Abstract

The neurosteroid pregnenolone sulphate (PS) potentiates N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor mediated responses in various neuronal preparations. The NR1 subunit can combine with NR2A, NR2B, NR2C, or NR2D subunits to form functional receptors. Differential NR2 subunit expression in brain and during development raises the question of how the NR2 subunit influences NMDA receptor modulation by neuroactive steroids.

We examined the effects of PS on the four diheteromeric NMDA receptor subtypes generated by co-expressing the NR1100 subunit with each of the four NR2 subunits in Xenopus oocytes. Whereas PS potentiated NMDA-, glutamate-, and glycine-induced currents of NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B receptors, it was inhibitory at NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors.

In contrast, pregnanolone sulphate (3α5βS), a negative modulator of the NMDA receptor that acts at a distinct site from PS, inhibited all four subtypes, but was approximately 4 fold more potent at NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D than at NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B receptors.

These findings demonstrate that residues on the NR2 subunit are key determinants of modulation by PS and 3α5βS. The modulatory effects of PS, but not 3α5βS, on dose-response curves for NMDA, glutamate, and glycine are consistent with a two-state model in which PS either stabilizes or destabilizes the active state of the receptor, depending upon which NR2 subunit is present.

The selectivity of sulphated steroid modulators for NMDA receptors of specific subunit composition is consistent with a neuromodulatory role for endogenous sulphated steroids. The results indicate that it may be possible to develop therapeutic agents that target steroid modulatory sites of specific NMDA receptor subtypes.

Keywords: NMDA, neurosteroid, neuroactive steroid, pregnenolone sulphate, pregnanolone sulphate, NR2

Introduction

Pregnenolone sulphate (PS), a relatively abundant sulphated neurosteroid (Corpéchot et al., 1983), potentiates the activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) sensitive glutamate receptors (Bowlby, 1993; Wu et al., 1991; Yaghoubi et al., 1998), and may act as an endogenous neuromodulator or neurotransmitter. PS, injected intraperitoneally, increases the convulsant potency of NMDA in mice (Maione et al., 1992) and, when injected intracerebroventricularly, relieves memory deficits in rats injected with the NMDA receptor antagonists CPP (Mathis et al., 1994) and D-AP5 (Mathis et al., 1996). Moreover, PS enhances memory and cognitive performance in rats and mice (Flood et al., 1992; Ladurelle et al., 2000; Meziane et al., 1996; Pallares et al., 1998).

A number of other sulphated steroids exhibit activity as NMDA receptor modulators. Structure-activity studies reveal that a sulphate group at the C3 position is an important determinant of modulatory activity at NMDA receptors (Irwin et al., 1994; Park-Chung et al., 1997), and that other negatively charged substituents can substitute for sulphate (Weaver et al., 2000). Whereas PS typically enhances the neuronal NMDA response, pregnanolone sulphate (3α-hydroxy-5β-pregnan-20-one sulphate; 3α5βS) also modulates NMDA receptors, but in the opposite direction, inhibiting, rather than enhancing, NMDA-induced currents (Park-Chung et al., 1994). 3α5βS is neuroprotective against NMDA excitotoxicity in rat hippocampal cultures, and pregnanolone hemisuccinate, a synthetic analogue of 3α5βS, reduces ischaemic damage in rat brain following middle cerebral artery occlusion, antagonizes NMDA-induced seizures and is analgesic against late-stage formalin induced pain in mice (Weaver et al., 1997).

Interaction studies demonstrate that the site of action of 3α5βS is distinct from that responsible for potentiation of the NMDA response by PS (Park-Chung et al., 1997), indicating the presence of at least two distinct steroid modulatory sites, with the geometry of the steroid nucleus determining activity at the two sites. Inhibition by 3α5βS is mediated by a site that favours the ‘bent' steroid nucleus of 3α5βS, whereas potentiation by PS is attributed to a site that favours the more planar pregnene steroid nucleus (Weaver et al., 2000).

Evidence indicates that a functional NMDA receptor requires coassembly of the NR1 subunit with at least one NR2 subunit (McIlhinney et al., 1996). Eight splice variants of the single NR1 gene have been identified, whereas four different genes encode the NR2A, NR2B, NR2C and NR2D subunits (for review see Mori & Mishina, 1995). The NR1 subunit is broadly expressed throughout the CNS (Akazawa et al., 1994; Laurie et al., 1997; Petralia et al., 1994), whereas NR2 subunits display distinct, although overlapping, expression patterns, raising the question of whether the NR2 subunit influences modulation of the NMDA receptor by steroids.

In the present study, we examined the effects of PS and 3α5βS on the four diheteromeric receptor subtypes generated by co-expressing the NR1100 subunit in Xenopus oocytes with each of the four NR2 subunits. Our results demonstrate that the NR2 subunit plays a critical role in determining the direction of modulation by PS, with NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B receptors being potentiated by PS, while NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors are inhibited. In contrast, 3α5βS is inhibitory with all subunit combinations, but its potency as an inhibitor of the NMDA response is influenced by the choice of NR2 subunit.

Methods

Preparation of RNA

Plasmids containing the NR1100 (NR1G) and NR2A cDNA inserts were kindly provided by Dr Nakanishi (Kyoto University Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan). Plasmids containing the NR2B, NR2C and NR2D cDNA inserts were kindly provided by Dr P. Seeburg (Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany). Plasmids were linearized with appropriate restriction enzyme prior to in vitro transcription using the Message Machine kit (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX, U.S.A.).

