Abstract

In a previous study, we showed that magnolol, a potent antioxidant derived from a Chinese herb, attenuates monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) expression and intimal hyperplasia in the balloon-injured aorta of cholesterol-fed rabbits. Expression of cell adhesion molecules by the arterial endothelium and the attachment of leukocytes to the endothelium may play a major role in atherosclerosis. In the present study, the effects of magnolol on the expression of endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecules and the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) in tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)-treated human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) were investigated.

Pretreatment of HAECs with magnolol (5 μM) significantly suppressed the TNF-α-induced expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) (64.8±1.9%), but had no effect on the expression of intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 and endothelial cell selectin.

Magnolol (5 and 10 μM) significantly reduced the binding of the human monocytic cell line, U937, to TNF-α-stimulated HAECs (58.4 and 56.4% inhibition, respectively). Gel shift assays using the 32P-labelled NF-κB consensus sequence as probe showed that magnolol pretreatment reduced the density of the shifted bands seen after TNF-α-induced activation. Immunoblot analysis and immunofluorescence staining of nuclear extracts demonstrated a 58% reduction in the amount of NF-κB p65 in the nuclei in magnolol-treated HAECs. Magnolol also attenuated intracellular H2O2 generation in both control and TNF-α treated HAECs.

Furthermore, in vivo, magnolol attenuates the intimal thickening and TNF-α and VCAM-1 protein expression seen in the thoracic aortas of cholesterol-fed rabbits.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that magnolol inhibits TNF-α-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 and thereby suppresses expression of VCAM-1, resulting in reduced adhesion of leukocytes. These results suggest that magnolol has anti-inflammatory properties and may play important roles in the prevention of atherosclerosis and inflammatory responses in vivo.

Keywords: Magnolol, atherosclerosis, endothelial cell, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin, NF-κB, hydrogen peroxide

Introduction

Magnolia officinalis, a Chinese medicinal herb, has long been used for the treatment of fever, headache, anxiety, diarrhoea, asthma, and stroke. Magnolol, a compound purified from this herb, has vascular smooth muscle relaxant activity (Teng et al., 1990), an antithrombotic effect (Teng et al., 1991), and anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects (Wang et al., 1992). A number of other pharmacological effects of magnolol have also been found, including inhibition of neutrophil adherence (Shen et al., 1998), prevention of ischaemic-reperfusion injury (Hong et al., 1996), and, most importantly, strong antioxidant activity (Chan et al., 1996; Chang et al., 1994; Teng et al., 1991).

Since magnolol inhibits acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase, which catalyzes cholesterol esterification and facilitates the accumulation of intracellular cholesterol, both of which are involved in the pathogenesis of atherogenesis, it can be considered as a cholesterol lowering agent for the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia and atherosclerosis (Kwon et al., 1997). More recently, it has been shown to effectively prevent neointimal hyperplasia in the balloon-injured aorta of cholesterol-fed rabbits (Chen et al., 2001b). We were therefore interested in understanding the underlying mechanism of action of magnolol in endothelial cells and determining whether it stimulates or blocks the expression of adhesion molecules.

The adhesion of circulating leukocytes to the vascular endothelium is a critical early event in the development of atherosclerosis (Joris et al., 1983; Faggiotto et al., 1984). This localized accumulation of leukocytes is mediated by endothelial expression of specific adhesion molecules, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and endothelial cell selectin (E-selectin) (Cybulsky & Gimbrone, 1991; Price & Loscalzo, 1999). Increased expression of adhesion molecules by ECs in human atherosclerotic lesions may lead to further recruitment of leukocytes to atherosclerotic sites (van der wal et al., 1992; O'brien et al., 1993). Regulation of adhesion molecule expression occurs at the transcriptional level and is mediated, at least in part, by the redox-sensitive transcription factor, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) (Collins et al., 1995). Inducers of NF-κB activation, such as TNF-α, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, or u.v. radiation, cause oxidative stress, suggesting that the induction of radical oxygen species (ROS) is a signal common to a wide variety of NF-κB-inducing conditions (Muller et al., 1997). Although these inducible molecules have received considerable attention, little is known about the effects of magnolol on adhesion molecule expression, and a better understanding of this might provide important insights into the prevention of atherogenesis.

Possible effects of magnolol on adhesion molecule expression could play a key role in the prevention or treatment of cardiovascular disorders. We therefore tested the ability of magnolol to modulate the expression of adhesion molecules and transcriptional factor NF-κB by human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs). We also attempted to identify the ROS involved in this degradation. In addition, we studied the effects of magnolol on the intimal thickening and adhesion molecule expression seen in cholesterol-fed rabbits. Our study shows that magnolol attenuates the expression of VCAM-1 both in vitro and in vivo, and that this effect is mediated by partial blockage of NF-κB expression. Magnolol also significantly inhibits adhesion of the human monocytic cell line, U937, to HAECs.

Methods

Materials

Human aortic endothelial cell (HAEC) growth medium (medium 200), low serum growth supplement (LSGS), trypsin/EDTA solution (TE), and trypsin neutralizer solution (TN) were obtained from Cascade Biologics Inc., U.S.A. RPMI-1640 medium, foetal bovine serum (FBS), and the antibiotic-antimycotic mixture were obtained from GIBCO BRL (U.S.A.) Magnolol was obtained from the Pharmaceutical Industry Technology and Development Center, Taiwan. 2′,7′ - bis(2 - carboxyethyl) - 5(6) - carboxyfluorescein acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF-AM) and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) were obtained from Molecular Probes, U.S.A. Mouse antibodies directed against human NF-κB p65 were obtained from BD Transduction Laboratories, U.S.A. Goat antibodies against human VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and E-selectin were obtained from R&D Systems, U.S.A.

Culture of HAECs

HAECs were obtained as cryopreserved tertiary cultures from Cascade Biologics (OR, U.S.A.) and were grown in culture flasks in endothelial cell growth medium supplemented with 2% FBS, 1 μg ml−1 of hydrocortisone, 10 ng ml−1 of human epidermal growth factor, 3 ng ml−1 of human fibroblast growth factor, 10 μg ml−1 of heparin, 100 units ml−1 of penicillin, 100 pg ml−1 of streptomycin, and 1.25 μg ml−1 of Fungizone. The cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air, 5% CO2 and used between passages 3 and 8. The purity of the cultures was verified by staining with monoclonal antibody against human von-Willebrand factor (vWF).

