Abstract

Caspases and calpains are mediators of apoptotic cell death. The objective of this study was to determine the role of caspases and calpains in primary cerebrocortical neuronal (CCN) death in response to a range of stimuli which reportedly induce neuronal apoptosis.

Cell death of primary cultures of rat CCN was induced by staurosporine (STS), C2-ceramide (CER), camptothecin (CMT), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA). Caspase and calpain activity were assessed by cleavage of α-fodrin or fluorogenic substrates. Cell death was analysed by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay in the absence or presence of the pan-caspase inhibitor Boc-Asp-(OMe)-Fluoromethylketone (Baf) and/or the calpain inhibitor calpeptin (CP).

Cell death induced by STS, CER or CMT was accompanied by chromatin condensation and activation of multiple caspases, particularly caspase-3-type proteases. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) treatment was accompanied by activation of caspases -1, -6 and -8, but not -3, whereas none of the caspases tested were activated in response to NMDA.

With the exception of H2O2, when cell death was accompanied by caspase activation, it was significantly suppressed by Baf.

All stimuli also induced calpain activation, but calpeptin only suppressed cell death induced by H2O2. Furthermore, co-treatment with Baf and calpeptin did not alter the cell death relative to either inhibitor alone.

These findings suggest the existence of stimulus-dependent routes for the activation of caspases and calpains during death of cortical neurones and imply that although caspases and calpains are activated, their involvement in the execution of cell death varies with the stimulus.

Keywords: Apoptosis, calpains, caspases, cortical neurones, staurosporine, camptothecin, hydrogen peroxide, ceramide

Introduction

Neuronal apoptosis is a feature of neurodegeneration (Nicotera, 2000), but the molecular mechanisms underlying this cell death are not completely understood. Apoptotic execution is generally accompanied by the activation of cysteine proteases called caspases, which cleave various cellular substrates in a highly sequence-specific manner (Grutter, 2000; Thornberry & Lazebnik, 1998). Many caspase substrates have been identified to date including poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), retinoblastoma protein and nuclear and cytoskeletal proteins such as lamins and fodrin, respectively (Green, 2000). Cleavage of these substrates by caspases contributes to the characteristic morphological and biochemical changes observed during apoptosis, such as DNA fragmentation, chromatin condensation and cytoskeletal breakdown (Thornberry & Lazebnik, 1998). However, other proteases such as calpains are also involved in apoptosis (Wang, 2000; Yamashima, 2000).

The calpain family consists of two isozymes, μ- and m-calpain based on their calcium requirements (Saido et al., 1994). They are expressed ubiquitously, but unlike caspases, they do not have strict sequence requirements for substrate cleavage. Calpain-mediated proteolysis has been observed in several pathological conditions, including Alzheimer's disease and experimental models of neuronal injury (Ray et al., 2000b; Saito et al., 1993) e.g. during apoptosis of neuroblastoma or PC12 cells (Ray et al., 2000a) and cerebellar granule cells (Nath et al., 1996a) and during neuronal apoptosis induced by rat spinal cord injury (Ray et al., 1999). Calpains and caspases share endogenous substrates such as α-fodrin (Nath et al., 1996b), suggesting they may have similar or overlapping roles in cell death, but the requirement for calpains in different forms of neuronal cell death is not well understood. Calpain activation occurs in response to excitotoxin treatment of primary hippocampal neurones, but reports vary as to the contribution of calpain activity to the cell death (Adamec et al., 1998; Rami et al., 1997). Calpain inhibition reduces cell death, DNA fragmentation and actin cleavage induced by neurotrophic factor withdrawal in embryonic chick ciliary neurones (Villa et al., 1998), but does not prevent cell death induced by high extracellular calcium in SH-SY5Y (McGinnis et al., 1999). Therefore the functional contribution of calpains to neuronal cell death requires clarification.

Neurodegeneration in the cerebral cortex occurs in acute (e.g. ischaemic brain damage) and chronic (e.g Alzheimer's disease) conditions (Anderton, 1997). Primary cerebrocortical neurones (CCN) represent a useful system for examining cerebrocortical neuronal cell death in vitro. The objective of this study was to determine the relative contribution of calpains and caspases to CCN cell death and to establish whether this depends on the stimulus.

Methods

All tissue culture reagents were obtained from Gibco BRL (Paisley, Scotland, U.K.). Boc-Asp-(OMe)-fluoromethylketone (Baf) was obtained from Enzyme Systems Products (Livermore, CA, U.S.A.), calpeptin and Ac-Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp-aminomethyl coumarin (Ac-YVAD-AMC), Ac-Val-Asp-Val-Ala-Asp-aminomethyl coumarin (Ac-VDVAD-AMC), Ac-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-aminomethyl coumarin (Ac-DEVD-AMC), Ac-Val-Glu-Ile-Asp-aminomethyl coumarin (AcVEID-AMC), Ac-Ile-Glu-Thr-Asp-aminomethyl coumarin (Ac-IETD-AMC), and Ac-Leu-Glu-His-Asp-aminomethyl coumarin (Ac-LEHD-AMC) from Alexis (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.), anti-α-fodrin monoclonal antibody from Affiniti Research (Exeter, U.K.) and rabbit anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase from DAKO (Harrow, U.K.). The BCA protein assay kit was obtained from Pierce (Harrow, U.K.). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma (Poole, U.K.) unless stated otherwise.

