pump inhibitors cyclopiazonic acid (CPA, 10 μM) or thapsigargin (TG, 10 μM), on the other hand, diminished contractility. TG had the greatest effect, and force after 4 days was nearly zero. Therefore these preparations were examined already after 2 days of culture. The negative effect of TG on contractility could be partially prevented by including EGTA (0.88 mM) in the culture medium, lowering [Ca2+]ec from ∼1.08 to ∼0.2 mM. This indicates that an increased basal [Ca2+]i is responsible for the decline in force, and that accumulation of Ca2+ into the SR is essential for cell viability.

Figure 1.

Effects of culture conditions on maximal tension of tail arterial rings. Contraction was induced by high-K++10 μM NA. Rings were cultured in normal medium (control), medium supplemented with ryanodine (Ry, 10 μM), cyclopiazonic acid (CPA, 10 μM), thapsigargin (TG, 10 μM), EGTA (0.88 mM), caffeine (5 mM), or in partially depolarizing high-Ca2+ medium (30 K) containing 30 mM K+ and 2.5 mM Ca2+. Culture time 4 days except with TG (2 days). n values are shown within bars. **Significantly different from control cultured rings, each condition (Ry, CPA, TG, or 30 K) compared with individual controls. n.s.=not significant. Control column shows pooled mean±s.e.mean of all control preparations. ΦΦSignificant difference between TG and TG+EGTA treated rings.

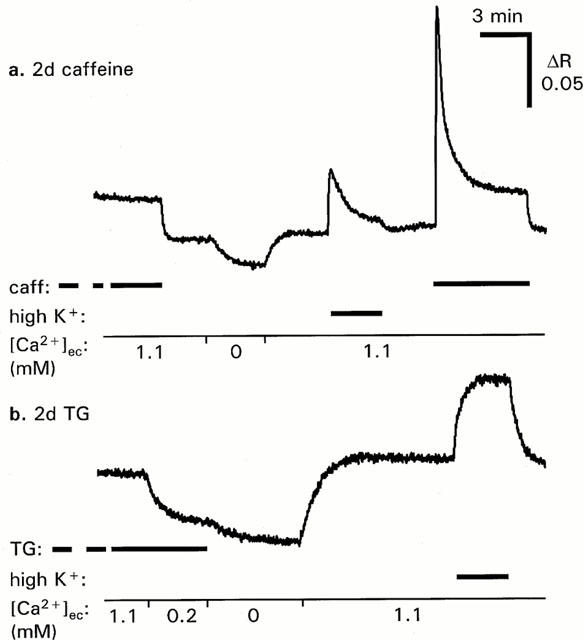

Ratiometric measurements after 2 days of culture verified that both caffeine and TG induced large, persistent increases in cytosolic [Ca2+]i (Figure 2). Whereas the effect of caffeine was reversible, TG induced a high sustained plateau in [Ca2+]i that was retained after withdrawal of the drug, and that could be lowered by EGTA (0.88 mM). In rings treated with Ry for 4 days there was no significant change in resting [Ca2+]i. Basal [Ca2+]i was estimated from the decline in fura-2 (340/380 nm) ratio after transition from normal to Ca2+-free (1 mM EGTA) solution, and expressed relative to the increase in ratio during high-K+ stimulation. The basal [Ca2+]i was 9.8±2.7% (n=9) and 6.4±1.8% (n=10) for Ry-treated and cultured controls, respectively.

Figure 2.

Effects of extracellular [Ca2+] on [Ca2+]i in arterial rings treated for 2 days with caffeine or thapsigargin. Rings were mounted, equilibrated and loaded with fura-2-AM in the continuous presence of caffeine (caff, 5 mM, upper panel), or thapsigargin (TG, 10 μM, lower panel). Medium contained 1.1 mM Ca2+ to mimic culture medium. Addition of 0.88 mM EGTA lowered [Ca2+] to ∼0.2 mM. Ca2+-free medium (0 mM) contained 1 mM EGTA and no added Ca2+. n=3 for both.

