Abstract

Neuronal cholinergic input is an important regulator of epithelial electrolyte transport and hence water movement in the gut.

In this study, colitis was induced by treating mice with 4% (w v−1) dextran sodium-sulphate (DSS)-water for 5 days followed by 3 days of normal water. Mid-colonic segments were mounted in Ussing chambers and short-circuit current (Isc, indicates net ion movement) responses to the cholinergic agonist, carbachol (CCh; 10−4 M)±tetrodotoxin, atropine (ATR), hexamethonium (HEX), naloxone or phenoxybenzamine were assessed.

Tissues from mice with DSS-induced colitis displayed a drop in Isc in response to CCh (−11.3±3.3 μA/cm2), while those from control mice showed a transient increase in Isc (76.3±13.0 μA/cm2). The ΔIsc in colon from DSS-treated mice was tetrodotoxin-sensitive, atropine-insensitive and was reversed by hexamethonium (HEX+CCh=16.7±7.8 μA/cm2), indicating involvement of a nicotinic receptor.

CCh induced a drop in Isc in tissues from controls only when they were pretreated with the cholinergic muscarinic receptor blocker, atropine: ATR+CCh=−21.3±7.0 μA/cm2. Nicotine elicited a drop in Isc in Ussing-chambered colon from both control and DSS-treated mice that was TTX-sensitive.

The drop in Isc evoked by CCh challenge of colonic tissue from DSS-treated mice or ATR+CCh challenge of control tissue was not significantly affected by blockade of opiate or α-adrenergic receptors by naloxone or phenoxybenzamine, respectively.

The data indicate that DSS-colitis reveals a nicotinic receptor that becomes important in cholinergic regulation of ion transport.

Keywords: Mouse, colon, nervous system, short-circuit current, muscarinic, nicotinic, inflammation

Introduction

The vectorial transport of ions across the epithelial lining of the gastrointestinal tract creates the driving force for water movement between the gut lumen and the mucosa. At the level of the enterocyte, net electrolyte (Na+, H+, Cl−, HCO3−) exchange between the lumen and the interstitial space is regulated by the coordinated activity of the Na+/K+/ATPase pump, ion exchangers and co-transporters, and ion-specific channels (Barrett & Keely, 2000; Seidler et al., 2000). Thus, water movement in the gut is controlled by epithelial electrolyte transport, which in turn, is regulated by intrinsic factors, such as the enteric nervous system, and extrinsic factors such as bacterial toxins (Cooke, 1994; Perdue & McKay, 1994).

A variety of enteropathies are characterized by increased water secretion that can result in diarrhoea: a primary host defence response that can become life-threatening if the diarrhoeal response is exaggerated or chronic. Conversely if water flux into the gut is reduced constipation can result. Analysis of tissues from rodent models of gut inflammation or resected from individuals suffering from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD: Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis), mounted in Ussing-type chambers, consistently reveal that evoked changes in short-circuit current (Isc, indicates net ion transport across the preparation) by electrical nerve stimulation or exogenous secretatagogues (e.g. cholinomimetics and anti-IgE) are diminished compared to control tissues (Asfaha et al., 1999; Crowe & Perdue, 1993; Kachur et al., 1995). The mechanism(s) underlining the reduced ion transport responsiveness to a range of secretogogues has yet to be fully elucidated. Recently, we examined epithelial ion transport in colonic tissues from mice in which colitis had been induced by a 5 day treatment of 4% dextran sodium-sulphate (DSS) in drinking water (Diaz-Granados et al., 2000). In accordance with other models of colitis, we showed that the ΔIsc-evoked by electrical field stimulation and the adenylate cylclase-activator, forskolin, were reduced. Moreover, the ΔIsc evoked in response to the cholinergic agonist, carbachol (CCh), was not only reduced in magnitude, the current deflection was opposite to that observed in CCh-stimulated murine control colon – rather than a transient increase Isc in response to CCh, tissue from mice with DSS colitis had a transient decrease in Isc. The present study was undertaken to assess this dysregulated cholinergic control of ion transport in the colon of mice treated with DSS. Using a pharmacological approach, our findings indicate that the abnormal CCh response in colon of DSS-treated mice is via a cholinergic nicotinic receptor and is an α-adrenergic, opiate-independent event.

Methods

Animals and induction of colitis

Male Balb/c mice (6 – 8 wk old; Harlan Animal Suppliers, Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.) were housed in standard micro-isolater cages with ad libitum access to standard laboratory chow pellets and tap water. For the induction of acute colitis, mice received 4% (w v−1) DSS (40 kDa, ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, OH U.S.A.) in drinking water for 5 days followed by a 3 day period during which the mice received normal tap water (Diaz-Granados et al., 2000; Reardon et al., 2001). Time-matched control mice received normal tap water only. Additional experiments were performed with male C57/B16 mice (Harlan Animal Suppliers). All experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee at McMaster University and were in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council of Animal Care.

