Abstract

Inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) improves symptoms and prognosis in heart failure. The experimental basis for these benefits remains unclear. We examined the effects of inhibition of ACE or blockade of angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor on the haemodynamics, cardiac G-proteins, and collagen synthesis of rats with coronary artery ligation (CAL), a model in which chronic heart failure (CHF) is induced.

Rats were orally treated with the ACE inhibitor trandolapril (3 mg kg−1 day−1) or the AT1 receptor blocker L-158809 (1 mg kg−1 day−1) from the 2nd to 8th week after CAL. CAL resulted in decreases in the left ventricular systolic pressure and its positive and negative dP/dt, an increase in the left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, and the rightward shift of the left ventricular pressure-volume curve. Long-term treatment with either drug improved these signs of CHF to a similar degree.

Cardiac Gsα and Gqα protein levels decreased, whereas the level of Giα protein increased in the animals with CHF. Long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 attenuated the increase in the level of cardiac Giα protein of the animals with CHF without affecting Gsα and Gqα protein levels. Cardiac collagen content of the failing heart increased, whose increase was blocked by treatment with either drug.

Exogenous angiotensin I stimulated collagen synthesis in cultured cardiac fibroblasts, whose stimulation was attenuated by either drug.

These results suggest that blockade of the RAS, at either the receptor level or the synthetic enzyme level, may attenuate the cardiac fibrosis that occurs after CAL and thus affect the remodelling of the failing heart.

Keywords: Cardiac fibrosis, collagen, G proteins, L-158809, trandolapril

Introduction

One of the major mechanisms for reduced cardiac performance in chronic heart failure (CHF) is attributed to activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) (Francis et al., 1993; Middlekauff, 1997). Recent evidence suggests that the RAS exerts its influence not only through its circulating components (the endocrine RAS) but also through several paracrine RAS components localized in the brain, heart, blood vessels, and adrenals (Lindpaintner & Ganten, 1991). The circulating RAS is known to play an important role in the control of electrolyte balance, blood fluid volume, and arterial blood pressure. On the other hand, the local RAS affects the progression of atherosclerotic lesions, the phenomenon of restenosis, the accumulation of connective tissue, and the process of remodelling in heart failure (Stock et al., 1995). Thus, activation of the RAS is profoundly involved in the pathophysiology of heart failure.

G proteins play a critical role in the regulation of receptor-mediated signal transduction in cardiac cells. In cardiomyocytes, the β-adrenoceptor couples via Gsα with the adenylate cyclase to increase the intracellular level of cyclic AMP, eventuating in positive inotropic action (Trautwein & Hescheler, 1990). The AT1 receptor couples via Gqα and Giα with phospholipase C-β (PLC-β) to increase the intracellular IP3 and diacylglycerol levels, which leads to cell proliferation and myocyte hypertrophy through further downstream signalling mechanisms (Sadoshima et al., 1995). On the other hand, AT1 receptor of cardiac fibroblasts is coupled with Giα to produce cell proliferation (Zou et al., 1998). Several reports have shown alterations in cardiac membrane G proteins of animals in the pathophysiological state. For example, Peterson et al. (1999) showed a marked increase in the expression and content of Gsα and Giα in the myofibroblasts of the infarct scar and remnant cardiomyocytes bordering the scar in the rat heart 8 weeks after myocardial infarction. Furthermore, Gi2α protein concomitantly increased in an experimental model of heart failure (Shi et al., 1995). In addition, Ju et al. (1998) showed the upregulation of the cardiac Gqα/PLC-β pathway in the infarct scar, as well as in the remnant cardiomyocytes bordering the scar in the rat heart 8 weeks after myocardial infarction. Since angiotensin II receptors exist in the cardiac membrane, ACE inhibitors or AT1 receptor blockers may possibly affect G proteins in the membrane. In fact, effects of ACE inhibitors on the alteration in membrane G proteins have been observed. For example, Böhm et al. (1998) showed increases in Giα proteins and their mRNA in TG(mREN2)27 rats, a model with renin-induced hypertension, which increases were partially reversed by treatment with an ACE inhibitor and AT1 receptor blocker. Also, the effect of chronic therapy with ACE inhibitor on alterations in cardiac membrane G proteins in patients with heart failure was demonstrated (Jakob et al., 1995). However, the effects of angiotensin II on changes in G proteins of the failing heart in vivo have not been elucidated. Trandolapril, an ACE inhibitor, and L-158809, an AT1 receptor blocker, were used in the present study. Both trandolapril and L-158809 have been shown to improve cardiac dysfunction of animals with chronic heart failure following myocardial infarction by us (Sanbe & Takeo, 1995) and others (Liu et al., 1997).

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (SLC, Hamamatsu, Japan), weighing 220 – 240 g, were used in the present study. The animals were maintained at 23±1°C with a constant humidity of 55±5% and a cycle of 12 h of light and 12 h of dark, and had free access to food and tap water according to the Guidelines of Experimental Animal Care issued by Prime Minister's Office of Japan, in accordance with The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as Promulgated by the National Research Council. The protocol of the study was approved by the Animal Care Committee of Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Science.

Induction of myocardial infarction

Myocardial infarction was produced in rats by occlusion of the left coronary artery at approximately 2 mm from its origin according to the method described previously (Sanbe et al., 1993). We employed two elimination criteria to perform pharmacological examination. Two weeks after the operation, the electric cardiogram is measured as described in the text. When negative Q wave is more than 0.3 mV, we can confirm that infarct area exists on the left ventricular free wall. The other is a change in body weight of the operated animal at the second week. Animals that showed an increase in the body weight at the 2nd week to be more than 10 g are eliminated from pharmacological evaluation. Using these elimination criteria, we can constantly produce CAL rats with approximately 40% infarct area in the left ventricle. Sixty rats had received the operation. Eleven rats died within 24 h and four within 1 week after the operation (25%). Among the remaining 45 CAL rats, nine CAL rats were eliminated from the present study according to the criteria described above (15%). Accordingly, 36 animals were used for the following studies. Sham-operated rats were treated similarly except that the coronary artery ligation was not performed. Thirty-six sham-operated rats without CAL were treated similarly. Using these animals, we assessed the chronic effects of the ACE inhibitor and AT1 blocker.

In a previous study (Sanbe et al., 1993), our laboratory has shown decreases in LVSP and dP/dt, an increase in LVEDP, and a decrease in the cardiac output index in this model by 8 weeks after CAL, indicating that heart failure with low cardiac output had developed by that time.

