Abstract

Locus coeruleus neurons in adult rats express binding sites and mRNA for α1-adrenoceptors even though the depolarizing effect of α1-adrenoceptor agonists on neonatal neurons disappears during development.

In this study intracellular microelectrodes were used to record from locus coeruleus neurons in brain slices of adult rats and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT – PCR) was used to investigate the mRNA expression of α1- and α2-adrenoceptors in juvenile and adult rats.

The α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine had no effect on the membrane conductance of locus coeruleus neurons (Vhold −60 mV) but decreased the G protein coupled, inward rectifier potassium (GIRK) conductance induced by α2-adrenoceptor or μ-opioid agonists. The GIRK conductance induced by noradrenaline was increased in amplitude when α1-adrenoceptors were blocked with prazosin.

RT – PCR of total cellular RNA isolated from microdissected locus coeruleus tissue demonstrated strong mRNA expression of α1a-, α1b- and α1d-adrenoceptors in both juvenile and adult rats. However, only mRNA transcripts for the α1b-adrenoceptors were consistently detected in cytoplasmic samples taken from single locus coeruleus neurons of juvenile rats, suggesting that this subtype may be responsible for the physiological effects seen in juvenile rats.

Juvenile and adult locus coeruleus tissue expressed mRNA for the α2a- and α2c-adrenoceptors while the α2b-adrenoceptor was only weakly expressed in juveniles and was not detected in adults.

The results of this study show that α1-adrenoceptors expressed in adult locus coeruleus neurons function to suppress the GIRK conductance that is activated by μ-opioid and α2-adrenoceptors.

Keywords: α1-adrenoceptors, α2-adrenoceptors, μ-opioid receptors, GIRK conductance, locus coeruleus, gene expression

Introduction

The function of α1-adrenoceptors expressed by noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons changes during development. In developing rats, locus coeruleus neurons are excited by local (iontophoretic) applications of noradrenaline that are too low to activate inhibitory α2-adrenoceptors (Nakamura et al., 1988). This effect of noradrenaline is mimicked by the α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine, and the actions of both agonists are blocked by the selective α1-adrenoceptor antagonist HEAT (2-beta[4-hydroxyphenyethlaminomethy]tetralone). Both excitatory and inhibitory effects on cell firing also occur when endogenous noradrenaline is released following electrical stimulation of the dorsal noradrenergic bundle. The α1-adrenoceptors are located directly on noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons, as both noradrenaline and phenylephrine depolarize these cells in brain slices prepared from immature mice or rats (Finlayson & Marshall 1984; 1986; Williams & Marshall, 1987). During maturation the excitatory effects of α1-adrenoceptors become progressively more difficult to detect and effectively disappear in adult rats (Williams & Marshall, 1987; Nakamura et al., 1988).

Despite the apparent loss of function, α1-adrenoceptors continue to be expressed in the adult locus coeruleus with autoradiographic binding detected using the α1-adrenoceptor antagonists, [3H]prazosin (Chamba et al., 1991) and [125I]HEAT (Jones et al., 1985). While in situ hybridization has localized mRNA for the α1a- and α1b-adrenoceptors in adult locus coeruleus neurons (Day et al., 1997), little is known of the expression of particular α1-adrenoceptor subtypes locus coeruleus neurons of juvenile rats. Notwithstanding the loss of excitatory effects of α1-adrenoceptor agonists in adults (Williams & Marshall, 1987; Nakamura et al., 1988), there is limited evidence that these receptors continue to be functional in adults. Small increases in the frequency of spontaneous action potential firing have been produced with praxosin in brain slices. These were attributed to block of α1-adrenoceptors activated by endogenous noradrenaline release but no mechanism was identified that could explain such an effect (Ivanov & Aston-Jones, 1995). It has also been reported that α1-adrenoceptors can increase noradrenaline release from synaptosomes prepared from locus coeruleus terminals in cortex and hippocampus (Pastor et al., 1996).

In the report by Williams & Marshall (1987) it is noted as an unpublished observation that in adult locus coeruleus neurons, prazosin can increase the outward current produced by noradrenaline. This current is produced by GIRK channels that are opened by α2-adrenoceptor stimulation (Egan et al., 1983; Williams et al., 1985). In this study we investigated whether α1-adrenoceptors in locus coeruleus neurons can function to modulate signalling pathways that open GIRK channels. We also used reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT – PCR) to determine which of the three cloned α1-adrenoceptor subtypes is present in locus coeruleus tissue of juvenile and adult rats, and in cytoplasmic samples from single juvenile locus coeruleus neurons.