Assessment of colitis

Mice were weighed daily for the duration of each experiment. Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, the abdomen opened and the caecum and colon removed. Upon dissection, observations describing the tissue and the colonic contents were recorded, and the colon measured (colon length has proven a useful indicator of colitis (Diaz-Granados et al., 2000) and is used here as a check to ensure that all DSS-treated mice responded to the pro-colitic agent). A 5 mm piece of mid-colon was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, dehydrated through graded alcohols, paraffin-wax embedded and 3 μm sections were collected on coded slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Colonic histology was assessed by an individual unaware of the experimental treatment. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was measured in tissue extracts of the terminal portion of the colon and extracts of mid-caecum following a published protocol (Diaz-Granados et al., 2000)

Ussing chamber analysis of colonic epithelial ion transport

A 2 cm segment of mid-colon and of mid-caecum from each mouse was opened along the mesenteric border and mounted in an Ussing-type chamber with an exposed surface area of 0.6 cm2. (A single piece of tissue was used from each animal because pilot studies revealed significant colonic regional variability in Isc (noting that colon from DSS-mice was ∼7 cm); however, this precluded paired analyses and radio-labelled ion flux studies.) Tissues that displayed obvious gross macroscopic ulceration were not used. Tissues were bathed in oxygenated 37°C Krebs buffer containing either glucose (10 mM; serosal buffer) or mannitol (10 mM; luminal buffer) at pH 7.35±0.02 (Diaz-Granados et al., 2000). The tissues were short-circuited by an automated voltage clamp (WPI, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and the short-circuit current (Isc in μA/cm2) was continuously monitored as an indication of net active ion transport. After a 15 – 20 min equilibrium period baseline Isc and potential difference was recorded and ion conductance calculated using Ohm's law. Tissues were then challenged with the cholinergic agonist, carbachol (CCh; 10−4 M)±pretreatment with various pharmacologics: the neuronal blocker, tetrodotoxin (TTX, 10−6 M); the cholinergic muscarinic receptor antagonist, atropine (ATR, 10−6 M); or, the cholinergic nicotinic receptor antagonist, hexamethonium (HEX, 10−5 M) (all Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). A high dose of CCh was used (10−4 M) because it consistently gives an obvious response in murine tissue which has the attendant muscle layers and since this is the concentration with which the ‘reversed' Isc response was reported (Diaz-Granados et al., 2000). The response to CCh (or other agents) was recorded as the maximum change in Isc to occur within 10 min of treatment. Some tissues were treated with nicotine (NIC, 10−6 M)±TTX. At the end of each experiment all tissues were challenged by addition of forskolin (FSK; 10−5 M; evokes Cl− secretion via cyclic AMP) to the serosal buffer and the ΔIsc was recorded (Diaz-Granados et al., 2000). Forskolin challenge is used as an index of viability (ensuring that the tissue could mount a secretory response) and as an internal control to ensure that the tissue was mounted in the correct orientation in the chamber.

Opiate and α-adrenergic inhibition

Tissues mounted in Ussing chambers were treated with the non-specific opiate receptor antagonist, naloxone (10−5 M; Sigma Chemical Co.) or the α-adrenergic blocker, phenoxybenzamine (10−6 M; RBI/Sigma, Natick, MA, U.S.A.) 10 min prior to CCh challenge (Quinto & Brown, 1991; Tapper et al., 1978).

Identifying the charge carrying ion

To identify the ion responsible for the ΔIsc to CCh three types of experiments were conducted: (1) Cl− free Krebs buffer (Saunders et al., 1994); (2) Cl−/HCO3−-free buffer (Traynor et al., 1993); or (3) the Na+ channel blocker amiloride (10−4 M; Sigma Chemical Co.) was added to the buffer bathing the luminal side of the tissue 15 min before CCh.

Statistical analysis and data presentation

Results are presented as mean±standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Data were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc pair-wise comparisons with the Keuman-Keuls test and P<0.05 was accepted as the level of statistically significant difference.

Results

Development of colitis

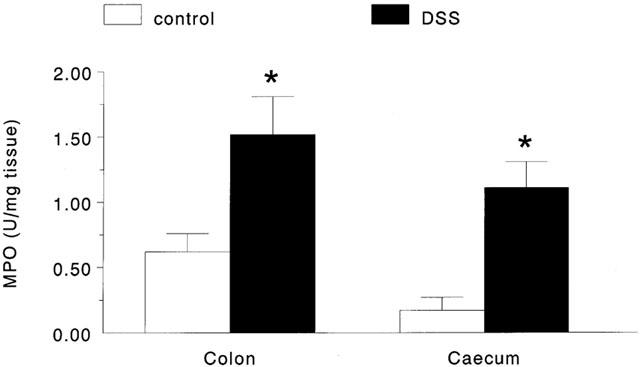

All mice treated with 4% DSS developed signs of intestinal dysfunction/colitis: hunched posture; ruffled fur; wet, bloody or foecal stained perianal area; hyperemic colon. At the end of the 8 day experimental period, DSS-treated mice showed significant wasting (−3.1±0.2 g*) and shortening of the colon (65±2 mm*; n=29; *P<0.05 compared to control) compared to the time-matched controls (body weight change=+0.7±0.2 g; colon length=97±2 mm; n=21). On macroscopic examination, although shortened, the majority of tissues from DSS-treated mice were not grossly ulcerated, but did display the typical microscopic signs of inflammation for this model: patchy ulceration, oedema, mononuclear and neutrophilic infiltrate and goblet cell depletion (Diaz-Granados et al., 2000; Mahler et al., 1998). MPO levels were increased to similar levels in both colonic and caecal tissues compared to tissues from control animals (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bar chart showing the increase in colonic and caecal myeloperodixase activity in tissues excised from DSS-treated mice compared to those from control mice (*P<0.05 compared to control; n=8 – 11).