Neuronal cell culture

Primary cerebrocortical neurones (CCN) were prepared in accordance with previously published protocols (Craighead et al., 2000). Briefly, embryonic (day 18) Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, U.K.) were killed in a CO2 chamber and the cortices removed and placed in dissection medium (Neurobasal™ medium containing B27 supplement with antioxidants and 10% FBS). The cortices were chopped finely using a razor blade and passed through three glass-fired pipettes of sequentially smaller bores. This suspension was centrifuged (150×g, 5 min, room temperature) and resuspended in 20 ml of plating media (Neurobasal™ with B27 supplement plus antioxidants, 2 mM glutamine, 25 μM glutamate, 100 IU ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin). Viable cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion and seeded (7.5×104 cells cm−2) onto 6-/24-well plates, or 8-well immunochambers coated with poly-D-lysine (5 μg cm−2). Half the media was replaced after 5 and 11 days in vitro with maintenance medium (Neurobasal™ with B27 supplement minus antioxidants, 2 mM glutamine, 100 IU ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin). Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 37°C, 5% CO2, 95% air. Cultures consisted of 95% neurones and 5% astrocytes, as assessed by NeuN and glial fibrillary acidic protein immunoreactivity (not shown), respectively. Cells were used for experiments after 11 – 13 days in vitro.

Induction of cell death

Dose-response and time course studies of cell death were carried out (data not shown), and for each stimulus, concentrations and incubation times were selected which induced approximately 50% cell death and loss of viability after 24 h. CCN plated in 24-well plates were treated for 24 h with the broad spectrum kinase inhibitor staurosporine (STS, 0.5 μM), the topoisomerase II inhibitor camptothecin (CMT, 10 μM), the cell permeable lipid analogue C2-ceramide (CER, 50 μM), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 50 μM) or NMDA (100 μM) in the absence or presence of 200 μM Baf (100 mM stock in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO), 30 min pre-treatment) or 30 μM calpeptin (100 mM stock in DMSO, 30 min pre-treatment). All agents were dissolved in DMSO, except NMDA and H2O2, which were dissolved in maintenance medium. The final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.2% in the culture medium and control (vehicle) groups received 0.2% DMSO alone.

Assessment of cell death

Cytotoxicity was evaluated from the release of the cytosolic enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the culture medium by dead and dying cells (Cytotox96 LDH assay, Promega, U.K.). The assay was performed in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 50 μl of culture medium was transferred to 96-well plates, and 50 μl of substrate mix was added to each well and left for 30 min, at room temperature in the dark. The reaction was then stopped by addition of 50 μl 1 mM acetic acid and the absorbance read at 490 nm on a colorimetric plate reader (Dynatech, U.K.). Total LDH release was calculated by incubating untreated cells with 9% Triton X-100 for 45 min (37°C, 5% CO2, 95% air) to induce maximal cell lysis, and LDH release from each treatment group was expressed as a percentage of this value. Background LDH release (media alone) was subtracted from the experimental values. For morphological analysis of apoptotic cell death, cells in 8-well immunochambers treated for 16 h were fixed with 1% methanol-free formaldehyde (15 min, room temperature). Cells were then washed once with PBS and incubated with 10 μg ml−1 Hoechst 33342 in PBS (15 min, room temperature, in the dark). Cells were mounted in gelvatol and viewed under a Leica fluorescence microscope. Cells with condensed and/or marginated chromatin were considered to be apoptotic.

Caspase-assays

Following drug treatment, cells were harvested at 0, 6 and 24 h into lysis buffer (0.5% Nonidet P-40, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) containing the protease inhibitors aprotinin (5 μg ml−1), benzamidine (2.5 mM), phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (0.5 mM), and trypsin inhibitor (25 μg ml−1). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (7200×g, 10 min, 4 °C), and the protein concentration determined using the BCA. Thirty micrograms of protein per sample were incubated (1 h at 30°C) with the fluorogenic caspase substrates Ac-YVAD-AMC, Ac-VDVAD-AMC, Ac-DEVD-AMC, AcVEID-AMC, Ac-IETD-AMC, and Ac-LEHD-AMC (20 mM in DMSO) at a final concentration of 20 μM for each substrate. The reaction was stopped by addition of 100 μl stop solution (176 mM acetic acid and 0.73 mM sodium acetate) on ice, and each sample diluted in 2 ml of dH2O. Fluorescence was then measured at an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm on a Perkin Elmer fluorimeter. Assays were performed in triplicate.

