Abstract

We have investigated the vasodilating effects of D-erythro-C2-ceramide (C2-ceramide) in methoxamine-contracted rat mesenteric microvessels.

C2-ceramide (10–100 μM) caused a concentration-dependent, slowly developing relaxation which reached maximum values after ≈10 min and partially abated thereafter.

Endothelium removal or inhibitors of guanylyl cyclase (3 μM ODQ), protein kinase A (10 μM H7, 1 μM H89) and various types of K+ channels (10 μM BaCl2, 3 mM tetraethylammonium, 30 nM charybdotoxin, 30 nM iberiotoxin, 300 nM apamine, 10 μM glibenclamide) had only small if any inhibitory effects against C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation, but some of them attenuated vasodilation by sodium nitroprusside or isoprenaline. A combination of ODQ and charybdotoxin almost completely abolished C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation.

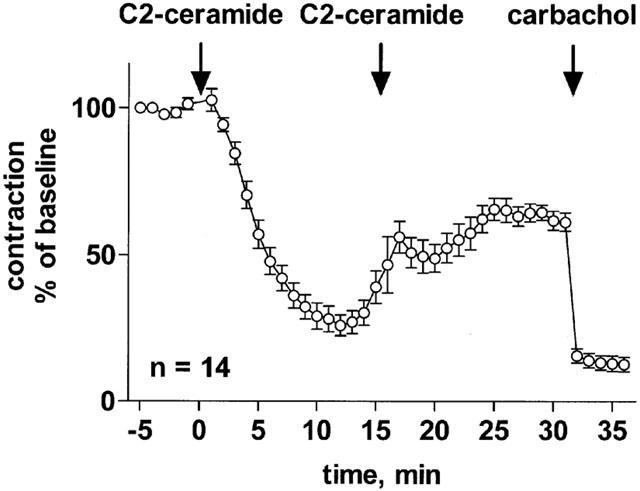

A second administration of C2-ceramide caused a detectable but weaker relaxation. L-threo-C2-ceramide (100 μM), which should not be a substrate to ceramide metabolism, had no biphasic time course. The ceramidase inhibitor (1S,2R)-D-erythro-2-(N-myristoylamino)-1-phenyl-1-propanol (100 μM) alone caused some vasodilation, indicating vasodilation by endogenous ceramides, and also hastened relaxation by exogenous C2-ceramide. The late-developing reversal of C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation was absent when α-adrenergic tone was removed by addition of 10 μM phentolamine.

We conclude that C2-ceramide relaxes rat resistance vessels in an endothelium-independent manner which is prevented only by combined inhibition of guanylyl cyclase and charybdotoxin-sensitive K+ channels. The vasodilation abates with time partly due to desensitization of the ceramide response and partly due to metabolism of C2-ceramide to an inactive metabolite.

Keywords: D-erythro-C2-ceramide, desensitization, endothelium, guanylyl cyclase, isoprenaline, K+ channel, microvessel, sodium nitroprusside, vasodilation

Introduction

Ceramide belongs to a class of biologically active lipids and lipid second messengers, which are characterized by a sphingoid base backbone and are emerging as important widespread bioregulators. Ceramide, which chemically consists of sphingosine and an amide-linked fatty acid, is in the centre of sphingolipid metabolism, and hence is the product of and substrate to a number of metabolic reactions (Hannun, 1996; Hannun & Luberto, 2000; Perry & Hannun, 1998). While many of these metabolic pathways are probably regulated during cellular signalling, most is known about the so-called sphingomyelin cycle. In this cycle the membrane lipid sphingomyelin is cleaved by several distinct sphingomyelinases to produce phosphocholine and ceramide, which can then be metabolized back to sphingomyelin (Hannun & Luberto, 2000). In addition, ceramide can be formed during de novo sphingolipid synthesis, by cleavage of glycosphingolipids, or directly from sphingosine. Accumulation of ceramide is caused by a large number of stimuli, most of them inducers of a stress response, e.g. tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1, chemotherapeutic agents or radiation (Hannun & Luberto, 2000). Accordingly, ceramide has been implicated in apoptosis, inhibition of cell growth and cell cycle arrest as well as differentiation (Hannun & Luberto, 2000). At the molecular level, ceramide can interact with several proteins including ceramide-activated protein phosphatases of the PP1 and PP2A families, a ceramide-activated proline-directed protein kinase and protein kinase C (Galadari et al., 1998; Hannun & Luberto, 2000).

In addition to these direct ceramide effects, ceramide metabolism can give rise to other biologically active lipids such as sphingosine, sphingosine-1-phosphate, glucosyl- or galactosylceramide and ceramide-1-phosphate (Hannun & Luberto, 2000; Pyne & Pyne, 2000). Therefore, some ceramide effects may be mediated by such metabolites. Moreover, the balance between ceramide, sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate has been claimed to act as a cellular rheostat decisive for the cell fate, growth or apoptosis (Cuvillier et al., 1996; Pyne & Pyne, 2000).

While ceramide is mainly recognized as a mediator of apoptosis, some recent papers have described ceramide-induced relaxation of rat aorta which was partially endothelium-dependent and possibly mediated by NO (Johns et al., 1997; 1998; Zheng et al., 1999). However, aorta is a conductance vessel, which may not be representative for the resistance vasculature, and very recent observations in bovine coronary resistance vessels indicate that ceramides may also inhibit vasodilation (Zhang et al., 2001). Moreover, the related sphingolipid sphingosine-1-phosphate causes vasoconstriction in vitro and in vivo (Bischoff et al., 2000a,2000b; 2001a). Therefore, we have investigated whether ceramide also has vasodilating effects in the resistance vasculature using rat mesenteric microvessels as a model system. Furthermore, we have analysed which signalling mechanisms might be involved. In contrast to findings with rat aorta (Johns et al., 1997; 1998; Zheng et al., 1999), ceramide-induced vasodilation abated with time in the mesenteric microvessels. Therefore, mechanisms underlying this abatement were also investigated. For most of our investigations we have used D-erythro-C2-ceramide which will be referred to as C2-ceramide in this manuscript unless otherwise mentioned.

Methods

Contraction experiments

Adult male Wistar rats (250–350 g) were obtained from the breeding facility at the University of Essen. Mesenteric microvessels were prepared from these rats according to Mulvany & Halpern (1977) as recently described (Chen et al., 1996). Briefly, mesenteric vessels adjacent to the gut (second branch counting from the gut, internal diameter 100–200 μm) were isolated from surrounding adipose and connective tissue. The vessel was dissected, and a 40 μm diameter stainless-steel wire was inserted into the lumen of the vessel. In some cases the endothelium was removed by introducing a human hair into the lumen and shoving it carefully backwards and forwards several times. Then, the vessel was mounted in the myograph chamber and fixed to a micrometer screw. A second wire was inserted and connected to a force transducer for isometric recording of tension development. In the myograph, the vessels were bathed in Krebs-Henseleit buffer of the following composition (mM): NaCl 119, NaHCO3 25, KCl 4.7, KH2PO4 1.18, MgSO4 1.17, CaCl2 2.5, EDTA 0.026, glucose 5.5 at 37°C. The chamber was gassed continuously with 5% CO2/95% O2 to maintain pH at 7.4. Before generating noradrenaline concentration-response curves, 1 μM propranolol and 5 μM cocaine were added to the buffer to block β-adrenoceptors and neuronal catecholamine uptake, respectively.

