Abstract

Recent studies have reported that hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors have vasculoprotective effects independent of their lipid-lowering properties, including anti-inflammatory actions. We used intravital microscopy of the rat mesenteric microvasculature to examine the effects of rosuvastatin, a new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, on leukocyte-endothelium interactions induced by thrombin.

Intraperitoneal administration of 0.5 and 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin 18 h prior to the study, significantly and dose-dependently attenuated leukocyte rolling, adherence, and transmigration in the rat mesenteric microvasculature superfused with 0.5 u ml-1 thrombin. This protective effect of rosuvastatin was reversed by intraperitoneal injection of 25 mg kg−1 mevalonic acid 18 h before the study.

Immunohistochemical detection of the endothelial cell adhesion molecule P-selectin showed a 70% decrease in endothelial cell surface expression of P-selectin in thrombin-stimulated rats given 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin. In addition, rosuvastatin enhanced release of nitric oxide (NO) from the vascular endothelium as measured directly in rat aortic segments. Moreover, rosuvastatin failed to attenuate leukocyte-endothelium interactions in peri-intestinal venules of eNOS−/− mice.

These data indicate that rosuvastatin exerts important anti-inflammatory effects via inhibition of endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression, and that this protective action of rosuvastatin requires release of nitric oxide by the vascular endothelium. These data also demonstrate that the mechanism of the non-lipid lowering actions of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors in vivo may be due to reduced formation or availability of mevalonic acid within endothelial cells.

Keywords: Leukocyte, endothelium, mevalonate, microcirculation, P-selectin, statins

Introduction

The 3-hydroxy-methyl-3-glutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (e.g. simvastatin, lovastatin, fluvastatin, etc.) have been employed as therapeutic agents in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases associated with hypercholesterolaemia. These compounds, collectively referred to as statins, exert their biological effects by blocking the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate in the hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis pathway (Alberts, 1988). The subsequent lipid-lowering effect is correlated with a decreased risk of coronary and cerebrovascular events, and results in increased survival rates in patients with coronary artery disease (Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group, 1994; Shepherd et al., 1995; Levine et al., 1995; Treasure et al., 1995). However, recent studies have shown that statins may also exert effects beyond their lipid-lowering properties. Thus, statins decrease the risk of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events even in normocholesterolaemic patients (Delanty & Vaughan, 1997; Sacks et al., 1996). In an attempt to explain the nature of these non-cholesterol lowering effects of statins, several investigators have studied the effect of statins on vascular endothelial function under cholesterol clamped conditions (Laufs et al., 1998; Pruefer et al., 1999; Lefer et al., 1999).

Recent studies have shown that systemic administration of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors to normocholesterolaemic animals protects the vascular endothelium from inflammatory processes (Lefer et al., 1999; Pruefer et al., 1999). These non-lipid lowering effects were in part due to up-regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) by statins. In this regard, Laufs et al. (1998) reported that statins are able to increase expression of eNOS mRNA in vitro. Nitric oxide is known to preserve endothelial function during pathophysiologic conditions by preventing leukocyte adherence to the endothelium (Kubes et al., 1991) via decreased expression of cell adhesion molecules on the endothelial surface (Lefer, 1997), including members of the selectin family of adhesion glycoproteins (e.g., P-selectin) (Gauthier et al., 1994).

In the present study, we examined: (a) the protective effects of a new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, rosuvastatin, in acute inflammation of the rat mesenteric microvasculature, (b) the role of nitric oxide in the anti-inflammatory action of rosuvastatin, (c) the role of P-selectin in the attenuation of leukocyte-endothelium interaction by rosuvastatin, and (d) the ability of mevalonic acid to reverse the effect of rosuvastatin in vivo.

Methods

Animal models and study protocols used for intravital microscopy

This study was performed in accordance with the National Institute of Health guidelines for the use of experimental animals, and all animal protocols have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Thomas Jefferson University.