Immunoblotting

Lysates were prepared from control and treated cells as above, and immunoblots for α-fodrin carried out as previously described (Gibson, 1999). Briefly, 20 μg of protein was separated by SDS – PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. α-fodrin was detected using an anti-α-fodrin monoclonal antibody (diluted 1 : 10,000 in 5% skimmed milk powder in PBS-0.02% Tween-20). Bound, primary antibody was visualised using a rabbit-anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1 : 4000 in 5% milk in PBS-Tween) followed by reaction with a chemiluminescent substrate (Amersham, U.K.).

Data analysis

All data are presented as mean±s.e.mean and were analysed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with student Newman-Keuls. Results were considered significant at P<0.05.

Results

Caspase activation in CCN is stimulus-dependent

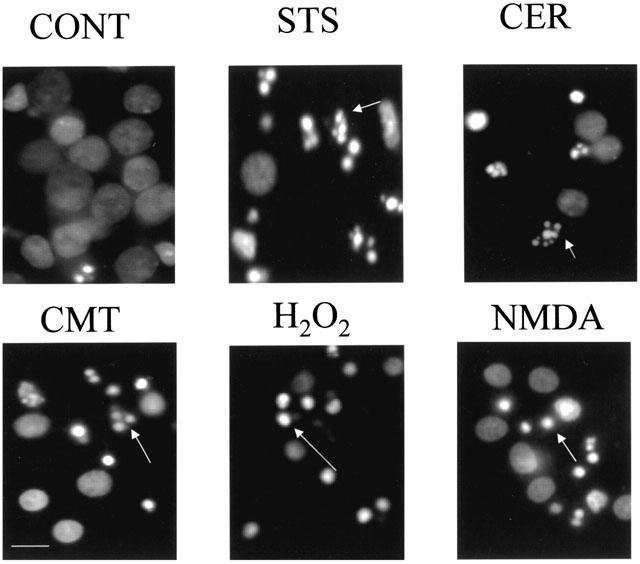

Nuclear staining of CCN treated with STS (0.5 μM), CER (50 μM), or CMT (10 μM) revealed a marginated chromatin morphology typical of apoptosis. H2O2 (50 μM) or NMDA (100 μM) treated cells did not exhibit chromatin margination, but instead displayed only a shrunken, condensed nuclear morphology (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Nuclear morphological changes following 16 h treatment with staurosporine (STS), camptothecin (CMT), C2-ceramide (CER), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA). Cultures were fixed with 1% methanol-free formaldehyde and then incubated with 10 μg ml−1 Hoechst 33342. Nuclei with marginated (STS, CMT, CER) or condensed (H2O2, NMDA) chromatin are indicated by white arrows. Scale bar=20 μm.

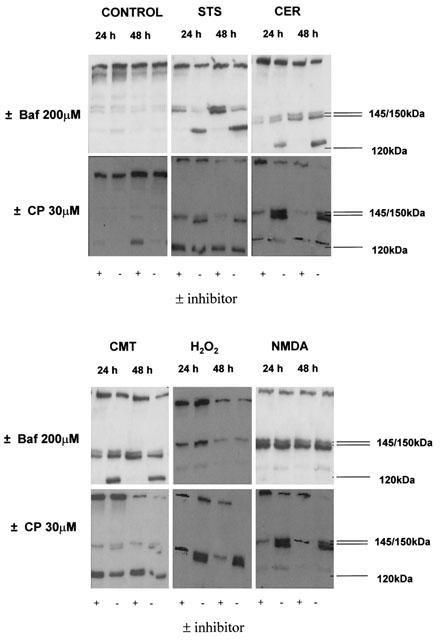

α-fodrin cleavage was examined to investigate whether caspases are activated in CCN dying in response to different agents. Western blot analysis revealed that STS, CER and CMT induced cleavage of full length α-fodrin to the caspase-generated 120 kDa fragment 24 and 48 h after treatment. Treatment of cells with NMDA or H2O2 did not induce cleavage of α-fodrin to the 120 kDa product either 24 or 48 h after treatment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Profile of α-fodrin cleavage during CCN cell death is stimulus-dependent. Cells were treated for 24 and 48 h with staurosporine (STS), camptothecin (CMT), C2-ceramide (CER), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) in the presence or absence of 200 μM Baf, or 30 μM calpeptin (CP) and total protein extracted. 20 μg of protein was separated by SDS – PAGE and α-fodrin detected using an anti-α-fodrin primary antibody. α-fodrin was cleaved to a 145/150 kDa doublet (by caspases/calpains) and a 120 kDa fragment (by caspases) during CCN cell death with all inducers except H2O2, which induced the appearance of the 145/150 kDa doublet alone. Baf completely abolished the appearance of the 120 kDa cleavage product. Calpeptin reduced the appearance of the 145 kDa cleavage product. Figures are representative Western blots chosen from three separate experiments.

