Abstract

We examined the effect of 3-isobutyryl-2-isopropylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyridine (ibudilast), which has been clinically used for bronchial asthma and cerebrovascular disorders, on cell viability induced in a model of reperfusion injury.

Ibudilast at 10 – 100 μM significantly attenuated the H2O2-induced decrease in cell viability.

Ibudilast inhibited the H2O2-induced cytochrome c release, caspase-3 activation, DNA ladder formation and nuclear condensation, suggesting its anti-apoptotic effect.

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors such as theophylline, pentoxyfylline, vinpocetine, dipyridamole and zaprinast, which increased the guanosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cyclic GMP) level, and dibutyryl cyclic GMP attenuated the H2O2-induced injury in astrocytes.

Ibudilast increased the cyclic GMP level in astrocytes.

The cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase inhibitor KT5823 blocked the protective effects of ibudilast and dipyridamole on the H2O2-induced decrease in cell viability, while the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase inhibitor KT5720, the cyclic AMP antagonist Rp-cyclic AMPS, the mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase inhibitor PD98059 and the leukotriene D4 antagonist LY 171883 did not.

KT5823 also blocked the effect of ibudilast on the H2O2-induced cytochrome c release and caspase-3-like protease activation.

These findings suggest that ibudilast prevents the H2O2-induced delayed apoptosis of astrocytes via a cyclic GMP, but not cyclic AMP, signalling pathway.

Keywords: Ibudilast, apoptosis, cyclic GMP, caspase-3, cytochrome c release, astrocyte

Introduction

3-Isobutyryl-2-isopropylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyridine (ibudilast) has vasodilating, anti-platelet and anti-leukotriene effects (Fukuyama et al., 1993; Kawasaki et al., 1992; Ohashi et al., 1986a, 1986b), and it is widely used in Japan for bronchial asthma and cerebrovascular disorders. Previous in vitro studies showing that ibudilast prevents exicitotoxicity in cultured oligodendroglial cells (Yoshioka et al., 1998; 2000) and neurons (Tominaga et al., 1996) may support the effectiveness of ibudilast in cerebrovascular diseases. These effects may be mediated partly by an increase in the cyclic AMP level via an inhibition of phosphodiesterase (PDE) (Souness et al., 1994) or a decrease in intracellular Ca2+ concentration (Yanase et al., 1996). On the other hand, there is little information on the effect of ibudilast on astrocytic injury, although astrocytes play physiologically and pathologically important roles in neuronal activities (Murphy & Pearce, 1987; McCarthy & Salm, 1991). Recent studies show that astrocytic apoptosis may play a role in brain injuries such as spinal trauma and cerebral ischaemia (Gallo & Ghiani, 2000; Ju et al., 2000; Liu et al., 1997; Pantoni et al., 1996; Petito et al., 1998).

We previously showed that incubation of cultured rat astrocytes with Ca2+-containing medium after exposure to Ca2+-free medium caused an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration followed by delayed cell death, including apoptosis (Matsuda et al., 1996; 1997; Takuma et al., 1999). This injury is considered to be an in vitro model of ischaemia/reperfusion injury, because a similar paradoxical change in extracellular Ca2+ concentration is reported in ischaemic brain tissue (Siemkowicz & Hansen, 1981; Silver & Erecinska, 1992; Kristian et al., 1994). Subsequently, we have found that the Ca2+ reperfusion injury was mimicked by reperfusion after exposure to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Takuma et al., 1999). This injury, like cerebral ischaemic injury, was protected by heat shock proteins (Takuma et al., 1996b). The reperfusion injury models using Ca2+ depletion and H2O2 exposure may contribute to clarification of the mechanisms of drugs which ameliorate ischaemia/reperfusion-induced brain dysfunction. Our recent studies using the astrocytic injury models show that the neuroprotective compounds FK506 (Matsuda et al., 1998), NGF (Takuma et al., 2000a), (1R)-1-benzo[b]thiophen-5-yl-2-[2-(diethylamino)ethoxy]ethan-1-ol hydrochloride (T-588) (Takuma et al., 2000a), and 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-(10-hydroxydecyl)-1,4-benzoquinone (CV-2619) (Takuma et al., 2000b) inhibit astrocytic apoptosis. The effects of these drugs, which are mediated by calcineurin, the mitogen-activated protein (MAP)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) kinase and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase pathways, draw attention to other mechanisms likely to be important in astrocytic injury.

In this study, we examined the effect of ibudilast on reperfusion injury after exposure to H2O2-containing medium in cultured rat astrocytes and studied the mechanism underlying the effect of ibudilast. The present study demonstrates that ibudilast has an anti-apoptotic effect in cultured astrocytes and cyclic GMP, but not cyclic AMP, plays a role in the downstream mechanism.

Methods

Materials

Drugs were obtained from the following sources: mouse anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein antiserum, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), theophylline, pentoxyfylline, vinpocetine, dipyridamole, zaprinast, LY 171883, dibutyryl cyclic GMP, isolectin B4 (Biotin labelled), Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.); Rp-cyclic AMPS, RBI (Natick, MA, U.S.A.); cilostamide, KT5823, KT5720, Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.); BIOTRAK cyclic GMP enzyme immunoassay system, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. U.K., Ltd. (Buckinghamshire, U.K.); mouse anti-cytochrome c antibody (clone 7H8.2C12), Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.); 7-amino-4-methyl-coumarin, acetyl-L-aspartyl-L-glutamiyl-L-valyl-L-aspartic acid α-(4-methyl-coumaryl-7-amide) (Ac-DEVD-MCA), Peptide Institute, Inc. (Osaka, Japan); Eagle's minimum essential medium, Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), tissue culture ware, Iwaki Glass Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Ibudilast was a gift from Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tochigi, Japan). All other chemicals used were of the highest purity commercially available. All experiments were performed according to the guiding principles for the care and use of laboratory animals approved by the Japanese Pharmacological Society.