Rats

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (ACE, Boyertown, PA, U.S.A.) weighing 250 – 275 g were anaesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 60 mg kg−1 sodium pentobarbital. Additional sodium pentobarbital was administered intraperitoneally as needed during the 2 h intravital microscopy observation time. The left carotid artery was cannulated using a polyethylene catheter for measurement of mean arterial blood pressure. A loop of ileal intestine was exteriorized through a midline incision and placed in a temperature controlled, fluid-filled Plexiglas chamber for observation of the mesenteric microcirculation by intravital microscopy, as previously described (Scalia et al., 1997). The mesentery was then superfused with a modified Krebs – Henseleit buffer, warmed to 37°C and bubbled with 95% nitrogen and 5% carbon dioxide. Mean arterial blood pressure was monitored and recorded using a Grass model 7 oscillograph recorder with a Statham P23AC pressure transducer (Gould). Red blood cell velocity was measured using an optical Doppler velocimeter (Microcirculation Research Institute, College Station, TX, U.S.A.) as previously described (Scalia et al., 1997). Venular shear rates (g) were calculated using the venular diameter (D) and RBC velocity (V) with the following formula: g=8(Vmean/D), where Vmean=V/1.6 (Borders & Granger, 1984).

Following 30 min stabilization time, a 20 – 40 μm diameter venule was selected for direct observation of leukocyte-endothelium interactions. A baseline reading was taken to establish basal values for leukocyte rolling, adherence, and the number of transmigrating leukocytes. Readings were subsequently taken 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after the basal values were obtained to quantify leukocyte rolling, adherence and transmigration, using video recordings with a video camera and videocassette recorder.

Rats were randomly divided into one of three major groups of five to eight rats: (a) rats superfused with K-H buffer as vehicle and given 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin; (b) rats superfused with 0.5 u ml−1 thrombin and given 0.9% NaCl; and (c) rats superfused with 0.5 u ml−1 thrombin and given either 0.125, 0.5, or 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin. All doses of rosuvastatin were administered intraperitoneally 18 h prior to the experiments. These doses correspond to the clinically relevant dose range in humans. On experiments, the exposed mesentery was superfused with 0.5 u ml−1 thrombin.

The effects of the intraperitoneal administration of mevalonic acid were studied in two additional groups of rats that were superfused with 0.5 u ml−1 thrombin and given 25 mg kg−1 mevalonic acid intraperitoneally with or without 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin 18 h prior to intravital microscopy.

Gene targeted mice

Wild-type (C57BL/6; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine, U.S.A.) mice and eNOS deficient (eNOS−/−) mice (C57BL/6; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine, U.S.A.) were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (120 mg kg−1) injected intraperitoneally. The left carotid artery was cannulated for continuous blood pressure monitoring. Intravital microscopy was performed on mouse peri-intestinal venules, after exteriorization of a loop of ileal tissue via a midline laparotomy. Mice were randomly divided into one of three groups: wild-type mice given rosuvastatin and superfused with K-H buffer, eNOS−/− mice given saline and superfused with K-H buffer, and eNOS−/− mice given 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin subcutaneously and superfused with K-H buffer. All rosuvastatin injected mice were studied 18 h post-treatment.

Immunohistochemistry

Following completion of the intravital microscopy, the superior mesenteric artery and vein were cannulated for perfusion of the small bowel. The ileum was first washed free of blood by perfusion with Krebs – Henseleit buffer warmed to 37°C and bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Once the venous perfusate was free of red blood cells, perfusion was initiated with iced 4% paraformaldehyde mixed in phosphate buffered 0.9% NaCl for 5 min. A 3 – 4 cm segment of ileum was isolated from the perfused intestine and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 90 min at 4°C. Tissue sections were embedded in plastic (Immunobed: Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA, U.S.A.), and 4 μm thick sections were cut and transferred to Vectabond coated slides (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.). Immunohistochemical localization of P-selectin was accomplished using the avidin/biotin immunoperoxidase technique (Vectasin ABC Reagent: Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.), using a monoclonal antibody against P-selectin exposed on the endothelial cell surface as previously described (Weyrich et al., 1995). Fifty venules were analysed per tissue section and 10 sections were examined per rat, and the percentage of positive staining was determined.

Quantification of NO released from isolated aortic segments

Freshly isolated rat aortic rings were used as the source of primary endothelial cells. Thoracic aortae were rapidly isolated from control rats given 0.9% NaCl or 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin 18 h post-injection. Aortae were immersed into warm oxygenated K-H solution and cleaned of adherent fat and connective tissue. Rings of 6 – 7 mm length were carefully cut and opened in order to preserve the vascular endothelium. These segments were fixed by small insect mounting pins with the endothelial surface up in 24 well culture dishes containing 1 ml K-H solution. After equilibration at 37°C, NO released into the K-H solution was measured according to the method of Guo et al, (1996), using an internally shielded polarographic NO electrode connected to a NO meter (Iso-NO, World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL, U.S.A.). Calibration of the NO electrode was performed daily prior to analysis of basal NO release in aortic segments.

