Abstract

Electrophysiological recordings have been used to characterize responses mediated by AMPA receptors expressed by cultured rat cortical and spinal cord neurones. The EC50 values for AMPA were 17 and 11 μM, respectively.

Responses of cortical neurones to AMPA were inhibited competitively by NBQX (pKi=6.6). Lower concentrations of NBQX (⩽1 μM) also potentiated the plateau responses of spinal cord neurones to AMPA, which could be attributed to a depression of desensitization to AMPA.

GYKI 52466 inhibited responses of spinal cord neurones to AMPA to about twice the extent of responses of cortical neurones.

Blockade of AMPA receptor desensitization by cyclothiazide (CTZ) potentiated responses of spinal cord neurones (6.8 fold) significantly more than responses of cortical neurones (4.8 fold). Responses of cortical neurones to KA were potentiated 3.5 fold by CTZ, while responses of spinal cord neurones were unaffected.

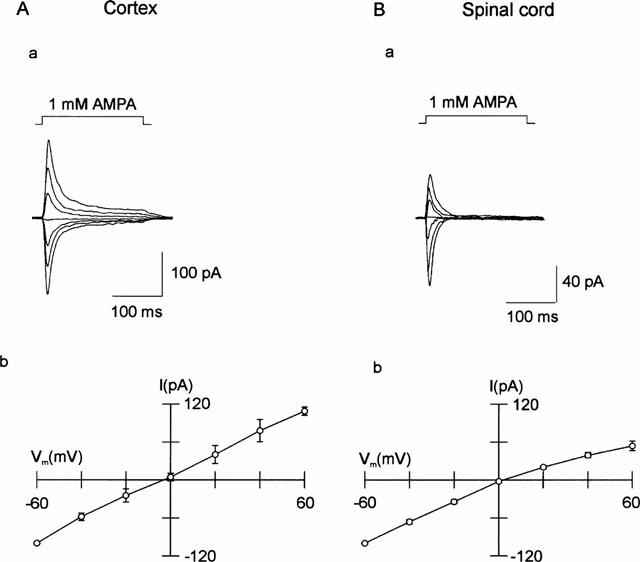

Ultra-fast applications of AMPA to outside-out patches showed responses of spinal cord neurones desensitized by 97.5% and exhibit marked inward rectification, whereas cortical neurones desensitized by 91% and exhibited slight outward rectification. The time constants of deactivation and desensitization were about twice as fast in spinal cord than cortical neurones.

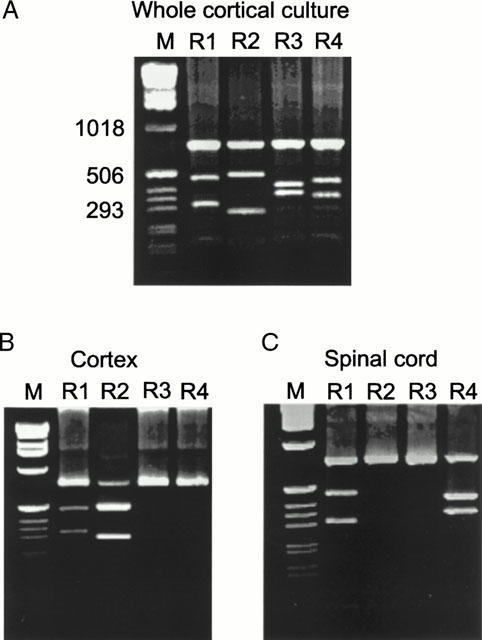

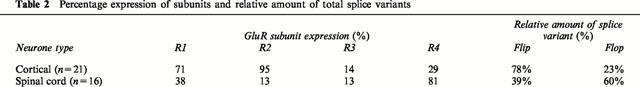

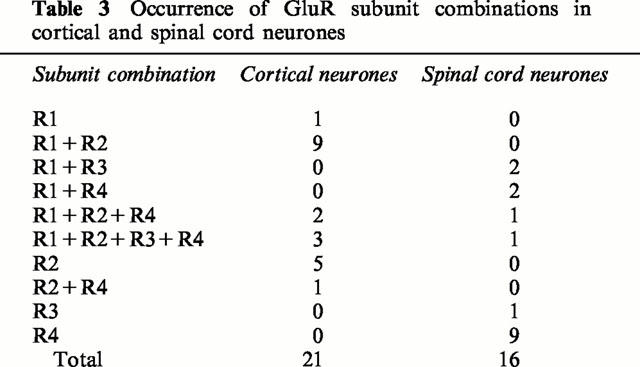

In cortical neurones, single-cell RT – PCR showed GluR2 and GluR1 accounted for 91% of all subunits and were expressed together in 67% of neurones, predominantly as the flip variants (78%). GluR2 was detected alone in 24% of neurones. GluR3 and GluR4 were present in only 14 and 29% of neurones, respectively. For spinal cord neurones, GluR4o was detected in 81% of neurones, whereas predominantly flop versions of GluR1, 2 and 3 were detected in 38, 13 and 13% of neurones, respectively. These expression patterns are related to the respective pharmacological and mechanistic properties.

Keywords: AMPA, cortical neurones, cyclothiazide, desensitization, glutamate receptor, GYKI 52466, NBQX, single-cell RT – PCR, spinal cord neurones

Introduction

Ionotropic glutamate receptors mediate the vast majority of rapid synaptic excitatory transmission in the central nervous system. These receptors have been divided into subtypes according to their affinity for three reasonably selective agonists: N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), 2-amino-3-(3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolyl)propionate (AMPA) and kainate (KA) (Collingridge & Lester, 1989). Discriminating between these receptors and determining their role in synaptic transmission relies on a combination of pharmacological and mechanistic approaches. Actions at NMDA receptors are readily separated from their non-NMDA cousins: highly selective antagonists for NMDA receptors, such as 2-amino-5-phoshonovaleric acid (APV) and MK-801, have been known for many years (Collingridge & Lester, 1989), while the responses show distinctive slow kinetics and a characteristic voltage-dependency, which results from gating of the NMDA ionophore by Mg2+ ions (Collingridge & Lester, 1989). AMPA and KA receptors show much greater overlap, and it is only recently that strides have been made to discriminate unequivocally between actions mediated by these receptor subtypes (Dingledine et al., 1999). Such separation is important since it not only identifies synapses at which the respective receptors participate in excitatory transmission, but is likely to provide the rational basis for development of selective agonists and antagonists, which could possibly be beneficial in a variety of neurological disorders.

Several genes encoding for the glutamate receptors have been identified (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994). AMPA receptors are generated by a combinatorial assembly of glutamate receptor subunits GluR1 through GluR4 (Boulter et al., 1990; Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994), while KA receptors are assembled from two groups of subunits, GluR5-7 and KA1-2, which are categorized on the basis of their structural homology and affinity for [3H]-kainate (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994).

Recombinant AMPA receptors are preferentially activated by AMPA, which produces a characteristic desensitizing response (Burnashev, 1993; Fletcher & Lodge, 1996). AMPA receptors can also be gated by relatively large concentrations of KA (Boulter et al., 1990) which evokes non-desensitizing responses (Paternain et al., 1995; Fletcher & Lodge, 1996; Lerma, 1998). However, the action of KA on naturally expressed AMPA receptors has been shown to be associated with a very rapidly desensitizing component which can only be detected using a very rapid application system (Patneau et al., 1993). High concentrations of AMPA can also activate homomeric GluR5 receptors, or certain heteromeric combinations of KA receptors, composed of either GluR6 or GluR7 together with KA2 (Herb et al., 1992; Sakimura et al., 1992; Swanson et al., 1996; Schiffer et al., 1997).

Although quinoxalinediones, such as 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulphamoyl-benzo-(f)quinoxaline (NBQX), are potent competitive non-NMDA receptor antagonists, they discriminate only weakly between AMPA and KA receptors (Wilding & Huettner, 1996). On the other hand, 2,3 benzodiazepines such as 1-(4-aminophenyl)-4-methyl-7,8-methyl-endioxyl-5h-2,3-benzodiazepine (GYKI 52466), are relatively potent non-competitive antagonists which exhibit a 45 fold selectivity towards responses mediated by AMPA receptors compared with KA receptors (Tarnawa et al., 1989; Parsons et al., 1994; Wilding & Huettner, 1995; Rammes et al., 1996). Use of these substances has greatly increased progress towards addressing functional properties of AMPA receptor-mediated responses and their role in synaptic transmission. Furthermore, blockade of AMPA receptors allows KA receptor-mediated excitation to be studied in isolation (Chittajallu et al., 1999).

Another means of discriminating between AMPA and KA receptors is the use of agents which selectively block desensitization at the two receptors. Cyclothiazide (CTZ) blocks desensitization of AMPA receptors, while responses mediated by KA receptors are unaffected, or slightly depressed (Partin et al., 1993; Wilding & Huettner, 1995; Yamada & Turetsky, 1996). Studies on recombinant AMPA receptors have shown that CTZ reduces the desensitization of flip splice variants more than flop variants (Partin et al., 1993; 1994; Fleck et al., 1996). On the other hand, the plant lectin, concanavalin A preferentially blocks desensitization at KA receptors (Partin et al., 1993; Yue et al., 1995). Appropriate use of these blockers of desensitization has been useful to discriminate between actions at AMPA and KA receptors.

AMPA receptors are distributed throughout the central nervous system (CNS), where they show regional differences according to their composition (Sommer et al., 1990). A number of studies have shown that the subunit composition, alternative splice variants and post-transcriptional RNA editing are all very important for regulating the functional diversity of non-NMDA receptors (Hollmann et al., 1991; Verdoorn et al., 1991). For example, AMPA receptors containing the GluR2 subunit are relatively impermeable to Ca2+ ions and show either linear or outwardly rectifying current-voltage (I-V) relationships, whereas receptors which do not contain GluR2 have a high permeability to Ca2+ and show inwardly rectifying I-V relationships (Hollmann et al., 1991; Verdoorn et al., 1991; Jonas et al., 1994). Response kinetics and desensitization also depend on the subunit composition and splice variants. The presence of GluR4 has been shown to confer rapid desensitization to the assembled complex (Sommer et al., 1990; Mosbacher et al., 1994; Lomeli et al., 1994; Geiger et al., 1995), while flop splice variants show much faster response kinetics and a greater degree of desensitization than flip versions (Lambolez et al., 1996).