Astrocytic culture

Astrocytes were isolated from the cerebral cortices of 1-day-old Wistar rats as previously reported (Takuma et al., 1994; 1995; 1996a). Briefly, the tissue was dissociated with protease and cultured in minimum essential medium containing 10% foetal calf serum and 2 mM of glutamine. Cells were plated in 75-ml tissue culture flasks, split once upon confluence, and plated in 24-well (for MTT assay) and 96-well (for cyclic GMP and caspase assays) plastic tissue culture plates and 60-mm (for DNA ladder) and 100-mm (for cytochrome c release) plastic tissue culture dishes. For measurements of caspase activity and cyclic GMP level, the cells were seeded in flat bottom microtiter plates. The second cultures were grown for 14 – 20 days in all experiments. The cells were routinely >95% positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein, and approximately 2% of the cells were microglia, based on positive isolectin B4 staining.

Cell viability

Experiments of H2O2-induced injury were carried out using confluent astrocytes in foetal calf serum-free medium as previously reported (Takuma et al., 2000a, 2000b). Cells were exposed to H2O2 (100 μM)-containing Earle's solution for 30 min, and then incubated with normal Earle's solution without H2O2 for the indicated times. Cell viability was determined by MTT reduction activity as previously reported (Matsuda et al., 1996; Takuma et al., 1999). MTT reduction activity is expressed as a percentage of the control. Dibutyryl cyclic GMP, Rp-cAMP, pentoxyfylline and theophylline were dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline. Other drugs were dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide and diluted with Earle's solution to make the desired final concentration. The final concentration of dimethyl sulphoxide was less than 0.1%, which did not affect the cell viability.

DNA ladder and Hoechst 33342 staining

DNA ladder and Hoechst 33342 staining experiments were carried out to examine the involvement of apoptosis. DNA was extracted and subjected to 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis as previously reported (Takuma et al., 2000a, 2000b). DNA in the gel was stained with ethidium bromide and photographed with the Polaroid instant films (type 667) under u.v. light. To observe individual nuclei, the cells plated on a chamber slide were fixed with 10% formaldehyde and stained with Hoechst 33342 as previously reported (Takuma et al., 1999; 2000b).

Measurement of cytochrome c release

Most apoptotic pathways converge on the activation of a caspase cascade that is amplified by a positive feedback loop involving the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria (Budihardio et al., 1999). Cytosol and membrane fractions were prepared as previously reported (Araya et al., 1998). Briefly, cells plated on 100 mm dishes were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline, scraped off, and collected by centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was suspended in 75 μl of lysis-buffer (in mM: Tris pH 7.4 50, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) 1, ethylene glycolbis (β-amino ethyl ether) tetraacetic acid (EGTA) 1, sucrose 250, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride 1, 2 μg ml−1 leupeptin and 1 μg ml−1 pepstatin A). The homogenate was centrifuged at 105,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of lysis-buffer. The protein contents of the cytosol and membrane fractions were determined by a BioRad DC protein assay (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, U.S.A.), and 15 μg of the sample was subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (15% polyacrylamide). A cytochrome c antibody (1 : 1000) was used for immunoblotting.

Measurement of caspase activity

The activity of caspase-3-like protease in cell lysates was measured using the fluogenic substrate Ac-DEVD-MCA (Armstrong et al., 1997). After treatment, the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in 52.5 μl of buffer A (in mM: HEPES 10 pH 7.4, KCl 42, MgCl2 5, EDTA 1, EGTA 1, dithiothreitol 1, phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride 1, 0.5% CHAPS, 1 μg ml−1 pepstatin A, 5 μg ml−1 aprotinin, and 1 μg ml−1 leupeptin). Then, 50 μl of the lysates were incubated with 150 μl of buffer B (in mM: HEPES 25, EDTA 1, dithiothreitol 3, 0.1% CHAPS, 10% Sucrose) containing 25 μM Ac-DEVD-MCA at 37°C for 1 h. The released 7-amino-4-methyl-coumarin levels were measured with excitation at 355 nm and emission at 460 nm using a Wallac Multilabel counter.

Measurement of cyclic GMP level

Intracellular cyclic GMP level was determined by a competitive enzyme immunoassay according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells plated in 96-well culture plates were washed twice with prewarmed phosphate-buffered saline and treated with Earle's solution containing the drugs at 37°C for 30 min. After removing the medium, 200 μl of lysis-reagent containing 0.5% dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide was added to extract intracellular cyclic GMP. Then, the samples and standards were acetylated and transferred into the appropriate wells of microtiter plates coated with donkey anti-rabbit IgG. The acetylated cyclic GMP was incubated first with rat anti-cyclic GMP antibody at 4°C for 2 h, and then with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated cyclic GMP at 4°C for 1 h. All wells were washed four times and reacted with the substrate. Absorbance at 450 nm were determined by a microtiter plate reader, and a standard curve ranging from 2 – 500 fmolwell−1 was used to calculate unlabelled cyclic GMP in each well. Data are expressed as fmol of cyclic GMP per well.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis of the experimental data was carried out by Student-Newman-Keuls test, Dunnett's t-test or Tukey HSD test, using a software package (Stat View 5.0) for Apple Macintosh.

