Abstract

Transport of a fluorescent somatostatin analogue (NBD-octreotide) across freshly isolated functionally intact capillaries from porcine brain was visualized by confocal microscopy and quantitated by image analysis.

Luminal accumulation of NBD-octreotide showed all characteristics of specific and energy-dependent transport. Steady-state luminal fluorescence averaged 2 – 3 times cellular fluorescence and was reduced to cellular levels when metabolism was inhibited by NaCN.

The accumulation of NBD-octreotide in capillary lumens was inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by unlabelled octreotide, by verapamil, PSC-833 and cyclosporin A, potent inhibitors of p-glycoprotein, and by leucotriene C4, a strong modulator of Mrp2. Conversely, unlabelled octreotide reduced luminal accumulation of fluorescent BODIPY-verapamil on p-glycoprotein and of fluorescein-methotrexate, on Mrp2. None of the inhibitors used significantly reduced cellular accumulation of the fluorescent substrates.

Together, the data are consistent with octreotide being transported across the luminal membrane of porcine brain capillaries by both P-gp and Mrp2, providing further evidence that both transporters contribute substantially to the active barrier function of this endothelium.

Keywords: Blood brain barrier, cancer, central nervous system, confocal microscopy, Mrp2, octreotide, p-glycoprotein, somatostatin

Introduction

The long-acting somatostatin analogue octreotide, a cyclic octapeptide, has a broad spectrum of clinical applications. Its pharmacological actions are similar to the natural hormone, somatostatin, and octreotide is an even more potent antagonist of growth hormone, glucagon, and insulin action. Octreotide also decreases splanchnic blood flow and inhibits secretion of gastrointestinal hormones like gastrin, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), secretin or pancreatic polypeptide. Due to this pharmacological profile octreotide is used for treatment of some symptoms of metastatic carcinoid tumours (flushing and diarrhea), and vasoactive intestinal peptide secreting adenomas (diarrhoea). In AIDS-patients with diarrhoea, it can be used to stabilize patients with severe malnutrition and dehydration. In addition, octreotide reduces growth hormone and/or IGF-I (somatomedin C) levels in acromegalic patients. Since a high density of somatostatin receptors has been reported in several tumours (Reubi et al., 1987; Dutour et al., 1998) of the central nervous system, octreotide or other somatostatin analogues could also be of value in treating or localizing such tumours.

One important limitation on the use of somatostatin analogues in diagnosing and treating brain tumours is restricted penetration into the brain. A previous report showed that in meningeomas located outside the blood brain barrier, somatostatin receptor scans of 111In-DTPA-D-Phe1-octreotide localization detected all tumours. Inside the brain, however, only tumours with a disrupted blood brain barrier could be detected (Haldemann et al., 1995). In vitro studies using bovine brain capillary endothelial cell monolayers and fluorescent labelled derivatives of octreotide (fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and 4-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazol (NBD)-octreotide, respectively), suggested that transcellular permeation is very limited and that passage occurs along a paracellular pathway (Jaehde et al., 1994). One reason for the low transcellular permeability of the somatostatin analogues may be a potential interaction with drug export proteins located at the blood brain barrier, such as multidrug resistance protein (mdr or p-glycoprotein) or multidrug resistance associated proteins (Mrps) (Miller et al., 2000). Here we used freshly isolated, morphologically and functionally intact porcine brain capillaries along with confocal laser scanning microscopy to investigate whether specific transport contributes to the poor ability of octreotide and its analogues to enter the brain.

Methods

Chemicals

NBD-Octreotide was synthesized by coupling the fluorescent residue 7-bromo-4-nitrobenzofurazan to octreotide. Octreotide and PSC-833 were from Novartis (Basle, Switzerland). Fluorescein-methotrexate and BODIPY-verapamil were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, U.S.A.). All other chemicals were purchased from commercial sources at the highest purity available.

Capillary isolation

Capillaries of porcine brain were isolated by mechanical treatment of cortical grey matter. For that purpose, 1 – 2 mm cubes of brain tissue were transferred into teflon chambers containing 1.5 ml of ice-cold buffer, consisting of (mM) NaCl 103, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 2.5, KH2PO4 1.2, MgSO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25, glucose 5 and sodium-pyruvate 1 (pH 7.4 adjusted by gassing with 95% O2/5% CO2). Under a dissecting microscope, the tissue cubes were teased with fine forceps to release capillaries. The capillaries rapidly adhered to the chamber floor, a 4×4 mm glass cover slip. After dissection, the chambers containing buffer and capillaries were gassed and covered with 60 mm culture dishes. All experiments with capillaries were performed in the closed and gassed chambers at room temperature. The experiments were carried out immediately after capillary isolation, although it was possible to store the capillaries in buffer for 2 – 3 h at 4°C without significant functional changes.

