Abstract

Adenosine kinase (AK) inhibitors can enhance adenosine levels and potentiate adenosine receptor activation. As the AK inhibitors 5′ iodotubercidin (ITU) and 5-amino-5′-deoxyadenosine (NH2dAdo) are nucleoside analogues, we hypothesized that nucleoside transporter subtype expression can affect the potency of these inhibitors in intact cells.

Three nucleoside transporter subtypes that mediate adenosine permeation of rat cells have been characterized and cloned: equilibrative transporters rENT1 and rENT2 and concentrative transporter rCNT2. We stably transfected rat C6 glioma cells, which express rENT2 nucleoside transporters, with rENT1 (rENT1-C6 cells) or rCNT2 (rCNT2-C6 cells) nucleoside transporters.

We tested the effects of ITU and NH2dAdo on [3H]-adenosine uptake and conversion to [3H]-adenine nucleotides in the three cell types. NH2dAdo did not show any cell type selectivity. In contrast, ITU showed significant inhibition of [3H]-adenosine uptake and [3H]-adenine nucleotide formation at concentrations ⩽100 nM in rENT1-C6 cells, while concentrations ⩾3 μM were required for C6 or rCNT2-C6 cells.

Nitrobenzylthioinosine (NBMPR; 100 nM), a selective inhibitor of rENT1, abolished the effects of nanomolar concentrations of ITU in rENT1-C6 cells.

This study demonstrates that the effects of ITU, but not NH2dAdo, in whole cell assays are dependent upon nucleoside transporter subtype expression. Thus, cellular and tissue differences in expression of nucleoside transporter subtypes may affect the pharmacological actions of some AK inhibitors.

Keywords: Nucleoside transport; ENT1; ENT2; CNT2; nitrobenzylthioinosine; adenosine kinase; 5-iodotubercidin, 5-amino-5′-deoxyadenosine, C6 glioma cells

Introduction

Adenosine kinase (AK) inhibitors have been reported to have therapeutic potential in the areas of inflammation, analgesia, epilepsy and cerebral ischaemia (Kowaluk et al., 1998). These properties are believed to be due to inhibition of adenosine metabolism, followed by elevation of endogenous adenosine levels and activation of adenosine receptors (Britton et al., 1999). As AK is an intracellular enzyme, only cell permeable inhibitors will exhibit pharmacological effects. Many AK inhibitors are purine nucleoside analogues (Henderson et al., 1972; Miller et al., 1979), so we hypothesized that the cellular permeability of these compounds may require nucleoside transporters.

Transmembrane fluxes of purine and pyrimidine nucleosides, including adenosine, occur via nucleoside transporters. These transporters are broadly categorized into two classes: concentrative and equilibrative. Concentrative nucleoside transporters, of which six subtypes have been characterized, are Na+-dependent and couple influx of adenosine or other nucleosides to influx of Na+ (Cass et al., 1998; Geiger et al., 1997). Three concentrative nucleoside transporters have been cloned from human and rodent tissues (Che et al., 1995; Huang et al., 1994; Ritzel et al., 2001): CNT1 (concentrative nucleoside transporter 1) is selective for pyrimidine permeants, CNT2 is selective for purine nucleosides and uridine, and CNT3 has purine and pyrimidine nucleosides as permeants. Two equilibrative nucleoside transporter subtypes have been characterized and cloned (Crawford et al., 1998; Griffiths et al., 1997a,1997b; Yao et al., 1997). Both transport purine and pyrimidine nucleosides across plasma membranes in a direction dictated by their concentration gradients. The equilibrative transporters are two unique gene products and are functionally differentiated based on their sensitivity to nitrobenzylthioinosine (NBMPR). ENT1 (equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1) is inhibited by low nanomolar concentrations of NBMPR while ENT2 is relatively insensitive to NBMPR, with Ki values >1 μM (Griffith & Jarvis, 1996).

Intracellular metabolism of adenosine by AK promotes an inwardly directed concentration gradient and results in metabolic trapping of adenosine in the form of adenine nucleotides. AK inhibitors, such as 5-iodotubercidin (ITU) and 5′-amino-5′-deoxyadenosine (NH2dAdo) can reduce intracellular adenosine metabolism and, thus, inhibit the cellular uptake of adenosine. However, the mechanism by which AK inhibitors permeate cells has not been established. We hypothesized that these nucleoside analogues enter cells via nucleoside transporters. We have previously reported that ITU, at concentrations of 4 – 15 μM, can inhibit both ENT1 nucleoside transport and ligand binding to ENT1 (Parkinson & Geiger, 1996).

The objectives of this study were to determine if the expression of nucleoside transporter subtypes affects the potency of the AK inhibitors ITU or NH2dAdo to inhibit adenosine transport and metabolism in rat C6 glioma cells. Our results indicate that inhibition by ITU, but not NH2dAdo, was facilitated by expression of rENT1 transporters.

