Imidazolin binding sites

Many publications have shown that imidazoline derivatives such as clonidine, moxonidine or rilmenidine reduce sympathetic tone via a central mechanism and that as a result they reduce plasma catecholamines and blood pressure (Reid et al., 1995). This reduction in blood pressure appears not to be regulated via peripheral, presynaptically localized receptors, since neither catecholamine depletion by reserpine, or destruction of the nerve endings with 6-hydroxydopamine produces a notable weakening of the clonidine-induced blood pressure reduction (Haeusler, 1974a,1974b; Kobinger & Pichler, 1976; Finch et al., 1975). In contrast, selective α2-adrenoceptor antagonists such as rauwolscine dose-dependently block hypotension induced by intravertebral application of clonidine. While some classical α2-adrenoceptor antagonists such as SKF86466 (in contrast to the imidazoline derivatives efaroxan and idazoxan) did not inhibit the clonidine-induced hypotension in the CNS (Ernsberger et al., 1988b; 1994; Haxhiu et al., 1994), this was discussed to due to underdosage of the antagonist (Bock et al., 1999). Hence the effects of clonidine are due to a central α2-adrenoceptor-mediated mechanism. The first signs that imidazoline derivatives might also work via non-adrenergic binding sites stem from Ruffolo (1977); the imadazoline derivative tetrahydrozoline was able to antagonize oxymetazoline-induced contraction, but not the contractile response induced by phenylethylamine derivatives such as noradrenaline, methoxamine or phenylephrine. Clear indications for a novel receptor type came from Bousquet et al. (1984), who reported hypotension after microinjection of clonidine into the rostroventrolateral medulla (RVLM). α-methylnoradrenaline showed no blood pressure reducing effect in the same model. The authors therefore assumed that binding sites must be present in the RVLM which preferentially bind imidazolines. Radioligand binding studies on RVLM membranes showed selective binding sites for imidazolines (Ernsberger et al., 1987). These data confirmed the assumptions of Ernsberger et al. (1988a; 1992); Buccafusco et al. (1995) and Bousquet et al. (1984) that the C1 region of the RVLM appeared to be the decisive area involved (Reis et al., 1989).

Since then, two different imidazoline binding site subtypes have been identified (Michel & Insel, 1989; Michel & Ernsberger, 1992; Ernsberger et al., 1992). The I1-binding site, which shows a high affinity binding to [3H]-clonidine, is localized in the frontal cortex and the ventrolateral medulla (Bricca et al., 1989; Ernsberger et al., 1990a; 1992; Gomez et al., 1991), an area associated with central blood pressure regulation. Functionally, the I1-binding site seems to be involved in central blood pressure regulation (Ernsberger et al., 1988b; 1994; Haxhiu et al., 1994; Hamilton, 1992a,1992b; Hamilton et al., 1992; Hieble & Ruffolo, 1992), even though its importance remains largely unclarified, since in functional α2A-adrenoceptor 'knock out‘ mice (D79N; Macmillan et al., 1996) no evidence of I1-imidazoline binding site-mediated effects was revealed (Zhu et al., 1999). Its amino acid sequence and the DNA coding for it also remain to be determined, although an imidazoline binding site antisera cDNA has been isolated and characterized as encoding a 1504 amino acid protein (IRAS-1) showing properties of an I1-binding site (Piletz et al., 2000). I1-binding sites have also been demonstrated in the spinal cord, kidney and pancreas (Regunathan et al., 1993; Ernsberger et al., 1995; Schulz & Hasselblatt, 1989a), but not in the left ventricle (Raasch et al., 2000).

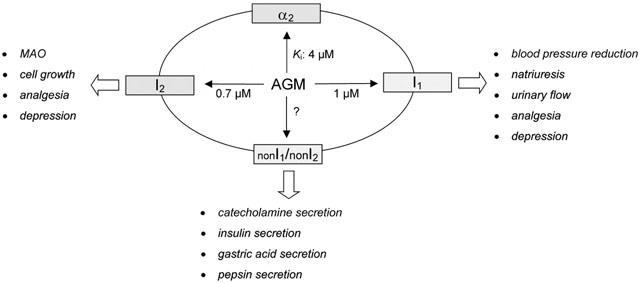

Unlike the I1-binding site, the role of the I2-binding sites has been better characterized, whereby I2-binding sites can be further differentiated amongst I2A- and I2B-binding sites depending on their amiloride sensitivity. I2 binding sites have been demonstrated in various tissues such as brain (Brown et al., 1990), liver (Tesson & Parini, 1991) and kidney (Michel et al., 1989), whereby studies by Tesson et al. (1991) concluded that they are associated with mitochondria. Further studies focused their localization to the outer mitochondrial membrane. Functionally, the I2-binding site has been characterized as a regulatory subunit of monoamine oxidase (MAO, Figure 1), and later on it became clear that both MAO A and B share the same I2-binding site as a novel domain on the protein (Limon et al., 1992; Olmos et al., 1993). Moreover, studies on MAO A- and MAO B-deficient mice indicate that (1) the I2 binding sites identified by [3H]-idazoxan reside solely on MAO B, and (2) the binding sites on MAO A and a 28-kDa protein identified in livers of MAO A- and MAO B-deficient mice by photolabelling with 2-[3-azido-4-[(125)l]iodophenoxyl]methylimidazoline ([125I]-AZIPI) may represent additional subtypes of the imidazoline-binding site family (Remaury et al., 2000). In vitro studies have shown that selective ligands of the I2-binding site reduce MAO activity (Carpene et al., 1995; Tesson et al., 1995; Raasch et al., 1996; 1999). Further on, no correlation with a reduced oxygen utilization could be shown in vitro (Raasch et al., 1999). After protein molecular studies showed that I2-binding sites could be found on various MAO isoenzymes with varying molecular weights (Escriba et al., 1996), and that a binding domain (Escriba et al., 1999) for imadazoline derivatives could be identified in the MAO-B (Raddatz & Lanier, 1997; Raddatz et al., 1997; 1999; 2000), the functional role of the I2-binding site, unlike the I1-binding site, could be considered as established. Chronic treatment of rats with specific I2-ligands reduces MAO activity in various organs and catecholamines increase as a consequence (Raasch et al., 1999). In pathophysiological states such as heroin dependency or neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease or Huntington's chorea, the I2-binding site density is reduced (Garcia-Sevilla et al., 1999), which indicates that I2-binding sites might also be of clinical significance. In addition to this correlation to MAO, the I2-binding site has also been suggested to be involved in cell growth (Regunathan et al., 1996a) or analgesic effects (Olmos et al., 1994; Sastre et al., 1996a). However, both are isolated findings and require confirmation with more detailed investigations. In this view, the 28-kDa protein identified in livers of MAO A- and MAO B-deficient mice (Olmos et al., 1994; Remaury et al., 2000) may be of some importance (see Figure 1; for detailed information see corresponding section of this review).

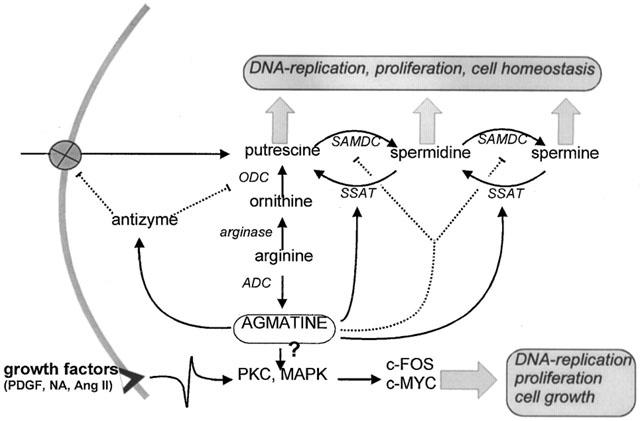

Figure 1.

Imidazoline binding sites and their suggested functions. Agmatine binds with a moderate affinity (Ki values are taken from Li et al.) to α2-adrenoceptors as well as to I1 and I2 binding sites. Some authors (Chan, 1998; Molderings et al., 1998a; 1999a) attributed functions to binding sites (nonl1/non I2-binding sites) the affinity profile of which is consistent with neither the I1- nor the I2-binding sites.

Furthermore, some authors have attributed specific functions such as noradrenaline release (Fuder & Schwarz, 1993; Molderings & Göthert, 1995; Likungu et al., 1996; Molderings et al., 1999b), secretion of gastric acid and pepsin (Molderings et al., 1998a; 1999a) and insulin from β-cells (Chan, 1998) to binding sites for which the affinity profile is not consistent with those of I1- or I2-binding sites (nonI1/non I2-binding sites see Figure 1).

Clonidine displacing substance

Apart from a specific, saturable, high affinity and reversible binding, the corresponding anatomical, histological and subcellular distribution of the putative binding sites as well as the identification of a physiological function, the establishment of the protein sequence, DNA structure, signal transduction and the identification of endogenous ligands are decisive criteria for the establishment of a new receptor system (Ernsberger, 1999).

