Abstract

The synthesis of a tritiated benzopyran-type opener of the ATP-dependent K+ channel (KATP channel), [3H]-PKF217 – 744 {(3S,4R)-N-[3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-3-hydroxy-6-(2-methyl-4-pyridinyl)-2H-1-benzopyran-4-yl]-3-[2,6-3H]pyridinecarboxamide} with a specific activity of 50 Ci mmol−1 is described. Binding of the ligand was studied in membranes from human embryonic kidney cells transfected with the sulphonylurea receptor isoforms, SUR2B and SUR2A, respectively.

PKF217 – 744 was confirmed as being a KATP channel opener by its ability to open the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel, the recombinant form of the vascular KATP channel, and to inhibit binding of the pinacidil analogue, [3H]-P1075, to SUR2B (Ki=26 nM).

The kinetics of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B was described by rate constants of association and dissociation of 6.9×106 M−1 min−1 and 0.09 min−1, respectively.

Binding of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 to SUR2B/2A was activated by MgATP (EC50≈3 μM) and inhibited (SUR2B) or enhanced (SUR2A) by MgADP.

Binding of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 to SUR2B was inhibited by representatives of the different structural classes of openers and sulphonylureas. Ki values were identical with those obtained using the opener [3H]-P1075 as the radioligand.

Glibenclamide accelerated dissociation of the SUR2B-[3H]-PKF217 – 744 complex.

The data show that the affinity of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B is ≈6 times lower than that of [3H]-P1075. This is due to a surprisingly slow association rate of the benzopyran-type ligand, suggesting a complex mechanism of opener binding to SUR. The other pharmacological properties of the two opener radioligands are identical.

Keywords: KATP channel; sulphonylurea receptors SUR2A and SUR2B; KATP channel opener binding; [3H]-PKF217 – 744, [3H]-P1075, nucleotide regulation of opener binding

Introduction

ATP-dependent K+ channels (KATP channels) are a class of K+ channels which are gated by the intracellular ATP/ADP ratio and couple the metabolic state of the cell to membrane potential and excitability (Ashcroft & Ashcroft, 1990; Edwards & Weston, 1993). KATP channels are the target of the hypoglycaemic sulphonylureas (SUs) which close the channel preferentially in the pancreatic β-cell to promote insulin secretion; they are activated by the K+ channel openers (KCOs), a class of drugs with multiple therapeutic applications (see below) (Edwards & Weston, 1993; Lawson, 1996; Quast, 1996).

KATP channels are composed of two types of subunits, inwardly rectifying K+ channels (Kir6.x) and sulphonylurea receptors (SURs), arranged as a heterooctamer with 4 : 4 stoichiometry of the subunits (reviews: Ashcroft & Gribble, 1998; Aguilar-Bryan & Bryan, 1999; Seino, 1999). The four Kir6.x subunits contribute to formation of the pore and, in case of Kir6.2, also mediate the high affinity inhibition of the channel by ATP (Tucker et al., 1997; Tanabe et al., 1999). SUR is a member of the ATP-binding cassette protein superfamily (Aguilar-Bryan et al., 1995; Sakura et al., 1995) and carries binding sites for nucleotides (Ueda et al., 1997; 1999), for the SUs and for the KCOs (Aguilar-Bryan et al., 1995; Hambrock et al., 1998; Schwanstecher et al., 1998). Two subtypes of SUR have been characterized. SUR1 is mainly found in pancreatic β-cells and in brain (Aguilar-Bryan et al., 1995; Sakura et al., 1995). SUR2 is expressed in muscle with the isoform SUR2A being found in skeletal and cardiac muscle (Inagaki et al., 1996) and the isoform SUR2B in smooth muscle (Isomoto et al., 1996). SUR1 has high affinity for the SUs and low affinity for most KCOs; the converse is true for the SUR2 isoforms (Hambrock et al., 1998; 1999; Schwanstecher et al., 1998; Dörschner et al., 1999; Russ et al., 1999). The properties of the KATP channels in the different tissues are determined also by the Kir6.x subunit (reviews: Babenko et al., 1998; Ashcroft & Gribble, 1998; Seino, 1999). The KATP channel in vascular smooth muscle consists of Kir6.1+SUR2B (Yamada et al., 1997), that in other smooth muscle of Kir6.2+SUR2B (Isomoto et al., 1996); the KATP channels in heart and skeletal muscle contain Kir6.2+SUR2A (Inagaki et al., 1996).

The KCOs are a heterogenous group of compounds which include benzopyrans such as levcromakalim, and the cyanoguanidines such as pinacidil and P1075, as well as several other groups (Edwards & Weston, 1994; Evans & Stemp, 1996). They are compounds of great therapeutic interest (Evans & Stemp, 1996; Lawson, 1996) having potential for diseases as diverse as asthma (Fozard & Manley, 2000), urogenital dysfunction (Brading & Turner, 1996), cardiac ischaemia (Grover & Garlid, 2000) and hair growth (Lawson, 1996). A major problem in developing therapeutic agents has been the limited tissue selectivity of the KCOs, since the dominant systemic effect of most KCOs is to lower peripheral resistance and blood pressure (Edwards & Weston, 1994; Lawson, 1996; Quast, 1996). However, with the availability of recombinant KATP channels, the interaction of KATP channel openers with the different Kir6.x/SURx combinations can be studied in unprecedented detail. Progress has been made in defining the binding sites of various openers on SUR2 (Babenko et al., 2000; D'hahan et al., 1999a; Uhde et al., 1999) and the nucleotide regulation of KCO binding and channel opening has been elucidated in considerable detail (Schwanstecher et al., 1998; D'hahan et al., 1999b; Hambrock et al., 1999; Gribble et al., 2000).

For studies on the mechanism of action of the KCOs, the combination of electrophysiological and radioligand binding studies (using suitably tailored KATP channels or channel subunits) constitutes a promising approach. Pharmacologically meaningful binding of openers has been described using the tritiated pinacidil analogue, [3H]-P1075 (Bray & Quast, 1992; Manley et al., 1993; Quast et al., 1993). However, little has been forthcoming from benzopyran (cromakalim)-type radioligands, although (preliminary) reports on such compounds have appeared (Howlett & Longman, 1992; De keczer & Parnes, 1995). It was therefore of interest to synthesise a potent tritiated ligand belonging to the benzopyran class of openers. We show here that PKF217 – 744 [(3S,4R)-N[3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-3-hydroxy-6-(2-methyl-pyridin-4-yl)-2H-1-benzopyran]-3-pyridinecarboxamide] opens the recombinant form of the vascular KATP channel, Kir6.1/SUR2B, and characterize the binding of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 to SUR2B and 2A. The data show that the new radioligand is a potent and useful new tool for the study of the interactions of the openers with SUR2.

