Abstract

Haeme oxygenase (HO) is an enzyme mainly localized in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum and involved in haeme degradation and in the generation of carbon monoxide (CO). Here we investigate (1) whether the inducible isoform of HO (HO-1) is expressed in the isolated heart of the guinea-pig and (2) the functional significance of HO-1 on the response to antigen in isolated hearts taken from actively sensitized guinea-pigs.

Both the HO-1 expression and activity are consistently increased in hearts from guinea-pigs pretreated with hemin, an HO-1 inducer (4 mg kg−1 i.p., 18 h before antigen challenge). The administration of the HO-1 inhibitor zinc-protoporphyrin IX (ZnPP-IX, 50 μmol kg−1, i.p., 6 h before hemin) abolished the increase of both the HO-1 expression and activity.

In vitro challenge with the specific antigen of hearts from actively sensitized animals evokes a positive inotropic and chronotropic effect, a coronary constriction followed by dilation and an increase in the amount of histamine in the perfusates. In hearts from hemin-pretreated animals, antigen challenge did not modify the heart rate and the force of contraction; the coronary outflow was significantly increased and a diminution of the release of histamine was observed. The patterns of cardiac anaphylaxis were fully restored in hearts from animals treated with ZnPP-IX 6 h before hemin.

In isolated hearts perfused with a Tyrode solution gassed with 100% CO for 5 min and successively reoxygenated, the response to antigen was similar to that observed in hearts from hemin-pretreated animals.

Pretreatment with hemin or the exposure to exogenous CO were linked to an increase in cardiac cyclic GMP levels and to a decrease of tissue Ca2+ levels.

The study demonstrates that overexpression of HO-1 inhibits cardiac anaphylaxis through the generation of CO which, in turn, decreases the release of histamine through a cyclic GMP- and Ca2+-dependent mechanism.

Keywords: Haeme oxygenase-1, hemin, zinc protoporphyrin IX, carbon monoxide, cardiac anaphylaxis, histamine, cyclic GMP, cytosolic calcium

Introduction

In a recent population-based study (Yocum et al., 1999; see also the commentary by Weiler, 1999), the average annual incidence rate of anaphylaxis was 21 for 100,000 people; the hospitalization rate was 7% and one patient died showing that anaphylaxis is common and may be fatal. Among the cohort studied, 41% of patients had cardiovascular symptoms such as tachyarrhythmias, hypotension and cardiac arrest. The model incepted by Cesaris Demel (1910), in which the challenge in vitro with a specific antigen of isolated heart preparations from actively sensitized animals results in an increase in rate and strength of contraction, arrhythmias and sudden changes in coronary outflow, provides a reproducible tool to study the cardiac anaphylactic reaction. Cardiac anaphylaxis is widely recognized as an example of type I hypersensitivity in which the release of histamine from resident cardiac mast cells participates in myocardial damage (Capurro & Levi, 1975).

Our previous experiments have shown that autacoids down-regulate the response to antigen in isolated hearts of actively sensitized guinea-pigs. Histamine itself abates the immunologically induced increase in rate and strength of cardiac contraction showing an autocrine down-regulation of cardiac anaphylaxis (Blandina et al., 1987). The peptide hormone relaxin and nitric oxide donors fully inhibit the cardiac response to antigen by decreasing the amounts of histamine released (Masini et al., 1994c). Consistently, these effects may be accounted for by the inhibition of the immunological release of histamine from mast cells (Masini et al., 1994b).

We have recently shown that carbon monoxide (CO) is a powerful inhibitor of the immunological activation of guinea-pig mast cells and of human basophils. In isolated purified guinea-pig mast cells from actively sensitized animals, the release of histamine by antigen is decreased in hemin-pretreated animals and after in vitro exposure to CO, in a way which is coupled with the increase in cyclic GMP levels and the decrease of intracellular Ca2+ (Ndisang et al., 1999). The same effects were obtained in human basophils exposed to anti-human-IgE (Mirabella et al., 1999).

The involvement of CO in the control of cardiovascular tone in a manner similar to NO has stirred a great interest recently. Motterlini et al. (1998) have provided evidence for a crucial role of the haeme oxygenase (HO) / CO pathway in the regulation of blood pressure under stress conditions in vivo, by showing that the suppression of the hypertensive response after surgical stress in rats was correlated with a significant over expression of HO-1 in the heart, as well as increased production of aortic CO and of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cyclic GMP). Several lines of evidence also demonstrate that hypoxia induces HO-1 expression and activity in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells, suggesting that the HO signalling pathway provides an endogenous adaptive defence mechanism against oxidative stress (Siow et al., 1999). Myocardial ischaemia followed by reperfusion leads to a coordinated expression of mRNA encoding HO-1, proposing that myocardial adaptive response to ischaemia involves up-regulation of HO-1 in cells of perivascular region, and that this enzyme may participate in regulating vascular tone via CO (Sharma et al., 1999). Moreover, inhalation of CO attenuates fibrin deposition and expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) in mice undergoing lung ischaemia-reperfusion (Fujita et al., 2001).

The aim of the present study is to evaluate whether manipulation of the HO pathway could modulate the response to antigen of isolated hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs, and to correlate the changes in the mechanical responses with the release of histamine and the intracellular levels of second messengers. We have also studied whether the administration of exogenous CO could mimic the effects of the increased expression and activity of HO-1.

Methods

Forty-eight male adult albino guinea-pigs (Dunhin-Hartley strain) were used. They were purchased from a commercial dealer (Rodentia, Bergamo, Italy) and quarantined for 7 days at 22 – 24°C on a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle before use. Standard laboratory chow (Rodentia), fresh vegetables, and water were available ad libitum. The experimental protocol was designed in compliance with the recommendations of the European Economic Community (86/609/CEE) for the care and use of laboratory animals and was approved by the animal care committee of the University of Florence (Florence, Italy). At the end of the treatments, the animals weighed 350 – 400 g.

