Abstract

Agonists of protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2) trigger neurally mediated mucus secretion accompanied by mucosal cytoprotection in the stomach. The present study immunolocalized PAR-2 in the rat gastric mucosa and examined if PAR-2 could modulate pepsin/pepsinogen secretion in rats.

PAR-2-like immunoreactivity was abundant in the deep regions of gastric mucosa, especially in chief cells.

The PAR-2 agonist SLIGRL-NH2, but not the control peptide LSIGRL-NH2, administered i.v. repeatedly at 0.3 – 1 μmol kg−1, four times in total, significantly facilitated gastric pepsin secretion, although a single dose produced no significant effect.

The PAR-2-mediated gastric pepsin secretion was resistant to omeprazole, NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) or atropine, and also to ablation of sensory neurons by capsaicin.

Our study thus provides novel evidence that PAR-2 is localized in mucosal chief cells and facilitates gastric pepsin secretion in the rats, most probably by a direct mechanism.

Keywords: Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2), pepsin, chief cell, gastric secretion

Introduction

Protease-activated receptors (PARs) are a family of G protein-coupled seven trans-membrane domain receptors, the activation of which occurs by proteolytic unmasking of the cryptic receptor-activating sequence that binds to the body of the receptor itself (Kawabata & Kuroda, 2000). Among four members of this family (PARs 1 – 4) that have been cloned, PAR-2 is activated by trypsin, mast cell tryptase and coagulation factors VIIa and Xa (Camerer et al., 2000; Kawabata et al., 2001c; Molino et al., 1997; Nystedt et al., 1994). PAR-2 can also be nonenzymatically activated by synthetic peptides (i.e. SLIGRL – NH2) based on the N-terminal sequence of the tethered ligand (Nystedt et al., 1994). PAR-2 is unevenly distributed throughout the mammalian body, especially in the alimentary tract (Kawabata & Kuroda, 2000). PAR-2 modulates gastrointestinal motility in vitro as well as in vivo (Cocks et al., 1999; Corvera et al., 1997; Kawabata et al., 1999; 2001b). PAR-2 also participates in regulation of alimentary exocrine secretion such as salivary and pancreatic secretion (Kawabata et al., 2000; Nguyen et al., 1999). Recently, we provided evidence that a PAR-2 agonist, SLIGRL – NH2, given in vivo, induces gastric mucus secretion accompanied by mucosal cytoprotection, via release of calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) and tachykinins from sensory neurons (Kawabata et al., 2001a). Thus, PAR-2 that is activated possibly during tissue injury or inflammation (Kawabata & Kuroda, 2000), could play a protective role in gastric mucosa under pathological conditions. To clarify further the roles that PAR-2 plays in gastric mucosa, we sought to immunolocalize PAR-2 in rat gastric mucosa. The histochemical analysis showed abundant expression of PAR-2 by mucosal chief cells, known to secret pepsin/pepsinogen. We therefore turned our attention to the role of PAR-2 in chief cells. Here, for the first time, we show that PAR-2 present in mucosal chief cells acts to facilitate pepsin secretion in the rat stomach.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (7 weeks old, Japan SLC. Inc., Japan) were used with approval the Kinki University School of Pharmaceutical Sciences' Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Immunostaining of PAR-2 in the rat gastric mucosa

Rats were anaesthetized with urethane (1.35 g kg−1, i.p.) and perfused transcardially with 150 ml of physiological saline and subsequently with 500 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in a phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The stomach was removed, postfixed and serially sectioned (at 10-μM thickness) on a freezing microtome. Immunostaining of PAR-2 was performed using a rabbit polyclonal antibody (B5) that specifically recognizes PAR-2, targeted to a peptide corresponding to the cleavage/activation site of rat PAR-2 (30GPNSKGR↓SLIGRLDT46P-YGGC) (Kong et al., 1997). Sections were first incubated in 1% normal goat serum for 30 min, and then in the B5 antibody at a dilution of 1 : 1000 for 16 h at 4°C. Sections were then incubated with biotinylated goat antiserum against rabbit IgG for 1 h and subsequently treated with a peroxidase-conjugated avidin – biotin complex (Vectastain ABC kit, Vector Laboratories Inc., U.S.A.) for 30 min at 4°C. The labelled cells were visualized by 0.05% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine-tetra HCl solution including 0.4% nickel ammonium sulphate and 0.035% hydrogen peroxide.

