Abstract

Our study shows that the prostacyclin analogues AFP-07 and cicaprost are moderately potent agonists for prostanoid EP4 receptors, in addition to being highly potent IP1 receptor agonists. Both activities were demonstrated on piglet and rabbit saphenous veins, which are established EP4 preparations.

On piglet saphenous vein, PGE2 was 6.1, 24, 96, 138, 168 and 285 times respectively more potent than AFP-07, cicaprost, PGI2, iloprost, carbacyclin and TEI-9063 in causing relaxation. Another prostacyclin analogue taprostene did not induce maximum relaxation (21 – 74%), and did not oppose the action of PGE2. The EP4 receptor antagonist AH 23848 (30 μM) blocked relaxant responses to PGE2 (dose ratio=8.6±1.3, s.e.mean) to a greater extent than cicaprost (4.9±0.7) and AFP-07 (3.8±0.8), had variable effects on TEI-9063-induced relaxation (3.7±1.5), and had no effect on taprostene responses (<2.0).

On rabbit saphenous vein, AH 23848 blocked the relaxant actions of PGE2, AFP-07, cicaprost, iloprost and carbacyclin to similar extents.

AFP-07, cicaprost and TEI-9063 showed high IP1 relaxant potency on piglet carotid artery, rabbit mesenteric artery and guinea-pig aorta, with AFP-07 confirmed as the most potent IP1 agonist reported to date. AH 23848 did not block cicaprost-induced relaxation of piglet carotid artery. EP3 contractile systems in these preparations can confound IP1 agonist potency estimations.

Caution is urged when using AFP-07 and cicaprost to characterize IP1 receptors in the presence of EP4 receptors. Taprostene may be a lead to a highly selective IP1 receptor agonist.

Keywords: Vascular smooth muscle, prostanoid EP receptors, prostanoid IP receptors, prostaglandin E2, prostacyclin, cicaprost, iloprost, sulprostone, AH 23848

Introduction

The classical effects of prostacyclin (or PGI2) are inhibition of platelet aggregation and relaxation of vascular smooth muscle, with cyclic AMP being the likely second messenger. The receptor involved has been termed a prostanoid IP1 receptor to distinguish it from a recently described IP2 receptor, which is present in specific brain regions and mediates cyclic AMP-independent excitation of brain neurones (Wise & Jones, 2000).

Identification of IP1 receptors in functional systems has relied heavily on the use of stable analogues of prostacyclin, particularly of the 6a-carba (or carbacyclin) series (see Figure 1 and Wise & Jones, 2000). Cicaprost has proved to be the most useful of these IP1 agonists owing to its high selectivity; other agonists such as iloprost, carbacyclin and isocarbacyclin also activate EP1 and EP3 receptors, leading to mixed effects particularly on isolated smooth muscle preparations (Dong et al., 1986; Lawrence et al., 1992). Radioligand binding studies on mouse cloned systems have also shown that cicaprost has a much higher affinity for the IP1 receptor compared to the four known EP receptor subtypes (Kiriyama et al., 1997). Relevant to this study, cicaprost had a Ki in excess of 10 μM for the EP4 receptor compared to 1.9 nM for PGE2 and 2.3 μM for iloprost.

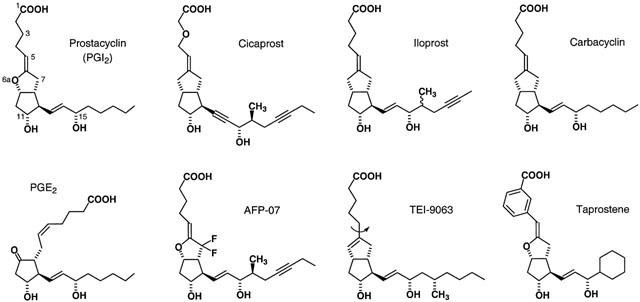

Figure 1.

Structures of PGE2, prostacyclin and the chemically stable prostacyclin analogues used in this study. In 6a-carba analogues, a CH2 group replaces the 6a-oxygen – see carbacyclin itself. Iloprost is a mixture of C16 epimers. The curved arrow on the structure of TEI-9063 indicates free rotation around the C5 – C6 bond, which is not allowed in the 5,6-ene analogues.

AFP-07 has a prostacyclin-like ring structure stabilized by two fluorine atoms at C7 (Figure 1); it is the most potent IP1 agonist reported to date (Chang et al., 1997). High IP1 selectivity was also accorded to AFP-07 from ligand binding measurements on mouse IP1 and EP receptor subtypes. However, from the competition plots presented in the Chang paper we have calculated that AFP-07 has a Ki of about 15 nM for the EP4 receptor, which is much smaller than the value of 1.2 μM found for iloprost. We decided to investigate how this moderately high affinity of AFP-07 for the EP4 receptor translates into agonist activity in a functional system.

A simple solution would be to use the relaxation response of the piglet isolated saphenous vein, an EP4 preparation for which ‘PGE2 is the most potent agonist (IC50=0.23 nM), whereas all the other [natural] agonists are at least 1000 fold weaker' (Coleman et al., 1994). However, in preliminary experiments with this preparation we found that AFP-07, cicaprost and prostacyclin were only about 6, 20 and 100 times less potent than PGE2 respectively. It seemed possible that the piglet saphenous vein also contains an IP1 relaxation system. Consequently, we felt that a more in depth investigation was required.

Our plan had three main components:

(a) The relaxant activities of several prostacyclin analogues were compared on putative EP4 and IP1 receptor preparations from the same species. The EP4 preparations were piglet saphenous vein (Coleman et al., 1994) and rabbit saphenous vein (Lydford et al., 1996); the corresponding IP1 preparations were piglet carotid artery (this investigation) and rabbit mesenteric artery (Bunting et al., 1976). We also used the guinea-pig thoracic aorta as an IP1 preparation, based on its high sensitivity to cicaprost (Jones et al., 1998). Two of the prostacyclin analogues proved to be of particular significance: the isocarbacyclin TEI-9063 is a highly potent IP1 agonist (Negishi et al., 1991; Jones et al., 1997) with a more flexible α-chain than carbacyclins such as iloprost and cicaprost, while taprostene is a prostacyclin with less α-chain flexibility due to the presence of a 1,5-m-interphenylene unit (Michel & Seipp, 1990; Schneider et al., 1993) (Figure 1).

(b) AH 23848, an EP4 receptor antagonist, was used in an attempt to distinguish EP4 and IP1 relaxant activity. The affinity of this compound is quite low however: pA2 versus PGE2=5.4 and 5.0 on piglet and rabbit saphenous veins respectively (Coleman et al., 1994; Lydford et al., 1996). It also blocks prostanoid TP receptors (pA2 versus U-46619=7.8 – 8.3; Brittain et al., 1985), but this was of no consequence since the bathing fluid routinely contained the related and highly selective TP receptor antagonist GR 32191 (Lumley et al., 1989).

(c) Interference from EP3 contractile systems (Qian et al., 1994; Jones et al., 1998) potentially present in the vascular preparations was investigated. EP3-receptors may be identified with sulprostone, which has an agonist selectivity profile: EP3>EP1>>EP2=EP4 (Coleman et al., 1987; 1994), and SC-46275, a highly potent EP3 agonist with minimal activity on EP1 and EP2 receptors (Savage et al., 1993) and unknown activity on EP4 receptors.

