Abstract

The GABA-related compound nipecotic acid is commonly used to inhibit GABA uptake. This report shows that nipecotic acid can also directly activate GABAA-like chloride channels.

When applied to outside-out patches of paraventricular neurones, nipecotic acid (1 mM) activated inward unitary currents (approximately 3 pA at a holding potential of −60 mV, ECl+44 mV).

The EC50 for ion channel activation was approximately 300 μM, 3 fold greater than that found for GABA itself in this preparation.

The nipecotic acid activated channels had similar conductance and kinetic properties to those of GABA activated channels in the same patches, reversed near ECl and were inhibited by bicuculline (3 μM).

This study indicates that for experiments in which relatively high concentrations of nipecotic acid are used, possible direct GABAA receptor agonist properties should be considered.

Keywords: Nipecotic acid, GABA, single channel, PVN, paraventricular, parvocellular, mediocellular

Introduction

Nipecotic acid is a GABA-related compound which has been widely used as an inhibitor of both glial and neuronal GABA uptake (Krogsgaard-Larsen & Johnston, 1975; Johnston et al., 1976; Brown & Galvan, 1977; Massey & Redburn, 1982; Brennan & Haywood, 1985; Pfeiffer et al., 1996; Galindo et al., 1999; Ciranna et al., 2000). Its conventional mechanism of action is believed to be the competitive inhibition of the GABA transporter (GAT, Masson et al., 1999). GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the mammalian CNS and so inhibition of its uptake is expected to lead to a facilitation of inhibitory neurotransmission (Sivilotti & Nistri, 1991). Exploiting this mechanism, the lipophilic nipecotic acid derivative N-4,4-di(3-methylthien-2-yl)but-3-enyl) nipecotic acid has recently entered clinical trials as an antiepileptic agent (Suzdak & Jansen, 1995; Beydoun, 1997; Adkins & Noble, 1998). Both in vivo and in vitro experiments have, as expected, revealed that application of nipecotic acid to various brain preparations (in the absence of exogenous GABA agonists); induces inward current (Draguhn & Heinemann, 1996), increases whole-cell conductance (Honmou et al., 1995), inhibits neuronal firing (Reith & Sillar, 1999; Ciranna et al., 2000) and catecholamine accumulation (Proll & Morgan, 1983). Although Draguhn & Heinemann (1996) suggested that nipecotic acid induced currents could be due to a direct action on GABAA receptors, all these effects are consistent with an increase in local concentrations of endogenously released GABA. It is, however, difficult in an in vivo or in vitro slice preparation, to distinguish between such ‘GABA overflow' and any direct agonist-like action of nipecotic acid. The mediocellular paraventricular nucleus (PVN) is an area of the hypothalamus rich in GABAergic innervation (Boudaba et al., 1996; Hermes et al., 1996; Bains & Ferguson, 1997; Tasker et al., 1998; Zhang & Patel, 1998), and tonic activity of these GABA neurones is involved in regulation of the cardiovascular system (Martin & Haywood, 1993; Goren et al., 1996). Our group has also observed that addition of nipecotic acid to slices of the PVN can evoke a small decrease in neuronal firing frequency and an increase in whole-cell conductance (unpublished observations). Again, however, these effects could be explained by either block of the GABA uptake protein, or a GABA mimetic action of nipecotic acid. The aim of this work was to investigate the action of nipecotic acid on cell free membrane patches, and determine whether nipecotic acid can directly gate GABAA ion channels.

Methods

Preparation of tissue

Slices of paraventricular nucleus were prepared using the methods of Barrett-Jolley et al. (2000). Briefly, rats were killed by an overdose of anaesthetic (Sagital) and the brain removed to iced low-Na+ high-sucrose artificial cerebrospinal fluid (low-Na+-ACSF). The general area of the hypothalamus was blocked and glued in the chamber of a Campden Instruments Vibroslice. The chamber was maintained at 0–4°C by frequent addition of iced low-Na+-ACSF. One hundred and fifty to 200 μm slices were cut and removed to a multiwell culture dish containing normal ACSF. The culture dish was incubated at 35–37°C and bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2, for at least 1 h prior to recording.