The vessels were allowed 40 min for equilibration. Thereafter, the internal diameter of each vessel was set to a tension equivalent to 0.9 times the estimated diameter at 100 mmHg effective transmural pressure according to the standard procedure of Mulvany & Halpern (1977), and allowed another 20 min for equilibration. Thereafter, the preparations were challenged once with 125 mM KCl and thereafter three times with a combination of KCl and 10 μM noradrenaline, and once more with KCl with washouts after each challenge and 10 min between challenges. At the end of these stimulations, resting tension stabilized at ≈5 mN. Following another 20 min of equilibration, a cumulative concentration-response curve for noradrenaline was generated and thereafter carbachol (100 μM) was added to control the vessels ability to contract and relax, respectively. Thereafter, two different experimental designs were used.

In some experiments, after washout and another 30 min of equilibration, methoxamine was added. In our preparation methoxamine is equally effective as noradrenaline (maximum methoxamine response is 104±2% of maximum noradrenaline response, n=8), and based on a pEC50 of 6.42±0.08 a concentration of 100 μM methoxamine was used in all further experiments. Within 15 min after addition of methoxamine, force of contraction reached a constant level (13.0±0.8 mN, n=34) which was approximately 80% of the initial contraction and was used as baseline; subsequently all contraction data were normalized to the methoxamine baseline values within the same experiment. Unless otherwise noted, ceramides or other agents were added 5 min after responses to methoxamine had stabilized, and contraction was recorded for another 15 min. At the end of each experiment carbachol (100 μM) was added and contraction was recorded for another 5 min.

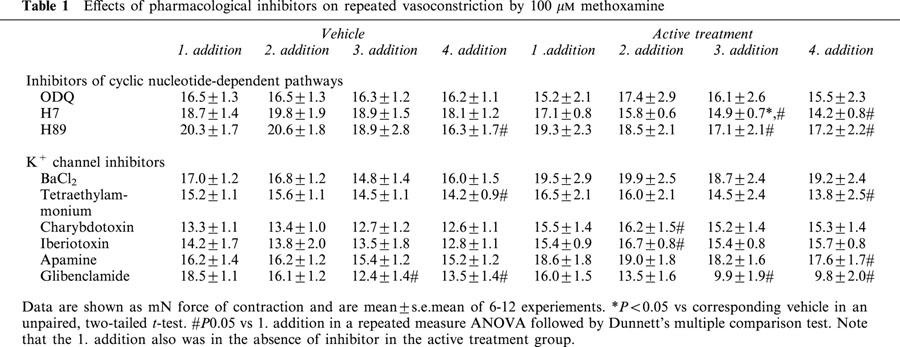

A different design was used to investigate candidate second messenger systems involved in the C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation such as guanylyl cyclase, protein kinase A and various K+ channels: After washout of noradrenaline and carbachol and 30 min of equilibration, methoxamine (100 μM) was added to reach a constant level of force of contraction (first addition). After washout and 30 min of equilibration, the indicated inhibitors and 15 min later methoxamine were added (second addition); when responses to methoxamine had stabilized, a cumulative concentration-response curve for relaxation by sodium nitroprusside (0.1 nM–10 μM) was generated with half-logarithmic increments. After washout and 30 min of equilibration, the inhibitors and 15 min later methoxamine (third addition) were added again and then relaxation responses to isoprenaline (10 nM–100 μM) were studied. After another washout and 30 min of equilibration, the inhibitors and 15 min later methoxamine (fourth addition) were added again and then relaxation responses to 100 μM C2-ceramide were studied for 16 min. Finally, 100 μM carbachol were added. In these experiments, a separate vehicle series was examined for each inhibitor, and inhibitor and matching vehicle were always examined in parallel. Contractile responses to the first, second, third and fourth methoxamine addition in the absence and presence of the inhibitors are shown in Table 1. Propanol was omitted from the buffer in these experiments.

Table 1.

Effects of pharmacological inhibitors on repeated vasoconstriction by 100 μM methoxamine

Chemicals

Apamine, MAPP ((1S,2R)-D-erythro-2-(N-myristoylamino)-1-phenyl-1-propanol), H7 (1-(5-isoquinolinesulfonyl)-2-methylpiperazine 2 HCl) and H89 (N-[2-((p-bromocinnamyl)amino)ethyl]-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide 2 HCl) were from Calbiochem (Bad Soden, Germany). C2-ceramide (D-erythro-C2-ceramide), L-threo-C2-ceramide, D-erythro-C2-dihydro-ceramide and D-erythro-C8-ceramide from Matreya/Biotrend (Köln, Germany), D-erythro-C8-ceramide-1-phosphate and sphingosine-1-phosphate from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA, U.S.A.). Carbachol HCl, charybdotoxin, glibenclamide, iberiotoxin, isoprenaline HCl, methoxamine HCl, noradrenaline bitartrate, ODQ (1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo-[4,3-o]quinoxalin-1-one), phentolamine HCl, (±)-propranolol HCl and tetraethylammonium were from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany). All ceramides were dissolved at 10 mM in methanol. ODQ was dissolved at 30 mM in dimethylsulphoxide, glibenclamide and H89 at 1 and 10 mM, respectively, in ethanol, sodium nitroprusside at 1 in 10 mM HCl, apamine at 3 mM in 5% acetic acid, and H7, tetraethylammonium, iberiotoxin and charybdotoxin at 10 mM, 300 μM, 3 μM and 3 μM, respectively, in deionized water.

Data analysis

Data are shown as means±s.e.mean. Statistical significance of differences between groups was assessed by paired or unpaired two-tailed t-tests when two groups were compared. When multiple groups were compared, analysis of variance or repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test was used. The effect of inhibitors on vasodilation by ceramide was analysed by a two-way analysis of variance using main treatment effect and time as the explanatory variables. All statistical calculations were performed using the Prism program (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.), and P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