During our studies, Abramovitz et al. (2000) reported cicaprost to be a moderately potent ligand for the human cloned EP4 receptor (Ki=44 nM), thereby revealing a large species difference between man and mouse. This information did not significantly alter the strategy of our study, but it clearly has a bearing on the interpretation of the results.

Methods

Isolated tissue preparations

All experimental procedures were performed under licence issued by the Government of the Hong Kong SAR and endorsed by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Landrace piglets, weighing 2.0 – 2.5 kg (1 week-old), were killed by exposure to 100% CO2. Male New Zealand White rabbits, weighing 2.5 – 3.5 kg, and male Dunkin-Hartley guinea-pigs, weighing 400 – 450 g, were killed by cervical dislocation and exsanguination.

The following vessels were excised and adherent fat and connective tissue were removed: saphenous vein and (superior) mesenteric artery from rabbit; (descending thoracic) aorta from guinea-pig; (common) carotid artery and (left) azygos, (external) jugular, (cranial) mesenteric, (left) renal and (lateral) saphenous veins from piglet. Four to six rings (3 mm wide) were cut and suspended by stainless steel hooks under 0.8 – 1.0 g tension in 10 ml organ baths containing Krebs-Henseleit solution (mM: NaCl 118, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 2.5, MgSO4 1.2, KH2PO4 1.18, NaHCO3 25, glucose 10 mM) at 37°C and aerated with 95% O2/5% CO2. Isometric tension changes were recorded with Grass FT03 force transducers linked to a MacLab 4/Macintosh PowerMac computer system (sampling rate 40 per min). The bathing solution contained 1 μM indomethacin in all experiments. In some experiments endothelium was removed by gentle rubbing with a wooden toothpick.

Experimental protocols

Reproducible contractile responses to 40 mM KCl were first obtained on each preparation. All subsequent tests were performed in the presence of the TP antagonist GR 32191 (see Results for concentrations) added 5 min before the addition of phenylephrine. Phenylephrine was used to induce 50 – 60% maximal contraction at the following concentrations: piglet saphenous vein (0.15 – 0.30 μM), piglet carotid artery (2 – 3 μM), rabbit saphenous vein (1 – 2 μM), rabbit mesenteric artery (1.5 – 3 μM), guinea-pig aorta (1 – 2 μM). A cumulative (1, 3, 10, 30…) sequence of prostanoid doses was added 10 min later. On guinea-pig aorta the first prostanoid sequence was cicaprost and on the other preparations PGE2. Second, third and (sometimes) fourth prostanoid sequences were used for comparison of agonist potencies. The time between washout of agonist and start of the next agonist sequence was 45 – 60 min. A balanced design was used to distribute individual prostanoid agonists between animals, between preparations from the same animal, and between dose sequences on the same preparation. For antagonism studies with either AH 23848 or taprostene (potential partial agonist), two matched preparations were always used: the second sequence was agonist alone and the third sequence was either (antagonist/partial agonist)+agonist or vehicle+agonist. Preparations were exposed to AH 23848 for 30 min before addition of the first agonist dose.

Data analysis

Responses were expressed as percentages of the tone induced by phenylephrine. Values are presented as means±s.e.mean. The GraphPad Prism program (GraphPad Software Inc.) was used to construct and analyse log concentration-response curves. Sigmoidal curves were fitted with the equation:

where A is the molar concentration of agonist, EC50 (or IC50) is the molar concentration of agonist eliciting a 50% maximal response, and n is the slope factor (Hill factor). The lower asymptote was constrained to the tone level induced by phenylephrine (100%) or to the relaxation response elicited by the potential partial agonist. The trend of a bell-shaped relationship was fitted with the LOWESS (locally weighted regression scatter plot smoothing) facility in GraphPad Prism (based on an algorithm in Chambers et al., 1983). Equi-effective molar ratios (EMR) were obtained by dividing IC50 for test agonist by IC50 for standard agonist (the latter has an EMR of 1.0). pA2 values were calculated from the Schild equation: log(dose ratio −1)=log[antagonist]+pA2. Correlation/linear regression analysis was performed with StatView software (SAS Institute Inc.). ANOVA accompanied by comparison of means by planned orthogonal contrasts (Glass & Hopkins, 1995) was performed with SuperANOVA software (Abacus Concepts Inc.). Responses and slope factors obtained from successive dose sequences on matched preparations were analysed with a repeated-measures 2-factor ANOVA model. All tests were two-tailed, with P value of 0.05 taken as the threshold of statistical significance.

Drugs and solutions

The following compounds were gifts: AFP-07 (7,7-difluoro-16S,20-dimethyl-18,19-didehydro PGI2) from Asahi Glass Co., Japan; TEI-9063 (17S,20-dimethyl-Δ6,6a-6a-carba PGI1) from Teijin Co., Japan; taprostene from Grunenthal GmbH, Germany; iloprost, cicaprost and sulprostone from Schering AG, Germany; SC-46275 (methyl 7-[2β-[6-(1-cyclopenten-1-yl)-4R-hydroxy-4-methyl-1E, 5E-hexadienyl]-3α-hydroxy-5-oxo-1R,1α-cyclopentyl]-4Z-hept-enoate) from GD Searle, U.S.A.; AH 23848 (rac-[1α(Z),2β,5α]-7-[5-([1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl methoxy)-2-(4-morpholynyl)-3-oxocyclopentyl]-4-heptenoic acid) and GR-32191 (9α-(biphenylyl)-methoxy-11β-hydroxy-12β-(N-piperidinyl)-ω-octanor-prost-4Z-enoic acid) from Glaxo Group Research, U.K. PGE2, 17-phenyl-ω-trinor PGE2 (17-phenyl PGE2 in the text), 11-deoxy PGE1, prostacyclin sodium, carbacyclin, butaprost, and U-46619 (11,9-epoxymethano PGH2) were purchased from Cayman Chemical Co., U.S.A. Primary stocks were prepared in absolute ethanol at 5 – 10 mM; all secondary stocks were prepared in 0.9% NaCl solution. Prostacyclin sodium was dissolved in 0.05 M Tris-HCl (pH 9.0) at 100 μM and stored in aliquots at −20°C for subsequent use. A 2 mM solution of AH 23848 was prepared by dissolving the calcium salt, Ca(acid)2, in 10% NaHCO3 solution and then diluting 10 fold with saline; a fresh solution was made for each day's experiments. Indomethacin and phenylephrine HCl were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., U.S.A.

