Abstract

The action of the β-lactam antibiotics, penicillin-G (PCG) and cefoselis (CFSL) on GABAA receptors (GABAA-R) was investigated using the two-electrode voltage clamp technique and Xenopus oocyte expressed murine GABAA-R.

Murine GABAA-Rs were expressed in Xenopus oocytes by injecting cRNA that encoded for each subunit (α1, β2, and γ2) and the effects of PCG and CFSL on the α1β2γ2s subunit receptors were examined using two-electrode voltage clamp. Using the α1β2γ2s GABAA-R, PCG and CFSL inhibited GABA-induced currents in a concentration-dependent manner, with IC50s of 557.1±125.4 and 185.0±26.6 μM, respectively. The inhibitory action of PCG on GABA-induced currents was non-competitive whereas that of CFSL was competitive.

Mutation of tyrosine to phenylalanine at position 256 in the β2 subunit (β2Y256F), which is reported to abolish the inhibitory effect of picrotoxin, drastically reduced the potency of PCG (IC50=28.4±1.42 mM) for the α1β2Y256Fγ2s receptor without changing the IC50 of CFSL (189±26.6 μM).

These electrophysiological data indicate that PCG and CFSL inhibit GABAA-R in a different manner, with PCG acting non-competitively and CFSL competitively. The mutational study indicates that PCG might act on an identical or nearby site to that of picrotoxin in the channel pore of the GABAA-R.

Keywords: Antibiotics, convulsion, picrotoxin, GABAA receptor, mutation, Xenopus oocytes, electrophysiology

Introduction

The GABAA-R plays a major role in inhibitory synaptic transmission within the central nervous system, and is a member of the ligand gated ion channel superfamily that includes glycine, acetylcholine and 5HT3 receptors. The GABAA-R is presumed to be a hetero-pentameric receptor, with molecular cloning techniques identifying 19 genes that encode for the subunits; these have been divided into seven classes (Barnard et al., 1998). The different combinations of GABAA-R subunits show varying levels of sensitivity to different drugs that include convulsants, sedatives, and general anaesthetics (Franks & Lieb, 1994; Sieghart, 1995; Barnard et al., 1998).

Antibiotics can have serious adverse effects on the central nervous system (CNS), producing confusion, twitching and convulsions (Wallace, 1997). Indeed, penicillins have been widely reported to induce convulsions in clinical situations, with this effect described as an example of antibiotic-induced neurotoxicity (Curtis et al., 1972; Weinstein et al., 1964). The effects of penicillins on the CNS have been thoroughly investigated both in vitro and in vivo, and appear to be mediated by suppression of inhibitory postsynaptic responses, predominantly at GABAA-R (Wallace, 1997). The fact that positive modulators of GABAA-R such as benzodiazepines and barbiturates can prevent or treat antibiotic-induced convulsions is consistent with this hypothesis (Barrons et al., 1992; Zeng et al., 1992; Wallace, 1997). In addition, antibiotics, including β-lactams such as penicillin and cephalosporines have been shown to inhibit GABA-induced currents in GABAA-R neurons (Twyman et al., 1992; Tsuda et al., 1994; Fujimoto et al., 1995), however, the molecular mechanism and site of action of these antibiotics at the GABAA-R remains obscure.

In examining GABAA-R function, care should be taken that a single mutation of tyrosine to phenylalanine at position 256 (β2Y256F) on the β2 subunit, when combined with wild type α and γ subunits, produces picrotoxin insensitivity (Gurley et al., 1995). This mutation is at a position predicted to be near the centre of the M2 region, which may be deep within the channel pore (Gurley et al., 1995). As studies indicate that penicillin may inhibit GABAA-R in a non-competitive manner like the ion channel blocker picrotoxin (Fujimoto et al., 1995; Twyman et al., 1992), examining the effects of penicillin on GABA-induced currents in this β2 mutant could reveal important information on the molecular site of action of penicillin. In the present study, the effects of PCG and a newly developed cephalosporin, CFSL (Mine et al., 1993a, 1993b), were investigated electrophysiologically using Xenopus oocytes expressed GABAA-R. The effects of PCG and CFSL on GABA-induced currents were studied using the α1β2γ2s and α1β2Y256Fγ2s subunit combinations to try and delineate the mechanism and site of action of these antibiotics.