Cell viability assay using MTT

The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was used to measure cell viability (Welder, 1992). The principle of this assay is that mitochondrial dehydrogenase in viable cells reduces MTT to a blue formazan. Briefly, cells were grown in 96-well plates and incubated with various concentrations of magnolol for 24 h, then 100 μl of MTT (0.5 mg ml−1) was added to each well and incubation continued at 37°C for an additional 4 h. The medium was then carefully removed, so as not to disturb the formazan crystals formed. Dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO; 100 μl), which solubilizes the formazan crystals, was added to each well and the absorbance of the solubilized blue formazan read at 530 nm (reaction) and 690 nm (background) using a DIAS Microplate Reader (Dynex Technologies, U.S.A.) The reduction in optical density caused by cytokine and magnolol was used as a measurement of cell viability, normalized to cells incubated in control medium, which were considered 100% viable.

Cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (cell ELISA)

To measure cell-surface expression of adhesion molecules, HAECs in 96-well plates were pretreated for 18 h with the indicated concentrations of magnolol, then stimulated for 6 h at 37°C with 2 ng ml−1 of TNF-α in the continued presence of magnolol. Specific goat antibodies against human VCAM-1, ICAM-1, or E-selectin (0.5 μg ml−1 in HBSS containing 1% skim milk, R&D) were added for 30 min at room temperature to separate wells, then the wells were washed with HBSS containing 0.05% Tween-20, incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG (0.5 μg ml−1 in HBSS containing 1% skim milk), washed, and the bound antibody detected by incubating the plates in the dark for 15 min at room temperature with 100 μl of 3% o-phenylenediamine and 0.03% H2O2 in a mixture of 50 mM citrate buffer and 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The reaction was stopped by addition of 50 μl of 2 M H2SO4. Plates were read on an ELISA plate reader at 490 nm using rows stained only with second step antibody as blanks.

Western blot analysis

Cells were pretreated for 18 h at 37°C with 5 μM magnolol, then stimulated for 6 h at 37°C with 2 ng ml−1 of TNF-α in the continued presence of magnolol. They were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS), centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C at 1200×g, and lysed for 1 h at 4°C with lysis buffer (NaCl 0.5 M, Tris 50 mM, EDTA 1 mM, 0.05% SDS, 0.5% Triton X-100, PMSF 1 mM, pH 7.4. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 4000×g for 30 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations in the supernatants were measured using a Bio-Rad protein determination kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, U.S.A.) The supernatants were subjected to 8% SDS – PAGE, then transferred for 1 h at room temperature to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (NEN), which were then treated for 1 h at room temperature with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 2% skim milk and incubated separately for 1 h at room temperature with goat anti-human-VCAM-1, ICAM-1, or E-selectin antibodies. After washing, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG. Immunodetection was performed using Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (NEN) and exposure to Biomax MR film (Kodak).

Endothelial cell-leukocyte adhesion assay

HAECs (5×105) were distributed into 24-well plates and allowed to reach confluence. They were then incubated for 18 h at 37°C with growth medium supplemented with magnolol at the indicated concentrations, then 6 h at 37°C with 2 ng ml−1 of TNF-α in the continued presence of magnolol. U937 cells, originally derived from a human histiocytic lymphoma and obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, U.S.A.), grown in RPMI 1640 medium (M.A. Bioproducts, Walkersville, MD, U.S.A.) containing 5% FBS, and subcultured at a 1 : 5 ratio three times per week, were labelled for 1 h at 37°C with BCECF/AM (10 μM, Boehringer-Mannheim) in serum-free RPMI 1640 media, then washed with PBS to remove free dye and resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing 2% FBS. Labelled U937 cells (106) were added to each HAEC-containing well and incubation continued for 1 h. Non-adherent cells were removed by two gentle washes with PBS, then the number of bound U937 cells was determined by counting four different fields using a fluorescence microscope at ×400 magnification. Fields for counting adherent cells were randomly selected at a half-radius distance from the centre of the monolayers.

Nuclear extract preparation and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Nuclear protein extracts were prepared as previously described (Chen et al., 2001a). Briefly, after washing with PBS, the cells were scraped off the plates in 0.6 ml of ice-cold buffer A (N-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N′-(2-ethenesulphonic acid) (HEPES) 10 mM, pH 7.9, KCl 10 mM, dithiothreitol (DTT) 1 mM, phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF) 1 mM, MgCl2 1.5 mM, and 2 μg ml−1 each of aprotinin, pepstatin, and leupeptin). After centrifugation at 300×g for 10 min at 4°C, the cells were resuspended in buffer B (80 μl of 0.1% Triton X-100 in buffer A), left on ice for 10 min, then centrifuged at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4°C. The nuclear pellets were resuspended in 70 μl of ice-cold buffer C (HEPES 20 mM, pH 7.9, MgCl2 1.5 mM, NaCl 0.42 M, DTT 1 mM, EDTA 0.2 mM, PMSF 1 mM, 25% glycerol, and 2 μg ml−1 each of aprotinin, pepstatin, and leupeptin), then incubated for 30 min at 4°C, followed by centrifugation at 15,000×g for 30 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was stored at −70°C as the nuclear extract. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad method. The NF-κB probe used in the gel shift assay was a 31-mer synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotide (5′-ACAAGGGACTTTCCGCTGGGGACT-TTCCAGG-3′; 3′-TGTTCCCTGAAAGGCGACCCCTGA-AAGGTCC-5′) containing a direct repeat of the κB site. For the electrophoretic mobility shift assay, radiolabelled doubled-stranded DNA was made by end-labelling with γ-32P-adenosine-5′-triphosphate (ICN) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Boehringer-Mannheim). Unincorporated nucleotides were removed by gel filtration on a Sephadex G25 column (BM-Quick Spin columns DNA G25, Boehringer-Mannheim). The DNA-binding reaction was performed for 20 min at room temperature in a volume of 20 μl, which contained 2 μg of nuclear extract, 2 – 5×105 c.p.m. ng−1 of 32P-labelled NF-κB (∼1 ng), 10 μg of salmon sperm DNA (Sigma-Aldrich), and 15 μl of binding buffer (HEPES 20 mM, pH 7.9, 20% glycerol, KCl 0.1 M, EDTA 0.2 mM, PMSF 0.5 mM, DTT 0.5 mM, and 5 μg ml−1 of leupeptin). Nuclear extract-oligonucleotide mixtures were separated from unbound DNA probe by electrophoresis through a native 5% polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide/bisacrylamide 29 : 1) in 0.25×TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA buffer, pH 8.0). Gels were vacuum-dried and subjected to autoradiography. Films were scanned using a UMAX scanner.