Methods

Preparation of [3H]-PKF217 – 744

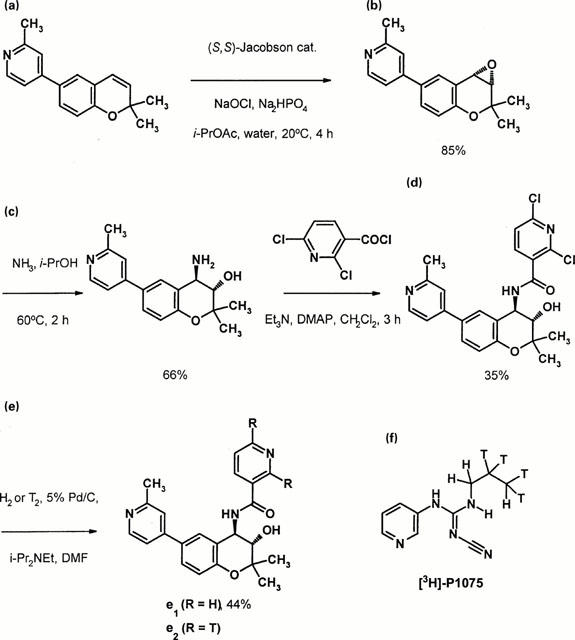

The synthetic route to [3H]-PKF217 – 744 is depicted in Figure 1. (3S, 4R)-I, 4-amino-3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-6-(2-methyl-4-pyridinyl)-2H-1-benzopyran-3-ol (c) was prepared as follows: a mixture of aqueous sodium hypochlorite (90 ml of 13%, in deionized water) and aqueous sodium phosphate, dibasic (135 ml of 0.05 M) was added dropwise to a stirred mixture of 4-(2,2-dimethyl-2H-1-benzopyran-6-yl)-2-methylpyridine (a; 10.6 g, 40 mmol) and (S,S)-(+)-N,N′-bis-(3,5-di-tert-butylsalicylidene)-1,2-cyclohexanediaminomanganese(III)chloride (1.4 g, 2 mmol) in isopropylacetate (135 ml) at 25°C. The mixture was stirred for 90 min, filtered and extracted with ethyl acetate (2×50 ml). The combined extracts were dried (Na2SO4), filtered and the solvent evaporated off. The residue was purified by chromatography (silica gel, 50% ethyl acetate in hexane) to give the epoxide (b) as an oil. The oil was then treated with a saturated solution of ammonia in isopropanol (300 ml) and heated at 85°C in an autoclave for 18 h. The solvent was evaporated off under reduced pressure to give a residue which was dissolved in ethanol (230 ml) and treated with a solution of (L)-tartaric acid (6.0 g, 40 mmol) in water (115 ml) to give the product (c) as a crystalline tartrate salt (11.4 g).

Figure 1.

(a) – (e): Synthetic route to [3H]-PKF217 – 744 (see Methods) and (f): structure of [3H]-P1075.

Preparation of (3S,4R)-2,6-dichloro-N-[3,4-dihydro-3-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl -6 -(2-methyl-4-pyridinyl) -2H -1-benzopyran-4-yl]-3-pyridinecarboxamide (d). The tartrate salt (c; 2.2 g, 5 mmol) was treated with an aqueous solution of ammonia (40 ml of 6%) and extracted with dichloromethane (3×20 ml). The combined extracts were dried (Na2SO4) and treated with triethylamine (1.7 ml, 12.5 mmol), followed by a solution of 2,6-dichloro-3-pyridinecarbonyl chloride (1.1 g, 5 mmol) in dichloromethane (20 ml). The mixture was stirred for 2 h at 20°C and the resulting product was filtered and recrystallized from ethanol-water, to give the product (d) as a colourless crystalline solid (0.81 g), m.p. 210 – 212°C, [α]20D+46.9° (c=0.5155, EtOH).

(3S,4R)-N-[3,4-dihydro-3-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-6-(2-methyl-4 - pyridinyl) - 2H - 1 - benzopyran - 4-yl]-3-pyridinecarboxamide (e1). A solution of the dichloride (d; 0.457 g, 1.0 mmol) and ethyldiisopropylamine (0.343 ml) in dimethylformamide (10 ml) was hydrogenated at room temperature and atmospheric pressure over 5% palladium on carbon. Hydrogen uptake was complete after 4 h. The catalyst was removed by filtration and the solvent was evaporated to give a residue. The residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate (20 ml), washed with water (2×10 ml), dried (Na2SO4) and the solvent was evaporated to give a residue, which was recrystallised from ethyl acetate - hexane to give the product as a colourless crystalline solid (0.17 g), m.p. 242 – 244°C, [α]20D +17.5° (c=1.00, EtOH).

Tritiation: (3S, 4R)-N-[3,4-dihydro-3-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-6-(2-methyl-4-pyridinyl)-2H-1-benzopyran-4-yl]-3-[2,6-3H2]pyridinecarboxamide (e2). A solution of the dichloride (d; 10 mg, 21.9 μmol) and ethyldiisopropylamine (9 μl, 40.3 μmol) in dimethylformamide (0.6 ml) was reacted with labelled tritium gas (12.8 ml, 32.7 Ci) at 23°C and at a pressure of 869 mbar over 10% palladium on carbon (10 mg). The tritium uptake was complete after 110 min. After lyophilization the residue was dissolved in methanol and lyophilized once more. In order to re-exchange labile tritium completely this procedure was repeated three times. The resulting crude material (1.1 Ci) was purified by flash chromatography (silica gel 0.04 – 0.063 mm, dichloromethane : methanol 100 : 5) to obtain 586 mCi of tritiated PKF217 – 744 at a radiochemical purity >98% determined by HPLC. The specific activity was determined with 50.2 Ci mmol−1 by MS-spectroscopy. [3H]-NMR spectroscopy gave evidence that >95% of the label is attached to the positions 2 and 6. In order to minimize radiochemical induced decomposition [3H]-PKF217 – 744 was dissolved in ethanol at a specific activity of 1.05 mCi ml−1 and stored at −20°C under exclusion of light.

Cell culture, transfection and membrane preparation

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were cultured as described previously (Hambrock et al., 1998; 1999) in Minimum Essential Medium containing glutamine and supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum and 20 μg ml−1 gentamycin. Cell lines stably expressing the coding sequence of murine SUR2A or SUR2B (GenBank accession numbers D86037 and D86038, respectively; Isomoto et al., 1996) were isolated as described previously (Hambrock et al., 1998; 1999); 5 days prior to membrane preparation, the antibiotic was withdrawn. For patch clamp experiments, cells were transiently cotransfected with SUR2B+murine Kir6.1 (GenBank accession number D88159; Yamada et al., 1997) at a molar plasmid ratio of 1 : 1 using lipofectAMINE and OPTIMEM (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. pEGFP-C1 vector (Clontech), encoding for green fluorescent protein (GFP), was added for easy identification of transfected cells (Russ et al., 1999). Cells were allowed to express transfected DNA for 48 h and were then used for electrophysiological experiments.

For membrane preparation (Hambrock et al., 1998), cells were centrifuged for 6 min at 500×g at 37°C and lysed by addition of ice-cold hypotonic buffer containing (in mM): HEPES 10, EGTA 1 at pH 7.4. The lysate was centrifuged at 105×g and 4°C for 60 min and the resulting membrane pellet was resuspended in a buffer containing (in mM) HEPES 5, KCl 5, NaCl 139 at pH 7.4 and 4°C at a protein concentration of ≈3.0 mg ml−1 (SUR2A) or ≈1.5 mg ml−1 (SUR2B) and frozen at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined according to Lowry et al. (1951) using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Kinetics of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding

Membranes were thawed and homogenized with a polytron homogenizer for 2×5 s at 104 r.p.m. and 4°C. To measure the association kinetics, membranes (final protein concentration: 50/300 μg ml−1 for SUR2B/2A) were added to the incubation buffer containing (in mM): NaCl 139, KCl 5, HEPES 5, MgCl2 2.2, Na2ATP 1 (free [Mg2+]≈1 mM) and supplemented with [3H]-PKF217 – 744 (3 – 30 nM) at 37°C. Aliquots (300 μl) were withdrawn at different times for separation of bound and free ligand by dilution into 8 ml of quench solution (50 mM TRIS, 154 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, 0°C) and rapid filtration under vacuum over Whatman GF/B filters. Filters were washed twice with 8 ml of quench solution at 0°C and counted for 3H in the presence of 6 ml of scintillant (Ultima Gold; Packard). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM unlabelled PKF217 – 744 and did not change with time.

