Abstract

The pharmacological characteristics of solid-phase von Willebrand factor (svWF), a novel platelet agonist, were studied.

Washed platelet suspensions were obtained from human blood and the effects of svWF on platelets were measured using aggregometry, phase-contrast microscopy, flow cytometry and zymography.

Incubation of platelets with svWF (0.2 – 1.2 μg ml−1) resulted in their adhesion to the ligand, while co-incubations of svWF with subthreshold concentrations of ADP, collagen and thrombin resulted in aggregation.

6B4 inhibitory anti-glycoprotein (GP)Ib antibodies abolished platelet adhesion stimulated by svWF, while aggregation was reduced in the presence of 6B4 and N-Acetyl-Pen-Arg-Gly-Asp-Cys, an antagonist of GPIIb/IIIa.

Platelet adhesion stimulated with svWF was associated with a concentration-dependent increase in expression of GPIb, but not of GPIIb/IIIa.

In contrast, collagen (0.5 – 10.0 μg ml−1) caused down-regulation of GPIb and up-regulation of GPIIb/IIIa in platelets.

Solid-phase vWF (1.2 μg ml−1) resulted in the release of MMP-2 from platelets.

Inhibition of MMP-2 with phenanthroline (10 μM), but not with aspirin or apyrase, inhibited platelet adhesion stimulated with svWF.

In contrast, human recombinant MMP-2 potentiated both the effects of svWF on adhesion and up-regulation of GPIb.

Platelet adhesion and aggregation stimulated with svWF were reduced by S-nitroso-n-acetyl-penicillamine, an NO donor, and prostacyclin.

Thus, stimulation of human platelets with svWF leads to adhesion and aggregation that are mediated via activation of GPIb and GPIIb/IIIa, respectively.

Mechanisms of activation of GPIb by svWF involve the release of MMP-2, and are regulated by NO and prostacyclin.

Keywords: Platelets, adhesion, aggregation, solid-phase von Willebrand factor, glycoprotein Ib, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, matrix metalloproteinase-2, nitric oxide, prostacyclin, aspirin

Introduction

Von Willebrand factor (vWF) is the largest soluble protein found in human plasma (Zimmerman et al., 1971; Ruggeri, 1999). Von Willebrand factor is also present in the endothelial cells, megakaryocytes, platelets and subendothelial matrices. The protein exerts crucial haemostatic functions such as promoting platelet adhesion to thrombogenic surfaces, platelet-platelet cohesion during thrombus formation, as well as it serves as a carrier for factor VIII in plasma (Ruggeri, 1999; Vlot et al., 1998).

The actions of vWF are mediated via its interactions with two major platelet receptors, glycoprotein (GP) Ib and GPIIb/IIIa. GPIb is largely involved in primary platelet adhesion, while GPIIb/IIIa mediates the subsequent steps of platelet spreading and aggregation (Weiss et al., 1974; Nurden & Caen, 1974; Caen & Rosa, 1995; Ruggeri, 1999).

Abnormalities in expression and function of vWF, as well as of glycoproteins that interact with vWF contribute to the pathogenesis of hereditary bleeding disorders (Caen & Rosa, 1995) that were originally described by Glanzmann, von Willebrand and Bernard & Soulier (Glanzmann, 1918; von Willebrand, 1926; Bernard & Soulier, 1948). Moreover, the release of vWF from damaged endothelium may be a possible indicator of endothelial dysfunction and vascular disease (Lip & Blann, 1997).

Because of its large molecular size it has been difficult to study the effects of vWF on platelets using conventional methods such as aggregometry. Recently, Stewart et al. (1997) immobilized vWF on polystyrene beads generating a solid-phase preparation (svWF). They have demonstrated that svWF-induced platelet activation is more sensitive than classical agonist tests using ADP, collagen, adrenaline and arachidonic acid for detecting platelet dysfunction in patients with bleeding disorders. This novel solid-phase preparation allows studying its interactions with platelets and soluble-phase agonists such as ADP, collagen and thrombin using conventional light aggregometry.

Therefore, the objective of the present study was to obtain pharmacological characteristics of svWF in washed human platelet suspensions and its interactions with agents that stimulate or inhibit platelet activation.

Methods

Blood platelets

Blood was collected from healthy volunteers who had not taken any drugs known to affect platelet function for 2 weeks prior to the study. Platelet suspensions (2.5×1011 platelets l−1) were isolated from blood as described before (Radomski & Moncada, 1983).

Aggregometry

The interactions between svWF and platelets, as well as the effects of other agonists (thrombin, ADP and collagen) and inhibitors (anti-GPIb antibodies, GPIIb/IIIa receptor antagonist, phenanthroline, aspirin, apyrase, prostacyclin and S-nitroso-n-acetyl-penicillamine) on platelet function were studied using a Chronolog whole blood ionized calcium lumi aggregometer (Sawicki et al., 1997; 1998). Briefly, platelet samples were pre-incubated for 1 min at 37°C prior to addition of agents that modulated platelet function. In some experiments, luciferin-luciferase reagent was used to measure the release of ATP (Radomski et al., 1992). Aggregation was monitored for 9 min and analysed using Aggro-Link data reduction system (Sawicki et al., 1997; 1998).