Drugs

Rosuvastatin (formerly ZD4522) has the chemical name monocalcium bis [(+)-(3R,5S,6E)-7-[4-(p-fluorophenyl)-6- isopropyl -2 -(N-methylmethanesulphonamide)-5-pyrimidinyl]-3,5-dihydroxy-6-heptenoate (AstroZeneca, U.K.). Bovine thrombin was purchased from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO, U.S.A.).

Data analysis

All data are presented as mean±s.e.mean. Data were compared by ANOVA with post hoc analysis by Fisher's corrected t-test. All data on leukocyte rolling, adherence, and transmigration, as well as on mean arterial blood pressure and shear rates, were analysed by ANOVA for repeated measurements. Probabilities of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant.

Results

Rat mesenteric microcirculation

Values for mean arterial blood pressure and venular shear force were measured for all experimental groups of rats. There was no difference in the initial mean arterial blood pressure among the four groups of rats after all surgical procedures were performed. Mean arterial blood pressures ranged between 123±3 and 135±5 mmHg over the 2 h observation period. Moreover, no significant systemic effect was observed after administration or rosuvastatin to the rats or following exposure of the rat mesentery to thrombin, as confirmed by the absence of any significant changes in mean arterial blood pressure over the 120 min observation period. Additionally, when venular shear rates for the different time-points were calculated in all experimental groups, no significant differences were observed. Thus, venular diameters ranged from 33 to 42 μm in all groups, and venular shear rates varied between 714±124 to 830±123 (s−1) in all groups. These results indicate that any changes in leukocyte-endothelium dynamics were not due to variations in hemodynamic forces.

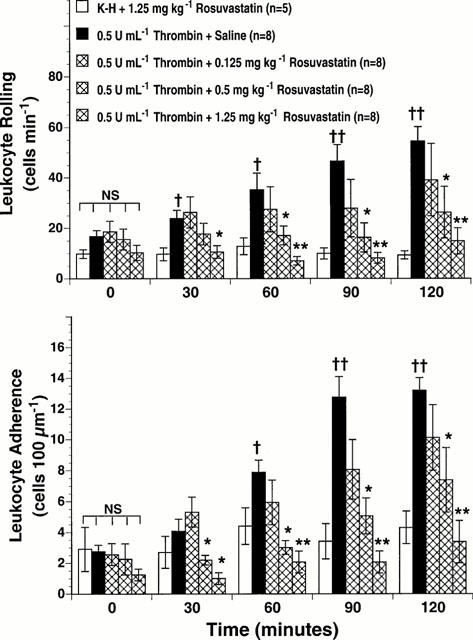

Leukocyte rolling in post-capillary venules of the rat mesentery was stable over the entire observation time at approximately 10 cells min−1 in control animals (Figure 1, upper panel). However, superfusion of the rat mesentery with 0.5 u ml−1 thrombin increased leukocyte rolling over time with statistically significant differences occurring as early as 30 min post-thrombin (Figure 1, upper panel, P<0.05 vs control). The number of leukocytes rolling along the venular endothelium increased 3 – 4 fold above initial values by 120 min (P<0.01 vs control, Figure 1, upper panel). In contrast, treatment of rats with 0.5 and 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin significantly inhibited thrombin-stimulated leukocyte rolling to values comparable to those observed in control rats superfused with K-H buffer (Figure 1, upper panel, P<0.01 vs thrombin alone). The low dose of 0.125 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin did not significantly attenuate thrombin-induced leukocyte rolling.

Figure 1.

Effect of rosuvastatin on thrombin-stimulated leukocyte rolling (upper panel) and leukocyte adherence (lower panel) in rat mesenteric venules. Rat mesenteries were superfused with either K-H buffer alone or with 0.5 u ml−1 thrombin. The indicated doses of rosuvastatin were administered intraperitoneally 18 h prior to the study. All values are means±s.e.mean for numbers of rolling and adhering cells observed at 0, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min for each group (n=number of rats/group). Rosuvastatin (0.5 and 1.25 mg kg−1) significantly inhibited thrombin-stimulated leukocyte rolling and adherence. †P<0.05 and ††P<0.01 vs control mesenteries. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs thrombin superfused mesenteries. NS=not significant.