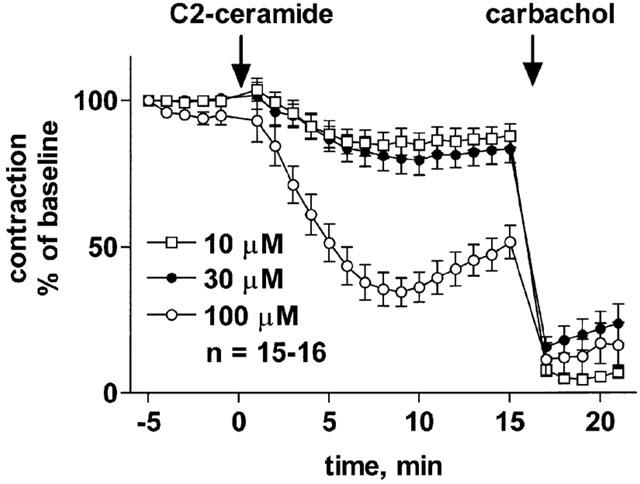

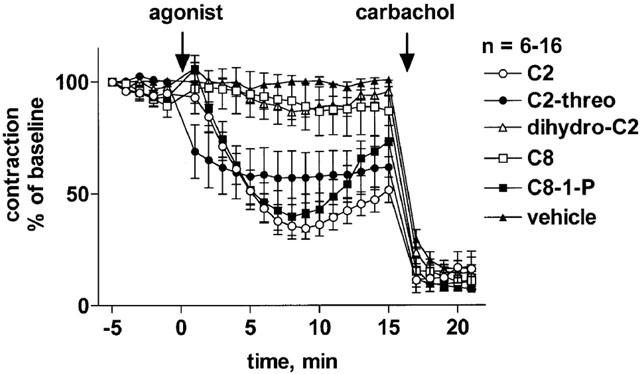

Addition of 100 μM C2-ceramide to rat mesenteric microvessels in the absence of methoxamine caused only minimal if any vasoconstriction effects within a 15 min observation period, i.e. less than 10% of maximum noradrenaline-induced contraction (n=12, data not shown). In methoxamine-pre-contracted microvessels, addition of C2-ceramide caused a slowly developing relaxation which reached maximum values after ≈10 min and partially abated thereafter, yielding a biphasic time course (Figure 1). Maximum relaxations observed with 10, 30 and 100 μM C2-ceramide were 15±4% (n=15), 20±5% (n=15) and 65±5% (n=16), respectively (Figure 1). While this indicates a concentration-dependent response, it remains unclear whether 100 μM C2-ceramide is the maximally effective concentration because higher concentrations could not be tested for technical reasons. At a concentration of 100 μM, several ceramide-derivatives caused vasodilation with a rank order of C2-ceramide ≈ D-erythro-C8-ceramide-1-phosphate>L-threo–C2-ceramide >> D-erythro-C2-dihydro-ceramide ≈ D-erythro-C8-ceramide, with the latter two causing only little if any vasodilation (Figure 2). Interestingly, the biphasic time course of C2-ceramide was mimicked by D-erythro-C8-ceramide-1-phosphate but not by L-threo–C2-ceramide (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Concentration-dependent relaxation of methoxamine-pre-contracted rat mesenteric microvessels by C2-ceramide. C2-ceramide at the indicated concentrations was added to microvessels pre-contracted with 100 μM methoxamine (n=15–16). Fifteen minutes later, 100 μM carbachol was added to verify the functional intactness of the endothelium. Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to ceramide addition (baseline).

Figure 2.

Effects of various ceramides on methoxamine-pre-contracted rat mesenteric microvessels. D-erythro-C2-ceramide (C2), L-threo-C2-ceramide (C2-threo), D-erythro-C2-dihydro-ceramide (dihydro-C2), D-erythro-C8-ceramide (C8) or D-erythro-C8-ceramide-1-phosphate (C8-1-P; 100 μM each) were added to microvessels pre-contracted with 100 μM methoxamine (n=6–16). Fifteen minutes later, 100 μM carbachol was added to verify the functional intactness of the endothelium. Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to addition of the ceramides (baseline).

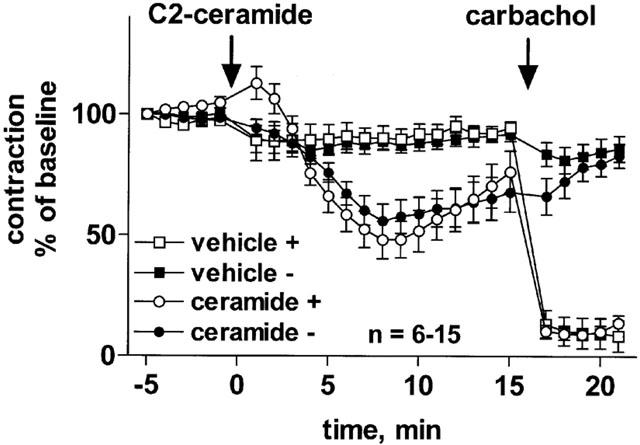

Mechanical removal of the endothelium did not significantly affect the potency (−log EC50 6.72±0.07 vs 6.69±0.09; n=19; P=0.7283 in a paired t-test) or maximum effects of noradrenaline (14.1±1.2 vs 16.6±0.8 mN; P=0.1212 in a paired t-test) in a separate series of experiments (data not shown). As expected, endothelium removal abolished the relaxant effect of 100 μM carbachol (Figure 3). In contrast, the relaxant effect of 100 μM C2-ceramide was not markedly altered by removal of the endothelium (maximum relaxation 44±7% vs 52±8%, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Role of endothelium in C2-ceramide-induced relaxation of rat mesenteric microvessels. C2-ceramide (100 μM) or corresponding vehicle were added to microvessels pre-contracted with 100 μM methoxamine (n=6–15). Fifteen minutes later, 100 μM carbachol was added to verify the functional intactness of the endothelium. Experiments were performed in control vessels (+) and in vessels in which the endothelium had been removed mechanically prior to the experiment (−). Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to ceramide addition (baseline).

Further experiments were performed to study the possible involvement of several candidate signal transduction systems for vasodilation by C2-ceramide and, for comparison, by sodium nitroprusside and isoprenaline. Four consecutive methoxamine additions yielded largely stable responses in the presence of most inhibitors; while addition of H7, H89 and glibenclamide caused some reduction of the methoxamine responses, this was largely due to effects of the respective vehicles (Table 1). Accordingly, none of the inhibitors altered methoxamine-induced vasoconstriction by more than 30% relative to the corresponding vehicle (Table 1, P<0.05 only for H7).

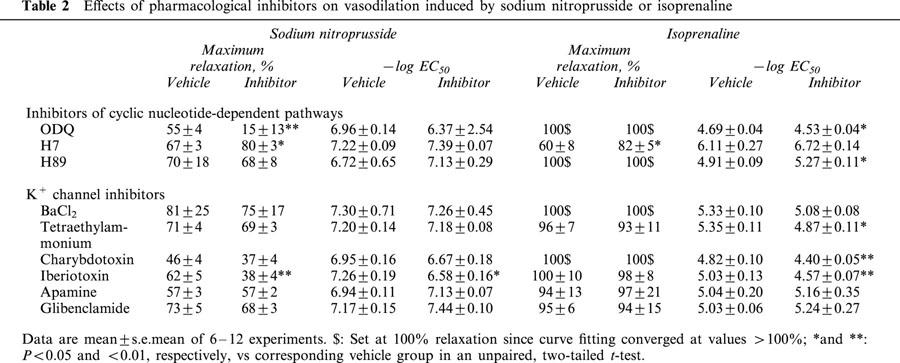

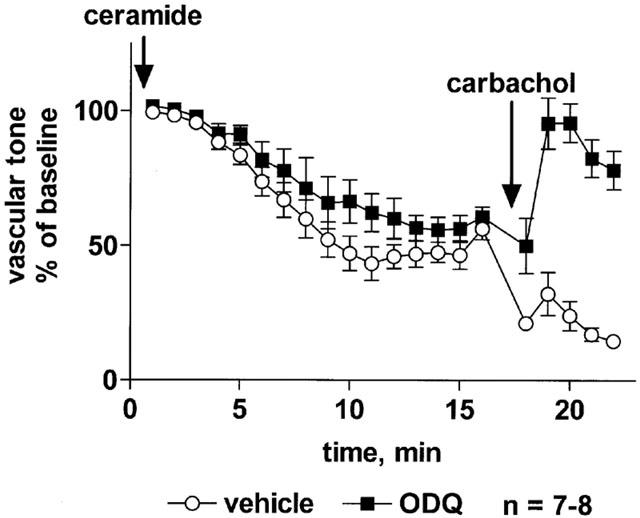

The guanylyl cyclase inhibitor ODQ (3 μM) almost completely abolished vasodilation by sodium nitroprusside (Table 2) and carbachol (Figure 4), but had only little effect on isoprenaline-induced vasodilation (Table 2). ODQ also produced a small but statistically significant inhibition of the C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation (maximum relaxation 44±5% vs 53±5%; Figure 4).