Microscopy

The morphology of interactions between platelets and activator agents were studied using phase-contrast microscope (Nikon, Japan) equipped with camera (Jurasz et al., 2001).

Flow cytometry

To study platelet surface expression of GPIb, GPIIb/IIIa and MMP-2 a Becton Dickinson (FACSCalibur) flow cytometer equipped with a 488 nm wavelength argon laser, 525 nm and 575 nm band pass filters for the detection of fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate (FIT)- and streptavidin R-phycoerythrin (RPE)- fluorescence, and with Cell Quest software was used.

Double staining was performed using the anti-GPIIb and anti-GPIb antibodies. To minimize the presence of aggregates in analysed samples, platelets (10 μl of platelet suspension) and fluorescent-labelled antibodies (10 μl of approximately 100 ng μl−1 anti-GPIIb and GPIb antibodies) were diluted 10 fold using physiological saline. Platelets were identified by forward and side scatter signals. Compensation for overlap of the emission spectra for FIT and RPE in dual-labelled samples was performed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Ten to 20,000 platelet specific events were initially analysed by the cytometer. Non-activated and activated platelets were gated so as not to analyse platelet aggregates and microparticles. Furthermore, the gated whole platelet population was arbitrarily sub-gated based on size into large, medium, and small platelet populations (Figure 7A). The gates were then analysed for mean fluorescence. Flow cytometry of platelet MMP-2 was performed using specific anti-MMP-2 antibodies as previously described (Sawicki et al., 1998; Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999a). Briefly, platelets were resuspended in 0.1% bovine serum albumin in PBS and incubated for 30 min with 0.1% goat IgG to block non-specific binding. The samples were then incubated for 2 h with 1 μg ml−1 unlabeled rabbit polyclonal antibodies against MMP-2 (Sawicki et al., 1998). The incubate was centrifuged at 700×g for 4 min, the pellet resuspended in 0.1% (w v−1) bovine serum albumin in PBS and platelets incubated for 45 min with FITC-conjugated IgG. As a negative control rabbit IgG (1 μg ml−1) was used instead of anti-MMP-2 antibodies. Flow cytometry analysis was performed as described above.

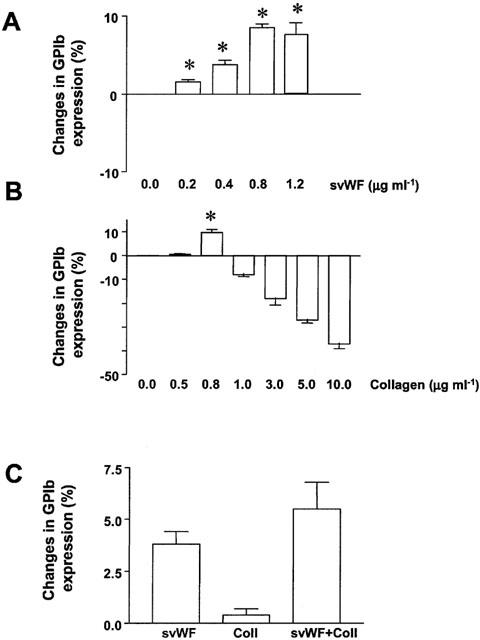

Figure 7.

Stimulation of GPIb expression by MMP-2. (A) Representative flow cytometry histogram showing the arbitrary gating of resting platelet populations labelled with anti-GPIb antibodies. (B and C) Up-regulation of GPIb expression caused by svWF in the presence of increasing concentrations of MMP-2 as analysed in medium- and small-sized platelet populations. Data are mean±s.d., n=4, *P<0.05 svWF versus MMP-2 concentrations.

Zymography

The activity of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) from platelets releasates was measured using zymography as described before (Sawicki et al., 1997; 1998, Jurasz et al., 2001).

Briefly, platelet releasates were subjected to 8% SDS – PAGE in which the separating gels were copolymerized with 2 mg ml−1 gelatin. Following electrophoresis, the gels were washed with 2.5% Triton X-100 to remove SDS and then incubated in incubation buffer (0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.05% NaN3 and 50 mM TRIS-HCl buffer, pH 7.5) for 4 days to determine the activity of the secreted enzymes. After incubation, the gels were stained with 0.05% Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 in a mixture of methanol: acetic acid: water (2.5 : 1 : 6.5) and destained in 4% methanol with 8% acetic acid. The gelatinolytic activities were detected as transparent bands against the background of Coomassie blue-stained gelatin. MMP-2 was identified by its molecular weight when compared to standards, gelatinolytic activity and the susceptibility to inhibition with the MMP inhibitor phenanthroline. Enzyme activity was assayed by densitometry analysis of gelatinolytic bands and expressed as arbitrary units mg protein−1.

Reagents

Stock suspensions of svWF in carbonate buffer were obtained from Thrombotics Inc. (Edmonton, AB, Canada). Before each experiment, vWF-coated beads were washed and suspended in physiological saline. Collagen, ADP, human thrombin and luciferin-luciferase reagent were obtained from Chronolog (Havertown, PA, U.S.A.). Bovine serum albumin, goat IgG, gelatin, Coomassie brilliant blue G-250, prostacyclin, S-nitroso-n-acetyl-penicillamine (SNAP), acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), o-phenanthroline, apyrase and N-Acetyl-Pen-Arg-Gly-Asp-Cys were all from Sigma (Oakville, ONT, Canada). These compounds were dissolved and diluted as previously described (Sawicki et al., 1997; Jurasz et al., 2001).