Cardiac anaphylaxis

The hearts were isolated from guinea-pigs of either sex (200 – 400 g) sensitized by intraperitoneal and subcutaneous injections of crystallized egg albumin, 100 mg kg−1 given on the same day. The hearts were taken 15 – 25 days after the sensitization. The isolated organ was perfused with Tyrode solution at 37°C in a modified Langendorff apparatus, at a constant pressure of 40 cm water and gassed with a mixture of 97% O2 3% CO2 giving a final pH of 7.42. The composition of the perfusion fluid was as follows (mM): Na+ 149.3, K+ 2.7, Ca2+ 1.8, Mg2+ 1.05, Cl− 145.4, HCO−3 11.9, H2PO−4 0.4 and (+) glucose 5.6 (Dieterich & Loffelholz, 1977).

Heart rate and contraction were recorded by means of a pressure transducer connected to a clip on the apex of the heart and recorded on a thermic writing oscillograph. The onset and type of arrhythmias were monitored by means of a bipolar surface electrogram. Coronary perfusates were collected over intervals of 5 min in graduated tubes to determine coronary flow rates and histamine release.

Cardiac anaphylaxis was elicited by injection into the aortic cannula of 0.1 ml of 1% solution of egg albumin in Tyrode solution 60 min after the beginning of the perfusion. Coronary perfusates were collected every 5 min for 30 min before and after the antigen challenge, to determine coronary flow rates and histamine content. A first group of animals were injected intraperitoneally with saline; a second group of animals received hemin at a dose of 4 mg kg−1 i.p. 18 h before antigen challenge. A third group of animals were treated with zinc protoporphyrin IX (ZnPP-IX; 50 μmol kg−1 i.p.); after 6 h they received hemin (4 mg kg−1 i.p.); after 18 h the hearts were isolated and challenged with antigen. Hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs were perfused with a solution of Tyrode gassed with 100% CO for 5 minutes and successively switched to oxygenated Tyrode for 5 min by means of a tap-controlled switch of the Langendorff apparatus. This procedure was repeated so that the total period of exposure to CO was 30 min. Hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs were also perfused with a solution of Tyrode gassed with 100% N2 with the same method used for CO to ascertain that the effect was not due to hypoxia.

Samples of cardiac tissue were collected for the detection of the activity and the expression of haeme oxygenase, histamine and total calcium content, cyclic GMP levels and mast cell densitometry.

Determination of haeme oxygenase activity

Cardiac samples were washed, homogenized and incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 50 μl of rat liver biliverdin reductase necessary to convert biliverdin to bilirubin (Llesuy & Tomaro, 1994).

The level of bilirubin was measured spectrophotometrically using a Sigma Diagnostic Procedure (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). The method is based on the reaction of total bilirubin with diazotized sulphanilic acid in the presence of dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) to give azobilirubin, which is measured spectrophotometrically at 560 nm.

Western blot analysis of haeme oxygenase 1 and 2

Cardiac samples were homogenized in 1 ml of lysis buffer of the following composition: 50 mmol l−1 HEPES, 5 mmol l−1 EDTA, 50 mmol l−1 NaCl and 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.5 containing complete protease inhibitor (Boehringer, Mannheim). Samples were kept on ice for 1 h and then centrifuged at 4°C for 30 min at 12,000×g. The precipitated insolubilized fraction was discarded and the protein concentration was determined in the supernatant by the Bradford (1976) method. The same aliquot of protein from each sample were electrophorized on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel using a Bio-Rad system. The proteins were transferred overnight into a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was probed with policlonal HO-1 and HO-2 antibodies at 1 : 1000 dilution in Tris-buffer saline, pH 7.4 for 2 h at room temperature. After three washes with PBS containing 0.05% (v v−1) tween 20, blot were visualized with the use of an amplified alkaline phosphatase kit (Motterlini et al., 1998).

Determination of histamine content

The histamine content in the hearts and in the perfusates was measured fluorimetrically by the method of Shöre et al. (1959) as modified by Lorenz et al. (1972). The authenticity of the extracted histamine was checked through the fluorescence spectra. The values of histamine release were expressed as the percentage of total ‘initial' histamine (Mongar & Schild, 1952), i.e. the ratio between histamine appearing in the perfusates and that remaining in the heart.

Calcium content

Total calcium content was determined by atomic absorption spectrometry in left ventricular samples. After washing the heart three times for 5 min with a calcium-free buffered solution, 30 mg of tissue were dried and digested overnight at 80°C with 65% HNO3. After acidification with 1 ml of HCl at 32%, the samples were dried at 45°C under nitrogen. LaCl3 was added to provide a final concentration of 1% and CaCl2 was used as a standard (Masini et al., 1997). The values were expressed as ng of calcium per mg of tissue (d.w.t.).

Evaluation of cyclic GMP

The concentration of cyclic GMP was determined by a radioimmunoassay kit 125I-cyclic GMP-RIA, in the presence of 3′-isobutil-1-methylxanthine (IBMX 50 μM) to inhibit phosphodiesterase activity (Steiner et al., 1972) added before to hemogenate the sample. The levels of cyclic GMP were measured in the aqueous phase of 5% TCA extracts of the cardiachomogenates, as described previously (Masini et al., 1994a). The values are expressed as fmol of cyclic GMP per mg of protein. The protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford (1976) method. The values reported are the means±s.e.m. of eight determinations from independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Computer-assisted densitometry of cardiac mast cells

Tissue samples were fixed by immersion in isotonic formaldehyde-acetic acid (IFAA), dehydrated in graded ethanol, and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections 5-μm thick were cut and stained with Astra blue which selectively binds heparin contained in mast cell granules. Light transmittance across mast cells, which is inversely related to their content in secretory granules, was evaluated by a computer-assisted method, as described previously (Masini et al., 1994a). The mast cells were viewed by a CCTV television camera (Sony, Tokyo, Japan) applied to a Reichert-Jung Microstar IV light microscope (Cambridge Instruments Inc, Buffalo, NY, U.S.A.) with a ×100 oil immersion objective, and interfaced with an Apple Macintosh LC III personal computer through a Videospigot card (Super-mac, Sunnyvale, CA, U.S.A.). The card allows for the light transmitted across the microscopic slide to be determined within a range of 256 grey levels, which are comprised between 0 (black level) and 255 (white level). The card also allows for a digitized image of mast cells to be reproduced on the basis of the values estimated. Measurements of transmittance were carried out using an NIH 1.49 image analysis program. The transmittance of 100 different mast cells, 10 from each animal of the different groups, was analysed and the mean transmittance value (±s.e.m.) was calculated.