Ca2+ stores remain intact after chronic ryanodine treatment

The state of the SR after 4 days of culture was evaluated by inducing Ca2+ release through Ry or IP3 receptors by caffeine and noradrenaline (NA), respectively. Rings were contracted in 140 mM K+ for 5 min to allow a nearly complete filling of Ca2+ stores. Releasing agents were applied after relaxation for 5 min in Ca2+-free solution containing 1 mM EGTA. Force transients were recorded and, as expected, caffeine responses were lost after Ry treatment. However, NA responses were maintained (Figures 3 and 5), which is in sharp contrast to what is found after acute exposure to Ry, which invariably abolishes responses to both NA and caffeine (Figure 3). Culture with caffeine did not mimic the effects of Ry. When mounted and equilibrated in the continuous presence of caffeine these rings did not show any Ca2+ release response to NA. Release responses to NA as well as to caffeine returned after withdrawal of caffeine (not shown).

Figure 3.

Ca2+ release responses with time in culture. Responses to NA (10 μM) and caffeine (20 mM) were induced in 0 Ca2+, 1 mM EGTA solution after loading of SR with Ca2+ in high-K+ medium. Tension transients expressed relative to maximal tension induced by NA (10 μM) in high K+ solution. Ryanodine (10 or 100 μM), C10-Oeq glycyl ryanodine (10 μM) or vehicle was added to culture medium (n=6 for all).

Figure 5.

Spontaneous Ca2+ events in cells of cultured rings. (a) Confocal line scan image from cultured control ring. Fluo-4 fluorescence along the scanned line (ordinate) is displayed against time (abscissa). The intensity was averaged from the region indicated by the bar (right of image) and plotted in lower panel. (b) Ca2+ wave detected in one Ry-cultured cell. The graph in the lower panel shows fluorescence intensity averaged from the three zones indicated in images in the upper panel. The wave peak moved from zone 1 to zone 2 at 20.8 μm s−1, and from zone 2 to zone 3 at 20.6 μm s−1.

The time course of recovery of the NA responses during culture was studied in the tail arteries (Figure 3). After 24 h of culture with Ry the responses were 74% of those in cultured controls, but were not completely restored until the fourth day. The recovery of NA-induced Ca2+ release during culture with Ry demonstrates that the capacity of the SR to hold Ca2+ has been restored. A potential mechanism for this could be a transition of Ry receptors from an open to a closed state. To test this, the same experiment was also performed with 100 μM Ry and with the analogue C10-Oeq glycyl ryanodine (10 μM). Ry and C10-Oeq glycyl ryanodine have the same affinity for the Ry receptor, but in contrast to Ry, which is known to induce deactivation of Ry receptors at higher concentrations (>10 μM), C10-Oeq glycyl ryanodine does not cause deactivation (Humerickhouse et al., 1994). The time course of recovery of NA responses using these agents was however the same as with the low Ry concentration.

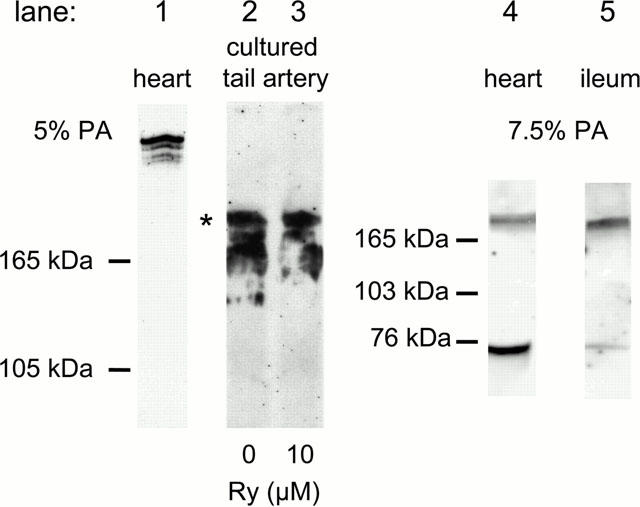

Immunodetection of ryanodine receptors

One approach for detecting the presence of Ry receptors would be binding studies using radiolabelled Ry. However low specific binding was found in pilot experiments using bladder and aortic smooth muscle, which could be prepared in much larger quantities than the cultured tail arterial segments (data not shown). Since the interpretation of this experiment is also complicated by the previous exposure to Ry, we decided to use immunodetection.