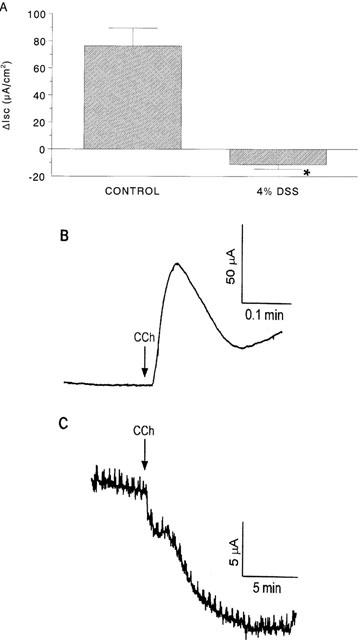

Carbachol-induced changes in colonic ion transport

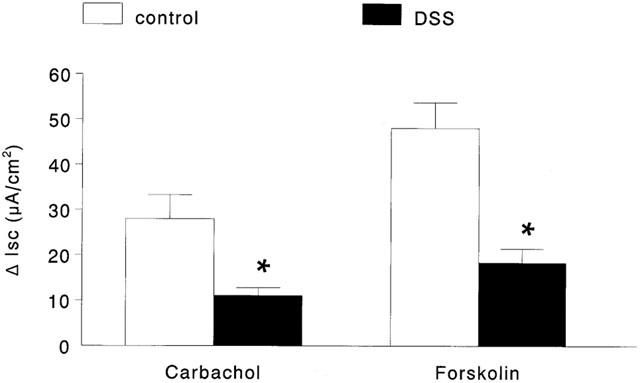

Baseline Isc and conductance values in colonic and caecal tissues from DSS and control mice were not significantly different (data not shown). This is consistent with our previous findings in this model of colitis (Diaz-Granados et al., 2000; Reardon et al., 2001). The addition of CCh to the serosal side of tissues from control mice gave a ΔIsc= 76.3±13.0 μA/cm2 compared to a response of −11.3±3.3 μA/cm2 (P<0.05 compared to control) in colonic preparations from DSS-treated mice (Figure 2). Forskolin responses in colonic tissue were significantly reduced from 137.8±12.3 μA/cm2 in control colon (n=21) to 33.1±5.8 μA/cm2 (P<0.05) in DSS-treated mice (n=31). The forskolin-induced Isc response was reduced in every tissue from DSS-treated mice, but always gave an increase in Isc with a current trace similar to control tissues. Caecal Isc responses to CCh were significantly reduced in tissue from DSS-treated mice compared to control, however the current deflection was not reversed as seen in the colonic segments (Figure 3). Similarly, caecal FSK responses were significantly reduced in tissue from DSS-treated mice compared to control tissue (Figure 3). Subsequent experiments focused on assessment of the CCh-induced Isc response in colonic segments only.

Figure 2.

Bar chart (A) showing the change in short-circuit current (ΔIsc) evoked by carbachol (CCh, 10−4 M) challenge of colonic segments from control mice and those exposed to 4% DSS (*P<0.05 compared to control; n=8 – 11; negative value indicates a drop in Isc). Panels (B) and (C) are representative CCh-induced Isc current tracings from control and DSS-treated mice, respectively.

Figure 3.

Bar chart showing the change in short-circuit current (ΔIsc) evoked by carbachol (10−4 M; n=14 – 16) and forskolin (10−5 M; n=21 – 31) in caecal tissues from control and DSS-treated mice mounted in Ussing chambers (*P<0.05 compared to control).

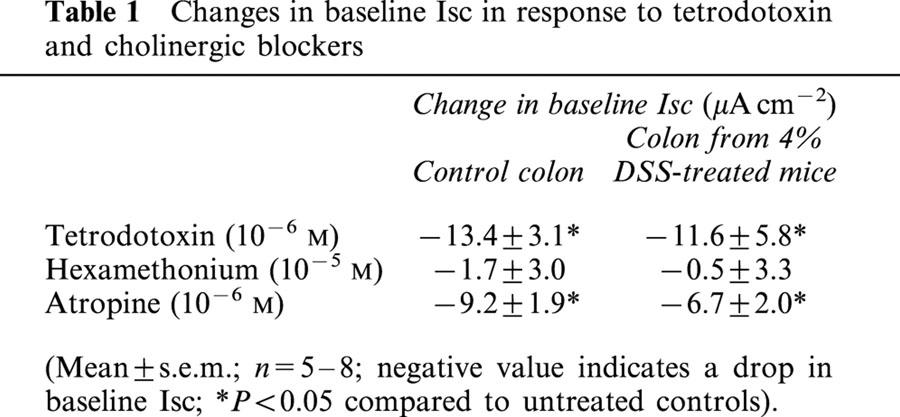

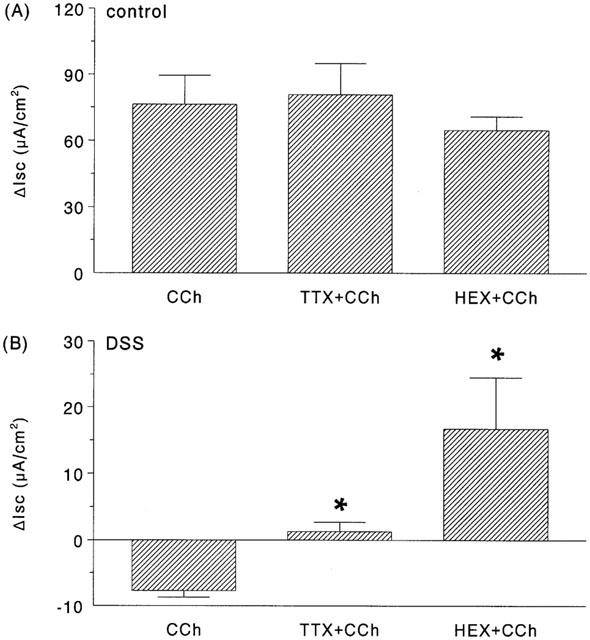

Tetrodotoxin (TTX)

