Abstract

Thrombin, generated in the circulation during injury, cleaves proteinase-activated receptor 1 (PAR1) to stimulate plasma extravasation and granulocyte infiltration. However, the mechanism of thrombin-induced inflammation in intact tissues is unknown. We hypothesized that thrombin cleaves PAR1 on sensory nerves to release substance P (SP), which interacts with the neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R) on endothelial cells to cause plasma extravasation.

PAR1 was detected in small diameter neurons known to contain SP in rat dorsal root ganglia by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization.

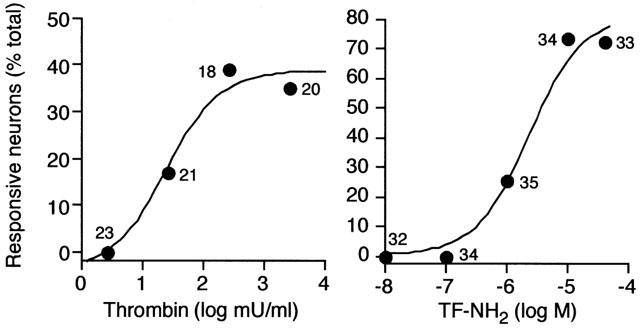

Thrombin and the PAR1 agonist TFLLR-NH2 (TF-NH2) increased [Ca2+]i >50% of cultured neurons (EC50s 24 mu ml−1 and 1.9 μM, respectively), assessed using Fura-2 AM. The PAR1 agonist completely desensitized responses to thrombin, indicating that thrombin stimulates neurons through PAR1.

Injection of TF-NH2 into the rat paw stimulated a marked and sustained oedema. An NK1R antagonist and ablation of sensory nerves with capsaicin inhibited oedema by 44% at 1 h and completely by 5 h.

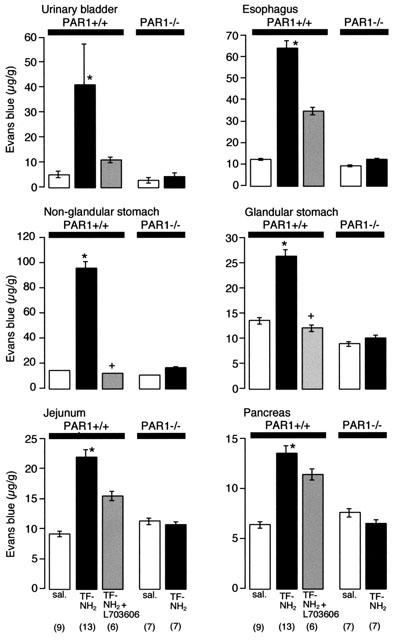

In wild-type but not PAR1−/− mice, TF-NH2 stimulated Evans blue extravasation in the bladder, oesophagus, stomach, intestine and pancreas by 2–8 fold. Extravasation in the bladder, oesophagus and stomach was abolished by an NK1R antagonist.

Thus, thrombin cleaves PAR1 on primary spinal afferent neurons to release SP, which activates the NK1R on endothelial cells to stimulate gap formation, extravasation of plasma proteins, and oedema. In intact tissues, neurogenic mechanisms are predominantly responsible for PAR1-induced oedema.

Keywords: Thrombin, proteinase-activated receptor 1, neurogenic inflammation, sensory nerves, substance P, neurokinin receptors, oedema

Introduction

Thrombin, which is generated in the circulation during activation of the coagulation cascade, plays a major role in inflammation and repair of injured tissues (reviewed in Cirino et al., 2000; Cocks & Moffatt, 2000; Dery et al., 1998; Grand et al., 1996). The proinflammatory effects of thrombin include stimulation of plasma extravasation and oedema, increased expression of endothelial adhesion molecules that induce leukocyte adhesion and infiltration, release of proinflammatory cytokines by endothelial cells, and mast cell degranulation. Thrombin also stimulates platelet aggregation, and proliferation of endothelial cells, fibroblasts, myocytes and astrocytes, and can protect neurons and astrocytes from stress, all of which contribute to repair. These effects of thrombin are mediated by a family of proteinase-activated receptors (PARs) (Dery et al., 1998). Thrombin cleaves PAR1, PAR3 and PAR4 within N-terminal extracellular domains to expose tethered ligand domains that bind to and activate the cleaved receptors.

PAR1, which mediates most of the known proinflammatory actions of thrombin, is expressed by platelets, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, mast cells, neurons and astrocytes (see Dery et al., 1998). Administration of thrombin and selective agonists of PAR1 to intact animals causes changes in vascular tone (Damiano et al., 1996), stimulates plasma extravasation and oedema (Cirino et al., 1996; Vergnolle et al., 1999), and promotes infiltration of inflammatory cells (Nishino et al., 1993). However, the cell types that mediate the proinflammatory effects of thrombin in intact tissues are not known. The increased vascular permeability that accompanies trauma and inflammation will permit extravasation of thrombin from the circulation into tissues, where it may regulate multiple cell types. Thus, the proinflammatory effects of thrombin in vivo may be mediated by several receptors on many different types of cells.

Many proinflammatory and noxious stimuli trigger inflammation by stimulating the release of neuropeptides such as substance P (SP) from the peripheral endings of primary spinal afferent neurons in multiple tissues (see Otsuka & Yoshioka, 1993). SP interacts with the neurokinin 1 (NKIR) on endothelial cells of post-capillary venules to cause gap formation and plasma extravasation, proliferation, and to promote leukocyte adhesion and infiltration. The same stimuli also cause release of SP from the central projections of primary spinal afferent neurons, where SP interacts with the NK1R on spinal neurons to transmit pain.

We have recently reported that agonists of another protease receptor, PAR2, induce inflammation by a neurogenic mechanism (Steinhoff et al., 2000). We hypothesized that proteases such as tryptase released from mast cells in the vicinity of sensory nerves can cleave PAR2 on nerve fibres to stimulate release of SP, which then interacts with the NK1R to induce plasma extravasation and oedema. This observation that proteases can signal to sensory nerves through specific receptors, together with the similar proinflammatory effects of thrombin and SP, led us to hypothesize further that thrombin, acting through PAR1, can also induce inflammation in intact tissues by a neurogenic mechanism involving release of SP and activation of the NK1R. Our aims were to (a) examine expression of PAR1 by primary spinal afferent neurons; (b) determine whether thrombin directly signals to these neurons by cleaving PAR1; (c) investigate whether the effects of PAR1 agonists on oedema and plasma extravasation are mediated by a neurogenic mechanism that involves release of SP and activation of the NK1R; and (d) confirm that the widespread effects of PAR1 agonists on extravasation of plasma proteins require activation of PAR1 and the NK1R by using knockout mice and receptor antagonists.

Methods

PAR 1 agonists

Rat thrombin was from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Analogues of the tethered ligand domain of PAR1, TFLLR-NH2 or TFLLRNDK-NH2 (TF-NH2) and AF (PF)RChaCitY-NH2 (AF-NH2), which selectively activate PAR1 (Hollenberg et al., 1997; Kawabata et al., 1999), were synthesized by solid phase methods, purified by high pressure liquid chromatography, and analysed by mass spectrometry and amino acid analysis. The scrambled peptide FSLLR-NH2 (FS-NH2), which does not activate PAR1, was used as a control.