Western blots on microsomal membrane fractions from the heart (Figure 4, lane 1) revealed a doublet band in the expected molecular weight range for Ry receptors (∼400 kDa; Coronado et al., 1994). In cultured tail artery, immunoreactivity at about 240 kDa was evident, with a similar pattern in arteries cultured both in the absence and presence of Ry (Figure 4, lanes 2 and 3). This probably represents a degradation product, as similar bands were seen in some cardiac preparations and in membrane fractions from ileum longitudinal smooth muscle, which also revealed a low molecular weight component at ∼80 kDa, retained on 7.5% but not on 5% polyacrylamide gels (Figure 4, lanes 4 and 5). The blots shown in Figure 4 were obtained using the antibody clone 34C (see Methods). Similar degradation products were seen also using another antibody (110E), which has been shown to label cardiac and ileum Ry receptors (Lesh et al., 1998).

Figure 4.

Immunoblot of Ry receptors in smooth muscle. Proteins from microsomal membrane fractions were separated by SDS – PAGE on 5 or 7.5% polyacrylamide (PA) gels. Anti-Ry receptor antibody (34C) binding was detected with chemiluminescence. Lane 1: Normal heart preparation showing a doublet high molecular weight band. Lanes 2 – 5: In some heart and in all smooth muscle preparations degradation occurred. * ≈240 kDa.

Spontaneous Ca2+ release events

A distinct phenomenon ascribed to the activation of Ry receptors is the appearance of brief spontaneous Ca2+ release events (‘sparks'; Cheng et al., 1993; Nelson et al., 1995). Spark activity was recorded from cells within the intact arterial wall. In fresh arteries six out of 38 cells tested exhibited sparks in normal solution, whereas sparks were rarely seen under these conditions in cultured rings (one of 48 cells). Spark frequency could be increased by depolarization with 30 mM K+, during which sparks were evident in 12 out of 63 cells in cultured control rings (Figure 5a), whereas in Ry-cultured rings, none of the 71 cells tested showed spark activity. In cells that exhibited sparks, the events were repetitive but irregular (mean frequency 0.65±0.17 Hz). The observed sparks had a mean rise time (from start to peak) of 20.4±2.3 ms, and half time of decline that was 50.9±5.4 ms. This is very similar to values obtained by others in vascular cells (Nelson et al., 1995). Line scan detection monitors only a small fraction of the cell volume, and sparks are only detected when the selected line is located close to the plasma membrane. These are factors that might decrease the number of cells identified to show spark activity.

Ca2+ waves are slower events, with a high amplitude, that involve most of the cell cytosol. Waves could be observed in both fresh and cultured preparations after stimulation with NA (10−7.5 – 10−6 M). Incubation with caffeine (20 mM, 3 min), and thereafter TG (10 μM, 10 min), before application of NA completely abolished wave activity in both fresh and cultured rings (n=4 for both). In fresh rings waves were very frequent, often coalescing within a cell. Therefore caution was taken that the waves evaluated were initiated at a point beyond the two zones, and that not more than one wave occurred at the same time. Waves occurred in both Ry-cultured and cultured control rings and to examine if Ry receptors contribute to wave propagation, the velocity of waves was calculated from the delay in [Ca2+] rise between zones at different points within individual cells (Figure 5b). Wave propagation was not significantly altered by culture, and Ry-cultured rings did not differ from cultured controls. It is therefore evident that IP3 mediated Ca2+ release is sufficient for wave initiation and propagation in this preparation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Propagation velocity of Ca2+ waves in freshly dissected and in cultured tail arterial smooth muscle