Isolation, chemical characterization and receptor specificity of CDS

On the basis of the fact that the phenylethyl derivative noradrenaline and the imadazoline derivative clonidine influence blood pressure via central α2-adrenoceptors and/or imidazoline binding site-mediated mechanisms, it had to be asked whether other non-catecholaminergic and until now unidentified substances participate in the regulation of blood pressure and heart rate. Atlas (Atlas & Burstein, 1984a,1984b; Atlas et al., 1987) isolated a substance from rat and calf brain by ion exchange chromatography, electrophoresis and HPLC. This isolate bound specifically to α2-adrenoceptors and displaced clonidine, but not the α1-ligand prazosin or the β-ligand cyanopindolol. Because of this property, the substance was named ‘Clonidine Displacing Substance' (CDS). Occasionally, this CDS is referred to as 'classical CDS‘ (cCDS) to emphasize its detection by radioligand binding studies. Even though Atlas (Atlas & Burstein, 1984a,1984b; Atlas et al., 1987) did not clarify its structure, CDS was characterized as a hydrophobic substance with a molecular weight of 587 Da1 stable to heat, acid hydrolysis and proteolytic enzymes such as trypsin, chymotrypsin, pronase, papain and pyroglutamase. Moreover it was postulated that CDS was not an amino acid and that it possessed no amino groups as shown by a negative ninhydrin and fluorecamine reaction. Due to its electrophoretic properties it was claimed that CDS was positively charged. Wavelengths of 224 and 276 nm represented its absorption maxima, which suggested the presence of aromatic residues in the molecule (see also Table 1; Atlas & Burstein, 1984a,1984b; Meeley et al., 1988a,1988b). Meeley et al. (1988a,1988b) developed a specific antibody directed against the clonidine analogue p-aminoclonidine. Since this antibody revealed a cross-reactivity with CDS, the authors concluded that there were structural similarities between clonidine and CDS and claimed that a phenyl and imidazole ring were mandatory structural characteristics for CDS, which confirmed the findings of Atlas & Burstein (1984a,1984b) regarding the relative hydrophobic character and the positive charge at neutral pH. CDS determined by radioimmunoassays is referred to in some studies as 'immunoreactive CDS‘ (irCDS) in order to emphasize its mode of determination. Since the distribution of irCDS in various organs of rats is directly correlated with biological activity attributed to cCDS, both cCDS and irCDS have been suggested to be similar (Meeley et al., 1988a). For this reason we have not distinguished between cCDS and irCDS in later sections of this review; only the term CDS is used irrespective of the way in which it was determined.

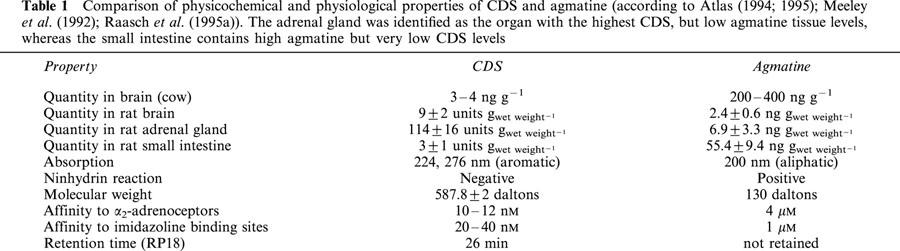

Table 1.

Comparison of physicochemical and physiological properties of CDS and agmatine (according to Atlas (1994; 1995); Meeley et al. (1992); Raasch et al. (1995a)). The adrenal gland was identified as the organ with the highest CDS, but low agmatine tissue levels, whereas the small intestine contains high agmatine but very low CDS levels

Later on, CDS could be characterized by radioligand binding studies as being 30 fold selective for imidazoline binding sites compared to α2-adrenoceptors (Table 1), which strengthened the hypothesis that CDS might be an endogenous ligand for the imidazoline binding site (Ernsberger et al., 1988a; 1990b). Studies showing that CDS has only a weak affinity towards the inhibitory G-protein also fit in with this idea (Atlas, 1991). Unlike clonidine, CDS was incapable of influencing basal adenylate cyclase activity in human platelets or the noradrenaline-induced inhibition of adenylate cyclase at a concentration able to displace clonidine binding, findings which certainly do not support an α2-adrenoceptor-mediated mechanism of action for CDS.

Distribution of CDS in central and peripheral tissues

After CDS had initially been isolated from the brains of several species (Atlas & Burstein, 1984a,1984b; Meeley et al., 1986; Ernsberger et al., 1988a; Regunathan et al., 1991a), CDS was also shown in various peripheral tissues by a specific antiserum directed against CDS (see Table 1; Meeley et al., 1988b; 1992; Dontenwill et al., 1988; Hensley et al., 1989). The existence of peripheral CDS was confirmed by a specific bioassay, which is based on the ability of CDS to induce contraction of the vas deferens or gastric fundus (Diamant & Atlas, 1986; Felsen et al., 1987). CDS, which has been isolated from brain, gastric fundus, heart, small intestine, kidney, liver, skeletal muscle and serum, contracted the gastric funds in a manner completely or at least partially antagonizable by verapamil. CDS isolated from the adrenal glands, however, relaxed the gastric fundus. The different extent of antagonism as well as the relaxation by adrenal CDS was explained by the possible co-extraction of other, effect-masking substances. Finally, Synetos et al. (1991) isolated CDS from human plasma and showed its biological effectiveness through the contraction of rat aortal vascular rings. Because of the significantly reduced plasma concentrations of CDS in adrenalectomized rats compared to sham-operated animals, Meeley et al. (1992) suggested the adrenals as the possible source of CDS circulating in the blood.

Biological function of CDS

Cardiovascular effects of CDS

Since CDS and clonidine compete for a common binding site, it was questioned whether CDS would have agonistic or antagonistic activity in a functional test. After central application of CDS, arterial blood pressure increases significantly without any change in heart rate both in the cat and the rat (Bousquet et al., 1986; 1987), which in this way is opposite to the effects seen after central dosing of clonidine (see Table 2; Bousquet et al., 1984). Intracisternal application of CDS produces no change in blood pressure in anaesthetized rabbits (Bousquet et al., 1987). Furthermore, CDS can antagonize clonidine-stimulated hypotension directly, i.e. the blood pressure reduction is reduced (Bousquet et al., 1986) and the dose-response curve for clonidine is clearly shifted to the right by CDS. This finding completely contradicts the results of Meeley et al. (1986), who observed a clear drop in blood pressure and heart rate after injection of CDS into the C1-region of the rat RVLM. Combination experiments with clonidine were not performed in this study. The reasons underlying these discrepant results may lie in the various solvents used for isolating and purifying the CDS (Bousquet et al., 1987). Alternatively, effects from CDS-extract impurities such as aminoacids, CDS-fragments, catecholamines, histamine or potassium might also have lead to these inconsistencies (Reis et al., 1992; Szabo et al., 1995; Singh et al., 1995).

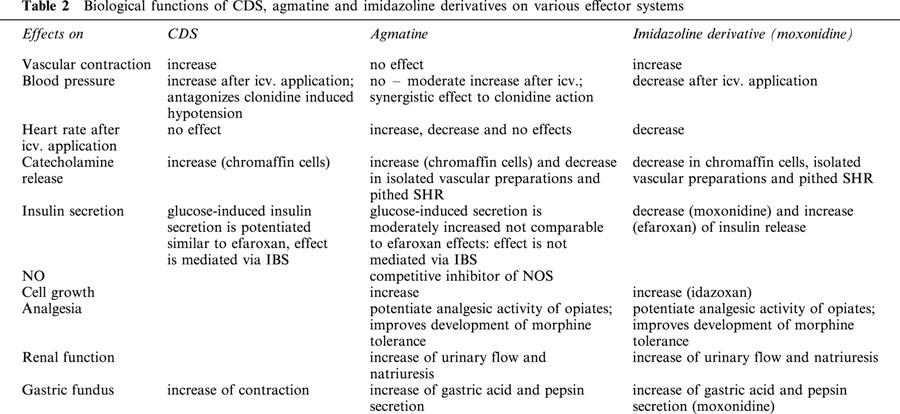

Table 2.

Biological functions of CDS, agmatine and imidazoline derivatives on various effector systems

CDS stimulates catecholamine release

Apart from the above described property of CDS to contract various organ preparations, CDS has also been identified as a catecholamine releasing substance (Table 2). CDS binds with a high affinity to membranes of bovine chromaffin cells, whereby the displacement of [3H]-idazoxan by CDS was not impeded by guanosine 5′-(β,γ-imido)triphosphate, indicating that the corresponding imidazoline binding site was not coupled to a GTP binding protein (Regunathan et al., 1991a). It should be noted that this was an I2 like site labelled by [3H]-idazoxan and that I2-binding sites are consistently unaffected by guanine nucleotides. The concentration-dependent adrenaline release from chromaffin cells in response to CDS was comparable to that in response to nicotine, while the CDS-stimulated noradrenaline release was only about a quarter of the noradrenaline release induced by nicotine. Unlike the nicotine response, the release of either catecholamine following CDS can not be blocked by hexamethonium, which suggests a nicotine receptor-independent mechanism (Regunathan et al., 1991a). Since the catecholamine release is also not inhibited by the specific α2-antagonist SKF-86466, which shows no affinity towards imidazoline binding sites (Ernsberger et al., 1990b), but is influenced by cobalt (Regunathan et al., 1991a), a specific imidazoline binding site-dependent and calcium-dependent release mechanism induced by CDS is suggested.