NMDA receptor expression in Xenopus oocytes

Female, oocyte-positive Xenopus laevis frogs were purchased from Xenopus I (Dexter, MI, U.S.A.). Following 45 min of 0.15% Tricaine anaesthesia, ovarian sections containing the follicular oocytes were removed from the frog through a lateral abdominal incision and were immediately placed in a calcium-free solution (in mM: NaCl 96, MgCl2 1, KCl 2, HEPES 50, pyruvate 2.5, 0.1 mg ml−1 gentamycin, pH 7.4). Following 1.5 – 2 h incubation in 0.2% collagenase (type II, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) at room temperature, individual defolliculated Dumont stage V and VI oocytes were transferred to an incubator and maintained overnight in Barth's solution (in mM: NaCl 84, NaHCO3 2.4, MgSO4 0.82, KCl 1, Ca(NO3)2 0.33, CaCl2 0.41, Tris/HCl 7.5, pyruvate 2.5, 0.1 mg ml−1 gentamycin, pH 7.4) at 18 – 20°C. Oocytes were injected with 50 nL of RNA solutions using an electronic microinjector (Drummond Inc., Broomall, PA, U.S.A.). The transcripts were injected at a ratio of 0.125/1.25 ng mRNA per oocyte for NR1/NR2A receptors and 0.5/5 ng mRNA per oocyte for NR1/NR2B, NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors. The injected oocytes were used for experiments following 1 – 5 days of incubation in Barth's solution at 18 – 20°C.

Electrophysiology

Measurements of ion currents from oocytes expressing NMDA receptors were performed using an Axoclamp-2A voltage clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Inc., Foster City, CA, U.S.A.) in two-electrode voltage clamp mode. The microelectrodes were fabricated from borosilicate glass capillaries with a programmed puller (Sutter Instrument Co., CA, U.S.A.). Microelectrode resistance was 1 – 3 MΩ when filled with 3 M KCl. The oocyte recording chamber was continuously perfused with Mg2+-free Ba-Ringer solution (in mM: NaCl 96, KCl 2, BaCl2 1.8, HEPES 5). Ba-Ringer was used to prevent NMDA receptorcurrents from being complicated by activation of Ca2+ dependent Cl− channels (Leonard & Kelso, 1990). Potentiation of the NMDA-induced current of NR1100/NR2A receptors by PS in Ba-Ringer tended to be less than previously observed with Ca2+-containing solution (Yaghoubi et al., 1998), possibly reflecting a nonlinear contribution of Ca2+ dependent Cl− channels to the NMDA induced current.

Except where otherwise stated, oocytes were clamped at a holding potential of −70 mV during data acquisition. The membrane current was filtered at 500 Hz and sampled at 100 Hz. Drugs were applied using a gravity-driven external perfusion system. The working volume of the recording chamber was 30 μl and the rate of the perfusion was 50 μl s−1. The drug application lasted 10 s and was followed by 60 s wash. Data acquisition and external perfusion were controlled using custom-written software implemented in the SuperScope II development environment (GW Instruments, MA, U.S.A.). All experiments were performed at room temperature of 22 – 24°C. A response to a standard concentration of NMDA was obtained before and after each concentration of agonist, and agonist responses were normalized to this internal standard to eliminate variation due to differences in expression among oocytes or run-down during the experiment. Oocytes that showed pronounced run-down of the response to the NMDA standard were rejected. Peak agonist-induced currents in the presence of steroid were expressed relative to the adjacent responses to agonist alone.

Data Analysis

Concentration-response data were initially analysed by nonlinear regression using the logistic equation response= Emax(1 + (EC50/c)nH)−1, where c is concentration, Emax is the maximum response, nH is the Hill coefficient. The data are presented as mean±s.e.mean. EC50 values are averaged as logarithms (de lean et al., 1978)±the s.e.mean of the log EC50. Hence, the reported mean EC50 values are geometric means.

Modelling of NMDA receptor modulation by PS

Concentration-response data for PS were fitted to a two-state model with two binding sites each for glutamate/NMDA, glycine, and PS. Activation is assumed to be concerted (i.e. the entire receptor is either in the active or inactive state). The two binding sites for each ligand are assumed to have the same affinity. This model has the equilibrium state equation,

where p′ is the fraction of receptors activated, Kligand and K′ligand are the dissociation constants for binding of the indicated ligand to the inactive and active states, respectively, and M is the resting ratio of active to inactive receptors. When NMDA instead of glutamate is used to activate the receptor, [NMDA], KNMDA, and K′NMDA replace [Glu], KGlu, and K′Glu. To fit this equation to the experimental data, one additional parameter, max, was required. This is a scaling factor which is equivalent to Imax Istd−1, the ratio of the maximum possible current (i.e. if all receptors were simultaneously in the active state) to the current induced by the 200 μM NMDA+10 μM glycine internal standard (relative current=p′max). The model was simultaneously fitted to the full set of concentration response data for each subunit combination by minimizing the sum of squared deviations from the experimental data using Microsoft Excel.

Chemicals

Steroids were obtained from Steraloids, Inc. (Wilton, NH, U.S.A.). Other compounds were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Steroid stocks were prepared in DMSO and diluted into recording medium (final DMSO concentration 0.5%). Other solutions also contained 0.5% DMSO.

Results

NMDA receptor expression in Xenopus oocytes

To investigate the influence of NMDA receptor subunit composition on the modulatory effects of neuroactive steroids, mRNA coding for the NR1100 subunit was coinjected into Xenopus laevis oocytes along with mRNA coding for either the NR2A, NR2B, NR2C, or NR2D subunit. All four diheteromeric subunit combinations resulted in expression of functional NMDA receptors 1 – 5 days after injection, as indicated by an inward current in response to application of 80 μM NMDA plus 10 μM glycine.