Table 2.

Effects of pharmacological inhibitors on vasodilation induced by sodium nitroprusside or isoprenaline

Figure 4.

Effect of the guanylyl cyclase inhibitor ODQ on C2-ceramide-induced relaxation of rat mesenteric microvessels. ODQ (3 μM) or vehicle was added, followed by methoxamine (100 μM) and after 15 min by C2-ceramide (100 μM, n=7–8). Seventeen minutes later, 100 μM carbachol was added to test the inhibitor effect on endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to ceramide addition (baseline) as shown in Table 1. The inhibitor effect of ODQ was statistically significant (P=0.0018) in a two-way ANOVA for the overall treatment effect.

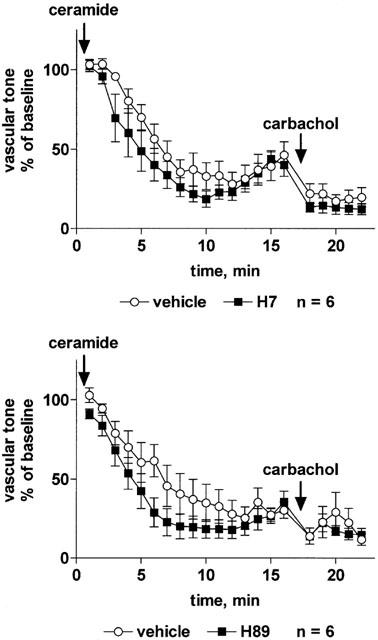

The protein kinase A inhibitors H7 (10 μM) and H89 (1 μM) had only minor effects on vasodilation induced by sodium nitroprusside and, surprisingly, by isoprenaline, and in either case if anything a slight sensitization of the response was observed (Table 2). Similarly, both protein kinase A inhibitors also resulted in a small but statistically significant facilitation of C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation, which manifested itself by faster relaxation without major alterations of maximum effects (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of the protein kinase A inhibitors H7 and H89 on C2-ceramide-induced relaxation of rat mesenteric microvessels. H7 (10 μM, upper panel), H89 (1 μM, lower panel) or their vehicles were added, followed by methoxamine (100 μM) and after 15 min by C2-ceramide (100 μM, n=6 each). Seventeen minutes later, 100 μM carbachol was added to test the inhibitor effect on endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to ceramide addition (baseline) as shown in Table 1. The inhibitor effects of H7 and H89 were statistically significant (P=0.0003 and P<0.0001, respectively) in a two-way ANOVA for the overall treatment effect.

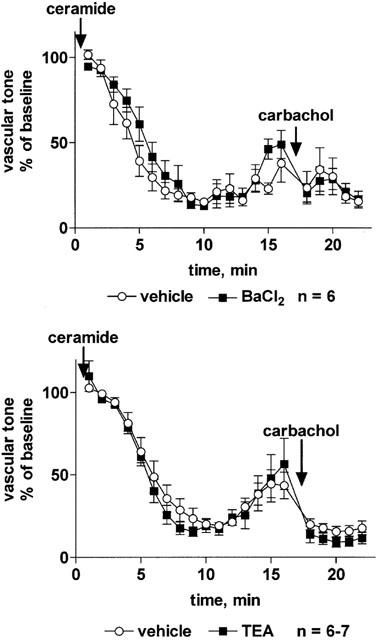

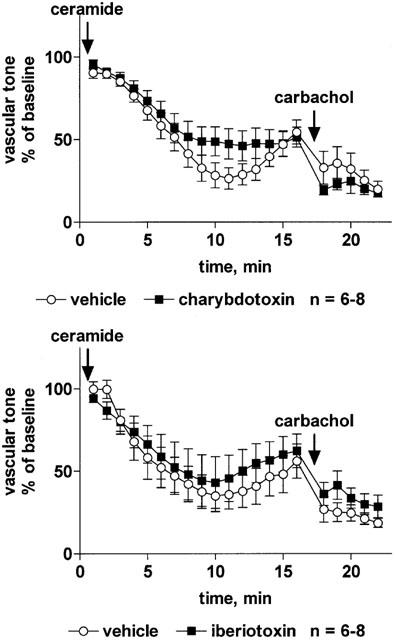

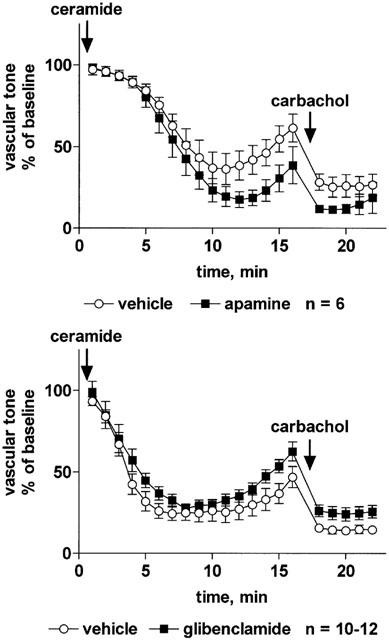

Among the K+ channel inhibitors, only iberiotoxin (30 nM) significantly attenuated the vasodilation response to sodium nitroprusside, whereas BaCl2 (10 μM), tetraethylammonium (3 mM), charybdotoxin (30 nM), apamine (300 nM) and glibenclamide (10 μM) had no effect (Table 2). The vasodilation response to isoprenaline was slightly but significantly attenuated by tetraethylammonium, charybdotoxin and iberiotoxin (but not by BaCl2, apamine or glibenclamide); in either case the inhibition consisted of a right-shift of the concentration-response curve by less than half a log unit and did not affect the maximum vasodilation response to isoprenaline (Table 2). The vasodilation response to C2-ceramide was not affected by tetraethylammonium (Figure 6) or iberiotoxin (Figure 7) whereas charybdotoxin (Figure 7) and glibenclamide (Figure 8) caused a minor but statistically significant inhibition, and apamine caused a minor but statistically significant enhancement of C2-ceramide-induced relaxation (Figure 8). BaCl2 did not affect maximum relaxation by C2-ceramide but tended to cause a minor slowing of its time course (P=0.0506 in a two-way ANOVA for the main treatment effect, Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of the K+ channel inhibitors BaCl2 and tetraethylammonium on C2-ceramide-induced relaxation of rat mesenteric microvessels. BaCl2 (10 μM, upper panel), tetraethylammonium (TEA, 3 mM, lower panel) or their vehicles were added, followed by methoxamine (100 μM) and after 15 min by C2-ceramide (100 μM, n=6–7). Seventeen minutes later, 100 μM carbachol was added to test the inhibitor effect on endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to ceramide addition (baseline) as shown in Table 1.