NF-κB p65 expression

NF-κB p65 protein in nuclear extracts was measured using the method of Ji et al. (1998). A 20 μg sample of protein was separated on a 10% SDS – PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes, which were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C with primary mouse anti-human NF-κB p65 antibody followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (0.5 μg ml−1) for 1 h at 37°C. Bound antibody was detected using Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (NEN) and exposure to Biomax MR film (Kodak). To measure NF-κB expression in situ, confluent HAECs (controls or 18 h magnolol-treated cells) on slides were exposed to TNF-α (2 ng ml−1) for 30 min, then fixed in 4% paraformadehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 15 min at 4°C, washed with PBS, blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 5% BSA in PBS, then reacted for 1 h at room temperature with mouse anti-human NF-κB p65 antibody (1 : 500 dilution in PBS; Transduction). After washes, the slides were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, then viewed on a fluorescent microscope.

Detection of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production

The effect of magnolol on H2O2 production in HAECs was determined by a fluorometric assay using DCFH-DA as the probe (Wan et al., 1993). This method is based on the oxidation by H2O2 of nonfluorescent DCFH-DA to fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin (DCF). Confluent HAECs (104 cells well−1) in 48-well plates were pretreated for 18 h with various concentrations of magnolol. After removal of magnolol, the cells were washed with HBSS, then HBSS containing 10 μM DCFH-DA was added and incubation continued for 45 min at 37°C. The fluorescence intensity (relative fluorescence units) was measured at 485 nm excitation and 530 nm emission using a Fluorescence Microplate Reader. To determine the effects of magnolol on H2O2 generation under oxidative stress, TNF-α (2 ng ml−1) was added to the medium, then the fluorescence intensity was measured immediately and at 15 min intervals for 60 min. Cells were viewed using a fluorescence microscopy and photographed.

Animal care and experimental procedures

Twenty male New Zealand white rabbits (2.5 – 3.0 kg) were used. The experimental procedures and animal care and handling were conducted in conformance with the guidelines of the American Physiological Society. The protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan. After one week on a commercial rabbit chow diet, rabbits were randomly allocated to one of two groups; both groups received a 2% high cholesterol (HC) diet (Purina Mills Inc, U.S.A.), but one (controls) was given a daily intramuscular injection of vehicle (4×10−4 M propylene glycol in normal saline) while the other was given a daily intramuscular injection of magnolol (M; 1 μg kg−1 body wt). The dose of magnolol used was based on published work (Hong et al., 1996). Water was allowed ad libitum. Animals were bled periodically for the assessment of liver function and renal function. After 6 weeks on the diet, the rabbits were anaesthetized with the intravenous injection of 35 – 40 mg kg−1 sodium pentobarbital and were sacrificed. Thoracic aortas were gently dissected free of adhering tissues, rinsed with ice-cold PBS, immersion-fixed in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde, paraffin-embedded, and then cross-sectioned for morphometry and immunohistochemistry. To examine expression of vWF, TNF-α, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin protein, immunohistochemistry was performed on serial sections of the aorta. The arterial sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and washed with PBS, then non-specific binding was blocked by preincubation for 1 h at room temperature with PBS containing 5 mg ml−1 of bovine serum albumin. Sequential serial section were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with goat anti-human vWF, TNF-α, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, or E-selectin primary antibody (1 : 15 dilution in PBS, R&D systems, U.S.A.) The sections were then incubated with biotinylated conjugated horse anti-goat IgG for 1 h at room temperature and antigen-antibody complexes detected by incubation with avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase complex for 1.5 h at room temperature, followed by 0.5 mg ml−1 of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine/0.01% hydrogen peroxide in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.2, as chromogen (Vector Lab, U.S.A.) Negative controls were performed by omitting the primary antibodies. The whole intimal area for each arterial cross-section specimen was determined by computerized morphometric analysis (LV-2 image Analyzer, Winhow Instruments, Taipei, Taiwan). Semiquantification of antigen expression was evaluated under the light microscope at ×200 magnification. Each specimen was read by three investigators who were blinded as to the type of immuno-stain and they were asked to assign arbitrarily an immuno-score of 0=no, 1=weak, 2=moderate, 3=strong and 4=very strong staining. A score of 0 was given to areas where staining was absent or as weak as the same area on the control section without primary antibodies incubation. A score of 4 was given to the darkest staining intensity observed. When staining intensities ranged between 2 levels, for example 1 and 2, a score of 1.5 was assigned. To avoid inter-assay variability, all sections used for quantitation were from the same staining batch.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean. An ANOVA and subsequent post hoc Dunnetts' test were used to determine the statistical significance of magnolol treatment on TNF-α-treated HAECs in vitro studies. In addition, Student's t-test was employed to compare the neointimal areas and the expressions of adhesion molecules between magnolol-treated and magnolol-untreated groups in vivo studies. For all tests, values of P<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Toxicity of magnolol for HAECs

Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. Treatment of HAECs with 2 ng ml−1 of TNF-α for 6 h did not result in cytotoxicity (data not shown). After 24 h incubation with 1, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, or 60 μM magnolol, cell viability was, respectively, 90.7±2.0, 105.6±11.4, 107.3±8.3, 81.1±9.0, 57.6±7.6, 16.2±1.5, or 0±0% of control levels, the three highest concentrations causing a significant reduction in cell viability.