Addition of the neuronal fast Na+ channel blocker, TTX (10−6 M) to the serosal buffer caused a drop in baseline Isc in colonic tissue from DSS-treated and control mice (Table 1), indicating a tonic role for the enteric nervous system in controlling murine colonic ion transport. TTX pretreatment did not significantly affect the change in Isc evoked by CCh in colonic segments from controls (Figure 4A). However, CCh responses in tissues from DSS-treated mice were TTX-sensitive (Figure 4B).

Table 1.

Changes in baseline Isc in response to tetrodotoxin and cholinergic blockers

Figure 4.

Bar charts showing the change in short-circuit current (ΔIsc) evoked by carbachol (10−4 M) in colonic segments from (A) control or (B) 4% DSS-treated mice ± a 15 min pretreatment with either tetrodotoxin (TTX; 10−6 M) or hexamethonium (HEX; 10−5 M) (*P<0.05 compared to CCh only; n=6 – 11).

Hexamethonium (HEX)

Use of the cholinergic nicotinic receptor blocker, HEX did not significantly affect baseline Isc in control tissues or those from DSS-treatment mice. Similarly, HEX did not significantly affect the CCh-response in control tissue (Figure 4A). However, in tissue from DSS-treated mice HEX pretreatment led to a positive Isc deflection (16.7±7.9 μA/cm2) (Figure 4B); the CCh-response was still significantly reduced compared to that observed in control tissues and this is in fact typical of other models of colitis (Asfaha et al., 1999).

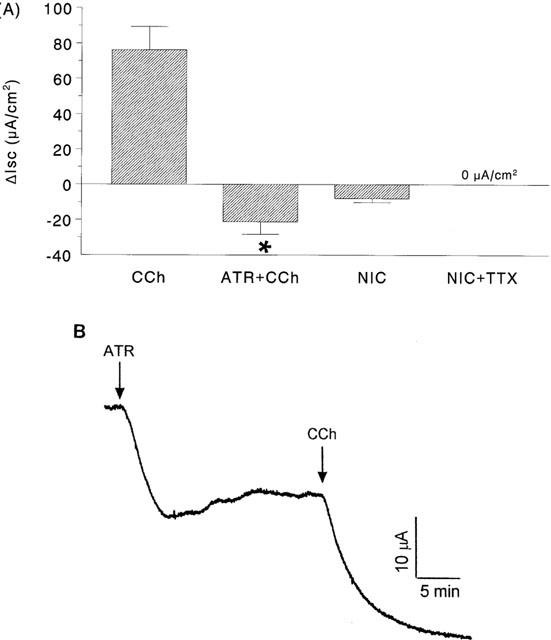

Atropine (ATR)

Blockade of cholinergic muscarinic receptors in colonic segments from control Balb/c mice by ATR caused a decrease in baseline Isc (Table 1). Moreover, subsequent challenge with CCh led to a transient drop in Isc rather than the normal increase in Isc observed in the absence of ATR (Figure 5). The combination of HEX+ ATR pretreatment of colonic tissue from control Balb/c mice completely abolished the CCh response (i.e. ΔIsc= 0 μA/cm2; n=7). Colonic segments from control C57B1/6 pretreated with ATR displayed a ΔIsc to CCh=−36.2 ±8.3 μA/cm2 (n=4), indicating that these events are not unique to the Balb/c strain (C57/B16 mice develop colitis in response to DSS (Mahler et al., 1998), but we did not examine ion transport in tissues from DSS-colitic C57/B16 mice).

Figure 5.

Bar chart showing the change in short-circuit current (ΔIsc) evoked by carbachol (CCh, 10−4 M) in colonic segments from control mice ± a 15 min pretreatment with either atropine (ATR; 10−6 M) or treated with nicotine (NIC; 10−6 M)±TTX (panel A) (*P<0.05 compared to CCh only; n=6 – 11; negative value indicates a drop in Isc). Panel B is a representative Isc tracing from control colon treated with ATR then CCh.

In DSS-treated Balb/c mice, pretreatment with ATR caused a drop in baseline Isc (Table 1). Subsequent challenge with CCh resulted in a drop in Isc that was not significantly different from the time-matched non-ATR treated tissues from this cohort of DSS-colitic mice (CCh=−4.6±1.7 and ATR+CCh=−3.7±1.1 μA/cm2 (n=4)).