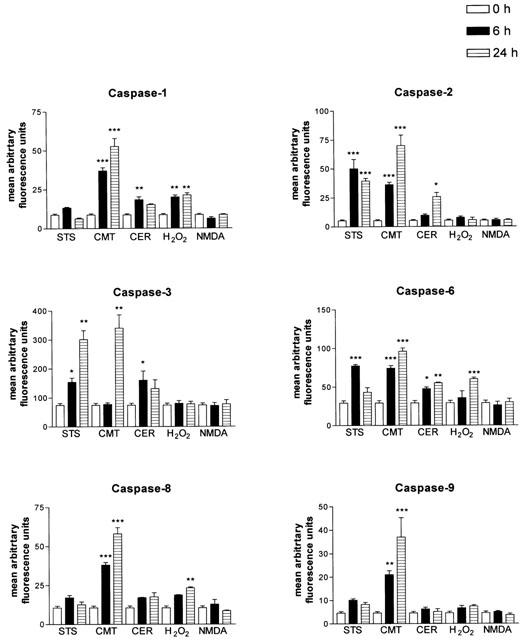

To examine in greater detail the caspases activated during CCN cell death, fluorogenic peptide substrates, Ac-YVAD-AMC, Ac-VDVAD-AMC, Ac-DEVD-AMC, AcVEID-AMC, Ac-IETD-AMC, and Ac-LEHD-AMC were used to assay caspase -1, -2, -3, -6, -8, and -9 activity respectively, in cytosolic extracts of treated CCN. These substrates were chosen on the basis of their optimal caspase specificities (Talanian et al., 1997; Thornberry et al., 1997). Treatment of CCN with STS significantly increased the cleavage of substrates for caspases -2, -3 and -6 at 6 h and caspases -2 and -3 at 24 h relative to control (0 h) (Figure 3). CER significantly increased cleavage of substrates for caspases -1 and -6 at 6 h and caspases -2 and -6 at 24 h relative to control (Figure 3). CMT significantly increased cleavage of substrates for caspases -1, -2, -6, -8 and -9 at 6 h and caspases -1, -3, -6, -8 and -9 at 24 h (Figure 3), and H2O2 induced significant increases in cleavage of substrates for caspase-1 at 6 h and caspases -1, -6 and -8 at 24 h (Figure 3). NMDA did not significantly induce the cleavage of any of the fluorogenic caspase substrates tested (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Induction of caspase activity in CCN primary cultures treated with different inducers of cell death at 0, 6 and 24 h post-treatment, using the peptide substrates Ac-DEVD-AMC, Ac-YVAD-AMC, Ac-VDVAD-AMC, Ac-DEVD-AMC, AcVEID-AMC, Ac-IETD-AMC, and Ac-LEHD-AMC to assay for caspases -1, -2, -3, -6, -8, and -9 respectively, in cytosolic extracts of treated CCN. Thirty micrograms of protein were used for each assay. Data are presented as mean arbitrary fluorescence units±s.e.mean from four or five independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs control one-way ANOVA with student Newman-Keuls.

Calpains are activated during CCN cell death induced by a variety of death signals

Activation of calpains determined by α-fodrin cleavage to a 145/150 kDa doublet was observed during CCN cell death in response to all the agents tested. STS induced the cleavage of α-fodrin to a caspase/calpain-generated 145 – 150 kDa doublet at 24 h, with an increase in cleavage at 48 h (Figure 2). Treatment of CCN with CER, CMT, H2O2 or NMDA for 24 and 48 h also induced the cleavage of α-fodrin into a 145/150 kDa doublet (Figure 2).