Protein determination and analyses of enzymatic activities

Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method (Biorad, Munich, Germany). The activity of the capillary marker enzymes alkaline phosphates (E.C.3.1.3.1) and γ-glutamyltranspeptidase (E.C.2.3.2.1) were determined as described before (Nobmann et al., 2001).

Peptide stability

Isolated capillaries were incubated with 0.5 μM NBD-octreotide for 60 min in a 0.5 ml incubation tube. The suspension was homogenized in a small glass homogenizer with tight fitting pestle. After centrifugation at 10,000×g for 5 min, the supernatants were analysed for proteolytic degradation of the peptide by high performance thin layer chromatography on silica 60 plates using CHCl3/methanol/50% aqueous solution of acetic acid (7 : 3 : 1) as solvent. Fluorescence was identified by UV-detection.

Immunohistochemistry

Isolated capillaries were fixed on slides for 20 min with 3% paraformaldehyde, 0.1% glutaradaldehyde and 3.4% sucrose in PBS, washed, permeabilized for 15 min with 1% (v v−1) Triton X-100 in PBS and washed again. Then, the capillaries were incubated for 1 h with the primary antibodies C219 for detection of P-gp and M2III-6 for detection of MRP2 (Alexis Biochemicals, Grünberg, Germany). After washing, the capillaries were incubated for 40 min with the corresponding fluorochrome conjugated secondary antibody, FITC-conjugated rabbit anti mouse IgG, at a 1 : 20 dilution (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) for 1 h in a humid chamber in the dark. Stained capillaries were viewed using confocal microscopy.

Western blot experiments

For the detection of P-gp, Mab C219 (Alexis, Grünberg, Germany) was used. For the detection of multidrug resistance related protein 2 (Mrp2) the rabbit polyclonal antibodies k78Mrp2 (van Aubel et al., 1998) and M2III-6 (Alexis) were used. Brush border membranes isolated from rat duodenum (Schmitz et al., 1973) served as positive control for P-gp and Mrp2. Electrophoresis and protein transfer were performed with a Mini protean II apparatus and a Mini Trans-Blot cell (Biorad, Munich, Germany). Nitrocellulose membranes were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with the antibodies C219 for detection of P-gp (1 : 20 diluted) and M2III-6 (1 : 50 diluted) or k78Mrp2 (1 : 200 diluted) for detection of MRP2. After washing, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (rabbit anti mouse IgG and goat anti rabbit IgG respectively, both 1 : 1000 diluted (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). After washing P-gp and Mrp2 were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, U.K.).

Fluorescence microscopy

Confocal microscopy was carried out as recently described (Miller et al., 2000). Briefly, capillaries were isolated rapidly as described above in a teflon chamber containing 1.5 ml of Krebs-Henseleit-medium, pH 7.4, with fluorescent compounds (1 μM) and added transport effectors. Capillaries were preincubated with effectors for 30 min before addition of the fluorescent compound. Previous kinetic studies indicated that BODIPY-verapamil can be used as a marker substrate for p-glycoprotein (Lelong et al., 1991; Simmons et al., 1995). In addition, based on substrate and inhibitor specificity studies in isolated renal proximal tubules and brain capillaries we have found that transport mediated by Mrp2 can be monitored using a fluorescent methotrexate derivative, FL-MTX (Masereeuw et al., 1996; 2000; Miller et al., 1997; 2000). Both fluorescent compounds were used as marker substrates for P-gp and Mrp2, respectively, in the present study.

The chamber floor was a 4×4 cm glass cover slip through which the tissue could be viewed by means of an inverted confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica, Bensheim, Germany). The capillaries in the chamber were viewed through a 63× water immersion objective (NA 1.2), using the 488-nm laser line of an Argon/Krypton laser. Photobleaching of the fluorescent compounds was avoided by using a low laser intensity (<20% of maximum intensity). Under the conditions used tissue autofluorescence was not detectable. Fluorescent compounds were dissolved in DMSO and added to the incubation medium. Earlier experiments had demonstrated that the concentrations of DMSO used (<1%) had no significant effect on transport of the fluorescent labelled compounds (Miller et al., 2000). To make a measurement, a field with several capillaries was selected and an epi-fluorescence image was acquired by averaging 4 frames. Mean cellular and luminal fluorescence intensities were measured from stored images using the Scion Image software (Beta 3b, Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.) as described (Miller et al., 2000).

