Abstract

The effects of unfractionated heparin (UH) and a selectively O-desulphated derivative of heparin (ODSH), lacking anticoagulant activity, on the adhesion of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (HPBMNC) to human stimulated umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), were investigated.

For comparison, the effects of poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA), a large polyanionic molecule without sulphate groups and two different molecular weight sulphated dextrans (DS 5 k and DS 10 k) were studied.

UH (50 – 1000 u ml−1) significantly (P<0.05) inhibited the adhesion of HPBMNC to HUVECs, stimulated with IL-1β (100 u ml−1), TNF-α (1000 u ml−1) or LPS (100 μg ml−1), when the drugs were added together with stimuli to HUVECs and coincubated for 6 h. Such effects on adhesion occurred with limited influence on expression of relevant endothelial adhesion molecules (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1).

UH (100 – 1000 u ml−1), when added to prestimulated HUVECs, significantly (P<0.05) increased adhesion of mononuclear cells to endothelium at the higher concentrations tested, without any effect on adhesion molecule expression. In contrast, the opposite effect was observed when human polymorphonuclear leucocyte adhesion was examined, under the same experimental conditions, suggesting that the observed potentiation of HPBMNC adhesion is cell specific.

The effects of UH on HPBMNC adhesion were shared by the non-anticoagulant ODSH (600 – 6000 μg ml−1) but not by sulphated dextrans or PGA (300 – 6000 μg ml−1).

Heparin affects the adhesion of HPBMNC to stimulated endothelium, in both an inhibitory and potentiating manner, effects which are unrelated to its anticoagulant activity and not solely dependent on molecular charge characteristics.

Keywords: Heparin, O-desulphated heparin, polyanionic charge, sulphation, adhesion, mononuclear cells, endothelium, adhesion molecules, anticoagulant

Introduction

The role of endogenous heparin, synthesized exclusively by mast cells, is poorly understood but along with other glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) it is known to modulate a variety of biological functions. However, a possible immunomodulatory function is suggested, as increasing evidence, both experimental and clinical, indicates heparin to possess a range of anti-inflammatory properties (reviewed by Jaques, 1979; Tyrrell et al., 1999). Many of these effects may be mediated through the ability of this large, negatively charged molecule to bind and inactivate an array of inflammatory proteins, including certain complement components (Matzner et al., 1984; Strunk & Colten, 1976), chemokines (Miller & Krangel, 1992) and products of activated granulocytes (Fredens et al., 1991; Redini et al., 1988; Walsh et al., 1991b) as well as thrombin, a known proinflammatory mediator which acts through PAR-1 receptor activation. In addition, heparin is known to bind a number of adhesion molecules involved in leucocyte trafficking into tissues, including mac-1 (CD11b/CD18; Diamond et al., 1995) and L-selectin (Koenig et al., 1998) on inflammatory cells and the endothelial adhesion molecules P-selectin (Revelle et al., 1996; Skinner et al., 1991) and platelet endothelial adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1; Watt et al., 1993). Accordingly, heparin and related molecules have been found to inhibit leucocyte-endothelial interactions both in vitro (Bazzoni et al., 1992; Lever et al., 2000; Silvestro et al., 1994) and in vivo (Ley et al., 1991; Salas et al., 2000; Xie et al., 1997), as well as inflammatory cell accumulation in tissue sites such as the lung (Sasaki et al., 1993; Seeds et al., 1993), skin (Teixeira & Hellewell, 1993) and peritoneal cavity (Nelson et al., 1993).

The precise mechanisms by which heparin modulates leucocyte recruitment are not fully understood. The closely related molecule heparan sulphate is, however, found on vascular endothelial cells, where it is considered to play a role in preventing non-specific adhesion of blood elements since it is now known that certain inflammatory cells, most notably lymphocytes, release heparan-degrading enzymes in order to aid their extravasation (reviewed by Vlodavsky et al., 1992) and that these enzymes are inhibited by heparin (Bar-Ner et al., 1987). Indeed, the inhibitory effects of administered heparin on lymphocyte orchestrated processes such as graft vs host reactions (Gorski et al., 1991; Lider et al., 1989), delayed type hypersensitivity reactions (Sy et al., 1983) and allergic encephalomyelitis (Lider et al., 1990; Willenborg & Parish, 1988) are thought to involve heparanase inhibition. However, there is also evidence that heparin can affect the entry of lymphocytes to lymph nodes and Peyer's patches (Bellavia et al., 1980), having potential consequences with respect to the recirculation of these cells. The aim of the present study was to examine whether heparin can influence the adhesion of mononuclear cells to vascular endothelial cells, a possible mechanism by which heparin might be active in reducing inflammatory responses in vivo.

Unfractionated heparin and several related molecules were investigated for their effects on the adhesion of human mixed mononuclear cell preparations to cytokine and LPS-stimulated endothelial cells. A structurally modified heparin, lacking in anticoagulant activity (Fryer et al., 1997) due to the selective removal of O-sulphate groups, was used in order to assess the contribution of this property of the parent molecule to any observed effects. Poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA), a linear polyanionic molecule, was also tested, with a view to investigating the importance of charge characteristics to the actions of heparin. Given that heparin is a heavily sulphated molecule, whereas PGA does not possess these functional groups, we went on to consider the role of sulphate-derived negative charges through the use of dextran sulphate preparations of varying molecular weights.

