Abstract

In this study we examined the signalling events that regulate lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated induction of interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs).

LPS stimulated a time- and concentration-dependent increase in IRF-1 protein expression, an effect that was mimicked by the cytokine, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α.

LPS stimulated a rapid increase in nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) DNA-binding activity. Pre-incubation with the NFκB pathway inhibitors, N-α-tosyl-L-lysine chloromethyl ketone (TLCK) or pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC), or infection with adenovirus encoding IκBα, blocked both IRF-1 induction and NFκB DNA-binding activity.

LPS and TNFα also stimulated a rapid activation of gamma interferon activation site/gamma interferon activation factor (GAS/GAF) DNA-binding in HUVECs. Preincubation with the Janus kinase (JAK)-2 inhibitor, AG490 blocked LPS-stimulated IRF-1 induction but did not affect GAS/GAF DNA-binding.

Preincubation with TLCK, PDTC or infection with IκBα adenovirus abolished LPS-stimulated GAS/GAF DNA-binding.

Incubation of nuclear extracts with antibodies to RelA/p50 supershifted GAS/GAF DNA-binding demonstrating the involvement of NFκB isoforms in the formation of the GAS/GAF complex.

These studies show that NFκB plays an important role in the regulation of IRF-1 induction in HUVECs. This is in part due to the interaction of NFκB isoforms with the GAS/GAF complex either directly or via an intermediate protein.

Keywords: HUVEC, interferon regulatory factor-1, nuclear factor-κB, lipopolysaccharide

Introduction

Interferon-regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) is a 48 kDa protein transcription activator originally identified as a regulator of the interferon (IFN) system (Tanaka et al., 1993). IRF-1 is able to activate transcription of certain IFN-stimulated genes by binding to IFN-stimulated response elements (ISREs). The expression of IRF-1 is induced by viruses, IFNs, a number of cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, platelet-derived growth factor and colony-stimulating factor (Schaper et al., 1998). IRF-1 has been implicated in a number of cellular functions including apoptosis and tumour suppression (Schaper et al., 1998), and the loss of IRF-1 function may be a critical event in the development of human leukaemias (Willman et al., 1993; Harada et al., 1994). IRF-1 has also been implicated in the regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) induction and studies using mice lacking the IRF-1 gene have provided evidence to suggest that IRF-1 is indispensable for the induction of iNOS irrespective of the cytokine involved (Kamijo et al., 1994).

Two intracellular signalling pathways have been implicated in the regulation of IRF-1 induction. The promoter of the IRF-1 gene contains a number of binding elements including the gamma interferon activation site (GAS), which is a major downstream target for the Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/S TAT) signalling cascade (Shuai, 1994; Harada et al., 1994). The transcription factor, nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB), may also be involved by binding to specific sites within the IRF-1 promoter region (Harada et al., 1994; Kumar et al., 1997). Under resting conditions NFκB is associated with a cytoplasmic protein, inhibitory κB (IκB) and, following cell stimulation, dissociates from IκB and translocates to the nucleus. Dissociation of IκBα from NFκB is regulated by phosphorylation of IκB which is, in turn, regulated by isoforms of inhibitory κB kinase (IKK) (Didonato et al., 1996). LPS strongly activates this pathway in a number of different cell types primarily through activation of Toll-like receptor-4 (Yang et al., 1998; Chow et al., 1999).

Whilst the role of NFκB in the regulation of IRF-1 induction has been examined principally by study of the IRF-1 promoter using transfected cells, the function of this pathway in different cell types remains poorly characterized. For example, whilst LPS can strongly stimulate the IKK/NFκB pathway in RAW264.7 macrophages this does not result in strong activation of IRF-1 induction (Liu et al., 1999) suggesting cell-specific differences in the relative importance of the NFκB pathway in the regulation of IRF-1 induction. In addition, a number of previous studies have utilized LPS in combination with IFNγ (Martin et al., 1994; Hecker et al., 1996) which does not allow effective delineation of the intracellular signalling pathways involved.

In this study therefore, we sought to determine the role of NFκB in the regulation of IRF-1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). LPS and TNFα, which strongly activate NFκB, were found to be robust stimulants of IRF-1 induction, whilst inhibition of NFκB activation using the NFκB pathway inhibitors, pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC) and N-α-tosyl-L-lysine chloromethyl ketone (TLCK), or infection with adenovirus encoding the IκBα gene, abolished IRF-1 expression in response to LPS. HUVECs also responded to LPS and TNFα with a marked increase in GAS/GAF DNA-binding however, this was not associated with an increase in JAK/S TAT activation. Rather, GAS/GAF activity was also abolished by NFκB inhibitors or adenovirus-mediated IκBα expression. Furthermore, ‘super-shift' assays demonstrated that NFκB associated with a GAS/GAF DNA-binding complex. This indicates a crucial role for NFκB in the regulation of IRF-1 induction in HUVECs possibly through both GAS/GAF and NFκB DNA-binding. A preliminary account of these findings has been presented to the British Pharmacological Society (Liu et al., 2001).

Methods

Materials

Antibodies to the 48 kDa isoform of IRF-1 and the 37 kDa α-isoform of IκB were obtained from Insight Biotechnology (London, U.K.). LPS (Escherichia coli serotypes 0127:B8), PDTC and TLCK were purchased from Sigma Co. (Poole, U.K.). The consensus single-stranded GAS sequences: 5′-AGCCTGATTTCCCCGAAATGACGGC-3′ that corresponded to the GAS binding element in the human IRF-1 promoter was obtained from Genosys Ltd. (Cambridge, U.K.). The single-strand oligonucleotides were annealed together according to the manufacturer's instructions. The double-stranded NFκB binding site sequences: 5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′ and T4 polynucleotide kinase were purchased from Promega Ltd. (Southampton, U.K.). [γ-32P]-ATP for labelling oligonucleotides was purchased from Amersham Int. (Buckinghamshire, U.K.). All other chemicals were of the highest commercial grade available.

Cell culture

HUVECs were obtained from human umbilical veins by collagenase digestion as outlined previously (Laird et al., 1998). The cells were cultured in the endothelial cell basal Medium-2 (EBM-2) supplied by Biowhittaker Co. Passage 3-7 were used for the experiments outlined below.

