Abstract

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were transiently transfected with the mouse prostacyclin (mIP) receptor to examine IP agonist-mediated stimulation of [3H]-cyclic AMP and [3H]-inositol phosphate production.

The prostacyclin analogues, cicaprost, iloprost, carbacyclin and prostaglandin E1, stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity with EC50 values of 5, 6, 25 and 95 nM, respectively. These IP agonists also stimulated the phospholipase C pathway with 10 – 40 fold lower potency than stimulation of adenylyl cyclase.

The non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics, octimibate, BMY 42393 and BMY 45778, also stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity, with EC50 values of 219, 166 and 398 nM, respectively, but failed to stimulate [3H]-inositol phosphate production.

Octimibate, BMY 42393 and BMY 45778 inhibited iloprost-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate production in a non-competitive manner.

Activation of the endogenously-expressed P2 purinergic receptor by ATP led to an increase in [3H]-inositol phosphate production which was inhibited by the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics in non-transfected CHO cells. Prostacyclin analogues and other prostanoid receptor ligands failed to inhibit ATP-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate production.

A comparison between the IP receptor-specific non-prostanoid ONO-1310 and the structurally-related EP3 receptor-specific agonist ONO-AP-324, indicated that the inhibitory effect of non-prostanoids was specific for those compounds known to activate IP receptors.

The non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics also inhibited phospholipase C activity when stimulated by constitutively-active mutant GαqRC, Gα14RC and Gα16QL transiently expressed in CHO cells. These drugs did not inhibit adenylyl cyclase activity when stimulated by the constitutively-active mutant GαsQL.

These results suggest that non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics can specifically inhibit [3H]-inositol phosphate production by targeting Gq/11 and/or phospholipase C in CHO cells, and that this effect is independent of IP receptors.

Keywords: IP receptor agonists, non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics, phospholipase C

Introduction

Activation of the prostacyclin (IP) receptor leads to stimulation of adenylyl cyclase through coupling to Gs, and to pertussis toxin-insensitive activation of phospholipase C, through coupling to Gq/11 ((Namba et al., 1994); see Wise & Jones (2000) for review of IP receptor coupling). The IP agonist iloprost induces rapid phosphorylation of the human IP receptor expressed in HEK293 cells, at concentrations comparable to those needed to activate phospholipase C (Smyth et al., 1996), and elimination of the consensus sequences for protein kinase C phosphorylation attenuates coupling to Gq/11 and prevents agonist-dependent desensitization (Smyth et al., 1998).

Given the multiple G protein coupling capacity of the IP receptor, we decided to test a range of IP agonists which fall into two structural groups: (1) prostacyclin analogues, and (2) non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics (Figure 1). The latter group includes BMY 42393 and BMY 45778 which evolved from the discovery of octimibate (Seiler et al., 1990; Meanwell et al., 1994), and ONO-1301 (Torisu et al., 1996). We show here that the prostacyclin analogues can stimulate both adenylyl cyclase and phospholipase C activity in CHO cells transfected with the mouse IP receptor, but the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics can only stimulate adenylyl cyclase.

Figure 1.

The structures of prostacyclin analogues (cicaprost, iloprost, PGE1 and carbacyclin) and non-prostanoids (octimibate, BMY 42393, BMY 45778, ONO-1301 and ONO-AO-324).

We attempted to determine affinity constants for the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics by measuring their ability to produce a rightward shift of the log concentration-response curves for iloprost-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation. To our surprise, we found that octimibate, BMY 42393 and BMY 45778 did not behave as competitive antagonists for the IP receptor, but gave a pattern of responses expected of a non-competitive interaction (Figure 5). This non-competitive nature of octimibate and related compounds could be caused by a direct inhibitory effect on intracellular signalling pathways downstream of the IP receptor. We therefore chose to continue our studies using wild-type CHO cells, since these cells produce only a relatively small adenylyl cyclase response to cicaprost (data not shown), and presumably therefore lack considerable expression of endogenous IP receptors. In order to stimulate the Gq/11-phospholipase C pathway, we made use of the P2 purinergic receptor which is endogenously expressed in CHO cells (Megson et al., 1995). To examine effects downstream of G protein-coupled receptors, we utilized constitutively-active mutant (CAM) forms of pertussis toxin-insensitive Gα subunits: GαqRC (Conklin et al., 1992); Gα14RC (Chan et al., 2000), Gα16QL (Heasley et al., 1996), and GαsQL (Masters et al., 1989). The results presented in this current paper attempt to explain these observations on the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics by a mechanism of action independent of effects on the IP receptor. A preliminary report of some of this work has been presented previously (Wise et al., 2001).

Figure 5.

Effect of octimibate on iloprost-stimulated phospholipase C activity. CHO cells were transfected with mIP (0.5 μg ml−1) and stimulated with IP agonists 48 h post-transfection. [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation was determined in duplicate as described in Methods. Values are means±s.d. from one experiment, typical of two other experiments using BMY 42393 and BMY 45778 in place of octimibate. Error bars within the size of the symbols are not shown.