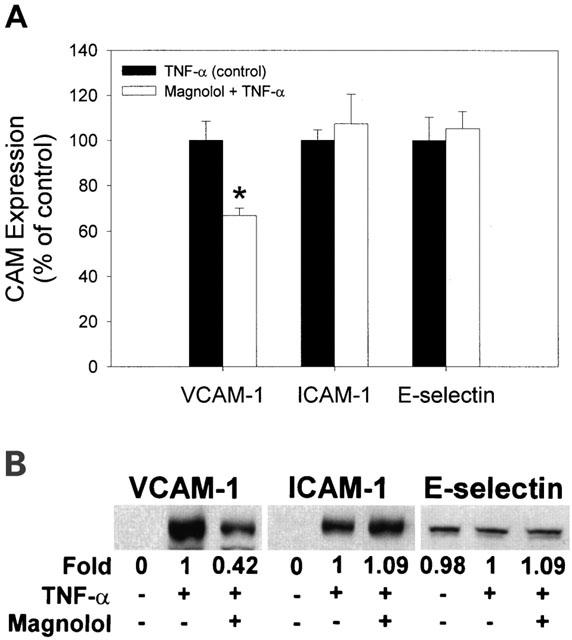

Magnolol decreases TNF-α induced cell surface expression of VCAM-1, but not of ICAM-1 or E-selectin, in HAECs

Since, in our previous study (Chen et al., 2001a), 6 h of treatment with 2 ng ml−1 of TNF-α was found to significantly up-regulate cell surface expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin, unless otherwise stated, these conditions were used throughout the present study. The effects of magnolol on TNF-α-induced VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin expression by HAECs were studied by pretreating HAECs for 18 h with 5 μM magnolol before addition of 2 ng ml−1 TNF-α; this resulted in reduced cell surface expression of VCAM-1 (64.8±1.9% expression compared to TNF-α-treated HAECs), but had no effect on cell surface expression of ICAM-1 and E-selectin (Figure 1A). The effects of adhesion molecule expression of magnolol for 24 h were similar to those of magnolol treatment for 18 h. The expression of VCAM-1 declined to 65.3±2.2% as compared to TNF-α-treated HAECs. Nevertheless, there was no significant difference in ICAM-1 and E-selectin between the magnolol-treated and magnolol-untreated groups.

Figure 1.

Effect of magnolol on adhesion molecule expression in HAECs. (A) Control cells or cells pretreated for 18 h with magnolol were treated for 6 h with TNF-α (2 ng ml−1), and expression of the adhesion molecules, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin, was measured by cell-ELISA. Data are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean of three experiments performed in triplicate. * P<0.05 compared to TNF-α-treated HAECs (controls). (B) Western blot analysis of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin protein levels in cultured HAECs. Three independent experiments gave similar results.

Cytoplasmic expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin in HAECs and the effects of TNF-α and magnolol

To study cytoplasmic expression of adhesion molecules, Western blot analysis of cell lysates was performed. As shown in Figure 1B, the amounts of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 were very low in control untreated HAECs, but, as expected, were enhanced by TNF-α treatment. Interestingly, E-selectin was found to be constitutively expressed in HAECs. Pretreatment with magnolol significantly inhibited the TNF-α-mediated induction of VCAM-1 expression, but had no effect on TNF-α-mediated induction of ICAM-1. TNF-α, with or without magnolol, had no effect on E-selectin expression.

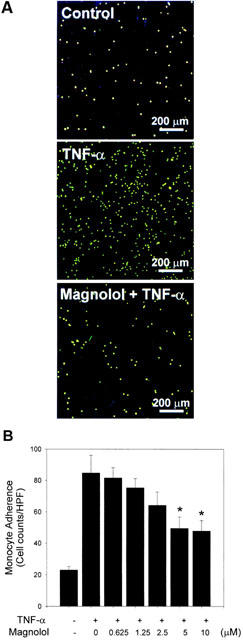

Magnolol inhibits adhesion of U937 cells to TNF-α-stimulated HAECs

To explore the effects of magnolol on endothelial cell-leukocyte interactions, we examined the adhesion of U937 cells to cytokine-activated HAECs under static conditions. Control confluent HAECs showed minimal binding to U937 cells, but adhesion was substantially increased when the HAECs were treated with TNF-α (Figure 2A). Pretreatment of confluent HAECs with magnolol (5 μM) prior to TNF-α treatment inhibited adhesion of U937 cells to the HAECs (Figure 2A). Pretreatment of HAEC with 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM magnolol reduced the number of U937 cells adhering to TNF-α-stimulated HAECs (number of U937 cells bound per high power field, 81.6±3.8, 75.3±3.4, 64.2±4.8, 49.5±4.2, 47.8±3.9, respectively; Figure 2B) compared to TNF-α-treated HAECs (84.8±6.5) (58.4 or 56.4% inhibition, respectively, at 5 or 10 μM magnolol).

Figure 2.

Effects of magnolol on the adhesion of U937 cells to TNF-α-stimulated HAECs. Control or HAEC cells pretreated for 18 h with magnolol were incubated with TNF-α (2 ng ml−1 for 6 h). (A) Representative fluorescent photomicrographs showing the effect of pretreatment with 5 μM magnolol on the TNF-α-induced adhesion of fluorescein-labelled U937 cells to HAECs. (B) Confluent HAECs were preincubated with the indicated concentration of magnolol, then incubated with TNF-α for 6 h. The data are representative of three experiments and the values are reported as the mean number of U937 cells bound per high power field (HPF)±s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared to TNF-α alone.