Assuming a simple bimolecular association reaction with the label concentration (L) in large excess over the concentration of binding sites, a single exponential as function of time (t) was fitted to the data,

Here Beq denotes the concentration of the receptor-label complex at equilibrium, kapp the apparent rate constant of association and k+, k−, the rate constants of association and dissociation, respectively (Tallarida, 1995). KD=k− k+−1 is the equilibrium dissociation constant.

Dissociation was initiated by addition of PKF217 – 744 (10 μM)+glibenclamide (0=solvent (dimethyl sulphoxide+ethanol 1 : 1, 0.1%), 3.5 – 10 μM) to the receptor-label complex, which was prepared by incubation of the membrane preparation with [3H]-PKF217 – 744 (7/15 nM for SUR2B/2A, respectively) at 37°C for 30/13 min. Aliquots (0.3 ml) were withdrawn to follow the dissociation kinetics to which the equation of exponential decay was fitted,

with Beq and k− defined as above.

Equilibrium competition experiments

Membranes (SUR2B/2A: 200/350 μg protein ml−1) were added to the incubation buffer described above containing [3H]-PKF217 – 744 (7/17 nM for SUR2B/2A, respectively) and the inhibitor of interest in a total volume of 1 ml at pH 7.4 and 37°C. After 30/13 min, incubation was stopped by diluting 0.3 ml aliquots in triplicate into 8 ml of quench solution at 0°C and filtration as described above. [3H]-P1075 binding experiments to SUR2B/2A were performed as above using a radioligand concentration of 2/3 nM and a protein concentration 0.13/0.25 mg ml−1.

Concentration dependencies were analysed by fitting the logistic form of the Hill equation,

to the data. Here b denotes the starting level of the curve and a the level at saturation so that a−b represents the extent of the effect (amplitude). n (=nH) is the Hill coefficient, x the concentration of the compound under study and K the midpoint of the curve with px=−logx and pK=−logK. The dependence of the midpoint of an inhibition curve (IC50 value) on the concentration of the radioligand, L, was calculated according to the Cheng & Prusoff (1973) equation,

where Ki is the inhibition constant and KD the equilibrium dissociation constant of the radioligand. The concentration of binding sites of the radioligand (Bmax) was estimated from the specific binding (BS) at the radioligand concentration L in the absence of competitor according to the Law of Mass Action:

The dependence of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 on MgATP concentration was measured in the presence of [Mg2+]free≈1 mM. In case that an ATP-regenerating system was coupled, creatine kinase (5 u ml−1) and creatine phosphate (3 mM) were added in the presence of 10 mM Mg2+ as described in Hambrock et al. (1999).

Patch-clamp experiments

The patch-clamp technique was used in the cell-attached configuration as described by Hamill et al. (1981). Patch pipettes were drawn from filament borosilicate glass capillaries (GC 150F-15, Clark Electromedical Instruments, Pangbourne, U.K.) and heat polished using a horizontal microelectrode puller (Zeitz, Augsburg, Germany). Bath and pipette were filled with a high K+-Ringer solution containing (in mM): KCl 142, NaCl 2.8, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 1, D(+)-glucose 11, HEPES 10, titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH at 22°C. After filling with buffer, pipettes had a resistance of 3 – 5 MΩ. Data were recorded with an EPC 9 (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany) amplifier using the ‘Pulse' software (HEKA). Isolated HEK cells showing GFP fluorescence were clamped to −80 mV and signals were filtered at 200 Hz and sampled with 1 kHz, using the 4-pole Bessel filter of the EPC9 amplifier. For the amplitude histograms 30 segments of 2 s duration were used; bin-width was 50 fA with 200 bins from −10 pA to 0 pA. The data were analysed using the Gaussian function with two or three components. The open probability (popen) was estimated from the amplitude histograms (Colquhoun & Sigworth, 1995).

Rat portal vein

Spontaneous activity of rat portal vein was measured as described in Buchheit et al. (2000). In brief, portal veins from male Wistar rats were mounted in a thermostated perfusion chamber and perfused with a buffered saline solution at 37°C and pH 7.4 at a rate of 2.5 ml min−1. The saline was continuously gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2 and contained (in mM): NaCl 120, KCl 5, NaHCO3 15, NaH2PO4 1.2, MgCl2 1.2, CaCl2 2.5, glucose 11 and HEPES 20. After a 30 min equilibration period at a preload of 500 mg, PKF217 – 744 was applied for 10 – 30 min until steady state was reached and washed out for 30 min; the cycle was repeated several times with a higher concentration. Force was measured with an isometric force transducer connected to a home-built amplifier from which the signal was transmitted to an integrator and a pen recorder.

Data analysis

Individual binding experiments were analysed by fitting equations 1, 2 and 3 to the data according to the method of least squares using the FigP programme (Biosoft, Cambridge, U.K.). Errors in the parameters derived from the fit to a single curve were estimated using the univariate approximation (Draper & Smith, 1981) and assuming that amplitudes and pK values are normally distributed (Christopoulos, 1998). In the text, pK±s.e.mean or K values with the 95% confidence interval in parentheses are given. Propagation of errors was taken into account according to Bevington (1969).

Materials

[3H]-P1075 (specific activity 117 Ci mmol−1) was purchased from Amersham Buchler (Braunschweig, Germany). The reagents and media used for cell culture and transfection were from Life Technologies (Eggenstein, Germany). Na2ATP was from Boehringer Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany) and creatine phosphate and creatine kinase from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany). The following drugs were kind gifts of the pharmaceutical companies given in parentheses: aprikalim (Aventis, Paris, France), AZ-DF 265 (4-[[N-(α-phenyl-2-piperidino-benzyl) carbamoyl]methyl] benzoic acid (Thomae, Biberach, Germany), diazoxide (Essex Pharma, München, Germany), levcromakalim (SmithKline-Beecham, Harlow, U.K.), nicorandil (Chugai, Tokyo, Japan), P1075 (N-cyano-N′-(1, 1-dimethylpropyl)-N′′-3-pyridylguanidine; Leo Pharmaceuticals, Ballerup, Denmark). Minoxidil sulphate and the active enantiomer of pinacidil ((−)-pinacidil) were synthesized at Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland. Glibenclamide was from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany). KATP channel modulators were dissolved in ethanol+dimethyl sulphoxide (1 : 1) and further diluted with the same solvent or with incubation buffer; the final solvent concentration in the assays was below 0.3%.