Treatment with ACE inhibitor or AT1 receptor blocker

Treatment of the CAL rats with 3 mg kg−1 day−1 of trandolapril once a day or 1 mg kg−1 day−1 of L-158809 once a day was performed from 2 – 8 weeks after the operation. Trandolapril was suspended in 0.25% carboxymethylcellulose sodium for oral administration to the rats. L-158809 was dissolved in water and orally administered. The doses employed in the present study were based on the effective doses of these agents for the therapy of heart failure in previous studies (Sanbe & Takeo, 1995; Liu et al., 1997).

Measurements of haemodynamic parameters and histological study

Eight weeks after the operation, the rats were anaesthetized with nitrous oxide/oxygen (3 : 1) and 2.5% enflurane. Anaesthesia was continued with a gas mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen (3 : 1) containing 0.5% enflurane at the flow rate of 1.2 l min−1 through a mask loosely placed on the nose. The pO2, pCO2, and pH of the arterial blood under the present experimental conditions were monitored by a blood gas analyzer (model 248, Chiron, Japan), and these values were found to be within physiological ranges: pO2, 90 – 108 mmHg; pCO2, 37 – 41 mmHg; and pH, 7.41 – 7.46. Haemodynamic parameters were measured as described previously (Sanbe et al., 1993).

After measurement of the haemodynamic parameters, the heart was isolated and sectioned into seven slices (1-mm thick) from the base to apex in a plane parallel to the artrioventricular groove. The slices were stained at 37°C for 5 min with 1% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) in physiological saline, and the infarct areas were estimated according to the planimetric method (Fletcher et al., 1981).

Measurement of pressure-volume relation

The left ventricular pressure-volume relationship curve was obtained by the method previously described (Yoshida et al., 2001). Chamber stiffness constant was calculated from four segments: K1 (0 – 2.5 mmHg), K2 (2.5 – 10 mmHg), K3 (10 – 20 mmHg), and K4 (20 – 30 mmHg) as described previously (Fletcher et al., 1981). K1 was determined from the slope of the linear portion of the pressure-volume curve. Other constants were calculated from the following equation (Fletcher et al., 1981): P=a*exp(K*V), where K means K2, K3, and K4. Left ventricular end-diastolic volume index (LVEDVI) was determined from the pressure-volume curve as a volume corresponding to the LVEDP measured in vivo.

Membrane preparations from whole hearts and Western blotting

Myocardial membranes were prepared from the left ventricle, septum, right ventricle, and infarct area according to a modification of McMahon's method (1989). The tissue was frozen in liquid nitrogen and then homogenized with a mortar and pestle. The homogenate was placed into five volumes of cold buffer (20 mM HEPES, 0.3 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EGTA; pH 7.40), and then rehomogenized with a Potter homogenizer at a setting of 1000 r.p.m. for 2 min (20 strokes). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1000×g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant fluid was recentrifuged at 100,000×g at 4°C for 20 min. The supernatant fluid after centrifugation was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in the above buffer to a protein concentration of 0.5 mg ml−1. The protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (1976) with bovine serum albumin used as the standard. The membrane preparations were stored at −80°C until assayed.

Western blotting analysis of G proteins was performed as described previously (Yoshida et al., 2001). Five micrograms of membrane proteins were electrophoresed through a 10% sodium dodecylsulphate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel. For the Western blotting assay, the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon, Millipore Co., Bedford, MA, U.S.A.). The membranes for analysis of Gsα, Gi1,2α, Gi3α, and Gqα were then incubated with a 1 : 10,000 dilution of antibody RM/1, a 1 : 10,000 dilution of antibody AS/7, a 1 : 5000 dilution of antibody EC/2, and a 1 : 10,000 dilution of QL (NEN™ Life Science Products, Inc.) (Anand-Srivastava, 1992), respectively, in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% Block Ace (Dainippon Pharm., Japan) and 0.1% Tween 20. The membranes were subsequently washed in PBS containing 10% Block Ace and 0.1% Tween 20, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG1 (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, U.S.A.) at a dilution of 1 : 4000 in PBS containing 10% Block Ace and 0.1% Tween 20. Finally, the membranes were washed three times with PBS for 10 min and placed in the enhanced chemiluminescence immunoblotting detection reagent (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, U.K.). The blots were finally exposed to X-ray film. Scanning of visualized immunoreactivity was performed on a Scanner (ES-2000, EPSON, Japan). Data were processed with an NIH image software.

Measurement of collagen content

Tissue collagen content was measured with a collagen staining kit (Cosmo Bio Co., Tokyo, Japan) according to a modification of the method of Lopez-De Leon & Rojkind (1985). The tissue was frozen in liquid nitrogen and then homogenized with a mortar and pestle. Ten milligrams of the homogenate was placed into 1 ml of 0.6 mol l−1 PCA and then centrifuged at 10,000×g at room temperature for 3 min. The resultant pellet was washed and neutralized with 1 ml of PBS. The pellet was next incubated for 30 min at room temperature with a dye solution including 0.1% Sirius red F3BA and 0.1% Fast green FCF. Then the fluid was centrifuged at 10,000×g at room temperature for 3 min. The resultant pellet was washed with distilled water until the fluid was colourless. One millilitre of 0.1 mol l−1 NaOH in 50% methanol was then added and gently mixed until all the colour was eluted from the tissue. The intensity of the eluted colour was determined by a spectrophotometer at 540 (Sirius red F3BA) and 605 nm (Fast green FCF).

Experimental sequence and number of animals used

We used 36 CAL rats for the present study. The CAL rats were divided into three groups: drug-untreated, trandolapril-treated, and L-158809-treated groups. At the 8th week after CAL, the haemodynamics of the operated animals of the three groups were determined and thereafter the myocardial G proteins were measured (n=6 each). In another set of experiments, the pressure-volume relationship of the three groups was determined, and then the infarct areas were measured. Thereafter, the myocardial collagen content of the three groups was determined (n=6 each). TTC used for the staining did not interfere with the determination of myocardial collagen content.