Insulinotropic effects of CDS

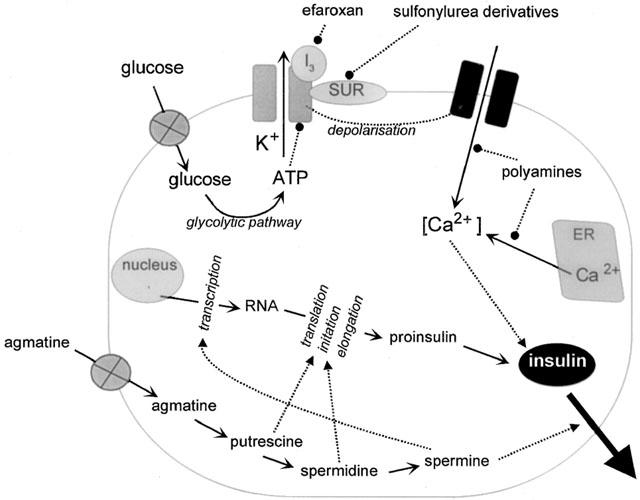

For the further functional characterization of CDS, its influence on glucose stimulated insulin release was investigated in isolated Langerhans cells (Table 2 and Figure 2). The existence of imidazoline binding sites was shown in the pancreas (Schulz & Hasselblatt, 1989a,1989b), but the imidazoline binding sites of the β-cells of the pancreas appear to differ from the known I1- and I2-binding sites (Figures 1 and 2; Brown et al., 1993a; Chan et al., 1994; 1995; Morgan et al., 1995), and are also not identical with the binding site for sulphonylurea derivatives (Brown et al., 1993b; Rustenbeck et al., 1997). For this reason Morgan et al. (1999) have speculated about the existence of a pancreas specific I3-binding site. Moreover, it could be shown that imadazoline derivatives such as efaroxan or phentolamine increase the release of insulin by influencing the K-ATP channel (Figure 2; Chan & Morgan, 1990; Dunne et al., 1995; Plant & Henquin, 1990). CDS isolated from rat brain potentiated the glucose (6 mM) induced secretory insulin response concentration-dependently to a similar extent as efaroxan, and reversed the inhibitory effects of diazoxide on glucose-stimulated insulin release just as other similar imadazoline derivatives do. That this CDS effect is possibly mediated via imidazoline binding sites can be concluded from the observation that imadazoline derivatives such as RX801080 and KU14R antagonize the insulin-releasing effect of CDS. In addition, the effects of CDS on insulin secretion were not altered by pretreatment of the CDS extract (protease incubation as well 3000 Da molecular filtration centrifugation; Chan et al., 1997), which confirms the structural properties of CDS postulated by Atlas & Burstein (1984a,1984b), i.e. that CDS is not a peptide, but rather a low molecular weight substance. In closing, efaroxan-pretreated islet cells appear to be desensitized to CDS concerning insulin release, which correlates with observations obtained for efaroxan itself (Chan, 1998).

Figure 2.

Current working hypothesis depicting mechanisms regulating insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells and proposed sites for interference by agmatine. ATP generated by glucose metabolism shuts down K+-channels, resulting in depolarization and subsequent influx of Ca2+ through voltage-activated Ca2+-channels. This influx of Ca2+ increases cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, which is accompanied by mobilization of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), an event triggering secretory granule translocation and exocytotic release of insulin. The respective binding of imidazolines (such as efaroxan) and sulphonylurea derivatives (such as glibenclamide) to I3-binding sites and the sulphonylurea receptor, also closes the K+-channels. Agmatine does not bind to I3-binding sites. However, agmatine may enhance insulin secretion via its metabolites, after it is taken up by specific transporters. Putrescine, spermidine are necessary for proinsulin biosynthesis, whereas spermine may exert a stimulatory or permissive role in RNA transcription and long-term insulin release. Polyamines are also probably involved in regulation of cytosolic Ca2+-concentration by blocking Ca2+-influx and its release from intracellular stores. Abbreviations: …▪quot; : stimulation; …•: inhibition.

Agmatine

Synthesis and metabolism of agmatine

Biosynthesis of agmatine

Li et al. (1994) succeeded in identifying and characterizing mammalian agmatine by ion and molecular weight exclusion chromatography, high pressure liquid chromatography and mass spectroscopy, as a candidate for CDS. Agmatine, the decarboxylation product of the amino acid arginine, was first identified in 1910 by Kossel in herring sperm and is known as an intermediate in the polyamine metabolism of various bacteria, fungi, parasites and marine fauna (Tabor & Tabor, 1984; Yamamoto et al., 1988; Ramakrishna & Adiga, 1975), where polyamines have been attributed an important function in cellular growth. Agmatine is chemically characterized as follows (Table 1): its molecular mass is 130 Da, the UV absorption maximum of 200 nm suggests an aliphatic structure and a ninhydrin positive reaction confirms the existence of an amino group. Radioligand binding studies on membranes of bovine cerebral cortex, the ventrolateral medulla and on chromaffin cells have revealed Kds towards α2-adrenoceptors, I1- and I2-binding sites of 4, 0.7 and 1 μM, respectively (Figures 1 and 3; Li et al., 1994a). It had low affinity for the α1- and β-adrenoceptors, 5−HT3 serotonin and D2 dopamine binding sites (Li et al., 1994a), or the κ opioid and adenosine A1-receptors (Szabo et al., 1995). An interaction with the sigma3 binding site has been shown on murine neuroblastoma cells (Molderings et al., 1996). As a functional correlate to CDS, agmatine concentration-dependently releases adrenaline and noradrenaline from chromaffin cells (Table 2). Since chromaffin cells express imidazoline binding sites, but not α2-adrenoceptors (Regunathan et al., 1993), this can be considered as an indication for an agonistic function of agmatine at these binding sites. However, since there is a lack of proof that agmatine-induced catecholamine release can be blocked by antagonists of the I1-binding site, it is not certain whether these binding sites mediate this effect. Moreover, data showing an inhibitory potency or no effect of agmatine on noradrenaline release (Häuser & Dominiak, 1995; Häuser et al., 1995; Molderings & Göthert, 1995; Molderings et al., 1997; 2000; Schäfer et al., 1999b) fuels doubts as to whether this catecholamine releasing effect is really mediated via a direct mechanism whereby imidazoline binding sites are involved. On the other hand, it was suggested that agmatine influences noradrenaline release via a dual interaction, namely a competitive antagonism and an allosteric activation of the rat α2D-adrenoceptor, since (1); noradrenaline, moxonidine- or clonidine-induced noradrenaline release in segments of rat vena cava was dose-dependently enhanced or inhibited by agmatine, and (2); binding of clonidine and rauwolscine was inhibited, the rate of association and dissociation of clonidine was altered, and [14C]-agmatine was inhibited from binding to its specific recognition site by agmatine (Molderings et al., 2000).

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of an agmatinergic synapse: L-arginine enters the nerve ending via a transporter and is decarboxylated by the mitochondrial arginine decarboxylase (ADC) to agmatine (AGM), which is stored in vesicles and metabolized to putrescine (PUT) by agmatinase (AGMase). Agmatine inhibits NO synthase (NOS) as well as monoamine oxidase (MAO) since it was demonstrated that I2-binding site (I2-BS) is a regulative binding site of MAO. After agmatine is released from the neuron it is subject for a specific uptake or it interacts with various pre- and postsynaptic receptors including the I1-binding site (I1-BS), α2 adrenoceptor (α2-R), NMDA, nicotinic cholineric (NIC), 5−HT3 (via the sigma-2 binding site) receptor. Furthermore, agmatine enters postsynaptic neurons via nicotinic and possibly NMDA ion channels. Whether such released agmatine represents a source for serum agmatine has not yet been determined. Peripheral effects of agmatine on blood pressure and cell growth are also a matter of debate. Released agmatine binds to presynaptic imidazoline binding sites and α2 adrenoceptors and in this way is involved in the regulation of catecholamines. Agmatine penetrates glial cells where it also modulates the expression and activity of iNOS.

Agmatine arises enzymatically from the activity of arginine decarboxylase (ADC) on arginine (Figures 3 and 4) and is not supplied from nutritional components or bacterial colonization. ADC isolated from rat brain differs from plant or bacteria-derived ADC concerning localization, since ADC is associated with the mitochondria rather than the cytoplasm (as is typical for bacteria). The second difference concerns its substrate specificity. In contrast to bacterial ADC, mammalian ADC uses ornithine in addition to arginine, whereby it is not a typical ornithine decarboxylase, since it is neither cytosolic nor inhibited by diflouromethylornithine, a universal and irreversible inhibitor of all isoforms of ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) (Hunter et al., 1991). Finally, the optimum temperature of mammalian ADC is 30°C. At the bacterial temperature optimum of 37°C the enzyme activity of the mammalian ADC is only one third as active as it is at 30°C. Only the pH optimum (8.25) is similar between mammalian and bacterial ADC (Li et al., 1994a; 1995; Regunathan & Reis, 2000). Inhibition experiments in macrophages with lipopolysaccharides (LPS), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and Interleukin-10 (IL-10) showed that ADC activity is subject to physiological control (Sastre et al., 1998). The co-localization of I2-binding sites and ADC on mitochondria has been discussed as a potential intracellular receptor-controlled regulatory loop for endogenous biosynthesis (Figure 3; Li et al., 1995). However, the organ specific distribution of ADC in rats (Regunathan & Reis, 2000) differs from that of agmatine (Raasch et al., 1995a), revealing some doubt that there is a close correlation between agmatine and its biosynthetic enzyme.

Figure 4.

Metabolism of L-arginine in the mammalian organism.

Organ-specific, cellular and subcellular distribution of agmatine

Using high pressure liquid chromatography, agmatine has been demonstrated in nearly all organs of the rat (Table 1), whereby the highest concentrations are found in the stomach (71 ng g−1 wet weight), followed by the aorta, small and large intestine, and spleen; it is found in lower concentrations (<10 ng g−1 wet weight) in the lungs, vas deferens, adrenals, kidneys, heart, liver, skeletal muscle, brain and testes (Raasch et al., 1995a,1995b). Gas chromatography studies by Stickle et al. (1996) confirmed an organ specific distribution of agmatine. This distribution pattern of agmatine in various organs (Raasch et al., 1995a) differs widely from that of CDS (Table 1; Meeley et al., 1992). As an example, high concentrations of CDS but only low concentrations of agmatine are found in the adrenal gland. Moreover, the low correlation (r=0.2193) between agmatine and CDS tissue levels in both studies indicates clearly that agmatine can not exclusively represent CDS, but that, if at all, it only represents a member of a whole CDS family.