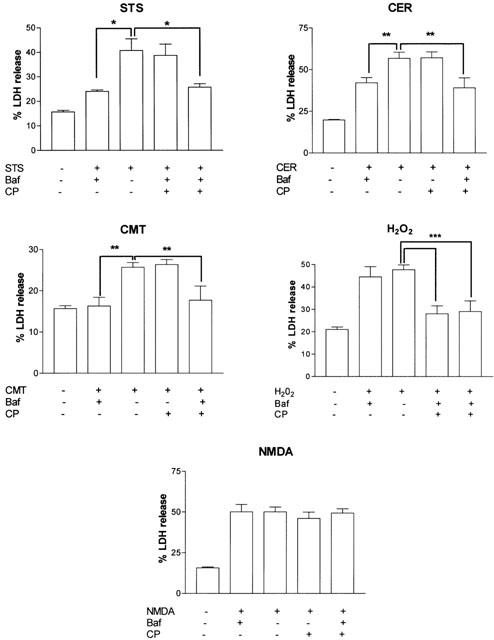

Requirement for caspases or calpains in cell death is dependent on the stimulus

To examine the functional role of caspases and calpains in CCN death, pharmacological inhibitors of the enzymes were employed and cell death analysed. The pan-caspase inhibitor Baf significantly reduced cell death induced by STS (40.6±4.8 vs 24.0±1.3), CER (56.7±3.7 vs 42.3±3.2), and CMT (29.7±1.2 vs 16.3±2.1) (Figure 4) and prevented the cleavage of α-fodrin to the 120 kDa band in response to the above agents (Figure 2). Pre-treatment with calpeptin had no effect on cell death induced by these agents, although calpeptin did reduce the appearance of the 145 kDa portion of the 145/150 kDa α-fodrin doublet (Figure 2). Furthermore, co-treatment of cells with calpeptin and Baf resulted in a cell death profile not significantly different from Baf alone (Figure 4). In contrast, calpeptin, but not Baf, suppressed the cell death induced by H2O2 (47.7±2.2 vs 28.7±3.5) (Figure 4). Calpeptin also reduced the appearance of the 145 kDa α-fodrin cleavage product in H2O2-treated CCN lysates (Figure 2). Co-treatment of cultures with Baf and calpeptin did not significantly alter the H2O2-induced cell death relative to calpeptin alone (Figure 4). Pre-treatment of CCN with Baf or calpeptin alone, or in combination, did not alter the cell death induced by NMDA (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Involvement of caspases and calpains in CCN cell death is stimulus-dependent. Effect of caspase (Baf), calpain (calpeptin (CP)) or combined caspase/calpain inhibition on cell death after 24 h treatment with staurosporine (STS), camptothecin (CMT), C2-ceramide (CER), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA). Data are presented as mean percent total LDH release (percent of Triton-X-100 lysed cultures)±s.e.mean from five separate experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 using one way ANOVA with student-Newman-Keuls.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to examine the relative contributions of calpains and caspases to primary cerebrocortical neuronal death in response to different agents. Primary cortical neuronal cultures underwent cell death when treated with the kinase inhibitor staurosporine, the topoisomerase inhibitor camptothecin, the lipid second messenger C2-ceramide or the excitotoxin NMDA and when subjected to oxidative stress by exposure to H2O2.

Caspases and calpains share substrates such as α-fodrin (Cryns et al., 1996). In order to detect caspase and calpain activity in dying CCN, cleavage of α-fodrin and fluorogenic caspase substrates was examined. To our knowledge, the results in this paper represent the first comprehensive analysis of activation of multiple caspases and calpain in CCN death. STS, CMT and CER induced stimulus- and substrate-specific temporal profiles of multiple caspase activation together with chromatin condensation and calpain activation. The relative activation of calpain and caspases varied slightly between stimuli, with STS or CER predominantly activating caspases, CMT both caspases and calpains, and H2O2 or NMDA predominantly calpains. Caspase-dependent CCN cell death in response to STS, CMT and CER has been reported by several groups (Koh et al., 1995; MacManus et al., 1997). Calpain activation has been reported in STS-treated SH-SY5Y and Jurkat T-cells (Wang et al., 1998a, 1998b), but in STS-treated CCN there was no cleavage of the endogenous inhibitor of calpains (Tremblay et al., 2000). We show here that calpains are activated by STS in CCN. The disparity between these findings may be due to the earlier time-point (18 h) used in the previous study (Tremblay et al., 2000), or the fact that calpastatin and not α-fodrin cleavage was examined. Calpain activation in CCN in response to other agents has not been previously characterized. We have shown that calpain-dependent α-fodrin cleavage occurs during STS, CMT- or CER-induced CCN apoptosis. However, the cell death induced by STS, CMT or CER was not inhibited by calpeptin. This suggests that calpain activity is not required for cellular execution in response to these stimuli in CCN. Pre-treatment of CCN with calpeptin did however reduce the appearance of the 145 kDa α-fodrin cleavage product, but not the 150 kDa product (which can be generated by either caspases or calpain) demonstrating that calpeptin was effectively inhibiting calpain in this system in response to STS, CER, or CMT. These data are supported by the finding that calpain inhibitors provide only modest, or no protection against death in certain cell lines in response to STS (Nath et al., 1996a) or CMT (Wood & Newcomb, 1999), consistent with a non-essential role for calpain in caspase-dependent cell death in CCN.

Calpains are calcium-dependent proteases, activated by elevated intracellular calcium (Murachi, 1984). In neurones, elevated intracellular calcium is associated with excitotoxin-induced cell death (Sattler & Tymianski, 2000), but STS, CER or CMT, to our knowledge, have not been reported to induce rises in intracellular calcium levels. Caspases can activate calpains in certain systems (Wood & Newcomb, 1999); however, Baf treatment of CCN did not prevent the generation of the 145/150 kDa fragment in STS-, CMT- or CER-treated cells, suggesting calpain activation is independent of caspases. Conversely, calpains can negatively regulate caspase activation in hippocampal neurones (Lankiewicz et al., 2000), so that inhibition of calpains stimulates caspase activation. Indeed a small increase in the caspase-specific 120 kDa fragment was observed in calpeptin-treated cells, but only in response to CMT.