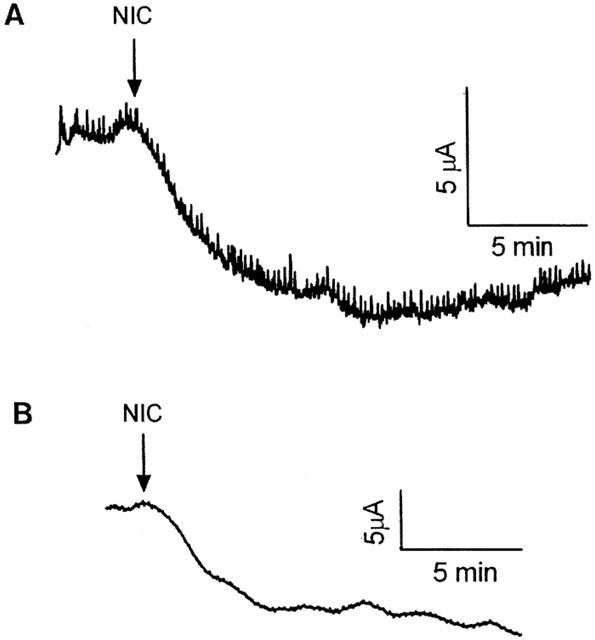

Nicotine (NIC)

Addition of NIC to the buffer bathing the serosal side of normal colon or colonic segments from DSS-treated mice resulted in decreases in Isc of −7.9±2.3 (n=9) and −9.2±0.7 μA/cm2 (n=4), respectively (Figures 5A, 6). The NIC-induced changes in Isc were TTX-sensitive. In the presence of TTX, NIC evoked no change in Isc in control tissues (0 μA/cm2; n=4) (Figure 5A). Similarly, there was no Isc response in tissue from DSS-mice treated with TTX and then NIC-challenged (n=3).

Figure 6.

Representative tracings showing the change in short-circuit current evoked in (A) control colon and (B) colonic segments from DSS-treated mice in response to nicotine (NIC, 10−6 M).

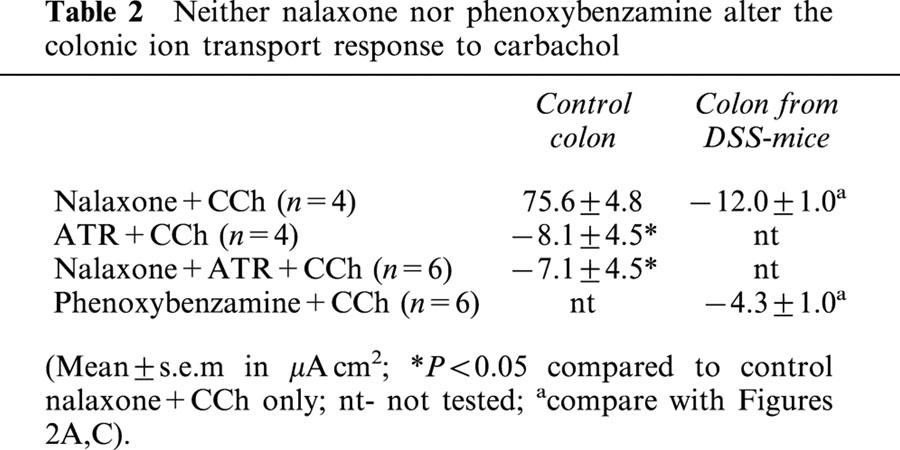

Opiate and α-adrenergic inhibition

The addition of the non-selective opiate receptor antagonist, naloxone to the serosal side of tissues from control mice had no effect on baseline Isc. Subsequent challenge with CCh resulted in a ΔIsc=75.6±4.8 μA/cm2. Treatment of control colonic tissue with ATR+naloxone and then CCh did not result in a statistically significant amelioration of the ATR+CCh Isc response, nor did naloxone pretreatment result in an increase in Isc in colon from DSS-mice in response to CCh (Table 2). Assessment of α-adrenergic receptors in tissue from DSS-mice revealed that phenoxybenzamine pre-treatment did not lead to a positive Isc deflection in response to CCh (Table 2).

Table 2.

Neither nalaxone nor phenoxybenzamine alter the colonic ion transport response to carbachol

Identifying the charge carrying ion

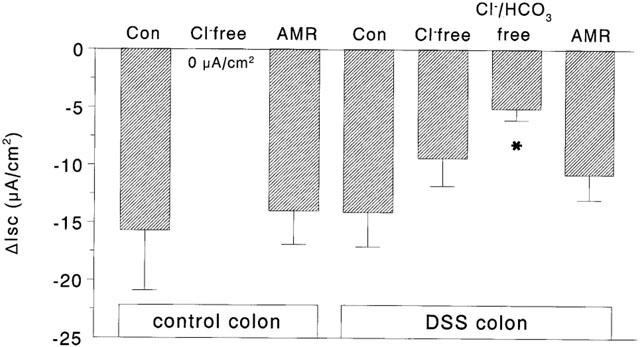

CCh challenge of colonic tissue from control mice bathed in Cl− free buffer resulted in an increase in Isc of 11.7±7.1 μA/cm2 (n=5), significantly less than the ∼60 μA/cm2 observed in response to CCh in normal Krebs buffer (see Figure 2A). The drop in Isc observed after ATR+CCh treatment (Figure 5A) was not seen in Cl−-free buffer (Figure 7). However, pretreatment with ATR+amiloride followed by CCh resulted in a drop in Isc that was not different from that seen in ATR+CCh-only treated tissue (compare Figures 5,7). In contrast, colonic segments from DSS-treated mice displayed a drop in Isc in response to CCh independent of use of Cl−-free buffer (n=8) or amiloride (n=5), whereas there was a statistically significant diminution of the response in tissues bathed in Cl−/HCO3−-free buffer (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Bar chart showing the change in short-circuit current (ΔIsc) to carbachol in colonic segments from control or DSS-colitic mice mounted in Ussing-chambers and bathed in Cl−-free buffer, Cl−/HCO3−-free buffer or pre-treated with the sodium channel blocker, amiloride (AMR; 10−4 M) [Note, tissue from control mice were also atropine treated (10−6 M)] (n=5 – 8; *P<0.05 compared to response in normal (control) buffer).