The concentration of agmatine in rat plasma is only 0.45 ng ml−1 (Raasch et al., 1995a,1995b), which renders it doubtful that agmatine acts as a circulating hormone since the Kd values for the I1- (0.7 μM) and I2-binding sites (1 μM; (Li et al., 1994a) are approximately 200 – 300 fold higher compared to rat plasma concentrations. In addition, the source for circulating agmatine remains unidentified, since (1) ADC has not been detected in plasma until now, and (2) the adrenals, which were identified as sources for CDS (Meeley et al., 1992), contain only minimal amounts of agmatine (see Table 1; Raasch et al., 1995a). Stimulation experiments on animals designed to investigate this question have not been performed until now. In humans, substantially higher plasma concentrations (47 ng ml−1) were determined when compared to rats (Feng et al., 1997). The reasons underlying this large difference remain to be clarified. An age-dependency for agmatine tissue concentrations could not be established, with the exception of the cerebral cortex, where concentrations declined by nearly 50% with age (Raasch et al., 1995a).

Using immunohistochemistry with specific antibodies against agmatine (Wang et al., 1995), agmatine was found to be regionally distributed in the cerebral cortex, the lower brain stem, the midbrain, frontal brain, thalamus and the hypothalamus in rat brain (Otake et al., 1998). In this way the distribution of agmatine-containing neurones correlates with the distribution pattern of α2-adrenoceptors and imidazoline binding sites to the extent that (1) in most agmatine containing regions, α2-adrenoceptors and imidazoline binding sites are also expressed (Kamisaki et al., 1990; de vos et al., 1991; 1994; Bricca et al., 1993; Nicholas et al., 1993; 1996; King et al., 1995; Ruggiero et al., 1995) and (2) agmatinergic neurones are concentrated in brain regions (e.g. cerebral cortex), which project to areas (e.g. striatum and midline thalamus), which contain α2-adrenoceptors and imidazoline binding sites (Berendse & Groenewegen, 1991; Jones & Yang, 1985; Saper et al., 1986). There also appear to be a multitude of interactions between agmatinergic cells and receptor areas in the corticothalamostriatal regulatory loops.

At the cellular level, agmatine could be shown in smooth muscle and endothelial cells. Since ADC is expressed only in endothelial cells and not in smooth vascular muscle cells, it was concluded that agmatine either originates in the serum or is taken up from the endothelial cells and stored in the smooth vascular muscle cells, although a corresponding transporter for agmatine has not yet been identified in the vasculature (Regunathan et al., 1996a). There are, however, reports on an agmatine-transport system of bacterial (Kashiwagi et al., 1986; Driessen et al., 1988) and neuronal origin (Sastre et al., 1997). Glial cells not only express imidazoline binding sites, they also synthesize agmatine (Regunathan et al., 1995a), whereby the agmatine concentration and ADC activity in the cultivated cells are substantially higher than the concentrations in brain, which might indicate that glial cells represent the main site for synthesis and storage. It is well known that cells under culture conditions can undergo alterations in distinct features such as receptor population, enzyme activity and this might also alter agmatine content. This could be why there are differences in agmatine content between neuronal and glial cells. In this respect, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) was able to increase ADC activity without inducing nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activity significantly in astrocytes, whereas LPS stimulated iNOS but not ADC activity. These data suggest that the ADC activity in neuronal tissue is subject to regulation, and that two different stimuli influence two pathways of arginine metabolism in entirely different ways.

At the subcellular level, agmatine was shown by immuncytochemistry to be localized mainly in large dense-core vesicles in the cytoplasm and in the immediate vicinity of the endoplasmic reticulum and the mitochondria (Figure 3; Otake et al., 1998; Reis et al., 1998), which correlates well with the demonstration of a mitochondria-associated ADC (Li et al., 1995). Moreover, an association of agmatine with small synaptic vesicles was shown in the rat hippocampus within the nerve endings, whereby the function of these endings has not yet been clarified. The co-transmitter function to L-glutamate has been speculated, since inhibitory effects at the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor have been attributed to agmatine (Yang & Reis, 1999), which would suggest a regulation of the excitatory effect of L-glutamate via co-transmission.

Release of agmatine

In rat brain slices and synaptosomes, a release of agmatine, but not of putrescine could be shown in response to depolarization with 55 mM KCl (Figure 3; Regunathan et al., 1996b; Reis & Regunathan, 1998). In the absence of Ca2+, the release of agmatine was significantly reduced, suggesting a calcium dependent mechanism. Significant quantities of radiolabelled agmatine could be released from bovine chromaffin cells by 55 mM KCl and 10 pM nicotine induced depolarization (Tabor & Tabor, 1984). Immunocytochemical studies on the storage of agmatine support the findings of a stimulation-receptive agmatine release from neuronal tissue, since agmatine-like immuno-reactivity is primarily associated with small synaptic vesicles (20 – 30 nm diameter) in nerve endings that form asymmetric contacts to the spines of pyramidal cell dendrites. While the adrenals were identified as a source of circulating CDS (Meeley et al., 1992), no data exists about the release of endogenous agmatine into the circulation.

Inactivation of agmatine

The existence of a specific transporter system working against a concentration gradient (Kashiwagi et al., 1986) as well as an agmatine-putrescine antiporter (Driessen et al., 1988) have been shown in prokaryotes. In synaptosomes from rat brain, a selective ATP- and temperature dependent as well as Na-independent agmatine transporter could be shown (Figure 3; Sastre et al., 1997). The affinity of agmatine to this transporter is extremely low with a Km of 18.8 mM. Other polyamine transporters, however, have also shown Km values in the millimolar range (Seiler & Dezeure, 1990). The fact that agmatine uptake can not be inhibited by amino acids, catecholamines or polyamines at concentrations (1 mM) which can be judged as high (with the exception of amino acids) underscores the specificity of the transporter. Combination experiments with carbachol and nicotine have excluded the possibility that the agmatine-transporter is a nicotine-associated ion channel; earlier studies showed that [3H]-agmatine can act as a marker for ion flux through nicotinergic ion channels (Quik, 1985) and that agmatine acts as an antagonist of the retinal nicotine receptor (Loring, 1990). The transporter is also no K+ATP- channel. However, agmatine-uptake can be suppressed by CoCl2, CdCl2 or verapamil and doubled by application of a calcium-free medium, an indication that agmatine is transported through a calcium channel, although it could be excluded that the calcium channels were of an L- or T-type (Sastre et al., 1997). Finally, agmatine-uptake into synaptosomes is blocked by the imidazoline derivatives idazoxan and phentolamine, but not by clonidine, moxonidine, rilmenidine or p-aminoclonidine, so that apart from a guanidine or imidazoline partial structure, other structural properties also contribute to the inhibitory effect. Recently another agmatine uptake system was identified and pharmacologically characterized in human glioma cells; it was energy dependent, and saturable with a Km of 8.6 μM and a Vmax of 64.3 nmol min−1 mg protein−1 but distinct from the putrescine transporter and known amino acid or monoamine carriers and not associated with a calcium- or 5-HT3 receptor channel or an organic cation transporter (Molderings et al., 2001). Those features, especially the much higher affinity (∼2200 fold), clearly indicate its difference from the agmatine transporter identified by Sastre et al. (1997). From all these findings it seems reasonable to suspect that this transporter might be involved in the regulation of extracellular agmatine concentrations.

From bacterial polyamine metabolism it is well known that agmatine can be degraded enzymatically by agmatinase (Satishchandran & Boyle, 1986; Panagiotidis et al., 1987) or agmatine deaminase (Mercenier et al., 1980). The question is now whether the same metabolization pattern can be demonstrated in mammals, and whether an alternative means for putrescine biosynthesis apart from decarboxylation of ornithine (Tabor & Tabor, 1984) exists. The first evidence for a breakdown of agmatine to putrescine with cleavage of urea (Figures 3 and 4) in rat brain was obtained by Gilad et al. (1996a). Later, Sastre et al. (1996b) identified a mitochondrial agmatinase in rat brain with a low affinity for agmatine (Km=5.3 mM), and a Vmax of 530 nmol h−1 mg−1 protein. These enzyme kinetic parameters are comparable with those of the bacterial agmatinase (Satishchandran & Boyle, 1986). When one considers the relatively low concentrations of agmatine in rat brain (Raasch et al., 1995a) and the very low affinity of agmatine to the enzyme, one can reasonably question the extent to which agmatinase is of any physiological relevance. Since agmatinase is co-localized with ADC (Li et al., 1995; Regunathan & Reis, 2000), however, one can not rule out the presence of mM agmatine concentrations in intracellular compartments, which would then represent an adequate substrate concentration for the agmatinase. The high Vmax might also compensate for the lower affinity. A regional heterogeneous distribution of agmatinase has indeed been shown in rat brain (Sastre et al., 1996b), with the highest activity in the hypothalamus, followed by the medulla oblongata and hippocampus, and the lowest activity in the striatum and cerebral cortex. This distribution pattern is largely consistent with the imidazoline binding sites (Mallard et al., 1992), but less so with the α2-adrenoceptors (Ruggiero et al., 1995). Moreover, the distribution of agmatinase seems not to be consistent with the regional pattern of agmatinergic neurones in the CNS as determined by immunocytochemistry (Wang et al., 1995).