Methods

Preparation of HUVECs

HUVECs, at passage five or below, were cultured to confluency in endothelial basal medium (MCDB 131), supplemented with foetal bovine serum (2%), hydrocortisone (1 ng ml−1), gentamicin (50 μg ml−1), amphotericin-B (50 ng ml−1) and human epidermal growth factor (10 ng ml−1), in the central 60 wells of flat bottomed 96 well plates (200 μl culture medium per well; 5% CO2; 37°C). Monolayers were stimulated by the addition of 22 μl per well of a solution of IL-1β, TNF-α or bacterial LPS, prepared in culture medium at 10 fold the final concentration required in the well, for 6 h.

Isolation of leucocytes

Peripheral venous blood was collected from healthy volunteers (n=6) into citrated tubes (1 volume in 10 acid citrate dextrose), before being transferred to Accuspin tubes (containing Histopaque 1077) for centrifugation at 1000 × g for 10 min. The resultant plasma layer was carefully removed and HPBMNCs, contained within a distinct opaque layer, were carefully aspirated. Where necessary, contaminating red blood cells were lysed hypotonically (0.83% ammonium chloride, 10 min, ambient temperature). Cells were washed three times in modified Hank's Balanced Salts Solution (HBSS, without Ca2+ and Mg2+) by centrifugation at 250 × g for 5 min. Samples of the cell suspension were removed and purity and viability assessed. Cell suspensions used were found to be more than 98% viable and to consist of not less than 95% mononuclear cells, with neutrophils being the main contaminating leucocyte. Within mononuclear cell populations, the mean ratio of lymphocytes to monocytes was approximately five. In some experiments, following removal of HPBMNCs, the remaining blood fraction was purified further in order to obtain autologous polymorphonuclear leucocyte (PMN) populations. In short, the cell mixture found below the Histopaque layer was mixed with an equal volume of dextran solution (Hespan, containing 18% PBS and 2% ACD) and centrifuged for 15 min at 20 × g to remove erythrocytes. The supernatant was further centrifuged (7 min, 175 × g) to collect the PMNs, remaining red blood cells were lysed as before and cells were washed three times in modified HBSS. PMN preparations isolated in this manner were found to be more than 98% viable and to contain at least 95% neutrophils, contaminating cells typically being eosinophils.

51Cr-labelling of leucocytes

HPBMNC or PMN pellets were incubated with aqueous sodium 51chromate (37 kBq per 106 viable cells) for 60 min at room temperature. Excess radiolabel was removed by three washes in modified HBSS before cells were resuspended at a final concentration of 106 ml−1 in complete HBSS (with Ca2+ and Mg2+). Cell viability was unaffected by this process.

Adhesion assay

Leucocyte-endothelial adhesion was examined using an assay described previously (Lever et al., 2000). Briefly, HUVEC monolayers, stimulated with cytokines or LPS in the absence or presence of the study drugs (see below), were washed with warmed HBSS prior to addition of 200 μl radiolabelled leucocyte suspension per well. Preliminary experiments were carried out to establish optimum concentrations of and exposure time to stimuli. A 6 h stimulation period, with IL-1β (100 u ml−1), TNF-α (1000 u ml−1) or LPS (100 μg ml−1), was selected for use in the study. Plates were returned to the incubator for 30 min, following which, non-adherent cells were removed by gentle aspiration and washing with warmed HBSS. Wells were examined microscopically and, upon confirmation of monolayer integrity, adherent cells were lysed by addition of 200 μl detergent solution (1% Igepal) per well. One hundred μl samples were transferred to scintillation vials and γ-counted alongside 100 μl samples of the original radiolabelled cell suspension (input). The number of adherent cells was calculated as the percentage of input counts present in sample counts, corrected for background radioactivity. Compounds under investigation (unfractionated heparin (UH, 0 – 1000 u ml−1; specific anticoagulant activity ≈180 u mg−1), O-desulphated heparin (ODSH, 0 – 6000 μg ml−1), poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA, 0 – 6000 μg ml−1) or dextran sulphates of molecular weight 5000 or 10 000 (DS 5 k or DS 10 k, respectively, 0 – 6000 μg ml−1)) were added to monolayers, either immediately prior to endothelial stimuli or, to stimulated HUVECs immediately prior to the addition of leucocytes.

Treatment of data

Results are expressed either as per cent adhesion or, when examining the effects of drugs on adhesion, as per cent of control, that is, adhesion observed in control wells which had received stimuli but no test compounds. Data were analysed by ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's test.

Enzyme linked immunosorbant assay

In these experiments, HUVEC monolayers were treated identically to those used in adhesion assays, with respect to stimulation, addition of test compounds (in this case, UH only) and incubation times. Following the relevant treatments, plates were washed three times with a blocking solution of 5% w v−1 low fat powder milk in PBS, in order to eliminate non specific protein binding. Primary monoclonal antibodies (mouse anti-human ICAM-1 IgG, mouse anti-human VCAM-1 IgG or control mouse IgG1; all at a concentration of 1 μg ml−1) were added and plates incubated for 60 min at room temperature. Cells were again washed three times with blocking solution, before secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate, 1 : 10 000 dilution) was added and plates incubated for a further 60 min at room temperature. Monolayers were washed thoroughly with PBS and 100 μl TMB substrate system (3,3′5.5′-tetramethylbenzidine) were added to each well. Plates were incubated for 10 – 15 min, until a blue colour developed and the reaction was quenched by addition of 2 M sulphuric acid. Plates were analysed colorimetrically at 450 nm in an Anthos HTIII plate reader. Readings from wells which received no primary antibody were subtracted from test values.