Methods

Materials

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers, low and high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), foetal bovine serum (FBS), Moloney murine leukaemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase, oligo (dT)12 – 18, random primers DNA labelling kits, LIPOFECTIN® reagent, neomycin (G418), EcoRV, NotI and SacII were purchased from Life Technologies (Burlington, Ontario, Canada). The SNAP RNA isolation kit and pcDNA 3.1(−) mammalian expression vector were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.). T4 DNA polymerase, T4 DNA ligase and Wizard® DNA clean-up system were purchased from Promega. Ready To Go™ PCR beads and ApaI were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A.). Epicurian Coli® XL1-Blue MRF' Kan supercompetent cells were purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.). [3H]-adenosine, [3H]-uridine and [3H]-NBMPR were purchased from NEN Life Sciences (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Iodotubericidin (ITU) was purchased from Alberta Nucleoside Therapeutics (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada). Erythro-9-(2-hydroxy-3-nonyl)adenine hydrochloride (EHNA), dipyridamole (DPR), NBMPR and nitrobenzylthioguanosine were purchased from Research Biochemicals International (Natlick, MA, U.S.A.). All other compounds were purchased from the Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.).

Transfection of C6 Glioma Cells with rENT1, rCNT2 or vector

The nucleoside transporter subtypes rENT1 and rCNT2 were originally cloned in pGEM-T vectors (Griffiths et al., 1997a; Yao et al., 1996). The rENT1 cDNA insert was excised from the pGEM-T vector using SacII and NotI (simultaneously at 37°C for 1 h) and then treated with T4 DNA polymerase to produce blunt ends. The rENT1 insert was ligated into the EcoRV restriction site of pcDNA 3.1(−). The rCNT2 was excised with ApaI and NotI (simultaneously at 37°C for 1 h) and then inserted into the ApaI and NotI sites in pcDNA 3.1(−). pcDNA 3.1(−) with and without inserts was amplified in Epicurian Coli® XL1-Blue MRF' Kan supercompetent cells, isolated and purified using Wizard® DNA clean-up system.

Rat C6 glioma cells were transfected with pcDNA 3.1(−) containing no insert, rENT1 or rCNT2 using LIPOFECTIN® reagent and the manufacturer's protocol. Stably transfected C6 cells were selected using 800 μg G418 ml of culture media. Single clones were isolated and cultured in the presence of 400 μg ml−1 G418.

RT – PCR analysis

RT – PCR analysis was performed as previously described (Sinclair et al., 2000a). Total RNA was isolated from rat C6 glioma cells using the SNAP RNA isolation kit and treated with DNaseI. cDNA synthesis was performed at 37°C for 60 min with a total reaction volume of 60 μl consisting of 300 ng oligo(dT)12 – 18 primer, 5 μg total RNA, 3 mM dNTPs, 6.7 μM dithiothreitol (DTT), 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2 and 3.3 Units MMLV reverse transcriptase. Control reactions were performed by omitting reverse transcriptase.

For PCR, control and reverse transcriptase-treated solutions (2 μl) were amplified using Ready To Go™ PCR beads. The amplification consisted of 30 cycles of: 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 56°C and 1 min at 72°C. A final 10 min 72°C elongation step followed and samples were held at −9°C then analysed by electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel. DNA bands were viewed and photographed under u.v. light following ethidium bromide staining.

rENT1 was amplified with the 5′ primer 5′-CACCATGACAACCAGTCACCAG-3′ and the 3′ primer 5′-TGAAGGCACCTGGTTTCTGTC-3′ to produce a 1.76-kb product. rENT2 was amplified using the 5′ primer 5′-TTACCCAACCTGCACCCTCTC-3′ and the 3′ primer 5′-GTAGCCACATTGCATATGGTGA-3′ to produce a 1.67-kb product. rCNT2 was amplified using the 5′ primer 5′-AACCTCCACTTCCTGCTTGTCA-3′ and the 3′ primer 5′-CTTCACTCCCTCCTTGCTCTTG-3′ to produce a 1.43-kb product. The presence of mRNA for glyceraldehyde-3′-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), a ubiquitous housekeeping gene, was used as a loading control, and was detected using the 5′ primer 5′-GCTGGGGCTCACCTGAAGGG-3′ and the 3′ primer 5′-GGATGACCTTGCCCACAGCC-3′ to amplify a 343-bp DNA product (bases 346 to 688) from the rat GAPDH cDNA.

Nucleoside uptake assays

Rat C6 glioma cells were cultured in 24-well plates until confluent as previously described (Sinclair et al., 2000a). Cells were washed twice in Na+ buffer (in mM): NaCl 118, HEPES 25, KCl 4.9, K2HPO4 1.4, MgCl2 1.2, CaCl2 1, glucose 11, to pH 7.4 with NaOH or NMG+ buffer in which NaCl was replaced with N-methylglucamine (NMG) and pH was adjusted to 7.4 with HCl. Cells were incubated with [3H]-adenosine (1 μM) or [3H]-uridine (1 μM) in 250 μl of Na+ or NMG+ buffer for times ranging from 0 – 300 s. Nucleoside transporter subtypes were determined by inhibition of [3H]-uridine uptake with NBMPR, DPR or NMG+ buffer. At 100 nM, NBMPR inhibits transport (⩾95%) through ENT1 but not other nucleoside transporters. At 10 μM, DPR inhibits transport (⩾95%) through both equilibrative (ENT1 and ENT2) transporters but not concentrative transporters. NMG+ buffer inhibits Na+-dependent concentrative transporters but not ENT1 or ENT2. The inhibition of total [3H]-uridine uptake caused by NBMPR, DPR or NMG+ was used as an indicator of the proportion of uptake mediated by the respective transporters.