Antibodies

Fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated (FITC) monoclonal mouse anti-platelet GPIIb (human CD41) antibody and R-phycoerythrin conjugated (RPE) monoclonal mouse anti-platelet GPIb (human CD41) antibody were obtained from DAKO (Mississauga, ONT, Canada). Anti-MMP-2 antibodies were generated as previously described (Sawicki et al., 1998). 6B4 anti-GPIb inhibitory and 26D1 non-inhibitory antibodies were a generous gift of Prof H. Deckmyn (Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium).

Statistics

Statistics were performed using Graph Pad Software Prism 3.0 (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). All means are reported with standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and repeated measures ANOVA were performed where appropriate, and a P-value of less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Platelet adhesion and aggregation induced by svWF

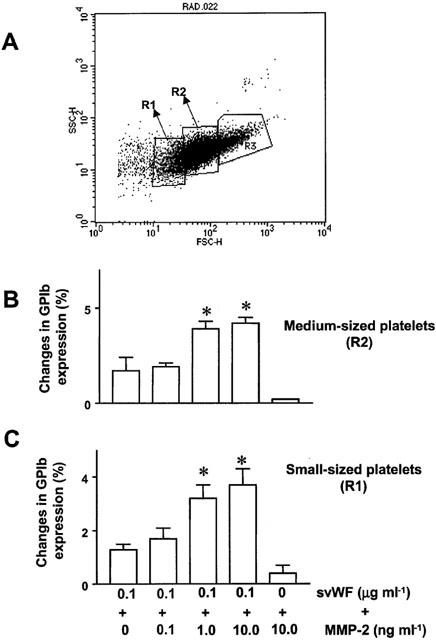

Incubation of platelets with svWF (0.2 – 3.6 μg ml−1) resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in light transmission as measured by aggregometry (Figure 1A). The maximal increase was 27±3% (n=8) at 1.2 μg ml−1. This increase was due to platelet adhesion to svWF as revealed by phase-contrast microscopy (Figure 1B). No ATP release (<0.1 μM, n=4) could be detected during svWF-induced adhesion.

Figure 1.

Stimulation of platelet activation by svWF. (A) Superimposed tracings showing a concentration-dependent increase in light transmission in response to svWF. Representative tracings of 10 similar experiments. (B) Phase-contrast microscopy demonstrating platelet adhesion to svWF (1.2 μg ml−1). (C) Potentiation of svWF-stimulated platelet activation by ADP and thrombin. Bars are mean±s.d. n=8, *P<0.05 treatments versus svWF.

The subthreshold concentrations of ADP (1 – 2 μM) and thrombin (0.01 – 0.02 u ml−1) significantly potentiated the effects of svWF on platelets and caused both aggregation (Figure 1C) and the release of ATP (0.8±0.1 μM, n=8). Similar, low concentrations of svWF (0.2 μg ml−1) potentiated collagen-induced aggregation (EC50=0.85±0.32 and 3.30±0.58 μg ml−1, mean±s.d., n=8, in the presence or absence of svWF, respectively).

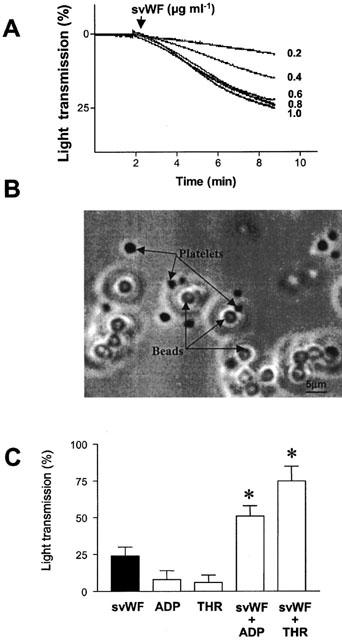

Platelet adhesion induced by svWF was decreased in a concentration-dependent manner by 6B4 anti-GPIb inhibitory (Figure 2A) but not by non-inhibitory 26D1 (n=3, data not shown) antibodies. N-Acetyl-Pen-Arg-Gly-Asp-Cys did not significantly affect (P>0.05, n=3) platelet adhesion to svWF.

Figure 2.

Pharmacological identification of receptors involved in the effects of svWF on platelet adhesion (A) and aggregation (B). (A) Inhibition of svWF (1.2 μg ml−1, CTRL)-stimulated platelet adhesion by 6B4 anti-GPIb inhibitory antibodies. (B) Inhibition of platelet activation induced by simultaneous addition of 0.6 μg ml−1 svWF and 1.0 μg ml−1 collagen (CTRL) using 6B4 antibodies, N-Acetyl-Pen-Arg-Gly-Asp-Cys, a GPIIb/IIIa antagonist (ATG, 100 μM) or EDTA (2 mM). Data are mean±s.d., n=4, *P<0.05 treatments versus CTRL.

Platelet aggregation induced by a combination of svWF (0.6 μg ml−1) and collagen (1.0 μg ml−1) was partially inhibited by 6B4 antibodies and N-Acetyl-Pen-Arg-Gly-Asp-Cys (Figure 2B). However, co-incubation of 6B4 and N-Acetyl-Pen-Arg-Gly-Asp-Cys or administration of EDTA abolished aggregation (Figure 2B).