Methods

Cell culture

CHO cells were cultured in Ham's F-12 medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum, 100 units ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C.

Transient transfection of cells

For the agonist log concentration-response curves, [3H]-cyclic AMP assays were performed using CHO cells grown to approximately 80% confluency in cell culture flasks, then transfected using LipofectAMINE liposome reagent and Opti-mem I reduced serum medium for 5 h, according to the manufacturer's instructions. At 24 h after transfection, CHO cells were harvested by trypsinization and seeded at 2×105 cells in 12-well culture plates containing 1 ml Ham's F-12 medium plus antibiotics and 1% foetal bovine serum. For studies of GαsQL activity, CHO cells were transfected in 12-well culture plates and maintained in 1 ml Ham's F-12 plus antibiotics and 10% foetal bovine serum. For [3H]-inositol phosphate assays, CHO cells were transfected at 80% confluency in 12-well plates and maintained in 1 ml Ham's F-12 plus antibiotics and 10% foetal bovine serum. All transfected cells were assayed 48 h post-transfection, when cells were 80 – 90% confluent. For assays on wild-type CHO cells, assays were performed in 12-well plates on cells at 80 – 90% confluency.

Measurement of [3H]-cyclic AMP production

[3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation was assayed in 12-well plates following overnight incubation of cells (16 – 20 h) with [3H]-adenine (1 μCi well−1; 1 μCi ml−1). The medium was aspirated and the cells washed twice with 1 ml HEPES-buffered saline (HBS (mM): HEPES 15, pH 7.4, NaCl 140, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 2.2, MgCl2 1.2, KH2PO4 1.2, glucose 11). Cells were challenged, in duplicate, with test compounds for 30 min at 37°C in assay buffer (HBS containing 1 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methyl xanthine (IBMX) to inhibit phosphodiesterase activity, and 3 μM indomethacin to inhibit tonic prostanoid synthesis). The reaction was terminated by aspiration and addition of 1 ml ice-cold 5% trichloroacetic acid containing 1 mM ATP. The plates were left for at least 60 min on ice before separating the [3H]-cyclic AMP from [3H]-ATP by column chromatography (Barber et al., 1980). Cell samples were loaded onto Dowex AG50W-X4 (200 – 400 mesh) columns and [3H]-ATP eluted with 3 ml distilled water. A further 10 ml distilled water was added and the eluant loaded directly onto a neutral alumina column, which was eluted with 6 ml 0.1 M imidazole buffer, pH 7.5, to give a fraction containing [3H]-cyclic AMP. Scintillator (OptiPhase ‘HiSafe' 3, 10 ml) was added for scintillation counting.

The production of [3H]-cyclic AMP from cellular [3H]-ATP in the presence of a phosphodiesterase inhibitor (i.e., adenylyl cyclase activity) was estimated as the ratio of radiolabelled cyclic AMP to total AXP (i.e., adenine, cyclic AMP, ADP and ATP), and is expressed as per cent conversion ([cyclic AMP]/[total AXP]×100%). All assays were performed in duplicate. Solvent controls were run as appropriate, but neither dimethylsulfoxide nor ethanol interfered with the assay at the concentrations used.

Measurement of [3H]-inositol phosphate production

[3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation was assayed in 12-well plates following 42 h incubation of cells with [3H]-myo-inositol (2 μCi well−1; 2 μCi ml−1). The medium was aspirated and the cells washed twice with 1 ml HBS followed by 10 min incubation at 37°C in HBS containing 20 mM LiCl and 3 μM indomethacin. The buffer was removed and replaced with fresh buffer containing agonists for a further 60 min. The reaction was terminated by aspiration and addition of 0.75 ml ice-cold 20 mM formic acid. The plates were left for at least 60 min on ice for the extraction of acid soluble [3H]-total inositol (i.e., inositol and inositol phosphates). [3H]-inositol phosphates were separated from the [3H]-total inositol fraction by column chromatography (Conklin et al., 1992). Cell samples were loaded onto Dowex AG1-X8 (100 – 200 mesh) columns, immediatedly followed by 3 ml ammonia solution (0.05%) to elute the [3H]-inositol fraction. After washing the columns with 4 ml 40 mM ammonium formate/0.1 M formic acid, bound [3H]-inositol phosphates were eluted with 5 ml 2 M ammonium formate/0.1 M formic acid. Scintillator (OptiPhase ‘HiSafe' 3, 10 ml) was added for scintillation counting.