Adenovirus-mediated overexpression of IκBα in HUVECs

A recombinant replication-deficient adenoviral vector encoding a wild-type porcine IκBα gene (Ad.IκBα) with a cytomegalovirus promoter and nuclear localization sequence was provided by Rainer de Martin (University of Vienna, Austria). This vector was previously described by Wrighton et al. (1996). The virus was propagated in 293 human embryonic kidney cells, then purified by ultracentrifugation in a caesium chloride gradient, the titre of the viral stock was determined by the end-point dilution method (Nicklin & Baker, 1999). HUVECs when approximately 70% confluent were incubated with adenovirus at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 30 – 300, for 16 h in normal growth medium after which the medium was replaced. The cells were stimulated 40 h post-infection. Infection with a control adenoviral vector encoding green fluorescent protein (Ad.GFP) was also performed and fluorescence microscopy confirmed that effective infection took place.

Western blotting

For the detection of IRF-1 and IκBα protein levels, the method employed was that described by Paul et al. (1995). Cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS, then solubilized in hot (70°C) SDS – PAGE sample buffer. The samples were dispersed by repeated passage through a 21G needle and then transferred to eppendorf tubes. The samples were boiled for 5 min and then stored at −20°C until analysis. Fifteen to 20 μg protein were subjected to SDS – PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels and then blotted onto nitrocellulose. The nitrocellulose membranes were incubated for 2 h in 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% (v v−1) Tween 20 pH 7.4 (NATT) buffer containing 3% BSA (w v−1) then incubated overnight in NATT containing 0.2% BSA (w v−1) and 1 μg ml−1 of anti-IRF-1 or IκBα antibody. Following six washes in NATT, the membranes were incubated with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit Ig-HRP for 2 h and then washed a further six times in NATT. The immunoblots were developed by the ECL detection system (Amersham). The Western blots were quantified by optical scanning densitometry.

Preparation of crude nuclear extracts and electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described by Schreiber et al. (1989) with minor modifications. Cells were grown to confluence on 6-well culture dishes and stimulated as appropriate. Following stimulation, reactions were terminated on ice by aspiration of media and washed twice with 750 μl of ice-cold PBS. A further 500 μl ice-cold PBS was then added to each well. Cells were then scraped and transferred to eppendorf tubes and pelleted by centrifugation (13,000 r.p.m. for 1 min). Supernatants were aspirated and 400 μl of 10 mM HEPES pH 7.9 containing (mM) KC1 10, EDTA 0.1, EGTA 0.1, DTT 1, PMSF 0.5, with 10 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin, and 10 μg ml−1 pepstatin was added to each tube. Cells were resuspended with light pipetting and left to swell on ice for 15 min. Twenty-five microlitres of 10% (w v−1) NP-40 (in above buffer) was added and each tube vortexed at full force for 10 s. Detergent extracts were centrifuged at 13,000 r.p.m. for 30 s to recover crude nuclear pellets and the supernatants aspirated. Pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of 20 mM HEPES Buffer pH 7.9 containing 25% (v v−1) glycerol, 0.4 M NaCl, (in mM) EDTA 1, EGTA 1, DTT 1, PMSF 0.5, with 10 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin and 10 μg ml−1 pepstatin. Pellets were then lightly vortexed and incubated on ice for 15 min. Samples were then sonicated on ice in a bath-type sonicator twice for 30 s and then centrifuged at 13,000 r.p.m. for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatants were then removed to fresh eppendorf tubes for both protein (Bradford) and DNA binding assays.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

For electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), the purified double-strand NFκB and GAS oligonucleotides were end-labelled with [γ-32P]-ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Binding reactions were performed by the method of Spink & Evans (1997) with slight modification: 5 μg of nuclear extract prepared as described above were incubated with 5× Binding Buffer (mM): MgCl2 5, EDTA 2.5, DTT 2.5, NaCl 250, Tris-HCl 50 (pH 7.5) and 0.25 mg ml−1 poly (dI-dC) in 20% (v v−1) glycerol) for 15 min at room temperature and then followed by a 20 min incubation at room temperature with 32P-labelled NF-κB or GAS double-strand DNA probe (approximately 50,000 c.p.m.). The mixture with 1 μl 10× loading buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.2% bromophenol blue and 40% glycerol) was electrophoresed at 100 V on pre-run polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× TBE buffer (0.89 M Tris base, 0.89 M boric acid and 0.02 M Na2EDTA) and dried gels analysed by autoradiography. When the super-shift assays were performed, polyclonal antibodies raised to NF-κB subunits, were incubated with the mixture of nuclear extracts and binding buffer for 20 min prior to the addition of 32P-labeled DNA probe.

IKK activity assay

Cells were incubated with vehicle or agonist as appropriate, washed twice in ice cold PBS and then lysed in 300 μl 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, containing (mM): EDTA 1, EGTA 0.5, NaCl 150, 0.1% (w v−1) Brij 35, 1% (w v−1) Triton X-100, sodium fluoride 20, sodium orthovanadate 0.5, β-glycerophosphate 20, PMSF 1 10 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 10 μg ml−1 pepstatin A, and 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin. Clarified extracts were incubated with 1.5 μg of either IKKα -specific antisera (Santa Cruz, U.S.A.) pre-coupled to protein G agarose (2 h, 4°C) with rotation. Immunocomplexes were collected by centrifugation (13,000×g for 1 min), washed once with solubilization buffer and once with 25 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.6 containing (mM) β-glycerophosphate 25, NaF 25, MgCl2 15 and DTT 1 before incubation in the same buffer containing 25 μM/5 μCi [γ-32P]-ATP and 1 μg of a recombinant GST-fusion protein of the N-terminus of IκBα (final volume 30 μl, 30 min) at 30°C. Samples were boiled with 4×sample buffer (5 min). Aliquots of each sample were then subjected to electrophoresis on 10% SDS – PAGE gels, fixed in 20 ml fixer solution (20% (v v−1) methanol/10% (v v−1) acetic acid, 30 min). After drying, phosphorylated IκB was visualized by autoradiography.

Statistical analysis

Results are represented as means±s.e.mean of indicated number of experiments. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using an unpaired t-test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

The effects of LPS and TNFα on IRF-1 expression in HUVECs

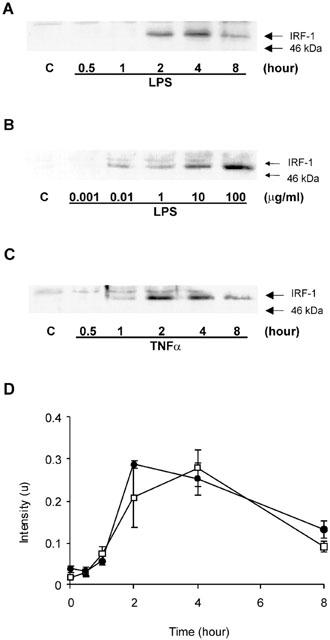

Exposure of HUVECs to 10 μg ml−1 LPS resulted in a time-dependent increase in IRF-1 expression. Following a delay of approximately 60 min, IRF-1 levels increased between 2 – 4 h before returning towards basal values at 8 h (density units mean±s.e.mean: control=0.018±0.0032, LPS (4 h)= 0.2792±0.0434, n=3) (Figure 1A,D). The response was also concentration-dependent, reaching a maximum between 30 and 100 μg ml−1 (Figure 1B). TNFα also stimulated IRF-1 induction with kinetics similar to LPS (density units mean±s.e.mean: control=0.0382±0.0075, TNFα (4 h)=0.2519±0.0372, n=3) (Figure 1C,D) and over a concentration range of 1 – 30 ng ml−1, consistent with that observed for effects of TNFα in other cellular systems (Laird et al., 1998).