Ca2+ transport

To study if Ca2+ transport processes are affected by loss of Ry receptors, [Ca2+]i measurements were performed using fura-2 as an indicator. Measurements were done simultaneously from a Ry treated and a control ring mounted side by side on a glass capillary. This allowed comparison of responses under identical conditions. During relaxation in Ca2+-free medium from a high-K+ contraction, [Ca2+]i decline was much slower in Ry-treated rings (Figure 6, and Table 2). Removal of cytosolic Ca2+ depends on uptake to internal Ca2+ stores as well as on extrusion of Ca2+ across the plasma membrane. After blocking uptake of Ca2+ to the SR with TG (10 μM, 10 min), the decline in [Ca2+]i after the high-K+ contraction was delayed in the control rings to be similar to that in Ry-treated rings. There was no effect of TG on rate of Ca2+ removal in Ry-treated rings. These data indicate that the slow rate of Ca2+ removal in Ry treated muscle is due to inability of the SR to accumulate Ca2+, and that extrusion by plasma membrane Ca2+ transporters (Ca2+ ATPases and/or Na+/Ca2+ exchangers) is not affected by Ry culture. This is also illustrated by the fact that the rate of [Ca2+]i decline after NA-induced Ca2+ release was identical in Ry-cultured and control rings (Table 2). In the continuous presence of NA, as in this experiment, there should be no net accumulation into the SR, and the removal of Ca2+ from the cytosol is thus mainly dependent on extrusion over the plasma membrane.

Figure 6.

Decay of [Ca2+]i during recovery from high-K+ depolarization in control and Ry-cultured arterial rings. (a) Original records from rings mounted in parallel and imaged simultaneously. During exposure to thapsigargin (TG, 10 μM) the recording was arrested. (b) Decline in [Ca2+]i after transition from high-K+ to normal K+, 0 Ca2+, 1 mM EGTA solution, before and after TG treatment. Summarized data are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Time constants of ratiometric [Ca2+]i decrease during relaxation from high-K+ (K) and noradrenaline (NA) induced contractions. Effect of treatment with thapsigargin (TG)

Kinetics of Ca2+ release and uptake by the SR

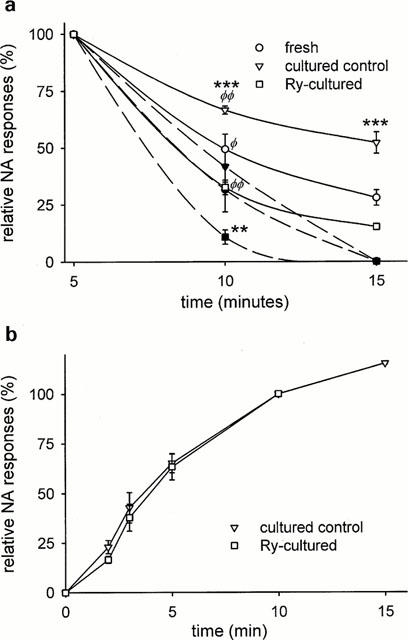

To examine the alteration in SR function occurring after Ry-culture, we studied the emptying and refilling of the SR in more detail. The rate of loss of Ca2+ from the SR after loading in high-K+ solution was assessed by the time course of decline of NA (10 μM) responses in Ca2+-free medium. As shown in Figure 7a, stored Ca2+ was lost much more rapidly in Ry treated than in cultured control rings. SR Ca2+ loss was accelerated in all rings when CPA was added at t=5 min. However, Ry-treated rings still eliminated Ca2+ more rapidly after CPA. These findings show that Ca2+ stores are more leaky after Ry-culture. The increase in rate after CPA treatment also gives an estimate of the fraction of basal released Ca2+ that is not extruded from the cell, but taken up again to the SR. In fresh preparations this fraction was 27±7% (n=5).

Figure 7.