The production of [3H]-inositol phosphates was estimated as the ratio of radiolabelled inositol phosphates to total inositol and is expressed as per cent conversion ([inositol phosphates]/[total inositol]×100%). Assays were performed in duplicate for agonist concentration-response curves, and in triplicate for the ATP and CAM Gα studies. Solvent controls were run as appropriate, but neither dimethylsulfoxide nor ethanol interfered with the assays at the concentrations used.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assayed using the CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Reagent, according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 2×103 CHO cells were seeded in 96-well culture plates, and maintained in 100 μl Ham's F-12 plus antibiotics and 10% foetal bovine serum for 3 days. The cells were washed twice with 100 μl HBS then incubated in 100 μl HBS containing 3 μM indomethacin plus 10 μM test compound or HBS as control. After 60 min in a 37°C incubator, the solution was removed and replaced with 100 μl HBS plus indomethacin, and 20 μl CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Reagent. After a further 4 h incubation, absorbance values were determined at 490 nm. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Data analysis

Values for EC50 and Emax, the maximum effect, were obtained by fitting the log concentration-response curves to the standard four-parameter logistic equation using GraphPad Prism software version 3.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, U.S.A.):

where E is the measured response, Emin and Emax are the minimum and maximum asymptotes, EC50 is obtained from the ‘location parameter' of the curve, x is the concentration and n is the Hill coefficient. pEC50 is the negative logarithm of the EC50 value for stimulation of adenylyl cyclase or phospholipase C activity. Except for the data shown in Figure 2, log concentration-response curves for CHO cells transfected with mIP have been normalized against the maximum fitted responses to cicaprost obtained in each experiment to account for any variability in transfection efficiency. Fold basal values (i.e., stimulated divided by basal activity) have been provided in figure legends for reference. Intrinsic activity values are the maximum agonist responses compared to the maximum cicaprost response obtained in the same experiment.

Figure 2.

Activation of adenylyl cyclase and phospholipase C by cicaprost. CHO cells were transfected with mIP (0.5 μg ml−1) and stimulated with cicaprost 48 h post-transfection. [3H]-cyclic AMP and [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation was determined as described in Methods. Values are means±s.e.mean and error bars within the size of the symbols are not shown. Basal [3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation was 0.09±0.01% conversion, n=10, and basal [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation was 5.00±0.87% conversion, n=3.

In order to account for any changes in basal phospholipase C activity in studies looking at the effect of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics on responses to ATP or CAM Gα's, results were calculated as stimulated minus basal activity. pIC50 is the negative logarithm of the IC50 value for inhibition of ATP-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate production.

Values reported are means±s.e.mean unless otherwise stated. Comparisons between groups were made using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's or Dunnett's post-tests, or Student's t-test, as appropriate. Statistical significance is taken as P<0.05.

Drugs

8-[3H]-adenine (specific activity 27 Ci mmol−1) was purchased from Amersham (Far East) Trading Ltd and myo-[2-3H]-inositol (20 Ci mmol−1) from NEN Life Science Products, Inc., (U.S.A.). Dowex AG50W-X4 (200 – 400 mesh) and Dowex AG1-X8 (100 – 200 mesh, formate form) were purchased from Bio-Rad (U.S.A.), and OptiPhase ‘HiSafe' 3 scintillant from Pharmacia Biotech Far East Ltd. CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Reagent was purchased from Promega (U.S.A.). All other compounds were supplied by Gibco (U.S.A.) or Sigma (U.S.A.). The following gifts are also gratefully acknowledged: cDNA for the mouse IP receptor from T. Kobayashi (Department of Pharmacology, Kyoto University); cicaprost and iloprost from Schering AG (Germany); BMY 42393, BMY 45778 and octimibate from Bristol-Myers Squibb (U.S.A.); ONO-1301 and ONO-AP-324 from ONO Pharmaceuticals (Japan).

Results

Multiple coupling of mIP receptors

In CHO cells transiently expressing the mIP receptor at physiological concentrations (approximately 100 fmol mg protein−1 (Wise, 1999)), the standard IP agonist cicaprost activated both adenylyl cyclase and phospholipase C with mean EC50 values of 5 nM and 135 nM, respectively (Figure 2). Cicaprost produced a 7.72-fold stimulation of adenylyl cyclase activity, and a 3.66-fold stimulation of phospholipase C activity. The other prostacyclin analogues iloprost, prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) and carbacyclin also stimulated both adenylyl cyclase and phospholipase C activity (Figure 3) with an approximately 10 – 40 fold difference in potency between the two pathways (Tables 1 and 2). The prostacyclin analogues consistently displayed shallow log concentration-response curves for activation of adenylyl cyclase, but steep log concentration-response curves for activation of phospholipase C (Tables 1 and 2). The non-specific IP agonist PGE1 produced a significantly greater maximal activation of adenylyl cyclase compared with cicaprost (P<0.01, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-tests). The intrinsic activity of the prostacyclin analogues, compared with cicaprost, tended to be lower in the phospholipase C compared with the adenylyl cyclase assay. Indeed, carbacyclin produced significantly lower maximal activation of phospholipase C compared with cicaprost (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-tests).

Figure 3.