Statistics

Data are given as means±s.e. Means were considered to be statistically different, when the probability value (P) was less than 0.05 by use of Student's t-test.

Results

Capillary isolation and immunostaining

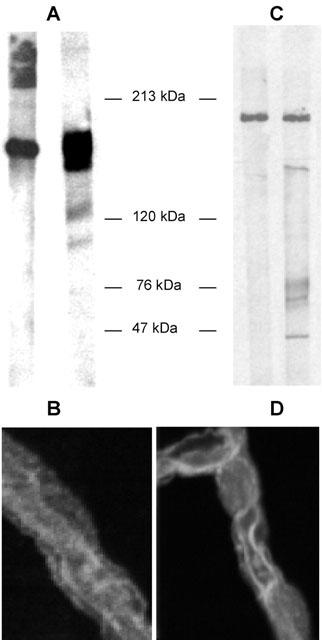

Mechanical treatment of cortical gray matter from pig brain yielded capillary fragments of 0.15 – 0.5 mm length. These fragments were morphologically and enzymatically characterized. The endothelial marker enzymes alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyltranspeptidase showed an enrichment of activity compared to that of the brain homogenates of 32±1 fold and 19±4 fold, respectively. Incubation of the capillaries with FITC-Dextran 4000, a marker for paracellular permeability, showed that no fluorescent compound permeated into the capillary lumen within 60 – 90 min of incubation, suggesting that the integrity of the tight junctions had been maintained during that time period. Western blots confirmed the presence of P-gp and Mrp2 (Figure 1). Immunostaining localized both transporters to the luminal membrane of capillary endothelial cells (Figure 1), confirming our recent observations for rat capillaries (Miller et al., 2000).

Figure 1.

Western blot detection of p-glycoprotein (A) and Mrp2 (C) in homogenates from freshly isolated porcine brain capillaries (right lanes: brain capillaries; left lanes: detection in brush border membranes from rat jejunum serving as positive controls). Immunostaining of isolated capillaries shows localization of p-glycoprotein (B) and Mrp2 (D) at the luminal membrane of the endothelial cells. Representative figures from three separate isolations.

Transport experiments

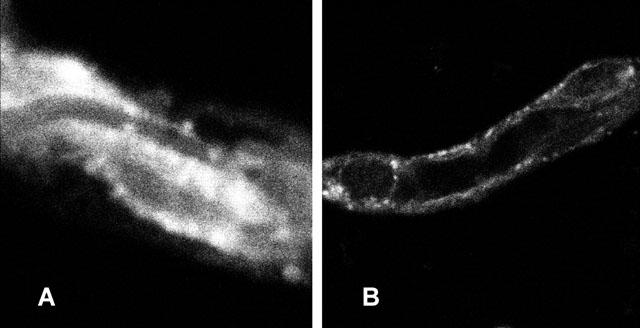

In initial experiments, we confirmed by high performance thin layer chromatography that degradation of NBD-octreotide was neglegible during the time of incubation. Less than 2% of detectable fluorescence in supernatants from capillary homogenates was different from the control before incubation. Incubating porcine brain capillaries in medium containing 1 μM NBD-octreotide led to a striking accumulation of fluorescence in the aqueous capillary lumen. The time course of accumulation was rapid. After 5 – 10 min, a bright fluorescence appeared within the capillary lumens, rose rapidly and reached steady-state after approximately 30 min. At that time, cellular fluorescence exceeded fluorescence in the medium 5 – 6 times and luminal fluorescence was 2 – 4 times higher than the cellular fluorescence. Fluorescence within the luminal plasma membrane, which may be caused by nonspecific binding of NBD-octreotide to membrane lipids, was clearly lower than the fluorescence within the luminal space. Figure 2 shows a representative confocal micrograph of an NBD-octreotide-exposed capillary. Figure 2 also shows that steady-state luminal accumulation of NBD-octreotide was reduced 70 – 75% by the metabolic inhibitor NaCN (1 mM), which had only a small effect on cellular fluorescence.