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley or Wistar rats (175–250 g), and male and female PAR1 knockout mice and wild type animals in the same genetic background (C57B16, 20–35 g) were used. All procedures were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Animals were given free access to food and water.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

For immunohistochemistry, rat dorsal root ganglia (DRG, L5) were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin overnight and embedded in paraffin. Sections were dewaxed, hydrated, microwaved in Target buffer (DAKO, Carpenteria, CA, U.S.A.), washed in PBS and placed in 3.0% H2O2 for 10 min. Tissues were incubated with normal blocking serum (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.) for 10 min, and rinsed in PBS. Sections were incubated sequentially with a polyclonal PAR1 antibody (Thr-C raised in rabbits to the tethered ligand domain of rat PAR1, ↓ SFLLRN, ↓ thrombin cleavage site; 1 μg ml−1, Cheung et al., 1999) or an antibody to the neuronal marker NeuN (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, U.S.A.; 2.5 μg ml−1), followed by biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1 μg ml−1), and avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase complex reagent (ABC, Vector Labs), each for 30 min at room temperature, with intervening washes. Slides were treated 2×5 min with the chromogen 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Biomeda, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.), rinsed, counter-stained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, cleared in xylene and coverslipped. For immunofluorescence, rats were transcardially-perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 100 mM PBS, pH 7.4 and DRG (L1–L6) were immersion fixed for 24 h at 4°C. Cultured DRG were fixed in paraformaldehyde for 20 min at 4°C. Sections were incubated in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 30 min, and cultures were incubated with PBS containing 5% normal goat serum and 0.1% saponin for 30 min. Sections and cultures were incubated with primary antibodies in PBS with 2% normal goat serum and detergent for 24–48 h at 4°C. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse PAR1 antibody 61-1 (raised to residues 29–43 human PAR1; 1 : 100–200) (Norton et al., 1993); rabbit PAR1 antibody 4274 (raised to the residues 1–42 of human PAR1; 1 : 100); mouse antibody to the neuronal marker PGP9.5 (Accurate Chemicals, Westbury, NY, U.S.A., 1 : 100); mouse antibody to calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP; Dr J.H. Walsh, UCLA, 1 : 20,000). Both PAR1 antibodies gave similar results. Slides were washed and incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate or Texas Red (Cappel Research Products, Durham, NC, 1 : 200) for 2 h. Controls included pre-absorption of the primary antibodies with the receptor fragments that were used for immunization (1–10 μM, 24 h, 4°C) and replacement of the primary antibody with non-immune serum.

In situ hybridization

Paraffin sections of rat DRG were dewaxed, hydrated, incubated in 3% H2O2 for 10 min, and processed for In situ hybridization (Damiano et al., 1999; Festoff et al., 2000). Sections were placed in Universal Buffer (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL, U.S.A.), digested with pepsin for 10 min at 42°C, washed and dehydrated in 100% ethanol for 1 min. Biotinylated probes to PAR1 (5′-TTC ATT TTT CTC CTC CTC CTC CTC ATC C) and a poly d(T) oligoprobe (to label all mRNAs) were from Research Genetics. Probes (1.0 μg ml−1 in hybridization buffer, Biomeda) were heated for 5 min at 103°C, cooled to 42°C, and hybridized with tissues at 42°C for 2 h. Sections were placed into a low stringency wash (2×SSC) for 5 min at 42°C and then into a high stringency wash (0.1×SSC) for 5 min at 42°C. Slides were washed in PBS and then the ABC was placed on the tissues for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were washed, placed in DAB, briefly stained with hematoxylin and dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and coverslipped. Controls included the omission of the probe, use of a biotinylated probe specific to lac Z operon mRNA; and RNAse pre-digestion of tissues (40 μg ml−1 RNAse, Sigma, 2 h at 42°C).

Northern blotting and PCR

The plasmid pSPORT 1 containing full-length rat PAR1 cDNA (Dr Runge, Galveston, TX, U.S.A.) was digested with StuI and NcoI (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany) to obtain a 1.5 kb cDNA. cDNAs to PAR1 and GAPDH were labelled with 32P using a Redi Prime II kit (Amersham, U.K.). Total RNA was prepared from DRG (L1–L6) from two rats and from human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, positive control) using Trizol (Gibco–BRL, Grand Island, NY, U.S.A.). Total RNA (10 μg lane) was separated on a 1% formaldehyde-agarose gel and transferred to Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (Amersham). Membranes were prehybridized for 1 h with Rapid-Hyb buffer (Amersham) and hybridized with probe in the same buffer for 4 h at 68°C. Membranes were washed in 2×SSC, 3×20 min; 2×SSC/1% SDS, 64°C; 0.2×SSC/0.1% SDS, 2×20 min, 64°C. Membranes were apposed to Hyperfilm (Kodak) for 3 days (PAR1) or 1 day (GAPDH) at −70°C.

Enzymatic dispersion of DRG neurones

Rat DRG neurones were enzymatically dispersed and cultured (Steinhoff et al., 2000). DRG (T13–S2) were placed in cold Dulbecco's modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM), trimmed of fat and connective tissue, and minced. DRG were incubated in DMEM containing 0.5 mg ml−1 trypsin, 1 mg ml−1 collagenase and 0.1 mg ml−1 DNAse I (Sigma) for 45–60 min at 37°C. Soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma) sufficient to neutralize twice the amount of trypsin in the medium was added and the suspension was centrifuged at 1000 r.p.m. for 1 min. Neurones in the pellet were suspended in DMEM containing 10% foetal bovine serum, 5 ng ml−1 nerve growth factor (Gibco–BRL, Bethesda, MD, U.S.A.), 2 mM glutamine, 1 mg ml−1 penicillin/streptomycin and DNAse I (Sigma), and plated on glass coverslips coated with Matrigel (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA, U.S.A.). Neurones were cultured for 3–5 days before use.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i

Neurones were incubated in Hanks' balanced salt solution, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 containing 5 μM Fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.) for 1 h at 37°C. Coverslips were washed, mounted in a chamber (1 ml) on a Zeiss 100 TV inverted microscope (Zeiss, New York, NY, U.S.A.), and observed using a Zeiss 40×Fluar objective. Fluorescence in the soma was measured at 344 and 380 nm excitation and 520 nm emission using a video microscopy system (RatioVision, Atto Instruments, Rockville, MD, U.S.A.) (Steinhoff et al., 2000). The 344/380 nm emission ratio was measured to allow determination of [Ca2+]i. Agonists were added directly to the bath in a volume of 10 μl. Cells were exposed to a single concentration of agonists for concentration response analyses, or repeatedly challenged to assess desensitization.