Outside of the CNS, agmatinase could also be demonstrated in macrophages (Sastre et al., 1998), where its activity can be stimulated by LPS, but inhibited by TGF-β and IL-10. Since ADC in macrophages is inhibited by LPS, TGF-β, and IL-10, and the activity of iNOS is also regulated by these substances (Wang et al., 1995), it seems reasonable to suggest that arginine might be metabolized by these three enzymes, and possibly other enzymes, to agmatine, nitric oxide (NO) and polyamines. Aside from agmatinase-induced degradation, agmatine can also be metabolized in the kidney by diamine oxidase (DAO; Figure 4; Holt & Baker, 1995; Lortie et al., 1996), where the affinity of agmatine to this enzyme is in the micromolar range and therefore substantially higher than that of agmatinase. Studies with specific DAO inhibitors underscore the importance of DAO in agmatine metabolism. Indeed, it has been speculated that specific inhibition of DAO by the antidepressant drug phenelzine might lead to an increase in serum and tissue concentrations of agmatine and in this way contribute to its antidepressive efficacy (Holt & Baker, 1995). However, this hypothesis is weakened by the fact that (1) no changes in plasma or tissue levels of agmatine were found during chronic DAO blockade; and (2) no DAO activity could be demonstrated in the brain (Lortie et al., 1996), suggesting an organ specific metabolism of agmatine, i.e. degradation by DAO in the kidney and agmatinase in central tissues. Moreover, it seems feasible that an increase in histamine due to DAO blockade might participate in antidepressive effects, since an antidepressant-like effect, via activation of H1-receptors, has been suggested elsewhere (Lamberti et al., 1998).

In studies by Holt & Baker (1995), agmatine (50 μM) had no influence on either the semicarbazide-sensitive aminoxidase (SSAO) or MAO. By using specific substrates it could be shown that agmatine does not modulate either MAO-A or MAO-B; hardly surprising to many, given that other polyamines such as putrescine are not substrates for MAO (Blaschko, 1974). These results are somewhat inconsistent with the fact that the I2-binding site has been characterized as a regulatory subunit of MAO (Tesson & Parini, 1991; Tesson et al., 1991; 1995; Carpene et al., 1995; Raasch et al., 1996; Raddatz et al., 1995; 1997; Escriba et al., 1996; Raddatz & Lanier, 1997) and that agmatine has been identified as a ligand at imidazoline binding sites (Li et al., 1994a; Piletz et al., 1995; 1996a). In this respect, the fact that agmatine is able, just as other I2-ligands, to inhibit MAO isolated from rat liver, does not seem completely surprising (Figure 3; Raasch et al., 1996; 1999). The IC50 value of 167 μM reported by Raasch et al. (1999) is about 3 fold higher than the maximal concentration used by Holt & Baker (1995) in their study. At 50 μM only a minor inhibition of MAO could be seen, even in Raasch et al.'s (1999) study. However, it seems more than doubtful that the agmatine-induced inhibition of MAO in vitro should have some relevance in vivo, since plasma and tissue concentrations of agmatine are approximately 500 – 40,000 fold lower than the EC50 values in the in vitro assays. Furthermore, an interaction between endogenous agmatine and MAO inhibitors is unlikely because of their different sites of action.

Biological functions of agmatine

Effects of agmatine on the central nervous system (Antinociceptive effects of agmatine)

Since the mid 80's it has been known (Gossop, 1988) that clonidine potentiates the analgesic activity of opiates, an effect which is purportedly mediated via α2-adrenoceptors (Maze et al., 1988; Quan et al., 1993). Studies on α2A-knock-out mice have clearly revealed the participation of α2A-adrenoceptors in analgesia (Hein et al., 1999; Hein, 2001). In this context, Fairbanks & Wilcox (1999) demonstrated that the centrally acting antihypertensive drug moxonidine produces antinociception in mice with dysfunctional α2A-adrenoceptors (α2A-D79N not a null mutation; Macmillan et al., 1996), whereby the selective α2A-adrenoceptor antagonist SK&F86466 (Hieble et al., 1986) and the I1-binding site/α2A-adrenoceptor mixed antagonist efaroxan (Haxhiu et al., 1994) antagonizes the moxonidine effects. The following mechanisms may underlie these results: (1) other substypes of α2A-adrenoceptor – either α2B or α2C – may participate in analgesia (Fairbanks & Wilcox, 1999); (2) since gene expression of the α2A-adrenoceptor is reduced by 80% via targeted mutation in the α2A-D79N mice (Macmillan et al., 1996), there is still the possibility of a residual activity of the α2A-adrenoceptor. This conclusion is authoritatively confirmed by the observation of different physiological effects between mice with fully disrupted α2A-adrenoceptors (α2A-adrenoceptor knock out mice) and those with gene-targeted mutation receptors (α2A-D79N, Altman et al., 1999); (3) imidazoline binding sites may induce antinociceptive effects (Figure 1), which raises the question of the biological relevance of agmatine mediating such effects, since agmatine was shown to be synthesized, stored, released and metabolized either by uptake or by enzymatic breakdown in tissue of neuronal origin (for detailed information see sections above).

Agmatine alone (0.1 – 10 mg kg−1) was ineffective in the mouse tailflick assay, but after intravenous or intrathecal application it potentiated the analgesic efficacy of morphine dose-dependently by factors of five or nine, respectively, without affecting morphine-induced gastrointestinal transit (Kolesnikov et al., 1996). Such results were confirmed by using slightly modified study protocols of Bradley & Headley (1997) and Horváth et al. (1999). The potentiation of morphine activity by agmatine seems to be mediated via a δ- rather than a κ1- or κ3 opiate receptor mechanism. Moreover, chronic studies also showed that agmatine, at a dose (0.1 mg kg−1) which did not potentiate morphine activity, reduced the development of tolerance during a 10-day morphine regime. It is not unlikely that this effect is mediated via I2-binding sites, since selective I2-ligands such as idazoxan or 2-benzofuranylimidazoline also suppressed the morphine-induced development of tolerance, while selective I1-ligands or α2-adrenoceptor antagonists did not (Boronat et al., 1998). How this binding site mediates suppression of the development of tolerance is still not completely understood, even considering the fact that I2-binding sites have been implicated as a regulatory binding site on MAO. Moreover, results using idazoxan, showing increases in cerebral levels of 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylethyleneglycol (MOPEG) and 3,4,dihydroxy-phenylacetic acid (DOPAC) in morphine-withdrawn mice and an enhancement of morphine's elevating effects on MAO (Airio & Ahtee, 1999) suggests rather an interaction with MAO than an increase in cerebral noradrenaline turnover and release as a mechanism underlying idazoxan's overcoming of morphine tolerance. However, such a noradrenaline release can not be mediated classically via presynaptic α2-adrenoceptor, since it has repeatedly been shown that idazoxan inhibits noradrenaline release by this mechanism (Molderings et al., 1997). Another I2-mediated mechanism, possibly attributed to the 28-kDa protein which is present in MAO deficient mice (Remaury et al., 2000), was speculated to be involved in the reduction of morphine tolerance, since an astrocyte hyperplasia following chronic dosing of I2-selective imadazoline derivatives (Olmos et al., 1994; Alemany et al., 1995) can antagonize the morphine-induced suppression of astrocyte growth (Stiene-Martin et al., 1991; Stiene-Martin & Hauser, 1993). Since astrocytes play an important role in the regulation of synaptic density (Meshul et al., 1987), the astrocyte growth can modulate synaptic plasticity and appears to be associated with chronic morphine dosing (Nestler et al., 1996). Recently, a functional interaction between opioid- receptors and I2-binding sites could be shown. The first results on a so-called Gi-Go transducer protein have also been obtained, a protein which appears to play some role in this interaction (Sanchez-Blazquez et al., 2000). However, the low affinity of agmatine to the I2-binding sites compared to the selective I2 ligands provides reason to doubt this concept. Moreover, the concept of an I2-mediated mechanism for agmatine's antinociceptive effects contradicts the conclusion derived from the findings using α2A-adrenoceptor knock out mice, in which if anything a participation of I1-binding sites was suggested. Overall, it must be determined whether endogenous agmatine would participate in such an antinociceptive effect. To answer this, physiological or pathophysiological conditions have to be identified whereby agmatine levels (e.g. depression; Halaris et al., 1999) as well as morphine's effects are altered.

Aside from improvements in development of tolerance and morphine's analgesic action, agmatine also dose-dependently improved (20 – 40 mg kg−1) acute morphine withdrawal symptoms under naloxone in rats, such as jumping, wet dog shakes, writhing, defecation, ptosis, teeth chattering and diarrhoea (Aricioglu-Kartal & Uzbay, 1997). However, this behavioural pattern could not be induced by giving agmatine alone. A lacking impediment of locomotor activity under agmatine alone and in combination with naloxone suggests that the observed agmatine effects were not due to sedation or muscle relaxation. The authors of this study also associated the effects observed less not so much with an interaction at α2-adrenoceptors, but much more with an interaction at imidazoline binding sites or NOS.