Figure 2.

(A) Accumulation of NBD-octreotide in the lumen of a freshly isolated porcine brain capillary at steady-state (30 min). (B) Luminal accumulation of fluorescent peptide is significantly reduced by 1 mM NaCN; representative for 24 measurements from three different capillary isolations.

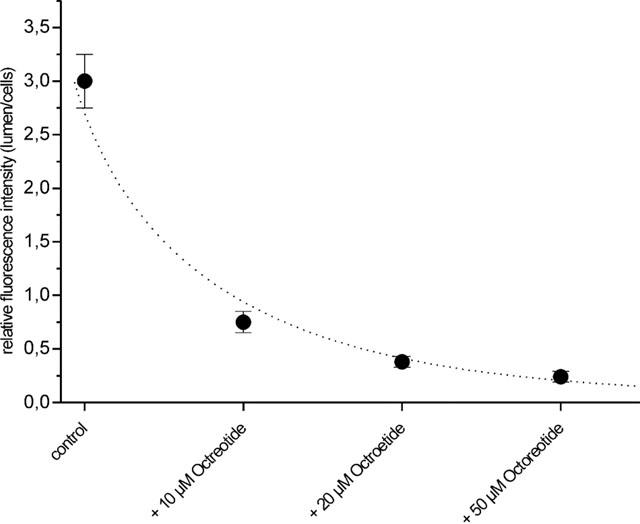

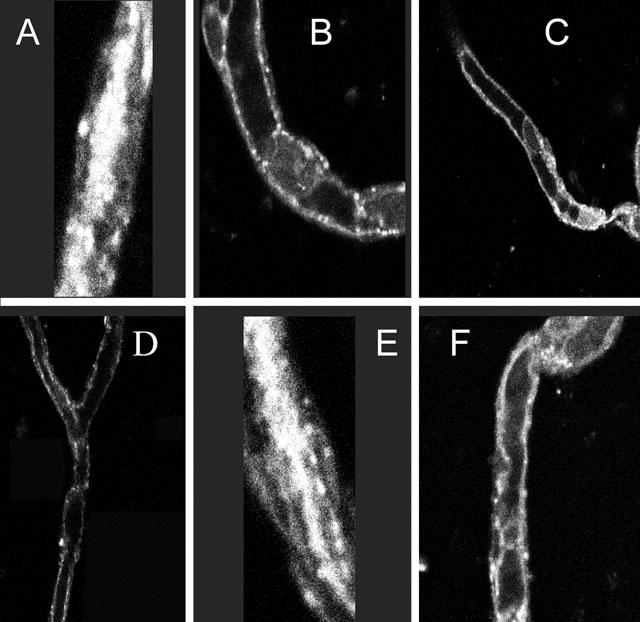

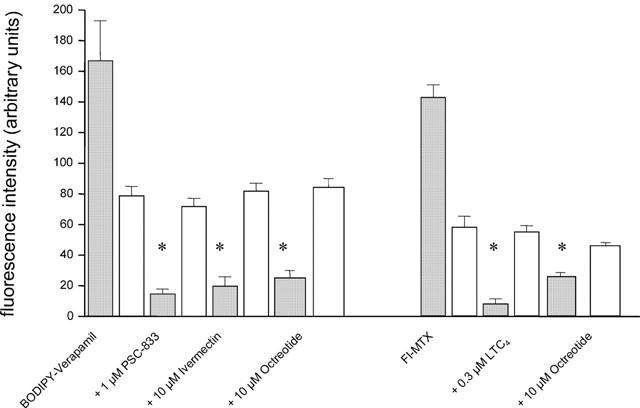

When unlabelled octreotide was added to the incubation medium at increasing concentrations (10 – 50 μM), a slight increase in cellular fluorescence could be observed. However, in parallel a significant decrease of luminal fluorescence was seen, indicating that labelled and unlabelled octreotide used the same excretory pathway (Figure 3). Furthermore, PSC-833, Cyclosporin A and verapamil, all substrates of p-glycoprotein, substantially reduced the luminal accumulation of NBD-octreotide (Figure 4). Transport was also substantially diminished, when the capillaries were pre-incubated with 0.3 μM of the Mrp2-substrate LTC4 (Figure 4). Thus, accumulation of NBD-octreotide in capillary lumens was concentrative, energy-dependent and specific. Based on the inhibition pattern and immunostaining, p-glycoprotein and Mrp2 appear to be involved. Therefore, interactions of octreotide with transport of BODIPY-verapamil and fluorescent methotrexate, both being marker substrates for p-glycoprotein (Lelong et al., 1991; Simmons et al., 1995) and Mrp2, respectively (Masereeuw et al., 1996; 2000; Miller et al., 1997; 2000) were studied. Figure 5 shows that luminal accumulation of BODIPY-verapamil was reduced by PSC-833 and ivermectin and that luminal accumulation of FL-MTX was reduced by LTC4. For both substrates, unlabelled octreotide reduced luminal accumulation, consistent with this somatostatin analogue interacting with both transporters (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of luminal accumulation of NBD-octreotide by increasing concentrations of unlabelled octreotide. Data given as means±s.e. for 12 capillaries.

Figure 4.

Excretion of NBD-octreotide into porcine brain capillary lumens in the absence (A,E) and presence of p-glycoprotein substrates/inhibitors:10 μM cyclosporin A (B), 5 μM PSC 833 (C), 50 μM verapamil (D). The Mrp2 substrate LTC4 (0.3 μM) also reduces NBD-octreotide excretion (F). Images are representative for images from capillaries from five separate isolations.

Figure 5.

Transport of the p-glycoprotein-substrate BODIPY-Verapamil (medium concentration 1 μM) and the Mrp2-substrate Fl-methotrexate (medium concentration 1 μM) into porcine brain capillary lumens in absence (control) and presence of inhibitors of p-glycoprotein and Mrp2, respectively and in presence of octreotide. Grey bars indicate luminal fluorescence intensity, white bars cellular fluorescence intensity. Data given as mean±s.e. for 10 capillaries. *Significantly different from control (P< 0.05).