We have recently become interested in the physiological and pharmacological properties of non-NMDA receptors that are expressed on neurones cultured from various regions of the CNS (Dai et al., 1998b). It became apparent that there were a number of qualitative and quantitative differences between responses evoked on cortical and spinal cord neurones. To the best of our knowledge, no studies of the molecular determinants underlying these differences have been made. The aim of the present study was, therefore, to address the pharmacological and electrophysiological profiles of naturally expressed AMPA receptors on cultured cortical and spinal cord neurones and to relate these to the relative abundances of AMPA receptor subunits and their splice variants, which were determined by single-cell reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT – PCR) techniques (Lambolez et al., 1992; Jonas et al., 1994). Some of the results of the present study have been presented in abstract form (Dai et al., 1998a), while results from a parallel study on KA receptors are presently in preparation (Dai, Christensen, Egebjerg, Ebert and Lambert, 2001, unpublished results).

Methods

Cell culture

Cortical and spinal cord neurones were prepared from 15 – 18-day-old and 13 – 15-day-old embryos of Wistar rats respectively, using standard culturing techniques (Kristiansen et al., 1991). Neurones were cultured in 35 mm petri dishes (Nunclon) containing glass cover-slips (12 mm2), which had been coated with poly-D-lysine (5 mg ml−1). The plating medium contained Minimal Essential Medium with Earle's salts added and with L-alanyl-L-glutamine (Glutamax-1) instead of glutamine to which the following were added: 10% foetal calf serum (FCS), 10% heat-inactivated horse serum (HS), 50 IU ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin. Cultures were placed in an incubator at 37°C with a humidified gas mixture of 85% N2, 10% O2 and 5% CO2. One day after plating, the medium was completely exchanged with 2 ml feeding medium, which had the same composition as the plating medium, except that the FCS was omitted and the HS was reduced to 5%. When visual inspection showed a confluent background layer of cells (usually after 3 – 4 days), mitosis was inhibited with 5′-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (15 μg ml−1) plus uridine (35 μg ml−1) (FUdR). The feeding medium was replenished twice a week by exchanging 1 ml with fresh medium. All culturing media and chemicals were purchased from Gibco except FUdR, uridine and poly-D-lysine, which were purchased from Sigma.

Electrophysiological recording

Experiments were performed on neuronal cultures 7 – 14 days after plating. Electrophysiological recordings using conventional patch clamp techniques in whole-cell and outside-out modes were performed at room temperature (20 – 24°C). The recording chamber was perfused with artificial balanced salt solution (ABSS) at 0.5 – 1 ml min−1 containing (in mM): NaCl 140, KCl 3.5, Na2HPO4 1.25, MgSO4 2, CaCl2 2, glucose 10 and HEPES 10 (osmolarity 310 mosmol l−1, pH adjusted to 7.35 at 22°C using NaOH). Tetrodotoxin (0.2 μM) was added to the medium to block regenerative Na+ currents and synaptic potentials. Patch electrodes were prepared from borosilicate glass capillaries (1.2 mm o.d., Clark Electromedical Instruments, U.K.) using a P-87 electrode puller (Sutter Instruments, U.S.A.) and had a tip diameter of about 1 μm with tip resistances of 2 – 5 MΩ. The patch electrodes were filled with an artificial intracellular solution containing (mM): CsCl 120, MgCl2 3, EGTA 5, HEPES 10 (pH 7.2) (Lambolez et al., 1996). Currents were recorded using an EPC-7 patch-clamp amplifier (List) at a holding potential (Vh) of −60 mV. Signals were recorded using Axotape software (Axon instruments) at a sampling frequency of 167 Hz for responses evoked by semi-rapid application (see below) and 10 kHz for concentration jump experiments. The currents were also recorded on a digital-audio tape recorder (BioLogic model DTR-1200) for off-line analysis.

Compounds and their application

All compounds were prepared as 10 mM stock solutions dissolved in ABSS, except CTZ and AMPA, which were dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide and 50 mM NaOH respectively. The stock solutions were stored at −20°C and diluted on the morning of experiment. The compounds and their sources were: CTZ (purchased from Tocris Cookson); AMPA (a gift from Povl Krogsgaard-Larsen, Royal Danish School of Pharmacy); GYKI 52466 (a gift from Istvan Tarnawa, Budapest); NBQX (a gift from Novo Nordisk); KA (purchased from Sigma). For quantitative pharmacological investigations, all compounds were applied using a semi-rapid application system (DAD-12, Adams & List) composed of a 13 barrel array of fine quartz glass tubes connected to a common opening, which was positioned 100 – 200 μm from the soma of the recorded neurone. The total solution exchange time constant of this system was 30 – 50 ms. To investigate the kinetics of responses mediated by AMPA receptors, a piezo-electric device (Burleigh Instruments) was used to step a theta-glass application system (‘concentration-jump' technique) to apply compounds to excised outside-out membrane patches. The total solution exchange time was around 300 μs. Further details of both techniques are given in Banke & Lambert (1998) and Dai et al. (1998b). In most cases, the responses evoked by repetitive applications of agonists by either technique did not show significant rundown.

Data analysis

The membrane currents were recorded by Axotape and pClamp and analysed by pClamp software (Axon instruments) and Grafit (Erithacus Software Limited). All data are expressed as a percentage of control (mean±s.e.mean). Statistical analysis was performed using the two-tailed t-test with P<0.05 for significant difference.

Concentration-response curves were constructed by measuring responses evoked by increasing concentrations of agonist and fitting data from individual neurones by the Hill equation:

where I is the observed current, Imax is the maximum current, EC50 is the concentration which evoked a half maximal response and n is the Hill coefficient.

Single-cell RT – PCR

Only cells which had maintained giga-seal contact throughout the recording period were used for single-cell RT – PCR. Immediately after recording, the cytoplasm was aspirated into the patch pipette by applying negative pressure under visual control. The cytoplasm was immediately expelled into a 200 μl tube containing a reverse transcription solution (Lambolez et al., 1996). This contained random hexamer primers (5 μM, Boehringer Mannheim), dithiothreitol (10 mM, Gibco) and deoxyribonucleotides triphosphate (dNTP, 0.5 mM, Gibco) to which was added 20 u of ribonuclease inhibitor (Promega) and 100 u SuperScript™ II reverse transcriptase (Gibco) to give a final volume of 10 μl. This solution was incubated at 42°C for 1 h. The first strand cDNA samples were stored at −20°C until PCR amplification.

The cDNA was amplified by a nested PCR approach using primers that were designed to anneal with equal efficiency and competitively to the cDNA encoding the different AMPA receptor subunits. In the first amplification, a pair of sense and antisense primers which recognize all AMPA receptor subunits were employed. The sequences of these primers were: sense (P1): CCTTTGGCCTATGAGATCTGGATGTG; antisense (P2): TCGTACCACCATTTGTTTTTCA. The amplification solution contained 0.5 mM of each primer, 0.2 mM of each dNTP and 2.5 u Taq polymerase (Stratagene) in buffer in mM (Tris-HCl (pH 8.8) 10, KCl 50, MgCl2 1.5 and 0.001% w v−1 gelatine) to give a total volume of 100 μl. Amplification was performed using the following cycles: one cycle at 94°C for 3 min, 35 cycles at (94°C for 30 s → 56°C for 30 s → 72°C for 45 s) and one cycle at 72°C for 5 min. To exclude the effects of possible contamination, negative controls using extracellular solution were routinely performed in parallel, while the housekeeping gene, β-actin, was amplified in parallel to check for the efficiency of the PCR. Control PCR amplifications on mixtures containing different ratios of plasmids encoding the AMPA receptor subunits showed a linear amplification of the cDNA (data not shown). The second PCR amplification was performed under the same conditions using 1 μl of the first PCR reaction as template and a mixture of the two ‘upstream' primers, P3A (GCCTATGAGATCTGGATGTGCAT) and P3B (GCTTATGAAATCTGGATGTGCAT) and two ‘downstream' primers P4A (CACCATTTGTTTTTCAGCTTGT) and P4B (CACCATTTGTTCAATTTGT). The PCR-generated band of approximately 740 bp was electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel. Aliquots of the PCR reaction were digested with the following enzymes, which selectively cut the AMPA receptors into two fragments: BglI (Amersham) cuts GluR1 into 288 and 499 bp; Bsp12861 (New England) cuts GluR2 into 269 and 468 bp; Eco47III (Fermentas) cuts GluR3 into 345 and 398 bp; EcoRI (Amersham) cuts GluR4 into 332 and 405 bp. For quantification of the bands, the uncut 740 bp fragment was 5′-end-labelled with γ-32P-ATP (1 μCi per reaction) using 5 u of T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England) in buffer containing (mM): Tris-HCl at pH 7.6 70, MgCl2 10 and 1,4 dithiothreitol 5. The relative amount of each subunit transcript was determined by using phosphoimaging to quantify the radioactive intensity of each fragment following digestion with the aforementioned enzymes.

Specific subunit bands containing the flip/flop region were isolated after the digestion and subjected to a further PCR amplification using the ‘upstream' primer, P5 (TGGATTCCAAAGGCTA) and the downstream primers, P4A and P4B. This generated a 121 bp band, which was 5′-end-labelled with γ-32P-ATP. This was digested with StuI (New England), which only recognizes the flop versions of GluR2, R3 and R4 and generates fragments of 33 and 88 bp, and BsrI (New England), which only recognize the GluR1o and R2i versions and generates fragments of 53 and 68 bp. The relative amounts of these fragments were calculated from the amount of radioactivity in the digested and the undigested bands.