Figure 1.

LPS- and TNFα-stimulated IRF-1 protein expression in HUVECs. HUVECs were exposed to 10 μg ml−1 LPS for the times indicated (A), with increasing concentrations of LPS for 4 h (B) or 30 ng ml−1 TNFα for the times indicated (C) and then assayed for IRF-1 content by Western blotting as outlined in the Methods section. Each blot is representative of at least three others. In (D), blots (A) and (C) were quantified by densitometry. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean from three independent experiments. LPS (□), TNFα (•).

LPS-stimulated NFκB DNA-binding activity in HUVECs

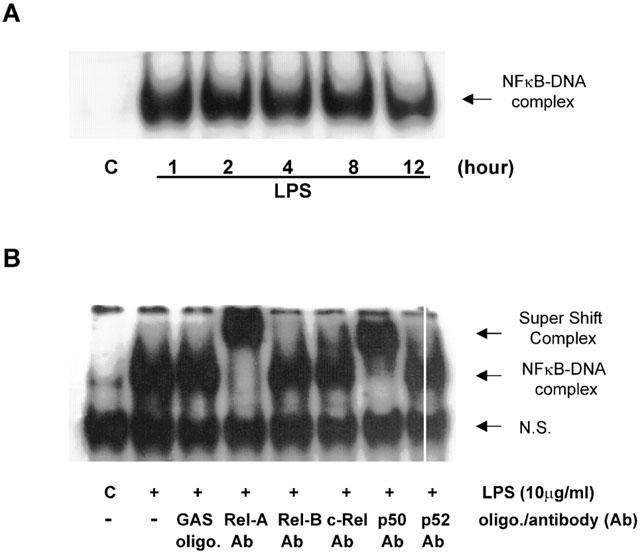

LPS also stimulated an increase in NFκB DNA-binding activity as assessed by EMSA (Figure 2A). Following LPS addition, maximum DNA-binding activity was achieved at approximately 60 min and was sustained for up to 12 h, the latest time point studied. Nuclear extracts prepared from LPS-stimulated cells were additionally pre-incubated with specific antibodies to NFκB isoforms. Incubation with antibodies to Rel-A (p65) and p50 but not Rel-B, c-Rel or p52 (Figure 2B), resulted in an enhanced retardation in the migration (‘super-shift') of the NFκB DNA-binding complex. This finding indicates that the p65 and p50 isoforms of NFκB are involved in DNA-binding to NFκB-sensitive genes in this cell type.

Figure 2.

LPS-stimulated p65/Rel-A and p50 NFκB DNA-binding activity in HUVECs. (A) HUVECs were incubated with 10 μg ml−1 LPS for the times indicated and then assayed for NFκB DNA-binding activity by EMSA as outlined in the Methods section. (B) nuclear extracts from LPS-stimulated cells were additionally incubated with vehicle, excess unlabelled GAS consensus oligonucleotide (oligo; +GAS lane) or anti-NFκB antibodies (Ab; p65/Rel-A, Rel-B, c-Rel, p50 and p52) as indicated and analysed by ‘super-shift' assay. Each autoradiogram is representative of at least three others. N.S. is non-specific complex.

The effects of PDTC and TLCK on LPS-stimulated IRF-1 expression and NFκB DNA-binding

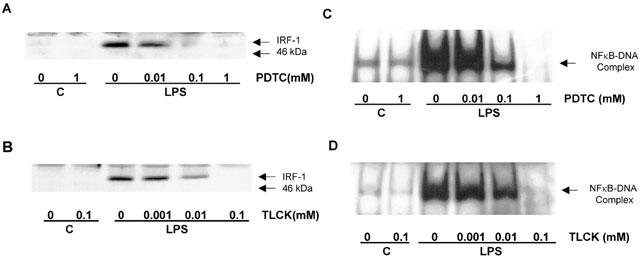

The role of NFκB in the regulation of IRF-1 induction was further examined using the known NFκB inhibitors, PDTC and TLCK (Figure 3). Both pharmacological agents inhibited LPS-stimulated induction of IRF-1 expression in a concentration-dependent manner. For PDTC, significant inhibition (21±2.8% of maximum, n=3, P<0.05) was observed at 100 μM, with complete abolition at 1 mM (Figure 3A). TLCK was more potent, significantly reducing the response following pretreatment with a concentration of 10 μM (53.1±2.9% of maximum, n=3, P<0.05), with complete abolition observed at 100 μM (Figure 3B). Furthermore, both PDTC and TLCK reduced LPS-stimulated NFκB DNA-binding activity over a similar concentration range to that observed for the inhibition of IRF-1 expression with complete abolition at 1 mM and 100 μM respectively (Figures 3C,D).

Figure 3.

The effect of PDTC and TLCK on LPS -stimulated IRF-1 induction and NFκB DNA-binding in HUVECs. HUVECs were pre-incubated with increasing concentrations of PDTC (A,C) or TLCK (B,D) for 30 min prior to exposure to 10 μg ml−1 LPS for a further 4 h (A,B) or 60 min (C,D) with 10 μg ml−1 LPS. Cellular IRF-1 content was then assayed by Western blotting, whilst NFκB DNA-binding was measured by EMSA, as outlined in the Methods section. Each blot is a single experiment representative of at least three others.