Results

Characterization of PKF217 – 744 as a KCO

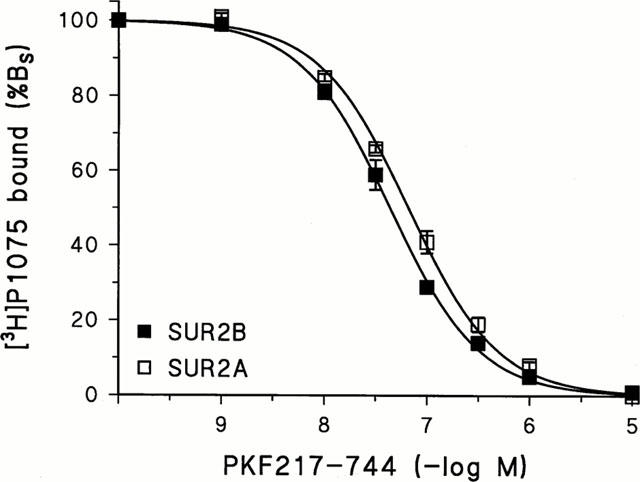

Initially we examined the ability of PKF217 – 744 to interfere with the binding of the selective KCO, [3H]-P1075 (Bray & Quast, 1992, Manley et al., 1993), to the vascular and cardiac subtypes of the sulphonylurea receptor, SUR2B and SUR2A. Figure 2 shows that PKF217 – 744 inhibited [3H]-P1075 binding to SUR2B and 2A completely, with Ki values of 26 (24,29) and 50 (44,58) nM, respectively (confidence intervals in parentheses) and Hill coefficients close to 1.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of [3H]-P1075 binding to SUR2B and SUR2A by PKF-217 – 744. The fit of the Hill equation to the data gave for SUR2B/2A, respectively: plC50=7.35±0.01/7.18±0.02 and nH=0.96±0.02/0.92±0.03. Experiments were performed at 37°C in the presence of 1 mM MgATP and ≈1 mM [Mg2+]free; [3H]-P1075 concentration was 2/3 nM and protein concentration 0.13/0.25 mg ml−1. 100% specific binding (Bs) corresponded to 200/80 fmol mg−1. Data are means±s.e.mean from four experiments. The KD values of [3H]-P1075 binding to SUR2B/2A used for the Cheng-Prusoff correction were 4.4/16.6 nM (Hambrock et al., 1998; 1999).

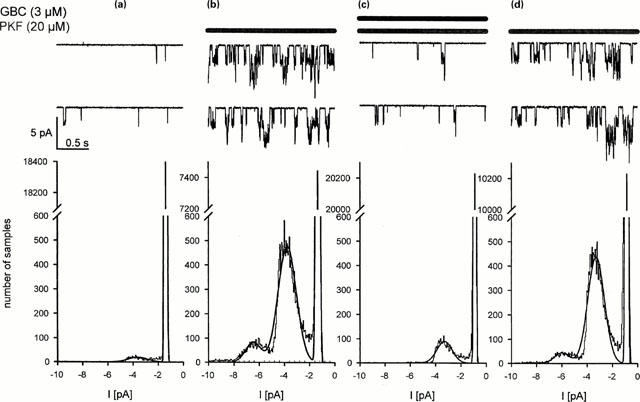

The channel opening ability of the compound was examined in patch clamp experiments in the cell-attached mode using HEK cells expressing the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel. Figure 3 shows a typical recording out of seven such experiments. Under control conditions, little channel activity was seen (popen=0.01). Addition of PKF217 – 744 (20 μM) to the bath induced considerable channel activity (popen≈0.37); there were at least three channels in the patch. From the current peaks in the histogram (ΔI≈ 2.4 pA at a holding potential of −80 mV), the unitary conductance of the channel was estimated to ≈30 pS i.e. exactly the value described for the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel at high symmetrical K+ concentrations (Yamada et al., 1997). Addition of glibenclamide (3 μM) in the continued presence of PKF217 – 744 (20 μM) inhibited channel activity by 86%. After washout of the drugs for 6 min, a second application of PKF217 – 744 induced channel activity to a similar extent as the first stimulation (popen≈0.29; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

PKF217 – 744 opens the Kir6.1/SUR2B channel. Recording in the cell-attached mode from a patch held at −80 mV with [K+]=142 mM in the pipette and at 22°C. In each section, the recording is continuous. (a) Control; (b) 5 min after superfusion with PKF217 – 744 (PKF, 20 μM); (c) 4 min after superfusion with glibenclamide (GBC, 3 μM) in the presence of PKF; (d) after 6 min washout of glibenclamide by PKF127 – 744 (20 μM). Lower panels: Analysis of channel activity by histograms. From the distance between the current peaks (2.4 pA at −80 mV) one calculates a unitary conductance of 30 pS.

KCOs relax blood vessels in the same concentration range in which binding to the channel is observed (Quast et al., 1993). PKF217 – 744 was no exception to this rule and inhibited spontaneous activity of rat portal vein completely with an EC50 value of 8 (7,9) nM and Hill coefficient 2.3±0.3. Like other benzopyrans, the compound inhibited the frequency of the spontaneous contractions more than their amplitude (n=5, data not shown).

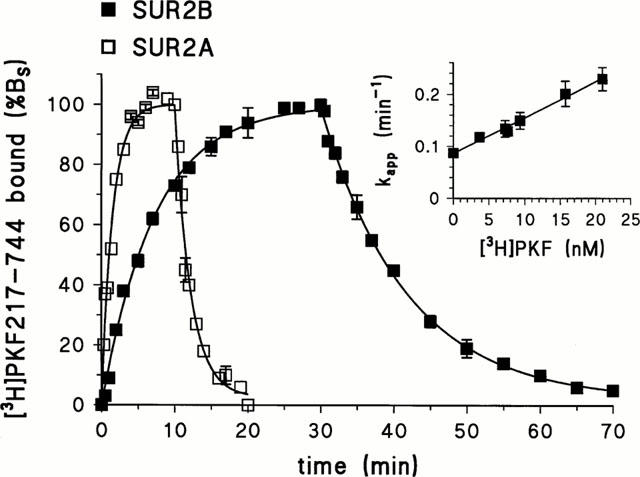

Kinetics of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B/2A

Figure 4 illustrates the association and dissociation kinetics of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B and SUR2A at 37°C. For SUR2B, the rate constant of dissociation, k−, was determined to be 0.087±0.003 min−1, corresponding to a half-time (T1/2) of 8±1 min; the apparent rate constant of association, kapp, at 7.4 nM [3H]-PKF214 – 744 was 0.133±0.003 min−1. Assuming a one step bimolecular binding mechanism, the rate constant of association, k+, was calculated according to eqn (1) to (6.1±1,0) 106 M−1 min−1, where the laws of error propagation were taken into account (Bevington, 1969). This value is unusually slow for a second order association rate constant (see Discussion). In order to test whether the kinetics followed equation (1) over a larger concentration range, the association kinetics were measured at ligand concentrations varying from 3.7 to 21 nM; at higher concentrations the kinetics were too fast to be reliably followed. Within this limited concentration range, kapp varied linearly with ligand concentration (Figure 4, inset). The straight line extrapolated to an ordinate intercept (=k−) of 0.086±0.004 min−1 with a slope (=k+) of (6.9±0.3) 106 M−1 min−1. From these kinetic values, the KD value was calculated as 12±1 nM.

Figure 4.

Kinetics of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B and SUR2A. Association was started by adding membranes to incubation solution containing [3H]-PKF217 – 744 at 7.4 or 15 nM for SUR2B or 2A, respectively. Dissociation was induced after 30/13 min by addition of unlabelled PKF217 – 744 (10 μM)+glibenclamide at various concentrations (SUR2B) or by PKF alone (SUR2A). 100% binding corresponded to approximately 400/250 fmol mg−1 for SUR2B/2A, respectively. Experiments were performed four times giving similar results. Inset: Dependence of kapp for [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B on radiolabel concentration. The fit of equation (1) in Methods to the data gave the values for k− and k+ cited in the text.