Materials

Pure 100% CO and 100% N2 were obtained by gas cylinder SOL (Italia). HEPES, EDTA, from Sigma (Milano, Italia); NaCl, KCl, NH4Cl, KHCO3 were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany); bovine serum-albumin was bought from Boehring (Germany); heparin from Parke-Davis (Milano, Italia); [125I]-cyclic GMP-RIA (Amersham, Bucks, U.K.); rat liver biliverdin reductase from Stress Gen Biotech. Corp. (Canada); ZnPP-IX, protoporphyrin X zinc(II) (8,13-divinyl - 3,7,12,17 - tetramethyl -21H,23H-porphine-2,18-dipropionic acid, zinc derivative) was purchased from Aldrich Chem. Co. (Milwaukee, WI, U.S.A.).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata statistic software (release 5.0; Stata Corp., College Station, TX, U.S.A.). Comparison of two groups of data were done using unpaired-value Student's t-test. Differences between three groups of data were analysed using Kruskal Wallis test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The effect of hemin and hemin plus ZnPP-IX on cardiac HO-1 activity and expression

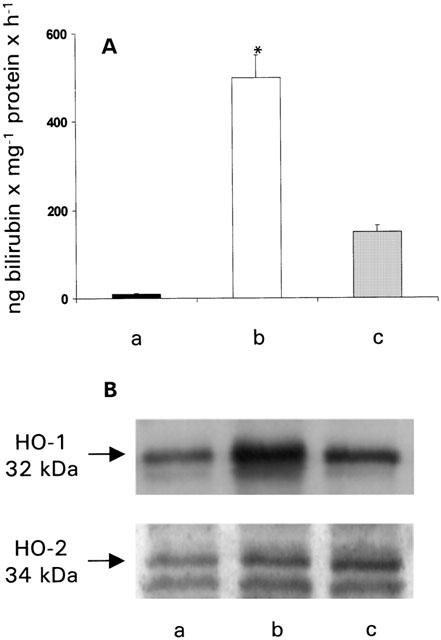

HO activity was measured by bilirubin generation in cardiac homogenates. The HO-1 inducer hemin given intraperitoneally 18 h before increased HO-1 enzymatic activity to a peak more than 13 folds above the control levels, from 42.6±13.3 ng bilirubin−1 mg protein−1 h−1 in controls to 586.7 ng bilirubin−1 mg protein−1 h−1 in hemin treated group (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Haeme oxygenase activity measured as bilirubin production and (B) HO-1 and HO-2 protein expression in control hearts (a), in hearts from animals pretreated with hemin (4 mg kg−1 i.p.) (b) and in hearts from animals pretreated with ZnPP-IX (50 μmol kg−1 i.p.), 6 h before hemin (4 mg kg−1 i.p.) (c). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of at least six experiments. *P<0.05, Kruskal Wallis test, (b) vs (a) and (c).

Pretreatment of animals with ZnPP-IX 6 before hemin injection abolished the increase in HO activity (Figure 1A).

The increase in HO activity after treatment with hemin was reflected in an increase in the inducible isoform of the protein (HO-1) in the heart as shown by Western blot analysis (Figure 1B). Consistently, the HO-1 expression was reduced in preparations from animals treated with ZnPP-IX before hemin (Figure 1B). The constitutive isoform of the protein (HO-2) was not modified after hemin treatment (Figure 1B).