Results

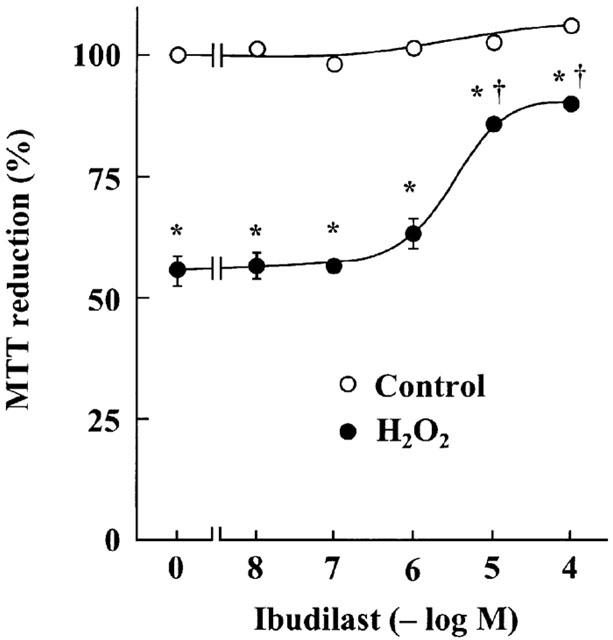

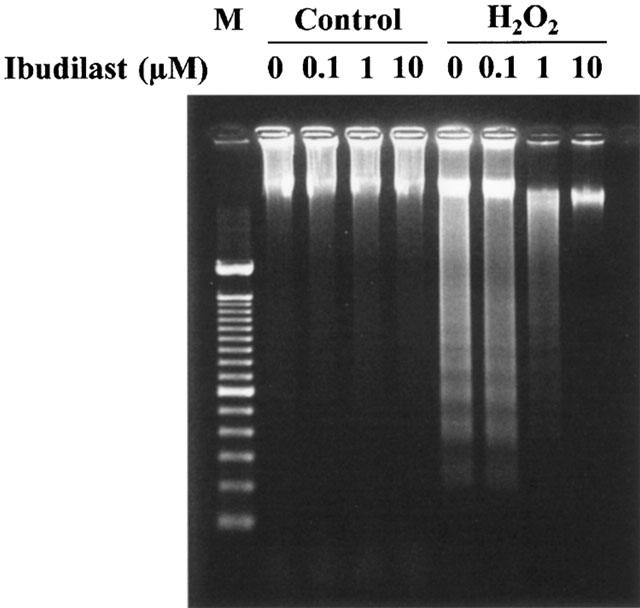

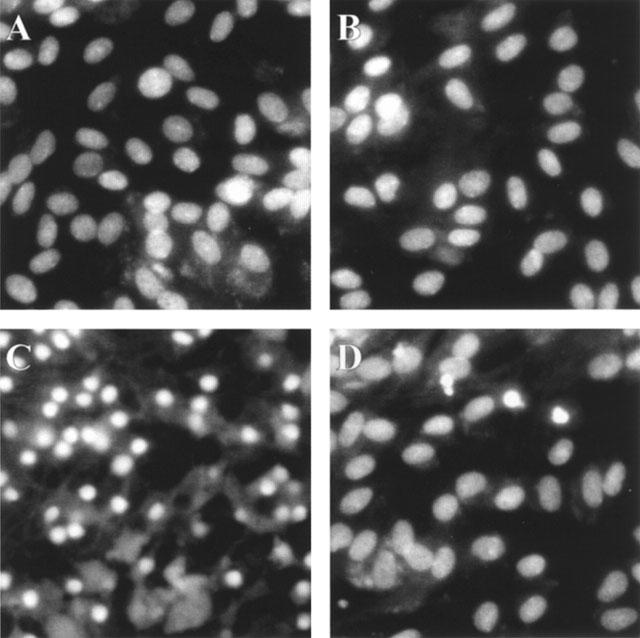

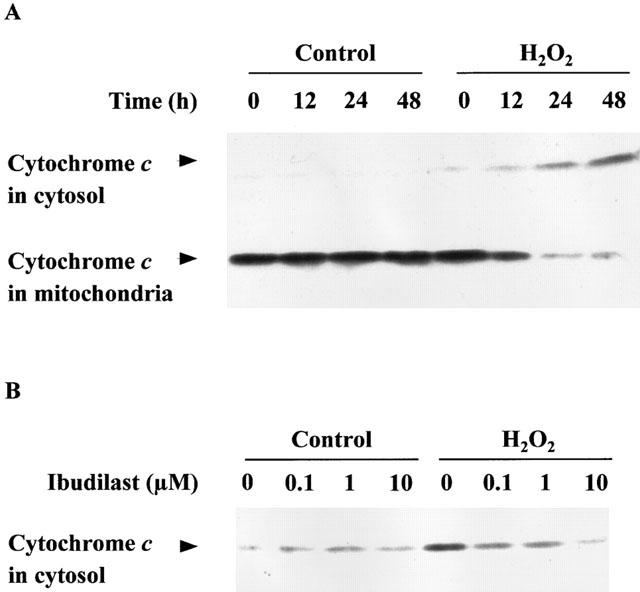

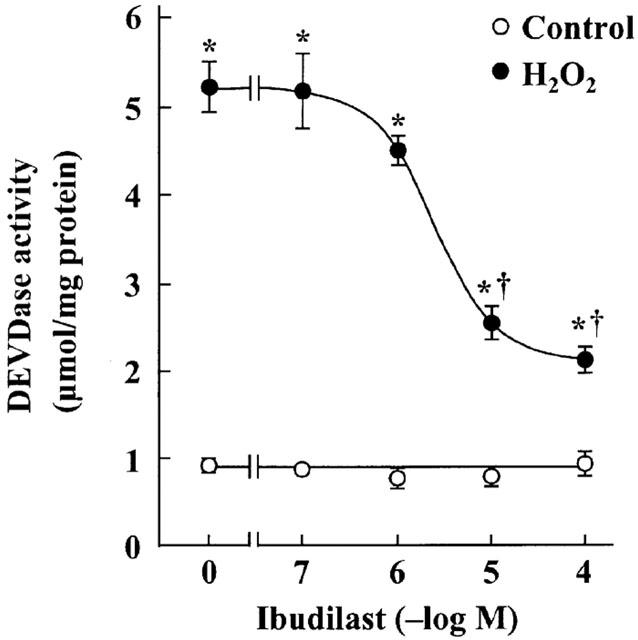

Incubation after exposure of astrocytes to H2O2-containing medium caused a significant decrease in MTT reduction activity, in agreement with the previous finding (Takuma et al., 1999). Ibudilast attenuated the H2O2-induced decreases in MTT reduction activity in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1). Furthermore, ibudilast inhibited the H2O2-induced formation of a DNA ladder (Figure 2), and nuclear condensation (Figure 3). These data are suggestive of ibudilast attenuating apoptotic injury. Reperfusion after exposure of astrocytes to H2O2 caused an increase in cytochrome c in the cytosol fraction and a decrease in the protein in the mitochondrial fraction (Figure 4A). Ibudilast inhibited the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria in a dose-dependent way (Figure 4B). Figure 5 shows that ibudilast also inhibited the H2O2-induced increase in caspase-3 like activity in a dose-dependent way.

Figure 1.

Effect of ibudilast on H2O2 exposure/reperfusion-induced cell injury in cultured rat astrocytes. Cells were exposed to normal (open circles) or 100 μM H2O2 (closed circles) for 30 min, and then incubated with Earle's solution for 23.5 h. The indicated concentrations of ibudilast were added 30 min before H2O2 exposure and were present until assay. Results are means±s.e. for 10 wells and were obtained from five separate experiments. *P<0.01, significantly different from control (Student-Newman-Keuls test); †P<0.01, significantly different from the values without ibudilast (Dunnett's t-test).

Figure 2.