Discussion

Efficient regulation of enteric epithelial ion transport (and hence water movement) is essential for host well-being, hydrating the epithelial surface for contact digestion and diffusion of nutrients, creating a ‘washer' flow that helps propel noxious substances (e.g. toxins, pathogens) caudally, and when exaggerated can result in debilitating diarrhea. The principal findings of this analysis of cholinergic regulation of colonic ion transport in a murine model of colitis are: (1) segments of mid-colon from mice with DSS-induced colitis show a drop in Isc in response to carbachol (CCh), a current deflection opposite to that observed in colonic tissue from control mice; (2) the CCh-induced drop in Isc in colon from colitic mice is reversed by hexamethonium indicating involvement of cholinergic nicotinic receptors; (3) the CCh-induced drop in Isc can be reproduced in control colon by blocking cholinergic muscarinic receptors prior to challenge with CCh; and (4) the drop in Isc in control colon was dependent on Cl−, whereas Cl−/HCO3− are responsible for the Isc change in colonic tissue from mice treated with DSS.

The enteric nervous system is comprised of intrinsic and extrinsic nerves which contain acetylcholine, multiple monoamines and at least 20 neuropeptides in a stoichiometry that is not fully defined (Wood, 1993). The nerves of the submucosal plexuses and those that form an anastomotic network in the lamina propria are critically important in the control of epithelial ion transport (Cooke, 1994). Tissue from a range of mammalian species, when mounted in an Ussing chamber and challenged with cholinomimetics, display a transient increase in Isc that is typically due to an efflux of Cl− from the enterocyte (Asfaha et al., 1999; Javed & Cooke, 1992; Saunders et al., 1994); an event mediated in large part by muscarinic cholinergic receptors on the enterocyte. Analysis of tissues from models of colitis, stressed rodents, parasitized animals and human resections has consistently shown that the increase in Isc evoked by CCh is significantly reduced compared to controls (Asfaha et al., 1999; Crowe et al., 1997; Masson et al., 1996; Saunders et al., 1994). In contrast, the present study shows that CCh causes a drop in Isc in colonic tissue from DSS-treated mice, confirming our previous observations (Reardon et al., 2001). While a drop in Isc in response to CCh is not the norm, it is not unprecedented. For instance, Cuthbert et al. (1994) reported that CCh caused a drop in Isc in colon from mice with the cystic fibrosis mutation. Also, Brayden & Baird (1994) showed that rabbit ileal Peyer's patch tissue responded to CCh with a drop in Isc and this may be an inherent property of the microfold ‘M' epithelial cell that covers the patch or it may indicate an immune cell modifying effect on the epithelium's response to cholinergic stimulation.

Rodents who consume a solution of DSS-water develop a colitis that shares some similarity with human ulcerative colitis (Okayasu et al., 1990). We reported that unlike other models of murine colitis (many of which are more like Crohn's disease), CCh-challenge of mid-colonic segments led to a drop in Isc and not the expected transient increase in Isc (Diaz-Granados et al., 2000). Here we show that the CCh-induced ΔIsc is TTX-sensitive but independent of blockade of muscarinic cholinergic receptors. Since CCh is a non-selective cholinomimetic we reasoned that the CCh-induced ΔIsc in tissue from DSS-treated mice could be via a nicotinic cholinergic receptor. Subsequently we observed that tissues pre-treated with HEX responded with an increase in Isc in response to CCh: the increase in Isc was still less than control tissue; however, it was more reminiscent of other models of enteric inflammation (Asfaha et al., 1999; Masson et al., 1996). The mechanism underlying the typical hyporesponsiveness of tissue from animal models of colitis has yet to be satisfactorily explained. Furthermore, blockade of muscarinic cholinergic receptors in normal tissues with ATR resulted in a drop in Isc in response to CCh. These findings support the contention that DSS-colitis alters the balance in cholinergic regulation of ion transport, allowing the effects of a nicotinic cholinergic receptor to be seen - the activation of which causes a drop in Isc. Corroborating this supposition nicotine treatment of colonic segments caused a drop in Isc.

These data, suggesting a switch in cholinergic regulation of colonic epithelial ion transport, raise a number of important mechanistic issues that remain to be addressed. First, is the altered CCh response accompanied by tachyphylaxis of epithelial M3 receptors or reduced numbers of receptors on the enterocyte? Second, is there any contribution of other muscarinic cholinergic receptors to the altered Isc pattern? Third, is the distribution or density of neurones bearing nicotinic receptors increased in the colon of mice with colitis? Fourth, is there an increase in the number or affinity of nicotinic receptors, or altered expression of receptor subtypes in the colitic tissue? Fifth, is it possible that the abnormal CCh-response might be due to an enterocytic signal transduction defect, similar to that shown in the T84 colonic epithelial cell line (Vajanaphanich et al., 1994)? Precise pharmacological, receptor binding, immunocytochemical and signal transduction studies will provide the answers to these questions.