Treatment of results

Results are expressed as per cent of control values, that is, readings from stimulated wells which had received no UH. Data were again analysed by ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's test.

Reagents

Cryopreserved HUVECs and all culture media were obtained from BioWhittaker Ltd. Milton Keynes, Bucks, U.K.; Aqueous 51sodium chromate from Amersham Life Science, U.K.; Accuspin Histopaque 1077, acid citrate dextrose (ACD), Percoll, Hank's balanced salts solutions, phosphate buffered saline, horseradish peroxidase linked goat anti-mouse IgG, TMB liquid substrate system, acid citrate dextrose, Igepal, poly-L-glutamic acid, dextran sulphates, bacterial (E. Coli) LPS (serotype 0111:B4) from Sigma-Aldrich Company Ltd. U.K.; human recombinant IL-1β; human recombinant TNF-α; mouse anti-human ICAM-1 IgG (clone BBIG-I1), mouse anti-human VCAM-1 IgG (clone BBIG-V1) and control mouse IgG1 from R&D Systems Ltd. U.K.; Hespan from Du Pont Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Letchworth, Herts. U.K.; UH (Multiparin) from CP Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Wrexham, North Wales, U.K.; O-desulphated heparin was a kind gift from Dr T. Kennedy, Carolinas Medical Health Care Foundation, Charlotte, NC, U.S.A.

Results

A 6 h exposure of HUVEC monolayers to IL-1β (100 u ml−1), TNF-α (1000 u ml−1) or LPS (100 μg ml−1) was found to significantly enhance the subsequent adhesion of HPBMNC to these cells (Figure 1a), commensurate with upregulation of the endothelial adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Effect of endothelial stimulation on HPBMNC adhesion and expression of adhesion molecules. HUVECs were stimulated with IL-1β (100 u ml−1), TNF-α (1000 u ml−1) or LPS (100 μg ml−1) for 6 h. (a) 51Cr-labelled HPBMNCs were added for 30 min and adhesion was quantified by γ-counting lysates of adherent cells and calculating the percentage of cells added which had adhered. (b) Endothelial ICAM-1 (open bars) and VCAM-1 (closed bars) were measured by ELISA. Data are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean of six separate experiments, each performed in triplicate. *Statistical significance (P<0.05) is indicated.