(Effects of agmatine on the NMDA receptor) After it was recognized that NMDA receptors participate in the development of opiate dependency and development of tolerance (Elliott et al., 1995; Trujillo, 1995), it had to be asked whether ligands of imidazoline binding sites modulate the above discussed morphine tolerance via an NMDA receptor-mediated mechanism. The binding of the NMDA ligand [H]-(+)-MK-801 to cerebral cortex membranes can be reduced by various imidazolines with weak potencies (Ki) of 37 – 190 μM, whereby the potencies of the I1-ligand (moxonidine), the I2-ligand (idazoxan) and the α2 agonist (RX821002) were not different (Boronat et al., 1998). This suggests a lack of a correlation between the potency at NMDA receptors and the ability to prevent opiate tolerance. Compared to the other substances, agmatine had the lowest affinity for the I2-binding site, but the highest affinity for the NMDA receptor (Boronat et al., 1998). Moreover, agmatine differed from the other substances in this study since it had a significantly shallower Hill-Slope and the curve-fitting characteristics were different. All these signs could mean that agmatine differs from other imadazoline derivatives in its binding behaviour to NMDA receptors, and that even if this hypothesis were to be rejected for the imadazoline derivatives, the agmatine effects on morphine tolerance and potentiation could be mediated via NMDA receptors (Figure 3).

Against this background, whole cell patch clamp studies on cultivated hippocampal neurones showed that agmatine specifically induces a voltage and concentration-dependent block of the NMDA current, but not the AMPA- (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid) or kainate flux (Yang & Reis, 1999). This inhibition was reversible and most potent at hyperpolarizing membrane potentials, and less effective at positive potentials. Even in the presence of 10 μM glycine, agmatine (100 μM) showed no measurable whole-cell flux, which does not support an NMDA-agonistic effect of agmatine. As a NMDA antagonist, (±)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5) inhibits both, the inward and outward directed NMDA current. In the presence of agmatine there was an additional inhibition of the AP5-inhibited NMDA current, comparable to the inhibition under agmatine alone, making it reasonable to presume that agmatine is not a competitive NMDA antagonist. It could be shown, however, that agmatine interacts with the NMDA-pore directly at a site part-way across the membrane electric field (Yang & Reis, 1999). By investigating various agmatine structural analogues (arcaine, putrescine, spermine, arginine) regarding their ability to alter NMDA current, it could be shown that the guanidine structure of agmatine appears to be essential for suppressing NMDA current. A similar structure-activity relationship was also reported concerning the MAO inhibitory activity of agmatine (Raasch et al., 1999). Since the agmatine concentration (100 μM) required for an effective NMDA receptor blockade is relatively high, one has to question the physiological significance of this effect, especially against the background of published agmatine tissue concentrations (Raasch et al., 1995a; Feng et al., 1997; Stickle et al., 1996). However, since agmatine is not uniformly distributed in the CNS, but preferentially distributed in certain areas and subcellular structures (Otake et al., 1998; Reis et al., 1998), a concentration adequate to block NMDA might be reached, providing that the agmatine becomes released.

Glutamate, the most important excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, also is potentially neurotoxic (Choi et al., 1988). Glutamate exposure to primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells has been characterized as a model for neurotoxic effects, which correlates with effects at NMDA receptors (Lysko et al., 1989). NMDA antagonists are consequently able to suppress such neurotoxic glutamate effects. In this context, imadazoline derivatives revealed some neuroprotective efficacy (Gustafson et al., 1990; Maiese et al., 1992; Olmos et al., 1996; 1999; Degregorio-Rocasolano et al., 1999). It therefore seemed natural to study whether agmatine, as an endogenous ligand of imidazoline binding sites with NMDA antagonistic activity (see above), possesses any neuroprotective activity. In cultivated cerebellar neurones, agmatine suppresses the NMDA-induced neurotoxic effects at concentrations of between 10 – 100 μM, but at higher concentrations it becomes toxic itself (LD50: 700 μM; Gilad et al., 1996b), perhaps by inhibiting growth effects as discussed later. Similar neuroprotective effects in cell cultures were shown by Olmos et al. (1999), who associated this effect of agmatine directly with an antagonistic activity at the NMDA receptor. In vivo studies on gerbils revealed neuroprotection after a global frontal brain ischaemia following an intraperitoneal application of agmatine (10 – 100 mg kg−1). These results occurred in line with a complete (after agmatine treatment) or partial (controls) recovery of the neurological deficit within 72 h, as revealed by the motor performance of the animals (Gilad et al., 1996b). The importance of endogenous agmatine during cerebral ischaemia is also stressed by the fact that the activity of ADC is increased transiently and in parallel to ODC by about 7 fold (Gilad et al., 1996c). This study seems to be a very important study, since it was shown that due to pathophysiological events the rate limiting enzyme of agmatine's biosynthesis is enhanced, suggesting a biological function for agmatine. As in many other functional studies, however, the applied dose of agmatine was indeed very high. Also, the extent of the agmatine transport is unknown in the brain and might indeed be limited under normal conditions. However, it is known that the blood-brain barrier after an ischaemic insult is damaged very early on and in a long-lasting manner (Dietrich et al., 1991), which could allow better access to the brain for exogenous substances. Nevertheless, circulating agmatine concentrations are very low (Raasch et al., 1995a), so that it is not very likely that endogenous agmatine from the periphery will contribute to neuroprotective effects. Apart from this it appears questionable, especially considering the relatively low affinity of agmatine to the NMDA receptor (Ki=219 μM, Olmos et al., 1999) and the endogenous tissue concentrations, whether endogenous agmatine could be held accountable for the survival-promoting effects observed in vivo (Gilad et al., 1996b). But at this point we must refer once again to the non-uniform distribution of agmatine in the CNS (Otake et al., 1998) which could theoretically approach efficacious concentrations at the NMDA receptor, provided of course that it is released.

(Agmatine's significance in depression) Various findings indicate a potential pathophysiological role of imidazoline binding sites in the development of depression (Figure 1): the density of I1-binding sites in human platelet plasma membranes is upregulated in depressive patients and normalized by antidepressive therapy (Piletz & Halaris, 1995; Piletz et al., 1996b,1996c). A similar increase in I1-binding sites was observed in untreated women with dysphoric premenstrual syndrome (Halbreich et al., 1993). Alterations in various imidazoline binding site proteins (45-kDa, 29/30-kDa) could be shown by Western blotting in membranes from platelets and brains of unipolar depressive patients, and from cortical autopsy samples from suicidal individuals (Sastre et al., 1995; Garcia-Sevilla et al., 1996; 1998a). The concentration of agmatine was raised in the plasma of depressed patients compared to a control group (70.6±6.5 vs 38.5±5.4 ng ml−1, P<0.05). After treatment with the antidepressant bupropion, agmatine plasma concentrations normalized to 57.0±6.7 ng ml−1, but no correlation between the bupropion and agmatine plasma concentrations was found (Halaris et al., 1999). At the same time the density of I1-binding sites and the immunodensity of a 33-kDa band in platelet membranes from depressive patients increased compared to controls. Both parameters fell to control levels with bupropion treatment, whereby the number (Bmax) of I1-binding sites correlated well with the agmatine plasma concentration (r=0.800, P=0.005). The finding regarding elevated levels of agmatine and I1-binding sites is surprising, since upregulation of an endogenous ligand normally occurs in line with a downregulation of its receptor, and vice versa. Whatever causes this uniform elevation of those parameters remains unclear, but the course of disease might play a significant role. Hence longer-lasting, disease-following studies on plasma agmatine concentrations and receptor densities in platelets are necessary to provide a satisfactory and plausible explanation. For other neurodegenerative disorders (e.g. Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, glial tumours), alterations in the expression of imidazoline binding sites in the brain or platelets could also be shown (Garcia-Sevilla et al., 1998b; 1999; Ulibarri et al., 1999). However, until today no studies have been performed, analogous to the depression studies, which have pursued the question of changes in agmatine plasma concentrations and their potential role in those diseases.

Cardiovascular properties of agmatine

(Effects of agmatine on isolated vessels and atria (for overview see Table 3)) Agmatine exerted no effect of its own and failed to alter the concentration-dependent contractile effects of the α2-adrenoceptor agonist UK14304 on the KCI-precontracted porcine palmar lateral vein, and unlike clonidine, agmatine did not increase contractility in the endothelium-denuded thoracic artery of the rat (Pinthong et al., 1995a). These results were confirmed both in intact and endothelium-denuded thoracic aortal segments (Gonzalez et al., 1996; Schäfer et al., 1999a). Agmatine also did not influence the contractile responses either to clonidine or phenylephrine (Schäfer et al., 1999a). Similarly, agmatine failed to impart any direct inotropic activity in the isolated, electrically stimulated atrium. In contrast, the imidazoline derivatives cirazoline and moxonidine produced significant increases in contractility, which were found to be due to an α1-adrenoceptor-mediated mechanism (Raasch et al., 2000). Such negative results on contraction were confirmed in studies where agmatine (0.1 – 100 μM) was ineffective at inhibiting electrically stimulated contraction of the rat isolated vas deferens and isolated guinea-pig ileum (Pinthong et al., 1995a). This is inconsistent with the effects of CDS on these preparations (Diamant & Atlas, 1986; Felsen et al., 1987; Meeley et al., 1992

Table 3.

Effects of agmatine on cardiovascular functions

It is also plausible, but rather unlikely, that a null effect of agmatine on isolated vp>essels may represent the sum of a contracting and a dilating effect. Regarding potential interactions with relaxing neurotransmitters, an interaction with NO (Auguet et al., 1995; Galea et al., 1996; Schwartz et al., 1997) could be shown, but not with acetylcholine (Colucci et al., 1998) or bradykinin (Gao et al., 1995). Concerning interactions with vasoconstrictive neurotransmitters, some evidence exists for angiotensin II (Regunathan & Reis, 1997) and catecholamines (Gonzalez et al., 1996; Schäfer et al., 1999b; Molderings et al., 2000).