To examine the effect of AK inhibitors, cells were exposed to graded concentrations of ITU (1 nM – 30 μM) or NH2dAdo (300 nM – 30 μM) 15 min prior to and during the uptake assays. To terminate uptake, the extracellular solutions were aspirated and the cells were rapidly washed twice with ice-cold buffer. Cellular protein was dissolved by incubating cells in sealed containers with NaOH (1 M; 500 μl) at 37°C for 16 h. Separate aliquots of the dissolved cells were used for protein determination, using the Bradford assay, and for liquid scintillation spectroscopy. Uptake values were determined from the radioactivity in the dissolved cells and are expressed as pmol mg−1 cellular protein using the specific activity of the uptake assay buffer.

Adenosine kinase assays

Activity of isolated AK was assessed as previously described (Sinclair et al., 2000b). Briefly, cells were homogenized in ice-cold 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), then centrifuged at 38,000×g (1 h, 4°C). Supernatants were retained as cytosolic protein. Assay reaction mixtures (100 μl) contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.1% (w v−1) bovine serum albumin, 500 nM EHNA, 50% (v v−1) glycerol, 1.6 mM MgCl2, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 50 mM KCl, 1.2 mM ATP, 2 μM (0.25 μCi) [3H]-adenosine and 2 μg of cytosolic protein in the presence or absence of ITU (1 nM – 1 μM) or NH2dAdo (1 nM – 10 μM). Reactions were initiated by addition of cytosolic protein and, after incubation at 37°C for 5 min, reactions were terminated by heating to 90°C. Reaction products (20 μl) were spotted, in triplicate, on DE81 ion exchange filters, dried, and washed sequentially with 1 mM NH4COOH (2×5 ml), distilled deionized water (2×5 ml) and 100% ethanol (2×5 ml). HCl (0.25 ml, 0.2 M) and KCl (0.25 ml, 0.8 M) were then added to the filters to elute [3H]-adenine nucleotides, and the tritium content was determined by scintillation spectroscopy.

Inhibition of AK activity in intact cells was investigated in C6 cells as previously described, with minor modifications (Rosenberg et al., 2000; Wiesner et al., 1999). Cells were cultured and treated as described for nucleoside uptake assays. Following a 5 min [3H]-adenosine (1 μM) uptake interval, cells were washed with ice-cold buffer and dissolved in 250 μl of 2% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). One hundred μl of the cell extract was taken for scintillation spectroscopy and 50 μl was placed onto DE-81 sephadex filters to determine the percentage of the total uptake that was [3H]-adenine nucleotides. The ion-exchange filters were then washed as described above.

[3H]-NBMPR binding assays

Cells were washed with Na+ buffer then incubated (22 °C) with 0.1 – 5 nM [3H]-NBMPR in the absence or presence of 1 μM nitrobenzylthioguanosine. After a 1 h incubation interval, cells were washed twice with ice-cold Na+ buffer then dissolved with NaOH. Samples were analysed for both tritium and protein content.

Data analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times in duplicate or triplicate, unless otherwise stated. All values are expressed as means±s.e.mean and statistical significance was determined by ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Statistical analyses were performed using the software package GraphPad PRISM Version 3.0.

Results

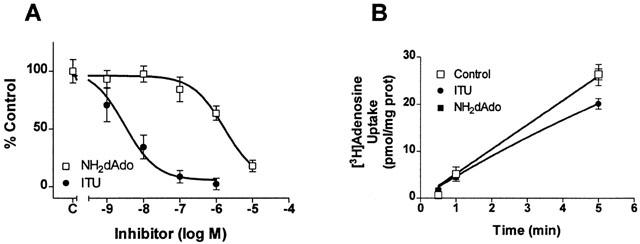

AK assays were performed to determine the potencies of ITU and NH2dAdo for inhibition of rat C6 glioma cell AK activity (Figure 1A). ITU inhibited AK by 98% at 1 μM and had an IC50 value of 4 nM. NH2dAdo produced 82% inhibition at 10 μM and had an IC50 value of 1.8 μM. Rat C6 glioma cells contain predominantly (>95%) rENT2-mediated nucleoside transport and 1 μM [3H]-adenosine uptake is linear over time (Figure 1B) (Sinclair et al., 2000a). In the absence of intracellular metabolism, [3H]-nucleoside uptake is hyperbolic over time (Sinclair et al., 2000a), thus, the apparent linearity of [3H]-adenosine uptake indicates extensive metabolism within C6 cells. Indeed, after 5 min uptake intervals, approximately 90% of intracellular tritium was associated with adenine nucleotides. Thus, we investigated maximally inhibitory concentrations of ITU (1 μM) and NH2dAdo (10 μM) on [3H]-adenosine uptake. Neither ITU nor NH2dAdo had a significant effect on 1 μM [3H]-adenosine accumulation over 5 min (Figure 1B). These results indicate that ITU and NH2dAdo are ineffective in live C6 cells and led us to hypothesize that nucleoside transporter subtype expression can affect cell permeability and, thus, efficacy of AK inhibitors.

