Abstract

There is evidence that noradrenaline contributes to the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain produced by trauma to a peripheral nerve. It is, however, unclear which subtype(s) of α adrenergic receptors (AR) may be involved. In addition to pro-nociceptive actions of AR stimulation, α2 AR agonists produce antinociceptive effects.

Here we studied the contribution of the α2 AR subtypes, α2A, α2B and α2C to the development of neuropathic pain. We also examined the antinociceptive effect produced by the α2 AR agonist dexmedetomidine in nerve-injured mice.

The studies were performed in mice that carry either a point (α2A) or a null (α2B and α2C) mutation in the gene encoding the α2 AR. To induce a neuropathic pain condition, we partially ligated the sciatic nerve and measured changes in thermal and mechanical sensitivity.

Baseline mechanical and thermal withdrawal thresholds were similar in all mutant and wild-type mice; and, after peripheral nerve injury, all mice developed comparable hypersensitivity (allodynia) to thermal and mechanical stimulation.

Dexmedetomidine reversed the allodynia at a low dose (3 μg kg−1, s.c.) and produced antinociceptive effects at higher doses (10 – 30 μg kg−1) in all groups except in α2A AR mutant mice. The effect of dexmedetomidine was reversed by intrathecal, but not systemic, injection of the α2 AR antagonist RS 42206.

These results suggest that neither α2A, α2B nor α2C AR is required for the development of neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury, however, the spinal α2A AR is essential for the antinociceptive effects of dexmedetomidine.

Keywords: α adrenergic receptors, peripheral nerve injury, neuropathic pain, thermal and mechanical allodynia, antinociception, guanethidine sympathectomy

Introduction

Injury to a peripheral nerve can lead to a pain syndrome that is characterized by spontaneous pain, pain in response to normally innocuous stimuli (allodynia) and exaggerated pain in response to noxious stimuli (hyperalgesia). Although the etiology of neuropathic pain is not completely understood, in some patients it can be relieved by sympatholytic treatment (see Bonica, 1990). Under normal conditions, sensory neurons do not respond to sympathetic stimulation or to adrenergic agonists (Jänig et al., 1996). After injury to a peripheral nerve, however, sensory neurons can be activated by sympathetic stimulation and respond to local or circulating catecholamines (Devor & Jänig, 1981; Scadding, 1981; Sato & Perl, 1991). There are multiple sites where the abnormal interaction between the sensory and sympathetic nervous systems occurs, including damaged axons at the nerve injury site (Devor & Jänig, 1981), uninjured cutaneous nociceptors that innervate partially denervated skin (Ali et al., 1999) and in the dorsal root ganglion, where sprouting of sympathetic efferents around large diameter cell bodies has been described (McLachlan et al., 1993; Devor et al., 1994; Michaelis et al., 1996).

With a view to developing new therapies to treat these conditions, studies in both patients and in animal models of neuropathic pain have addressed the contribution of adrenergic receptor blockers. Several studies reported that the non-selective α AR antagonist, phentolamine, can reduce nerve injury-associated allodynia and hyperalgesia (Arner, 1991; Raja et al., 1991; Kim et al., 1993; Tracey et al., 1995, but see Ringkamp et al., 1999a). Although primate models and clinical studies indicate that the α1 AR is critical to the sympathetic-sensory coupling (Davis et al., 1991; Drummond et al., 1996; Ali et al., 1999), several rodent studies have implicated the α2 AR (Tracey et al., 1995; Xie et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1996).

Three different α2 AR subtypes, α2A, α2B and α2C have been identified (see Bylund et al., 1994). Immunocytochemical and in situ hybridization studies indicate that all subtypes are located in regions associated with the processing of nociceptive information, including the superficial layers of the spinal dorsal horn (Rosin et al., 1993; 1996; Stone et al., 1998) and the dorsal root ganglion (Nicholas et al., 1993; Gold et al., 1997). The purpose of the present study was to examine the contribution of the different α2 AR subtypes to the development of neuropathic pain. Because selective antagonists to these receptor subtypes are not readily available, we examined mice that carry either a point (α2A AR; MacMillan et al., 1996) or null (α2B and α2C AR; Link et al., 1996) mutation in the gene that encodes the α2 AR. The D79N point mutation in the α2A AR mutant results in selective uncoupling of the α2 AR from activation of potassium currents; the coupling to inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels and adenylate cyclase is not altered (Surprenant et al., 1992). However, although some of the signalling pathways are preserved in the α2A AR D79N mutant mice, the density of α2A AR binding in the mutant is reduced by 80% compared to wild-type mice (MacMillan et al., 1996).

Finally, because several studies have demonstrated that α2 AR agonists produce antinociceptive effects in rodent models of acute pain (Reddy et al., 1980; Yaksh, 1985; Kalso et al., 1991; Takano & Yaksh, 1992) and of neuropathic pain (Yaksh et al., 1995, but see also Puke et al., 1994), and also in acute and chronic pain in humans (Tamsen & Gordh, 1984; Eisenach et al., 1996), we examined the contribution of the different α2 AR subtypes to the antinociceptive effects of the α2 AR agonist, dexmedetomidine. Previous studies suggested that the α2A subtype mediates the antinociceptive effect of α2 AR agonists in acute models of pain (Hunter et al., 1997; Lakhlani et al., 1997; Stone et al., 1997). However, because α2 AR expression may be altered after nerve injury (Cho et al., 1997; Fareed et al., 1997; Birder & Perl, 1999; Stone et al., 1999; Shi et al., 2000), it is possible that the action of dexmedetomidine is altered by nerve injury or that the α2 AR receptor subtype that is responsible for its antinociceptive effect is different.

Methods

Animals

The generation of the mutant mice has been described previously (MacMillan et al., 1996; Link et al., 1996). In the α2A AR mutant mice, the receptor carries a D79N point mutation that uncouples the α2A AR from potassium channels (MacMillan et al., 1996); these mice were obtained from Dr Lee Limbird (Vanderbilt University). By contrast, the α2B AR and α2C AR mutant mice carry a null mutation in the gene that encodes the α2 AR (Link et al., 1996); these mice were obtained from Dr Brian Kobilka (Stanford University). The experiments were performed on age, weight (20 – 30 grams) and sex-matched mice. In the first experiment, which examined the effect of nerve injury in α2A AR mutant and wild-type mice, male mice were used. In subsequent studies, female α2A AR mutant and wild-type mice were used. We did not observe any difference between male and female mice in general behaviour or with respect to nerve injury-induced allodynia. Female mice were used for all experiments involving α2B and α2C AR mutant and wild-type mice. Because the D79N mice were generated on a 129SvJ background, we used 129SvJ wild-type mice (Jackson Laboratories) as controls. The mice that carried a null mutation in either the α2B AR (129SvJ/C57BL) or α2C AR (129SvJ/FVB) gene were on mixed genetic backgrounds (Link et al., 1996). Wild-type and homozygous mice were bred from heterozygous mice. Finally, the antagonist experiments were performed on male C57BL/6 mice weighing 20 – 25 g (Bantin-Kingman). All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, San Francisco.