Results

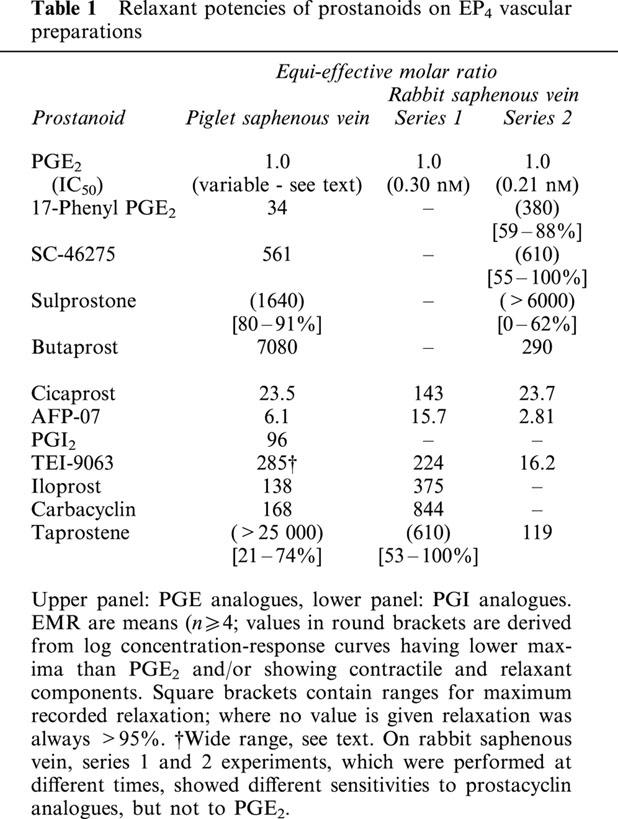

Contraction and relaxation of a vessel ring preparation refer to changes in tension superimposed on tone induced by the selective α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine. Cumulative dosing of prostanoids was routinely used, and in the figures log concentration-response curves for PGE and PGI analogues are represented by filled and unfilled symbols respectively. Table 1 shows relaxant potencies expressed as equi-effective molar ratios (EMR) with respect to PGE2 (=1.0) on the piglet and rabbit saphenous veins, which are putative EP4 preparations. Table 2 shows EMR relative to cicaprost (=1.0) for prostacyclin analogues only on the two EP4 and the three IP1 preparations investigated. The endothelium on each type of preparation was nominally left intact. However, on a few endothelium-denuded preparations we showed that the actions of PGE2, cicaprost and sulprostone were similar to those in the endothelium-intact state.

Table 1.

Relaxant potencies of prostanoids on EP4 vascular preparations

Table 2.

Relaxant potencies of prostacyclin analogues relative to cicaprost on EP4 and IP1 preparations

The TP receptor antagonist GR 32191 was present in all experiments: a concentration of 1.0 μM was used for piglet saphenous vein (U-46619 as agonist, pA2=7.8, Coleman et al., 1994) and other piglet vessels, and 0.2 μM for guinea-pig aorta (pA2=9.15, Jones et al., 1998). Although Lydford et al. (1996) reported a pA2 of 8.0 for GR 32191 on rabbit saphenous vein, we have previously found rabbit TP receptors to be somewhat resistant to GR 32191 block (Tymkewycz et al., 1991). Hence, a higher concentration of GR 32191 (3 μM) was used for rabbit saphenous vein and mesenteric artery.

Putative EP4 preparations

Piglet saphenous vein

All preparations were completely relaxed by PGE2, but IC50 values for PGE2 (first sequence) varied by some 56 fold (0.063 – 3.5 nM, n=107). Typical responses to PGE2 on high sensitivity preparations are shown in Figure 2a. The variation in PGE2 sensitivity was distributed roughly equally between animals and preparations, with IC50s for the four or six preparations obtained from one piglet varying by 1.6 – 16 fold. The location of the vessel ring did not contribute significantly to the variation: mean IC50s for rings 1 – 6 (proximal to distal) ranged between 0.22 and 0.34 nM (P>0.05 for any pair-wise comparison of mean logIC50 values; 1-factor ANOVA). Responsiveness to phenylephrine was also highly consistent. We observed that spontaneous contractions (20 – 50% of maximum, duration 5 – 10 min) were more prevalent in the low sensitivity preparations during the settling-in period and following washout of relaxant agents. However, spontaneous activity was minimal in the presence of tone induced by phenylephrine, thereby allowing accurate measurement of relaxation responses. A few preparations with the highest IC50 values for PGE2 (1.5 – 3.5 nM) generated stable spontaneous tone of about 10% of the maximum tissue response.

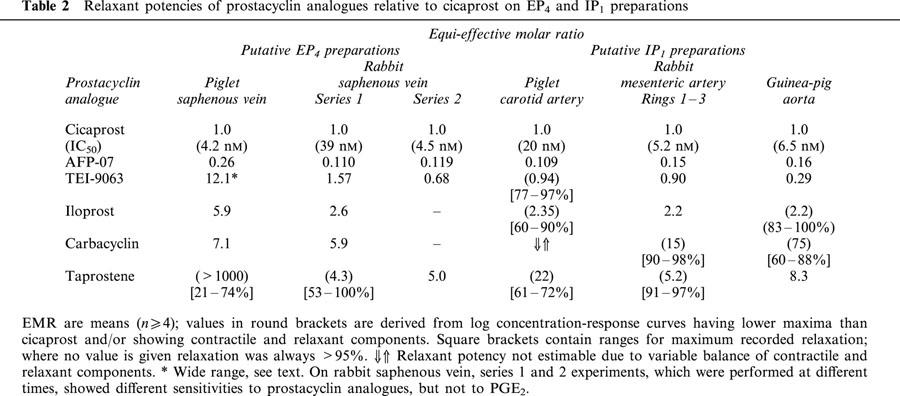

Figure 2.

Relaxation of piglet saphenous vein preparation pre-contracted with phenylephrine. (a) Experimental records for single preparations from two different animals (lower and upper panels) that showed high sensitivity to PGE2; cumulative prostanoid concentrations (nM) are shown; W=wash. (b) and (c) Log concentration-response curves for PGE2 and prostacyclin analogues grouped on the basis of sensitivity; for each curve, the logIC50 values fall within a 0.5 log unit range. (d) Log concentration-response curves for PGE analogues. (e) Log concentration-response curves for PGE2, cicaprost and taprostene acting alone and PGE2 and cicaprost in the presence of 3.33 μM taprostene. (f) Effect of AH 23848 on relaxant responses to taprostene alone and to PGE2 in the presence of 3.33 μM taprostene. GR 32191 (0.2 μM) was present in all tests. Values are mean±s.e.mean (n=4 – 14).

Sensitivity to PGE2 increased consistently with time, irrespective of the initial sensitivity. Thus the mean IC50s for PGE2 for dose sequences 2, 3, and 4 were 0.83, 0.75 and 0.70 fold of the sequence one value; this trend was not due to declining responses to phenylephrine.

None of the prostacyclin analogues showed contractile activity and all consistently induced complete relaxation with the exception of taprostene (Figure 2a,b,c). For AFP-07 and cicaprost we had enough data to see a trend of increasing sensitivity with time similar to PGE2; sensitivity to TEI-9063 stayed constant over time. LogIC50 values for AFP-07, cicaprost and TEI-9063 were highly correlated with the time-corrected logIC50s for PGE2 in the same preparations (r2=0.87, 0.85 and 0.85, n=18, 22 and 20, respectively). The linear regression coefficients of 0.93 and 0.89 for AFP-07 and cicaprost were not significantly different to unity (95% CI=0.74 – 1.12 and 0.72 – 1.06), indicating that the potencies of AFP-07 and cicaprost relative to PGE2 remain roughly constant. In contrast, the regression coefficient of 1.54 for TEI-9063 was significantly greater than unity (99% CI=1.11 – 1.97), showing that TEI-9063 becomes less potent relative to PGE2 as sensitivity to PGE2 decreases. Figure 2b,c illustrates this finding: log concentration-response curves for PGE2, AFP-07, cicaprost and TEI-9063 were grouped according to PGE2 sensitivity (logEC50s for each group fall within 0.5 log unit).