In vivo assay of pepsin secretion

Under urethane anaesthesia, secretagogues, the specific PAR-2-activating peptide SLIGRL – NH2 and the inactive control peptide LSIGRL – NH2, were administered i.v. from one to four times at 1-h intervals to the rat with a pylorus ligation. Amastatin, an inhibitor of aminopeptidase, at 2.5 μmol kg−1 was given i.v. once 1 min before the first dose of secretagogues, in order to reduce degradation of peptides. After 0, 30, 120 or 240 min, the rat was sacrificed by decapitation and the luminal liquid in the stomach was collected. If the time points of administration and collection coincided (at time 0 and 120 min), the final dose was not given. The assay of pepsin/pepsinogen in the samples was performed according to the previously described method (Anson & Mirsky, 1933) with modifications. Briefly, the gastric content was incubated with 2.5% haemoglobin, for 10 min at 37°C, and the reaction was then stopped by adding 5% trichloroacetic acid. After centrifugation (4°C, 2190 g, 10 min), the soluble hydrolysis products in the supernatant were collected and the optical density was measured at 280 nM. The amount of pepsin/pepsinogen secreted was calculated from a standard curve of authentic pepsin, and is expressed as mg of pepsin.

Inhibition experiments

Omeprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, at 60 mg kg−1 (Tashima et al., 1998) was administered s.c. 30 min before the first dose of four repeated administrations of SLIGRL – NH2. NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), an NO synthase inhibitor, at 20 mg kg−1 (Handy & Moore, 1998; Kawabata et al., 2001a) and atropine at 3 mg kg−1 (Bentley et al., 1999) were given s.c., 5 min before each of four doses of SLIGRL – NH2, four times in total. For ablation of sensory neurons, rats received three doses of capsaicin (25, 50 and 50 mg kg−1, s.c.) over 32 h (at 0, 6, 32 h, respectively) under pentobarbital (40 mg kg−1, i.p.) anaesthesia (Kawabata et al., 2001a), 10 days before experiments. The efficacy of the capsaicin treatment was verified by the eye-wiping test, as described elsewhere (Steinhoff et al., 2000). All control animals received administration of vehicle.

Drugs

PAR-2-related peptides were prepared by a standard solid phase synthesis procedures. The concentration, purity and composition of the peptides were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry and quantitative amino acid analysis. L-NAME hydrochloride and capsaicin were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.); atropine and omeprazole were from Wako Pure Chemicals (Osaka, Japan). Amastatin was from the Peptide Institute, Inc. (Minoh, Japan). Omeprazole was suspended in 0.5% sodium carboxymethylcellulose, and capsaicin was in a saline solution containing 10% ethanol and Tween 80.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean±s.e.mean. Statistical analysis was performed using the Tukey's multiple comparison test or Student's t-test, and set at a P<0.05 level.