The effect of HO-1 modulators on cardiac anaphylaxis

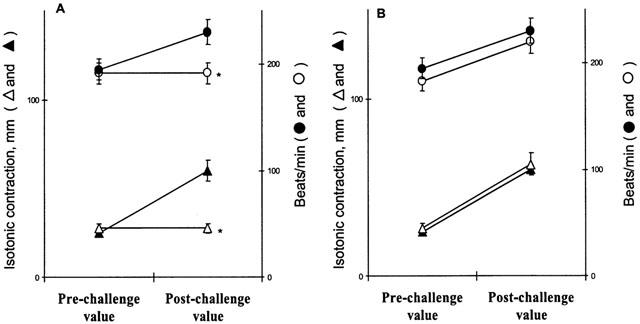

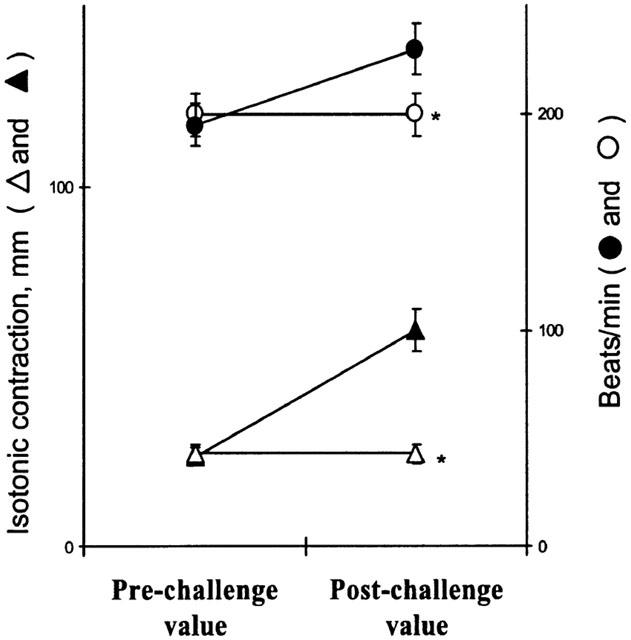

Antigen challenge of sensitized hearts from control animals resulted in a typical anaphylactic crisis, characterized by sinus tachycardia, severe arrhythmias, increase in the strength of contraction, and an initial diminution of the coronary outflow followed by a sustained coronary dilatation (Figure 2A,B; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Effect of antigen on the rate and strength of contraction 30 min after challenge, in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs (closed symbols), in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs pretreated with hemin (open symbols) (A), and in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs pretreated with ZnPP-IX prior to hemin (as reported in Figure 1) (open symbols) (B). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of at least six experiments. *P<0.05, Kruskal Wallis test, hemin vs control and ZnPP-IX.

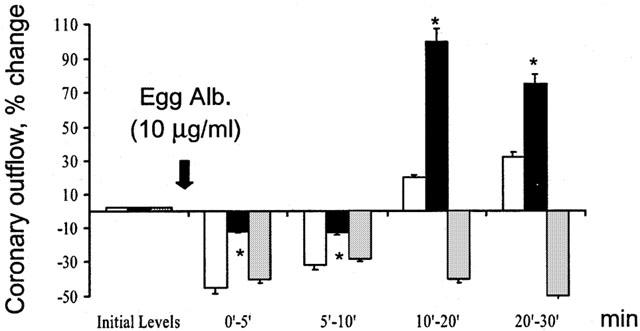

Figure 3.

Effect of antigen on the coronary outflow in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs (open columns), in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs pretreated with hemin (dark columns), and in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs pretreated with ZnPP-IX prior to hemin (as reported in Figure 1) (shaded column). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of at least six experiments. *P<0.05, Kruskal Wallis test, hemin vs control and ZnPP-IX.

Hearts from sensitized animals pretreated with hemin did not show significant changes in either rate or strength of contraction in response to antigen (Figure 2A). Antigen challenge of sensitized hearts from animals pretreated with ZnPP-IX, 6 h before hemin resulted in a complete recovery of the positive inotropic and chronotropic responses, accompanied by the same changes in the coronary outflow as in control hearts (Figure 2B and Figure 3).

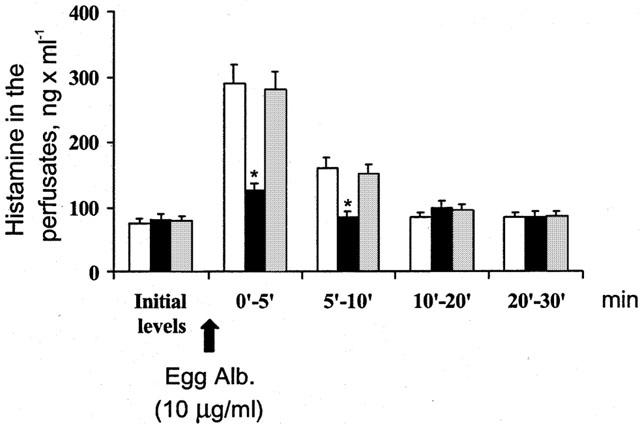

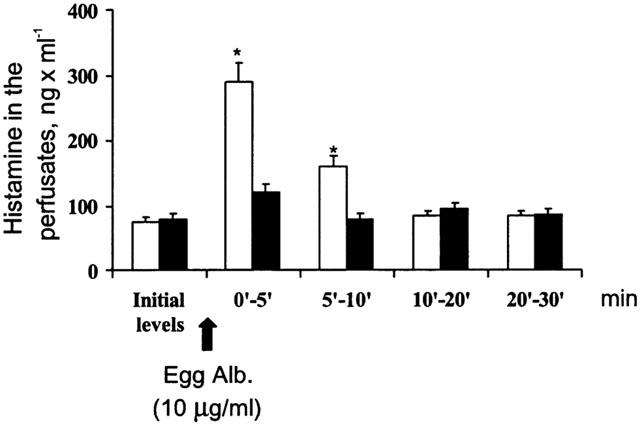

The overall histamine release was evaluated within 30 min after antigen challenge. In control experiments about 58% of the endogenous histamine was released, a similar result of previous experiments (Blandina et al., 1987). The amount of histamine appearing in the perfusates in control hearts shows a peak (297.3±24 ng ml−1) within the first 5 min after antigen challenge, followed by a significant decline (78.7±9.3 ng ml−1) at 30 min (Figure 4). In hearts from sensitized animals pretreated with hemin the amount of histamine released after exposure to antigen was significantly lower than control values especially in the first 5 min (from 297.3±24 to 112.6±8.9 ng ml−1, n=8 P<0.001) (Figure 4). In contrast, the amount of histamine released by hearts pretreated with ZnPP-IX prior to hemin was not different from that released by antigen-challenged control hearts (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The release of histamine induced by antigen in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs (open columns), in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs pretreated with hemin (dark columns) and in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs pretreated with Zn-PP-IX prior to hemin (as reported in Figure 1) (shaded column). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of at least six experiments. *P<0.05, Kruskal Wallis test, hemin vs control and ZnPP-IX.

Consistently, the amount of histamine retained in the heart after antigen challenge was near to 4 fold higher in hearts from sensitized animals pretreated with hemin (1610 ng g−1 w.w.t.) than in hearts from controls (422 ng g−1 w.w.t., n=8 P<0.001), while in hearts pretreated with ZnPP-IX prior to hemin it was comparable to control values (635 ng g−1 w.w.t.).