Methods

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were used in this study for all of the experiments. Intracellular microelectrode recordings were made from rats that weighed 150 – 200 g and were more than 6 weeks old. Rats were sacrificed under halothane anaesthesia, and their brains quickly removed and immersed in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (mM): NaCl, 126, KCl, 2.5; NaH2PO2, 1.4; MgCl2, 1.2; CaCl2, 2.4; glucose, 11; NaHCO3, 25; and equilibrated with 95% O2 : 5% CO2. Up to three 300 μm thick brain slices containing the locus coeruleus were cut in the horizontal plane. These were placed in a holding chamber containing oxygenated ACSF (35°C) before being used for experiments. Intracellular microelectrode recordings were made from slices that were continuously superfused (1.5 ml min−1) with ACSF (35°C) in a chamber (1.5 ml volume) mounted under a stereo-dissecting microscope. The locus coeruleus was visualized using transillumination. Recordings were made with an Axoclamp 2A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.) and microelectrodes filled with 2 M KCl that had resistances of 28 – 40 MΩ. Membrane currents were recorded in discontinuous voltage-clamp mode during which the switching frequency (4 – 5.2 kHz) and capacitance compensation were adjusted by observing the headstage voltage response monitored on a separate oscilloscope. Recordings were digitized and stored on a computer using PClamp or Axotape software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.)

Analysis of data

Inhibition curves for phenylephrine were measured as reductions in the amplitude of outward currents produced by maximally effective concentrations of α2-adrenoceptor and opioid agonists. All currents were measured at a holding potential of −60 mV.

Concentration-response data from each neuron was fitted to a logistic function of the form:

|

in which E and [A] are the pharmacological effect and concentration of agonist respectively, M is the maximum response, k is the EC50 and n is the slope parameter. Curve fitting was performed using a simplex optimization algorithm implemented using Kaleidagraph software. Data means are given with s.e.means.

Ribonucleic acids isolation and RT – PCR

Total cellular RNAs were isolated from locus coeruleus of juvenile (10-day-old) and adult (60-day-old) rats, using a single-step protocol for RNA isolation (‘RNAzol B', Cinna/Biotecx, U.S.A.) Tissue from the locus coeruleus was microdissected from pontine slices (400 μm thick), homogenized in RNAzol B at room temperature and the homogenate separated into two phases. Total RNA was precipitated from the aqueous phase with isopropanol and the RNA pellet dissolved in water. Optical density readings were done to estimate the amount of total RNA before it was used in RT – PCR. Data were obtained from two separate RNA preparations of locus coeruleus tissue for each of the two age groups. To produce the cDNA pool for analysis of α-adrenoceptor gene expression in the locus coeruleus at the two ages, total RNA (3 μg) was individually reverse transcribed (RT) in a volume of 50 μl using the StrataScript kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. This cDNA pool served as a template for the PCRs using six sets of adrenergic receptor oligodeoxynucleotide primers. At least two separate RT reactions were done from each total RNA preparation for each of the two ages.

PCR was performed in a 20 μl reaction volume containing: 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9); 50 mM KCl; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 0.01% gelatin; 0.1% Triton X-100; 200 μM each dNTP (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); 24 pmol of each primer and 0.2 U of SuperTaq DNA Polymerase (P.H. Stehelin and Cie AG, Basel, Switzerland); and 2 μl of the appropriate RT. Individual samples were heat sealed and amplifications were performed in a capillary tube thermal cycler (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia) as follows: cycle 1 – denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 68°C (60°C for α1a primers) for 1 min, extension at 72°C for 1 min; cycle 2 – 30 at 94°C for 10 s, 68°C (60°C for α1a primers) for 10 s, 72°C for 50 s (30 s for α1a primers). The PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. The amount of PCR product amplified was subjectively assessed using a (0) to (+++) system where (0)=not detected; (+)=weakly detected; (++)=strongly detected; (+++)=very strongly detected (Vidovic & Hill, 1995; 1997; Phillips et al., 1996; 1997).

The sequences of each oligodeoxynucleotide primer for the α1- and α2-adrenoceptors used in PCR were designed from published sequences of rat α-adrenoceptor clones and have been published previously (Vidovic et al., 1994; Gould et al., 1995). The receptor nomenclature for α1-adrenoceptors recommended by Hieble et al. (1995) was used in the study, i.e., α1a (previously α1a/c), α1b and α1d (previously α1a or α1a/d).

Single cell reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

The somatic cytoplasm from single locus coeruleus neurons of juvenile rats was aspirated by application of negative pressure into a patch pipette. The flow of the cell contents into the pipette was monitored with the aid of a microscope. The pipette was then withdrawn from the cell and its contents expelled into a sterile microtube. Approximately 1 μl was usually obtained in the microtube. To this was added 4 μl of RT mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.) containing hexamer random primer (30 ng), 1× first strand buffer (mM) (Tris-HCl pH 9 50; KCl 70, MgCl2 3, dithiothreitol 10), 4 U of ribonuclease inhibitor, the 4 deoxyribonucleotides triphosphate (1 mM each) and 5 U of StrataScript Rnase H− reverse transcriptase. The resulting 5 μl sample was incubated at 42°C for 1 h followed by 1 h at 50°C. Single stranded cDNAs were stored at −20°C until used for PCR amplification.

Two rounds of PCR amplification were required to detect the fragments of cDNA corresponding to α1-adrenoceptors. The amplification conditions, including cycling parameters, for the first and second rounds were identical to those described above, except that the entire product of the RT reaction (5 μl) was used in the first amplification and 1 μl of the resulting cDNA product was used as a template for the second round of PCR of 30 cycles, with the same set of α1-adrenoceptor specific primers. The amplification of the three α1-adrenoceptors was thus carried out in three separate capillary tubes, each containing a subtype specific primer mixture and the cDNA from a different locus coeruleus neuron. Eight microlitres of the amplification reaction was run on a 2% agarose gel which was then stained with ethidium bromide.