H2O2 induces cell death and nuclear changes in PC12 cells in a calpain-dependent manner (Ray et al., 2000a). In the present study, cell death induced by H2O2 was accompanied by caspase-1, -6 and -8 but not caspase-3 activity and by nuclear shrinkage and α-fodrin cleavage into the 145/150 kDa doublet. Calpain but not pan-caspase inhibition reduced the cell death induced by H2O2, suggesting that whilst H2O2-induced cell death was accompanied by nuclear shrinkage and activation of caspases, the cell death was calpain but not caspase-dependent. Additionally, although H2O2 induced caspase-1, -6 and -8 activation, α-fodrin was not cleaved to the caspase-3-generated 120 kDa fragment. Similar results were obtained in BL30A cell extracts where caspase-6 cleaves α-fodrin to the alternative 150 but not 120 kDa fragment (Waterhouse et al., 1998). Furthermore, immunodepletion of caspases -6 or -7, but not caspase-3 has no effect on α-fodrin cleavage, or nuclear morphological changes in Jurkat T-cells (Slee et al., 2001). Overall however, these findings agree with previous reports that specific biochemical or morphological hallmarks of apoptosis are detectable in the absence of caspase-3-type activation (Nicotera et al., 1999). The results also point to a pivotal role for caspase-3-type proteases in determining whether cell death can be prevented by pharmacological inhibition of caspases by Baf in CCN.

There is increasing evidence that cathepsins are involved in apoptotic execution (Isahara et al., 1999). YVAD may be cleaved by cathepsins as well as caspase-1 (Gray et al., 2001; Isahara et al., 1999) and therefore it is therefore possible that this group of enzymes is also activated in response to CMT, CER and H2O2. There is little evidence regarding the involvement of caspase-1 in the neuronal cell death induced by CMT, CER or H2O2, although early cleavage of YVAD following STS treatment has been demonstrated in primary hippocampal neurones (Krohn et al., 1998).

The role of calpains in excitotoxin-induced neuronal cell death is currently unclear. In the present study, NMDA treatment did not result in cleavage of any of the fluorogenic caspase substrates tested, but did cleave α-fodrin to the 145/150 kDa doublet and induced nuclear shrinkage, suggestive of apoptosis. NMDA-induced cell death was not affected by pan-caspase or calpain inhibition. These findings suggest that nuclear morphological changes can occur in the absence of caspase and calpain activity during NMDA-induced cell death of CCN. This is consistent with reports that calpain inhibition is ineffective against excitotoxin-induced cell death in CCN, hippocampal neurones (Adamec et al., 1998) or cerebellar granule cells (Manev et al., 1991). However, calpains are involved in neurite regeneration following a neurotoxic insult (Faddis et al., 1997). Our finding that calpeptin failed to reduce cell death induced by all stimuli except H2O2 suggests that calpain activation could be a regenerative response to a neurotoxic stimulus, and not a critical step in the cell death pathway itself.

Caspases and calpains may behave synergistically in certain forms of cell death. For example, during hippocampal neuronal apoptosis, combined caspase and calpain inhibition affords greater protection than inhibition of either family of proteases alone (Waterhouse et al., 1998). However, combined caspase and calpain inhibition did not significantly alter the cell death or chromatin condensation induced by STS, CMT or CER relative to caspase inhibition alone, indicating that calpains do not have a synergistic role in caspase-dependent death in CCN. Combined calpeptin/Baf treatment did not further reduce the cell death in response to H2O2 compared to calpeptin alone, further supporting the role of calpains and not caspases in H2O2-induced neuronal cell death. Cell death induced by NMDA was unaffected by combined caspase/calpain inhibition. These analyses of caspase and calpain activation in total cell populations cannot discriminate the enzyme activity profiles of individual cells: multiple caspases and calpain may be activated in one cell or different enzymes in different cells. However the absence of reduced cell death with Baf plus calpeptin suggests that whichever scenario occurs, the cell death remains caspase-dependent (STS, CER, CMT) or calpain-dependent (H2O2).

The results presented here show that specific caspases are activated by different stimuli, and that the functional involvement of calpains and caspases in CCN cell death is stimulus-dependent: although calpains are activated during both caspase-dependent and -independent cell death, calpains do not contribute to caspase-dependent death of CCN.

Acknowledgments

J.D. Moore is funded by the BBSRC, N.J. Rothwell and R.M. Gibson by the Medical Research Council.