Measurement of paw inflammation

Basal paw volume was measured using a hydroplethysmometer (Ugo Basile, Milan, Italy) (Vergnolle et al., 1999; Steinhoff et al., 2000). Rats were lightly anaesthetized with Halothane, and thrombin (5U), TF-NH2 or SF-NH2 (100 μg) in 100 μl physiological saline were injected in a subplantar location. Paw volume was then measured hourly for 6 h, and paw myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was measured after 6 h (Vergnolle et al., 1999; Steinhoff et al., 2000). To evaluate the role of SP and the NK1R, animals received the NK1R antagonist SR140333 (Sanofi-Recherche, Montpellier, France, 0.162 mg kg−1 intravenously and also subcutaneously) 5 min before PAR1 agonists. This dose has been shown to antagonize the NK1R in rats for 5 h (Wallace et al., 1998). Animals also received subcutaneous hourly injection of SR140333 (0.162 mg kg−1) for 6 h. To evaluate the role of sensory nerves, animals were treated with the neurotoxin capsaicin (Novabiochem Co., San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) to ablate C-fibres (McCafferty et al., 1997). Under Halothane anaesthesia, animals were injected subcutaneously with three doses of capsaicin (25, 50 and 50 mg kg−1, total dose 125 mg.kg−1, dissolved in 10% ethanol, 10% Tween, 80% physiological saline) over 32 h (at 0, 8 and 32 h). Animals were used 10 days after the final injection. The effectiveness of the capsaicin treatment was tested by instillation of 0.1 mg ml−1 capsaicin (in saline) into the eye. Wiping movements were counted. Control animals were treated with vehicle.

Measurement of plasma extravasation

Mice (PAR1+/+ and PAR1−/−) were anaesthetized with isofluorane, and saline or TF-NH2 (3 μmol kg−1 in 25 μl physiological saline) was injected into the lateral tail vein. Evans blue (33.3 mg kg−1 in 50 μl saline) was co-injected with the peptide. Mice were perfused transcardially at 10 min after administration of TF-NH2 with physiological saline containing 20 u ml−1 heparin at a pressure of 80–100 mmHg for 2–3 min. Excised tissues were incubated in 1 ml of formamide for 48 h, and Evans blue content was measured spectrophotometrically at 650 nm and expressed as μg g−1 wet weight of the tissue. To determine the role of the NK1R in TF-NH2 induced extravasation, mice were treated the NK1R antagonist L-703,606 RBI (RBI, Natick, MA, U.S.A., 2 mg kg−1 iv in 25 μl saline) 10 min before administration of TF-NH2 (Brokaw & White, 1994).

Statistical analyses

Results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean. Comparisons between groups were assessed using a two-sided Student's t-test with Bonferroni correction (two groups) or a two-way analysis of variance and Student–Newman–Kuels test (multiple groups). P⩽0.05 was considered significant.

Results

PAR1 is expressed by primary spinal afferent neurons

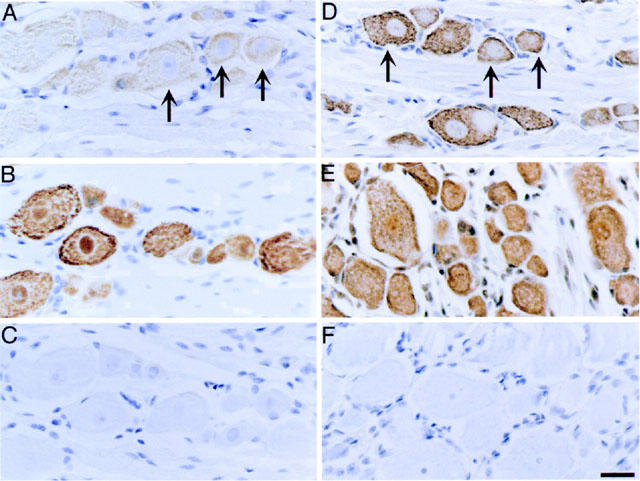

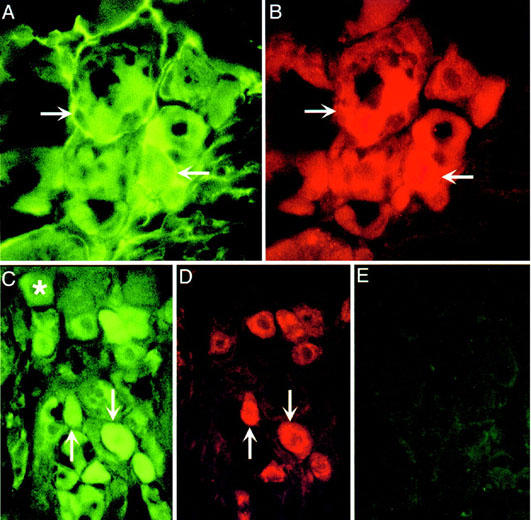

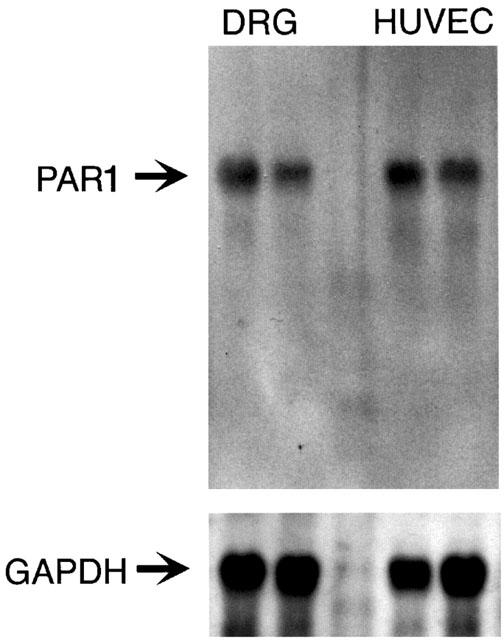

To determine whether primary spinal afferent neurons express PAR1, we localized PAR1 in sections of rat DRG by immunohistochemistry and In situ hybridization. PAR1 immunoreactivity (Figure 1A) and mRNA (Figure 1D) were detected in a large proportion of large (>20 μm diameter) and small (<20 μm diameter) neurons. Analysis by immunofluorescence permitted examination of the subcellular distribution of immunoreactive PAR1 and simultaneous localization of PAR1 with the neuronal marker PGP9.5 and CGRP, which is found in small diameter neurons. PAR1 immunoreactivity was observed at the plasma membrane and in intracellular locations of the neuronal soma (Figure 2A,C) and in fibres (not shown). Most small neurons that contained immunoreactive PAR1 also contained immunoreactive CGRP (Figure 2C,D). Specificity of the staining was confirmed by preabsorption of the primary antibodies to PAR1 (Figure 2E) or replacement with non-immune serum (Figure 1C), which abolished staining. Specificity of the In situ hybridization was verified by preincubation of tissues with RNAse (not shown) or by use of a probe to the lac Z operon, which failed to hybridize (Figure 1F). To confirm PAR1 expression in primary spinal afferent neurons and to determine the relative level of PAR1 expression, we analysed rat DRG by Northern hybridization. A primary transcript of PAR1 of 5.1 kb was detected in DRG at comparable levels to expression in HUVECs, which highly express PAR1 (Figure 3). Thus, primary spinal afferent neurons in the DRG express PAR1 protein and mRNA.

Figure 1.