Nerve injury model

The nerve injury model was induced as we described previously (Malmberg & Basbaum, 1998). Briefly, we anaesthetized the mice using a mixture of ketamine (intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 66 mg kg−1 Ketalar®, Parke-Davis, NJ, U.S.A.) and Xylazine (13 mg kg−1, i.p., Xylazine, Ben Venue Laboratories, OH, U.S.A.), and tied a tight ligature using 9-0 silk suture around approximately ⅓ to ½ the diameter of the sciatic nerve, similar to the approach described in rats by Seltzer et al. (1990). Before and at several times after the injury, we determined both the thermal and mechanical sensitivity of the hindpaw on the injured and uninjured side. Thermal sensitivity was assessed by measuring the paw withdrawal latency to a radiant heat stimulus (Hargreaves et al., 1988). Paw withdrawal latency was determined by three measurements per paw over a testing period of 30 min. We adjusted the stimulus intensity to yield a 10 s withdrawal latency in the normal mouse; cut off in the absence of a response was 20 s. Mechanical sensitivity was assessed with calibrated von Frey filaments using the up – down paradigm (Chaplan et al., 1994). As we previously described, we began the testing with the 0.3 g filament; cut off in the absence of a response was 2.5 g (Malmberg & Basbaum, 1998).

Guanethidine sympathectomy

Systemic delivery of guanethidine produces a functional sympathectomy by depleting noradrenaline from sympathetic terminals (Boullin et al., 1966; Johnson et al., 1975; Maxwell et al., 1960). In a previous study, we showed that a single injection of guanethidine produces a partial and reversible reduction of thermal and mechanical allodynia in C57BL/6 mice (Malmberg & Basbaum, 1998). Based on the experiments in our previous studies, in the present study we made a single i.p. injection of 50 mg kg−1 guanethidine, 8 – 10 days after the nerve injury. We evaluated the thermal and mechanical thresholds before and 1 day after the guanethedine injection.

Dexmedetomidine studies

To study the effect of α2 AR activation, we used the α2 AR agonist dexmedetomidine (synthesized at Roche Bioscience, Palo, Alto, CA, U.S.A.). After determining the nerve injury-induced thresholds at the time of maximal allodynia, 10 – 14 days after injury, the mice were randomly assigned to different groups and were given a subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of 3, 10 or 30 μg kg−1 dexmedetomidine or 10 ml kg−1 saline as control. Twenty to 40 min later, at the peak effect of dexmedetomidine, we re-tested the thermal and mechanical sensitivity of the mice. Because the effects of dexmedetomidine were reversible, we used the same group of mice to generate the dose-response curve; the mice were used no more than 2 – 3 times to examine the effects of dexmedetomidine. Two to 4 days after the first dexmedetomidine injection, the mice were again randomly assigned to different groups and the effect of 3, 10, 30 μg kg−1 dexmedetomidine or saline was examined. Five to six mice were tested at each dose of dexmedetomidine.

Antagonist studies

To determine the site of action of the antinociceptive effect of dexmedetomidine, we used the non-selective α2 AR antagonist RS 42206 ([8aR-(8aα,12aα,13aα)]-N-[3-[5, 8a,9, 10,11, 12a,13a-octahydro-3-methoxy-6H-isoquino[2,1-g]naphthyridin-12 (8H) -yl) sulphonyl] -methanesulphonamide-HCl, synthesized at Roche Bioscience, Palo, Alto, CA, U.S.A., Clark et al., 1993). RS 42206 has been shown to be peripherally selective with a 47 fold ratio between its antagonistic effect of mydriasis in anaesthetized rats (central activity) or pressor effects in pithed rats (peripheral activity) after a single injection (M. Spedding and R.D. Clark, unpublished observations. For testing of similar compounds and methods, see Clark et al., 1991 and Xiao & Rand, 1990). The selectivity is believed to reflect a lack of central penetration by RS 42206. The α2 AR affinity of RS 42206 was determined as previously described (Jasper et al., 1998). Radioligand binding affinity estimates (pKi at human α2A-, α2B- and α2C AR for RS 42206 were 8.4, 8.3 and 8.0, respectively.

To inhibit peripheral α2 AR we delivered RS 42206 i.p. In a separate group of mice, we administered RS 42206 intrathecally to selectively block spinal α2 AR. Intrathecal delivery of RS 42206 was made by direct lumbar puncture (Hylden & Wilcox, 1980) in a volume of 5.0 μl. The systemic dose of 0.3 mg kg−1 RS 42206 i.p. was based on preliminary experiments (Hunter et al., unpublished observations) and the intrathecal dose of 30 μg was based on preliminary dose-response experiments (Malmberg & Basbaum, unpublished observations). The antagonist was administered 10 min before the injection of dexmedetomidine and the sensitivity to thermal and mechanical stimulation was assessed 20 – 40 min later.

Quantification and statistical analyses

The behavioural data are presented as mean±s.e.mean at different time points after the nerve injury. For statistical analysis of differences in thermal sensitivity, we used repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Student Newman-Keuls test for multiple comparisons. Statistical comparisons of mechanical thresholds were carried out using the non-parametric Friedman test followed by the Dunn's test for multiple comparisons (see Chaplan et al., 1994, for choice of statistical analysis of changes in mechanical thresholds). Statistical analysis of changes in thermal or mechanical sensitivity after drug treatment (e.g., guanethidine, dexmedetomidine or RS 42206) was carried out using paired t-test (thermal) or Wilcoxon signed rank test (mechanical), respectively. We compared post-guanethidine or post-dexmedetomidine latencies or thresholds to the values before the injection, but after the nerve injury.