Cell culture and analysis of collagen synthesis

Primary culture of adult rat ventricular nonmyocytes was performed according to a modified method of Maki et al. (2000). Briefly, after anaesthetization with 40 mg kg−1 sodium pentobarbitone i.p., apical halves of cardiac ventricles from Wistar rats (150 – 200 g) were separated and minced in ice-cold balanced salt solution (mM): NaCl 116, HEPES 20, NaH2PO4 12.5, glucose 5.6, KCl 5.4, and MgSO4 0.8; pH 7.35. Ventricular cardiomyocytes were dispersed in the balanced salt solution containing 0.08% collagenase type II with agitation for 6 min at 37°C. The digestion step was repeated seven to eight times until the tissue was completely digested. The cells were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) and plated onto gelatin-coated 10-cm culture dishes for 2 h. Nonadherent cells and debris were then washed away, and fresh medium was added. Cells were allowed to grow to confluence and were then trypsinized and passaged at a 1 : 3 dilution. This procedure yielded cultures of cells that were almost exclusively cardiac fibroblasts obtained by the first passage (Villarreal et al., 1993). Nonmyocytes at the second passage were plated at a density of 2.5×104 cells/well onto 24-well plates and allowed to grow to confluence.

The effects of various agents on collagen synthesis in the cardiac fibroblasts were evaluated by the incorporation of [3H]-proline into the cells by the methods described previously (Maki et al., 2000). After incubation in DMEM with FBS, nonmyocytes were maintained in serum-free DMEM for 24 h. After this preconditioning period, the culture medium was replaced with fresh serum-free DMEM. Then angiotensin I, angiotensin II, trandolaprilat, an active form of trandolapril, and/or L-158809 were added. [3H]-proline was also added at 0.5 μCi ml−1, and then the plates were incubated for 24 h. After labelling, the cells were rinsed twice with cold PBS and incubated with 10% trichloroacetic acid at 4°C for 30 min. The precipitates were washed twice with cold 95% ethanol and solubilized in 1 M NaOH. The radioactivity of aliquots of the trichloroacetic acid-insoluble material was determined by using a liquid scintillation counter.

Statistics

The results were expressed as the means±s.e.mean. The numbers of different preparations are indicated in the legends. Statistical significance of differences in haemodynamics, LVEDVI, left ventricular chamber stiffness, G proteins, and collagen content were estimated by using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher's PLSD multiple comparison. Statistical significance of the pressure-volume relation was estimated by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, and that of the [3H]-proline uptake, by one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher's PLSD multiple comparison. Differences with a probability of 5% or less were considered to be statistically significant (P<0.05).

Results

Effects of ACE inhibition or AT1 receptor blockade on body weight, heart weight, and lung weight

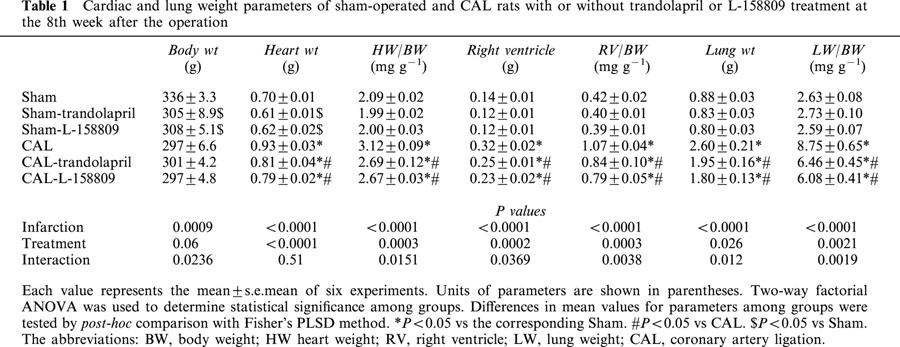

The effects of long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 on body weight, heart weight, and lung weight of coronary artery-ligated rats and sham-operated rats at the 8th week after the operation are shown in Table 1. Body weight significantly decreased in trandolapril- or L-158809-treated, sham-operated rats, whereas the body weights of CAL rats did not differ from those of trandolapril- or L-158809-treated CAL rats. Heart weight, heart weight-to-body weight, right ventricle, right ventricle-to-body weight, lung weight, and lung weight-to-body weight were significantly increased in the CAL group compared with those of the sham-operated group. Chronic treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 significantly attenuated the increases in the heart and lung weight and the heart and lung weight-to-body weight ratio.

Table 1.

Cardiac and lung weight parameters of sham-operated and CAL rats with or without trandolapril or L-158809 treatment at the 8th week after the operation

Effects of ACE inhibition or AT1 receptor blockade on LV haemodynamics

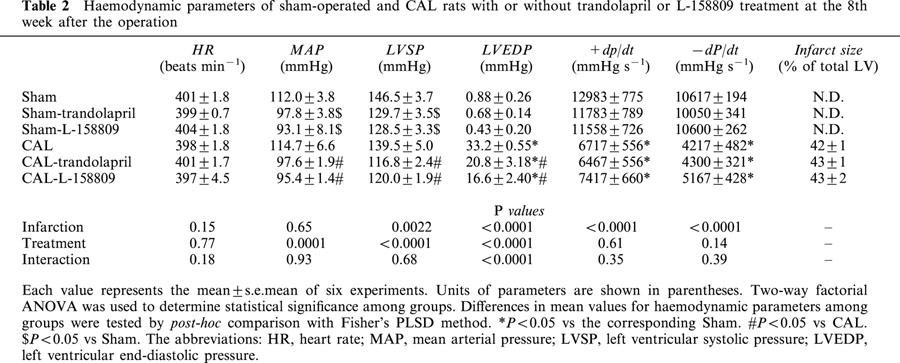

Next we compared the effects of ACE inhibition or AT1 receptor blockade on cardiac and haemodynamic parameters (Table 2). We assessed the effects of long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 on the changes in heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP), left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), and ±dP/dt at 8 weeks after CAL. Neither CAL nor treatment with the drug affected HR. MAP and LVSP of the trandolapril- or L-158809-treated animal significantly decreased, an effect that was independent of myocardial infarction. LVEDP was markedly increased after CAL. Chronic treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 significantly attenuated this increase in LVEDP. The decrease in ±dP/dt was not affected by treatment with trandolapril or L-158809. Treatment with either agent resulted in a similar reduction in blood pressure. Also there were no differences in the infarct size of CAL rats irrespective of treatment or not with ACE inhibitor or AT1 receptor blocker.

Table 2.