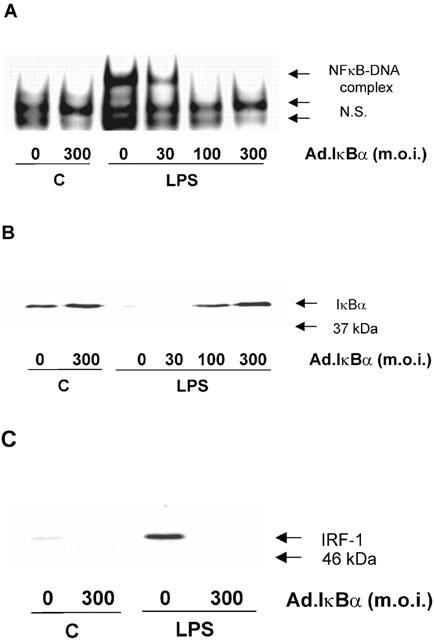

In order to exclude any possible non-specific effects of NFκB inhibitors on HUVEC responses, cells were infected with a recombinant adenovirus encoding the IκBα gene. The overexpressed IκBα protein binds and retains free NFκB in the cytoplasm, thereby preventing its translocation to the nucleus (Figure 4) as previously described by Wrighton et al. (1996). Infection with IκBα virus, but not Ad.GFP control vector (data not shown), caused a concentration-dependent inhibition of LPS-stimulated NFκB DNA-binding (Figure 4A). Complete abolition was observed at an m.o.i. of between 100 and 300 (Figure 4A). This intervention also inhibited LPS-stimulated translocation of p65 NFκB (Rel A) to the nucleus (data not shown) and LPS-stimulated loss in the cellular expression of IκBα (Figure 4B). Similarly, LPS-stimulated induction of IRF-1 was also abolished over a similar concentration range (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

The effect of adenovirus-mediated IκBα expression on LPS-stimulated NFκB DNA-binding, IκBα loss and IRF-1 induction in HUVECs. HUVECs were infected with Ad.IκBα (m.o.i. of 30 – 300) prior to further exposure to 10 μg ml−1 LPS for the times indicated. NFκB DNA-binding was assessed by EMSA (A), IκBα (B) and IRF-1 (C) protein levels determined by Western blotting as outlined in the Methods section. Each blot and autoradiograph are representative of at least three others.

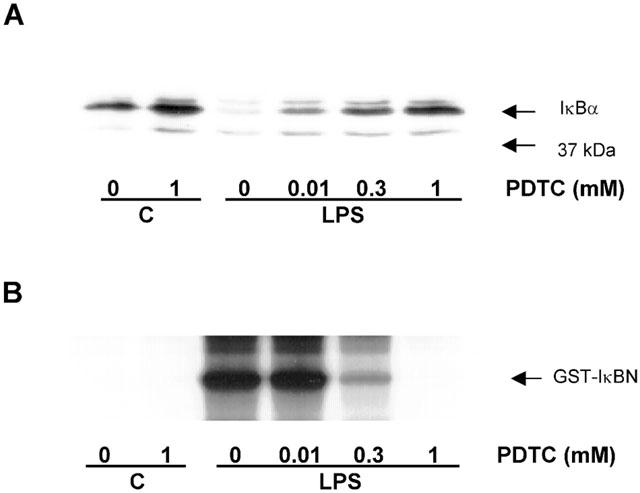

The effect of PDTC upon LPS-stimulated IκBα degradation and IKKα activity

In addition to inhibition of NFκB DNA-binding, PDTC also showed inhibitory activity against intermediates located further upstream in the LPS-stimulated NFκB cascade. Pretreatment of HUVECs with PDTC inhibited LPS-stimulated degradation of IκBα expression (Figure 5A), with full reversal being achieved by 1 mM PDTC. LPS also stimulated an increase in the activity of the upstream regulatory kinase IKKα (Figure 5B). This response was also inhibited by PDTC over a similar concentration range. These data strongly suggest a role for IKK in the regulation of LPS-stimulated IRF-1 induction in HUVECs.

Figure 5.

The effect of PDTC on LPS-stimulated IκBα degradation and IKKα activity in HUVECs. HUVECs were pre-incubated with increasing concentrations of PDTC for 30 min prior to exposure to 10 μg ml−1 LPS for a further 30 min. Cellular IκBα content (A) was assessed by Western blotting and IKKα activity (B) was assessed by in vitro kinase assay as outlined in the Methods section. Each blot and autoradiograph are representative of at least three others.

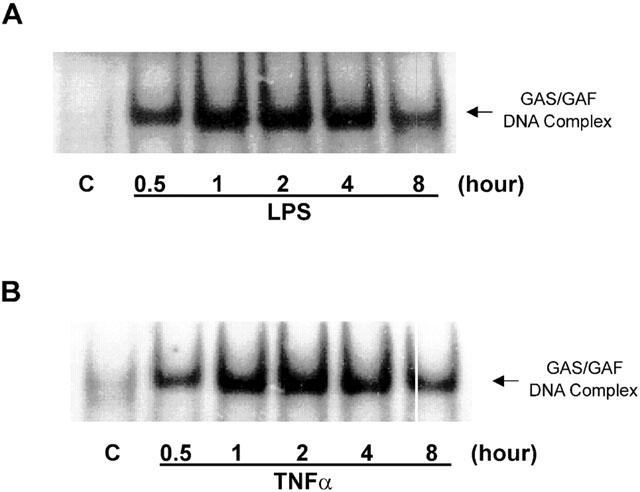

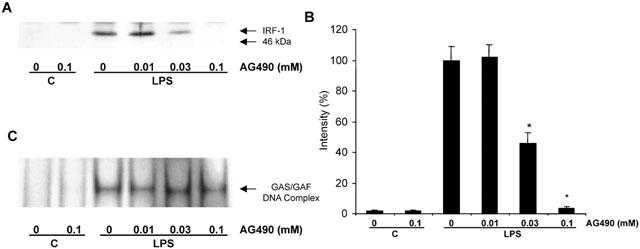

The effect of AG490 on LPS-stimulated IRF-1 expression and GAS/GAF DNA-binding activity

We also found that in HUVECs, both LPS and TNFα stimulated GAS/GAF DNA-binding activity (Figure 6). The responses to both agents were rapid in onset and maximal by 30 – 60 min. The rapidity of the response was similar to that observed with IFNγ stimulation in RAW 264.7 macrophages (Liu et al., 1999) and suggested a possible role for signalling events associated with this cytokine. To this end we utilized the JAK-2 inhibitor AG490 (Meydan et al., 1996; Nakashima et al., 1999; Takahashi et al., 1999). Preincubation of HUVECs with increasing concentrations of AG490 markedly reduced LPS-stimulated IRF-1 expression (Figure 7A,B). Inhibition was observed to be significant following pre-treatment with 30 μM (45.6±6.9% of full induction, n=3) with the response completely abolished at 100 μM. Surprisingly however, over a similar concentration range there was no significant inhibition of LPS-stimulated GAS/GAF DNA-binding (Figure 7C).

Figure 6.

LPS- and TNFα-stimulated GAS/GAF DNA-binding activities in HUVECs. HUVECs were incubated with 10 μg ml−1 LPS (A) or 30 ng ml−1 TNFα (B) for the times indicated and GAS/GAF DNA-binding activity assessed by EMSA as outlined in the Methods section. Each autoradiograph is representative of at least three others.