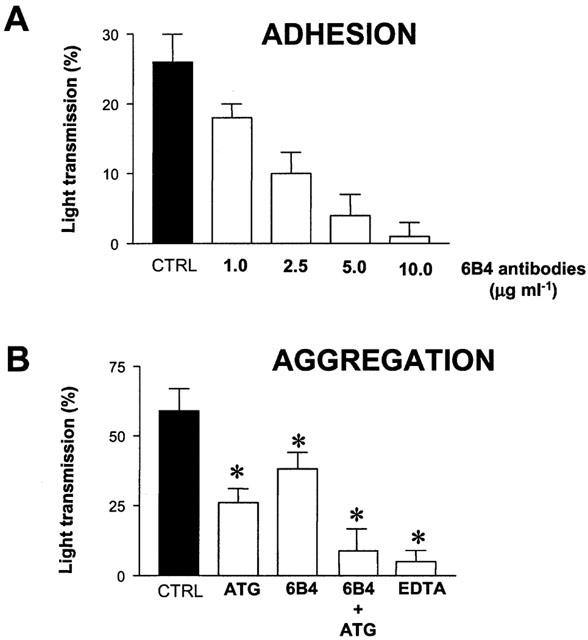

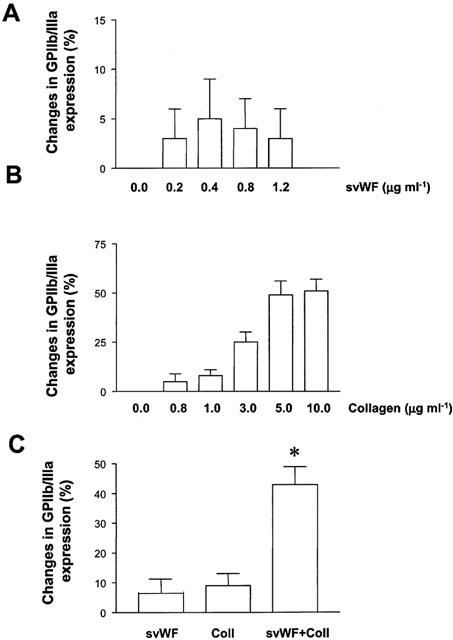

Interactions of svWF with GPIb and GPIIb/IIIa

Incubation of platelets with svWF (0.2 – 1.2 μg ml−1) resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in GPIb expression as measured by flow cytometry (Figure 3A). Platelet stimulation with collagen resulted in a biphasic expression of GPIb (Figure 3B). However, the effects of low concentrations of svWF (0.2 μg ml−1) and collagen (0.5 μg ml−1) on expression of GPIb appeared to be additive (Figure 3C). Solid-phase vWF (0.2 – 1.2 μg ml−1) did not significantly affect the expression of GPIIb/IIIa (Figure 4A). Collagen up-regulated the expression of GPIIb/IIIa in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4B). Co-incubation of collagen (1.2 μg ml−1) and svWF (1.2 μg ml−1) synergized in their effects to up-regulate GPIIb/IIIa (Figure 4C).

Figure 3.

Changes in GPIb expression induced by svWF and collagen as measured by flow cytometry. (A) Concentration-dependent up-regulation of GPIb by svWF. (B) Biphasic expression (initial up-regulation followed by down-regulation) of GPIb with collagen. (C) Co-incubation of svWF (0.2 μg ml−1) and collagen (0.5 μg ml−1, Coll) leads to enhanced expression of GPIb. Data are mean±s.d., n=4. *P<0.05 treatments versus control.

Figure 4.

Changes in GPIIb/IIIa expression induced by svWF and collagen. (A) SvWF did not significantly affect the expression of GPIIb/IIIa. (B). Up-regulation of GPIIb/IIIa expression by collagen. (C) Potentiation of collagen (1.2 μg ml−1, Coll)-induced expression of GPIIb/IIIa by svWF (1.2 μg ml−1). Data are mean±s.d., n=4, *P<0.05 Coll versus Coll+svWF.