Discussion

Little is known about the cellular mechanisms responsible for the poor permeation of somatostatin analogues into the brain. For example, only small amounts of radioactively iodinated Tyr-somatostatin-(1-14)pentadecapeptide cross the blood brain barrier in vivo (Banks & Kastin, 1985), and a negligible amount of octreotide passes the barrier in vitro, presumably through a paracellular pathway (Jaehde et al., 1994). Previous studies (Abbruscato et al., 1997) using CTAP, a cyclic, penicillamin-containing octapeptide, that is structurally related to somatostatin, also indicated that entry into the brain was by passive diffusion rather than by saturable transport. Similar observations were made with a series of somatostatin analogue octapeptides (Banks et al., 1990). In contrast, transport of peptide from CNS to blood was found to be saturable (Banks et al., 1990; 1994; Kitazawa et al., 1998), although the mechanism responsible remains to be identified. These previous results indicate that two elements appear to limit entry of somatostatin and its analogues to the brain: low passive permeability and mediated efflux.

We recently described a confocal microscopy-based experimental system that provides information about cellular mechanisms of excretory transport (brain to blood) in intact, isolated brain capillaries (Miller et al., 2000). With this experimental technique, active transport of compounds into the small luminal space of the capillaries can be visualized and measured. To the extent that it occurs, specific transport from cells to medium is more difficult to assess. Using this system, we demonstrated the ATP-driven drug efflux pumps, p-glycoprotein and Mrp2, were important components of the blood brain barrier, functioning at the level of the luminal membrane of brain capillary endothelial cells. This put the transporters in the correct location to both drive xenobiotics out of the CNS and to limit xenobiotic entry. These observations added to the growing body of evidence indicating that the barrier has both passive and active components and that ABC transporters contribute to the latter. In the present study, we used this experimental system to examine mechanisms that could be responsible for the brain to blood transport of a fluorescent octreotide derivative, NBD-octreotide. This octreotide derivative exhibits a pharmacokinetic behaviour very similar to that of the parent peptide (Fricker et al., 1991; Drewe et al., 1993; Gutmann et al., 2000).