One-Factor ANOVA applied to all data showed that the slope factor of PGE2 log concentration-response curves (1.76±0.09, s.e.mean, n=22, second or third sequences) was less than that of AFP-07 (2.03±0.11, n=18, P<0.05), not different from cicaprost (1.61±0.06, n=21, P>0.05), and greater than TEI-9063 (1.30±0.07; n=20, P<0.001). Correlation analysis of slope factor versus logEC50 value showed that reduction in sensitivity to TEI-9063 was associated with a significant reduction in slope factor (P<0.05), whereas there were no significant correlations for PGE2, AFP-07 and cicaprost.

On 16 saphenous vein preparations, taprostene always produced a clear relaxation at 30 nM, but failed to induce complete relaxation with increasing concentration (Figure 2a,b). Two preparations stood out from the rest in terms of the maximum relaxation induced (high sensitivity taprostene curve in Figure 2b); these preparations were also highly sensitive to PGE2 (IC50=0.11 and 0.12 nM). The taprostene curves for the remaining preparations have been divided into medium and low sensitivity (PGE2 IC50 greater or less than 0.3 nM), corresponding to the TEI-9063 allocations. As sensitivity to PGE2 decreases, there is a trend for a lower maximum response to taprostene together with a small right-shift of IC50.

Finally, in the presence of 3.33 μM taprostene, there were small left-shifts of the log concentration-response curves for both PGE2 (IC50 0.19 to 0.11 nM) and cicaprost (IC50 6.1 to 4.8 nM) (Figure 2e). It seems unlikely therefore that taprostene is an EP4 partial agonist, since we would expect a considerable right-shift of the PGE2 curve (higher IC50 value) during high occupancy of EP4 receptors by taprostene.

In a small number of experiments (n=4/5), prostacyclin, iloprost and carbacyclin elicited full relaxation and gave log concentration-response curves parallel to PGE2 (EMR in Table 1). As expected, the relaxant response to each dose of prostacyclin waned slowly due to spontaneous hydrolysis to 6-oxo PGF1α.

All the PGE analogues induced relaxation only (Figure 2d). In particular, we saw no contractile activity with the lower concentrations of SC-46275 (2.5 – 10 nM) and sulprostone (10 nM). Sulprostone was only tested up to 1.11 μM, at which concentration the mean relaxation was 87%. 17-Phenyl PGE2 (a potent EP1 agonist; Lawrence et al., 1992) was a moderately potent relaxant agent, while butaprost (a selective EP2 agonist; Gardiner, 1986) was the least potent of the PGE analogues tested.

Rabbit saphenous vein

Due to limited supply of rabbits, two series of experiments (S1 and S2) were performed about 6 months apart. In S1 experiments, PGE2, cicaprost, AFP-07, TEI-9063, iloprost and carbacyclin always induced full relaxation (EMRs in Table 1). The slope factor of the PGE2 curve (1.12±0.08) was significantly smaller than those for AFP-07 (1.40±0.06, P<0.01) and TEI-9063 (1.44±0.09, P<0.05), but no different from those of the other agonists (cicaprost 1.11±0.06, iloprost 0.97±0.07, carbacyclin 1.24±0.08). Taprostene produced full relaxation in only two of seven preparations (slope factor=1.12±0.09, Figure 3a).

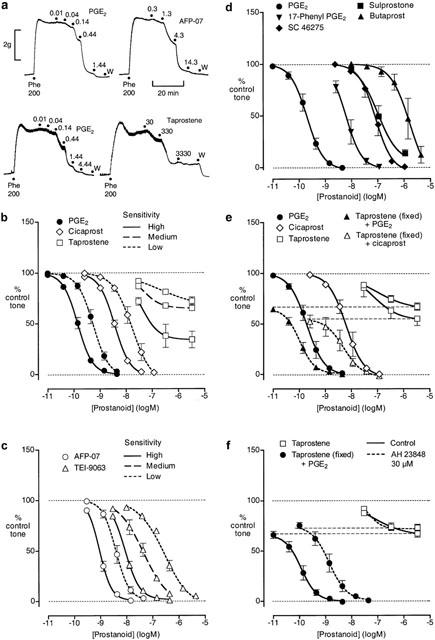

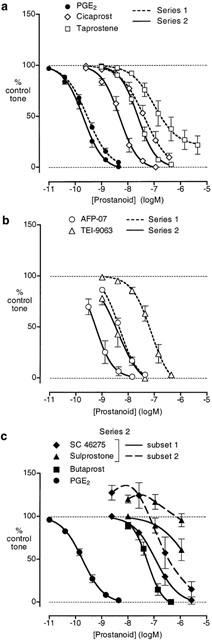

Figure 3.

Relaxation of rabbit saphenous vein preparation pre-contracted with phenylephrine. (a) and (b) Log concentration-response curves for PGE2 and prostacyclin analogues on series 1 and 2 preparations. (c) Log concentration-response curves for PGE analogues on series 2 preparations; subsets 1 and 2 refer to preparations that responded to low concentrations of SC-46275/sulprostone without contraction and with contraction respectively. GR 32191 (3 μM) was present in all tests. Values are mean±s.e.mean (n=6 – 10).

The sensitivity to PGE2 in S2 experiments (IC50=0.30±0.05 nM) was similar to that in S1 experiments (0.21±0.4 nM), whereas AFP-07, cicaprost and TEI-9063 were 5.6, 6.0 and 14 fold more potent as relaxants in S2 compared to S1 (Figure 3a,b; Table 1). Taprostene was also more potent in S2 experiments, inducing at least 95% relaxation (n=6). There were no significant differences in the slopes factors for PGE2, cicaprost, AFP-07, TEI-9063 and taprostene in the S2 experiments (1.27±0.08, 1.44±0.16, 1.58±0.18, 1.62±0.16 and 1.61±0.17 respectively).

The activities of the PGE analogues were also studied in the S2 experiments (Figure 3c). 17-Phenyl PGE2 induced relaxation between 3 and 443 nM, while at a higher concentration (1443 nM) reversal to contraction was seen on all preparations (73±6% to 45±7%, n=4) (data not shown). Responses to SC-46275 and sulprostone were less consistent however. On three preparations (subset 1 in Figure 3c), SC-46275 at the lowest concentration tested (3 nM) had no effect; at higher concentrations complete relaxation could be obtained (slope factor=1.13±0.09). On two other preparations (subset 2), 3 nM SC-46275 induced contraction, which progressed to relaxation as the concentration was increased. Similarly, sulprostone (10 – 1110 nM) also showed two different profiles (3/3 preparations) (Figure 3c), but was a much less potent relaxant agent than SC-46275. Butaprost induced full relaxation with an IC50 of 56 nM.

Putative IP1 preparations

We examined several piglet blood vessels as potential IP1 preparations using PGE2, AFP-07 and cicaprost as test agonists (n=3 in all cases). The jugular, azygos and renal veins were all relaxed by PGE2: IC50=0.7 – 2.0, 3.3 – 8.7 and 4 – 78 nM; maximum relaxations=81 – 92, 95 – 100 and 78 – 85% repectively. Relaxation EMRs for AFP-07 were 13 – 20, 0.87 – 1.9 and 0.82 – 7.8, and for cicaprost 60 – 95, 6.7 – 15 and 15 – 225 on the three types of preparation. All three preparations were rejected on the basis of their pronounced relaxation to PGE2. The mesenteric vein appeared more promising. It was fully relaxed by AFP-07 (IC50=1.5 – 6.3 nM) and cicaprost (10 – 76 nM), while PGE2 at 10 nM gave no response and at 110 nM produced weak relaxation (10 – 42% of maximum). However, we also rejected this preparation because it was difficult to obtain 4 – 6 similar rings from a single piglet owing to the highly branched nature of the hepatic portal circulation. In contrast, up to 6 well-matched preparations could be obtained from the carotid artery and its use as an IP1 preparation is described below.