Figure 1.

Effect of ITU or NH2dAdo on AK activity or 1 μM [3H]-adenosine uptake in C6 cells. (A) Cytosolic protein from C6 cells was isolated and AK activity was determined in the presence of ITU (1 nM – 1 μM) or NH2dAdo (1 nM – 10 μM). Data are expressed as per cent control where control represents 28.7±5.5 pmol adenine nucleotides 2 μg−1 cytosolic protein 5 min−1. (B) C6 cells were preincubated with buffer (Control), 1 μM ITU or 10 μM NH2dAdo then incubated with 1 μM [3H]-adenosine for 30 – 300 s in the presence of buffer (Control), 1 μM ITU or 10 μM NH2dAdo. Note that the symbols for the controls obscure some of the other symbols. Accumulation is expressed as pmol mg−1 cellular protein. Symbols represent means and error bars represent s.e.mean. Experiments were performed at least two times in triplicate.

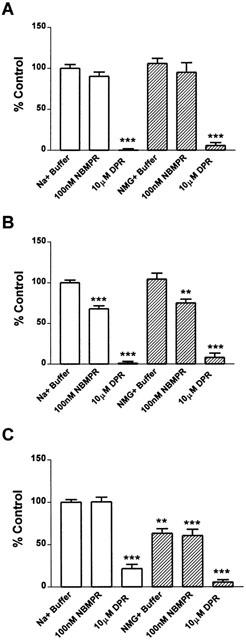

To investigate this hypothesis, we stably transfected the C6 glioma cells with pcDNA 3.1(−) containing no insert (vector-C6), rENT1 cDNA sequence (rENT1-C6) or rCNT2 cDNA sequence (rCNT2-C6). To demonstrate effective transfection, we performed 1 μM [3H]-uridine uptake, RT – PCR analysis and [3H]-NBMPR binding. The accumulation of [3H]-uridine in rENT1-C6 and rCNT2-C6 cells was increased by 45±17% and 47±20%, respectively, compared to wt-C6 cells. The absolute values of [3H]-uridine uptake obtained in the three cell types varied among experiments. The uptake of 1 μM [3H]-uridine uptake in wt-C6 (Figure 2A) or vector-C6 cells (data not shown) was not significantly affected by 100 nM NBMPR or NMG+ buffer while 10 μM DPR inhibited [3H]-uridine uptake by 100±5%. As we have previously reported (Sinclair et al., 2000a), this indicates predominantly rENT2-mediated nucleoside transport in rat C6 glioma cells. In the rENT1-C6 cells, 100 nM NBMPR inhibited [3H]-uridine uptake by 32±10%, indicating that this proportion of uptake was mediated by rENT1 and the remainder by rENT2. RT – PCR analysis indicated mRNA transcript for rENT1 in the ENT1-C6 cells but not in wt-C6, vector-transfected or rCNT2-transfected C6 cells (data not shown). In addition, specific [3H]-NBMPR binding was detected in rENT1-C6 cells (KD=0.18±0.03 nM and BMAX=298±10 fmol mg−1 protein, n=4) but not in wt-C6 cells (n=4). These data indicate successful transfection of rENT1 into these cells. Although rCNT2 is a purine selective nucleoside transporter, uridine is transported by rCNT2 (Ritzel et al., 1998). In the rCNT2-C6 cells, [3H]-uridine uptake was inhibited by 37±11% when NMG+ buffer replaced Na+ buffer (Figure 2C); this indicates that rCNT2 and rENT2 mediated approximately 37 and 63% of total uptake, respectively. RT – PCR (data not shown) demonstrated that rCNT2 mRNA transcript is present in rCNT2-C6 cells but not in wt-C6, vector-transfected or rENT1-transfected C6 cells. These data indicate successful transfection of C6 cells with the rCNT2 nucleoside transporter.

Figure 2.

Determination of nucleoside transporter subtypes in wt-C6, rENT1-C6, rCNT2-C6 and vector-C6 rat glioma cells by inhibition of nucleoside accumulation. [3H]-Uridine accumulation was measured by incubating the wt-C6 (A), rENT1-C6 (B) or rCNT2-C6 (C) with 1 μM [3H]-uridine in Na+ (open bars) or NMG+ (shaded bars) buffer in the presence or absence of 100 nM NBMPR or 10 μM DPR for 5 min. Data are expressed as per cent control where control is 4.0±0.7, 5.3±0.8 and 5.0±1.2 pmol [3H]-uridine/mg prot/ 5 min in A, B and C, respectively. Symbols represent means and error bars represent s.e.mean. Experiments were performed at least three times in duplicate.