Our confocal images show that NBD-octreotide accumulation in the lumens of porcine brain capillaries was reduced to cellular levels or below by metabolic inhibition (NaCN), unlabelled octreotide and by both p-glycoprotein and Mrp2 substrates, respectively. In contrast, neither octreotide nor the p-glycoprotein and Mrp2 substrates had any effect on cellular accumulation of NBD-octreotide. This suggests, that cellular accumulation of the fluorescent octreotide derivative is not carrier mediated, an observation that agrees with previous studies on other somatostatin analogues (Banks et al., 1990; Abbruscato et al., 1997). Consistent with the inhibition pattern for NBD-octreotide transport, we found that unlabelled octreotide was a potent inhibitor of luminal accumulation of a p-glycoprotein substrate and an Mrp2 substrate. All of these findings point to p-glycoprotein and Mrp2 as the active components of the blood brain barrier contributing to the low penetration of the somatostatin derivative, octreotide, into the CNS. In this regard, in liver and kidney, ABC-transporters also are responsible for the active excretion of somatostatin analogues across the bile canalicular membrane and proximal tubular brush border membrane, respectively (Yamada et al., 1998; Gutmann et al., 2000).

ABC transporters also carry other peptides out of the brain, such as Met-enkephalin analogue derivatives of δ-opioid receptor selective peptide D penicillamine (DPDPE) (Witt et al., 2000), cyclosporin A (Begley, 1992; Tsuji et al., 1993) or some small model peptides between 2 and 3 amino acids length (Chikhale et al., 1995). In addition, efflux transporters seem to be involved in brain to blood transport of several peptides of neurologic relevance, like oxytocin (Durham et al., 1991) or corticotropin releasing hormone (Martins & Banks, 1996), although the molecular nature of these transporters has not yet been clarified.

Taken together, all data suggest that ABC transporters may have a more general function in clearing the CNS from peptides. Our experiments together with the previous findings (Banks et al., 1990; 1994; Kitazawa et al., 1998) as well as preliminary inhibition experiments with octreotide derivatives (data not shown) argue that ABC transporters play a major role in preventing somatostatin analogue peptides from entry into the central nervous system. This may be of special importance for the treatment of somatostatin sensitive brain tumours and the interpretation of diagnostic somatostatin receptor scans, when tumours are shielded by an intact blood brain barrier.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the German Research Foundation DFG-Grant FR1211/6-2, and a Grant of Baden-Württemberg's Research Center Program: ABC-Proteins and Drug Transport.