Results

Pharmacological properties of responses of cortical and spinal cord neurones

Response to AMPA

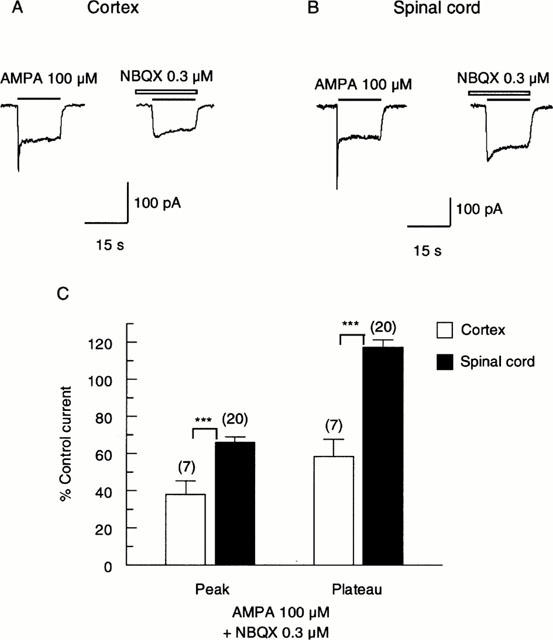

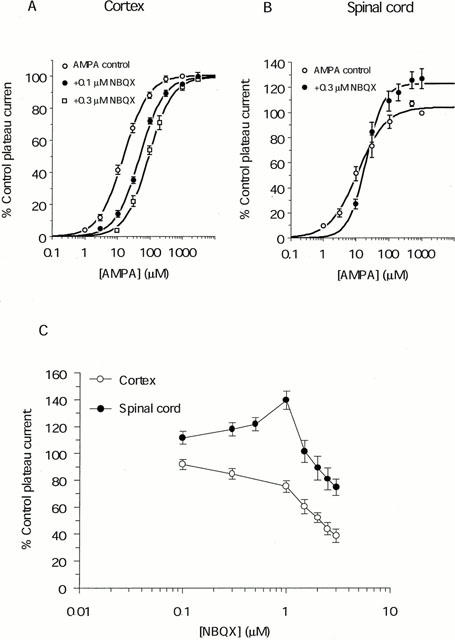

Responses of cultured cortical and spinal cord neurones to 100 μM AMPA are shown in Figure 1. AMPA evoked an inward current with rapid desensitization by 45±3% of the peak response in cortical neurones and 58±5% in spinal cord neurones. NBQX 0.3 μM markedly inhibited responses of cortical neurones to 100 μM AMPA, with a reduction in amplitude of the peak response by 62±7.5% (n=7; P<0.001) and of the steady state (plateau) response by 42±9.6% (n=7; P<0.001), respectively (Figure 1C). In spinal cord neurones, 0.3 μM NBQX reduced peak responses to AMPA by 34±3% (n=20; P<0.001). Interestingly, in the presence of NBQX, plateau responses of spinal cord neurones to AMPA were potentiated to 117±4% (n=20, P<0.001) of the control amplitude (Figure 1C). The effects of NBQX on both peak and plateau responses of cortical and spinal cord neurones to AMPA were significantly different (P<0.001). To analyse this further, we investigated the concentration-response relationships of plateau responses to AMPA (Figure 2A,B). EC50 values for AMPA were 11±1.4 μM (n=5) for spinal cord neurones and 17±1.3 μM (n=20) for cortical neurones, showing that the former have an apparently higher affinity for AMPA (P<0.05). The Hill coefficients (nH) were 1.2±0.11 for spinal cord neurones and 1.2±0.05 for cortical neurones. NBQX caused a parallel shift to the right of the concentration-response relationship of cortical neurones to AMPA, with an increase in EC50 for AMPA to 41±3.3 μM with 0.1 μM NBQX (n=12) and 83±9.0 μM with 0.3 μM NBQX (n=5, P<0.001; Figure 2A), corresponding a pKi value for NBQX of 6.6. nH values were not significantly different (1.2±0.07 (P<0.05) and 1.1±0.09 (P<0.05) with 0.1 and 0.3 μM NBQX, respectively. For spinal cord neurones, responses to AMPA evoked by concentrations ⩾30 μM were potentiated by 0.3 μM NBQX, giving rise to a steeper concentration-response relationship (Figure 2B) which crossed the control at around 20 μM AMPA. The apparent EC50 values were similar: 11±1.4 for control and 20±2.1 μM in the presence of NBQX (n=5, P<0.01; Figure 2B), while nH increased significantly to 1.6±0.12 (P<0.05). To circumscribe this potentiating action of NBQX, we investigated the effect of concentrations ranging from 0.1 – 3 μM on responses evoked by 500 μM AMPA (n=7; Figure 2C). Significant (P<0.05) potentiation of the responses was seen with 0.1 – 1 μM NBQX, with the greatest effect being a potentiation by 40±7% (P<0.001) with 1 μM NBQX. Larger concentrations depressed the response to AMPA, though this was first significant (P<0.05) in relation to the control at ⩾2.5 μM. Responses of cortical neurones to AMPA (n=7) were depressed by the same concentrations of NBQX (Figure 2C), and no potentiating effect was disclosed.

Figure 1.

Action of a low concentration of NBQX on responses evoked by AMPA on a cultured cortical (A) and spinal cord (B) neurone. One hundred μM AMPA was applied for 15 s with 40 s pause between applications. Control responses to AMPA are shown to the left, and in the continuous presence of NBQX (0.3 μM) to the right. The neurones were pre-treated with NBQX for 5 s before co-application with AMPA. All results were recorded at a holding potential of −60 mV. (C) Bar graph summarizing the effect of 0.3 μM NBQX on responses of cortical and spinal cord neurones to 100 μM AMPA. NBQX depressed the peak responses of both neurone types to AMPA, though the cortical response was depressed to a significantly greater extent (P<0.001). Plateau responses of cortical neurones to AMPA were depressed by NBQX, while plateau responses of spinal cord neurones were slightly enhanced, and significantly larger than cortical responses (P<0.001). Data bars represent the percentage of control currents (mean±s.e.mean) in the absence of NBQX. The numbers of neurones are shown above each bar. (***, P<0.001 by two-tailed t-test compared with control.).

Figure 2.

The effect of low concentrations of NBQX on responses of cultured cortical and spinal cord neurones to AMPA (A) Plots showing that 0.1 and 0.3 μM NBQX competitively antagonized the plateau responses of cortical neurones to AMPA, with EC50 values of 17±1.3 μM for the control (○; n=20), 41±3.3 μM in the presence of 0.1 μM NBQX (•; n=12) and 83±11 μM in the presence of 0.3 μM NBQX (□; n=5). Schild plot analysis yields a pKi value of 6.6 with a slope of 0.92 (B) 0.3 μM NBQX antagonized the plateau responses of spinal cord neurones to low concentrations (<20 μM) of AMPA, and enhanced the responses to higher concentrations of AMPA. EC50 values were 11±1.4 μM for the control (○) and 20±2.1 μM in the presence of NBQX (•). (C) The effect of eight concentrations of NBQX (range: 0.1 – 3 μM) on responses of cortical (○) and spinal cord (•) neurones to 500 μM AMPA. NBQX at ⩽1 μM potentiated responses of spinal cord to AMPA, while higher concentrations depressed the response. Responses of cortical neurones to AMPA were reduced at all concentrations of NBQX. Data points represents mean±s.e.mean after normalization to the control current (evoked by 1000 μM AMPA in (A) and (B), and 500 μM AMPA in (C)) in the absence of NBQX.

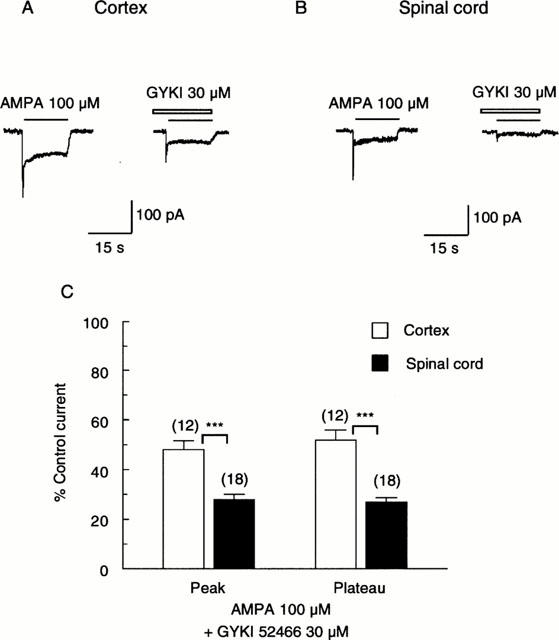

We then investigated the effect of the 2,3 benzodiazepine, GYKI 52466. Figure 3 illustrates that 30 μM GYKI 52466 markedly inhibited responses of both cortical and spinal cord neurones to 100 μM AMPA. In cortical neurones, peak responses to AMPA were reduced by 51±4% and plateau responses by 41±3% (n=12, P<0.001 with respect to control level). In spinal cord neurones, the inhibition by GYKI 52466 was by 73±1.5% for peak responses to AMPA, and by 75±1.5% for plateau responses (n=18, P<0.001). While GYKI 52466 did not discriminate between peak and plateau responses to AMPA of either type of neurone (P>0.05 in both cases), responses of spinal cord neurones were antagonized to a significantly greater extent than responses of cortical neurones (P<0.001). 30 μM GYKI 52466 is therefore close to the IC50 value for cortical neurones and the IC75 value for spinal cord neurones. 30 μM GYKI 52466 caused a downward shift of the concentration-response relationship of plateau responses of cortical neurones to AMPA (not shown) with responses to all concentrations of AMPA being reduced by 56%. This result is consistent with the notion that GYKI 52466 acts as a non-competitive antagonist at AMPA receptors.

Figure 3.

The effect of GYKI 52466 on responses of a cortical (A) and spinal cord (B) neurone to AMPA. Peak and plateau responses of both types of neurone to 100 μM AMPA were markedly inhibited by 30 μM GYKI 52466. Drugs were applied as in Figure 1. (C) Bar graph summarizing the inhibition of responses to AMPA by GYKI 52466. For both types of neurone, 30 μM GYKI 52466 depressed peak and plateau components to a similar extent (P>0.05). However, the depression of the spinal cord responses (peak by 73±2%; plateau by 75±1%) was significantly greater than the depression of cortical responses (peak by 51±4% and plateau by 41±3%). (***, P<0.001.).

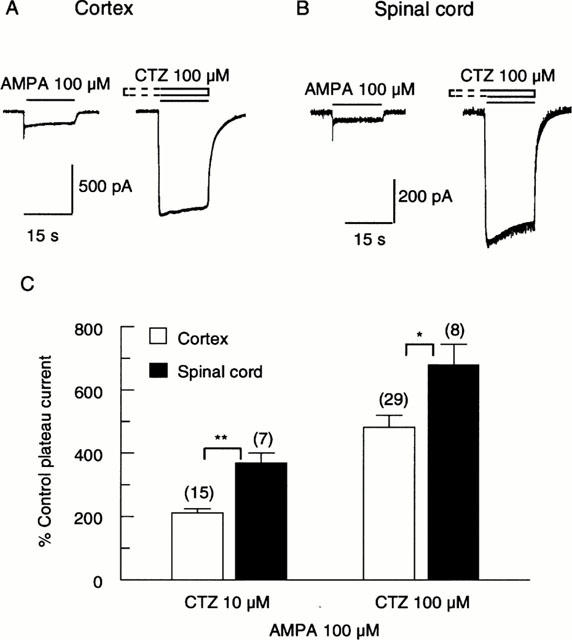

We then tested the effect of CTZ on responses evoked by AMPA. CTZ at a concentration of 100 μM strongly potentiated responses of both cortical and spinal cord neurones to 100 μM AMPA (Figure 4A,B). However, the potentiation of responses of spinal cord neurones (6.8 fold) was significantly greater than cortical neurones (4.8 fold, P<0.05; Figure 4C). This relatively greater potentiation of responses of spinal cord neurones was even more evident when CTZ was applied at the lower concentration of 10 μM, with 3.7 fold potentiation for spinal cord neurones and 2.1 fold potentiation for cortical neurones (P<0.01; Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Action of cyclothiazide (CTZ) on responses of cortical and spinal cord neurones to AMPA. Representative traces showing that 100 μM CTZ caused a marked potentiation of the responses of a cortical (A) and a spinal cord (B) neurone to 100 μM AMPA. The neurones were pre-treated with CTZ for 30 s before co-application with AMPA. (C) Bar graph summarizing results from similar experiments showing that CTZ concentration-dependently potentiated responses of both cortical and spinal cord neurones to 100 μM AMPA. The potentiation of responses of spinal cord neurones was significantly greater than for cortical neurones. (**, P<0.01; *, P<0.05 for 10 μM and 100 μM CTZ, respectively.).