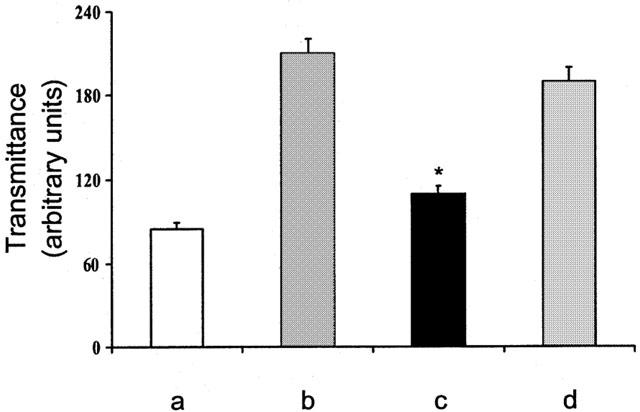

The light transmittance across mast cells, which is related to their content in secretory granules, was markedly increased in the hearts challenged with antigen in comparison to controls, showing mast cell degranulation. Conversely, in hearts from animals pretreated with hemin the light transmittance was markedly reduced showing a decrease in mast cell degranulation. When the animals were pretreated with ZnPP-IX before hemin the light transmittance increased to control values indicating the recovery of mast cells degranulation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Densitometry of mast cells from guinea-pig hearts in control animals (a), after antigen challenge in actively sensitized animals (b), after antigen challenge in actively sensitized animals pretreated with hemin (c) and after antigen challenge in animals pretreated with ZnPP-IX prior to hemin (as reported in Figure 1) (d). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of at least six experiments. *P<0.05, Kruskal Wallis test, hemin vs control and ZnPP-IX.

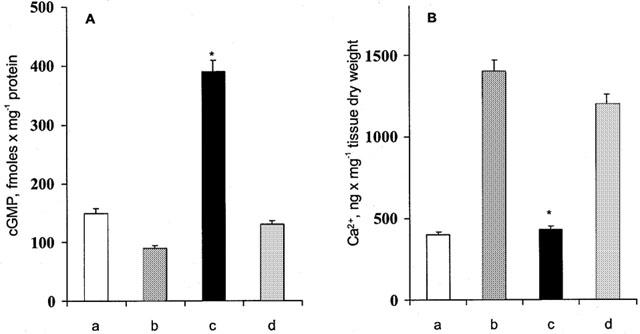

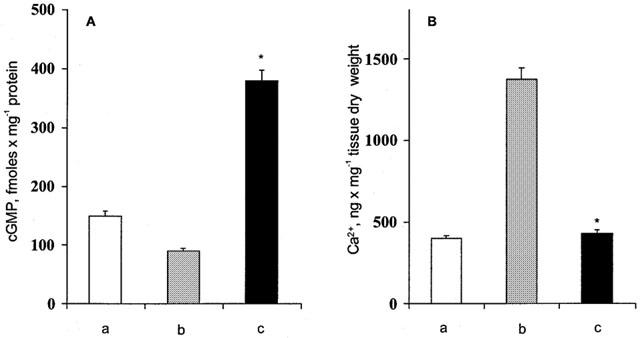

HO activity has been reported to regulate cyclic GMP levels through its product CO (Kharitonov et al., 1995). In our experiments antigen challenge produces a small diminution of cardiac cyclic GMP levels. In hearts from hemin-pretreated animals, antigen challenge is associated with a highly significant increase in cardiac cyclic GMP levels, which are reverted to control values in the heart from ZnPP-IX pretreated animals (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

(A) cyclic GMP levels in control hearts (a); after antigen challenge (b); after antigen challenge in hearts from hemin-pretreated animals (c); after antigen challenge in hearts from animals pretreated with ZnPP-IX prior to hemin (as reported in Figure 1) (d). (B) Tissue calcium levels in control hearts (a); after antigen challenge (b); after antigen challenge in hearts from hemin-pretreated animals (c); after antigen challenge in hearts from animals pretreated with ZnPP-IX prior to hemin (as reported in Figure 1) (d). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of at least six experiments. *P<0.05, Kruskal Wallis test, hemin vs control and ZnPP-IX.

It is known that cyclic GMP inhibits intracellular Ca2+ fluxes in cardiac preparations in vitro (Tohse et al., 1995) and in vivo (Liu et al., 2001) an effect which could be relevant in the modulation of the calcium-dependent secretion of histamine from cardiac mast cells (Dale & Foreman, 1984). The present experiments show that antigen challenge of sensitized hearts of control animals produces the expected increase of calcium content in myocardial tissue when compared with controls (Figure 6B).

In the hearts from animal treated with hemin, the calcium content after antigen challenge was significantly reduced (Figure 6B). In hearts from animals treated with ZnPP-IX plus hemin, the rise in tissue calcium after antigen challenge was similar to that observed in hearts from untreated animals.

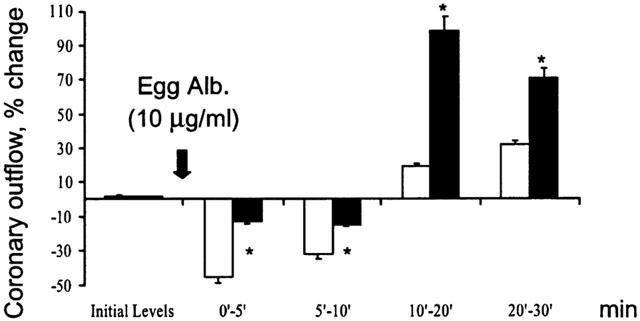

The effect of exogenous CO on cardiac anaphylaxis

Hearts from sensitized guinea-pigs were perfused for a global period of 30 min with Tyrode solution gassed with 100% CO as reported in methods. A slight decrease in rate and strength of contraction and a significant increase in the coronary outflow were observed when the hearts were returned to normal Tyrode and exposed to antigen (Figure 7). At the time of antigen challenge, the heart rate, contraction and coronary outflow did not differ from the initial values. Under these conditions exposure to antigen did not produce any significant change in heart rate and contraction (Figure 7), while producing a sustained coronary dilatation (Figure 8). Hearts from sensitized guinea-pigs perfused with Tyrode solution gassed with N2 did not show any significant change with respect to untreated hearts (data not shown). The pH of Tyrode solution never changed, while pO2 slightly decreased in a comparable manner in the solutions gassed with CO and N2.