Time course of washout and refilling of intracellular Ca2+ stores. (a) Force transients were induced by NA (10 μM) after 5, 10 or 15 min in Ca2+-free (1 mM EGTA) solution following loading of SR with Ca2+ in high-K+ solution. Responses at 5 min set to 100%. CPA (10 μM; filled symbols), when used, was added at 5 min. **,***Significant difference between Ry-cultured and cultured control rings, with or without CPA. Φ,ΦΦSignificant difference between CPA-treated and non-treated rings. (b) Rate of SR refilling as estimated by amplitude of NA responses vs time in 60 mM K+, 0.1 mM Ca2+. n=9 for all.

These experiments show that the SR can retain Ca2+ over much longer time periods (10 – 15 min, Figure 7) than needed for cytosolic [Ca2+] to return to baseline values (0.5 – 1 min, Figure 6 and Table 2) during washout in Ca2+-free medium. This was the case even in Ry-cultured rings, despite the increased rate of store depletion in these.

The ability of the SR to accumulate Ca2+ was determined under depolarized conditions (60 mM K+), to facilitate Ca2+ influx over the plasma membrane. The sensitivity to extracellular Ca2+ was not affected by Ry culture. EC50 values of Ca2+-induced tension for Ry treated and control rings were 0.73±0.04 and 0.69±0.04 mM [Ca2+]ec respectively (n=8 for both). During the refill experiment [Ca2+]ec was kept at 0.1 mM, which induces a low level of tension that is still well above baseline. After variable time periods in this solution, rings were returned to Ca2+-free (0.2 mM EGTA) solution, and 3 min later NA (10 μM) was applied. After the NA-induced force transient, NA was washed out and the ring kept for 5 min in Ca2+-free medium followed by 2 min in depolarizing (60 mM K+) solution, both containing 0.2 mM EGTA. Following this Ca2+ depletion the protocol was repeated with another time period for reloading in 0.1 mM Ca2+. The rate of Ca2+ store reloading was identical in Ry-cultured and in cultured control rings (Figure 7b).

Discussion

This study demonstrates a qualitative difference between the effects of acute and chronic Ry treatment in vascular smooth muscle. On acute application, Ry binds to its receptor and locks it in an open state, which empties Ca2+ stores and thereby abolishes Ca2+ release responses to other agents acting on these stores, such as NA. The ability of Ry and caffeine to acutely deplete IP3-releasable Ca2+ stores demonstrates that IP3-receptors are located to stores also containing Ry receptors. During chronic treatment with Ry, Ca2+ stores gradually refill, and after 4 days responses to NA are completely restored, whereas caffeine responses remain lost. In contrast to the results using Ry, culture with caffeine did not restore NA-induced Ca2+ release.

The restoration of the capacity for Ca2+ storage by the SR during Ry culture does not seem to result from a loss of receptor protein, since Ry receptors were retained as shown by Western blotting. The molecular weight of the obtained immunoreactive bands in smooth muscle was lower than the reported weight of skeletal and cardiac Ry receptors, as also demonstrated here with cardiac muscle using the same antibody. However, protein degradation is likely during the extensive procedures to obtain membrane preparations needed for detection of Ry receptors, which are present in very low concentration in vascular preparations (Zhang et al., 1993; Lesh et al. 1998). These procedures involved also culture of arterial segments from a large number of rats, which necessitated pooling of frozen samples. With this caveat, there was no difference in the pattern of Ry receptor protein between identically treated samples from Ry cultured and control preparations.

Deactivation of Ry receptors does not seem to be responsible for the loss of function, since the time course of the recovery of NA responses was the same with the Ry analogue C10-Oeq glycyl ryanodine and with a high concentration of Ry (100 μM). Deactivated receptors are modulated into a subconducting state with a lower conductance than the fully opened channel. This occurs at high concentrations of Ry, but not with C10-Oeq glycyl ryanodine (Humerickhouse et al., 1994). Another potential explanation would be an emerging compartmentation of Ry- and IP3- sensitive stores. This cannot be excluded on the basis of the present experiments, since any Ry-sensitive stores remaining after Ry culture would be refractive to activation by caffeine due to the irreversible binding of Ry to its receptor.