Electrophysiology

Following incubation at 35–37°C, slices were transferred to a glass-bottomed recording chamber and perfused at 3 ml min−1 with a HEPES buffered flow solution at 26–28°C. Visualization of PVN neurones was made with a Nikon E600FN Eclipse upright microscope equipped with near infrared DIC optics. During pharmacological experiments, patch pipettes were lifted clear of the slice and placed near the mouth of a glass pipette carrying the flow solution. Patch-clamp electrodes were fabricated from GC150F electrode glass (Clark Electromedical) and pulled to a final (filled) resistance of 5–10 ≡Ω on a Brown-Flaming MP P-80 horizontal puller (Sutter Instrument Co.).

Analysis

Patch-clamp recording was made with an Axon Instruments Axopatch 200A integrating patch-clamp amplifier, filtered at 2–3 kHz and digitized with a DigiData 1200 board (Axon Instruments).

Membrane current was measured in one of two ways; when channel activity was low (e.g., only one channel was observed) current was estimated as Po×i, where i was the unitary current amplitude, and Po the average open probability of the channel per acquisition sweep (approximately 1 s per sweep). Alternatively, when membrane current was greater, it was measured simply as the peak average current.

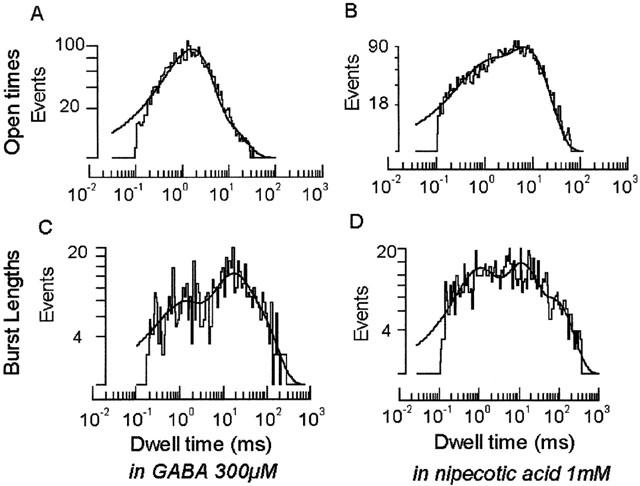

‘Maximum' current is difficult to assess in single channel experiments, and so data for dose response curves were normalized to a fixed reference concentration in each patch. pD2 values were then obtained by fits to the mean normalized data with;

|

where r was the relative response, m the maximum response, c the concentration and h the Hill slope (Barrett-Jolley & McPherson, 1998). Errors for the pD2 values quoted in the text are those returned by the non-linear least squares fitting algorithms of MicroCal Origin 6.0.

Kinetic analysis followed the procedures of Barrett-Jolley & Davies (1997). Briefly data was digitally filtered to 1 kHz, dwell times were log binned according to the methods of Sigworth & Sine (1987) and fitted with the standard maximum likelihood probability density function. Bursts were defined by the preceding closed time exceeding a critical time, tc. This critical time was calculated for each patch by equalizing the proportions of intraburst closures misclassified as longer than tc and of interburst closures misclassified as shorter than tc.

Analysis was performed with the Axgox suite of programs, written by Noel Davies (University of Leicester, Davies, 1993) and with MicroCal Origin. Data is displayed as ±s.e. unless otherwise stated n refers to the number of patches.

Solutions

‘Low−Na+ ACSF' (mM): sucrose 250, KCl 2.5, NaHCO3 26, glucose 10, NaH2PO4 1.25, CaCl2 1, MgCl2 1.2. pH 7.4 when bubbled with carbogen 95/5. ‘Normal ACSF' (mM): NaCl 125, KCl 2.5, NaHCO3 26, glucose 10, NaH2PO4 1.25, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1.2, pH 7.4 when bubbled with carbogen 95/5. Bath solution (mM): NaSO4 60, NaCl 20, KCl 3, MgCl2 3.5, glucose 11, HEPES 10 (pH 7.4 with NaOH). Pipette solution (mM): CsCl 140, NaCl 10, EGTA 5, MgCl2 1, HEPES 5 (pH 7.2 with KOH).