Results

Effects of nerve injury

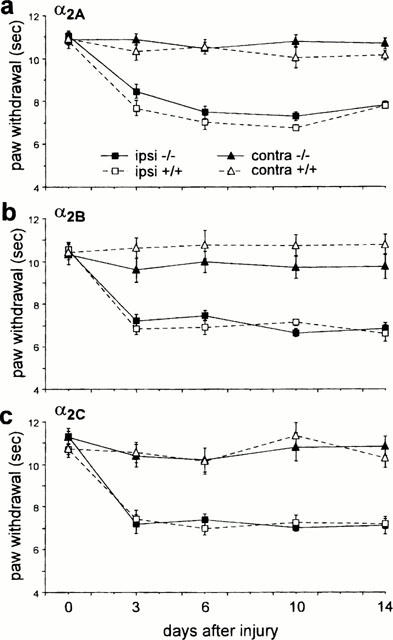

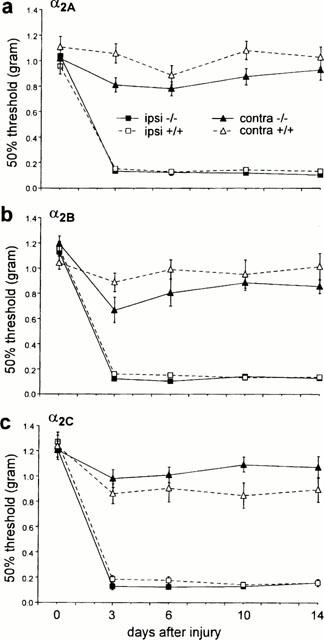

As previously described (Macmillan et al., 1996; Link et al., 1996), all the mutant mice showed normal general behaviour. Thermal response latencies and mechanical withdrawal thresholds before the nerve injury did not differ between the mutant and wild-type mice in any of the different groups. We also did not observe any significant difference in the development of thermal or mechanical allodynia in the α2A, α2B and α2C AR mutant wild-type mice (Figures 1 and 2). In all groups of mice we observed an increased sensitivity to thermal (Figure 1) and mechanical (Figure 2) stimulation of the hindlimb ipsilateral to the partial nerve injury. Although there was some variability among groups in the response thresholds of the hindlimb contralateral side to the nerve injury (data not shown), the contralateral changes were not statistically different.

Figure 1.

Effect of nerve injury in (a) α2A, (b) α2B and (c) α2C AR mutant (−/−) and wild-type (+/+) mice on thermal response latencies of the injured (ipsi) and the non-injured (contra) paw. Nerve injury produced comparable thermal allodynia in the wild-type and mutant mice. Data are presented as the mean±s.e.mean; n=10 per group.

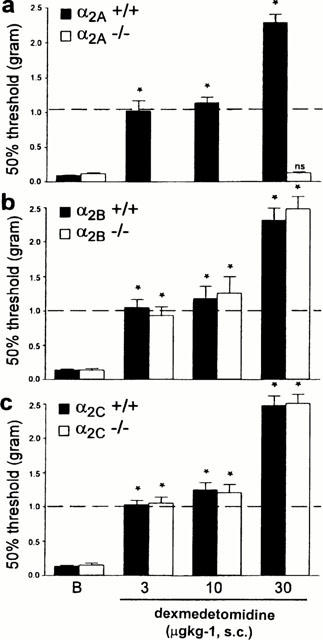

Figure 2.

Effect of nerve injury in (a) α2A, (b) α2B and (c) α2C AR mutant (−/−) and wild-type (+/+) mice on mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds of the injured (ipsi) and the non-injured (contra) paw. Nerve injury produced comparable mechanical allodynia in the wild-type and mutant mice. Data are presented as the mean±s.e.mean; n=10 per group.

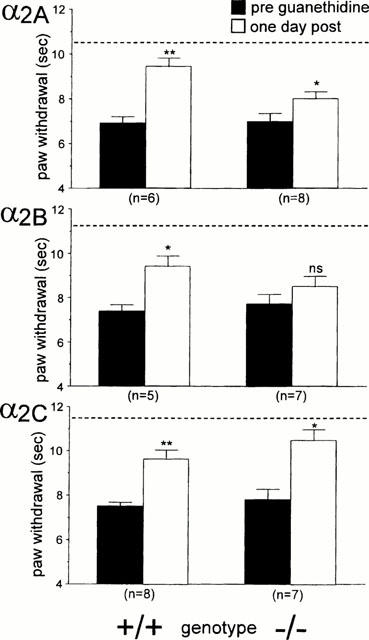

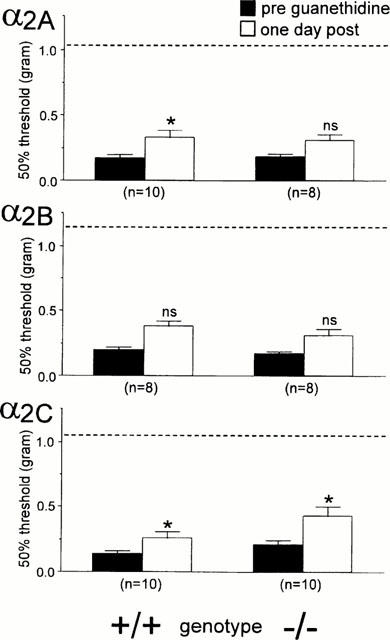

Effects of guanethidine sympathectomy

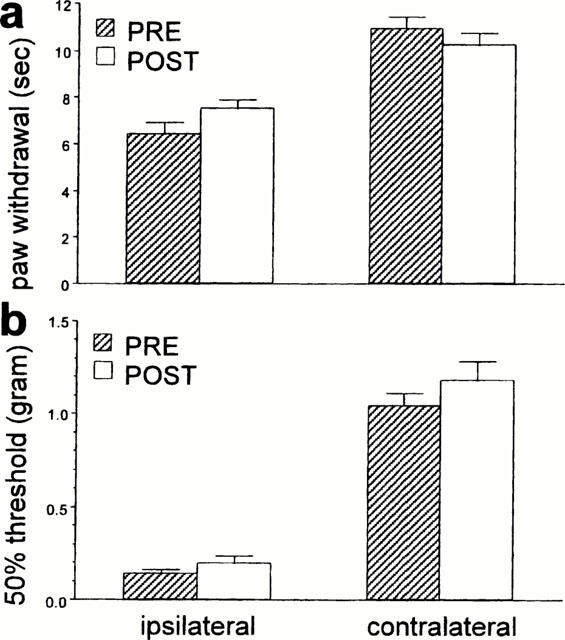

We only examined the effect of guanethidine in mice that showed a reduced thermal withdrawal latency of at least 20% and a decrease of at least 50% in the mechanical withdrawal threshold. In our experiments approximately 75 – 80% of nerve injured mice met these criteria. Intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg kg−1 of guanethidine produced a partial relief of thermal and mechanical allodynia 24 h post-administration in the different groups of mice (Figures 3 and 4). For some groups the change was significant (thermal latencies for α2A wild-type and mutant, α2B wild-type, α2C wild-type and mutant, and mechanical thresholds for α2A wild-type, α2C wild-type, α2C mutant mice) whereas other groups showed non-significant changes (e.g., thermal thresholds for α2B mutant, and mechanical thresholds for α2A mutant, α2B wild-type and mutant mice). However, the effect was in general small, particularly on the mechanical allodynia (Figure 4). Compared to pre-injury thresholds (indicated with a dotted line in the graph), significant thermal (P<0.05, paired t-test) and mechanical allodynia (P<0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank test) persisted for all the groups after the guanethidine treatment (the pre-injury data are not shown, although these thresholds are indicated by a dotted line in Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Effect of 50 mg kg−1 guanethidine on thermal allodynia of the injured paw in (a) α2A, (b) α2B and (c) α2C AR mutant (−/−) and wild-type (+/+) mice. Thermal paw withdrawal latencies were determined before (PRE) and 24 h after the injection of guanethidine (POST). Data are presented as the mean±s.e.mean. The asterisks indicate that guanethidine produced a significant increase in paw withdrawal latencies (comparing PRE vs PST, paired t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01). The dotted line indicates the baseline latency before the nerve-injury surgery was performed.