Abbreviations

- BBB

blood brain barrier

- CNS

central nervous system

- DMSO

dimethylsulphoxide

- Mrp2

multidrug resistance associated protein 2

- NBD

4-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazol

- P-gp

p-glycoprotein=mdr1 gene product

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal peptide

References

- ABBRUSCATO T.J., THOMAS S.A., HRUBY V.J., DAVIS T.P. Blood-brain barrier permeability and bioavailability of a highly potent and μ-selective opioid receptor antagonist, CTAP: comparison with morphine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;250:402–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANKS W.A., KASTIN A.J. Peptides and the blood-brain barrier: lipophilicity as a predictor of permeability. Brain Res. Bull. 1985;15:287–292. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(85)90153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANKS W.A., KASTINA A.J., SAM H.M., CAO V.T., KING B., MANESS L.M., SCHALLY A.V. Saturable efflux of the peptides RC-160 and Tyr-MIF-1 by different parts of the blood brain barrier. Brain Res. Bull. 1994;35:179–182. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANKS W.A., SCHALLY A.V., BARRERA C.M., FASOLD M.B., DURHAM D.A., CSERNUS V.J., GROOT K., KASTIN A.J. Permeability of the murine blood-brain barrier to some octapeptide analogs of somatostatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1990;87:6762–6766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEGLEY D.J. The interaction of some centrally active drugs with the blood-brain barrier and circumventricular organs. Prog. Brain Res. 1992;91:163–169. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62331-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIKHALE E.G., BURTON P.S., BORCHARDT R.T. The effect of verapamil on the transport of peptides across the blood brain barrier in rats: kinetic evidence for an apically polarized efflux mechanism. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;273:298–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUTOUR A., KUMAR U., PANETTA R., OUAFIK L., FINA F., SASI R., PATEL Y.C. Expression of somatostatin receptor subtypes in human brain tumors. Int. J. Cancer. 1998;76:620–627. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980529)76:5<620::aid-ijc2>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DREWE J., FRICKER G., VONDERSCHER J., BEGLINGER C. Enteral absorption of octreotide: absorption enhancement by polyoxyethylene-24-cholesterol ether. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1993;108:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12799.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DURHAM D.A., BANKS W.A., KASTIN A.J. Carrier-mediated transport of labelled oxytocin from brain to blood. Neuroendocrinol. 1991;53:447–452. doi: 10.1159/000125756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRICKER G., BRUNS C., MUNZER J., ALBERT R., KISSEL K., BRINER U., VONDERSCHER J. Intestinal absorption of SMS 201-995 visualized by fluorescence derivatization. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1544–1552. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90651-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUTMANN H., MILLER D.S., DROULLE A., DREWE J., FRICKER G. P-glycoprotein and Mrp2-mediated octreotide transport in renal proximal tubule. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:251–256. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALDEMANN A.R., ROSLER H., BARTH A., WASER B., GEIGER L., GODOY N., MARKWALDER R.V., SEILER R.W., SULZER M., REUBI J.C. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy in central nervous system tumors: role of blood-brain barrier permeability. J. Nuclear Med. 1995;36:403–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAEHDE U., MASEREEUW R., DE BOER A.G., FRICKER G., NAGELKERKE J.F., VONDERSCHER J., BREIMER D.D. Quantification and visualization of the transport of octreotide, a somatostatin analogue, across monolayers of cerebrovascular endothelial cells. Pharm. Res. 1994;11:442–448. doi: 10.1023/a:1018929508018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAZAWA T., TERASAKIT T., SUZUKIH H., KAKEE A., SUGIYAMA Y. Efflux of taurocholic acid across the blood brain barrier: interaction with cyclic peptides. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;286:890–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LELONG I.H., GUZIKOWSKI A.P., HAUGLAND R.P., PASTAN I., GOTTESMAN M.M., WILLINGHAM M.C. Fluorescent verapamil derivative for monitoring activity of the multidrug transporter. Mol. Pharmacol. 1991;40:490–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTINS J.M., KASTIN A.J., BANKS W.A. Unidirectional specific and modulated brain to blood transport of corticotropin-releasing hormone. Neuroendocrinol. 1996;63:338–348. doi: 10.1159/000126974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASEREEUW R., RUSSEL F.G., MILLER D.S. Multiple pathways of organic anion secretion in renal proximal tubule revealed by confocal microscopy. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:F1173–F1182. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.6.F1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASEREEUW R., TERLOUW S.A., VAN AUBEL R.A., RUSSEL F.G., MILLER D.S. Endothelin B receptor-mediated regulation of ATP-driven drug secretion in renal proximal tubule. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;57:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER D.S., FRICKER G., DREWE J. p-Glycoprotein-mediated transport of a fluorescent rapamycin derivative in renal proximal tubule. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;82:440–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER D.S., NOBMANN S., GUTMANN H., DREWE J., FRICKER G. Xenobiotic transport across isolated brain microvessels studied by confocal microscopy. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;58:1357–1367. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOBMANN S., BAUER B., FRICKER G. Ivermectin excretion by isolated functionally intact brain endothelial capillaries. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 2001;132:722–728. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REUBI J.C., LANG W., MAURER R., KOPER J.W., LAMBERTS S.W.J. Distribution and biochemical characterization of somatostatin receptors in tumors of the human central nervous system. Cancer Res. 1987;47:5758–5764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMITZ J., PREISER H., MAESTRACCI D., GHOSH B.K., CERDA J.J., CRANE R.K. Purification of the human intestinal brush border membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1973;323:98–112. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMMONS N.L., HUNTER J., JEPSON M.A. Targeted delivery of a substrate for P-glycoprotein to renal cysts in vitro. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1237:31–36. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00077-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUJI A., TAMAI I., SAKATA A., TENDA Y., TERASAKI T. Restricted transport of cyclosporin A across the blood-brain barrier by a multidrug transporter, P-glycoprotein. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1993;46:1096–1099. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90677-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRAMM U., FRICKER G., WENGER R., MILLER D.S. P-glycoprotein-mediated secretion of a fluorescent cyclosporin analogue by teleost renal proximal tubules. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:F46–F52. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.268.1.F46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN AUBEL R.A., VAN KUIJOK M.A., KOENDERINK J.B., DEEN P.M., VAN OS C.H., RUSSEL F.G. Adenonine triphosphate-dependent transport of organic anionic conjugates by the rabbit multidrug resistance-associated protein Mrp2 expressed in insect cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:1062–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMADA T., KATO Y., KUSUHARA H., LEMAIRE M., SUGIYAMA Y. Characterization of the transport of a cationic octapeptide, octreotide, in rat bile canalicular membrane: possible involvement of p-glycoprotein. Biol. Pharmaceut. Bull. 1998;21:874–878. doi: 10.1248/bpb.21.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]