Abbreviations

- Ac-DEVD-AMC

Ac-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-aminomethyl coumarin

- Ac-IETD-AMC

Ac-Ile-Glu-Thr-Asp-aminomethyl coumarin

- Ac-LEHD-AMC

Ac-Leu-Glu-His-Asp-aminomethyl coumarin

- Ac-VDVAD-AMC

Ac-Val-Asp-Val-Ala-Asp-aminomethyl coumarin

- AcVEID-AMC

Ac-Val-Glu-Ile-Asp-aminomethyl coumarin

- Ac-YVAD-AMC

Ac-Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp-aminomethyl coumarin

- Baf

Boc-Asp-(OMe)-Fluoromethylketone

- CCN

cerebrocortical neurones/neuronal

- CER

ceramide

- CMT

camptothecin

- CP

calpeptin

- DMSO

dimethylsulphoxide

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- PARP

poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- STS

staurosporine

References

- ADAMEC E., BEERMANN M.L., NIXON R.A. Calpain I activation in rat hippocampal neurons in culture is NMDA receptor selective and not essential for excitotoxic cell death. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1998;54:35–48. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERTON B.H. Changes in the ageing brain in health and disease. Philos Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 1997;352:1781–1792. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRAIGHEAD M.W., BOUTIN H., MIDDLEHURST K.M., ALLAN S.M., BROOKS N., KIMBER I., ROTHWELL N.J. Influence of corticotrophin releasing factor on neuronal cell death in vitro and in vivo. Brain Res. 2000;881:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRYNS V.L., BERGERON L., ZHU H., LI H., YUAN J. Specific cleavage of alpha-fodrin during Fas- and tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis is mediated by an interleukin-1beta-converting enzyme/Ced-3 protease distinct from the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase protease. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:31277–31282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FADDIS B.T., HASBANI M.J., GOLDBERG M.P. Calpain activation contributes to dendritic remodeling after brief excitotoxic injury in vitro. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:951–959. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00951.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIBSON R.M. Caspase activation is downstream of commitment to apoptosis of Ntera-2 neuronal cells. Exp. Cell. Res. 1999;251:203–212. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAY J., HARAN M.M., SCHNEIDER K., VESCE S., RAY A.M., OWEN D., WHITE I.R., CUTLER P., DAVIS J.B. Evidence that inhibition of cathepsin-b contributes to the neuroprotective properties of caspase inhibitor tyr-val-ala-asp-chloromethyl ketone. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:32750–32755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN D.R. Apoptotic pathways: paper wraps stone blunts scissors. Cell. 2000;102:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRUTTER M.G. Caspases: key players in programmed cell death. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:649–655. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISAHARA K., OHSAWA Y., KANAMORI S., SHIBATA M., WAGURI S., SATO N., GOTOW T., WATANABE T., MOMOI T., URASE K., KOMINAMI E., UCHIYAMA Y. Regulation of a novel pathway for cell death by lysosomal aspartic and cysteine proteinases. Neuroscience. 1999;91:233–249. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00566-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOH J.Y., WIE M.B., GWAG B.J., SENSI S.L., CANZONIERO L.M., DEMARO J., CSERNANSKY C., CHOI D.W. Staurosporine-induced neuronal apoptosis. Exp. Neurol. 1995;135:153–159. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1995.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KROHN A.J., PREIS E., PREHN J.H. Staurosporine-induced apoptosis of cultured rat hippocampal neurons involves caspase-1-like proteases as upstream initiators and increased production of superoxide as a main downstream effector. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:8186–8197. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08186.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANKIEWICZ S., MARC L.C., TRUC B.N., KROHN A.J., POPPE M., COLE G.M., SAIDO T.C., PREHN J.H. Activation of calpain I converts excitotoxic neuron death into a caspase-independent cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:17064–17071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.22.17064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACMANUS J.P., RASQUINHA I., BLACK M.A., LAFERRIERE N.B., MONETTE R., WALKER T., MORLEY P. Glutamate-treated rat cortical neuronal cultures die in a way different from the classical apoptosis induced by staurosporine. Exp. Cell. Res. 1997;233:310–320. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANEV H., FAVARON M., SIMAN R., GUIDOTTI A., COSTA E. Glutamate neurotoxicity is independent of calpain I inhibition in primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells. J. Neurochem. 1991;57:1288–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb08292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCGINNIS K.M., WANG K.K., GNEGY M.E. Alterations of extracellular calcium elicit selective modes of cell death and protease activation in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. J. Neurochem. 1999;72:1853–1863. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0721853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURACHI T. Calcium-dependent proteinases and specific inhibitors: calpain and calpastatin. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 1984;49:149–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATH R., RASER K.J., MCGINNIS K., NADIMPALLI R., STAFFORD D., WANG K.K. Effects of ICE-like protease and calpain inhibitors on neuronal apoptosis. Neuroreport. 1996a;8:249–255. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199612200-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATH R., RASER K.J., STAFFORD D., HAJIMOHAMMADREZA I., POSNER A., ALLEN H., TALANIAN R.V., YUEN P., GILBERTSEN R.B., WANG K.K. Non-erythroid alpha-spectrin breakdown by calpain and interleukin 1 beta-converting-enzyme-like protease(s) in apoptotic cells: contributory roles of both protease families in neuronal apoptosis. Biochem J. 1996b;319:683–690. doi: 10.1042/bj3190683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICOTERA P. Caspase requirement for neuronal apoptosis and neurodegeneration. IUBMB Life. 2000;49:421–425. doi: 10.1080/152165400410272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICOTERA P., LEIST M., FERRANDO-MAY E. Apoptosis and necrosis: different execution of the same death. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 1999;66:69–73. doi: 10.1042/bss0660069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMI A., FERGER D., KRIEGLSTEIN J. Blockade of calpain proteolytic activity rescues neurons from glutamate excitotoxicity. Neurosci. Res. 1997;27:93–97. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(96)01123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAY S.K., FIDAN M., NOWAK M.W., WILFORD G.G., HOGAN E.L., BANIK N.L. Oxidative stress and Ca2+influx upregulate calpain and induce apoptosis in PC12 cells. Brain Res. 2000a;852:326–334. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAY S.K., MATZELLE D.D., WILFORD G.G., HOGAN E.L., BANIK N.L. Increased calpain expression is associated with apoptosis in rat spinal cord injury: calpain inhibitor provides neuroprotection. Neurochem. Res. 2000b;25:1191–1198. doi: 10.1023/a:1007631826160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAY S.K., WILFORD G.G., MATZELLE D.C., HOGAN E.L., BANIK N.L. Calpeptin and methylprednisolone inhibit apoptosis in rat spinal cord injury. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;890:261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAIDO T.C., SORIMACHI H., SUZUKI K. Calpain: new perspectives in molecular diversity and physiological-pathological involvement. FASEB J. 1994. pp. 814–822. [PubMed]