Dependence of PS modulation upon subunit composition

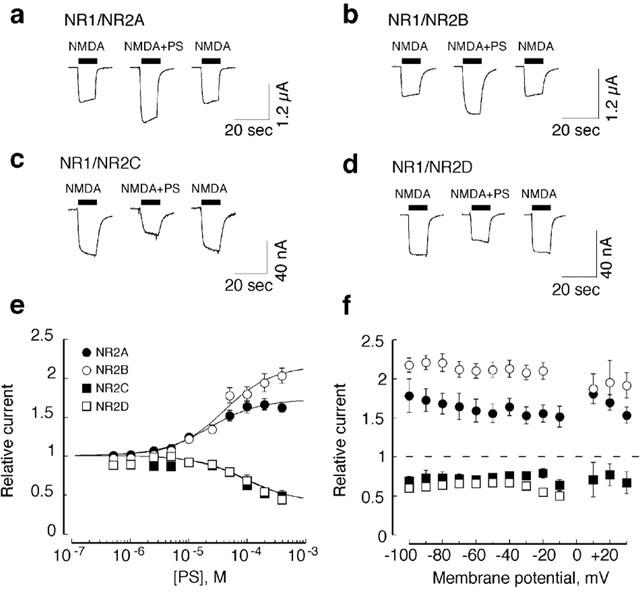

As shown in Figure 1, the choice of NR2 subunit dictates the direction of modulation by PS. Because the NMDA EC50 differs for the various subunit combinations, we compared the modulatory effects of PS using a concentration of NMDA close to its EC50 for each subunit combination (80 μM for NR1/NR2A, 25 μM for NR1/NR2B and NR1/NR2C, and 10 μM for NR1/NR2D). Glycine was present at a saturating concentration (10 μM). In oocytes expressing NR1/NR2A receptors, the NMDA induced current is increased by 62±8% (n=8) in the presence of 100 μM PS. Similarly, with oocytes expressing NR1/NR2B receptors, the NMDA-induced current is enhanced by 78±9% (n=4) in the presence of 100 μM PS. In contrast, NMDA responses of oocytes expressing NR1/NR2C or NR1/NR2D receptors are inhibited by 35±3% (n=4) and 26±1% (n=9), respectively, in the presence of 100 μM PS.

Figure 1.

Inverse modulation of NMDA receptor subtypes by PS. (a – d), examples of traces obtained from oocytes previously injected with (a) NR1/NR2A, (b) NR1/NR2B, (c) NR1/NR2C, or (d) NR1/NR2D mRNAs. The bar indicates the period of drug application. Interval between consecutive current traces was 45 s. Receptors were activated by co-application of 10 μM glycine plus 80 μM NMDA (NR1/NR2A), 25 μM NMDA (NR1/NR2B and NR1/NR2C), or 10 μM NMDA (NR1/NR2D). Co-application of 100 μM PS to NR1/NR2A or NR1/NR2B receptors resulted in an increase in the agonist response, whereas co-application of 100 μM PS to NR1/NR2C or NR1/NR2D resulted in a decrease in the agonist response. (e) Concentration-response curves for PS effect on NR1/NR2 receptors. Data points are averaged values of normalized peak current responses from oocytes injected with NR1/NR2A (n=8), NR1/NR2B (n=8), NR1/NR2C (n=4) or NR1/NR2D (n=4) RNAs. Responses were normalized to the control response obtained by application of 10 μM glycine plus 80 μM NMDA (NR2A), 25 μM NMDA (NR2B, NR2C) or 10 μM NMDA (NR2D). Error bars indicate s.e.mean. Smooth curves are calculated from the two-state model (equation 1) using the parameters in Table 3. (f) Effect of holding potential on modulation of the NMDA/glycine response by PS. Points are averaged relative currents obtained in the presence of 100 μM PS, standardized relative to the response induced from the same oocyte by 10 μM glycine plus 80 μM (NR1/NR2A, n=4), 25 μM (NR1/NR2B, n=7; NR1/NR2C, n=3), or 10 μM NMDA (NR1/NR2D, n=3). Symbols are defined as in e. Error bars indicate s.e.mean.

As shown in Figure 1e, PS is about equally potent in potentiating NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B receptors, and 3.4 to 5.6 fold less potent as an inhibitor of NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors (Table 1). Enhancement of NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B receptors and inhibition of NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors exhibits little if any voltage dependence (Figure 1f).

Table 1.

Concentration dependence of PS modulation of the NMDA response

To determine how PS enhances or inhibits the response of the NMDA receptor, the glutamate, NMDA, and glycine concentration-response curves were determined in the presence and absence of PS. As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the nature of the modulatory effect of PS depends not only upon subunit composition, but also upon the specific agonist used. With NR1/NR2A receptors, PS enhances the efficacy of NMDA, glutamate (Figure 2a) and glycine (Figure 3a). At NR1/NR2B receptors, however, PS primarily enhances the efficacy of NMDA, but primarily enhances the potency of glutamate (Figure 2b) and glycine (Figure 3b).

Figure 2.

The choice of NR2 subunit determines the direction of PS modulation of the glutamate and NMDA concentration-response curves. Data points are averaged normalized peak NMDA-induced current responses obtained from oocytes injected with (a) NR1/NR2A, (b) NR1/NR2B, (c) NR1/NR2C, or (d) NR1/NR2D mRNAs. Concentration-response data for NMDA and for L-glutamate were obtained in the presence of 10 μM glycine. The data were normalized relative to the current response from the same oocyte induced by co-application of 200 μM NMDA and 10 μM glycine. Error bars represent s.e.mean. Smooth curves are calculated from equation (1) using the parameters in Table 3.

Figure 3.

The choice of NR2 subunit determines the direction of PS modulation of the glycine concentration-response curve. Data points are averaged normalized peak current responses obtained from oocytes injected with (a) NR1/NR2A, (b) NR1/NR2B, (c) NR1/NR2C, or (d) NR1/NR2D mRNAs. Concentration-response data for glycine were obtained in the presence of 10 μM L-glutamate and in the absence and presence of 100 μM PS. The data for each oocyte were normalized relative to the current response induced by co-application of 200 μM NMDA plus 10 μM glycine. Error bars represent s.e.mean. Smooth curves are calculated from equation (1) using the parameters in Table 3.