Figure 7.

Effect of antigen on the rate and strength of contraction 30 min after challenge, in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs (closed symbols), and in hearts from sensitized guinea-pigs exposed to carbon monoxide (open symbols). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of at least six experiments. *P<0.05, Student's t-test, CO vs control.

Figure 8.

Changes in coronary outflow in response to antigen in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs (open columns) and in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs exposed to carbon monoxide (dark columns). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of at least six experiments. *P<0.05, Student's t-test, CO vs control.

The exposure to CO of sensitized hearts fully abates the amount of histamine appearing in the perfusates after antigen challenge (Figure 9). Consistently, the amount of histamine retained in the hearts previously exposed to CO was significantly higher than in untreated hearts and in N2 treated hearts (data not shown).

Figure 9.

The release of histamine induced by antigen in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs (open columns), and in hearts from actively sensitized guinea-pigs exposed to carbon monoxide (dark columns). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of at least six experiments. *P<0.05, Student's t-test, CO vs control.

In sensitized hearts exposed to CO, antigen challenge produces a highly significant increase in cardiac cyclic GMP levels (Figure 10A), while the tissue calcium contents were significantly lower than in controls (Figure 10B) and in N2 treated hearts (data not shown).

Figure 10.

(A) cyclic GMP levels in control hearts (a); after antigen challenge (b); after antigen challenge in hearts exposed to carbon monoxide (c). (B) Tissue calcium levels in control hearts (a); after antigen challenge (b); after antigen challenge in hearts exposed to carbon monoxide (c). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of at least six experiments. *P<0.05, Student's t-test, CO vs control.

Discussion

The present experiments show that pretreatment of animals with hemin, an HO-1 inducer, provides protection against cardiac anaphylaxis, in that the responses to antigen is fully abated and the release of histamine significantly reduced. The inhibitory effect is associated with an increase in cardiac cyclic GMP levels and a decrease of tissue calcium overload. This effect is fully mimicked by exogenous CO and completely antagonized by ZnPP-IX, an HO-1 inhibitor. These experiments also show that pretreatment with hemin increases the cardiac HO-1 activity and expression in a way which is timely related to the suppression of the immune responses. The increase in cardiac HO-1 activity and expression caused by hemin, was abolished by the pretreatment with ZnPP-IX.

Resident cardiac mast cells, perivascularly located and particularly concentrated in the right atrium in the vicinity of the seno-atrial node (Giotti et al., 1966) are the main repository of cardiac histamine. The heart is a target organ in systemic allergic reaction due to the exocytotic degranulation of cardiac mast cells in response to antigen challenge, leading to the release of pre-stored mediators (histamine) and to the neo-synthesis of leukotriens and chemokins (Capurro & Levi, 1975), in all producing the increase in rate and contraction, arrhythmias and changes in coronary outflow. In fact, cardiac anaphylaxis is blunted by H2-receptor blockers, such as burinamide which does not effect the release of histamine (Capurro & Levi, 1973), or by drugs that inhibit the immunological release of mediator from mast cells, such as dimaprit and imipromidine (Masini et al., 1982). We have recently shown that hemin and CO down regulate the immunological response of guinea-pig mast cells (Ndisang et al., 1999). It is, therefore, possible that the lack of response to antigen in hearts exposed to CO or from hemin pretreated animals could be accounted for by the inhibition of the immunological activation of cardiac mast cells induced by exogenous or endogenously generated CO.

The anti-anaphylactic action of hemin and of the exposure to exogenous CO could also be accounted for by different mechanisms, such as the blockade of cardiac H1/H2 receptors, or the inhibition of the secretion of histamine from repository cells due to hypoxia. Moreover, the induction by hemin of the HO-1 activity could produce, beside CO, two other catalytic by products of haeme catabolism, bilirubin and ferritin (generated by released iron) which may be capable of eliciting cytoprotection of cardiac mast cells. However, antioxidants are poorly effective in modulating histamine release (Mannaioni & Masini, 1988).

The occupancy by hemin of cardiac H1/H2 receptors is unlikely, since in the case of receptor blockade the release of histamine is expected no to be decreased (Capurro & Levi, 1973), as it is in our experiments. We cannot rule out that bilirubin and ferritin, which can function as potent anti-oxidant molecules in vitro and in vivo (Llesuy & Tomaro, 1994), could elicit mast cell cytoprotection.

However, the fact that the effect of the HO-1 inducer is mimicked by exogenous CO and is abated by the CO-administration of an HO-1 inhibitor, strongly suggests that the anti-anaphylactic effect is mostly due to the increase in the endogenous generation of CO. As far as hypoxia is concerned, it has been shown that hypoxia is a powerful inducer of HO-1 activity in endothelial cells (Siow et al., 1999).

Activation of soluble guanilyl-cyclase by CO was found to result in elevated levels of the second messenger cyclic GMP in endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells and platelets (Maines, 1997). In addition, HO-1 inducers (Middendorff et al., 2000) which increase cyclic GMP levels in guinea-pigs mast cells and human Sertoli cells (Ndisang et al., 1999). Conceivably the anti-anaphylactic effect induced by hemin and by CO could be ascribed to the concomitant increase in cardiac cyclic GMP levels. In fact, the present experiments show that the CO-mediated increase in cardiac cyclic GMP levels is associated with a decrease in tissue Ca2+ concentrations, at levels unsuitable to trigger the exocytosis of mast cell granules. The diminution of tissue calcium concentration may be due to Ca2+ sequestration by cyclic GMP (Ndisang et al., 1999). Otherwise, CO augments outward K+ current through Ca2+-dependent potassium channels producing hyperpolarization, decreasing Ca2+ channel activation and lowering cytosolic Ca2+ below the threshold of anaphylactic degranulation of mast cells (Wang & Wu, 1997).