Chemicals

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma. GABA and nipecotic acid were prepared as 1000× stocks in deionized water on the day of each experiment. Bicuculline was prepared as a 10,000× stock in DMSO. 1 : 1000 DMSO is inactive on these membrane patches or ion conductances.

Results

Outside-out patches were drawn from neurones in the parvocellular/mediocellular region of the PVN and moved approximately 1 mm away from the slice. The patches were then moved to near the opening of a perfusion tip and continuously bathed in fresh flow solution to ensure that they were not affected by GABA released from the slice (in some cases the slice was removed from the tissue chamber altogether).

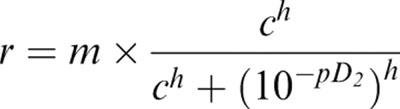

Application of 1 mM nipecotic acid to patches held at −60 mV evoked GABA-like inward currents (−0.57±0.14 pA n=11, Figure 1A). The peak average current evoked by 1 mM nipecotic acid was similar to that evoked by a near maximal dose (300 μM) of GABA (Inipecotic acid / IGABA ratio 1.8±0.3, n=4; non-responsive patches excluded). I found no patches that responded to GABA, but not to nipecotic acid.

Figure 1.

Activation of ion channels by nipecotic acid. (A) A compressed record. Application of GABA (300 μM) or nipecotic acid (Nip 1 mM), where indicated by the horizontal bars, activates brief inward channel events (inward events are represented by downward deflections; note that the amplitudes appear variable due to the compression routine used for display). (B) Time expanded record of GABA activated channels. Both (B) and (C) are taken from (A) at appropriate points. The scale bar for B applies to both B and C.

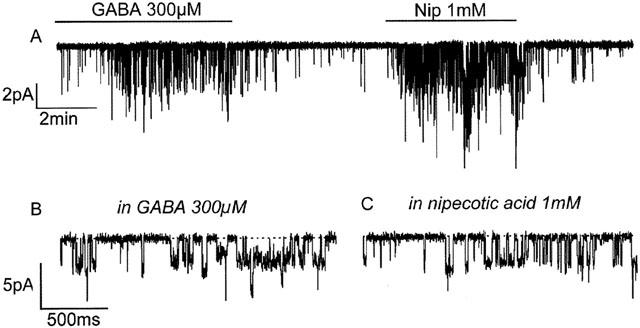

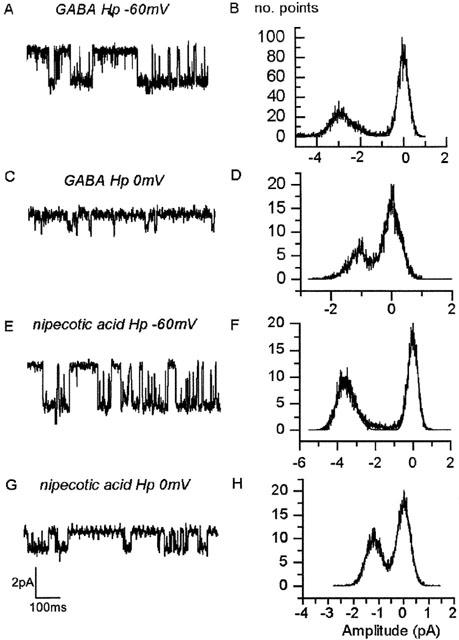

The nipecotic acid activated channels appeared similar to those activated by GABA in terms of their single channel amplitude (Hp-60 mV: nipecotic acid: −3.0±0.68(SD) pA n=5 vs GABA: −2.5±0.75(SD) pA n=6, Figure 2). In some patches, other, much less frequent conductance levels were observed, but these have been excluded from the analysis. In terms of their kinetics, 1 mM nipecotic acid evoked events were somewhat longer than those of 300 μM GABA (Hp-60 mV: nipecotic acid corrected mean open time, cmot: 6.0±0.6 ms n=4 vs GABA cmot: 3.0±0.2 ms n=3, Figure 3), but burst lengths were similar (nipecotic acid: 32.7±1.8 ms n=4 vs GABA: 25.6±2.5 ms n=3), with the number of openings per burst slightly increased (nipecotic acid: 3.7±0.3 n=4 vs GABA: 5.5±0.7 n=3).