Negative modulation by PS of NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptor activation is a consequence of a decrease in the efficacies of glutamate, NMDA (Figure 2c,d), and glycine (Figure 3c,d). Agonist potencies are not decreased, indicating that PS does not compete for either the glutamate or glycine recognition sites.

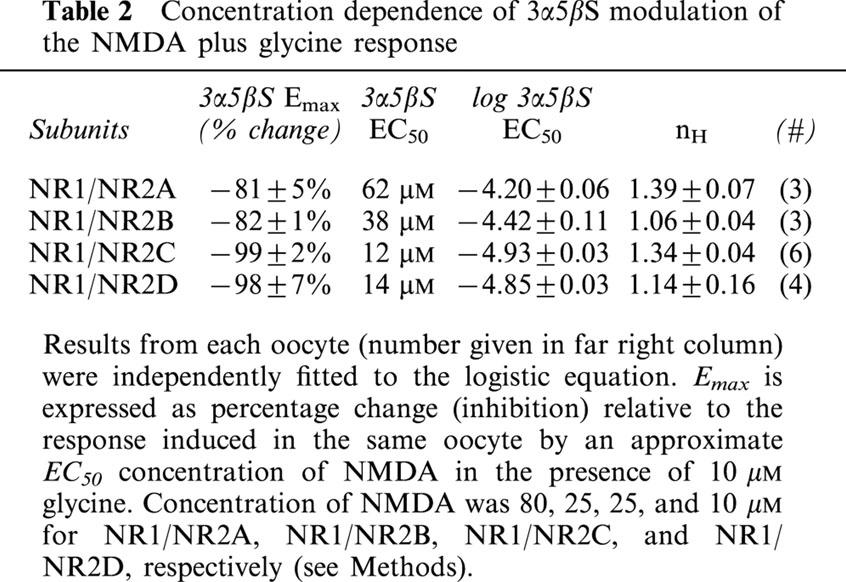

Inhibitory potency of 3α5βS depends upon the NR2 subunit

As shown in Figure 4a – d, 100 μM 3α5βS reversibly inhibits NMDA-induced currents of Xenopus oocytes expressing NR1/NR2A (Figure 4a), NR1/NR2B (Figure 4b), NR1/NR2C (Figure 4c), or NR1/NR2D (Figure 4d) receptors. However, the extent of inhibition is significantly greater with NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors than with NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B receptors (P<0.01, ANOVA with Scheffés post-hoc test). Concentration-response analysis (Figure 4e) indicates that this difference is primarily due to an approximately 4 fold lower potency of 3α5βS at NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B receptors than at NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors (see Table 2 for EC50s). Inhibition of the NMDA induced current by 3α5βS exhibits little if any voltage dependence from −100 to +20 mV (Figure 4f).

Figure 4.

The choice of NR2 subunit influences 3α5βS inhibition of the NMDA response. a – d, examples of traces obtained from oocytes previously injected with NR1/NR2A, NR1/NR2B, NR1/NR2C, or NR1/NR2D mRNAs, respectively. The bar indicates the period of drug application. Interval between consecutive current traces was 45 s. The receptors were activated by co-application of 10 μM glycine plus 80 μM NMDA (NR1/NR2A, a), 25 μM NMDA (NR1/NR2B, b and NR1/NR2C, c), or 10 μM NMDA (NR1/NR2D, d). Typical results are shown; mean inhibition was 53±5% (n=3) for NR1/NR2A, 58±3% (n=3) for NR1/NR2B, 97±2% (n=6) for NR1/NR2C, and 83±3% (n=3) for NR1/NR2D. e, concentration-response curves for 3α5βS effect on NR1/NR2 receptors. Data points are averaged values of normalized steady-state current responses from oocytes injected with NR1/NR2A (n=4), NR1/NR2B (n=3), NR1/NR2C (n=6) or NR1/NR2D (n=4) RNAs. Current responses are expressed relative to the current response in the absence of 3α5βS. Error bars represent s.e.mean. Smooth curves are derived from fits to the logistic equation. f, dependence of 3α5βS effect on membrane potential. Points are averaged relative current obtained in the presence of 100 μM 3α5βS. (NR1/NR2A, n=5; NR1/NR2B, n=10) or 10 μM 3α5βS (NR1/NR2C, n=4; NR1/NR2D, n=10).

Table 2.

Concentration dependence of 3α5βS modulation of the NMDA plus glycine response

To determine how 3α5βS inhibits the glutamate response, concentration-response curves were constructed for glutamate (in the presence of 10 μM glycine) and glycine (in the presence 10 μM glutamate) in the presence and absence of 100 μM 3α5βS. As shown in Figure 5, 3α5βS decreases the efficacy with which glutamate and glycine activate NR1/NR2A (Figure 5a,b), NR1/NR2B (Figure 5c,d), NR1/NR2C (Figure 5e,f), and NR1/NR2D (Figure 5g,h) receptors.

Figure 5.

Effect of 3α5βS on glutamate (a, c, e, g) and glycine (b, d, f, h) concentration-response curve of oocytes expressing NR1/NR2A (a, b), NR1/NR2B (c, d), NR1/NR2C (e, f) or NR1/NR2D (g, h) subunits. Glutamate concentration-response data was obtained in the presence of 10 μM glycine and in the absence or presence of 100 μM 3α5βS. Glycine concentration-response data was obtained in the presence of 10 μM glutamate and in the absence or presence of 100 μM 3α5βS. Data points are averaged normalized peak current responses of three to seven oocytes. Smooth curves are fits to the logistic equation. The data for each oocyte were normalized to standard current responses induced by co-application of 200 μM NMDA and 10 μM glycine. Concentration-response data for glutamate and glycine alone is the same as in Figure 2, and is repeated for comparison.