Piglet carotid artery

Of the prostacyclin analogues tested, cicaprost (Figure 4a) and AFP-07 produced greater than 95% relaxation, with AFP-07 being about nine times more potent than cicaprost (Table 2). TEI-9063 and iloprost also produced greater than 65% relaxation with no reversal to contraction, and we were able to estimate EMRs. However, this was not the case for carbacyclin, where the relaxation response varied from about 5% to about 80% over the 10 – 440 nM concentration range, while at 1440 nM a contractile component was always evident (Figure 4b). Taprostene failed to produce full relaxation (61 – 72%, n=5, Figure 4b), and there was no evidence of reversal of the relaxation response with the higher doses of taprostene. The slope factor for the taprostene curve (1.08±0.12) was significantly smaller (P<0.05, 1-factor ANOVA) than the slope factors for the AFP-07, cicaprost and TEI-9063 curves (1.55±0.11, 1.38±0.05, 1.39±0.01; n=5 – 6).

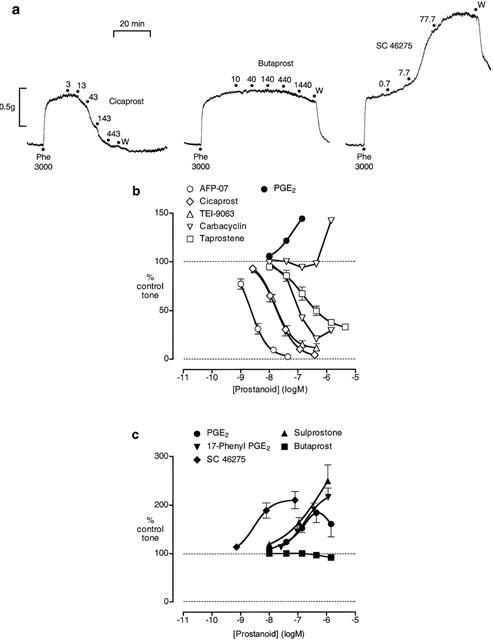

Figure 4.

Actions of prostanoids on piglet carotid artery pre-contracted with phenylephrine. (a) Experimental records (second dose sequences) from three preparations from the same animal; cumulative concentrations (nM) are shown; W=wash. (b) Log concentration-response curves for prostacyclin analogues and PGE2. (c) Log concentration-response curves for PGE analogues. GR 32191 (1 μM) was present in all tests. Values are mean±s.e.mean (n=5 – 12), except for carbacyclin (n=1 in both cases).

PGE2, 17-phenyl PGE2, sulprostone and SC-46275 all induced contraction of the carotid artery (Figure 4c) and the ranking of potency was consistent with the presence of an EP3 receptor. The EP2-selective agonist butaprost produced minimal relaxation up to a concentration of 1.44 μM (Figure 4c); the largest effects are shown in Figure 4a. 11-Deoxy PGE1, which is a potent EP4 agonist (EMR=2.0 on piglet saphenous vein; Milne et al., 1995) had no effect between 1 and 30 nM and contracted the preparation between 30 and 3000 nM (n=3, data not shown). At the highest concentration of PGE2 tested (1.44 μM) slight reversal of contraction was seen on all preparations (Figure 4b). Overall, these findings suggest the absence of both EP2 and EP4 relaxant systems in the piglet carotid artery.

Rabbit mesenteric artery

We attempted to use four artery rings from a single rabbit. PGE2 relaxed rings 1 – 3 (proximal to distal) to a maximum of about 75% (Figure 5b), whereas the maximum relaxation of the most distal ring (ring four) was only about 30% (Figure 5c). Repeated measures 2-factor ANOVA (four levels for ring location, six levels for PGE2 concentration) indicated no significant difference between responses to PGE2 on rings 1, 2 and 3 using either main effects (P∼0.6) or means contrasts at each concentration level (all P>0.16), whereas ring four showed highly significant differences (all P<0.001). We decided to combine results obtained on rings 1, 2 and 3 (Figure 5a,b) and to treat ring four as a separate entity (Figure 5c).

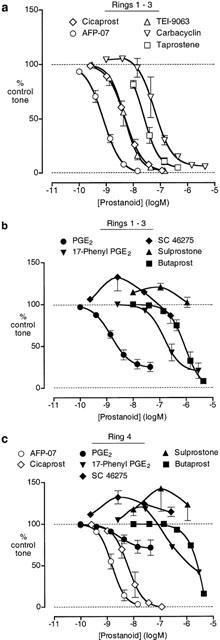

Figure 5.

Actions of prostanoids on rabbit mesenteric artery pre-contracted with phenylephrine. (a) Log concentration-response curves for prostacyclin analogues: combined results for rings 1, 2 and 3. (b) Log concentration-response curves for PGE analogues: combined results for rings 1, 2 and 3. (c) Log concentration-response curves for prostanoids: results for ring four only. GR 32191 (3 μM) was present in all tests. Values are mean±s.e.mean (n=4 – 16), except for 17-phenyl PGE2 and butaprost on ring four (n=1).

Cicaprost, AFP-07, TEI-9063 and iloprost completely relaxed rings 1 – 3 (EMR in Table 2); slopes factors were not significantly different (1.51±0.06, 1.45±0.09, 1.41±0.03, 1.65±0.07; P>0.05, 1-factor ANOVA). Taprostene induced 95±1.4% relaxation at 440 nM (n=4), and its slope factor (1.66±0.11) was also not significantly different from cicaprost. Carbacyclin induced small contractions between 1 and 14 nM, followed by relaxation at higher concentrations. AFP-07 and cicaprost also completely relaxed ring four preparations with similar sensitivities to rings 1 – 3.

The potent contractile actions of SC-46275 and sulprostone indicate that the mesenteric artery contains an EP3 contractile system (Figure 5b,c). 17-Phenyl PGE2 always showed relaxant activity on rings 1 – 3, whereas on a single ring four preparation contraction proceeding to relaxation was found. We suggest that the different response profiles of the PGE analogues on rings 1 – 3 and ring four are due to the presence of a less sensitive EP4 relaxant system in ring four, and this shifts the balance in favour of EP3 contractile action in ring four.

Guinea-pig aorta

AFP-07, cicaprost, TEI-9063 and taprostene gave monophasic log concentration-response curves on each preparation, with maximum relaxations of greater than 95% (Figure 6); the slope factors were not significantly different (1.18±0.08, 1.19±0.16, 1.26±0.10, 1.13±0.16; n=5 – 6, P>0.05, 1-factor ANOVA). The curve for iloprost between 1 and 50 nM was parallel to that of cicaprost (10 – 80% relaxation); at higher iloprost concentrations the curve was distinctly shallower than that of cicaprost and the mean maximum relaxation was 96±3% (data not shown). In contrast, carbacyclin consistently showed contractile activity between 3 and 43 nM with reversal to relaxation as the concentration was increased. Generating tone with U-46619 (4 – 10 nM) in the absence of GR 32191 resulted in even more marked contractile responses to carbacyclin (3 – 13 nM) (data not shown).