Results

Immunolocalization of PAR-2 in rat gastric mucosa

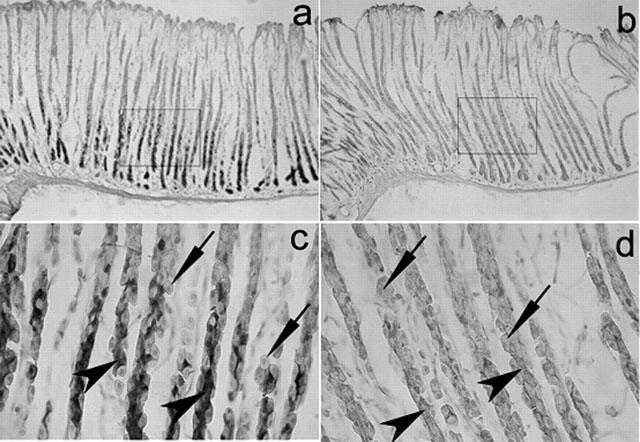

PAR-2-like immunoreactive cells were found mainly in the deep regions of gastric mucosa (Figure 1a). Observation with greater magnification showed strong staining in chief cells, but not clear staining in parietal cells (Figure 1c). The PAR-2-immunostaining was abolished by preabsorption of antibody with 20 μg ml−1 of the antigen peptide (Figure 1b,d). Histochemical analysis using the serum from a non-immunized rabbit also provided no positive immunostaining in the mucosa (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Immunolocalization of PAR-2 in rat gastric mucosa. (a) and (b) Microphotographs of immunostaining of PAR-2 in rat gastric mucosa (original magnification: ×100). (c) and (d) Microphotographs of areas corresponding to the square in (a) and (b), respectively (original magnification: ×400). (a) and (c) were stained with the anti-PAR-2 antibody; (b) and (d) were treated with the antibody pre-absorbed with a peptide (20 g ml−1) used for immunization. Arrow heads show chief cells, and allows indicate parietal cells.

PAR-2-triggered secretion of gastric pepsin in rats

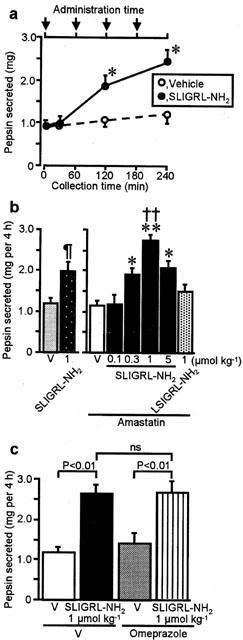

Given the abundant expression of PAR-2 in the chief cells, known to secrete pepsin, we next examined if PAR-2 could modulate gastric pepsin secretion in the anaesthetized rat with a pylorus ligation in vivo. No secretion of pepsin was detected 30 min after a single dose of SLIGRL – NH2, a specific PAR-2-activating peptide, at 1 μmol kg−1, in combination with amastatin. However, significant increase in the amount of luminal pepsin was detected for 2 and 4 h in the rats that had received two and four doses of the peptide at 1 μmol kg−1, respectively, compared with the administrating vehicle after amastatin (Figure 2a). The amount of luminal pepsin at 4 h in the rats that had received only first two doses at 0 and 1 h (data not shown) was equivalent to the data at 2 h in the rats that had received two doses (Figure 2a). The dose-response study was performed for four repeat doses of SLIGRL – NH2, in order to obtain steady effects at distinct doses. The effect of SLIGRL – NH2 in combination with amastatin 2.5 μmol kg−1 on the accumulation of luminal pepsin over 4 h was dose-dependent in a range of 0.1 – 1 μmol kg−1 (×4), although the largest dose, 5 μmol kg−1 (×4), produced decreased effect, resulting in a bell-shaped dose-response curve (Figure 2b, right), as seen in our previous study concerning the PAR-2-mediated salivation (Kawabata et al., 2000). In contrast, LSIGRL – NH2, a PAR-2-inactive peptide, administered at 1 μmol kg−1 (×4) following amastatin, had no such effect (Figure 2b, right). Amastatin itself, at the dose employed, did not affect the pepsin secretion; the amount of luminal pepsin (mg per 4 h) was 1.156±0.146 (n=5) and 1.120±0.131 (n=8) in the rats treated with vehicle and amastatin, respectively. SLIGRL – NH2 at 1 μmol kg−1 (×4), when administered without pre-administration of amastatin, produced a significant but smaller effect than that of the same dose of SLIGRL – NH2 in combination with amastatin (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Secretion of gastric pepsin produced by repeated administration of the PAR-2 agonist in rats. (a) The PAR-2 agonist SLIGRL – NH2 at 1 mol kg−1 or vehicle (V) was administered i.v., repeatedly at 1-h intervals, to the rat pretreated with amastatin at 2.5 mol kg−1, and gastric luminal content was collected 0, 30, 120 or 240 min after the first dose. Arrows show the time point at which SLIGRL – NH2 was administered. (b) Dose-related effects of four repeated doses of SLIGRL – NH2 and the inactive control LSIGRL – NH2 for 4 h in the rat without (left panel) or with (right panel) pre-administration of amastatin. (c) Effect of SLIGRL – NH2 at 1 mol kg−1 (×4) following amastatin in the rat pretreated with s.c. omeprazole at 60 mg kg−1 or vehicle. Data show means with s.e.mean from 5 – 8 rats. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ¶P<0.05 vs each vehicle; ††P<0.01 vs LSIGRL – NH2. ns, not significant.