The kinetics of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2A were considerably faster (Figure 4). k− was determined to 0.48±0.04 min−1, corresponding to T1/2=1.5±0.1 min. At 15 nM radioligand, kapp was 0.66±0.03 min−1. Applying equation (1), k+ was calculated to (1.2±0.3) 107 M−1min−1, which is about two times faster than the corresponding rate constant for association with SUR2B. From these values, a KD value of 40±10 nM was calculated.

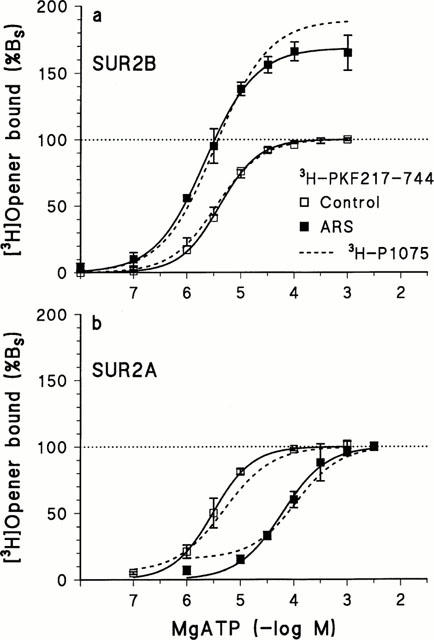

Nucleotide dependence of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding

Binding of the opener [3H]-P1075 to SUR2A and 2B requires the presence of MgATP (Hambrock et al., 1998; Schwanstecher et al., 1998) and is modulated in opposite directions by MgADP, which is stimulatory in the case of SUR2A and inhibitory for SUR2B (Hambrock et al., 1999). Figure 5 shows that this holds true also for [3H]-PKF217 – 744 as the radioligand. [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B and 2A was activated by MgATP with EC50 values of 4.0 (2.8,5.8) and 3.0 (1.7,5.5) μM, respectively, and Hill coefficients ≈1.0. In the presence of an ATP-regenerating system which reduces the amount of ADP formed during incubation (Hambrock et al., 1999), [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B was increased by 70%; the midpoint of the binding curve remained unchanged. In case of SUR2A, however, the ATP-regenerating system left maximum binding unchanged and shifted the binding curve to the right by a factor of 26; (Figure 5). These effects are very similar to those observed previously with [3H]-P1075 as the radioligand (Hambrock et al., 1999).

Figure 5.

Dependence of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B and 2A on MgATP concentration and the effect of an ATP-regenerating system (ARS). (a) SUR2B: In the absence/presence of ARS, ATP activated binding of the radioligand to SUR2B with pEC50 values of 5.40±0.08/5.63±0.12; amplitudes were 100/168±3% and Hill coefficients 1.19±0.07/1.14±0.13, respectively. (b) SUR2A: ATP activated binding with pEC50=5.51±0.08/4.21±0.03 and nH=1.18±0.7/1.16±0.12 in the absence/presence of ARS, respectively. The broken curves represent the fitting curves obtained earlier with [3H]-P1075 (Hambrock et al., 1999). Membranes (SUR2B/2A) were incubated with [3H]-PKF217 – 744 (7/17 nM) for 30/13 min at 37°C in the presence of 1.2 mM [Mg2+]free; n=4 for each point. The ATP-regenerating system consisted of creatine phosphate (3 mM), creatine kinase (5 u ml−1), Mg2+ (10 mM) in the presence of 10 mM HEPES. Data were normalized with respect to specific binding at 1 mM ATP which was 250/123 fmol mg−1 protein for SUR2B/A, respectively.

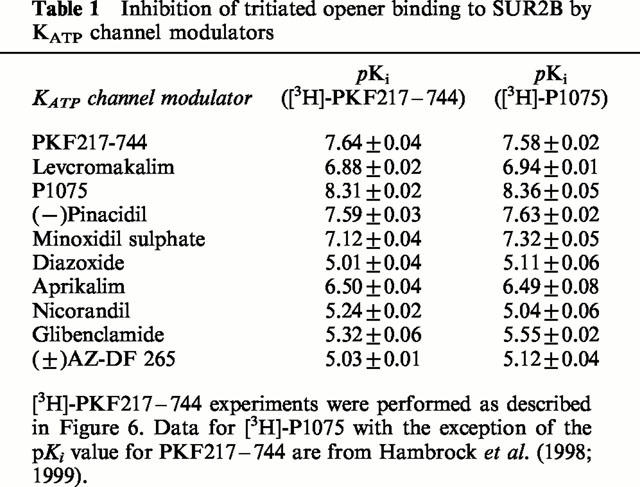

Pharmacological properties of the [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding site

In equilibrium competition experiments, it was evaluated whether structurally different KATP channel modulators were able to interfere with binding of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 to SUR2B. Figure 6 illustrates that unlabelled PKF217 – 744 displaced its tritiated counterpart with Ki=KD=21 (20,22) nM. Using this KD value for the estimation of the number of binding sites for PKF217 – 744 according to equation (5) in Methods gave Bmax=782±78 fmol mg−1. This agrees well with the value of 709±61 fmol mg−1, estimated from [3H]-P1075 binding experiments shown in Figure 2 and using a KD value for P1075 of 4.4 nM (Hambrock et al., 1998). Figure 6 also shows heterologous competition experiments with P1075, minoxidil sulphate and glibenclamide. The pKi values derived from these experiments are listed in Table 1 together with those of other KATP channel modulators. In all cases, the inhibition curves exhibited a Hill coefficient ≈1 and reached 100% inhibition. The exception was minoxidil sulphate which inhibited binding only by 80±1%, similar to the result obtained previously with [3H]-P1075 (Hambrock et al., 1998). Table 1 also lists the pKi values obtained earlier with [3H]-P1075 as the radioligand (Hambrock et al., 1999). Both radioligands give identical results and linear correlation analysis shows that the correlation line coincides with the line of identity (not illustrated). In the case of binding to SUR2A, homologous competition experiments with [3H]-PKF217 – 744 gave a Ki (=KD) value of 50 (44,58) nM in good agreement with the value obtained from the kinetic experiments in Figure 4.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B by selected KATP channel modulators. Data are means±s.e.mean from four experiments. The fit of the logistic equation to the data and the correction for the presence of the radiolabel gave the pKi values listed in Table 1; Hill coefficients were close to 1. Note that maximum inhibition by minoxidil sulphate was only 80±1%. Inhibition of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 (7 nM) binding was studied in the presence of the inhibitor of interest at 1 mM ATP and a free Mg2+ concentration of 1 mM. 100% Bs corresponded to 230 fmol mg−1 protein and nonspecific binding amounted to 26±1% of total binding.

Table 1.