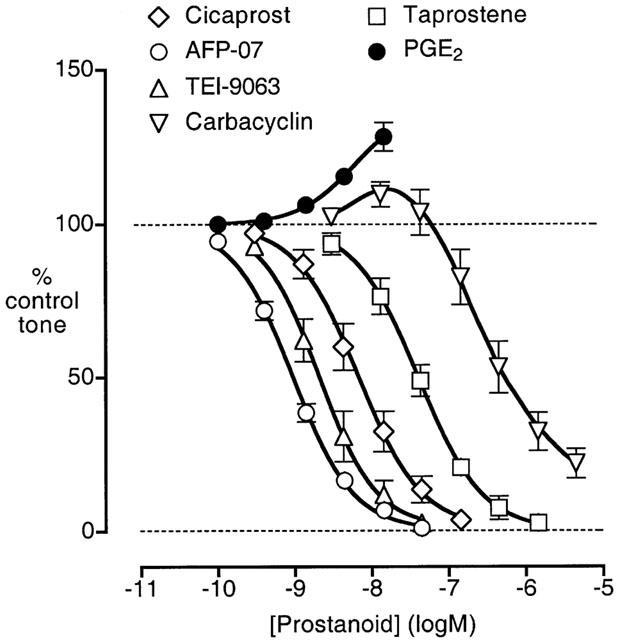

Figure 6.

Log concentration-response curves for PGE2 and prostacyclin analogues on guinea-pig aorta pre-contracted with phenylephrine. GR 32191 (0.2 μM) was present in all tests. Values are mean±s.e.mean (n=4 – 5).

From our previous study (Jones et al., 1998) of the EP3 contractile system in guinea-pig aorta, we know that PGE2, 17-phenyl PGE2, SC-46275 and sulprostone all interact synergistically with either phenylephrine or U-46619. In the current study, we only determined the action of low concentrations of PGE2 (Figure 6).

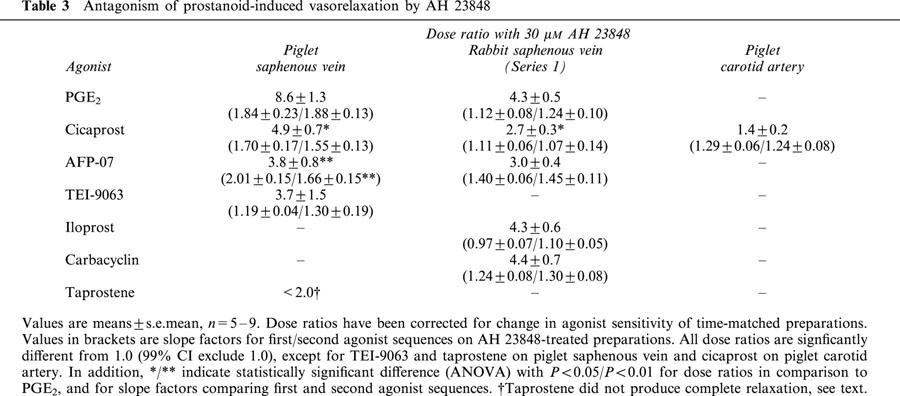

Antagonist studies with AH 23848

The effects of the EP4 antagonist AH 23848 at a single concentration of 30 μM on prostanoid-induced relaxation of piglet saphenous vein, rabbit saphenous vein and piglet carotid artery were determined (Table 3). On time-matched control preparations, the slope factors for the first and second dose sequences of each of the agonists were not significantly different (repeated-measures 2-factor ANOVA, data not shown). Correspondingly, on the AH 23848-treated preparations there were no differences in slope factors, with the exception of AFP-07 on piglet saphenous vein where the slope factor was smaller in the presence of AH 23848 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Antagonism of prostanoid-induced vasorelaxation by AH 23848

On piglet saphenous vein, the pA2 value for AH 23848 block of PGE2-induced relaxation was 5.4, the same as reported by Coleman et al. (1994). Dose ratios for AFP-07, cicaprost or TEI-9063 as agonist were significantly smaller than that for PGE2. However, antagonism of TEI-9063-induced relaxation was quite variable. There was essentially no block on three preparations that were sensitive to TEI-9063 (IC50=7.7, 11.5 and 12.8 nM), while on three less sensitive preparations (IC50=48, 66 and 263 nM) dose ratios of 3.9, 6.9 and 9.1 were found. Taprostene-induced relaxation of the piglet saphenous vein was not affected by AH 23848 (Figure 2f); as a positive control in the same preparations, AH 23848 blocked the relaxation induced by PGE2 in the presence of the cumulative concentration of taprostene (3.33 μM), giving a mean dose ratio of about 12.

On rabbit saphenous vein (series 1), AH 23848 blocked relaxation to PGE2 with a pA2 of 5.1, close to the value of 5.0 reported by Lydford et al. (1996). Iloprost and carbacyclin were blocked to the same extent as PGE2, whereas block of AFP-07 and cicaprost-induced relaxation was slightly less, and the difference just achieved statistical significance for cicaprost (P<0.05, 1-factor ANOVA).

On piglet carotid artery, AH 23848 did not block cicaprost-induced relaxation (95% CI for dose ratio includes 1.0).

Discussion

We contend that cicaprost and AFP-07, which are thought to be selective agonists for prostanoid IP1 receptors, have moderately potent agonist activity at EP4 receptors. Furthermore, these prostacyclin analogues exhibit both types of activity over similar concentration ranges on two established EP4 preparations, the piglet saphenous vein and the rabbit saphenous vein. However, before we discuss the evidence in detail, we must consider whether any of our data are compromised by the presence of EP3 contractile systems in the preparations examined.

The presence of EP3 contractile systems

Our previous studies have shown that the EP3 contractile systems of human pulmonary artery and guinea-pig aorta respond to PGE analogues with a potency order: SC-46275>sulprostone>PGE2=17-phenyl PGE2 (Qian et al., 1994; Jones et al., 1998). Reversal of this order indicates the presence of EP1 receptors (Lawrence et al., 1992). We now report an EP3 ranking for the above PGE analogues for contraction of piglet carotid artery, rabbit saphenous vein and rabbit mesenteric artery, with SC-46275 being active in the low nanomolar range. About half of the rabbit saphenous vein preparations showed no contractile response to low concentrations of either SC-46275 or sulprostone, while relaxation occurred at higher concentrations. These non-responders may lack an EP3 contractile system. Alternatively, the EP3 contractile activities of SC-46275 and sulprostone may be balanced by their relaxant activities. The latter activities are presumably due to activation of EP4 receptors, but there is no information in the literature to support this proposal. Sulprostone had been previously reported to have weak relaxant activity on the rabbit saphenous vein (threshold at 1 μM, IC50 ∼ 10 μM; Lydford et al., 1996); in our experiments we see about 5 fold higher sensitivity to sulprostone. Sulprostone was at least 250 times less potent than PGE2 in elevating cyclic AMP in Chinese hamster ovary cells (native EP4 receptor) (Crider et al., 2000). Binding studies also showed low affinity for sulprostone on cloned EP4 receptors: Ki=7.7 μM and >10 μM for man and mouse (Abramovitz et al., 2000; Kiriyama et al., 1997).

We can find no evidence for an EP3 contractile system in piglet saphenous vein, and this agrees with published data for sulprostone (Coleman et al., 1994) and the highly potent EP3 agonist 16,16-dimethyl PGE2 (Milne et al., 1995). However, the presence of an insensitive EP3 contractile system cannot be excluded, since both SC-46275 and sulprostone again show significant relaxant activity, which may be due to EP4 agonism (see previous Discussion).