Figure 7.

The effect of AG490 on LPS-stimulated IRF-1 induction and GAS/GAF DNA-binding activity in HUVECs. HUVECs were incubated with increasing concentrations of AG490 for 30 min prior to exposure to 10 μg ml−1 LPS for either 4 h (A,B) or 2 h (C). Samples were assayed for IRF-1 content by Western blotting (A) or GAS/GAF DNA-binding activity by EMSA (C) as outlined in the Methods section. In (B), IRF-1 expression was quantified by densitometry. Each blot or autoradiograph is representative of at least three others.

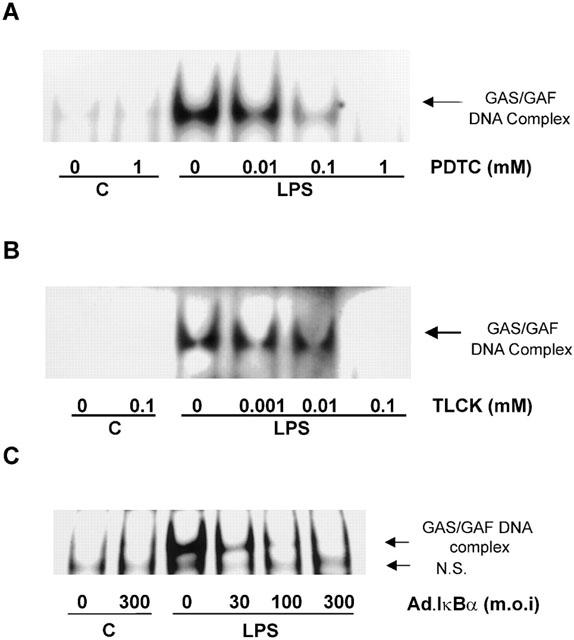

The effects of PDTC, TLCK and adenovirus-mediated IκBα expression on LPS-stimulated GAS/GAF DNA-binding activity

Figure 8 shows the effect of the NFκB inhibitors, PDTC and TLCK and adenovirus-mediated IκBα expression, upon LPS-stimulated GAS/GAF activation. Both pharmacological agents prevented the activation of GAS/GAF DNA-binding activity. These effects were achieved within a concentration range that was consistent with their inhibition of NFκB DNA-binding activity, with complete inhibition of LPS-stimulated GAS/GAF activity observed at 1 mM PDTC and 100 μM TLCK respectively (Figure 8A,B). Similarly, infection with IκBα-encoding adenovirus caused a concentration-dependent inhibition of LPS-stimulated GAS/GAF DNA-binding activity (Figure 8C) over the same concentration range as that observed for inhibition of both NFκB DNA-binding and IRF-1 protein expression (see Figure 4A,C).

Figure 8.

The effect of PDTC, TLCK and IκBα adenovirus on LPS-stimulated GAS/GAF DNA-binding activity in HUVECs. HUVECs were pre-incubated with increasing concentrations of PDTC (A) or TLCK (B) for 30 min or IκBα virus (C) for 40 h prior to exposure to 10 μg ml−1 LPS for a further 60 min. GAS/GAF DNA-binding activity was then assessed by EMSA as outlined in the Methods section. Each autoradiograph is representative of at least three others.

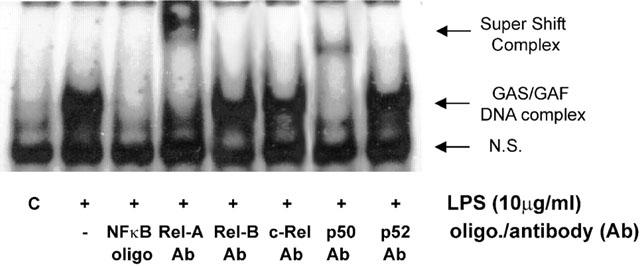

Rel A and p50 are involved in LPS-stimulated GAS/GAF DNA-binding activity

Figure 9 shows the effect of antibodies to the NFκB subunits Rel A and p50 on LPS-stimulated GAS/GAF DNA-binding. Pre-incubation with either antibody resulted in a ‘supershift' in GAS/GAF DNA-binding. This was not mimicked by incubation with antibodies against Rel-B, c-Rel or p52, which were shown previously not to be associated with LPS-stimulated NFκB DNA-binding (Figure 2B).

Figure 9.

The effect of p65/Rel-A and p50 antibodies on LPS-stimulated GAS/GAF DNA-binding in HUVECs. HUVECs were incubated with vehicle (C) or 10 μg ml−1 LPS for 60 min and nuclear extracts prepared as outlined in the Methods section. The nuclear extracts were additionally incubated with vehicle, excess unlabelled NFκB consensus oligonucleotide (oligo; +NFκB lane) or anti-NFκB antibodies (Ab; p65/Rel-A, Rel-B, c-Rel, p50 and p52) as indicated and then analysed by ‘super-shift' EMSA assay as outlined in the Methods section. Each autoradiograph is representative of at least three others.

Discussion

In this study we sought to examine the role of intracellular signalling pathways in the regulation of IRF-1 induction in response to LPS in HUVECs. Although NFκB has been implicated in the regulation of IRF-1 in some cell types, in a previous study in RAW264.7 macrophages, we found that despite strong activation of NFκB, LPS stimulated only a minor increase in IRF-1 expression implying a requirement for additional pathways (Liu et al., 1999). Furthermore, in that study, LPS was able to enhance IFNγ-stimulated IRF-1 expression suggesting a conditional role for NFκB in the induction of IRF-1. Since the majority of studies examining LPS-stimulated induction of IRF-1 have included IFNγ as a co-stimulant, making interpretation as to the relative involvement of individual signalling pathways difficult, we have examined another system, the HUVECs, known to respond to cytokines with an increase in IRF-1 expression (Karmann et al., 1996).

To our surprise we found, for the first time, that LPS alone was a rather efficacious activator of IRF-1 protein expression. This immediately suggested that NFκB may be more important in mediating the effects of LPS upon IRF-1 expression in human endothelial cells than in mouse macrophages. This was not due to differences within the promoters of mouse and human IRF-1 genes, as both contain multiple sites for NFκB DNA-binding (Miyamoto et al., 1988; Harada et al., 1994). We did consistently find that LPS stimulated IRF-1 induction in the low μg ml−1 rather than the ng ml−1 range shown for other LPS-induced responses (Zen et al., 1998, Faure et al., 2000). The reason for this is unclear but is likely to be due to the lack of soluble CD-14 and/or LPS-binding protein in the condition media used to culture the HUVECs, these are required for high affinity activation of a number of LPS receptor subtypes including TLR-4 (Yang et al., 1998; Lien et al., 2000). Recently, HUVECs have been shown to express high levels of TLR-4 consistent with this interpretation (Faure et al., 2000). However, as TNFα was also as effective as LPS in inducing the expression of IRF-1 this suggests that the effects of LPS are likely to be transduced through a receptor and that activation of intracellular pathways common to both agonists are involved, including, though not exclusively, the NFκB cascade.