Figure 4.

Effect of 50 mg kg−1 guanethidine on mechanial allodynia of the injured paw in (a) α2A, (b) α2B and (c) α2C AR mutant (−/−) and wild-type (+/+) mice. Mechanical thresholds were determined before (PRE) and 24 h after the injection of guanethedine (POST). Data are presented as the mean±s.e.mean. The asterisks indicate a significant decrease in mechanical sensitivity (Wilcoxon signed rank test; *P<0.05) comparing PRE and POST. The dotted line indicates the baseline latency before the nerve injury was performed.

Effects of dexmedetomidine

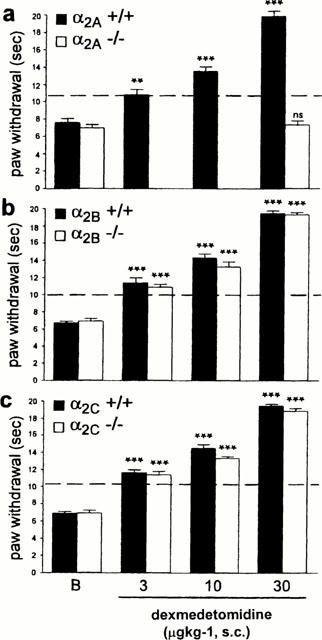

Dexmedetomidine dose-dependently increased thermal latencies and mechanical thresholds in α2A wild-type, α2B and α2C AR mutant and wild-type mice (Figures 5 and 6). By contrast, in the α2A AR mutant mice, dexmedetomidine was without effect, even at a dose of 100 μg kg−1, which in α2A AR wild-type mice produces significant side effects, including sedation and motor dysfunction (data not shown). Since 30 μg kg−1 dexmedetomidine was ineffective in the α2A AR mutant mice, we did not try lower doses in those animals (Figures 5 and 6). At the lowest effective dose (3.0 mg kg−1, s.c.), dexmedetomidine exerted an anti-allodynic effect in α2A wild-type, and in α2B and α2C AR mutant and wild-type mice, i.e., it returned the thermal and mechanical thresholds to pre-injury levels (Figures 5 and 6). This dose did not affect withdrawal thresholds on the non-injured side (data not shown), whereas at higher doses (10 – 30 μg kg−1), dexmedetomidine produced an antinociceptive/analgesic effect as indicated by increased paw withdrawal latencies and thresholds to thermal (Figure 5) and mechanical (Figure 6) stimulation, respectively, on both the injured and the uninjured sides.

Figure 5.

Effect of dexmedetomidine on thermal allodynia of the injured paw in (a) α2A, (b) α2B and (c) α2C AR mutant and wild-type mice. Ten to 14 days after the nerve transection, we established post-injury baseline (b) latencies. The animals then received a s.c. injection of dexmedetomidine and 20 – 40 min later we again measured thermal sensitivity. The asterisks indicate significant increases in paw withdrawal latencies (***P<0.001, ANOVA followed by Student Neuman-Keuls post hoc test) compared to post-injury baseline (indicated by ‘B' in the figure) values. The dotted line indicates the ‘normal' paw withdrawal latencies before the nerve injury was performed; an increase in latency above this value is considered to be antinociceptive. Data are presented as the mean±s.e.mean; n=5 – 6 per dose.

Figure 6.

Effect of dexmedetomidine on mechanical allodynia of the injured paw in (a) α2A, (b) α2B and (c) α2C AR mutant and wild-type mice. Ten to 14 days after the nerve injury, we established post-injury baseline (b) mechanical withdrawal thresholds. The animals then received a s.c. injection of dexmedetomidine and 20 – 40 min later we again measured mechanical thresholds. The asterisks indicate significant increases in paw withdrawal thresholds (*P<0.05, Friedman test followed by Wilcoxon signed rank test) compared to post-injury baseline (indicated by ‘B' in the figure) values. The dotted line indicates mechanical thresholds of the paw before the nerve injury was performed. Data are presented as the mean±s.e.mean; n=5 – 6 per dose.

Antagonist studies

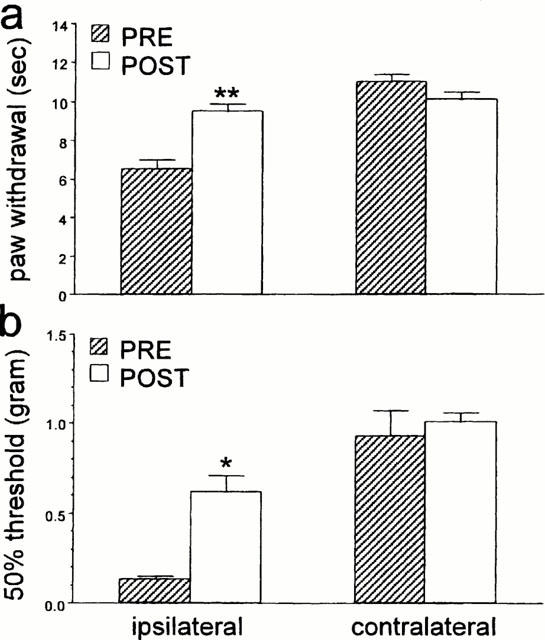

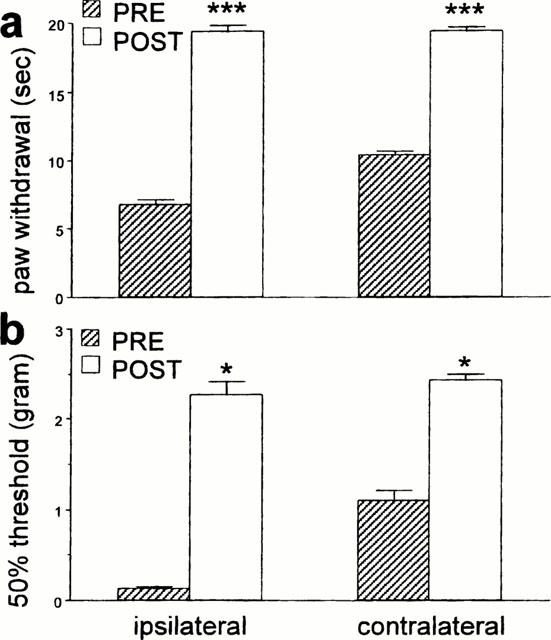

Antagonism of peripheral α2 AR by the i.p. injection of 0.3 mg kg−1 RS 42206 did not change the thermal or mechanical thresholds in nerve-injured mice (data not shown). Furthermore, pre-treatment with 0.3 mg kg−1 RS 42206 before the administration of an anti-allodynic dose of dexmedetomidine (3 μg kg−1, s.c.) was ineffective at antagonizing the effect of dexmedetomidine (Figure 7). Similarly, systemic injection of 0.3 mg kg−1 RS 42206 did not affect the antinociceptive action of 30 μg kg−1 dexmedetomidine (Figure 8). By contrast, intrathecal administration of 30 μg RS 42206 completed blocked the effect of 30 μg kg−1 dexmedetomidine, implicating a spinal site for the antinociceptive effect of dexmedetomidine (Figure 9).