Figure 2.

All points amplitude histograms for GABA and Nipecotic acid activated single channels. All points amplitude histograms for 300 μM GABA (A, B, C and D) and 1 mM Nipecotic acid (E, F, G and H) activated channels at −60 mV (A, B, E and F) and 0 mV (C, D, G and H). The histograms shown have each been fit with a two peak Gaussian curve (solid lines, Microcal Origin), fit parameters were as follows; B., peak 0 pA width 0.51 pA and peak −2.84 pA width 1.1 pA. D., peak −0.02 pA width 0.55 pA and peak −1.07 pA width 0.69 pA. F., peak −0.01 pA width 0.5 pA and peak −3.54 pA width 0.98 pA and H., peak −0.01 pA width 0.54 pA and peak −1.17 pA width 0.65 pA. In each case ‘width'; is equivalent to the standard deviation for the fitted Gaussian; mean values are given in the text (the data illustrated comes from different patches).

Figure 3.

Kinetics of nipecotic acid activated ion channels. Kinetic analysis of nipecotic acid (1 mM) and GABA (300 μM) activated channels. (A) and (B) show open dwell times–fitted with two exponentials (GABA open: τ1 1.5 ms, τ2 6.1 ms; nipecotic acid open: τ1 0.8 ms, τ2 6.9; mean values are given in the text). (C) and (D) show burst lengths–fitted with three exponentials (GABA burst lengths: τ1 0.9 ms, τ2 13.7 ms, τ3 48.2 ms; nipecotic acid burst lengths: τ1 0.9 ms, τ2 10.98 ms, τ3 75.96 ms; mean values are given in the text).

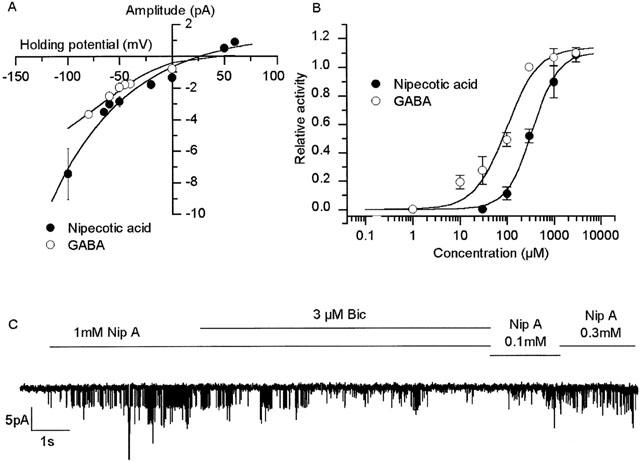

Application of nipecotic acid to patches held at differing membrane potentials allows estimation of the reversal potential and conductance (Figure 4). The channels reverse near ECl (+44 mV) and show slight inward rectification. At −60 mV chord conductance was 24±1.0 pS (n=3) for GABA and 29±1.3 pS (n=4) for nipecotic acid. GABA itself is known to activate both chloride and potassium channels by acting at GABAA and GABAB (G-protein coupled) receptors respectively. The possibility that nipecotic acid activated K+ channels rather than Cl− channels can be excluded because, under these recording conditions EK is near −50 mV and so K+ channel currents would be outward at 0 mV.

Figure 4.