Although the molecular mechanism behind the Ry receptor dysfunction is not known at present, the ability to selectively abolish all Ry receptor responses while IP3-releasable stores are intact, opens interesting possibilities for investigating the functional role of Ry receptors with respect to Ca2+ homeostasis and activation of Ca2+-dependent cellular responses, as shown by results obtained in this study.

Many studies have reported that Ry acutely abolishes Ca2+ spark activity. We show that sparks are lost after Ry treatment, even when the SR is able to refill with Ca2+ and the IP3 receptor is functional. Thus spark activity is dependent on functional Ry receptors. Ry and caffeine have also been shown to retard or abolish Ca2+ waves in arterial smooth muscle (Blatter & Wier, 1992; Iino et al., 1994). This might be expected even if waves are only dependent on IP3-sensitive release, since IP3 sensitive stores may be empty after acute Ry treatment. However, Ca2+ waves were present in chronically Ry-treated arterial rings, and no difference in propagation velocity compared with control rings was detected. Thus, IP3 receptors are sufficient for initiation as well as propagation of Ca2+ waves.

The preparations lacking functional Ry receptors showed no obvious abnormalities with respect to contractility, sensitivity to Ca2+ influx, or uptake of Ca2+ to the SR. The TG-sensitive component of Ca2+ removal from the cytosol during washout following loading of the SR was however absent after culture with Ry. Since SR Ca2+ ATPase activity does not seem to be decreased after culture with Ry, these results are difficult to explain. The greater rate of loss of stored Ca2+ by passive leakage in Ry-treated rings could in principle short-circuit SR uptake, producing a similar net effect as TG. However, the rate of passive leakage out of the SR in Ry cultured rings is ∼1/5 of the rate of Ca2+ removal from the cytosol, and even though this is more than in control rings, the leakage should be slow enough not to produce an appreciable loss of stored Ca2+ during a washout process lasting less than a minute.

In striated muscle the Ry receptor is known to bind to proteins within the SR, in the cytosol, and also in the plasma membrane. It thus forms a structural scaffold that could be very important for interactions between membranes and for normal Ca2+ handling (Coronado et al., 1994). In smooth muscle it has been suggested that the SR might facilitate transport of Ca2+ out of the cell, by directing cytosolic Ca2+ towards the plasma membrane and its Ca2+ transporters (Nazer & van Breemen, 1998). Otherwise the SR will be expected to remain saturated with Ca2+ and not able to contribute to Ca2+ transport from the cytosol during relaxation from a high-K+ contraction. However, the participation of Ry receptors in such a process does not seem to be an absolute prerequisite for net Ca2+ extrusion, at least under basal conditions, as the SR of Ry-treated rings appears quite capable of controlling basal [Ca2+]i at its normal level.

Fresh rings appeared to lose Ca2+ stored in the SR faster than cultured rings. This might relate to the fact that cultured preparations are functionally denervated (Todd & Friedman, 1978), which might cause decreased basal IP3 production due to loss of sympathetic tone, thereby lowering the rate of basal Ca2+ release from the SR.

Culture in the presence of Ca2+ pump inhibitors or caffeine greatly impaired contractility. In contrast to chronic Ry treatment, these agents will render Ca2+ stores incapable of accumulating Ca2+, and they were shown to dramatically increase basal [Ca2+]i. The damaging effect of TG could be prevented by lowering the [Ca2+] of the culture medium with EGTA. In conjunction with studies describing the detrimental effect of Ca2+ overload in this preparation (Lindqvist et al., 1997; 1999; Dreja & Hellstrand, 1999) it seems reasonable to conclude that the SR contributes to the control of basal [Ca2+]i and thereby to the prevention of vascular injury. The mechanism of this effect may involve either uptake of Ca2+ or control of Ca2+ influx by the level of SR filling (Parekh & Prenner, 1997). The present results indicate that Ca2+ homeostasis and long-term viability are dependent on storage of Ca2+ in the SR, but does not implicate a critical role of Ry receptors for these functions.