Inhibition of tritiated opener binding to SUR2B by KATP channel modulators

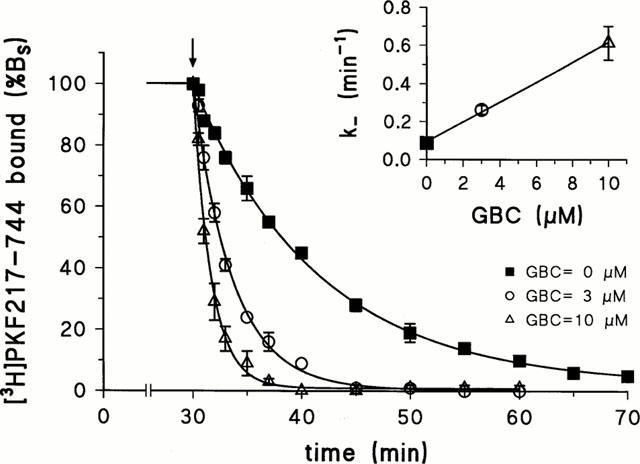

Earlier studies in rat aortic strips (Bray & Quast, 1992) and in membranes containing recombinant SUR2B (Hambrock et al., 1998) have shown that glibenclamide, at concentrations above its Ki value against [3H]-P1075 binding, accelerated the dissociation of [3H]-P1075 from its binding site. Figure 7 shows that this holds true also when [3H]-PKF217 – 744 is used as the radioligand. The effect of glibenclamide is concentration-dependent and shows no saturation up to 10 μM; higher concentration could not be tested since the kinetics became too rapid to be followed by the filtration assay.

Figure 7.

Effect of glibenclamide on the dissociation kinetics of the SUR2B-[3H]-PKF217 – 744 complex. Dissociation was initiated after 30 min equilibration time by addition of PKF217 – 744 (10 μM)+glibenclamide (GBC) at the concentration indicated. Inset: Dependence of the dissociation rate constant on glibenclamide concentration (n=3 – 4 per point). Conditions were as in Figure 4.

Discussion

PKF217 – 744 as a KATP channel opener

The benzopyran PKF217 – 744 is a typical KCO based upon the following evidence: Firstly, in HEK cells transfected with Kir6.1+SUR2B, the compound opened a 30 pS channel in a glibenclamide sensitive manner as expected for the recombinant vascular KATP channel (Yamada et al., 1997). Secondly, PKF217 – 744 inhibited spontaneous activity of rat portal vein with the same characteristic features as observed with cromakalim (effect more on frequency than on amplitude, steep Hill coefficient; Quast, 1987; Hof et al., 1988) and in exactly the concentration range where it was active in the binding assays on SUR2B. This is typical for a wide range of KCOs (Quast et al., 1993). Thirdly, PKF217 – 744 inhibited binding of the established KCO, [3H]-P1075, to SUR2B with Hill coefficient 1. Finally, the pharmacological properties of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B and the nucleotide regulation of binding to the two SUR2 isoforms were identical with those obtained using [3H]-P1075 as the radioligand (Hambrock et al., 1998; 1999; Schwanstecher et al., 1998).

The affinity of PKF217 – 744 for binding to SUR2B is ≈20 nM as determined from homologous competition with its tritiated analogue, from the binding kinetics and from heterologous competition experiments using [3H]-P1075. Hence, PKF217 – 744 is ≈6 times more potent than levcromakalim, a prototype benzopyran opener (Table 1); in fact it is one of the most potent benzopyrans synthesised (rilmakalim: 5 nM; bimakalim: 10 nM; Mannhold et al., 1996). Hence, it was of interest to prepare tritiated PKF217 – 744 and to compare its binding properties to those of the cyanoguanidine [3H]-P1075.

Binding sites of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 and [3H]-P1075

Both radioligands give identical results concerning major aspects of opener binding to SUR2B and 2A. This holds true for both the modulation of binding by MgATP and MgADP and for the sensitivity of SUR2B towards the different openers and towards the blockers glibenclamide and AZ-DF 265 (a benzoate analogue of the SUs). This identity of results suggests that the coupling of the binding site(s) for the two openers to the nucleotide binding sites and the SU site on SUR2 is the same. Therefore, one may speculate that the binding sites of the two openers on SUR2 overlap to a great extent. In support of this, elements of a common pharmacophore of benzopyrans and cyanoguanidines have been proposed (Atwal, 1992; Evans & Stemp, 1996). On the other hand, it is clear that the binding sites of the two openers cannot be identical. Obviously, PKF217 – 744 is a bigger molecule than P1075 (Figure 1). The structure-function relationships within the benzopyrans (Evans & Stemp, 1996) suggest that the large substituents in positions 4 and 6 of the benzopyran ring of PKF217 – 744 contribute to the potency of the compound and, therefore, make contact with SUR2B. In turn, this means that some parts of the binding site of PKF217 – 744 are not utilized by P1075; however, these parts do not seem to be important for the coupling to the nucleotide- and SU-sites on SUR2.

Mechanism of opener binding to SUR2B

PKF217 – 744 binds to SUR2B with about five times lower affinity than P1075 (Table 1). Comparison of the binding kinetics of the two radioligands reveals an interesting point. The dissociation rate constants are similar as shown by the half-times of the respective complexes, T1/2=8 min ([3H]-PKF217 – 744; this paper) and 10 min ([3H]-P1075, Hambrock et al., 1998). The association rate constants, however, differ by a factor of 4.5 (k+=6.9×106/3.1×107 M−1 min−1 for [3H]-PKF217 – 744 and [3H]-P1075, respectively), thus accounting for the difference in affinity between the two compounds. This result cannot easily be reconciled with the simple model that the opener, by a diffusion-controlled encounter, binds to a preformed binding site on SUR2. Firstly, this model predicts that the difference in affinity should be reflected in the dissociation rate constant. Secondly, the association rate constants are unusually slow; in fact they are about five orders of magnitude slower than estimated for a diffusion-controlled process (Alberty & Hammes, 1958). Hence, one has to assume a more complex mechanism of opener binding to SUR: the opener has to create its binding pocket either by inducing appropriate conformational changes in SUR2B (induced fit model) or by shifting a pre-existing equilibrium from a refractory state to a state accommodating the opener (Strickland et al., 1975). Some complexity in opener binding to SUR2 is indeed expected since opener binding requires the presence of MgATP or of hydrolysable ATP analogues (Quast et al., 1993; Dickinson et al., 1997; Hambrock et al., 1998; Schwanstecher et al., 1998). In turn, one may assume that opener binding will affect nucleotide binding to and hydrolysis by SUR2 (Bienengraeber et al., 2000). According to both the induced fit and the pre-existing equilibrium model, the dependence of the association kinetics on ligand concentration will deviate from the linear behaviour predicted by the simple one step bimolecular association model as given by equation (1) of Methods (Strickland et al., 1975). We have tried to test the validity of equation (1) by varying the opener concentration between 3 and 21 nM; at higher concentrations, the kinetics were too fast to be followed by the filtration assay. Within this limited concentration range, no deviation from linear behaviour was found. Obviously, methods with higher time resolution (e.g. using fluorescent openers) are needed to analyse the mechanism of opener binding.

Interaction between glibenclamide and[3H]-PKF217 – 744

The experiments in which the inhibition of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B by glibenclamide was studied gave two major results. Firstly, the potency of glibenclamide in this assay was ≈5 μM, a value close to that obtained with [3H]-P1075 as the radiolabel (Ki≈2.4 μM; Hambrock et al., 1998). This is two orders of magnitude lower than the KD value determined by homologous displacement from SUR2B (KD≈30 nM, Russ et al., 1999; but see Dörschner et al., 1999) or the potency of glibenclamide in blocking the Kir6.1/SUR2B and the Kir6.2/SUR2B channel (IC50≈40 nM, Dörschner et al., 1999; Russ et al., 1999). The second result is that glibenclamide increased the dissociation rate of the [3H]-PKF217 – 744-SUR2B complex in a concentration-dependent manner. This phenomenon had been observed before with [3H]-P1075 binding to the vascular KATP channel (Bray & Quast, 1992) and to SUR2B (Hambrock et al., 1998).