From a clinical perspective, nicotine treatment can be beneficial in patients with ulcerative colitis (Guslandi, 1999). Our data present one possible explanation for this. We speculate that the mechanism underlying the development of ulcerative colitis in some individuals reveals a nicotinic cholinergic receptor that becomes important in cholinergic regulation of ion transport, tilting the balance in favour of absorption rather than secretion. Thus, analysis of nicotinic responses in DSS-colitis may elucidate mechanism(s) pertinent to understanding the therapeutic value of nicotine in human ulcerative colitis.

To-date there is no evidence for a nicotinic cholinergic receptor on gut epithelial cells and so it is likely that the nicotinic response is neuronally mediated. This is supported by our findings that the CCh responses in colitic tissue and the NIC responses in normal and colitic tissue were TTX-sensitive. Thus, if our working hypothesis is correct, the question arises: what intermediate molecule mediates the CCh response after activation of the nicotinic cholinergic receptor? While there are some data on the neurochemical circuitry of the mouse colon (Sang & Young, 1998), the expression and distribution of nicotinic receptors on neurones has not been documented. Nevertheless, a number of molecules do present themselves as possible intermediates in the CCh-nicotinic cholinergic receptor evoked drop in Isc, including opiates (Quinto & Brown, 1991), noradrenaline (Tapper et al., 1978), and the neuropeptides, neuropeptide Y (NPY) and somatostatin (McKay et al., 1996). We assessed the putative involvement of opiates and noradrenaline in the CCh-induced drop in Isc by pretreating tissues with the non-selective opiate antagonist naloxone or with phenoxybenzamine, an α-adrenergic receptor blocker. Opiate receptor agonists evoke a drop in Isc in porcine small intestine that is naloxone-sensitive (Quinto & Brown, 1991); however, we found that naloxone affected neither the CCh-induced drop in Isc in colon from DSS-treated mice nor the ATR+CCh-induced drop in Isc in colonic segments from control mice. Tapper et al. (1978) reported dose-dependent effects of CCh on rabbit ileal Isc, where a CCh-evoked drop in Isc was partially blocked by phenoxybenzamine although transepithelial fluxes of Na+ and Cl− were not appreciably altered. In the present study we were unable to demonstrate any affect of phenoxybenzamine on the CCh-induced drop in Isc in murine colon. Thus, in addition to presenting data that DSS-colitis interferes with muscarinic cholinergic control of Isc, this effect does not appear to be mediated by opiates or noradrenaline interaction with α-adrenergic receptors.

Driving forces for directed water movement are in large part created by vectorial transport of Na+ and Cl−, with roles for HCO3− and K+ in a tissue-specific manner (Barrett & Dharmsathaphorn, 1991). Assessing the ionic basis of the ΔIsc, Cl− was essential for the ATR+CCh-induced drop in Isc in control colon. However, neither amiloride nor Cl− free buffer significantly altered the CCh-induced drop in Isc in colon excised from DSS-treated mice. A significant amelioration of the CCh effect in colitic tissue was only observed in experiments conducted with Cl−/HCO3−-free buffer. Similarly, the CCh-induced drop in Isc in rabbit Peyer's patch was due to HCO3− and not Na+ or Cl− (Brayden & Baird, 1994). As a caveat, this examination of the ionic basis of the ΔIsc underscores the value of comparing physiological pathways in both control and colitic tissue – in this instance different ion fluxes would appear to be responsible for similar net current changes.

In contrast to the colon from DSS-treated mice, challenge of caecal tissue with CCh did not evoke a drop in Isc. This divergence in the colonic and caecal response to CCh suggests a number of possibilities. The degree of inflammation in the caecum may be less than in the colon, yet based on MPO values this seems unlikely. However, we have not rigorously assessed the inflammatory response at both sites (MPO is but one index of inflammation) and thus the responses could be quite different, both qualitatively (i.e. type of cellular infiltrate) and quantitatively (e.g. number of infiltrating T cells). As an alternative explanation, this difference in CCh responsiveness might reflect local differences in cholinerigic innervation (i.e. nerve or receptor type and/or distribution) of the two tissues.

Finally, there is a dearth of data on murine colonic epithelial ion transport. This study presents novel findings in favour of disruption of normal cholinergic control of ion transport in DSS-colitis that reveals a nicotinic cholinergic receptor, the activation of which causes a drop in Isc that is mediated by Cl−/HCO3−- and is not dependent on opiates or noradrenaline interaction with α-adrenergic receptors.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by an operating grant from the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of Canada (CCFC) to DMM. BS is a recipient of a CCFC summer studentship and JDS is a recipient of a Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) post-doctoral fellowship. DMM is a CIHR scholar. Assistance from J. Watson and T. Prior is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- AMR

amiloride

- ATR

atropine

- CCh

carbachol

- DSS

dextran sodium sulphate

- FSK

forskolin

- HEX

hexamethonium

- Isc

short-circuit current

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NIC

nicotine

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

References

- ASFAHA S., BELL C.J., WALLACE J.L., MACNAUGHTON W.K. Prolonged colonic epithelial hyporesponsiveness after colitis: role of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Am. J. Physiol. (Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.) 1999;276:G703–G710. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.3.G703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRETT K.E., DHARMSATHAPHORN K. Secretion and absorption: small intestine and colon Textbook of Gastroenterology 1991Philadeplhia: JB Lippioncott Co; 265–294.ed. Yamada, T. pp [Google Scholar]