To control for contamination, RT – PCR was tested on cytoplasm harvested from locus coeruleus neurons where the reverse transcriptase was omitted from the RT reaction and also where no starting RNA was included in the reactions.

Drugs used

Stock solutions of [D-Ala2, N-MePhe4,Gly-ol]enkephalin (DAMGO), [Met5]enkephalin, idazoxan HCl, noradrenaline HCl, phenylephrine HCl and prazosin HCl (Sigma-Aldrich, U.S.A.) were made in distilled water and stored at 4°C. All drugs were diluted with ACSF and applied by superfusion.

Results

α1-adrenoceptors suppress currents induced by α2-adrenoceptors in adult locus coeruleus neurons

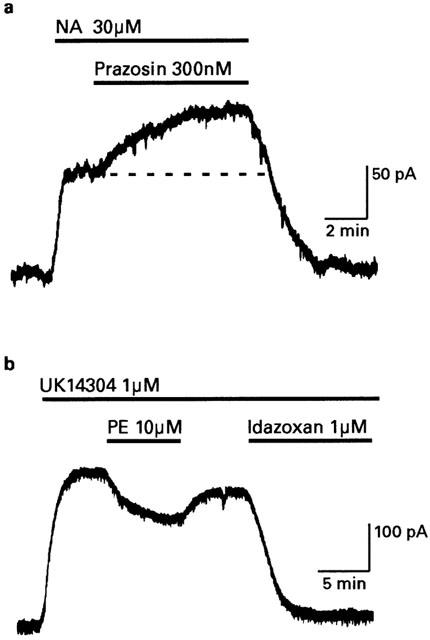

Noradrenaline induces outward currents in locus coeruleus neurons by activating α2-adrenoceptors that open GIRK channels (Egan et al., 1983; Williams et al., 1985). Figure 1a illustrates that outward currents induced by noradrenaline in the presence of cocaine (3 μM) were further increased in amplitude when the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin (300 nM) was also applied. In seven neurons, currents induced by noradrenaline (10 – 30 μM) were increased 44±4% by prazosin (108±34 pA to 157±27 pA).

Figure 1.

Alpha1-adrenoceptors suppress outward currents induced by α2-adrenoceptors. Intracellular microelectrode recordings obtained from rat locus coeruleus neurons voltage clamped at −60 mV. (a) After the outward current produced by 30 μM noradrenaline (NA) had reached steady-state, a further increase in amplitude was produced when α1-adrenoceptors were blocked with 300 nM prazosin. (b) The steady-state outward current produced by the α2-adrenoceptor agonist UK14304 was reduced in amplitude when the α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine (PE) was co-applied. The α2-agonist, idazoxan, blocked the effect of UK14304.

Figure 1b illustrates that when the outward current was induced by the selective α2-adrenoc eptor agonist UK14304 (1 μM) it was reduced in amplitude when the selective α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine (10 μM) was co-applied. This effect reversed completely when phenylephrine was washed out of the slice and the UK14304 current was terminated with the antagonist idazoxan (1 μM). Phenylephrine had no effect on the holding current (Vhold −60 mV) when applied alone (n=12). In seven neurons currents induced by UK14304 were reduced 45±4% by 100 μM phenylephrine (289±34 pA to 163±26 pA, Figure 2a). An IC50 value of 26 μM was estimated from the average fit of a logistic function to the concentration-effect data shown in Figure 2a.

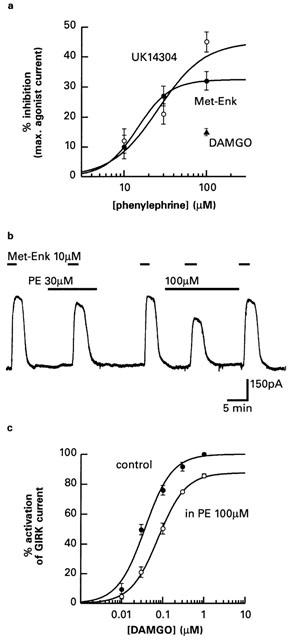

Figure 2.

Effects of phenylephrine on currents activated by α2-adrenoceptor and μ-opioid receptor agonists. (a) Concentration-effect curves for the inhibition by phenylephrine of α2-adrenoceptor currents activated by UK14304 (1 μM) and opioid currents activated by [Met5]enkephalin (10 μM). The curves are the fits of a logistic function (equation 1) to the data, which are means and s.e.means. The effect of a single concentration of phenylephrine (100 μM) on the maximal current activated by DAMGO (1 μM) is also shown. (b) The α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine (PE) caused concentration-dependent inhibition of outward currents activated by the μ-opioid agonist [Met5]enkephalin. (c) The concentration-effect curve for the selective μ-opioid agonist DAMGO was shifted to the right and had a reduced maximal response in response to 100 μM phenylephrine. The curves were derived from using average estimates of the parameters obtained by fitting a logistic function to data obtained in single neurons. Data are the means and s.e.means.