- SAITO K., ELCE J.S., HAMOS J.E., NIXON R.A. Widespread activation of calcium-activated neutral proteinase (calpain) in the brain in Alzheimer disease: a potential molecular basis for neuronal degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:2628–2632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SATTLER R., TYMIANSKI M. Molecular mechanisms of calcium-dependent excitotoxicity. J. Mol. Med. 2000;78:3–13. doi: 10.1007/s001090000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SLEE E.A., ADRAIN C., MARTIN S.J. Executioner caspase-3, -6, and -7 perform distinct, non-redundant roles during the demolition phase of apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:7320–7326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TALANIAN R.V., QUINLAN C., TRAUTZ S., HACKETT M.C., MANKOVICH J.A., BANACH D., GHAYUR T., BRADY K.D., WONG W.W. Substrate specificities of caspase family proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:9677–9682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORNBERRY N.A., LAZEBNIK Y. Caspases: enemies within. Science. 1998;281:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORNBERRY N.A., RANO T.A., PETERSON E.P., RASPER D.M., TIMKEY T., GARCIA-CALVO M., HOUTZAGER V.M., NORDSTROM P.A., ROY S., VAILLANCOURT J.P., CHAPMAN K.T., NICHOLSON D.W. A combinatorial approach defines specificities of members of the caspase family and granzyme B. Functional relationships established for key mediators of apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:17907–17911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TREMBLAY R., CHAKRAVARTHY B., HEWITT K., TAUSKELA J., MORLEY P., ATKINSON T., DURKIN J.P. Transient NMDA receptor inactivation provides long-term protection to cultured cortical neurons from a variety of death signals. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7183–7192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07183.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VILLA P.G., HENZEL W.J., SENSENBRENNER M., HENDERSON C.E., PETTMANN B. Calpain inhibitors, but not caspase inhibitors, prevent actin proteolysis and DNA fragmentation during apoptosis. J. Cell. Sci. 1998;111:713–722. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.6.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG K.K. Calpain and caspase: can you tell the difference. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:20–26. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG K.K., POSMANTUR R., NADIMPALLI R., NATH R., MOHAN P., NIXON R.A., TALANIAN R.V., KEEGAN M., HERZOG L., ALLEN H. Caspase-mediated fragmentation of calpain inhibitor protein calpastatin during apoptosis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998a;356:187–196. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG K.K., POSMANTUR R., NATH R., MCGINNIS K., WHITTON M., TALANIAN R.V., GLANTZ S.B., MORROW J.S. Simultaneous degradation of alphaII- and betaII-spectrin by caspase 3 (CPP32) in apoptotic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998b;273:22490–22497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATERHOUSE N.J., FINUCANE D.M., GREEN D.R., ELCE J.S., KUMAR S., ALNEMRI E.S., LITWACK G., KHANNA K., LAVIN M.F., WATTERS D.J. Calpain activation is upstream of caspases in radiation-induced apoptosis. Cell. Death. Differ. 1998;5:1051–1061. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOOD D.E., NEWCOMB E.W. Caspase-dependent activation of calpain during drug-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:8309–8315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMASHIMA T. Implication of cysteine proteases calpain, cathepsin and caspase in ischemic neuronal death of primates. Prog. Neurobiol. 2000;62:273–295. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]