Magnolol attenuates activation of NF-κB expression and nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 in TNF-α-stimulated HAECs

Transcriptional regulation involving NF-κB activation has been implicated in the cytokine-induced expression of adhesion molecules. To examine whether magnolol inhibited NF-κB activation, we performed gel-shift assays using a 32P-labelled oligonucleotide containing the consensus NF-κB binding sequence. HAECs were preincubated at 37°C with 5 μM magnolol, then stimulated for 30 min at 37°C with TNF-α. Gel shift assays showed that TNF-α treatment resulted in the appearance of shifted bands (Figure 3A), which were specific for NF-κB binding, as they were undetectable when a 100 fold excess of unlabelled NF-κB oligonucleotide was included (data not shown). Pretreatment with magnolol reduced the density of the NF-κB shifted bands induced by TNF-α (Figure 3A). To determine whether NF-κB activation was involved in the pretranslational effects of magnolol on adhesion molecule expression, we also studied NF-κB p65 protein levels in the nuclei of TNF-α-treated HAECs by immunofluorescence and Western blots. TNF-α-stimulated HAECs showed marked NF-κB p65 staining in the nuclei, while magnolol-pretreated cells showed weaker nuclear NF-κB expression, but stronger staining in the cytoplasm (Figure 3B). Consistent with the in situ findings, Western blots (Figure 3C) showed that higher levels of NF-κB p65 protein were found in the nuclei of TNF-α-stimulated HAECs compared to control HAECs, and that magnolol pretreatment significantly reduced NF-κB expression (42% expression compared to TNF-α-treated cells).

Figure 3.

Effect of magnolol on NF-κB activation in TNF-α-stimulated HAECs. Control cells or cells were pretreated for 18 h with 5 μM magnolol, then stimulated with 2 ng ml−1 TNF-α for 30 min at 37°C. (A) EMSA, showing the effect of magnolol on TNF-α-stimulated HAECs. Nuclear extracts were prepared and tested for DNA binding activity of NF-κB. A representative result from three separate experiments is shown. (B) Immunofluorescent staining for NF-κB p65. (C) Western blotting and densitometry of NF-κB in nuclear extracts of HAECs. The results are representative of three separate experiments.

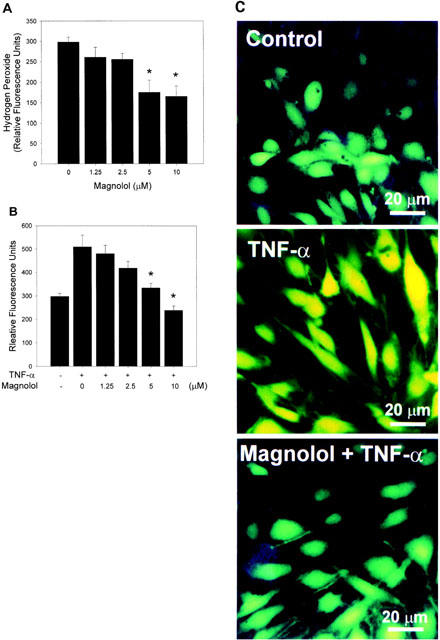

Magnolol inhibits H2O2 generation in control and TNF-α-treated HAECs

The effect of magnolol on H2O2 generation in control HAECs was studied. Unstimulated HAECs (no added cytokine) treated with magnolol (5 or 10 μM) showed decreased DCF fluorescence compared to non-magnolol-treated controls (Figure 4A). Under conditions of oxidative stress (TNF-α stimulation), magnolol pretreatment had no significant effect on the fluorescence measured at 15 min (data not shown), but, at all other time-points between 30 and 60 min, there was a similar concentration-dependent decrease in H2O2 generation (result for 60 min time-point shown in Figure 4B). As shown in Figure 4C, fluorescence density was low in control HAECs, but increased in cells treated with TNF-α, this effect being reduced by magnolol, presumably reflecting decreased intracellular H2O2 production.

Figure 4.

Effect of magnolol on intracellular H2O2 production in HAECs. (A) HAECs in 48-well plates were incubated for 18 h with 0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM magnolol, washed three times with HBSS to remove magnolol, then DCFH-DA was added to the wells. After 45 min incubation at 37°C, DCF fluorescence was measured. The data are the mean±s.e.mean of three independent experiments (with separate endothelial cells isolates) performed in triplicate. * P<0.05 compared to the magnolol-untreated control. (B) Effects of magnolol on H2O2 generation by TNF-α-stimulated HAECs. HAECs in 48-well plates were preincubated for 18 h with 0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM magnolol, then stimulated with 2 ng ml−1 of TNF-α for 1 h. Fluorescence readings were taken at 15 min intervals over a period of 60 min; only the 60 min result is shown. A significant difference (P<0.05) compared to control samples was seen after 60 min. (C). Fluorescent images of representative control, TNF-α-treated, and magnolol+TNF-α-treated HAECs.

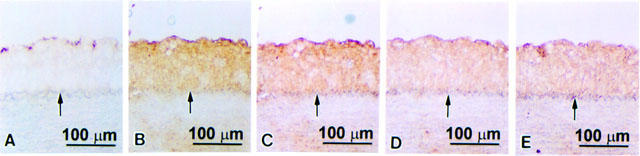

Magnolol attenuates TNF-α and VCAM-1 protein expression in the thoracic aorta of cholesterol-fed rabbits