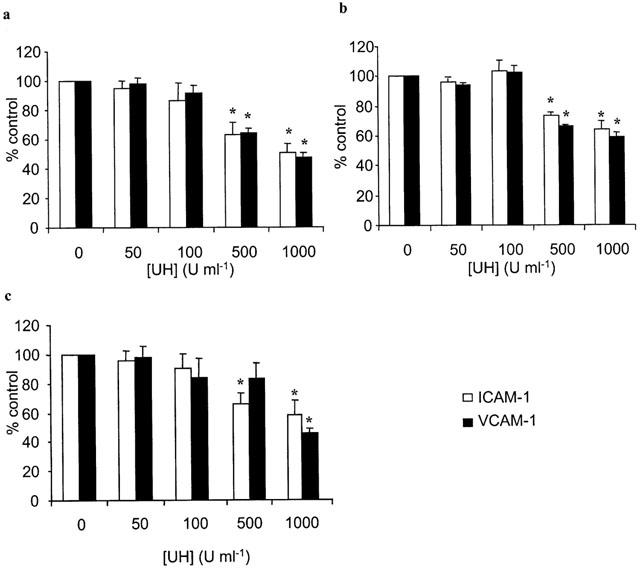

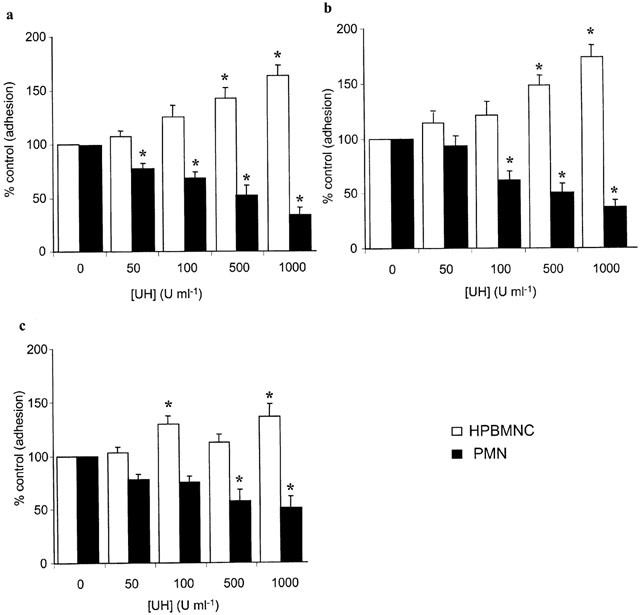

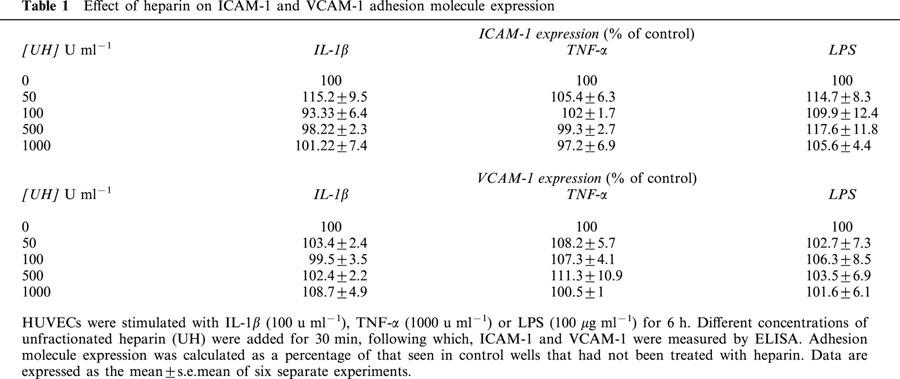

UH, when present during cytokine- or LPS-stimulation of HUVECs was found to inhibit (P<0.05) the subsequent adhesion of HPBMNC to these cells, following washing of the monolayers to remove stimuli and any unbound drug (Figure 2). Treatment of HUVECs with heparin, in this manner, was found to have an effect on the expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on the endothelial cell surface, although inhibition of adhesion was achieved at concentrations lower than those required to elicit this effect on adhesion molecules (Figure 3). However, when UH was added to the assay system with the HPBMNCs, i.e. to HUVECs which had already been stimulated in the absence of any drug treatment, a potentiation of cellular adhesion was observed, with a maximum increase in adhesion of 68.9±21.01% (IL-1β); 55.2±21.03% (TNF-α) and 44.3±12.6% (LPS). In previous studies which examined the effects of heparin on PMN adhesion, we found that adding UH with the PMNs led to a concentration related inhibition of adhesion (Lever et al., 2000). Therefore, we repeated these experiments, comparing HPBMNC adhesion to that of PMNs, isolated from the same blood samples, in parallel. This difference in the effect of UH on adhesion of the two cell types, when included during the adhesion stage of the assay, was confirmed, in that HPBMNC adhesion increased whilst PMN adhesion decreased, in a manner dependent on the concentration of UH (Figure 4). ELISA experiments were carried out which demonstrated this short (30 min) exposure of stimulated HUVECs to UH to have no influence on levels of endothelial ICAM-1 or VCAM-1 expression (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Effect of heparin on HPBMNC adhesion to HUVECs. HUVECs were stimulated with (a) IL-1β (100 u ml−1), (b) TNF-α (1000 u ml−1) or (c) LPS (100 μg ml−1) for 6 h, in the absence and presence of different concentrations of unfractionated heparin (UH). 51Cr-labelled HPBMNCs were added for 30 min. Adhesion was quantified by γ-counting lysates of adherent cells and was calculated as a percentage of that seen in control wells that had not been treated with heparin. Data are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean of six separate experiments, each performed in triplicate. *Statistical significance (P<0.05) is indicated.

Figure 3.

Effect of heparin on endothelial adhesion molecule expression. HUVECs were stimulated with (a) IL-1β (100 u ml−1), (b) TNF-α (1000 u ml−1) or (c) LPS (100 μg ml−1) for 6 h, in the absence and presence of different concentrations of unfractionated heparin (UH). ICAM-1 (open bars) and VCAM-1 (closed bars) were measured by ELISA. Adhesion molecule expression was calculated as a percentage of that seen in control wells that had not been treated with heparin. Data are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean of six separate experiments, each performed in triplicate. *Statistical significance (P<0.05) is indicated.

Figure 4.

Effect of heparin on HPBMNC and PMN adhesion to pre-stimulated HUVECs. HUVECs were stimulated with IL-1β (100 u ml−1), TNF-α (1000 u ml−1) or LPS (100 μg ml−1) for 6 h. 51Cr-labelled HPBMNCs (open bars) or PMNs (closed bars) were added for 30 min, in the absence and presence of different concentrations of unfractionated heparin (UH). Adhesion was quantified by γ-counting lysates of adherent cells and was calculated as a percentage of that seen in control wells† that had not been treated with heparin. Data are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean of six separate experiments, each performed in triplicate. *Statistical significance (P<0.05) is indicated. †(Control PMN adhesion in wells stimulated with IL-1β, TNF-α or LPS was 19.16±1.56, 17.5±1.28 and 14.5±1.06%, respectively. Basal PMN adhesion was 7.74±1.62%).

Table 1.

Effect of heparin on ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 adhesion molecule expression

The selectively O-desulphated derivative of heparin (ODSH), devoid of anticoagulant activity, was found to mimic the effects of the parent molecule on HPBMNC adhesion. When present during cytokine- or LPS-stimulation of HUVECs, ODSH inhibited HPBMNC adhesion to these cells, following removal of unbound drug at the end of the stimulation period. Again, when added to stimulated HUVECs immediately prior to application of HPBMNC, adhesion was augmented (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of O-desulphated heparin on HPBMNC adhesion to HUVECs under different experimental conditions. HUVECs were stimulated with (a) IL-1β (100 u ml−1), (b) TNF-α (1000 u ml−1) or (c) LPS (100 μg ml−1) for 6 h, in the absence or presence of O-desulphated heparin (ODSH). 51Cr-labelled HPBMNCs were added for 30 min, either alone, to HUVECs stimulated in the presence of ODSH (open bars) or, in conjunction with different concentrations of ODSH, to HUVECs stimulated in the absence of the drug (closed bars). Adhesion was quantified by γ-counting lysates of adherent cells and was calculated as a percentage of that seen in control wells that had not been treated with ODSH. Data are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean of six separate experiments, each performed in triplicate. *Statistical significance (P<0.05) is indicated.