Modelling the interaction of PS with the NMDA receptor

It seems unlikely that the fundamental mechanism of action of PS would be different for receptors of different subunit composition, or that PS would have different mechanisms of enhancing NMDA and glutamate responses of NR1/NR2B receptors. We therefore considered whether a single allosteric model could accommodate the different effects of PS on agonist concentration-response curves for the four types of NMDA receptors tested. The simplest possible allosteric model is the two-state model, in which a receptor is assumed to exist in either an inactive (closed) or an active (open) conformation, with each conformation having its own characteristic affinity for ligands (Karlin, 1967; Monod et al., 1965). In a two-state model, the efficacy of an agonist is dependent upon the ratio (K′agonist Kagonist−1) of its affinities for the active and inactive states, and upon the gating equilibrium constant, M=[R′] [R]−1, which is the ratio of active to inactive receptors in the absence of agonist (Colquhoun, 1998).

Evidence suggests that the NMDA receptor is tetrameric, with two sites for glutamate/NMDA and two sites for glycine (Clements & Westbrook, 1991). We modelled the receptor on this basis, adding two additional sites for PS (two sites seeming more likely than one on the basis of symmetry) (Figure 6). Activation is treated as concerted, with all subunits activating or deactivating simultaneously. Because little if any desensitization is observed in our experiments (see Figure 1), a desensitized state is not included. This model entails a total of 10 parameters: the dissociation constants for binding of each of the four ligands to the active and inactive states of the receptor, the resting ratio of active to inactive receptors, and a scaling factor related to the number of receptors (the current if all receptors were simultaneously active, expressed relative to the 200 μM NMDA response).

Figure 6.

Allosteric model of NMDA receptor modulation by PS. Activation of the receptor (gating) is assumed to be concerted and described by a two-state model. The model includes six binding sites, two each for glutamate/NMDA, glycine, and PS. High affinity is indicated by a deep ‘slot' for the corresponding ligand, while low affinity is indicated by a shallow slot. Affinity of the active state for PS is greater than that of the resting state for NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B, but less than that of the resting state for NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D.

For each subunit combination, the concentration-response data for all agonists in the presence and absence of PS were simultaneously fitted to the two-state model (equation 1). The two state allosteric model readily accommodates the co-agonist interaction between glutamate/NMDA and glycine, which arises because each of the co-agonists individually has very low efficacy. Simultaneous binding of the co-agonists to the glutamate and glycine sites results in a synergistic interaction, such that their combined efficacy is much greater than the sum of their individual efficacies.

As shown in Figures 1, 2 and 3, in which the smooth curves are calculated from the two-state model using the fitted parameters (Table 3), this model also produced a good fit to the data for the effects of PS on all four subunit combinations. The model provides an explanation for the different effects of PS on the agonist concentration-response curves for NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B receptors. In this type of model, an allosteric modulator is expected to influence both agonist potency and agonist efficacy, but one effect on the other may predominate. If an agonist has high efficacy to begin with, such that it is capable of activating nearly all receptors, then a positive allosteric modulator is predicted to primarily enhance the potency of that agonist, shifting its concentration-response curve to the left. In contrast, a positive allosteric modulator will primarily enhance the efficacy of a partial agonist.

Table 3.

Parameters from fits of the two-state model to concentration response date in the presence and absence of PS

PS increases the efficacy of glutamate and glycine at NR1/NR2A receptors, but primarily increases the potency of glutamate and glycine at NR1/NR2B receptors, suggesting that glutamate and glycine have lower efficacy at NR1/NR2A than at NR1/NR2B receptors. As calculated from the fitted parameters (Table 3), saturating glutamate and glycine activate only 16% of NR1/NR2A receptors, but 88% of NR1/NR2B receptors. In contrast, NMDA has low efficacy at both NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B receptors, producing (at saturating glycine) 13 and 62% maximal activation, respectively, so PS enhances the efficacy of NMDA in both cases.

Conversely, the two-state model predicts that a negative allosteric modulator will primarily decrease the potency of a high-efficacy agonist, while decreasing the efficacy of a partial agonist. In the case of NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors, the major effect of PS is a reduction in the efficacies of glutamate, NMDA, and glycine, suggesting that all of these agonists are relatively inefficient in activating NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors. However, while the model produced a good fit to the data, it was not possible to obtain a unique set of parameter estimates (i.e. more than one set of values produced a good fit) for the NR1/NR2C or NR1/NR2D combinations, indicating that the information in the concentration-response data is not adequate to fully define all 10 parameters for the inhibitory effects of PS on these subunit combinations. Because the fits for NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B both yielded estimates of about 7×10−5 for M (the resting ratio of active to inactive receptors), the concentration response data for NR1/NRC and NR1/NR2D were fit with M fixed to this value, thereby reducing the number of free parameters (Table 3).

In contrast to the results obtained with PS, the two-state model was not able to adequately fit the 3α5βS concentration-response data for any subunit combination, suggesting that the mechanism of action of 3α5βS is different from that of PS.

Discussion

PS modulation is subunit specific

Neuroactive steroids have been postulated to act as neurotransmitters or neuromodulators. PS, a sulphated neurosteroid, is synthesized in brain, and exerts modulatory effects upon NMDA, glycine, and GABAA receptors. Decreased levels of PS in the hippocampus of aged rats are correlated with cognitive impairment, which can be transiently reversed by intraperitoneal or intrahippocampal injection of PS (Vallee et al., 1997), suggesting that PS plays a role in cognition.

PS has been shown to act as a positive modulator of NMDA induced currents of chick spinal cord and rat hippocampal neurons in culture (Bowlby, 1993; Wong & Moss, 1994; Wu et al., 1991), to increase NMDA mediated Ca2+ accumulation (Irwin et al., 1992) and excitotoxic cell death (Weaver, 1998), and to enhance glutamate mediated synaptic currents of hippocampal neurons in culture (Park-Chung et al., 1997). In addition, PS potentiates the NMDA induced current of Xenopus oocytes expressing recombinant NR1100/NR2A receptors (Park-Chung et al., 1997; Yaghoubi et al., 1998). The present study is the first to report that the modulatory effect of PS is contingent upon the NR2 subunit composition of the NMDA receptor, and that PS inhibits, rather than enhances, the function of NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors.