Leukocyte adherence to the venular endothelium of the rat mesentery is illustrated in Figure 1, lower panel. In control animals, a low number of adherent leukocytes was recorded (i.e., 2 – 3 leukocytes 100 μm−1 of endothelial length) (Figure 1, lower panel). Superfusion of the rat mesentery with thrombin significantly increased leukocyte adherence at 60 min (Figure 1, lower panel, P<0.05 vs control), with peak values occurring at 120 min post-thrombin (Figure 1, lower panel, P<0.01 vs control). Pretreatment with 0.5 or 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin significantly attenuated the effects of thrombin on leukocyte adherence (Figure 1, lower panel).

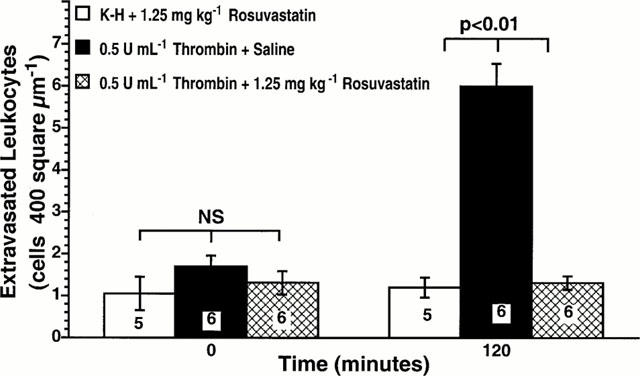

Following superfusion of the rat mesentery with thrombin, the number of extravasated leukocytes found within a 400 μm2 area adjacent to the post-capillary venules increased significantly at 120 min post-superfusion (Figure 2). Intraperitoneal administration of 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin significantly reduced thrombin-induced transmigration of leukocytes across mesenteric venules (Figure 2, P<0.01 vs thrombin alone). Therefore, rosuvastatin is a new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor able to exert potent anti-inflammatory effects in normocholesterolemic rats.

Figure 2.

Effect of rosuvastatin on thrombin-stimulated leukocyte extravasation. Rat mesenteries were superfused with either K-H buffer alone or with 0.5 u ml−1 thrombin. Rosuvastatin (1.25 mg kg−1) was administered intraperitoneally 18 h prior to the study. All values are means±s.e.mean for numbers of extravasated cells observed at 0, and 120 min for each group. Numbers at the base of the bars indicate the numbers of rats studied in each group. Rosuvastatin significantly inhibited thrombin-stimulated leukocyte extravasation.

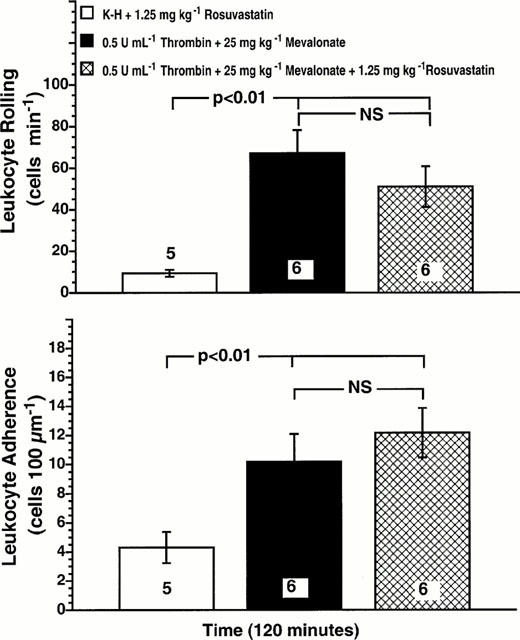

Inhibition of rosuvastatin effects by mevalonic acid

In order to elucidate the mechanism of the anti-inflammatory action of rosuvastatin, we administered 25 mg kg−1 mevalonic acid intraperitoneally to rats that were also given 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin. Thrombin superfusion of the mesentery of mevalonic-acid-injected rats increased leukocyte rolling 6 fold at 120 min post-superfusion (Figure 3, upper panel, P<0.01 vs control). In contrast to rats that were pretreated with rosuvastatin in the absence of mevalonic acid, rosuvastatin failed to inhibit thrombin-stimulated leukocyte rolling in mevalonic-acid-injected rats (Figure 3, upper panel). Similar effects of mevalonate were observed on leukocyte adherence (Figure 3, lower panel). These results indicate that mevalonate blocks the anti-inflammatory actions of rosuvastatin on the microvasculature.

Figure 3.