The notion that NFκB plays an important role in IRF-1 expression in HUVECs was further examined using both pharmacological studies and the use of inhibitory adenovirus. Both TLCK and PDTC were found to be effective inhibitors of LPS-stimulated IRF-1 expression in this cell type. Whilst the action of TLCK in preventing IκB degradation has been well described previously (Mackman, 1994; Jeong et al., 1997), the effect of PDTC is more controversial. PDTC has been shown to directly inhibit NFκB DNA-binding through either pro- or anti-oxidant properties although the ability of PDTC to inhibit NFκB in this way is cell-type dependent (Brennan & O'neill, 1996; Bowie et al., 1997). However, our studies also showed that in HUVECs at least, the site of PDTC's inhibitory effect is at the level of IKK or upstream, since this compound was able to inhibit LPS-stimulated IKK activity. Thus, this result confirms, for the first time, that LPS mediates IRF-1 induction through stimulation of an IKK/IκB/NFκB pathway in primary cultures of human endothelial cells and indicates the site of action of this compound to be at an early point in the cascade.

The use of pharmacological inhibitors was problematic however, when considering the role of NFκB in response to other agents. We consistently found that LPS-stimulated NFκB activation was inhibited by PDTC treatment whereas TNFα-stimulated activation was not. These results however, although agreeing with work by Bowie et al. (1997), disagreed with an earlier report that showed good inhibition of TNFα -stimulated NFκB activation (Munoz et al., 1996). Thus the differential sensitivity between LPS and TNFα in this regard could not readily be ascribed to receptor-mediated differences in the mechanisms involved in regulating the NFκB cascade. In order to exclude the potential for these compounds to work in a non-specific manner in LPS-stimulated cells and any possible experimental error in the use of PDTC, we infected cells with adenovirus encoding the IκBα gene. This virus has been previously characterized in HUVECs and was found to inhibit TNFα-induced degradation of IκBα (Weber et al., 1999). Indeed, infection of HUVECs abolished LPS-stimulated NFκB DNA-binding as outlined previously (Figure 4A) and also the translocation of NFκB to the nucleus, suggesting the viral construct is acting in the manner described. Significantly, this intervention abolished LPS-stimulated IRF-1 induction, further confirming the central role for NFκB in the regulation of IRF-1 induction in response to LPS.

It is well accepted that activation of the JAK/STAT pathway, in particular in response to the interferons and other cytokines (Taniguchi et al., 1995), mediates positive effects upon IRF-1 induction due to binding of STATs to the GAS on the IRF-1 promoter (Pine, 1997). In RAW 264.7 macrophages however, LPS is unable to stimulate STAT activity and this strongly correlates with the relatively small induction of IRF-1 in this cell type (Deng et al., 1996; Liu et al., 1999). LPS has previously been shown to regulate the GAS/GAF DNA-binding interactions on other genes through the latent expression of a STAT, probably STAT 5 (Yamaoka et al., 1998) or an unidentified GAS/GAF DNA-binding protein (Gupta et al., 1998). However, we found that both LPS and TNFα stimulated an increase in GAS/GAF DNA-binding within a time-frame that is unlikely to involve an intermediate synthetic step. This again distinguishes HUVECs from RAW 264.7 macrophages and indicates that rapid GAS/GAF interaction may be a requisite for IRF-1 induction irrespective of the cell type or stimulus.

As rapid GAS/GAF DNA-binding is associated with an increase in STAT binding we reasoned that rapid activation of the JAK/STAT cascade may be involved in mediating the effects of LPS and TNFα. Consistent with this notion we found that the JAK-2 inhibitor AG490 was able to inhibit IRF-1 expression. This was found to be comparable to the observed effect of this inhibitor in a number of other cell types including leukaemic cells, rat mesangial cells and human osteoblast-like cells (Meydan et al., 1996; Nakashima et al., 1999; Takahashi et al., 1999). However, we found that LPS-stimulated GAS/GAF DNA-binding was not affected by AG490 suggesting that the involvement of the JAK/STAT pathway is unlikely. Preliminary studies in our laboratory supported this contention, neither LPS nor TNFα stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK-1 or JAK-2 in HUVECs (results not shown).

There are of course other possible mechanisms by which LPS could activate STAT. LPS is able to mediate the phosphorylation of STAT1 at ser727 by a process that requires p38 MAP kinase (Kovarik et al., 1999). However, we found in preliminary experiments that the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 did not affect LPS-stimulated IRF-1 induction, suggesting that this type of pathway is not involved. It is also possible that LPS may activate EGF receptor kinases and cell signalling pathways associated with activation of that receptor. However, there is at present no studies to suggest that LPS can mediate transactivation of the EGF receptor. In addition we found that the MEK-1 inhibitor PD098059 did not inhibit LPS-stimulated IRF-1 induction within this cell type, suggesting that a major pathway activated by EGF and potentially involved in STAT activation, is not implicated in the regulation of IRF-1 in this cell type. At present however, we cannot determine the site at which AG490 is having its inhibitory effects. Several possibilities exist, including a direct effect upon IRF-1 transcription and a destabilization of protein or mRNA. These potential mechanisms of inhibition are presently being examined in our laboratory.

Our results also indicate that NFκB plays some role in the regulation of GAS/GAF DNA-binding. Both PDTC and TLCK were able to inhibit GAS/GAF DNA-binding over a concentration range that was similar to their inhibition of both IRF-1 protein expression and NFκB DNA-binding. The effects of the inhibitors were also mimicked by infection with the adenovirus encoding IκBα suggesting that these inhibitors were not acting in a non-specific manner but rather their effects were due to an inhibition of NFκB DNA-binding activity.