Nipecotic acid activates GABA chloride channels. (A) Current-voltage curves for GABA and nipecotic acid from a number of experiments similar to those of Figure 3. (B) Concentration effect curves for GABA (open circles) and nipecotic acid (filled circles) activation of channels. The smooth lines are Hill equations fitted to the mean data with MicroCal Origin (GABA pD2 3.46±0.05, h 1.60±0.2 and nipecotic acid pD2 4.04±0.11, h 1.44±0.46, n=11, see Methods). (C) Bicuculline (‘Bic'), and nipecotic acid (‘Nip A') were added at the concentrations stated, where indicated by the horizontal bars. Bicuculline reversibly inhibits nipecotic acid activated channels.

Although nipecotic acid is frequently used as an uptake blocker at concentrations of 1 mM, it actually inhibits GABA uptake with a IC50 of approximately 10 μM (Ruiz et al., 1994). To investigate the concentration dependence of nipecotic acid on channel activity, concentration effect curves were constructed to both GABA and nipecotic acid (Figure 4B). Nipecotic acid (pD2 3.5, Figure 4B) was somewhat less potent than GABA (pD2 4.0, Figure 4B).

The evidence detailed above implies that nipecotic acid activates a chloride current. To examine if this current is carried by GABAA channels, some experiments were repeated in the presence of the selective GABAA receptor antagonist, bicuculline (Figure 4C). Three μM bicuculline inhibited the action of nipecotic acid by 80±4%, n=4, suggesting that nipecotic acid may act as an agonist at a GABAA-receptor GABA binding site.

Discussion

The GABA uptake blocker nipecotic acid is a widely used research tool in both in vitro and in vivo experiments, however the present work, using single channel recording from isolated membrane patches, suggests that nipecotic acid can also act as a GABA agonist. This action would be difficult to detect in certain in vivo or in vitro (brain slice) experiments.

This work clearly shows the activation of GABAA-like channel currents by nipecotic acid. Nipecotic acid has previously been found to activate inward currents through GAT proteins in catfish horizontal retinal cells (Cammack & Schwartz, 1993). Theoretical predictions of the microscopic currents expected for GAT transporter proteins themselves are 10−17 to 10−19 pA (Masson et al., 1999), nevertheless, Cammack & Schwartz (1996) identified 1–1.4 pA inward unitary currents associated with GAT-1 proteins in transfected HEK293 cells (Hp 50 pA). These currents remained in the absence of both GABA and chloride and are thought to represent a leak state of GAT-1. The currents activated by nipecotic acid in this study were, however, similar in size and kinetics to those activated by GABA itself, reversed near to ECl and were sensitive to (although not totally abolished by) bicuculline.

The concentration of nipecotic acid which I have shown here to act as an agonist is well above the IC50 for block of the GABA uptake pathways (IC50: approximately 10 μM: Ruiz et al., 1994; Mantz et al., 1994; Falch et al., 1999. Here, pD2 3.54 equivilent to EC50 ∼300 μM), but in the order of the concentrations frequently used (Brown & Galvan, 1977; Massey & Redburn, 1982; Fern et al., 1995; Pfeiffer et al., 1996 (1–5 mM); Arnarsson & Eysteinsson, 1997; Galinado et al., 1999).

The lipophilic derivative of nipecotic acid, (R)-N-(4,4-di-(3-methylthien-2-yl)but-3-enyl)nipecotic acid, which recently entered clinical trails as an anti-epileptic agent, is a more potent blocker of GABA uptake than nipecotic acid itself (IC50 <1 μM: Pavia et al., 1992), however, it remains to be seen whether this compound retains any GABA agonist - like potency. Further experiments are also required to determine whether the agonist action of nipecotic acid is general to all GABAA receptors, or specific to one particular subtype.

In conclusion, the GABA uptake inhibitor nipecotic acid appears to also to act as a GABAA receptor agonist at concentrations of 1 mM and below. Caution should be used when using this compound as it may be difficult to distinguish between its GAT inhibiting and GABA mimetic actions.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the British Heart Foundation Fellowship awarded to R. Barrett-Jolley. I thank Prof John Coote, Dr Caroline Dart and Dr Mike Lacey for helpful discussions and Dr Noel Davies for software help.