Mevalonic acid blocks the inhibitory effect of rosuvastatin on thrombin-stimulated leukocyte rolling (upper panel) and leukocyte adherence (lower panel). Rat mesenteries were superfused with either K-H buffer alone or 0.5 u ml−1 thrombin. Rats were injected with 25 mg kg−1 mevalonic acid+1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin intraperitoneally 18 h before study. Values are means±s.e.mean for numbers of rolling and adherence cells observed at 120 min for each group. Numbers at the base of the bars indicate the numbers of rats studied in each group. Intraperitoneal administration of mevalonic acid reversed the effects of rosuvastatin on thrombin-stimulated leukocyte rolling and adherence.

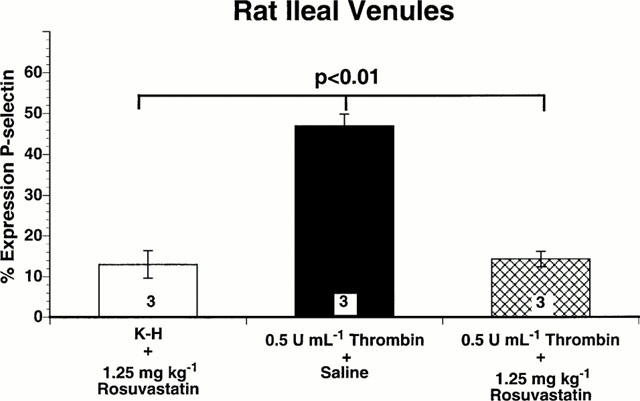

Effect of rosuvastatin administration on expression of P-selectin in rat ileal venules

Surface expression of the adhesion molecules P-selectin was investigated on the microvascular mesenteric endothelium of control rats, thrombin-superfused rats given 0.9% NaCl, and thrombin superfused rats treated with 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin.

The percentage of venules staining positively for P-selectin in ileal sections from control rats superfused only with K-H buffer was consistently low (Figure 4). However, superfusion with 0.5 u ml−1 thrombin for 120 min resulted in increased expression of P-selectin as quantified by the percentage of venules staining positively for P-selectin (P<0.01). This represents a statistically significant increase in the surface expression of P-selectin under these experimental conditions. This increased P-selectin expression on the venular endothelium was significantly attenuated by the intraperitoneal administration of 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin (Figure 4). Thus, intraperitoneal administration of rosuvastatin significantly attenuates increased venular surface expression of P-selectin during acute inflammation of the microcirculation. These data are consistent with the functional changes in leukocyte rolling, adherence and transmigration shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical analysis of P-selectin expression on rat ileal venules, expressed as percentage of venules staining positive for P-selectin. Bar heights represent mean values; brackets indicate±s.e.mean. Numbers at the base of the bars indicate the numbers of rats studied in each group. Twenty sections were studied in each rat. Rosuvastatin (1.25 mg kg−1) significantly inhibited endothelial cell surface expression of P-selectin induced by thrombin.

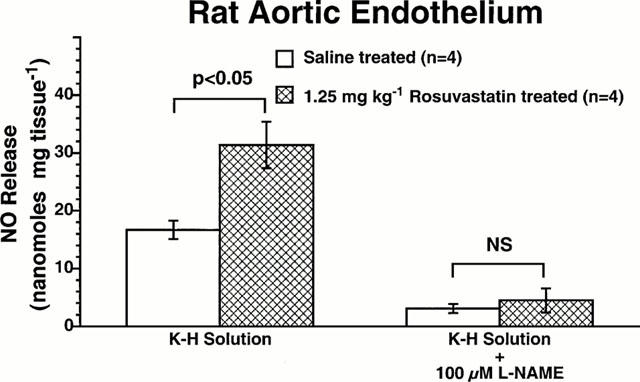

Effect of rosuvastatin administration on NO release from isolated rat aorta segments

We detected a low basal level of NO release in the range of 16 nmol g−1 of tissue in aortic segments isolated from control rats given only saline (Figure 5). However, 18 h after rats were given 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin intraperitoneally, we detected a 2 fold increase in the basal release of NO in aortic segments (Figure 5; P<0.01 versus rats given saline). In four de-endothelialized rat aortic segments no detectable NO was measured. Moreover, addition of a full NOS inhibitory concentration of L-NAME (i.e., 100 mM) totally inhibited NO release in aortic segments obtained from both control rats and rosuvastatin-treated rats (Figure 5). Therefore, intraperitoneal administration of rosuvastatin to the rats increases endothelium-derived nitric oxide release in the rat aorta.

Figure 5.

Effect of rosuvastatin on NO release in rat aortic segments. Basal release of nitric oxide is expressed as nanomoles per mg tissue. NO release was measured in isolated rat aortic rings obtained from control rats given vehicle, and in rats injected with 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin. Bar heights are means; brackets are±s.e.mean. Rosuvastatin significantly increased NO release from rat aortic endothelium. L-NAME (100μM), inhibited basal release of NO in all experimental groups of rats.