Localization of PAR1 in rat DRG. Rat DRG (L5) were processed for immunohistochemistry (A–C) and in situ hybridization (D–F). Immunoreactive PAR1 (A) and PAR1 mRNA (D) was detected in both small and large diameter neurons (arrows). Immunoreactive NeuN (B) was detected in all neurons, and poly d(T) probe (D) identified all cells, and were used as positive controls. Non-immune serum (C) and a probe to lac Z operon (F) were used as negative controls. Scale bar=25 μm.

Figure 2.

Localization of PAR1 in rat DRG. Rat DRG were processed for immunofluorescence to localize PAR1 (A,C), PGP9.5 (B) or CGRP (D). A, B and C, D are the same sections. (E) is a control in which the PAR1 antibody was preabsorbed with the receptor fragment that was used for immunization. Arrows indicate colocalization of PAR1, PGP9.5 and CGRP in the same neurons. *Indicates PAR1 neurons that do not contain CGRP.

Figure 3.

Northern hybridization for PAR1 in rat DRG and HUVECs. Total RNA (10 μg/lane) was hybridized with cDNA probes to rat PAR1 or GAPDH.

Thrombin signals to primary spinal afferent neurons through PAR1

We studied rat primary spinal afferent neurons in short term culture to obtain functional evidence that thrombin directly signals to these neurons through PAR1. Immunoreactive PAR1 was detected at the plasma membrane of the soma and neurites (not shown). Expression by neurons was confirmed by simultaneous localization of PAR1 with the neuronal marker PGP9.5 and with CGRP (not shown). Thus, primary spinal afferent neurons in short term culture maintain expression of PAR1.

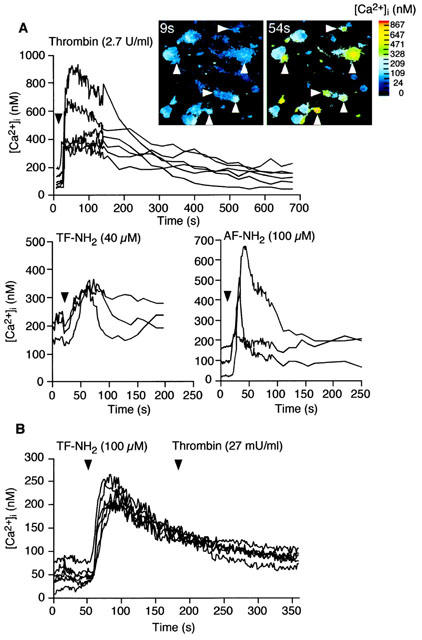

We measured Ca2+ responses in individual cultured neurons to provide functional evidence that PAR1 agonists can directly signal to DRG neurons. Thrombin (2.7 u ml−1) and the PAR1-selective agonists TF-NH2 (40 μM) and AF-NH2 (100 μM) stimulated a prompt increase in [Ca2+]i that was maximal after ∼50 s and which declined to basal values by 200 s (Figure 4A). In contrast, FS-NH2 (100 μM), which does not activate PAR1, had no effect on [Ca2+]i.

Figure 4.

PAR1 mediated Ca2+ mobilization in rat primary spinal afferent neurons in culture. (A) Effects of the PAR1 agonists thrombin (2.7 u ml−1), TF-NH2 (40 μM) and AF-NH2 (100 μM) or FS-NH2 (100 μM), which does not activate PAR1, on [Ca2+]i. Each line shows [Ca2+]i in the soma of a single neuron. The inset shows pseudocolour images of the neurons (arrows) that responded to thrombin. (B) Desensitization of PAR1 mediated Ca2+ mobilization. Exposure of neurons to TF-NH2 (40 μM for 2 min) abolished subsequent responses to thrombin (27 mu ml−1, without an intervening wash).

To verify that thrombin signals to DRG neurons by cleaving PAR1, rather than PAR3 or PAR4, which are also thrombin receptors, we determined the ability of specific agonists of PAR1 to desensitize responses to thrombin. Exposure of DRG neurons to maximal concentrations of TF-NH2 (100 μM) for 2 min abolished subsequent responses to thrombin (Figure 4B). Thus, PAR1 agonists desensitize responses to thrombin, suggesting that PAR1 mediates thrombin-induced Ca2+ mobilization in DRG neurones.

PAR1 agonists stimulated concentration-dependent increases in [Ca2+]i (not shown) and in the proportions of neurones in which we were able to detect a response (Figure 5). The basal [Ca2+]i was 164.6±14.3 nM (mean±s.e.mean, n=42 neurons). The maximal increase in [Ca2+]i above basal was detected in response to 2.7 u ml−1 thrombin (peak 440.7±73.4 nM, n=7 neurones), 10 μM TF-NH2 (196.5± 20.4 nM, n=25) and 100 μM AF-NH2 (125.5±21.8 nM, n=11) when 50–80% of identified neurones responded. The potencies (EC50s) of agonists were: thrombin 23.9 mu ml−1, TF-NH2 1.9 μM, and AF-NH2 1.6 μM. Thus, thrombin and selective agonists of PAR1 directly signal to spinal afferent neurones to mobilize intracellular Ca2+.

Figure 5.

PAR1 mediated Ca2+ mobilization in rat primary spinal afferent neurons in culture. Concentration/response analyses for thrombin and TF-NH2. Results are expressed as the percentage of all observed neurons that responded to agonists with a detectable increase in [Ca2+]i. Numbers indicate the responsive neurons.

PAR1 agonists induce oedema by a neurogenic mechanism

Intraplantar injections of PAR1 agonists induce oedema. To evaluate the role of SP released from sensory nerves in PAR1-induced inflammation of the paw, we used NK1R antagonists and the neurotoxin capsaicin.

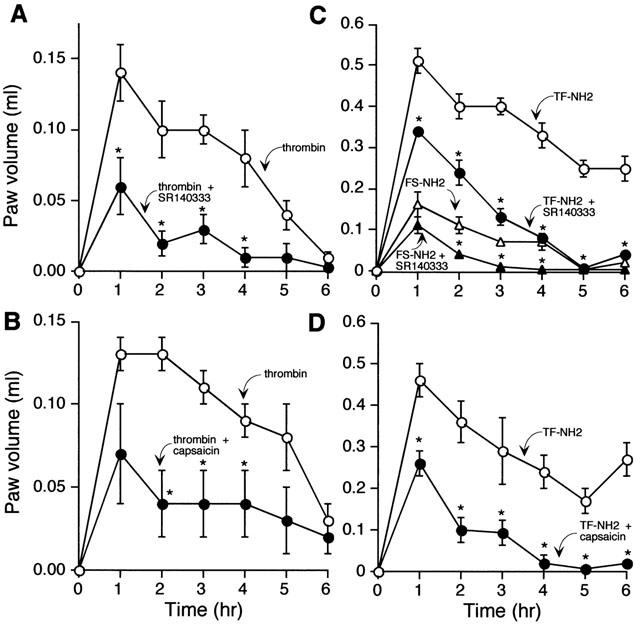

In animals treated with the vehicle for the NK1R antagonist SR140333, intraplantar injection of 5 u thrombin or 100 μg TF-NH2 caused an increase in paw volume that was maximal at 1 h and sustained for at least 6 h (Figure 6A–D). At the doses used, the response to TF-NH2 was ∼3-fold greater than that to thrombin (thrombin 0.14±0.02, TF-NH2 0.51±0.03 ml over basal at 1 h). Intraplantar FS-NH2, which does not activate PAR1, also caused oedema (Figure 6C), whereas injection of saline vehicle had minimal effect (not shown). FS-NH2 probably induces oedema by a mechanism that does not involve activation of PARs, since this scrambled peptides does not activate PAR1. The NK1R antagonist SR140333 strongly inhibited thrombin and TF-NH2 induced paw oedema, by 57 and 33%, respectively, at 1 h, and completely by 4–5 h (Figure 6A,C). SR140333 slightly reduced the increase in paw volume to FS-NH2. Thus, SP and the NK1R mediate, at least in part, the oedema response to thrombin and TF-NH2.