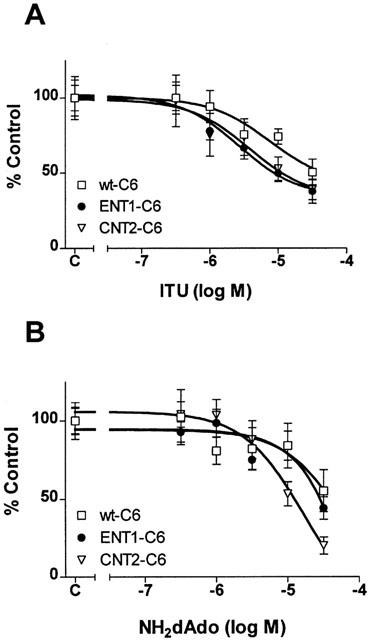

The interaction of ITU or NH2dAdo with the nucleoside transporters was investigated in the C6 cells in two ways: 1 μM [3H]-uridine uptake to investigate transporter-mediated effects and 1 μM [3H]-adenosine uptake to investigate AK-mediated and transporter-mediated effects. Previous reports have demonstrated direct interaction of ITU with nucleoside transporters at concentrations greater than 1 μM (Davies & Cook, 1995; Henderson et al., 1972; Parkinson & Geiger, 1996; Wu et al., 1984). To investigate the hypothesis that ITU and NH2dAdo inhibit nucleoside transport directly, we measured uptake of 1 μM [3H]-uridine into wt-C6, rENT1-C6 and rCNT2-C6 cells. ITU inhibited [3H]-uridine uptake with an apparent IC50 value of 2.7 – 5.6 μM, with no statistically significant differences among the three cell types (Figure 3A). NH2dAdo had similar effects on [3H]-uridine uptake to ITU; IC50 values of ⩾10 μM were obtained (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effect of ITU or NH2dAdo on [3H]-uridine uptake in wt-C6, rENT1-C6 and rCNT2-C6 cells. [3H]-Uridine accumulation was measured by incubating the wt-C6, rENT1-C6 or rCNT2-C6 with 1 μM [3H]-uridine for 5 min in the presence of ITU (1 nM – 30 μM) (A) or NH2dAdo (300 nM – 30 μM) (B). Data are expressed as per cent control. Control represents 5.5±0.9 (wt-C6), 9±2.2 (rENT1-C6) or 7.1±1.8 (rCNT2-C6) pmol [3H]-uridine/mg cellular protein 5 min−1 in (A) or 4.2±0.7 (wt-C6), 4.9±1.0 (rENT1-C6) or 8.2±1.5 (rCNT2-C6) pmol [3H]-uridine mg−1 cellular protein 5 min−1 in (B). Symbols represent means and error bars represent s.e.mean. Experiments were performed at least three times in duplicate.

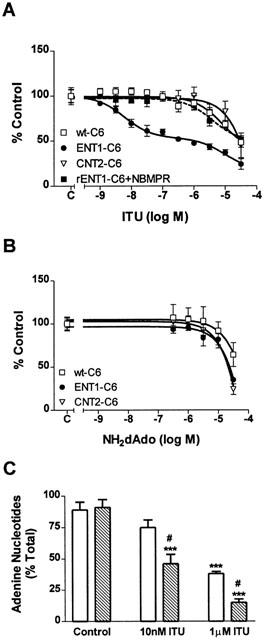

[3H]-Adenosine uptake was performed using relatively long assays, 5 min, because AK activity accounts for most of the intracellular accumulation that occurs during this time period. In wt-C6 and rCNT2-C6 cells, inhibition of [3H]-adenosine uptake by ITU was evident only with concentrations ⩾3 μM and only 50 – 55% inhibition was detected with 30 μM (Figure 4A). However, in rENT1-C6 cells, ITU produced biphasic inhibition of [3H]-adenosine uptake. The first component was observed with ITU at concentrations of 1 – 300 nM and produced 50% inhibition of [3H]-adenosine uptake with an IC50 value of 4.6 nM (Figure 4A). This IC50 value is very close to that obtained for inhibition of isolated AK by ITU (Figure 1A). At concentrations greater than 300 nM ITU, [3H]-adenosine uptake was decreased further, with a maximum of 76% inhibition observed with 30 μM (Figure 4A). Pre-treatment (5 min) of ENT1-C6 cells with NBMPR (100 nM), completely blocked the effects of nanomolar concentrations of ITU (Figure 4A) indicating that rENT1 was responsible for these effects.

Figure 4.

Effect of ITU or NH2dAdo on [3H]-adenosine uptake in wt-C6, rENT1-C6 and rCNT2-C6 cells. (A) [3H]-Adenosine accumulation was measured by incubating wt-C6, rENT1-C6 or rCNT2-C6 cells, or rENT1-C6 cells preincubated with 100 nM NBMPR (dashed line), with 1 μM [3H]-adenosine for 5 min in the presence of ITU (1 nM – 30 μM). (B) [3H]-Adenosine accumulation was measured by incubating wt-C6, rENT1-C6 or rCNT2-C6 with 1 μM [3H]-adenosine for 5 min in the presence of NH2dAdo (300 nM – 30 μM). (C) Incorporation of [3H]-adenosine into [3H]-adenine nucleotides was measured using whole cell AK assays in wt-C6 (open bars) and rENT1-C6 (hatched bars) cells in the presence of buffer, 10 nM ITU or 1 μM ITU. Data are expressed as per cent control (A and B) or per cent total (C). For wt-C6, rENT1-C6 or rCNT2-C6 cells, control represents 29±9, 37±5 (18±5 in the presence of 100 nM NBMPR) or 44±6 pmol [3H]-adenosine mg−1 cellular protein 5 min−1, respectively, in (A) or 30±8, 35±7 or 56±6 pmol [3H]-adenosine mg−1 cellular protein 5 min−1, respectively, in (B). In (C) total represents 115±14 (wt-C6) or 139±26 (rENT1-C6) pmol mg−1 cellular protein 5 min−1. Symbols represent means and error bars represent s.e.mean. Experiments were performed at least three times in duplicate. Statistical significance was determined between experimental groups by ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test (***P<0.001 from control; #P<0.05 from wt-C6 cell at the same concentration).