Method

Xenopus oocyte electrophysiology

Preparation of cRNA for GABAA receptor subunits

Mouse cDNAs encoding for α1, β2, and γ2s GABAA-R subunits were kindly provided by Dr J Yang (University of Rochester, Rochester, U.S.A.) and Dr D Burt (University of Maryland, Baltimore, U.S.A.). All subunits were subcloned into the transcription vector, modified pBluescript (pBluescriptMXT), with the multiple cloning sites flanked by the β-globulin of Xenopus laevis in order to facilitate stable mRNA expression in oocytes. Plasmid cDNAs were purified using Qiagen's plasmid preparation kit (Qiagen, Chatworth, CA, U.S.A.), resuspended in sterile water and the cloned DNAs for the different subunits verified by restriction digest. Each cDNA template was linearized by restriction digest (Bgl I for β2 and β2Y256F; Pvu II for α1 and γ2s; Wako, Osaka, Japan). Capped mRNA was synthesized in vitro using Ambion's T3 RNA message machine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, U.S.A.) by following the manufacturer's recommended protocol. Stock mRNA's were stored in RNAse-free water at −80°C until use.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the β2 GABAA-R subunit

Site-directed mutagenesis of the β2 subunit (tyrosine to phenylalanine at position 256 of the amino acid sequence) was performed using Stratagene's QuikChange™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.) as per the manufacturer's protocol. The primers, 5′-CGGGTTGCATTAGGAATTTTCACTGTCCTAACAATGACC-3′ and 5′-GGTCATTGTTAGGACAGTGAAAATTCCTAATGCAACCCG-3′, were designed to incorporate the base sequence for phenylalanine instead of tyrosine at position 256 of the β2 subunit (the mis-match base pairs are underlined). The modified DNA sequence was verified using an automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Xenopus oocyte expression

In accordance with the study protocol approved by the Animal Research Committee of Osaka University Medical School, female frogs (Xenopus laevis) were anaesthetized with 1% tricaine (3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester), and surgery performed on ice under sterile conditions. Oocytes were harvested through a 5 mm laparotomy incision and frogs returned to the main tank after 2 days in isolation. Oocytes were manually defolliculated with forceps and treated with collagenase type 1A (1.5 mg ml−1) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, U.S.A.) for 30 min at room temperature in Ca2+-free ND96 (in mM: NaCl 96, KCl 2, HEPES 5, MgCl21). Healthy oocytes at stage 4 and 5 were selected and thoroughly rinsed with ND96. The desired combination of GABAA-R subunit cRNAs (0.1 mg ml−1) were mixed in equal ratios and 50–100 nl injected into oocytes using a Nanoject injector (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA, U.S.A.). Prior to electrophysiological experiments, oocytes were incubated for 24–72 h at 20°C in ND96 containing CaCl2(1.8 mM) and sodium pyruvate (2.5 mM).

Electrophysiology and drug application

Twenty-four to 72 h after mRNA injection, oocytes were placed in a small well and continuously perfused with frog Ringer's solution (in mM: NaCl 115, KCl 2.5, CaCl2 1.8, HEPES 10 at pH 7.4) at a rate of 10 ml min−1, using a perfusion system constructed of polyethylene tubing. Oocytes were impaled with two glass electrodes (2–5 MΩ) filled with 3 M KCl, and voltage clamped at −80 mV using a two-electrode voltage amplifier (Nihon Khoden, Tokyo, Japan). All electrophysiological experiments were performed at room temperature. Drug solutions were applied by switching three-way stopcocks from frog Ringer's solution to an otherwise identical solution containing the test drug at the desired concentration. Drugs were applied for at least 20 s to obtain peak currents, with GABA applications separated by varying intervals (1–10 min) depending upon the drug concentration used, avoiding receptor desensitization. To test for cumulative desensitization, a low concentration of GABA (5 μM) was applied following the response to higher concentrations. Currents were digitally recorded with AxoScope software (Axon Instruments, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.), running on an IBM personal computer. To construct concentration-response curves for GABA-induced currents and inhibition curves for antibiotics, observed peak amplitudes were normalized and plotted, and the data fitted to the following equation using Origin software (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA):

where I is the peak current at a given concentration of GABA, Imax is the maximum current and ED50 and n denote the concentration of GABA eliciting a half-maximal response and the Hill coefficient, respectively. For inhibition studies with PCG and CFSL the data were fitted to the following equation:

where I is the reduced current normalized with control data at a given concentration of antibiotic (AB) and IC50 denotes the concentration of antibiotics that produce half maximal currents.