Opioid currents are also inhibited by α1-adrenoceptors in adult locus coeruleus neurons

GIRK channels are also opened in locus coeruleus neurons by activation of μ-opioid receptors (Miyake et al., 1989). Phenylephrine (100 μM) inhibited outward currents induced with the opioid peptide [Met5]enkephalin by 30±1.3% (373±35 pA to 262±27 pA, n=4, Figure 2b). An IC50 value of 15 μM for the inhibition of the [Met5]enkephalin current by phenylephrine was estimated from the average fit of a logistic function to the concentration-effect data shown in Figure 2a. Phenylephrine (100 μM) was less effective at inhibiting currents induced with DAMGO (1 μM), which is a selective μ-opioid receptor agonist that has a higher efficacy than [Met5]enkephalin in rat locus coeruleus neurons (Christie et al., 1987; Osborne & Williams, 1995). Figure 2c illustrates the effect of phenylephrine (100 μM) on the concentration-effect relationship for DAMGO. In three neurons, the maximum response was reduced to 87.6±2.34% (Paired t-test: P=0.033; 385±77 pA to 331±65 pA) and the pEC50 was shifted 2-fold to the right (7.44±0.06 to 7.12±0.02; Paired t-test: P=0.029) but there was no change in the Hill slope (1.42±0.06 and 1.34±0.02; Paired t-test: P=0.65).

In locus coeruleus neurons, prolonged applications of opioid agonists at supramaximal concentrations transiently desensitize μ-opioid receptors. This effect is specific or ‘homologous' for opioid receptors, and there is little cross-desensitization of GIRK currents induced by α2-adrenoceptors or somatostatin receptors (Harris & Williams, 1991; Fiorillo & Williams, 1996). In the present study μ-opioid receptors were desensitized by [Met5]enkephalin (30 μM applied for 10 min). Currents induced with [Met5]enkephalin desensitized more rapidly in phenylephrine (t1/2 reduced from 158±10 s to 125±9.6 s, n=3; Paired t-test: P=0.015) but there was no change in the amount of desensitization produced over a 5 min period (34±2.8% to 40±2.1%; Paired t-test: P=0.11).

Expression of mRNA for α1- and α2-adrenoceptors in juvenile and adult locus coeruleus

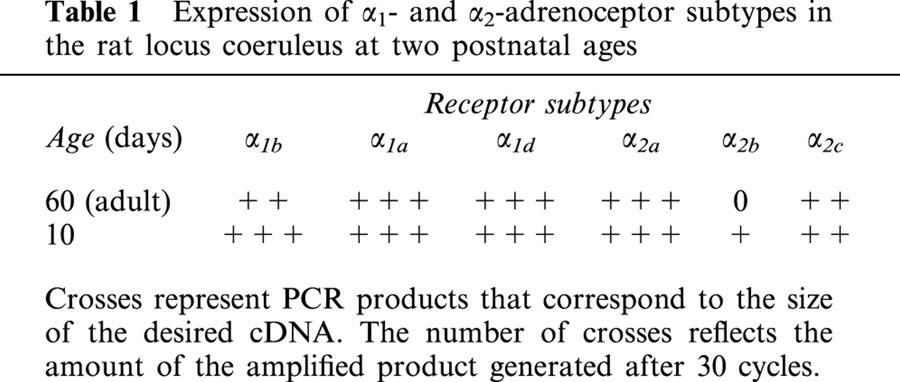

Expression of mRNAs encoding six α-adrenoceptors was studied in locus coeruleus tissue samples microdissected from juvenile rats on postnatal day 10, and adult rats on postnatal day 60. As shown by the data summarized in Table 1 all three α1-adrenoceptor mRNA transcripts were expressed at both ages but the α1b-receptor subtype was expressed more strongly during early development. Similar levels of messenger RNA expression of the α2a and α2c were detected for the two ages but the α2b-receptor subtype was expressed transiently as it was expressed at low levels during early development and not detected in the adult locus coeruleus. Examples of the α1- and α2-adrenoceptor expression in the adult locus coeruleus can be seen in Figure 3.

Table 1.

Expression of α1- and α2-adrenoceptor subtypes in the rat locus coeruleus at two postnatal ages

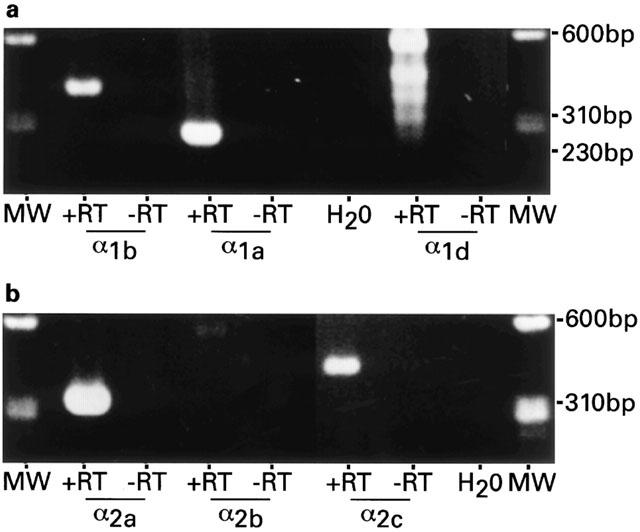

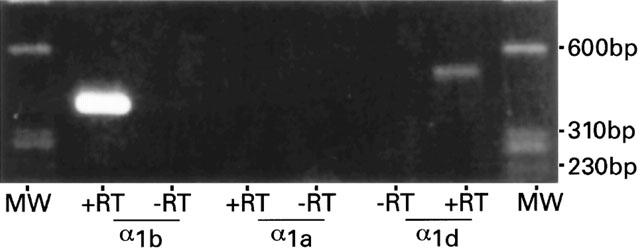

Figure 3.