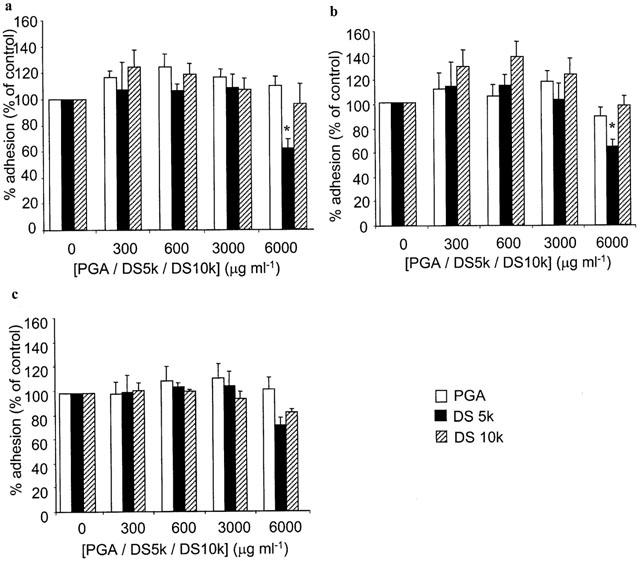

The linear polyanion, PGA, had no effect on adhesion in our experiments, irrespective of the stage it was introduced to the assay. Of the two sulphated dextran preparations tested, DS 10 k had no effect on adhesion (Figure 6). DS 5 k was largely ineffective, although a small inhibitory effect was observed at the highest concentration, following treatment of HUVECs with this compound during stimulation with cytokines (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Effect of charged molecules on HPBMNC adhesion to HUVECs. HUVECs were stimulated with (a) IL-1β (100 u ml−1), (b) TNF-α (1000 u ml−1) or (c) LPS (100 μg ml−1) for 6 h. 51Cr-labelled HPBMNCs were added for 30 min, in the absence and presence of different concentrations of poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA, open bars) or dextran sulphates with molecular weights of 5000 (DS 5 k, closed bars) and 10,000 (DS 10 k, hatched bars), respectively. Adhesion was quantified by γ-counting lysates of adherent cells and was calculated as a percentage of that seen in control wells that had not been treated with PGA or dextrans. Data are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean of six separate experiments, each performed in triplicate. *Statistical significance (P<0.05) is indicated.

Figure 7.

Effect of charged molecules on HPBMNC adhesion to HUVECs. HUVECs were stimulated with (a) IL-1β (100 u ml−1), (b) TNF-α (1000 u ml−1) or (c) LPS (100 μg ml−1) for 6 h, in the absence and presence of different concentrations of poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA, open bars) or dextran sulphates with molecular weights of 5000 (DS 5 k, closed bars) and 10,000 (DS 10 k, hatched bars), respectively. 51Cr-labelled HPBMNCs were added for 30 min and adhesion was quantified by γ-counting lysates of adherent cells and was calculated as a percentage of that seen in control wells that had not been treated with PGA or dextrans. Data are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean of six separate experiments, each performed in triplicate. *Statistical significance (P<0.05) is indicated.

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate that heparin is able to modulate the adhesion of mononuclear cells to vascular endothelial cells in vitro, in addition to its previously reported effects on granulocyte adhesion (Bazzoni et al., 1992; Lever et al., 2000; Silvestro et al., 1994). However, we have found that depending upon the stage at which heparin is introduced to the adhesion assay, differential effects are observed, a phenomenon which would appear to be restricted to mononuclear cells, given that an inhibitory effect on neutrophil adhesion is seen under all the experimental conditions relevant to this study. The reason for this difference is not clear. When heparin is included in the assay during endothelial stimulation, then subjected to a washing stage prior to addition of mononuclear cells, adhesion is inhibited. Part of this effect may be due to binding and inactivation of the stimuli used to activate endothelial cells. However, in our previous studies, using the same endothelial stimuli but looking at neutrophil adhesion, this was not the predominant mechanism of action of heparin and related molecules, given that upregulation of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and E-selectin was affected only minimally by the drug and that inhibition of PMN adhesion to pre-stimulated HUVECs was achieved when heparin was added along with the leucocytes (Lever et al., 2000). Conversely, in the present study, heparin added with the mononuclear cells significantly increased adhesion, in a concentration dependent manner. It is possible that the inhibitory effects of heparin on mononuclear cell adhesion are related to inhibition of VCAM-1 expression on HUVECs, a molecule involved in mononuclear (Osborn et al., 1989) but not neutrophil (Hemler et al., 1987; Walsh et al., 1991a) adhesion. Indeed, in our studies, upregulation of VCAM-1 was found to be more sensitive to the presence of heparin than other endothelial adhesion molecules we have measured. Similarly, the mechanisms by which heparin, in our alternative experimental protocol, increased mononuclear cell adhesion are equally indefinable at this stage. One theory is that heparin has an intercellular ‘bridging' effect, binding structures on the mononuclear cell surface and on the endothelium, thus tethering one cell to the other. Heparin is known to bind readily to endothelium (Hiebert & Jacques, 1976; Bârzu et al., 1986) and possible candidates on the leucocyte surface include the adhesion molecule L-selectin, which is known, physiologically, to interact with heparan sulphate on the endothelial cell surface (Giuffrè et al., 1997) and to bind heparin (Koenig et al., 1998). However, if this were the case, one might expect the same effect to occur with neutrophils when, in fact, the opposite is seen. Moreover, binding of the integrin adhesion molecule mac-1 (Diamond et al., 1995) on neutrophils has been suggested to be at least partially responsible for the inhibitory effects of heparin on neutrophil adhesion (Salas et al., 2000; Silvestro et al., 1994). It is, however, plausible that such a ‘bridging' effect may depend on the concentration of heparin available in the system and whether soluble or bound. In support of this suggestion, in the first part of our investigation, where inhibition of HPBMNC adhesion was observed, only heparin which had bound to endothelial cells would have been present at the same time as the leucocytes. In our latter experiments, reasonably large amounts of, at least initially, soluble heparin were introduced at the same time as the HPBMNCs.