Figure 7.

Effect of the K+ channel inhibitors charybdotoxin and iberiotoxin on C2-ceramide-induced relaxation of rat mesenteric microvessels. Charybdotoxin (30 nM, upper panel), iberiotoxin (30 nM, lower panel) or their vehicles were added, followed by methoxamine (100 μM) and after 15 min by C2-ceramide (100 μM, n=6–8). Seventeen minutes later, 100 μM carbachol was added to test the inhibitor effect on endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to ceramide addition (baseline) as shown in Table 1. The inhibitor effect of charybdotoxin (but not of iberiotoxin) was statistically significant (P=0.0022) in a two-way ANOVA for the overall treatment effect.

Figure 8.

Effect of the K+ channel inhibitors apamine or glibenclamide on C2-ceramide-induced relaxation of rat mesenteric microvessels. Apamine (300 nM, upper panel), glibenclamide (10 μM, lower panel) or their vehicles were added, followed by methoxamine (100 μM) and after 15 min by C2-ceramide (100 μM, n=6–12). Seventeen minutes later, 100 μM carbachol was added to test the inhibitor effect on endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to ceramide addition (baseline) as shown in Table 1. The enhancing effect of apamine and the inhibitor effect of glibenclamide were statistically significant (P=0.0097 and P=0.0072, respectively) in a two-way ANOVA for the overall treatment effect.

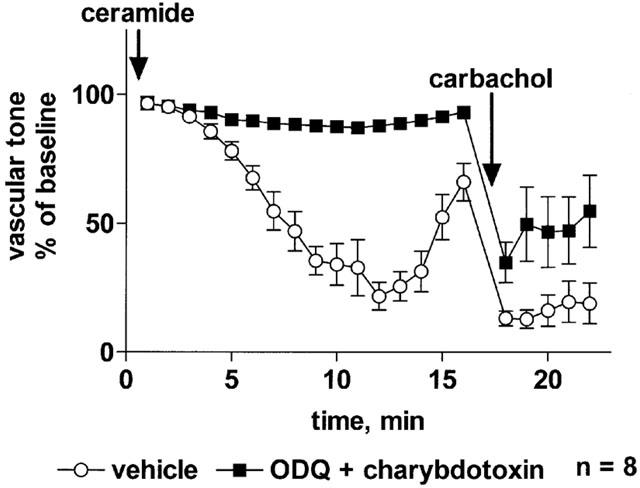

The observation that each of the above inhibitors had only minor effects on C2-ceramide-induced relaxation suggests that relaxation occurs by a mechanism distinct from those being inhibited or that a combination of mechanisms is active. To test these possibilities, we have investigated C2-ceramide-induced relaxation in the combined presence of ODQ (3 μM) and charybdotoxin (30 nM). This combination almost completely abolished the C2-ceramide-induced relaxation (maximum relaxation 12±2% vs 78±5%; Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Effect of a combination of ODQ and charybdotoxin on C2-ceramide-induced relaxation of rat mesenteric microvessels. The combination of ODQ (3 μM) and charybdotoxin (30 nM) or of their vehicles were added, followed by methoxamine (100 μM) and after 15 min by C2-ceramide (100 μM, n=8). Seventeen minutes later, 100 μM carbachol was added to test the inhibitor effect on endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to ceramide addition (baseline).