Figure 6.

Effects of PAR1 agonists on oedema of the rat paw. Thrombin (5 U) (A,B) and TF-NH2 or the inactive analogue FS-NH2 (C,D) (both 100 μg) were injected into the paw and volume was measured hourly for 6 h. Results are expressed as increase in paw volume over basal. Thrombin and TF-NH2 stimulated oedema, which was inhibited by the NK1R antagonist SR140333 (A,C) and by ablation of sensory nerves with capsaicin (B,D). *P⩽0.05 compared to animals receiving TF-NH2 or FS-NH2 alone. n=6 animals per group.

In animals treated with the vehicle for capsaicin (controls), thrombin and TF-NH2 stimulated a large and sustained increase in paw volume (thrombin 0.13±0.01, TF-NH2 0.46±0.04 ml at 1 h) (Figure 6B,D). Ablation of primary spinal afferent neurons with capsaicin markedly inhibited thrombin and TF-NH2 induced oedema by 44 and 50%, respectively, at 1 h and completely by 4–5 h. Thus, PAR1-induced paw oedema is mediated by the release of SP from primary spinal afferent neurons, and subsequent activation of the NK1R.

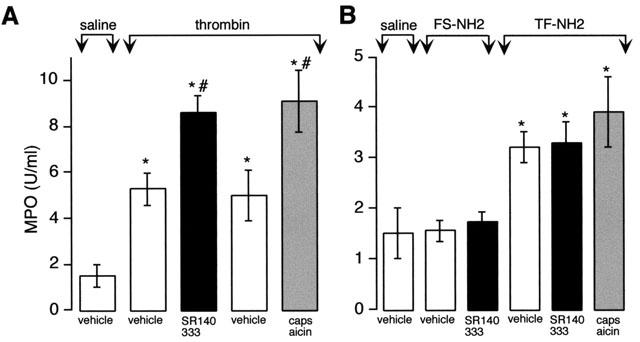

To determine whether PAR1-induced granulocyte infiltration is mediated by release of SP from primary afferent neurons and activation of the NK1R, we quantified infiltration by measurement of MPO activity in the paw at 6 h. Intraplantar injection of thrombin and TF-NH2 but not FS-NH2 stimulated MPO activity in the paw by 2–3-fold over the response to saline (Figure 7A,B). SR140333 and capsaicin enhanced the stimulation of paw MPO activity in response to thrombin, but not TF-NH2. Thus, thrombin-induced granulocyte infiltration into the paw may be down-regulated by a neurogenic mechanism, whereas TF-NH2 induced granulocyte infiltration is not mediated by the NK1R or sensory nerves. Basal MPO activity was unaffected by SR140333 (1.06±0.5 u mg−1 in SR140333-treated rats, 1.21±0.11 u mg−1 in vehicle-treated rats). Thus, the NK1R does not modulate MPO activity under basal conditions.

Figure 7.

Effects of PAR1 agonists on granulocyte infiltration to the rat paw. Thrombin (5 μu) (A) and TF-NH2 or the inactive analogue FS-NH2 (B) (both 100 μg) were injected into the paw and MPO activity in the paw was measured after 6 h. Thrombin and TF-NH2 but not FS-NH2 increased MPO activity. SR140333 and capsaicin exacerbated the response to thrombin but not TF-NH2. *P⩽0.05 compared to saline control; #P⩽0.05 compared to corresponding vehicle control. n=6 animals per group.

PAR1 agonists induce widespread plasma extravasation by a neurogenic mechanism

Oedema requires the formation of gaps between endothelial cells of post-capillary venules and subsequent extravasation of plasma into tissues. We quantified extravasation of plasma proteins using Evans blue, which permitted simultaneous evaluation of PAR1-mediated plasma extravasation in multiple tissues. Although TF-NH2 selectively activates PAR1, such peptides could in theory activate other receptors. Therefore, we compared the effects of TF-NH2 on plasma extravasation in wild type and PAR1 knockout mice.

In wild type mice, TF-NH2 (3 μmol kg−1) stimulated Evans blue extravasation in the urinary bladder, oesophagus, stomach, jejunum and pancreas by 2–8 fold over the basal response to saline vehicle (Figure 8). TF-NH2 had the largest effect on Evans blue extravasation in the urinary bladder, oesophagus and non-glandular stomach. Pretreatment with the NK1R antagonist L-703,606 significantly inhibited TF-NH2 induced extravasation of Evans blue in the non-glandular and glandular region of the stomach, and reduced somewhat the extent of extravasation in the urinary bladder and oesophagus but did not achieve statistical significance in these tissues (Figure 8). The NK1R antagonist was less effective in the jejunum and pancreas (Figure 8). Thus, TF-NH2 stimulates extravasation of plasma proteins in selected tissues by a neurogenic mechanism that requires release of SP and activation of the NK1R.

Figure 8.

PAR1-induced extravasation of Evans blue in PAR1+/+ and PAR1−/− mice. Mice were injected with TF-NH2 (3 μmol kg−1, iv) and Evans blue extravasation was measured 10 min later. TF-NH2 stimulated extravasation in PAR1+/+ but not in PAR1−/− mice. Administration of the NK1R antagonist L-703,606 inhibited TF-NH2-induced plasma extravasation in many tissues. *Significant effect of strain and peptide treatment, ⩽0.05, two-way analysis of variance. + Significantly different from the TF-NH2 group, P⩽0.05, t-test (n).

In PAR1−/− mice, in marked contrast to PAR1+/+ animals, TF-NH2 did not stimulate extravasation of Evans blue in any tissues above basal values measured after saline vehicle (Figure 8). Thus, TF-NH2 stimulates extravasation of plasma proteins by activating PAR1.