Dual coupling of mIP receptors. CHO cells were transfected with mIP (0.5 μg ml−1) and stimulated with prostacyclin analogues 48 h post-transfection. [3H]-cyclic AMP and [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation was determined as described in Methods. Values are means±s.e.mean for at least three experiments. Error bars within the size of the symbols are not shown. [3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation has been normalized against the maximum fitted response to cicaprost in each experiment (7.72±1.29 fold basal), with basal activity of 0.09±0.01% conversion. [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation has been normalized against the maximum fitted response to cicaprost in each experiment (3.66±0.69 fold basal), with basal activity of 9.28±1.66% conversion. Dotted lines represent the maximum response to cicaprost.

Table 1.

The potency of IP agonists for stimulating adenylyl cyclase

Table 2.

The potency of IP agonists for stimulating phospholipase C

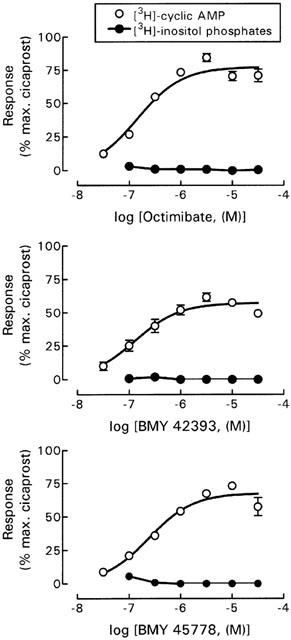

As expected (Meanwell et al., 1994), the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics (octimibate, BMY 42393 and BMY 45778) behaved as partial agonists for stimulation of adenylyl cyclase activity (Figure 4), and except for BMY 45778, the Hill coefficients for the log concentration-response curves were not significantly different from unity (Table 1). BMY 42393 produced significantly lower maximal activation of adenylyl cyclase compared with cicaprost (P<0.01, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-tests). None of these compounds was able to stimulate the production of [3H]-inositol phosphates at concentrations up to 30 μM (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics fail to stimulate phospholipase C. CHO cells were transfected with mIP (0.5 μg ml−1) and stimulated with non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics 48 h post-transfection. [3H]-cyclic AMP and [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation was determined as described in Methods. Values are means±s.e.mean for at least three experiments. Error bars within the size of the symbols are not shown. [3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation has been normalized against the maximum fitted response to cicaprost in each experiment (7.72±1.29 fold basal), with basal activity of 0.09±0.01% conversion. [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation has been normalized against the maximum fitted response to cicaprost in each experiment (3.66±0.69 fold basal), with basal activity of 9.28±1.66% conversion.

Effect of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics on iloprost-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate production

We attempted to determine affinity constants for the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics by measuring their ability to produce a rightward shift of the log concentration-response curves for iloprost-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation. CHO cells transiently expressing mIP receptors were co-stimulated for 60 min with varying concentrations of iloprost and a fixed concentration of octimibate or related compound. Octimibate inhibited iloprost-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate production in a concentration-dependent manner producing approximately 39, 53 and 83% inhibition of maximal iloprost responses at 0.1, 1.0 and 10 μM, respectively (Figure 5). Both BMY 42393 and BMY 45778 produced similar response profiles (data not shown).

Effects of prostanoid receptor agonists on ATP-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate production

Wild-type (non-transfected) CHO cells were incubated for 10 min with test compounds (1 and 30 μM) before the addition of 100 μM ATP for a further 60 min. The non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics octimibate, BMY 42393, BMY 45778 and ONO-1301 produced a significant concentration-dependent inhibition of ATP-stimulated phospholipase C activity (Figure 6A), without any consistent effect on basal [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation (data not shown). In contrast, the non-prostanoid EP3 receptor agonist ONO-AP-324 (Figure 1), which is a close structural relative of ONO-1301 (Koketsu et al., 1996), was inactive (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Effect of prostanoid receptor agonists on ATP-stimulated phospholipase C activity. Wild-type CHO cells were stimulated with ATP (100 μM) in the presence or absence of prostanoid receptor agonists, and stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation determined relative to a control group. (A) Non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics, (B) Prostacyclin analogues, (C) Prostanoid receptor agonists. Values are means±s.e.mean for three experiments. Control ATP-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation was 28.10±1.35% conversion above basal, where basal activity was 6.72±0.40% conversion.

None of the structural analogues of prostacyclin, i.e. cicaprost, iloprost, PGE1 and carbacyclin, had any effect alone, or on ATP-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation (Figure 6B). Similarly, prostaglandin D2 (DP agonist), prostaglandin E2 (EP agonist), prostaglandin F2α (FP agonist) and U46619 (TP agonist) had no effect either alone or in the presence of ATP (Figure 6C).