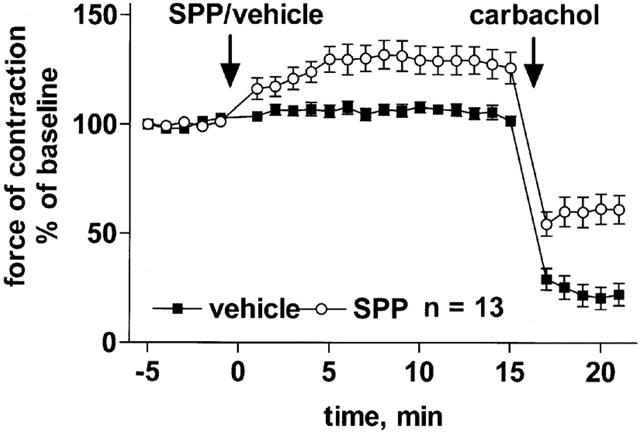

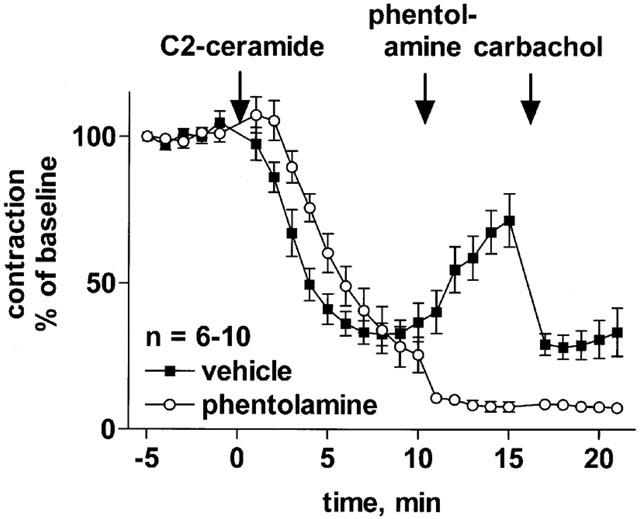

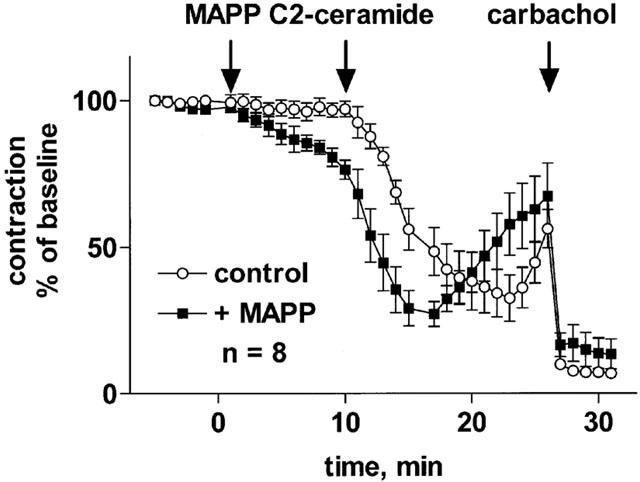

To elucidate the consistently observed biphasic time course of C2-ceramide effects on mesenteric microvessel tone, further experiments tested whether C2-ceramide was metabolized to a vasoconstricting or an inactive agent and whether cellular desensitization of C2-ceramide responses occurs. Since the ceramide metabolites sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate can constrict mesenteric microvessels (Bischoff et al., 2000a), we tested whether 100 μM sphingosine-1-phosphate could also cause vasoconstriction in the presence of methoxamine and thus be responsible for reversal of relaxation. These experiments demonstrated a small but detectable vasoconstriction by sphingosine-1-phosphate in the presence of methoxamine (Figure 10). Similar findings were obtained with the related 100 μM sphingosylphosphorylcholine (data not shown). On the other hand, the late reversal of ceramide-induced vasodilation was completely abolished when the vasoconstricting tone of methoxamine was prevented by addition of phentolamine (Figure 11), indicating that no vasoconstricting agent was generated. This was further supported by experiments with the ceramidase inhibitor, MAPP (Bielawska et al., 1996) which prevents formation of sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate from ceramide and causes accumulation of the latter (Bielawska et al., 1996; Hannun & Luberto, 2000). Addition of MAPP (100 μM) alone caused a very slowly developing relaxation of methoxamine-contracted microvessels which was ≈20% after 10 min relative to vehicle-treated time controls (Figure 12). In the presence of MAPP, the maximum relaxant effect of C2-ceramide remained unaltered but was hastened; maximum relaxation was reached within 5 min as compared to maximum relaxation by C2-ceramide in the absence of MAPP after ≈10 min (Figure 12). Importantly, recovery of force of contraction after initial relaxation was somewhat slower but not prevented in the presence of MAPP (Figure 12).

Figure 10.

Effect of sphingosine-1-phosphate (SPP) on methoxamine-pre-contracted rat mesenteric microvessels. SPP (100 μM) or vehicle was added to microvessels pre-contracted with 100 μM methoxamine (n=13). Fifteen minutes later, 100 μM carbachol was added to verify the functional intactness of the endothelium. Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to SPP addition (baseline).

Figure 11.

Influence of α-adrenoceptor antagonism on the late phase of the effect of C2-ceramide on rat mesenteric microvessels. C2-ceramide (100 μM) was added to microvessels pre-contracted with 100 μM methoxamine (n=6–10). Ten minutes later, 10 μM phentolamine or vehicle was added, and another 5 min later 100 μM carbachol was added to verify the functional intactness of the endothelium. Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to ceramide addition (baseline).

Figure 12.

Effect of C2-ceramide on rat mesenteric microvessel tone in the absence and presence of a ceramidase inhibitor. The ceramidase inhibitor, MAPP (100 μM) or corresponding vehicle (control) were added to microvessels pre-contracted with 100 μM methoxamine. Ten minutes later, 100 μM C2-ceramide was added (n=8). After another 15 min, 100 μM carbachol was added to verify the functional intactness of the endothelium. Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to MAPP addition (baseline).

To determine whether desensitization was involved, we added C2-ceramide (100 μM) a second time, i.e. 15 min after the first addition (Figure 13). The second administration of C2-ceramide not only prevented the late-developing vasoconstriction, but rather caused detectable additional relaxation; however, this second phase of relaxation was smaller than the initial relaxation, short-lived and abated with time.

Figure 13.

Effect of repeated C2-ceramide administration on rat mesenteric microvessels. C2-ceramide (100 μM) was added to microvessels pre-contracted with 100 μM methoxamine, followed by a second administration of C2-ceramide (100 μM) 15 min later (n=14). After another 15 min, 100 μM carbachol was added to verify the functional intactness of the endothelium. Data are expressed as per cent of the response to methoxamine prior to ceramide addition (baseline).

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that C2-ceramide can concentration-dependently relax pre-contracted rat aortic rings (Johns et al., 1997; 1998; Zheng et al., 1999), whereas it inhibits endothelium-dependent vasodilation in bovine small coronary arteries (Zhang et al., 2001). Because of these controversial data and particularly since aorta contributes only little to the regulation of peripheral resistance, the present study has investigated ceramide effects in a part of the resistance vasculature, i.e. mesenteric microvessels (Chen et al., 1996). Our data demonstrate that C2-ceramide causes a slowly developing, concentration-dependent relaxation of microvessels pre-contracted with the α1-adrenoceptor agonist methoxamine. While aorta and mesenteric microvessels exhibited similar maximal C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation, the aorta appears to be slightly more sensitive to C2-ceramide than the mesenteric microvessels.

In rat aorta, D-erythro-C2-dihydro-ceramide was inactive (Zheng et al., 1999). In the present study, D-erythro-C2-dihydro-ceramide, similar to the long-chain D-erythro-C8-ceramide, also had little effect on vascular tone, whereas the stereo-isomer of C2-ceramide, L-threo-C2-ceramide, and D-erythro-C8-ceramide-1-phosphate produced considerable vasodilation. Whether this relates to the possibility that some ceramides are less cell permeant than others, remains to be determined. The overall data, however, demonstrate that ceramide-induced vasodilation is not a non-specific lipid effect but rather has distinct structure-activity relationships. The hypothesis of a specific ceramide effect on vascular tone is further supported by the observation that the ceramidase inhibitor MAPP (Bielawska et al., 1996) hastened relaxation by C2-ceramide. Our observation that MAPP alone also caused some vasodilation suggests that endogenous ceramides may also cause vasodilation.

Vasodilation can occur by a variety of mechanisms, some of which are endothelium-dependent and involve release of NO, vasodilating prostaglandins and/or endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. In rat aorta, mechanical endothelium removal or inhibition of NO synthase partly attenuated the vasodilating effects of C2-ceramide (Johns et al., 1998; Zheng et al., 1999). In contrast, C2-ceramide-induced relaxation of mesenteric microvessels was not significantly affected by mechanical endothelium removal, although that manoeuvre abolished vasodilation induced by carbachol. Thus, endothelium-derived NO release may partly be relevant in ceramide-induced vasodilation in rat aorta but not in rat mesenteric microvessels, suggesting a regional heterogeneity in vascular ceramide responses. A variety of other mechanisms can mediate endothelium-independent vasodilation, including activation of a guanylyl cyclase, activation of a protein kinase A, inhibition of a protein kinase C, activation of protein phosphatases, activation of K+ channels and inhibition of cellular Ca2+ elevations, and some of these mechanisms may act sequentially. Inhibition of cellular Ca2+ elevations or activation of protein phosphatases are difficult to test as mechanisms of relaxation, since interference with either pathway will also affect α1-adrenoceptor-mediated vasoconstriction independent of the concomitant presence of a vasodilating agent (Chen et al., 1996; Fetscher et al., 2001; Knapp et al., 2000). Nevertheless inhibition of Ca2+ elevations should be kept in mind as a potential mechanism of C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation, since C2-ceramide can inhibit α1-adrenoceptor-stimulated Ca2+ elevations in rat aortic smooth muscle cells (Zheng et al., 1999). Ceramides can inhibit protein kinase C (Hannun, 1996), and protein kinase C inhibition has been reported to attenuate α1-adrenoceptor-induced vasoconstriction in some vascular beds (Lee et al., 1999). However, this mechanism is unlikely to be relevant for C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation in rat mesenteric microvessels, since α1-adrenoceptor-induced vasoconstriction in this preparation is not affected by protein kinase C inhibition (Fetscher et al., 2001). Moreover, C2-ceramide-induced relaxation of rat aorta is not affected by inhibition of protein kinase C (Zheng et al., 1999).