As previously reported (Yaghoubi et al., 1998), PS enhances the NMDA-induced current of oocytes expressing NR1/NR2A receptors primarily by increasing the efficacy of NMDA. Similarly, we find that PS enhances the efficacy of glutamate and glycine as NR1/NR2A receptor agonists. However, whereas PS increases the efficacy of NMDA at NR1/NR2B receptors, it enhances only the potency of glutamate, with no effect on the maximum glutamate response, in much the same way as benzodiazepines enhance the potency of GABA at the GABAA receptor without affecting the maximum GABA response (Choi et al., 1981). Thus, the effect of PS on the agonist concentration response curve depends upon both the subunit combination and the particular agonist used.

A number of antagonists have been identified that exhibit selective affinity depending upon the NR2 subunit. For example, felbamate (Kleckner et al., 1999), ifenprodil (Williams, 1993), haloperidol (Ilyin et al., 1996), and various structurally related compounds (Guzikowski et al., 2000) selectively inhibit NMDA receptors containing the NR2B subunit, whereas the snail toxin conantokin-R selectively inhibits receptors containing either the NR2A or NR2B subunit (White et al., 2000). The degree of potentiation of the NMDA induced current by spermine has been reported to be dependent upon both the NR1 splice variant and the NR2 subunit present (Zhang et al., 1994). PS appears to be unique, however, in its ability to selectively enhance or inhibit, depending upon the type of NR2 subunit that is present.

The observation that potentiation of the NMDA receptor by PS is dependent upon the presence of the NR2A or NR2B subunit suggests that the PS binding site responsible for potentiation may be partially or entirely located on the NR2 subunit. One difficulty with this hypothesis is that Xenopus oocytes injected only with NR1 subunit mRNA exhibit weak NMDA responses that are potentiated by PS (Yaghoubi et al., 1998). However, mutagenesis studies suggest that the glutamate/NMDA binding site resides on the NR2 subunit (Anson et al., 1998), while the glycine site resides on NR1 (Wafford et al., 1995), so the NMDA responses observed in oocytes injected only with NR1 subunits likely reflect coassembly of NR1 with an endogenous NR2A or NR2B-like subunit (Soloviev & Barnard, 1997).

The inhibitory effect of PS on NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors is primarily due to a decrease in the efficacies of glutamate, NMDA, and glycine, suggesting a noncompetitive or uncompetitive mechanism of action. The simplest way in which this kind of inhibition can arise is by occlusion of the channel pore by drug. However, there is no evident voltage-dependence of inhibition, such as would be expected if the charged PS molecule needed to penetrate significantly into the channel's electrical field, so it is likely that the inhibitory effect of PS is mediated by a separate allosteric site.

Physiological implications of subunit selective modulation

Our working hypothesis is that PS functions as an endogenous neuromodulator to regulate the activity of ligand gated ion channels. A neuromodulatory role for PS is consistent with its presence and synthesis in the CNS and its ability to modulate hippocampal synaptic transmission in cell culture (Park-Chung et al., 1997). It has yet to be demonstrated, however, that synaptic concentrations of endogenous PS are high enough for modulation of synaptic transmission to occur under normal physiological conditions. The present results have important implications for the postulated role of PS as a neuromodulator. In particular, the results predict that PS will enhance NMDA receptor activation at synapses containing predominantly NR2A or NR2B subunits, but to decrease NMDA receptor activation at synapses containing predominantly NR2C or NR2D subunits.

The NR2A subunit appears after birth and becomes highly expressed in hippocampus and cortex, with moderate expression in other fore-, mid-, and hindbrain regions. The NR2B subunit appears during embryonic development, and is expressed at high levels in the cortex, hippocampus, striatum, thalamus, and olfactory bulb, and to a lesser extent in midbrain regions (Laurie et al., 1997; Monyer et al., 1994; Wenzel et al., 1997a). Over-expression of the NR2B subunit in forebrains of transgenic mice results in enhanced learning and memory, suggesting that this subunit plays an important role in cognition (Tang et al., 1999). The NR2C subunit appears after birth, and is expressed primarily in the cerebellum (Laurie et al., 1997; Monyer et al., 1994; Wenzel et al., 1997a). The NR2D subunit is strongly expressed in embryonic and neonatal thalamus, hypothalamus, and brain stem, and to a lesser extent in cortex, hippocampus, and septum, but declines after birth and is present at lower levels in the adult (Dunah et al., 1996; Laurie et al., 1997; Wenzel et al., 1997b). Thus, our findings suggest that the inhibitory effects of PS are likely to be particularly prominent in cerebellum and in the developing nervous system.

Potency of 3α5βS depends upon subunit composition

In contrast to PS, 3α5βS inhibits all four subunit combinations, although it is more potent at receptors containing the NR2C or NR2D subunits than at those containing NR2A or NR2B. Also, whereas PS produces only partial inhibition of NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors even at high concentrations, 3α5βS is able to produce nearly complete inhibition of all four subunit combinations. Inhibition of glutamate and glycine induced currents by 3α5βS is insurmountable and voltage independent, arguing that 3α5βS does not compete for the glutamate or glycine binding sites, and that its site of action is not within the electrical field of the channel.

Potentiation of NR1/NR2A receptors by PS has been shown to be mediated by a separate site from that responsible for inhibition by 3α5βS (Park-Chung et al., 1997). However, PS and 3α5βS both have inhibitory effects on NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors, raising the question of whether the site responsible for the potentiating effect of PS on NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B receptors is simply absent from NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors, unmasking an inhibitory effect of PS mediated through the 3α5βS site. The present results do not provide a direct answer to this question, but we were able to fit both the potentiating and inhibitory effects of PS with a two-state allosteric model, whereas this model could not account for the inhibitory effects of 3α5βS on any subunit combination. It therefore seems likely that the inhibitory effects of 3α5βS and PS on NR1/NR2C and NR1/NR2D receptors are mediated by different sites and mechanisms.