ATP stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate production had a steep log concentration-response relationship in CHO cells (Hill coefficient 2.67±0.83, n=3) with a pEC50 value of 5.62±0.04 (n=3). pIC50 values for the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics were subsequently determined against the pEC50 concentration of ATP (i.e. 3 μM). For comparison, we intended to study the phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 (Smith et al., 1990), but in conformation of the work of Walker et al. (1998), we noted that U-73122 appeared to be cytotoxic for CHO cells. However, none of the IP agonists tested appeared to be cytotoxic at 30 μM using the Trypan blue exclusion test. Subsequent microscopic examination of CHO cells indicated a change in cell morphology with octimibate, BMY 42393, BMY 45778 and ONO-1301 at 30 μM, therefore test concentrations were limited to 10 μM for the following experiments.

pIC50 values for inhibition of ATP-stimulation [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation were determined after constraining the top of the curve to 100% control: octimibate, 6.04±0.01; BMY 42393, 5.33±0.08; BMY 45778, 6.05±0.25; ONO-1301, 5.14±0.30; n=3 (Figure 7). From the fitted data, it would be predicted that octimibate, BMY 42393 and ONO-1301 would produce complete inhibition of ATP-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate production (octimibate, 91±7%; BMY 42393, 104±4%; ONO-1301, 100±0% inhibition, n=3). In contrast, BMY 45778 produced significantly less inhibition of ATP-stimulated responses (46±10% inhibition, n=3; P<0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-tests).

Figure 7.

Inhibitory potency of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics against receptor-stimulated phospholipase C activity. Wild-type CHO cells were stimulated with the EC50 concentration of ATP (3 μM) following a 10 min preincubation with non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics. Values are means±s.e.mean for three experiments. Error bars within the size of the symbols are not shown. Control ATP-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation was 34.35±4.39% conversion above basal, where basal activity was 6.12±1.00% conversion.

Inhibitory effect of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics against non-receptor stimulated phospholipase C activity

CHO cells were transfected with pcDNA1.1 (0.65 μg ml−1; vector control group), Gα14RC (0.65 μg ml−1), GαqRC (0.45 μg ml−1) or Gα16QL (0.45 μg ml−1). Total plasmid DNA transfected was held constant for all groups at 0.65 μg ml−1 by addition of pcDNA1.1. Basal [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation was increased by 3.7, 9.4 and 12.3 fold in CHO cells transfected with Gα14RC, GαqRC or Gα16QL, respectively (see legend Figure 8). Octimibate, BMY 42393, BMY 45778 and ONO-1301 (all at 10 μM) significantly inhibited (P<0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post-tests) both basal and elevated [3H]-inositol phosphate levels caused by the CAM Gα proteins (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Inhibitory effect of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics against non-receptor stimulated phospholipase C activity. CHO cells were transfected with pcDNA1.1 (0.65 μg ml−1; vector control group), Gα14RC (0.65 μg ml−1), GαqRC (0.45 μg ml−1 plus 0.20 μg ml−1 pcDNA1.1), or Gα16QL (0.45 μg ml−1 plus 0.20 μg ml−1 pcDNA1.1). The effect of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics on [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation was determined 48 h post-transfection. Basal [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation in the absence of drugs was 4.30±0.37% conversion for pcDNA1.1 and 15.81±4.88% conversion for Gα14RC, 40.44±6.74% conversion for GαqRC, and 52.92±8.49% conversion for Gα16QL. Values are means±s.e.mean for three experiments.

Effect of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics against non-receptor stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity

CHO cells were transfected with pcDNA1.1 (0.5 μg ml−1; vector control group) or GαsQL (0.5 μg ml−1). In the control group, octimibate, BMY 42393, BMY 45778 and ONO-1301 (all at 10 μM) each produced a small (approximately 1.3 fold) but significant (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post-tests) increase in basal [3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation (Figure 9), representing less than 7% the response seen in CHO cells transfected with mIP. GαsQL increased basal [3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation by 6.5 fold (see legend Figure 9), but this elevated adenylyl cyclase activity was not inhibited by octimibate, BMY 42393, BMY 45778 or ONO-1301.

Figure 9.

Effect of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics against non-receptor stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity. CHO cells were transfected with pcDNA1.1 (0.5 μg ml−1; vector control group) or GαsQL (0.5 μg ml−1) and assayed 48 h post-transfection. Basal [3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation determined in the absence of drugs was 0.061±0.008% conversion for pcDNA1.1 and 0.397±0.165% conversion for GαsQL. Values are means±s.e.mean for three experiments.

Effect of drugs on cell viability

The non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics produced a concentration-dependent shape change in CHO cells (data not shown) at concentrations higher than those needed to observe significant inhibition of ATP-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation. To further investigate the effect of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics on cell viability, CHO cells were treated for 60 min with non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics (10 μM) or control buffer, before addition of CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Reagent. BMY 42393, BMY 45778 and ONO-1301 had no significant effect on CHO cell viability (O.D. (490 nm) readings were 103±4, 106±5, and 99±5% control, respectively n=3). Octimibate at 10 μM significantly decreased cell viability (P<0.01, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-tests) with O.D. (490 nm) readings of 59±13% control, n=4. Control O.D. (490 nm) values were 0.822±0.071, n=5.