In addition, we found that antibodies directed against p65/Rel-A and p50 induced a ‘super-shift' in GAS/GAF DNA-binding and was similar to the observed results for LPS-stimulated NFκB DNA-binding. This phenomenon has been identified previously in other cell types such as RAW 264.7 macrophages and human Ramos cells (Deng et al., 1996, Gupta et al., 1998), although this is the first study to identify a similar phenomenon in human endothelial cells. This phenomenon is unlikely to be artifactual and may in fact represent the formation of a multi-protein-DNA nucleocomplex. The NFκB proteins are unlikely to bind directly to the GAS/GAF oligonucleotide sequence given that the previously described NFκB binding motifs all share the same head (GGG) and end (CC or AC) sequences from 5′ to 3′ with varying central nucleotides (Schreck & Baeuerle, 1990; Grilli et al., 1993) that are distinct from the GAS sequence (5′-TTTCCCCGAAA-3′) used in this study. Furthermore, the formation of LPS-stimulated GAS/GAF protein-DNA complexes were sensitive to specific competition with excess amounts of unlabelled NFκB oligonucleotide whilst LPS-stimulated NFκB DNA-binding was insensitive to competition with excess unlabelled GAS oligonucleotide. This supports further the hypothesis that NFκB isoforms, in this case p65/Rel-A and p50, are likely to interact with GAF that is in complex with GAS sequences yet GAS/GAF complexes are not necessary involved in the formation of NFκB-DNA complexes. NF-κB may therefore interact either directly with GAF, or indirectly via additional transcription factors present in the LPS-activated nuclear extracts. These proteins may also be regulated by LPS and bind to elements in close proximity to the GAS sequence and allow the formation of a multiple-transcription factor complex, in a manner similar to that described previously for members of the NFκB protein family (Sheppard et al., 1998; Saura et al., 1999). Hence, the presence of NFκB proteins in certain cases may be an integral component to the successful formation of functional GAF/GAS complexes.

Overall, these findings suggest that in some cell types, LPS-stimulated IRF-1 expression is significantly regulated by NFκB proteins, although the precise details of their roles in this process remain unclear. A rapid increase in GAS/GAF DNA-binding may be a requisite for substantial IRF-1 induction, however maximum induction is likely to rely upon the direct binding of p65 and p50 to NFκB consensus binding sequences and their subsequent interaction with the GAF/GAS binding sites within the IRF-1 promoter. This distinguishes HUVEC cells from other cell types in the mechanisms involved in regulating IRF-1 expression.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored in part by The British Heart Foundation.

Abbreviations

- Ad.GFP

adenovirus encoding GFP

- Ad.IκBα

adenovirus encoding IκBα

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- GAS/GAF

gamma interferon activation site/gamma interferon activation factor

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- IFN

interferon

- IκB

inhibitory kappa B

- IKK

inhibitory kappa B kinase

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IRF-1

interferon regulatory factor-1

- ISRE

IFN-stimulated response element

- JAK/STAT

Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NFκB

nuclear factor kappa B

- PDTC

pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate

- TLCK

N-α-tosyl-L-lysine chloromethyl ketone

- TNFα

tumour necrosis factor alpha

References

- BOWIE A.G., MOYNAGH P.N., O'NEILL L.A.J. Lipid peroxidation is involved in the activation of NF-kappaB by tumor necrosis factor but not interleukin-1 in the human endothelial cell line ECV304. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25941–25950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRENNAN P., O'NEILL L.A.J. 2-Mercaptoethanol restores the ability of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) to bind DNA in nuclear extracts from interleukin 1-treated cells incubated with pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC) Biochem. J. 1996;320:975–981. doi: 10.1042/bj3200975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOW J.C., YOUNG D.W., GOLENBOCK D.T., CHRIST W.J., GUSOVSKY F. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:10689–10692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENG W., OHMORI Y., HAMILTON T.A. LPS does not directly induce STAT activity in mouse macrophages. Cell. Immunol. 1996;170:20–24. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIDONATO J., MERCURIO F., ROSETTE C., WU-LI J., SUYANG H., GHOSH S., KARIN M. Mapping of the inducible IκB phosphorylation sites that signal its ubiquitination and degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:1295–1304. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAURE E., EQUILS O., SIELING P.A., THPOMAS L., ZHANG F.X., KIRSCHING C.J., POLENATARUTTI N., MUZIO M., ARDITI M. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide activates NFκB through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) in cultured human dermal endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:11058–11063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUPTA S., XIA D., JIANG M., LEE S., PERNIS A.B. Signaling pathways mediated by the TNF- and cytokine-receptor families target a common cis-element of the IFN regulatory factor 1 promoter. J. Immunol. 1998;161:5997–6004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARADA H., TAKAHASHI E., ITOH S., HARADA K., HORI T.A., TANIGUCHI T. Structure and regulation of the human interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) and IRF-2 genes: implications for a gene network in the interferon system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:1500–1509. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HECKER M., PREISS C., KLEMM P., BUSSE R. Inhibition by antioxidants of nitric oxide synthase expression in murine macrophages: role of nuclear factor κ B and interferon regulatory factor 1. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:2178–2184. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JEONG J.Y., KIM K.U., JUE D.M. Tosylphenylalanine chloromethyl ketone inhibits TNF-α mRNA synthesis in the presence of activated NF-κB in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Immunology. 1997;92:267–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRILLI M., CHIU J.J., LENARDO M.J. NF-κB and Rel: participants in a multiform transcriptional regulatory system. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1993;143:1–62. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61873-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMIJO R., HARADA H., MATSUYAMA T., BOSLAND M., GERECITANO J., SHAPIRO D., LE J., KOH S.I., KIMURA T., GREEN S.J., MAK T.W., TANIGUCHI T., VILCEK J. Requirement for transcription factor IRF-1 in NO synthase induction in macrophages. Science. 1994;263:1612–1615. doi: 10.1126/science.7510419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARMANN K., MIN W., FANSLOW W.C., POBER J.S. Activation and homologous desensitization of human endothelial cells by CD40 ligand, tumor necrosis factor, and interleukin 1. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:173–182. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOVARIK P., STOIBER D., EYERS P.A., MENGHINI R., NEININGER A., GAESTEL M., COHEN P., DECKER T. Stress-induced phosphorylation of STAT1 at Ser727 requires p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases whereas IFN-γ uses a different signalling pathway. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1999;96:13956–13961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUMAR A., YANG Y.L., FLATI V., DER S., KADEREIT S., DEB A., HAQUE J., REIS L., WEISSMANN C., WILLIAMS B.R. Deficient cytokine signaling in mouse embryo fibroblasts with a targeted deletion in the PKR gene: role of IRF-1 and NF-κB. EMBO J. 1997;16:406–416. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAIRD S.M., GRAHAM A., PAUL A., GOULD G.W., KENNEDY C., PLEVIN R. Tumour necrosis factor stimulates stress-activated protein kinases and the inhibition of DNA synthesis in cultures of bovine aortic endothelial cells. Cell Signal. 1998;10:473–480. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(97)00173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIEN E., MEANS T.K., HEINE H., YOSHIMURA A., KUSUMOTO S., FUASE K., FENTON M.J., OIKAWA M., QUERESHI N., MONKS B., FINBERG R.W., INGALLS R.R., GOLENBOCK D.T. Toll-like receptor 4 imparts ligand-specific recognition of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105:497–504. doi: 10.1172/JCI8541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU L., PAUL A., PLEVIN R. The effect of NF-κB inhibitors on IRF-1 expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:146P. [Google Scholar]