The discovery that steroid modulators of the NMDA receptor can exhibit strong selectivity for receptors of specific subunit composition also has significant implications for drug design, indicating that it will likely be possible to develop therapeutic agents that target the steroid modulatory sites of particular NMDA receptor subtypes.

Acknowledgments

Research support was provided by NIMH MH-49469.

Abbreviations

- 3α5βS

3α-hydroxy-5β-pregnan-20-one sulphate, pregnanolone sulphate

- PS

pregnenolone sulphate

References

- AKAZAWA C., SHIGEMOTO R., BESSHO Y., NAKANISHI S., MIZUNO N. Differential expression of five N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit mRNAs in the cerebellum of developing and adult rats. J. Comp. Neur. 1994;347:150–160. doi: 10.1002/cne.903470112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANSON L.C., CHEN P.E., WYLLIE D.J.A., COLQUHOUN D., SCHOEPFER R. Identification of amino acid residues of the NR2A subunit that control glutamate potency in recombinant NR1/NR2A NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:581–589. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00581.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOWLBY M. Pregnenolone sulfate potentiation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channels in hippocampal neurons. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;43:813–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOI D.W., FARB D.H., FISCHBACH G.D. Chlordiazepoxide selectively potentiates GABA conductance of spinal cord and sensory neurons in cell culture. J. Neurophysiol. 1981;45:621–631. doi: 10.1152/jn.1981.45.4.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLEMENTS J.D., WESTBROOK G.L. Activation kinetics reveal the number of glutamate and glycine binding sites on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Neuron. 1991;7:605–613. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLQUHOUN D. Binding, gating, affinity and efficacy: the interpretation of structure- activity relationships for agonists and of the effects of mutating receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:924–947. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORPÉCHOT C., SYNGUELAKIS M., TALHA S., AXELSON M., SJÖVALL J., VIHKO R., BAULIEU E.-E., ROBEL P. Pregnenolone and its sulfate ester in the rat brain. Brain Res. 1983;270:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90797-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE LEAN A.P., MUNSON P.J., RODBARD D. Simultaneous analysis of families of sigmoidal curves: application to bioassay, radioligand assay, and physiological dose-response curves. Am. J. Physiol. 1978;235:E97–E102. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.2.E97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUNAH A.W., YASUDA R.P., WANG Y.H., LUO J., DAVILA-GARCIA M., GBADEGESIN M., VICINI S., WOLFE B.B. Regional and ontogenic expression of the NMDA receptor subunit NR2D protein in rat brain using a subunit-specific antibody. J. Neurochem. 1996;67:2335–2345. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67062335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLOOD J.F., GARLAND J.S., MORLEY J.E. Evidence that cholecystokinin-enhanced retention is mediated by changes in opioid activity in the amygdala. Brain Res. 1992;585:94–104. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91194-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUZIKOWSKI A.P., TAMIZ A.P., ACOSTA-BURRUEL M., HONG-BAE S., CAI S.X., HAWKINSON J.E., KEANA J.F., KESTEN S.R., SHIPP C.T., TRAN M., WHITTEMORE E.R., WOODWARD R.M., WRIGHT J.L., ZHOU Z.L. Synthesis of N-substituted 4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)piperidines, 4-(4- hydroxybenzyl)piperidines, and (+/−)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)pyrrolidines: selective antagonists at the 1A/2B NMDA receptor subtype. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:984–994. doi: 10.1021/jm990428c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ILYIN V.I., WHITTEMORE E.R., GUASTELLA J., WEBER E., WOODWARD R.M. Subtype-selective inhibition of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors by haloperidol. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:1541–1550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IRWIN R.P., LIN S.-Z., ROGAWSKI M.A., PURDY R.H., PAUL S.M. Steroid potentiation and inhibition of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated intracellular Ca++ responses: structure activity studies. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;271:677–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IRWIN R.P., MARAGAKIS N.J., ROGAWSKI M.A., PURDY R.H., FARB D.H., PAUL S.M. Pregnenolone sulfate augments NMDA receptor mediated increases in intracellular Ca2+ in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 1992;141:30–34. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARLIN A. On the application of ‘a plausible model' of allosteric proteins to the receptor for acetylcholine. J. Theoret. Biol. 1967;16:306–320. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(67)90011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLECKNER N.W., GLAZEWSKI J.C., CHEN C.C., MOSCRIP T.D. Subtype-selective antagonism of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors by felbamate: insights into the mechanism of action. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;289:886–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LADURELLE N., EYCHENNE B., DENTON D., BLAIR-WEST J., SCHUMACHER M., ROBEL P., BAULIEU E. Prolonged intracerebroventricular infusion of neurosteroids affects cognitive performances in the mouse. Brain Res. 2000;858:371–379. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)01953-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAURIE D.J., BARTKE I., SCHOEPFER R., NAUJOKS K., SEEBURG P.H. Regional, developmental, and interspecies expression of the four NMDAR2 subunits, examined using monoclonal antibodies. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1997;51:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEONARD J.P., KELSO S.R. Apparent desensitization of NMDA responses in Xenopus oocytes involves calcium-dependent chloride current. Neuron. 1990;4:53–60. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90443-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAIONE S., BERRINO L., VITAGLIANO S., LEYVA J., ROSSI F. Pregnenolone sulfate increases the convulsant potency of N-methyl-D-aspartate in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;219:477–479. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90493-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATHIS C., PAUL S.M., CRAWLEY J.N. The neurosteroid pregnenolone sulphate blocks NMDA antagonist-induced deficits in a passive avoidance memory task. Psychopharmacol. 1994;116:201–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02245063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATHIS C., VOGEL E., CAGNIARD B., CRISCUOLO F., UNGERER A. The neurosteroid pregnenolone sulfate blocks deficits induced by a competitive NMDA antagonist in active avoidance and lever-press learning tasks in mice. Neuropharmacol. 1996;35:1057–1064. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCILHINNEY R.A., MOLNAR E., ATACK J.R., WHITING P.J. Cell surface expression of the human N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit 1a requires the co-expression of the NR2A subunit in transfected cells. Neurosci. 1996;70:989–997. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEZIANE H., MATHIS C., PAUL S.M., UNGERER A. The neurosteroid pregnenolone sulfate reduces learning deficits induced by scopolamine and has promnestic effects in mice performing an appetitive learning task. Psychopharmacol. 1996;126:323–330. doi: 10.1007/BF02247383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONOD J., WYMAN J., CHANGEUX J.-P. On the nature of allosteric transitions: A plausible model. J. Mol. Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONYER H., BURNASHEV N., LAURIE D.J., SAKMANN B., SEEBURG P.H. Developmental and regional expression in the rat brain and functional properties of four NMDA receptor subtypes. Neuron. 1994;12:529–540. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORI H., MISHINA M. Structure and function of the NMDA receptor channel. Neuropharmacol. 1995;34:1219–1237. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00109-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PALLARES M., DARNAUDERY M., DAY J., LE MOAL M., MAYO W. The neurosteroid pregnenolone sulfate infused into the nucleus basalis increases both acetylcholine release in the frontal cortex or amygdala and spatial memory. Neurosci. 1998;87:551–558. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARK-CHUNG M., WU F.-S., FARB D.H. 3α-Hydroxy-5β-pregnan-20-one sulfate: a negative modulator of the NMDA-induced current in cultured neurons. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;46:146–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARK-CHUNG M., WU F.-S., PURDY R.H., MALAYEV A.A., GIBBS T.T., FARB D.H. Distinct sites for inverse modulation of NMDA receptors by sulfated steroids. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:1113–1123. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.6.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETRALIA R.S., WANG Y.X., WENTHOLD R.J. The NMDA receptor subunits NR2A and NR2B show histological and ultrastructural localization patterns similar to those of NR1. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:6102–6120. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-10-06102.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOLOVIEV M.M., BARNARD E.A. Xenopus oocytes express a unitary glutamate receptor endogenously. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;273:14–18. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANG Y.P., SHIMIZU E., DUBE G.R., RAMPON C., KERCHNER G.A., ZHUO M., LIU G., TSIEN J.Z. Genetic enhancement of learning and memory in mice. Nature. 1999;401:63–69. doi: 10.1038/43432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALLEE M., MAYO W., DARNAUDERY M., CORPECHOT C., YOUNG J., KOEHL M., LE MOAL M., BAULIEU E.E., ROBEL P., SIMON H. Neurosteroids: deficient cognitive performance in aged rats depends on low pregnenolone sulfate levels in the hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:14865–14870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAFFORD K.A., KATHORIA M., BAIN C.J., MARSHALL G., LE BOURDELLES B., KEMP J.A., WHITING P.J. Identification of amino acids in the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor NR1 subunit that contribute to the glycine binding site. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;47:374–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEAVER C.E., JRSteroid Modulation of NMDA-induced Death of Rat Hippocampal Neurons in Primary Cell Culture 1998. Ph.D. Thesis. Boston: Boston University School of Medicine