Characterization of PAR-2-mediated gastric pepsin secretion

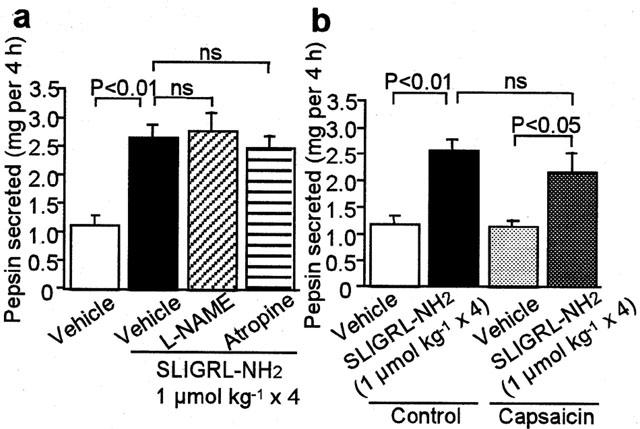

The pepsin secretion by the PAR-2 agonist over 4 h remained unaffected, even when acid output was blocked by omeprazole (Figure 2c). The PAR-2-mediated pepsin secretion was resistant to L-NAME or atropine (Figure 3a), each of which, by itself, did not affect the pepsin secretion (the value (mg per 4 h) was 1.11±0.18, 1.36±0.16 and 1.12±0.01 in the rat treated with vehicle, L-NAME and atropine alone, respectively (n=4)). Moreover, ablation of sensory neurons by pretreatment with capsaicin did not alter the secretory effect of the PAR-2 agonist (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Lack of effects of L-NAME, atropine and capsaicin of the PAR-2-mediated pepsin secretion in the rat. (a) L-NAME at 20 mg kg−1 or atropine at 3 mg kg−1 was repeatedly administered s.c. 5 min before each of four doses of i.v. SLIGRL – NH2 at 1 mol kg−1. Data show the mean with s.e.mean from six – seven (vehicle) and four (treated) rats. (b) SLIGRL – NH2 at 1 mol kg−1 was administered i.v. four times to the rats pretreated with vehicle or capsaicin for ablation of sensory neurons. Data show the mean with s.e.mean from seven rats. ns, not significant.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that PAR-2 is expressed abundantly in the chief cells in rat gastric mucosa, and further indicates that activation of PAR-2 induces secretion of pepsin. This secretion most likely occurs via a direct action on the chief cells, although a humoral mechanism cannot be entirely ruled out. It is clear that the PAR-2-mediated pepsin secretion is not secondary to acid output, because omeprazole did not modify the pepsin secretion following repeated administration of the PAR-2 agonist. Our data also show that the effect of the PAR-2 agonist is independent of sensory neurons, NO formation and muscarinic receptors. Taken together, PAR-2 expressed in chief cells is considered to mediate pepsin secretion, while PAR-2 present in sensory neurons, upon stimulation, triggers release of neuropeptides, leading to mucus secretion (Kawabata et al., 2001a). PAR-2 would thus appear to function as a double-edged sword in the stomach, since luminal pepsin and mucus could have opposing effect on the gastric mucosa.