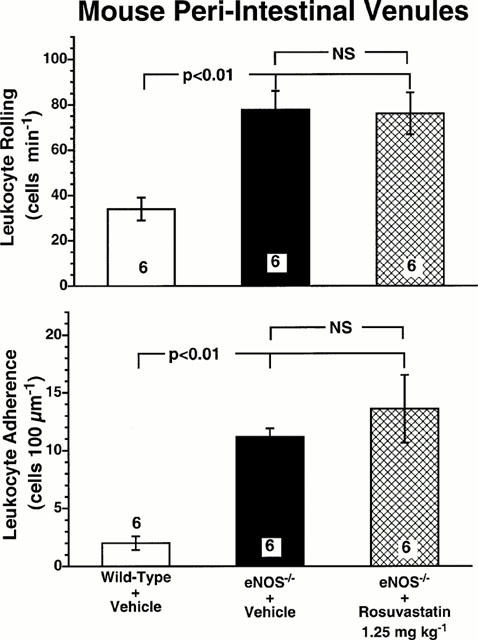

Effect of rosuvastatin in eNOS−/− mice

To further test our hypothesis that the anti-inflammatory action of rosuvastatin is mediated by NO, we studied leukocyte-endothelium interactions in eNOS deficient mice. Compared with C57BL/6 wild-type control mice, eNOS deficient mice exhibited a higher leukocyte rolling flux (Figure 6, upper panel) and greater degree of leukocyte adherence (Figure 6, lower panel) in peri-intestinal venules. Systemic administration of rosuvastatin (1.25 mg kg−1) failed to inhibit the abnormal increase in baseline leukocyte rolling and adherence observed in eNOS deficient mice (Figure 6). This clearly demonstrates that upregulation of eNOS activity is the predominant mechanism by which rosuvastatin attenuates leukocyte-endothelium interaction during inflammatory states of the microcirculation.

Figure 6.

Leukocyte rolling (upper panel) and leukocyte adherence (lower panel) in peri-intestinal venules of wild-type mice, eNOS−/− mice, and eNOS−/− mice given 1.25 mg kg−1 rosuvastatin. Bar heights show the numbers of rolling and adhering leukocytes for the three experimental groups of mice. All values are means±s.e.mean. Numbers at the base of the bars indicate the numbers of mice studied in each group. Rosuvastatin was given to the mice subcutaneously 18 h prior to the experiment. Rosuvastatin failed to inhibit either leukocyte rolling or leukocyte adherence in eNOS−/− mice.

Discussion

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors have been shown to decrease the risk of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease and hypercholesterolaemia (Treasure et al., 1995; Delanty & Vaughan, 1997). These beneficial effects have usually been attributed to the lipid-lowering properties of the statins. However, recent studies have shown that HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors also offer some additional protection against cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events as well as in acute inflammatory processes. These beneficial effects appear to be exerted by a non lipid-lowering mechanism. In this regard, statins have been shown to increase expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase leading to enhanced release of NO, which could be responsible for several of the non-lipid lowering actions of the statins (Laufs et al., 1998). Endothelium-derived nitric oxide preserves endothelial function (Lefer & Lefer, 1993), inhibits platelet aggregation (Radomski et al., 1987), and attenuates leukocyte-endothelium interactions (Kubes et al., 1991).

In the current study, we investigated the effect of a new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, rosuvastatin, on thrombin-stimulated leukocyte-endothelium interactions in vivo in normocholesterolaemic rats. We found that rosuvastatin inhibited endothelial cell surface expression of P-selectin, thus attenuating thrombin-induced leukocyte rolling along the endothelium, adherence to the endothelium, and transmigration through the endothelium in rat mesenteric venules. Previously, we have demonstrated that another statin also protected against leukocyte-endothelium interaction induced by the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) (Pruefer et al., 1999). We also obtained evidence that this inhibition is reversed by intraperitoneal administration of mevalonic acid. Rosuvastatin exerts its anti-inflammatory effect along with increased release of nitric oxide from the vascular endothelium in normocholesterolemic rats treated with rosuvastatin. Consistent with this concept, rosuvastatin failed to exert anti-inflammatory effects in mice lacking the gene for endothelial nitric oxide synthase, thus demonstrating the essential role of eNOS in mediating the beneficial effect of statins during acute inflammatory states. Taken together, these data indicate that rosuvastatin is able to significantly attenuate the inflammatory process (i.e., leukocyte-endothelium interactions), thus preventing leukocyte invasion of the extravascular space, which provokes subsequent tissue injury.