- WEAVER C.E., JR, LAND M.B., PURDY R.H., RICHARDS K.G., GIBBS T.T., FARB D.H. Geometry and charge determine pharmacological effects of steroids on N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor induced Ca2+ accumulation and cell death. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 2000;293:747–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEAVER C.E., JR, MAREK P., PARK-CHUNG M., TAM S.W., FARB D.H. Neuroprotective activity of a new class of steroidal inhibitors of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:10450–10454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WENZEL A., BENKE D., MOHLER H., FRITSCHY J.M. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors containing the NR2D subunit in the retina are selectively expressed in rod bipolar cells. Neuroscience. 1997a;78:1105–1112. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00663-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WENZEL A., FRITSCHY J.M., MOHLER H., BENKE D. NMDA receptor heterogeneity during postnatal development of the rat brain: differential expression of the NR2A, NR2B, and NR2C subunit proteins. J. Neurochem. 1997b;68:469–478. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68020469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITE H.S., MCCABE R.T., ARMSTRONG H., DONEVAN S.D., CRUZ L.J., ABOGADIE F.C., TORRES J., RIVIER J.E., PAARMANN I., HOLLMANN M., OLIVERA B.M. In vitro and in vivo characterization of conantokin-R, a selective NMDA receptor antagonist isolated from the venom of the fish-hunting snail Conus radiatus. J. Pharm. Exper. Ther. 2000;292:425–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS K. Ifenprodil discriminates subtypes of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor: selectivity and mechanisms at recombinant heteromeric receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;44:851–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WONG M., MOSS R.L. Patch-clamp analysis of direct steroidal modulation of glutamate receptor-channels. J. Neuroendocrinol. 1994;6:347–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1994.tb00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU F.-S., GIBBS T.T., FARB D.H. Pregnenolone sulfate: a positive allosteric modulator at the NMDA receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1991;40:333–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAGHOUBI N., MALAYEV A., RUSSEK S.J., GIBBS T.T., FARB D.H. Neurosteroid modulation of recombinant ionotropic glutamate receptors. Brain Res. 1998;803:153–160. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00644-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG L., ZHENG X., PAUPARD M.C., WANG A.P., SANTCHI L., FRIEDMAN L.K., ZUKIN R.S., BENNETT M.V. Spermine potentiation of recombinant NMDA receptors is affected by subunit composition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:10883–10887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]