The inhibition of [3H]-adenosine uptake by NH2dAdo was similar in all three cell types (Figure 4B). At 30 μM NH2dAdo, [3H]-adenosine uptake was inhibited by 40 – 60%.

Whole cell adenosine kinase assays were performed to demonstrate that inhibition of [3H]-adenosine uptake by ITU or NH2dAdo correlated to decreased [3H]-adenine nucleotide incorporation. In wt-C6 and ENT1-C6 cells, approximately 90% of [3H]-adenosine accumulated by cells was metabolized to [3H]-adenine nucleotide (Figure 4C). 10 nM ITU significantly decreased the adenine nucleotide incorporation in ENT1-C6 cells but not wt-C6 cells. 1 μM ITU significantly decreased [3H]-adenine nucleotide formation in both the wt-C6 and ENT1-C6 cells but a significantly greater inhibition was seen in the ENT1-C6 cells. No inhibition of adenine nucleotide incorporation was seen with NH2dAdo at concentrations <30 μM (data not shown). This demonstrates that inhibition of [3H]-adenosine uptake correlated to decreased incorporation into [3H]-adenine nucleotides.

Discussion

AK inhibitors, by blocking adenosine phosphorylation to AMP, can elevate adenosine levels and potentiate adenosine receptor activation (Kowaluk & Jarvis, 2000; Kowaluk et al., 1998). In this report, we demonstrated that expression of the nucleoside transporter rENT1 increased ITU-mediated inhibition of [3H]-adenosine uptake compared to cells expressing rENT2 or rCNT2 nucleoside transporters. In contrast, NH2dAdo had similar potency for inhibition of [3H]-adenosine uptake in rat C6 glioma cells expressing different subtypes of nucleoside transporters. This study demonstrates that the effects of ITU, and potentially other AK inhibitors, are influenced by nucleoside transporter subtype expression.

Adenosine uptake is the result of transport across the plasma membrane followed by intracellular metabolism. Under physiological conditions, adenosine metabolism is primarily to AMP by AK, which has an affinity of 0.2 – 2.0 μM for adenosine (Geiger et al., 1997). Adenosine transport per se can be measured with rapid [3H]-adenosine uptake intervals (<15 s), while longer uptake intervals usually result in intracellular metabolic trapping of adenosine in the form of adenine nucleotides. AK inhibitors, when used during longer accumulation intervals, decrease cellular accumulation of [3H]-adenosine by decreasing its metabolism to [3H]-adenine nucleotides (Parkinson & Geiger, 1996). Surprisingly, neither ITU nor NH2dAdo inhibited the uptake of [3H]-adenosine into C6 glioma cells during 5 min intervals. ITU inhibited isolated AK from C6 cells with an IC50 value of 4 nM. Using a Km value of 2.0 μM for adenosine, this would correspond to a Ki value of 2 nM, which is similar to previously reported values (Jarvis et al., 2000; Wiesner et al., 1999). NH2dAdo inhibited isolated AK with an IC50 value of 1.8 μM, or a Ki value of 0.9 μM, which is 5 – 100 fold higher than previous reports (9.2 – 173 nM) (Jarvis et al., 2000; Wiesner et al., 1999). This may indicate cell type or species differences in the affinity of NH2dAdo for AK. It is clear, however, that NH2dAdo has poor cell penetrability and low potency for AK inhibition in C6 glioma cells (Figures 1B and 3B). ITU has been previously documented to have high cell penetrability, which produces similar inhibitory profiles with whole cell and isolated AK (Jarvis et al., 2000; Wiesner et al., 1999). In our experiments, ITU appeared to permeate wt-C6 cells poorly as ITU did not decrease [3H]-adenosine accumulation unless concentrations were 1000 fold higher than the IC50 value for isolated AK (compare Figures 1A and 4A). The difference between the previous studies and our study appears to be the nucleoside transporter subtypes present in the cell types used. The rat C6 glioma cells contain predominantly rENT2 nucleoside transporters while the previous studies used human neuroblastoma cells (Jarvis et al., 2000) and bovine endothelial cells (Wiesner et al., 1999), which contain ENT1 nucleoside transporters (Jones et al., 1994; Sinclair and Parkinson, unpublished results).

With rENT1 or rCNT2 transfected C6 cells we tested whether nucleoside transporter subtype expression affected the potency and efficacy of ITU or NH2dAdo. As AK inhibitors have been previously demonstrated to inhibit nucleoside transport directly (Davies & Cook, 1995; Henderson et al., 1972; Parkinson & Geiger, 1996; Wu et al., 1984), we investigated the effects of ITU and NH2dAdo on the uptake of 1 μM [3H]-uridine, a nucleoside that is transported by rENT1, rENT2 and rCNT2 but is not metabolized by AK. ITU and NH2dAdo inhibited [3H]-uridine uptake with IC50 values of approximately 10 μM, indicating direct interaction of both AK inhibitors with the nucleoside transporters at micromolar concentrations. ITU and NH2dAdo have been used to inhibit AK in many studies at concentrations of 10 – 50 μM. Our data suggest that, at these concentrations, some of the observed effects may be due to inhibition of nucleoside transporters.