- BARRETT K.E., KEELY S.J. Chloride secretion by the intestinal epithelium: molecular basis and regulatory aspects. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 2000;62:535–572. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAYDEN D.J., BAIRD A.W. A distinctive electrophysiological signature from Peyer's patches of rabbit intestine. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1994;113:593–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COOKE H.J. Neuroimmune signaling in regulation of intestinal ion transport. Am. J. Physiol. (Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.) 1994;266:G167–G178. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.2.G167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROWE S.E., LUTHRA G.K., PERDUE M.H. Mast cell mediated ion transport in the intestine from patients with and without inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1997;41:785–792. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.6.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROWE S.E., PERDUE M.H. Anti-immunoglobulin E stimulated ion transport in human large and small intestine. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:764–772. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90894-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUTHBERT A.W., MACVINISH L.J., HICKMAN M.E., RADCLIFF R., COLLEDGE W.H., EVANS M.J. Ion-transporting activity in the murine colonic epithelium of normal animals and animals with cystic fibrosis. Pflugers Arch. 1994;428:508–515. doi: 10.1007/BF00374572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIAZ-GRANADOS N., HOWE K., LU J., MCKAY D.M. Dextran sulphate sodium-induced colonic histopathology, but not altered epithelial ion transport, is reduced by inhibition of phosphodiesterase activity. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;156:2169–2177. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65087-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUSLANDI M. Nicotine treatment for ulcerative colitis. Brit. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1999;48:481–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAVED N.H., COOKE H.J. Acetylcholine release from colonic submucous neurons associated with chloride secretion in the guinea pig. Am. J. Physiol. (Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.) 1992;262:G131–G136. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.262.1.G131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KACHUR J.F., KESHAVARZIAN A., SUNDARESAN R., DORIA M., WALSH R., DE LAS ALAS M.M., GAGINELLA T.S. Colitis reduces short-circuit current response to inflammatory mediators in rat colonic mucosa. Inflammation. 1995;19:245–259. doi: 10.1007/BF01534465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAHLER M., BRISTOL I.J., LEITER E.H., WORKMAN A.E., BIRKENMEIER E.H., ELSON C.O., SUNDLBERG J.P. Differential susceptibility of inbred mouse strains to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Am. J. Physiol. (Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.). 1998;274:G544–G551. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.3.G544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASSON S.D., MCKAY D.M., STEAD R.H., AGRO A., STANSIZ A., PERDUE M.H. Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection causes neuronal abnormalities and altered neurally regulated ion secretion in rat jejunum. Parasitology. 1996;113:173–182. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000066415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCKAY D.M., BERIN M.C., FONDACARO J.D., PERDUE M.H. Effects of neuropeptide Y and substance P on antigen-induced ion secretion in rat jejunum. Am. J. Physiol. (Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.) 1996;271:G987–G992. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.6.G987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKAYASU I., HATAKEYAMA S., YAMADA M., OHKUSA T., INAGAKI Y., NAKAYA R. A novel method in induction of reliable experimental acute and chronic colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:694–702. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90290-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERDUE M.H., MCKAY D.M. Integrative immunophysiology in the intestinal mucosa. Am. J. Physiol. (Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.) 1994;267:G151–G165. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.267.2.G151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUINTO F.L., BROWN D.R. Neurohormonal regulation of ion transport in the porcine distal jejunum. Enhancement of sodium and chloride absorption by submucosal opiate receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Thera. 1991;256:833–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REARDON C., SANCHEZ A., HOGABOAM C.M., MCKAY D.M. Tapeworm infection reduces the ion transport abnormalities induced by dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) colitis. Infect. Immunity. 2001;69:4417–4423. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4417-4423.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANG Q., YOUNG H.M. The identification and chemical coding of cholinergic neurones in the small and large intestine of the mouse. Anat. Record. 1998;251:185–199. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199806)251:2<185::AID-AR6>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAUNDERS P.R., KOSECKA U., MCKAY D.M., PERDUE M.H. Acute stressors stimulate ion secretion and increase epithelial permeability in rat intestine. Am. J. Physiol. (Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.) 1994;267:G794–G799. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.267.5.G794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEIDLER U., ROSSMANN H., JACOB P., BACHMANN O., CHRISTIANI S., LAMPRECHT G., GREGOR M. Expression and function of Na+HCO3− cotransporters in the gastrointestinal tract. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2000;915:14–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAPPER E.J., POWELL D.W., MORRIS S.M. Cholinergic-adrenergic interactions on intestinal ion transport. Am. J. Physiol. (Endocrinol.) 1978;235:E402–E409. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.4.E402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAYNOR T.R., BROWN D.R., O'GRADY S.M. Effects of inflammatory mediators on electrolyte transport across the porcine distal colon epithelium. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Thera. 1993;264:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAJANAPHANICH M., SCHULTZ C., RUDOLF M.T., WASSERMAN M., ENYEDI P., CRAXTON A., SHEARS S.B., TSIEN R.Y., BARRETT K.E., TRAYNOR-KAPLAN A. Long-term uncoupling of chloride secretion from intracellular calcium levels by Ins(3,4,5,6)P4. Nature. 1994;371:711–714. doi: 10.1038/371711a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOOD J.D. Neuro-Immunophysiology of colon function. Pharmacology. 1993;47:7–13. doi: 10.1159/000139836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]