Returning to the prostacyclin analogues used in our study, it seems reasonable to conclude that the contractile activities shown by carbacyclin on the piglet carotid artery, rabbit mesenteric artery and guinea-pig aorta are due to activation of EP3 receptors. Consequently, its IP1 relaxant potency may be significantly underestimated, thereby making it of little use in our comparison of EP4 and IP1 relaxant systems. Iloprost may also have weak EP3 agonist activity on the three IP1 preparations, but we feel that its EMRs (calculated from IC50 values) are fairly accurate estimates of IP1 agonist potency. We may note that on human cloned EP3 receptors the ranking of binding affinity is PGE2>carbacyclin>iloprost>cicaprost (Ki=0.33, 14, 56, 260 nM) (Abramovitz et al., 2000).

IP1 agonist potencies on pig carotid artery, rabbit mesenteric artery and guinea-pig aorta

A fairly consistent picture emerges for the relative potencies of the prostacyclin analogues on the three putative IP1 preparations, pig carotid artery, rabbit mesenteric artery and guinea-pig aorta (Table 2). The ranking AFP-07>TEI-9063⩾cicaprost>iloprost>taprostene is similar to that found for relaxation of human pulmonary artery, a highly sensitive IP1 system (IC50=0.6 nM): EMR=(no value for AFP-07), 0.71, 1.0, 2.4, 23 respectively (Jones et al., 1997). In the present study, AFP-07 was about 15 times more potent than iloprost, in agreement with the 8 fold greater potency of AFP-07 over iloprost in elevating cyclic AMP in the mouse cloned IP1 receptor system originally reported by Chang et al. (1997).

We suggest that the submaximal relaxation elicited by taprostene on piglet carotid and rabbit mesenteric arteries is probably due to its low efficacy on IP1 receptor systems. Taprostene's complete relaxation of the human pulmonary artery preparation (Jones et al., 1997) is then accounted for by the high IP1 sensitivity of this preparation. It is possible however that taprostene's incomplete relaxation is due to its IP1 full agonist being opposed by its EP3 contractile action. Unfortunately, there is no information in the literature on the agonist activity of taprostene in a functional system containing only EP3 receptors. Even the guinea-pig vas deferens, the archetypal EP3 preparation, has a moderately sensitive IP1 system that enhances transmitter release from the sympathetic nerves and consequently opposes reduced transmitter release due to EP3 agonism (Tam et al., 1997). Taprostene (10 – 1500 nM) showed IP1 agonist activity on the vas deferens, with a maximum some 50% of that of cicaprost and no reversal of response with increasing concentration as seen with cicaprost and iloprost (i.e. taprostene showed no obvious EP3 agonism).

Activities of prostacyclin analogues on piglet and rabbit saphenous veins

The piglet saphenous vein appears to contain an IP1 relaxant system based on the smaller block of cicaprost and AFP-07-induced relaxations by AH 23848 in comparison to PGE2 and the inability of AH 23848 to block (submaximal) relaxation induced by taprostene. In addition, a high concentration of taprostene did not inhibit relaxation induced by PGE2, indicating that taprostene is not a partial agonist on the EP4 system. As argued earlier, taprostene could be a partial agonist at IP1 receptors. However, an alternative (or even additional) explanation is that maximal activation of the IP1 system does not result in complete relaxation. Evidence to distinguish these possibilities is difficult to obtain since the other prostacyclin analogues tested activate both the EP4 and IP1 systems to induce relaxation. For example, the failure of taprostene (acting as an IP1 partial agonist) to block cicaprost-induced relaxation (Figure 2e) may be explained by the ability of cicaprost to activate the EP4 system.

It appears that AFP-07 and cicaprost activate both EP4 and IP1 receptors on piglet saphenous vein starting at around 1 and 4 nM respectively, while taprostene exhibits matching IP1 agonist activity around 30 nM. These crude potency estimates on the IP1 system agree reasonably well with potencies on the piglet carotid artery and the other IP1 preparations given in Table 2. In the case of TEI-9063's action on piglet saphenous vein, we can explain the variability in both the location/slope of its log concentration-response curve and its antagonism by AH 23848 by making two assumptions. Firstly, reduced sensitivity of the EP4 relaxant system results in a roughly parallel right-shift of the agonist log concentration-response curve, whereas reduced sensitivity of the IP1 relaxant system results in a decreased maximum accompanied by a modest right-shift (see Figure 2b). Of course, these profiles may not be rigidly associated when individual preparations are considered. Secondly, TEI-9063 has a moderately high specificity for IP1 receptors over EP4 receptors: IP1 agonist potency similar to cicaprost and EP4 agonist potency about 1000 times less than PGE2 would fit our findings. Therefore, high responsiveness to TEI-9063 (range=3 – 100 nM), coupled with minimal block by AH 23848, implies that relaxation is mediated predominantly by the IP1 system. In addition, it is possible for TEI-9063 (and AFP-07 and cicaprost) to elicit full relaxation via IP1 agonism alone, if their efficacies are higher than that of taprostene. In contrast, low responsiveness (range=10 – 3000 nM)/shallow slope of the log concentration-response curve/moderate AH 23848 block would then reflect the agonist activity of TEI-9063 on both IP1 and EP4 receptors, with the IP1 component curve having a low maximum.

On rabbit saphenous vein, the sensitivity to PGE2 was consistent and similar in the two series of experiments, whereas sensitivities to AFP-07, cicaprost and especially TEI-9063 were considerably greater in S2 compared to S1 experiments. The simplest explanation for these findings is the occurrence of a selective increase in IP1 receptor density and/or IP1 receptor-effector coupling in S2 preparations. In S1 experiments, 30 μM AH 23848 produced similar block of PGE2, AFP-07, iloprost and carbacyclin and a slightly lower block of cicaprost, again implying that the prostacyclin analogues activate EP4 receptors. However, the dose ratios were small (range=2.5 – 6.5) and we must be cautious in our assumptions. Nevertheless, it does appear that AFP-07 and cicaprost are moderately potent agonists on rabbit EP4 receptors.

In making these proposals, we appreciate the limitations of AH 23848 as an EP4 antagonist. In addition to potential errors in weighing small quantities of AH 23848 for use in each day's experiments, it has a low affinity: pA2=5.4 on piglet saphenous vein (Coleman et al., 1994) and 5.0 on rabbit saphenous vein (Lydford et al., 1996). Although Coleman et al. accorded workable specificity to AH 23848 based on pA2 <4.5 (30 μM AH 23848) for β-adrenoceptors in piglet saphenous vein and EP1, EP2 and EP3 receptors in other functional systems, its specificity may not be that high. Accordingly, Abramovitz et al. (2000) obtained pKi values of 4.0 – 4.5 for AH 23848 on cloned human DP, EP1, EP2, EP3, FP, IP1 and TP receptors. In defence of AH 23848 as an EP4 receptor antagonist, in piglet carotid artery at 30 μM it had no significant effect on cicaprost-induced relaxation (dose ratio <2.0), allowing us also to quote a pA2 <4.5 for the IP1 receptor.