Therefore, we have focused on three other candidate signalling mechanisms which might mediate endothelium-independent vasodilation by ceramides, i.e. activation of a guanylyl cyclase which may cause vasodilation due to elevated cellular cyclic GMP levels (Koesling, 1998), activation of a protein kinase A which may cause vasodilation e.g. due to inhibition of cellular Ca2+ entry (Pyne & Pyne, 1996), and activation of various types of K+ channels which may cause vasodilation secondary to cellular hyperpolarization (Kuriyama et al., 1995). In this respect sodium nitroprusside and isoprenaline were studied for comparison. While cumulative concentration-response curves could be analysed for sodium nitroprusside and isoprenaline, only a single high concentration of C2- ceramide could be tested within each preparation because; (a) C2-ceramide exhibited a very steep concentration-response relationship; and (b) the time course of C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation was biphasic and this biphasicity was at least partly due to desensitization of the response (see below). This technical limitation should be kept in mind when interpreting the present data.

Activation of a guanylyl cyclase is the well established mechanism of action for vasodilation not only by endothelium-derived NO but also by organic nitrates including sodium nitroprusside (Calver et al., 1993). Accordingly, the guanylyl cyclase inhibitor ODQ almost completely abolished vasodilation by sodium nitroprusside. The small but statistically significant right-shift of the isoprenaline concentration-response curve is in good agreement with recent reports on a contribution of NO release to the vasodilating properties of β-adrenoceptor agonists (Trochu et al., 1999; Xu et al., 2000). Similarly, ODQ caused a minor but statistically significant inhibition of vasodilation by ceramide.

The β-adrenoceptor agonist isoprenaline and various other cyclic AMP-elevating or cyclic AMP-mimicking agents cause vasodilation in various blood vessels. In the present study two protein kinase A inhibitors surprisingly failed to antagonize the isoprenaline-induced vasodilation, and both H7 and H89 if anything slightly enhanced vasodilation by isoprenaline, sodium nitroprusside and C2-ceramide. While it may be surprising that β-adrenoceptor-mediated vasodilation is not protein kinase A-mediated, recent data from other investigators also demonstrate that β-adrenoceptor agonist effects on vascular smooth muscle cells occur at least partly independent of protein kinase A (Viard et al., 2001). Therefore, the present data cannot exclude a role for cyclic AMP in C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation but clearly demonstrate that protein kinase A is not involved. A more detailed analysis of potential enhancements of vasodilation by H7 and H89 was beyond the scope of the present study.

Activation of K+ channels is a well documented mechanism of vasodilating drugs (Kuriyama et al., 1995). The multitude of K+ channel types which may be involved and the limited availability of tools for highly selective inhibition of individual channels hamper a detailed association of vasodilation by a specific agent with a specific K+ channel type. In the present study, the broad-spectrum K+ channel inhibitors BaCl2 and tetraethylammonium did not have major effects on vasodilation by sodium nitroprusside, isoprenaline or C2-ceramide. Although the KATP channel blocker glibenclamide has been reported to partially inhibit isoprenaline-induced vasodilation in the hypoxic pulmonary circulation (Dumas et al., 1999), it did not affect vasodilation by isoprenaline in the present study and also had little if any effect on vasodilation by sodium nitroprusside or C2-ceramide. Apamine is an inhibitor of SKCa small conductance K+ channels and has been shown to inhibit e.g. β3-adrenoceptor-mediated vasodilation in a perfused hypoxic lung preparations (Dumas et al., 1999). However, in the present study apamine did not affect vasodilation by isoprenaline or sodium nitroprusside and surprisingly even enhanced vasodilation by C2-ceramide. Finally, two inhibitors of BKCa large conductance Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels, charybdotoxin and iberiotoxin, have been studied. While iberiotoxin inhibited the vasodilation response to sodium nitroprusside and, to a lesser extent, isoprenaline, charybdotoxin was ineffective against these two vasodilators. In contrast, charybdotoxin but not iberiotoxin caused a small but statistically significant inhibition of C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation.

Taken together the above data suggest that inhibition of any of the tested signalling pathways is insufficient to markedly attenuate vasodilation by C2-ceramide. Thus, C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation could occur by a novel as yet undefined mechanism or by the combination of multiple mechanisms which are activated in parallel and can at least partly compensate for each other if one of them is inhibited. To test this possibility we have investigated the combination of the two strongest inhibitors of C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation, i.e. ODQ and charybdotoxin. This combination almost completely abolished the relaxant effects of C2-ceramide. These data suggest that C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation involves activation of both a guanylyl cyclase and BKCa large conductance Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels, but the molecular link between C2-ceramide and these effector pathways remains to be determined.

In contrast to observations in rat aorta (Johns et al., 1997), our experiments revealed a consistently biphasic time course of C2-ceramide effects in mesenteric microvessels. Thus, vasodilation reached a nadir after ≈10 min and abated thereafter. Three possibilities could explain this biphasic time course: Firstly, it could be due to abatement of the C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation by cellular desensitization and/or to C2-ceramide depletion, e.g. by cellular metabolism to an inactive form. Second, it could be due to metabolism of the vasodilating C2-ceramide to a vasoconstricting agent. Third, C2-ceramide may itself exhibit vasodilating and vasoconstricting properties with vasoconstriction developing much slower than vasodilation. Therefore, further experiments were designed to test these hypotheses.

Ceramides can be metabolized to sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate (Hannun & Luberto, 2000), which have recently been shown to constrict the rat mesenteric vasculature in vitro (Bischoff et al., 2000a) and in vivo (Bischoff et al., 2000b; 2001b). Indeed, our data demonstrated that sphingosine-1-phosphate can cause some vasoconstriction even in the presence of the α1-adrenoceptor agonist, methoxamine. If this would underlie the late-developing vasoconstriction, it should remain detectable or even enhanced upon withdrawal of α-adrenergic tone. However, our experiments with phentolamine demonstrated that withdrawal of α-adrenergic tone completely prevented the late-developing vasoconstriction by C2-ceramide, which is in line with our experiments demonstrating that C2-ceramide itself is not a vasoconstrictor. Furthermore, inhibition of ceramidase did not prevent the appearance of the vasoconstriction phase. Thus, metabolism of C2-ceramide to vasoconstricting sphingosine or sphingosine-1-phosphate does not appear to play a major role in the late developing re-occurrence of vascular tone, although formation of a C2-ceramide metabolite with so far unrecognized vasoconstricting properties cannot be excluded.