It is possible that heparin, a large and heterogenous polymer, when bound to endothelium, hinders specific leucocyte-endothelial adhesive interactions through steric interference, whereas molecules of the GAG in solution may be able to facilitate these interactions, as is now established to occur between heparin, basic fibroblast growth factor and its receptor (Schmidt et al., 1999). Given that neutrophils utilize different adhesion mechanisms to mononuclear cells, it does not necessarily follow that such an effect should be universal to all inflammatory cells.

The observed effects of unfractionated heparin on mononuclear cell adhesion, both inhibitory and augmentative, were shared by a selectively O-desulphated derivative of the GAG. As this molecule lacks the anticoagulant activity of the parent molecule, these data indicate that effects on mononuclear cell adhesion are separable from this property, as has been found to be the case with regard to many of the effects of heparin on inflammatory functions, including neutrophil adhesion (Lever et al., 2000), delayed type hypersensitivity reactions (Sy et al., 1983), and eosinophil trafficking (Seeds & Page, 2001). Moreover, unfractionated heparin has the ability to bind directly to serine proteases such as thrombin, in addition to its well established capacity to catalyze the inactivation of thrombin by antithrombin III (Damus et al., 1973). Given that thrombin is, in itself, a proinflammatory mediator, as well as the fact that haemostasis and inflammation are closely linked processes, this provides a further mechanism by which unfractionated heparin might be anti-inflammatory. However, since heparin molecules which lack the ability to bind thrombin and/or antithrombin III retain anti-inflammatory effects, both in vitro and in vivo, additional mechanisms must be involved (Ahmed et al., 1997; 2000; Campo et al., 1999).

In order to examine the contribution of anionic charge and, more specifically, sulphate-derived charge to the effects of heparin in our assay, we carried out the same experiments using the polyanionic molecule PGA and observed no effects on adhesion under any of the experimental conditions, suggesting that negative charge alone is not responsible for the effects of heparin. Again, this observation is in accordance with previous reports, which have found PGA to lack the effects of heparin on neutrophil adhesion (Lever et al., 2000) and accumulation of inflammatory cells in vivo (Sasaki et al., 1993; Seeds et al., 1993). As sulphation is deemed to be essential for many of the biological properties of this drug, we examined the effects of two dextran sulphate preparations, of different molecular weights and found, on the whole, these molecules to lack effect in our experiments. These results suggest that specific patterns of sulphation are involved in the effects of heparin on mononuclear cell adhesion, or the relative flexibility of the heparin chain, which exists as an α-helix at physiological pH (Mulloy et al., 1996), possibly rendering sulphate charges more accessible to relevant binding sites on leucocytes, endothelial cells or inflammatory mediators. Whereas dextran sulphates have been reported previously to inhibit neutrophil rolling in rabbit mesenteric venules (Ley et al., 1991), it is likely that such results, obtained in vivo, are a consequence of interference with carbohydrate interactions involved in leucocyte rolling, whereas our results reflect a lack of effect on firm adhesion mechanisms relevant to mononuclear cells. Since O-desulphated heparin behaves in a similar way to unmodified heparin in our assays, it will be interesting to see the effects of a selectively N-desulphated derivative of unfractionated heparin in such experiments, in order to investigate further the significance of sulphate groups and their molecular location with respect to mononuclear cell adhesion.

In summary, we have found the GAG heparin to possess mixed effects on the adhesion of HPBMNCs to stimulated endothelial cells in vitro, which are unrelated to anticoagulant mechanisms and which cannot be explained entirely by the physicochemical nature of the molecule.