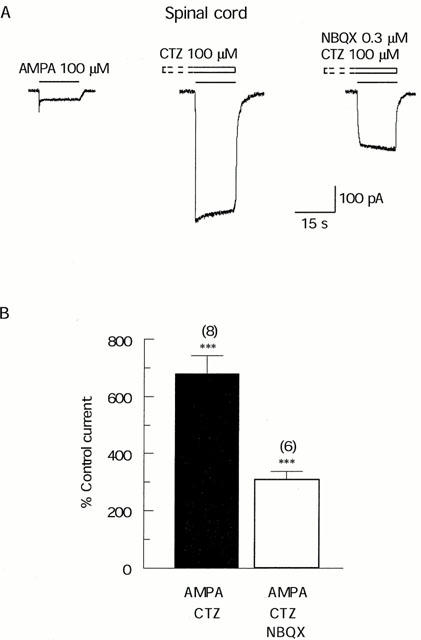

Since we have shown above that low concentrations (⩽1 μM) of NBQX potentiate the plateau responses of spinal cord neurones to AMPA, we tested the effect of NBQX following blockade of AMPA receptor desensitization by CTZ. In the presence of 100 μM CTZ, 0.3 μM NBQX reduced the response to 100 μM AMPA by about 50% (Figure 5A). In six neurones, 100 μM CTZ increased the plateau response to 100 μM AMPA to 680±64% of control. 0.3 μM NBQX then reduced this response by about 55% (to 308±30% of the control value; Figure 5B). This compares to a reduction of peak responses by about 62% in the absence of CTZ (Figure 1C).

Figure 5.

The effect of NBQX on responses of spinal cord neurones to AMPA following blockade of desensitization by CTZ. (A) Representative traces showing that CTZ 100 μM caused a 6 fold potentiation of the response to 100 μM AMPA, following which 0.3 μM NBQX reduced the response by about 50%. Drugs were applied as in Figure 4B. (B) Bar graph summarizing results from similar experiments showing that 100 μM CTZ potentiated responses to AMPA about 7 fold, following which 0.3 μM NBQX reduced the responses from 680±64% to 308±30% (***, P<0.001). Data bars represent mean±s.e.mean of percentage of the control current.

Response to kainate

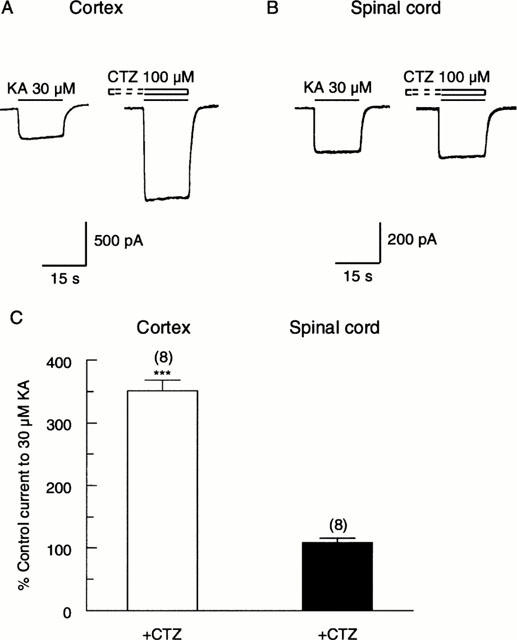

Since KA can activate AMPA receptors (Boulter et al., 1990), we then tested whether the responses of cortical and spinal cord neurones to KA were affected by CTZ. Figure 6A,B shows that 100 μM CTZ markedly enhanced the response of a cortical neurone to 30 μM KA, while having little effect on the response of a spinal cord neurone. In a population of neurones, 100 μM CTZ potentiated responses of cortical neurones to 351±17% (n=8; P<0.001) of the control level, while having no significant effect on responses of spinal cord neurones (potentiated to 108±7% of control (n=8, P>0.05; Figure 6C). We also investigated the concentration-dependence of the effect of CTZ and showed 10 μM CTZ enhanced responses of cortical neurones 1.8 fold (not shown).

Figure 6.

The action of CTZ on responses of cortical and spinal cord neurones to KA. Representative traces showing that 100 μM CTZ caused a 3 fold potentiation of the response of a cortical neurone to 30 μM KA (A), but had little effect on the response of a spinal cord neurone to KA (B). The neurones were pre-treated with CTZ for 30 s before co-application with KA (C). Bar graph summary showing that 100 μM CTZ caused a 3.5 fold potentiation of responses of cortical neurones to KA, but had no significant effect on responses of spinal cord neurones. ***P<0.001 by two-tailed t-test compared with control.

Kinetics and rectifying properties of responses of cortical and spinal cord neurones to AMPA

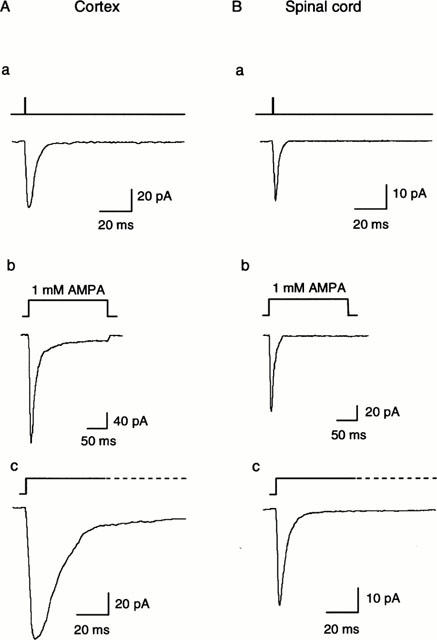

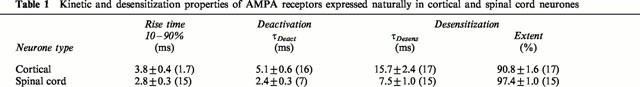

To investigate the kinetics and I – V properties of responses to AMPA, a piezoelectric stepping device was used to make ‘concentration-jump' (sub-millisecond) applications of the agonists (see Methods). Pilot experiments showed that such applications evoked much slower responses from whole neurones attached to the cover-slip than from excised outside-out patches. The latter configuration was therefore chosen for subsequent experiments. Deactivation was investigated by studying the time course of return to baseline following application of 1 mM AMPA for 1 ms. Desensitization was investigated by studying the decline in response during maintained application of AMPA (for 200 ms). Representative traces in Figure 7 show that both deactivation and desensitization were much slower in cortical than in spinal cord neurones. Both the deactivation time constant (τDeact) and the desensitization time constants (τDesens) of cortical neurones were more than double those of spinal cord neurones (P<0.01 in both cases; Figure 7 and Table 1). Note that τDeact was about three times faster than τDesens in both types of neurone. Responses of spinal cord neurones desensitized to a significantly greater extent than cortical neurones (Figure 7, Table 1). The 10 – 90% rise time of responses of spinal cord neurones was slightly faster for spinal cord than cortical neurones (Table 1), though this difference was not significant (P=0.06).

Figure 7.

The kinetic properties of AMPA receptors expressed in a cortical (A) and a spinal cord (B) neurone. a Representative responses to a 1 ms step application of 1 mM AMPA. The recovery phase represents deactivation, which is much faster in the spinal cord than the cortical neurone. b and c Representative responses to a 200 ms step application of 1 mM AMPA from different neurones shown on two time scales. The decaying phases represent desensitization, which was much faster and more complete in the spinal cord neurones.

Table 1.

Kinetic and desensitization properties of AMPA receptors expressed naturally in cortical and spinal cord neurones

The I – V relationships of AMPA responses was investigated by stepping the membrane potential in 20 mV increments during which a 200 ms application of AMPA was made. Figure 8 illustrates that the I – V relationship of peak current responses to 1 mM AMPA was linear for a cortical neurone, whereas it showed inward rectification for a spinal cord neurone. The degree of rectification was assessed by the rectification index (RI):

where I is the peak current response measured at +60 and −60 mV (given by the subscript) and Erev is the reversal potential. Cortical neurones showed on average slight outward rectification with a RI of 1.18±0.11 (n=11), while spinal cord neurones showed marked inward rectification with an RI of 0.39±0.05 (n=14).

Figure 8.

Current-voltage (I – V) relationships of AMPA receptors expressed in cortical (A) and spinal cord (B) neurones. a Representative responses were evoked by a 200 ms step application of 1 mM AMPA at 20 mV intervals of Vh. b Cumulative data showing peak responses plotted as a function of Vh. The cortical neurones (n=11) show a linear I – V relationship, while the spinal cord neurones (n=14) show inward rectification.