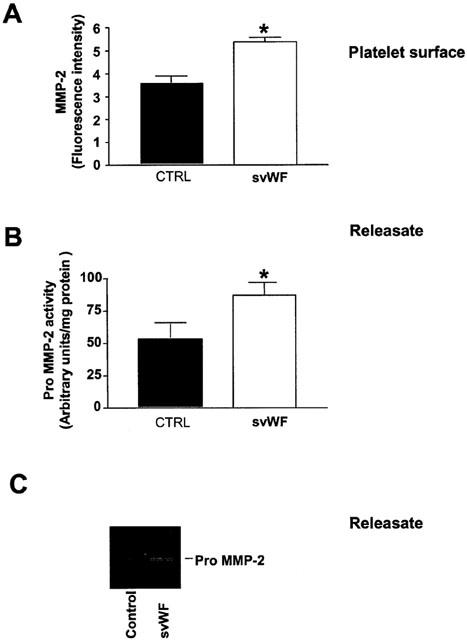

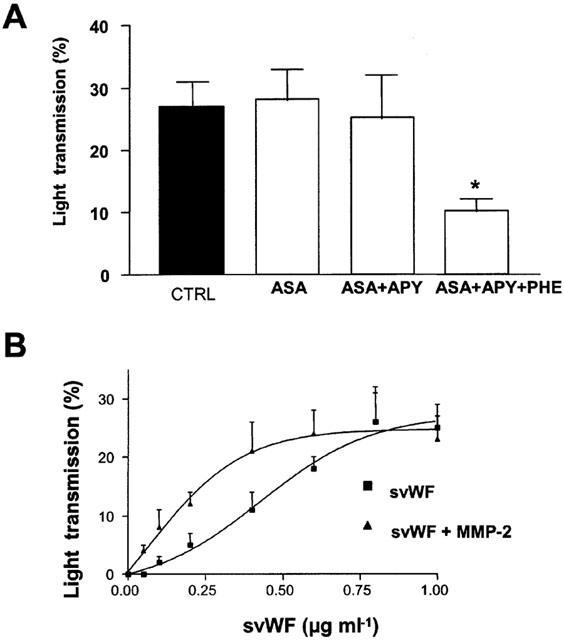

Interactions between svWF and matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2)

Platelet adhesion stimulated with svWF (0.2 – 1.2 μg ml−1) resulted in translocation of MMP-2 to the platelet surface (Figure 5A) and releasate (Figure 5B,C). This increase in adhesion was not significantly affected by the addition of aspirin and apyrase (Figure 6A). In contrast, the addition of phenathroline to aspirin- and apyrase-treated platelets significantly reduced platelet adhesion induced by svWF (Figure 6A). Finally, svWF-induced platelet adhesion was potentiated by MMP-2 (Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

Release of MMP-2 caused by svWF-mediated platelet adhesion. (A) Up-regulation of MMP-2 on platelet surface stimulated by svWF (1.2 μg ml−1) as detected by flow cytometry. (B) Enhanced release of MMP-2 into platelet releasate. (C) Inset shows a representative zymogram. CTRL-control reactions in the absence of svWF. Data are mean±s.d., n=4, *P<0.05.

Figure 6.

MMP-2 contributes to platelet adhesion stimulated by svWF. (A) Control adhesion stimulated with svWF (1.2 μg ml−1, CTRL) is not significantly affected by pre-treatment with aspirin (100 μM, ASA) and apyrase (200 μg ml−1, APY), but reduced in the presence of phenanthroline (10 μM, PHE). (B) Potentiation by MMP-2 (10 ng ml−1) of svWF-mediated platelet adhesion. Data are mean±s.d., n=4, *P<0.05 ASA+APY+PHE versus svWF.

The potentiating effects of MMP-2 were associated with increased expression of GPIb in low-, medium- (Figure 7B,C) as well as large-sized platelets (not shown).

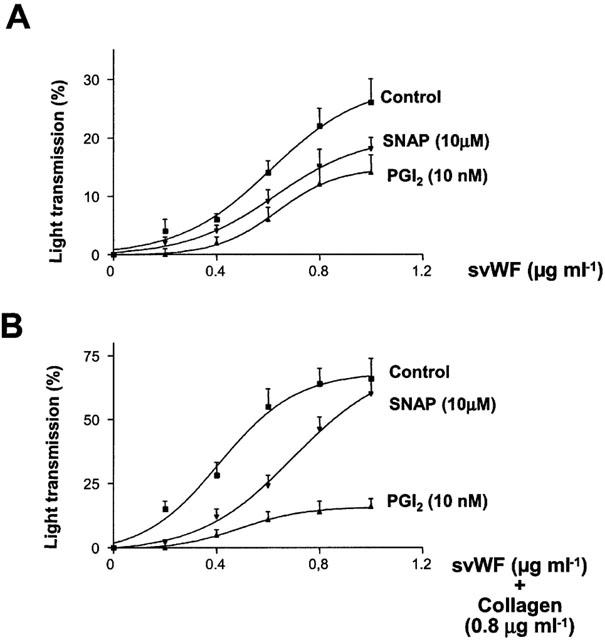

Effects of NO and prostacyclin on svWF-stimulated adhesion and aggregation

Prostacyclin and SNAP significantly reduced platelet adhesion to svWF (Figure 8A). Similar, these inhibitors reduced platelet aggregation mediated by svWF and collagen (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Inhibition of svWF-stimulated platelet adhesion (A) and aggregation (B) by SNAP and PGI2. Control curves were obtained with svWF (A) and svWF and collagen (0.8 μg ml−1, B). Data are mean±s.d., n=3.

Discussion

The physiological reactions of vWF in vivo include platelet adhesion followed by aggregation and formation of a haemostatic plug.

We have investigated the pharmacological profile of novel platelet agonist svWF in human washed platelets suspended in Tyrode's solution containing physiological levels of ions (Radomski & Moncada, 1983). Previous studies using platelet-rich plasma (PRP) showed that svWF was able to aggregate platelets in a way similar to those of soluble agonists (Stewart et al., 1997). In the current experiments, svWF caused a concentration-dependent increase in light transmission that was approximately 3 fold lower than in plasma. The microscopic examination of platelets showed that this reaction was due to platelet adhesion to svWF. Differential effects of svWF in washed platelets and PRP are likely to result from the release of platelet granules that is facilitated by low extracellular calcium levels present in the citrated PRP (Packham et al., 1987; Bretschneider et al., 1994). Co-incubations of svWF-stimulated platelets with subthreshold concentrations of ADP, collagen and thrombin resulted in the release of platelet granules and aggregation. The latter model mimics the effects of vWF in vivo as blood flow and shear stress are known to promote vWF-mediated platelet aggregation (Ruggeri, 1999).