Haemodynamic parameters of sham-operated and CAL rats with or without trandolapril or L-158809 treatment at the 8th week after the operation

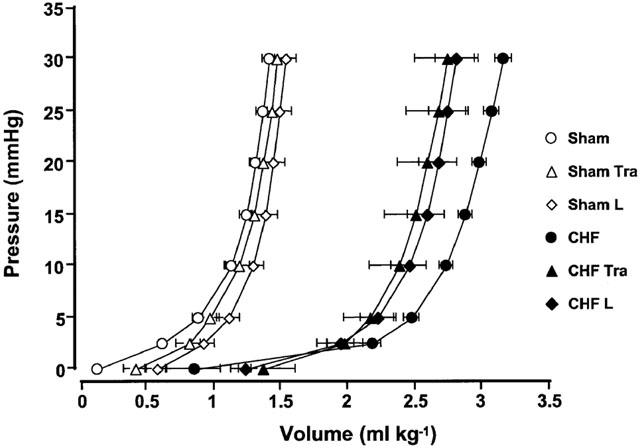

Effects of ACE inhibition or AT1 receptor blockade on pressure-volume relations

Ventricular volumes measured at transmural pressures from 2.5 – 30 mmHg were significantly increased in the potassium-arrested heart of the rats with CAL (Figure 1). The substantial volume in the rats with CAL was increased at each pressure. Chronic treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 significantly attenuated the increase in left ventricular volume at each pressure. The LV chamber stiffness constants, indices of ventricular stiffness, are summarized in Table 3. K0, K1, K2, K3, and K4 values significantly decreased in the CAL group, and treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 tended to attenuate the decrease in these constants. LVEDVI was calculated from LVEDP and the pressure-volume curve, which is an index of LV chamber volume in the diastolic stage in vivo. LVEDVI significantly increased with the rightward shift of pressure-volume curve (Figure 1). LVEDVI values in the sham and CAL groups were 0.37±0.06 ml kg−1 and 3.21±0.20 ml kg−1, respectively, and this difference was statistically significant (P<0.05). The increase in LVEDVI values was significantly attenuated by treatment with trandolapril (2.62±0.15 ml kg−1) or L-158809 (2.61±0.18 ml kg−1), respectively. There was no difference in LVEDVI of the sham-operated rats irrespective of treatment or not with the ACE inhibitor or AT1 receptor blocker.

Figure 1.

The left ventricular pressure-volume relationship in sham-operated rats (open symbols) and in rats with CHF (closed symbols) untreated (circles) and treated with either trandolapril (Tra; triangles) or L-158809 (L; diamonds). Eight weeks after surgery, the pressure-volume relationship had progressively shifted to the right in rats with CHF. Both treatments attenuated the rightward shift of this relationship. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of six experiments.

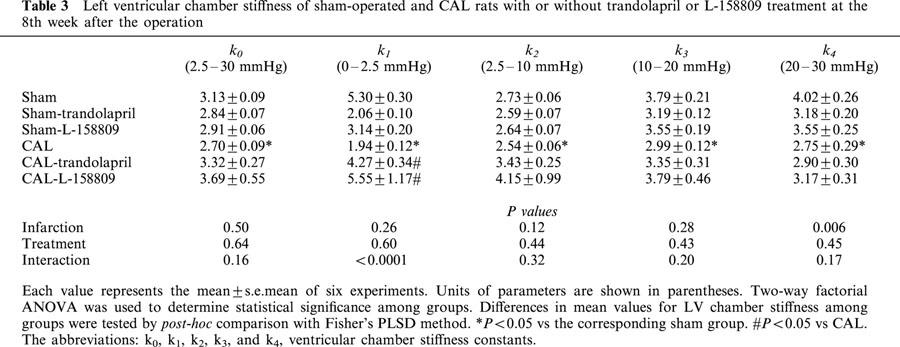

Table 3.

Left ventricular chamber stiffness of sham-operated and CAL rats with or without trandolapril or L-158809 treatment at the 8th week after the operation

Effects of ACE inhibition or AT1 receptor blockade on Gsα, Giα, and Gqα proteins

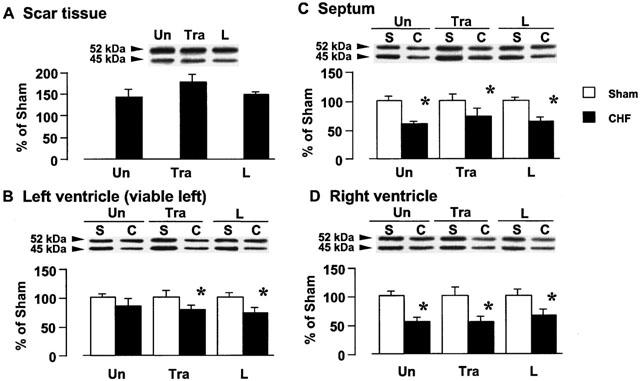

The sum of the 45- and 52-kDa peptides, identified as Gsα protein, were detected by using the Gsα antibody, as shown in Figure 2. Figure 2A,B,C,D show the tissue Gsα protein content in the scar tissue, left ventricle, septum, and right ventricle, respectively. In the rats with CHF, Gsα protein in the scar tissue increased by approximately 1.4 fold as compared with that in the left ventricle of the sham animal. There was no change in tissue Gsα protein in the viable left ventricle of the rats with CHF, but tissue Gsα protein in the septum and right ventricle were decreased by the CAL. Gsα protein content of the sham-operated rats and rats with CHF was not affected by long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809.

Figure 2.

Effects of trandolapril (Tra) and L-158809 (L) on Gsα in the membrane fraction from the ventricular tissue of sham-operated rats (open columns) and rats with CHF (closed columns). Representative Western blots indicate specific 52- and 45-kDa bands for Gsα in the membrane fraction from the scar tissue (A), left ventricle (B), septum (C), and right ventricle (D), respectively. ‘Un' indicates animals without drug-treatment. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of six experiments. *Significantly different from the corresponding sham-operated group (P<0.05).