α1- and α2-adrenoceptor mRNA expression in the adult locus coeruleus. (a) Agarose gel electrophoresis of 8 μl of PCR product of α1b- and α1d-adrenoceptor subtypes. A band of 405 bp (α1b+RT) represents α1b. Likewise, mRNA expression for α1a- and α1d-adrenoceptors are confirmed by the presence of bands of 251 bp (α1a,+RT) and 517 bp (α1d,+RT; top band). (b) PCR products defined by the α2 subtype specific primers were amplified from the same cDNA pool as the three α1-receptors. PCR product of 312 bp (α2a,+RT) represents α2a and 425 bp (α2c,+RT) represents α2c, while the predicted 456 bp product defined by the α2b subtype specific primers was not amplified after 30 cycles (α2b,+RT). No PCR products were seen in the control experiments that contained no reverse transcriptase in the RT reaction (−RT), nor in the second control that did not contain RNA (H2O). DNA size markers, ΦX174/HaeIII (MW).

Messenger RNAs encoding the three α1-adrenoceptors were also analysed at the level of single cells from locus coeruleus of juvenile rats. The RT – PCR was performed on the cytoplasm of 30 neurons with one set of α1 primers per cell. Each primer pair was designed to specifically amplify the mRNA of α1a-, α1b- or α1d-adrenoceptors. cDNA from five of five locus coeruleus neurons was amplified with α1b primers. For each of these neurons, a single band (405 bp; Figure 4, lane 2) was detected, consistent with that obtained in Figure 3a (lane 2). Amplification using α1d primers was demonstrated in three out of five locus coeruleus neurons examined for α1d expression (517 bp; Figure 4, lane 7) while no amplified cDNA was detected for the α1a-adrenoceptor subtype in six neurons (Figure 4, lane 4). Cytoplasm harvested from 14 locus neurons were used as negative controls (i.e., reverse transcriptase was omitted from the RT reaction) and no amplification products were seen with any of the three α1 primer pairs (Figure 4, lanes 3, 5, 6).

Figure 4.

α1-adrenoceptor mRNA expression in single cells of juvenile rat locus coeruleus. Agarose gel electrophoresis of 8 μl of PCR product of adrenergic α1b-, α1a- and α1d-receptor subtypes. The cytoplasmic contents of five individual locus coeruleus neurons were examined for α1b expression and a representative band of 405 bp is shown (α1b,+RT). No PCR product was amplified from six locus coeruleus neurons after two rounds of PCR with α1a specific primers (α1a,+RT). Three out of five cells examined for α1d expression demonstrated the presence of α1d (517 bp, α1d,+RT). No PCR products were amplified from the mRNA harvested from 14 locus coeruleus neurons with any of the three α1-adrenoceptor primers when the RT enzyme was omitted from the RT reaction (−RT). DNA size markers, ΦX174/HaeIII (MW).

When RT – PCR was also performed on cytoplasm obtained from adult neurons, amplified cDNA was detected in only two of the 17 experimental samples. Single bands were obtained using α1b primers in one case and α1a primers in the other. No amplification products were seen with any of the three α1 primer pairs in six additional negative controls. Cytoplasmic samples were difficult to obtain from adult locus coeruleus as most surface neurons in the slices died and viable neurons were located at a depth where cytoplasm moving into the sampling pipette was difficult to resolve visually with the type of microscope used for our experiments.

Discussion

In this study we have shown for the first time that α1-adrenoceptors are functional in adult rat locus coeruleus neurons and when activated, these receptors suppress outward currents induced by α2-adrenoceptors or μ-opioid receptors. These currents are carried by GIRK potassium channels that are opened by activation of receptors which couple to pertussis-toxin sensitive G proteins (Gi/Go). In the locus coeruleus this includes the receptors for somatostatin and nociceptin as well as α2-adrenoceptors and μ-opioid receptors (Miyake et al., 1989; Connor et al., 1996; Grigg et al., 1996; Nakajima et al., 1996).