It was of our surprise that the PAR-2 agonist triggered delayed pepsin secretion only after 2 – 4 repeated administrations. This unusual characteristic of the effect might imply the existence of multiple steps in the mechanisms underlying the PAR-2-mediated pepsin secretion, although the detailed analysis is now in progress in our laboratory. It is also noteworthy that the dose-response curve for the pepsin secretion due to the PAR-2 agonist was bell-shaped, as seen previously for the salivation by the PAR-2 agonist (Kawabata et al., 2000), which might predict the feedback mechanism for PAR-2-mediated exocrine secretion.

The histochemical detection of strong PAR-2-immunoreactivity on the mucosal chief cells led us originally to hypothesize that PAR-2 might function to suppress pepsin secretion in chief cells, based on our recent evidence that PAR-2 agonists exhibited strong mucosal cytoprotection in rat gastric injury models (Kawabata et al., 2001a). In contrast, we found that the PAR-2 agonist unexpectedly facilitated pepsin secretion. Therefore, it is likely that PAR-2 may play a pro-inflammatory/pro-ulcerative role, in addition to a neurally mediated cytoprotective role, in the gastric mucosa. This dual role might rationalize our previous findings that the PAR-2 agonist produced dose-dependent cytoprotection at low doses, but showed relatively inflammatory/aggravating effects at high doses, in two distinct gastric injury models (Kawabata et al., 2001a). The physiological meaning of the dual role that PAR-2 plays in the gastric mucosa is still open to question. PAR-2 can be activated by multiple proteases such as trypsin, mast cell tryptase and coagulation factors VIIa and Xa that might be activated and/or accessible to mucosal tissues including chief cells and sensory neurons during inflammation or tissue injury (Camerer et al., 2000; Kawabata & Kuroda, 2000; Kawabata et al., 2001c). In the future, other proteases in the stomach may also be discovered as novel endogenous agonists for PAR-2. PAR-2 is primarily protective in the gastric mucosa and considered a novel target for development of therapeutic drugs for gastric injury (Kawabata et al., 2001a), whereas the PAR-2-mediated pepsin secretion by chief cells found in the present study may counteract the cytoprotective effect.

Substance P and neurokinin A that can be released from the sensory neurons following PAR-2 activation (Kawabata et al., 2001a; Steinhoff et al., 2000) are capable of stimulating secretion of pepsin in the stomach (Schmidt et al., 1999). However, our experiments using capsaicin indicate that the PAR-2-triggered secretion of pepsin is independent of sensory neuronal activation. Neither muscarinic receptors nor NO, known to mediate pepsin secretion (Blandizzi et al., 1999), were found to contribute to the PAR-2-mediated pepsin secretion. The signal transduction mechanisms in chief cells for the PAR-2-mediated secretory response remains to be investigated. In summary, the present study would add the PAR-2-mediated pepsin secretion in gastric mucosal chief cells to the list of the roles that PAR-2 may play in the alimentary tract.