Discussion

Our results show that PAR1 is expressed by a large proportion of primary spinal afferent neurons. Thrombin directly signals to these neurons in culture by cleaving PAR1. Administration of PAR1 agonists induces plasma extravasation and consequent oedema, which are blocked by ablation of sensory nerves and administration of NK1R antagonists. Together, these results support the hypothesis that thrombin cleaves PAR1 on sensory nerves to stimulate release of SP, which interacts with the NK1R to induce extravasation of plasma proteins and oedema. Our findings that ablation of sensory nerves and antagonism of the NK1R inhibits PAR1-induced paw oedema by almost 50% at 1 h and completely by 5 h, together with the observation that NK1R antagonists abolish PAR1-stimulated plasma extravasation, indicate that neurogenic mechanisms are predominantly responsible for thrombin-induced oedema in the intact animal. To our knowledge, this is the first report that thrombin can trigger neurogenic inflammation.

Proteases signal to neurons through specific receptors

Several observations indicate that PAR1 is expressed by primary spinal afferent neurons. Firstly, we detected PAR1 immunoreactivity and mRNA in DRG neurons in tissue sections and in short-term culture using immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization. Although PAR1 was expressed in some large diameter neurons, many PAR1 positive neurons were of small diameter (<20 μm) and also contained CGRP. Thus, PAR1 is expressed by neurons that could participate in neurogenic inflammation and nociception. Northern hybridization confirmed expression of PAR1 and indicated that DRG expressed PAR1 mRNA at similar levels to endothelial cells, a rich source of this receptor. Secondly, thrombin and peptide agonists of PAR1 stimulated Ca2+ mobilization in cultured neurons, indicating expression of functional receptor. Since peptides corresponding to the tethered ligand domain of PAR1 (SFLLR) can also activate PAR2, we challenged neurons with analogues of this sequence (TF-NH2 and AF-NH2) that are selective for PAR1. Although PAR3 and PAR4 could also mediate the effects of thrombin, the finding that PAR1 agonists strongly desensitized responses to thrombin suggests that PAR1 mediates thrombin-stimulated Ca2+ mobilization. Thrombin, TF-NH2 and AF-NH2 stimulated Ca2+ mobilization in cultured neurons with potencies similar to those observed in cell lines expressing PAR1, which also suggests that PAR1 mediates signalling in neurons. Maximally effective concentrations of TF-NH2 and AF-NH2 stimulated detectable responses in a majority (70–80%) of all studied neurons, indicating that most DRG neurons express functional PAR1. Maximal concentrations of thrombin stimulated Ca2+ mobilization in fewer (∼50%) of DRG neurons. This difference may be related to the production of thrombin inhibitors, such as protease nexin 1, that are known to be expressed in the nervous system (Festoff et al., 1996). Finally, our observations in vivo support the expression of PAR1 in nociceptive neurons, since PAR1-stimulated plasma extravasation and oedema were markedly attenuated by ablation of sensory nerves, and by antagonism of SP, which derives from primary spinal afferent neurons.

Other reports of PAR1 in the nervous system support our results. PAR1 is expressed in rat DRG, where it is particularly localized to neurites of cultured DRG neurons (Gill et al., 1998). PAR1 is also expressed in other components of the peripheral and central nervous systems. Both excitatory and inhibitory neurons of the myenteric plexus from the guinea-pig small intestine express PAR1 (Corvera et al., 1999). In the rat brain PAR1 is expressed by neurons of the neo-cortex, cingulate cortex, subsets of thalamic and hypothalamic nuclei, and discrete layers of the hippocampus, cerebellum and olfactory bulb, as well as by astroglia (Weinstein et al., 1995). Functional studies also support the expression of PAR1 in neurons and astrocytes. Thus, PAR1 agonists cause retraction of neurites in DRG (Gill et al., 1998) and neuroblastoma cells (Gurwitz & Cunningham, 1988), induce Ca2+ mobilization by enteric (Corvera et al., 1999) and hippocampal neurons (Striggow et al., 2000), and can protect neuroglia cells in culture and neurons in vivo from hypoglycemia and oxidative stress (Striggow et al., 2000; Vaughan et al., 1995).

Proteases other than thrombin can also signal to the nervous system through PARs. Like PAR1, PAR2 is also expressed by a large proportion of primary spinal afferent neurons containing CGRP and SP (Steinhoff et al., 2000). Moreover, most myenteric neurons in the guinea-pig small intestine express PAR2 (Corvera et al., 1999), and PAR2 is expressed by neurons in the rat brain (Smith-Swintosky et al., 1997; Jenkins et al., 2000). Thus, both thrombin, trypsin and tryptase, possible endogenous agonists of PAR1 and PAR2, may directly signal to peripheral and central neurons through specific PARs.

Proteases induce neurogenic inflammation

We found that agonists of PAR1 caused extravasation of plasma proteins in the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and urinary bladder of the mouse, and paw oedema in rats. The effects of TF-NH2 are due to activation of PAR1 rather than another receptor since they were not observed in PAR1−/− mice and because TF-NH2 does not activate PAR2, PAR3 or PAR4. Plasma extravasation resulted in a marked and long lasting oedema in the rat paw. PAR1-induced oedema of the paw was markedly inhibited by ablation of sensory nerves, and is thus mediated principally by a neurogenic mechanism. Additional support for this conclusion derives from the finding that both paw oedema and plasma extravasation were strongly inhibited by antagonists of the NK1R, and are thus mediated by SP released from the peripheral projections of primary spinal afferent neurons. Two different NK1R antagonists inhibited PAR1-induced plasma extravasation and oedema, which confirms mediation by SP and the NK1R. SP from sensory nerves interacts with the NK1R on endothelial cells to induced gap formation and extravasation of plasma proteins, a hall mark of neurogenic inflammation (Bowden et al., 1994). Additionally, SP can trigger the degranulation of mast cells and consequent release of other mediators of inflammation (Otsuka & Yoshioka, 1993). In a similar manner we have shown that agonists of PAR2 also induce neurogenic inflammation by stimulating the release of SP and CGRP from primary spinal afferent neurons (Steinhoff et al., 2000). We found that the scrambled peptide FS-NH2 also caused some oedema of the paw. This peptide does not activate PAR1, and the response was minimally affected by an NK1R antagonist, and is thus not neurogenically mediated. One possibility is that high concentrations of peptides induce degranulation of mast cells and consequent oedema, since scrambled sequences of PAR2 agonist peptides also cause oedema by a mast cell-dependent process (Steinhoff et al., 2000).

We propose that proteases derived from the circulation or from inflammatory cells can stimulate neurogenic inflammation in many peripheral tissues. Thrombin, which is generated within the circulation during coagulation, may escape from the vasculature as a result of the increased vascular permeability that accompanies injury and inflammation. Thrombin could cleave PAR1 on the peripheral projections of sensory nerves to stimulate release of SP, which would cause plasma extravasation and oedema by activating the NK1R on endothelial cells of post-capillary venules. In a similar manner, tryptase released from degranulated mast cells in the vicinity of sensory nerves may cleave PAR2 on sensory nerves to trigger the release of SP and CGRP, which also cause plasma extravasation and oedema (Steinhoff et al., 2000). Thus, several proteases can potentially signal to sensory nerves to trigger neurogenic inflammation.