At first it was speculated whether agmatine might function as an alternative substrate for endothelial NOS (Ishikawa et al., 1995), and in this way contribute towards vasodilatation. This hypothesis was confirmed by the fact that agmatine provokes no relaxation of isolated vessel rings denuded of endothelium or pretreated with L-NAME. Agmatine itself is not a precurser for NO-synthase, but is rather a weak competitive inhibitor of various NOS isoenzymes (Figure 3; Auguet et al., 1995; Galea et al., 1996). The clearest effect was an inhibition of iNOS, whereby eNOS was maximally inhibited by 60% with 10 mM agmatine (Galea et al., 1996). However, even though agmatine has been detected in endothelium (Regunathan et al., 1996a), such high concentrations in the millimolar range are rather unlikely in vivo (Raasch et al., 1995a). Therefore, the relevance of this in vitro finding for the in vivo situation remains dubious.

The stimulation of presynaptic α2-adrenoceptors leads to vasodilatation, mediated via inhibition of noradrenaline release from sympathetic varicosities (Langer & Hicks, 1984). Agmatine suppresses noradrenergic neurotransmission in rat tail arteries, since it inhibits contraction after transmural nerve stimulation for about 10 min. However, contraction by exogenous noradrenaline was not inhibited, so that the authors concluded a presynaptic effect of agmatine (Gonzalez et al., 1996). This was confirmed by dosing with idazoxan or rauwolscine which antagonized the agmatine-mediated effect and resulted even in a delayed potentiation of the contraction response. The unchanged [3H]-noradrenaline uptake into chromaffin cells showed that this hypothetical presynaptic effect was not mediated by an inhibition of noradrenaline reuptake into the sympathetic nerve endings (Gonzalez et al., 1996). An inhibition of noradrenaline release by presynaptic imidazoline binding sites with a subsequent vasodilatation could be demonstrated in various vascular preparations and in the pithed SHR (Figure 3; Göthert & Molderings, 1991; Molderings et al., 1991; Göthert et al., 1995; Molderings & Göthert, 1995; Häuser et al., 1995; Raasch et al., 1999; Schäfer et al., 1999b). Nevertheless, the mechanism by which agmatine modulates noradrenaline release remains unclear: Firstly, it was demonstrated (Schäfer et al., 1999b) that agmatine failed to reduce noradrenaline release when α2-adrenoceptors were blocked reversibly and irreversibly by rauwolscine and phenoxybenzamine, respectively, but not under selective blockade of I1-binding sites with AGN192403 (Munk et al., 1996). These data contradict at least in part (Schäfer et al., 1998) the only sparse findings published until now regarding AGN192403 (Munk et al., 1996), which have characterized this agent as a high affinity I1-ligand with no affinity for α2-adrenoceptors, showing neither agonistic nor antagonistic effects on blood pressure and the sympathetic nervous system. Similar effects of agmatine on noradrenaline release modulated by presynaptic imidazoline binding sites were also demonstrated in various vascular preparations (Molderings & Göthert, 1995). This study suggested that the presynaptic activity of agmatine is probably related to a regulation of noradrenaline release by presynaptic imidazoline binding sites. However, a ganglionic mechanism can not be excluded since (1) I1-binding sites are present at the cell bodies of sympathetic ganglia and adrenal medulla (Molderings et al., 1993); and (2) agmatine blocks nicotinic-cholinergic transmission in sympathetic ganglia (Loring, 1990). Furthermore, since activation of I1-binding sites releases prostaglandins (Ernsberger et al., 1995) and histamine (Molderings et al., 1999a), which were both shown to diminish noradrenaline release (Wennmalm & Junstad, 1976; Göthert et al., 1999), it also seems likely that agmatine reduces noradrenaline overflow via such an indirect mechanism. Secondly, agmatine was suggested to act as an antagonist at the ligand recognition site of the α2D-adrenoceptor and enhances the effects of the α2-adrenoceptor agonist moxonidine probably by binding to an allosteric binding site on the α2D-adrenoceptor (Molderings et al., 2000). However, all those effects (Schäfer et al., 1999b; Molderings et al., 2000) were obtained with agmatine concentrations in the millimolar range, which generates serious doubts of any in vivo relevance. This dual interaction of agmatine at α2D-adrenoceptors probably explains the inconsistent effects of agmatine on catecholamine release, since data also exists concerning a prosecretory effect on adrenaline and noradrenaline release from chromaffin cells (Li et al., 1994a), adrenal medulla (Häuser et al., 1995) and vas deferens (Jurkiewicz et al., 1996). It is conspicuous, however, that divergent results have also been published for other imidazoline derivatives concerning a catecholamine releasing effect (Regunathan et al., 1991a,1991b; Reis et al., 1992; Ohara-Imaizumi & Kumakura, 1992; Steffen & Dominiak, 1996; Jurkiewicz et al., 1996). Overall, the inconsistent literature emphasizes that the effects of imidazoline derivatives and especially agmatine on the sympathetic nervous system are complex.

(Effects of agmatine on blood pressure and heart rate in vivo (for overview see Tables 3 and 4 and Figure 3)) After intravenous administration, agmatine reduces the blood pressure of anaesthetized SHR or Sprague Dawley rats at a dose of 100 μg kg−1 (Sun et al., 1995; Gao et al., 1995; Häuser & Dominiak, 1995; Schäfer et al., 1999a); although doses of 10 mg kg−1 and more showed long-lasting blood pressure effects (until 25 min), no reflex tachycardia but rather a significantly reduced heart rate were observed. Compared to pithed SHR, agmatine clearly exerts a higher blood pressure reducing potency in anaesthetized animals (Schäfer et al., 1999a). After intravenous application, agmatine exerted no influence on the pressor activity of clonidine. Even though clonidine has an approximately 700 fold higher affinity for I1-binding sites and a 115 – 246 fold higher affinity for all three α2-adrenoceptor subtypes, agmatine even at a 10,000 fold higher dose compared to clonidine had no effect on clonidine-induced blood pressure increases in pithed rats. Hence, antagonistic or CDS-like effects at the α2-adrenoceptors and I1-binding sites in the vessel musculature can be excluded. In complete contrast, an additive blood pressure and heart rate reduction could be seen in anaesthetized SHR during continuous clonidine infusion with agmatine doses as low as 100 μg kg−1, which suggests in fact a synergistic effect to clonidine (Schäfer et al., 1999a,1999b).

Table 4.

Blood pressure and heart rate changes after central agmatine-dosing

The lack of agmatine effect on isolated vessels (Gonzalez et al., 1996; Pinthong et al., 1995a; Schäfer et al., 1999a), as well as the markedly lower dose required to produce a comparable reduction of blood pressure in anaesthetized compared to pithed SHR (Schäfer et al., 1999a), suggests a central regulation of blood pressure (see Table 4 for an overview). However, no effects of an intracerebroventricular application of agmatine (1 – 1000 nmol 5 μl−1) on blood pressure and heart rate were observed (Penner & Smyth, 1996). Also, Head et al. (1997) saw no increase in heart rate in conscious rabbits, except at high doses (100 μg kg−1) that caused agitation, tachypnoea, increase in blood pressure and a reversal of the dose-dependent bradycardia effect (0.01 – 10 μg kg−1). These negative findings on blood pressure and heart rate were also confirmed by Sun et al. (1995) after an injection of agmatine into the RVLM of anaesthetized rats. In contrast, when agmatine was injected into the greater cisterna of anaesthetized rats (Sun et al., 1995) and conscious rabbits (Szabo et al., 1995), blood pressure and sympathetic nerve activity increased, indicating a site dependency of central application which might be due to differences in the pattern of imidazoline binding sites and α2-adrenoceptors with different species or different modes of application. This hypothesis is confirmed by findings of Schäfer et al. (1999a), whereby agmatine caused a dose-dependent, significant increase in blood pressure without changing the heart rate after its intracerebroventricular injection to SHR, whereas no change in blood pressure but an increase in heart rate was observed after its injection into the IV ventricle. A comparison between moxonidine and agmatine after injection into the IV-ventricle of conscious rabbits revealed that both substances caused a similar bradycardial effect (Head et al., 1997). These effects were attenuated by efaroxan (I1- and α2-adrenoceptor antagonist) and 2-methoxy-idazoxan (α2-adrenoceptor antagonist). From these results Head et al. (1997) concluded that agmatine might be an α2-adrenoceptor agonist. The fact that agmatine exerts no hypotensive effect as other agonists for central α2-adrenoceptors contradicts this. The authors saw an indication that agmatine possessed a simultaneous hypertensive activity which might mask an α2-adrenoceptor-induced hypotension. The dual interaction of agmatine on noradrenaline release via an allosteric activation or a competitive antagonism at α2D-adrenoceptors (Molderings et al., 2000) could probably contribute to this effect and strengthen the hypothesis of Head et al. (1997). Both in conscious rabbits and anaesthetized SHR, ventricularly applied agmatine shows no effects on blood pressure after induction of hypotension by clonidine or moxonidine (Head et al., 1997; Schäfer et al., 1999a), while bradycardia is potentiated by agmatine (Schäfer et al., 1999a). If the functional data for CDS and agmatine after central administration are compared, there appears to be absolutely no correlation between the two substances.