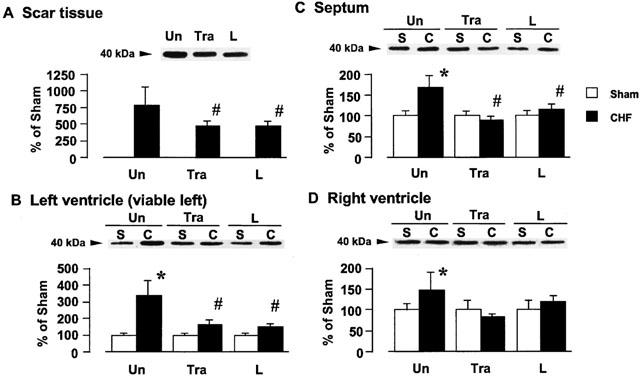

A band migrating at 40 kDa, identified as Gi1,2α protein, was detected by using the Gi1,2α antibody, as shown in Figure 3. Figure 3A,B,C,D show the tissue Gi1,2α protein content in the scar tissue, left ventricle, septum, and right ventricle, respectively, of the rats with CHF. The tissue Gi1,2α protein content increased by approximately 7.9, 3.4, 1.7, and 1.5 fold in the scar, viable left ventricle, septum, and right ventricle, respectively, as compared with that of the corresponding tissues of the sham-operated rats. Long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 significantly attenuated the increase in the cardiac Gi1,2α protein content of the rats with CHF, whereas it did not affect the Gi1,2α protein content of sham-operated rats.

Figure 3.

Effects of trandolapril (Tra) and L-158809 (L) on Gi1,2α in the membrane fraction from the ventricular tissue of sham-operated rats (open columns) and rats with CHF (closed columns). Representative Western blots indicate specific 40 kDa band for Gi1,2α in the membrane fraction from the scar tissue (A), left ventricle (B), septum (C), and right ventricle (D), respectively. ‘Un' indicates animals without drug-treatment. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of six experiments. *Significantly different from the corresponding sham-operated group (P<0.05). #Significantly different from the untreated CHF group (P<0.05).

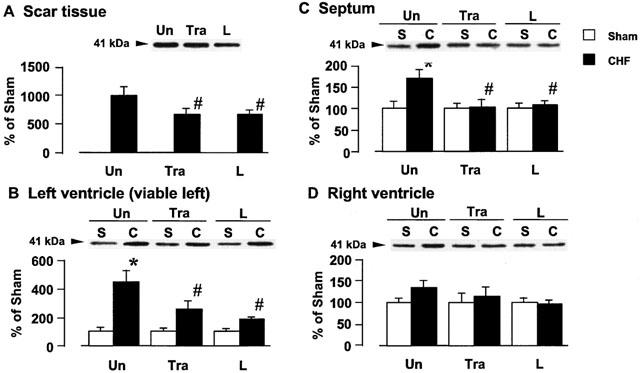

A band migrating at 41 kDa, identified as Gi3α protein, was detected with Gi3α antibody, as shown in Figure 4. Figure 4A,B,C,D show the tissue Gi3α protein content in the scar tissue, left ventricle, septum, and right ventricle, respectively, of the rats with CHF. Cardiac Gi3α increased by approximately 9.9, 4.4, 1.7, and 1.4 fold in the scar, viable left ventricle, septum, and right ventricle, respectively, as compared with the level in the corresponding tissues of the sham-operated rats. Long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 significantly attenuated the increase in the Gi3α protein content, whereas it did not affect the Gi3α protein content of sham-operated rats.

Figure 4.

Effects of trandolapril (Tra) and L-158809 (L) on Gi3α in the membrane fraction from the ventricular tissue of sham-operated rats (open columns) and rats with CHF (closed columns). Representative Western blots indicate specific 41 kDa band for Gi3α in the membrane fraction from the scar tissue (A), left ventricle (B), septum (C), and right ventricle (D), respectively. ‘Un' indicates animals without drug-treatment. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of six experiments. *Significantly different from the corresponding sham-operated group (P<0.05). #Significantly different from the untreated CHF group (P<0.05).

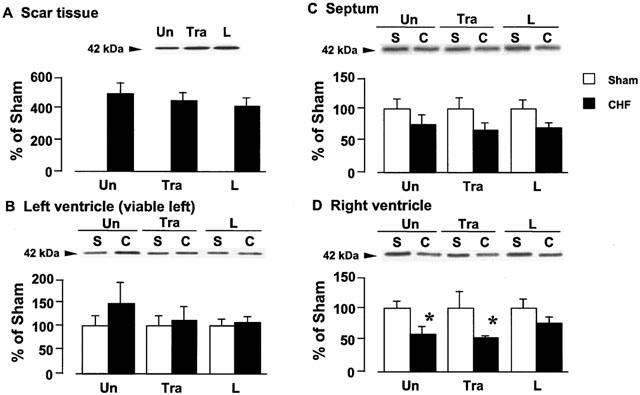

Figure 5 shows a band migrating at 42 kDa, identified as Gqα protein, which was detected with Gqα antibody. Figure 5A, B, C, and D show tissue Gqα protein content in the scar tissue, left ventricle, septum, and right ventricle, respectively, of the rats with CHF. In the rats with CHF, Gqα protein in the scar tissue increased by approximately 5.4 fold as compared with that in the left ventricle of the sham-operated animal. There was no change in the tissue Gqα protein in the viable left ventricle of the rats with CHF, but tissue Gqα protein in the septum and right ventricle decreased or tended to decrease. Long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 did not affect the decrease in the Gqα protein content in the septum and right ventricle of the rats with CHF, nor did it affect the content in the sham-operated rats.

Figure 5.

Effects of trandolapril (Tra) and L-158809 (L) on Gqα in the membrane fraction from the ventricular tissue of sham-operated rats (open columns) and rats with CHF (closed columns). Representative Western blots indicate specific 42 kDa band for Gqα in the membrane fraction from the scar tissue (A), left ventricle (B), septum (C), and right ventricle (D), respectively. ‘Un' indicates animals without drug-treatment. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of six experiments. *Significantly different from the corresponding sham-operated group (P<0.05).

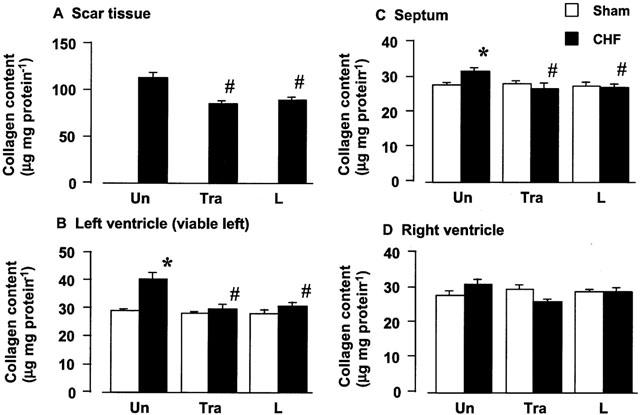

Effects of ACE inhibition or AT1 receptor blockade on cardiac collagen content

The cardiac collagen content is shown in Figure 6. In the sham-operated rats, cardiac collagen content did not differ among the left ventricle, septum, and right ventricle. Long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 did not affect the collagen content of sham-operated rats. A marked increase in the collagen content in the scar tissue was seen in comparison with the content in the sham left ventricle, and a significant increase in the collagen content was observed in the viable left ventricle and septum of the rat with CHF. These increases were attenuated by the long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809.