Abbreviations

- DS

dextran sulphate

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbant assay

- GAG

glycosaminoglycan

- HPBMNC

human peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- mac-1

macrophage-1 (CD11b/CD18)

- ODSH

O-desulphated heparin

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PECAM-1

platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1

- PGA

poly-L-glutamic acid

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leucocyte

- TMB

3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine

- TNF-α

tumour necrosis factor-α

- UH

unfractionated heparin

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

References

- AHMED T., CAMPO C., ABRAHAM M.K., MOLINAR I.J.F., ABRAHAM W.M., ASHKIN D., SYRISTE T., ANDERSSON L.O., SVAHN C.M. Inhibition of antigen-induced acute bronchoconstriction, airway hyperresponsiveness, and mast cell degranulation by a nonanticoagulant heparin: comparison with a low molecular weight heparin. Am. J. Respir. Cri. Care. Med. 1997;155:1848–1855. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.6.9196085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHMED T., UNGO J., ZHOU M., CAMPO C. Inhibition of allergic late airways responses by inhaled heparin-derived oligosaccharides. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000;88:1721–1729. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.5.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAR-NER M., ELDOR A., WASSERMAN L., MATZNER Y., COHEN I.R., FUKS Z., VLODAVSKY I. Inhibition of heparanase-mediated degradation of extracellular matrix heparan sulfate by non-anticoagulant heparin. Blood. 1987;70:551–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BÂRZU T., VAN RIJN J.L.M.L., PETITOU M., MOLHO P., TOBELEM G., JACQUES P.C. Endothelial binding sites for heparin. Specificity and role in heparin neutralization. Biochem. J. 1986;238:847–854. doi: 10.1042/bj2380847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAZZONI G., NUÑEZ A.B., MASCELLANI G., BIANCHINI P., DEJANA E., DEL MASCHIO A. Effect of heparin, dermatan sulfate, and related oligo-derivatives on human polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1992;121:268–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELLAVIA A., FRANKLIN V., MICKLEM H.S. Effects of dextran sulfate and heparin on lymphocyte localization: Lack of involvement of complement and other plasma proteolytic systems. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1980;2:311–320. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(80)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPO C., MOLINARI J.F., UNGO J., AHMED T. Molecular weight dependent effects of non-anticoagulant heparins on allaergic airways responses. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999;86:549–557. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAMUS P.S., HICKS M., ROSENBERG R.D. Anticoagulant action of heparin. Nature. 1973;246:355–357. doi: 10.1038/246355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIAMOND M.S., ALON R., PARKOS C.A., QUINN M.T., SPRINGER T.A. Heparin is an adhesive ligand for the leukocyte integrin Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) J. Cell. Biol. 1995;130:1473–1482. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.6.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDENS K., DAHL R., VENGE P. In vitro studies of the interaction between heparin and eosinophil cationic protein. Allergy. 1991;46:27–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1991.tb00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRYER A., HUANG Y.-C., RAO G., JACOBY D., MANCILLA E., WHORTON R., PIANTODOSI C.A., KENNEDY T., HOIDAL J. Selective O-desulphation produces nonanticoagulant heparin that retains pharmacologic activity in the lung. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;282:209–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIUFFRÈ L., CORDEY A.-S., MONAI N., TARDY Y., SCHAPIRA M., SPERTINI O. Monocyte adhesion to activated aortic endothelium: Role of L-selectin and heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J. Cell Biol. 1997;136:945–956. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.4.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GORSKI A., LAO M., GRADOWSKA L., NOWACZYK M., WASIK M., LAGODZINSKI Z. New strategies of heparin treatment used to prolong allograft survival. Transplant. Proc. 1991;23:2251–2252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEMLER M.E., HUANG C., TAKADA Y., SCHWARZ L., STROMINGER J.L., CLABBY M.L. Characterisation of the cell surface heterodimer VLA-4 and related peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:11478–11485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIEBERT L.M., JACQUES L.B. The observation of heparin on endothelium after injection. Thromb. Res. 1976;8:195–204. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(76)90262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAQUES L.B. Heparins - anionic polyelectrolyte drugs. Pharmacol. Rev. 1979;31:99–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOENIG A., NORGARD-SUMNICHT K., LINHARDT R., VARKI A. Differential interactions of heparin and heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans with the selectins. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:877–889. doi: 10.1172/JCI1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVER R., HOULT J.R.S., PAGE C.P. The effects of heparin and related molecules upon the adhesion of human polymorphonuclear leucocytes to vascular endothelium in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:533–540. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEY K., CERRITO M., ARFORS K.-E. Sulfated polysaccharides inhibit leukocyte rolling in rabbit mesentery venules. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;260:H1667–H1673. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.5.H1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIDER O., BAHARAV E., MEKERI Y.A., MILLER T., NAPARSTEK Y., VLODAVSKY I., COHEN I.R. Suppression of experimental autoimmune diseases and prolongation of allograft survival by treatment of animals with low doses of heparin. J. Clin. Invest. 1989;83:752–756. doi: 10.1172/JCI113953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIDER O., MEKORI Y.A., MILLER T., BAR-TANA R., VLODAVSKI I., BAHARAV E., COHEN I.R., NAPARSTEK Y. Inhibition of T-lymphocyte heparanase by heparin prevents T cell migration and T cell mediated immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 1990;20:493–499. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATZNER Y., MARX G., DREXLER R., ELDOR A. The inhibitory effect of heparin and related glycosaminoglycans on neutrophil chemotaxis. Thromb. Haemost. 1984;52:134–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER M.D., KRANGEL M.S. Biology and biochemistry of the chemokines: A family of chemotactic and inflammatory cytokines. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 1992;12:17–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLOY B., CRANE D.T., DRAKE A.F., DAVIES D.B. The interaction between heparin and polylysine: a circular dichroism and molecular modelling study. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1996;29:721–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELSON R.M., CECCONI O., ROBERTS W.G., ARUFFO A., LINHARDT R.J., BEVILACQUA M.P. Heparin oligosaccharides bind L- and P-selectin and inhibit acute inflammation. Blood. 1993;82:3253–3258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSBORN L., HESSION C., TIZARD R., VASSALO C., LUHOWSKY S., CHIROSSO G., LOBB R. Direct expression cloning of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), a cytokine-induced endothelial protein that binds to lymphocytes. Cell. 1989;59:1203–1211. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REDINI F., TIXIER J.M., PETITOU M., CHOAY J., ROBERT L., HORNEBECK S. Inhibition of leucocyte elastase by heparin and its derivatives. Biochem. J. 1988;252:515–519. doi: 10.1042/bj2520515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REVELLE B.M., SCOTT D., BECK P.J. Single amino acid residues in the E- and P-selectin epidermal growth factor domains can determine carbohydrate binding specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:16160–16170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALAS A., SANS M., SORIANO A., REVERTER J.C., ANDERSON D.C., PIQUE J.M., PANES J. Heparin attenuates TNF-alpha induced inflammatory response through a CD11b dependent mechanism. Gut. 2000;47:88–96. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.1.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SASAKI M., HERD C.M., PAGE C.P. Effect of heparin and a low-molecular weight heparinoid on PAF-induced airway responses in neonatally immunized rabbits. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMIDT A., VLODAVSKY I., VÖLKER W., BUDDECKE E. Differentiation of coronary smooth muscle cells to a cell cycle-arrested hypertrophic growth status by a synthetic non-toxic heparin-mimicking compound. Atherosclerosis. 1999;147:387–397. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEEDS E.A.M., HANSS J., PAGE C.P. The effect of heparin and related proteoglycans on allergen and PAF-induced eosinophil infiltration. J. Lipid Mediat. 1993;7:269–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEEDS E.A.M., PAGE C.P. Heparin inhibits allergen-induced eosinophil infiltration into guinea-pig lung via a mechanism unrelated to its anticoagulant activity. Pulm. Pharmacol. Therap. 2001;14:111–119. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2000.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SILVESTRO L., VIANO I., MACARIO M., COLANGELO D., MONTRUCCHIO G., PANICO S., FANTOZZI R. Effects of heparin and its desulfated derivatives on leukocyte-endothelial adhesion. Sem. Thromb. Haemost. 1994;20:254–258. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKINNER M.P., LUCAS C.M., BURNS G.F., CHESTERMAN C.N., BERNDT M.C. GMP-140 binding to neutrophils is inhibited by sulfated glycans. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:5371–5374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRUNK R., COLTEN H.R. Inhibition of the enzymatic activity of the first component of complement (C1) by heparin. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1976;6:248–255. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(76)90116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SY M.S., SCHNEEBERGER E., MCCLUSKEY R., GREENE M.I., ROSENBERG R.D., BENACERRAF B. Inhibition of delayed-type hypersensitivity by heparin depleted of anticoagulant activity. Cell Immunol. 1983;82:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(83)90137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TEIXEIRA M.M., HELLEWELL P.G. Suppression by intradermal administration of heparin of eosinophil accumulation but not oedema formation in inflammatory reactions in guinea-pig skin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:1496–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13991.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TYRRELL D.J., HORNE A.P., HOLME K.R., PREUSS J.M.H., PAGE C.P. Heparin in inflammation: Potential therapeutic applications beyond anticoagulation. Adv. Pharmacol. 1999;46:151–208. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VLODAVSKY I., ELDOR A., HAIMOVITZ-FRIEDMAN A., MATZNER Y., ISHAI-MICHAELI R., LIDER O., NAPARSTEK Y., COHEN I.R., FUKS Z. Expression of heparinase by platelets and circulating cells of the immune system: Possible involvment in diapedesis and extravasation. Invasion Metastasis. 1992;12:112–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALSH G.M., MERMOD J.-J., HARTNELL A., KAY A.B., WARDLAW A.J. Human eosinophil, but not neutrophil, adherence to IL-1-stimulated human umbilical vascular endothelial cells is α4β1 (very late antigen-4) dependent. J. Immunol. 1991a;146:3419–3423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALSH R.L., DILLON T.J., SCICCHITANO R., MCLENNAN G. Heparin and heparan sulphate are inhibitors of human leucocyte elastase. Clin. Sci. 1991b;81:341–346. doi: 10.1042/cs0810341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATT S.M., WILLIAMSON J., GENEVIER H., FAWCETT J., SIMMONS D.L., HATZFIELD A., NESBITT S.A., COOMBE D.R. The heparin binding PECAM-1 adhesion molecule is expressed by CD34+ hematopoietic precursor cells with early myeloid and B-lymphoid cell phenotypes. Blood. 1993;82:2649–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLENBORG D.O., PARISH C.R. Inhibition of allergic encephalomyelitis in rats by treatment with sulfated polysaccharides. J. Immunol. 1988;140:3401–3405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIE X., THORLACIUS H., RAUD J., HEDQVIST P., LINDBOM L. Inhibitory effect of locally administered heparin on leukocyte rolling and chemoattractant-induced firm adhesion in rat mesenteric venules in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:906–910. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]