Effect of ibudilast on DNA ladder formation induced by H2O2 exposure/reperfusion in cultured rat astrocytes. Cells were exposed to normal (control) or 100 μM H2O2 for 30 min, and then incubated with Earle's solution for 5 days. Ibudilast was added 30 min before H2O2 exposure and was present until assay. A typical result of two independent experiments is shown (M: 100 bp marker).

Figure 3.

Effect of ibudilast on nuclear condensation induced by H2O2 exposure/reperfusion in cultured rat astrocytes. Cells were preincubated in the absence (A, B) and presence (C, D) of 100 μM H2O2 for 30 min, and incubated with Earle's solution for 3 days. Ibudilast (10 μM) was added 30 min before H2O2 exposure and was present until assay (B, D). The cells were fixed and stained with 6.15 μg ml−1 Hoechst 33342.

Figure 4.

Effect of ibudilast on cytochrome c release from mitochondria induced by H2O2 exposure/reperfusion in cultured rat astrocytes. (A) Time course of translocation of cytochrome c from the mitochondrial to cytosol fractions. Cells were exposed to normal (control) or 100 μM H2O2 for 30 min, and then incubated with Earle's solution for the indicated time. (B) Dose-response for the effect of ibudilast. Cells were exposed to normal (control) or 100 μM H2O2 for 30 min, and then incubated with Earle's solution for 23.5 h. Ibudilast was added 30 min before H2O2 exposure and was present until assay. Cytochrome c in the cytosol fraction is shown. The typical results of three independent experiments are shown.

Figure 5.

Effect of ibudilast on the reperfusion-induced increase in DEVDase activity in cultured rat astrocytes. Cells were exposed to normal (control) or 100 μM H2O2 for 30 min, and then incubated with Earle's solution for 23.5 h. Ibudilast was added 30 min before H2O2 exposure and was present until assay. Results are means±s.e.mean for 10 wells and were obtained from two separate experiments. *P<0.01, significantly different from control (Student-Newman-Keuls test); †P<0.01, significantly different from the values without ibudilast (Dunnett's t-test).