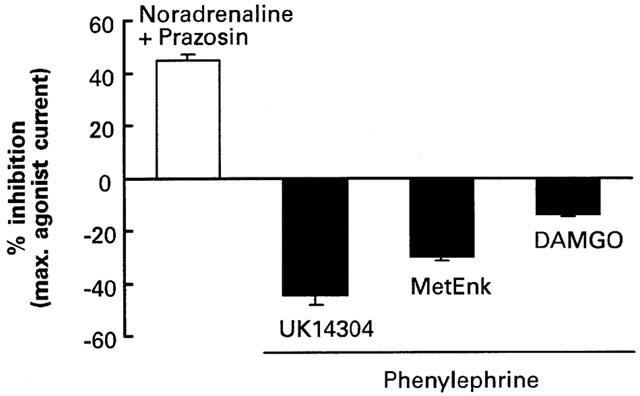

As shown by the summary plot in Figure 5, inhibition of GIRK currents by α1-adrenoceptors was inversely related to the efficacy of the test agonists. We have previously reported in locus coeruleus neurons that UK14304 is a partial agonist and does not maximally activate the GIRK current, whereas [Met5]enkephalin and DAMGO are full agonists that show a 9 fold difference in efficacy (Christie et al., 1987; Osborne & Williams, 1995). The variation in the inhibition of currents induced by different agonists suggests that α1-adrenoceptors do not simply reduce the number of open GIRK channels. This is because currents induced by opioid and α2-adrenoceptor agonists are reduced equally when GIRK channels are partially blocked with quinine, barium or TEA (North & Williams, 1985). Furthermore currents induced by opioid and somatostatin are also reduced equally by substance P, which has been shown to close GIRK channels in membrane patches obtained from isolated locus coeruleus neurons (Velimirovic et al., 1995). In the present study activation of α1-adrenoceptors not only reduced the maximum of the DAMGO concentration-effect relationship, but also shifted the midpoint 2 fold to the right. This is similar to the change in the DAMGO concentration-effect relationship that occurs when the opioid receptor reserve is reduced by irreversible opioid receptor antagonists or homologous μ-opioid receptor desensitization (Christie et al., 1987; Osborne & Williams, 1995). We suggest that α1-adrenoceptors do not close GIRK channels but either reduce the number of functional α2-adrenoceptors and μ-opioid receptors, or interfere with the G-protein mechanism coupling the receptors to the GIRK channels.

Figure 5.

Summary of α1-adrenoceptor modulation of GIRK currents induced by different agonists. Potassium currents induced by noradrenaline were potentiated by prazosin (300 nM), while potassium currents induced by UK14304 (1 μM), [Met5]enkephalin (10 μM) and DAMGO (1 μM) were inhibited by phenylephrine (100 μM). Changes are expressed as percentage of the currents induced by agonist alone. Data are means and s.e.means.

The rate at which desensitization developed in response to a high concentration of [Met5]enkephalin was increased by α1-adrenoceptors. In contrast, outward currents induced by α2-adrenoceptors normally do not desensitize to any significant extent (Harris & Williams, 1991), and this was not changed by α1-adrenoceptors. Desensitization of μ-opioid receptors in locus coeruleus can only be induced by supermaximal concentrations of opioid agonists. It is specific or ‘homologous' to μ-opioid receptors as there is no cross-desensitization of the current induced by α2-adrenoceptors (Harris & Williams, 1991). Our data suggested that the increase in the rate of homologous receptor desensitization could be unrelated to the heterologous inhibition of GIRK currents. We found that α1-adrenoceptors suppressed submaximal GIRK currents induced by low concentrations of DAMGO which do not cause receptor desensitization, and the effect was not specific to μ-opioid receptors. Muscarinic receptors can also increase the rate as well as the amount of μ-opioid receptor desensitization in locus coeruleus neurons without affecting α2-adrenoceptor desensitization (Fiorillo & Williams, 1996). However unlike α1-adrenoceptors, muscarinic receptors also depolarize locus coeruleus neurons directly by reducing the resting inward rectifier potassium current and increasing a non-selective cation current (Shen & North, 1992a, 1992b; Koyano et al., 1993; Velimirovic et al., 1995). This difference means that activation of α1-adrenoceptors will only affect the excitability of locus coeruleus neurons under conditions where the GIRK current is active.

In the present study, strong mRNA expression of all three cloned α1-adrenoceptor subtypes was detected in locus coeruleus tissue samples microdissected from juvenile and adult rats. While mRNA for the α1b-adrenoceptors showed a small relative decrease during maturation there were no changes in the other two subtypes with age. On the other hand, RT – PCR of cytoplasmic samples taken from single locus coeruleus neurons of juvenile rats detected only the α1b-adrenoceptors and α1d-adrenoceptors, suggesting that mRNA for the α1a-adrenoceptors detected in tissue samples is likely to be expressed in non-neuronal cells. The strong and consistent expression of the α1b-adrenoceptors in the juvenile neurons supports the contention that this receptor plays a prominent role in depolarizing juvenile neurons in response to phenylephrine. Unfortunately, we were unable to reliably detect amplified cDNA in cytoplasmic samples from locus coeruleus neurons in adult brain slices, although the expression of α1a- and α1b-adrenoceptors in two cells is in line with previous studies demonstrating these two subtypes in adult locus coeruleus neurons. Since α1a-adrenoceptors were not detected in juvenile neurons, this subtype is a likely candidate for the adult response.