Figure 7.

The effect of RS 42206 (0.3 mg kg−1, i.p.) on all anti-allodynic dose of dexmedetomidine (3.0 μg kg−1, s.c.) in nerve injured mice. Data are presented as the mean±s.e.mean for (a) thermal paw withdrawal latency and (b) mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds of the injured (ipsi) and the non-injured (contra) side. N=6 per group. The asterisks indicate significant increases (a: **P<0.01, t-test, b: *P<0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank test) comparing latencies or thresholds before and after drug treatment.

Figure 8.

The effect of RS 42206 (0.3 mg kg−1, i.p.) on an antinociceptive dose of dexmedetomidine (30 μg kg−1, s.c.) in nerve-injured mice. Data are presented as the mean±s.e.mean for (a) thermal paw withdrawal latency and (b) mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds of the injured (ipsi) and the non-injured (contra) paws. N=6 per group. The asterisks indicate significant increases (a: ***P<0.001, t-test, b: *P<0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank test) comparing latencies or thresholds before and after drug treatment.

Figure 9.

The effect of intrathecal injection of 30 μg RS 42206 on an analgesic dose of dexmedetomidine (30 μg kg−1, s.c.) in nerve-injured mice. Data are presented as the mean±s.e.mean (a) thermal paw withdrawal latency and (b) mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds of the inured (ipsi) and the non-injured (contra) paws. There was no significant difference (a: P>0.05, t-test, b: P>0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank test) between pre and post thermal latencies or mechanical thresholds indicating that RS 42206 reversed the effect of dexmedetomidine. N=6 per group.

Discussion

In the present study, mutant mice that carry either a point (α2A) or null (α2B and α2C) mutation in the gene that encodes the α2 AR were used to examine the contribution of α2 AR subtypes to indices of neuropathic pain (thermal and mechanical allodynia) and to the antinociception produced by central α2 AR activation. We found that the α2A, α2B and α2C AR mutant mice developed a thermal and mechanical allodynia after peripheral nerve injury that was comparable to those observed in wild-type mice. These studies suggest that none of the α2 AR receptor subtypes, by themselves, are required for the development of these indices of neuropathic pain. We also assessed the contribution of the sympathetic nervous system to the allodynia produced by nerve injury in the different α2 AR mutant mice. Because guanethidine sympathectomy was only modestly effective in all groups of mice, factors other than the sympathetic nervous system can sustain the allodynia produced by this model of nerve injury. Furthermore, we demonstrated that dexmedetomidine produced an anti-allodynic effect at low doses and an antinociceptive effect at higher dose in all but the α2A AR mutant mice. This observation strongly suggests that the pain-relieving effects of dexmedetomidine are indeed mediated via the α2A AR. Furthermore, using the hydrophilic α2 AR antagonist RS 42206 to selectively block the peripheral or central α2 AR, we showed that both the anti-allodynic and antinociceptive effects of dexmedetomidine are likely modulated by an action at the spinal cord level.

The development of genetically altered mice with a selective mutation in the genes encoding the different α2 AR subtypes has provided powerful tools to examine the contribution of these receptors to various physiological functions, including nociception. On general behavioural grounds, the mutant and wild-type mice cannot be distinguished. Of the studies previously published using the different α2 AR mutant mice, none report compensatory changes or abnormal behaviour due to the mutation (MacMillan et al., 1996; Link et al., 1996; Hunter et al., 1997; Stone et al., 1997). In contrast to the α2B and α2C AR mutant mice, which lack the receptor protein due to a null mutation (Link et al., 1996), the α2A AR mutant mice express a point (D79N) mutation in this receptor (MacMillan et al., 1996). The D79N mutation selectively uncouples the receptor from activation of potassium currents, but retains coupling to inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels and cyclic AMP production (Surprenant et al., 1992). As described above, although the calcium and adenylate cyclase signalling properties are presumably intact in the α2A AR D79N mouse, the density of α2A AR in this mouse is reduced by 80% compared to wild-type mice (MacMillan et al., 1996). For this reason we cannot exclude the possibility that the residual receptor, which retains coupling to voltage-gated calcium channels and adenylate cyclase, is sufficient to contribute to the development of neuropathic pain in these mice. However, we believe that this is unlikely because we also showed that blocking all peripheral α2 AR subtypes with RS 42206 had no effect on neuropathic pain behaviour. This provides further support for the proposal that α2 AR are not required for the development of neuropathic pain in this model.

Several previous reports indicated an involvement of α2 AR in the sympathetic-sensory coupling after nerve injury (Tracey et al., 1995; Xie et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1996). The observation that sympathectomy produced either no or, at best, a partial relief of the allodynia was, therefore, somewhat unexpected. This result was, however, consistent with the fact that we did not find a difference in nerve injury-induced pain between the different α2 AR mutant and wild-type mice. In fact, there is considerable disagreement as to the effect of sympatholytic therapy on the pain behaviour produced by various peripheral nerve injuries. Some studies have reported beneficial effects (Neil et al., 1991; Shir & Seltzer, 1991; Kim & Chung, 1991; Kim et al., 1993; Desmeules et al., 1995) while others have concluded that the procedures provided no relief of the allodynia (Willenbring et al., 1995; Lavand'homme et al., 1998; Ringkamp et al., 1999b). The use of different neuropathic pain models may contribute to observed variability of sympathectomy on neuropathic pain behaviour (Kim et al., 1997).

In the present study we observed a considerably smaller anti-allodynic effect of guanethidine compared to our previous study (Malmberg & Basbaum, 1998). The difference may be related, in part, to the different strains used in the two studies (C57/BL6 in the first study and 129Sv/J and 129SvJ/C57BL or 129SvJ/FVB mixed genetic backgrounds in the present study) and/or different sex (female) used in the two studies. Thus, recently it was demonstrated that different strains of rats show variability with regard to adrenergic sensitivity of the neuropathic pain behaviour (Lee et al., 1997). However, the observed partial effect of guanethidine and the development of neuropathic pain after nerve injury in the α2 AR subtype selective mutant mice, may indicate that the adrenergic nervous system contribution to the neuropathic pain behaviour is mediated via a different receptor than the α2 AR. Indeed, studies in the primate (Ali et al., 1999) and in patients (Davis et al., 1991; Drummond et al., 1996) indicate that the α1 AR is a critical determinant of the adrenergic sensitivity after peripheral nerve injury.