The inhibitory anti-GPIb antibodies abolished platelet adhesion stimulated with svWF indicating the involvement of GPIb. In contrast, platelet aggregation stimulated by subthreshold concentrations of collagen and svWF is mediated via expression of both GPIb and GPIIb/IIIa, as this was abolished by anti-GPIb antibodies and GPIIb/IIIa receptor antagonist. To study further the involvement of GPIb and GPIIb/IIIa in adhesion and aggregation mediated by svWF we measured the receptor expression using flow cytometry. Platelet adhesion stimulated by svWF resulted in increased expression of GPIb. The extent of this up-regulation of GPIb was approximately 10%. This correlates well with platelet adhesion to stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells that in vitro does not exceed 10% (Radomski et al., 1987). Low, non-aggregating concentrations of collagen (0.5 and 0.8 μg ml−1) also led to up-regulation of GPIb on the platelet surface. In vivo, platelet adhesion to collagen is a two-step process. First, vWF bound to collagen engages GPIb platelet receptor, while the second step involves the interactions of collagen with GPIa/IIa platelet receptor protein (Watson, 1999; Clemetson, 1999). It is possible that in these experiments low amounts of collagen caused the release of vWF from platelets, or that up-regulation of GPIb resulted from direct interactions of collagen with platelets. Indeed, co-incubations of low concentrations of svWF and collagen were additive to up-regulate GPIb.

The measurement of GPIIb/IIIa expression in platelets during svWF-stimulated platelet adhesion showed that this process was not associated with significant changes in the receptor. This contrasted with the effects of collagen that caused strong up-regulation of GPIIb/IIIa. Moreover, collagen and svWF synergized to cause up-regulation of GPIIb/IIIa.

Thus, the data obtained from pharmacological and flow cytometry studies demonstrate for the first time that the adhesion-stimulator effects of svWF are mediated via up-regulation of GPIb receptor, while aggregation-activator effects of svWF involve also increased expression of GPIIb/IIIa. Recent studies have evidenced vWF/GPIb-dependent up-regulation of GPIIb/IIIa (Yap et al., 2000). The authors described sequential contact of platelets with immobilized vWF, transient tethering, translocation and finally firm adhesion. The agonist-mediated platelet receptor modifications (i.e. up-regulation or down-regulation) in our experiments are fundamentally different between collagen (a soluble agonist) and svWF (a solid-phase agonist). In the case of the former, the agonist can remain engaged on the platelet surface during analysis by flow cytometry. In the latter, size constraints of svWF dictate that only unbound platelets (i.e. not associated with the vWF-coated beads) be analysed. This implies that svWF-mediated up-regulation of GPIb is dependent upon transient contact of the platelet with this ligand. Therefore, our present observations of svWF-mediated platelet GPIb upregulation may provide insight into the tethering/translocation/recruitment process of activated platelets in vivo.

Recently, it was discovered that human platelets are aggregated by matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) (Sawicki et al., 1997; 1998; Kazes et al., 2000). Therefore, we investigated the involvement of MMP-2 in svWF-mediated platelet adhesion. SvWF caused translocation of MMP-2 to the platelet surface, which was similar to the effects of collagen (Sawicki et al., 1998). Moreover, svWF-mediated adhesion was inhibited only when phenanthroline, a selective inhibitor of platelet MMP-2 (Sawicki et al., 1997; 1998; Jurasz et al., 2001) was added to platelets, but not by co-incubations of aspirin (a cyclo-oxygenase blocker) and apyrase that scavenges ADP.

Furthermore, MMP-2 potentiated the adhesion-stimulator effects of svWF. Thus, it is possible that the release of MMP-2 mediated some of the effects of svWF on platelet adhesion under conditions when the release of platelet granules had not taken place, as evidenced by the lack of measurable ATP secretion. Interestingly, under resting conditions platelet MMP-2 is localized in cytoplasm without apparent association with platelet granules (Sawicki et al., 1998).

We also measured the expression of GPIb in response to a combination of svWF and MMP-2. MMP-2 potentiated up-regulation of GPIb initiated by svWF. MMP-2 is known to bind to integrins such as αvβ3 via its C-terminal haemopexin-like domain (Brooks et al., 1996; Deryugina et al., 1997). The αvβ3 may also enhance the activation of pro-MMP-2 to MMP-2 through membrane type-1 (MT1)-MMP-dependent mechanism (Deryugina et al., 2001). Thus, up-regulation of GPIb could be a consequence of the interactions between the adhesive protein domain of MMP-2 and the receptor. GPIb contains some leucine-rich domains in its structure (Clemetson & Clemetson, 1995). MMPs have affinity to Gly-Leu and Gly-lle domains (Yu et al., 1998). We have shown that MMP-2 can interact with other MMP affinity domain-containing proteins such as big-endothelin-1 (Fernandez-Patron et al., 1999) and calcitonin-gene-related peptide (Fernandez-Patron et al., 2000). Therefore, a proteolytic modification of GPIb could also increase its affinity to svWF. The affinity of svWF to GPIb could be enhanced following proteolytic modification of the ligand. VWF in vivo is subjected to proteolysis by a zinc-dependent metalloproteianse enzyme that increases vWF multimer formation, and thus regulates the haemostatic actions of this protein (Tsai, 1996; Furlan et al., 1996). In vivo, the secretion of vWF from the endothelial cells is regulated by NO and prostacyclin (Jilma et al., 1997; Pernerstorfer et al., 2000; Hegeman et al., 1998). There is evidence that these inhibitors could decrease the expression of GPIb (Michelson et al., 1990; Francesconi et al., 1996). The results of current experiments with svWF-induced adhesion and aggregation show that both inhibitors may reduce platelet activation stimulated by svWF.