Measurement of [3H]-adenosine uptake during 5 min allowed us to investigate AK- and transporter-mediated effects of ITU and NH2dAdo. While ITU had similar effects in wt-C6 and rCNT2-C6 cells, it produced biphasic inhibition of [3H]-adenosine accumulation in rENT1-C6 cells. NBMPR, a potent and selective inhibitor of rENT1, inhibited the effects of nanomolar concentrations of ITU in the rENT1-C6 cells. This finding indicates that transfection with rENT1 nucleoside transporters facilitated the cellular permeation of ITU into C6 glioma cells. Direct assays of ITU uptake by rENT1 would confirm this interpretation, but these experiments were not feasible. The explanation for the biphasic nature of the inhibition by ITU in these cells is not clear. As 1 μM ITU inhibited AK activity to a greater extent (>80%; Figure 4C) than [3H]-adenosine uptake (∼50%; Figure 4A), it is possible that with AK blocked other metabolic pathways become important in determining [3H]-adenosine uptake, for example adenosine deaminase, purine nucleoside phosphorylase and hypoxanthine guanosine phosphoribosyl transferase. Identification of the intracellular tritium-containing compound is required to clarify this point.

In contrast to the results with ITU, transfection of the C6 cells with either rENT1 or rCNT2 did not affect the potency of NH2dAdo. As NH2dAdo inhibited AK and nucleoside transport at similar concentrations, it is not possible to gain a true understanding of the role of each nucleoside transporter subtype in NH2dAdo-mediated effects.

AK inhibitors have been studied for their effects on heart rate, blood pressure, inflammation, pain, stroke and seizure activity (for review see Kowaluk et al., 1998 or Kowaluk & Jarvis, 2000). The reported benefit of using AK inhibitors relative to adenosine receptor agonists is their proposed site- and event-specific properties, which produce decreased systemic effects such as alterations in heart rate and blood pressure. Our results demonstrate a mechanism through which AK inhibitors such as ITU can have cell or tissue selective sites of action based on nucleoside transporter subtype distribution and expression. As other AK inhibitors are in late pre-clinical and early clinical development (Kowaluk & Jarvis, 2000), it is important to determine the role of the different nucleoside transporters in the effects mediated by these compounds.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). F.E. Parkinson is a CIHR/Regional Partnership Program Investigator. C.J.D. Sinclair and A.E. Powell are recipients of studentship awards from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. C.G. LaRivière is the recipient of an MRC/PMAC student stipend. S.A. Baldwin is supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council of the UK.

Abbreviations

- AK

adenosine kinase

- CNT

concentrative nucleoside transporter

- DPR

dipyridamole

- ENT

equilibrative nucleoside transporter

- ITU

iodotubercidin

- NBMPR

nitrobenzylthioinosine

- NH2dAdo

5′-amino-5′-deoxyadenosine

- NMG

N-methylglucamine

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

References

- BRITTON D.R., MIKUSA J., LEE C.H., JARVIS M.F., WILLIAMS M., KOWALUK E.A. Site and event specific increase of striatal adenosine release by adenosine kinase inhibition in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;266:93–96. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASS C.E., YOUNG J.D., BALDWIN S.A. Recent advances in the molecular biology of nucleoside transporters of mammalian cells. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 1998;76:761–770. doi: 10.1139/bcb-76-5-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHE M., ORTIZ D.F., ARIAS I.M. Primary structure and functional expression of a cDNA encoding the bile canalicular, purine-specific Na(+)-nucleoside cotransporter. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:13596–13599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRAWFORD C.R., PATEL D.H., NAEVE C., BELT J.A. Cloning of the human equilibrative, nitrobenzylmercaptopurine riboside (NBMPR)-insensitive nucleoside transporter ei by functional expression in a transport-deficient cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:5288–5293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIES L.P., COOK A.F. Inhibition of adenosine kinase and adenosine uptake in guinea-pig CNS tissue by halogenated tubercidin analogues. Life Sci. 1995;56:L345–L349. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEIGER J.D., PARKINSON F.E., KOWALUK E.A.Regulators of Endogenous Adenosine Levels as Therapeutic Targets Purinergic Approaches in Experimental Therapeutics 1997New York: Wiley-Liss Inc; 55–84.ed. Jacobson, K.A. & Jarvis, M.F. pp [Google Scholar]