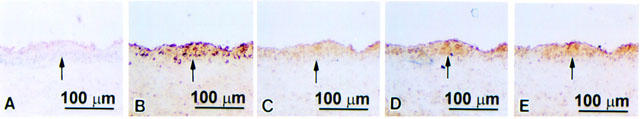

Over the experimental period, there was no difference in weight gain and final weight of the two groups of control or magnolol-treated rabbits fed a high cholesterol diet. There was also no significant differences in levels of glucose, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, blood urea nitrogen, or creatinine or in any other biochemical parameters. Morphometric analysis showed that the intimal area in the magnolol-treated group was significantly less than that in the control cholesterol-fed group ((199.19±22.68)×103 μm2 versus (759.06±45.14)×103 μm2). To study the effect of magnolol on the expression of TNF-α, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin in cholesterol-fed rabbits, immunohistochemical staining with antibodies against endothelial cells (anti-vWF antibody), TNF-α, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, or E-selectin was carried out on serial sections. In the control cholesterol-fed group, vWF-positive staining was seen on the luminal surface of the thoracic aorta (Figure 5A) and strong TNF-α staining (Figure 5B) and strong VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin staining (Figure 5C – E) was seen in the markedly thickened intima. In magnolol-treated animals, the intimal area was reduced (Figure 6), but vWF staining was present on the luminal surface (Figure 6A). Magnolol reduced TNF-α staining of the intima (Figure 6B) and VCAM-1 protein staining (Figure 6C), but had no effect on ICAM-1 and E-selectin expression (Figure 6D,E). Semiquantitative analysis showed that the expression of TNF-α and VCAM-1 in magnolol-treated group was significantly reduced from 3.77±0.13 and 3.93±0.10 to 2.63±0.28 and 1.13±0.30, respectively. In contrast, there was no significant difference in the expression of ICAM-1 and E-selectin between the magnolol-treated group and the control group (3.08±0.22 versus 2.80±0.22 and 3.15±0.26 versus 3.10±0.18, respectively).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical staining for vWF, TNF-α, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, or E-selectin protein expression in serial sections of thoracic aortas from cholesterol-fed rabbits. The lumen is uppermost in all sections. The internal elastic membrane is indicated by an arrow. Strongly positive vWF staining was seen on the luminal surface (A), and strong staining for TNF-α (B), VCAM-1 (C), ICAM-1 (D), and E-selectin (E) was seen in the markedly thickened intima.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemical staining for vWF, TNF-α, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, or E-selectin protein expression in serial sections of thoracic aortas from magnolol-treated cholesterol-fed rabbits. The lumen is uppermost in all sections. The internal elastic membrane is indicated by an arrow. Positive vWF staining was seen on the luminal surface (A). Weak staining for TNF-α (B) and VCAM-1(C) was seen in the less thickened intima. The intensity of ICAM-1 (D) and E-selectin (E) staining was similar to that in the control cholesterol-fed rabbits.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that magnolol treatment effectively blocked VCAM-1 expression both in vitro in TNF-α-stimulated HAECs and in vivo in the thoracic aorta of cholesterol-fed rabbits. In addition, it inhibited the binding of the human monocytic cell line, U937, to TNF-α-stimulated HAECs and decreased H2O2 levels in control and TNF-α-treated HAECs.

Magnolol was chosen for testing, as it has been used as a blood-quickening and stasis-dispelling agent in traditional Chinese medicine. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory actions are two of the pharmacological properties proposed to underlie its beneficial effects. Magnolol is 1000 times more potent than α-tocopherol in inhibiting lipid peroxidation in rat heart mitochondria (Lo et al., 1994) and 50,000 times more potent than glutathione, a well-known antioxidant; it also inhibits the generation of malondialdehyde, the end-product of lipid peroxidation, in sperm (Lin et al., 1995). In our previous study, we demonstrated that administration of magnolol effectively increased the resistance of plasma LDL from hyperlipidaemic rabbits to copper-induced oxidation in vitro and reduced neointimal formation in cholesterol-fed endothelium-denuded rabbits (Chen et al., 2001b). In addition, it reduces the number and total area of cytoplasmic lipid droplets in rat adrenal cells (Wang et al., 2000). In this study, we found that magnolol pretreatment significantly attenuated TNF-α-induced VCAM-1 expression in HAECs and that magnolol treatment also reduced VCAM-1 expression and resulted in less thickening of the intima in cholesterol-fed rabbits. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that endothelial dysfunction, such as disturbances in adhesion molecule expression, plays an important role in atherogenesis.

In our previous study, we demonstrated that TNF-α-treated endothelial cells show significant expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin (Chen et al., 2001a). The present study demonstrates that TNF-α-induced VCAM-1 expression was significantly reduced in HAECs pretreated with magnolol, whereas the expression of both ICAM-1 and E-selectin was unaffected. Consistent with our results, Marui et al. (1993) reported that, in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC) markedly attenuates TNF-α induced expression of VCAM-1, but not of ICAM-1 or E-selectin. Cominacini et al. (1997b) reported that probucol pretreatment of HUVECs significantly reduces the expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 induced by oxidized LDL (oxLDL), this effect being significantly greater for VCAM-1 than for ICAM-1. Probucol also substantially abrogates LPS-induced E-selectin expression in HUVECs, whereas ICAM-1 expression is not affected (Kaneko et al., 1996). The difference between the above results may be related to differences in cell types (HAECs and HUVECs) and the cytokines and inducers (TNF-α, oxLDL, and LPS) used. This is the first report in which HAECs have been used as a model to study the effect of magnolol on the expression of cell adhesion molecules.

In the case of receptor-mediated signals, such as TNF-α, the initial intracellular signals activated by the interaction of the ligand with the receptor are unlikely to be affected by magnolol. This implies that, while VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin share common regulatory signals immediately after receptor activation, the final regulatory signals are mediated by gene-specific signal transduction mechanisms. The precise molecular mechanism(s) why ICAM-1 and E-selectin gene expression escapes inhibition by magnolol treatment is an important unresolved question.

The magnolol-induced decrease in monocyte-EC adhesion has important implications in terms of atherogenic mechanisms, as well as in the treatment of atherosclerosis. In our previous study (Chen et al., 2001b), magnolol was shown to significantly reduce areas of atheroma, MCP-1 expression, and the area occupied by macrophages and smooth muscle cells in the aorta of cholesterol-fed endothelium-denuded rabbits. Atherosclerotic lesions result from the accumulation of foam cells of monocyte/macrophage origin within the arterial intima (Joris et al., 1983; Faggiotto et al., 1984). On the basis of the probable involvement of VCAM-1 in monocyte recruitment to early atherosclerotic lesions, our findings suggest an additional mechanism by which magnolol may be involved in preventing the progress of atherosclerosis.

A key component of TNF-α-inducible adhesion molecule expression is the redox-sensitive transcription factor, NF-κB (Lenardo & Baltimore, 1989). In the present study, we demonstrated that TNF-α activates NF-κB expression in endothelial cells, suggesting that the upregulation of VCAM-1 expression in response to TNF-α is mediated by this transcriptional factor. However, NF-κB is a ubiquitously expressed multiunit transcription factor that is activated by diverse signals, possibly via phosphorylation of the IκB subunit and its dissociation from the inactive cytoplasmic complex, followed by translocation of the active dimer, p50 and p65, to the nucleus (Ghosh & Baltimore, 1990). Antioxidants, such as NAC and other cysteine derivatives, inhibit the NF-κB-driven transcription of HIV-1 and HIV-1 viral replication (Mihm et al., 1991). In several immortalized cell lines, NF-κB is activated by diverse stimuli, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, LPS, and PIC, and inhibited by the antioxidants, PDTC and NAC (Schreck et al., 1992). Our study demonstrates a similar pattern of antioxidant (magnolol)-sensitive inactivation of VCAM-1 expression and NF-κB-like activity in HAECs.