While the effects of prostacyclin and NO on adhesion are modest, svWF-stimulated aggregation is more amenable to the inhibitory effects of these compounds.

In conclusion, the use of svWF in stirred washed platelet suspensions allows studying both adhesion and aggregation and the associated transduction mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof H. Deckmyn (Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium) for a generous gift of anti-GPIb antibodies. This work was supported by a grant (MOP 14074) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). P. Jurasz is supported by a studentship from the Canada Lung Association. M.W. Stewart is a CIHR scientist.

Abbreviations

- GPIb

glycoprotein Ib

- GPIIb/IIIa

glycoprotein IIb/IIIa

- MMP-2

matrix metalloproteinase-2

- SNAP

S-nitroso-n-acetyl-penicillamine

- svWF

solid-phase von Willebrand factor

References

- BERNARD J., SOULIER J.P. Sur on nouvelle variété de dystrophie thrombocytaire hémorragipare congénitale. Sem. Hop. Paris. 1948;24:3217–3223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRETSCHNEIDER E., GLUSA E., SCHROR K. ADP-, PAF- and adrenaline-induced platelet aggregation and thromboxane formation are not affected by a thromboxane receptor antagonist at physiological external Ca++ concentrations. Thromb. Res. 1994;75:233–242. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(94)90234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROOKS P.C., STROMBLAD S., SANDERS L.C., VON SCHALSCHA T.L., AIMES R.T., STETLER-STEVENSON W.G., QUIGLEY J.P., CHERESH D.A. Localization of matrix metalloproteinase MMP-2 to the surface of invasive cells by interaction with integrin alpha v beta 3. Cell. 1996;85:683–693. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAEN J.P., ROSA J.P. Platelet-vessel wall interaction: from the bedside to molecules. Thromb. Haemostas. 1995;74:18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLEMETSON K.J. Platelet collagen receptors: a new target for inhibition. Haemostasis. 1999;29:16–26. doi: 10.1159/000022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLEMETSON K.J., CLEMETSON J.M. Platelet GPIb-V-IX complex. Structure, function, physiology and pathology. Sem. Thromb. Haemost. 1995;21:130–136. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1000387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DERYUGINA E.I., LUO G.X., REISFELD R.A., BOURDON M.A., STRONGIN A. Tumor cell invasion though Matrigel is regulated by activated matrix metalloproteinase-2. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:3201–3210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DERYUGINA E.I., RATNKOV B., MONOSOV E., POSTNOVA T.I., DISCIPIO R., SMITH J.W., STRONGIN A.Y. MT1-MMP initiates activation of pro-MMP-2 and integrin αvβ3 promotes maturation of MMP-2 in breast carcinoma cells. Exp. Cell. Res. 2001;263:209–223. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERNANDEZ-PATRON C., RADOMSKI M.W., DAVIDGE S.M. Vascular matrix metalloproteinase-2 cleaves big endothelin-1 yielding a novel vasoconstrictor. Circ. Res. 1999;85:906–911. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.10.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERNANDEZ-PATRON C., STEWART K., ZHANG Y., KOIVUNEN E, , RADOMSKI M.W., DAVIDGE S. Vascular matrix metalloproteinase-2-dependent cleavage of calcitonin-gene related peptide promotes vasoconstriction. Circ. Res. 2000;87:670–676. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANCESCONI M., CASONATO A., PAGAN S., DONELLA-DEANA A., PONTARA E., GIROLAMI A., DEANA R. Inhibitory effect of prostacyclin and nitroprusside on type IIB von Willebrand factor-promoted platelet activation. Thromb. Haemost. 1996;76:469–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FURLAN M., ROBLES R., LAMIE B. Partial purification and characterization of a protease from human plasma cleaving von Willebrand factor to fragments produced by in vivo proteolysis. Blood. 1996;87:4223–4234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLANZMANN E. Hereditäre hämorragische Thrombasthenie. Ein Beitrag zur Pathologie der Blutplättchen. Jahr. Kinderh. 1918;88:113–141. [Google Scholar]