- GRIFFITH D.A., JARVIS S.M. Nucleoside and nucleobase transport systems of mammalian cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1286:153–181. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(96)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIFFITHS M., BEAUMONT N., YAO S.Y., SUNDARAM M., BOUMAH C.E., DAVIES A., KWONG F.Y., COE I., CASS C.E., YOUNG J.D., BALDWIN S.A. Cloning of a human nucleoside transporter implicated in the cellular uptake of adenosine and chemotherapeutic drugs [see comments] Nat. Med. 1997a;3:89–93. doi: 10.1038/nm0197-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIFFITHS M., YAO S.Y., ABIDI F., PHILLIPS S.E., CASS C.E., YOUNG J.D., BALDWIN S.A. Molecular cloning and characterization of a nitrobenzylthioinosine-insensitive (ei) equilibrative nucleoside transporter from human placenta. Biochem. J. 1997b;328:739–743. doi: 10.1042/bj3280739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENDERSON J.F., PATERSON A.R., CALDWELL I.C., PAUL B., CHAN M.C., LAU K.F. Inhibitors of nucleoside and nucleotide metabolism. Cancer Chemother. Rep. [2] 1972;3:71–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG Q.Q., YAO S.Y., RITZEL M.W., PATERSON A.R., CASS C.E., YOUNG J.D. Cloning and functional expression of a complementary DNA encoding a mammalian nucleoside transport protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:17757–17760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JARVIS M.F., YU H., KOHLHAAS K., ALEXANDER K., LEE C.H., JIANG M., BHAGWAT S.S., WILLIAMS M., KOWALUK E.A. ABT-702 (4-amino-5-(3-bromophenyl)-7-(6-morpholinopyridin-3-yl)pyrido[2, 3-d]pyrimidine), a novel orally effective adenosine kinase inhibitor with analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties: I. In vitro characterization and acute antinociceptive effects in the mouse [In Process Citation] J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;295:1156–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES K.W., RYLETT R.J., HAMMOND J.R. Effect of cellular differentiation on nucleoside transport in human neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. 1994;660:104–112. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90844-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOWALUK E.A., BHAGWAT S.S., JARVIS M.F. Adenosine kinase inhibitors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 1998;4:403–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOWALUK E., JARVIS M. Therapeutic potential of adenosine kinase inhibitors. Exp. Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2000;9:551–564. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER R.L., ADAMCZYK D.L., MILLER W.H., KOSZALKA G.W., RIDEOUT J.L., BEACHAM L.M.D., CHAO E.Y., HAGGERTY J.J., KRENITSKY T.A., ELION G.B. Adenosine kinase from rabbit liver. II. Substrate and inhibitor specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:2346–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARKINSON F.E., GEIGER J.D. Effects of iodotubercidin on adenosine kinase activity and nucleoside transport in DDT1 MF-2 smooth muscle cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;277:1397–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RITZEL M.W., NG A.M., YAO S.Y., GRAHAM K., LOEWEN S.K., SMITH K.M., RITZEL R.G., MOWLES D.A., CARPENTER P., CHEN X.Z., KARPINSKI E., HYDE R.J., BALDWIN S.A., CASS C.E., YOUNG J.D. Molecular identification and characterization of novel human and mouse concentrative Na{super+}-nucleoside cotransporter proteins (hCNT3 and mCNT3) broadly selective for purine and pyrimidine nucleosides (system cib) J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:2914–2927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007746200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RITZEL M.W., YAO S.Y., NG A.M., MACKEY J.R., CASS C.E., YOUNG J.D. Molecular cloning, functional expression and chromosomal localization of a cDNA encoding a human Na+/nucleoside cotransporter (hCNT2) selective for purine nucleosides and uridine. Mol. Membr. Biol. 1998;15:203–211. doi: 10.3109/09687689709044322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSENBERG P.A., LI Y., LE M., ZHANG Y. Nitric oxide-stimulated increase in extracellular adenosine accumulation in rat forebrain neurons in culture is associated with ATP hydrolysis and inhibition of adenosine kinase activity. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:6294–6301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06294.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINCLAIR C.J., LARIVIERE C.G., YOUNG J.D., CASS C.E., BALDWIN S.A., PARKINSON F.E. Purine uptake and release in rat C6 glioma cells: nucleoside transport and purine metabolism under ATP-depleting conditions. J. Neurochem. 2000a;75:1528–1538. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINCLAIR C., SHEPEL P., GEIGER J., PARKINSON F.E. Stimulation of Nucleoside Efflux and Inhibition of Adenosine Kinase by A1 Adenosine Receptor Activation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000b;59:477–483. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIESNER J.B., UGARKAR B.G., CASTELLINO A.J., BARANKIEWICZ J., DUMAS D.P., GRUBER H.E., FOSTER A.C., ERION M.D. Adenosine kinase inhibitors as a novel approach to anticonvulsant therapy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;289:1669–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU P.H., BARRACO R.A., PHILLIS J.W. Further studies on the inhibition of adenosine uptake into rat brain synaptosomes by adenosine derivatives and methylxanthines. Gen. Pharmacol. 1984;15:251–254. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(84)90169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAO S.Y., NG A.M., MUZYKA W.R., GRIFFITHS M., CASS C.E., BALDWIN S.A., YOUNG J.D. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of nitrobenzylthioinosine (NBMPR)-sensitive (es) and NBMPR-insensitive (ei) equilibrative nucleoside transporter proteins (rENT1 and rENT2) from rat tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28423–28430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAO S.Y., NG A.M., RITZEL M.W., GATI W.P., CASS C.E., YOUNG J.D. Transport of adenosine by recombinant purine- and pyrimidine-selective sodium/nucleoside cotransporters from rat jejunum expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:1529–1535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]