While our studies support the notion that NF-κB factors are necessary to activate VCAM-1 gene expression in endothelial cells (Iademarco et al., 1992; Neish et al., 1992), they raise important questions about the role of NF-κB in E-selectin and ICAM-1 expression. Based on DNA transfection analysis of deleted promoter constructs of the E-selectin gene, a cis-acting promoter element, which contains a NF-κB consensus binding site, has been found to be required for IL-1β transcriptional activity (Ghersa et al., 1992). However, we found that magnolol did not inhibit E-selectin induction. Magnolol inhibition of NF-κB activation, but not of E-selectin expression, argues against NF-κB transcriptional factors being essential components in E-selectin gene activation. Similarly, these inducible factors may not be essential for activation of ICAM-1 expression, despite the presence of NF-κB consensus DNA binding sites on the ICAM-1 promoter (Degitz et al., 1991).

Several lines of evidence indicate that ROS are implicated in the activation of NF-κB and act as a common second messenger in various stimulus-specific pathways leading to NF-κB activation (Muller et al., 1997; Sen & Packer, 1996). For example, the potent antioxidants, PDTC and NAC, block NF-κB activation (Schreck et al., 1992; Weber et al., 1994), not only by H2O2 and ionizing radiation, but also by nonoxidizing stimuli (Weber et al., 1994). Cominacini et al. (1997a,1997b) reported that ox-LDL or TNF-α increases the expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells via NF-κB activation, and that the effect is inhibited by the presence of compounds with radical scavenging activity, and propose that NF-κB-mediated adhesion molecule expression follows activation by multiple radical-generating systems. The current study shows that magnolol can directly scavenge H2O2 and significantly decrease the amount of H2O2 generated by HAECs under steady state or oxidative stress conditions. Based on the results of the present study, we propose that the inhibitory effect of magnolol on VCAM-1 expression and NF-κB activation may be due to its antioxidant properties and that it acts by directly scavenging H2O2. In addition, reduction of lipid peroxidation by magnolol may also contribute to NF-κB inactivation. However, the critical steps in the signal transduction cascade of NF-κB activation by ROS remain to be determined.

In conclusion, this study provides the first evidence that magnolol reduces the expression of VCAM-1 adhesion molecules both in vitro and in vivo and also decreases leukocyte adhesion to HAECs. The present data show that magnolol inhibits TNF-α induced NF-κB activation and the resultant VCAM-1 expression via a pathway that involves ROS formation. Since monocyte recruitment into the vascular wall after their adhesion to endothelial cells is a crucial step in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, our study implies that antioxidants may have an, as yet, unexplored therapeutic potential in the prevention of atherosclerosis. Thus, magnolol may have an additional beneficial effect in multiple pathological events involving leukocyte adhesion, including inflammation and atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Science Council of Taiwan (grant NSC 89-2314-B010-028 and NSC 90-2320-B010-034). It was also funded by the Medical Research and Advancement Foundation in Memory of Dr Chi-Shuen Tsou. We would like to thank Dr Seu-Mei Wang and Mr Tang-Hsu Chao for technical assistance in manuscript preparation.