In the present study, we found that systemic delivery of the α2 AR agonist dexmedetomidine blocked the thermal and mechanical allodynia produced by nerve injury. Several studies have previously shown that activation of α2 AR by dexmedetomidine produces analgesia in both acute and persistent pain models in rodents (Kalso et al., 1991; Fisher et al., 1991; Takano & Yaksh, 1992; Yaksh et al., 1995). At higher doses, dexmedetomidine produced an effect on thermal latencies and mechanical thresholds on both the injured and non-injured hindlimbs, indicating that dexmedetomidine mediated an antinociceptive/analgesic effect in nerve-injured mice. In contrast, a lower dose of dexmedetomidine reversed the allodynia ipsilateral to the nerve injury, but had no effect on the non-injured (contralateral) side. Thus, at low doses dexmedetomidine is exclusively an anti-allodynic agent. The observation that dexmedetomidine was active on the injured side at a dose that did not affect the contralateral limb, further suggests that the injury induces adrenergic sensitivity. This may occur at the level of the ipsilateral dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and/or the spinal dorsal horn, where changes in α2 AR expression have been described (Cho et al., 1997; Fareed et al., 1997; Birder & Perl, 1999; Stone et al., 1999; Shi et al., 2000). However, the direction of the change is unclear. One report indicated that α2A AR immunoreactivity was upregulated in DRG neurons after sciatic nerve injury (Birder & Perl, 1999), but another study found evidence for downregulation in the spinal dorsal horn after nerve injury (Stone et al., 1999). Moreover, while two studies showed that mRNA for α2A AR was reduced after spinal nerve injury (Fareed et al., 1997; Cho et al., 1997), a recent study demonstrated an increase of this subtype in DRG neurons after nerve transection (Shi et al., 2000). Nerve injury has been shown to produce a decrease in α2C AR mRNA in DRG neurons (Cho et al., 1997), while α2C AR immunoreactivity was unchanged or increased at the spinal cord level using a similar spinal nerve-injury model (Stone et al., 1999).

Although the direction of the change in receptor expression after nerve injury is unclear, it is likely that an alteration of the α2A and α2C AR expression in the DRG and/or spinal cord underlies the shift in dexmedetomidine sensitivity that we observed in the nerve-injured mice. On the other hand, because changes in DRG receptor expression are usually mirrored by changes in the receptor expression at both the peripheral and central terminals of primary afferent fibres, it is possible that both central and peripheral sites are involved in the altered response to dexmedetomidine. By selectively antagonizing peripheral or central/spinal α2 AR with RS 42206 we showed that both the anti-allodynic and the antinociceptive effects of dexmedetomidine are produced by interaction with α2 AR in the spinal cord. Furthermore, we found that the anti-allodynic and the antinociceptive effects of dexmedetomidine were intact in α2B and α2C AR, but absent in the α2A AR mutant mice. Our results agree with previous reports showing that the antinociceptive effect of dexmedetomidine in the hot-plate and tail-flick tests is mediated via an activation of α2A AR (Lakhlani et al., 1997; Hunter et al., 1997; Stone et al., 1997) and indicate that the same receptor comes into play under both acute and persistent pain conditions.

Because the majority of α2A AR in the spinal cord are located on peptide-containing primary afferents neurons that terminate in the dorsal horn (Stone et al., 1999), the antinociceptive action of dexmedetomidine may involve inhibition of peptide release at these terminals. In fact, activation of α2 AR has been shown to reduce capsaicin, potassium and noxious stimulus-evoked release of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide from spinal cord slices or from cultured primary afferent neurons (Kuraishi et al., 1985; Pang & Vasko, 1986; Holz et al., 1989; Takano et al., 1993), probably by an action on N-type calcium channels (Cox & Dunlap, 1992). The antinociceptive effects of dexmedetomidine may, of course, also be mediated by postsynaptic inhibitory mechanisms, via α2 AR that are expressed on nociresponsive projection neurons.

In summary, our studies indicate that none of the α2 AR subtypes are essential for the development of a profound behavioural allodynia after peripheral nerve injury in a mouse model of neuropathic pain. Taken together with our previous results, however, it is possible that the extent to which the sympathetic nervous system contributes to the nerve injury-induced allodynia depends on the genetic background of the particular mouse that is studied. We also found that the antinociceptive effect of dexmedetomidine was abolished in the D79N α2A AR mutant mice, which indicates that the α2A AR is critical for the pain relieving actions of α2 AR agonists in this mouse model of neuropathic pain. Consistent with previous findings, we demonstrated that the anti-allodynic and antinociceptive effects of dexmedetomidine can only be reversed by blocking spinal α2A AR. The fact that an anti-allodynic effect could be produced at much lower doses than were required to produce frank antinociception is of particular interest. Specifically, it may be possible to achieve clinical efficacy in neuropathic pain conditions without the α2A AR-mediated side effects, such as sedation and hypothermia (Hunter et al., 1997), that occur when higher doses are used.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Robin Clark and Michael Spedding for information about RS 42206 and Heather Gilbert for technical assistance. We also thank Dr Lee Limbird for providing the α2A AR mutant mice and Dr Brian Kobilka for the aα2B and α2C AR null mutation mice. This work was supported by DE 08973 and NS 21445 (A.I. Basbaum) and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America Foundation (A.B. Malmberg).

Abbreviations

- AR

adrenergic receptors

- DRG

dorsal root ganglia

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- s.c.

subcutaneous

- +/+

wild-type mice

- −/−

mutant mice

References

- ALI Z., RINGKAMP M., HARTKE T.V., CHIEN H.F., FLAVAHAN N.A., CAMPBELL J.N., MEYER R.A. Uninjured C-fiber nociceptors develop spontaneous activity and adrenergic sensitivity following L6 spinal nerve ligation in monkey. J. Neurophysiol. 1999;81:455–466. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARNER S. Intravenous phentolamine test: diagnostic and prognostic use in reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Pain. 1991;46:17–22. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90028-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIRDER L.A., PERL E.R. Expression of alpha2-adrenergic receptors in rat primary afferent neurones after peripheral nerve injury or inflammation. J. Physiol. 1999;515:533–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.533ac.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BONICA J.J.Causalgia and other reflex sympathetic dystrophies The Management of Pain 1990Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febinger; 220–243.ed. Bonica, J.J. pp [Google Scholar]

- BOULLIN D.J., COSTA E., BRODIE B.B. Discharge of tritium-labeled guanethidine by sympathetic nerve stimulation as evidence that guanethidine is a false transmitter. Life Sci. 1966;5:803–808. [Google Scholar]