Abbreviations

- L-NAME

NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester

- PAR-2

protease-activated receptor-2

References

- ANSON M.L., MIRSKY A.E. The estimation of pepsin with hemoglobin. J. Gen. Physiol. 1933;16:59–63. doi: 10.1085/jgp.16.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENTLEY J.C., BOURSON A., BOESS F.G., FONE K.C., MARSDEN C.A., PETIT N., SLEIGHT A.J. Investigation of stretching behavior induced by the selective 5-HT6 receptor antagonist, Ro 04-6790, in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:1537–1542. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLANDIZZI C., LAZZERI G., COLUCCI R., CARIGNANI D., TOGNETTI M., BASCHIERA F., TACCA M.D. CCK1 and CCK2 receptors regulate gastric pepsinogen secretion. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;373:74–84. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMERER E., HUANG W., COUGHLIN S.R. Tissue factor- and factor X-dependent activation of protease-activated receptor 2 by factor VIIa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:5255–5260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COCKS T.M., SOZZI V., MOFFATT J.D., SELEMIDIS S. Protease-activated receptors mediate apamin-sensitive relaxation of mouse and guinea pig gastrointestinal smooth muscle. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:586–592. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORVERA C.U., DERY O., MCCONALOGUE K., BOHM S.K., KHITIN L.M., CAUGHEY G.H., PAYAN D.G., BUNNETT N.W. Mast cell tryptase regulates rat colonic myocytes through proteinase-activated receptor 2. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:1383–1393. doi: 10.1172/JCI119658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANDY R.L.C., MOORE P.K. Effects of selective inhibitors of neuronal nitric oxide synthase on carrageenan-induced mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., KINOSHITA M., NISHIKAWA H., KURODA R., NISHIDA M., ARAKI H., ARIZONO N., ODA Y., KAKEHI K. The protease-activated receptor-2 agonist induces gastric mucus secretion and mucosal cytoprotection. J. Clin. Invest. 2001a;107:1443–1450. doi: 10.1172/JCI10806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., KURODA R. Protease-activated receptor (PAR), a novel family of G protein-coupled seven trans-membrane domain receptors: activation mechanisms and physiological roles. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 2000;82:171–174. doi: 10.1254/jjp.82.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., KURODA R., NAGATA N., KAWAO N., MASUKO T., NISHIKAWA H., KAWAI K. In vivo evidence that protease-activated receptors 1 and 2 modulate gastrointestinal transit in the mouse. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001b;133:1213–1218. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., KURODA R., NAKAYA Y., KAWAI K, NISHIKAWA H., KAWAO N. Factor Xa-evoked relaxation in rat aorta: involvement of PAR-2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001c;282:432–435. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., KURODA R., NISHIKAWA H., KAWAI K. Modulation by protease-activated receptors of the rat duodenal motility in vitro: possible mechanisms underlying the evoked contraction and relaxation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:865–872. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., NISHIKAWA H., KURODA R., KAWAI K., HOLLENBERG M.D. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2): regulation of salivary and pancreatic exocrine secretion in vivo in rats and mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:1808–1814. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONG W., MCCONALOGUE K., KHITIN L.M., HOLLENBERG M.D., PAYAN D.G., BOHM S.K., BUNNETT N.W. Luminal trypsin may regulate enterocytes through proteinase-activated receptor 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:8884–8889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOLINO M., BARNATHAN E.S., NUMEROF R., CLARK J., DREYER M., CUMASHI A., HOXIE J.A., SCHECHTER N., WOOLKALIS M., BRASS L.F. Interactions of mast cell tryptase with thrombin receptors and PAR-2. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:4043–4049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NGUYEN T.D., MOODY M.W., STEINHOFF M., OKOLO C., KOH D.S., BUNNETT N.W. Trypsin activates pancreatic duct epithelial cell ion channels through proteinase-activated receptor-2. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:261–269. doi: 10.1172/JCI2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NYSTEDT S., EMILSSON K., WAHLESTEDT C., SUNDELIN J. Molecular cloning of a potential proteinase activated receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:9208–9212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMIDT P.T., RASMUSSEN T.N., HOLST J.J. Tachykinins stimulate acid and pepsinogen secretion in the isolated porcine stomach. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1999;166:335–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINHOFF M., VERGNOLLE N., YOUNG S.H., TOGNETTO M., AMADESI S., ENNES H.S., TREVISANI M., HOLLENBERG M.D., WALLACE J.L., CAUGHEY G.H., MITCHELL S.E., WILLIAMS L.M., GEPPETTI P., MAYER E.A., BUNNETT N.W. Agonists of proteinase-activated receptor 2 induce inflammation by a neurogenic mechanism. Nat. Med. 2000;6:151–158. doi: 10.1038/72247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TASHIMA K., KOROLKIEWICZ R., KUBOMI M., TAKEUCHI K. Increased susceptibility of gastric mucosa to ulcerogenic stimulation in diabetic rats – role of capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:1395–1402. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]