Abbreviations

- AP-1

activator protein-1

- DPPH radicals

1,1-diphenyl-2-picryhydrazyl radicals

- EC

endothelial cell

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- E-selectin

endothelial cell selectin

- HBSS

Hank's balanced salt solution

- HAEC

human aortic endothelial cell

- ICAM-1

intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- TNF-α

tumour necrosis factor-α

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

References

- CHAN P., CHENG J.T., TSAO C.W., NIU C.S., HONG C.Y. The in vitro antioxidant activity of trilinolein and other lipid-related natural substances as measured by enhanced chemiluminescence. Life Sci. 1996;59:2067–2073. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(96)00560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANG W.S., CHANG Y.H., LU F.J., CHIANG H.C. Inhibitory effects of phenolics on xanthine oxidase. Anticancer Res. 1994;14:501–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Y.H., LIN S.J., KU H.H., SHIAO M.S., LIN F.Y., CHEN J.W., CHEN Y.L. Salvianolic acid B attenuates VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression in TNF-alpha-treated human aortic endothelial cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2001a;82:512–521. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Y.L., LIN K.F., SHIAO M.S., CHEN Y.T., HONG C.Y., LIN S.J. Magnolol, a potent antioxidant from Magnolia officinalis, attenuates intimal thickening and MCP-1 expression after balloon injury of the aorta in cholesterol-fed rabbits. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2001b;96:353–363. doi: 10.1007/s003950170043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINS T., READ M.A., NEISH A.S., WHITLEY M.Z., THANOS D., MANIATIS T. Transcriptional regulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules: NF-kappa B and cytokine-inducible enhancers. FASEB J. 1995;9:899–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMINACINI L., GARBIN U., FRATTA P.A., PAULON T., DAVOLI A., CAMPAGNOLA M., MARCHI E., PASTORINO A.M., GAVIRAGHI G., LO C. Lacidipine inhibits the activation of the transcription factor NF-kappa B and the expression of adhesion molecules induced by pro-oxidant signals on endothelial cells. J. Hypertens. 1997a;15:1633–1640. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715120-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMINACINI L., GARBIN U., PASINI A.F., DAVOLI A., CAMPAGNOLA M., CONTESSI G.B., PASTORINO A.M., LO C.V. Antioxidants inhibit the expression of intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 induced by oxidized LDL on human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1997b;22:117–127. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CYBULSKY M.I., GIMBRONE M.A., JR Endothelial expression of a mononuclear leukocyte adhesion molecule during atherogenesis. Science. 1991;251:788–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1990440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEGITZ K., LI L.J., CAUGHMAN S.W. Cloning and characterization of the 5′-transcriptional regulatory region of the human intercellular adhesion molecule 1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:14024–14030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAGGIOTTO A., ROSS R., HARKER L. Studies of hypercholesterolemia in the nonhuman primate. I. Changes that lead to fatty streak formation. Arteriosclerosis. 1984;4:323–340. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.4.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHERSA P., HOOFT V.H., WHELAN J., DELAMARTER J.F. Labile proteins play a dual role in the control of endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule-1 (ELAM-1) gene regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:19226–19232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHOSH S., BALTIMORE D. Activation in vitro of NF-kappa B by phosphorylation of its inhibitor I kappa B. Nature. 1990;344:678–682. doi: 10.1038/344678a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HONG C.Y., HUANG S.S., TSAI S.K. Magnolol reduces infarct size and suppresses ventricular arrhythmia in rats subjected to coronary ligation. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Phyosiol. 1996;23:660–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IADEMARCO M.F., MCQUILLAN J.J., ROSEN G.D., DEAN D.C. Characterization of the promoter for vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:16323–16329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JI Y.S., XU Q., SCHMEDTJE J.F., JR Hypoxia induces high-mobility-group protein I (Y) and transcription of the cyclooxygenase-2 gene in human vascular endothelium. Circ. Res. 1998;83:295–304. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JORIS I., ZAND T., NUNNARI J.J., KROLIKOWSKI F.J., MAJNO G. Studies on the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. I. Adhesion and emigration of mononuclear cells in the aorta of hypercholesterolemic rats. Am. J. Pathol. 1983;113:341–358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KANEKO M., HAYASHI J., SAITO I., MIYASAKA N. Probucol downregulates E-selectin expression on cultured human vascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996;16:1047–1051. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.8.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KWON B.M., KIM M.K., LEE S.H., KIM J.A., LEE I.R., KIM Y.K., BOK S.H. Acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase inhibitors from Magnolia obovata. Planta Med. 1997;63:550–551. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LENARDO M.J., BALTIMORE D. NF-kappa B: a pleiotropic mediator of inducible and tissue-specific gene control. Cell. 1989;58:227–229. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90833-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN M.H., CHAO H.T., HONG C.Y. Magnolol protects human sperm motility against lipid peroxidation: a sperm head fixation method. Arch. Androl. 1995;34:151–156. doi: 10.3109/01485019508987843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LO Y.C., TENG C.M., CHEN C.F., CHEN C.C., HONG C.Y. Magnolol and honokiol isolated from Magnolia officinalis protect rat heart mitochondria against lipid peroxidation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994;47:549–553. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARUI N., OFFERMANN M.K., SWERLICK R., KUNSCH C., ROSEN C.A., AHMAD M., ALEXANDER R.W., MEDFORD R.M. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) gene transcription and expression are regulated through an antioxidant-sensitive mechanism in human vascular endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;92:1866–1874. doi: 10.1172/JCI116778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIHM S., ENNEN J., PESSARA U., KURTH R., DROGE W. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication and NF-kappa B activity by cysteine and cysteine derivatives. AIDS. 1991;5:497–503. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199105000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLER J.M., RUPEC R.A., BAEUERLE P.A. Study of gene regulation by NF-kappa B and AP-1 in response to reactive oxygen intermediates. Methods. 1997;11:301–312. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEISH A.S., WILLIAMS A.J., PALMER H.J., WHITLEY M.Z., COLLINS T. Functional analysis of the human vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 promoter. J. Exp. Med. 1992;176:1583–1593. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'BRIEN K.D., ALLEN M.D., MCDONALD T.O., CHAIT A., HARLAN J.M., FISHBEIN D., MCCARTY J., FERGUSON M., HUDKINS K., BENJAMIN C.D. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 is expressed in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques. Implications for the mode of progression of advanced coronary atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;92:945–951. doi: 10.1172/JCI116670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRICE D.T., LOSCALZO J. Cellular adhesion molecules and atherogenesis. Am. J. Med. 1999;107:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRECK R., MEIER B., MANNEL D.N., DROGE W., BAEUERLE P.A. Dithiocarbamates as potent inhibitors of nuclear factor kappa B activation in intact cells. J. Exp. Med. 1992;175:1181–1194. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.5.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEN C.K., PACKER L. Antioxidant and redox regulation of gene transcription. FASEB J. 1996;10:709–720. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.7.8635688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEN Y.C., SUNG Y.J., CHEN C.F. Magnolol inhibits Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18)-dependent neutrophil adhesion: relationship with its antioxidant effect. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;343:79–86. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01519-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TENG C.M., KO F.N., WANG J.P., LIN C.N., WU T.S., CHEN C.C., HUANG T.F. Antihaemostatic and antithrombotic effect of some antiplatelet agents isolated from Chinese herbs. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1991;43:667–669. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1991.tb03561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TENG C.M., YU S.M., CHEN C.C., HUANG Y.L., HUANG T.F. EDRF-release and Ca++-channel blockade by magnolol, an antiplatelet agent isolated from Chinese herb Magnolia officinalis, in rat thoracic aorta. Life. Sci. 1990;47:1153–1161. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90176-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DER WAL A.C., DAS P.K., TIGGES A.J., BECKER A.E. Adhesion molecules on the endothelium and mononuclear cells in human atherosclerotic lesions. Am. J. Pathol. 1992;141:1427–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAN C.P., MYUNG E., LAU B.H. An automated micro-fluorometric assay for monitoring oxidative burst activity of phagocytes. J. Immunol. Methods. 1993;159:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG J.P., HSU M.F., RAUNG S.L., CHEN C.C., KUO J.S., TENG C.M. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of magnolol. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1992;346:707–712. doi: 10.1007/BF00168746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG S.M., LEE L.J., HUANG Y.T., CHEN J.J., CHEN Y.L. Magnolol stimulates steroidogenesis in rat adrenal cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:1172–1178. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBER C., ERL W., PIETSCH A., STROBEL M., ZIEGLER-HEITBROCK H.W., WEBER P.C. Antioxidants inhibit monocyte adhesion by suppressing nuclear factor-kappa B mobilization and induction of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in endothelial cells stimulated to generate radicals. Arterioscler. Thromb. 1994;14:1665–1673. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.10.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WELDER A.A. A primary culture system of adult rat heart cells for the evaluation of cocaine toxicity. Toxicology. 1992;72:175–187. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(92)90111-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]