Discussion

Prostacyclin analogues such as cicaprost, iloprost, PGE1 and carbacyclin stimulated both adenylyl cyclase and phospholipase C pathways in CHO cells transiently expressing mIP receptors, with 10 – 40 fold difference in potency for the two signalling pathways. The maximal stimulation of adenylyl cyclase activity by PGE1 was significantly greater than that observed with the specific IP agonist cicaprost, presumably due to the ability of PGE1 to stimulate other Gs-coupled receptors endogenously expressed in CHO cells, i.e., EP2 or EP4 receptors. The intrinsic activity of carbacyclin in the phospholipase C assay was significantly lower than that of cicaprost. Taken together, these results reaffirm (see Wise & Jones, 2000) the need to use cicaprost, rather than PGE1 or carbacyclin, as the standard IP agonist for pharmacological investigations.

Previous reports have indicated that in normal cells, e.g. rat dorsal root ganglion cells in vitro (Smith et al., 1998), and in transformed cell lines (Watanabe et al., 1991; Vassaux et al., 1992; Oka et al., 1993), IP agonist potencies for stimulating cyclic AMP and inositol phosphate production and increasing Ca2+ mobilization are similar, but the sensitivity of the adenylyl cyclase response is 1000 fold higher than phospholipase C activation in transfected cells over-expressing IP receptors (Namba et al., 1994; Katsuyama et al., 1994; Smyth et al., 1996). It is possible however that when IP receptors are expressed in the physiological range (i.e., as in the current study), then IP receptor coupling to both Gs and Gq/11 coupled pathways can more easily occur. It is surprising therefore that the reports of IP receptor coupling to Gq/11 in normal cells are rare (e.g., rat dorsal root ganglion cells in vitro (Smith et al., 1998) and piglet cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells in vitro (Parkinson et al., 2000)).

The log concentration-response curves for activation of adenylyl cyclase by prostacyclin analogues were consistently shallow (significantly different from unity), while for all except cicaprost, their Hill coefficients were significantly greater than unity in the phospholipase C assay. Since cicaprost, iloprost, PGE1 and carbacyclin can simultaneously activate both Gs- and Gq-coupled pathways in CHO cells transfected with mIP, it is possible that we are looking at the result of crosstalk between these two pathways. However, preliminary studies fail to support the idea that activation of protein kinase A (through Gs) enhances coupling of mIP to Gq, while activation of protein kinase C (through Gq) attenuates coupling of mIP to Gs (Kam et al., 2001). Further studies are in progress to examine this issue.

In contrast to the prostacyclin analogues, we found that the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics (octimibate, BMY 42393 and BMY 45778) failed to increase [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation within the predicted micromolar concentration range. However, the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics did inhibit both iloprost-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation in mIP-CHO cells (Figure 5), and ATP-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation in CHO cells lacking IP receptors (Figure 7), within the micromolar range. Taken together, these results suggested the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics are unlikely to be acting as receptor antagonists, but rather as inhibitors of Gq/11 or of phospholipase C. By using CAM forms of Gαq and related G proteins, one can elevate phospholipase C activity independently of receptor activation. Indeed, because Gα16QL is ‘locked' in the GTP-bound state, it is unresponsive to activation by G protein-coupled receptors (Heasley et al., 1996). Therefore, if the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics inhibited only one of the CAM Gα subunits, we could identify the G protein, rather than phospholipase C, as the target protein. However, the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics inhibited phospholipase C activity stimulated by GαqRC, Gα14RC and Gα16QL, indicating that the site of action of these compounds still remains to be identified as either the Gα subunits and/or phospholipase C itself. The observation that the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics failed to inhibit adenylyl cyclase activity stimulated by GαsQL suggests that we are not looking simply at non-specific inhibition of G protein-mediated functions.

The ability of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics to inhibit ATP-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation in CHO cells lacking IP receptors is not only specific for the phospholipase C pathway, but is also specific for the non-prostanoid structure, since prostacyclin analogues and other prostanoid receptor ligands lack this property. Furthermore, the EP3-specific non-prostanoid ONO-AP-324, which is a close structural analogue of the IP-specific non-prostanoid ONO-1301 (Koketsu et al., 1996), was also inactive. Therefore, the ability of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics to inhibit ATP-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphate accumulation in CHO cells lacking IP receptors is not simply dependent on the non-prostanoid structure of octimibate, BMY 42393, BMY 45778 and ONO-1301, but is a property dependent on the ability of these compounds to be recognized by the IP receptor. Moreover, octimibate is consistently less potent, and usually less efficacious, than BMY 45778 in conventional assessments of IP agonist activity (Wise & Jones, 2000). However, the reverse situation is observed in their inhibition of ATP-stimulated phospholipase C activity, as BMY 45778 produced significantly less inhibition than octimibate. Therefore, the ability to be recognized by the IP receptor is not sufficient alone to determine the inhibitory activity of these non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics.