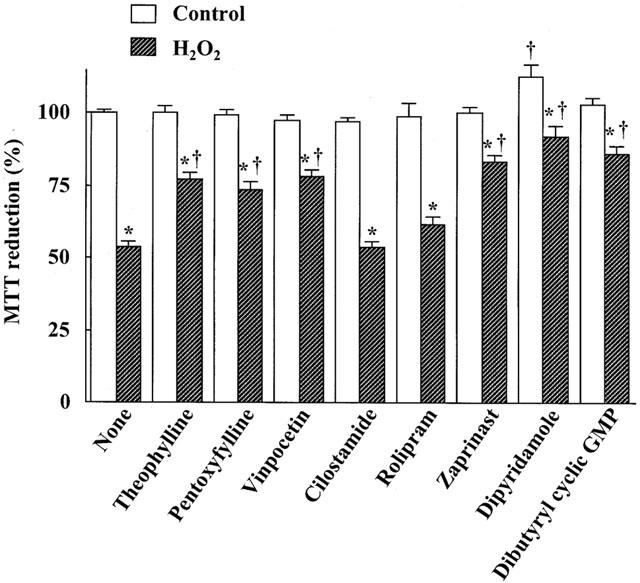

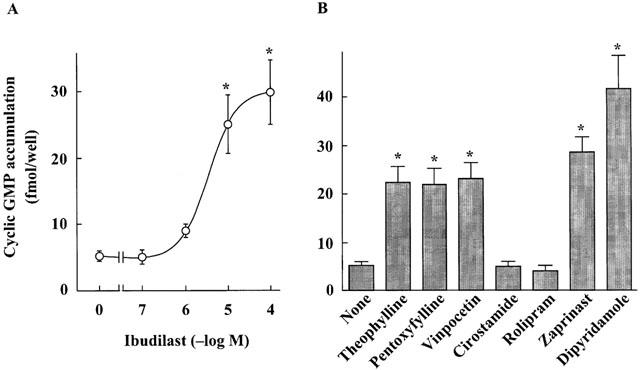

The effects of PDE inhibitors and dibutyryl cyclic GMP on the H2O2-induced injury in astrocytes are shown in Figure 6. The nonselective PDE inhibitors theophylline and pentoxyfylline, the cyclic GMP PDE inhibitors vinpocetine, dipyridamole and zaprinast and the cyclic GMP analogue dibutyryl cyclic GMP had the similar protective effect on the H2O2-induced injury. In contrast, the cyclic AMP PDE inhibitors cilostamide and rolipram had no effect on the cell injury. Ibudilast increased intracellular the cyclic GMP level in astrocytes in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 7A). The PDE inhibitors that protected astrocytes against the H2O2-induced injury also increased intracellular cyclic GMP level (Figure 7B). The leukotriene D4 antagonist LY 171883 and the ERK inhibitor PD98059 did not affect the protection provided by ibudilast against the H2O2-induced injury (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Effects of PDE inhibitors and dibutyryl cyclic GMP on H2O2 exposure/reperfusion-induced injury in cultured rat astrocytes. Cells were exposed to normal (open columns) or 100 μM H2O2 (hatched columns) for 30 min, and then incubated with Earle's solution for 23.5 h. Theophylline (30 μM), pentoxyfylline (100 μM), vinpocetine (50 μM), cilostamide (100 nM), rolipram (100 μM), zaprinast (10 μM), dipyridamole (10 μM), and dibutyryl cyclic GMP (100 μM) were added 30 min before H2O2 exposure and were present until assay. Results are means±s.e.mean for 9 – 19 wells and were obtained from 3 – 5 separate experiments. *P<0.01, significantly different from control (Student-Newman-Keuls test); †P<0.01, significantly different from the values without ibudilast (Dunnett's t-test).

Figure 7.

Effects of ibudilast (A) and PDE inhibitors (B) on the cyclic GMP level in cultured rat astrocytes. Cells were treated for 30 min with the indicated concentrations of ibudilast, theophylline (30 μM), pentoxyfylline (100 μM), vinpocetine (50 μM), cilostamide (100 nM), rolipram (100 μM), zaprinast (10 μM), and dipyridamole (10 μM). Results are means±s.e.mean for eight wells, and were obtained from two separate experiments. *P<0.01, significantly different from the values without drug (Dunnett's t-test).

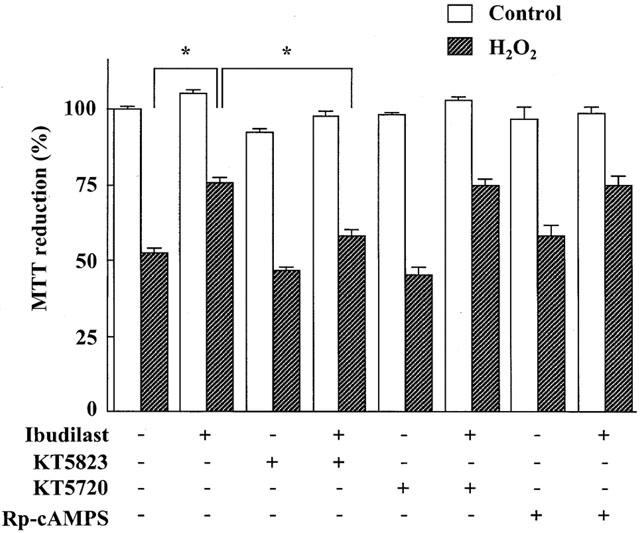

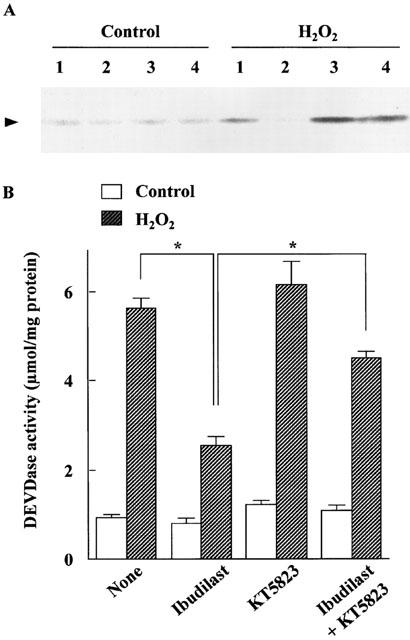

The effects of the cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase (PK) inhibitor KT5823, the cyclic AMP-dependent PK inhibitor KT5720 and the cyclic AMP antagonist Rp-cyclic AMPS on the protection provided by ibudilast against cell injury induced by reperfusion after exposure to H2O2 are shown in Figure 8. KT5823 (2 μM) attenuated the protective effect of ibudilast on the decrease in MTT reduction activity, but KT5720 and Rp-cyclic AMPS did not. KT5823 also attenuated the effect of ibudilast on the H2O2-induced cytochrome c release (Figure 9A) and caspase-3-like protease activation (Figure 9B).