Neurogenic mechanisms do not mediate all of the proinflammatory effects of PAR1 agonists. Although antagonism of the NK1R and ablation of sensory nerves strongly inhibited plasma extravasation and paw oedema, these responses were not abolished. Furthermore, thrombin and TF-NH2-stimulated infiltration of granulocytes into the rat paw were not prevented by ablation of sensory nerves or administration of NK1R antagonists. In a similar manner, PAR2-induced oedema is not completely abolished by disruption of sensory nerves, and agonists of PAR2 stimulate granulocyte infiltration by non-neurogenic mechanisms (Steinhoff et al., 2000). Thus, thrombin can cause inflammation by stimulating cells other than neurons. PAR1 is expressed on multiple cell types that participate inflammation, including mast cells (D'andrea et al., 2000), endothelial cells and fibroblasts (see Dery et al., 1998). PAR1 agonists can directly signal to endothelial cells to induce gap formation and macromolecule transmigration across monolayers of endothelial cells (Laposata et al., 1983; Lum et al., 1992), and stimulate the expression of chemoattractants (Colotta et al., 1994) and adhesion molecules (Moser et al., 1990; Sugama & Malik, 1992) that promote the adhesion and infiltration of granulocytes. Additionally, PAR1 agonists degranulate mast cells (Razin & Marx, 1984), and depletion of mast cells partially inhibits PAR1-induced oedema of the paw (Cirino et al., 1996; Vergnolle et al., 1999). PAR1 agonists also induce vasodilatation through release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells (Muramatsu et al., 1992), and trigger the proliferation of endothelial cells (Mirza et al., 1996) and fibroblasts (Chen et al., 1994).

Surprisingly, thrombin-stimulated infiltration of granulocytes into the paw was exacerbated by ablation of sensory nerves and administration of NK1R antagonists. In support of this result, PAR2-stimulated granulocyte infiltration is also increased by capsaicin (Steinhoff et al., 2000). These results suggest that mediators from sensory nerves can play an anti-inflammatory as well as a proinflammatory role. Capsaicin also exacerbates granulocyte infiltration in colitis, which supports the concept that sensory nerves can also protect against inflammation (Reinshagen et al., 1994; 1996). In the intestine CGRP mediates this protective effect (Reinshagen et al., 1998). The role of CGRP in the protective effect of PAR1 agonists remains to be determined.

In addition to plasma extravasation, other proinflammatory effects of PARs in intact tissues are mediated by the nervous system. PAR2-induced broncho-constriction in the intact guinea-pig is markedly inhibited by NK1R and NK2R antagonists, suggesting that PAR2 agonists stimulate release of tachykinins from sensory nerves in the airway (Ricciardolo et al., 2000). Application of PAR2 agonists to the serosa of the pig small intestine stimulates chloride secretion, which is inhibited by saxitoxin and thus depends on a functional innervation (Green et al., 2000). Whether other proinflammatory effects of thrombin are also mediated by neurogenic mechanisms remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants DK57850, DK43207 and DK39957 (NWB), the Canadian Medical Research Council (J.L. Wallace, M.D. Hollenberg), Astra-Zeneca (N. Vergnolle) and the R.W. Johnson Focussed Giving Program (N.W. Bunnett, J.L. Wallace, M.D. Hollenberg). We thank Antje Steinhoff, Barbara Haertlein, Gail Thompson, Michael Milewski, Patti Reiser, Norah Gumula and Brenda Hertzog for technical assistance, and COR Therapeutics for the PAR1 antibodies 61-1 and 4274.

Abbreviations

- AF-NH2

AF(PF)RChaCitY-NH2

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- DRG

dorsal root ganglia

- FS-NH2

FSLLR-NH2

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- NK1R

neurokinin 1 receptor

- PAR

proteinase-activated receptor

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- SP

substance P

- TF-NH2

TFLLR-NH2.