- HEGEMAN R.J., VAN DEN EIJNDEN-SCHRAUWEN Y., EMEIS J.J. Adenosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate induces regulated secretion of tissue-type plasminogen activator and von Willebrand factor from cultured human endothelial cells. Thromb. Haemost. 1998;79:853–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JILMA B., DIRNBERGER E., EICHLER H-G., MATULLA B., SCHMETTERER L., KAPIOTIS S., SPEISER W., WAGNER O.F. Partial blockade of nitric oxide synthase blunts the exercise-induced increase of von Willebrand factor antigen and of factor VIII in man. Thromb. Haemost. 1997;78:1268–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JURASZ P., SAWICKI G., DUSZYK M., SAWICKA J., MIRANDA C., MAYERS I., RADOMSKI M.W. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 in tumour-cell induced platelet aggregation: Regulation by NO. Cancer Res. 2001;61:376–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAZES I, , ELALAMY I., SRAER J.D., HATMI M., NGUYEN G. Platelet release of trimolecular complex components MT-1-mmo/TIMP2/MMP2: involvement in MMP-2 activation and platelet aggregation. Blood. 2000;96:3064–3069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIP G.Y.H., BLANN A. Von Willebrand factor: a marker of endothelial dysfunction in vascular disorders. Cardiovasc. Res. 1997;34:255–265. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICHELSON A.D., BENOIT S.E., FURMAN M.I., BRECKWOLDT W.L., ROHRER M.J., BARNARD M.R., LOSCALZO J. Effects of nitric oxide/EDRF on platelet surface glycoproteins. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;270:H1640–H1648. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.5.H1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NURDEN A.T., CAEN J.P. An abnormal glycoprotein pattern in 3 cases of Glanzmann thrombasthenia. Br. J. Haematol. 1974;28:253–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1974.tb06660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PACKHAM M.A, , KINLOUGH-RATHBONE R.E., MUSTARD J.F. Thromboxane A2 causes feedback amplification involving extensive thromboxane A2 formation on close contact of human platelets in media with a low concentration of ionized calcium. Blood. 1987;70:647–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERNERSTORFER T., STOHLAWETZ P., KAPIOTIS S., EICHLER H.-G., JILMA B. Partial inhibition of nitric oxide synthase primes the stimulated pathway of vWF-secretion in man. Atherosclerosis. 2000;148:43–47. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., MONCADA S. An improved method for washing of human platelets with prostacyclin. Thromb. Res. 1983;30:383–389. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(83)90230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., PALMER R.M.J., MONCADA S. Endogenous nitric oxide inhibits human platelet adhesion to vascular endothelium. The Lancet. 1987;ii:1057–1058. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., REES D.D., DUTRA A., MONCADA S. S-Nitroso-glutathione inhibits platelet activation in vitro and in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;107:745–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUGGERI Z.M. Structure and function of von Willebrand factor. Thromb. Haemostas. 1999;82:276–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAWICKI G., SALAS E., MURAT J., MISZTA-LANE H., RADOMSKI M.W. Release of gelatinase A from human platelets mediates aggregation. Nature. 1997;386:616–619. doi: 10.1038/386616a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAWICKI G., SANDERS E.S., SALAS E., WOZNIAK M., RODRIGO J., RADOMSKI M.W. Localization and translocation of MMP-2 during aggregation of human platelets. Thromb. Haemostas. 1998;80:836–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEWART M.W., ETCHES W.S., BOSHKOV L.K., MANT M.J., GORDON P.J., SHAW A.R.E. Platelet activation by a novel solid-phase agonist: effects of vWF immobilized on polysterene beads. Br. J. Haematol. 1997;97:321–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.372681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSAI H.M. Physiologic cleavage of von Willebrand factor by a plasma protease is dependent on its conformation and requires calcium ion. Blood. 1996;87:4325–4244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON WILLEBRAND E.A. Hereditär pseudohemofili. Finska Läkaresällskapets Handlingar. 1926;68:87–112. [Google Scholar]

- VLOT A.J., KOPPELMAN S.J., BAUMA B.N., SIXMA J.J. Factor VIII and von Willebrand factor. Thromb. Haemost. 1998;79:456–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATSON S.B. Collagen receptor signaling in platelets and megakaryocytes. Thromb. Haemost. 1999;82:365–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEISS H.J., TSCHOPP T.B., BAUMGARTNER H.R., SUSSMAN I., JOHNSON M.M., EGAN J.J. Decreased adhesion of giant (Bernard Soulier) platelets to subendothelium: further implications on the role of the von Willebrand factor in hemostasis. Am. J. Med. 1974;57:920–925. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAP C.L., HUGHAN S.C., CRANMER S.L., NESBITT W.S., ROONEY M.M., GIULIANO S., KULKARNI S., DOPHEIDE S.M., YUAN Y., SALEM H.H., JACKSON S.P. Synergistic adhesive interactions and signalling mechanisms operating between platelet glycoprotein Ib/IX and integrin alpha IIbbeta 3. Studies in human platelets and transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:41377–41388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YU A.E., MURPHY A.N., STETLER-STEVENSON W.G.72-kDa gelatinase (gelatinase A): structure, activation, regulation and substrate specificity Matrix Metalloproteinases 1998San Diego: Academic Press; 85–113.ed. Parks, W.C., Mecham, R.P. pp [Google Scholar]

- ZIMMERMAN T.S., RATNOFF O.D., POWELL A.E. Immunologic differentiation of classic hemphilia (Factor VIII deficiency) and von Willebrand's disease. With observation on combined deficiencies of antihemophilic factor and proaccelerin (Factor V) and on an acquired circulating anticoagulant against antihemophilic factor. J. Clin. Invest. 1971;50:244–254. doi: 10.1172/JCI106480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]