This study demonstrates a novel approach for eliminating Ry receptor function while IP3 receptor activity and SR Ca2+ accumulation are retained. This selective pharmacological Ry receptor knockout eliminates Ca2+ sparks, but not Ca2+ waves, and has little effect on general Ca2+ homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Henry R. Besch, Jr., and Keshore R. Bidasee for valuable discussions and the gift of C10-Oeq glycyl ryanodine, and Dr John Sutko for advice on detection of ryanodine receptors and gift of antibodies. The study was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council (project 04X-28).

Abbreviations

- CPA

cyclopiazonic acid

- NA

noradrenaline

- Ry

ryanodine

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- TG

thapsigargin

References

- ABE F., KARAKI H., ENDOH M. Effects of cyclopiazonic acid and ryanodine on cytosolic calcium and contraction in vascular smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:1711–1716. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AIREY J.A., BECK C.F., MURAKAMI K., TANKSLEY S.J., DEERINCK T.J., ELLISMAN M.H., SUTKO J.L. Identification and localization of two triad junctional foot protein isoforms in mature avian fast twitch skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:14187–14194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARONE V., BERTOCCHINI F., BOTTINELLI R., PROTASI F., ALLEN P.D., FRANZINI-ARMSTRONG C., REGGIANI C., SORRENTINO V. Contractile impairment and structural alterations of skeletal muscles from knockout mice lacking type 1 and type 3 ryanodine receptors. FEBS Lett. 1998;422:160–164. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENHAM C.D., BOLTON T.B., LANG R.J., TAKEWAKI T. The mechanism of action of Ba2+ and TEA on single Ca2+-activated K+-channels in arterial and intestinal smooth muscle cell membranes. Pflügers Arch. 1985;403:120–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00584088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIDASEE K.R., BESCH H.R., JR, GERZON K., HUMERICKHOUSE R.A. Activation and deactivation of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release channels: molecular dissection of mechanisms via novel semi-synthetic ryanoids. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1995;149/150:145–160. doi: 10.1007/BF01076573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLATTER J.A., WIER W.G. Agonist-induced [Ca2+]i waves and Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in mammalian vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:H576–H586. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.2.H576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOITTIN F.X., COUSSIN F., MACREZ N., HALET G., MIRONNEAU J. Norepinephrine-induced Ca2+ waves depend on InsP3 and ryanodine receptor activation in vascular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:C139–C151. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.1.C139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Q., VAN BREEMEN C.Function of smooth muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Advances in Second Messenger and Phosphoprotein Research 199226New York: Raven; 335–350.ed. Putney Jr., J.W. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG H., LEDERER W.J., CANNELL M.B. Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science. 1993;262:740–744. doi: 10.1126/science.8235594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORONADO R., MORRISSETTE J., SUKHAREVA M., VAUGHAN D.M. Structure and function of ryanodine receptors. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:C1485–C1504. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.6.C1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COUSSIN F., MACREZ N., MOREL J.L., MIRONNEAU J. Requirement of ryanodine receptor subtypes 1 and 2 for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in vascular myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:9596–9603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROMPTON M., KESSAR P., AL NASSER I. The alpha-adrenergic mediated activation of cardiac mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter and its role in the control of intramitochondrial Ca2+ in vivo. Biochem. J. 1983;216:333–342. doi: 10.1042/bj2160333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DREJA K., HELLSTRAND P. Differential modulation of caffeine- and IP3-induced calcium release in cultured arterial tissue. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:C1115–C1120. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.5.C1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIROSE K., KADOWAKI S., TANABE M., TAKESHIMA H., IINO M. Spatiotemporal dynamics of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate that underlies complex Ca2+ mobilization patterns. Science. 