Messenger RNA for the α2a- and α2c-adrenoceptors was strongly expressed in the locus coeruleus of both juvenile and adult rats, while expression of the α2b-adrenoceptor was only weak in juvenile rats and was absent in adult rats. These results correspond with in situ hybridization studies that report strong expression of the α2a-adrenoceptors in embryonic, neonatal and adult rat locus coeruleus (Winzer-Serhan et al., 1997a) and expression of the α2c-adrenoceptor at the mRNA and protein level by the end of the second postnatal week and into adulthood (Winzer-Serhan et al., 1997b). The lack of α2b-adrenoceptor expression in adult locus coeruleus is consistent with the restricted distribution of this subtype in the CNS (Winzer-Serhan & Leslie, 1997). In α2a-adrenoceptor knockout (α2a-D79N) mice (Lakhlani et al., 1997) α2-adrenoceptor agonists no longer reduce the firing rate of locus coeruleus neurons, which supports the contention that this receptor subtype is crucial to the effects of α2-adrenoceptor agonists described here.

The electrophysiological properties of locus coeruleus neurons change dramatically during postnatal maturation. In the newborn rat, strong electrotonic coupling between the neurons synchronize rhythmic membrane oscillations in neurons throughout the nucleus and neurons can be depolarized by α1-adrenoceptors as well as hyperpolarized by α2-adrenoceptors. Around the third postnatal week coupling is dramatically down-regulated and the depolarizing effect of adrenoceptor agonists progressively disappears. The present study has shown that, in the adult rat, α1-adrenoceptors become effective at suppressing receptor induced GIRK conductances. Although at present no physiological function can be attributed to this mechanism, two possibilities stand out. Firstly, α1-adrenoceptors could function as autoreceptors that act in opposition to α2-autoreceptors that slow neuronal firing in the locus coeruleus when noradrenaline is released from dendrites. Under these circumstances α1-adrenoceptors could limit the effect of α2-adrenoceptors and prevent a complete loss of spontaneous firing. The second possibility is that locus coeruleus α1-adrenoceptors are activated by the substantial input from adrenaline-containing neurons in the paragigantocellular nucleus of the medulla (Pieribone et al., 1988; Pieribone & Aston-Jones, 1991).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Gina Cleva and Mr M. Newhouse for excellent technical help. Supported by The Medical Foundation of The University of Sydney.

Abbreviations

- DAMGO

[D-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol]enkephalin

- GIRK

G protein coupled, inward rectifier potassium (channels/conductance)

- HEAT

(2-beta[4-hydroxyphenyethlaminomethy]tetralone)