Figure 8.

Effects of KT5823, KT5720 and Rp-cyclic AMPS on the protection provided by ibudilast against H2O2 exposure/reperfusion-induced injury in cultured rat astrocytes. Cells were exposed to normal (open columns) or 100 μM H2O2 (hatched columns) for 30 min, and then incubated with Earle's solution for 23.5 h. Ibudilast (10 μM) was added 30 min before H2O2 exposure and present until assay. KT5823 (2 μM), KT5720 (2 μM) and Rp-cyclic AMPS (100 μM) were added 60 min before H2O2 exposure and were present until assay. Results are means±s.e.mean for 10 – 32 wells, and were obtained from 5 – 16 separate experiments. *P<0.05, significant from the values of ibudilast alone (Tukey-HSD test).

Figure 9.

Effect of KT5823 on the inhibition by ibudilast of the reperfusion-induced cytochrome c release (A) and DEVDase activation (B) in cultured rat astrocytes. Open and hatched columns are control cells and H2O2 exposed cells, respectively. Cells were exposed to normal or 100 μM H2O2-containing medium for 30 min, and then incubated with Earle's solution for 23.5 h. Ibudilast (10 μM) and KT5823 (2 μM) were added 30 and 60 min before H2O2 exposure, respectively, and present until assay. (A) Cytochrome c in the cytosol fraction is shown. The lanes 1, 2, 3 and 4 are none, ibudilast, KT5823 and KT5823 plus ibudilast, respectively. A typical result of two independent experiments is shown. (B) Caspase-3-like protease activity. Results are means±s.e.mean for 10 – 20 wells obtained from 2 – 4 separate experiments. *P<0.05, significant from the values of ibudilast alone (Tukey-HSD test).

Discussion

Ibudilast has a beneficial effect on ischaemia/reperfusion-induced brain dysfunction (Ohashi et al., 1986a, 1986b; Yanase et al., 1996). In addition, previous in vitro studies show that ibudilast has a protective effect against exitotoxicity in cultured oligodendorocytes (Yoshioka et al., 1998; 2000), neurons (Tominaga et al., 1996) and hippocampal slices (Yanase et al., 1996). However, there is little information on the effect of ibudilast on astrocytic injury. We report here that ibudilast protects cultured astrocytes against cell injury induced by reperfusion after exposure to H2O2. This injury caused apoptosis as determined by formation of a DNA ladder and nuclear condensation, and ibudilast inhibited these apoptotic changes. This is the first evidence that ibudilast has an anti-apoptotic effect. We further observed that ibudilast inhibited apoptosis-related biochemical processes such as cytocrome c release from mitochondria and caspase-3 activation. These observations suggest that the anti-apoptotic effect of ibudilast is partly due to protection of the mitochondria against the H2O2-induced damage, although the exact mechanism is not known.

Iibudilast has an anti-leukotriene activity (Etoh et al., 1990). However, the leukotriene D4 receptor antagonist LY171883 did not affect the H2O2-induced cell injury. Alternatively, previous studies show that ibudilast is an inhibitor of PDE, and suggest that the effect of ibudilast is mediated partly by cyclic AMP (Souness et al., 1994; Niwa et al., 1995; Suzumura et al., 1999; Yoshioka et al., 2000). We examined the effects of several PDE inhibitors to clarify the possible involvement of cyclic AMP signalling pathway in the protective effect of ibudilast on the H2O2-induced astrocytic injury. Unexpectedly, we found that only the inhibitors that elevated the cyclic GMP level protected astrocytes against the H2O2-induced injury. That is, the cyclic GMP PDE inhibitors vinpocetine, dipyridamole and zaprinast, and the nonselective PDE inhibitors theophylline and pentoxyfylline had a protective effect on the astrocytic injury, while the cyclic AMP PDE inhibitors cilostamide and rolipram did not. We also observed that dibutyryl cyclic GMP protected astrocytes against the H2O2-induced injury and ibudilast increased the cyclic GMP level in astrocytes. These observations, together with the evidence that astrocytes possess cyclic GMP PDE (Agullo & Garcia, 1997), suggest that the protective effect of ibudilast on the astrocytic injury is mediated via a cyclic GMP, but not cyclic AMP, signalling pathway. The involvement of cyclic GMP in the effect of ibudilast is also reported in isolated human platelets: ibudilast inhibits cyclic GMP hydrolysis more potently than cyclic AMP hydrolysis (Kishi et al., 2000).

The present study further showed that the cyclic GMP-dependent PK inhibitor KT5823, but not the cyclic AMP-dependent PK inhibitor KT5720, blocked the effect of ibudilast on the H2O2-induced astrocytic injury including apoptosis. KT5823 also blocked the protective effect of dipyridamole on the astrocytic injury. These findings suggest that the effects of ibudilast and dipyridamole are mediated via a cyclic GMP-dependent, but not cyclic AMP-dependent, PK. The importance of cyclic GMP-dependent PK as an anti-apoptotic signal is also shown in PC12 cells (Kim et al., 1999). On the other hand, cyclic AMP activates not only cyclic AMP-dependent PK, but also MAP/ERK kinase in PC12 cells (Barrie et al., 1997). However, the MAP/ERK inhibitor PD98059 did not affect the protective effect of ibudilast. Furthermore, the cyclic AMP antagonist Rp-cyclic AMPS did not affect the protective effect of ibudilast. These findings suggest that a cyclic AMP signal pathway may not be involved in the effect of ibudilast on the H2O2-induced astrocytic injury.