Finally, it is conceivable that the anti-anaphylactic effect of hemin pretreatment and of exposure to CO may be due to the release of NO. In this regard, similarities between CO and NO have been recognized in a number of years (Barinaga, 1993). When vascular endothelial cells in cultures are exposed to CO, they liberate NO into the surrounding medium (Thom et al., 1997). If the same mechanism is assumed for the isolated heart of the guinea-pig the CO-induced release of NO could be accounted for by the anti-anaphylactic effect, since we have demonstrated that relaxin, an NO generator and NO donor (Masini et al., 1995) also exerts anti-anaphylactic actions in the same experimental model. Interestingly, CO augments the tissue levels of NO without changing the activity of NO-synthase, while inhibiting NO binding to haemeproteins and increasing the intracellular steady-state concentration of NO (Thom et al., 1999).

CO is a well recognized environmental toxicant. However, there is a growing body of evidence, which indicates that CO may also entail cytoprotection, especially in the heart and in the vasculature. In isolated rat hearts, perfusates equilibrated with 5% CO elicited a consistent coronary dilatation, which was not mediated by increased O2 content and by influence on receptor for catecholamines, adenosine and prostaglandin (McFaul & McGrath, 1987). A similar vasodilatatory response is observed in isolated hearts of the guinea-pigs, after hemin pretreatment and CO exposure. In isolated rat hearts made ischaemic and reperfused, L-arginine afforded significant myocardial protection, as evidenced by a decrease in malonyldialdehyde formation and lactate dehydrogenase release versus controls at the end of reperfusion. Protoporphyrin antagonizes the effect of L-arginine, suggesting a contribution of CO in addiction to NO for myocardial preservation (Maulik et al., 1996).

Oxidised low density lipoprotein, hypoxia and pro-inflammatory cytokines induce HO-1 expression and activity in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells, suggesting an atherogenic potential of the haeme oxygenase signalling pathway (Siow et al., 1999). However, exposure of rats to concentrations of CO frequently found in contaminated environments exhibits evidence of vascular oxidative injury mediated by NO-derived oxidants (Thom et al., 1999). Therefore, as in the case of NO which encompasses both cytoprotection and cell injury in the cardiovascular system (Maulik et al., 1996), the HO-1/CO signalling pathway may afford both cardioprotection and myocardial damage, presumably according to the zonal concentration.

However, the present experiments add further support to the concept that induction of HO-1 activity provides an endogenous defence mechanism against anaphylactic reactions. The design of drugs able to interfere with the endogenous generation of CO (i.e. activators or inhibitors of the HO-1 pathway) could be a new approach to the modulation of the response to antigen.

Acknowledgments

This reasearch was supported by grants of MURST and University of Florence.

Abbreviations

- cyclic GMP

cyclic guanosine 3′,5′ monophosphate

- CO

carbon monoxide

- DMSO

dimethylsulphoxide

- HEPES

ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetracetic acid N-[2-hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N′-[2-ethanesulphonic acid]

- HO

haeme oxygenase

- IBMX

3′-isobutil-1-methylxanthine

- N2

nitrogen

- OPT

ortophthaldehyde

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- PBS

phosphate buffer solution

- TCA

trichloroacetic acid

- ZnPP-IX

zinc protoporphyrin IX.

References

- BARINAGA M. Carbon monoxide: killer to brain messenger in one step. Science. 1993;259:309–310. doi: 10.1126/science.8093563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLANDINA P., BRUNELLESCHI S., FANTOZZI R., GIANNELLA E., MANNAIONI P.F., MASINI E. The antianaphylactic action of histamine H2-receptor agonists in the guinea-pig isolated heart. Br. J Pharmacol. 1987;90:459–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADFORD M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAPURRO N., LEVI R. Anaphylaxis in the guinea-pig isolated heart: selective inhibition by burimamide of the positive inotropic and chronotropic effects of released histamine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1973;48:620–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1973.tb08249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAPURRO N., LEVI R. The heart as a target organ in systemic allergic reactions: comparison of cardiac analphylaxis in vivo and in vitro. Circ. Res. 1975;36:520–528. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CESARIS-DEMEL A. Sur le mode de sé comporter du coeur isolé d'animaux sensibilisés. Arch. It. Biol. 1910;54:141–152. [Google Scholar]

- DALE M.M., FOREMAN J.C. Textbook of immunopharmacology. 1984.