- RT – PCR

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

References

- CHAMBA G., WEISSMANN D., ROUSSET C., RENAUD B., PUJOL J.F. Distribution of alpha-1 and alpha-2 binding sites in the rat locus coeruleus. Brain Res. Bull. 1991;26:185–193. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHRISTIE M.J., WILLIAMS J.T., NORTH R.A. Cellular mechanisms of opioid tolerance: studies in single brain neurons. Mol. Pharmacol. 1987;32:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONNOR H., VAUGHAN C.W., CHIENG B., &, CHRISTIE M.J. Nociceptin receptor coupling to a potassium conductance in rat locus coeruleus neurones in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;19:1614–1618. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAY H.E., CAMPEAU S., WATSON S.J., AKIL H. Distribution of alpha 1a-, alpha 1b- and alpha 1d-adrenergic receptor mRNA in the rat brain and spinal cord. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 1997;13:115–139. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(97)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EGAN T.M., HENDERSON G., NORTH R.A., WILLIAMS J.T. Noradrenaline-mediated synaptic inhibition in rat locus coeruleus neurons. J. Physiol. Lond. 1983;345:477–488. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIORILLO C.D., WILLIAMS J.T. Opioid desensitization: interactions with G-protein-coupled receptors in the locus coeruleus. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:1479–1485. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FINLAYSON P.G., MARSHALL K.C. Hyperpolarizing and age-dependent depolarizing responses of cultured locus coeruleus neurons to noradrenaline. Brain Res. 1984;317:167–175. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FINLAYSON P.G., MARSHALL K.C. Locus coeruleus neurons in culture have a developmentally transient alpha 1 adrenergic response. Brain Res. 1986;390:292–295. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(86)80238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOULD D.J., VIDOVIC M., HILL C.E. Cross talk between receptors mediating contraction and relaxation in the arterioles but not the dilator of the rat iris. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:828–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIGG J., KOZASA T., NAKAJIMA Y., NAKAJIMA S. Single-channel properties of the G-protein-coupled inward rectifier potassium channel in brain neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1996;75:318–328. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.1.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRIS G.C., WILLIAMS J.T. Transient homologous μ-opioid receptor desensitization in rat locus coeruleus neurons. J. Neurosci. 1991;11:2574–2581. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-08-02574.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIEBLE J.P., BYLUND D.B., CLARKE D.E., EIKENBURG D.C., LANGER S.Z., LEFKOWITZ R.J., MINNEMAN K.P., RUFFOLO R.J. International Union of Pharmacology. X. Recommendation for nomenclature of alpha 1-adrenoceptors: consensus update. Pharmacol. Rev. 1995;47:267–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IVANOV A., ASTON-JONES G. Extranuclear dendrites of locus coeruleus neurons - activation by glutamate and modulation of activity of activity by alpha adrenoceptors. J. Neurophys. 1995;74:2427–2436. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.6.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES L.S., GAUGER L.L., DAVIS J.N. Anatomy of brain alpha 1-adrenergic receptors: in vitro autoradiography with [125I]heat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1985;231:190–208. doi: 10.1002/cne.902310207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOYANO K., VELIMIROVIC B.M., GRIGG J.J., NAKAJIMA S., NAKAJIMA Y. Two signal transduction mechanisms of substance P-induced depolarization in locus coeruleus neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1993;5:1189–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAKHLANI P.P., MACMILLAN L.B., GUO T.Z., MCCOOL B.A., LOVINGER D.M., MAZE M., LIMBIRD L.E. Substitution of a mutant alpha2a-adrenergic receptor via ‘hit and run' gene targeting reveals the role of this subtype in sedative, analgesic, and anesthetic-sparing responses in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:9950–9955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYAKE M., CHRISTIE M.J., NORTH R.A. Single potassium channels opened by opioids in rat locus ceruleus neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1989;86:3419–3422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAJIMA Y., NAKAJIMA S., KOZASA T. Activation of G protein-coupled inward rectifier K+ channels in brain neurons requires association of G protein beta gamma subunits with cell membrane. FEBS Lett. 1996;390:217–220. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00661-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMURA S., SAKAGUCHI T., KIMURA F., AOKI F. The role of alpha 1-adrenoceptor-mediated collateral excitation in the regulation of the electrical activity of locus coeruleus neurons. Neuroscience. 1988;27:921–929. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90195-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORTH R.A., WILLIAMS J.T. On the potassium conductance increased by opioids in rat locus coeruleus neurones. J. Physiol. Lond. 1985;364:265–280. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSBORNE P.B., WILLIAMS J.T. Characterization of acute homologous desensitization of μ-opioid receptor-induced currents in locus coeruleus neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:925–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PASTOR C., BADIA A., SABRIA J. Possible involvement of alpha 1-adrenoceptors in the modulation of [3H]noradrenaline release in rat brain cortical and hippocampal synaptosomes. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;216:187–190. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)13029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PHILLIPS J., VODOVIC M., HILL C.E. Alpha-adrenergic, neurokinin and muscarinic receptors in rat mesenteric artery; an mRNA study during postnatal development. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1996;92:235–246. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(96)01841-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PHILLIPS J., VIDOVIC M., HILL C.E. Variation of alpha adrenergic, neurokinin and muscarinic receptors amongst four arteries of the rat. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1997;62:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(96)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIERIBONE V.A., ASTON-JONES J.G. Adrenergic innervation of the rat nucleus locus coeruleus arises predominantly from the C1 adrenergic cell group in the rostral medulla. Neuroscience. 1991;41:525–542. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90346-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIERIBONE V.A., ASTON-JONES J.G., BOHN M.C. Adrenergic and non-adrenergic neurons in the C1 and C3 areas project to locus coeruleus: a fluorescent double labeling study. Neurosci. Lett. 1988;85:297–303. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90582-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEN K.Z., NORTH R.A. Muscarine increases cation conductance and decreases potassium conductance in rat locus coeruleus neurones. J. Physiol. Lond. 1992a;455:471–485. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEN K.Z., NORTH R.A. Substance P opens cation channels and closes potassium channels in rat locus coeruleus neurons. Neuroscience. 1992b;50:345–353. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90428-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VELIMIROVIC B.M., KOYANO K., NAKAJIMA S., NAKAJIMA Y. Opposing mechanisms of regulation of a G-protein-coupled inward rectifier K+ channel in rat brain neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:1590–1594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIDOVIC M., COHEN D., HILL C.E. Identification of alpha-2 adrenergic receptor gene expression in sympathetic neurones using polymerase chain reaction and in situ hybridization. Mol. Brain Res. 1994;22:49–56. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIDOVIC M., HILL C.E. Alpha adrenoceptor gene expression in the rat iris during development and maturity. Dev. Brain Res. 1995;89:309–313. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00118-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIDOVIC M., HILL C.E. Transient expression of α-1B adrenoceptor messenger ribonucleic acids in the rat superior cervical ganglion during postnatal development. Neuroscience. 1997;77:841–848. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS J.T., HENDERSON G., NORTH R.A. Characterization of α2-adrenoceptors which increase potassium conductance in rat locus coeruleus neurones. Neuroscience. 1985;14:95–101. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS J.T., MARSHALL K.C. Membrane properties and adrenergic responses in locus coeruleus neurons of young rats. J. Neurosci. 1987;7:3687–3694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-11-03687.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINZER-SERHAN U.H., LESLIE F.M. Alpha2B adrenoceptor mRNA expression during rat brain development. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1997;100:90–100. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINZER-SERHAN U.H., RAYMON H.K., BROIDE R.S., CHEN Y., LESLIE F.M. Expression of alpha 2 adrenoceptors during rat brain development–I. Alpha 2A messenger RNA expression. Neuroscience. 1997a;76:241–260. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00368-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINZER-SERHAN U.H., RAYMON H.K., BROIDE R.S., CHEN Y., LESLIE F.M. Expression of alpha 2 adrenoceptors during rat brain development–II. Alpha 2C messenger RNA expression and [3H]rauwolscine binding. Neuroscience. 1997b;76:261–272. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]