Figure 6.

Effects of trandolapril (Tra) and L-158809 (L) on myocardial collagen content of the scar tissue (A), left ventricle (B), septum (C), and right ventricle (D) of sham-operated rats (open columns) and rats with CHF (closed columns). ‘Un' indicates animals without drug-treatment. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of five experiments. *Significantly different from the corresponding sham-operated group (P<0.05). #Significantly different from the CHF group (P<0.05).

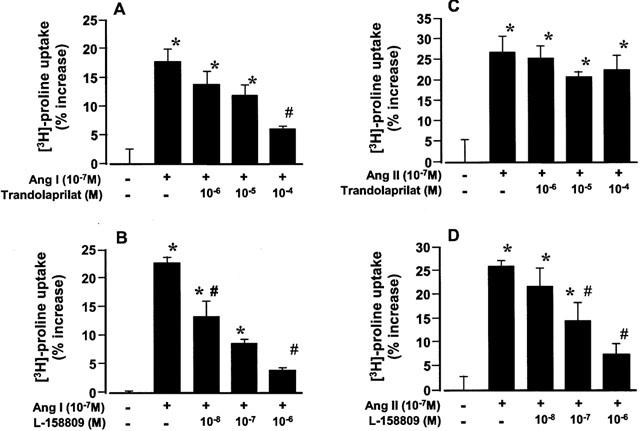

Effects of ACE inhibition or AT1 receptor blockade on angiotensin I- and angiotensin II-induced collagen synthesis

To determine whether the blockade of the RAS may attenuate collagen synthesis at the cellular level, we examine the effects of trandolaprilat, an active form of trandolapril, or L-158809 on collagen synthesis of cardiac fibroblasts in the presence of angiotensin I or angiotensin II. Angiotensin I (10−7 M) and angiotensin II (10−7 M) stimulated collagen synthesis in cardiac fibroblasts (Figure 7). Trandolaprilat (10−6 – 10−4 M) and L-158809 (10−8 – 10−6 M) attenuated angiotensin I (10−7)-induced collagen synthesis in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 7A,B). L-158809 (10−8 – 10−6 M) also attenuated angiotensin II (10−7)-induced collagen synthesis in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 7D), whereas trandolaprilat did not affect the angiotensin II-induced collagen synthesis (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Effects of trandolaprilat and L-158809 on exogenous angiotensin I-induced (A and B) and angiotensin II-induced (C and D) changes in collagen synthesis in culture cardiac fibroblasts. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of four experiments. *Significantly different from control group (P<0.05). #Significantly different from the angiotensin I alone group (P<0.05).

Discussion

Several clinical trials showed that ACE inhibitors favourably affected haemodynamics, improved symptoms (Pfeffer et al., 1992), and reduced overall mortality in patients with congestive heart failure (The CONSENSUS trial study group, 1987; The SOLVD investigators, 1991) and that AT1-receptor blockers improved left ventricular dysfunction in patients with heart failure as well (McKelvie et al., 1997; Pitt et al., 1997). In this study, we examined the effects of an ACE inhibitor and an AT1 receptor blocker on the haemodynamic, cardiac remodelling, and changes in G protein levels in the experimental animals with CHF. Although angiotensin II in humans is produced not only through the action of ACE but also through chymase (Urata et al., 1990; Wolny et al., 1997; Borland et al., 1998), the rat does not have chymase-mediated angiotensin II formation (Yamamoto et al., 1998; Miyazaki & Takai, 2000). This property may be beneficial for the comparison of the effects of these drugs in rats.

Long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 decreased the body weight of the sham-operated rat, an effect that may be due to inhibition of the dipsinogenic effects (Kraly & Corneilson, 1990) of angiotensin II, and decreased the total body sodium and water. The RV weight of the rats with CHF was decreased by trandolapril or L-158809 treatment, which is related most likely to the decreased preload and inhibition of the direct effects of angiotensin II on cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Both lung weight and lung weight-to-body weight of the rats with CHF were attenuated by treatment with trandolapril or L-158809. This indicates that inhibition of the RAS improves pulmonary oedema of the animals with CHF. Our results suggest that either ACE inhibitor or AT1 receptor blocker may inhibit ventricular hypertrophy and decrease preload. These results are consistent with previous observations of ours (Sanbe & Takeo, 1995) and of Böhm et al. (1998).

In the rats with CHF, the pressure-volume curve was shifted to the right, indicating an increase in the left ventricular diastolic volume and a decrease in the left ventricular chamber stiffness. There was a significant leftward shift of the pressure-volume relation in the trandolapril- or L-158809-treated CHF animals, compared with that of each untreated animal. Furthermore, the reduction in ventricular chamber stiffness in rats with CHF tended to be restored to the sham level by treatment with trandolapril or L-158809. These results suggest that long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 attenuated the left ventricular diastolic dysfunction of cardiac muscles that occurred at this period. The reduction in the left ventricular dilation of the infarct heart by the ACE inhibitor and the AT1 receptor blocker is probably due to decreases in both preload and afterload, and thereby improves the ejection of stroke volume.

We studied changes in the levels of isoforms of Gsα, Giα and Gqα protein in the membranes from the whole ventricular tissues of sham-operated and CHF rat hearts. Although an increase in Gsα protein was detected in the scar zone, CAL induced a decrease in cardiac Gsα protein. The cardiac Gsα protein level was not affected by treatment with ACE inhibitor or AT1 receptor blocker. It is generally considered that the RAS system is not coupled with Gsα protein. Thus, the lack of a connection between the RAS blockade and cardiac Gsα protein would be reasonable. In contrast, the levels of Gi1,2α and Gi3α of the animals with CHF increased at any part of the heart of the rat with CHF. The increase was partially or completely reversed by treatment with trandolapril or L-158809. This finding indicates that the RAS system may be closely related to the CAL-induced increase in Giα protein. A marked increase in Gqα was detected in the scar zone, whereas the level of Gqα protein was slightly increased in the viable left ventricle, and rather decreased in the septum and right ventricle of the animals with CHF. Long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 did not affect the changes in the Gqα protein level. It is generally believed that the AT1 receptor is coupled with Gqα protein and that this coupling plays an important role in cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis (Lamorte et al., 1994; Weber et al., 1994). The present study showed that the blockade of RAS system did not affect the levels of Gqα protein, indicating that CAL-induced change in Gqα protein occurs by some mechanism other than activation of the RAS system.