1999;284:1527–1530. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUMERICKHOUSE R.A., BIDASEE K.R., GERZON K., EMMICK J.T., KWON S., SUTKO J.L., RUEST L., BESCH H.R., JR High affinity C10-Oeq ester derivatives of ryanodine. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:30243–30253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IINO M., KASAI M., YAMAZAWA T. Visualization of neural control of intracellular Ca2+ concentration in single vascular smooth muscle cells in situ. EMBO J. 1994;13:5026–5031. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06831.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOBAYASHI S., KANAIDE H., NAKAMURA M. Complete overlap of caffeine and K+ depolarization-sensitive intracellular calcium storage site in cultured rat arterial smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:15709–15713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOMORI S., ITAGAKI M., UNNO T., OHASHI H. Caffeine and carbachol act on common Ca2+ stores to release Ca2+ in guinea-pig ileal smooth muscle. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;277:173–180. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00072-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE H.C. Potentiaton of calcium- and caffeine-induced calcium release by cyclic ADP-ribose. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LESH R.E., NIXON G.F., FLEISCHER S., AIREY J.A., SOMLYO A.P., SOMLYO A.V. Localization of ryanodine receptors in smooth muscle. Circ. Res. 1998;82:175–185. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDQVIST A., NILSSON B.O., HELLSTRAND P. Inhibition of calcium entry preserves contractility of arterial smooth muscle in culture. J. Vasc. Res. 1997;34:103–108. doi: 10.1159/000159207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDQVIST A., NORDSTRÖM I., MALMQVIST U., NORDENFELT P., HELLSTRAND P. Long-term effects of Ca2+ on structure and contractility of vascular smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:C64–C73. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.1.C64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEISSNER G. Ryanodine activation and inhibition of the Ca2+ release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:6300–6306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEISSNER G., DARLING E., EVELETH J. Kinetics of rapid Ca2+ release by sarcoplasmic reticulum: effects of Ca2+, Mg2+, and adenine nucleotides. Biochemistry. 1986;25:236–244. doi: 10.1021/bi00349a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAZER M.A., VAN BREEMEN C. A role for the sarcoplasmic reticulum in Ca2+ extrusion from rabbit inferior vena cava smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:H123–H131. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.1.H123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELSON M.T., CHENG H., RUBART M., SANTANA L.F., BONEV A.D., KNOT H.J., LEDERER W.J. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science. 1995;270:633–637. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAREKH A.B., PENNER R. Store depletion and calcium influx. Physiol. Rev. 1997;77:901–930. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROUSSEAU E., SMITH J.S., MEISSNER G. Ryanodine modifies conductance and gating behaviour of single Ca2+ release channel. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;253:C364–C368. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.3.C364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAIDA K., VAN BREEMEN C. Characteristics of the noradrenaline-sensitive Ca2+ store in vascular smooth muscle. Blood Vessels. 1984;21:43–52. doi: 10.1159/000158493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STREB H., HESLOP J.P., IRVINE R.F., SCHULZ I., BERRIDGE M.J. Relationship between secretagogue-induced Ca2+ release and inositol polyphosphate production in permeabilized pancreatic acinar cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:7309–7315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKESHIMA H., IKEMOTO T., NISHI M., NISHIYAMA N., SHIMUTA M., SUGITANI Y., KUNO J., SAITO I., SAITO H., ENDO M., IINO M., NODA T. Generation and characterization of mutant mice lacking ryanodine receptor type 3. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:19649–19652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TODD M.E., FRIEDMAN S.M. The rat-tail artery maintained in culture: an experimental model. In Vitro. 1978;14:757–770. doi: 10.1007/BF02617969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG Z.D., KWAN C.Y., DANIEL E.E. Subcellular-membrane characterization of [3H]-ryanodine-binding sites in smooth muscle. Biochem. J. 1993;290:259–266. doi: 10.1042/bj2900259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]