Although cyclic GMP had a protective effect on astrocytic injury in a reperfusion model using H2O2 exposure, we previously observed that 8-bromo cyclic GMP exacerbated astrocytic injury in a reperfusion model using Ca2+ depletion (Matsuda et al., 1996). The effect of cyclic GMP analogue on the Ca2+ paradox injury may be explained by further increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in the reverse mode, since cyclic GMP stimulates the exchanger (Asano et al., 1995). Nevertheless, we have found in a preliminary experiment that ibudilast had a protective effect on the Ca2+ paradox injury, as the case of H2O2 exposure/reperfusion-induced injury reported here. This suggests that a cyclic GMP-independent mechanism may be involved in the effect of ibudilast on the Ca2+ paradox injury. It should be noted that such a mechanism is unlikely to involve inhibition of toxic factors tumour necrosis factor-α or nitric oxide, since the protective concentrations in the present study are 10 times less than those found to suppress production of these factors (Suzumura et al., 1999)

In conclusion, we demonstrate that ibudilast has an anti-apoptotic effect in an in vitro reperfusion model using H2O2 exposure, and suggest that the effect is mediated via a cyclic GMP/cyclic GMP-dependent PK pathway, although the exact site in the pathway is not known.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, The Science Research Fund of The Japan Private School Promotional Foundation, Uehara Memorial Foundation, Hyogo Science and Technology Association, Joint Research (B) of Kobe Gakuin University, and Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Abbreviations

- Ac-DEVD-MCA

acetyl-L-aspartyl-L-glutamiyl-L-valyl-L-aspartic acid α-(4-methyl-coumaryl-7-amide)

- cyclic GMP

guanosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis (β-amino ethyl ether) tetraacetic acid