Analysis of AMPA receptor subunits by single-cell PCR

Expression of GluR1 – 4

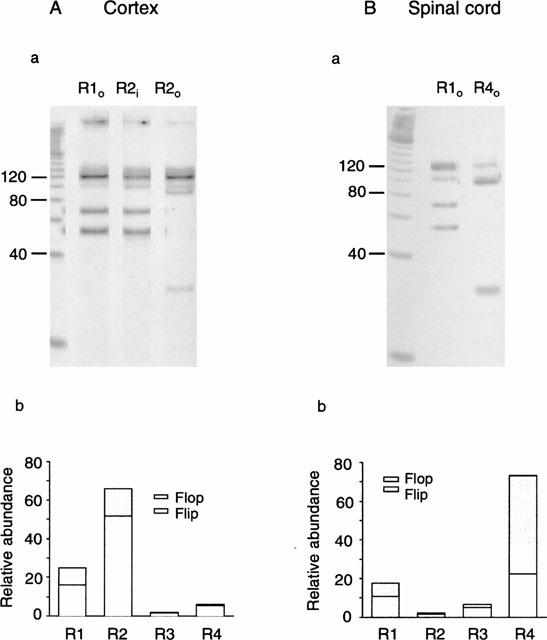

The results presented above show marked pharmacological and mechanistic differences between responses of cortical and spinal cord neurones. We therefore adopted a nested RT – PCR approach to detect the presence of mRNAs encoding AMPA receptor subunits (GluR1 – 4) in the cytoplasm harvested from single neurones. The resulting 740 bp band contained PCR fragments from potentially all the AMPA receptor mRNAs. The amount of each subunit was detected by digestion with selective enzymes that cut only one subunit type (see Methods). RT – PCR was initially performed on the total RNA isolated from two cortical cultures, and showed that mRNAs for all subunits are expressed (Figure 9A). Single-cell RT – PCR was then performed on 21 cortical and 16 spinal cord neurones. The overwhelming majority of cortical neurones (20/21) expressed GluR2. In five of these, GluR2 was the only subunit detected, while in 14 cells it was co-expressed with GluR1 (Tables 2 and 3). In spinal cord neurones, GluR4 was the most frequently expressed mRNA, and was expressed alone in 9/16 neurones. The level of GluR2 mRNA was very low. Both types of neurone showed very low expression of GluR3 (Table 2). Since the relative expression of transcripts for each subunit would be expected to contribute to the functional properties, quantification of the fragments was performed using 32P-labelled material. In cortical neurones, the relative abundance of transcripts for GluR2 and GluR1 subunits were 66±7% and 25±6% respectively, whereas the amounts for GluR3 and R4 mRNAs were only 1.9±1.1% and 6.8±3.3%, respectively (Figures 9B and 10Ab). In spinal cord neurones, the relative amount of GluR4 mRNA was 73±10%, while the expression of GluR2 and GluR3 was very low (2.1±1.5% and 6.8±6.2%, respectively; Figures 9C and 10Bb). On the other hand, the relative amount of GluR1 mRNA was 18±8%, which was not significantly different from cortical neurones (P>0.05; Figure 10Ab,Bb).

Figure 9.

RT – PCR analysis of the expression of mRNAs for AMPA receptor subunits (GluR1 – 4) in cortical and spinal cord neurones. (A) A sample isolated from a whole cortical culture was reverse transcribed to cDNA and amplified using specific primers for AMPA receptors (see Methods for details). The PCR products were digested using specific restriction enzymes, BglI, Bsp1286I, Eco47III and EcoRI for cutting GluR1, R2, R3 and R4, respectively. Electrophoresis was performed on a 1.5% agarose gel. Digestion yielded two fragments for each subunit (288 and 449 bp for GluR1, 269 and 468 bp for GluR2, 345 and 398 bp for GluR3 and 332 and 405 bp for GluR4) their respective sizes are shown by comparison with a standard molecular weight marker (1 kb DNA ladder (M)). All four subunits are expressed in the whole cortical culture. (B) Single-cell PCR of a representative cortical neurone, showing the presence of only GluR1 and GluR2. (B) Single-cell PCR of a representative spinal cord neurone, showing the presence of only GluR1 and GluR4.

Table 2.

Percentage expression of subunits and relative amount of total splice variants

Table 3.

Occurrence of GluR subunit combinations in cortical and spinal cord neurones

Figure 10.

Analyses of the relative abundance of each AMPA receptor subunit and their alternative splice variants in cortical (A) and spinal cord (B) neurones. a The subunit bands (see Figure 9) were isolated and further amplified using specific primers (see Methods). The products were digested using the enzymes StuI (which recognizes the flop versions of GluR2, 3 and 4) and BsrI (which recognizes GluR1o and GluR2i) and run on an agarose gel using a 20 bp DNA ladder as a molecular weight marker. For the cortical neurone, the relative abundances of flip/flop were 16%/9% for GluR1 and 52%/13% for GluR2. For the spinal cord neurone, the relative abundances of flip/flop were 11%/7% for GluR1 and 51%/22% for GluR4. b. Histograms showing the relative abundances of mRNAs for each subunit and flip/flop splice variants for cortical and spinal cord (n=16) neurones. Values are given in the text. The results show that cortical neurones predominantly expressed the flip version of GluR2, whereas spinal cord neurones predominantly expressed the flop version of GluR4.

Alternative splice variants

We also investigated the relative contributions of the flip/flop variants generated by alternative splicing. Subunit-specific bands selected for the restriction analysis were amplified by PCR and subjected to restriction analysis. Analyses of the flip/flop compositions performed on a cultured cortical neurone (for GluR1 and 2) and a spinal cord neurone (for GluR1 and 4) are shown in Figure 10. The relative abundance of flip/flop variants showed marked and characteristic differences between cortical and spinal cord neurones. The flip version of all subunits was predominantly expressed in cortical neurones, with a total amount of 78±6%. The relative abundances of the flip variants of GluR1 – 4 were 16, 50.7, 5.5 and 5.8%, respectively (Figure 10Ab). Of the 23% of flop variants, the relative abundances were 9, 13, 0.2 and 0.5%, for GluR1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively (Figure 10Ab). In contrast, spinal cord neurones mainly expressed flop variants (60.5% of the total), with relative abundances for GluR1 – 4 of 6.8, 0.9, 1.8 and 51%, respectively (Figure 10Bb). Whereas the flip and flop variants of GluR1 – 3 did not show marked differences between cortical and spinal cord neurones, the relative amount of GluR4o was significantly greater in spinal cord than cortical neurones (P<0.001). Overall, the results indicate that cortical neurones predominantly express mRNA for GluR2i, whereas spinal cord neurones predominantly express mRNA for GluR4o.

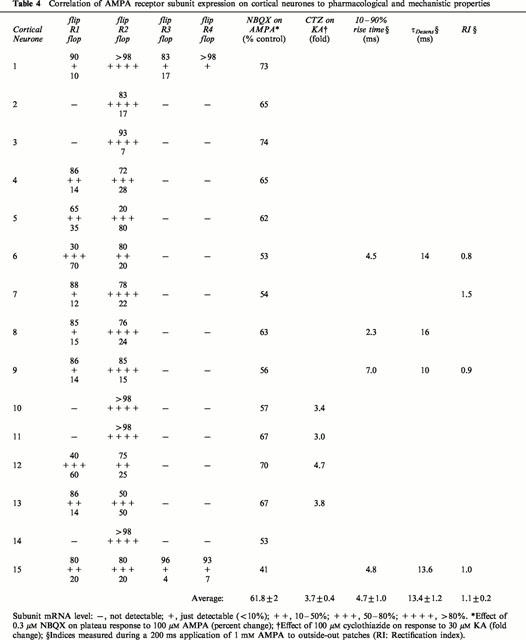

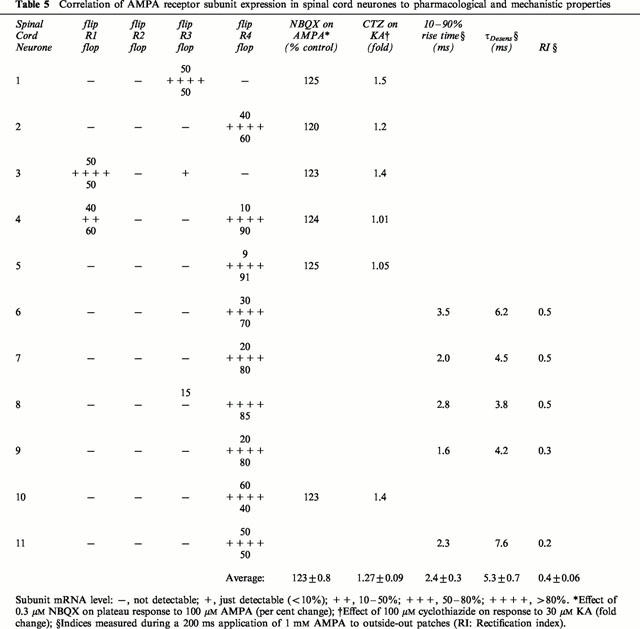

Correlation of AMPA subunit expression to neuronal properties

Pharmacological and/or mechanistic aspects properties were investigated in 15 of the cortical neurones (Table 4) and 11 of the spinal cord neurones (Table 5), on which single-cell PCR was performed. Note that significant amounts of GluR2 were detected in every cortical neurone, but was not present in a single spinal cord neurone. On the other hand, nine of the spinal cord neurones showed large amounts of GluR4, which was only just detectable in two of the cortical neurones.

Table 4.

Correlation of AMPA receptor subunit expression on cortical neurones to pharmacological and mechanistic properties

Table 5.

Correlation of AMPA receptor subunit expression in spinal cord neurones to pharmacological and mechanistic properties

The action of 0.3 μM NBQX on the plateau response to 100 μM AMPA was tested on all 15 cortical neurones. In 13 of these, GluR2 accounted for at least 50% of the subunits expressed, and was predominantly in the flip form (apart from neurone 5). Significant amounts (>10%) of GluR1 were present in six of the neurones, in four of which the flip variant was dominant (Table 4). NBQX 0.3 μM reduced the plateau response to 100 μM AMPA in every neurone tested (range of reduction: by 26 – 59%). The subunits in the six spinal cord neurones in which the action of NBQX was tested showed great diversity (Table 5). Four contained predominantly GluR4, though the flop version showed only marked dominance (>80%) in two of these (neurones 4 and 5). The other neurones contained GluR3 (neurone 1) and GluR1 (neurone 3), with equal amounts of the splice variants. Despite this diversity, NBQX potentiated the plateau responses to very similar extents (range of potentiation: by 20 – 25%).

The effect of 100 μM CTZ on the response to 30 μM KA was tested on four cortical neurones (Table 4). There was a tendency for a greater potentiation when GluR1 was present (neurones 12 and 13) than when GluR2 was the only subunit expressed (neurones 10 and 11). For the six spinal cord neurones on which the effect of CTZ was tested (Table 5), there was very little potentiation when GluR4o was predominantly expressed (neurones 4 and 5), and there was distinctly greater potentiation when more of the flip variant was expressed (neurones 2 and 10). More potentiation was seen for the neurones expressing GluR3 (neurone 1) and GluR1 (neurone 3), though it should be noted that these showed equal expression of the flip and flop variants.