The present study showed a marked increase in the levels of Giα proteins and cardiac collagen content in CHF rats, and an almost complete reversal of these increases by treatment with trandolapril or L-158809. We observed no change in Giα proteins of cardiomyocyte isolated from the CHF rats in a previous study (Yoshida et al., 2001). Thus, the marked increase in the levels of Gi1,2α and Gi3α proteins appeared to depend on nonmyocytes. This implies that the increase in Giα protein may be related to an increase in the abnormal proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts. Trandolapril or L-158809 suppressed this increase. The abnormal proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts with excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix protein is one of the features of the left ventricular remodelling, which may lead ultimately to cardiac dysfunction (Weber, 1997). Zou et al. (1998) postulated that angiotensin II directly stimulated proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts via AT1 receptor activation. We also showed here that angiotensin I and angiotensin II directly stimulated collagen synthesis in cultured cardiac fibroblasts and that the stimulation was attenuated by blockade of the RAS. Furthermore, several investigators reported that nonmyocytes regulated the development of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through endothelin-1 and cardiotrophin-1 secretion (Harada et al., 1997; Kuwahara et al., 1999). In accord with this, the collagen content of the viable left ventricle of the CHF rats increased, which was attenuated by treatment with trandolapril or L-158809. Thus, not only AT1 receptor blockade but also ACE inhibition may attenuate the angiotensin II-induced fibrosis in hearts, probably resulting in an improvement of cardiac dysfunction and the following development of cardiac hypertrophy. Despite such suggestion, we cannot rule out the possibility that less collagen formation in the scar tissue might be associated with weaker contractile function of the heart.

In conclusion, long-term treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 improved the symptoms of chronic heart failure, such as cardiac hypertrophy, increased LVEDP and LV volume, and pulmonary oedema, probably as a result of decreased preload and afterload. Furthermore, treatment with trandolapril or L-158809 attenuated the CAL-induced increase in the level of Giα proteins, probably by the inhibition of abnormal proliferation of fibroblasts. Thus, we suggest that blockade of the RAS may attenuate the angiotensin II-induced induction of cardiac fibrosis and thus improve the cardiac dysfunction of CHF. There were no appreciable differences in the extent of the effects of the ACE inhibitor and AT1 receptor blocker on functional and biochemical variables examined at the therapeutic doses.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr L.D. Frye, Ph.D. for editing the text.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- AT1