- BYLUND D.B., EIKENBERG D.C., HIEBLE J.P., LANGER S.Z., LEFKOWITZ R.J., MINNEMAN K.P., MOLINOFF P.B., RUFFOLO R.J., TRENDLENBURG U. International Union of Pharmacology nomenclature of adrenoceptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 1994;46:121–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAPLAN S.R., BACH F.W., POGREL J.W., CHUNG J.M., YAKSH T.L. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J. Neurosci. Meth. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Y., MICHAELIS M., JÄNIG W., DEVOR M. Adrenoceptor subtype mediating sympathetic-sensory coupling in injured sensory neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1996;76:3721–3730. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHO H.J., KIM D.S., LEE N.H., KIM J.K., LEE K.M., HAN K.S., KANG Y.N., KIM K.J. Changes in the alpha 2-adrenergic receptor subtypes gene expression in rat dorsal root ganglion in an experimental model of neuropathic pain. Neuroreport. 1997;8:3119–3122. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709290-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARK R.D., REPKE D.B., BERGER J., NELSON J.T., KILPATRICK A.T., BROWN C.M., MACKINNON A.C., CLAGUE R.U., SPEDDING M. Structure-affinity relationships of 12-sulfonyl derivatives of 5,8,8A,9,10,11,12,12a,13,13a-decahydro-6h-isoquino[2,1-g][1,6] naphthyridines at alpha-adrenoceptors. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:705–717. doi: 10.1021/jm00106a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARK R.D., SPEDDING M., REDFERN W.S.Preparation of decahydro-8H-isoquino[2,1-g][1,6]naphthyridine and decahydrobenzo[a]pyrrolo[3,2-q]quinolizine derivatives as α2-adrenoceptor antagonist. (Syntex (USA), Inc., USA) Eur. Pat. Appl. 199369CODEN: EPXXDW EP 524004 A1 19930120, Application: EP 92-306553 19920716

- COX D.H., DUNLAP K. Pharmacological discrimination of N-type from L-type calcium current and its selective modulation by transmitters. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:906–914. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-00906.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIS K.D., TREEDE R.D., RAJA S.N., MEYER R.A., CAMPBELL J.N. Topical application of clonidine relieves hyperalgesia in patients with sympathetically maintained pain. Pain. 1991;47:309–317. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90221-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DESMEULES J.A., KAYSER V., WEIL-FUGGAZA J., BERTRAND A., GUILBAUD G. Influence of the sympathetic nervous system in the development of abnormal pain-related behaviours in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Neuroscience. 1995;67:941–951. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEVOR M., JÄNIG W., MICHAELIS M. Modulation of activity in dorsal root ganglion neurons by sympathetic activation in nerve-injured rats. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;71:38–47. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEVOR M., JÄNIG W. Activation of myelinated afferents ending in a neuroma by stimulation of the sympathetic supply in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1981;24:43–47. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90356-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRUMMOND P.D., SKIPWORTH S., FINCH P.M. Alpha 1-adrenoceptors in normal and hyperalgesic human skin. Clin. Sci. 1996;91:73–77. doi: 10.1042/cs0910073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EISENACH J.C., DEKOCK M., KLIMSCHA W. Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists for regional anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:655–674. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199609000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAREED M.U., NOH H.R., CHUNG J.M., DAVAR G.Identification and increased expression of a novel alpha-2 adrenoceptor mRNA in a rat model of experimental painful neuropathy Proc of the 8th World Congress on Pain, Progress in Pain Research and Management 19978Seattle: IASP Press; 539–546.eds. Jensen, T.S., Turner, J.A., Wiesenfeld-Hallin, Z [Google Scholar]