Data analysis

All data are expressed as mean±s.e.mean and statistical analysis was performed using a 2-tailed t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with P<0.05 indicating significance.

Materials

PCG was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), and CFSL was synthesized by the Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). GABA, picrotoxin, bicuculline methiodide, baclofen and diazepam were from Wako (Osaka, Japan). In the electrophysiological experiments all drugs except diazepam were directly dissolved in frog Ringer's solution. Diazepam was dissolved in dimethylsulfphoxamide (DMSO) and then diluted with frog Ringer's solution to the desired concentration. The final concentration of DMSO never exceeded 0.05%, which itself had no effect. When PCG and CFSL were dissolved in frog Ringer's solution, the pH was re-adjusted to pH 7.4 with either 1 N HCl or NaOH, respectively.

Results

The effects of PCG and CFSL on α1β2γ2s GABAA receptors.

The application of GABA (1–300 μM) to recombinant α1β2γ2s GABAA-R expressed in oocytes, evoked inward currents in a concentration-dependent manner. Following a maximal response to GABA (300 μM), constant responses to 5 μM GABA were obtained between recordings to exclude receptor desensitization. In addition, ED20 GABA-induced currents were blocked by 10−5 M bicuculline methiodide and 10−5 M picrotoxin (data not shown; Gurley et al., 1995; Sieghart, 1995; Whiting et al., 1995). Expression of the γ2s subunit was confirmed by the potentiation of GABA-induced currents by 10−6 M diazepam using the α1β2γ2s receptor (data not shown; Verdoorn et al., 1990).

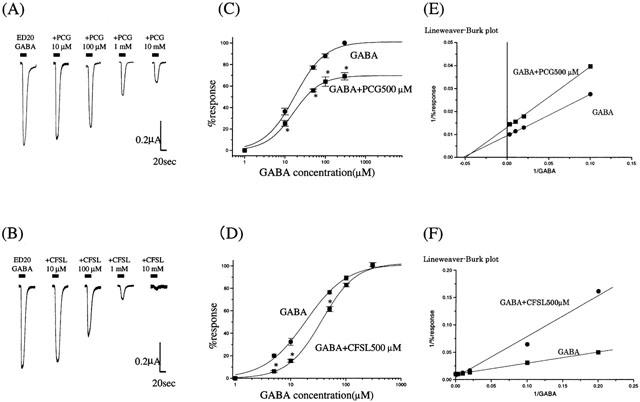

PCG and CFSL both inhibited GABA-induced currents in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1A,B). The application of either PCG (up to 1 M) or CFSL (up to 10 mM) to oocytes expressing the α1β2γ2s subunit GABAA-R (i.e., in the absence of GABA) did not generate any measurable currents (data not shown). Concentration-response curves for GABA in the absence and presence of PCG (500 μM) are shown in Figure 1C. The ED50 values for GABA from the concentration-response curves using the α1β2γ2s subunit receptor were 17.4±1.8 μM and 16.0±1.1 μM in the absence and presence of PCG, respectively. PCG suppressed the maximum response induced by GABA without changing the ED50 values, with the Lineweaver-Burk plots (Figure 1E) showing that inhibition by PCG was non-competitive. In contrast, CFSL shifted the dose response curve to the right without affecting the maximum response (Figure 1D). The ED50 value for GABA changed from 18.5±1.5 μM to 36.1±2.4 μM in the presence of CFSL (500 μM), with the Lineweaver-Burk plot (Figure 1F) showing that inhibition by CFSL was competitive.

Figure 1.

The effect of PCG and CFSL on GABA-induced currents on α1β2γ2s GABAA receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. (A,B) Co-application of GABA (EC20 : 5 μM) and PCG or CFSL resulted in a concentration dependent reduction in current amplitude. The bars over the current traces indicate the duration of drug application. (C–F) The effects of PCG (500 μM) and CFSL (500 μM) on the concentration-response curves of GABA. The ED50 values of GABA calculated from the dose-response curves using the α1β2γ2s subunit receptor were 17.4±1.8 and 16.0±1.1 μM, in the absence and presence of PCG respectively. PCG suppressed the maximum response induced by GABA without changing the ED50 values (C). In contrast, CFSL shifted the dose response curve to the right without affecting the maximum response. The ED50 value shifted from 18.5±1.5 μM to 36.1±2.4 μM in the presence of CFSL (D). Lineweaver-Burk plots of concentration-response curves show that inhibition by PCG was non-competitive (E) and that by CFSL was competitive (F). All the GABA responses were normalized to the peak current amplitude induced by 300 μM GABA alone. Each data point shows the average from five to seven oocytes, and is expressed as mean±s.e.mean, with asterisks indicating significant differences (P<0.05).