Kinetics and rectification were tested on five cortical and five spinal cord neurones. All of the spinal cord neurones expressed only GluR4 (Table 5), and the RI was ⩽0.5. Although there was a definite tendency for τDesens to increase with increasing amounts of the flip variant, there was no particular correlation for the other kinetic parameters. The cortical neurones showed little rectification on average, and the rise-times and τDesens were approximately two and three times slower than the spinal cord neurones, respectively.

Discussion

In the present study, we have addressed the physiological and pharmacological properties of responses mediated by AMPA receptors on cultured cortical and spinal cord neurones. In every aspect tested, there were characteristic and significant differences between the two types of neurone. Single-cell RT – PCR techniques were coupled to patch-clamp recordings in a representative number of neurones to resolve the molecular determinants which possibly contribute to the functional and pharmacological responses.

Expression of mRNAs for AMPA receptor subunits in cortical and spinal cord neurones

All of the mRNAs for GluR1 – 4 subunits were detected to some extent, both in cortical and spinal cord neurones. In cortical neurones, GluR2 and GluR1 accounted for 91% of all subunits and were expressed together in 67% of neurones, predominantly as the flip variants (78%). A similar preponderance of these two subunits has been seen in other studies on pyramidal (Lambolez et al., 1996) and other principal neurones of the hippocampus (Geiger et al., 1995). Nevertheless, it should be noted that GluR2 was detected alone in 24% (5/21) of the cortical neurones examined.

In spinal cord neurones, GluR4 occurred alone in 9/16 (=56%) of neurones, and with other subunits in 4/16 (=25% neurones). GluR4 accounted for 73% of all subunits, of which the flop version accounted for 67%. Nearly half the subunits expressed are, therefore, GluR4o and these would be expected to dominate the functional and pharmacological profile of the spinal cord responses. However, GluR1 and 3 were detected alone or in combination with each other in 3/16 (=19%) neurones. Electrophysiological and immunocytochemical studies (Goldstein et al., 1995) and single-cell PCR studies (Vandenberghe et al., 2000) would indicate that dorsal horn neurones express a relatively wide diversity of AMPA GluRs with variable permeability to Ca2+. On the other hand, GluR2 mRNA accounts for 40% of the AMPA receptor mRNAs in motoneurones (Vandenberghe et al., 2000).

The ensuing comparisons are made on the basis that responses of cortical neurones are mediated primarily by GluR2i/R1i and spinal cord neurones primarily by GluR4o. The comparisons should also be seen in the light that, of the total mRNAs for AMPA receptors, 51% was GluR2i in cortical neurones (compared with 1% in spinal cord neurones), while in spinal cord neurones 51% was GluR4o (compared with 0.2% in cortical neurones) (Figure 10). The results will be compared and contrasted to those reported from studies on both recombinant and naturally expressed receptors.

Kinetic and rectifying properties of responses evoked by rapid applications

The kinetic and desensitizing properties of responses mediated by AMPA receptors are correlated with their subunit composition (being most rapid with GluR4), alternative splicing (being most rapid with flop) and the extent of RNA editing at the R/G site (Mosbacher et al., 1994; Partin et al., 1994; Lomeli et al., 1994; Lambolez et al., 1996). The kinetics of naturally expressed AMPA receptors have also been shown to differ markedly, with interneurones displaying much faster kinetics than principal neurones (Livsey et al., 1993; Jonas et al., 1994; Geiger et al., 1995; Götz et al., 1997).

In the present work, the time constant of activation was marginally faster for spinal cord than for cortical neurones, while both deactivation and desensitization were about twice as fast for spinal cord receptors than cortical receptors. Mosbacher et al. (1994) reported that recombinant GluR4o subunits (expressed homomerically, or in combination with GluR2i or GluR2o) showed time constants of deactivation (0.6 ms) and desensitization (0.9 ms), which were markedly faster than homomerically expressed GluR1 subunits (1.1 ms for deactivation and 3.4 ms for desensitization). Recombinant GluR1i or GluR3i (expressed either homomerically, or heteromerically in conjunction with GluR2i) exhibit relatively slow τDesens's (ranging from 3.4 – 10.7 ms) (Partin et al., 1994; Lomeli et al., 1994). Thus, while the ratio of the response times are similar to those presented here for naturally expressed receptors, the absolute times are about five times faster for the recombinant receptors. On the other hand, our results correlate nicely with the slow τDesens recorded in hippocampal and neocortical principal neurones (range 10.1 – 16.3 ms), and the fast τDesens recorded in most interneurones (5.1 – 6.1 ms) (Geiger et al., 1995).

Spinal cord neurones showed more complete desensitization (97.4%) than did cortical neurones (90.8%). Previous studies of recombinant receptors have demonstrated that incomplete desensitization is associated with the expression of flip variants, in particular GluR2i (Sommer et al., 1990; Partin et al., 1994). With the semi-rapid application system, responses of spinal cord neurones also desensitized to a significantly greater extent than cortical neurones (by 58 and 45%, respectively). However, since the solution exchange time (30 – 50 ms) is slow compared with the kinetics of the response, a correspondingly smaller proportion of the peak response is detected.

The GluR2 subunit shows almost complete editing at the Q/R site (Seeburg, 1996) and the presence of GluR2 determines the ionic permeability and overall rectifying properties of heteromeric combinations (Dingledine et al., 1999). Complexes containing GluR2 exhibit linear or outwardly rectifying of I – V relationships, while those lacking the GluR2 subunit are permeable to Ca2+ and show strong inward rectification (Verdoorn et al., 1991; Bochet et al., 1994).

Marked rectification is seen in whole-cell recordings from a variety of neurones that show only very low expression of GluR2, including cultured hippocampal neurones (Jonas et al., 1994) and cerebellar granule cells (Kamboj et al., 1995). On the other hand, responses recorded from outside-out patches show only weak rectification with relatively small differences in the presence and absence of edited GluR2 (Jonas et al., 1994; Geiger et al., 1995). Therefore, rectification appears to depend on the presence of diffusible cytoplasmic factor(s). Intracellular polyamines, such as spermine and spermidine, may fulfil this role, since they cause inward rectification at unedited Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors with glutamine at the Q/R site (Kamboj et al., 1995; Koh et al., 1995).

Although our recordings were from outside-out patches, there were still significant differences between the I – V relationships. Cortical neurones showed, on average, slightly outward rectifying I – V relationships, whereas spinal cord neurones showed marked inward rectification. This would be in accordance with the predominant expression of edited GluR2 by cortical neurones, and its absence in spinal cord neurones, as confirmed by recordings correlated with single-cell PCR (Tables 4 and 5).

Pharmacological properties of responses of cortical and spinal cord neurones to AMPA

The agonist action of AMPA

AMPA is a relatively selective agonist for GluR1 – 4, where it evokes rapidly desensitizing responses (Seeburg, 1993). AMPA is also a relatively weak agonist at certain combinations of KA receptors, including GluR5 (Sommer et al., 1992), GluR6+KA2 (Herb et al., 1992) and, possibly, GluR7+KA2 (Schiffer et al., 1997). However, since less than 10% of the response to 300 μM AMPA remained in the presence ⩾100 μM GYKI 52466 (not shown), this suggests that KA receptors contribute very little to the responses.

AMPA was 1.55 times more potent on spinal cord than cortical neurones, which would suggest that AMPA is correspondingly more potent on GluR4o than GluR2i/R1i combinations. A number of expression studies indicate that GluR2-containing complexes generally have a lower affinity for agonists than homomeric GluR4 receptors (Nakanishi et al., 1990; Stein et al., 1992; Gallo et al., 1992), while AMPA has been shown to have a 3 fold greater potency at homomerically expressed GluR4o than GluR1o (Vogensen et al., 2000) and GluR1o/GluR2i (Wahl et al., 1998).

Of the five cortical neurones in which GluR2 was the only detectable subunit, 91% was the flip version, which would be expected to form the majority of the receptors. Electrophysiological recordings from all five of these neurones (Table 4), showed that the absolute sizes of the responses to 100 μM AMPA were not significantly different from those of responses of other neurones. This contrasts with responses of heterologously expressed homomeric GluR2, which generate very small currents (Boulter et al., 1990; Nakanishi et al., 1990). This apparent discrepancy might result from an undetectable amount of other subunits (i.e. GluR1 and/or GluR3 were expressed at <3% of the GluR2 mRNA level). Alternatively, GluR2 might generate functional channels on the surface of neurones when associated with other neurone-specific proteins, such as the PDZ-containing glutamate receptor proteins, GRIP (Wyszynski et al., 1999) or the γ-subunit of the Ca2+ channel in the stargazer phenotype (Hashimoto et al., 1999).

Antagonism of AMPA receptor-mediated responses.

NBQX

Peak responses of cortical neurones to AMPA were reduced nearly twice as much by 0.3 μM NBQX as were responses of spinal cord neurones, suggesting that NBQX is a more potent antagonist of GluR2i/R1i than GluR4o containing receptors. NBQX competitively antagonized equilibrium (plateau) responses of cortical neurones to AMPA with a pKi value of 6.6. The corresponding Ki value (230 nM) is slightly larger than for recombinant receptors expressed in oocytes, for which a Ki of 112 nM has been reported for GluR1/R2 (Stein et al., 1992) and 197 nM for GluR1 (Wahl et al., 1996).

On the other hand, sub-micromolar concentrations of NBQX potentiated plateau responses of spinal cord neurones (but not cortical neurones) to larger (>30 μM) concentrations of AMPA. This action on plateau responses was occluded at higher concentrations of NBQX, when the receptor antagonist action of NBQX prevailed. Sub-micromolar concentrations of NBQX have also been shown to potentiate AMPA receptor-mediated responses of superior collicular neurones (Parsons et al., 1994), while 1 nM NBQX has been shown to cause a marked potentiation of plateau responses of cultured hippocampal neurones to glutamate (Rammes et al., 1998). Relatively weak antagonists, such as AMOA (Wahl et al., 1992) and ATPO (Dai et al., 1998b) have also been shown to potentiate plateau responses at high agonist concentrations.

Our results would suggest that NBQX reduces desensitization of the AMPA receptors expressed in spinal cord neurones to a modest extent. This was confirmed by the finding that 0.3 μM NBQX reduced the response to 100 μM AMPA by about 50% following blockade of receptor desensitization with CTZ. This allows us to obtain an estimate of the effect of NBQX on desensitization. If NBQX did not affect desensitization, it would also be expected to reduce the plateau response in untreated neurones by about 50%. Since the plateau phase of responses to AMPA were increased to about 120%, the difference reflects the reduction of desensitization by NBQX. CTZ increased the plateau response to AMPA by about 600%. Thus, the relative reduction of desensitization by NBQX is [(120 – 50)/600)×100]≈12%. It is likely that this reduction in desensitization contributes to the apparent difference in the potency of NBQX on cortical and spinal cord neurones (i.e. the vertical difference between the plots shown in Figure 2C).