During acute endothelial dysfunction, several cell adhesion molecules become upregulated on the endothelial cell surface (Kubes et al., 1991). Among these cell adhesion molecules, P-selectin plays a key role in initiating leukocyte rolling, the first step of the leukocyte-endothelial cell interaction (McEver, 1991). P-selectin is stored in Weibel-Palade bodies within endothelial cells, and is translocated to the cell surface upon stimulation by various inflammatory mediators including histamine, thrombin and oxygen-derived free radicals (Patel et al., 1991). This rapid translocation process is attenuated by nitric oxide (Davenpeck et al., 1994), which inhibits a protein kinase C mediated regulatory mechanism (Murohara et al., 1996). Therefore, one would expect the expression of P-selectin to be attenuated by agents that increase nitric oxide production. Thus, increased nitric oxide production by statins could explain the modulation of these leukocyte-endothelium interactions. Accordingly, our results demonstrate that increased release of endothelial nitric oxide by rosuvastatin is associated with down-regulation of leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions. One of the primary mediators of these anti-inflammatory effects is retardation of endothelial cell surface expression of P-selectin.

Other investigators (Endres et al., 1998) have reported protection from cerebral damage in mice subjected to cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion that were pretreated with simvastatin. Our findings demonstrate that rosuvastatin fails to inhibit leukocyte-endothelium interactions in eNOS deficient mice thus providing further evidence that the anti-inflammatory effects of statins are essentially NO-dependent.

In order to further investigate the mechanism by which statins exert their anti-inflammatory effects, we examined the effect of intraperitoneal administration of mevalonic acid on leukocyte-endothelium interactions in rosuvastatin treated animals. Prior in vitro studies have shown that mevalonic acid reverses statin induced upregulation of eNOS (Endres et al., 1998; Laufs et al., 1998). Our in vivo results are consistent with these reports, as demonstrated by the fact that the anti-inflammatory properties of rosuvastatin are blocked by concomitant administration of mevalonic acid to the rat. These data indicate that inhibition of the mevalonic acid biosynthesis by statins is likely to be one of the key mechanisms by which statins upregulate eNOS activity in endothelial cells. In this regard, statins have been shown to exert beneficial NO promoting effects by inhibiting the biosynthesis of mevalonate (the major precursor of cholesterol) and of the isoprenoid geranylgeranylpyrophosphate (GGPP) (Laufs & Liao, 1998). GGPP is important in the post-translational modification of a variety of proteins including eNOS, and RAS-like proteins such as Rho (Laufs & Liao, 2000). Inhibition of Rho results in a 3 fold increase in eNOS and nitrite generation, since Rho is an inhibitor of NO generation (Laufs & Liao, 1998).

This study provides evidence that the new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, rosuvastatin (Havekes, 2000), exerts important anti-inflammatory effects in addition to its lipid-lowering actions. These anti-inflammatory effects are eNOS dependent and are associated with inhibition of endothelial cell adhesion molecules under normocholesterolemic conditions. To our knowledge, this is the first in vivo evidence showing that administration of mevalonic acid is able to block the anti-inflammatory actions of statins, thus targeting mevalonic acid as a key factor for down-regulating eNOS activity in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Research Grant no. 0050816U from the AHA. T.J. Stalker is supported by NIH Training Grant no. HL07599. Rosuvastatin (CRESTOR™) was generously provided by AstraZeneca U.K. Limited.