The effects of PCG and CFSL on mutant GABAA receptors (α1β2Y256Fγ2s).

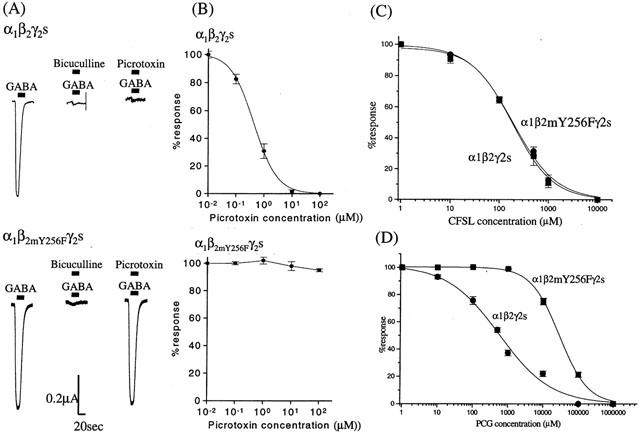

Application of GABA to oocytes expressing the α1β2Y256Fγ2s subunit receptor, resulted in currents with similar pharmacological properties to the native α1β2γ2s subunit receptor. The ED50 for GABA was 17.4±1.8 μM for the α1β2γ2s subunit receptor and 15.2±1.8 μM for the α1β2Y256Fγ2s subunit receptor. GABA-induced currents in both receptors were blocked by bicuculline, but the α1β2Y256Fγ2s subunit receptor was insensitive to picrotoxin as reported previously (Figure 2A,B; Gurley et al., 1995). The effects of PCG on the α1β2γ2s and α1β2Y256Fγ2s receptors were different (Figure 2D), with the β2Y256F subunit having a drastically reduced sensitivity to PCG. The IC50 of PCG for inhibition of GABA-induced currents was 557.1±125.4 μM for the α1β2γ2s subunit receptor, and 28.4±1.42 mM for the α1β2Y256Fγ2s subunit receptor. However, mutation of the β2Y256F subunit did not change the affinity of CFSL for α1β2γ2s receptors. Figure 2C shows concentration-dependent response curves for CFSL inhibition of GABA-induced currents at these receptors. The IC50 of CFSL for inhibition of GABA-induced currents was 185.0±26.6 μM for the α1β2γ2s subunit receptor, and 189.5±25.2 μM for the α1β2Y256Fγ2s subunit receptor. This indicates that the single mutation of the β2 subunit (β2Y256F) responsible for picrotoxin insensitivity can play a critical role in the modulation of PCG, but not CFSL on GABAA receptor function.

Figure 2.

The effects of the mutation (β2Y256F) on the α1β2γ2s subunit GABAA–R. (A) Bicuculline methiodide (10 μM) completely blocked GABA (ED20)-induced currents in both α1β2γ2s and α1β2Y256Fγ2s GABAA–R. Picrotoxin (10 μM) completely inhibited GABA-induced currents in the α1β2γ2s GABAA–R, but not in the α1β2Y256Fγ2s mutant GABAA–R. (B) Concentration-response curves for inhibition of GABA (ED20)-induced currents in α1β2γ2s and α1β2Y256Fγ2s GABAA–R by picrotoxin. Each data point represents the average from four to seven oocytes. The IC50s for picrotoxin at the α1β2γ2s receptor were 0.44±0.03 and 1.05±0.06 μM, respectively. Using the α1β2Y256Fγ2s subunit GABAA–R mutant, picrotoxin (0.01–100 μM) did not inhibit GABA-induced currents. (C,D) Inhibition of GABA (ED20)-induced currents in α1β2γ2s and α1β2Y256Fγ2s GABAA–R by PCG (C) and CFSL (D). Each data point represents the average from five to seven oocytes. IC50s values for CFSL at the α1β2γ2s and α1β2Y256Fγ2s subunit receptors were 185.0±26.6 μM and 189.5±25.2 μM, respectively. This mutation of the β2 subunit produced no significant alteration in the affinity CFSL. The IC50 of PCG for inhibition of GABA-induced currents in the α1β2γ2s subunit GABAA–R was 557.1±125.4 μM. In contrast, PCG had a markedly reduced affinity (IC50; 28.4±4.42 mM) for the α1β2Y256Fγ2s subunit receptor. The asterisks indicate significant difference (P<0.05).