- DIETERICH H.A., LOFFELHOLZ K. Effect of coronary perfusion rate on the hydrolysis of exogenous and endogenous acetylcholine in the isolated heart. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1977;296:143–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00508466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUJITA T., TODA K., KARIMOVA A., YAN S.F., NAKA Y., YET S.F., PINSKY D.J. Paradoxical rescue from ischemic lung injury by inhaled carbon monoxide driven by derepression of fibrinolysis. Nat. Med. 2001;7:598–604. doi: 10.1038/87929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIOTTI A., GUIDOTTI A., MANNAIONI P.F., ZILLETTI L. The influences of andrenotropic drugs and noradrenaline on the histamine release in cardiac anaphylaxis in vitro. J. Physiol. 1966;184:924–941. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KHARITONOV V.G., SHARMA V.S., PILZ R.B., MAGDE D., KOESLING D. Basis of guanylate cyclase activation by carbon monoxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:2568–2571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU H., SONG D., LEE S.S. Role of heme oxygenase-carbon monoxide pathway in pathogenesis of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G68–G74. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.1.G68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LLESUY S.F., TOMARO M.L. Heme oxygenase and oxidative stress. Evidence of involvement of bilirubin as physiological protector against oxidative damage. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1223:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LORENZ W., REIMANN H.J., BARTH H., KUSCHE J., MEYER R., DOENICKE A., HUTZEL M. A sensitive and specific method for the determination of histamine in human whole blood and plasma. Hoppe Seylers. Z. Physiol. Chem. 1972;353:911–920. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1972.353.1.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAINES M.D. The heme oxygenase system: a regulator of second messenger gases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1997;37:517–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANNAIONI P.F., MASINI E. The release of histamine by free radicals. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1988;5:177–197. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASINI E., BANI D., BELLO M.G., BIGAZZI M., MANNAIONI P.F., SACCHI T.B. Relaxin counteracts myocardial damage induced by ischemia-reperfusion in isolated guinea pig hearts: evidence for an involvement of nitric oxide. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4713–4720. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.11.5520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASINI E., BANI D., BIGAZZI M., MANNAIONI P.F., BANI-SACCHI T. Effects of relaxin on mast cells. In vitro and in vivo studies in rats and guinea pigs. J. Clin. Invest. 1994a;94:1974–1980. doi: 10.1172/JCI117549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASINI E., BLANDINA P., MANNAIONI P.F. Mast cell receptors controlling histamine release: influences on the mode of action of drugs used in the treatment of adverse drug reactions. Klin. Wochenschr. 1982;60:1031–1038. doi: 10.1007/BF01716967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASINI E., DI BELLO M.G., PISTELLI A., RASPANTI S., GAMBASSI F., MUGNAI L., LUPINI M., MANNAIONI P.F. Generation of nitric oxide from nitrovasodilators modulates the release of histamine from mast cells. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1994b;45:41–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASINI E., GAMBASSI F., DI BELLO M.G., MUGNAI L., RASPANTI S., MANNAIONI P.F.Nitric oxide modulates cardiac and mast cell anaphylaxis Agents Actions 1994c41C89–C90.Spec No [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASINI E., LUPINI M., MUGNAI L., RASPANTI S., MANNAIONI P.F. Polydeoxyribonucleotides and nitric oxide release from guinea-pig hearts during ischaemia and reperfusion. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:629–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAULIK N., ENGELMAN D.T., WATANABE M., ENGELMAN R.M., ROUSOU J.A., FLACK J.E., DEATON D.W., GORBUNOV N.V., ELSAYED N.M., KAGAN V.E., DAS D.K. Nitric oxide/carbon monoxide. A molecular switch for myocardial preservation during ischemia. Circulation. 1996;94:II398–II406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCFAUL S.J., MCGRATH J.J. Studies on the mechanism of carbon monoxide- induced vasodilation in the isolated perfused rat heart. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1987;87:464–473. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(87)90252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIDDENDORFF R., KUMM M., DAVIDOFF M.S., HOLSTEIN A.F., MULLER D. Generation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate by heme oxygenases in the human testis-a regulatory role for carbon monoxide in Sertoli cells. Biol. Reprod. 2000;63:651–657. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.2.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIRABELLA C., NDISANG J.F., BERNI L.A., GAI P., MASINI E., MANNAIONI P.F. Modulation of the immunological activation of human basophils by carbon monoxide. Inflamm. Res. 1999;48 Suppl 1:S11–S12. doi: 10.1007/s000110050373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONGAR J.L., SCHILD H.O. A comparison of the effects of anaphylactic shock and chemical histamine releasers. J. Physiol. 1952;118:461–478. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOTTERLINI R., GONZALES A., FORESTI R., CLARK J.E., GREEN C.J., WINSLOW R.M. Heme oxygenase-1-derived carbon monoxide contributes to the suppression of acute hypertensive responses in vivo. Circ. Res. 1998;83:568–577. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.5.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NDISANG J.F., GAI P., BERNI L., MIRABELLA C., BARONTI R., MANNAIONI P.F., MASINI E. Modulation of the immunological response of guinea pig mast cells by carbon monoxide. Immunopharmacology. 1999;43:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARMA H.S., DAS D.K., VERDOUW P.D. Enhanced expression and localization of heme oxygenase-1 during recovery phase of porcine stunned myocardium. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1999;196:133–139. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5097-6_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHÖRE P.A., BURKHALTER A., COHN V.A. A method for the flurimetric assay of histamine in tissues. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1959;127:182–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIOW R.C., SATO H., MANN G.E. Heme oxygenase-carbon monoxide signalling pathway in atherosclerosis: anti-atherogenic actions of bilirubin and carbon monoxide. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;41:385–394. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINER A.L., PARKER C.W., KIPNIS D.M. Radioimmunoassay for cyclic nucleotides. I. Preparation of antibodies and iodinated cyclic nucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247:1106–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOM S.R., FISHER D., XU Y.A., GARNER S., ISCHIROPOULOS H. Role of nitric oxide-derived oxidants in vascular injury from carbon monoxide in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:H984–H992. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.3.H984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOM S.R., XU Y.A., ISCHIROPOULOS H. Vascular endothelial cells generate peroxynitrite in response to carbon monoxide exposure. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997;10:1023–1031. doi: 10.1021/tx970041h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOHSE N., NAKAYA H., TAKEDA Y., KANNO M. Cyclic GMP-mediated inhibition of L-type Ca2+channel activity by human natriuretic peptide in rabbit heart cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:1076–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG R., WU L. The chemical modification of KCa channels by carbon monoxide in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:8222–8226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEILER J.M. Anaphylaxis in the general population: A frequent and occasionally fatal disorder that is underrecognized. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999;104:271–273. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOCUM M.W., BUTTERFIELD J.H., KLEIN J.S., VOLCHECK G.W., SCHROEDER D.R., SILVERSTEIN M.D. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis in Olmsted County: A population-based study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999;104:452–456. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]