The effect of NBQX on desensitization was not exclusively associated with the presence of GluR4o: two of the spinal cord neurones exhibited only GluR1 and GluR3, respectively, but were potentiated to a similar extent to those containing GluR4 (Table 5). The response of every single cortical neurone to AMPA was reduced by NBQX (Table 4). Although there was a degree of subunit heterogeneity, every neurone exhibited GluR2 (in contrast to its complete absence in spinal cord neurones). It is, therefore, tempting to draw the conclusion that the presence of GluR2 prevents the action of NBQX on desensitization.

GYKI 52466

The 2,3 benzodiazepines, GYKI 53655 and GYKI 52466, act at a distinct site on the AMPA receptor complex to block the response potently and selectively (Tarnawa et al., 1989; Rammes et al., 1996; Donevan & Rogawski, 1998). Accordingly, and in contrast to the action of NBQX discussed above, GYKI 52466 reduced peak and plateau responses to a similar extent. The degree of inhibition was irrespective of the concentration of AMPA, which is characteristic of non-competitive inhibition. GYKI 52466 antagonized responses of spinal cord neurones to a significantly greater extent than cortical neurones, with 30 μM being approximately the IC50 value for cortical neurones and the IC75 value for spinal cord neurones. Reported IC50 values for GYKI 52466 on other naturally expressed AMPA receptors are 9.8 μM for superior colliculus neurones (Rammes et al., 1996) and 18 μM for cerebral cortical neurones (Wilding & Huettner, 1995), while for hippocampal neurones, values of 7.5 μM (Donevan & Rogawski, 1993) and 11.7 μM (Rammes et al., 1998) have been reported. With regard to studies of recombinant AMPA receptors expressed in oocytes, it has been shown that GYKI 52466 generally has a higher potency towards heteromeric receptor combinations (being slightly more potent when GluR4 is present) but did not discriminate between flip and flop variants (Johansen et al., 1995).

Cyclothiazide

CTZ selectively blocks desensitization of AMPA receptors, and therefore causes massive potentiation of the responses, both in recombinant and naturally expressed receptors (Partin et al., 1993; Wong & Mayer, 1993; Wilding & Huettner, 1995; Yamada & Turetsky, 1996). Our results show that CTZ concentration-dependently potentiated responses to AMPA of both types of neurones. The potentiation of spinal cord neurones was significantly greater than cortical neurones, which is likely to reflect the different subunit composition. Concentration-jump applications of AMPA showed that responses of cortical neurones desensitized by 90.8%, and spinal cord neurones by 97.4%. Therefore, complete blockade of desensitization would be expected to result in potentiations of approximately 11 fold and 38 fold, respectively. These ratios are much greater than those recorded for plateau responses using semi-rapid application (approximately 5 fold for cortical neurones and 7 fold for spinal cord neurones). This discrepancy possibly arises because a greater proportion of the receptors are not desensitized when the application rate is slower. That said, it would nevertheless be expected that spinal cord neurones would show a relatively greater CTZ-sensitive desensitization, which was the case.

Studies on recombinant receptors show that the action of CTZ is highly dependent on the subunit composition, the splice variants (Sekiguchi et al., 1998) and the editing status (Yamada & Turetsky, 1996; Fleck et al., 1996). Studies on the effect of CTZ on homomerically expressed AMPA receptors showed a wide range of potentiation, with ratios of 102 fold for GluR1i, 27 fold for GluR2i, 216 fold for GluR3i and 16 fold for GluR4i (Yamada & Turetsky, 1996). Although flip variants desensitize to a lesser degree than flop variants, they nevertheless have a higher affinity for CTZ (Fleck et al., 1996) and exhibit a greater degree of potentiation (Sekiguchi et al., 1998). These results are apparently not in harmony with our results on naturally expressed receptors. CTZ caused a greater potentiation of spinal cord responses, which are likely to be mediated by GluR4o, while increasing the concentration of CTZ from 10 to 100 μM caused an additional 3.5 fold potentiation of responses of cortical neurones, but only about a 2 fold potentiation of responses of spinal cord neurones. Since the spinal cord responses were potentiated to a relatively greater extent at the lower concentration of CTZ, this suggests that the flop variants are more sensitive to CTZ. Sekiguchi et al. (1998) have also shown that AMPA responses of hippocampal neurones (which predominantly express GluR1i/R2i) are potentiated to a lesser extent than the same heteromeric receptors expressed in oocytes.

Responses of cortical neurones to KA were potentiated 3.5 fold by 100 μM CTZ, which is only marginally (but significantly) less than the 5 fold potentiation of AMPA responses. These results would suggest that KA is a relatively potent agonist at GluR2i/R1i receptors, where it evokes desensitizing responses that can be potentiated by CTZ. On the other hand, responses of spinal cord neurones to KA were, on average, unaffected by CTZ. There could be a number of explanations for this. Firstly, studies on the responses of recombinant AMPA receptors to KA have shown that CTZ strongly potentiated the responses of flip, but not flop, variants (Partin et al., 1994). There is some support for this from the six spinal cord neurones for which PCR results were available (Table 4). CTZ had virtually no effect on responses to KA when GluR4o was present in large amounts, while progressively more potentiation was seen in neurones expressing increasing amounts of flop variants. Secondly, it is possible that KA evokes no response at GluR4o receptors, which would imply that the entire response is mediated by KA receptors. Finally, KA evokes a non-desensitizing response at GluR4o receptors, which cannot, therefore, be potentiated by CTZ. We consider this to be a likely explanation.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that cultured cortical neurones predominantly express the flip variant of GluR2, which is often in combination with GluR1i, while spinal cord neurones predominantly express the flop version of GluR4. These combinations dominate the pharmacological and electrophysiological properties of the responses recorded from the neurones. Moreover, the relatively low expression of GluR2 in cultured spinal cord neurones would make this a suitable preparation for studying Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors.

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to Kenneth V. Christensen (Institute of Molecular and Structural Biology, University of Aarhus) for instruction in the technique of restriction analysis, to Kirsten Kandborg for preparation of the cultures and Sys Kristensen for technical help. We are grateful to Bjarke Ebert (Royal Danish School of Pharmacy) for many stimulating discussions. We are also grateful to the following for gifts of substances: Istvan Tarnawa (University of Budapest) for GYKI 52466; Povl Krogsgaard-Larsen and Ulf Madsen (Royal Danish School of Pharmacy) for AMPA; Novo Nordisk for NBQX. We thank the Danish Medical Research Council and Aarhus Universitets Forsknings Fond for financial support.

Abbreviations

- ABSS

artificial balanced salt solution

- AMPA

2-amino-3-(3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolyl)propionate

- CNS

central nervous system

- CTZ

cyclothiazide

- dNTP

deoxyribonucleotides triphosphate

- FCS

foetal calf serum

- FUdR

5′-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine

- GYKI 52466

1-(4-aminophenyl)-4-methyl-7,8-methyl-endioxyl-5h-2,3-benzodiazepine

- HS

horse serum

- I-V

current-voltage relationship

- KA

kainate

- NBQX

2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulphamoyl-benzo-(f)quinoxaline

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- RT – PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

References

- BANKE T., LAMBERT J.D.C. Novel potent AMPA analogues differentially affect desensitization of AMPA receptors in cultured hippocampal neurons. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;367:405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00975-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOCHET P., AUDINAT E., LAMBOLEZ B., CRÉPEL F., ROSSIER J., IINO M., TSUZUKI K., OZAWA S. Subunit composition at the single-cell level explains functional properties of a glutamate-gated channel. Neuron. 1994;12:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOULTER J., HOLLMANN M., O'SHEA-GREENFIELD A., HARTLEY M., DENERIS E., MARON C., HEINEMANN S. Molecular cloning and functional expression of glutamate receptor subunit genes. Science. 1990;249:1033–1037. doi: 10.1126/science.2168579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNASHEV N. Recombinant ionotropic glutamate receptors: Functional distinctions imparted by different subunits. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 1993;3:318–331. [Google Scholar]

- CHITTAJALLU R., BRAITHWAITE S.P., VERNON R.J., HENLEY J.M., HENLEY C.M. Kainate Receptors: Subunits, synaptic localization and function. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:26–35. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINGRIDGE G.L., LESTER R.A.J. Excitatory amino acid receptors in the vertebrate central nervous system. Pharmacol. Rev. 1989;40:143–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAI W.-M., EBERT B., LAMBERT J.D.C. Comparison of non-NMDA receptor-mediated responses on cultured cortical and spinal cord neurones. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998a;10 Suppl.10:131. [Google Scholar]