The low potency of glibenclamide in inhibiting opener binding and its effect on opener dissociation kinetics may be explained by recent studies showing that essential parts of binding sites for sulphonylureas and openers (cyanoguanidines and benzopyrans) are different but located in close proximity to one another on the third domain of SUR (Ashfield et al., 1999; Uhde et al., 1999; Babenko et al., 2000). The work of Uhde et al. (1999) suggests that glibenclamide inhibits P1075 binding and vice versa by an allosteric rather than by a direct competitive interaction, thus corroborating earlier inferences made on the basis of kinetic (Bray & Quast, 1992) and equilibrium binding experiments (Schwanstecher et al., 1992). The allosteric nature of the interaction may explain that the true affinity of glibenclamide binding to SUR2B as determined in [3H]-glibenclamide binding assays (Russ et al., 1999) is not obtained in heterologous ([3H]-opener vs glibenclamide) inhibition assays. Furthermore, at higher concentrations, glibenclamide may be able to bind to the SUR2B-opener complex forming a labile ternary (SUR2B-opener-glibenclamide) complex with rapid dissociation of the opener. This model predicts that glibenclamide, at concentrations well below those which saturate the ternary complex, will accelerate the dissociation of the opener from SUR2B with a linear dependence on glibenclamide concentration (Quast, 2001 unpublished results). It is encouraging to observe that the two ‘strange' aspects of the interaction of glibenclamide with the opener P1075 at SUR2B are confirmed using the novel benzopyran-type opener, [3H]-PKF217 – 744, and that they are in line with recent results on the topology of the binding sites for sulphonylureas and openers at SUR2.

In conclusion, we have characterized the binding properties of [3H]-PKF217 – 744, a tritiated benzopyran-type opener. The pharmacological properties of PKF217 – 744 binding are identical with those obtained earlier with the cyanoguanidine opener, [3H]-P1075, suggesting that the coupling of the respective binding sites to nucleotide binding and to signal transduction within SUR are the same. The unusually low association rate constant of [3H]-PKF217 – 744 binding to SUR2B suggests a complex mechanism of opener binding to SUR. It is hoped that the better understanding of the interaction of the KATP channel openers with the different channel subtypes will be of help for the design of openers with increased tissue selectivity.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, grant Qu 100/2-4. We thank Drs Y. Kurachi and Y. Horio (Osaka) for the generous gift of the murine clones of SUR2A, 2B and Kir6.1 and the pharmaceutical companies mentioned in Methods for the generous gift of drugs.

Abbreviations

- ATP

adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- HEK cells

human embryonic kidney cells

- KATP channel

ATP-sensitive K+ channel

- KCO

KATP channel opener

- Kir

inwardly rectifying K+ channel

- [3H]-PKF217 – 744

(3S,4R)-N-[3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-3-hydroxy-6-(2-methyl-4-pyridinyl)-2H-1-benzopyran-4-yl]-3-[2,6-3H]pyridinecarboxamide

- popen

open probability of channel

- SU

sulphonylurea

- SUR

sulphonylurea receptor

References

- AGUILAR-BRYAN L., BRYAN J. Molecular biology of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Endocrine Rev. 1999;20:101–135. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.2.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AGUILAR-BRYAN L., NICHOLS C.G., WECHSLER S.W., CLEMENT J.P., IV, BOYD A.E., III, GONZÁLES G., HERRERA-SOZA H., NGUY K., BRYAN J., NELSON D.A. Cloning of the ß cell high-affinity sulfonylurea receptor: a regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1995;268:423–426. doi: 10.1126/science.7716547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALBERTY R.A., HAMMES G.G. Application of the theory of diffusion-controlled reactions to enzyme kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. 1958;62:154–159. [Google Scholar]

- ASHCROFT F.M., GRIBBLE F.M. Correlating structure and function in ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:288–294. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASHCROFT S.J.H., ASHCROFT F.M. Properties and functions of ATP-sensitive K-channels. Cell. Signal. 1990;2:197–214. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(90)90048-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASHFIELD R., GRIBBLE F.M., ASHCROFT S.J.H., ASHCROFT F.M. Identification of the high-affinity tolbutamide site on the SUR1 subunit of the KATP channel. Diabetes. 1999;48:1341–1347. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.6.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATWAL K.S. Modulation of potassium channels by organic molecules. Med. Res. Rev. 1992;12:569–591. doi: 10.1002/med.2610120603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BABENKO A.P., AGUILAR-BRYAN L., BRYAN J. A view of SUR/KIR6.X, KATP channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1998;60:667–687. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BABENKO A.P., GONZALEZ G., BRYAN J. Pharmaco-topology of sulfonylurea receptors – Separate domains of the regulatory subunits of KATP channel isoforms are required for selective interaction with K+ channel openers. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:717–720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEVINGTON P.R. Data reduction and error analysis for the physical sciences 1969New York: McGraw-Hill; 55, 92–65.and [Google Scholar]

- BIENENGRAEBER M., ALEKSEEV A.E., ABRAHAM M.R., CARRASCO A.J., MOREAU C., VIVAUDOU M., DZEJA P.P., TERZIC A. ATPase activity of the sulfonylurea receptor: a catalytic function for the KATP channel complex. FASEB J. 2000;14:1943–1952. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0027com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADING A.F., TURNER W.H.Potassium channels and their modulation in urogenital tract smooth muscles Potassium Channels and their Modulators: From Synthesis to Clinical Experience 1996London: Taylor & Francis; 335–359.eds. Evans, J.M., Hamilton, T.C., Longman, S.D. & Stemp, G. pp [Google Scholar]

- BRAY K.M., QUAST U. A specific binding site for K+ channel openers in rat aorta. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:11689–11692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCHHEIT K.-H., HOFMANN A., MANLEY P., PFANNKUCHE H.-J., QUAST U. Atypical effect of minoxidil sulphate on Guinea pig airways. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2000;361:418–424. doi: 10.1007/s002100000218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG Y., PRUSOFF W.H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50% inhibition (IC50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHRISTOPOULOS A. Assessing the distribution of parameters in models of ligand-receptor interaction: to log or not to log. Trends. Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:351–357. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01240-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLQUHOUN D., SIGWORTH F.J.Fitting and Statistical Analysis of Single-channel Records Single-Channel Recording 1995New York: Plenum Press; 483–587.Second Edition, eds. Sakmann B. & Neher E. pp [Google Scholar]

- DE KECZER S., PARNES H. Synthesis of [4,6-3H]-2-pyridone and [3H]-RS-91309. J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm. 1995;36:765–772. [Google Scholar]

- D'HAHAN N., JACQUET H., MOREAU C., CATTY P., VIVAUDOU M. A transmembrane domain of the sulfonylurea receptor mediates activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels by K+ channel openers. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999a;56:308–315. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'HAHAN N., MOREAU C., PROST A.-L., JACQUET H., ALEKSEEV A.E., TERZIC A., VIVAUDOU M. Pharmacological plasticity of cardiac ATP-sensitive potassium channels toward diazoxide revealed by ADP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999b;96:12162–12167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DICKINSON K.E.J., BRYSON C.C., COHEN R.B., ROGERS L., GREEN D.W., ATWAL K.S. Nucleotide regulation and characteristics of potassium channel opener binding to skeletal muscle membranes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:473–481. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DÖRSCHNER H., BREKARDIN E., UHDE I., SCHWANSTECHER C., SCHWANSTECHER M. Stoichiometry of sulfonylurea-induced ATP-sensitive potassium channel closure. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;55:1060–1066. doi: 10.1124/mol.55.6.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRAPER N.B., SMITH H. Applied regression analysis 1981New York: Wiley; 85, 458–96.and [Google Scholar]