Overall considerations

The data we have collected, complemented by the human ligand binding studies of Abramovitz et al. (2000), point to the ability of certain prostacyclin analogues to act as potent agonists at both EP4 and IP1 receptors. In the mid-1980s, we were the first to promote cicaprost as a more specific probe of the IP1 receptor than either carbacyclin or iloprost; from our current data we now caution its use, and that of AFP-07, on preparations where EP4 receptors are also present. Two of these preparations are the piglet saphenous vein and rabbit saphenous vein, which may show variability in the responsiveness of their EP4 and IP1 relaxant systems.

In the case of TEI-9063, we bestow moderately high IP1/EP4 agonist specificity, but this isocarbacyclin is also a potent EP1 agonist (Jones et al., 1997). In contrast, taprostene does not show significant EP1 agonism, but its moderate potency and possible partial agonism at IP1 receptors are shortcomings. Taprostene may however be a useful lead to a potent and highly selective IP1 receptor agonist.

Acknowledgments

We thank the pharmaceutical companies mentioned in Methods for their generous gifts of prostanoids. This work was supported by a Direct Grant for Research (97.1.64) and a UK/HK Joint Research Scheme Award (JRS 98/22).

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CI

confidence interval

- EMR

equi-effective molar ratio

- IC50

concentration producing half-maximal inhibition

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

References

- ABRAMOVITZ M., ADAM M., BOIE Y., CARRIÈRE M.-C., DENIS D., GODBOUT C., LAMONTAGNE S., ROCHETTE C., SAWYER N., TREMBLAY N.M., BELLEY M., GALLANT M., DUFRESNE C., GAREAU Y., RUEL R., JUTEAU H., LABELLE M., OUIMET N., METTERS K.M. The utilization of recombinant prostanoid receptors to determine the affinities and selectivities of prostaglandins and related analogs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1483:285–293. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRITTAIN R.T., BOUTAL L., CARTER M.C., COLEMAN R.A., COLLINGTON E.W., GEISOW H.P., HALLETT P., HORNBY E.J., HUMPHREY P.P.A., JACK D., KENNEDY I., LUMLEY P., MCCABE P.J., SKIDMORE I.F., THOMAS M., WALLIS C.J. AH 23848: a thromboxane receptor-blocking drug that can clarify the pathophysiological role of thromboxane A2. Circulation. 1985;72:1208–1218. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.6.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUNTING S., GRYGLEWSKI R., MONCADA S. Arterial walls generate from prostaglandin endoperoxides a substance (prostaglandin X) which relaxes strips of mesenteric and coeliac arteries and inhibits platelet aggregation. Prostaglandins. 1976;12:897–913. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(76)90125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAMBERS J.M., CLEVELAND W.S., KLEINER B., TUKEY P.A. Graphical Methods for Data Analysis. Boston: Duxbury Press; 1983. Studying two-dimensional data; pp. 75–127. [Google Scholar]

- CHANG C.S., NEGISHI M., NAKANO T., MORIZAWA Y., MATSUMURA Y., ICHIKAWA A. 7,7-Difluoroprostacyclin derivative, AFP-07, a highly selective and potent agonist for the prostacyclin receptor. Prostaglandins. 1997;53:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(97)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLEMAN R.A., GRIX S.P., HEAD S.A., LOUTTIT J.B., MALLETT A., SHELDRICK R.L.G. A novel inhibitory prostanoid receptor in piglet saphenous vein. Prostaglandins. 1994;47:151–168. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(94)90084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLEMAN R.A., KENNEDY I., SHELDRICK R.L.G. New evidence with selective agonists for the subclassification of PGE2-sensitive receptors. Adv. Prost. Thromboxane Leukot. Res. 1987;17A:467–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRIDER J.Y., GRIFFIN B.W., SHARIF N.A. Endogenous EP4 prostaglandin receptors coupled positively to adenyl cyclase in Chinese hamster ovary cells: pharmacological characterization. Prost. Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2000;62:21–26. doi: 10.1054/plef.1999.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DONG Y.J., JONES R.L., WILSON N.H. Prostaglandin E receptor subtypes in smooth muscle: agonist activities of stable prostacyclin analogues. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986;87:97–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER P.J. Characterisation of prostanoid relaxant/inhibitory receptors (ψ) using a highly selective agonist, TR4979. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986;87:45–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLASS G.V., HOPKINS K.D.Multiple comparisons and trend analysis Statistical Methods in Education and Psychology 1995Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 444–481.3nd Edition, pp [Google Scholar]

- JONES R.L., QIAN Y.M., CHAN K.M., YIM A.P.C. Characterization of a prostanoid EP3 receptor in guinea-pig aorta: partial agonist action of the non-prostanoid ONO-AP-324. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:1288–1296. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES R.L., QIAN Y.M., WONG H.N.C., LAM W.L., CHAN H.W., YIM A.P.C., HO J.K.S. Relaxant actions of nonprostanoid prostacyclin mimetics on human pulmonary artery. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1997;29:525–535. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199704000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRIYAMA M., USHIKUBI F., KOBAYASHI T., HIRATA M., SUGIMOTO Y., NARUMIYA S. Ligand binding specificities of the eight types and subtypes of the mouse prostanoid receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:217–224. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAWRENCE R.A., JONES R.L., WILSON N.H. Characterization of receptors involved in the direct and indirect actions of prostaglandins E and I on the guinea-pig ileum. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;105:271–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUMLEY P., WHITE B.P., HUMPHREY P.P.A. GR 32191, a highly potent and specific thromboxane A2 blocking drug on platelets and vascular and airways smooth muscle in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989;97:783–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LYDFORD S.J., MCKECHNIE K.C.W., DOUGAL I.G. Pharmacological studies on prostanoid receptors in the rabbit isolated saphenous vein: a comparison with the isolated rabbit ear artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICHEL G., SEIPP U. In vitro studies with the stabilized epoprostenol analogue taprostene. Drug Res. 1990;40:817–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILNE S.A., ARMSTRONG R.A., WOODWARD D.F. Comparison of the EP receptor subtypes mediating relaxation of the rabbit jugular and pig saphenous veins. Prostaglandins. 1995;49:225–237. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(95)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEGISHI M., HASHIMOTO H., YATSUNAMI K., KUROZUMI S., ICHIKAWA A. TEI-9063, a stable and highly specific prostacyclin analogue for the prostacyclin receptor in mastocytoma P-815 cells. Prostaglandins. 1991;42:225–237. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(91)90112-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QIAN Y.M., JONES R.L., CHAN K.M. Potent contractile actions of prostanoid EP3 receptor agonists on human isolated pulmonary artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;113:369–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb16997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAVAGE M.A., MOUMMI C., KARABATSOS P.J., LANTHORN T.H. SC-46275: a potent and highly selective agonist at the EP3 receptor. Prost. Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1993;49:939–943. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(93)90179-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHNEIDER J., FRIDERICHS E., KÖGEL B., SEIPP U., STAHLBERG H.-J., TERLINDEN R., HEINTZE K. Taprostene sodium. Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 1993;11:479–500. [Google Scholar]

- TAM F.S.F., CHAN K.M., BOURREAU J.P., JONES R.L. The mechanisms of enhancement and inhibition of field stimulation responses of guinea-pig vas deferens by prostacyclin analogues. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:1413–1421. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TYMKEWYCZ P.M., JONES R.L., WILSON N.H., MARR C.G. Heterogeneity of thromboxane A2 (TP-) receptors: evidence from antagonist but not agonist potency measurements. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;102:607–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WISE H., JONES R.L. Prostacyclin and Its Receptors. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2000. The development of prostacyclin analogues; pp. 29–58. [Google Scholar]