- LIU L., PAUL A., PLEVIN R. The NFκB pathway participates in the increase in IRF-1 expression in human endothelial cells stimulated by lipopolysaccharide and tumour necrosis factor-α. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;135:86P. [Google Scholar]

- MACKMAN N. Protease inhibitors block lipopolysaccharide induction of tissue factor gene expression in human monocytic cells by preventing activation of c-Rel/p65 heterodimers. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:26363–26367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN E., NATHAN C., XIE Q.W. Role of interferon regulatory factor 1 in induction of nitric oxide synthase. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:977–984. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYDAN N., GRUNBERGER T., DADI H., SHAHAR M., ARPAIA E., LAPIDOT Z., LEEDER J.S., FREEDMAN M., COHEN A., GAZIT A., LEVITZKI A., ROIFMAN C.M. Inhibition of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia by a Jak-2 inhibitor. Nature. 1996;379:645–648. doi: 10.1038/379645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYAMOTO M., FUJITA T., KIMURA Y., MARUYAMA M., HARADA H., SUDO Y., MIYATA T., TANIGUCHI T. Regulated expression of a gene encoding a nuclear factor, IRF-1, that specifically binds to IFN-β gene regulatory elements. Cell. 1988;54:903–913. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUNOZ C., PASCUAL-SALCEDO D., CASTELLANOS M.C., ALFRANCA A., ARGONES J., VARA A., REDONDO M.J., DE LANDAZURI M.O. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate inhibits the production of interleukin-6, interleukin-8 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by human endothelial cells in response to inflammatory mediators: modulation of NF-kappa B and AP-1 transcription factors activity. Blood. 1996;88:3482–3490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKASHIMA O., TERADA Y., INOSHITA S., KUWAHARA M., SASAKI S., MARUMO F. Inducible nitric oxide synthase can be induced in the absence of active nuclear factor-κB in rat mesangial cells: involvement of the Janus kinase 2 signaling pathway. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1999;10:721–729. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V104721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICKLIN S.A., BAKER A.H.Simple methods for preparing recombinant adenoviruses for high-efficiency transduction of vascular cells Methods in Molecular Medicine: Vascular Disease: Molecular Biology and Gene Therapy Protocols 1999Totowa: The Humana Press, NJ; 271–283.ed. Baker, A.H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAUL A., PENDREIGH R.H., PLEVIN R. Protein kinase C and tyrosine kinase pathways regulate lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide synthase activity in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:482–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13252.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PINE R. Convergence of TNFα and IFNγ signalling pathways through synergistic induction of IRF-1/ISGF-2 is mediated by a composite GAS/κB promoter element. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4346–4354. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAURA M., ZARAGOZA C., BAO C., MCMILLAN A., LOWENSTEIN C.J. Interaction of interferon regulatory factor-1 and nuclear factor kappaB during activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase transcription. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;289:459–471. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHAPER F., KIRCHHOFF S., POSERN G., KOSTER M., OUMARD A., SHARF R., LEVI B.Z., HAUSER H. Functional domains of interferon regulatory factor I (IRF-1) Biochem. J. 1998;335:147–157. doi: 10.1042/bj3350147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRECK R., BAEUERLE P.A. NF-κB as inducible transcriptional activator of the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990;10:1281–1286. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.3.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHREIBER E., MATTHIAS P., MULLER M.M., SHAFFER W. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts' prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6419. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEPPARD K.A., PHELPS K.M., WILLIAMS A.J., THANOS D., GLASS C.K., ROSENFELD M.G., GERRITSEN M.E., COLLINS T. Nuclear integration of glucocorticoid receptor and nuclear factor-kappaB signaling by CREB-binding protein and steroid receptor coactivator-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:29291–29294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHUAI K. Interferon-activated signal transduction to the nucleus. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 1994;6:253–259. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPINK J., EVANS T. Binding of the transcription factor interferon regulatory factor-1 to the inducible Nitric-oxide synthase promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24417–24425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAHASHI M.O., TAKAHASHI Y., IIDA K., OKIMURA Y., KAJI H., ABE H., CHIHARA K. Growth hormone stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (p125(FAK)) and actin stress fiber formation in human osteoblast-like cells, Saos2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;263:100–106. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANAKA N., KAWAKAMI T., TANIGUCH T. Recognition DNA sequences of interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) and IRF-2, regulators of cell growth and the interferon system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:4531–4538. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANIGUCHI T., HARADA H., LAMPHIER M. Regulation of the interferon system and cell growth by the IRF transcription factors. J. Cancer. Res. Clin. Oncol. 1995;121:516–520. doi: 10.1007/BF01197763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLMAN C.L., SEVER C.E., PALLAVICINI M.G., HARADA H., TANAKA N., SLOVAK M.L., YAMAMOTO H., HARADA K., MEEKER T.C., LIST A.F., TANIGUCHI T. Deletion of IRF-1, mapping to chromosome 5q31.1. in human leukemia and preleukemic myelodyaplasias. Science. 1993;259:968–971. doi: 10.1126/science.8438156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBER K.S.C., DRAUDE G., ERL W., DE MARTIN R., WEBER C. Monocyte arrest and transmigration on inflamed endothelium in shear flow is inhibited by adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of IκBα. Blood. 1999;93:3685–3693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WRIGHTON C.J., HOFER-WARBINEK R., MOLL T., EYTNER R., BACH F.H., DE MARTIN R. Inhibition of endothelial cell activation by adenovirus-mediated expression of I kappa B alpha, an inhibitor of the transcription factor NF-kappa B. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:1013–1022. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAOKA K., OTSUKA T., NIIRO H., ARINOBU Y., NIHO Y., HAMASAKI N., IZUHARA K. Activation of STAT5 by lipopolysaccharide through granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor production in human monocytes. J. Immunol. 1998;160:838–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG R.B., MARK M.R., GRAY A., HUANG A., XIE M.H., ZHANG M., GODDARD A., WOOD W.I., GURNEY A.L., GODOWSKI P.J. Toll-like receptor-2 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced cellular signalling. Nature. 1998;395:284–288. doi: 10.1038/26239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZEN K., KARSAN A., EUNSON T., YEE E., HARLAN J.M. Lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-κB activation in human endothelial cells involves degradation of IκBα but not IκBβ. Exp. Cell Res. 1998;243:425–433. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]