- FISHER B., ZORNOW M.H., YAKSH T.L., PETERSON B.M. Antinociceptive properties of intrathecal dexmedetomidine in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;192:221–225. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90046-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLD M.S., DASTMALCHI S., LEVINE J.D. Alpha 2-adrenergic receptor subtypes in rat dorsal root and superior cervical ganglion neurons. Pain. 1997;69:179–190. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARGREAVES K., DUBNER R., BROWN F., FLORES C., JORIS J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:141–167. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLZ G.G., IV, KREAM R.M., SPIEGEL A., DUNLAP K. G proteins couple alpha-adrenergic and GABAb receptors to inhibition of peptide secretion from peripheral sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 1989;9:657–666. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-02-00657.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNTER J.C., FONTANA D.J., HEDLEY L.R., JASPER J.R., LEWIS R., LINK R.E., SECCHI R., SUTTON J., EGLEN R.M. Assessment of the role of alpha2-adrenoceptor subtypes in the antinociceptive, sedative and hypothermic action of dexmedetomidine in transgenic mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1339–1344. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HYLDEN J.L.K., WILCOX G.L. Intrathecal morphine in mice: a new technique. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1980;67:313–316. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JASPER J.R., LESNICK J.D., CHANG L.K., YAMANISHI S.S., CHANG T.K., HSU S.A., DAUNT D.A., BONHAUS D.W., EGLEN R.M. Ligand efficacy and potency at recombinant alpha-2 adrenergic receptors: agonist-mediated [35S]GTPgammaS binding. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;55:1035–1043. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00631-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JÄNIG W., LEVINE J.D., MICHAELIS M. Interactions of sympathetic and primary afferent neurons following nerve injury and tissue trauma. Prog. Brain Res. 1996;113:161–184. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON E.M., JR, CANTOR E., DOUGLAS J.R., JR Biochemical and functional evaluation of the sympathectomy produced by the administration of guanethidine to newborn rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1975;193:503–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KALSO E.A., POYHIA R., ROSENBERG P.H. Spinal antinociception by dexmedetomidine, a highly selective alpha 2-adrenergic agonist. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1991;68:140–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1991.tb02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM K.J., YOON Y.W., CHUNG J.M. Comparison of three rodent neuropathic pain models. Exp. Brain Res. 1997;113:200–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02450318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM S.H., CHUNG J.M. Sympathectomy alleviates mechanical allodynia in an experimental animal model for neuropathy in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1991;134:131–134. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90524-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM S.H., NA H.S., SHEEN K., CHUNG J.M. Effects of sympathectomy on a rat model of peripheral neuropathy. Pain. 1993;55:85–92. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90187-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KURAISHI Y., HIROTA N., SATO Y., KANEKO S., SATOH M., TAKAGI H. Noradrenergic inhibition of the release of substance P from the primary afferents in rabbit spinal dorsal horn. Brain Res. 1985;359:177–182. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91426-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAKHLANI P.P., MACMILLAN L.B., GUO T.Z., MCCOOL B.A., LOVINGER D.M., MAZE M., LIMBIRD L.E. Substitution of a mutant alpha2a-adrenergic receptor via ‘hit and run' gene targeting reveals the role of this subtype in sedative, analgesic, and anesthetic-sparing responses in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:9950–9955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAVAND'HOMME P., PAN H.L., EISENACH J.C. Intrathecal neostigmine, but not sympathectomy, relieves mechanical allodynia in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:493–499. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199808000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE D.H., CHUNG K., CHUNG J.M. Strain differences in adrenergic sensitivity of neuropathic pain behaviors in an experimental rat model. Neuroreport. 1997;8:3453–3456. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199711100-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINK R.E., DESAI K., HEIN L., STEVENS M.E., CHRUSCINSKI A., BERNSTEIN D., BARSH G.S., KOBILKA B.K. Cardiovascular regulation in mice lacking α2-adrenergic receptor subtypes b and c. Science. 1996;273:803–805. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACMILLAN L.B., HEIN L., SMITH M.S., PIASCIK M.T., LIMBIRD L.E. Central hypotensive effects of the α2a-adrenergic receptor subtype. Science. 1996;273:801–803. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALMBERG A.B., BASBAUM A.I. Partial sciatic nerve injury in the mouse as a model of neuropathic pain: behavioral and neuroanatomical correlates. Pain. 1998;76:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAXWELL R.A., PLUMMEN A.J., SCHNEIDER F., POLAVSKI H., DAMICEL A.I. Pharmacology of [2-(octahydro-1-azovinyl)-ethyl]-guanidine sulfate (guanethidine) J. Pharmacol. 1960;128:22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLACHLAN E.M., JÄNIG W., DEVOR M., MICHAELIS M. Nerve injury triggers noradrenergic sprouting within dorsal root ganglia. Nature (Lond.) 1993;363:543–545. doi: 10.1038/363543a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICHAELIS M., DEVOR M., JÄNIG W. Sympathetic modulation of activity in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons changes over time following peripheral nerve injury. J. Neurophysiol. 1996;76:753–763. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.2.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEIL A., ATTAL N., GUILBAUD G. Effects of guanethidine on sensitization to natural stimuli and self-mutilating behaviour in rats with a peripheral neuropathy. Brain Res. 1991;565:237–246. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91655-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHOLAS A.P., PIERIBONE V., HÖKFELT T. Distributions of mRNAs for alpha-2 adrenergic receptor subtypes in rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1993;328:575–594. doi: 10.1002/cne.903280409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PANG I.H., VASKO V.R. Morphine and norepinephrine, but not 5-hydroxytryptamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid inhibit the potassium-stimulated release of substance P from rat spinal cord slices. Brain Res. 1986;376:268–279. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUKE M.J., LUO L., XU X.J. The spinal analgesic role of alpha 2-adrenoceptor subtypes in rats after peripheral nerve section. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;260:227–232. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAJA S.N., TREEDE R.D., DAVIS K.D., CAMPBELL J.N. Systemic alpha-adrenergic blockade with phentolamine: a diagnostic test for sympathetically maintained pain. Anesthesiology. 1991;74:691–698. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REDDY S.V., MADERDRUT J.L., YAKSH T.L. Spinal cord pharmacology of adrenergic agonist-mediated antinociception. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1980;213:525–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RINGKAMP M., GRETHEL E.J., CHOI Y., MEYER R.A., RAJA S.N. Mechanical hyperalgesia after spinal nerve ligation in rat is not reversed by intraplantar or systemic administration of adrenergic antagonists. Pain. 1999a;79:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RINGKAMP M., ESCHENFELDER S., GRETHEL E.J., HABLER H.J., MEYER R.A., JANIG W., RAJA S.N. Lumbar sympathectomy failed to reverse mechanical allodynia- and hyperalgesia-like behavior in rats with L5 spinal nerve injury. Pain. 1999b;79:143–153. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSIN D.L., TALLEY E.M., LEE A., STORNETTA R.L., GAYLINN B.D., GUYENET P.G., LYNCH K.R. Distribution of alpha 2C-adrenergic receptor-like immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;372:135–165. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960812)372:1<135::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSIN D.L., ZENG D., STORNETTA R.L., NORTON F.R., RILEY T., OKUSA M.D., GUYENET P.G., LYNCH K.R. Immunohistochemical localization of alpha 2A-adrenergic receptors in catecholaminergic and other brainstem neurons in the rat. Neuroscience. 1993;56:139–155. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90569-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SATO J., PERL E.R. Adrenergic excitation of cutaneous pain receptors induced by peripheral nerve injury. Science. 1991;251:1608–1610. doi: 10.1126/science.2011742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SELTZER Z., DUBNER R., SHIR Y. A novel behavioral model of neuropathic pain disorders produced in rats by partial sciatic nerve injury. Pain. 1990;43:205–218. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)91074-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCADDING J. Development of ongoing activity, mechanosensitivity and adrenaline sensitivity in severed peripheral axons. Exp. Neurol. 1981;73:345–364. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(81)90271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHI T.S., WINZER-SERHAN U., LESLIE F., HOKFELT T. Distribution and regulation of alpha(2)-adrenoceptors in rat dorsal root ganglia. Pain. 2000;84:319–330. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00224-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIR Y., SELTZER Z. Effects of sympathectomy in a model of causalgiform pain produced by partial sciatic nerve injury in rats. Pain. 1991;45:309–320. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STONE L.S., BROBERGER C., VULCHANOVA L., WILCOX G.L., HOKFELT T., RIEDL M.S., ELDE R. Differential distribution of alpha2A and alpha2C adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity in the rat spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:5928–5937. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-15-05928.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STONE L.S., MACMILLAN L.B., KITTO K.F., LIMBIRD L.E., WILCOX G.L. The alpha2a adrenergic receptor subtype mediates spinal analgesia evoked by alpha2 agonists and is necessary for spinal adrenergic-opioid synergy. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:7157–7165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-07157.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STONE L.S., VULCHANOVA L., RIEDL M.S., WANG J., WILLIAMS F.G., WILCOX G.L., ELDE R. Effects of peripheral nerve injury on alpha-2A and alpha-2C adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity in the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1999;93:1399–1407. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00209-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SURPRENANT A., HORSTMAN D.A., AKBARALI H., LIMBIRD L.E. A point mutation of the alpha 2-adrenoceptor that blocks coupling to potassium but not calcium currents. Science. 1992;257:977–980. doi: 10.1126/science.1354394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKANO M., TAKANO Y., YAKSH T.L. Release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), substance P (SP), and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) from rat spinal cord: modulation by alpha 2 agonists. Peptides. 1993;14:371–378. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(93)90055-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKANO Y., YAKSH T.L. Characterization of the pharmacology of intrathecally administered alpha-2 agonists and antagonists in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;261:764–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAMSEN A., GORDH T. Epidural clonidine produces analgesia. Lancet. 1984;2:231–232. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRACEY D.J., CUNNINGHAM J.E., ROMM M.A. Peripheral hyperalgesia in experimental neuropathy: mediation by a2-adrenoreceptors on post-ganglionic sympathetic terminals. Pain. 1995;60:317–327. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLENBRING S., BEAUPRIE I.G., DELEO J.A. Sciatic cryoneurolysis in rats: a model of sympathetically independent pain, Part 1: Effects of sympathectomy. Anesth. Analg. 1995;81:544–548. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199509000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIAO X.H., RAND M.J. Effects of the alpha 2-adrenoceptor agonist UK14304 on pressor responses in pithed rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1990;17:725–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1990.tb01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIE Y., ZHANG J., PETERSEN M., LAMOTTE R.H. Functional changes in dorsal root ganglion cells after chronic nerve constriction in the rat. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;73:1811–1820. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.5.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAKSH T.L. Pharmacology of spinal adrenergic systems which modulate spinal nociceptive processing. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1985;22:845–858. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAKSH T.L., POGREL J.W., LEE Y.W., CHAPLAN S.R. Reversal of nerve ligation-induced allodynia by spinal alpha-2 adrenoceptor agonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;272:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]