Agmatine and its potency on cell growth

Since polyamines participate in DNA replication and cellular proliferation (Pegg & Mccann, 1982), it was a plausible hypothesis that agmatine might also be involved in cellular growth processes. Regunathan et al. (1996; 1997; 1999) demonstrated a partial inhibition of agmatine (100 – 1000 μM) on foetal calf serum-stimulated thymidine incorporation in endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells and asterocytes, whereby measurements of lactate dehydrogenase release and morphological examination ruled out a cytotoxic effect being responsible for the inhibition of growth (Regunathan et al., 1999). The low potency of agmatine compared to idazoxan regarding proliferation inhibition might be due to its lower affinity towards I2-binding sites compared to other imadazoline derivatives. However, the manner by which I2-binding sites (which are associated with MAO and located in mitochondria) should mediate growth effects has not yet been clarified. Due to its rapid metabolism to putrescine (Gilad et al., 1996a), it might be speculated whether the antiproliferative effects of agmatine can be attributed to other polyamines. However, putrescine acts as a proliferation promoter, since it doubled thymidine incorporation (Regunathan et al., 1996a; Regunathan & Reis, 1997), and would therefore act antagonistically to agmatine. The antiproliferative effects of agmatine and idazoxan in vascular smooth muscle cells could also be observed following other stimulatory conditions such as noradrenaline, angiotensin II or platelet derived growth factor (PDGF; Regunathan & Reis, 1997). Growth factors, especially PDGF, activate primarily membrane receptor-associated tyrosine kinases, which trigger intracellular processes such as activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and various mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAP-kinases), which ultimately result in expression of the immediate-early genes c-fos and c-myc are involved in DNA-synthesis and cell division (Somlyo & Somlyo, 1994; van biesen et al., 1995). Since both angiotensin II and noradrenaline activate PKC and MAP kinases via a G-protein coupled mechanism, it has to be assumed that the antiproliferative effect of agmatine is a mechanism occurring further downstream (Figure 5) since the effects of both G-protein-coupled agents and PDGF (tyrosine kinase mediated) could not be inhibited. It is not known whether this interaction occurs within the cytosolic signal transduction cascade (e.g. Ca2+, PKC, MAP kinase) or at a transcriptional level. Satriano et al. (1998) also showed that agmatine suppresses growth of MTC-cells (mouse kidney proximal tubule cells) by thymidine incorporation experiments, an effect that could be antagonized by putrescine. The authors, however, pursued a completely different hypothesis to explain the agmatine-mediated cell growth, which was based on the following findings: (1) Agmatine time-dependently reduced the intracellular content of putrescine and spermidine. (2) Agmatine was not converted intracellularly to polyamines (in MTC cells). (3) Exogenous agmatine reduced ODC activity dose- and time-dependently in MTC cells, where even high agmatine concentrations (1 mM) exert no cytotoxic effects; the specificity of this effect could also be seen with other cell lines, and such findings were also confirmed by Vargiu et al. (1999). (4) Agmatine (1 mM) time-dependently suppressed the polyamine transporter in MTC cells, and this results in a reduction of the intracellular content (c. 15% of control values) of exogenously applied [3H]-putrescine. This result could also be confirmed by others, where it was shown that intracellular spermidine content in rat hepatocytes can be reduced by an agmatine-induced inhibition of uptake (Vargiu et al., 1999). (5) Agmatine induced antizyme which regulates the synthesis and transport of polyamines. This was established by (a) an agmatine-dependent translational frame-shift of antizyme mRNA to produce a full-length protein and (b) a suppression of agmatine-dependent inhibitory activity by either anti-antizyme IgG or antizyme inhibitor. Satriano et al. (1998) therefore deduced the following hypothesis (Figure 4): the intracellular polyamine content, which plays an important role in DNA-replication and cell division, is regulated either by endogenous cellular biosynthesis from arginine to ornithine and further on under ODC catalysis to putrescine, or by the uptake of exogenous polyamines. Both the membrane-located polyamine transporter as well as ODC are subject to regulation by antizyme, whereby this protein exerts an inhibitory effect on both proteins. Agmatine acts as a regulator of antizyme, which means that agmatine is able to control synthesis.

Figure 5.

Influence of agmatine on cell growth: Control of cell growth can be attributed to two different pathways, namely a membrane receptor controlled pathway, and a pathway dependent on cellular polyamine content. Putrescine content is regulated by an active tranport mechanism as well as by arginine metabolism. Agmatine acts by stimulating an antizyme that inhibits both processes, so that a reduction in putrescine content occurs which contributes to an antiproliferative activity for agmatine. Agmatine also stimulates the spermidine/spermine acetyltransferase (SSAT), the key rate-limiting enzyme for polyamine intraconversion, and simultaneously inhibits S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (SAMDC), an enzyme which also has a modulating effect on intracellular polyamine content. Growth factors also stimulate membrane-located receptors. Following stimulation of protein kinase C (PKC) and MAP kinase (MAPK), expression of c-FOS and c-MYC occurs which eventually leads to DNA replication, cell proliferation and cell growth. Whether agmatine exerts an influence on this signal cascade has not yet been established.

A third hypothesis for agmatine's antiproliferative effects is that agmatine regulates the interconversion pathway of polyamine metabolism at the level of the rate-limiting enzyme (Figure 5). In hepatocyte cultures agmatine (0.5 mM) inhibits cell growth and increases the activity of the spermidine/spermine acetyltransferase (SSAT) about 10 – 25 fold in a manner dependent on oxygen saturation (5 vs 21%). This result was confirmed at the protein level, i.e. the increase in activity was due to an increased expression of SSAT (Vargiu et al., 1999). The content of putrescine simultaneously increases in line with reductions in spermine and spermidine, whereby putrescine-accumulation was considered to be responsible for the reduced ODC activity, since it is also known that the biosynthesis of putrescine is regulated via a negative feedback mechanism (Persson et al., 1986). The observed increase in activity of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (SAMDC), which catalyses the breakdown of putrescine to spermidine and spermine, appears to be a consequence of the increased intracellular putrescine content. The authors attributed the observed inhibition of cell growth mainly to the depletion of spermidine and spermine. However, since cellular putrescine levels increase concomitantly, it seems somehow unclear whether cell growth should be inhibited, since putrescine causes the opposite effects (Regunathan et al., 1996a; Regunathan & Reis, 1997). Moreover, Vargiu et al. (1999) attributed the inhibition of cell growth solely to an agmatine-induced modification of putrescine metabolism. However, they ignored the observation that total polyamine content in cells increased by 40% depending on the agmatine concentration, which would indicate an alteration in uptake or biosynthesis, although both were in fact shown to be reduced (Satriano et al., 1998; Vargiu et al., 1999). Some questions, therefore, remain to be answered.

Taken together, all three hypotheses failed more or less to explain whether agmatine's mediated growth effects would be mediated via imidazoline binding sites, a fact which would strengthen the hypothesis of an endogenous ligand. In case of a growth control of agmatine via a feedback regulation of enzyme activity, as shown for ODC (Vargiu et al., 1999), agmatine would indeed be biologically active, possibly as an intermediate in the metabolism of arginine and ornithine to the polyamines, but it would not be a compulsory endogenous ligand for imidazoline binding sites. Another limitation of all three hypotheses is the fact that agmatine inhibits growth at concentrations (0.1 – 1 mM) which although non-cytotoxic (Vargiu et al., 1999), are much higher than circulating agmatine and even tissue concentrations. Therefore, the biological significance of this agmatine effect remains uncertain.

Effects of agmatine on renal function

Renal sodium regulation is important both under normal and pathological conditions for circulatory regulation. A range of different central and peripheral parameters influence sodium excretion and reabsorption. The role of α-adrenoceptors in this context has been demonstrated (Michel & Rump, 1996). Radioligand binding studies succeeded in demonstrating both α2-adrenoceptors as well as imidazoline binding sites, where different distributions could be shown within the kidney (Coupry et al., 1990; Evans & Haynes, 1995; Ernsberger et al., 1995). Moxonidine studies suggested a functional participation of imidazoline binding sites in natriuresis (Allan et al., 1993; 1996), but it is not yet clear whether moxonidine influences sodium excretion and urinary flow via a central and/or peripheral mechanism (reviewed by Smyth & Penner, 1999). In this context the question arises as to the renal function of agmatine, especially considering its demonstration in both brain and kidney (Raasch et al., 1995a; Lortie et al., 1996).

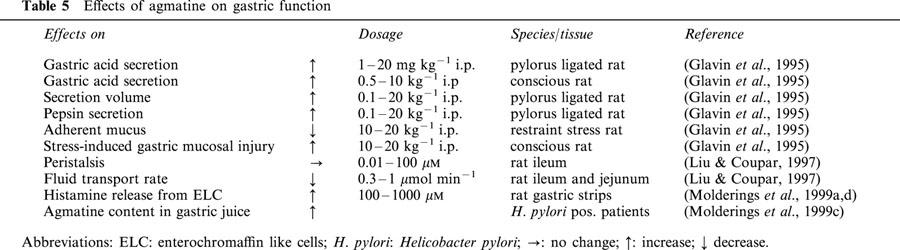

At concentrations that induce no changes in haemo-dynamics or creatinine clearance, agmatine as well as the I1-ligands moxonidine, clonidine and 2,6-dimethyl-clonidine increase urinary flow-rate, whereby agmatine first shows significant changes at ∼10 fold higher doses (Allan et al., 1993; Li et al., 1994b; Ernsberger et al., 1995; Penner & Smyth, 1996). The increase in urinary flow under moxonidine, 2,6-dimethylclonidine and agmatine results from an increased osmotic clearance, while under clonidine it is due to an increased clearance of free water, consistent with the imidazoline-mediated inhibition of the Na+/H+-exchange in isolated renal tubular cells (Bidet et al., 1990). This suggests that the osmotic clearance is possibly an imidazoline binding site-mediated effect, but that free water clearance might be due to an α2-receptor-related mechanism (Smyth & Penner, 1995), since compared to clonidine the relative affinities of agmatine, moxonidine and dimethyl clonidine are higher for imidazoline binding sites than they are for α2-adrenoceptors (Ernsberger et al., 1995).