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- MAP

mitogen-activated protein

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

- PK

protein kinase

References

- AGULLO L., GARCIA A. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase activity in granule neurons and astrocytes from rat cerebellum. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;26:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARAYA R., UEHARA T., NOMURA Y. Hypoxia induces apoptosis in human neuroblastoma SK-N-MC cells by caspase activation accompanying cytochrome c release from mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1998;439:168–172. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARMSTRONG R.C., AJA T.J., HOANG K.D., GAUR S., BAI X., ALNEMRI E.S., LITWACK G., KARANEWSKY D.S., FRITZ L.C., TOMASELLI K.J. Activation of the CED3/ICE-related protease CPP32 in cerebellar granule neurons undergoing apoptosis but not necrosis. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:553–562. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00553.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASANO S., MATSUDA T., TAKUMA K., KIM H.S., SATO T., NISHIKAWA T., BABA A. Nitroprusside and cyclic GMP stimulate Na+-Ca2+ exchange activity in neuronal preparations and cultured rat astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 1995;64:2437–2441. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64062437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRIE A.P., CLOHESSY A.M., BUENSUCESO C.S., ROGERS M.V., ALLEN J.M. Pituitary adenylyl cyclase-activated peptide stimulates extracellular signal-regulating kinase 1 or 2 (ERK1/2) activity in a Ras-independent, mitogen activated protein kinase/ERK kinase 1 or 2-dependent manner in PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:19666–19671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.19666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUDIHARDIO I., OLIVER H., LUTTER M., LUO X., WANG X. Biochemical pathways of caspase activation during apoptosis. Annu. Rev. Cell. Deev. Biol. 1999;15:269–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ETOH S., OHASHI M., BABA A., IWATA H. Inhibition by ibudilast of leukotriene D4-induced formation of inositol phosphates in guinea-pig lung. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990;100:564–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb15847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUKUYAMA H., KIMURA J., YAMAGUCHI S., YAMAUCHI H., OGAWA M., DOI T., YONEKURA Y., KONISHI J. Pharmacological effects of ibudilast on cerebral circulation: a PET study. Neurol. Res. 1993;15:169–173. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1993.11740130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALLO V., GHIANI C.A. Glutamate receptors in glia: new cells, new inputs and new functions. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2000;21:252–258. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JU C., YOON K.N., OH Y.K., KIM H.C., SHIN C.Y., RYU J.R., KO K.H., KIM W.K. Synergistic depletion of astrocytic glutathione by glucose deprivation and peroxynitrite: correlation with mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent cell death. J. Neurochm. 2000;74:1989–1998. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWASAKI A., HOSHINO K., OSAKI R., MIZUSHIMA Y., YANO S. Effect of ibudilast: a novel antiasthmatic agent, on airway hypersensitivity in bronchial asthma. J. Asthma. 1992;29:245–252. doi: 10.3109/02770909209048938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM Y.M., CHUNG H.T., KIM S.S., HAN J.A., YOO Y.M., KIM K.M., LEE G.H., YUN H.Y., GREEN A., LI J., SIMMONS R.L., BILLIAR T.R. Nitric oxide protects PC12 cells from serum deprivation-induced apoptosis by cGMP-dependent inhibition of caspase signaling. J. Neurosci. 1999;15:6740–6747. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-06740.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KISHI Y., OHTA S., KASUYA N., TATSUMI M., SAWADA M., SAKITA S., ASHIKAGA T., NUMANO F. Ibudilast modulates platelet-endothelium interaction mainly through cyclic GMP-dependent mechanism. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2000;36:65–70. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRISTIAN T., KATSURA K., GIDO G., SIESJO B.K. The influence of pH on cellular calcium influx during ischemia. Brain Res. 1994;641:295–302. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU X.Z., XU X.M., HU R., DU C., ZHANG S.X., MCDONALD J.W., DONG H.X., WU Y.J., FAN G.S., JACQUIN M.F., HSU C.Y., CHOI D.W. Neuronal and glial apoptosis after traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:5395–5406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05395.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUDA T., TAKUMA K., ASANO S., KISHIDA Y., NAKAMURA H., MORI K., MAEDA S., BABA A. Involvement of calcineurin in Ca2+ paradox-like injury of cultured rat astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:2004–2011. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70052004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUDA T., TAKUMA K., BABA A. Na+-Ca2+ exchanger: physiology and pharmacology. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1997;74:1–20. doi: 10.1254/jjp.74.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUDA T., TAKUMA K., NISHIGUCHI E., HASHIMOTO H., AZUMA J., BABA A. Involvement of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in reperfusion-induced delayed cell death of cultured rat astrocytes. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1996;8:951–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCARTHY K.D., SALM A.K. Pharmacologically-distinct subsets of astroglia can be identified by their calcium response to neuroligands. Neuroscience. 1991;41:325–333. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90330-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURPHY S., PEARCE B. Functional receptors for neurotransmitters on astroglial cells. Neuroscience. 1987;22:381–394. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIWA M., KOHNO K., AL-ESSA L.Y., KOBAYASHI M., NOZAKI M., TSURUMI K. Ibudilast, an anti-allergic and cerebral vasodilator, modulates superoxide production in human neutrophils. Life Sci. 1995;56:107–115. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00420-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHASHI M., KITO J., NISHINO K. Mode of cerebral vasodilating action of KC-404 in isolated canine basilar artery. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 1986a;280:216–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHASHI M., KUDO Y., ICHIKAWA Y., NISHINO K. Anti-thrombotic effect of KC-404, a novel cerebral vasodilator. Gen. Pharmacol. 1986b;17:385–389. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(86)90179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PANTONI L., GARCIA J.H., GUTIERREZ J.A. Cerebral white matter is highly vulnerable to ischemia. Stroke. 1996;27:1641–1746. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.9.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETITO C.K., OLARTE J.P., ROBERTS B., NOWAK T.S. &, JR, PULSINELLI W.A. Selective glial vulnerability following transient global ischemia in rat brain. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1998;57:231–238. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199803000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIEMKOWICZ E., HANSEN A.J. Brain extracellular ion composition and EEG activity following 10 minutes ischemia in normo- and hyperglycemic rats. Stroke. 1981;12:236–240. doi: 10.1161/01.str.12.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SILVER I.A., ERECINSKA M. Ion homeostasis in rat brain in vivo: intra- and extracellular Ca2+ and H+ in the hippocampus during recovery from short-term, transient ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:759–772. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOUNESS J.E., VILLAMIL M.E., SCOTT L.C., TOMKINSON A., GIEMBYCZ M.A., RAEBURN D. Possible role of cyclic AMP phosphodiesterases in the actions of ibudilast on eosinophil thromboxane generation and airways smooth muscle tone. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;111:1081–1088. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb14855.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUZUMURA A., ITO A., YOSHIKAWA M., SAWADA M. Ibudilast suppresses TNFα production by glial cells functioning mainly as type III phosphodiesterase inhibitor in the CNS. Brain Res. 1999;837:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKUMA K., FUJITA T., KIMURA Y., TANABE M., YAMAMURO A., LEE E., MORI K., KOYAMA Y., BABA A., MATSUDA T. T-588 inhibits astrocyte apoptosis via mitogen-activated protein kinase signal pathway. Eur. J. Parmacol. 2000a;399:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKUMA K., LEE E., KIDAWARA M., MORI K., KIMURA Y., BABA A., MATSUDA T. Apoptosis in Ca2+ reperfusion injury of cultured astrocytes: roles of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB activation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:4204–4212. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKUMA K., MATSUDA T., ASANO S., BABA A. Intracellular ascorbic acid inhibits the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in cultured rat astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 1995;64:1536–1540. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64041536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKUMA K., MATSUDA T., HASHIMOTO H., ASANO S., BABA A. Cultured rat astrocytes possess Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. Glia. 1994;12:336–342. doi: 10.1002/glia.440120410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKUMA K., MATSUDA T., HASHIMOTO H., KITANAKA J., ASANO S., KISHIDA Y., BABA A. Role of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in agonist-induced Ca2+ signaling in cultured rat astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 1996a;67:1840–1845. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67051840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKUMA K., MATSUDA T., KISHIDA Y., ASANO S., SEONG Y.H., BABA A. Heat shock protects cultured rat astrocytes in a model of reperfusion injury. Brain Res. 1996b;735:265–270. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKUMA K., YOSHIDA T., LEE E., MORI K., KISHI T., BABA A., MATSUDA T. CV-2619 protects cultured astrocytes against reperfusion injury via nerve growth factor production. Eur. J. Parmacol. 2000b;406:333–339. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00701-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMINAGA Y., NAKAMURA Y., TSUJI K., SHIBATA T., KATAOKA K. Ibudilast protects against neuronal damage induced by glutamate in cultured hippocampal neurons. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1996;23:519–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb02772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANASE H., MITANI A., KATAOKA K. Ibudilast reduces intracellular calcium elevation induced by in vitro ischaemia in gerbil hippocampal slices. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1996;23:317–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb02830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOSHIOKA A., SHIMIZU Y., HIROSE G., KITASATO H., PLEASURE D. Cyclic AMP-elevating agents prevent oligodendroglial excitotoxicity. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:2416–2423. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70062416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOSHIOKA A., YAMAYA Y., SAIKI S., KANEMOTO M., HIROSE G., PLEASURE D. Cyclic GMP/cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase system prevents excitotoxicity in an immortalized oligodendroglial cell line. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:633–640. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.740633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]