Abbreviations

- cmot

corrected mean open time

- ECl

chloride equilibrium potential

- EK

equilibrium potential for potassium ions

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GAT

GABA transporter

References

- ADKINS J.C., NOBLE S. Tiagabine–A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential in the management of epilepsy. Drugs. 1998;55:437–460. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199855030-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARNARSSON A., EYSTEINSSON T. The role of GABA in modulating the Xenopus electroretinogram. Visual Neurosci. 1997;14:1143–1152. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800011834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAINS J.S., FERGUSON A.V. Nitric oxide regulates NMDA-driven GABAergic inputs to type I neurones of the rat paraventricular nucleus. J. Physiol. 1997;499:733–746. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRETT-JOLLEY R., DAVIES N.W. Kinetic analysis of the inhibitory effect of glibenclamide on K(ATP) channels of mammalian skeletal muscle. J. Memb. Biol. 1997;155:257–262. doi: 10.1007/s002329900178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRETT-JOLLEY R., MCPHERSON G.A. Characterisation of K(ATP) channels in intact mammalian skeletal muscle fibres. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:1103–1110. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRETT-JOLLEY R., PYNER S., COOTE J.H. Measurement of voltage-gated potassium currents in identified spinally-projecting sympathetic neurones of the paraventricular nucleus. J. Neurosci. Meth. 2000;102:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEYDOUN A. Monotherapy trials of new antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 1997;38 Suppl. 9:S21–S31. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb05201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOUDABA C., SZABO K., TASKER J.G. Physiological mapping of local inhibitory inputs to the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:7151–7160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-22-07151.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRENNAN T.J., HAYWOOD J.R. Gabaergic inhibition of hypertonic saline-induced vasopressin-dependent hypertension. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1985;233:663–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWN D.A., GALVAN M. Influence of neuroglial transport on the action of gamma-aminobutyric acid on mammalian ganglion cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1977;59:373–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1977.tb07502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMMACK J.N., SCHWARTZ E.A. Ions required for the electrogenic transport of GABA by horizontal cells of the catfish retina. J. Physiol. 1993;472:81–102. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMMACK J.N., SCHWARTZ E.A. Channel behavior in a gamma-aminobutyrate transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:723–727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIRANNA L., LICATA F., VOLSI G.L., SANTANGELO F. Neurotransmitter-mediated control of neuronal firing in the red nucleus of the rat: Reciprocal modulation between noradrenaline and GABA. Exp. Neurol. 2000;163:253–263. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIES N.W. A suite of programs for acquisition and analysis of voltage-clamp and patch-clamp data developed using the Axobasic library. J. Physiol. 1993;459P:111. [Google Scholar]