On the other hand, several lines of evidence indicate that abatement of vasodilation is involved in the late-developing re-occurrence of vascular tone. Thus, a second administration of C2-ceramide added during the phase of late-developing vasoconstriction caused some vasodilation but less than the first administration. This suggests that cellular desensitization is involved in the biphasic time course of C2-ceramide in the mesenteric microvessels but cannot fully explain it. Additionally, ceramide metabolism appears to contribute to the late-developing increase in vascular tone. Thus, a second dose of ceramide at least temporarily prevented the late-developing vasoconstriction. Moreover, the stereo-isomer, L-threo-C2-ceramide, which should not be a substrate to C2-ceramide metabolism (Hannun & Luberto, 2000), had no biphasic time course. Therefore, the overall data suggest that the late-developing vasoconstriction is mainly due to desensitization of C2-ceramide-induced vasodilation and may additionally involve metabolism of C2-ceramide to an inactive form.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that ceramides can relax not only rat aorta (Johns et al., 1997; 1998; Zheng et al., 1999) but also mesenteric microvessels. This occurs with distinct structure-activity relationships and via distinct mechanisms. Vasodilation in the microvessels is, in contrast to rat aorta, endothelium-independent and appears to involve a combination of activation of a guanylyl cyclase and BKCa large conductance Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels. Moreover, the effect of exogenous C2-ceramide on mesenteric microvessels has a biphasic time course with a late-developing vasoconstriction which may involve multiple factors including desensitization and (agonist) stimulus depletion from the organ bath by metabolism. Since ceramide accumulation is caused by stimuli such as tumour necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1 (Hannun & Luberto, 2000), we speculate that ceramide-induced vasodilation could play a pathophysiological role in states such as septic shock.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the intramural grant program of the University of Essen Medical School (IFORES) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Bi 544/2-1).

Abbreviations

- C2-ceramide

D-erythro-C2-ceramide

- MAPP

(1S,2R)-D-erythro-2-(N-myristoylamino)-1-phenyl-1-propanol

- ODQ

1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo-[4,3-o]quinoxalin-1-one

References

- BIELAWSKA A., GREENBERG M.S., PERRY D., JAYADEV S., SHAYMAN J.A., MCKAY C., HANNUN Y.A. (1S,2R)-D-erythro-2-(N-myristoylamino)-1-phenyl-1-propanol as an inhibitor of ceramidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:12646–12654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISCHOFF A., CZYBORRA P., FETSCHER C., MEYER ZU HERINGDORF D., JAKOBS K.H., MICHEL M.C. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and sphingosylphosphorylcholine constrict renal and mesenteric microvessels in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000a;130:1871–1877. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISCHOFF A., CZYBORRA P., MEYER ZU HERINGDORF D., JAKOBS K.H., MICHEL M.C. Sphingosine-1-phosphate reduces rat renal and mesenteric blood flow in vivo in a pertussis toxin-sensitive manner. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000b;130:1878–1883. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISCHOFF A., FINGER J., MICHEL M.C. Nifedipine inhibits sphingosine-1-phosphate-induced renovascular contraction in vitro and in vivo. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2001a;364:179–182. doi: 10.1007/s002100100446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISCHOFF A., MEYER ZU HERINGDORF D., JAKOBS K.H., MICHEL M.C. Lysosphingolipid receptor-mediated diuresis and natriuresis in anaesthetised rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001b;132:1925–1933. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALVER A., COLLIER J., VALLANCE P. Nitric oxide and cardiovascular control. Exp. Physiol. 1993;78:303–326. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1993.sp003687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN H., FETSCHER C., SCHÄFERS R.F., WAMBACH G., PHILIPP T., MICHEL M.C. Effects of noradrenaline and neuropeptide Y on rat mesenteric microvessel contraction. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1996;353:314–323. doi: 10.1007/BF00168634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUVILLIER O., PIRIANOV G., KLEUSER B., VANEK P.G., COSO O.A., GUTKIND S., SPIEGEL S. Suppression of ceramide-mediated programmed cell death by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Nature. 1996;381:800–803. doi: 10.1038/381800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUMAS J.-P., GOIRAND F., BARDOU M., DUMAS M., ROCHETTE L., ADVENIER C., GIUDICELLI J.-F. Role of potassium channels and nitric oxide in the relaxant effects elicited by ß-adrenoceptor agonists on hypoxic vasoconstriction in the isolated perfused lung of the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:421–428. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FETSCHER C., CHEN H., SCHÄFERS R.F., WAMBACH G., HEUSCH G., MICHEL M.C. Modulation of noradrenaline-induced microvascular constriction by protein kinase inhibitors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2001;363:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s002100000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALADARI S., KISHIKAWA K., KAMIBAYASHI C., MUMBY M.C., HANNUN Y.A. Purification and characterization of ceramide-activated protein phosphatases. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11232–11238. doi: 10.1021/bi980911+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANNUN Y.A. Functions of ceramide in coordinating cellular responses to stress. Science. 1996;274:1855–1859. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANNUN Y.A., LUBERTO C. Ceramide in the eukaryotic stress response. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01694-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNS D.G., JIN J.-S., WEBB R.C. The role of the endothelium in ceramide-induced vasodilation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;349:R9–R10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNS D.G., OSBORN H., WEBB R.C. Ceramide: a novel cell signaling mechanism for vasodilation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;237:95–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KNAPP J., BOKNIK P., LINCK B., LÜSS H., MÜLLER F.U., PETERTÖNJES L., SCHMITZ W., NEUMANN J. Cantharidine enhances norepinephrine-induced vasoconstriction in an endothelium-dependent fashion. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;294:620–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOESLING D. Modulators of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1998;358:123–126. doi: 10.1007/pl00005232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KURIYAMA H., KITAMURA K., NABATA H. Pharmacological and physiological significance of ion channels and factors that modulate them in vascular tissues. Pharmacol. Rev. 1995;47:387–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE Y.H., KIM I., LAPORTE R., WALSH M.P., MORGAN K.G. Isozyme-specific inhibitors of protein kinase C translocation: effects on contractility of single permeabilized vascular muscle cells of the ferret. J. Physiol. (London) 1999;517:709–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0709s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULVANY M.J., HALPERN W. Contractile properties of small arterial resistance vessels in spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Circ. Res. 1977;41:19–26. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERRY D.K., HANNUN Y.A. The role of ceramide in cell signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1436:233–243. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PYNE S., PYNE N.J. The differential regulation of cyclic AMP by sphingomyelin-derived lipids and the modulation of sphingolipid-stimulated extracellular signal regulated kinase-2 in airway smooth muscle. Biochem. J. 1996;315:917–923. doi: 10.1042/bj3150917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PYNE S., PYNE N.J. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signalling in mammalian cells. Biochem. J. 2000;349:385–402. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TROCHU J.-N., LEBLAIS V., RAUTUREAU Y., BEVERELLI F., LE MAREC H., BERDEAUX A., GAUTHIER C. Beta 3-adrenoceptor stmiulation induces vasorelaxation mediated essentially by endothelium-derived nitric oxide in rat thoracic aorta. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:69–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIARD P., MACREZ N., MIRONNEAU C., MIRONNEAU J. Involvement of both G protein αs and βγ subunits in β-adrenergic stimulation of vascular L-type Ca2+ channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;132:669–676. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU B., LI J., GAO L., FERRO A. Nitric oxide-dependent vasodilation of rabbit femoral artery by β2-adrenergic stimulation or cyclic AMP elevation in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:969–974. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG D.X., ZOU A.-P., LI P.-L. Ceramide reduces endothelium-dependent vasodilation by increasing superoxide production in small bovine coronary arteries. Circ. Res. 2001;88:824–831. doi: 10.1161/hh0801.089604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHENG T., LI W., WANG J., ALTURA B.T., ALTURA B.M. C2-Ceramide attenuates phenylephrine-induced vasoconstriction and elevation in [Ca2+]i in rat aortic smooth muscle. Lipids. 1999;34:689–695. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0414-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]