angiotensin II type 1

- CAL

coronary artery ligation

- CHF

chronic heart failure

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- FBS

foetal bovine serum

- HR

heart rate

- LV

left ventricle

- LVEDVI

left ventricular end-diastolic volume index

- LVEDP

left ventricular end-diastolic pressure

- LVSP

left ventricular systolic pressure

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PLC-β

phospholipase C-β

- RAS

renin-angiotensin system

- RV

right ventricle

- SDS

sodium dodecylsulphate

References

- ANAND-SRIVASTAVA M.B. Enhanced expression of inhibitory guanine nucleotide regulatory protein in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biochem. J. 1992;288:79–85. doi: 10.1042/bj2880079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BÖHM M., ZOLK O., FLESCH M., SCHIFFER F., SCHNABEL P., STASCH J-P., KNORR A. Effects of angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on cardiac β-adrenergic signal transduction. Hypertension. 1998;31:747–754. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.3.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORLAND J.A., CHESTER A.H., MORRISON K.A., YACOUB M.H. Alternative pathways of angiotensin II production in the human saphenous vein. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:423–428. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADFORD M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLETCHER P.J., PFEFFER J.M., PFEFFER M.A., BRAUNWALD E. Left ventricular diastolic pressure-volume relations in rats with healed myocardial infarction: effects on systolic function. Circ. Res. 1981;49:618–626. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.3.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANCIS G.S., COHN J.N., JOHNSON G., RECTOR T.S., GOLDMAN S., SIMON A. Plasma norepinephrine, plasma renin activity, and congestive heart failure. Relations to survival and the effects of therapy in V-HeFT II. Circulation. 1993;87 Suppl VI:40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARADA M., ITOH H., NAKAGAWA O., OGAWA Y., MIYAMOTO Y., KUWAHARA K., OGAWA E., IGAKI T., YAMASHITA J., MASUDA I., YOSHIMASA T., TANAKA I., SAITO Y., NAKAO K. Significance of ventricular myocytes and nonmyocytes interaction during cardiocyte hypertrophy: evidence for endothelin-1 as a paracrine hypertrophic factor from cardiac nonmyocytes. Circulation. 1997;96:3737–3744. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAKOB H., SIGMUND M., ESCHENHAGEN T., MENDE U., PATTEN M., SCHMITZ W., SCHOLZ H., SCHULTE A.M., ESCH J., STEINFATH M., HANRATH P., VOLKER H. Effects of captopril on myocardial β-adrenoceptor density and Giα-proteins in patients with mild to moderate heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1995;47:389–394. doi: 10.1007/BF00196850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JU H., ZHAO S., TAPPIA P.S., PANAGIA V., DIXON I.M.C. Expression of Gqα and PLC-β in scar and border tissue in heart failure due to myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;97:892–899. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.9.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRALY F.S., CORNEILSON R. Angiotensin II mediates drinking elicited by eating in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;258:R436–R442. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.2.R436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUWAHARA K., SAITO Y., HARADA M., ISHIKAWA M., OGAWA E., MIYAMOTO Y., HAMANAKA I., KAMITANI S., KAJIYAMA N., TAKAHASHI N., NAKAGAWA O., MASUDA I., NAKAO K. Involvement of cardiotrophin-1 in cardiac myocyte-nonmyocyte interactions during hypertrophy of rat cardiac myocytes in vitro. Circulation. 1999;100:1116–1124. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMORTE V.J., THORBURN J., ABSHER D., SPIEGEL A., BROWN J.H., CHIEN K.R., FERAMISCO J.R., KNOWLTON K.U. Gq- and ras-dependent pathways mediate hypertrophy of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes following α1-adrenergic stimulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:13490–13496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDPAINTNER K., GANTEN D. The cardiac renin-angiotensin system. An appraisal of present experimental and clinical evidence. Circ. Res. 1991;68:905–921. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.4.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU Y.H., YANG X.P., SHAROV V.G., NASS O., SABBAH H.N., PETERSON E., CARRETERO O.A. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II type I receptor antagonists in rats with heart failure. Role of kinins and angiotensin II type 2 receptors. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:1926–1935. doi: 10.1172/JCI119360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOPEZ-DE LEON A., ROJKIND M. A simple micromethod for collagen and total protein determination in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1985;33:737–743. doi: 10.1177/33.8.2410480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAKI T., HORIO T., YOSHIHARA F., SUGA S., TAKEO S., MATSUO H., KANGAWA K. Effect of neutral endopeptidase inhibitor on endogenous atrial natriuretic peptide as a paracrine factor in cultured cardiac fibroblasts. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:1204–1210. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCKELVIE R.S., YUSUF S., PERICAK D., AVEZUM A., BURNS R.J., PROBSTFIELD J., TSUYUKI R.T., WHITE M., ROULEAU J., LATINI R., MAGGIONI A., YOUNG J., POGUE J. Comparison of candesartan, enalapril, and their combination in congestive heart failure: randomized evaluation of strategies for left ventricular dysfunction (RESOLVED) pilot study. The RESOLVD Pilot Study Investigators. Circulation. 1997;100:1056–1064. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCMAHON K.K. Developmental changes of the G proteins-muscarinic cholinergic receptor interactions in rat heart. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;251:372–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIDDLEKAUFF H.R. Mechanisms and implications of autonomic nervous system dysfunction in heart failure. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 1997;12:265–275. doi: 10.1097/00001573-199705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYAZAKI M., TAKAI S. Role of chymase on vascular proliferation. J reninangiotensin-aldosterone system. 2000;1:23–26. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2000.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETERSON D.J., JU H., HAO J., PANAGIA M., CHAPMAN D.C., DIXON I.M.C. Expression of Gi-2α and Gsα in myofibroblasts localized to the infarct scar in heart failure due to myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;41:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFEFFER M.A., BRAUNWALD E., MOYE L.A., BASTA L., BROWN E.J., JR, CUDDY T.E., DAVIS B.R., GELTMAN E.M., GOLDMAN S., FLAKER G.C., KLEIN M., LAMAS G.A., PACKER M., ROULEAU J., ROULEAU J.L., RUTHERFORD J., WERTHEIMER J.H., HAWKINS C.M. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. The SAVE Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992;327:669–677. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PITT B., SEGAL R., MARTINEZ F.A., MEURERS G., COWLEY A., THOMAS I., DEEDWANIA P.C., NEY D.B., CHANG P.I. Randomised trial of losartan versus captopril in patients over 65 with heart failure (Evaluation of Losartan in the Elderly Study, ELITE) Lancet. 1997;349:747–752. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)01187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SADOSHIMA J., QIU Z., MORGAN J.P., IZUMO S. Angiotensin II and other hypertrophic stimuli mediated by G protein-coupled receptors activate tyrosine kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and 90-kD S6 kinase in cardiac myocyte: the critical role of Ca2+-dependent signaling. Circ. Res. 1995;76:1–15. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANBE A., TAKEO S. Long-term treatment with angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitors attenuates the loss of cardiac beta-adrenoceptor responses in rats with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1995;92:2666–2675. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.9.2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANBE A., TANONAKA K., HANAOKA Y., KATOH T., TAKEO S. Regional energy metabolism of failing hearts following myocardial infarction. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1993;25:995–1013. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHI B., HEAVNER J.E., MCMAHON K.K., SPALLHOLZ J.E. Dynamic changes in Gαi-2 levels in rat hearts associated with impaired heart function after myocardial infarction. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:H1073–H1079. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.3.H1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STOCK P., LIEFELDT L., PAUL M., GANTEN D. Local renin-angiotensin systems in cardiovascular tissues: localization and functional role. Cardiology. 1995;86:2–8. doi: 10.1159/000176938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The CONSENSUS Trial Study Group Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS) N. Engl. J. Med. 1987;316:1429–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706043162301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The SOLVD Investigators Effects of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and congestive heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;325:293–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAUTWEIN W., HESCHELER J. Regulation of cardiac L-type calcium current by phosphorylation and G proteins. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1990;52:257–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.52.030190.001353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- URATA H., HEALY B., STEWART R.W., BUMPUS F.M., HUSAIN A. Angiotensin II-forming pathways in normal and failing human hearts. Circ. Res. 1990;66:883–890. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.4.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VILLARREAL F.J., KIM N.N., UNGAB G.D., PRINTZ M.P., DILLMANN W.H. Identification of functional angiotensin II receptors on rat cardiac fibroblasts. Circulation. 1993;88:2849–2861. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBER K.T. Extracellular matrix remodeling in heart failure: A role of de novo Angiotensin II generation. Circulation. 1997;96:4065–4082. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.11.4065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBER K.T., SUN Y., TYAGI S.C., CLEUTJENS J.P. Collagen network of the myocardium: function, structural remodeling and regulatory mechanisms. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1994;26:279–292. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1994.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOLNY A., CLOZEL J.P., REIN J., MORY P., VOGT P., TURINO M., KIOWSKI W., FISCHLI W. Functional and biochemical analysis of angiotensin II-forming pathways in the human heart. Circulation. 1997;80:219–227. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO D., SHIROTA N., TAKAI S., ISHIDA T., OKUNISHI H., MIYAZAKI M. Three-dimensional molecular modeling explains why catalytic function for angiotensin-I is different between human and rat chymases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;242:158–163. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOSHIDA H., TANONAKA K., MIYAMOTO Y., ABE T., TAKAHASHI M., ANAND-SRIVASTAVA M.B., TAKEO S. Characterization of cardiac myocyte and tissue β-adrenergic signal transduction in rats with heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2001;50:34–45. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZOU Y., KOMURO I., YAMAZAKI T., KUDOH S., AIKAWA R., ZHU W., SHIOJIMA I., HIROI Y., TOBE K., KADOWAKI T., YAZAKI Y. Cell type-specific angiotensin II-evoked signal transduction pathways: critical roles of Gβγ subunit, Src family, and Ras in cardiac fibroblasts. Circ. Res. 1998;82:337–345. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]