Abbreviations

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- HMG-CoA

hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A

- L-NAME

NG-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester

- NO

nitric oxide

- WBC

white blood cell

References

- ALBERTS A.W. Discovery, biochemistry and biology of lovastatin. Am. J. Cardiol. 1988;62:10J–15J. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(88)90002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORDERS J.L., GRANGER H.J. An optical doppler intravital velocimeter. Microvasc. Res. 1984;27:117–127. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(84)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVENPECK K.L., GAUTHIER T.W., LEFER A.M. Inhibition of endothelial-derived nitric oxide promotes P-selectin expression and actions in the rat microcirculation. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1050–1058. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DELANTY N., VAUGHAN C.J. Vascular effects of statins in stroke. Stroke. 1997;28:2315–2320. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.11.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENDRES M., LAUFS U., HUANG Z., NAKAMURA T., HUANG P., MOSKOWITZ M.A., LIAO J.K. Stroke protection by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase inhibitors mediated by endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:8880–8885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAUTHIER T.W., DAVENPECK K.L., LEFER A.M. Nitric oxide attenuates leukocyte-endothelial interaction via P- selectin in splanchnic ischemia-reperfusion. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:G562–G568. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.267.4.G562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUO J.P., MUROHARA T., BUERKE M., SCALIA R., LEFER A.M. Direct measurement of nitric oxide release from vascular endothelial cells. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996;81:774–779. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.2.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAVEKES L. New HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor ZD4522 lowers plasma lipids and production in eNOS−/− eider transgenic mice. Atherosclerosis. 2000;151:172. [Google Scholar]

- KUBES P., SUZUKI M., GRANGER D.N. Nitric oxide: an endogenous modulator of leukocyte adhesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:4651–4655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAUFS U., LA FATA V., PLUTZKY J., LIAO J.K. Upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by HMG CoA reductase inhibitors. Circulation. 1998;97:1129–1135. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.12.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAUFS U., LIAO J.K. Post-transcriptional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase mRNA stability by Rho GTPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:24266–24271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAUFS U., LIAO J.K. Targeting rho in cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 2000;87:526–528. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.7.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEFER A.M. Nitric oxide: nature's naturally occurring leukocyte inhibitor. Circulation. 1997;95:553–554. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEFER A.M., CAMPBELL B., SHIN Y.K., SCALIA R., HAYWARD R., LEFER D.J. Simvastatin preserves the ischemic-reperfused myocardium in normocholesterolemic rat hearts. Circulation. 1999;100:178–184. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEFER A.M., LEFER D.J. Pharmacology of the endothelium in ischemia-reperfusion and circulatory shock. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1993;33:71–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVINE G.N., KEANEY J.F., Jr, VITA J.A. Cholesterol reduction in cardiovascular disease. Clinical benefits and possible mechanisms. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:512–521. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502233320807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCEVER R.P. GMP-140: a receptor for neutrophils and monocytes on activated platelets and endothelium. J. Cell. Biochem. 1991;45:156–161. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240450206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUROHARA T., SCALIA R., LEFER A.M. Lysophosphatidylcholine promotes P-selectin expression in platelets and endothelial cells. Possible involvement of protein kinase C activation and its inhibition by nitric oxide donors. Circ. Res. 1996;78:780–789. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.5.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATEL K.D., ZIMMERMAN G.A., PRESCOTT S.M., MCEVER R.P., MCINTYRE T.M. Oxygen radicals induce human endothelial cells to express GMP-140 and bind neutrophils. J. Cell Biol. 1991;112:749–759. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRUEFER D., SCALIA R., LEFER A.M. Simvastatin inhibits leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions and protects against inflammatory processes in normocholesterolemic rats. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999;19:2894–2900. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.12.2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., PALMER R.M., MONCADA S. The anti-aggregating properties of vascular endothelium: interactions between prostacyclin and nitric oxide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987;92:639–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SACKS F.M., PFEFFER M.A., MOYE L.A., ROULEAU J.L., RUTHERFORD J.D., COLE T.G., BROWN L., WARNICA J.W., ARNOLD J.M., WUN C.C., DAVIS B.R., BRAUNWALD E. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335:1001–1009. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCALIA R., GEFEN J., PETASIS N.A., SERHAN C.N., LEFER A.M. Lipoxin A4 stable analogs inhibit leukocyte rolling and adherence in the rat mesenteric microvasculature: role of P-selectin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:9967–9972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCANDINAVIAN SIMVASTATIN SURVIVAL STUDY GROUP Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEPHERD J., COBBE S.M., FORD I., ISLES C.G., LORIMER A.R., MACFARLANE P.W., MCKILLOP J.H., PACKARD C.J. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1301–1307. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TREASURE C.B., KLEIN J.L., WEINTRAUB W.S., TALLEY J.D., STILLABOWER M.E., KOSINSKI A.S., ZHANG J., BOCCUZZI S.J., CEDARHOLM J.C., ALEXANDER R.W. Beneficial effects of cholesterol-lowering therapy on the coronary endothelium in patients with coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:481–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502233320801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEYRICH A.S., BUERKE M., ALBERTINE K.H., LEFER A.M. Time course of coronary vascular endothelial adhesion molecule expression during reperfusion of the ischemic feline myocardium. J. Leuk. Biol. 1995;57:45–55. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]