Discussion

β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillins and cephalosporins are frequently used in the clinical treatment of various infectious diseases. Treatment with β-lactams can produce adverse effects such as convulsions, that are thought to be due to suppression of inhibitory postsynaptic responses, mainly mediated by GABA (Curtis et al., 1972; Wallace, 1997). However, the mechanism and site of action of antibiotics at GABAA-R remain obscure. Among the β-lactams, the penicillins have been relatively well investigated, with electrophysiological and biochemical studies on native neurons showing that penicillins appear to inhibit GABAA-R in a non-competitive and voltage-dependent manner (Pickles & Simmonds, 1980; Tsuda et al., 1994, Fujimoto et al., 1995). Studies using single channel recordings from neurons, indicate that open channel block of GABAA-R is the mechanism by which penicillin inhibits GABA-induced currents (Twyman et al., 1992). Other β-lactam antibiotics, such as the cephalosporins, which also have strong epileptogenic activities (Wallace, 1997), have been less well characterized. Previous binding studies indicated that some cephalosporins may act as competitive inhibitors of GABAA-R function (Hori et al., 1985), however there was no data on the effects of the newly developed cephalosporins, such as CFSL. These observations suggest that not all antibiotics inhibit GABAA-R by the same mechanism of action.

In the present study, the electrophysiological data from recombinant GABAA-R suggest that PCG and CFSL act differently at GABAA-R. We demonstrated using recombinant α1β2γ2s subunit GABAA-R that PCG and CFSL both inhibit GABA-induced currents in a concentration dependent manner with similar potency, but that their mode of actions were non-competitive and competitive, respectively. Furthermore, the results from the experiments using the mutated β subunits not only support the evidence for the different mechanism of actions of PCG and CFSL, but also give new information on the molecular site of action of PCG at the GABAA-R. Mutation of tyrosine to phenylalanine at position 256 on the β2 GABAA-R subunit was reported to abolish the inhibitory effect of the classical non-competitive inhibitor, picrotoxin, without general impairment of channel function (Gurley et al., 1995). This mutation of the β subunit also drastically reduced the ability of PCG to inhibit GABA-induced currents when co-expressed with the α and γ subunits but its effects were not completely abolished like that of picrotoxin (Gurley et al., 1995). This indicates that the binding site of PCG site on the GABAA-R might be in close proximity to that of picrotoxin. Further mutagenesis studies around position 256 of the β subunit are required to clarify whether it is possible to distinguish between sites for PCG and picrotoxin. Tyrosine 256 is predicted to be near the centre of the M2 region, which may lie deep within the channel pore (Gurley et al., 1995). Our data strongly suggests that PCG is similar to picrotoxin and can inhibit GABA-induced currents by acting at a site deep within the channel pore. As the Y256F mutation did not decrease the potency of the natural agonist ligand GABA, these data imply that the hydroxy group of the Tyr256 residue does not directly interact with GABA, or play any major role in maintaining the active conformation of the GABAA-R. In sharp contrast, this single mutation drastically reduced the potency of the antagonist PCG, suggesting that it could interact directly with the hydroxy group of Tyr256. However, this study does not rule out the possibility that the Y256F mutation might result in a critical conformational change in an allosteric binding site for PCG, which may be located on the surface of the receptor, without affecting the conformation of the agonist binding site (Twyman et al., 1992)

In summary, this is the first report on the GABAA-R that uses recombinant receptors and site directed mutagenesis to demonstrate that the antibiotics PCG and CFSL inhibit GABAA-R function via different mechanisms, with the former acting non-competitively and the latter competitively. Site directed mutagenesis of the β subunit also revealed that the site of action of PCG on the GABAA-R might be closely related to the picrotoxin binding site in the M2 region of the β2 subunit.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs J. Yang and D. Burt for providing the mouse GABAA-R subunit clones and Dr K. Finlayson for helpful comments in preparing the manuscript. This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan.