References

- BOWDEN J.J., GARLAND A.M., BALUK P., LEFEVRE P., GRADY E.F., VIGNA S.R., BUNNETT N.W., MCDONALD D.M. Direct observation of substance P-induced internalization of neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptors at sites of inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:8964–8968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROKAW J.J., WHITE G.W. Differential effects of phosphoramidon and captopril on NK1 receptor-mediated plasma extravasation in the rat trachea. Agents Actions. 1994;42:34–39. doi: 10.1007/BF02014297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Y.H., POUYSSEGUR J., COURTNEIDGE S.A., VAN OBBERGHEN-SCHILLING E. Activation of Src family kinase activity by the G protein-coupled thrombin receptor in growth-responsive fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:27372–27377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEUNG W.M., D'ANDREA M.R., ANDRADE-GORDON P., DAMIANO B.P. Altered vascular injury responses in mice deficient in protease-activated receptor-1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999;19:3014–3024. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.12.3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIRINO G., BUCCI M., CICALA C., NAPOLI C. Inflammation-coagulation network: are serine protease receptors the knot. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2000;21:170–172. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01469-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIRINO G., CICALA C., BUCCI M.R., SORRENTINO L., MARAGANORE J.M., STONE S.R. Thrombin functions as an inflammatory mediator through activation of its receptor. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:821–827. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COCKS T.M., MOFFATT J.D. Protease-activated receptors: sentries for inflammation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2000;21:103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLOTTA F., SCIACCA F.L., SIRONI M., LUINI W., RABIET M.J., MANTOVANI A. Expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 by monocytes and endothelial cells exposed to thrombin. Am. J. Pathol. 1994;144:975–985. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORVERA C.U., DERY O., MCCONALOGUE K., GAMP P., THOMA M., AL-ANI B., CAUGHEY G.H., HOLLENBERG M.D., BUNNETT N.W. Thrombin and mast cell tryptase regulate guinea-pig myenteric neurons through proteinase-activated receptors-1 and -2. J. Physiol. (Lond) 1999;517:741–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0741s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'ANDREA M.R., ROGAHN C.J., ANDRADE-GORDON P. Localization of protease-activated receptors-1 and -2 in human mast cells: indications for an amplified mast cell degranulation cascade. Biotech. Histochem. 2000;75:85–90. doi: 10.3109/10520290009064152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAMIANO B.P., CHEUNG W.M., MITCHELL J.A., FALOTICO R. Cardiovascular actions of thrombin receptor activation in vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;279:1365–1378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAMIANO B.P., D'ANDREA M.R., DE GARAVILLA L., CHEUNG W.M., ANDRADE-GORDON P. Increased expression of protease activated receptor-2 (PAR-2) in balloon-injured rat carotid artery. Thromb. Haemost. 1999;81:808–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DERY O., CORVERA C.U., STEINHOFF M., BUNNETT N.W. Proteinase-activated receptors: novel mechanisms of signaling by serine proteases. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:C1429–C1452. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.6.C1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FESTOFF B.W., D'ANDREA M.R., CITRON B.A., SALCEDO R.M., SMIRNOVA I.V., ANDRADE-GORDON P. Motor neuron cell death in wobbler mutant mice follows overexpression of the G-protein-coupled, protease-activated receptor for thrombin. Mol. Med. 2000;6:410–429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FESTOFF B.W., SMIRNOVA I.V., MA J., CITRON B.A. Thrombin, its receptor and protease nexin I, its potent serpin, in the nervous system. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 1996;22:267–271. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILL J.S., PITTS K., RUSNAK F.M., OWEN W.G., WINDEBANK A.J. Thrombin induced inhibition of neurite outgrowth from dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Res. 1998;797:321–327. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAND R.J., TURNELL A.S., GRABHAM P.W. Cellular consequences of thrombin-receptor activation. Biochem. J. 1996;313:353–368. doi: 10.1042/bj3130353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN B.T., BUNNETT N.W., KULKARNI-NARLA A., STEINHOFF M., BROWN D.R. Intestinal type 2 proteinase-activated receptors: expression in opioid-sensitive secretomotor neural circuits that mediate epithelial ion transport. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;295:410–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GURWITZ D., CUNNINGHAM D.D. Thrombin modulates and reverses neuroblastoma neurite outgrowth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:3440–3444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLENBERG M.D., SAIFEDDINE M., AL-ANI B., KAWABATA A. Proteinase-activated receptors: structural requirements for activity, receptor cross-reactivity, and receptor selectivity of receptor-activating peptides. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1997;75:832–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JENKINS A.L., CHINNI C., DE NIESE M.R., BLACKHART B., MACKIE E.J. Expression of protease-activated receptor-2 during embryonic development. Dev. Dyn. 2000;218:465–471. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(200007)218:3<465::AID-DVDY1013>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., SAIFEDDINE M., AL-ANI B., LEBLOND L., HOLLENBERG M.D. Evaluation of proteinase-activated receptor-1 (PAR1) agonists and antagonists using a cultured cell receptor desensitization assay: activation of PAR2 by PAR1-targeted ligands. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;288:358–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAPOSATA M., DOVNARSKY D.K., SHIN H.S. Thrombin-induced gap formation in confluent endothelial cell monolayers in vitro. Blood. 1983;62:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUM H., ASCHNER J.L., PHILLIPS P.G., FLETCHER P.W., MALIK A.B. Time course of thrombin-induced increase in endothelial permeability: relationship to Ca2+i and inositol polyphosphates [published erratum appears in Am. J. Physiol. (1992) 263: section L following table of contents] Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:L219–L225. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1992.263.2.L219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCAFFERTY D.M., WALLACE J.L., SHARKEY K.A. Effects of chemical sympathectomy and sensory nerve ablation on experimental colitis in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:G272–G280. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.2.G272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIRZA H., YATSULA V., BAHOU W.F. The proteinase activated receptor-2 (PAR-2) mediates mitogenic responses in human vascular endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:1705–1714. doi: 10.1172/JCI118597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOSER R., GROSCURTH P., FEHR J. Promotion of transendothelial neutrophil passage by human thrombin. J. Cell Sci. 1990;96:737–744. doi: 10.1242/jcs.96.4.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURAMATSU I., LANIYONU A., MOORE G.J., HOLLENBERG M.D. Vascular actions of thrombin receptor peptide. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1992;70:996–1003. doi: 10.1139/y92-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHINO A., SUZUKI M., OHTANI H., MOTOHASHI O., UMEZAWA K., NAGURA H., YOSHIMOTO T. Thrombin may contribute to the pathophysiology of central nervous system injury. J. Neurotrauma. 1993;10:167–179. doi: 10.1089/neu.1993.10.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORTON K.J., SCARBOROUGH R.M., KUTOK J.L., ESCOBEDO M.A., NANNIZZI L., COLLER B.S. Immunologic analysis of the cloned platelet thrombin receptor activation mechanism: evidence supporting receptor cleavage, release of the N-terminal peptide, and insertion of the tethered ligand into a protected environment. Blood. 1993;82:2125–2136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OTSUKA M., YOSHIOKA K. Neurotransmitter functions of mammalian tachykinins. Physiol. Rev. 1993;73:229–308. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAZIN E., MARX G. Thrombin-induced degranulation of cultured bone marrow-derived mast cells. J. Immunol. 1984;133:3282–3285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REINSHAGEN M., FLAMIG G., ERNST S., GEERLING I., WONG H., WALSH J.H., EYSSELEIN V.E., ADLER G. Calcitonin gene-related peptide mediates the protective effect of sensory nerves in a model of colonic injury. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;286:657–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REINSHAGEN M., PATEL A., SOTTILI M., FRENCH S., STERNINI C., EYSSELEIN V.E. Action of sensory neurons in an experimental at colitis model of injury and repair. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;270:G79–G86. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.270.1.G79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REINSHAGEN M., PATEL A., SOTTILI M., NAST C., DAVIS W., MUELLER K., EYSSELEIN V.E. Protective function of extrinsic sensory neurons in acute rabbit experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1208–1214. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICCIARDOLO F.L., STEINHOFF M., AMADESI S., GUERRINI R., TOGNETTO M., TREVISANI M., CREMINON C., BERTRAND C., BUNNETT N.W., FABBRI L.M., SALVADORI S., GEPPETTI P. Presence and bronchomotor activity of protease-activated receptor-2 in guinea pig airways. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000;161:1672–1680. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9907133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH-SWINTOSKY V., CHEO-ISAACS C., D'ANDREA M., SANTULLI R., DARROW A., ANDRADE-GORDON P. Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2) is present in the rat hippocampus and is associated with neurodegeneration. J. Neurochem. 1997;69:1890–1896. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69051890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINHOFF M., VERGNOLLE N., YOUNG S.H., TOGNETTO M., AMADESI S., ENNES H.S., TREVISANI M., HOLLENBERG M.D., WALLACE J.L., CAUGHEY G.H., MITCHELL S.E., WILLIAMS L.M., GEPPETTI P., MAYER E.A., BUNNETT N.W. Agonists of proteinase-activated receptor 2 induce inflammation by a neurogenic mechanism. Nat. Med. 2000;6:151–158. doi: 10.1038/72247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRIGGOW F., RIEK M., BREDER J., HENRICH-NOACK P., REYMANN K.G., REISER G. The protease thrombin is an endogenous mediator of hippocampal neuroprotection against ischemia at low concentrations but causes degeneration at high concentrations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:2264–2269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040552897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUGAMA Y., MALIK A.B. Thrombin receptor 14-amino acid peptide mediates endothelial hyperadhesivity and neutrophil adhesion by P-selectin-dependent mechanism. Circ. Res. 1992;71:1015–1019. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.4.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAUGHAN P.J., PIKE C.J., COTMAN C.W., CUNNINGHAM D.D. Thrombin receptor activation protects neurons and astrocytes from cell death produced by environmental insults. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:5389–5401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05389.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERGNOLLE N., HOLLENBERG M.D., WALLACE J.L. Pro- and anti-inflammatory actions of thrombin: a distinct role for proteinase-activated receptor-1 (PAR1) Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:1262–1268. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALLACE J.L., MCCAFFERTY D.M., SHARKEY K.A. Lack of beneficial effect of a tachykinin receptor antagonist in experimental colitis. Regul. Pept. 1998;73:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(97)01064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEINSTEIN J.R., GOLD S.J., CUNNINGHAM D.D., GALL C.M. Cellular localization of thrombin receptor mRNA in rat brain: expression by mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons and codistribution with prothrombin mRNA. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:2906–2919. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02906.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]