The studies on GαsQL showed a small, but significant, increase in [3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation in response to the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics, in wild-type CHO cells, suggesting either a low level expression of endogenous IP receptors, or possible activation of adenylyl cyclase via some other pathway. However, any endogenous IP receptors are unlikely to contribute to the phospholipase C inhibitory activity of the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics, because the more potent prostacyclin analogues were inactive in this regard. Unfortunately, the absence of any available IP receptor antagonists prevents full confirmation of this conclusion.

The discovery of this novel property of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics may have implications for their use in the classification of IP receptors. For example, we have used octimibate, BMY 42393 and BMY 45778 to suggest that IP receptors in the rat enteric nervous system differ from the classical platelet-like IP receptor (Wise et al., 1995). This conclusion remains valid however because, if the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics were inhibiting phospholipase C activity in the rat colon, we might predict a greater overall inhibition of contractile activity than observed. Where the new results have greater impact is on studies aimed at looking at the correlation between cyclic AMP-elevating properties of IP agonists with their functional effects. For example, the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics, especially octimibate, are low efficacy agonists for stimulation of cyclic AMP production in rat peritoneal neutrophils, yet are potent, full inhibitors of formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine-stimulated neutrophil aggregation (Wise, 1996). One may now consider that it was the phospholipase C-inhibitory activity of the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics, rather than their cyclic AMP-elevating properties, which was responsible for their potent inhibition of rat peritoneal neutrophil aggregation.

Unfortunately, we cannot take further advantage of these non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics as inhibitors of phospholipase C because these compounds remain primarily IP agonists. Since IP receptors are widely expressed in the body, it would become difficult to differentiate between these two properties in most normal tissues/cells. While one could use wild-type CHO cells lacking IP receptors to focus on the phospholipase C inhibitory properties of these compounds, one must caution that both U-73122 (Megson et al., 1995) and the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics produce a morphological change in CHO cells, and that octimibate (but not BMY 42393, BMY 45778 and ONO-1301) appears to decrease cell viability after 60 min incubation at 10 μM. Whether or not the change in CHO cell morphology and the phospholipase C-inhibitory activity of U-73122 and the non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics are related would require further investigation.

In conclusion, non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics can inhibit both receptor-dependent and receptor-independent activation of phospholipase C in CHO cells, by an effect which is dependent on their non-prostanoid structure with specificity towards IP receptors, but is independent of the presence of IP receptors. At the present time, the development of new ligands for IP receptors has tended to focus on ligands which are non-prostanoid in structure. In light of our current observations, it would be prudent to test all these compounds for possible inhibition of phospholipase C activity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Schering AG (Germany) for the gifts of cicaprost and iloprost, Bristol-Myers Squibb (U.S.A.) for BMY 42393, BMY 45778 and octimibate and ONO Pharmaceuticals (Japan) for ONO-1301 and ONO-AP-324. Also gratefully acknowledged is the gift of cDNA for the mouse IP receptor from T. Kobayashi (Department of Pharmacology, Kyoto University). The work described in this paper was fully supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (CUHK4253/99M).

Abbreviations

- BMY 42393

2-[3-[2-(4,5-diphenyl-2-oxazolyl)ethyl]phenoxy]acetic acid

- BMY 45778

[3-[4-(4,5-diphenyl-2-oxazolyl)-5-oxazolyl]phenoxy]acetic acid

- CAM

constitutively active mutant

- CHO cells

Chinese hamster ovary cells

- HBS

HEPES-buffered saline

- [3H]-IP

[3H]-inositol phosphates

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methyl xanthine

- mIP

mouse prostacyclin receptor

- octimibate (BMY 22389)

8-[1,4,5-triphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl-oxy]octanoic acid

- ONO-1301

7,8-dihydro-5-(2-(1-phenyl-1-pyrid-3-yl-methiminoxy)-ethyl)-α-naphthyloxyacetic acid

- ONO-AP-324

(5-(2-diphenylmethyl aminocarboxy)-ethyl)-α-naphthyloxyaceticacid

- PGE1

prostaglandin E1

- U-73312

1-[6-[[17β-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl]amino]hexyl]-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione

References

- BARBER R., RAY K.P., BUTCHER R.W. Turnover of adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate in WI-38 cultured fibroblasts. Biochemistry. 1980;19:2560–2567. doi: 10.1021/bi00553a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAN J.S., LEE J.W., HO M.K., WONG Y.H. Preactivation permits subsequent stimulation of phospholipase C by Gi-coupled receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;57:700–708. doi: 10.1124/mol.57.4.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONKLIN B.R., CHABRE O., WONG Y.H., FEDERMAN A.D., BOURNE H.R. Recombinant Gqα. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEASLEY L.E., ZAMARRIPA J., STOREY B., HELFRICH B., MITCHELL F.M., BUNN P.A., JOHNSON G.L. Discordant signal transduction and growth inhibition of small cell lung carcinomas induced by expression of GTPase-deficient Gα16. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:349–354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAM Y.W., CHOW K.B.S., WISE H. Factors affecting prostacyclin receptor agonist efficacy in different cell types. Cell. Signalling. 2001;13:841–847. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATSUYAMA M., SUGIMOTO Y., NAMBA T., IRIE A., NEGISHI M., NARUMIYA S., ICHIKAWA A. Cloning and expression of a cDNA for the human prostacyclin receptor. FEBS Lett. 1994;344:74–78. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOKETSU M., MARUYAMA T., YAMAMOTO H., KONDO K., AISHITA H. Development of non-prostanoid EP3 selective agonist; ONO-AP-324. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1996;55:S142. [Google Scholar]

- MASTERS S.B., MILLER R.T., CHI M.H., CHANG F.-H., BEIDERMAN B., LOPEZ N.G., BOURNE H.R. Mutations in the GTP-binding site of Gsα alter stimulation of adenylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:15467–15474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEANWELL N.A., ROMINE J.L., SEILER S.M. Non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics. Drugs of the Future. 1994;19:361–385. [Google Scholar]

- MEGSON A.C., DICKENSON J.M., TOWNSEND-NICHOLSON A., HILL S.J. Synergy between the inositol phosphate responses to transfected human adenosine A1-receptors and constitutive P2-purinoceptors in CHO-K1 cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:1415–1424. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAMBA T., OIDA H., SUGIMOTO Y., KAKIZUKA A., NEGISHI M., ICHIKAWA A., NARUMIYA S. cDNA cloning of a mouse prostacyclin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:9986–9992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKA M., NEGISHI M., NISHIGAKI N., ICHIKAWA A. Two types of prostacyclin receptor coupling to stimulation of adenylate cyclase and phophatidylinositol hydrolysis in a cultured mast cell line, BNu-2c13 cells. Cell Signal. 1993;5:643–650. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(93)90059-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARKINSON P.A., PARFENOVA H., LEFFLER C.W. Phospholipase C activation by prostacyclin receptor agonist in cerebral microvascular smooth muscle cells. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 2000;223:53–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEILER S., BRASSARD C.L., ARNOLD A.J., MEANWELL N.A., FLEMING J.S., KEELY S.L., JR Octimibate inhibition of platelet aggregation: stimulation of adenylate cyclase through prostacyclin receptor activation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;255:1021–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH J.A.M., AMAGASU S.M., EGLEN R.M., HUNTER J.C., BLEY K.R. Characterization of prostanoid receptor-evoked responses in rat sensory neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:513–523. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH R.J., SAM L.M., JUSTEN J.M., BUNDY G.L., BALA G.A., BLEASDALE J.E. Receptor-coupled signal transduction in human polymorphonuclear neutrophils: effects of a novel inhibitor of phospholipase C-dependent processes on cell responsiveness. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 1990;253:688–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMYTH E.M., HONG LI W., FITZGERALD G.A. Phosphorylation of the prostacyclin receptor during homologous desensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:23358–23266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMYTH E.M., NESTOR P.V., FITZGERALD G.A. Agonist-dependent phosphorylation of an epitope-tagged human prostacyclin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:33698–33704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TORISU K., TAKAHASHI K., NAGAO Y., OHUCHIDA S., KONDO K., HAMANAKA N., KAWAMURA M. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of naphthoxyacetic acid derivatives as PGI2 agonists. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1996;55:S78. [Google Scholar]

- VASSAUX G., GAILLARD D., AIHAUD G., NÉGREL R. Prostacyclin is a specific effector of adipose cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:11092–11097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER E.M., BISPHAM J.R., HILL S.J. Nonselective effects of the putative phospholipase C inhibitor, U73122, on adenosine A1 receptor-mediated signal transduction events in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;56:1455–1462. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00256-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATANABE T., YATOMI Y., SUNAGO S., MIKI I., ISHII A., NAKAO A., HIGASHIHARA M., SEYAMA Y., OGURA M., SAITO H., KUROKAWA K., SHIMIZU T. Characterization of prostaglandin and thromboxane receptors expressed on a megakaryoblastic leukemia cell line, MEG-01s. Blood. 1991;78:2328–2336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WISE H. The inhibitory effects of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics on rat neutrophil function. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1996;54:351–360. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(96)90049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WISE H. Characterization of chimeric prostacyclin/prostaglandin D2 receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;386:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00725-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WISE H., JONES R.L. Prostacyclin and Its Receptors. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2000. pp. 1–310. [Google Scholar]

- WISE H., KAM Y.W., CHOW K.B.S. Prostacyclin receptor-independent effects of non-prostanoid prostacyclin mimetics. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;133:87P. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WISE H., QIAN Y., JONES R.L. A study of prostacyclin mimetics distinguishes neuronal from neutrophil IP receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;278:265–269. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00173-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]