Abbreviations

- CFSL

cefoselis sulphate

- DMSO

dimethylsulphoxide

- GABAA-R

gamma-amino butyric acid type A receptor

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulphonic acid

- PCG

penicillin-G

- Tricaine

3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester

References

- BARNARD E.A., SKOLNICK P., OLSEN R.W., MOHLER H., SIEGHART W., BIGGIO G., BRAESTRUP C., BATESON A.N., LANGER S.Z. International Union of Pharmacology. XV. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptors: classification on the basis of subunit structure & receptor function. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:291–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRONS R.W., MURRAY K.M., RICHEY R.M. Populations at risk for penicillin-induced seizures. Ann. Pharmacother. 1992;26:26–29. doi: 10.1177/106002809202600106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS D.R., GAME C.J.A., JOHNSTON G.A.R., MCCULLOUCH R.M., MACLACHLAN R.M. Convulsive action of penicillin. Brain Res. 1972;43:242–245. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANKS N.P., LIEB W.R. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of general anesthesia. Nature. 1994;367:607–614. doi: 10.1038/367607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUJIMOTO M., MUNAKATA M., AKAIKE N. Dual mechanisms of GABAA response inhibition by β-lactam antibiotics in the pyramidal neurons of the rat cerebral cortex. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:3014–3020. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GURLEY D., AMIN J., ROSS P.C., WEISS D.S., WHITE G. Point mutation in the M2 region of the α, β, or γ subunit of the GABAA channel that abolish block by picrotoxin. Receptors Channels. 1995;3:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORI S., KURIOKA S., MATSUDA M., SHIMADA J. Inhibitory effect of cephalosporins on gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor binding in rat synaptic membranes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1985;27:650–651. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.4.650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINE Y., WATANABE Y., SAKAMOTO H., HATANO K., KUNO K., HIGASHI Y., KAMIMURA T., MATSUMOTO Y., TAWARA S., MATSUMOTO F., KUWAHARA S. In vitro antibacterial activity of FK037, a novel pareteral broad-spectrum cephalosporin. J. Antibiotics. 1993a;46:71–87. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINE Y., WATANABE Y., SAKAMOTO H., HATANO K., WAKAI Y., KAMIMURA T., TAWARA S., MATSUMOTO S., MATSUMOTO F., KUWAHARA S. In vivo antibacterial activity of FK037, a novel parenteral broad-spectrum cephalosporin. J. Antibiotics. 1993b;46:88–98. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PICKLES H.G., SIMMONDS M.A. Antagonism by penicillin of GABA depolarizations at presynaptic sites in rat olfactory cortex and cuneate nucleus in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 1980;19:35–38. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(80)90163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIEGHART W. Structure and pharmacology of γ-aminobutyric acid A receptor subtypes. Pharmacol. Rev. 1995;47:181–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUDA A., ITO M., KISHI K., SHIRAISHI H., TSUDA H., MORI C. Effect of penicillin on GABA-gated chloride ion influx. Neurochem. Res. 1994;19:1–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00966719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TWYMAN R.E., GREEN R.M., MACDONALD R.L. Kinetics of open channel block by penicillin of single GABAA receptor channels from mouse spinal cord neurons in culture. J. Physiol. 1992;445:97–127. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp018914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERDOORN T.A., DRAGUHN A., YMER S., SEEBURG P.H., SAKMANN B. Functional properties of recombinant rat GABAA receptors dependent upon subunit composition. Neuron. 1990;4:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALLACE K.L. Antibiotic-induced convulsions. Crit. Care Clin. 1997;13:741–762. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEINSTEIN L., LERNER P.I., CHEW W.H. Clinical and bacteriologic studies of the effect of “Massive” doses of penicillin G on infections caused by Gram-negative bacilli. N. Engl. J. Med. 1964;271:525–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196409102711101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITING P.J., MCKERNAN R.M., WAFFORD K.A. Structure and pharmacology of vertebrate GABAA receptor subtypes. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 1995;38:95–138. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZENG Y.C., PEZZOLA A., SCOTTI DE CAROLIS A., SAGRATELLA S. Inhibitory influence of morphinans on ictal and interictal EEG changes induced by cortical application of penicillin in rabbits: a comparative study with NMDA antagonists and pentobarbitone. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1992;43:651–656. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90207-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]