- EDWARDS G., WESTON A.H. The pharmacology of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1993;33:597–637. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDWARDS G., WESTON A.H.Effect of potassium channel modulating drugs on isolated smooth muscle Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology 1994111Heidelberg: Springer; 469–531.eds. Szekeres, L.J. & Papp, G. pp [Google Scholar]

- EVANS J.M., STEMP G.Structure-activity relationship of benzopyran based potassium channel activators Potassium Channels and their Modulators: From Synthesis to Clinical Experience 1996London: Taylor & Francis; 27–55.eds. Evans, J.M., Hamilton, T.C., Longman, S.D. & Stemp, G. pp [Google Scholar]

- FOZARD J.R., MANLEY P.W.Potassium channel openers: Agents for the treatment of airway hyperreactivity New Drugs for Asthma, Allergy and COPD 200031Basel: Karger; 87–80.Prog. Respir. Res., eds. Hansel, T.T. & Barnes, P.J. [Google Scholar]

- GRIBBLE F.M., REIMANN F., ASHFIELD R., ASHCROFT F.M. Nucleotide modulation of pinacidil stimulation of the cloned KATP channel Kir6.2/SUR2A. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;57:1256–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GROVER G.J., GARLID K.D. ATP-sensitive potassium channels: A review of their cardioprotective pharmacology. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2000;32:677–695. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMBROCK A., LÖFFLER-WALZ C., KLOOR D., DELABAR U., HORIO Y., KURACHI Y., QUAST U. ATP-Sensitive K+ Channel Modulator Binding to Sulfonylurea Receptors SUR2A and SUR2B: Opposite Effects of MgADP. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;55:832–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMBROCK A., LÖFFLER-WALZ C., KURACHI Y., QUAST U. Mg2+ and ATP dependence of KATP channel modulator binding to the recombinant sulphonylurea receptor, SUR2B. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:577–583. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILL O.P., MARTY A., NEHER E., SAKMANN B., SIGWORTH F.J. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOF R.P., QUAST U., COOK N.S., BLARER S. Mechanism of action, systemic and regional hemodynamics of the potassium channel activator BRL 34915 and its enantiomers. Circ. Res. 1988;62:679–686. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOWLETT D.R., LONGMAN S.D. Identification of a binding site for [3H]-chromakalim in vascular and bronchial smooth muscle cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;107:396P. [Google Scholar]

- INAGAKI N., GONOI T., CLEMENT J.P., IV, WANG C.Z., AGUILAR-BRYAN L., BRYAN J., SEINO S. A family of suphonylurea receptors determines the pharmacological properties of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Neuron. 1996;16:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISOMOTO S., KONDO C., YAMADA M., MATSUMOTO S., HIGASHIGUCHI O., HORIO Y., MATSUZAWA Y., KURACHI Y. A novel sulfonylurea receptor forms with BIR (KIR6.2) a smooth muscle type ATP-sensitive K+ channel. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:24321–24324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAWSON K. Potassium channel activation: A potential therapeutic approach. Pharmacol. Ther. 1996;70:39–63. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(96)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O.H., ROSEBROUGH N.J., FARR A.L., RANDALL R.J. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANLEY P.W., QUAST U., ANDRES H., BRAY K.M. Synthesis of and radioligand binding studies with a tritiated pinacidil analogue: receptor interactions of structurally different classes of potassium channel openers and blockers. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:2004–2010. doi: 10.1021/jm00066a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANNHOLD R., LEMOINE H., JASPERT S. Comparison of binding and relaxant properties of potassium channel openers (KCO) in calf coronary arteries. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. Suppl. 1996;353:R54. [Google Scholar]

- QUAST U. Effect of the K+ efflux stimulating vasodilator BRL 34915 on 86Rb+ efflux and spontaneous activity in guinea-pig portal vein. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987;91:569–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUAST U.Effects of potassium channel activators in isolated blood vessels Potassium Channels and their Modulators: From Synthesis to Clinical Experience 1996London: Taylor & Francis; 173–195.eds. Evans, J.M., Hamilton, T.C., Longman, S.D. & Stemp, G. pp [Google Scholar]

- QUAST U., BRAY K.M., ANDRES H., MANLEY P.W., BAUMLIN Y., DOSOGNE J. Binding of the K+ channel opener [3H]P1075 in rat isolated aorta: relationship to functional effects of openers and blockers. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;43:474–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSS U., HAMBROCK A., ARTUNC F., LÖFFLER-WALZ C., HORIO Y., KURACHI Y., QUAST U. Coexpression with the inward rectifier K+ channel Kir6.1 increases the affinity of the vascular sulfonylurea receptor SUR2B for glibenclamide. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:955–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAKURA H., ÄMMÄLÄ C., SMITH P.A., GRIBBLE F.M., ASHCROFT F.M. Cloning and functional expression of the cDNA encoding a novel ATP-sensitive potassium channel subunit expressed in pancreatic ß-cells, brain, heart and skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:338–344. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWANSTECHER M., BRANDT C., BEHRENDS S., SCHAUPP U., PANTEN U. Effect of MgATP on pinacidil-induced displacement of glibenclamide from the sulphonylurea receptor in a pancreatic ß-cell line and rat cerebral cortex. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;106:295–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWANSTECHER M., SIEVERDING C., DÖRSCHNER H., GROSS I., AGUILAR-BRYAN L., SCHWANSTECHER C., BRYAN J. Potassium channel openers require ATP to bind to and act through sulfonylurea receptors. EMBO J. 1998;17:5529–5535. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEINO S. ATP-sensitive potassium channels: A model of heteromultimeric potassium channel/receptor assemblies. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1999;61:337–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRICKLAND S., PALMER G., MASSEY V. Determination of dissociation constants and specific rate constants of enzyme-substrate (or protein-ligand) interactions from rapid reaction kinetic data. J. Biol. Chem. 1975;250:4048–4052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TALLARIDA R.J. Receptor discrimination and control of agonist-antagonist binding. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:E379–E391. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.269.2.E379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANABE K., TUCKER S.J., MATSUO M., PROKS P., ASHCROFT F.M., SEINO S., AMATCHI T., UEDA K. Direct photoaffinity labelling of the Kir6.2 subunit of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel by 8-azido-ATP. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:3931–3933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TUCKER S.J., GRIBBLE F.M., ZHAO C., TRAPP S., ASHCROFT F.M. Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature. 1997;387:179–183. doi: 10.1038/387179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UEDA K., INAGAKI N., SEINO S. MgADP antagonism to Mg2+-independent ATP binding of the sulfonylurea receptor SUR1. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:22983–22986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.22983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UEDA K., KOMINE J., MATSUO M., SEINO S., AMACHI T. Cooperative binding of ATP and MgADP in the sulfonylurea receptor is modulated by glibenclamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:1268–1272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UHDE I., TOMAN A., GROSS I., SCHWANSTECHER C., SCHWANSTECHER M. Identification of the potassium channel opener site on sulfonylurea receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:28079–28082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMADA M., ISOMOTO S., MATSUMOTO S., KONDO C., SHINDO T., HORIO Y., KURACHI Y. Sulphonylurea receptor 2B and Kir6.1 form a sulphonylurea-sensitive but ATP-insensitive K+ channel. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1997;499:715–720. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]