- DAI W.-M., EBERT B., MADSEN U., LAMBERT J.D.C. Studies of the antagonistic actions of (RS)-2-amino-3-[5-tert-butyl-3-(phosphonomethoxy)-4-isoxazolyl] propionic acid (ATPO) on non-NMDA receptors in cultured rat neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998b;125:1517–1528. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DINGLEDINE R., BORGES K., BOWIE D., TRAYNELIS S.F. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DONEVAN S.D., ROGAWSKI M.A. GYKI 52466, a 2,3-benzodiazepine, is a highly selective, noncompetitive antagonist of AMPA/kainate receptor responses. Neuron. 1993;10:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90241-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DONEVAN S.D., ROGAWSKI M.A. Allosteric regulation of a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate receptors by thiocyanate and cyclothiazide at a common modulatory site distinct from that of 2,3-benzodiazepines. Neuroscience. 1998;87:615–629. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLECK M.W., BÄHRING R., PATNEAU D.K., MAYER M.L. AMPA receptor heterogeneity in rat hippocampal neurons revealed by differential sensitivity to cyclothiazide. J. Neurophysiol. 1996;75:2322–2333. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.6.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLETCHER E.J., LODGE D. New developments in the molecular pharmacology of a-amino- 3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate and kainate receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 1996;70:65–89. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(96)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALLO V., VYKLICKY L., HAYES W.P., VYKLICKY L., JR, WINTERS C.A., BUONANNO A. Molecular cloning and developmental analysis of a new glutamate receptor subunit isoform in cerebellum. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:1010–1023. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01010.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEIGER J.R.P., MELCHER T., KOH D.-S., SAKMANN B., SEEBURG P.H., JONAS P., MONYER H. Relative abundance of subunit mRNAs determines gating and Ca2+ permeability of AMPA receptors in principal neurons and interneurons in rat CNS. Neuron. 1995;15:193–204. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDSTEIN P.A., LEE C.J., MACDERMOTT A.B. Variable distributions of Ca2+-permeable and Ca2+-impermeable AMPA receptors on embryonic rat dorsal horn neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;73:2522–2534. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.6.2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GÖTZ T., KRAUSHAAR U., GEIGER J., LÜBKE J., BERGER T., JONAS P. Functional properties of AMPA and NMDA receptors expressed in identified types of basal ganglia neurons. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:204–215. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00204.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASHIMOTO K., FUKAYA M., QIAO X., SAKIMURA K., WATANABE M., KANO M. Impairment of AMPA receptor function in cerebellar granule cells of ataxic mutant mouse stargazer. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:6027–6036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06027.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERB A., BURNASHEV N., WERNER P., SAKMANN B., WISDEN W., SEEBURG P. The KA-2 subunit of excitatory amino acid receptors shows widespread expression in brain and forms ion channels with distinctly related subunits. Neuron. 1992;8:775–785. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLMANN M., HARTLEY M., HEINEMANN S. Ca2+ permeability of KA-AMPA-gated glutamate receptor channels depends on subunit composition. Science. 1991;252:851–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1709304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLMANN M., HEINEMANN S. Cloned glutamate receptors. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1994;17:31–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHANSEN T.H., CHAUDHARY A., VERDOORN T.A. Interactions among GYKI-52466, cyclothiazide, and aniracetam at recombinant AMPA and kainate receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;48:946–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONAS P., RACCA C., SAKMANN B., SEEBURG P.H., MONYER H. Differences in Ca2+ permeability of AMPA-type glutamate receptor channels in neocortical neurons caused by differential GluR-B subunit expression. Neuron. 1994;12:1281–1289. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90444-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMBOJ S.K., SWANSON G.T., CULL-CANDY S.G. Intracellular spermine confers rectification on rat calcium- permeable AMPA and kainate receptors. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1995;486:297–303. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOH D.-S., BURNASHEV N., JONAS P. Block of native Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors in rat brain by intracellular polyamines generates double rectification. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1995;486:305–312. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRISTIANSEN U., LAMBERT J.D.C., FALCH E., KROGSGAARD-LARSEN P. Electrophysiological studies of the GABAA receptor ligand, 4-PIOL, on cultured hippocampal neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;104:85–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMBOLEZ B., AUDINAT E., BOCHET P., CRÉPEL F., ROSSIER J. AMPA receptor subunits expressed by single purkinje cells. Neuron. 1992;9:247–258. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMBOLEZ B., ROPERT N., PERRAIS D., ROSSIER J., HESTRIN S. Correlation between kinetics and RNA splicing of a-amino- 3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptors in neocortical neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:1797–1802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LERMA J. Kainate receptors: an interplay between excitatory and inhibitory synapses. FEBS Lett. 1998;430:100–104. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00462-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIVSEY C.T., COSTA E., VICINI S. Glutamate-activated currents in outside-out patches from spiny versus aspiny hilar neurons of rat hippocampal slices. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:5324–5333. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-12-05324.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOMELI H., MOSBACHER J., MELCHER T., HÖGER T., GEIGER J.R.P., KUNER T., MONYER H., HIGUCHI M., BACH A., SEEBURG P.H. Control of kinetic properties of AMPA receptor channels by nuclear RNA editing. Science. 1994;266:1709–1713. doi: 10.1126/science.7992055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOSBACHER J., SCHOEPFER R., MONYER H., BURNASHEV N., SEEBURG P.H., RUPPERSBERG J.P. A molecular determinant for submillisecond desensitization in glutamate receptors. Science. 1994;266:1059–1062. doi: 10.1126/science.7973663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKANISHI N., SHNEIDER N.A., AXEL R. A family of glutamate receptor genes: evidence for the formation of heteromultimeric receptors with distinct channel properties. Neuron. 1990;5:569–581. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90212-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARSONS C.G., GRUNER R., ROZENTAL J. Comparative patch clamp studies on the kinetics and selectivity of glutamate receptor antagonism by 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo(F)quinoxaline (NBQX) and 1-(4-amino-phenyl)-4-methyl-7,8-methyl-endioxyl-5H-2,3-benzodiazepine (GYKI 52466) Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:589–604. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARTIN K.M., PATNEAU D.K., MAYER M.L. Cyclothiazide differentially modulates desensitization of A-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor splice variants. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;46:129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARTIN K.M., PATNEAU D.K., WINTERS C.A., MAYER M.L., BUONANNO A. Selective modulation of desensitization at AMPA versus kainate receptors by cyclothiazide and concanavalin A. Neuron. 1993;11:1069–1082. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90220-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATERNAIN A.V., MORALES M., LERMA J. Selective antagonism of AMPA receptors unmasks kainate receptor- mediated responses in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:185–189. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATNEAU D.K., VYKLICKY L., JR, MAYER M.L. Hippocampal neurons exhibit cyclothiazide-sensitive rapidly desensitizing responses to kainate. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:3496–3509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03496.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMMES G., SWANDULLA D., COLLINGRIDGE G.L., HARTMANN S., PARSONS C.G. Interactions of 2,3-benzodiazepines and cyclothiazide at AMPA receptors: patch clamp recordings in cultured neurones and area CA1 in hippocampal slices. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1209–1221. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16718.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMMES G., SWANDULLA D., SPIELMANNS P., PARSONS C.G. Interactions of GYKI 52466 and NBQX with cyclothiazide at AMPA receptors: experiments with outside-out patches and EPSCs in hippocampal neurones. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1299–1320. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAKIMURA K., MORITA T., KUSHIYA E., MISHINA M. Primary structure and expression of the g2 subunit of the glutamate receptor channel selective for kainate. Neuron. 1992;8:267–274. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90293-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHIFFER H.H., SWANSON G.T., HEINEMANN S.F. Rat GluR7 and a carboxyterminal splice variant, GluR7b, are functional kainate receptor subunits with a low sensitivity to glutamate. Neuron. 1997;19:1141–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEEBURG P.H. The molecular biology of mammalian glutamate receptor channels. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:359–365. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEEBURG P.H. The role of RNA editing in controlling glutamate receptor channel properties. J. Neurochem. 1996;66:1–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEKIGUCHI M., TAKEO J., HARADA T., NORIMOTO T., KUDO Y., YAMASHITA S., KOHSAKA S., WADA K. Pharmacological detection of AMPA receptor heterogeneity by use of two allosteric potentiators in rat hippocampal cultures. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:1294–1303. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOMMER B., BURNASHEV N., VERDOORN T.A., KEINÄNEN K., SAKMANN B., SEEBURG P.H. A glutamate receptor channel with high affinity for domoate and kainate. EMBO J. 1992;11:1651–1656. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOMMER B., KEINÄNEN K., VERDOORN T.A., WISDEN W., BURNASHEV N., HERB A., KÖHLER M., TAKAGI T., SAKMANN B., SEEBURG P.H. Flip and flop: A cell-specific functional switch in glutamate- operated channels of the CNS. Science. 1990;249:1580–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.1699275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEIN E., COX J.A., SEEBURG P.H., VERDOORN T.A. Complex pharmacological properties of recombinant a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate receptors subtypes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;42:864–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWANSON G.T., FELDMEYER D., KANEDA M., CULL-CANDY S.G. Effect of RNA editing and subunit co-assembly on single- channel properties of recombinant kainate receptors. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1996;492:129–142. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TARNAWA I., FARKAS S., BERZSENYI P., PATAKI A., ANDRÁSI F. Electrophysiological studies with a 2,3-benzodiazepine muscle relaxant: GYKI 52466. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;167:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANDENBERGHE W., ROBBERECHT W., BRORSON J.R. AMPA receptor calcium permeability, GluR2 expression, and selective motoneuron vulnerability. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:123–132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00123.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERDOORN T.A., BURNASHEV N., MONYER H., SEEBURG P.H., SAKMANN B. Structural determinants of ion flow through recombinant glutamate receptor channels. Science. 1991;252:1715–1718. doi: 10.1126/science.1710829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VOGENSEN S.B., JENSEN H.S., STENSBOL T.B., FRYDENVANG K., BANG-ANDERSEN B., JOHANSEN T.N., EGEBJERG J., KROGSGAARD-LARSEN P. Resolution, configurational assignment, and enantiopharmacology of 2-amino-3-[3-hydroxy-5-(2-methyl-2H-tetrazol-5-yl)isoxazol-4-yl]propionic acid, a potent GluR3-and GluR4-preferring AMPA receptor agonist [In Process Citation] Chirality. 2000;12:705–713. doi: 10.1002/1520-636X(2000)12:10<705::AID-CHIR2>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAHL P., ANKER C., TRAYNELIS S.F., EGEBJERG J., RASMUSSEN J.S., KROGSGAARD-LARSEN P., MADSEN U. Antagonist properties of a phosphono isoxazole amino acid (ATPO) at GluR1–4 AMPA receptor subtypes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:590–596. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.3.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAHL P., MADSEN U., BANKE T., KROGSGAARD-LARSEN P., SCHOUSBOE A. Different characteristics of AMPA receptor agonists acting at AMPA receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;308:211–218. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAHL P., NIELSEN B., KROGSGAARD-LARSEN P., HANSEN J.J., SCHOUSBOE A., MILEDI R. Stereoselective effects of AMOA on non-NMDA receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Neurosci. Res. 1992;33:392–397. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490330305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILDING T.J., HUETTNER J.E. Differential antagonism of a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid-preferring and kainate-preferring receptors by 2,3-benzodiazepines. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;47:582–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILDING T.J., HUETTNER J.E. Antagonist pharmacology of kainate- and a-amino-3hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid-preferring receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;49:540–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WONG L.A., MAYER M.L. Differential modulation by cyclothiazide and concanavalin A of desensitization by native a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid-and kainate-preferring glutamate receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;44:504–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WYSZYNSKI M., VALTSCHANOFF J.G., NAISBITT S., DUNAH A.W., KIM E., STANDAERT D.G., WEINBERG R., SHENG M. Association of AMPA receptors with a subset of glutamate receptor-interacting protein in vivo. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:6528–6537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06528.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMADA K.A., TURETSKY D.M. Allosteric interactions between cyclothiazide and AMPA/kainate receptor antagonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1663–1672. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YUE K.T., MACDONALD J.F., PEKHLETSKI R., HAMPSON D.R. Differential effects of lectins on recombinant glutamate receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;291:229–235. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(95)90062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]