- DRAGUHN A., HEINEMANN U. Different mechanisms regulate IPSC kinetics in early postnatal and juvenile hippocampal granule cells. J. Neurophysiol. 1996;76 6:3983–3993. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FALCH E., PERREGAARD J., FROLUND B., SOKILDE B., BUUR A., HANSEN L.M., FRYDENVANG K., BREHM L., BOLVIG T., LARSSON O.M., SANCHEZ C., WHITE H.S., SCHOUSBOE A., KROGSGAARD-LARSEN P. Selective inhibitors of glial GABA uptake: Synthesis, absolute stereochemistry, and pharmacology of the enantiomers of 3-hydroxy-4-amino-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-1,2-benzisoxazole (exo-THPO) and analogues. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:5402–5414. doi: 10.1021/jm9904452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERN R., WAXMAN S.G., RANSOM B.R. Endogenous GABA attenuates CNS white-matter dysfunction following anoxia. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:699–708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00699.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALINDO A., DEL ARCO A., MORA F. Endogenous GABA potentiates the potassium-induced release of opamine in striatum of the freely moving rat: A microdialysis study. Brain Res. Bull. 1999;50:209–214. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOREN Z., ASLAN N., BERKMAN K., OKTAY S. Onat, F. The role of amygdala and hypothalamus in GABA(A) antagonist bicuculline-induced cardiovascular responses in conscious rats. Brain Res. 1996;722:118–124. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERMES M.L., CODERRE E.M., BUIJS R.M., RENAUD L.P. GABA and glutamate mediate rapid neurotransmission from suprachiasmatic nucleus to hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus in rat. J. Physiol. 1996;496:749–757. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HONMOU O., KOCSIS J.D., RICHERSON G.B. Gabapentin potentiates the conductance increase induced by nipecotic acid in CA1 pyramidal neurons in vitro. Epilepsy Res. 1995;20:193–202. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(94)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSTON G.A., KROGSGAARD-LARSEN P., STEPHANSON A.L., TWITCHIN B. Inhibition of the uptake of GABA and related amino acids in rat brain slices by the optical isomers of nipecotic acid. J. Neurochem. 1976;26:1029–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1976.tb06488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KROGSGAARD-LARSEN P., JOHNSTON G.A. Inhibition of GABA uptake in rat brain slices by nipecotic acid, various isoxazoles and related compounds. J. Neurochem. 1975;25:797–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1975.tb04410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANTZ J., LAUDENBACH V., LECHARNY J.B., HENZEL D., DESMONTS J.M. Riluzole, a novel antiglutamate, blocks GABA uptake by striatal synaptosomes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;257:R7–R8. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90716-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN D.S., HAYWOOD J.R. Hemodynamic-responses to paraventricular nucleus disinhibition with bicuculline in conscious rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;265:H1727–H1733. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.5.H1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASSEY S.C., REDBURN D.A. A tonic gamma-aminobutyric acid-mediated inhibition of cholinergic amacrine cells in rabbit. J. Neurosci. 1982;2:11:1633–1643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-11-01633.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASSON J., SAGNE C., HAMON M., EL MESTIKAWY S. Neurotransmitter transporters in the central nervous system. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999;51:439–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAVIA M.R., LOBBESTAEL S.J., NUGIEL D., MAYHUGH D.R., GREGOR V.E., TAYLOR C.P., SCHWARZ R.D., BRAHCE L., VARTANIAN M.G. Structure-activity studies on benzhydrol-containing nipecotic acid and guvacine derivatives as potent, orally-active inhibitors of GABA uptake. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:4238–4248. doi: 10.1021/jm00100a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFEIFFER M., DRAGUHN A., MEIERKORD H., HEINEMANN U. Effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonists and GABA uptake inhibitors on pharmacosensitive and pharmacoresistant epileptiform activity in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:569–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PROLL M.A., MORGAN W.W. Use of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-transaminase inhibitors and a GABA uptake inhibitor to investigate the influence of GABA neurons on dopamine-containing amacrine cells of the rat retina. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1983;227:627–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REITH C.A., SILLAR K.T. Development and role of GABA(A) receptor-mediated synaptic potentials during swimming in postembryonic Xenopus laevis tadpoles. J. Neurophysiol. 1999;82:3175–3187. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUIZ M., EGAL H., SARTHY V., QIAN X., SARKAR H.K. Cloning, expression, and localization of a mouse retinal gamma-aminobutyric acid transporter. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1994;35:4039–4048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIGWORTH F.J., SINE S.M. Data transformations for improved display and fitting of single-channel dwell time histograms. Biophys. J. 1987;52:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83298-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIVILOTTI L., NISTRI A. GABA receptor mechanisms in the central nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 1991;36:35–92. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(91)90036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUZDAK P.D., JANSEN J.A. A review of the preclinical pharmacology of tiagabine: a potent and selective anticonvulsant GABA uptake inhibitor. Epilepsia. 1995;36:612–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb02576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TASKER J.G., BOUDABA C., SCHRADER L.A. Local glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic circuits and metabotropic glutamate receptors in the hypothalamic paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1998;449:117–121. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4871-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG K., PATEL K.P. Effect of nitric oxide within the paraventricular nucleus on renal sympathetic nerve discharge: role of GABA. Am. J. Physiol.-Reg. I. 1998;44:R728–R734. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.3.R728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]